RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

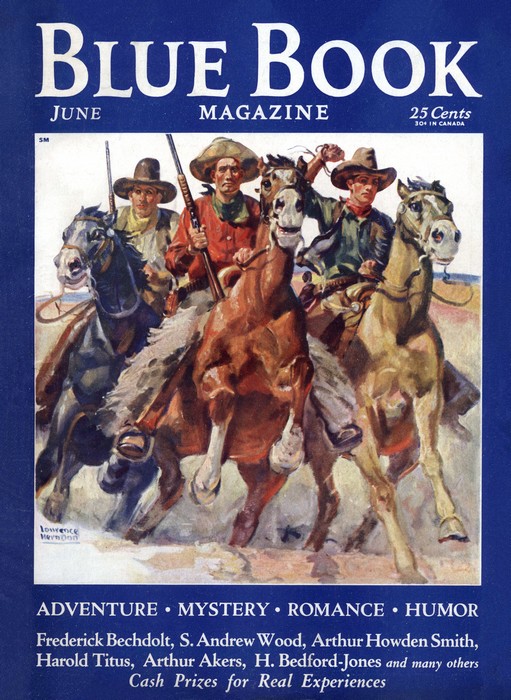

Blue Book Magazine, June 1932 with "Code K"

WHILE convalescing from shell-shock suffered during the First World War, the English journalist George Valentine Williams, who served as a captain in the Irish Guards, took up writing "shockers" on the advice of the prominent genre writer John Buchan.

With The Man with the Clubfoot (1918), Williams introduced Dr. Adolph Grundt (or "Clubfoot"), who became one of the great "master criminal" villains of thriller fiction of the 1920s and 1930s and launched Williams on a lucrative career as a crime writer.

Between 1918 and 1946 Williams published twenty-five crime genre novels and two short story collections.

Many of these works are master criminal thrillers in the Edgar Wallace/E. Phillips Oppenheim mode (some with Clubfoot, some not), but some are detective novels (or at least "mystery" yarns) as well.

I was dealt a terrific blow from behind; a wave of

light danced before my eyes—and I knew nothing more.

"KILLING'S no murder" is the rule of war. But that means the war of the front line, where the individual combatant is no more than an impersonal unit of the whole striking force. It is a different thing to start out from London as I did, one night in 1917, to put a man to death in the staid and unemotional atmosphere of neutral Holland.

Not that I had any compassion for S-237. Thanks to his treachery, my poor friend, Philip Brewster, best and bravest of our little band of brothers in the British Secret Service, was lying in a nameless grave at Antwerp. More than this, as long as S-237 went free, the lives of a dozen more were at his mercy, to say nothing of our men at the front whose very security depended upon the reliability of our reports from the German back areas. S-237 had to die and I had no compunction about being the instrument of justice. But I do not mind admitting that, as my cab rattled me over the Amsterdam cobbles, the loaded pistol in my jacket pocket was like a weight on my heart.

S-237 was a figure of mystery. No one in our organization had ever set eyes on him; he had been engaged blind by reason of several excellent reports he turned in regarding conditions in occupied Belgium. He had stipulated that he would have nothing to do with our center in Holland. London, therefore, communicated with him direct under the name of Piet Arnholz at an Amsterdam address. It was generally inferred that the name, like the address, was of the accommodation order.

He traveled for us between Amsterdam and the towns of occupied Belgium and for a time proved extraordinarily useful. Then Code K, as the Germans called it, used by them in their radio communications between their espionage center at Amsterdam and Army Headquarters, came into our hands. We were in the habit of intercepting these radiograms which now we were able to decipher. Not for long, however. The Germans promptly became cognizant of the leak and changed their code. But not before we had obtained clear proof, from a message thus decoded, that S-237 was a double-crosser—that is, an agent in the pay of both sides.

Now the double-crosser is the commonplace of all secret-service work. One day we would lure an agent away from the Germans; the next day they would buy off a man of ours. Both sides commonly kept known double-crossers on their books for the purpose of feeding false information to the enemy. But S-237 was in a different category. We had trusted him; he knew too much; and so his removal was decreed.

We baited the trap with money, which is the only argument the international riffraff constituting the rank and file of secret-service organizations understands. Word was sent to S-237 that for the purpose of a personal interview an emissary was being dispatched to Amsterdam with the sum of three hundred pounds as a mark of appreciation. True to form came the answer back: S-237 would meet Captain Dunlop (an accommodation name which most of us at Headquarters used at one time or another) two days hence at the Café Monopol at four p.m.—the emissary to wear a flower in his buttonhole for easier identification.

With a red carnation in my coat I waited half an hour —an hour—for my man. The average double-crosser has his ear pretty close to the ground, and as time went on without anybody accosting me, I began to suspect that S-237 had caught a whisper of trouble brewing. I was not sorry for the respite. If I could have met the ruffian face to face, I told myself, the memory of poor Phil Brewster's fate would have sufficed to arm me with the necessary resolution to go through with my mission. But this waiting got on my nerves, and I looked about for a suitable diversion.

I found it across the floor of the crowded cafe, not a dozen yards from where I sat. I must have been subconsciously aware, before focusing my attention upon her, that the woman was attractive, for suddenly I found myself studying her with interest. I liked little things about her—the way, for instance, her glossy, gold-brown hair was looped up over her ears and the half-moons that her long-fringed lashes made on her cheek as she bent her eyes to her newspaper. She was self-possessed and unassuming—quietly dressed, too, and with good taste. It seemed to me, once or twice, that she glanced up at me from behind her newspaper and then I had a glimpse of eyes luminous and compelling. On my way out of the café—at close on seven o'clock—her glove lay on the floor, and—

Well, we had a drink together. She seemed to have no prudery—she was quite willing to talk to me. Her name, she said, was Marie Louise Hesselink and she was a Belgian refugee employed as a commercial traveler by a Hague milliner. And she had a way of looking at a fellow out of those large eyes of hers—

Quickly my mind was made up. Tomorrow, the Germans say, is also a day; time enough then to launch out upon the laborious search for S-237, if he had not already made himself scarce—we had ascertained that the address he had given us was merely a tobacconist's.

"Madame," said I, "I am a stranger in Amsterdam and so are you. Will anything be added to the meager store of human happiness by two aliens in this great city dining in separate loneliness?"

She laughed in her quiet way. "If you're asking me to dinner, I warn you I'll accept."

"That was the rough idea," said I. "And after dinner we'll find a music-hall, and see if we've forgotten how to laugh."

Then she excused herself, explaining that she was staying with a girl friend and must telephone to say she would not be home for dinner.

We dined at an old-fashioned restaurant she knew of near the Bourse and afterward sat in a box at a funny little café chantant. Our conversation followed much the usual lines of conversation at such fortuitous encounters; that is to say, we gave one another our general background—in my case, somewhat imaginative—and then drifted from one topic to another. I had told her my name was Dunlop and that I had come to visit a friend of mine, one of the survivors of the Royal Naval Division interned at Amerongen and she described how, an orphan, working in a hat-shop at Ghent, she had fled before the German invasion and found refuge and a job in Holland.

My sole object in inviting her to dinner had been to take my thoughts for an hour or two off the business that had brought me across the North Sea; and in this I had certainly succeeded. But not in the way I had imagined. I soon discovered that this girl—she told me she was twenty-seven—was not just a little seamstress in search of adventure. She was highly intelligent and expressed herself well and while she did not apparently object to my flirting with her in a desultory fashion, she handled the situation with all the dexterity of a woman of the world. Her self-possession was extraordinary and she had a resolute air which intrigued me greatly.

After the theater I suggested a glass of beer at a café. But she explained that her friend would be waiting up. The house was close by; I might walk back with her, and if her friend had not gone to bed, I could have a drink with them at the flat. Curious as to how the adventure would end, I accompanied her to a gloomy old house on a canal at the back of the Town Hall. There, on the top landing, she produced a key and, bidding me wait a second, let herself in.

She was back in a moment, beckoning. In the hall she took my hat and ushered me into a dark sitting-room. I was in the act of entering when she called to me, "Just a minute!" I turned to her casually.

Secret-service work quickens the intuitive sense and I was immediately aware of an air of tense excitement about her. Suddenly I scented danger; but it was too late; on the instant I was dealt a terrific blow on the head from behind—a tremendous impact but soft (the weapon was a rubber "life-preserver," I assumed afterward); a wave of scarlet light danced before my eyes—and I knew nothing more until the worst headache I have ever experienced restored me to consciousness.

I was lying on a bed in a small, darkened room. I felt weak and very sick. But as my senses cleared, my feeling of moral abasement transcended any physical sensation. I cursed myself for every kind of fool—to have let myself be lured into such an obvious trap was disgraceful! The girl, of course, was a decoy—S-237's decoy. He had simply dispatched her to the cafe to wait for the man with the flower in his buttonhole and bring him to where a hired bully, or perhaps S-237 himself, lurked in ambush. S-237 had turned the tables on me. I had come to kill him; but it looked to me as though our rô1es were reversed!

My pistol had been taken from me; my wallet with the three hundred pounds in notes and my passport,—in the name of Dunlop,—were gone. The door was locked and a padlock secured the heavy shutter that barred the single window. My first impulse was to hammer on the door, cry out, vent in violence my exasperation which, to speak the truth, was rather against myself than my captors. But I mastered my feelings. Before I could grapple with my desperate situation I must know how the land lay. And the time to do it was now, while my captors believed me still unconscious.

The light that filtered through the shutter showed that it was broad daylight outside. I looked at my watch; it was twenty-five minutes past one. I must have lain there for more than twelve hours. I heard voices through the door—voices speaking German, a deep, guttural voice and a lighter voice which I recognized as the girl's. "He was still unconscious an hour ago," I heard her say. "We'll take another look if you like, but I expect he'll have to sleep it off."

"Jan struck too hard, the fool!" the deep voice grumbled. Now there were footsteps outside the door. I flattened myself against the wall so that the door in opening would conceal me. I reckoned they would go straight to the bed, giving me a chance to make a dash for liberty. But the door opened only a few inches. The girl slipped in, a slim form in the dimness, and crossed to the bed.

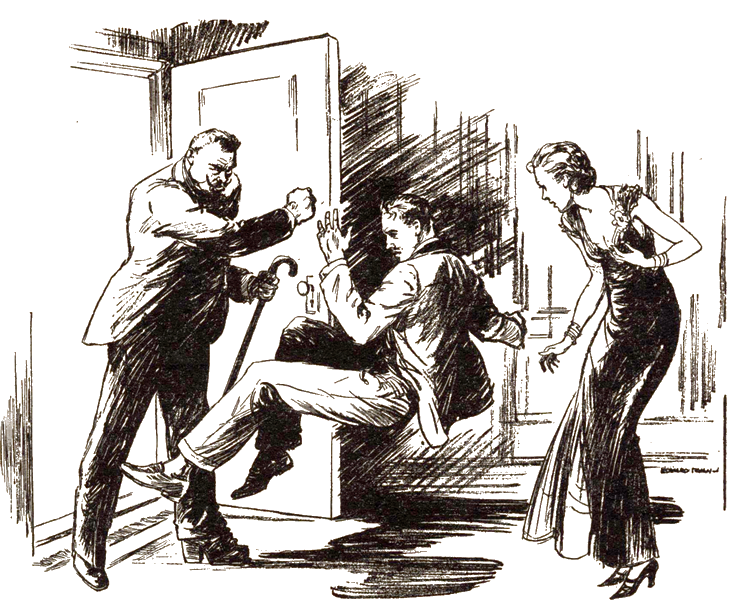

Silently I laid my hand on the doorknob and silently drew the door toward me. But as I stepped around it I came into violent collision with a burly form. A harsh voice roared, "Herr Gott!" and a great hand drove at my chest, sending me reeling backward into the room. I sprang forward again, only to be brought up short by a brusque, "Still, or I shoot!"

A harsh voice roared, "Herr Gott!" and a great

hand drove at my chest, sending me reeling.

It was not so much the threat or the long shining muzzle enforcing it, as I scrambled hastily to my feet, that halted me. A vast shape seemed to fill the whole doorway. Before me stood the notorious Dr. Grundt, ablest and most ruthless of the whole German corps of spies. Once again I marveled at the herculean proportions of the man, the tremendous span of that barreled chest, the swelling muscles of arms and back and the gorilla-like suggestion of the head—the projecting, pointed ears, the wide, flat nose, the beetling, shaggy brows, the hot and savage eyes. Sheer surprise sent my wits racing to grapple for the connection between a cheap double-crosser like S-237 and his woman ally, and this man of authority who, as head of the Kaiser's personal Secret Service, was perhaps the most redoubtable of the powers behind the German throne.

He contemplated me in silence, his fleshy lips curled in a triumphant sneer, one enormous, hairy hand grasping the pistol, the other resting on the heavy cane he used by reason of the clubfoot which gave him his familiar nickname.

"Well, Herr Doktor," the girl spoke up behind me in a voice curiously defiant, "there he is! Captain Dunlop, one of their aces! Now do you believe me?"

With a large red tongue the cripple moistened his lips and nodded. "Good work, good work, meine Liebe," he muttered. He hobbled a pace into the room. His dark eyes ferreted in my face. "Captain Dunlop, hein? So!"

Now, as you who read my reminiscences are aware, Clubfoot and I were not strangers. I was not disguised, and I had no doubt in my mind that he recognized me. But he gave no sign, and I had the impression that for some reason or other the old rascal wished my real identity to remain a secret between us.

The girl laughed. The sound struck chill upon my heart. She was a good actress; she had played her part perfectly. The thought that all her friendliness and sympathy had been assumed to trap me gave me a feeling of nausea. "A fool, like all Englishmen!" she jeered. "Well, Herr Doktor, what's he worth?"

Grundt chuckled softly. "He's worth more dead than alive, my dear, and that's a fact."

Her hard laugh rang out again. "Jan will take care of that. And no questions asked. But it'll cost you five hundred gulden."

"Practical as always, my dear," he commented genially.

She snorted. "If you think that one can live on what you Germans pay—"

Grundt's eyes narrowed. "What time is your train?" he demanded brusquely.

Her face lit up. "Then I'm going on this mission?"

"Certainly."

"The Bale express leaves at two." She glanced at her wrist. "If I hurry I can make it; my things are packed. What about the German frontier authorities?"

"Arranged. You have your German, Swiss and French visas?"

"Yes." She paused. "—And the cash?"

"Waiting for you at the other end."

She pouted. "I have only your word for it."

He laughed dryly. "You know my rule: cash on delivery. The money was wired this morning."

She shrugged her shoulders. "What about—" She glanced at me.

"You can leave—ahem—Captain Dunlop to me."

"Jan's about, if you want him," she said casually, and I felt a cold shiver go down my spine.

"Thank you. Bon voyage, my dear!"

"Au revoir, Herr Doktor!"

"Send me a postcard from Paris," he called after her.

With the closing of the door upon her, he turned to me. "And now, lieber Clavering, you and I must have a little talk. Sit down!" He produced a cigar-case. "Smoke?"

My head still ached violently. But simply to gain time I drew up a chair. I knew from experience that my old adversary was never more dangerous than when in these expansive moods. He gave me a light for my cigar, lit his own, and thoughtfully contemplating the glowing end, remarked: "And what about S-237, my friend?"

Taken aback as I was by his question, I made up my mind, on the spur, of the moment, to lay my cards on the table. I reflected that the whole rabble of hireling spies stank in the nostrils of all who, like Grundt and myself, were in the game not for money but in the line of duty; besides, a double-crosser was a common danger.

"S-237 will betray you as he betrayed us," I answered resolutely. "If you want to know, I came to Amsterdam to put him out of the way."

The bushy eyebrows were drawn together in a sudden bewildered frown. "Then why didn't you?"

I shrugged my shoulders. "He didn't keep the appointment. And I was fool enough to take this girl of yours out to dinner."

Clubfoot laughed. "So? Well, I don't blame you— she's as clever as they make 'em. And how long has S-237 been working for you?"

"For more than three months."

The hot eyes flashed fire. "So? Any proof?"

"I had three hundred pounds for him in my wallet. Ask the girl what became of it."

The big German grunted and sawed the air with his hand. "Give me the facts!" he growled.

It afforded me a grim satisfaction to obey Grundt's request. I was careful, of course, not to give away any information of value; but I disclosed the fact that it was S-237 who enabled us to lay hands on the German spy Otto Riedl, who committed suicide in prison while under sentence of death. I did this with a purpose, for it was generally understood that Riedl's orders emanated from a very high quarter in Germany. At the mention of Riedl's name I saw Grundt's face darken.

When I had finished he was silent, his lips pursed up in thought. Outside the front door slammed. Clubfoot looked up quickly, his eyes spiteful, his features aflame with a sudden resolution. He took a pad from his pocket, scribbled a few lines, tore off the sheet and handed it to me. "That message goes by radio to our Army Headquarters this afternoon," he explained.

Much bewildered, I read: "Kindly refund to me here the sum of ten thousand francs which I have asked Paris to pay out to M-44 on arrival."

My glance questioned the heavy face.

"M-44 in the German service, S-237 in the British," said Grundt.

I stared at him. "You mean that this girl is—God, what a fool I've been!"

He glowered. "I told you she was clever! It was just as well you didn't guess. Frankly, would your British sense of chivalry have allowed you to kill a woman?"

"No," I told him.

Raspingly he cleared his throat. "Bah! I know no such scruples." He stood up. "Mein lieber Clavering, there's nothing I should like better than to hand you over to the tender ministrations of our friend Jan. But this is neutral ground and I have no intention of compromising its usefulness by creating difficulties for the Dutch authorities. Since you've told me what I came here to find out, you're free to go; but I suggest you return to England without delay."

I suppose he read the conflict of emotions in my face, for he added quickly: "You needn't worry about your mission. It will be accomplished." His tone was stern.

"How do you mean?" I faltered.

"You're doubtless aware that we've recently changed our code between Amsterdam and Army Headquarters?"

"Well?"

He clicked with his tongue impatiently. "Where are your eyes, my friend? Take another look at that message I showed you!"

I glanced at the sheet and then noticed, written across the corner: "For coding—Code K."

Then I knew that Grundt had taken my mission out of my hands, for anything sent by Code K would be read by the French and ourselves, so that that message was virtually the little lady's death-warrant. Sure enough, on returning to London next day, the first thing I heard was that the French were on the lookout for M-44 at the Swiss frontier of France. She was trailed to Paris, arrested, and sent before a court-martial—and two months later faced the firing-squad at Vincennes.

I have never been able to determine what action I should have taken, had I identified her as S-237 that afternoon at the Café Monopol.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.