RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

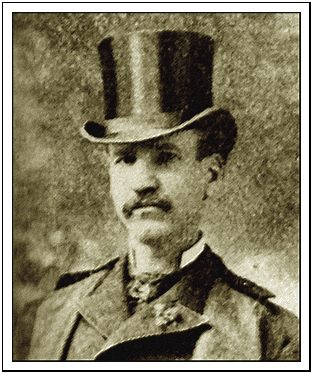

Robert Duncan Milne (1844-1899)

THE Scottish-born author Robert Duncan Milne, who lived and worked in San Fransisco, may be considered as one of the founding-fathers of modern science-fiction. He wrote 60-odd stories in this genre before his untimely death in a street accident in 1899, publishing them, for the most part, in The Argonaut and San Francisco Examiner.

In its report on Milne's demise (he was struck by a cable-car while in a state of inebriation) The San Fransico Call of 17 December 1899 summarised his life as follows:

"Mr. Milne was the son of the late Rev. George Gordon Milne, M.A., F.R.S.A., for forty years incumbent of St. James Episcopal Church, Cupar-Fife. and nephew of Duncan James Kay, Esq., of Drumpark, J.P. and D.L. of the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright, through which side of the house, and by maternal ancestry (through the Breadalbane family), he was lineally descended from King Robert the Bruce.

"He received his primary education at Trinity College, Glenalmond, where he distinguished himself by gaining first the Skinner scholarship, which he held for a period of three years; second, the Knox prize for Latin verse, the competition for which is open to a number of public echools in England and Ireland, and thirdly, the Buccleuch gold medal as senior and captain of the school, of the eleven of which he was also captain.

"From Glenalmond Mr. Milne proceeded to Oxford, where he further distinguished himself by taking honors, also rowing in his college eight and playing in its eleven.

"After leaving the university he decided to visit California, a country then beginning to be more talked about than ever, and he afterward made the Pacific Coast his residence. In 1874 Mr. Milne invented and exhibited in the Mechanics' Fair at San Francisco a working model of a new type of rotary steam engine, which was pronounced to be the wonder of the fair.

"While in California Mr. Milne for a long time gained distinction as a writer of short stories and verse which appeared in current periodicals. The character of his work was well defined by Mrs. Gertrude Atherton, who said:

"'He has an extravagant imagination, but under it is a reassuring and scientific mind. He takes such a premise as a comet falling into the sun, and works out a terribly realistic series of results: or he will invent a drama for Saturn which might well have grown out of that planet's conditions. His style is so good and so convincing that one is apt to lay down such a story as the former, with an anticipation of nightmare, if comets are hanging about. His sense of humor and literary taste will always stop him the right side of the grotesque.'"

A caricature showing Robert Duncan Milne and a San Francisco cable-car.

WHILE walking along Market Street the other day, I met my old friend, Ned Ainsworth, the artist, carefully attired, and with a natty air about him that argued recent residence in the East. It was only about three weeks, however, since I had seen him last in his studio here, his departure then having been sudden and urgent. And as the reason for this departure is closely connected with the events I am going to relate, it will be best to begin with what happened in Ainsworth's studio.

I had dropped in one afternoon to see what new subjects he had on hand, and was lounging in a chair talking to my friend at the easel about things in general, when there came a tap upon the door, and a keen-looking, middle-aged stranger entered.

"Pardon my intrusion, gentleman," he said, as he sat down; "I have called to see Mr. Ainsworth on a matter of business. Mr. Ainsworth, I presume?" as that gentleman turned inquiringly, mahl-stick in hand, and saluted his visitor.

"The business I am on is not professional—that is as far as you are concerned, Mr. Ainsworth," continued the stranger, in an explanatory manner; "the fact is, I am a detective," producing his credentials, "and have called to see whether you can give me any information, or put me in the way of getting any, regarding a young man who used to be, I understand, a particular friend of yours—a Mr. Luttrell—who has got into serious trouble in the East."

At the first part of the stranger's speech I had risen to go, not wishing to interfere with business which did not concern me, but at the mention of the name of Luttrell, I had turned half round, a movement which did not escape the quick eye of the detective.

"Perhaps this gentleman was an acquaintance of Mr. Luttrell's as well," he said, nodding in my direction; "if so, there is no necessity for him to move. He might be of assistance."

I again took a seat, wondering what was the matter.

"Mr. Luttrell—Mr. Hugh Luttrell," continued the detective, "age, twenty-seven or thereabouts—artist by profession—was, I understand, a partner in the business with you, Mr. Ainsworth, for some time during last year."

"Hardly a partner," replied Ainsworth, smiling; "he occupied this studio with me for several months last year, leaving in November last to join his folks in the East. They lived in Baltimore, I believe. I am heartily sorry he is in trouble, and shall be only too happy to do anything I can to help him out of it."

"What I came more especially for," went on the officers, "was to find out whether he had left any papers or letters behind him which might serve to throw some light upon subsequent events. Did you, Mr. Ainsworth, or this gentleman here," motioning to me, "have any reason to suppose that he was not on the best of terms with his relatives in the East—that he had quarreled with them, or anything of that sort?"

"Luttrell was always very reticent about his private affairs," returned Ainsworth, thoughtfully; "he sometimes spoke very bitterly about the injustice with which he thought he was treated by his friends. From what I could gather they were very wealthy, but did not wish him to devote himself to art. There was, also, some love affair, I believe, at the bottom of it—what, I never cared to inquire into. By the way," he added, "when he left here, which he did rather hurriedly, he left behind him a small writing-desk, which may, or may not, contain something of value. That is it over there on the table in the corner. But you have not told us yet the nature of the trouble our friend has got into."

"I am surprised you have not heard of it," said the detective; "it was the sensation of the hour in Baltimore. It was mentioned in your daily papers, too. I got a file of one of them this morning, as I came along, out of curiosity, and clipped this from it," handing us a clipping from the telegraphic columns of the Call, which read as follows:

Baltimore, December 27th. At half-past twelve this afternoon, the body of Louis Latreille, the well-known merchant, was found lying foully murdered in the studio of Frederick Hollis, artist, in Walsh's Building. The unfortunate gentleman had been stabbed to the heart, the weapon used being a dagger belonging to his nephew Hugh, upon whom suspicion rests as being the author of the atrocious deed. The supposed criminal is now under arrest.

"Good heavens!" exclaimed Ainsworth; "but this is Latreille, and my friend's name is Luttrell."

"He changed his name while he was here," explained the detective; "that possibly accounts for your not having taken more notice of the dispatch."

"It was about New Year time, too," I remarked, "which accounts for the meagreness of the dispatch. At any other time we should have had a column of description. But I am amazed—staggered—at the bare idea of Luttrell having a hand in any such thing as this."

"So quiet, so inoffensive, as he was," added Ainsworth; "no, no; I can't believe it. There must be some terrible mistake somewhere."

"Unfortunately," said the detective, gravely, "appearances are dead against him. The circumstantial evidence is overwhelming. There is no link missing except actual witnesses to the deed. I am sorry for him, and believe as others do, that the deed was done in a fit of passion. Instances where the whole nature is changed in a moment are not uncommon. The defense will be, I understand, temporary insanity from ungovernable passion, though the accused man stoutly maintains his innocence. But let me see whether there is anything in that desk bearing upon the case," and the officer moved over to the table.

The lock was easily forced, and some receipted bills, memoranda, and letters were found inside. The letter the detective took possession of and proceeded to open and read, pointing out to us, at the same time, that the name upon the envelopes was spelled "Latreille." After he had finished his scrutiny, he said that the contents of one of the letters had considerable bearing on the case, as showing the relations existing between our friend and his uncle. It was a letter from the latter, and ran as follows:

Baltimore, November 24, 1888.

My Dear Hugh:

I hope that you have, by this time, come to the conclusion that you have made a sufficient fool of yourself, and that you are at last prepared to accept the counsel of older and more experienced heads in the shaping of your future course. I can only reiterate what I have all along said, that you are throwing away all your chances in continuing to keep the course you have taken. You affect to treat business and a commercial life with disdain, and consider that what you please to call "art" is the only thing worth living for. Where would I have been, I should like to know, if I had entertained the same ideas? What made me what I am, and gained for me the property I have acquired, if it was not the desk and the counting-house which you affect to despise?

It has simply been for the purpose, as you know, of weaning you from habits and ways of life which, if persisted in, must inevitably lead to your moral and social ruin, that I have, for the last six months, cut off your allowance, and thrown you on your own resources. You have by this time, no doubt, found out the difference between comfort and affluence, with five hundred dollars a month pocket-money, and starving upon the proceeds of such pictures as you can paint, if you can find any fools to buy them.

Rachel inquires after you most affectionately every time I meet her. That property must be worth considerably over a million by this time. That is another chance you are throwing away by your criminal neglect and absence.

I have decided, however, to give you one more chance, and, on the presumption that you have by this time come to your senses, I inclose check for two hundred dollars, which will be sufficient to bring you back, as otherwise I am convinced you could not come.

I rely on your honor to use the money for this and no other purpose, and if you do not choose to come at once, I look to you to return the money.

Your affectionate uncle,

Louis Latreille.

"There!" said the detective, with a satisfied air, when he had finished reading; "that explains the relations existing between the young man and his uncle. He returned to Baltimore soon after the receipt of that letter, but soon fell into his old ways, associating with artists—I beg your pardon, gentleman, no offense meant—in defiance of the express wishes of his nearest relative. The theory is, that goaded to desperation by the threat of his uncle—we have evidence to prove this—to cut him off completely and have nothing more to do with him, in a fit of blind rage, he killed him. This letter is important, and will be introduced at the trial."

"Would you mind giving us some account of the tragedy?" said Ainsworth; "you must remember that, beyond the mere statement that Luttrell, or Latreille, killed his uncle, we have nothing of the facts of the case."

"Willingly," returned the officer, "but it must be brief. It is now two," looking at his watch, "and I have something to do before I catch the three-thirty East. To begin, then, it transpired that, within a week or so after his return, the young man was a constant visitor at the studio of an artist called Hollis, the place where the murder afterward occurred. This, at length, came to the ears of the old man, who became naturally indignant at his nephew again setting his will at defiance, and, on the day of the murder, he went up there, as events showed, to take him to task. The studio is located on the top floor of a large business block, the rooms and offices in which open upon corridors running round three sides of the building, and are occupied by doctors, lawyers, architects, artists, and professional men generally. Many of these rooms are en suite, opening upon each other by doors, which, if the rooms are used singly as offices, as many of them are, are, of course, kept locked. This, however, does not prevent the sound of conversation, if conducted in a moderately high key, from being heard through the thin wood-work of the doors leading into adjoining rooms, and it was owing to this fact that we were enabled to fix the crime upon the proper shoulders. The studio of the artist Hollis was the middle one of three rooms opening on each other en suite, the doors between them being locked. The room to the left of the studio was occupied by a shirt-maker named Wells, and that on the right by a model-maker named Raymond. After the alarm was given—which was at twelve- thirty o'clock—that a man had been found dead in Hollis's studio, I was quickly on the spot, having been detailed for the job, and my first move was to hear the statements of the discoverers of the body—Mr. Hollis, the proprietor of the studio, and a lady named Morgan, who was on the way to visit a manicure upon the same floor, and had come up in the elevator at the same time as Hollis, and passing his door a little behind him, was startled to hear him cry out, and looking into the studio, to find out what the matter was, became an involuntary witness of the discovery of the murder. The body of the murdered man had been found lying on its back on the carpet, which was literally soaked with the blood that had flowed from a dagger- wound in the region of the heart. The fact that no weapon was found near precluded the idea of suicide.

"The next thing I did was to search the room thoroughly, thinking that it was possible that the perpetrator of the deed might have secreted the weapon he used somewhere about the premises, to obviate the risk of its being found upon him afterward. After turning over the queer odds and ends and properties of which artists' studios are usually full, I at last came upon a weapon, some fresh clots of blood on which convinced me that I had lit upon what I was in search of. It was a dagger, or poniard, with a blade about a foot long—just such a weapon as would have made the wound in the breast of the murdered man. Mr. Hollis gave vent to a cry of surprise as I brought it out.

"'Why,' said he, 'that is Hugh Latreille's dagger!'

"'Did he usually carry it about him?' I asked.

"Not usually,' he said, 'though sometimes he did. He prized it greatly as a specimen of the antique, on account of its rare workmanship.'

"'Did he have it on him when you saw him last?' I asked. 'When did you see him last?'

"'Why, I left him here not an hour ago,' he replied, 'while I stepped out for lunch. The dagger was lying on that table then. There is its sheath,' pointing to a curiously worked metal- scabbard upon a table close by.

"'Do you recollect what time it was when you went out to lunch?' I continued.

"'Exactly twelve,' he replied; 'I asked Hugh to wait till I returned. My God! I wish he was here now.'

"'So do I,' I answered; T should very much like to see him.'

"You must remember that at this time I only knew the Latreilles by sight, and did not know their relations till afterwards.

"My next step was to make inquiries of the occupants of the adjoining rooms. I tried the floor of the mode-maker's on the other side of the studio. The door also was locked, but while I stood there the tenant, Wells—the shirt-maker—came along and unlocked it.

"'You have heard the news, of course?' I remarked, as we entered.

"'Yes,' said he, 'I got it from the elevator-boy as I came up. A terrible piece of business!'

"'My name is Brown, of the detective force,' I said, 'and I want to know if you can tell me anything that may throw light on the matter. How long have you been absent from your office?'

"'I went out to lunch,' answered Wells, 'at a quarter-past twelve o'clock. I usually leave my assistant here when I am out, in case customers call. To-day he had some business to attend to, else the door would not have been locked.'

"'Did you hear any noise in the studio, before you went out? Anything that would lead you to suspect that all was not going on right within?'

"'Yes,' said the man, gravely, T certainly did, and in view of what has happened, I think that what I heard has a most important bearing on this case. My assistant heard it too—ah! here he comes now himself. We will gladly tell you all we know about the matter.'

"I asked Mr. Wells to state everything fully and unreservedly, and this is in effect what he told me. He said that, although the sound of talking in the studio could be heard pretty distinctly through the door, he never paid any attention to it. Mr. Hollis was a very quiet man, and so, as a rule, were the friends who came to see him. That morning, however, was an exception to the general rule. A few minutes past twelve, somebody entered the studio and began talking in a loud, dictatorial tone of voice. The voice, he judged, was that of an elderly man. Another voice spoke in answer, that of a younger man. It was a voice which had only recently been heard by him in the studio. The argument grew heated and even quarrelsome. Mr. Wells and his assistant grew interested and listened. This was what they heard:

"'Very well, sir,' said the older voice, 'take your own way. I wash my hands of you and your business now and forever.'

"'And I, sir,' answered the younger voice, 'say that I will not submit to be dictated to any longer by you or anybody else. It is simply unbearable, and I will not stand it.'

"'You need never look to me for a single dollar now or hereafter. You shall not touch a cent of my property,' went on the older voice, in tones inflamed with passion.

"'Money is not the only thing in life,' replied the younger voice, with equal vehemence; 'you may regret your action hereafter when it is too late.'

"At this point there was a pause in the conversation, and as there seemed to be no signs of any overt quarreling, Mr. Wells and his assistant went out.

"My next point was to find the nephew. If he was really the criminal, the chances were that he would try to escape. I accordingly telephoned instructions to the central station and to the railroad depots to look out for a man answering the description of Hugh Latreille. In this, I was successful, as he was apprehended just as he was boarding the New York express. The arresting officer had been instructed not to tell him the reason for his detention before I saw him myself, which I did shortly after at the police station. When I told him who I was, he demanded to know whether his arrest had not been made at the instance of his uncle, remarking that it was a wanton outrage on his personal liberty.

"'Do you wish to know the cause of your arrest?' said I; 'your uncle was found in Hollis's studio, an hour ago, murdered. Your dagger did the deed. You are known to have been in the studio about that time, engaged in a heated discussion with Mr. Latreille. It is no use to deny it, as every word was heard by the shirt-maker next door. What have you to say to this?'

"'Good God!' exclaimed the young man, turning pale and staggering back against a bench for support; 'my uncle murdered! With my dagger! In the studio!'

"He sank back and covered his face with his hands. I was forced to confess that if the young fellow was guilty, he was an adept in the art of dissimulation.

"'Yes,' said I, 'appearances are strongly against you. I have no choice but to book you on a charge of murder. You will have an opportunity to clear yourself before the coroner.'

"Returning to Walsh's Building, to see whether I could pick up any more clues, I now found the door of the model-maker's room, to the right of the studio, open, but no one within. The room was full of the usual paraphernalia, models, tools, and what not, belonging to the trade. The next moment the janitor of the building entered, and told me that the tenant, Mr. Raymond, who was an inventor as well as a model-maker, and a man of considerable means, had left that forenoon, after handing him the keys of the office, with the injunction to keep everything in order till his return, which he hinted might be a week or two, or even a month or two, later.

"At the coroner's inquest, which was held next day, the witnesses, besides myself, who testified were: Mr. Hollis, the artist, and Mrs. Morgan, a widow lady of means, who were the first to discover the body; Mr. Wells, the shirt-maker, and his assistant, who testified substantially to what I have already said; and the elevator-boy and janitor. The last named gave some new evidence of a peculiar character. He testified that he was sweeping on the top corridor about the time the murder must have taken place. From where he was working he could see the door of the studio. Many people were in the corridor, passing to and from the elevator and stairs during the noon hour. He recollected seeing the prisoner come out of the studio, closing the door behind him, and walk hastily to the elevator. He thought nothing of it at the time, as he knew he was a friend of the tenant. About five minutes afterwards he saw a lady walking from the same direction. She looked like the lady, Mrs. Morgan, who had just testified. He did not know whether she had come from the studio or not. The reason that he noticed her was because there had been no one else in the corridor for several minutes. He could not swear positively whether it was Mrs. Morgan or not. The elevator- boy testified that the prisoner had gone down with him to the ground floor about a quarter-past twelve, in a very excited condition. About ten minutes later, Mr. Hollis and Mrs. Morgan entered the elevator together, and ascended to the top floor. He was positive he had not seen the lady earlier in the day, though she frequently used the elevator to go to the top story.

"Mrs. Morgan testified to being a witness to the discovery of the body while she was on her way to see a lady manicure, who had an office on the same floor, testimony which was corroborated by the manicure, who was present. In a reply to a question as to whether she had known the deceased, Mrs. Morgan said, in a somewhat embarrassed manner, that she had had some business transactions with him on one or two occasions about some property.

"The prisoner admitted the conversation between his uncle and himself, as stated by Mr. Wells, but said that he had left the room a few moments later, leaving his uncle behind him, seated at a table. The dagger was lying unsheathed upon the table when he left. He again loudly protested his innocence. The jury returned a verdict in accordance with the evidence, and young Latreille was committed, without bail, to answer the charge of murder. The trial begins next week. And now, gentleman, you know as much about the case as I do. It is getting near the time the train starts, so I must bid you good-by."

"WHAT do you think of that?" I asked, when the officer had

gone.

"I can not believe in Luttrell's guilt," returned Ainsworth, moodily, shaking his head; "I am firmly convinced of his innocence, and think I could help him if I was there. Yes," he added, after a pause, "I will go. I have been thinking for some time past of taking a trip East. I have several pictures I think I could find a better market for there than here."

Two days afterward, Ainsworth took passage for New York. That was about three weeks ago. Accordingly, when I met him upon the street a day or two ago, I was naturally anxious to know the outcome of his friend Luttrell's case, that being the main reason for his journey.

"Come along," he said, in answer to my inquiries, "and I will tell you all about it. After arranging about my pictures in New York," he went on, after we had settled down comfortably in his studio, "I went on to Baltimore, and the first thing I did was to call upon Luttrell—Latreille, I should say—at the prison. He was wonderfully changed and terribly cut up, and small marvel, considering the terrible accusation against him and his long confinement in prison. He was delighted to see me, however, and said, now that I had come, he had a premonition that everything would turn out all right and his innocence be proved. It wanted two days yet to the date set for his trial, and during these two days I set to work with a will to try whether I could secure any new evidence bearing on the case. My efforts, however, were unavailing, and with the exception of one circumstance which had been unearthed by defendant's counsel, and the relevancy of which to the matter in hand it was hard to trace, there was absolutely nothing new. This was a pencil entry in a memorandum- book, found in one of the pockets of the murdered man—evidently the last entry he had made. It was worded thus:"

(Draft of Letter to Emma.)

Dear Emma:

You have broken your word with me, and henceforward our relations must cease. I have left orders at the bank not to honor any more of your drafts. You perfectly know the reason why. This is final. If you annoy me further, you will regret it.

L. Latreille.

"'Now,' said the attorney, referring to the memorandum-book, as we sat in his office the day before the trial, 'I thought there might be something in this, so I determined to find out who this "Emma" was. I went to the bank where Mr. Latreille kept his account, and laid the matter before the officials. I then ascertained that, for some years past, the bank had honored monthly drafts drawn upon Mr. Latreille by a female signing the name "Emma Stanley." These drafts had been sent for collection by a New York bank until a day or two before Mr. Latreille's death, when that gentleman had given the bank instructions to honor no more of them. However, I prevailed on the bank to let me have one or two of the drafts bearing this lady's signature. One never knows what may turn up.'

"Well, the next day the trial began, Hugh pleading not guilty. The evidence brought forward was, in all the main points, the same as came out at the coroner's inquest. Wells, the shirt- maker, swore that one of the voices he heard in the studio on the day of the murder was that of the prisoner. The testimony of the artist, Hollis, and Mrs. Morgan, regarding the finding of the body, and that of the elevator-boy and the janitor regarding the people who were about at the time, was gone over again without evolving anything new.

"'Mrs. Morgan, please take the stand again,' said Hugh's counsel when all the evidence was in.

"That lady complied.

"'You say that you had some business relations with the late Mr. Latreille? May I ask the nature of these relations?'

"'Certainly,' replied the lady; 'Mr. Latreille paid me a certain sum monthly on account of some property I had assigned to him several years ago.'

"'How did you receive these monthly sums?' queried the attorney.

"'I drew for the money on Mr. Latreille's bank,' said the lady.

"'How did you sign the draft?'

"'Emma Stanley,' replied the lady, after an instant's hesitation; 'Stanley was my name at the time I disposed of the property to Mr. Latreille.'

"'That will do," said the lawyer; then, leaning over, he whispered in my ear.

"'What can one do? Her answers are perfectly straight- forward—there is no attempt at concealment, and yet—I can't help thinking there is a mystery somewhere.'

"Then the usual speeches were made by the counsel on both sides, ending up with the prosecuting-attorney. In reviewing the evidence, he said that though it was wholly circumstantial it was of the strongest nature. The murder must have been committed between a quarter-past twelve, when Mr. Wells, the shirt-maker, left his room, and half-past twelve, when the body was found. No other person had been seen to enter or leave the studio by the janitor, who was on the spot, during that time, except the prisoner. Who but the prisoner had any motive for the act? And what was the prisoner's motive? The gratification of revenge for the fancied injury done him by his uncle in thwarting his desires. The deed was evidently prompted by blind passion upon the impulse of the moment. The dagger was lying handy on the table at the moment, and it became a ready instrument in the hands of the murderer. Then the attempt to conceal the evidence of guilt by hiding the weapon in the studio, the hurried exit from the building, and the capture just as the prisoner was about to escape from the city, perhaps to some foreign land—all these are links in the chain of evidence, tending to fasten the crime more and more closely upon the prisoner at the bar. He concluded with an appeal to the jury to be guided by the cumulative weight of the evidence.

"The judge then proceeded to deliver his charge, which I could see at the outset was unfavorable to the prisoner. He was just beginning his peroration, when a messenger handed Hugh's counsel a letter. As he read it, I could see his cheek flush and his eye dilate. All of a sudden he started to his feet.

"'If your honor please,' he said, 'I have just received news that some most important and wholly unlooked-for evidence will be introduced tending to put a totally new aspect on the conduct of this case. I ask your honor for a stay of proceedings till the new witness can be produced. This letter says that he may be expected at any moment.'

"The judge frowned, and the attorneys for the prosecution wore an air of surprise.

"'Who is this witness?' asked the judge; 'and why did he not appear before?'

"'Mr. Raymond, if it please your honor,' replied our counsel, 'the tenant of the other room next Mr. Hollis's studio. He has been abroad for several months, and only returned last night He left on the day of the murder.'

"'But it was proved,' said the judge, 'that Mr. Raymond left this city on the twelve-o'clock train for New York. That was testified to by several of the railroad officials at the depot, as well as by the janitor to whom he gave the keys of his office. How can he possibly be possessed of any direct evidence of value in this case?'

"'Nevertheless, I hope your honor will hear what he has to say—ah! here he comes,' said our counsel cheerily, as Mr. Raymond entered, bearing an oblong, wooden box in his arms, and made his way to the witness-stand.

"'Mr. Raymond, please take the stand,' said our counsel; 'now tell us what you know of this case.'

"'Gentlemen,' said Mr. Raymond, 'I only got back from Europe last night, and, on visiting my work-shop, which adjoins Mr. Hollis's studio, this morning, I found everything in pretty much the same shape as I had left it. I am, as you perhaps know, a model-maker and inventor, and at the time of my departure I was engaged upon some experiments in connection with the phonograph. I found the instrument in the same place I left it about six months ago, that is to say, on a table right alongside of the door which separates me from Mr. Hollis's studio. The receiving cone was in position, and simply with the object of seeing whether everything was in working order, I set the clock-work which controls it in motion—I should say that I am experimenting on a new wax cylinder of my own, with a clock-work motion. In about a minute afterwards I was surprised to hear the sound of voices issuing from the cone. I then recollected that, in the hurry of departure, I had forgotten to throw the motor power out of gear, and that, consequently, the words I was then listening to must have been spoken within hearing range of the phonograph after my departure. I had, of course, heard of the tragedy which was enacted in Mr. Hollis's studio the day of my departure, but it was a minute or so before I began to connect the sounds issuing from the instrument with that event. Presently, however, I became convinced that this was really the case. I drank in everything which the phonograph said, and, when it ran down, I turned the machinery back, and heard it all over again to make sure. I have brought the instrument along so that it may speak for itself. Though you can't swear it, you can swear by it, for the phonograph is the George Washington of science—it can not tell a lie.'

"Mr. Raymond then proceeded to open the box and take out the instrument, but counsel were on their feet in a moment arguing against the admissibility of the evidence. Such a monstrous and unheard-of innovation, they said, had never been suggested before. The judge, however, happened to be a man of science as well as sense, and he ruled that the evidence of the phonograph should be heard by the jury, without prejudice to the case. If the jury considered that what they heard, through the medium of this infallible sound-recorder, had a real bearing on the case, and if there was unmistakable evidence of this, then let them give it the weight to which it was entitle. If not, then the case would rest upon the present evidence.

"The instrument was then set upon a table in front of the jury-box, and Mr. Raymond set the works in motion. The metallic cone, which both gathers and emits sound, according as the instrument is used to transcribe or reproduce, was placed in position, and judge, counsel, and jurors drew close to hear what would transpire. Mr. Hollis, Mrs. Morgan, the other witnesses, and myself, gathered round from interest and curiosity. The scene was a strange one in a court of justice. Presently a voice issued from the cone, in somewhat of a smothered key, just as if it had been heard through a door, but distinct enough to permit of each word being recognized.

"'Well, uncle, how do you do, this morning?' said the voice, which we in the court-room instantly recognized as that of Hugh Latreille, the prisoner.

"'You're here again, I see,' answered a gruff voice, and I heard one juror whisper to another, 'That's old Latreille speaking, by God!'

"'Very well, sir, take your own way,' went on the same voice; 'I wash my hands of you and your business now and forever.'

"'And I, sir,' said the voice of Hugh, 'say that I will not submit to be dictated to any longer by you or anybody else. It is simply unbearable and I will not stand it.'

"'You need never look to me for a single dollar,' said the other voice, 'now or hereafter. You shall not touch a cent of my property.'

"Money is not the only thing in life,' went on the instrument in Hugh's voice; 'you may regret your action when it is too late.'

"Then there was a pause of perhaps a minute, during which the wax cylinder of the photograph continued to revolve but no sound was emitted. The jury and other listeners were visibly impressed by the similarity of what they had just heard to the testimony of Wells, the shirt-maker, as well as by the exact reproduction of the voices of Hugh and his uncle, in all their peculiarities of accent and pitch. Most of them had never heard, scarcely even heard of, a phonograph before, and looked on with feelings akin to awe.

"'Good-by, uncle,' suddenly issued from the instrument in Hugh's voice; 'you won't see me again for some time.'

"Then a noise followed like the slamming of a door, for the phonograph reproduces every sound, simple or composite, made within hearing distance of its receiving cone.

"Then there was another pause of about a couple of minutes, Mr. Raymond explaining to the jury that the instrument is an infallible register of time as well.

"'What! you here, Emma,' suddenly issued from the cone. It was old Latreille's voice talking in a startled and excited key.

"'Yes, I'm here,' answered a female voice in a hard, metallic key; 'I got your letter saying my drafts had been stopped. I found it was the case. What do you mean by it?'

"'I mean what I have said,' replied Latreille's voice in a rising key; 'I have positive information of the new connection you have formed, and I decline to support you any longer.'

"'Do you really mean this? Have a care!" continued the female voice in the same cold, hard key.

"Meanwhile all eyes had turned mechanically toward Mrs. Morgan, who was one of the crowd surrounding the instrument. It was the voice of this woman, accent for accent, key for key, that was issuing from the phonograph, and it was plain that every one recognized it as I did myself. Her face was as white as a sheet, her lips set, and she clung to the railing of the jury-box for support.

"'My purpose is irrevocable,' went on Latreille's voice; 'if you dare to annoy me I will—' the voice paused.

"'You will—' repeated the female voice, threateningly.

"'Use my knowledge about the Stanley case. It will be the penitentiary for life—if not the gallows.'

"'Curse you! Take that—and that!" said the woman's voice in tones that made the blood run cold.

"This was followed by a stifled groan, and a sound as of a heavy body falling to the floor.

"At the same time a piercing shriek rang through the courtroom. Mrs. Morgan threw her arms aloft into the air and fell heavily forward. The utmost confusion prevailed, during which the court adjourned till the following morning.

"Meantime, the judge consulted his colleagues of the bench as to the admissibility of the phonograph as a witness. What decision was come to I know not, as Mrs. Morgan confessed. She had, it seems, ascended the stairs on the eventful forenoon to visit her manicure, and accidentally seeing Mr. Latreille through the door of the studio as Hugh was coming out, entered to reproach him about stopping her drafts. Goaded to desperation by his behavior, she had, in a fit of momentary madness, stabbed him with Hugh's dagger which was lying naked within reach. She had then, after concealing the weapon, descended the stairs, and re- ascended immediately after in the elevator with Mr. Hollis, and, by seeming to have discovered the body, effectually diverted suspicion from herself. Further investigation went to show that she had held the relation of mistress to Latreille. I understand that since the confession she has become hopelessly insane. Of course Hugh received the profuse congratulations of his friends, and, as his uncle's heir, can now indulge his artistic tastes without let or hindrance. In the fervor of his heart, after liberation, he wrote a characteristic letter to Edison expressing unbounded gratitude for that distinguished scientist's last invention having been the means of saving his life."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.