RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

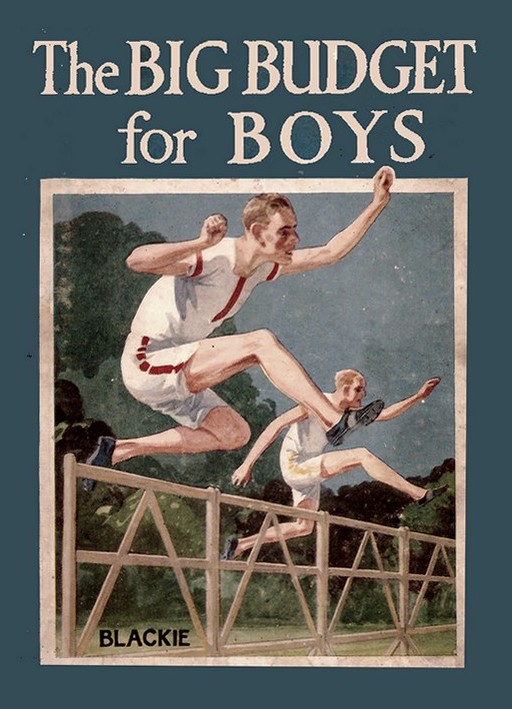

The Big Budget for Boys with "The Boastin' Fool"

The Desert Guide

ALL day the long train of covered wagons and mounted men had trailed across the vast spaces of the blazing Arizona desert, and now that the red-hot sun had dropped behind the rugged Pinnacle Range in the west they still dragged slowly onwards, hoping against hope to reach the spring of cool water under Smoky Butte. It was nearly dark when tall young Buck Taggart, who led the way, reined in his tired grey horse, and raised his hand as a sign to halt.

An elderly, hard-eyed man came pushing up alongside Buck. "You mean we got to make another dry camp, Taggart?" he demanded.

"Ain't nothing else to do, Mr. Breed," replied Buck quietly.

"You said as we'd reach the spring to-night," accused Breed.

"And so we would if we hadn't wasted so much time looking for James Sorley."

Breed frowned more heavily. "You mean we were to go on and leave one of our men to perish in this here desert?" he asked accusingly.

"I don't reckon James Sorley's the sort to do much perishing," returned Buck, with a ghost of a grin.

Breed grew angrier still. "We all know the way you felt about Sorley," he said significantly. "I reckon the elders'll have something to say to you afore we go much farther."

"Anything they like, and any time they like," said Buck, "but until they turns me out of my job I'm running this outfit, and I'll thank you to go help pitch camp, Mr. Breed."

Breed rode back muttering, and Buck, after dismounting and hobbling his horse, followed to give a hand to the Rundalls. George Rundall was ill, and all the work fell on his boy, Ted.

"Got any water, Ted?" asked Buck.

"Enough for a pot of coffee, Buck," replied Ted, "but there's some ain't got any at all, and they're mad as hornets because we ain't reached the spring."

"Blaming it on me?" suggested Buck.

"That's a fact," scowled Ted, who was devoted to Buck. "But they wouldn't if it wasn't for them two trouble-makers."

"Hardress and Rastall," said Buck, with a nod. "Yes, they're jealous as sin because the elders gave me the job of running the show. Hardress thinks he'd ought to have had it."

"Watch out!" whispered Ted. "Here he comes."

At that moment a man came up. He was about the same age as Buck or a little older, but very different in looks. "The elders wants you, Taggart," he said briefly.

"Tell 'em I'll be right along," replied Buck, and Hardress with a scowl moved off. Buck was following, but Ted caught him by the arm. "What do they want of you, Buck?" he asked anxiously.

"To dress me down a piece, I reckon," said Buck, with a slight smile. "Don't worry, Ted. I'll be back right soon, and here's my canteen. Give your dad a little extra water."

The elders, four of them, stood a little apart from the rest. Breed was one of them, the others were Dane, Torrance, and Lovell. They were the leaders of the expedition which had come out of Missouri with the object of settling up grazing lands in Western Arizona.

Buck walked up and waited for them to speak. Old Sam Torrance began. "Taggart, when we picked you to guide this here party you told us as you knowed the trail."

"Wal, I ain't lost it," replied Buck.

"I hear you say so, but looks to me like you were as bad lost as the rest of us."

Buck took the war into the enemy's camp. "You mean that's what Hardress has been telling you?"

Breed broke in. "If Hardress had been leading us we wouldn't be dying of thirst in this here desert," he snapped.

"No, for your scalps would have been hanging on the lodge poles of the Apache up in them hills there," retorted Buck, pointing to the dark mountain on the southern horizon. "This here's the only safe trail so far as Injuns is concerned, and as I told you already, we wouldn't have had to camp dry if you hadn't wasted all that time this morning a-looking for Sorley."

The four old men stood frowning at the young one. "I reckon," said Sam Torrance, "that if we'd knowed as much about you afore we started as we do now, we'd have chose someone else to run this outfit."

Buck stood and faced them. "Choose someone else right now, if you want to," he answered. "I ain't asking any favours."

The four stepped aside and talked for a while in low voices, then Torrance spoke to Buck. "We aim to be fair," he said. "We'll give you another day to make good. If you gets us out of this desert to-morrow then you kin carry on; if you don't, then we'll pick someone else."

Buck bit his lip to keep back the hot words. "That'll be all right," he said briefly, and went straight back to the Rundalls' wagon.

"What did they say to you?" was Ted's first eager question.

"Not a lot, but it was mighty well to the point, Ted. They're decorating me with the order of the boot if we ain't out of the desert this time to-morrow."

"It's a shame, a gosh awful shame," exclaimed Ted passionately. "You've brought us all safe this far, and just because we've got a bit of desert to cross they're raising all this Cain. Buck, will they pay you if they put Hardress in your place?"

"No, son, the bargain was a thousand dollars if I got 'em through. There wasn't no talk of money till the job was done."

"It ain't fair," cried Ted.

Buck shrugged. "Maybe they ain't done with me yet, Ted."

"What do you mean, Buck?"

"Jest this," said Buck in a low voice. "Ef nothing don't go wrong I reckon we'll be at Paradise Gap by to-morrow night."

"Out of the desert?"

"Pretty nigh. Anyways, there's good feed and water there."

"Then nothing shall go wrong," vowed Ted.

"I ain't so sure about that," replied Buck. "We ain't a-going to get there ef Hardress and Rastall have got any say. It was them hung me up this morning, and I reckon they'll do it again ef they're able." Ted was bursting out again, but Buck checked him. "Let's eat supper and sleep. We got to start mighty early to-morrow."

NEXT morning Buck was up an hour before dawn, and with tremendous energy driving the laggards to hitch up and move. He got scowls and black looks on every side, for the people had spent a wretched night of thirst and discomfort, and Hardress and Rastall had been whispering that it was all Buck Taggart's fault. Buck's heart was sore, but he did not show it. "Rouse out!" he kept on crying. "Get to it. It's only ten miles to water."

By sunrise the long string of wagons was moving slowly forward. Dust rose in clouds fine as flour, settling thick on everything, choking throats and eyes. Children were crying with thirst, and the horses were so done they could only move at a slow walk. As the sun climbed the sky the heat became terrific, the sand burned the feet, and the glare blinded the eyes of the travellers. Mirages danced along the skyline so that it was hard to say what was real and what not. Hotter and hotter it grew, but Buck kept his place in the lead. His sun-blackened face was hard and grim, and now and then he licked his dry lips with an almost equally dry tongue. He had given all his remaining water to the Rundalls. As they topped a rise he saw a hill ahead, and knew it for Smoky Butte, and he prayed silently that the spring was still running.

His prayer was granted. The spring still flowed, but he had to fight desperately to keep men and beasts from crowding in on the little pool and fouling it. Others helped, and in less than an hour canteens were filled, everyone had drunk, and each of the horses had slaked its thirst.

By midday he had the outfit moving again. Less than a dozen miles ahead he saw the mouth of the canyon through which he meant to bring his party out of the desert, and a glow of triumph ran through his veins as he realized that, after all, he was going to win out. But there was no sign of that triumph on his face as he rode slowly at the head of the long string of creaking wagons.

The heat was terrific, the distant hills danced in a whitish haze, the blazing air felt like liquid flame as he drew it into his lungs. So hour by hour the terrible afternoon dragged by, yet always the hills came nearer, and the gap more plain until, an hour before sunset, the canyon mouth was less than a mile away.

Suddenly Buck heard someone call out sharply, and turning noticed that Rastall, who was a smaller, skinnier edition of Hardress, had pulled up and was pointing up the gorge. Then Breed shouted and beckoned, and as the whole party came to a halt, Buck rode back.

Breed's face was dark with fear and anger. "You said you'd took us this way to keep clear o' Injuns, Taggart. What do you make of that?" He handed a spy-glass to Buck, and pointed up the gorge.

Buck focused the glass, and it showed him two things, first a ring of smoke rising slowly into the quiet air far up the canyon, then the plumed headdress of an Indian brave, showing against the skyline on the left-hand rim of the gorge.

"A pretty mess you've made of it," Breed stormed, "Smoke signals and them red devils waiting for us. Now what do ye reckon to do?"

Everyone was terrified. Men who would have faced a forest fire or a desert storm unmoved were pale and shaking. In those days, fifty years ago, the Red Indian was the terror of the West, and fearful tales were told of prisoners tied to the stake and tortured for hours before merciful death relieved their sufferings.

Of them all Buck himself seemed the least troubled, yet his young face had gone very hard and grim. He lowered the glass and turned to Breed. "I reckon if I've run ye into trouble it's up to me to get ye out. Ef you'll wait right here I'll go along and scout."

Breed's eyes widened and Hardress who was standing near by sneered openly.

"Boastin' fool!" Buck heard him say, and turning, stepped towards the man. "Boasting, you reckon, Hardress. Mebbe I am, mebbe not. Anyways, I'm going to do what I said." He walked back to his horse, took his rifle from its scabbard, opened the lock and saw that it was properly loaded, then swung himself into the saddle.

Ted Rundall came running up. "Take me with you, Buck," he begged, but Buck shook his head. "You stay and take care o' your daddy," he said gently. "And don't worry too much about me, Ted. I've fought Injuns afore this." Then he rode away.

"Plumb crazy," said old Breed angrily, but Lovell, who stood by, shook his head. "He's a man anyways," he answered. "No one can't say nothing else than that." Silence settled on the whole party, and they stood watching the lone figure advancing towards the gorge.

Near the mouth Buck dismounted, and leading his horse in between a great boulder and the cliff, tethered him. Then, carrying his rifle, he went on afoot. He had just one thing in his favour—that he knew the ground.

The gorge bit right through the mountains with walls of brilliant red rock towering upwards on either side, and the bottom strewn with giant boulders fallen from above. Buck vanished among these boulders, but he did not stay among them long. Slipping into a little side canyon he began a nerve-testing climb up the almost perpendicular wall. Crawling up deep cracks, forcing his way with knees and elbows up narrow chimneys, now and then resting a moment on some narrow ledge, he worked his way steadily towards the lofty ridge above. Sweat streamed from his body, and his breath whistled in his lungs when at last he gained a ledge just under the rim.

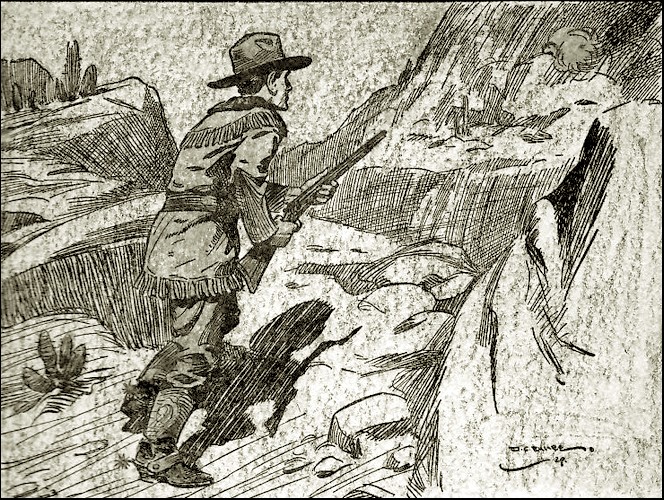

He was now on the opposite side from that on which he had glimpsed the Indian headdress, but the chances were that the Indians were on both sides. Very slowly he raised his head and peered over the rim, but he could not see far, for the top of the mesa was a mass of broken rock weathered into a thousand strange shapes by the sun and storms of centuries. He pulled himself over the ledge and began working his way over to the edge of the main canyon. His object was not to fight the Indians, but to see how many there were, and who they were, and what were the chances, if any, of finding a way round without taking the party through the pass below. Sometimes bent double, sometimes on hands and knees, he at last gained his objective and, sheltered behind a tall pinnacle, lay flat, exploring with his eyes the opposite ridge.

The first thing he saw was the top of that feathered headdress just showing above a rock about a hundred yards farther up on the opposite side. It seemed to be in exactly the same position as when he had first seen it; but knowing the deadly patience of the Indian he felt no surprise. Buck wanted to know whether the red man was an Apache or not, and whether he had companions, and with that idea started crawling along the mesa, keeping as much under cover as possible.

He had reached a point nearly opposite the Indian when the sharp crack of a rifle came from the opposite ridge, and a bullet whined overhead.

A bullet whined overhead.

Buck leaped for cover behind a boulder, and spotted a little cloud of smoke rising opposite. It came from the very rock where he could still see the headdress, but what puzzled him was that the head had not moved. He thought it over for a few moments, then crawling like a lizard made right back from the edge and when he could get cover pushed straight ahead.

None knew better than he the risk he was taking. At any moment he might run into a whole bunch of the scalp-hunting red demons; and if he did so his end was certain—and horrible. But he had what he would have called a hunch that he was doing the right thing, and the farther he went the more certain be became. He saw no sign of life except lizards and rattle-snakes, and presently came round in a curve back to the rim of the pass.

He found himself a good way beyond the rock from which he had been fired at, so that he was able to see the back of it, and what he saw brought a grim smile to his lips. Levelling his rifle, he fired, and the feathered headdress vanished. Instantly his shot was answered. He saw the barrel of the rifle from which it came lying across a flat slab of rock. The hidden rifleman was a good shot, for his bullet smacked on the rock which sheltered Buck, and fragments of lead spattered in every direction, one cutting Buck's cheek and making it bleed.

Quick as a flash Buck gave a loud scream, half rose to his feet and fell backwards. "That ought to fetch him," said Buck, smiling to himself as he wriggled away and found fresh cover at a little distance. Then he lay and waited, meantime reloading his rifle.

A long time passed, the light began to fail, and Buck grew worried. If the rifleman failed to show himself, his whole plan was a failure. But at last he saw a movement. A man rose very cautiously from behind the flat slab.

Quick as a flash Buck was on his feet, rifle levelled. "Put up your hands!" he shouted.

Instead, the other swung round and fired.

But Buck's rifle spoke first, and he saw the other man spin round and topple over. Buck waited, but the body fell limp on the bare rock. "He asked for it," said Buck, with a shrug, and started back.

Stars hung like jewels in the vast dome of the sky when Buck reached camp. Men hurried out to meet him, among them the elders themselves. All stared at Buck as they might at one who had risen from the dead. "Them Injuns didn't get ye, Taggart?" exclaimed Breed.

"There weren't no Injuns," was Buck's quiet reply.

"You're crazy," retorted Breed. "I seed one myself."

"You saw some feathers," corrected Buck. "You didn't see no Injun."

Breed was too astonished to speak. It was old Lovell who asked the next question. "Someone playing a game, eh, Buck?"

"That's right, Mr. Lovell," said Buck gently. "It were jest a trick fixed up to scare us."

"Sorley?" questioned Lovell.

"You got it, Mister. It were Sorley."

"He up there now?" asked Lovell.

"He's dead," was Buck's answer.

Lovell turned to the other three elders. "I guess we all understand now," he said quietly.

Breed scowled, but Torrance nodded. "I guess we do, and it's my notion we been doing Taggart an injustice. What you say, Dane?"

Dane, a little quiet old man, agreed. "I reckon we got something to say to Hardress and Rastall," he remarked curtly.

Ted Rundall, who had been listening eagerly, spoke. "They're gone, Mr. Dane. They rode off half an hour ago." The boy came up to Buck and caught his hand. "I knowed you'd win through, Buck," he said joyfully.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.