RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

A Powerful Story of the Stage, introducing Sexton Blake and Tinker.

The Death at the Theatre — Tinker Warns Sexton Blake —

The Marquis on the War Path — The Wooden Match.

THE rehearsal of the new play, "The Love Light," was just over. The actors and actresses gathered up their brown-paper-covered books, containing their parts, and hurried away home, or in search of a well-earned meal.

Sexton Blake rose from his chair in the prompt entrance, and walked to the centre of the stage to congratulate his old friend Aston Revelle, the author.

"You've got a winner here, I think, Revelle," he said. "That last act is prime!"

"Thanks, Blake," replied Revelle, a handsome, middle-aged man. "Come along up to the club and have some lunch."

The two friends picked their way through the pile of scenery, and were soon at the stage door.

"Have a cigarette?" asked Revelle, holding out his case.

"No, thanks, old man," answered Blake. "I don't smoke before lunch."

"Well, I'll just have a whiff." Revelle put a cigarette to his month and felt in his pocket. As he pulled out a cheap wooden box of German matches Blake grinned.

"Not a very extravagant box for a prosperous author," he said.

"I suppose I picked them up somewhere, and shoved them into my pocket," answered Revelle. "Anyway, if they'll light they'll do."

He struck a match and applied it to his cigarette.

He had barely inhaled a mouthful of smoke when he staggered and clutched at the detective's arm.

"What is it, old man?" asked Blake, supporting him. "Do you feel bad?"

"I feel as if I would—"

Revelle never completed the sentence. He sank into Blake's arms, his head dropped on to his shoulder, and with a sigh and a groan he slipped to the ground.

Blake tried to lift him up, but the dead weight told him that it was useless.

Quickly he undid the prostrate man's collar and shirt, and felt his heart. Then, with a white face, he stooped and put his ear to the bared chest. In a second he looked up gravely at the little crowd which had quickly gathered, and shook his head.

Aston Revelle was dead!

"Whats the matter? Whatever's up?" said a short, fat, clean-shaved man of about forty, pushing his way to the front.

Blake looked up.

"Send for a doctor, Mr. Merrivale, will you?" he asked. "He's gone, poor chap! Help me to carry him inside."

Max Merrivale, the principal comedian of the Monument Theatre, despatched a messenger, and then, with Blake, superintended the removal of the body to the green-room.

As he helped to lift poor Revelle, Blake, with a quick deft movement, swept his hand over the pavement and transferred something to his pocket.

The doctor was quickly on the scene, and at once pronounced that life was extinct.

"Terrible—terrible, isn't it?" said Merrivale, the tears standing in his eyes. "Poor Revelle! He was such a good fellow, too! A pal of mine for years, and to think he's gone like this! What does the doctor think, Mr. Blake?"

"Heart," replied Blake. "See you at the inquest, I suppose, Mr. Merrivale?"

"Yes, yes," said the comedian, "Poor old Revelle! It is hard luck!"

And, with a last look at their dead friend, they left the room.

When Blake reached his rooms in Baker Street, he found a small and very dirty boy seated on the doorstep.

With his head bowed in thought, the detective nearly fell over the little chap, and spoke rather hastily:

"You must get away from here, my lad, please!"

The boy looked up, and spoke pleadingly:

"I ain't doing any harm, sir."

"Come on; off you go!' said Blake, taking him by the collar.

"All right, sir, I'm a-going. Look out," he added, in a low voice; "the Marquis is upstairs, and I think he means mischief. He had a bulge in his back pocket. I thought I'd better stop and warn you."

Sexton Blake was never taken aback, and while the boy was whispering he kept on urging him to the edge of the pavement.

"Now mind." went on the detective, in a loud voice, "if I catch you loitering round here again I'll lock you up—mind that? Well, there's a sixpence for you, and come up in half an hour's time, Tinker," he answered in a whisper.

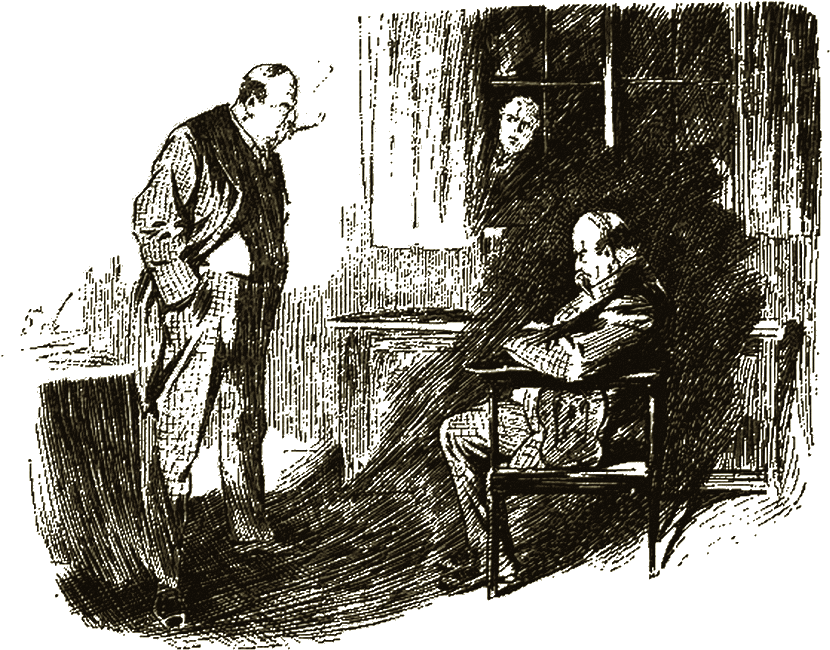

The boy shuffled off and Blake went up to his rooms. In a chair in front of the fire was seated an immaculately dressed, clean-shaved man, with an almost square face, and a thin, rat-trap of a mouth. As Blake entered he rose and smiled, showing an even set of dazzling white teeth.

"Sit down, Marquis, sit down," said Blake. "There's no need of ceremony between old friends."

"Ah, Mr. Blake! replied the other. "Always cool, always on the spot."

"Never mind about compliments. What do you want, Marquis? Quick, I'm busy!"

"Are we speaking straight, and without prejudice, as the lawyers say?"

"Not at all," said Blake, taking the opposite chair. "Whatever you tell me I shall endeavour to make use of."

"Wonderful man—wonderful man!" said the Marquis, in tones of admiration, "Can't get over him anyhow. But look here, Mr. Blake," he went on, with an air of unconcern, "let bygones be bygones. You got me five years once, and as it was all in the way of your business I suppose I ought not to grumble. But now, look here"-he drew his chair up closer, "I'm on a big thing—so big that you wouldn't believe me if I told you who was in it. Name your price to leave me alone—not to know me whenever you see me, If it rises to thousands you can have it, and you can have the money tonight. Come, what do you say to ten, fifteen, twenty-"

Blake gave a little laugh, and threw a cushion playfully at the Marquis.

"Go away with you, Marquis," he said. "What have you been drinking, to come to me with a tale like that? I thought there was something; you've been so deuced quiet lately. Much obliged for the tip, though, Marquis, I'll keep my eye on you now. Run away, there's a good fellow, unless you'll have a whiskey-and-soda first."

He turned to the sideboard, which was just at the back. As he filled up the whisky with the soda, he looked in the mirror which hung on the wall. Quick as lightning he flung the contents of the glass over his shoulder, right into the Marquis's face. Then, with a twist and a bound, he leaped round, and, with a grip of steel, pinned the man's wrists with one hand, while with the other he secured a small revolver which had been dropped when the whisky-and-soda took effect.

"Stupid of you, Marquis," said Blake. "I should never turn my back to you unless I could see what you were doing. Trying to shoot your old friend, too!"

The Marquis tried to wink the whisky-and-soda out of his eyes, and spoke grimly.

"Let me go now, Sexton Blake." he said, "unless you'll give me in charge."

"Not me," replied Blake, slipping the revolver in his pocket, "There is that little scheme of yours that promises to be worth looking after."

"By Heaven, don't you touch it, Blake," said the Marquis, "or you'll find yourself up against something too big even for you. Better take the fifteen—"

"Out of it," snapped Blake, "or I may change my mind, and have you locked up."

The Marquis went to the door and made a final effort.

"I should even spring twenty-five thousand-"

Blake took two strides, and gripped the Marquis by the collar, led him to the door, and gently pushed him into the street.

"You needn't call again, Marquis, thank you! What is it boy—got a message for me? All right; come upstairs."

As the Marquis walked hastily away, Blake returned to the room, followed by a district messenger boy.

"Very good, Tinker!" said the detective, when they were safely inside, "You are doing well. I think, by the way, that you saved my life this afternoon, and we don't forget these things."

Tinker's eyes glistened.

"It's a treat to be able to do something for you, sir."

"Well, the boot's on the other leg this time. Now report."

Tinker made his report. With his various disguises he had watched a well-known criminal, who was supposed to be responsible for the theft of the Great Mysore Diamond.

"That's all right, then," said Blake. "He's got it, that's clear. Scotland Yard can have that little picking. They'll only have to make the arrest, and the credit's theirs. Now, Tinker, just look up the Marquis, will you, and see if he was ever on the stage."

Tinker went to the safe, and took out a large, leather-bound book. Turning to a leaf, he read out: "Alistair Rortrey, alias Jem Smithers, alias the Marquis. Educated Eton; Trinity College, Cambridge. First went Army 1886. King of the gentlemanly 'crooks,' ever since-"

"Never mind about that," interrupted Blake. "I'll fill in details."

"Yes, here we are," said Tinker. "'Was on the stage for two years, from 1890. Good actor, but never made much money at it.'"

"That'll do, Tinker; we know all the rest, I think we are in for a very big thing. You can get off that uniform now, and be sure and take it back to old Lazarus. I expect he'll want it in a day or two."

When Tinker had changed into his ordinary clothes, Blake told him to sit down and listen.

He then related the facts of the death of Aston Revelle.

"And now, Tinker," he said, "this is where I take up my duty in all sincerity. Poor Revelle was one of the greatest friends I had in the world; and I have sworn to track his murderer. I accept no commission till my task is done. Are you with me, Tinker?"

"Through thick and thin, sir! And what have you got to start on?"

Sexton Blake opened his hand, and displayed a cigarette, which had hardly been lit, and a charred, wooden match.

Tinker Drives a Cab — The Poison Test —

Behind the Scenes — The Iron Rod.

SEXTON BLAKE was called as a witness two days later at the inquest on Aston Revelle. By means of his experience with the coroner, his full name and profession were not disclosed. In fact, no one, not even the members of the theatrical company, knew that he was the celebrated detective. When he stepped down, after stating briefly and clearly what he had seen, Max Merrivale stepped into the witness-box.

The comedian quite broke down when he was giving his evidence. He stated, with tears in his eyes, that the author had been a great friend of his for the last twenty years, and that he had once or twice complained to him of a weak heart.

That proved the doctor, who gave it as his authoritative opinion that heart disease was the cause of death, and a verdict was rendered accordingLy.

Sexton Blake knitted his brows and compressed his lips when the jury made their verdict, and walked slowly out of the court.

"Mr. Blake—Mr. Blake!" said Merrivale, hurrying after him. "Won't you come up and see me at the theatre tonight? I would like to have a chat with you about our poor friend Revelle."

"Certainly!" replied Blake, "Where are you to be found?"

"I shall be up at the theatre. We are still rehearsing, though I don't suppose the play will be produced for another fortnight. We must honour the poor chap's memory.

With a promise to call, Blake made his way to the corner of the street. Lifting his stick, he hailed a cab driven by a young-looking driver.

"No. 96, Rider Street, Portman Square." he said.

The cab clattered off, and when they had reached a quiet street Blake pushed up the trap.

"Any news, Tinker?" he asked.

"Yes, sir," said Tinker, who was the driver, speaking down. "I picked up the Marquis in Piccadilly, and drove him to Waterloo at half-past nine. He had a foreign-looking man with him."

"All right; drive on."

At that moment a newsboy rushed across the street, and, as it seemed, deliberately flapped the contents bill in the horse's face.

The startled animal tried to rear, and was brought down with a smart cut from Tinker's whip. Then it took the bit between its teeth and bore down the Strand.

Sexton Blake sat inside, grimly waiting to be pitched out. But Tinker wound the reins twice round his wrist, and by wonderful luck and skill guided the horse through the traffic, and finally cooled him down just outside Charing Cross Station.

In a few minutes they were safely at 96, Rider Street.

Blake jumped out, and appeared to argue with his cabman.

"Got any change, cabby? Get back to Baker Street, Tinker. That was one of the Marquis's boys; I saw his face. Why, the fare's only a shilling, I know. Take care how you go, there's danger. Well, there's eighteen pence, and not a penny more. There's a cab behind. You lose it."

He handed up eighteen pence and walked off, while Tinker, grumbling, drove away, pursued by the cab which had been loitering at the corner of the street.

Blake knocked at the door of 96, Rider Street, and it was opened by a stout, middle-aged woman.

"Well, Mr. Blake!" she cried.

"All right, Mrs. Medlicott," said Mr. Blake; "the old game. Anyone in the dining-room?"

"Not a soul, sir."

Blake looked in the dining-room and dropped to the floor.

"Quick, Mrs. Medlicott," he added, "stand at the window and pretend to be reading a paper."

The woman did as she was told, and Blake crept up and cautiously peeped out of the window, with his head just on the level of the sill.

"See that hawker over there, Mrs. Medlicott," he asked. "What's he doing?"

"Keeping his eye on the house, sir."

"All right; you can come away now."

As Mrs. Medlicott turned away Blake stood up and showed himself at the window. As he did this the hawker moved off, quickly.

"Now, then, Mrs. Medlicott," went on the detective, "I know your pluck of old. It's going to be tried still more tonight. In about half an hour I shouldn't be surprised if a gentleman calls and asks for a bedroom. Give him one on the second floor, and if he asks who has the next, describe me exactly, and say that my name's Bland; then telephone to Tinker at Baker Street, and wait up till I come."

"Very good, sir," said Mrs. Medlicott, who was the widow of an ex-policeman, and had been in Sexton Blake's secret-service for years.

Blake meanwhile slipped into the adjoining room where he remained for about five minutes. Then there appeared a well-set-up, military looking man, with an iron-grey moustache and a slight limp.

He opened the street door, and as he hobbled down the steps the hawker hurried back and took up his stand opposite the house again.

Blake limped down the road, bought a box of matches, and then walked slowly down the square. He stopped at a large house and knocked.

"Professor Alwyn at home?" he asked.

"Yes, sir," replied the servant; "but he can't see anyone, I know."

"Will you kindly say that Major Bee has called, and it's on urgent business."

The servant returned in a few minutes to say that the professor could spare five minutes.

As Blake entered a study on the ground floor a middle-aged man stood up and bowed stiffly.

"I am not in the habit of seeing strangers in the afternoon," he said politely, "but the servant told me it was urgent."

Blake looked to see if the door was closed, and then strode up to the professor.

"It's Blake, old man," he whispered. "Can't stop long. I'm on a big thing—I don't know how big it is yet—and I have my own private affairs, too. Analyse these for me, there's a good fellow, as quick as you can!"

He handed over the cigarette and the match as he spoke, and sank into a chair.

"There's no knowing where you'll pop up from, Blake, said the professor, "But why keep up that military voice? You're safe here.

"Not so sure," said Blake, "The Marquis is on the warpath, and there's no knowing where his people are. I have had one narrow squeak to-day.

While Blake was telling of his adventure in the cab the professor, with acids and testing tubes, was busy with the cigarette.

Finally he threw it over to Blake.

"Simply an Egyptian cigarette," he said; "nothing wrong about that."

"Mind trying the match?" asked Blake.

As the professor applied the test tube his face grew grave. At length he put down the pipes and turned to his shelf. Taking down a book, he read eagerly, and then tested the match again.

"Where did you get this from?" he asked.

Blake briefly explained.

"Then," said the professor, "if ever a man was murdered Aston Revelle was. This match has been steeped in a deadly Indian poison, hardly known in England. There, smell it!

The professor lit the match very carefully, and held it for one brief second under Blake's nose. It had a peculiar and pungent flavour which was unmistakably unique.

"One whiff of this drawn into the cigarette goes straight to the heart, and death will inevitably result. It killed your poor friend immediately. Now, can you find the murderer?"

Blake sat silent for a few seconds, in deep thought.

"No," he said, "no; not yet. But I will. Keep the match, professor. It wouldn't be safe with me."

Outside the house, Blake hailed a cab and drove to the Criterion, There he paid off the man, and as he walked through the building he whipped off the moustache and wig and emerged without the trace of a limp. Turning into a public call office he rang up Tinker at Baker Street.

"That you, Tinker. Get home all right?"

"Yes, thank you, sir."

"Good! No knowing when I may be home. If anybody rings up, say that I am stopping at a friend's for the night—No. 96, Rider Street. Don't forget to give the number, Good-bye!"

Blake rang off, and, after lunch, spent the afternoon quietly playing chess—his favourite recreation—at Simpson's in the Strand.

Toward evening he walked up to the Monument Theatre, where poor Revelle had met with his death.

Asking for Mr. Merrivale, he sent in his card, and the comedian soon hurried out.

"So glad to sea you, Mr. Blake!" he said. "We're just in the middle of an act; but I'll be through directly, and then we'll have a chat.

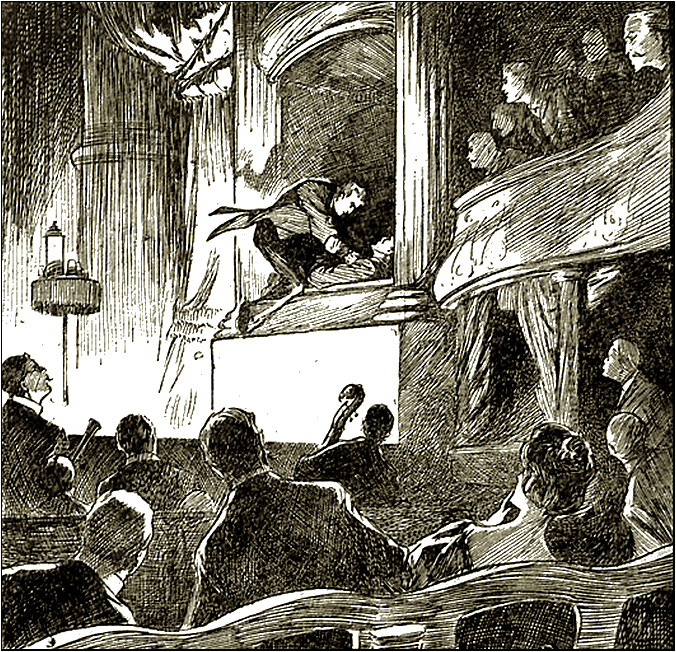

Blake passed through to the stage. To the uninitiated there is always an interest in the world behind the scenes.

The footlights were full on, but the rest of the house was almost in darkness. In the stalls sat the manager and a few friends, and instead of the full orchestra there was only one sickly looking man at the piano.

There was no scenery yet, and the stage looked bare and uninviting, as the performers went through their parts somewhat listlessly.

"Take a seat at the side, will you, Mr. Blake?" said Merrivale. "Joyce," he called to the prompter, "this is my friend, Mr. Sheldon Blake. Look after him, will you?"

(Sheldon Blake was the name the detective assumed when not on business.)

The prompter pushed a chair forward, and Blake was just about to sit down.

Almost by instinct, it seemed to him afterwards, Blake hesitated for a second.

Something passed before his face, and fell with a heavy thud and bang on the stage.

Blake stooped and looked. It was a heavy rod of iron, known as a "stay," used in the support of scenery. Had the detective been seated the rod would have fallen on his head, and in all probability have killed him.

Everyone looked round, and the prompter was furious.

"Hi, you, Rogers; up there! What the deuce are you doing? Come down here at once."

Rogers, a morose-looking man, slowly climbed down the ladder from the flies and stood looking rather foolish.

"Beg pardon, sir," he said. "I 'ope the gentleman ain't 'urt?"

"No, that's all right," said Blake, looking intently at the man, "Perhaps he didn't know I was underneath."

"Very careless of you, Rogers," growled the prompter, "See that it doesn't happen again."

"By the way," asked Blake, when the man had gone, "do you usually keep these things up in the flies, as I think you call the upper regions?"

"Certainly not," announced the prompter, "and I don't think what on earth Rogers was doing with it up there."

Blake smiled grimly to himself, and turned to watch the rehearsal.

Max Merrivale — The Midnight Thief —

The Marquis's Spy — Tinker on the Trail.

THE second act was well under way. Max Merrivale was stage-managing as well as playing a comedy part, and was here, there, and everywhere.

"Going well, isn't it?" he asked Blake in an interval. "How poor, dear old Revelle would have enjoyed this!"

"Yes, poor fellow!" said Blake. "But I think you are taking his place very well, Mr. Merrivale."

"Ah," sighed Merrivale, "I would like to make the dear boy's last play a success! Now then, ladies and gentlemen, the last act, please!"

The third act was begun, and then there was a sudden pause.

"Where's St. John?" cried Merrivale.

Call-boy, prompter—everyone shrieked and hunted for St. John, but in vain.

"That's annoying!" said Merrivale, "I wonder where the deuce he can be? I say, Mr. Blake, I wonder whether you would mind taking the book and reading the part. The other characters can then get on with theirs, and we shall know what we are doing."

Blake readily assented, and took the book. The part that would have been played by the missing St. John was an important one. There were several long speeches to deliver, and a touch of pathos was necessary.

"Just run through the lines, that's all," said Merrivale. "It'll help us along."

Blake felt a queer little sensation when he started to read the lines written by his dead friend; but as he entered into the spirit of the part he forgot everything, and rattled off the stirring words with a rigour and dash that surprised the professional members of the company.

"You ought to have been on the stage, Mr. Blake," said a pretty girl when the rehearsal was over.

"You almost tempt me," said Mr. Blake, with a bow.

"Now then, come into my room and have a jaw," said Merrivale cheerily, taking Blake by the arm, and leading him into a little room, half office and half dressing-room.

The table was covered with a clean white cloth, on which were scattered paints, powder-puff, and all the appliances of an actor's profession. A full-length mirror was let into the wall, and over the table hung a full-length portrait of Revelle.

"Poor fellow!" said Merrivale, mixing a couple of whiskies-and-sodas. "We shall never look upon his like again!"

"No, he was a good friend indeed," replied Blake.

"Twenty years I knew him," went on Merrivale, "and never a cross word did we have. And what do you think? He made his will only two days before he died, and left me his interest in the play. If it's a success I may draw anything from ten to twenty thousand pounds as my share."

"Generosity indeed!" murmured Blake, looking up at the photograph.

The two men sat silent for a moment, as if thinking of their dead friend.

Merrivale was the first to speak.

"Have you ever been on the stage, Mr. Blake?" he asked.

"Me? No. Why?"

"Well, I have been thinking—that ass St. John has forfeited his engagement by leaving the theatre before the rehearsal is over, and I believe really that you would play the part better than he would. Would you care to take it home and look over the other two acts, and rehearse them tomorrow? If you fancy it, I'll put you up to the tricks of the trade. You are just the height and build, too. And wouldn't old Revelle have liked you to be in it, too! We'll give you ten pounds a week if you take it on."

Mr. Blake held out his hand.

"Give me the part," he said, "I'll play it."

"Good! Now I'll give you a few tips."

Blake sat, and while Merrivale told him how to pitch his voice, and where to make the emphasis and where to leave it out, and the many little things that go to make the successful reading of a part, as it is professionally termed.

"Well," said Blake, when he rose to go, "you'll make an actor out of me, after all, I believe."

"Sure of it," said Merrivale, "You've got the face, you've got the will, and you've got the intelligence. Good-night! Rehearsal at eleven tomorrow."

It was about twelve o'clock when Blake returned to Rider Street. As he opened the door, Mrs. Medlicott came into the hall.

"Good-evening, sir!" she said cheerily. "You're home early."

And the good lady actually winked.

"Yes. Beastly night, isn't it? Any supper?"

"In the dining-room, sir."

Mrs. Medlicott bustled in and out, and each time she delivered some information in a whisper. Her conversation ran something like this, while she attended to the table:

"About four o'clock. A tall, good-looking man-wanted a bedroom for a week. Gave him one on the second floor next to yours. Asked if the house was quiet. Let him pump me as to who slept next to him. Got me to describe you fully. "That's him at the door, I think—"

"If there's any noise about two o'clock, don't be alarmed, Mrs. Medlicott. Now you get off!"

Blake heard Mrs. Medlicott say good-night to someone in the hall; then masculine feet ascended the stairs, and the house was as quiet as the grave.

Blake finished a cigarette, and then, in his turn, went up to bed.

On the second floor he smiled as he passed the door next to his own, and then, turning into his, lit the gas.

He took off his boots noisily, and made every preparation for bed.

Putting on his pyjamas, he turned down the bed, and placed his coat and vest inside, so that they looked as if someone were sleeping there. Then he unlocked his little travelling-bag, took out a couple of articles, and slipped inside a big cupboard in the wall.

As he crouched and waited he heard the clocks strike quarter after quarter, hour after hour. In his cramped and strained position, it seemed as if eternity were passing.

At length he heard two o'clock strike.

He shifted his position ever so slightly, and applied his ear to a crack in the cupboard.

Creak! creak! went the door of his room.

Hardly daring to breathe, lest he might betray himself, Blake heard the faint shuffle, shuffle of stockinged feet across the floor. In a second the cupboard door was open, and a brilliant light illuminated the room.

Blake stood erect, with a revolver in one hand and an electric torch in the other.

Opposite there stood a tall man, a ludicrous picture of dismay and fright. He was in his trousers and shirt, and in his hand he held a handkerchief. As he looked up, with his mouth half open, Blake could not repress a smile.

"Drop that handkerchief," he said—"chloroform, I expect—and sit down on the bed!

"No," he went on, "I have not got that match in my possession. I'm afraid you won't have a chance of telling the Marquis as much, as I am going to give you in charge. I should have thought the Marquis would have known I was not quite such a fool as to carry valuable property about with me. Now, Mrs. Medlicott," he added, as the landlady entered the room, "do you think you can find a policeman?"

In a few minutes a constable appeared, and the man was given into custody.

"Take him away, officer, and keep him back for a couple of days, and then I'll appear, I'm too busy til then."

"Can't 'elp that," said the policeman, "You'll 'ave to appear at the court tomorrow."

"Take your orders," was the quiet reply. "I'm Sexton Blake."

The policeman collapsed, and led away his prisoner, who was too greatly astonished to say a word.

"Now, Mrs. Medlicott," said Blake, "I think I'll go to bed."

And the astonishing man slept soundly till eight the next morning, when he rose, had a good breakfast, and then started of to Baker Street. As he turned the corner of the railway-station he saw a smart-looking commissionaire gazing into the shop window next to his lodgings.

Blake went up to him and tapped him on the shoulder.

"Waiting for me, my man, aren't you?" he asked.

"Me, sir? No, sir!" said the man, turning round in surprise.

"I think you are," went on Blake. "But if you must wear disguise, see that it's a proper one. Black broad-cloth trousers don't go with a commissionaire's uniform, you know. And if you want to wear a false moustache, see that it's glued on properly. There!" He twitched at the man's moustache, and it came off in his hand. "Take that back to the Marquis with my compliments, and tell him that I got back home quite safe, and sha'n't lose anything—not even a match!"

The man grumbled out an oath, and strode away.

Blake watched him with a smile, which faded away as he muttered to himself:

"The Marquis means business, I must keep my eyes skinned."

Upstairs he found Tinker, heavy-eyed and drowsy. for the want of sleep.

"Good gracious, my lad," exclaimed Blake, "you surely haven't been here all night!"

"Yes, sir," replied Tinker cheerily. "I thought perhaps you might ring me up."

"Good lad! But don't overdo the work, or I shall have you laid up. Anything happened?"

"No, sir—nothing. I got home safely, and took the hansom back to the yard without any further trouble. Someone rang up at about ten at night and asked me where you were, I told them Rider Street, as you said."

"You've done well, Tinker," said Blake. "And now, directly, I shall want you to go to the office of the 'Era,' the theatrical paper, you know, and hunt up the file till you find out where the Marquis appeared on the stage, and who was in the company with him."

"Very good, sir. I'll find out all about him, if I have to go back to the year 1!"

Tinker Rehearses — The Man with the Knife —

Tinker Saves Blake — The Hotel Mystery.

BLAKE told Tinker all about his adventure of the night before.

"Now be careful in everything that you do, Tinker," he said "The Marquis means to have me out of the way, and I mean to have him in gaol. What his game is, I don't know, but he's worth fighting, and I am going to get to the bottom of this, whatever it is."

"But, sir," asked Tinker, "how ever did you know he would put one of his men on you at Rider Street?"

"I didn't know, Tinker," answered Blake, with a smile, "I guessed, I gambled on the chance, for I reckoned the Marquis knew I had that match on me, and wanted it. First he tried to upset the cab; then two of his men were in that cab which I told you to lose. Another one, disguised as a hawker, was watching No. 96, Rider Street, Therefore, anyone with a pennyworth of brain would know they were after me.

"The bedroom incident was absurdly simple. It is an old thieves' game to take rooms next to the man you want to rob. I thought they would try it on, and when Mrs. Medlicott described the new lodger, I knew it was Fordyce, the most expert hotel thief in London. He was evidently there for something, so all I had to do was to wait and arrest the gentleman. First trick to Sexton Blake!"

"And where is the match, then, sir?" asked Tinker.

"With Professor Alwyn, Tinker. Don't forget that, whatever happens to me. Now, you come away with me to the Monument Theatre. We're going to be actors, and afterwards you can go to the 'Era' office."

"Guess you think the Marquis murdered poor Mr. Revelle, sir, with that match."

"You'll know soon enough, Tinker. Now let's go to the show."

At eleven o'clock they presented themselves at the theatre, and were soon on the stage, where they found Merrivale.

"I've had a good look at the part," said Blake, "and I think I can manage it. By the way, I've brought up a little protege of mine. He'll be useful to me in the dressing-room, I dare say, if you don't mind."

"Certainly—certainly! Ever been on the stage, my boy?"

"No, sir—no, sir," replied Tinker; "but I've often thought I'd like to."

"He seems a smart lad," said Merrivale, turning to Blake, "I think he could play that little cockney messenger in the last act. We'll try him, if you like."

The rehearsal started, and Blake astonished everyone by the ease with which he trod the stage for the first time in his life.

If they had known the different parts he had played on the stage of life they would not have been quite so astonished.

His sonorous, clear voice rang out over the theatre, and the beautiful words gained in intensity and feeling by his delivery.

At last it came to Tinker's turn. He was given a little brown-paper-covered book, and told to read the lines when it came to his cue.

A cue, it should be explained, is the last word spoken by one character, and means that it is now the turn for someone else to speak.

Tinker listened attentively to what the others did, and when it came to his turn, he ran on the stage and read his lines in the cockney accent that they demanded.

The part was not a long one—that of a cheeky messenger boy; but it required to be played in a light and jolly way.

Merrivale was delighted with Tinker.

"He's a find, that boy of yours," he said to Blake, "He will play that part admirably, and he shall have a couple of pounds a week for doing it."

Tinker was secretly elated, for he had always had a great ambition for the stage, possibly owing to the disguises which at times he assumed in the service of Sexton Blake.

The first act was gone through again, and as Tinker had nothing to do in the early part of the play, he wandered across the stage, examining everything with interest. The ingenious arrangements for the lighting, the scenery, and the thousand and one wonders of the world behind the scenes attracted him with a strange fascination.

As he walked down the left-hand side of the stage, or, as it is theatrically termed the prompt side, he noticed several overcoats and hats which had been flung to the side by the actors.

Tinker picked them up, and placed them on a chair. Then, noticing Blake's coat he put that by itself, so that there should be no confusion when the rehearsal was over.

"'Ere, 'ere, where are you putting that coat?" asked a rough voice. That chair'll be wanted directly."

Tinker turned round, and saw a sullen-looking man in his shirtsleeves.

"'Ere, put it up behind 'ere; there's a nail. Mr. Blake's coat, ain't it?"

"Yes," said Tinker, curiously wondering why the man wanted to know if it was Blake's coat. Then he hung it on the nail, and walked away.

In a few minutes he returned, and, walking on tiptoe, saw the man in shirtsleeves busy rifling the pockets of Blake's coat.

With a bound, Tinker was on the man, and seized him by the wrist.

"'Ere, 'ere, what's up?" said the man, trying to release his hand. But Tinker had him fast, and dragged him to the centre of the stage.

"I found this man with his hand in Mr. Blake's pocket, he explained to Merrivale.

The man flustered and blustered, but it was no use, and Merrivale finally pronounced judgment.

"You'll have to go, Rogers," he said. "We can't have this sort of thing in the theatre. Get your money at the office and go."

Rogers muttered and growled, and then slunk off, casting evil glances at Tinker.

"Good boy, Tinker!" said Blake, when rehearsal was over. "Now, you pop off to the "Era" offices and look up the Marquis's career, and I'll get back to Baker Street."

As they walked down the little side street which led from the stage door, Blake suddenly pulled Tinker up with a jerk.

Phit! Something buried itself in the wall at their side.

"I thought so," said Blake, examining the mark on the plaster, "It's one of those new German air-guns. Look out for another, Tinker. Look out, lad! "There it is!"

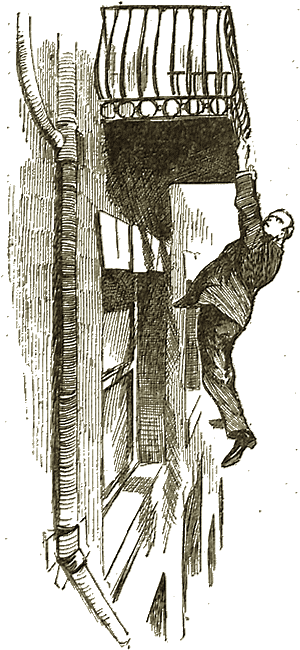

Phit! The same thud as before, and Blake looked up to the third floor of a dirty house, let out in tenements.

"Third floor front," he muttered. "And the sun shone on something bright. Are you with me, Tinker?"

"Like a bird, sir."

The general door of the house was open, and they ran up the stairs till they reached the third floor. Blake knocked at the door. There was no answer, and the detective produced from his pocket an exquisitely made little jemmy of aluminium—light, and yet hard as rock.

Blake winked at Tinker, and whispered:

"The gentle art of housebreaking, Tinker. Watch!"

He placed the jemmy in the door just below the lock, and seemed to give a gentle twist with his finger. Crack! The lock dropped on the floor, and Blake and Tinker walked into the room.

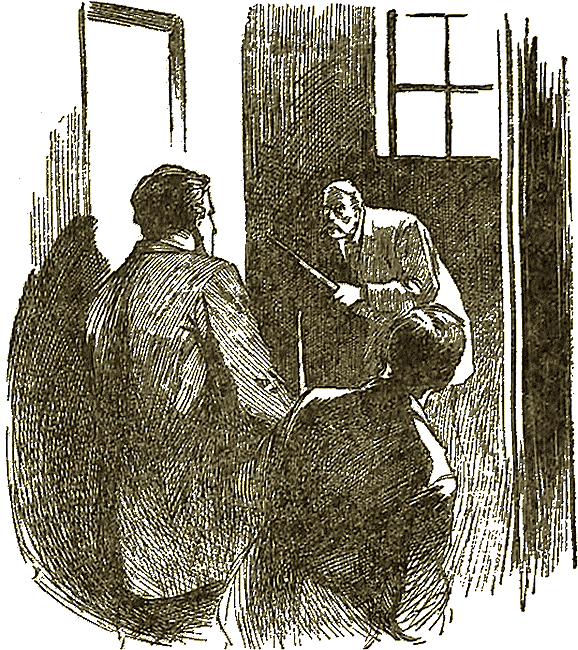

Crouched below the window-sill was Rogers, the discharged scene-shifter; in his hand he had a long, shining air-gun. In his surprise at the unexpected entrance he seemed speechless and unable to move.

Crouched below the window-sill was Rogers, the discharged

scene-shifter; in his hand he had a long, shining air-gun.

Blake walked over, and twisted the gun out of his hand.

"I thought so," he said. "One of those German inventions; deadly, too, at short range."

"Look out, sir! For Heaven's sake. look out!" shrieked Tinker, as another man, with a knife in his hand, leapt from behind a chest of drawers and flung himself on Blake.

Blake half turned, and in another minute he would have been stabbed in the back, when Tinker jumped like an athlete and caught the man's hand as it was descending.

Blake put out his foot, dashed his fist in the man's face, and sent him spinning across the room, while his knife clattered to the floor.

"Thanks, Tinker," said Blake. "Keep the knife as a memento, and I'll take the gun. I don't know this other gentleman, but I know that Rogers. Mr. Rogers tried to kill me last night by dropping a heavy iron bar on my head, and now he's tried it again. My regards to the Marquis, and tell him he's clumsy—deuced clumsy! Good afternoon, gentleman! Come along, Tinker!"

When they were outside, Blake took the knife from Tinker.

"I'll take this home with me," he said, "and you get off to the 'Era' and hunt up the Marquis, and then come back to me. And take care of yourself, there's a good boy!"

Tinker hurried away to the newspaper office, and Blake jumped into a cab. As he drove across the Strand he saw the newsboys excitedly running with huge bundles of papers which were being bought up as fast as they could sell them. He stopped the cab and bought one. A bold headline caught his eye:

"MYSTERIOUS DISAPPEARANCE OF DAN SELLARS.

AMERICAN MILLIONAIRE DISAPPEARS FROM

THE MAMMOTH HOTEL. FOUL PLAY SUSPECTED."

Blake folded up the paper and remained in deep thought till the cab stopped at Baker Street.

When he was safely in his sitting room, he opened the paper and read intently:

"Dan Sellars, an American millionaire, known as the Cotton King, had for some weeks been staying at the Mammoth Hotel. The previous night he had entertained a few friends at dinner, and retired to his bedroom early. When his servant went to call him the next morning the room was in a state of disorder, as if there had been a struggle, and the millionaire had disappeared. No trace could be found of him, and the matter is now in the hands of the police."

Such was the bald statement in the newspaper.

Sexton Blake took down a book of reference, hunted up the career of the missing man, and then stretching himself on the sofa, thought long and earnestly till the return of Tinker.

The First Night — The Deadly Wine —

Tinker Scores a Success — Dan Sellars.

IN about an hour's time Tinker returned.

"Well," said Blake, "what luck?"

"Found out all about him, sir," panted Tinker excitedly, "I turned up the volume for 1890, and found this paragraph: 'Mr. Alistair Rortrey, who has just completed an engagement at the Albert Theatre, will go on tour with the entertainment party known as the Eastern Mysteries, Mr. Rortrey will be stage-manager, and the company will include the celebrated Ram Chowder.'"

"Good—good!" said Blake, sitting up on the sofa. Anything else?"

"Yes, sir. Six months later there was this paragraph: "Mr. Alistair Rortrey, who has just concluded a successful engagement with the Eastern Mysteries, has decided to leave the stage, and return to commercial life." There were two or three other references to him, and I copied them all, but I didn't think they were important. In one engagement I see he played in a piece by Aston Revelle, and Mr. Merrivale was the stage-manager."

"That's a coincidence, Tinker, said Blake. "And, now let's have a look at our parts."

The rest of the day they spent learning the words of their parts for the last week's rehearsal.

Both Blake and Tinker earned golden opinions by the way they spoke their lines, and got inside the skin of their respective characters.

Merrivale professed himself delighted with them, and prophesied an enormous success for the new piece.

From the theatre wardrobe Tinker was provided with a messenger suit—a costume to which he was not unaccustomed—and Blake provided himself with some new and fashionably cut clothes for his part.

"The Marquis is quiet, Tinker," he said, as they drove to the theatre on the first night; "but I dare say we shall hear from him before long.

"Any clue to the murderer yet, sir?" asked Tinker.

"I have a bundle of clues, Tinker; but as yet they are tangled. But you shall be in at the death, my lad. I promise you that. Now, just jump out and get that paper they're crying."

Tinker hopped out, and returned with the paper.

Blake threw open the sheet, and looked casually down the columns.

"I can't see anything to make a fuss about, Tinker. But what's this, by Jove!"

He read, aloud:

"'RETURN OF MR. DAN SELLARS.

'The American millionaire, about whom there were sensational reports last week, returned to the hotel that morning. To a representative he stated laughingly that he was much flattered by the interest taken in his movements, but he had only been away for a few days, and he was sorry he had left his room in such a mess; but he was very sorry he hadn't been kidnapped. Mr. Sellars expressed himself as being perfectly well, and announced his intention of being present at the first performance of the "Love Light," at the Monument this evening.'"

"Capital!" said Blake, when he had finished. "I should like to see Mr. Sellars."

The crowd had for long been standing outside the pit and gallery entrance, and many curious glances were cast at Blake and Tinker as they walked up the narrow passage.

"Who's that little chap?" asked one.

"I don't know his name," replied another, "but I hear he's very good. A friend of mine was at the dress rehearsal, and says he'll make a hit."

Tinker heard, and walked on, feeling as if he had come into a fortune.

"Now, then, Tinker," said Blake, in the dressing-room. "I'll just put myself right, and then I'll attend to you."

Blake was no stranger, of course, to the mysteries of making-up, and when he had transformed himself into a handsome, middle-aged man, he turned to Tinker, who was already in his messenger's uniform.

"Now, then, Tinker, smear a little vaseline over your face, so that the paint will run easily."

When Tinker had followed out the instructions, Blake first of all rubbed a pale paint on the boy's face, which he smoothed well in with his fingers.

"That's the groundwork," said Blake; "now for the red. He applied the red to give a natural and healthy look to the face, painted in black lines under the eyes and on the upper lids to make them look brilliant, and gave an upward curl to the corners of the lips and nose, slipped a red, curly wig on Tinker's head, and then told him to look at himself in the glass.

Tinker gave a cry of delight, for he looked the merriest, cheekiest messenger boy that ever handled a message.

"Wonderful what a bit of paint will do, isn't it?" said Blake. "Now come up on the stage."

The first scene was already set on the stage, and Tinker thought how cheerful everything looked at night, compared with the daylight rehearsals. The curtain was down, and the orchestra could be heard faintly tuning up their instruments.

"Come and have a look at the house," said Merrivale.

He led them to the curtain, and showed them a little peephole, through which they looked.

It was a brilliant sight.

The well-lighted house, the fashionably dressed audience, the jewels that glittered—all made up a sight which dazzled Tinker.

"See," whispered Blake, "up in that box is Dan Sellars—that fat man."

Mr. Sellars was a heavily built, fat man, with a red face and a white moustache. He was leaning out of the box, and Tinker had a good view of him.

"Now, then, clear the stage, please!" cried Merrivale, bustling round. "Just going to begin."

In a few minutes the curtain rose, and the play began.

It all seemed so strange to Tinker; as he stood at the side of the stage. Instead of watching the play from the front of the house, here he was, standing at the side, and as a member of the company.

He eagerly watched Blake make his first appearance. The detective walked on with all the ease and grace of the professional actor, and made a decidedly favourable impression on the audience.

At the end of the first act, everyone concerned was called before the curtain, and Blake was specially summoned with a round of cheers.

"There," said Blake, as he threw himself into a chair; "I've got over the worst, and I don't mind telling you, Tinker, I felt decidedly nervous."

"I feel all of a shiver, sir," said Tinker uneasily.

"Yes, I dare say you do. It isn't all honey facing a lot of people for the first time as an actor. But keep up your pluck, Tinker; you'll be all right."

While the second act was being played Tinker sat quietly in the dressing-room, and read up his part for the last time, so as to be perfect.

"It's a great go, Tinker," said Blake, when he came down from the stage. "If only poor old Revelle were here!"

"Are you there, Blake?" said Merrivale, popping his head in the dressing-room. "I just want to congratulate you on your performance. It's great! That's all there is to say about it. You'll make the hit of the evening. By the way, old Sellars, the Cotton King, is in front. He's mad on the theatre, and has sent round a case of champagne for the company. I'll send you in a bottle."

In a few minutes an attendant appeared, and placed a bottle of champagne and a couple of glasses on the table.

"Open it, Tinker," said Blake, "I just want to look up my part for the last act."

Tinker opened the bottle and poured out a glass.

"Go on, my boy, said Blake, looking up; "you can have a glass, too. I don't approve of boys drinking, as a rule, but this is a special occasion. And throw over the cork. I like to know what brand I am drinking."

Tinker threw over the cork, and poured himself out a glass. Blake took the cork, and held it close to his eyes. As he did so his eyes glittered. Then, like a flash, his hand flew to the table; he took up a hair-brush and threw it sharply in the direction of Tinker, who was just raising the glass to his lips.

The brush knocked the glass out of his hand. It splintered into bits, and fell to the floor. "I've changed my mind, Tinker," said Blake. "I don't think champagne would any good before you go on. You look bilious, so I thought I'd better stop you before it was too late."

"Beginners for the third act, please!" shouted the call-boy, outside the door.

"Well, you are quite a beginner, in more senses than one. Now, run along, and don't forget to speak up; that's all you've got to remember, beside the words."

When Tinker had left the room, Blake placed a chair against the door, and took up the cork.

"The cowardly villain!" he muttered, "It's the same smell—the same poison. If I hadn't spotted it in time, I should have gone under, and that poor lad as well. What an infernal shame! Well, it's another link in the chain." And, slipping the cork into his pocket, he went on the stage, where Tinker was waiting to go on, with his heart in his boots.

As he listened eagerly for his cue, he began to wish almost that he had never taken the engagement, and that he was miles away. Then came the dreaded cue, and with a fluttering heart and trembling knees, Tinker walked on to the stage. At first the dazzling light, the hundreds of white faces staring over the footlights almost stunned him. But he pulled himself together, and managed to stammer out his opening lines.

The sound of his own voice speaking to all these people startled him at first, and then encouraged him. He gradually warmed to his work, and as the lines were funny and he spoke them well and distinctly, he was rewarded with plenty of laughs.

At length the scene was over, and when a burst of applause followed his exit, Tinker began to wish that he had more to do.

"Capital, my boy," said Merrivale, patting him on the shoulder. " Don't run away; I expect there'll be a call for you to go on at the end of the act."

When the curtain fell to a pronounced success, the company all had a call before the curtain, and then the pit and gallery gave a unanimous shout for "Tinker! Tinker!" as he had been put down in the programme.

Tinker took his call, and then, bubbling over with joy, rushed down to the dressing-room.

"Good boy, Tinker!" said Blake, who was washing off the paint. "You've knocked them. You'll be in all the papers tomorrow. Yes, come in, whoever you are.

"Sha'n't be in the way, I hope, Blake," said Merrivale; "but there's a gentleman here would like to be introduced to the hit of the evening."

"Send him in," said Blake.

Merrivale held open the door.

"Blake and Tinker," he said, "let me introduce to you Mr. Dan Sellars, of America."

The Marquis Again — The Press Notices —

The Actor-Manager — A Strange Invitation.

MR. SELLARS, in evening-dress, with an enormous diamond blazing in his shirt-front, walked into the dressing-room, and held out a friendly hand.

"Say." he drawled, in a nasal American twang, "I guess I've seen the finest show and the finest acting I've ever struck! Boys, I congratulate you! Guess you were both great!"

"Thanks, very much," replied Blake. "Glad you weren't kidnapped, Mr. Sellars."

"Waal, I should smile, it'd take a darned cute man to kidnap me!"

"I believe if would, Mr. Sellars," said Blake. "I suppose you won't have a glass of your own champagne? I'm afraid it's flat by now."

"Thanks, I ain't drinkin' jest now, and reckon I must git! So long, you boys; glad to have seen you!"

When the American had left the room, Blake dropped into his chair and laughed silently.

"Heavens, what fools some men are!" he said.

"Come on home, Tinker; and don't talk in the cab—I want to think."

As they crossed the stage, Merrivale called to them:

"Rehearsal tomorrow, eleven sharp. Sha'n't keep you long."

"Right you are," replied Blake. "Think we've got a success?"

"Certain; everyone delighted. Look out for the papers tomorrow."

Blake didn't speak a word on the way, and Tinker knew better than to disturb his reverie. When they were in the sitting-room Blake turned to Tinker.

"Promise me not to jump out of your skin if I tell you something."

Tinker grinned, and waited.

"You saw that fat gentleman in the dressing-room tonight?"

Tinker nodded.

"And you thought he was Mr. Dan Sellars, didn't you?"

"Of course I did, sir." said Tinker. "Wasn't he?"

Blake laid his hand on the boy's shoulder and spoke slowly:

"That fat man who was introduced to me as Mr. Dan Sellars was no other than—don't jump—our old friend the Marquis!"

Notwithstanding his promise, Tinker did jump.

"But how, sir," he gasped—"why, how did you know?"

"I had my doubts from something that happened in the evening. Never mind what, Tinker; but when I saw the man I was nearly deceived. But he gave himself away when he stroked his moustache. I saw a triangular cut on his little finger, just under the nail. Now, I gave the Marquis a wound just like that when I arrested him on the Stafford House affair. I looked closer, and recognised the diamond in the shirt front. It was reset, but not recut, and was the identical blue stone which could never be found, and which the Marquis was always suspected of having sold abroad."

"Do you mean the Stafford diamond, sir?"

"The very one, Tinker! But what a make-up! If I may say so, I couldn't have done it better myself! Face, voice, figure, wonderful—really wonderful! And what a nerve the man must have, too, to bluff it off at the hotel and everywhere else! Now, the question is—where is the real Mr. Dan Sellars?"

"The Marquis has got him, sir," replied Tinker promptly.

"Good for you, Tinker!" was the approving remark. "But we must find out where and why. I think this must be the big thing the Marquis was gassing about. Now, then, Tinker, give me the evening papers, and you pop off to bed. You look tired, and I dare say you are."

"Can't I stop up and help you, sir?" pleaded Tinker. "I know what it means when you've got that look on you."

"No, my lad," said the detective affectionately. "I want you to be fresh in the morning, for I shall have some work for you after rehearsal."

With a cheery "good-night!" Tinker went off to bed, and left Blake alone.

The detective looked thoughtfully into the fire for a few moments, and then, rising, he took the cork from his pocket and locked it up in the safe.

"No good telling the lad about this yet," he said. "I'll keep him on the other job at present."

Then, sitting down, he took up a bundle of evening papers, and studied the financial columns for hours.

At length, with a sigh of relief, when the dawn was creeping through the window, he threw himself on the sofa and snatched an hour's sleep. When he woke, it was to find Tinker standing over him with a cup of tea.

"You haven't been to bed again, sir," was the reproach.

"That you, Tinker?" yawned Blake. "A cup of tea, too! Why, bless me, what ever should I do without you? Now, I'll just have a bath, and then I'll be ready for breakfast. Have a look at the papers, and see what they say about last night's performance."

Tinker rapidly scanned the papers which all prophesied a long run for the play, and were enthusiastic over the performance of two actors hitherto unknown to London.

"Mr. Sheldon Blake," said one paper, "is decidedly an acquisition to the ranks of London actors. His performance of the injured husband was manly, forcible, and convincing, and thoroughly carried out the author's idea of the character. Another new-comer—curiously named on the programme as Tinker—also scored a distinct hit as a cheeky messenger-boy. In gesture, action, and voice he was the London boy to the life, and a brilliant career may safely be predicted for him."

"There you are, Tinker," said Blake; "there's glory for you! But don't let us forget our real business in life. Now, listen!"

"Yes, sir," said Tinker promptly, putting down the paper, "I'm ready, whatever it is."

"Very well, then, after rehearsal I want you to go round to old Lazarus and get rigged up as an Eton boy. Silk hat, trousers turned up at the bottom, light waist coat, and a thick gold watch chain, well displayed. You know the rig-out."

"Yes, sir; seen dozens of them at the Eton and Harrow match."

"Good!" Keep your eyes open—that's the way! Then go to Waterloo Station, and hang around the bookstall, where you'll very likely see a nice-looking, fat old clergy-man. That is Mr. Eli Laverton, a luggage-thief and an awful old scamp. He is generally there in the mornings, and knows me well—in fact, he owes me a turn. You go up and ask him which 'bus will take you to Madame Tussaud's. He will be very fatherly and friendly, and will try to annex your watchchain, Oh, I know the old gentleman!"

"Shall I let him, sir?" laughed Tinker.

"When you feel his hand on your waistcoat—as you will do, if I am not mistaken in you—just look up into his face, and say, 'Sexton Blake sent me.' That will be quite enough and the old gentleman will be like wax in your hands. Can you remember all this?"

"Like a book, sir."

"When the old boy has got over his surprise, ask him if he saw the Marquis that morning you drove him to Waterloo, and if he knows where he is living. can't go near the station myself today, as I expect to be at the theatre for some time. But Eli will do, and he hates the Marquis, and will do anything for me. Tell him if he doesn't know he must find out. Now we'll be off to the theatre."

After a first performance there is always a rehearsal the next morning to run through any scene that may hare hung fire the previous night, and to make any alterations that may be necessary.

When Blake and Tinker appeared at the stage door they were assailed with congratulations on every hand.

"I am so pleased," said Merrivale, "that you have made a hit, Blake! Poor old Revelle would have liked to see it! And your little friend here, too—he's got the makings of a fine comedian in him, unless I'm mistaken! By the way, Tinker, you needn't stop—your scene is perfect; but the first and second act want a bit of putting together, so we shall want you, Blake."

Blake winked at Tinker, who hurried away to Lazarus, an old costumier whom Blake had under his thumb, and found very useful.

"Now, then, come along!" cried Merrivale. "First act, please!"

Then there commenced the wearisome business of rehearing what everyone thought perfect. But no play is really at its best on the first night, and an experienced stage-manager will always detect flaws where others would see none.

Blake, with that thoroughness which always distinguished everything he did, flung himself heart and soul into the rehearsal.

"Capital, Blake—capital!" cried Merrivale. "Almost better than last night, if possible! Hallo, Mervyn! What is it you want?"

"I've come to steal one of your actors, if I may," answered a deep, musical voice.

Blake looked round, and saw Mervyn Hallows, a well-known actor-manager, who was running the Piccadilly Theatre.

"Introduce me to Mr. Blake, will you, Merrivale?" he went on.

When the introduction was effected, Hallows astonished Blake with the warmth of his congratulations.

"Capital performance—capital!" he said, I expect you are in for a long run here; but I want you to remember, Mr. Blake, that I shall always be pleased to find room for you in my company when you want an engagement. Good-bye! I thought I would catch you at rehearsal; and now I must be off to my own."

Blake chuckled to himself as he thought of his success in his profession.

"Still," he whispered to himself, "I'll remember Mr. Hallows and his offer; it may be useful."

It was nearly three when the rehearsal was over, and Blake congratulated himself that he had sent Tinker to Waterloo, and so wasted no time. As he was leaving the theatre, Merrivale hurried after him with a telegram in his hand.

"Doing anything after the show tonight, Blake?" he asked.

"Nothing particular. Why?"

"Well, here's a telegram from old Sellars. He wants all the men of the crowd to have supper with him at the Etcetera Club. I believe he does the thing very well—champagne in buckets, you know."

"I don't mind," said Blake. "But why is Mr. Dan Sellars so anxious to entertain the company to supper?"

"Oh, the old chaps mad on the theatre, and likes entertaining actors! You'll come, then?"

"Like a bird." said Blake.

And as he walked on his way, he thought:

"This is a most stupendous piece of luck! But I wonder whether it is the real Sellars this time?"

Tinker in Disguise — The Attack in St. Martin's Lane —

The Club Concert — Which Mr. Sellars?

AS Tinker, in silk hat and correct Eton get-up, walked up the approach to Waterloo Station, a small and dirty boy of about his own size looked up at him impudently.

"Where did yer git that 'at, guv'nor?" he said. "A shillin' more, and you could 'ave 'ad one to fit yer!"

Tinker took no notice, but walked on.

The dirty boy, emboldened, followed behind with insulting remarks.

"Goin' to meet yer girl, ain't yer? Mind yer don't lose 'er."

Still Tinker walked on, for though he was getting cross, he remembered that he was out on Blake's business, and ought to avoid a scene. But at last the boy behind took up a stone, and caught Tinker in the middle of the back.

Tinker turned as an a pivot. With one movement he caught the boy by the collar, and with another he gave him a twist, and dropped him neatly into the gutter, where he became dirtier—and wiser.

Then, without a word, Tinker walked on, feeling that Blake surely would have approved of his conduct.

In the station he hovered round the bookstall, bought a paper, and kept a sharp look-out for an elderly clergyman. In a few minutes he saw a stout, elderly man in clerical dress, with snow-white hair, and the most benevolent expression, wander in from the street.

As he put up a pair of gold-rimmed spectacles and examined the time-table on the wall, Tinker went up and spoke to him.

"Excuse me, sir, but could you tell me which 'bus I ought to take for Madame Tussaud's?"

The old gentleman looked down with a fatherly smile and Tinker almost felt his eyes rest on the watchchain.

"The right 'bus, my boy, certainly!" he said.

He led the way out of the station and pointed.

"Not that one," he said, "but the one with the red stripe."

Tinker's hand went up to his waistcoat and clutched the fat fingers.

"Sexton Blake sent me," he said quietly. "That 'bus? Thank you!"

The old man's hand dropped, and he went on in an even voice:

"Sexton Blake. Yes, very well; I'm afraid there's not another 'bus for some time yet. Better come and have some lemonade, my boy."

He led the way to the refreshment-room, and had lemonade and coffee brought to a quiet corner.

"Now, then," he went on, "what can I do for Blake?"

Tinker rapidly told him what was wanted, and the old man's eyes glittered, and he frowned in a very unclerical manner.

"The Marquis—yes, yes, I know. I saw him go off the other morning. Now, tell Mr. Blake I don't know for certain where the Marquis is living, but he went off in a Surbiton train, and years ago he had a house there—The Firs, Grange Road. That ought to be clue enough for Mr. Blake. And how is my friend, the gallant Sexton?"

"Oh, he's splendid!"

"Ah! A good fellow that. Put me in gaol, and kept my wife all the time I was there. And who are you?"

"I sometimes help him in little things," said Tinker modestly.

"Well, you've done this little job very nicely, and that's a compliment from old Eli. Tell Mr. Blake there seems no chance of making a living at the station nowadays. People seem to have no luggage, or look after it too well. Poor old Eli will have to turn honest, after all!"

"Many thanks for the information; and now I must go," said Tinker, jumping up.

"Must you really, my boy?" said Eli. "Well, I'll show you the 'bus. Can't be too careful," he whispered, as they went out. "I believe the nasty station people are actually beginning to suspect poor old Eli. Scandalous, isn't it?"

Tinker choked down a laugh, and jumped inside a 'bus.

There was no other passenger, and the old man poked his head inside.

"Tell Mr. Blake." he said, "that I had the satisfaction of lifting one of the Marquis's bags the other morning, and there was nothing in it but dirty shirts! It'll make the gallant Blake smile."

And the 'bus moved off, leaving the old scoundrel waving a fat hand, and looking the picture of virtue.

Tinker went back to the costumier's and changed; and then returned to Baker Street.

When Blake arrived later, Tinker gave him a faithful account of what Eli had told him.

"Surbiton—eh? mused Blake. Tinker we may have to ride a long way out of town before morning, and we have to walk back. Put some of those special beef lozenges of ours in your pocket, and remind me to take my revolver."

The beef lozenges, one of which would support a man half a day, were packed away in Tinker's waistcoat pocket, and Blake took his revolver to the theatre.

At the stage door, Tinker found a card, bearing on it the name of a well-known newspaper, and a line scratched on it, asking for the favour of an interview.

"That's fame, my lad," said Blake. " You'll find the newsboys selling your full life and career tomorrow morning."

Tinker received the reporter in the dressing-room, and discreetly answered his questions, leaving out, of course, any reference to his connection with the celebrated detective.

"Thanks, very much!" said the reporter, closing his notebook. "That'll make a capital interview, and, personally, apart from my newspaper, I must say that I laughed at you last night till I was sore."

When the reporter had gone, Tinker began to wonder whether the stage was not as exciting as the detective business.

"Anyway," he thought, "I'm combining the two, so nobody can say I am idle."

"Three calls tonight, Tinker," said Blake, coming off, panting. "By Jove, the stage fever is getting hold of me! But what glorious practice for our own business—eh? My voice is getting more flexible, and though I thought I knew something about disguise, I seem to have plenty to learn. Now, my boy, make yourself up tonight. It'll be good practice for you."

Rather nervously, Tinker applied the paint himself, and was surprised to find what effect a few careful lines will have.

"Excellent!" cried Blake, when he had finished. "Now, don't forget that twist of the mouth; it gives you a comic look. Excellent! That's it!"

Tinker looked at himself in the glass with justifiable pride, and then went up to the stage for his scene.

As on the previous night, every joke told, and the little messenger boy quite bore out the remarks of the newspapers.

Tinker now began to feel at home on the stage, and with all his nervous feelings gone began to understand the fascination of the drama.

"You'll be a great comedian yet, Tinker," said Blake. "And now we'll be off to the Etcetera Club, for Mr. Dan Sellar's supper-party."

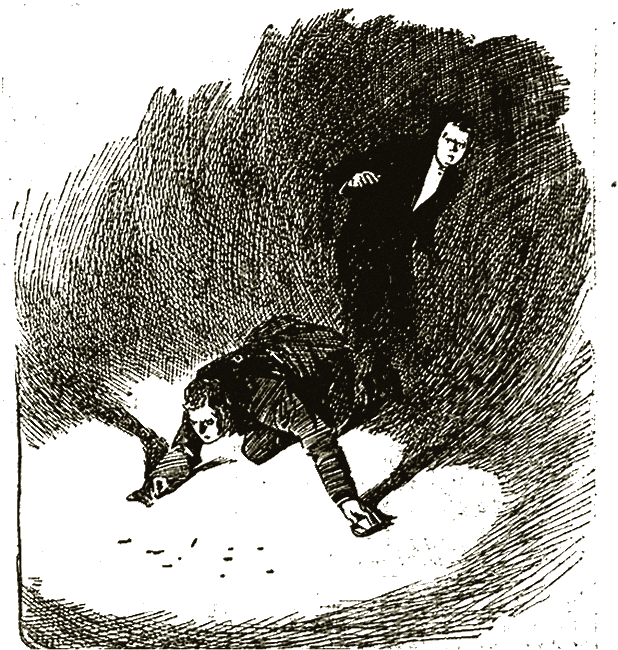

As they turned up St. Martin's Lane to take a short cut, two men shuffled out from a highway, and whined something to Blake.

"What is it? What do you want?" asked Blake.

One of the men repeated something, and shuffled closer.

"Hunger; no bed, signor," said the man, advancing.

"Poor fellows, wait a minute," said Blake, putting his hand in his pocket.

The man said a few words to his companion, and took another step forward.

Like a flash, Blake's hand was out of his pocket, and the man dropped like a log with a broken nose, while the other found himself smelling the muzzle of a revolver held in Blake's left hand.

The detective rattled off a few words in a foreign tongue, and the men pulled themselves together and shuffled off.

"Italians, Tinker!" said Blake. "I knew what they were up to when they came up, and I heard one of them say, 'Quick, now, the knife!' Look, here's a tip for you."

He held out his hand, and showed half-a-crown in the palm.

"I waited till I got hold of that, and then let out. You can always hit harder when you've got something in your fist. I think I've frightened these good gentlemen. I told them I knew their names, and where they live, which I don't. Tinker, my lad"-he stopped and spoke impressively—"you know how I hate to be questioned when I am working out anything; but I'll tell you this— every step I take brings me nearer the murderer of my dear friend, Aston Revelle. Now, let's get on to the club."

The Etcetera Club is perhaps the best-known Bohemian club in the world. Actors, painters, singers, racing-men, millionaires, musicians, and everybody who his anybody, belongs to the Etcetera.

On this particular evening the handsome club-rooms were full, as Dan Sellars had extended a general invitation to everyone to meet the members of the Monument Theatre at supper.

Blake and Tinker were introduced to a crowd by Merrivale, and quickly made welcome, with that good nature which distinguishes the dramatic profession.

"Come and sit by me, Tinker?" said one of the Monument men.

"Not a bit of it," put in Blake. "You'll give him champagne which isn't good for youngsters. I may want you Tinker," he whispered. "Sit close."

Down the length of the magnificent dining-room ran the supper-table, loaded with delicacies and decorated with costly flowers.

At that moment there was a stir at the upper end of the room, and some festive spirits struck up, "For he's a jolly good fellow."

"Gentlemen," shouted a nasal voice, "take your seats, and guess we'll wade in."

Laughing and chatting, everyone scrambled into his chair, and Blake looked intently at the figure at the head of the table.

"Look, Tinker!" he whispered. "There's nerve for you, Fancy that man being able to bluff all this company—all, except you and me! By Jove, this is better than any play!"

"Gentlemen, rang out the nasal voice, "I give you the old toast—luck, astonishing luck, and all that you wish yourselves."

The toast was drank with enthusiasm, and the clatter and the laughter began afresh.

Blake turned to Tinker with the strange light in his eyes, which only came when he was excited.

"Tinker," he whispered, "he's not wearing the diamond, and when he lifted his left hand there was no scar on the little finger. My eyes are like gimlets, and there was no scar, I'll swear. Now, my boy, think out which Mr. Sellars it is this time."

Tinker as Comedian — The Tramps —

The Midnight Ride — Two Dan Sellars.

WHEN the cigars and coffee had been handed round, Dan Sellars hammered on the table and called for silence.

"Guess we'll have a song," he said, "if any of the boys will volunteer."

A well-known tenor quickly sprang to the piano, and in a sweet, liquid voice sang a pretty ballad.

After that there was no lack of talent, and song, recitation, and funny story followed in quick succession.

"I'm not quite satisfied with Mr. Sellars," confided Blake to Tinker. "I can't get a look at that little finger somehow."

At last the opportunity came.

"And now," drawled Sellars, when Sir Harvey King, the eminent tragedian, had thrilled the company with a recitation, "will any of the guests of the evening oblige?"

"You, Blake, go on!" cried Merrivale, from the end of the table. "Give us a show of some kind!

"Fill up five minutes, Tinker," he whispered. "I'm thinking out something."

"Blake—Sheldon Blake!" cried the company.

"All right, in a minute," replied Blake. "In the meantime, my little friend here will oblige."

A round of applause greeted Tinker as he made his way to the little platform at the end of the room.

He had never recited or performed by himself in his life, and he was wondering what sort of a fool he would look, when an idea passed through his mind.

He had often amused his friends with imitations of animals and street cries, and, in default of anything else, he would try them here. As he mounted the platform a sudden thrill of terror went through him.

It is no light thing to entertain a number of people single-handed, and when those people are all professional actors of the highest standard, the boldest might well think.

His first imitation of a parrot went well, and, with the cordial applause ringing in his ears, Tinker felt encouraged, and warmed to the task.

One after the other his imitations of animals and street cries rang out clearly and distinctly in his flexible, easy voice, and with each successive effort the applause re-doubled. He concluded with rather a daring piece of work, which was nothing less than an imitation of Dan Sellars.

The raucous voice, the nasal twang, were hit off to perfection, and as Tinker stepped off the platform, the room rang with laughter and cheers.

"Excellent—excellent!" said the deep voice of Sir Harvey King.

And Tinker felt that a compliment from England's greatest actor was worth all the rest.

"Now I call on Mr. Sheldon Blake!" cried Sellars.

Blake rose with a peculiar smile, and walked to the platform.

"Gentlemen," he said, "as a change from song and story, I will endeavour to show you a few experiments in thought-reading."

He commenced with the familiar experiment of finding a hidden pin while blindfolded, and followed up with a few other tricks which are by no means difficult.

"Now," he finally said, "for my last experiment I would like the assistance of the chairman. I ask you, Mr. Sellars, particularly, so that there may be no thought of collusion. Have you a five-pound note in your pocket, Mr. Sellars?"

"I think I have," slowly replied Mr. Sellars.

"Then may I ask you to carefully get the number in your memory, and I will tell you what it is."

A hum of expectation went up as Sellars opened his pocket-book, took out a note, looked at it earnestly for a few seconds, and then put it away again.

"Guess I have got that fixed in my mind now!" he said.

"Very well, then," went on Blake, "I think the company may take your word and mine that I have never seen that note before."

"Of course that's so."

"Then will you kindly put your left hand on my forehead, and think hard of the number?"

Sellars did as he was asked, and, amid a dead silence, Blake called out some numbers rapidly, one after the other, which were taken down by Merrivale.

"There," said Blake, dropping Sellars's hand, and wiping the perspiration from his forehead. "Now will you compare the numbers."

Sellars rapidly compared his note with Blake's numbers, and announced in a loud voice that they tallied exactly.

"Guess that's the cutest thing I ever struck," said Sellars, when the applause had subsided. "And now we'll have the next song."

When Blake, appearing exhausted from the thought-reading—which invariably is the case—sat down, he whispered to Tinker, under cover of the song:

"I'm going to be ill directly, Tinker, and when I go out you come along too."

Blake's face grew gradually whiter, and at length he turned to Merrivale, who had drawn up his chair.

"I am not feeling very well, old man, said the detective. "That thought-reading always takes it out of me, I think I'll slip off on the quiet. Don't make any fuss."

"I'm awfully sorry!" replied Merrivale. "Can I do anything for you?"

"Nothing, thanks. Tinker here will see me into a cab."

The two slipped out unperceived, and when they were outside the club, Blake struck to the right up Regent Street.

"Don't hurry, Tinker," said Blake. "We're going back that way directly. Half-past one. The club closes at two. We've got plenty of time. Come into this doorway."

Blake produced a little box of paints, which he carried with him, and in a few minutes made up his own and Tinker's face. Then, taking out his penknife, be ripped away at coats and trousers till they were both in rags.

"Now, than, yours, Tinker."

Tinker's garments were served in the same way, and when Blake took a couple of handfuls of dirt, and rubbed them all over him, telling Tinker to do the same, Regent Street had a couple of the most disreputable night-birds in London.

"Tinker," said Blake, as they shuffled along the pavement, "you're a good boy, and don't ask foolish questions, therefore you shall have your reward. I'm going to take you with me tonight, and there may be a row."

"Nothing I should like better, sir." promptly replied Tinker. "Is it the Marquis?"

"It is our old friend, Tinker. He'd actually painted his finger to hide the scar, but I felt the ridge when he put his hand on my forehead. There's no getting away from a scar, Tinker; you can always feel it. And the dear fellow thinks he's bluffing me! Poor Marquis!"

"And did you really read the number of the note, sir?

"Of course I did; thought-reading is easy enough when you know how. And that not happened to be one of the lot stolen from the City Bank last week. You know my memory, Tinker, and I spotted the number in a second. That'll keep; but I'm afraid the Marquis is up against a lot of trouble."

By this time it was nearly two o'clock, and they were within a few doors of the club.

"Straight on, and keep under the portico, Tinker. Follow me, whatever happens; they're just coming out now."

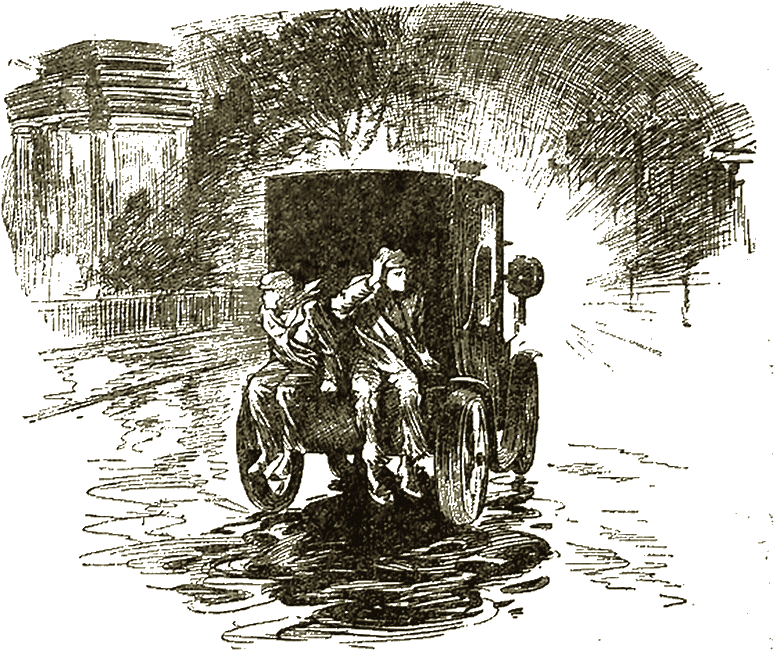

From the Etcetera Club came the actors, chatting and laughing, and from their hiding-place Blake and Tinker saw the fictitious Dan Sellars walk down the steps and get into his electric brougham.

After a hearty farewell by the crowd, the brougham turned and glided across Piccadilly in front of the doorway.

"Now, Tinker!" hissed Blake.

And, stepping out, he jumped on the crossbar behind the brougham as it sped past.

"Now, Tinker!" hissed Blake. And, stepping out, he jumped

on the crossbar behind the brougham as it sped past.

Tinker followed, and, with Blake giving him a hand, he found himself perched somewhat insecurely on the bar.

"Hold tight," said Blake. "And let us hope the police are all asleep, or we shall be dished."

By great good fortune they were unperceived, and as they got well out of Piccadilly the pace increased.

"It was not a comfortable seat, and the stones and dirt flew up and hit Tinker in the face; but he clung on, determined to show that he was worth the confidence reposed in him.

"I believe we're going to Surbiton," said Blake, as they rattled through Kensington and down the Hammersmith Road. "Yes, we are. That's good! And I think the Marquis's little game will soon be up!"

But the brougham accelerated its speed, and conversation became impossible.

Soon they reached Surbiton, and, rapidly mounting the hill, they turned into a dark road.

"Grange Road," said Blake. "We ought to be at the Firs, then. Tumble off when I give the word, Tinker."

In a few minutes they turned into the open gate and up a long drive.

"Now!" said Blake.