RGL e-Book Cover

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

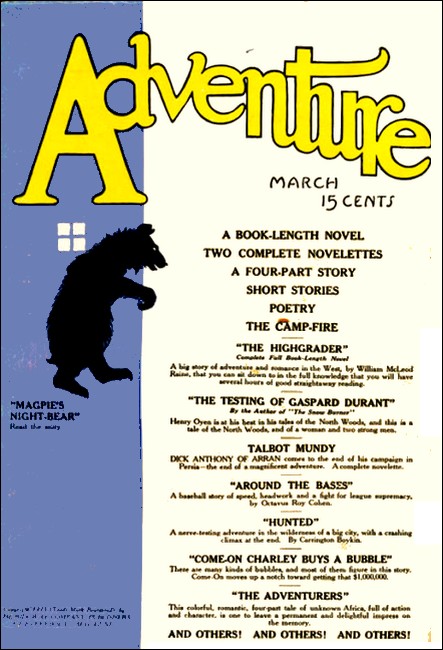

Adventure, March 1915, with "No Name!"

LET any man who doubts the love men bore Dick Anthony go ask the Persians who trudged through the mud behind him to fight whom Dick told them to. Ask others of that country, who never so much as saw him, but who formed their estimate of him from talcs brought home by those subjected to his discipline. Or ask Andry—grim, tremendous Andry.

Nowadays Andry is back in Scotland, near the Kyles of Bute whose rocks and cross-currents he knows so intimately. Marie Macdougal, who was Marie Mouquin with a knife-wound in her shoulder when this story opens, mothers the big man very carefully because the German saber-thrust between his fourth and fifth ribs is not quite healed yet. She objects to his talking of the past, for fear lest he go in search of Dick. So in the house it would be no use to ask him.

But look for him somewhere out among the fields or barns of Dick's estate by Lamlash, leaning on a stout ash sapling, stewarding Dick's worldly goods. You will find him dour, distrustful as he looks, and given like most strong men to deep silences; but he will answer, if you ask him what he thinks of Dick. He is likely to spit into his great leathery hands, look into the wind and ask to be shown Dick's equal.

There would be no use trying to ask Jenison, for if you could find him Dick would be somewhere near, since nowadays the two hunt new game together, and bigger game than ordinary. Jenison, being American and quite irreverent, would point Dick out to you and bid you throw a stone at him and see.

If you asked the Russian Government about him you would learn, if you learned anything at alL,that there is an opposite to love, too often misnamed hate, that really is a sense of guilt. But individual Russians will admit that of all their modern foemen Dick was the stoutest, most ingenious, and least corruptible.

Incorruptibility—the logical, completely unexpected—unworldliness, yet a most amazing understanding of the world—above all that calm effrontery that is the birthright only of men who deal in truth—sat strangely on a red-haired, bare-headed boy of twenty-five, in the rain on a devastated battlefield.

And he sat strangely—on the pole of a Russian provision-wagon—looking about him, listening and saying nothing. Strange men sat near him. On the far end of the pole was Jenison, fat and unshaven, looking dissolute through the gun-smoke that had blackened all his face. His eyes peeped red-rimmed through the grime, for he had served a gun all night, in the teeth of a whistling wind.

Completing the triangle, perched uncomfortably on a big, unopened biscuit-box, was the General of the Russian cavalry brigade that Dick had whipped. He was the only military-looking person of the three, for Dick wore no uniform, and Jenison would not have worn one had he had the right.

The General was in possession of his sword still, a fact which seemed to cause the American some slight uneasiness, for the butt of a .45 protruded from his torn hip-pocket and the heel of his hand was ready by.

"What's the time?" asked Dick.

Jenison drew out his watch with his left hand, and held it where he could see the time without losing sight of the Russian for an instant.

"Seven-ten," he answered. "Teheran time."

It looked more like the quarter-hour that just precedes sunrise, for the watery sky was screened by a curtain of rain, and the covered wagons loomed out of murky twilight.

"No sign or word of Usbeg Ali?"

"None."

"No sign of breakfast?"

"I can smell it!" said Jenison, peering through the rain in the direction of a wagon that Dick's servant had taken over from the Russians. Then a mud-draggled Persian, smothered from head to foot in blankets to keep off the rain, emerged from shadow, beckoning.

"Thank God!" said Jenison.

Dick looked at the Russian.

"Care to join us at breakfast?" He spoke as if the General were a free agent with a dozen or more alternatives.

"I would be glad," he answered in perfectly good English.

Even the defeated General observed the decencies, and spoke as if Dick were inviting him to a meal not plundered from his own commissariat. He may have found consolation in his certain knowledge that the eatables would be from cases packed in Petersburg.

DICK led the way to the General's tent and Jenison brought up the rear, with a hand yet nearer to his pistol-butt, for the Russian could have cut Dick down with his sword easily, and with Dick dead there would have been an end of the campaign.

"Sorry to have to use your tent," said Dick, "but I've none of my own. You caught me in a hurry, traveling light."

He motioned the General to a seat at the table, and the General unhooked his sword to lay it on the camp-bed. With a grunt of relief Jenison took his eye from the General's right hand for the first time in an hour. The only thing he had ever found that could make him nervous was Dick's disregard of a certain kind of chances. Now, utterly unnervous, he settled down to cat like an adventurer.

"Ah!" said Dick suddenly.

Jenison and the Russian each Looked up and followed the direction of Dick's eye toward the camp-bed. From under the one thin pillow there protruded newspapers.

"I'll have to trouble you for those," said Dick, and without a word Jenison got up and reached for them.

"They're printed in Russian," he said, handing them to Dick.

There were four papers, and Dick folded them without a word of comment. The fact that he knew Russian, and could read it nearly as fluently as English, was knowledge that so far he had kept strictly to himself.

They ate in silence, and the Russian proved a good trencherman considering the fact that he was a beaten man and therefore dispirited. The coffee and the canned food were not such as men generally share on battlefields, and presently the General produced cigars so excellent that for a minute or more the tent was filled with memories, and no one spoke.

"Are you holding me to ransom?" asked the Russian suddenly.

His eyes looked cunning, but his full, square-bottomed beard concealed the corners of his mouth, and he might have been merely inquisitive. Jenison pricked up his ears and crossed one leg over the other.

"At the present moment I'm waiting for word from Usbeg Ali Khan, my second-in-command," said Dick. "He's supposed to be pursuing the remnant of your force into Persia."

"What good will that do you?" asked the Russian, as a father might argue with his son, a trifle patronizingly. He waved his cigar in a gesture that the West has never learned to imitate.

Dick looked interested but did not answer.

"Mr. Anthony, the wise man, when he holds a momentary advantage, makes the utmost use of it! What use can you make of me? I speak in my own interests, and Russia's, as much as yours of course; but what do you propose to do with me?"

The rain drummed on the sodden canvas of the tent, and a little stream splashed on the table between them, but the sides of the tent were pegged down tight and no wind could blow in to disturb them, or the smoke that coiled in the air in rings. Dick stared very hard at the Russian, and Jenison stared hard at Dick, but neither said a word.

"You have been a very lucky man. Your luck, in sweeping the Caspian of Russian ships, was even more remarkable than your skill and daring. But you are a man of perspicacity; you must see—you must realize—that you can not go on forever defeating our regiments in detail, or winning such battles as last night's.

"Now, Mr. Anthony, at this moment is the opportunity to get from Russia' the best terms possible!"

STILL Dick said nothing, and still Jenison, who scarcely could be said to know him yet, watched him with the trained eyes of a business-man. He and the Russian were both looking for a hint of greed in Dick's face. The Russian was being disappointed, and Jenison was feeling pleased.

"Money, Mr. Anthony, is a thing we all affect to despise, but when we get right down to ugly fact, money is the thing we all fight hardest for. Russia has money; she has unlimited supplies of it. You have none. Am I right?"

"So far as you've gone," said Dick, "you're almost exactly right." And the Russian gathered heart.

"Now, Mr. Anthony, you are aware that Russia is faced at this minute with a war on two fronts. She has to deal with Austria and Germany at once. Time is a factor in the situation. Every living man who is already mobilized ought to be hurried at once toward the Austrian or German frontier. You appreciate that, of course.

"Yet because of this rebellion of yours in Persia, no less than half a million men must be held under arms—ah—in this part of the world. Now the release of that half-million men is worth a price. Name your price. Let me conduct negotiations for you. I was sent down here with ten thousand men to finish you; since I have failed, I can serve my country best by making terms with you. Name your price, Mr. Anthony."

"My price is known," said Dick. "I have never made a secret of it."

"Then, I have been ill-informed," said the Russian with a twinge of disappointment. "Will you be good enough to tell me?"

"The freedom of Persia, neither more nor less for Persia—and—"

Dick hesitated, for his private honor was a subject that he hated to discuss.

"And?" said the Russian almost eagerly.

"And positive proof for myself of my identity! Neither more, nor less, for me!"

"But—Mr. Anthony—be practical! This talk about Persia is visionary—the matter is an international one. I—"

"You asked me my price and I have named it," said Dick rising. "I shall have to ask you for your parole."

"I give it."

Dick pointed to a side-table on which were pens and paper. "Kindly write it."

The Russian did as he was asked and signed the few lines with a flourish. Dick pocketed the paper at the moment that a horse sploshed toward the tent outside.

Its rider dismounted. The salaams of a Persian orderly left no doubt as to the newcomer's identity.

"COME in, Usbeg Ali!" shouted Dick, and a moment later the Afghan swaggered in, with the rain running from his beard and turban, and his high boots muddied to the top. His eyes burned with weariness, excitement, and lack of sleep, but his bearing was heroic. "Bahadur!"

"Have you breakfasted?" asked Dick.

"Long since! I made a Russian cook it for me," he boasted with a sideways look at the General. "They are scattered, bahadur! There is not a troop of them left together! Ten of my men have ridden ahead of them, to tell the Persians what to do. They flee, but they run from the devil into Hell!"

"Have you called the pursuit off?"

"Aye; the horses are more tired than the men. They are resting, in a line spread east and west. Are the wires cut, sahib, the wires between here and Russia?"

"Ripped out by the roots!" said Dick. "I've ordered the poles burned."

"Good. Would God there were a way of knowing what move the Russians make, without disclosing ours!"

"There is," said Dick, looking at Jenison; but Usbeg Ali Khan looked straight in the eyes of the Russian General. Without a spoken word each knew that the other had in mind the Russian way of winning secrets from the tribes of Turkestan and Bokhara.

"You'd better get your man," said Dick; and Jenison, with a wry face at the empty coffee-pot, went out into the rain in search of one of his Americans.

"Give the General another tent," said Dick. "I have his parole. One sentry with orders not to let him out of sight will be enough."

Usbeg Ali Khan beckoned to the Russian, and the two went out together, the General leaving his sword behind. Dick tossed it in a corner and lay down on the cot to devour the Russian newspapers.

He found them beautifully censored. There were vague reports of Russian victories in Galicia and Prussia; there were columns of exhortation; there was mention of activity about the oil-wells, and comment on the fact that this war would be one of gasoline.

But there was no mention at all of the army of half a million men that Dick believed either ready to invade Persia down the east side of the Caspian, or else already on its way. And there was no mention of himself, Dick Anthony. He read the papers line by line, hurriedly, but missing nothing and making mental note of many things that others might have missed.

Then, with a frown at the necessity, he strode to the General's table to rummage among the papers there, and burst open the General's dispatch-box with the General's own sword. There were some obviously private papers that he sealed in an envelope unread; but there was a little book, and certain other documents, that he pocketed with a smile.

Outside, in rain that was running wheel-rut deep, and in mud that stuck to his heels, Usbeg Ali assigned the Russian General to a tent, placed a guard over him, and then— tired though he was—proceeded on foot to sec for himself what provision Dick had made for his fighting infantry. There was no semblance of a camp, yet he could hear snores from every hand, and it was not until he peeped into a wagon that he understood.

THE Russian wagon-train, half-parked, half-straggling and evidently caught in panic in the night, lay as the Russians left it when Dick routed them. Wagons were here, there and everywhere; and under each of them, on anything that they could find to raise them from the wet, in each of them, on top of the high-piled commissariat, to leeward of each of them, beneath pilfered tent-flies or any other cover that would shed rain, Dick's dog-weary infantry lay snoring, warm and dry.

In other wagons, provided by the Russian Government for Cossacks in a hurry, soup was cooking. In and out among the wagons strode a giant—a big spludge of something, scarcely visible through the rain.

The giant caught sight of Usbeg Ali Khan and came hurrying toward him, flourishing a stick an inch thick. He raised the stick and did not lower it until he was less than ten feet away.

"I thought ye were one o' the rrrrank an' file," he grinned, pulling off his tam-o'-shanter to shake the rain out of it. "Mr. Dicky's orrrrders are tae lick the thunder out o' all except the cooks that dinna rest, an' tae lick the cooks if they du rest, I was about tae lick ye!"

Usbeg Ali chose to change the subject, for his dignity was dearer to him than his life. Besides, as second-in-command, he was Andry Macdougal's superior.

"What are they cooking?" he demanded. "Food such as the Russians eat?"

"Ah! Listen tae him! Suspeecion's the sperrit o' an Afghan! Dinna fash y'rsel'! There was a herd o' gude cattle wi' the Roosians, an' Mr. Dicky had the throats o' fifty o' them slit, so y'r releegious scrrrruples will na' be vexed. Man, ye luke wearrrry—y'r eyes burrrra in the sockuts—he advised, and fin' a place to rest y'r banes a while. Listen! I'll gie ye mine until I want it— I've made me a gude nest!"

But Usbeg Ali laughed and shook his head.

"Allah made my bones to hold a soldier's back straight!" he answered. "They'll rest when convenient to me! What of the dead? This is the first time he has made no special disposition of the dead."

Men spoke of Dick as "he" and "him" on that campaign, since he had told them that his name was "No Name," and Andry was not in doubt for a moment as to who "he" was.

"Suspeecion again!" he snorted, shaking the rain out of his cap a second time. "Gang an' luke! Gang an' luke yonder, where the Roosian prisoners are!"

Andry pointed eastward, and Usbeg Ali Khan walked off in that direction without another word. There were not many Russian prisoners, he knew, for he and his horsemen had chased all they could find southward into Persia where the natives waited for them; still, he realized some men must have been taken among the wagons, and no doubt some had tried to bolt back along the road to Russia.

He came on about two hundred men sooner than he expected, employed at a task they were ill-fitted for after a long night's battle. With some picks and shovels, and a motley assortment of improvised tools that included even swords, they were digging two long trenches, twenty feet apart and parallel, that could have but one grim purpose. They were supervised by some of Dick's non-commissioned officers; and others of Dick's men, armed and very much alert, were in charge of other weary prisoners who carried in the dead of either side with strict impartiality and laid them in long lines beside each trench.

The trenches were half full of water, and the tools sucked stubbornly through gluey clay.

"How many dead?" asked Usbeg Ali.

"As yet we have found seven hundred lacking nine of our own men, sahib."

"And of the Russians?"

"More than a thousand, and that not nearly all. There lie many more not brought yet."

USBEG ALI muttered a Moslem prayer and turned away. As the morning light shone stronger through the downpour he could see Dick Anthony standing, bareheaded as always, at the entrance to the Russian General's tent. Dick's arm was stretched out, and a dozen men were listening to him in the rain with rapt attention.

"What is he ordering now?" the Afghan wondered. "He forgets nothing and nobody! He is a man who is twenty-five; and I, who am Allah knows how old, am a child in war beside him! Yet Allah made me no mean soldier! Praised be Allah!"

He saw the men depart their different ways, and then watched Dick walk to a wagon near at hand that was very closely guarded. There were ten men posted around it, with fixed bayonets. From the opposite direction Jenison was coming with one of his Americans. The wagon was a strange one, of a type that Usbeg Ali in all his soldier experience had never seen.

From the middle of it rose a jointed pole to a great height, and from that were suspended wires that seemed to have no conceivable use, nor connection with anything except the wagon. But Dick seemed to regard wagon and wires with interest, so Usbeg Ali hurried, curious as a child. He arrived face to face with Jenison.

"Here he is," said Jenison. "This man can make a wireless out of a corkscrew and an old clock. He can work any kind of telegraph blindfolded, upside down, and drunk."

"Is he sober now?" asked Dick.

Jenison pushed the man forward and he stood with the air of being glad of the opportunity to see Dick at close quarters.

"Know any Russian?" Dick asked.

"No."

"Um-m-m! Look the machine over. See if it works, and let me know. Don't send a message of any kind. Listen for messages. Understand?"

The American nodded, and Dick watched him climb into the wagon.

"Now," said Dick, "come closer, Usbeg Ali. From what the General said to me at breakfast—you heard him, Jenison—it's clear to me that there's nothing in the way of troops ahead of us. These ten thousand were depended on to drive us eastward. And to make matters sure they've had nerve enough to send all they had. The ten thousand we have just beaten were all that stood between us and Baku; or he would not have been so anxious to bribe me."

Jenison nodded, and Usbeg Ali Khan stroked his wet beard reflectively.

"Come into my tent," said Dick, leading the way, and Usbeg Ali Khan thrust himself in front of Jenison, determined to assert his seniority and precedence at once to save confusion later.

Jenison gave way to him, but there was a flicker of amusement on his face that might have given the Afghan food for thought had he seen it.

The minute he got into the tent Dick produced a map and spread it on the table.

"Here's Tabriz," he said. "Practically all the mounted men the Russians had in Tabriz were with this force. I know that from prisoners. The few left behind to garrison the place won't amount to much. We can slip by Tabriz, between it and the Caspian. Then— d'you see—Baku lies naked at our feet, two forced marches beyond!"

"By the blood of God!" swore Usbeg Ali Khan.

"Looks like our meat!" grinned Jenison, rubbing his left ankle with his right heel as he always did when he felt jubilant or very much excited. He had rubbed a hole in his shoe the night before, when his gunners got the range and the shells exploded one after another at the spot intended.

"It means this," said Dick. "We can cut their communications east and west, and very likely paralyze them."

"How d'you mean, paralyze them?" Jenison demanded. "We're less than eight thousand, attacking millions. We can do damage;—just damage. Let's do it, but what's the use of being over-sanguine."

"I said paralyze them!" answered Dick. "I meant it." He laid his finger on the map again, and they stooped on either side of him to see. "Baku is—"

As he spoke, a Persian orderly came in, salaaming low.

"The Merikani in the wagon says the machine works," he announced.

"Tell him I'm coming!" Dick felt at his pocket to make sure the General's little book was there. "Go and sleep, you two men! Talk to you later!"

WHATEVER it was—instinct, intuition—it surely was not what the world calls knowledge—that, assured Dick Anthony he had a clear, straight road to Russia's vitals, it was confirmed step by step, point by point as the day wore on, and his swift-thinking mind pieced circumstance to incident and made an accurate conjecture of the whole.

The wireless-apparatus worked, as Jenison had prophesied it would. Sober as a judge, since there was no whisky anywhere, the most ingenious telegraphist that even the United States had ever grown too hot to hold imagined himself drunk as he took down letter after letter but completely failed to string them into words. Dick, sitting beside him in the wagon, checked off the letters and put pencil-dots at intervals, silent except for deep, steady breathing,

"Make head or tail of it?" the expert asked.

"Yes," said Dick.

When the instrument quit talking for a while, Dick drew out the General's little book and assured himself that the system of dots meant something. There was a page at the back of the book that dealt with nothing except dots. Then he sat on the wagon-tail with his legs in the rain but his body and hands inside, and started to decode the inside secrets of the most secret bureaucracy on earth.

"Where are you? Where are you? Where are you?" was the first part of the message, repeated a dozen times until apparently the operator at the other end grew tired of asking.

"Send out something indefinite," said Dick over his shoulder. "Send some word that'll let them know they're in touch without giving anything away."

"Easy!" said the expert; and he sent a signal that is part of the international code, and so well known that armies use it in their casual conversation. Instantly the tune was taken up from the other end again.

This is Baku. Where are you? Where are you? Why are the overland wires down? What is happening? Why don't you answer?

"Can you make it seem," said Dick, "as if we can receive but not send?"

"Sure," said the expert, wondering whether Dick had brandy in his tent and whether he would be likely to reward good service with a bottle of it.

Eying him sharply from the wagon-tail, Dick was thanking his stars that Jenison had such a man in his outfit. Incidentally he registered a mental vow that the man should drink water or go dry until the campaign ended.

After about five minutes more of frantic questioning the tale from the other end began to shape itself into the form of coded orders, repeated over and over again for the sake of certainty.

The Princess Olga Karageorgovich must be rounded up and held. Find out from her where the papers are. Don't trust her again on any conditions, or for any reason. Send her back here under close guard, unless....

A word followed that seemed to have no meaning, although Dick searched the code-book thoroughly. He pressed an arm against a bulky package underneath his shirt, and seemed to find pleasure in it.

"Send some sort of a fluttering answer," he said. "Let 'em feel sure we're listening."

Baku soon resumed in code:

Conditions on Prussian and Austrian fronts are serious. It is essential now that the men with whom you are supposed to act in concert be withdrawn for use in Europe. Not possible otherwise to mobilize East enough to meet conditions. You must work alone. No force will invade Persia from the east side of the Caspian. Press forward, but confine your efforts to recovery of the stolen plans tot our invasion, because owing to present conditions should Great Britain protest your presence in Persia you must be withdrawn. Above all things «et those plans. Try to trap Anthony. If the Princess has the plans already, get them from her. In any case get rid of Anthony, and get the plans.

DICK, worked with the code-book, pencil and a piece of paper, until he had an answer coded to his satisfaction. It was a risky game to play, to send an answer, for he had no means of knowing what peculiarities of style the General might have, and to have aroused suspicion would have been to throw away nine-tenths of his advantage. But he decided the risk was worth it.

Not knowing what he sent, the expert at the key flashed back to Baku—

Please reconsider.

The answer to that was immediate;—

Impossible!

Dick sent back, after an interval of worrying at the code—

Then reinforce me with ten thousand men.

Evidently the captured General was a man whom people humored as a rule, for they tendered him an explanation at some length.

Impossible! All troops available are being rushed westward. Speed is the great factor. The sooner you get the plans and finish Anthony, the better, because your ten thousand men would be very useful. Hurry. Let Persia wait until afterward. Can probably be made subject of ultimate peace negotiations. But get the plans and finish Anthony before you hurry back.

That seemed to be all Baku had to say for the time being, for the expert reported nothing further coming through.

"Stay there then and write down whatever does come without answering," commanded Dick. "Send for me if they begin any rigmarole."

"By the way—" said the expert.

"What?" asked Dick.

"My nerves are in a rotten state, and I'd like some brandy."

"Oh," said Dick, and he walked away abruptly.

He met Jenison, sore-eyed from lack of sleep, heading for a tent that somebody had pulled out of the loot and pitched for him near Dick's.

"That wireless-man of yours " said Dick.

"Yes—what about him?"

"Has just asked me for brandy."

"Don't give it him."

"Exactly, but before you go to sleep please set your next best man to watch him. Promise both of them a drumhead court-martial if I can smell drink on the breath of either!"

"Good!" said Jenison, who knew his men and how they should be handled.

DICK went back to his newspapers, and to rummage among the General's belongings. He found and studied the General's campaign-map that showed where the roads were, and the wells, and what forage and provisions might be expected at places on the road. He compared that map with his stolen, secret one—the map that betrayed intended treachery and that Russia now had sent ten thousand men to find. Then he sent for a prisoner who had talked already, and asked him again a string of questions whose gist the man did not understand.

The fellow stood at attention, dropping his eyes when Dick looked straight at him, shifting from one foot to another and looking about him wildly whenever Dick looked away.

Rain swished and drummed on the tent; wind whistled through the ropes and kept the fly snapping. There was no more light than filtered dimly through wet canvas, nor any other sound inside the tent than their two voices—Dick's insistent, and the other's sullen and afraid—except the drip-drip-drip of a tiny stream of water on the table.

"Who told you there are no more sotnias—no infantry, no artillery—marching south behind this cavalry-brigade of yours?"

Dick spoke in Russian, now that there was nobody to hear except the Russian; his unaccustomed tongue had trouble with the consonants, but the man did not need to ask him to repeat his question. There was something about Dick Anthony that made him understandable to any one, in any tongue, when he wanted to be understood.

"It is known. They all know."

"Who know?"

"They. The others. There were half a million men held these months long, east of the Caspian; it was known they were for Teheran, and for God knew what beyond. There were mutinies—not big ones, but many little ones, and there was grumbling all the time. None wanted to invade Persia, for what had Persia done? We of the army are Cossacks, Turkomans, Armenians; what grudge bear we against the Persians? We did not want to go."

Dick nodded. It was not the first time he had found out that the Russian soldier would prefer minding his own business if his rulers would let him.

"Then came news of war with Germany! Then, as if God had touched Russia with

His finger—so—and turned her into gold, all was changed in an eye-flash. What had been mutiny was discipline. What had been sloth and hanging back was eagerness. What had been many minds and many purposes was one. Russia is one now, and we all prayed that we might light for her. Men forgot Persia. We prayed for leave to march westward."

Dick nodded, taking care not to look directly at the man, for fear of disconcerting him. Sideways, from under lowered lids, he was studying more than the psychology of serfdom; he was weighing the man's words; he was sifting word by word, hunting for the truth. And in the end he rejected not one word of all that the man said, for he knew truth when he met it. Like every other Russian, and in spite of the ruling caste, this man loved Russia with the whole of his peasant heart, and knew but one grief at that moment.

"There was nothing printed—no news; yet word went around that every man was needed, and we came. I am a reservist. My time is nearly up. I have nine children to provide for, and I am a widower. But I came.

"God will protect my children, so be I fight for Russia. But this—this southward march—this is not Russia's business! It is no wonder we are defeated in a night— it is the hand of God! The half-million received orders to march westward against Germany. Only we ten thousand—we miserable men—were sent down lure. None were to follow. We were to hurry on some secret business, and hurry back.

"We are beaten. God willed it. Now nothing matters. There are no more who follow us. The troops all march westward, by road and train, on foot, on horse, and in motor-cars."

DICK'S face moved slightly. He gave the same impression that a hound does that hears the almost inaudible.

"Motor-cars?" he asked.

"Aye! God knows where they come from. None knew there were so many in all Russia, Every sort and kind of motor-car, loaded with men. More men go by motor than by train, and men say it is so all over Russia."

"Then, if I retire into Persia, will Russia not send an army after me?"

"Why? Men have forgotten Persia! The road leads westward. Every man whose feet and heart are good goes westward. There would be rebellion if an order came to march into Persia!"

"Very well," said Dick. "Here is some money for you."

He counted gold from the General's cash-box, and gave it to him. The man laid the money on the table and burst into tears.

"Let me go! Let me go and fight for Russia!" he demanded.

"You shall," said Dick.

The man stared open-mouthed.

"You shall go with me."

"You! You? You will fight for Russia?"

"Is England Russia's enemy?" asked Dick.

"Nay. Men say—I have heard—England and France and Russia—"

"I am from England."

"Then—"

"It is time," said Dick, "for you to return to the guard-tent. Can you hold your tongue?"

"Surely. None better."

Dick laughed. For a man who had just laid bare every single secret that be knew this fellow had a strange conceit of himself.

"If you talk in the guard-tent," Dick assured him, "you shall not go back to Russia. You shall be hounded into Persia along the road the others took!"

The man laid a work-calloused hand across his own mouth.

"I am silent on all points," he said, "until I have leave to speak!"

"What is your name?" asked Dick, taking a pen as if about to make a note. But the man did not answer, and Dick could not coax another word from him. Satisfied, he raised his voice into a shout that carried against the raging wind and rain as far as the orderly who waited twenty yards away.

"Take him to the guard-tent, and have him watched closely," he commanded when the orderly appeared.

Then he pulled on the military-cloak that Andry had robbed for him from the man who plundered it from the body of a Cossack officer, and set out, face to the rain, for a distant wagon around which a guard was set as if it had been another wireless-plant.

On his way he sighted Andry and waved to him. The big man turned and followed into the wind, leaning forward like a gnarled tree; something around his neck streamed out behind him like a storm-wrenched bough. The two were side by side when they came to the solitary wagon, and the guard presented arms. Dick stopped, and Andry strode closer to peer in.

"Ye may come!" he said tersely over his shoulder to Dick.

DICK first, and then Andry after him, climbed into the wagon by a wheel, and sat down on some grain-bags opposite a plump, pale woman who sat propped up on a litter. She smiled at Andry first and signaled to him with her eyes before she greeted Dick.

"I want you to remember," Dick began.

She nodded, for since Marie Mouquin had let curiosity get the better of her, and had taken the consequence in the form of a knife-wound, she had studied reticence. As women of her type may always be depended on to do, she had gone from one extreme to its opposite.

She had detested Andry once; so now she loved him with all the fervor of her French heart. She had always been garrulous; so now she imitated Dick and grudged words, especially when first spoken to. She had been faithful to the Princess Olga Karageorgovich, in spite of cruelty and crime; so now there was no limit to her disregard for the ties that had been. She nodded three times running.

"When you first saw me in Egypt—" Dick leaned toward her and spoke slowly—"the Princess was plotting a rebellion in Egypt against British rule. Was she doing that on behalf of Russia or on her own account?"

Marie smiled.

"On behalf of Russia," she replied.

"Are you sure? Positive? Had you any proof?"

"She has no money of her own—not one sou," said Marie Mouquin. "Yet in Egypt she gave away more than a million roubles. Is that not proof?"

"Was she playing Russia's game or her own, then, when she tricked me into landing in Russia instead of Turkey?"

"Both. She wanted you. She used to lie awake all night and sob for you. But she knew that she could only win you by using you for Russia's ends, and so making use of all Russia's resources to compel you."

"Did she invent this scheme to invade Persia?"

"No."

"Are you sure?"

"Quite sure. But she knew of the plan. And the idea of driving you into Persia, to become an outlaw and so give excuse for the invasion, was all hers. She stipulated that afterward you should be hers—her reward—to do with as she pleased. They trusted her. They let her have authentic copies of the maps and plans. It was only after I stole the plans for the invasion and sent them to Andry that they lost confidence in her and her downfall began—or so I think."

"Are you sure, beyond any doubt or possibility of doubt, that Russia had this half-million men ready to invade Persia? Are you sure the plan was not just a plan, just a scheme concocted by the Princess, that she intended but that the Russian Government did not intend?"

"You have the plans," said Marie Mouquin. "You have seen them."

"But I haven't seen the half-a-million army!" answered Dick. "Are you sure it was meant for Persia?"

"Mr. Anthonee, I know!" Now it was Marie who leaned forward and spoke slowly, earnestly. "All those months long I lived with her. Often I shared her bed. I ate with her. I wrote her letters. I was secretary, maid, confidante, stalking-horse, scapegoat, everything. Should I not know?

"Why, I have spoken with the men who came to her from beyond the Atrak River and begged her give orders to advance. They told me the men were mutinous from inactivity. They begged me to persuade the Princess to give orders. It was all in her hands then. Mr. Anthonee—"

She leaned further forward, so that Andry held an arm out to restrain her. Then she continued:

"You think you are unfortunate. You call yourself 'No Name' because Russia took your name away. I assure you—I swear to you that she, and only she, is answerable for all your trouble! It was she who advised the Russian Government to cable London an account of your death and burial at sea. What lies has she, or any one, been telling you now that you doubt at the last minute?"

Andry cleared his throat with a noise like a dog quarreling about a bone.

"I dinna doot 'at Jezebel was a lovelier lass, an' mair respectable than she!" he growled.

DICK did not answer. Nor did he doubt. He had the gift of seeing things in better perspective and with broader view than most men. It did not trouble his red head if people mistook his infinite pains, his care in sifting and re-sifting evidence, his fairness and honesty, for doubt. He would have liked to believe that England's ally was honest; but he did not believe it. He was more sure now than ever that the half-million army had been meant in the first instance for a hand that should reach out and seize the Persian Gulf.

He asked no more questions, made no more remarks. He left the covered wagon as he had entered it, in silence and without excuse, vaulting over the end into a pool of liquid ooze and walking ahead regardless of the rain and of the fact that his cloak was all undone.

He did not know whether he was wet or dry. He had gone a hundred yards before he noticed that Andry Macdougal was not with him. Then he turned as if shot, and his strange strong voice, that could carry through the din of battle when he raised it, blared through the storm as no bugle ever did.

"Andry! Come out of that! Come along!"

One foot at a time, and slowly, the giant let his six-feet-five of beef and bone descend to mother earth. It was not the mud nor the rain that made him reluctant, nor the wind that made him look sheepish as he came.

"Go and sleep!" commanded Dick. "But listen, first! That's an honest woman. An honest woman with an army—with an army that began by being more than one-half bandit—is in a predicament. I'll have you understand, my man, that I'll thrash the lout who gives any one excuse for gossiping about her. Understand me?"

"Aye!"

"Until we can find a minister who can marry you, you'll take no liberties!"

"Aye. I ken. Mr. Dicky—"

"Eh?"

"I apologize."

But Dick had forgotten him and the incident. He never could bother himself with what was done with, nor clutter up his mind with useless memories, even for a second. He was striding forward with the rain behind him, thinking of the last part of the game that lay ahead.

HE passed Usbeg Ah" Khan on his way, heavy-eyed now, waiting in the rain for word with him.

"Bahadur—"

"Go and sleep. You need it."

"To hear is to obey. But—"

"Go and sleep!"

Dick passed on, as if to hear were really to obey, but the Afghan hurried after him. "Bahadur—"

"Is the camp safe?" Dick asked him.

"Aye, but—"

"Are the pickets placed and under cover?"

"Aye, but—"

"Go and sleep!" said Dick, turning on his heel and striding forward.

So Usbeg Ali Khan, gentleman adventurer of swarthy skin and gallant heart, went to a nest his man had made for him between some grain-bags and slept as adventurers may do occasionally when their ten-man task is done.

But Dick did not sleep. Not even the wish to sleep occurred to him, though he had fought and won a battle through a long, wet night, after a long day's march with men who had to be watched each mile of the way. Great men have the trick of waking when Dame Fortune's stakes are on the table and the game is on. He lay, hour after hour, on the Russian General's bed, with his muddy boots on the General's private blanket, and thought out the problem point by point.

It seemed to him that Russia had not wanted the war in Europe. The idea that England and France might have wanted war drew a laugh from him. It began to look to him as if England, France and Russia had been forced into a fight quite unexpectedly, and therefore as if disclosure of the ugly facts about Russia's previously contemplated treachery would be disconcerting. Russia, it seemed to him, would be likely to pay a big price to keep back those facts.

"For the sake of England and France," he said to himself, "I'll save Russia's face for her. But she shall pay the price to Persia and to me in full, and in advance! Who sups with Russia, Richard Anthony, sups with a long spoon or goes hungry, and we're hungry enough—too hungry. We'll use the spoon!"

He arose and opened the tent-flap an inch or two.

"Call me in four hours' time exactly!" he ordered the man on guard.

Then he lay on the General's bed, and was asleep in less than thirty seconds, sleeping like a little child.

DRESSED as a Persian woman, on a horse that Dick had given her, carrying a steel box that Dick had let her take, the Princess Olga Karageorgovich spurred into Persia past a line of Russian fugitives who fled from Usbeg Ali's cavalry. She ignored Russians and Usbeg Ali's men alike, for the Russians were supposed to be her own, and Dick's leave to be gone was passport enough to protect her from recapture.

There were two exactly parallel deep wrinkles on her brow, that changed her face, as by a miracle, from captivating charm to freezing repulsiveness. Under them her violet eyes glowed sullenly, and her parted lips, that showed two even rows of exquisitely modeled teeth, were hard and straight. From behind she still may have looked like a woman to be loved and followed, though a man who noticed first the laboring of her horse and her disregard of the beast's necessity might have reached a different conclusion; from in front there was no mistaking her as some one to avoid.

Not that she sought company. She turned in the saddle to tongue-lash runaways who dared keep too close to her, and those ahead hurried away to left and right to give her the road and avoid the whip she wielded.

When, before many miles, there was a choice of two roads and one of them curved eastward toward the Caspian she took that one, to be out of the path of the pursued. And once alone—once in a hollow where she was not likely to be seen—she watered her horse, and hobbled him to graze, tying the rein cleverly around his foreleg.

She neither drank, nor rested. Going straight to the hardest, sharpest rock in sight she toiled for twenty minutes like a mason, trying to burst the steel box, until her knuckles bled and she sank to the earth exhausted. She fell asleep there, with her forehead resting on the box and her lips muttering either a prayer or imprecation.

The time was not long gone when she would not have troubled herself to open the box, provided only that she had been sure its contents were intact. Then, when she was Russia's Secret Government's first representative and knew her instructions all by heart, her mind had been only occupied about the practise of the plan.

Now, since Russia had done with her and Dick Anthony would have none of her, it was her business to find out just what she bad left with which to bargain, A sickening thought, half-dream, occurred to her as she moved to ease her limbs, and in an instant she was wide awake again, hammering the rock.

Why had Dick Anthony dared let her have that box? If it contained, as she thought it did, plans and a map that would prove the Russian Government a traitor to its ally, Dick could have made a better bargain with it than to toss it to her as the price of riddance.

He could have bought Russian citizenship, a commission in the Russian army, and a million roubles with the contents of that box, and he must have known it. Yet he had let her take it. She recalled his words as she knelt with the box raised above her head, poised for a downward crash against the rock with all her strength.

"You may take it as the price of your departure. I will bribe you with it!"

The words stuck in her craw the more uncomfortably because she had accepted the bribe, and because the thought kept coming to her that Dick did not deal in bribes as a rule. She grew convinced that there was a trick somewhere, that she had been fooled, that Dick had been laughing at her when he let her go with what she thought such a prize of prizes. She doubled and redoubled her efforts to smash the box open; but it had been pressed at the Russian arsenal from armor-steel, and she did no more than chip the lacquer from off the outside.

AT last, sobbing from her effort and from rage, she caught the horse again and mounted. She was not in such a hurry now. She did not flog so desperately, nor lean forward in the saddle. Nor did she continue on the road to Persia.

At a slow amble she rode back toward Dick's camp, avoiding Russian fugitives as much as possible, and refusing to have word at all with those who managed to throw themselves in her way and ask advice or orders. She rode for several hours, until she was brought to a stand at last by one of Usbeg Ali's outposts.

"The other way!" the man ordered. "None pass this way! Back into Persia!"

But Dick had forgotten when he gave her the box that for a month past it had held his valuables and had been carried by an orderly who treated it as sacred. The man had magnified his office until Dick's army grew to regard the box as some sort of almost-magic talisman, and now it rested in front of her, on the pommel of the saddle.

She raised it, almost without thinking. The man saluted at once, and quick as lightning she divined the reason. She held it up high, and the man made way for her. Since long before history was written the caliph's ring, or the emir's jewel, or some other article known to belong to royalty has been an unchallengeable passport throughout Persia and the greater part of Asia.

She rode on unmolested. It was not until after a wordy argument with a dozen of his fellows and an officer that the man spurred after her, and past her, and carried word of her coming through the rain to Dick's camp. And even then the orderly outside his tent refused to wake Dick until his stipulated four hours' sleep was over.

So the Princess sat in the rain and waited for him—a wet, lone woman, on a dispirited-looking horse—and Dick, awake at once when the orderly called him, strode out unexpectant and met her face to face.

"I have come to ask mercy!" she said instantly, speaking before he could say anything. "Is there any mercy in this camp? There is none outside."

"What do you mean?" demanded Dick.

"Mean?"

She held the box out. Then she tossed it to his feet, and for a moment he supposed that she had found some way of opening it already, and had discovered his trick. He turned it over with his toe, and it was only then that the truth dawned on him, and with it a new idea.

"Nothing less than dynamite would open that!" she said. "What use is it to me? How do I know what is inside it?"

"And she wouldn't dare use dynamite, of course," thought Dick, "for fear of destroying the contents."

"What use do you propose to make of the contents?" he asked her.

"Sell them! Sell them, of course! Sell them to the British! They are worth more to Russia, but Russia would bargain with me and then send me to Siberia! I will sell them to the British, in return for protection!"

"Where do you propose to make your bargain with the British Government?" Dick asked her.

"Where else but at Teheran? I might get through to Teheran, and there is nowhere else to turn."

"I will give you a pass and an escort to Teheran," said Dick, "provided when you get there you will give the box and its contents to the British Minister. I shall add a letter to what is already in the box, and something else. In the letter I shall say that you will prove my identity!"

Their eyes met. She remembered a former occasion when he had offered to regard her as a friend if she would ride to Teheran and prove him Dick Anthony of Arran, as only she could have done. She remembered his scorn when she refused him. Then she had been at the zenith of her power and believed that she could wear Dick down into submission to her; now she was a suppliant for mercy, and her eyes fell in front of his. ~

"I surrender!" she said quietly, and then she dismounted into a foot of slimy mud.

DICK shouted for his orderly, and sent the man running to bring Usbeg Ali Khan and Jenison, keeping the Princess waiting in the rain for ten more minutes until his witnesses were there. Usbeg Ali Khan, when he came at last on a horse that needed forcing into the downpour, evidently thought he had come to see an execution.

"Which is it to be—hanging, shooting, or burning alive?" he asked pleasantly.

But Dick led the way into his tent and sent another orderly hurrying off to the women's part of the camp where the wounded were being cared for.

"Get some kind of a change of clothes for her!" he ordered. "Get them, d'you hear me! Don't dare come back without them. Then see that she has a tent, or some place in which to change!"

Dick laid the box, all muddied, on the table and produced its key. He opened it, and the Princess gasped. Usbeg Ali grinned.

"Blank paper, and a few out-of-date muster-rolls, you see! Nothing much to bargain with!"

Dick was looking at her eye to eye across the table; the pupils of his eyes dilated to make the most of the dim light.

"Then you cheated me! Then you tricked me!"

"I tricked you. Yes."

"Bah! A bandit's trick! A trick for the sake of trickery! And to what purpose? To get rid of me? I would have gone in any case!"

Usbeg Ali laughed aloud, and Jenison looked uncomfortable. He was trying to combine American ideas on the treatment of lone women with his other, equally pronounced and soldierly notions about spies and treachery. The man in him told him to be sorry for the Princess; experience and intuition bade him caution Dick. He compromised by holding his tongue and looking away when the Princess glanced at him.

"There shall be no trick this time," said Dick, emptying the box by turning it upside down. "Perhaps you recognize this?"

The Princess nodded and her fingers twitched as she recognized a letter that had been enclosed with the map that she proposed to offer to the British. It was a letter of four closely written pages, explaining much that was on the map. It would be enough to interest the British Government, and to excite its curiosity to know more, but it would not be enough in itself to convict the Russian Government. Dick put it in the box.

Then he took pen and paper, and wrote a short letter on one sheet that he showed to nobody. Signed, but unsealed, he put it in the box with the Russian letter, and holding the box up in full view of the Princess he locked it, putting the key back in his own pocket.

"Now," he said, "I'll send this key by a man whom I can trust to the British Minister at Teheran. The man shall leave within an hour. You—" he looked straight in the Princess' eyes—"shall leave for Teheran at dawn tomorrow with an escort of ten men, and you shall carry the box.

"If you can satisfy the British Minister that you are the Princess Olga Karageorgovich, and that I am Richard Anthony of Arran, you will be able to make terms with him I think. You may tell him he will find me at Baku! Let me have one of your Afghans, Usbeg Ali, to carry the key, and ten dependable men to ride with her at dawn. Thanks.

"Now, is her tent ready? Are dry clothes in it for her? What kind of clothes? Persian? Very well, that can't be helped. Understand me, Usbeg Ali, I don't want to see her again. You see to it that she and her escort leave at daybreak!"

"She shall leave or die!" growled the Afghan.

As the Princess walked out she nodded to Dick familiarly, ignored Jenison as a person of no importance, and laughed at Usbeg Ali Khan; but she followed the Afghan to the tent assigned to her, and once she was inside, he set a guard closely spaced around it.

DICK ANTHONY'S determination—that was summed up from his point of view by the motto of his family: "Agree with thine adversary quickly!"—was doubled now, and a fire burned in him that was contagious. More seemed within his reach than met any eye but his. He had set Persia first and himself last, and would keep that order in his mind until his last pledge was fulfilled, but he was no less zealous because his own reward loomed large beyond a cloud of difficulties.

Difficulties! It needs difficulties to bring out the manhood of such men as Dick. A good horse is not wasted when the course is long and the going bad; nor is a good man thrown away if matched against the almost overwhelming. But encouragement is good in either case. Having nothing of the demagogue about him, nor more of the visionary than a man of practise should have, Dick did not dream that Persia would be other than ungrateful to the end. But he saw his own reward ahead, entirely apart from Persia and her destinies; and the cause of Persia grew terrifically more ascendant in proportion.

"You look," said Jenison, stopping him on his way across the camp, "like a boy who is going to eat pie!"

"I am," said Dick, and Jenison stood still in front of him blocking the way that he might study Dick's face and bearing better.

Rather fat, muddied to the hips, troubled a little by his rheumatism, Jenison looked exactly the part of a gallant gentleman who is game in spite of the odds, and means to see the thing through to a finish. His smile was glued on, so to speak; he kept it there as the gentlemen adventurers would wear their ladies' gloves in other days.

But looking at things from a common-sense American business point of view (as in his very nature he could not help doing), he could see very little percentage in a raid into Russia with eight thousand men and six guns. There might be fun in it, perhaps, but little profit. Besides, since the fight of the night before they were running very short indeed of ammunition.

"Punkin pie!" he said, grinning up at Dick.

"I never tasted that kind," Dick assured him. "But I get your meaning. Yes. I'm coming into my own at last."

Jenison looked from left to right and all around him. There was none to overhear, for all the men and officers were busy under Dick's orders, and Dick was crossing from one shelter to another to inspect. He looked back, straight into the rain at Dick's eyes.

"I've only known you a few days," he said, "but I'm interested. I'd like to know what your idea of the ultimate attainment is. Tell me and I'll keep it secret, if you say so."

"A commission in the British Army," Dick said quietly.

"A commission—in the British Army! You?"

"Why not?"

"Is that all the graft you hope to get out of this?"

"It's all one man can carry!" answered Dick.

"And you expect to get a commission in the British Army by invading the territory of England's most important ally, at the exact moment when a setback to either of them would be most inconvenient?"

"If you put it that way, yes," smiled Dick.

"It's the wildest idea of blackmail I ever heard of! You're an original!"

THE rain streamed from Dick's hair down his face and shoulders, for he never would wear a hat, but he made no offer to move; and Jenison, smothered in a seaman's sou'wester and oilskins, was too absorbed in the study of him to know any longer whether it was raining or not.

"D'you mean to tell me," Jenison demanded, "that you cooked all this up—this rebellion, this expedition, all this business—for the sake of a commission in the British Army?"

Dick laughed at him.

"No," he said. "I left England with a commission in the Territorials. Couldn't get anything better because an uncle of mine took steps to prevent me. I ran into this affair by accident—to me; it was design on Russia's part. Never dreamed of a war in Europe; wouldn't have left home for a kingdom if I'd thought there was the remotest chance of it. Now, if there's anything can keep me from getting back to Europe with my man Andry I'd be interested to know what it is. When we've cleaned this tangle up I'll try for my commission."

"How?"

"Does it ever happen to you," said Dick, "in business, for instance, that you can see in your own mind how you're going to do a thing—exactly how everything is going to break—and yet you wouldn't trust yourself to put it into words?"

"Often," said Jenison.

"There you have it, then," said Dick, making a move to pass on.

So Jenison stepped aside into a puddle and stood in it to stare after Dick, who strode across camp like the god of war, indifferent to everything but the end he aimed at and its means.

"The fools ought to have kept him and made him join the army. They'd have won the war by now!" swore Jenison.

He went on his way then, over toward his mud-smeared guns, with a smile on his lips that was less mechanical, and the little crowd of English and Americans whom he had brought from Teheran detected the change in him, gathered around him, and teased him for information.

"All I know is that we start at midnight," he told them, then added, to the extent of his own scant information: "There'll be a small mounted advance-guard under Usbeg AH Khan. Then we follow with the guns and a spare team for each gun to help haul 'em.through the worst places; then the infantry, and a rear-guard of mounted men again. How much ammunition have we got, boys?"

"Ten rounds a gun," said somebody.

"Is that all?"

"Every ounce!"

"——!" said Jenison.

DICK passed the tent that had been given the Princess with a frown on his face that he could never quite refrain from at mere thought of her. What hurt him, strangely enough, was not her desperate villainy nor the months of misery that she had brought on him, but the fact that she made it impossible for him to respect her as he wanted to respect all women. His one weak point was his too punctilious chivalry. Even now, when she called to him from between the tent-flaps, he turned to listen to her and could find a smile of courtesy.

"Mr. Anthony!"

His smile grew sunnier, for of late she had always called him by his first name. He recalled her "I surrender" of an hour ago, and felt almost friendly.

"It is very cold and wet. I am only a woman, and I have been exposed to more rain than is good for me. Is there no brandy—perhaps even vodka—in the camp? May I have some, please? Otherwise, I don't think I will ever get to Teheran with your message!"

Across Dick's mind there flashed recollection of a wagon-load of vodka, part of the loot of the Russian camp, that he had ordered kept under rigid guard because he had use of his own for it.

He went to the wagon, made one of the sentries pull out a small cask of the stuff, and, because there was no sense in leaving a broached cask to tempt the men, carried the whole thing to the Princess' tent. It was marked on the outside in Russian "Alcohol 96%."

"Help yourself!" he smiled, rolling the small cask into her tent, and noticing as the flap fell back how meager were the comforts provided for her. She looked cold and miserable, and there was no bed in the tent at all.

He went off at once and ordered a Russian officer's cot-mattress taken to her, with half a dozen plundered Russian blankets. He had food sent to her. And because the close ring of sentries set by Usbeg Ali irked his sense of what was due a woman, he ordered them away and left only one to watch her.

Then he went off about the thousand and one different things that call for the attention of a man who would lead eight thousand on a raid. One of the first things was to have all the rest of the vodka spilled into whatever shallow receptacles were to be found, and every marching man of the force was made to file by and bathe his feet in it. Those who wanted to were allowed to rub it on their stomachs. Then came the turn of the horses, and what was left when their tired muscles had been rubbed with it was poured out in the mud.

The camp became like an ants' nest for activity; and when the rain ceased at last and the clean, sweet air called out the fighting-men from under cover to fill their lungs and stretch themselves, there was too much commotion and too much hilarity for minor things to be much noticed. Certainly nobody noticed a long slit in the back of the Princess' tent, and a finger that rose and fell up and down in what might have been unpremeditated sequence of short and long strokes.

Nobody noticed that the tent assigned to the Russian General, that was back to back to hers and a hundred yards away, had a slit in the back of it too, or that another finger did very much the same thing in that slit.

Nor did it seem to be anybody's business that the sentry on duty by the Princess' tent should go close to the fluttering flap and be given a cupful of strong vodka. True, he was a Mohammedan and not supposed to drink it. True, several saw him and as many envied him. But there is a schoolboy camaraderie among campaigners that forbids them to tell tales about less delinquencies than treason; and there is an easy equivocation current among the less strict Moslems that says "spirits are not wine." The Prophet forbade wine, but said nothing about vodka.

And vodka is generous stuff, when a man has not tasted spirits for a year or two. It warms up the cockles of his heart, lets out the reefs in his imagination, and makes him see logic that would otherwise seem treason to him.

The sentry loved Dick, as a good soldier may love and reverence his officer. The vodka told him to be like Dick, if he could. And Dick's chivalry—the lengths that Dick would go to oblige a woman—were a subject of everlasting fable and exaggeration among his men. A second helping of raw spirit, passed to him by a slim hand through the opening of the tent, opened the man's ears and made mere words sound like the whispering of angels.

"Would he take a message? In the name of Allah the Compassionate, why not?"

WITHIN five minutes the General was in possession of a scribbled note; and within five minutes more the Princess had her answer, scribbled across the lines of the same sheet of paper. Both messages were long, and detailed.

Then, would the sentry not be pleased to let a lady by? Had the sentry not been given vodka? Was the vodka not excellent? Would he like some more? Surely she would come back! She would come back within ten minutes. Yes, she could see Dick Anthony now, examining the captured Russian cattle; surely she would be back before he had finished; it would take him thirty minutes more at least to complete his inspection at that rate, and she would be back in less than fifteen. Meanwhile, here was a third cup of good vodka, and if the sentry would step aside for just one second—so—

She was gone—a veiled Persian woman slipping by the shadows in a camp where a woman of any kind was sacred. She had vodka—lots of it—in the gourd they had provided for her drinking-water, hidden under her long veil.

Luck, of the most amazing kind, seemed to shadow the Princess always in the inception of her plans and the beginning of their evolution. It was nothing less than luck that made Jenison relieve the guard on the wireless-wagon with another man who was half-stupid from being aroused from heavy sleep.

He had taken up his duty about five minutes before the Princess came, and was still wondering sleepily whether Jenison meant the talk about strong drink to be a joke. Where was the strong drink, anyhow? And if there were any, who would be the guy—the thirsty, thirsty guy—who got the first crack at it? Eh? And how much would there be left in that event for anybody else, unless there were an awful lot of booze?

His reflections were not interrupted, rather they were led gently on by the smell of strong drink, and at that a new smell that he did not know. And then from beside the wagon-wheel a cup was held out to him by a Persian woman, who said in very pretty broken English—

"Wid Meester Anthonee's compleemens."

Now, was not that thoughtful and decent of Dick? Who wouldn't fight to a finish for a commander who remembered the men on guard in that way? He reached for the cup, swallowed its contents, and allowed the veiled lady to fill it again. The second cup made him cough, and his head swam so that he did not ask for a third; he was satisfied to lean on his rifle and wonder at the world at large.

He did not watch to see which way the woman went, nor did he care which way; and he was not listening very carefully. He was thinking of Dick Anthony—wondering why he called himself "of Arran," and "No Name"— wondering what color Dick's amazing eyes were, and whether Dick was as strong physically as men said he was and as he seemed to be. He was wondering, too, what he would do if he had had Dick's personal charm and ability to make men follow him.

He was not thinking at all of the wagon behind him, and he was not quite sure how many people ought to be in it, anyhow. He knew it was a wireless-plant, and—oh yes, the fellow in charge of it must not drink—souse, most likely—pity some fellows would souse at the wrong time. Now he....

THROUGH the slit in the covered front of the wagon a slim hand, followed by the shapeliest arm the wireless-expert had ever seen, held out a cup of vodka—96%. It smelled like the back-room in a Bowery saloon, and for a moment the sleepy expert thought that he was dreaming. But the cup came forward, and the smell increased. He held out his hand and touched the cup—took it—swallowed the contents— coughed—gasped—and passed it back for more.

"Pinch me when it's over!" he said in a level voice. "But not until it's over!"

It was not without reason that Dick had hesitated when Jenison first came to him with an outfit of fifty men, half of them white. He had not doubted Jenison; he bad read him, understood him, liked him, trusted him, and shaken hands. It had been Jenison's following that gave him pause, and the very thoroughness of his subsequent precautions to keep the fifty-man contingent separate from the rest now helped the Princess. For nobody stopped to chat at the wagon, or to ask questions. Nobody saw the Persian woman climb up by a wheel and spring inside. Nobody heard the argument that followed.

"Gimme summore!"

"Send me a message first!"

"Uh-uh! Gimme summore, kid! Pass the bottle!"

"Give me a pencil and some paper. So. I will write a message—you will send it— then you shall have as much as you can drink."

"Pass the bottle here! Come on, I'm thirsty!"

"No. I will give you a little more—there—now—no, that is all! Now give me the pencil and paper—thank you!"

From somewhere under her Persian dress the Princess drew a little book that was identical with that taken by Dick from the General's belongings. Carefully, but with a speed that proved her long familiar with the code, she wrote out a message in a clear, bold hand.

"Send this," she said quietly.

"Gimme another drink, that's a good girl!"

"First send this."

"Send what? What is it? Send it where?"

"Call P-P-L. Keep on calling P-P-L."

Automatically almost, the man dispatched the signal-number that she gave "him, and from overhead the wires crackled that had been silent all afternoon.

Dick Anthony, passing up and down the horse-lines, heard the crackling and turned his head. Then it occurred to him that the man in the wagon must be acknowledging signals. He went on examining the horses, being satisfied that the wireless-expert would write down anything that came. But the crackling continued, at a growing pace, and Dick grew uneasy.

Presently he left the horses, and went striding across camp in a hurry. He had to pass the Princess' tent to reach the wireless-wagon. He saw the sentry leaning on his rifle half-asleep; he went near enough to smell the fellow's breath, and then he opened the tent-flap to find nobody inside. And still the wires up over the wagon crackled like burning thorns!

THE nearest man was the sentry. Dick seized him by the scruff of the neck and shook him until he dropped his rifle—until the cartridges fell out of his bandolier—until the world became to him a futurist affair of streaky parallels, without sense, purpose or stability—shook him until the fumes of vodka left the inside of his skull, and nothing much was left to him at all except desire to breathe and to obey.

"Go and get Jenison amelikani!" ordered Dick, giving the American the title bestowed on him by the Afghans of his command.

"Where?"

"Find him! Bring him!"

The man reached for his rifle, but Dick set his foot on it. The man reached for cartridges, to refill his bandolier, but Dick's attitude was eloquent and he started off toward the artillery lines just in the nick of time to avoid a kick that would have lifted him well forward on his journey. Dick picked up the rifle, beckoned a passing non-commissioned man, and ordered rifle and cartridges all taken to the guard-tent.

"When their owner comes to claim them," he ordered, "refuse him. Hand him over to the officer commanding the baggage-train, with orders to use him as a mule!"

"To hear is to obey!"

"It had better be!" said Dick.

Then Dick saw Jenison, and timed himself to meet the American exactly abreast of the wireless-wagon. The crackling had ceased, and a face that peered through an opening to see if all was clear, drawing back again as he approached.

"Hullo, Jenison!" he called.

"Hullo! What's new?"

"A change of plan, that's all. Sha'n't start for a few days—very likely three days, and perhaps four."

"But why? Man, why in thunder not?"

"Several reasons," Dick assured him, looking so gloomy and speaking so gloomily that Jenison stepped closer to get a better look at him. And yet Dick raised his voice.

"There's news of reinforcements coming on to join us from the rear, for one thing. Some reports say five thousand infantry—well worth waiting for. For another thing, the horses are badly done up—need a rest to be any good at all."

"Mine aren't," vowed Jenison. "The gun-teams are good for a hundred miles!"

"The guns can't go on alone," said Dick, speaking so distinctly that Jenison grew nervous and looked about him for fear they might be overheard. "And besides, the men won't march until they've had a rest and cut up the loot between them. I'm rather counting on the arrival of the reinforcements to put new ginger in them."

Jenison stared blankly, dropping his lower jaw a fraction of an inch, for this was not the Dick Anthony the Resolute, of whom he had heard when in Teheran, whom he had led fifty men to seek, under whom he had fought, and whom he had learned to admire more than any other mad on earth. This was an ordinary person speaking, some mere victim of circumstance and whim. He could have done better himself than sit down in a mud-puddle in the rain, to wait while the men changed their minds.

"Man, we're lost if we wait a day! We must move!"

"We'd be lost if we had a mutiny," said Dick.

"D'you mean—"

"Come to my tent, and I'll convince you!" Dick took Jenison and led him along.

WHILE they squelched through fifty or sixty yards of mud Dick strode in silence, never once looking to the right or left. Then, "What's that noise?" demanded Jenison. "News of my change of plan going to Baku! That's your wireless-expert sending a message for the Princess, saying that we'll wait here three or four days because the men won't march!"

"Nonsense!"

"Fact!" Dick assured him. "No, she isn't in her tent. I came from there. I gave her the vodka myself with which she bribed your man."

"On purpose to bribe him?"

"No. That part was unintentional. It was my oversight, so your man sha'n't be shot. Ah! Here's Usbeg Ali—Usbeg Ali, get a move on! We start in an hour, and sooner if you can!"

"Whither, bahadur?"

"Baku!"

The Afghan saluted.

"Go and get your guns away, Jenison!"

Jenison too saluted, and the act seemed to give him pleasure.

"Has the man gone to Teheran with the key of that box?" asked Dick.

"Surely," said Usbeg All.

"Then let me have that ten-man escort now, instead of tomorrow morning."

"In five minutes they shall be here, bahadur."

"Don't want 'em here! Send 'em to the wireless-wagon. Let 'em take the drunken man who's is there, and the Princess too if she's in there. If the Princess isn't in there, let 'em take her from her tent and escort both to Teheran together. Be sure that the Princess takes her steel box when she goes!"

"Is that all, bahadur?"

"That is all," said Sick. "Do that. Send word to the rear for the mounted men to close in and follow up—and then lead off. I'm going to bum whatever we can't take with us. The main thing is to hurry. Send Andry Macdougal to me if you see him anywhere. That's all, Usbeg AIL"

So the Afghan saluted, clicked his heels together, and was gone.

NO bugle or trumpet blew to herald Dick's start on a raid that was more daring than any in the greatest war in history. It was the blare of Andry's bagpipes, coaxing the half-drilled infantry into time and step, that set the pace and proclaimed the raid's true character.

Many and many a handful has won fame by holding a pass, or by fighting a good rear-guard action against ten times its number, just as many a nation has won infamy by swarming armed into the territory of a lesser power.

But it has not happened often, except when Scotland raided England, that the lesser—say eight thousand—has dared invade the greater. It was sheer, stark, laughing madness, and every man who sploshed through the mud behind Dick Anthony that afternoon in time to "The Campbells are Comin'" knew it—knew that Russia's millions lay over the border beyond, and that nothing less than genius could save them from utter destruction!

Not a man marched sadly. Not a man but believed Dick Anthony the one man in a million with brains and spunk enough to turn the trick. Even the wounded, left in a body at the first village and not overconfident of being fed, shouted encouragement until the last of the rear-guard rode by.

Even the trace-men, hauling beside the horses to help Jenison's guns along, hauled with a will and needed no urging. Night shut down on a muddy eight thousand that marched and marched and marched, and thought only of the goal ahead; on an Andry whose cheeks ached from the blowing; on an Usbeg Ali Khan five miles ahead, whose brown eyes pierced the gloom, with a screen of spaced-out scouts on either hand of him; and on a red-headed, bare-headed Dick who rode not at all like a man in a dream, but like a man who is conscious of his danger and entirely master of it.

The cold rain came down on them again, driving in torrents into their faces and burdening the infantry beneath the extra weight of wetted clothing. Yet, the mile-long columns laughed, tossing new jokes from company to company; for the Persian of the North is a stout, good man for all his rulers, his religion and his weaknesses, and Dick had called up the stoutness from its slumbering depths. Most of all they joked about the Princess Olga Karageorgovich, whom many of them had seen sent southward surrounded by ten men. They joked as the East does always, without what the West calls decency.

Dick, except when some ribaldry or other passed him wind-whipped from the gun-tails back to the squelching infantry, did not even spare a passing thought for any woman in the world—neither for Marie Mouquin, sitting propped upright by cushions in a wagon at the rear straining her ears to catch Andry's bagpipe-music, nor for Marie's former mistress.

BUT the Princess was thinking of both maid and Dick, when she was not storming at the Persian horsemen who escorted her at Dick's command. The horsemen were not at all in love with the notion of riding away from the scene of Dick's next operation, and she worked with a will and a forked tongue to make them less so; but tongue-work did not prevent her from thinking furiously. Speech with her never represented more than what she had thought; her true thoughts were ever secret to herself, unexpressed except in ceaseless watchfulness.

She laughed once or twice in memory of her "I surrender!" and of Dick's ready belief. Never, never, never would she surrender so long as she had breath, whatever mere words might be made to seem to say! She had set her tigress' heart on pick when she first set eyes on him and, ruined or triumphant, she would fight to own him while she had breath, if only for obstinacy's sake, and cunning's.

So she was in no mood to be hustled down to Teheran. When Dick determined first to send her there the idea had suited her finely, for she thought herself at the uttermost end of her resources. Protection from the British Government would have given her breathing space in which to plan new activity.

But communication with the Russian General and discovery of the wireless-plant had changed all that. She had been able to notify the Russian Government of the whereabouts of those most important, most incriminating plans; and that had shown her a less passive, therefore a more acceptable course to take.