RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"YES, Edward, I have decided to make you a present. When home for the holidays, although prone to get into mischief with those Scout boys, you obey my word."

"Of course I do, uncle; you've been very good to bring me up and educate me since father and mother died," said Ted Raymer to his great-uncle.

Old John Raymer shot a suspicious glance in Ted's direction.

"I have told you more than once that the carving above the study fireplace must not be fingered, and I believe you have obeyed me?"

The last sentence was spoken as a question, so Ted answered

"I haven't touched the carved mantelpiece ever since the time you were so angry with me for climbing up on a chair and trying to reach the goblin with one eye. And that was years ago, uncle, when I was just a tiny kid."

The old draper's glance was more suspicious than ever.

"Is there a one-eyed goblin in the mantelpiece? Well, if there is, you're a good boy for not touching it, and I'll make you the present I had in mind"

"Oh, thanks, uncle," said Ted gratefully; it was seldom that Great-uncle John Raymer gave gifts. "May I know what it is, sir?"

"A gramophone that makes its own records," answered John Raymer.

"What fun!" exclaimed Ted Raymer. Usually his great-uncle's presents were so beastly useful—a change of woollen under-clothing at Christmas, a box of handkerchiefs on his last birthday—his fourteenth. And always chosen from the shop downstairs, for his uncle was the chief draper in Stippleton. "Oh, uncle, a gramophone!"

The draper frowned. "I bought it for use, not fun," he said grimly. I have written down six maxims which I shall repeat into the Baby Dictaphone, as I believe the traveller called it. These I have recorded on the disc, and the gramophone will repeat the maxims to you so that you may commit them to memory this afternoon.

"Oh, but, uncle—" cried Ted, all his hopes dashed to the ground at thought of a gramophone which was merely to be another form of lesson. "I've got my holiday task to finish."

"The maxims must be learnt, Edward," said John Raymer sternly. "Barkin will bring the record to your bedroom safely wrapped in cotton wool. And, by-the-bye, don't let him see the dictaphone, or he will want me to install one in the office, and one for office use costs fifty pounds, I believe. He is getting too big for his shoes is Mr. Barkin."

"Yes," agreed Ted warmly. He didn't like his uncle's right-hand man.

Directly after dinner Ted was sent to his bedroom, and ten minutes later Barkin arrived with a box.

"Something from the Guv'nor," said Barkin; "says it's guaranteed to keep you out of mischief for a bit, you young nuisance."

Ted was going back to boarding-school next day, and he didn't like parting enemies even from Barkin.

"I say, I try not to be a nuisance. Why can't we be friends, Barkin? I'm sure I've never done you a bad turn, and yet you always cuss me."

Barkin's hard features didn't relax.

"I've been with your uncle sixteen years—slaved for him before ever you were born. And it's you who are to come in for his money."

"He's never told me that," said Ted, "but I have heard him say a dozen times that you were to have his business when he died."

"Get on with your job, whatever it is," said Barkin, and slammed the door as he went out.

Locking the door as his uncle had directed, Ted put the disc on the gramophone plate and soon in his uncle's harsh voice there droned forth the maxim :

"Early to bed and early to rise

Makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise."

There followed others down to the sixth maxim which came grimly forth from the gramophone:

Have a care to save each penny,

Pennies grow to make pounds many."

It was a sickening job for the last day of holiday, Ted thought, and he only with difficulty prevented himself from flinging the offending disc out of the window on to the head of Barkin whom he sighted passing through the yard to the warehouse. But Ted knew only too well that his great-uncle's will was law, and that it would be useless to protest. So the maxims were duly learned and repeated without the instrument's aid.

"That is satisfactory, Edward," the stern relative said. "From time to time I shall make a record of such maxims as I think you should learn and inwardly digest. The discs will be sent to your Headmaster, and he can allow you to use the gramophone which teaches you French, I believe. Then when you come home to me for the holidays, I shall expect you to repeat these maxims without a mistake."

So there was no gramophone to take back to school, no records could be made of his chum Podger's imitation of a cat fight, no record of his own speech at the Debating Society—the beastly thing was only to be used as an extra lesson-producer. What a rotten present!

Sure enough, all arrangements were made with the Head, and three weeks after he returned to school, Ted found himself seated in the study one fine afternoon with three maxims to learn.

"Maxim one," came the stern voice of his uncle out of the machine. "Honesty is the Best Policy."

Ted groaned, but the gramophone went on:

"Maxim Two. He who seeks to get rich without working is a lazy nincompoop."

Ted groaned again, but the gramophone continued.

"Maxim Three. Ill-gotten gains are a curse to the getter."

"Pah!" said Ted. "Poor old uncle is getting dotty. Now if he had told that beast Barkin to learn those three maxims, there might have been some sense in his present. Pah!"

Privately the Head thought it was a new form of torture for a schoolboy, but the Head knew that there was no escape from the tyrannical old draper's orders.

There was, however, no third list of maxims for Ted to learn. Instead of a disc from Stippleton, there came a telegram:

UNCLE VERY ILL COME AT ONCE.—CRUMMY.

The telegram was sent by Mrs. Agnew, his uncle's housekeeper, of whom Ted was very fond and whom he called Crummy.

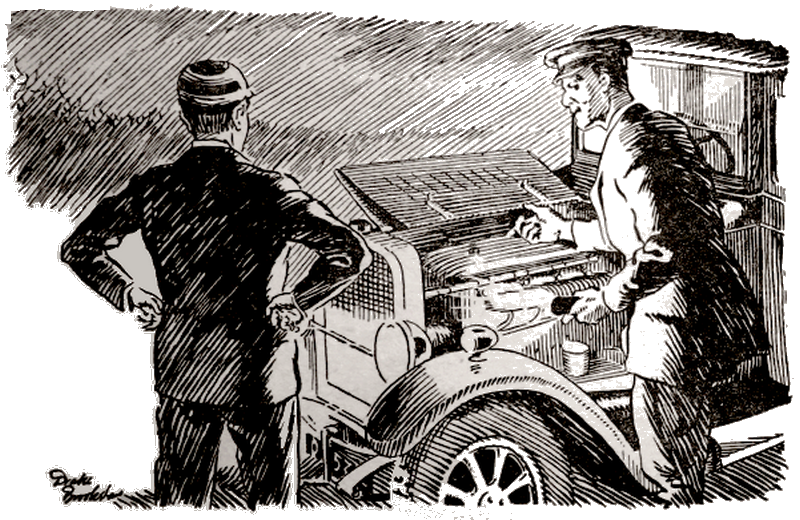

The railway connection with Stippleton was rather roundabout, so the Head put Ted into a taxi and the care of a reliable driver from the nearby garage. Though the driver was reliable enough, the taxi wasn't.

It broke down in desolate moorland country within five miles of Stippleton. The driver said he could put the car to rights—in two hours. But, as it was already late, Ted decided he would walk on into Stippleton. He knew the country well, as he had spent many an hour with the local Scouts scouring the moors.

The car broke down in desolate moorland country.

So while the driver tinkered with his car, Ted walked into Stippleton, called at a garage and sent a man to assist with the derelict car, and then went to the back door of Pitt House.

The shop front of Pitt House, his great-uncle's premises, was in the High Street, but the entrance to the warehouse and to Mrs. Agnew's kitchen quarters was in a back lane. Crummy flung open the door almost as soon as Ted touched the knocker. She was dressed all in black, and did not say a word.

"How's uncle, Crummy?" asked Ted anxiously.

The housekeeper put her handkerchief to her eyes, and one arm upon Ted's shoulder.

"Be brave, sonny," she said.

The boy looked at the black dress.

"Is uncle dead?"

"And buried," she replied.

The lawyer had said there was no need for the boy to come home till after the funeral when the will would be read. Barkin had warmly agreed with the lawyer, and, as there were no other relatives living, had acted as if Pitt House and everything connected with the late John Raymer were already his. Pitt House and the business were certainly his, but the small balance of money at the bank was willed to Ted—this much the lawyer had divulged.

"Did uncle leave any message for me?" said Ted, gulping down his grief. He couldn't pretend to great sorrow; his uncle had always been hard, severe, and miserly, and had shown no affection for the lonely boy.

"Your uncle never said one word, Master Ted, neither to Barkin nor to me," Mrs. Agnew answered. She ran to a corner cupboard unlocked the door, and brought out a square box. "But the day he took to his bed he gave me this box, saying if anything was to happen to him, I was to do as the label said. Look!"

Ted examined the shallow box which was about ten or twelve inches square, wrapped in brown paper, double-stringed and sealed with much wax. On it, in his great-uncle's bold handwriting were the words

"For Master Edward Raymer. To be secretly given into his hands in case of my death. Its existence is to be kept a profound secret from everyone else."

Ted took the box and placed in on the kitchen table; he feared to open it, wondering what might be inside. Crummy handed him a knife. Though she would not have dared to pry into her master's secrets, she was curious, and anxious to learn what awaited the boy of whom she was so fond. Anyone who knew John Raymer intimately, didn't expect him to plan pleasant surprises.

The string was cut in several places, the paper torn off, the lid of the box lifted, to reveal—a gramophone record packed in cotton wool!

There was a note enclosed: "Edward Raymer. For his ear only." That—and nothing more.

"I've some nice supper waiting," Ted heard Crummy say.

But he wasn't hungry and wanted to be alone to think out things and to hear what the record had to say.

"Where's the gramophone, Crummy?"

"In Master's study," she replied. "Though I haven't tidied up there as I should have done, only Mr. Barkin wouldn't let me. He's been nosing round the house ever since Master died as if he were seeking something."

"I'll go to the study, Crummy," said Ted, taking up his attaché case and the box of mystery left him by the dead man.

Crummy made the poor lad have a hot drink and some sandwiches.

"If you'll eat now, Master Ted, I can clear up and go to bed. You'll find your bed all aired and ready for you, sonny."

More to please Crummy than for any other reason, Ted had the refreshment, then, saying good-night, went to his late great-uncle's study.

It was an eerie job there in that room with its files of bills and stacks of price lists, with all the things that his great-uncle used—the faded green dressing-gown, his grey wig on a stand, everything just as the old man had left it when he had been taken ill. It was a strange room, centuries old, with its black oak beams across the low ceiling, and its big carven oak mantelpiece with quaint figures of gnomes and cherubs. There was that one-eyed goblin that had so fascinated him as a small child; it seemed to wink and grin at him in the flickering light as the fire flamed on the hearth.

He handled the eerie record of a dead man's words—words that no one except the speaker had yet heard. Ted hesitated, dreading what he might hear. Then he opened his attaché case and took out the record of the three maxims. He had brought the record with him, as he hadn't yet learnt the maxims for repetition to his uncle, who now would never hear them.

He placed the record on the gramophone. Following the preliminary winding there came his uncle's rasping voice:

"Maxim One. Honesty is the Best Policy. Maxim Two. He who seeks to get rich without working is a lazy nincompoop. Maxim Three. Ill-gotten gains are a curse to the getter."

It brought his great-uncle to life again. And at length he screwed up enough courage to learn what further advice Great-uncle John Raymer had to give him. He put the tragic disc of last words on the platform of the machine, and wound up. There was the preparatory whirring, and then came the harsh old voice through the silence of the study:

"If it should happen that I should die,

Seek the Goblin with only one eye."

That couplet and nothing else!

"Well! I'm jiggered," exclaimed Ted. "What the dickens does uncle mean? Have I to shut one eye and go seeking a goblin? Or is that wicked little fellow that has always winked at me from the mantelpiece the goblin of the poem?"

He heard the clock strike eleven. Then he heard Mrs. Agnew stumbling upstairs to bed. He listened intently as he thought he heard a distant door in the warehouse slam; yet Crummy had said she had done all the necessary locking-up.

He didn't move and continued to listen; it was an eerie old house with strange creakings of old timbers and scuttlings behind the wainscoting. Folks said that there was a Pitt House ghost, but Crummy had always told him that it was only foolish talk. Yet late at night and so soon after his great-uncle's death, Ted felt he might be forgiven for feeling funky. Suddenly he heard foot-steps. He was frightened but full of pluck. No one else slept in Pitt House except Crummy, and he had heard her retire. Besides these steps—and whispers—came from the next room where he and his uncle always used to have their meals—the principal living-room of Pitt House.

He switched off the electric light, and crept across the study to the door. Sounds of tappings, voices, stealthy footsteps. Very softly Ted turned the door handle at a moment when the tappings were loudest. With the door slightly ajar he caught snatches of conversation.

"The old miser has his hoard somewhere. You don't tell me he left only fifty pounds—that's all lawyer Wilkins can trace. "

It was Barkin speaking, Barkin who, though premises and business were willed to him, thought all his master's wealth should be his.

"Are yer sure Master hid some money in Pitt House, Mr. Barkin?"

The second voice was one that Ted quickly recognised as that of the chief porter who was Barkin's toady.

"The old miser hinted to me one day that he had money hidden, answered Barkin, "where no man could find it. And where liklier than in Pitt House, seeing he was seldom out of it? I mean to find that hoard before that nephew of his comes home. I've only a right to the bricks and mortar of Pitt House—the kid has the furnishings, and I don't mean the furnishings to include a pot of gold or a sheaf of securities."

"But you'll give I a share of the robbery, Mr. Barkin," said the porter.

"Hush! You shouldn't use that word. And you shan't have a cent if you don't swear to keep the promise you made to me. The old miser said—"

Ted lost the remainder of Barkin's remarks. The tapping of the walls of the ancient room drowned his whispered words. The next remark that Ted overheard was made by the porter who was getting nervous.

"Wonder Master can rest in his grave without his money. I shouldn't be surprised if his ghost do walk."

"Don't talk nonsense," said Barkin briskly. "When we've gone over this room, we'll try the study. The old miser must have a hidden safe or secret compartment somewhere."

And then Ted Raymer had a brilliant brain-wave.

Two guilty conspirators cautiously entered the study. Barkin's hand went to the switch, but no electric light shone forth. Ted had removed the bulbs from the two reading lamps on the study table.

"Mrs. Agnew been messing round cleaning up," explained Barkin. "Go and get those candles from the sideboard in the next room, Sam."

"I 'ope his ghost ain't walking," said the superstitious porter, teeth chattering.

"Don't be a fool," said Barkin with a tremor in his voice. "And hurry up with some lights."

There came faint rustlings—from the neighbourhood of the study chair where John Raymer had always sat!

Barkin stared with eyes that refused to credit what they saw. The light from the adjoining room cast strange shadows, and he almost thought he could make out the outline of his old master sitting there in his old green dressing-gown, leaning over the study table, his black skull-cap above his white wig. Eyes with pinholes of light gleamed out of a shrunken white face.

Barkin passed his hand over his face and said "Nonsense!" looking again, expecting the strange vision to have gone. The porter came with lighted candles into the study.

"Am—am—am I going mad?" asked Barkin, pointing to the study chair.

"Am—am—am I going mad?" asked Barkin, pointing to the study chair.

"Master's ghost!" gasped Sam, letting fall one candle and tightly gripping the second.

Both conspirators stood petrified. And then through the study rang the rasping voice that both of the two scamps knew well—the voice of a dead man.

"Maxim one. Honesty is the Best Policy."

"Yessir!" stuttered Sam, shaking so that candle grease splashed upon the carpet.

"Maxim Two. He who seeks to get rich without working is a lazy nincompoop."

"I've worked hard enough," a guilty Barkin exclaimed.

But the inexorable voice went on.

"Maxim Three. Ill-gotten gains are a curse to the getter."

But before the final words were reached two conscience-stricken scamps had taken to headlong flight—out from the dimly-lit study, through the lighted dining-room, down the staircase, by the private door into the warehouse, through the deserted shop, out into the cold midnight air.

Meantime the "ghost" had switched off the gramophone, taken his uncle's wig off his head, and flung aside his great-uncle's dressing-gown.

"If Barkin had been innocent of a dirty trick, he would never have been scared by my ghostly stunt," said Ted to himself. "His nasty thieving scheme made him a coward."

Ted replaced the globes on the reading lamps and switched on the electric light. He had yet to obey his dead relative's last command. "Seek the Goblin with only one eye".

Ted stepped over to the fireplace, and looked up at the carved work above his head. Yes, there was that grinning goblin with one staring eye—where the second should have been there was an impish hand carved by the sculptor. So lifelike was the carving that the imaginative boy could have sworn the goblin winked at him.

He could not reach the figure. He fetched a chair. On tiptoe he could touch the grinning face. Nothing happened.

"There must be a secret spring somewhere," Ted said to himself.

Then he ran for the ladder that was used to reach the topmost shelf of the bookcase. He placed the ladder against the mantelpiece carefully and climbed till he was level with that grinning goblin.

Ted pressed the one eye. There was a winding noise, then a panel slid back to reveal a metal-lined receptacle packed with—gold, Bank of England and Treasury Notes—the miser's hoard! The hoard that John Raymer wished Ted to have—or he would never have made that last record on the Baby Dictaphone.

So Great-uncle Raymer's present proved a handsome one after all.

Ted Raymer saw the family lawyer the next day, and the honest old man wanted to take proceedings against Barkin and the porter. But Ted, who was now a very wealthy fellow, begged the culprits off, and Barkin succeeded to the business as John Raymer had willed. What's more, Ted's generous treatment made a lifelong friend and a better man of Barkin.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.