RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

"THAT'S a marianthus."

Marley Rye put up his glasses, and discovered a gorgeous specimen of an amaranthus. A broad smile spread over his face as he looked at the bright-eyed girl who flitted like a golden butterfly from flower to flower, pointing out their beauties and enhancing their reputations, as she murdered their good names. A scarlet screen of exotics threw up her white dress in bold relief, and Rye reflected that there were worse things in life than being piloted through acres of glass-houses crammed full of choice blooms by the daughter of the house, especially when that daughter happened to be Bobbie.

Marley was also having a second treat, for in his capacity of a classic swell who, according to rumour, spouted Greek in his cradle, he was deriving an immense amount of secret mirth from the ingenuity with which the girl managed to mangle the most straightforward name.

"Whoever taught you these long words?" he asked, as Bobbie untwisted her mouth after an extra effort.

"Steggins, our head gardener. An awfully clever man. He knows all the names, and he taught me. It's difficult, but, you see, I try."

"I'm sure you do. You are the most trying person I know."

But Bobbie did not rise to the bait.

"Oh, look!" she cried. "They're trying the new cob. Come outside quickly!"

As Rye followed the girl from the moist heat of the conservatory into the glare of the sun he reflected on the strangeness of Fate which had made him an inmate of the house. For, though the Flower family had come to the district seven months previously, they had not yet "arrived." When they settled in the neighbourhood they took the finest seat in the county, as a tangible proof of the large fortune which was believed to be theirs. But they left their family tree behind them in Australia, and the county, who vaguely believed that the ancestors of all people hailing from that particular Colony were drafted from Botany Bay, delayed calling on the newcomers lest they should entertain future convicts unawares.

Altogether, at present, the Flowers were having an uphill time, for they were rich, hospitable, and wanted to be friendly. For some time past the county was busily engaged in weighing them in the balance. Most of the bolder members wished to fraternize with the owner of the best preserves in the district, but the conservative families were upset by the news that the Colonials drank tea with every meal. The family consisted of the elder Flower, who was a hatchet-faced, spare man, whose character was striking enough to rise superior to his social slips, and to stamp him a personality. He was respected generally: but then the Flower son, in his crude savagery, was almost impossible, and the Flower nephew—Mole — quite impossible. With Mrs. Flower the neighbourhood was not concerned, for, though keenly interested in fur and feather, the only thing with wings that came outside their province was an angel, and Mrs. Flower had been dead fifteen years.

Bobbie was the hardest nut to crack. Young, beautiful, and domineering, she became instantly the prettiest girl in the county and the most unpopular. After she shocked the most select circle that ever owed a washing bill to a steam laundry, by an unguarded reference to having washed her own blouses, those same garments lacked the starch of the social manner, where she was concerned. Marley Rye had met her out with the harriers on one of the rare occasions when he came down from his beloved Cambridge, and had spent whole days with the beautiful Australian in sprinting across country. Bobbie's beauty appealed to him first, and then her pluck, her breeziness, and unconventionally, and if she showed rather more leg in negotiating a hedge than the average girl, she also gave him glimpses of a thoroughly strong, true nature. So, to his great surprise, Rye left off hunting the hare and took to running after Bobbie, with the result that he received an invitation to the Flower domains for a week-end.

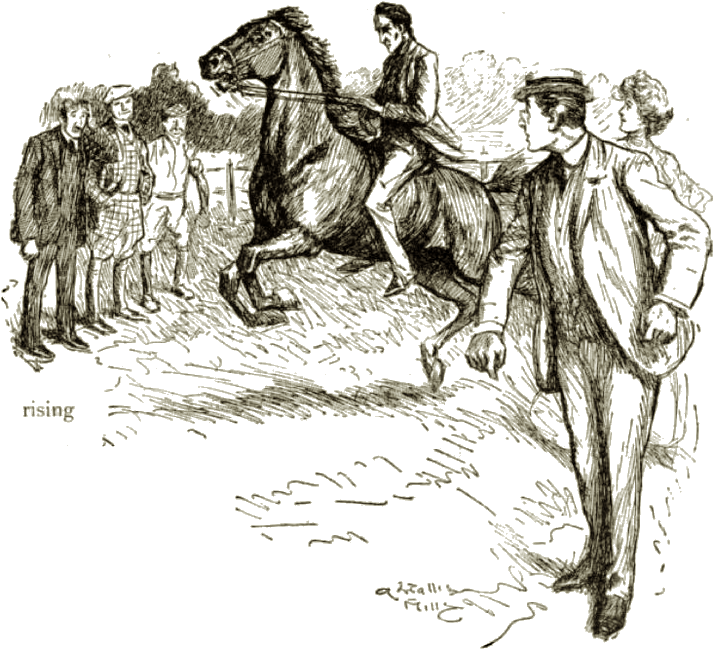

"That cob is a devil," remarked Bobbie, airily, as they approached a grass plot where a group of men gathered round a restless horse, with a beautiful coat and a wicked eye.

"Here, you two, come along and see some sport," called out the elder Flower, joyfully. "This is like old times."

The stable-boy, who was nearly lifted off his feet with every movement of the horse's head, grinned with anticipation as the Flower son elbowed him out of the way and started to mount the cob. A scene of mad excitement followed. The horse reared up in every direction, bucking and kicking furiously, while gravel flew up in white showers,: and the family dodged the flying hoofs with wild glee—Bobbie's delighted scream above the rest.

"First blood to the cob," observed Flower, as the horse deposited Ned anything but gently on the turf. "You try him next, Dick!"

But Mole was speedily downed, and then Flower himself mounted: and though he was finally ejected from his seat, he gave such a splendid display of horsemanship and strength that Rye's face kindled.

He gave such a splendid display of horse-

manship and strength that Rye's face kindled.

"Capital, capital!" he said to Bobbie: "your father's riding beats everything I've seen."

"Yes, doesn't it?" Bobbie's cheeks were flushed. "Your turn now," she added.

Rye's pleasure was suddenly diluted. "No, thank you," he said, hastily; "I wouldn't dream of mounting that brute! I'm not a don at riding, like you people."

He felt uncomfortable as he spoke, but he had no idea of the consternation that his answer was to produce.

"But you'll try it, of course?" said Flower, whose eyes were bulging with astonishment. "You won't give the horse best?"

"I should if I tried to mount him. It would be equivalent to asking one of you to smash my head in."

A silence followed, broken only by the snigger of the stable-boy. Then Flower grunted, "Well, I've heerd a lot about British pluck, but—h'm!"

"Get up, Bobbie," interposed Mole, "just to show Mr. Rye it's quite easy."

Rye bit his lip.

"It's not a question of pluck, but of common sense," he said, shortly.

"Nonsense! See here — I dare you to mount!" burst in Robbie.

The group instantly made way, expecting to see Rye dash madly for the horse, but he only frowned.

"I'm afraid your 'dare' won't alter my decision. I'm not a fool."

"No. Something else, perhaps!"

The whole family, hot with indignation, turned and glared at Rye, who, cold with disgust, glowered back at them.

"Well, since I don't shine at this exhibition of skill, and I seem to be interfering with the enjoyment, I'll have a smoke," he said, at length.

"Don't smoke in the stables. Some of the horses are rather fresh."

It was Bobbie's voice, and Rye rose to the taunt.

"Thanks, I'll take the risks, if any."

He turned on his heel, and a chorus of loud laughter followed him, which made the unaccustomed red rise to his sallow face. As he walked away his brain was in a whirl, as if a ruthless hand had suddenly made hay in his well-regulated and neatly-docketed mind. He felt like a king whose monarchy had been insulted, and, at the same time, like a small boy who had been whipped, and who wanted his mother. His sense of personal dignity had been badly hurt. Throughout his life he had been keenly conscious of belonging to the superior section of Society, which is hall-marked by the capital letter. His family was prominent in the county; the family silver was nearly as ancient as the crest engraved thereon: while for the greater part their moral status dated back to a period of antiquity which is known as "the old Adam." In short, Rye was a somebody, and this somebody had been insulted by an Australian squatter. He here dug his heel into the fresh white gravel of the path, and his wound received its first drop of balm by the cut-up appearance of the Flower gravel. Then he remembered that he also belonged to the aristocracy, of brains, as his career at Cambridge testified, and, smarting with the jeers of the illiterate Mole, he raised his stick and savagely cut off the head of a Flower geranium. Ardent botanist though he was, he viewed its fall with glee. Then flashed across his mind the memory of Bobbie's short, sweet face, her breeziness, and her whims. Sadly he picked up the Flower geranium and put it in his buttonhole. He could not include Bobbie in his black list. Bobbie was beautiful, Bobbie was rich: in the future Bobbie might possibly wear a coronet. And Bobbie despised him. Rye suddenly shrank to four feet odd again. He felt sure he was a small boy in an Eton jacket, and he wanted to steal away somewhere and hide his grief from the world.

He passed from the flowers and the turf through a little door, and found himself in another part of the gardens. Fruit trees sunned themselves on the mellowed, red-bricked walls; glass frames flashed in the sunshine. Past rows of pea-sticks and acres of glass he walked, till trees gave way to sheds and cabbage-patches to outhouses. A long line of buildings lay to one side, and their shady aspect tempted Rye to leave the sun and the midday heat. He would smoke off his troubles in the stables.

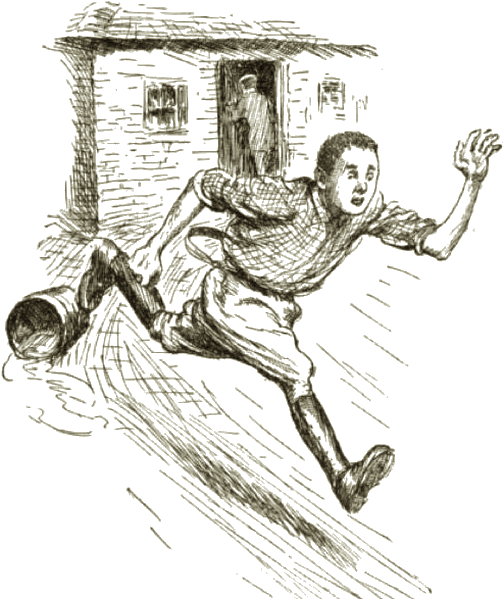

He went up to the green-painted door and fumbled with the latch, but to his annoyance he found that the place was locked. Peering about with his short-sighted eyes he discovered a bunch of keys hanging on a nail by him, and as everyone seemed to have deserted for their noonday meal he laboriously tried key after key. His straw hat tilted forward as he bent down and knocked off his glasses, but he took no notice. At last the click of the lock rewarded him, and he pushed open the door. As he entered the stables a shock-headed youth came round the corner, carrying a bucket of water. His round eyes saw a slim man in a grey suit and a straw hat. Nothing more. Yet the bucket of water fell from his hand, and, with a shout, he turned round and ran as fast as his legs and wind would carry him in the opposite direction. It was an incident worthy of notice, but, as it was performed behind Rye's back, it did not answer its purpose of distraction.

With a shout, he turned round and ran as

fast as his legs and wind would carry him,

The door fell to with a slam, and the outside world, with its vexation and humiliation, was shut securely out. The stables were delightfully cool and dark after the glare of the gardens, and Rye felt instinctively soothed. He lit his pipe, and, after carefully extinguishing the match, puffed away with growing contentment.

The yellow straw rustled under his feet, as he paced up and down, reviewing the morning's incident. The scene whirled before his eyes like the pieces of a kaleidoscope. The rearing horse dashed before him, with the ring of grinning faces dancing round. Bobbie's sweet face slid down from the sky, and the white of her dress cut into the circle. Blotches of shadow were succeeded by bars of yellow sun, and broad patches of colour were scattered everywhere. A wedge of blue, which was the sky, mingled with a slab of green, which was the turf, and over it all shot the hoofs and mane of the diabolical horse.

Rye groaned. He wondered where the wretched brute was stalled. There was no sign of him here—nothing but some quiet ponies covered with striped cloths.

He took another turn. His pipe went out, and as he sucked its cold stem he had a sudden foretaste of the future reft of Bobbie. It may have been the empty pipe, but somehow life was empty then. The classics appeared squeezed of their interest, and in comparison with Bobbie's vitality Virgil and Homer seemed to have been dead rather longer than usual.

Rye lit another match, and its flame, revealed a new sight. One of the walls was pierced by a narrow window, through which the sun poured in a shaft of gold. Now this was obscured by dark masses. He felt for his glasses, but to his annoyance they were not in his pocket, and he remembered that he had left them lying outside the stables. He stamped his foot crossly, and it may even be surmised that he said a short and expressive word. But he had a right to be annoyed, for without his glasses he felt himself to be as helpless as a baby.

Again he strained his eyes towards the window, but was only rewarded by a blur. Yet he thought he could distinguish white patches that looked like faces, and something bright, suspiciously like Bobbie's hair. He stood for a minute in indecision, and then he approached the window. With every step the dimmed outlines grew sharper, and presently he saw that his conjecture had been correct. Four faces were staring at him through the cobwebby glass, and one was crowned with Bobbie's fair halo.

Rye turned on his heel savagely: this was playing the game too low. The Flower family seemed in ten minutes to have skipped a few centuries of time, and, not content with their first rôle of primeval savages, had introduced into their manner the customs of the Inquisition.

The thought of those watching eyes gloating over his discomfiture goaded Rye to fury. "Cads!" he ejaculated, in his rage. He crossed over to a dark corner where he would be out of their range of vision, and started to finish his pipe. A pony stamped restlessly about his box and came out of his stall. He passed close to Rye, and then scudded back as a low knocking commenced on the door.

Rye's teeth bit through his amber mouthpiece. "Hanged if I'll contribute to their humour any more," he muttered. His pipe was a thing of the past, and he had only a fervent desire to leave the stables. But he would not go through the door, where the hammering was growing more insistent every minute. He crossed to the other end of the stable. Here a heavily-bolted door barred his way, and he began to tackle the bolts in the hope that it might lead to an outlet. As he fought with the heavy bars the sound of the knocking increased in volume, but he took no heed. Furiously pressing down the rusty iron, he managed to force the door open. It was evident from the effort it involved that this means of communication was seldom used.

He found himself in a smallish stable strewn with straw. At one end was a sort of rough stair, leading to a loft, and moving up there, among the hay, he saw what appeared to be the uncouth figure of a stable-boy. The room was shady, but his shortsighted eyes, peering about, found what they were seeking. The door at the far end really looked as if it led out to the grounds, and he crossed over and rattled at it, but only to find to his disgust that it was locked on the outside.

"Hi!" he called to the boy, "can you open this door?"

"Hi!" he called to the boy, "can you open this door?"

The boy turned his head, but at that moment Rye's attention was attracted by the scurry of feet outside. The key turned in the lock, the door was flung open, and he stepped again into the sun to find himself confronted with the Flower family. Yet even as he passed the doorway and the door slammed he had a curious sensation. It seemed as if someone had just touched him with the tip of a very powerful finger, and, in spite of the heat, a cold jet suddenly spurted down his spine and his knee-joints suddenly gave way. Lost in his surprise at this unaccountable spasm of fear, he heard as in a dream, through the thick wood of the door, the sound of a muffled roar.

The faces round him were pale and perturbed, and Rye's brain began officiously to work on its own account. In spite of himself, a horrid suspicion persisted in knocking at his heart. Had he stumbled on a secret of the Flower family? That scream had a maniac tone in it. He shivered at the thought.

As he glared round at the circle of faces the elder Flower suddenly thrust out a hairy paw.

"Shake!" he said. "I don't go back on my word, but when I make a mistake I own up to it. I was mistaken just now. Shake!"

Rye shook, but frigidly. The next minute, the younger Flower and Mole started a course of pump-handling.

"We spoke too soon, I reckon. You Britishers are plucky enough, come to that, but, mebbe, the way's different."

"Yes, that's it. We sized you up wrong."

These overtures left Rye with an aching arm, bruised fingers, and a still stronger sense of mystification. There was something strange about the Flower cordiality, something he could not fathom. As they walked back to the house they all talked boisterously, with an effusive friendliness that was in marked contrast to their former coldness. Yet Rye kept intercepting furtive glances and questioning looks that were shot at his face. It was plain that he had tumbled on a hornet's nest of mystery, and no pleasant mystery either, as the inhuman howl testified.

When they reached the flower-garden, Bobbie, who had walked silently ahead, suddenly dismissed her male belongings "Walk on, please! I want to speak to Mr. Rye alone."

The men grinned and obeyed. Rye waited in surprise at this fresh development. But Bobbie stood with her head bent, apparently occupied with scraping a hole in the gravel with the tip of a beaded slipper. When she at last spoke her remark was quite irrelevant. "Isn't that a lovely aster?" Rye stared hard at the flower, and answered with growing surprise, "Yes. Very early for them, though," he amended.

"Come along." Bobbie dragged him on impetuously. She took his arm, and he now saw that her cheeks were pale and streaky and her jauntiness had given way to an unfamiliar misery.

"Why, what's wrong, Bobbie?" he asked.

"I've been crying," was the direct answer.

"Why. what about?"

"You."

"Me? But why—why?"

All her caprice seemed to have been driven out of Bobbie.

"Oh," she answered, "because we riled you so, and I do like you—better—better than I've ever liked anyone before."

She stopped, and though Rye completed her sentence it must be admitted that it was Bobbie who practically proposed.

Rye walked back to lunch with Bobbie nestling on his arm, rapture and astonishment striving for mastery. This had indeed been a morning of surprises. As they reached the dining-room the girl hung back.

"I've something of yours," she said—" your glasses."

She perched them on her nose and squinted alarmingly at him. Then she slipped them in his pocket and gave him a gentle push.

"Now, just go straight in and ask dad."

Rye hesitated. In spite of his surprising conquest of the beautiful heiress, whom he had that morning in fancy bestowed as an ornament to the peerage of England, he felt doubtful of his reception.

"I think I'll wait until after lunch. He doesn't care much about me, I'm afraid."

"No; you ask him now, before lunch. He'll enjoy it all the more. Dad thinks all the world of you,"

Apparently Bobbie was right, for the elder Flower beamed upon him, after he had sorted out Rye's tangled tale, and at once, and with no reservations, Rye was accepted into the bosom of the family. The younger Flower, and Mole also, vied with each other in expressing their delight.

But it was all too sudden and too effusive. Rye spent a blissful afternoon with Bobbie under the chestnut tree on the lawn, but somehow, underneath all his rapture, lay the uneasy feeling that he was being bribed. Through the murmur of the bees, and the hum of the wind through the trees, before the crimson of the roses, and even between Bobbie's kisses, came the faint echo of that maniac roar.

At four o'clock they were disturbed by the family, a visitor, and tea. The family gathered round a solid table, set in the shade of the chestnut, and prepared to attack the mounds of raspberries and cream with the appetites of schoolboys. But their hospitality disconcerted their visitor, a thin-lipped, hard-faced man, who was the owner of the adjoining seat.

"Only a cup of tea, nothing else," he protested. "I've very little time, and I was hoping that you would take me round your place. I've heard so much of your grounds, and the collection."

"Why, yes! Come along, all of you!" The elder Flower jumped up gleefully. To do the honours of his gardens appealed to him even more than the solid delights of tea. The others dutifully followed in a string, waiting meekly while Flower dilated over some particular beauty of horticulture, and the Hon. Bill Groves pursed his thin lips, admired, and envied.

Presently they threaded their way towards the scene of the morning's adventure, and Rye's heart beat faster as the familiar long building came in sight.

"So you've heard of this already?" remarked Flower. "Come to the window and look in. It's not safe to go inside; but have a squint. Of course, the place isn't properly built yet, and this is only a makeshift. Did you ever see finer brutes?"

For the second time that day four heads were pressed to the window. Flower grinned at Rye and closed one eye.

"You don't want to see them," he said, jovially. "Seen 'em at closer quarters, haven't you?"

But, with his glasses now perched securely on his nose, Rye was seeing them for the first time. His heart gave a violent leap. Instead of the quiet ponies in their striped cloths, here were several fine specimens of an animal that is noted for its ferocity and strength—whose kick and bite could have speedily reduced him to the state of an inoffensive doormat for their vicious hoofs.

"Fine zebras!" remarked Flower. "Unruly beasts! I've a gorilla in the next place," he continued. "Come and have a look through the window. We'll soon have him properly fixed up."

Rye staggered up behind the others. He was actually rather a nervous man, and these revelations made him feel physically ill. With startled eyes peering through the dim glass, he saw squatting in the shadow the enormous figure of a gigantic ape. The nutlike eye, the powerful jaws, and the width of the chest all appalled him. The brute slowly shook his shaggy head from side to side, and mouthed gravely to itself in absurd parody of a man, but when he saw the people at the window he made a bound towards them and gripped the bars with his huge arras, grinning with rage.

Flower grinned back with pride. "Soon make mincemeat of anyone, wouldn't he? Now I must tell you a little yarn. This chap here, Rye — he's to be my son-in-law, and proud I am of it, too—well, we sort of ragged him this morning, because he warn't set on trying one of our horses. We said p'r'aps more'n we meant, and he just set out to show us that a Britisher don't know the white feather. Now, what d'you think he did? Why, man, it was grand! Just went and smoked his pipe among those zebras. There's nerve! But, mind, it was going too far. We tried to make him budge. But this puss of mine had dared him, so what d'you think he did next? Why, left his card with the gorilla. Mind, that was chunk-headed folly, but it was grand all the same. Near shave he had, too. Yappo all but grabbed him. But, for all cool nerve, it licks creation. For quite ten minutes he held his life in his hand, and, so far as I could see, his pipe never went out. How's that for a man?"

They all turned and looked in reverential admiration at the man, who, from his abject appearance at that moment, looked incapable of offering fight to a mouse.

They all turned and looked in reverential admiration at the man

"Now come and see the antelopes," urged Flower.

Rye, muttering an excuse, turned on abruptly his heel and left them. He walked in a dream, till he came to a shady part of the lawn, where a plaster Pan played to a clipped yew. Then he took out his pipe, and smoked and thought. He told his pipe a good many things as he watched the blue rings curl upwards. He explained that everyone on the earth was a toy that Fate played with—that free will was nothing, and that Fate was everything. That Fate stuck them all up for a gigantic game of ninepins, and that Fate threw the ball. He had had some close shaves that day, but he wasn't bowled. Let things stay as they were! It was all Fate!

But his pipe only said one thing, and that thing was, "Be a man." The shadows were falling when Bobbie came round the corner and found him there. His face was pale and his eyes heavy, for the history of his first smoke had been repeated, and his pipe had beaten him.

"Bobbie," he said, abruptly, "you know I care for you more than anything in the world, so perhaps you'll understand a little—just a very little—of how hard it is to say what I'm going to. It is this: I am not brave. I am a coward. I never knew that your father had a collection of wild animals. I walked in there by accident, and I couldn't see them without my glasses. But I've been frightened ever since. So—it's all over."

"Indeed, indeed, it's not!" Bobbie's hug was a very fair imitation of the gorilla's grip. "Dear, I knew all the time. I found your glasses outside, and I tested you the first thing. You blind old bat, you called a geranium an aster! But when I saw you in that dreadful place I knew I loved you then, all the way through."

"Love a coward?"

"You're not. We were wrong. You would have been mad to mount that horse. And you've proved you're brave. The others would never have dared to own up they were funks. I guess there are two sorts of bravery."

"Well, I'm glad you don't give me up," said Rye. "But I'm afraid the others will."

"They won't. Only I'll tell them myself. And you are never to mention this again. Promise!"

Rye promised, and apparently the Flower family accepted Bobbie's view, for their son-in-law always remained their hero.

Yet, if the truth were known, perhaps Bobbie's version of the story was incomplete. But, whatever she said, she sealed the lips of her hearers, and the great "dare" incident was never openly mentioned. The fortunes of the game left Rye standing, even if it was Bobbie's hand that jogged Fate's elbow, so that the dread ball slid harmlessly past the ninepin.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.