RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

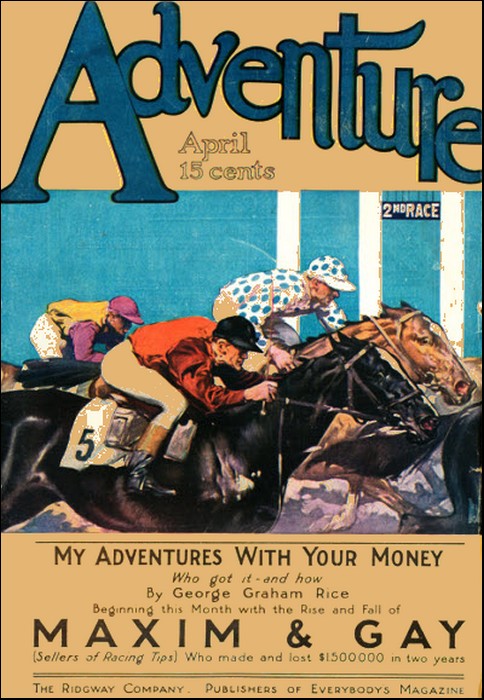

Adventure, April 1911, with "Pick-Sticking in India".

Youth's daring spirit, manhood's fire,

Firm hand and eagle eye,

Must he acquire who would aspire

To see the gray boar die.

THE above verse forms the chorus of the finest hunting-song in all the world. After dinner in India, when the day's sport is over and the decanters are going round the same way as the sun, men sing it who have met the gray boar in his majesty and seen him die fighting. Other men may join in the chorus, and think that they understand; but real understanding is denied them, for only those who have ridden straight to pig "may comprehend its mystery:"

It is the finest sport on earth, and the song, with its thundering, crashing chorus, does it honor. It is an education to listen to that song, but it is a foretaste of Valhalla to ride to pig at the break of a golden morning in India.

There are less expensive sports, though none more worth the while; and polo and fox-hunting—the only two which are even in the same street with pig-sticking—are very much dearer. The physical equipment you will require is much the same for all three, but in pig-sticking you have the added excitement of a fight to the death at the finish, with no crowd to watch you and no field of overdressed incompetents to get in the way and spoil your sport.

To see genuine pig-sticking you must go all the way to India, and there you will find it at its best in Guzerat in the North of Bombay Presidency. There are tent-clubs in Morocco and Algeria, run by enthusiastic sportsmen whom business keeps away from India; but though they hunt the wild boar religiously in the only way in which he should be hunted—on horseback with a spear, they know that the real sport is to be obtained only in the home of it—India— where the boars are bravest and the other fellows understand. So much always depends on the other fellow!

Pig-sticking consists in riding down the male of the wild boar on horseback, armed with a spear and no other weapon. A tent-club is a small club formed for the purpose, in order to reduce expenses. The tents are comfortable, sometimes even luxurious, but they can be shifted from place to place so as to be close to the scene of operations. Everywhere in India there are plenty of well-trained and willing servants, and there is no discomfort about the tent-life other than the midday heat, which, after all, is not unendurable.

The spear used in Western India, and consequently in Guzerat, is practically the same as the cavalry lance—that is to say, it is long, though it is usually a little lighter than the lance, and it is held in the same way that a lance is held—with the back of the hand turned downwards. In Central and Eastern India they use a short spear, with a weight on one end of it. It is held at the top, close under the weight, with the knuckles turned to the front; and to use it you have to lean forward a little in the saddle. You are considered eccentric if you use a short spear in Western India, and in Eastern India if you use a long one you are a jungli. Interpreted into pure United States American, jungli is a "rube."

The best practise in the use of either spear is tent-pegging; not one peg at a time taken at a canter on a quiet horse, but a succession of pegs taken one after the other at full gallop on an almost unmanageable horse. You will learn to manage your spear that way, and when your time comes to use it on a pig you will be less likely to hurt yourself, or the man next to you. The practise will also teach you to manage your horse with one hand, which is exceedingly useful.

IF you have the other qualifications laid down in the song, the two things you will need in India are money and introductions—not so very much money, but introductions of the best. Get a letter to the right man from some one who is also right, and the whole of India is open to you, from one end to the other. Go without it, and you will wish you had stayed at home.

All your minor worries you can quite comfortably leave to your servant, who will look after you like a nurse for a wage that a white man would think ridiculous. But the horses, of course, you must bargain for yourself. You will need at least six. One or two to start with will be sufficient, because in India, where distances are immense, men who are transferred from one station to another usually sell their horses, and you will have plenty of opportunities to pick up good ones up-country.

In Bombay you can usually have your pick of from five to six hundred horses and ponies of almost every breed to be found in the East, at Abdul Rahman Mirza's stables, and the prices range from about a hundred dollars, or even less for a country-bred, to five hundred or more for a first-class polo pony with a turn of speed. From first to last your six horses ought not to cost you more than the equivalent of eight or nine hundred American dollars. Many a good sportsman gets along with two mounts.

You will need a native groom for each horse, and because you are new to the country and therefore somebody to plunder, you will probably have to pay them a matter of five dollars each per month, out of which they will find themselves in food. Each man will sleep with his horse, and travel with him in the horse-box, and though they will assure you that your honor is their honor, and that the service of the heaven-born —you are the heaven-born—is the height of their ambition, you will have to watch them pretty closely if you do not want them to steal and sell your horses' food. But they are not bad grooms, and once they grasp the fact that you know what to expect from them, your horses will be well turned out.

It is hard to lay down a general rule, for horses vary as much as men, but, taking one thing with another, country-bred horses are the best for your purpose. Besides being generally cheaper, they stand the hard going better than Arabs or Walers. The kind they breed in Kathiawar are often exceptionally good, though not always up to weight. If you are a particularly heavy man your choice will be limited to Walers—the imported Australian horses. In that case choose mares, because they are more likely to be savage, though the merits of a horse that has been cast from the army for vice are not to be lightly overlooked. Other things being equal, the more vicious your mount is, the better. Arabs are often too heavy in the shoulder and too light in the leg, and they are always likely to strain themselves badly when you gallop them over hard ground. Their chief merits are their looks, but as there will not be a crowd of women to applaud you, the looks of your mount need not concern you.

If you have to blindfold your horse before he will let you get near enough to mount him, there is little likelihood of his being afraid of the pig. Some horses will even try to savage the pig with their fore-feet, and lash out at him with their hind-legs as he passes, and although that will not help you in the least to hold your spear true and steady when the boar charges, it is infinitely better than being bolted with, or having to spur a frightened beast up to the pig, with the probable mortification of seeing another man "wipe your eye" for you. Choose savage horses rather than timid ones, remember that broken knees are not always a bad sign, and above all things don't pay more than half what the dealer asks you.

THERE are practically no rules to learn. All sports in India are based on the assumption that those taking part in them are gentlemen. So, assuming that you are a gentleman, and are therefore incapable of foul riding, almost the only rule you must learn is never to ride after a sow. It is often extremely difficult to tell an old sow from a boar, especially from behind, until you get quite close. But the moment that you know it is a sow you must rein up. There is no exception to the rule.

Other rules would be difficult to frame, because the pig himself is such an unruly beast. If you made a set of rules, he would break them and you would have to follow suit. He is the most independent and fearless animal that breathes, and he doesn't give a hang for anybody or anything, tigers not excepted. The only thing which you can really depend on him to do is to put up a terrific fight and to charge as long as there is breath left in him.

And when a wild boar charges he is likely to make history. He doesn't look active in the least, but he can jump obstacles that will tax your horse's powers to the utmost, and for the first mile or so, when he has left the sounder behind and once gets going, it will puzzle the best horse you have got to come up with him. And for all this stocky build of his, he can turn on the proverbial sixpence.

His only weapons are a pair of so-called tushes—wicked little white tusks that he polishes in time of peace by grubbing up roots with them. The longest tushes measure scarcely over four inches from base to tip, yet he can disembowel a horse with them, or rip up a leather riding-boot like so much paper. If he gets you on the ground he can, and will, carve you up as neatly and thoroughly with them as a butcher could with a sharp knife. He would no more think of giving quarter than he would of asking it.

There is nothing in the jungle that does not give the right of way to a full-grown boar. A young and very inexperienced tiger might tackle him, and might inflict such wounds that the boar would bleed to death, but the tiger would not live to talk about it. He would be disemboweled and dead before the boar died.

At Poona, in the officer's mess of one of the regiments quartered there they have the skeletons of a boar and a tiger that were found locked together. It was a small boar and a large tiger, and from the position in which they were found it is easy to see what happened. Tigers almost always spring on their quarry in the same way. Their hind feet are seldom off the ground at the moment of impact, but one fore-paw tears the animal's off shoulder while he seizes its snout with the other one, trying to break its neck. He secures an additional hold by fixing his teeth in the top part of the animal's neck near where it joins the shoulder. He kills by breaking the animal's neck, and not by biting.

But the hide on the upper part of a boar's neck is rather too tough for even the average tiger's teeth, and on this occasion friend tiger did not get much of a hold and, setting aside his prodigious strength, which lies principally in his neck and shoulders, a boar's neck is too short and thick to be broken easily. Besides, a boar does not run on blindly when he is attacked, as most animals do, until he blunders into something and falls—he turns and fights; and on this occasion he must have turned and rushed in underneath the tiger and gored him to death. No doubt he died himself from loss of blood.

The skin along the upper part of a pig's neck and back and flanks is so tough as to make him almost invulnerable and, though his belly is unprotected, he is too low on the ground, and withal too active, for any other animal to gore him successfully. His rear isn't protected either, but that is offset by his natural predilection for keeping his business end—the end with the tushes and the little red eyes—toward the enemy.

Encountered on foot and alone it would be difficult to imagine a more unprofitable proposition, because he doesn't need to be asked to fight before he begins. He fights first and does the quarreling afterwards— with his tushes in the stomach of his foe. On horseback, and armed with a spear, the odds are a little in your favor—but that is all. You must take no liberties.

Of course you could take down his number with a rifle, but a man who shoots pig in India is exactly on a par with a man who shoots foxes in England. They won't hang you for doing it, because that would be much too merciful. But they will treat you like a pariah and cut you dead—which is infinitely worse than hanging.

It is a fact that a point which is usually overlooked by a beginner at the game is the point of his spear. Owing to the toughness of the boar's hide the spear-point should be as sharp as filing can make it, and it is as well to have a slight groove in the blade, near the tip. Nine-tenths of the stock of the average merchant who deals in spears have the so-called diamond points, than which in the whole world of pig-sticking there is nothing more undesirable except a timid horse. If the diamond point happens to be sharp and you do drive it into the pig, it will almost certainly get stuck between his ribs and stay there, in spite of your utmost efforts to pull it out again. In addition to spraining your wrist, you will probably incur the scorn and hatred of the man that follows you, for when the pig charges him and rises to try and gore his horse, he will receive the shaft of your spear in his teeth. You can not expect a man to be good-tempered or even civil under those circumstances.

However many members there happen to be in residence in a tent-club, they always divide up into parties of five or less for the purpose of pig-sticking. The different parties, if there are more than one, go in different directions so as not to interfere with one another's sport. There are plenty of men who will tell you that five is a crowd, and that three members to a party are plenty. However that may be, five men are the most that ever ride out together, and one of the party is always in command. He is usually the oldest and most experienced man present, and whatever he says is law—just as in fox-hunting the word of the master is law, and for the same reason—the sake of good hunting.

YOU are out, of course, to kill the pig—several pigs for that matter if you have the luck, although you take them on one at a time and all ride after the same pig—but what you ride for is "first spear." In that respect it is a race, and if you can show the first blood on the end of your spear—even if it is only a speck —the pig is yours, and when he is dead the tushes are yours, whoever kills him. That is the reason for having the little groove on the end of your spear-point; it holds the blood. In long grass or jungle of any kind the blood will often be wiped off a plain point, and you have nothing to show for it; and it is one of the very few rules of the game that if your claim is challenged you must be able to show the blood; that prevents any argument.

Of course, in this matter of "first spear" there is a certain element of luck, as there is in every decent sport, but in far the greater majority of cases it falls to the boldest rider. As a general rule it will be next to impossible to say who actually killed the pig, although it occasionally happens that the first man that comes up with him runs him through and kills him on the spot. More usually the first wound is nothing but a prick, and a fight follows in the course of which he takes such an extraordinary amount of punishment that no one could say which of his many wounds was the fatal one. So you all ride for the honor İf "first spear," and each man helps at the killing because as a rule he has to, if he doesn't want to run away or get killed himself.

As the tents are always pitched close to where you expect to find your pig, you have never far to ride before the fun begins. This is one of several advantages that pig-sticking has over fox-hunting, with its interminable rides to the meet and its still more interminable rides home again.

You start out the moment the sun is up, in order to get your sport in the cool of the day. Over night the natives, of whom there will be a tremendous number attached to the camp, will have watched down a sounder of pig, and before daybreak they will bring you what is called kubber, that is to say, information. So, knowing where the sounder is—a herd or flock of wild pig is called a sounder, and a sounder may number anything from ten to a hundred, though an average number would be between forty and fifty—you take up your station all together, down wind and under cover, where you can see without being seen—behind a clump of low trees, for instance.

Your sais hands you your spear and you are ready. If your horse has ever been out pig-sticking before, he knows by this time what is in store for him, and in all probability you will have your hands full for the next few minutes preventing him from kicking the others or being kicked. However, one member of the party will generally stand clear of the rest to watch the sounder away.

About fifty, or even a hundred, natives go into the long grass or low bushes or whatever cover it is where the sounder has been marked down, and contrive to kick up a most infernal din with old tin cans and native drums and, such-like instruments of music, and presently there will be a snort and a grunt and the whole sounder will break cover, crashing through the undergrowth with the old great-great-grandfather boar in the lead and his youngest great-great-grandson squealing in the rear.

Just at that psychological moment you will probably discover that your girth needs tightening. If that's the case you had better hurry up and tighten it, for things will be happening in a minute.

We will say the sounder is a good one, half a hundred strong. The old boar in the lead makes for some near-by cover that he knows of, where he can stow his enormous family in safety. He is awfully angry at being disturbed, and is simply spoiling for a fight already. But he is a cunning fighter as well as brave, and he wants to reconnoiter before commencing hostilities. If he could have his way he would lead the sounder into the new cover and leave it there while he returned to peer about from the outside edge of it. But more natives have been stationed to head him off and prevent that maneuver, so he makes for the open country with the whole tribe behind him, and all at once the leader of your party calls out "Ride!"

In a moment you are off in full pursuit, with your spear slanting across you out of harm's way. You will probably not need it for the next ten minutes.

THE moment you are off, the old boar sees you, and grunts, and the rest of the sounder turns immediately and bolts back to cover. He goes on with the object of drawing you away from his wives and family, and after him you go as fast as your horse can lay foot to the ground. You are hunting by eye and can not afford to lose sight of him for a second; and you are each of you riding for "first spear" and can not afford to give away a single point to the others.

It is each man for himself now, and the devil take the hindermost. The boar knows it and you know it and it is your own fault if your horse doesn't know it. Over slippery sheet-rock, through the densest jungle he can find, over fallen trees and blind banks and dry water-courses, through long grass where neither you nor your horse can possibly see what is in front of you, he will lead you the race of your life—ever mindful of the sounder, and ever drawing you away.

The race is to the swift, and you must ride like a fiend. The man who rides for a fall will surely get what he is looking for. Leave the going to your horse and trust to luck, or whatever else it is that you trust to; forget, if you can, that such things as nerves exist; ram in your spurs and ride—and watch the boar!

As you go, if the country is open enough, you spread out a little to give one another spear-room. You know that the boar will turn, though you do not know in which direction or when. That is where the element of luck comes in. You may, by dint of bold riding, be ahead of the other men and yet miss the "first spear," because he may take it into his head to tackle one of the other men first. They call it "jinking" when he turns, because no ordinary word could properly describe the sudden ferocious rush with which he does it. He has to have a word all to himself.

As you begin to gain on him you will notice his wicked little red eye as he glances from time to time over his shoulder to watch his chance. He is not going quite so fast now, not because he is tired—he isn't in the least, but because he means to fight and thinks that you are far enough away from the sounder for safety. He is an utterly fearless fighter, but cunning as a devil, and he will choose the moment, if he can, when he can take you at a disadvantage.

If he can catch you in trouble with your horse he won't let slip the opportunity. There will be a grunt and a rush, and over you will go—horse and rider together. If you are up close to him and your horse is timid and shies at him, as many horses will, he will charge suddenly into the horse's legs, ripping wherever he can reach, usually trying for the stomach, but he is not particular so long as he can rip something. If one of the other men does not happen to be near you, you will be lucky to get away with your life. He is a past master at choosing places where there is no room for you to use your spear, and when he does charge, your only chance is to meet him with the spear-point.

Just as at polo or football, you must "keep on the ball." Never give him a chance to come at you while you are standing still. In other words, don't stand still. He won't stand still for a second to give you a chance, and don't you either, for you can no more afford to take liberties than he can.

HIS activity will astonish you, The domestic pig, his first cousin, could not be described as an active animal, but the wild boar of India is more active than a dog. Few dogs could turn so quickly, and none of them could use their natural weapons with half his deadly accuracy. He grunts, and the foam flies from his mouth, and his wicked little eyes glare hatred and defiance at you—anything, in fact, but fear, and he charges, and "jinks," and charges, and rips viciously at everything within reach.

The more the fight goes against him, the more determined he becomes to do some real damage before he breathes his last. And his last rush, when he seems almost too weak to stand, is often more dangerous than his first. He is game right up to the very end, and it is small wonder that the men who hunt him sing a wild inspired song in his honor.

To tackle the wild boar you must learn to adopt his tactics of rush. Ride at him all the time, with your spear-point ready to receive his charge. Never thrust with your spear. If you do, it will run all down his back for a certainty without doing more than scratch his skin, and he will rush in under it and send you and your horse rolling over together. There are more enviable positions than under a kicking horse, with a broken bone or two and a furious devil of a boar seeking to gore you and the horse to death. So hold the spear steady, and the pace you are going and the pace he is coming will drive the spear right into him.

But don't believe that because you have driven your spear right through him he is necessarily out of action. With ten such wounds in him he can charge home and rip a horse dead. When his blood is up, what little pain he is able to feel serves only to make him more furious, for there is not a grain of cowardice in his whole system. He is not done for until he is dead, and he is quite clever enough to pretend that he is weaker than he is if he thinks that by doing so he can trap you into making a mistake.

He has no idea of quarter for either himself or you. You started the fight, but he'll make you finish it. If you draw off he will follow you and make you fight.

At Mhow, and at some other places in India, they sometimes turn live panthers loose on the plain, and hunt them in the same way. But the sport is not one-tenth so good, although the actual risk of life is possibly greater, because a panther, when he does turn, can spring on the horse, and one blow of his paw is sufficient to break a man's skull. But the panther is a coward at heart, which the pig is not. A panther runs for his life when he is charged by a mounted man, and only when he is wounded and hard pressed and sees escape is quite impossible does he make any attempt to fight.

When they hunt panthers in that way nine out of every ten of them are killed outright by a spear-wound in the back as they are trying to run away. Once he has made up his obstinate mind to give battle, a pig never attempts to run away. Over and over again he could probably escape, at all events for a time, if he tried to, but he doesn't try to. The idea never seems to enter his head. He means fighting, and he fights with every ounce of courage and fury and cunning there is in him.

IF you are reckoned a bold rider to pig, you are a good man indeed, and may hold your chin high. When you talk, you will find that other men will listen. But India is a land of bold riders, both native and foreign-born, and you will need to be something super-excellent in order to attract their notice. In a country where men are made familiar with death in some form or other almost every day of their lives, personal courage is taken much as a matter of course, and it is only the coward who excites comment.

If you can not afford polo under Western conditions, and fox-hunting has lost its zest, go out to India for a spell, join a tent-club and hunt pig. It's a better game than either of them. You've not only got to ride a squealing devil of a horse at full gallop across a country you would ordinarily hesitate to walk him over, but you've got to fight the pig at the other end of it. Yours will be the true spirit of adventure, for you will carry your life in your hand from start to finish. If you flinch, you're done for—hurt at the least, possibly killed. It's either you or the pig, and if you hesitate for a moment the pig gets you.

You will have to ride hard and straight, and keep on riding, and the hand that holds your spear must be steady, like the eye that directs it—steady from clean living.

If only once in your life you have seen the finish of an old gray boar in the early golden morning of India, you may truly say that you have not lived in vain. And as for trophies—one pair of three-inch tushes will give more satisfaction in the days to come than a dozen tiger-skins, for you will remember that you had to ride for them and fight for them and that it took every ounce of manhood that there was in you. They are not much to look at, but they will inspire memories of the finest, cleanest, manliest sport that is to be found anywhere in the whole wide world.

PIG-STICKING is one of the most democratic sports in the world, for this reason—that India, though a hotbed of autocracy and a tremendous stickler for good-breeding, will welcome, you, whoever your parents were, if you are a good man to pig.

There are two other phases of this sport of pig-sticking that serve to place it on a plane by itself—its usefulness, and its entire lack of cruelty. A boar is no ordinary beast. In the first place, he is so quarrelsome by nature that fighting comes natural to him. He would much rather fight than run away; and in the ordinary course of his existence he fights anything and everything that refuses to give way to him. He revels in a fight in much the same way that the old Vikings used to, and he will, generally speaking, go out of his way to look for a fight.

Supposing that he were not hunted by man, his death would come about in much the same way. As soon as some male member of his family imagined himself strong enough to get the better of him in mortal combat, there would be a pitched battle; and. sooner or later, as he grew older and lost a little of his tremendous strength, he would die fighting. Instead of being speared, he would be gored to death by a member of his own family. Probably the death that comes to him at the hands of man, while he is yet in his prime and before the edge of his fighting enthusiasm has been dulled by stiffness and old age, is the more merciful death of the two. And it is certainly better to kill him outright with a spear than to wound him with a bullet and let him escape to die a lingering and miserable death in the jungle. Fighting is the natural end of a wild boar, and probably if he were able to speak it is the end that he would ask for.

You may say "Why kill him at all? Why not leave him to the tender mercies of his own offspring?" The answer is that always where wild boars are hunted with the spear, there are villagers who are the poorest of the poor, whose scanty crops the boars play havoc with. Their numbers must be kept down, or the very existence of the natives would be at stake. By reducing the number of full-grown boars the size of sounders is kept within reasonable limits.

"Then why not exterminate them altogether?" The answer to that is, "Go ask the natives." Ask them how they would like to get along without the occasional employment and consequent hard cash that the sport of pig-sticking brings them. Ask the corn-sellers and grass-cutters. Ask the beaters who go into the long grass and drive out the boar. Ask the carriers who help to shift the camp. And ask the lowbred Mussulmans who gorge themselves on boar-meat when there has been a kill. You would receive an answer that would convince you, however great your unbelief.

So pack up your goods and chattels, and get an introduction from your friend, and, taking your courage and ambition with you, go and hunt pig for a spell in India. You will not regret it.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.