RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

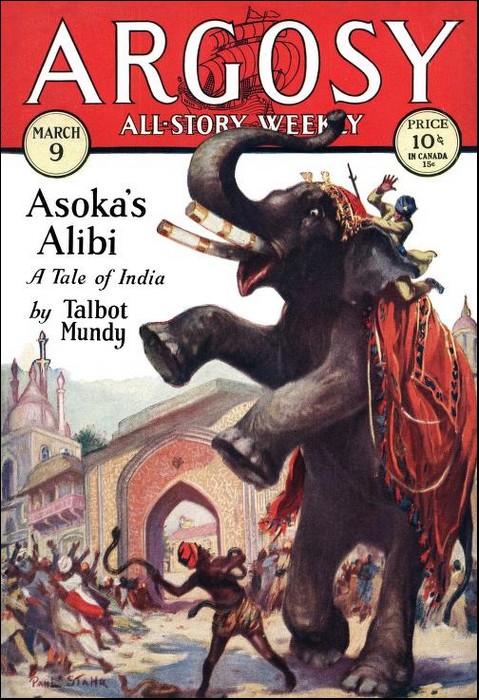

Argosy All-Story Weekly, 9 March 1929, with Part 1 of "Asoka's Alibi"

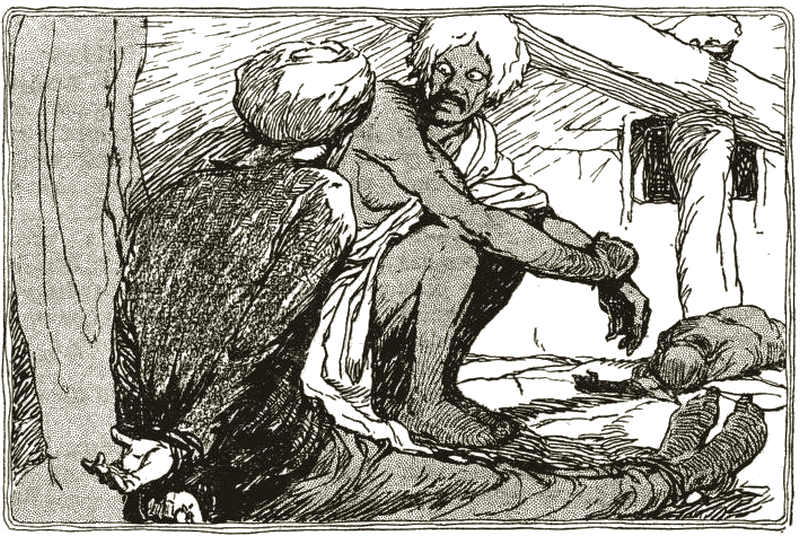

Maraj glared at him—a monster to whom

life was death and cruelty was beauty.

"RECKON maybe I'm nutty," said Quorn to himself. "Hell, supposing I am! So is Narada. Elephants is the only sane folk hereabouts."

To comfort himself he looked up at Asoka, the tallest elephant in captivity, whom only he could manage at the best of times. At other times Quorn had to ride him as a fury rides a typhoon.

"You, you big stiff, if it weren't for you I'd pull my freight for Philadelphia and drive a taxicab again. If I might take you along I'd join a circus. This here circus gives me the willies."

He was referring to all Narada, not merely the elephant lines. Narada is close enough to Rajputana to be soaked with a sense of worn-out history. Treaties and its mountains have kept railroads at a distance, and the news comes dim, diluted, and distressing, by mail and word of mouth, so that people are only aware that the world is changing, without knowing why, or how, or what the changes mean.

They feel backward, and resent it, but they keep up the ancient customs for lack of intelligible new ones. Accordingly, for eleven months of every year Narada is piously miserable; during the twelfth month it is impiously mad and happy—more or less—always with a feeling that happiness has to be paid for, and, though the gods are kindly, there are as many vengeful and resentful devils as there are gods.

The carnival falls at the craziest season—April, when the heat is almost intolerable and nobody has too much money, having paid the taxes and the money-lenders' interest, so there is a fine feeling of equality, with common enemies to execrate.

There is also a yearning in common to cut loose and thumb rebellious noses at authority, so the underpaid and not too numerous police receive a lesson in self-restraint; a policeman's head, struck by a long stick, cracks as easily as any one's; the police station is of wood and would make a lovely bonfire. So the police stand by, while Narada eats, drinks, dances, sees the sights, marries and gives in marriage, is irreverent, sings naughty songs, quarrels and makes it up again, wears out its finery before some of it is paid for, and does all those things that good books say should not be done—because next month it must begin all over again working for the landlord and the money-lender.

The sun beats down on that exuberant emotion and ferments it, under the eyes of Brahmin priests, who understand a little of the law of give and take. The more impertinences now, the more abject the reaction presently; the little money fines and penitential gifts will mount up to a huge sum in the aggregate. Meanwhile even the lousy sacred monkeys feel the will to be amused and steal with twice their normal impudence, acquiring wondrous and enduring bellyache from plundered sweetmeats.

Passion of all sorts blossoms, and there are more sorts of it than most men guess. Scores of species of holy mendicants arrive from all the ends of India; so do the astrologers, clairvoyants, ordinary fortune tellers, conjurers, snake charmers, acrobats, sellers of love philters, preachers, teachers of how to get rich quick and gamblers to show how swiftly to get poor again, owners of fighting quails and fighting bantams, story tellers and proprietors of peep shows. Each sort makes its own noise, and the din adds madness to emotion.

Murder stalks abroad. Why shouldn't it? Life and death are one, admits Narada. Death must have its innings. We might even see a murder, and get excited about it, and help to confuse the police, if we are lucky. Hot? Yes, horribly. Dusty? Whew! We sweat, and dry dust sticks to us. But let's go and see the sights, the free ones first.

SINCE the legendary Gunga sahib reincarnated and

became Ben Quorn, and the Ranee made him superintendent

of her elephants, the royal elephant lines have been the

finest circus in the world. So Quorn had thousands of

visitors all day long; and because he was homesick for the

gray fogs of Philadelphia he was more than usually kindly.

His strange, agate-colored eyes had frightened people in

Philadelphia; but here, under a light blue turban, they

suggested rebirth from the storied past, so that it was no

wonder that people who believe implicitly in reincarnation

should insist he was a national hero come to life again.

Was he not exactly like the image of the Gunga sahib on the old wall of the market place? Had he not miraculously tamed the terrible Asoka when Asoka ran mad through the city? And was Asoka not the name of the sacred elephant the Gunga sahib rode in the ancient legend? And wasn't it fun to know how mad the temple Brahmins were, since they had had to bow to public clamor and admit that the Gunga sahib truly had come to life in the body of Quorn from Philadelphia?

Some one—nobody knew who, but some one—had explained that Philadelphia means the City of Brotherly Love.

Could the Gunga sahib come from any better place than that?

So Quorn answered questions and wiped sweat from his face until his throat was dry and he was so weary that he had to sit down on the upturned packing case beside Asoka. There he could watch all of his four and thirty elephants, each under its own enormous tree, within a compound wall that was carved from end to end with legends of gods and men.

Since Quorn came, every one of the elephants had learned new tricks; and he was generous, he staged a fresh performance every hour or so. The Ranee was generous, too, or else Quorn had persuaded her; there was free lemonade in such amazing quantities that the mystery was where all the lemons came from; and the lemonade was pink, which was a miracle, but it made Quorn feel less homesick.

He had always loved a circus—always had loved elephants, although he never knew why and had never had dealings with them until he came to Narada as caretaker of some abandoned mission buildings. Accident, according to his view of it, or destiny, according to local conviction, had caused him to climb on Asoka's neck one day when he was idly curious.

Asoka had chosen that moment to go into one of his panics, had burst his picket-ring and had run amuck through the city. Quorn had stuck to him because there was nothing else to do: and when the elephant had stunned himself at last against a wall, it was Quorn who gave him water and a cool bath in a garden pond—Quorn who coaxed him back to sanity.

It was in response to popular clamor, and only incidentally as a political move against the temple Brahmins that Quorn had been promptly put in charge of all the elephants. Nobody expected him to make good; not even Quorn had expected it. Miracle of miracles, his love of elephants had proved to be a film that overlay his natural genius for training them.

And Quorn loved his job. But he was lonely.

There was only Bamjee with whom to be intimate—Bamjee, the ex-telegraphist babu, who had sat at his instrument and learned so many secrets, of so many, important people, that he had finally been appointed to the lucrative post of royal purchasing agent as an inducement to hold his tongue.

The only other man to talk with now and then was Blake the British resident, a gentleman so far above Quorn's social standing that, in spite of mutual respect, anything like intimacy was out of the question. Actually, at times, Blake and Quorn were suspicious of each other.

Secretly, Blake was determined, at all costs, even at the risk of his official career, to keep the Ranee on her throne and to support her modernizing efforts. Openly, Quorn was her stanch and loyal servant, cheerfully willing to run all risks and to defy temple Brahmins or any one else in her behalf. But Blake's official position as resident agent of the British-Indian government obliged him to seem critical and sometimes even threatening, so that the two men did not always understand each other.

AS for the Ranee, there was no understanding her at

all. Like Alexander the Great, Cleopatra, Queen Elizabeth

and Napoleon, she had blossomed at the age of nineteen

and burst suddenly into full maturity of intellect and

statecraft. The last of her royal race, she resembled a

marvelous flower on a dying vine, whose whole strength had

gone into this last effort.

Raised within the customary purdah that prevented contact with the outer world, she had contrived; with the aid of Bamjee, who would do anything for money, to import books and to learn three languages. She knew everything that has been printed about Napoleon, Frederick the Great, George Washington, Lincoln and Grant. She had read modern novels, and was more familiar with modern views than many people are who see newspapers every morning. And she had unbelievable courage. She had broken purdah and defied the temple Brahmins.

If she had been ugly it might not have mattered so much, but a beautiful young girl arouses comment, and when she rode through the streets in breeches with no women in attendance, even those who benefited by her modern views were scandalized.

She opened hospitals. She superintended sanitary improvements. She pulled down rat-infested tenements and built new houses for the poor... And—deadliest offense—she defied the Brahmins' wrath by refusing to do penance for having broken the rigid laws of caste.

In consequence, her throne was rather less secure than if it had been raised on powder barrels.. The temple Brahmins were doing their utmost to produce anarchy, so that the British-Indian government would have to intervene and either reduce her to the status of a puppet queen or, possibly, depose her altogether. Everybody knew that. Quorn, in particular, knew it. That was why he staged the daily circus. They were her elephants; they should help to make her popular.

"Not that them Brahmins won't get her," he reflected. "If not one way, then another. Poison." He shuddered. He, too, had to guard against poison. "Snakes. Knives in the dark. Accident. Them Brahmins only has to drop a hint or two and some crazed ijjit sticks a knife in some one else. And if she goes, I go—same way probably."

He looked up at the elephant again. "I'd start for Philadelphia to-morrow, but for her and you, you lump! Do you know what they'd do to you if I should up and leave you? They'd order out the troops and the machine gun."

That was absolutely true. Nobody but Quorn could manage the tremendous beast. And Quorn knew that the Brahmins were trying to stir public opinion to demand the summary execution of Asoka as too dangerous to live. They hoped by that means to be rid of Quorn; he might go home to Philadelphia if his beloved elephant were dead.

Quorn's perfect understanding of that phase of the situation was another reason for his taking so much pains with the daily circus; he hoped to make Asoka as well as the Ranee more popular. But he kept constantly close to Asoka, because Bamjee had warned him that an effort might be made to poison the great elephant with something deadly inserted in a tempting piece of fruit or sugar cane.

Fortunately, Bamjee also was anathema to the temple Brahmins. As the Ranee's purchasing agent it was he who had suggested buying tons of liquid disinfectant and a spray, with which even the sacred temple precincts had been drenched for the protection of the crowds who came in carnival month.

To say that the Brahmins were annoyed with Bamjee is to understate it altogether. They were in a state of fanatical mental constipation on account of him. Nothing could restore their equanimity as long as Bamjee was alive and at liberty to pocket ten per cent commissions for inflicting what they considered outrageous sacrilege. And as long as Bamjee could pocket ten per cent commission, he would commit anything under the sun!

So it was obviously Bamjee's cue to keep Quorn posted as to developments. They quarreled very frequently about the quality and price of the corn and sugar cane supplied to the elephant lines, and Quorn had repeatedly earned Bamjee's contempt by refusing to accept a percentage of Bamjee's commission. But hardly a day passed without Bamjee visiting the elephant compound and pausing for a chat with Quorn. He came now. And, as usual, although he would have hated to have to admit it, Quorn was glad to see him.

"MARAJ is in town," said Bamjee.

"The hell you say! Tell the police."

Bamjee was a pleasant-looking little man, in a gray silk suit and a turban of the same color, blinking through platinum-rimmed spectacles. But he could look as contemptuous as the devil himself. The first part of his answer was drowned by the noise of a snake-charmer's bagpipe and the drums of itinerant troupes of acrobats, but presently he came closer to Asoka and sat on a box beside Quorn.

"The police would resign in a body," he said, "if they were told to capture Maraj. Self also. Am get-rich-quick exponent of materialistic fallacy of me first—fallacy because of risks incurred in course of same. Like any other speculator, might go broke. Like any other egotist, might tread on toes of wrong rival and be disemboweled with a dagger—funeral tomorrow afternoon, and nobody, not even you, to pity me, because I took too many chances. But there is one chance that I do not take. I do not monkey with Maraj."

"Hell," Quorn answered. "One mean murderer, without caste or backing—who's afraid o' that man?" He knew better, but he wanted to draw Bamjee.. "I've heard say Maraj is one o' them Chandala people—folk that are reckoned worse than hyenas—ain't allowed in cities—lower, than sweepers—insect-eaters—bums—filthy, no account savages too skeered to look at you excep' sideways."

"They are," said Bamjee. "They are worse than that. It may be true that Maraj is one of them. But have you heard of Thuggee?"

"Thugs?" said Quorn. "Who hasn't? They were stamped out. They were the guys who used to wander about the country killing total strangers with a handkerchief—just for the love o' killing. Am I right?"

"Yes, but they were not stamped out. They invented another way of killing, that is all. Death by suicide. There is humor in that. It is better than murder. He who is murdered is not guilty of his own death, but whoever commits suicide is doomed to wander endlessly in total darkness, earth-bound on the lowest layer of the astral plane. All religions seem to be agreed on that. Even I, who have no religion, nevertheless believe it. This new form of Thuggee, therefore, dooms its victim to almost endless misery in an astral madhouse. Maraj invented it, or so they say. His allies are the Chandala, who are allowed to rob the bodies and who cover up his tracks and run his errands. You can guess who his employers are, can't you?"

"Do you mean them temple Brahmins pay him?"

"I am not so crazy. And they are so far from being crazy that they pay for nothing. A hint—that is enough. Not even such a cunning devil as Maraj could last long unless he had protection. Nothing for nothing. How does he pay for protection? He acts on hints. He overhears two Brahmins saying so-and-so is an undesirable. There is another suicide. Nobody guilty—nobody caught—only a whisper, and the name Maraj is more dreaded than ever."

"Do you mean he kills 'em and makes it look like suicide?"

"Not so. If he is forced to kill he makes it look like accidental death. Almost always he succeeds in making them kill themselves, and there is no possible doubt about its being suicide. All sorts of ways—clever ways. Bullets. Hanging. Poison."

"Ye-e-e-s. Maybe. But that ain't suicide if they don't know what they're doing."

"But they do know. Mr. Quorn, they do know. That is his ingenuity—his creed—his purpose—his religion. It is not enough for him to kill their bodies; he must doom their spirits also."

"That guy seems to be fixing up a lonely future for himself. Even in hell there won't be many o' his kind. Well, it's pretty near time for my act. But what's the point of all this? You aren't skeered, are you, that he'll suicide me?"

"There is no knowing," Bamjee answered. "Don't say I didn't warn you. The temple Brahmins are your enemies. Maraj is in town; and Maraj is more cunning than chemicals that make no noise but work in the dark and change something into something else."

"Mind yourself," said Quorn. "I'm going to unhitch this critter."

THE crowd divided down the midst, making a lane

along which Asoka moved with ponderous dignity until he

reached the circular roped arena in the center of the

compound.

Asoka's mood seemed perfect. He knew that the crowd wondered at him, and he enjoyed it. He quickened his pace as he neared the arena, as if he liked doing his tricks, and he commenced the first one before Quorn ordered it, limping around the arena on three legs.

According to Quorn, he was the only elephant in the world who could turn a somersault; he did it three times. Then he walked on his hind legs; he walked on his fore legs; he played the drum; he lay on Quorn without crushing him; he picked him up and swung him, as if his trunk were a trapeze; he sat and begged for biscuits as a dog does.

He caused roars of laughter by opening an umbrella and sauntering around the ring, holding it at the proper angle to the sun, with a two-foot dummy cigar dangling from the corner of his mouth. He was so well behaved that he ignored the oranges the children threw to him until Quorn told him he might pick them up.

And last of all—his most hair-raising trick—he pretended to get angry with Quorn and chased him until he caught him, swung him in the air as if about to hurl him to the ground, but placed him on his neck instead and started leisurely back toward his picket under the neem-tree.

"Not so bad, you sucker. If you make yourself all that popular," said Quorn, wiping the sweat from his face, "they're liable to forget some o' your peccadillos, such as smashing up the market place and what not else. Hey—steady now! Don't spoil it!"

But a naked fanatic whose type of holiness was dancing with a dozen snakes twined on his arms and neck had forced himself into the lane between the thronging crowd and blocked the way, giving a technically perfect exhibition of the dance of death. The crowd watched spellbound, making no room on either side of him.

Asoka began to gurgle. There is no truth in the tale that elephants fear mice, but some of them fear snakes, like a man in delirium tremens, Asoka hated them; they made him hysterical. Quorn shouted to the fanatic to get out of the way, but the ash-smeared, naked seeker of salvation only danced the harder, making his snakes weave themselves in writhing patterns.. He even began to dance toward Asoka.

Quorn shouted to the crowd to make the fool go somewhere else, although he knew they would rate it sacrilege to interfere with any one so holy. He even yelled for Bamjee, knowing that Bamjee had no fear of sacrilege; Bamjee might have courage enough to whip the fakir off the lot. But Bamjee had vanished.

Quorn tried to turn Asoka back to the arena, but the crowd had closed in behind and on either flank; there was no room to turn quickly. And suddenly the fanatic flung his snakes straight at Asoka's face. He might better have pulled the lanyard that fires a cannon. He stood still, waiting for results, perhaps for half a second.

It appeared to Quorn—and Bamjee afterward confirmed it—that during that half second some one shouted in a strange tongue to the fanatic, who glanced, as if toward the voice, exactly at the moment when Asoka launched his charge.

Asoka may have meant to kill him, or he may have been merely hysterical and in a five-ton hurry to get home to his snakeless, comfortable picket by the neem-tree. It made no difference. The fanatic was in the way. He became a crimson mess that writhed as his snakes had done, crushed flat where Asoka trampled him in passing.

Quorn heard mocking laughter and knew he was meant to hear it, since it was pitched above the din the crowd made, but he did not dare to look to right or left; he had one purpose now—to keep his elephant from trampling the crowd that was milling in mob hysteria.

There were only fifty yards to go, and he discovered that he could guide Asoka easily. The elephant responded to the least touch. He was not in one of his tantrums.

"All right," said Quorn, between his teeth, "that guy committed suicide and you, you're not guilty o' murder. But who's to prove it? They'll get the Maxim out and shoot you full o' holes, you sucker! Hell, no—home's no use to you—keep going! Keep on going! You for the tall timber!"

There is nothing on four legs faster than an elephant for half a mile. Bamjee was by the back gate; it was he who opened it. Asoka charged through like a gun going into action and Quorn heard Bamjee shout to him something about Maraj. But his ear only caught the one word, because behind him the compound was full of the din of the crowd and Asoka, too, was not moving his tonnage in silence..

Beyond, lay the open road, dusty and winding between ancient trees that were the fringe of a forest, and Asoka seemed to know he must run for his life; but to make sure Quorn emphasized the information with the goad, the iron ankus.

"Give her the gun now! Step on it! You great big bone-head, think up your own alibi while you run! And then tell me where to hide you! Jumping gee whiz, who can hide an elephant?"

NIGHTS are noisier than days when Narada is keeping carnival; and they are lovelier, because the colored lanterns sway amid a mystery of trees and the roofs of nearly all the ancient buildings are limned in dim fire. Shutters are closed; thieves are abroad. But doors are open; shafts of yellow light cross narrow streets; the passers-by are gaudily dressed humans at one moment, phantoms the next.

Friends and their families sit in the doors, adding din to the din. Men, women, children sleep in any corner they can find, or on the tiled floor of the market place, or in mid-street, reckless of the traffic; shadows are avoided for fear of treading on an unseen sleeper, or a drunken one who might have lost his feeling of inferiority and found his knife. There is even a certain amount of highway robbery; people wander in groups, and those who have no friends follow any group that has the kindness to endure them.

There was therefore something suspicious and worthy of comment in the way that Bamjee hurried through the city. He was alone, he avoided groups as much as possible and he kept in the shadows wherever he could. He knew Narada intimately, inside out, and yet he wandered like a lost man and selected streets that almost everybody knew were dangerous.

He passed by gambling houses, near which the strong-arm gentry lurked to rob the winners on their way home. Somebody snatched his watch-chain.

He was so out of breath and excited that he made the mistake of trying to elbow his way through a marriage procession. Sixteen sweating dancers paused from their contortions in the colored lantern light to hold him while their overseer beat him with a long stick; then they flung him into the crowd and the crowd bullied him, not knowing who he was, until he left his gray silk jacket in their hands and escaped down an alley, where he fell over a sleeping woman, who yelled to her husband—a lusty peasant, who gave chase, crying thieves and murder.

Bamjee had to stop and bribe the peasant to let him alone, nor was the peasant satisfied until reasonably sure that he had all the money in Bamjee's possession. If he had known Bamjee, and had not been a simple peasant, he might have suspected that Bamjee did not keep all his money in one pocket.

The strangest part was that Bamjee did not head toward his own three-story house in the bazaar, with its office on the ground floor and living quarters above, where his family were keeping supper for him. He appeared to dread pursuit and yet seemed equally afraid of running into some one who might recognize him.

When he saw a policeman he ducked down an alley as swiftly as when he saw a group of temple Brahmins and their attendants armed with staves to keep the crowd from defiling them with its touch. He avoided all the temples, yet seemed deadly curious to learn what the crowds around the temples were discussing; several times he took advantage of deep shadows to approach and listen. What he learned excited him and sent him dodging again through shadows.

It was toward the palace that he headed finally, constantly glancing over his shoulder, and now and then pausing in doorways to make sure he was not being followed. He did not go through the main gate, where the men on sentry duty knew him and the officer was so involved with Bamjee in intricate schemes for grafting off the public treasury that one might suppose he would have to be friendly. Friends may be as dangerous as enemies—especially that sort of friend.

When Bamjee passed the main gate he took advantage of a four-wheeled, tented wagon going the same way to screen himself from observation. Out of breath though he was, tired though he was, he displayed the agility of a youngster when he came to a part of the wall where stones were missing and the branches of a huge tree offered means of descent on the other side.

However, his wits were tired, too. He forgot that that tree stood in an inclosure in which a sacred white bull cultivated boredom and a loathing of all bipeds. The bull was hardly larger than a big dog, but at least as active and not at all in love with being awakened in the night.

Bamjee fell almost on top of him. There was sudden and tremendous noise. Bamjee went out over the six-foot wall of the inclosure faster than a monkey, thanking a whole pantheon of gods that he did not believe in, because his pants and not his thigh muscles had caught on the bull's horn.

One pants-leg was still intact; by holding onto the other as he ran, he could make himself believe he looked presentable. It is what we believe that matters—until there is collision with a stronger disbelief.

HE fled like a ghost through the trees in the

palace garden, skirting the portico and the terraces until

he reached the servants' quarters and the back door used by

underlings. There was nothing normal about that; Bamjee, as

official purchasing agent with a position to keep up before

the world, had never felt he could afford to be admitted

to the palace by any except the front door. Suspicion

reared itself against him, blackmail springing from it, as

naturally as Minerva from the brow of Jove.

He was greeted by a hamal, which is a kind of go-between servant who normally does all the butler's work, and gets and deserves all the blame for whatever goes wrong. The hamal refused to recognize him at first, although he did concede the advisability of standing in the dark to talk. Blackmail abhors witnesses as absolutely as nature abhors a vacuum. "I am Bamjee!"

"By Siva's necklace, that is an easy thing to say and any one might say it in the dark. But Bamjee sahib has the name of being a liberal gentleman."

Bamjee had to feel under his shirt for money, and it was so dark in that corner behind the butler's pantry wall that he could not see the denomination of the bills he drew forth. He had to guess.

He guessed wrong. It was too much money for a hamal.

"Son of an immoral mother, hide that in your belly-band and take my message."

But the hamal turned toward the light. He saw a fifty-rupee note. He hid it with the swiftness of a roadside conjurer.

"But, Bamjee, sahib, my day's work is over. I am not even allowed to enter the kitchen again until to-morrow morning. Will to-morrow not do?"

"Do you know what now means? Ingrate! If the nowness of the now does not make you act swifter than dynamite I will see to it that you have no job to-morrow morning.. You are out—a screech-owl screaming in a wilderness of debt with a wife on her way to another man's arms and your children following the chickens through the streets to pick up food, unless you take my message now! Now, do you understand me? Go before I beat the teeth out of your head!"

"But, sahib—"

"Very well, I will make a great noise and summon the butler. I will tell him you offered to sell me some of the palace silverware for one-fifth of its weight in rupees."

"Sahib, the butler would demand at least two hundred rupees to take such a message at this hour. Whereas I, if he should catch me before I whisper to one of the maids, could bribe him with only fifty. So give me fifty more and I will do it. Thus I shall have only forty for myself, because I must give the maid ten—at least ten."

Bamjee paid him in the dark and was so impatient and excited that he never knew that he had given the man an extra hundred by mistake. He sat down in the dark and waited—endlessly it seemed to him, while the hamal sent the message up in relays to the roof, each relay offering excuses and objections until the last possible cent had been squeezed from the man below and the hamal's hundred and fifty dwindled to a hundred.

It appeared there was a party on the roof; it was no time to interrupt a royal lady, even though she was breaking every canon of tradition by entertaining men in her palace, and of the two men one an Englishman. Even Bamjee, the contemptuous skeptic, shuddered at the idea of an Englishman drinking champagne with the Ranee on the palace roof. It made him repeat to himself the dark names certain temple priests were calling her.

THE message reached its goal at last and there was

no more lost time. It might be difficult to reach the Ranee

from below, but when she commanded from above it was as if

she pressed an electric button and things happened. Men

leaped to obey.

A very important palace personage was sent to guide Bamjee up a labyrinth of stairs and passages; and because his pants were torn he was supplied with an Indian costume of crimson silk before he was ushered into the presence, amid a fairyland of colored lights, in a garden that bloomed in tiled flower beds, where baskets that seemed to have been fastened to the stars swayed gently in the night air, drenching it with the scent of musk, and a splashing fountain filled the air with music.

There was other music also; women behind a marble lattice-work were playing flutes; a man was singing the love-song of the bride of Krishna. Bamjee, stepping out of darkness with the colored lamp-light on his crimson costume looked no longer like a babu; he resembled an ambassador from Araby, bringing news of caravans loaded with spices and slaves and jewels.

He even forgot his nervousness to some extent, because Marmaduke Brazenose Blake was seated smoking in a lounge chair, dressed in a black dinner jacket, with his monocle fixed in his eye and an air of bachelor enjoyment like an aura all around him. It was such a scandal that Blake should be there that Bamjee grew for the moment almost superior to his surroundings—almost, but not quite.

Facing Blake sat Rana Raj Singh, prince of a line of Rajput blood so purple that its sources—so men say—are traceable to when the gods made merry on the earth with men and were a trifle more than merry with the women. Tall, black-bearded, handsome—graceful with the litheness of a swordsman who can hunt the gray boar with a sword on horseback, who has lived clean and neither drinks nor guzzles.

His presence was, if possible, the more scandalous. Blake, it might be presumed, might hardly understand the horror of the Indian aristocracy if it should learn that he was sitting vis-à-vis the Ranee on her sacred roof—and she unveiled. But they would know that Rana Raj Singh understood the significance, even as Bamjee did. It meant that the pillars of Indian aristocracy were falling—or else changing; and to some people change is as bad as decay. Rana Raj Singh was a cataclysm, not a scandal; compared to his presence there, Sodom and Gomorrah were a minor incident.

But the Ranee, even at nineteen, which is a revolutionary age, had not thrown all tradition to the winds. She had kept its substance, while throwing away the shell. She had ten of her ladies with her, five on either hand—surely sufficient witnesses to prove to any jury that she had not sinned as deeply as Mother Eve, who set the first unveiled example.

Nor had she forgotten strategy. Her ladies were as marvelously dressed as flowers in the early morning dew, but none of them was younger than herself and some were older: none was as good-looking. Her dress was the plainest and made in Paris by a magician who knew how youth should look beneath a hot night sky amid the smell of musk and the rustle of palm leaves.

Although Bamjee knew her well, and had seen her often, in that setting she made his sharp little eyes almost snap from his head, and took away all his remaining breath.

"What can it be, Bamjee, so important that you must intrude at this hour?" she asked pleasantly. But underneath the velvet voice there was a hint of iron. It might not fare well with Bamjee if his errand lacked justification. "Speak," she said. "The company will excuse you."

"Sister of the Starlight, this is terrible and secret news I bring," said Bamjee. "Is it wise to spread the scroll of evil before strangers' eyes?" he quoted.

"Who, then, is the stranger?" she asked him. "Speak, fool!"

"But, Daughter of the Dew, there are the servants—"

"Oh, very well." She clapped her hands until the chief attendant stood before her. "You and all the servants have my leave to go until I send for you again. See that none waits in hiding behind the flower pots—and now," she said, staring at Bamjee. "What is it?"

"THE elephant Asoka slew a man."

"I know that. It is a great pity, even though the man who was killed seems to have been almost as disgusting a reptile as the snakes that crawled like vermin on him. I am sorry to say that Asoka will have to be shot, unless—perhaps you have come to tell me some way out of it?"

"Playmate of the gods, they are saying that the man who was slain was Maraj! He was crushed out of recognition. Who shall say it was not he?"

"Who should want to say it was not Maraj? If such good news is true your intrusion is justified. We may forgive Asoka."

"Lioness of Heaven, it was not Maraj! Maraj himself has spread that rumor and the temple Brahmins are confirming it. Why? Why not? Whoever thinks Maraj is dead is less on guard against him. Nevertheless, although the temple Brahmins are helping to spread that rumor, to you they will make no such pretense. They will send to you to-morrow. They will say the slain man was a holy one and they will try to force you to order the troops to shoot Asoka. Why? Because that would cause Quorn to leave Narada and return to the United States, thus depriving you of your Gunga sahib, who has been so helpful in breaking the Brahmins' tyranny. This they will do to-morrow, nevertheless knowing that it was Maraj who slew that fakir with the snakes!"

"Maraj who slew him? What then had Asoka to do with it?"

"The man was suicided!"

"Hell's bells!" muttered Blake, and Rana Raj Singh scratched the chin beneath his beard.

"How do you know this, Bamjee?"

"Beloved by the Rishis, if I should dare to tell you—"

"If you should dare not to, Bamjee—do you wish to resign from your post as purchasing agent? Do you wish to leave Narada? Do you wish the auditor to publish the report that he has shown me privately?"

"Oh. my God!" said Bamjee. "This babu is on the horns of a dilemma! How do I know it was Maraj who suicided that abominably holy person? I know it as well as I know I also shall be suicided if it ever leaks out who told! That very holy person was the man whose poisonous serpents were employed to slay Ali Gul the Moslem money-lender, whom all hated. Was he slain? No. He was suicided. Why not? Had he not a mortgage on a property that the Brahmins said was their property? Was the mortgage found after his death? No. He also had a mortgage on a property of mine. Was that found? No. Were any of his papers found? No.. How was he suicided? He was given his choice between taking a living cobra into his bed that night or being accidentally caused to break a vial of carbolic acid with his face. And how do I know that? His widow told me. How did she know? She was in the secret cabinet where Ah Gul used to hide witnesses to what were supposed to be secret conversations."

"This story sounds fishy to me," remarked Blake and Rana Raj Singh nodded, but his nod was neutral. He was possibly confirming his own estimate of Blake's neutrality. Blake turned to the Ranee. "Of course, your highness, as your guest I cannot take official cognizance of any of this. But may I ask to be excused from hearing more. It might be awkward."

The Ranee smiled as sweetly as if she were Machiavelli himself in woman's raiment. Blake, as the official representative of the British-Indian government, with authority to advise and keep watch and report, was no bugbear to her—not though on the strength of his reports the British-Indian government might send commissioners to rule in her name and reduce her to the status of a puppet-queen. He was a sportsman and a gentleman—insuperable handicaps in dealing with a woman who understood both qualities and had the wit to play the game according to his rules, but with her own rules added.

"I might need you," she said, gazing at him. "For the present let us call this a private conversation. Confidential—under the seal of hospitality. Then, if it gets too serious, I could consent to your breaking the seal of confidence, without having to tell you it all from the beginning."

BLAKE should have taken his leave. But he loved

her too well, in a fatherly, middle-aged bachelor fashion.

She was too amusing to be left, and also too likely to do

something recklessly behind his back that might cost him

months of letter-writing to his government to explain away.

He was lazy and hated writing letters. His purpose was to

keep her on the throne in spite of her own recklessness,

and in spite of all her enemies, if he could manage it by

any gentlemanly means. He repeatedly risked his own good

standing with his government to cover the strategic errors

due to her inexperience.

"Highly irregular," he said, frowning. "However, I will stay if you wish."

And then came Quorn—at first a message from him, saying he was downstairs in the front hall threatening mayhem to the palace servants who kept him waiting there.

"Daughter of the Dawn, he uses strange oaths, yet he is not drunk."

Then Quorn himself, treading the heels of the servant sent to bring him—Quorn in his turban, with a ready-made blue serge jacket on over his Indian costume, and in his right hand the ankus of office, the iron hook with which he normally controlled Asoka's ponderous movements. Servants standing near him shuddered at it. The Ranee dismissed the servants.

"Miss," he began, then hesitated, being vague on the subject of etiquette. Besides, Blake's presence bothered him. He liked Blake, but he was too much a restraining influence on the Ranee to be suffered without some resentment. Also he knew that Blake disliked that form of address to a reigning Ranee.

The Ranee nodded. She liked Quorn to call her miss—it sounded so enormously more honest than titles such as Bamjee and her servants used. She valued Quorn more highly than a dozen Blakes, and at that without robbing Blake of credit. It is only fools and knaves who undervalue one man because they recognize the different merits of another. She was neither a fool nor more cf a knave than any statesman has to be.

"Yes, Mr. Quorn?"

"You heard what Asoka done, miss? 'Tweren't his fault. He was behaving gentle as a lamb. That there holy feller went and beaned him with a raft o' snakes that would have made a temple statue throw a fit. And mind you, it was done a-purpose. Some one laughed. Maybe you don't know the kind o' laugh I mean! There's Brahmins at the bottom of it, them there temple Brahmins. I've been home to clean up, miss, and my Eurasian servant Moses had an earful for me. They've been bragging to him—told him now you'll have to order out the Maxim squad to shoot Asoka first thing to-morrow morning."

"Have you any suggestions to offer, Mr. Quorn?"

"No, miss—excepting, if you will pardon me, miss, and no insolence intended—I'd as soon they'd shoot me first. I couldn't tell you, miss, how much that critter means to me. And he weren't guilty. No, miss, he didn't even throw a tantrum. He was same as me or you if we'd had poison snakes thrown at us.

"And the devil who did it had time to get out o' the road, too. He was one o' these here fanatics. He chose that way o' dying. Miss, it wouldn't be fair to shoot Asoka—not for that."

"Where is Asoka now?" she asked him.

"Miss, I've got him hid."

Because she was young and not yet spoiled by life, the Ranee did not sigh relief, she smiled it. It was Blake who sighed. Rana Raj Singh grunted.

"I have heard of hiding needles in a haystack," said the Ranee. "Are you sure that no one knows where you have hidden him?"

"No, miss, I ain't sure of nothing. But I'm reasonably sure."

"How will you feed him? Can't they follow you when you come and

"That's just exactly it, miss. I want leave of absence, please, and some money."

"My steward shall give you money. Yes, you may have leave of absence."

"There was something else, miss."

Quorn glanced sidewise at Bamjee, whom he trusted at any time about half as far as he could see him.

But the Ranee had a trick of trusting untrustworthy people in the same way that some people skate on thin ice, going where others don't dare to go. It pays if you can do it; and if you can't you only drown, so it doesn't matter.

"Listen to this, Bamjee," she said. "Listen well. It would do your credit with me no harm if you should happen this once—this first time—to be loyal and secretive."

BAMJEE smirked a protest of his loyalty. He bowed

acknowledgment of trust. He opened his eyes and snapped

his mouth shut, symbolizing secrecy. He threw a chest.

Manfully he held his hands behind him. He deceived the

Ranee as thoroughly as a child deceives its nurse at

hide-and-seek.

"I will order the treasurer to hold up for the present all the money due you for commissions," continued the Ranee. "And now, Mr. Quorn, what is it?"

"This, miss. Them there Brahmins. I figure you're number three on the Brahmins' list. They mean to get Asoka first, me next, and then you. If they can force you to order Asoka shot, that gets rid o' me automatic. I'd go home. You could get along, o' course, without me, easy.

"But you can't afford to have them Brahmins bragging they put one over on you. So I'm here to say I'll stand by you and take all chances o' black magic, and snakes, and this here murderer Maraj, if you'll okay me."

"What do you mean—okay you?"

"War, miss! War to a finish! Back me until I get this guy Maraj and prove him on the Brahmins! Flynn ain't my name. I'm no Pinkerton or Burns. I'm plain yours truly with his goat got and his dander good and riz. There won't be no widow or orphans if they get my number. I wrote my will the other day. I named Asoka; he's to have my bit of insurance money. If Asoka dies first, then it goes in a lump to the feller that gets the crook who killed him. Only, if Asoka should be executed, then the money goes where it can do the most harm; I've named a gang of reformers in the States who'll make more trouble for the Brahmins with my bit o' money than Asoka himself could if he tore loose at one o' their celebrations. So that's that, miss. Are you in on it?"

She nodded. Blake looked nervous; he knew the danger of what Quorn proposed.

Rana Raj Singh, thrusting his jaw-forward, stroked it, running his fingers through his beard.

"My God!" said Bamjee. "You bequeath your money to an elephant?"

"Mr. Quorn," said the Ranee, "I appoint you my special agent to investigate Maraj and his association with the Brahmins. You may kill him wherever you find him. You may give whatever orders you please. You may employ the troops, the police, my palace servants, Bamjee—any one. I will put that in writing and sign and seal it. If any one refuses to obey you you may have him put in prison. If you catch Maraj or kill him, and if you prove he was in any way associated with the Brahmins, I will raise you to the rank of Sirdar and I will use what influence I have with Mr. Blake to get the British government to confirm the title. Does that satisfy you?"

"Yes, miss."

"What else? You seem to have something else on your mind?"

Quorn looked straight at Rana Raj Singh—very straight indeed, but he could see Blake's face at the same time, and he knew better than vaguely what was going on in Blake's mind.

As an independent prince without a fortune, but with a tremendous reputation, who was modern enough to woo the Ranee in the modern way, Rana Raj Singh would be a deadly dangerous spark to plunge into the magazine of local politics. His interference might provide excuse for riots. On the other hand, he had a handful of Rajput followers, than whom there could not possibly be better and braver or more willing experts at hunting a murderer down.

Rana Raj Singh slowly rose out of his chair. He nodded at Quorn. He smiled at the Ranee, showing wonderful white teeth. He smiled at Blake, Then he nodded at Quorn again.

"You will need help," he said. "I will provide it. You may order me, too."

"Oh, my God!" said Bamjee.

That was reasonable comment. When a prince, whose pedigree is older than the proudest European king's, submits himself to the disposal of a man of an alien race, whose business is training elephants and whose pedigree dates from just before the time when births in Philadelphia were legally recorded, it is thinkable, even by Bamjee, that the two of them are first-class men.

Blake actually dropped his monocle, and had to screw it in again. The Ranee's ladies fluttered with astonishment.

The Ranee looked with wondering eyes from Quorn to Rana Raj Singh and then back again. Quorn stiffened himself, caught Rana Raj Singh's eye and answered him with four words:

"Sir to you, sir."

SAY this for England: a Residency is a place where any one is safe, no matter who he is nor why he has taken refuge. Since '57. when they held the Lucknow Residency against as long odds as were ever laid against a garrison, it has become a part of India's superstition that a Residency is inviolable.

The upper classes recognize it as an embassy or legation, with all that implies; the lower classes don't reason about it, but even the criminals respect it as a sanctuary, where life at any rate is safe until the law determines otherwise. No violence in Residency grounds.

"Quorn," said Blake as they left the palace, "I'm going to take you up behind me on my horse and ride you to the Residency. I've a notion you may have been followed here, and they may be on the lookout for you. I will talk with you—unofficially—after we reach my quarters."

Blake's whaler mare behaved abominably, not being used to the weight of two men, and Quorn was no horseman. They clattered on the stones beneath the guardhouse gate; they plunged and lunged along the street outside, shying at every shadow; and they made so much noise that all Narada might have heard and seen and recognized them.

However, nothing happened, and Blake's servant, running alongside, reported that, as far as he knew, they were not being followed—until they left the zone of partially lighted streets and plunged into the pitch-dark lane between high walls that led toward the Residency compound. There the servant fell and smashed his lantern.

Blake reined in, and Quorn jumped down to help the man. He could hear him sobbing. He groped for him in total darkness, finding him—feeling him just as the sobbing ceased. He could feel two men. They were both dead.

"Got a match, sir?"

Blake passed him a box of matches. Blake's Moslem servant, Abdul, lay dead of a knife wound. He was lying prone on another man, who lay face upward and who seemed to have been dead for quite a little while before Abdul tripped and fell belly downward on the long, razor-edged knife whose hilt was in the dead man's hand.

"But there's another, smaller blade below the hilt, sir," Quorn reported, striking match after match. "It's one o' them there weapons that can be used as sword and dagger. The shorter blade is stuck into the dead guy's stomach; that's what held the knife upright.

"Yes, sir, Abdul is stone dead. The long blade passed clean through him—there's three inches of it sticking out of his back. If you should ask me, he couldn't fall that hard. I'd say not. There's something tricky about the way the lamp was smashed—as if it was knocked out of his hand on purpose. Would you care to look, sir, if I hold the horse? It looks to me as if some one jumped on Abdul's back and forced him down on the knife."

"Are you positive he's dead?" asked Blake.

"As dead as mutton."

"Well, the thing to do is to get his body to the Residency. Which shall it be? Will you run on and bring back any of my servants you can find? Or will you wait here while I gallop and get them?"

"Go ahead, sir. That's the quickest. Do you pack a gat, sir?"

"Do I do what?"

"Carry an automatic?"

"No, confound it. Here, are you sure both men are dead? Get up behind me then and we'll both go. That's safer."

"No, sir, I'll be all right. I'll stay here. You hurry."

It was Blake's off night. No human being ever lived who did not make a murderous mistake at one time or another. Blake rammed in his spurs and thundered down the dark lane like a whole troop of cavalry. He made enough noise to drown the shouts of ten men, and his own shouts, to his servants, as he neared the Residency, were enough to deafen them to any noises Quorn made—not that Quorn made any.

HE hardly knew what struck him. He felt a stinging

blow from behind and smelled the musty stench of a burlap

gag that was thrust into his mouth and wrapped around his

head.

He struck out blindly with his fists, but hardly felt his wrists seized and pinioned, hardly felt his ankles being tied before he became unconscious from the blow—or perhaps from some drug with which the gag was soaked; it tasted beastly. He had seen nobody; he had heard no sound; he could not even swear that a cry had escaped his own lips.

He recovered consciousness within a dark room and lay listening to voices that, for a long time, seemed to be inside his own head. It seemed to him he was home in Philadelphia. His taxicab had been in some sort of smash-up—his first. He felt ashamed, and afraid for his license. After awhile he shook off that feeling, but the voices seemed to come from another world—inhuman, without emotion, hollow.

At last, though, he was able to recognize a few words in the local native tongue, but it was a long time before he could make any sense of what was being said. There was an argument—hot on one side, ice cold on the other. One man was urging action, to which the other appeared insolently indifferent.

"If you don't kill him now—"

"I know my business."

"He is probably listening!"

"Let him."

"Can't you understand that the Englishman, Blake, will raise such a hue and cry that—"

"I have understanding. I am not in need of advice from you."

"By Jinendra's nose, I am not giving you advice! I order you!"

"Order somebody who will obey you—some priest, for instance. I am no temple rat."

"Too much success has made you insolent."

"No. I was always insolent."

"Suppose we should turn against you?"

"That is not hard to imagine. You are sure to do it sooner or later. I am not afraid of you. You know why Cease talking. You annoy me. It is not safe to annoy me."

Some one took a cover off a lamp. The light hurt Quorn's eyes; he shut them for a moment. When he opened them again a man was squatting beside him, gazing at him. He was a man with a big head, crowned with a shock of shaggy hair that seemed to have been bleached to the color of new manila rope.

He had dark eyebrows and a shaggy, dark beard and mustache that half hid and yet exaggerated the coarseness of a big mouth, around whose corners a sort of humor lurked. His nose was coarse and honeycombed with pock-marks. His big, full, deep-set eyes had humor of a sort too, but it was cruel humor; they would have been splendid eyes if they had had more color, but they were so light—gray, blue, green perhaps—as to look hardly human.

"Why do you not go to the United States?"

It was the bored voice that had pleaded insolence. Quorn lay still, trying whether he could move his wrists and ankles, wondering whether he could break the man's neck if he had his arms free. He felt an impulse to kill.

Quorn was a man who had almost never raised his hand in violence; certainly he had never contemplated doing murder; he would have been willing to bet all his money, at any time, that he never would commit murder, and would never wish to do it. Yet he felt now he would almost rather kill that man who gazed at him than go on living. There was nothing to argue about, he just wanted to kill him.

"Do you wish ever to see the United States again?" the man asked him, in the same cold, incurious voice.

Quorn did not trust himself even to try to speak. He was working hard to regain possession of his senses, which recognized, in the man who was talking to him, something vaguely suggestive of his own peculiar influence over animals.

Nevertheless, he had never pretended to understand that influence; and this man's was not quite the same, it seemed reversed, although to save his life Quorn could not have explained the difference. Black magic was the thought that came into his mind. His head felt woozy, and he knew that was only partly due to the blow, only partly due to the drug he still tasted; there was still something else that he felt he could fight and overcome.

"Understand me," said the man, and he spoke English with only a trace of accent, "you are physically at my mercy—absolutely. I can kill you slowly or quickly, however I please, in my own time, in my own way, for my own pleasure. Sit up. I will show you something else."

HE seized Quorn's shoulders and raised him until

he sat with his back propped in the corner of a wall. His

strength appeared to be prodigious; it produced in its

victim a sense of helplessness that had nothing to do

with the cords around wrists and ankles. It was like the

strength of machinery.

"There is a fool here," he said, "who has wearied me."

Quorn discovered it was painful to turn his head; however, he managed it, and decided he had not been badly hurt. He was in a small square room with whitewashed walls. The only furniture was heaps of gunnysacks, that looked rat eaten, and a small glass lamp on an upturned packing case.

Another man sat on a heap of sacks, whom Quorn recognized at the first glance as the individual used by the temple Brahmins as go-between, whenever they had business with persons with whom their caste forbade them to associate—a man in a long yellow robe with a variation from the Brahmin caste mark on his forehead—a sort of bastard Brahmin, a metaphysical eunuch, authorized to touch defilement in the name of holiness without infecting his masters.

"You shall watch him die."

As if he had been shot out of a catapult the other man made headlong for the door. But the door was locked.

"You would escape from Maraj? In what way are you more clever than all those others? Come here."

His panic-stricken effort having failed, the man seemed paralyzed by fear. He turned ashen gray, trembled, unable to speak. The man who had called himself Maraj reached out with his right hand, seized him by the ankle, twisted it, drew him forward, changed his hold to the shoulder and hurled him back on the heap of sacking—all with one hand and without much noticeable effort.

"I will not kill him. He shall kill himself."

At those words the man found speech at last. He jabbered, stuttered, threatened, pleaded—until his voice died to a meaningless mumble and his jaw fell.

Then Quorn spoke for the first time: "Out with the light, you idiot!" The advice came too late. The Brahmin did make a move toward the lamp, but the other man seized his ankle and twisted it again until he screamed and struggled like a landed fish. Maraj then put the lamp up on a beam; he had to stand on the box to do it.

"It is time to die now," said Maraj. "Which way do you prefer? Painless, of course. They all seek painless ways, as if that made any difference! Die! Do you hear me? Kill yourself!"

He turned to Quorn: "The poor fool threatened me. He had the impudence to order me. He said he would betray me unless I slew you out of hand. He could do it, too; he could have betrayed me easily if I had let him. But he hasn't much intelligence. Let us see which way he chooses."

He sat down close to Quorn and waited, watching his victim, who seemed several times as if going to speak—and as if then the uselessness of speech occurred to him. He even seemed to try to summon dignity, but found none.

"What will you do?" Maraj asked. "You have no knife—no rope. How will you kill yourself?"

Quorn spoke again, surprised by the impersonal aloofness of his own voice, that sounded as if it belonged to some one else.

"Why not have a crack at killing him, you idiot!" he heard himself say to the terrified prisoner.. "Til help you if you'll loose me some way."'

Maraj chuckled. "Why not?" he suggested. "Would that not be suicide? Try killing me!"

The man found speech again. Quorn's voice seemed to have stirred lees of manhood in him. He spoke in the native tongue cold-calmly, every word a concentrated curse.

"You offspring of all the dogs that ever lay in filth! You soul of stinks! You carcass of—"

HE rushed him suddenly—and died that instant.

He who had called himself Maraj stepped sidewise with

the skill of a toreador in the arena. No eye could have

followed the speed of the silken handkerchief that licked

across the man's neck and killed him infinitely more neatly

than a hangman's rope.

It left no mark on him. It severed him from life, and was out of sight again before the knees could yield under his weight and let him begin falling to the floor; and yet he fell as if there never had been life in him nor any bones to keep him straight.

"That is the art of Thuggee, so-called," said Maraj. "Isn't it brilliant? In a world where so many forms of death are messy, what do you candidly think of a so-called government that tries to stamp out and abolish such a mystery as that? Mind you, it is a mystery. It is more than an art.

"You couldn't learn it—not in fifty years—not even though I should be fool enough to try to teach you."

He rolled the body over with his foot, then sat by Quorn again. For a moment or two he paused as if turning over matters of importance in his mind. Then:

"Don't you think they ought to make me public executioner? It would make me so happy. It would save them so much trouble. Often I make a victim really kill himself, but that fool's fear was of the sort that is not easy to control. He was not sentimental. You are. Where have you hidden your elephant?"

"He ain't mine," Quorn answered.

"Liar—or else imbecile! You have no bill of sale for him; therefore he is not yours, eh? Show me a bill of sale then for the death you will presently die! Will it not be your death? Ownership! Where is the elephant?"

"He belongs to the Ranee. Ask her."

"You mistake me, I think, for a worse fool than she is. Your Ranee's hours are numbered. I said hours, I should almost have said minutes. These pretty ones—young ones—they taste sweeter on the teeth of death than carrion like that thing." He kicked at the corpse on the floor, "Does she love life? Will she cling to it? Ah, then what a sacrifice to death! Mn-n-n—what an offering! You love her, don't you? And that elephant loves you? Ah! You shall kill her. Then you shall see me kill the elephant. Then I will kill you. Perfect! Look at me."

He peered into Quorn's eyes, leaning over him. If he was human he hardly seemed so. Mania, as if it were a monstrous spirit from another plane of consciousness, had entire possession of him—a monster to whom death was life and cruelty was beauty.

Not for nothing had Quorn handled elephants in all their moods; he recognized the likeness of the thing that seized Asoka now and then. Only this was more developed—had more intelligence. He had thought of it, when Asoka threw his tantrums, as the spirit of one of nature's cataclysms, weary of blind energy and seeking a sensual outlet. But this man seemed to have the spirit of all evil in him.

"Death is a devourer—hungry. One must feed death daily, if he wants to live. Keep death fed full—and live forever! Hah! Feed life—and die forever! But you are too silly to understand that. I understand it, that is the point. You shall obey me!"

Craftily Bamjee wrote his name in

pencil of the toe of Siva's image.

QUORN lay still. He was thinking elephant. How did he manage Asoka when the fits of frenzy seized him? Let him run—offer him no opposition—hang on and wait and pretend to be one with him, seeking the same goal with the same wrath. Pretend to encourage him. Get him to use his strength against some obstacle that did not matter. Get him to exhaust himself, and at the first chance get him to believe he had done all his havoc by request. It had worked all right; the tantrums were fewer nowadays. Something of the same sort might work now—maybe—a bare chance—worth trying.

"Hell!" said Quorn. "What's all the yawp about? Do you kid yourself you're tough because you kill a few poor suckers? Yah! You don't know what tough is! You should see 'em where I come from."

"You mistake me," said Maraj. "I have been where you come from. Toughness has nothing to do with it. The tough ones die the easiest. They love life and they dread death, though they think they don't. They dread passion; therefore they are its slaves. I love passion; therefore it is my slave, even as a woman who is properly loved is the slave of a man."

"Aw, hell! That's talk. I've heard 'em on a soapbox handing out a better line o' yawp than that—bolshevists and such like. Show me. Talk don't mean nothing. I can't teach a guy to drive an automobile by singing songs to him. I got to show him. Show me. I won't believe a word of it until you show me."

All the East asserts that there is no such thing as luck, yet Quorn had stumbled on something that the men of science labored for a century to find—and doubted then. To save his soul he could not have analyzed it or have put it into plain words. What he knew, by the change in the maniac's eyes, was that he had touched off something that might presently give him the upper hand. He had gained time. He had flattered cunning. Cunning proposed to magnify itself before it had its climax.

"Why not show you? Knowledge increases suffering. Suffering is cruel. Cruelty is the delicious essence of alt nature. It is essence that I seek. I find it daily. Do you understand me? Essence."

"Hell," Quorn answered, "any fool could understand that. Essence? Huh!"

"You are ignorant, but I will teach you. Ignorant men don't suffer much, not even in this world, under torture—although I know tortures that are exquisite, and I will show you several. Suffering increases as the square of knowledge. Do you know what that means? The suffering of this world is as nothing to the infinite agony provided in the next. Those who suffer genuinely here take with them an increased ability to suffer. They add to the hell—to the hell—to the hell! Do you understand me? Spiritual, mental, infinite, eternal hell! Ah-h-h! So I shall show you. I will teach you. You shall not go forth in ignorance. You shall be a delicious morsel for the spiritual fiends of torment. What does this life matter when you have eternity in which to revel in the blistering, nervous dissonance of death?"

"It don't matter a damn—not a damn," Quorn answered. "That's an easy one."

"Where is your elephant?"

"I can find him for you any time. Say, all you've said is talk so far—lower grade stuff. You've got me interested, but you haven't proved a thing. I saw you kill that sucker, but, hell—that weren't much; I could have killed him myself with half a brick. You show me something. A genuine magic. I'll name the stunt—you do it. If you win, I join your gang. How'd that be?"

"You will be my disciple? You will yield your soul to me? You will try to learn what I shall teach? Hee-ee! That would be amusing. You will go mad, but never mind. What do you wish me to do?"

"I'll set you an easy test. Put one over on them temple Brahmins. Put it over on 'em good, mind. Trick 'em—trap 'em—show 'em up—bring shame on 'em—reduce 'em to a common joke. Then set yourself in place of 'em—me under you. I'm game if you are. The folks say I'm Gunga sahib come to life; that ought to make it easy if you have imagination. Maybe you haven't—you haven't showed me any yet. How about it?"

THERE was a long pause. Maniac imagination thrilled

itself with ecstasies of vision—Brahminism going the

way of all things mortal, only in an agony more awful than

any sane man could invent. Watching the maniac eeyes, Quorn

played his trump.

"'Fore I'd reckon you worth learning from, I'd have to see you out from under them temple Brahmins' influence. Hell, they've been giving you orders. They've been claiming they protect you. Yah! I'm not the thousandth o' what you are, yet I wouldn't let that gang claim they was protecting me. I'd show 'em different. You show 'em where they get off, and I'll join you, elephant and all."'

Maraj looked keenly at him. Quorn's face was as innocent as any actor's. The blind spot that is in the brain of every maniac, however supernormal his intelligence may be, permitted vanity to smother cunning.

"You'd better let me go and get my elephant," said Quorn. "Come with me if you like," he added, noticing a sudden constriction of the irises of the madman's eyes. "Then you make all the plans, remember. This ain't my problem, it's yours. I'm yours if you work it out right. Anything you say, I'll do, barring that I don't have to kill nobody until the temple Brahmins quit, and fire a lee gun, and haul their flag down. Get me? After that I'll kill as many as you say."

"Tell me," Maraj leaned over him again. "Do your wrists hurt? Does the cord cut your ankles?"

If the East is right and there is no such thing as luck, perhaps luck is a form of genius. Again Quorn stumbled on the key to freedom, though he paid a high price.

"Yeah, it hurts fine. I like it," he answered.

"Hee-ee! You do? You like it? Try this. Is it exquisite now?"

He knew where to touch the nerves that carry torture to the brain. Quorn writhed, but the lamp threw shadow on him. Maraj had rolled him over on his face. Quorn's quivering and grunting might be masochistic ecstasy.

"You will do, you will do for a pupil," said Maraj. He cut the cords; Quorn almost sobbed with the relief. "That is not a bad beginning. I can teach you. You shall learn that pain is the only pleasure. Go now. Go and find your elephant."

"Are you coming with me?" Quorn asked.

Sudden fury seized the maniac, "You witless idiot!" he shouted. "Who are you to dare to question me, your master? Do you think I need to watch a fool like you? Can you escape me? Try it! Go before I—"

He made a gesture as if to produce the handkerchief with which he could kill with such consummate art. Quorn staggered to the door, in torture from his rope-raw ankles. It was locked. His wit deserted him; he could not imagine what to do. He glanced at the glass lamp on the beam. With his ankles in that shape could he jump up from the box and smash the lamp, and take a chance in darkness? He decided he would try.

He had gathered his strength for the spring when he heard voices. Something on the outside struck the door. He heard the hinges give. He saw Maraj spring, swinging for a moment like a monkey on the beam—spring like a monkey again and break an opening, feet first, through the thatched roof. Blake burst in then—Blake and half a dozen servants. It was like a dream.

"Here you are, eh? Hurt much? Had a hard time finding you. Hello—who's dead? Well, I'll be damned—another murder, eh? Oh, look out there—catch Quorn, or he'll tumble. Lay him on that sacking."

RATS are credited with instinct that enables them to leave a ship some time before it sinks. Bamjee had perhaps evolved beyond that animal characteristic without losing the desire to practice it. He was as fearful and as fearless as a rat—as full of cunning and as energetic—as suspicious and as keen on testing information for himself. What he lacked in actual intuition was compensated by peculiar alertness. He was not at all afraid of venturing so near to a trap, or even into one, that a sneeze or a sigh would have snapped the spring. But he was difficult to catch. And being an incredulous, irreverent, observant rat he understood the ways of temple Brahmins—which is more than quite a number the Brahmins do, since, like the rest, of us, they are, generally speaking, lazy and accept as truth much untruth as their seniors believe it wise to tell them.

"My God!" said Bamjee to himself, when he had shed the palace finery and once more held his silken pants leg as he flitted through the palace shrubbery in quest of secret foothold on the palace wall. "My God! If she should order that cursed auditor to tell the truth about me—Krishna! Women in authority are worse than men. They are more cunning. They are willing to let themselves be cheated, so as to have you by the short hair. And they hang on—dammit! Dammit! Dammit! On the other hand, should she lose her throne, this babu's job is gone. The auditor would see to that; I should have paid that scoundrel a better percentage—maybe—maybe—but beggars on horseback ride you down. To hell with them. And if she wins this battle with the Brahmins she will probably dismiss me anyhow and try to find an honest man for my job. There aren't any. She will ruin herself learning that the honest men are too big fools to be trusted. But that won't help poor Bamjee. This babu must climb on fence, part hair in middle for balancing purposes and be ready to jump kerplunk into the arms of either side with nuisance value well established."

For a beginning he climbed the palace wall in total darkness, leaving his pants inside the palace grounds. He did not propose to go home yet, partly from fear that his movements might be traced. It might not matter if they were traced, but—

"If I should choose to qualify the truth a little, it might be awkward if some liar knew where I actually went. I can do my own lying, thank you. And it costs less."

So he found a small storekeeper who owed him money and who felt flattered by being aroused from bed by such an important personage. To him he told a long yarn about having been stripped by thieves—

"And if it were known that such bad thieves lurk in your neighborhood, where there is only your shop and a few stables, you might find yourself in bad with the police, who would come and search you—and you know what that means! So you had better say nothing about it."

He bought several yards of cotton cloth and dressed himself native style. He also bought a cotton turban, wrapping the silk one carefully around his body underneath his shirt, and into that he tucked his remaining money.

"Now perhaps I can venture homeward without being robbed," he remarked to the storekeeper; and having started homeward because he was sure the storekeeper would watch him out of sight, he made a circuit and went hurrying in the opposite direction.

His goal now was the Pul-ke-Nichi—the long, narrow thoroughfare on the far side of the city, that dipped down between two mounds, on which the temples of Siva and Kali stood, connected by an ancient bridge. He had no fear of not finding Brahmins awake.

"Two things would wake them anyhow," he told himself, "the chink of money; and the least little whisper of smelly, secret news—they love it."

HE was tired to the bone, but he solved that

problem. To the pious horror of the temple Brahmins the

Ranee had recently installed a modern hospital in that part

of town in charge of a young Sikh doctor, who was nothing

if not keen on getting cases. There was a motor cycle

ambulance, and a night bell.

Bamjee rang the bell, gave a false name and told circumstantial details of an accident. He offered to show the way to where the victim was, and the doctor decided to drive the ambulance himself; his presence on the scene, instead of the ignorant ambulance man, might save the victim's life.

So Bamjee lay in comfort in the ambulance while the doctor drove at full tilt through the city, missing the legs of sleeping men by inches, clearing the way with his horn and breaking all the rules of even reckless driving with a confidence in destiny and disregard for risk that would never occur to any one except a Sikh intent on winning laurels for himself.

And in the dark trough of the Pul-ke-Nichi, where the bridge cast pitch-black shadows and there were too many sleeping nondescripts for even a Sikh to take that chance of killing some one, Bamjee stepped out of the ambulance to find the supposititious victim—

"Compound fracture of both thigh bones, doctor, and the ribs of both sides—one arm broken also, and perhaps internal injury—a very interesting case."

That was the last the doctor saw of him. He slid into a shadow and followed it beside the ponderous wall of Siva's temple.

There he was challenged. Two men in yellow robes ran out and blocked his way. They scurrilously mocked his glib confession of sinfulness and a desire to meditate on the omnipresence of death in life and life in death. They called him a casteless miscreant, who might go and mock his lady mother on a dung hill. So Bamjee was obliged to change his method.

"Business," he whispered, "with the high priest! You are undoubtedly 'twice born,' both of you, to make you twice as stupid as you look, but you had better tell the high priest Bamjee is here. Yes, Bamjee! Yes, Bamjee—the man who caused your temple to be defiled with Johnson's Jubilee Germ Exterminator! Bamjee with a message for the high priest—sounds important, doesn't it?"

There was whispered consultation. One man took the message and the other stayed. There followed prickly silence for a space of fifteen minutes, broken into irregular intervals by the impatient honking of the Sikh doctor's horn, until the messenger returned.

Bamjee was to be admitted—not into the temple, but into the cell across the courtyard in which virtually unclean visitors were sometimes as an act of mercy, blessed through a hole in a wall of the temple basement. So he was soused with water that had been treated by incantation, hustled across the courtyard along a row of flagstones that were also immunized against the tread of ritually unclean feet, and thrust into a bare stone chamber. Bamjee shuddered as the door slammed shut behind him and he heard the bolt slide home.

"Oh, my God!" he said. "What a man won't risk to save his neck!"

On three or four walls little lamps were burning, leaving the door in shadow. In the wall that faced the door there was a round hole, showing that the masonry was ten feet thick; the hole was trumpet-shaped, its small end inward; Bamjee did not dare to examine that very closely until he had blown out two of the three lamps and adjusted the wick of the third.

"But they will hardly dare to kill me," he reflected. "Nobody knows I was not seen to enter here. Phuh—death is an unpleasant topic—let me think of something else."

HE examined the stone chamber. There was no window.

He could hear nothing except his own blood surging in

his veins. He crept close to the wall and peered very

cautiously into the trumpet-shaped hole, but could see

nothing; it appeared to be closed at the far end. However,

presently he heard a shutter slide in iron grooves at

the end of the hole in the wall. A voice spoke angrily,

complaining that the lamps were not properly lit in the

chamber. Another voice offered to send an attendant to

light them.

"No, but discover whose fault it is. Impose a heavy penance. Go now. Close the door."

"Is that the most holy and reverend twice-born confidant of gods and treasurer of wisdom who presides over all the Brahmins of this temple to be an example to men and a blessing to the world?" asked Bamjee. "Humbly then I kiss feet. Humbly I ask blessing."

Through the hole came the mumbled perfunctory formula. Then:

"Who are you and what do you want?"

"All-wise, I am Bamjee bearing bad news."

"Because, for the sake of your pocket, you defiled this temple, you are doomed for a thousand lives to be a blind worm in the belly of a dog!"

"I know it! I know it! I sinned and the sin is on my head. (Dog of a Brahmin! Humble am I! You shall pay for it!) But may I not commence to purge my sin? (Purge your own, you old tyrant!) This babu has had sudden change of heart. Some god has probably observed what wrong this babu did (You old devil, I'd like to drown you in a tub of sewage!) and stirred an impulse to do better and to make amends. Oh, Most Wise—Muddle-head—if this babu has wrought evil, you yourself will do worse evil unless you give him opportunity to make compensation for his ill deeds! Am contrite! Am able to do valuable service. Am, above all, ab-so-lutely bent on telling truth and nothing but truth. Pity me and listen!"

"You shall be heard."