RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

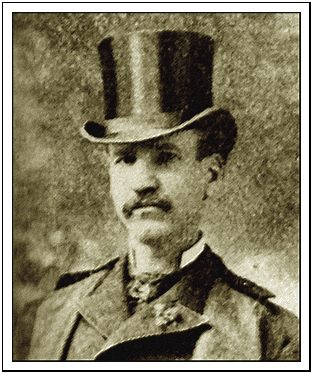

Robert Duncan Milne (1844-1899)

THE Scottish-born author Robert Duncan Milne, who lived and worked in San Fransisco, may be considered as one of the founding-fathers of modern science-fiction. He wrote 60-odd stories in this genre before his untimely death in a street accident in 1899, publishing them, for the most part, in The Argonaut and San Francisco Examiner.

In its report on Milne's demise (he was struck by a cable-car while in a state of inebriation) The San Fransico Call of 17 December 1899 summarised his life as follows:

"Mr. Milne was the son of the late Rev. George Gordon Milne, M.A., F.R.S.A., for forty years incumbent of St. James Episcopal Church, Cupar-Fife. and nephew of Duncan James Kay, Esq., of Drumpark, J.P. and D.L. of the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright, through which side of the house, and by maternal ancestry (through the Breadalbane family), he was lineally descended from King Robert the Bruce.

"He received his primary education at Trinity College, Glenalmond, where he distinguished himself by gaining first the Skinner scholarship, which he held for a period of three years; second, the Knox prize for Latin verse, the competition for which is open to a number of public echools in England and Ireland, and thirdly, the Buccleuch gold medal as senior and captain of the school, of the eleven of which he was also captain.

"From Glenalmond Mr. Milne proceeded to Oxford, where he further distinguished himself by taking honors, also rowing in his college eight and playing in its eleven.

"After leaving the university he decided to visit California, a country then beginning to be more talked about than ever, and he afterward made the Pacific Coast his residence. In 1874 Mr. Milne invented and exhibited in the Mechanics' Fair at San Francisco a working model of a new type of rotary steam engine, which was pronounced to be the wonder of the fair.

"While in California Mr. Milne for a long time gained distinction as a writer of short stories and verse which appeared in current periodicals. The character of his work was well defined by Mrs. Gertrude Atherton, who said:

"'He has an extravagant imagination, but under it is a reassuring and scientific mind. He takes such a premise as a comet falling into the sun, and works out a terribly realistic series of results: or he will invent a drama for Saturn which might well have grown out of that planet's conditions. His style is so good and so convincing that one is apt to lay down such a story as the former, with an anticipation of nightmare, if comets are hanging about. His sense of humor and literary taste will always stop him the right side of the grotesque.'"

A caricature showing Robert Duncan Milne and a San Francisco cable-car.

"THE schooner Aileen, just returned from the Bay of Papua with a cargo of nutmegs and massay bark, reports having sighted an extraordinary monster in the swamps which line the eastern shore of the bay. It was plainly visible at a distance of four miles from the spot where the schooner was lying off, breaking and tearing its way through the camphor-trees and sago palms with, as Captain Biggs describes it, the same ease 'as a pig through a potato patch.' The captain says that, judging from its appearance at that distance, it cannot have been less than from eighty to a hundred feet in length. He says that sometimes it would rise on its hind legs, and that then its head would stand far clear of the tops of the palm-trees. He examined it through his glass, and says that he never saw any animal like it, but compares it most nearly to a bear in general characteristics. Captain Biggs is a sober, reliable man, not much given to 'yarning,' and, as the circumstance is attested by his crew of six, we offer no comment. Here is a chance for our local Nimrods."—Brisbane Courier, January 6, 1882.

THE above paragraph, taken from a Queensland (Australia) paper

of a recent date, sent me by a friend, attracted my attention

when I read it to the extent of my exclaiming, "Bah! have these

sea-serpents and boojum-snarks begun to attack the hard-headed

Australians with their leaven? Well!" And the next minute it

passed from my memory. I should probably never again have thought

of it, had not a singular circumstance brought it to the surface,

and given it sufficient importance in my eyes to make it the

text, as it were, of the following narrative.

THE other morning I happened to stroll casually into the

Mercantile Library, on Bush Street, and noting several ladies

coming up from the basement, curiosity prompted me to find out

what was going on there. On entering the hall I found that it had

been converted into a species of museum, full of specimens of the

animal and mineral kingdoms, many of them so deftly imitated and

so preternaturally natural as to deceive, if it were possible,

even one of the elect, biologically speaking. Bones of long-

vanished animals were grouped on the floor; tusks of astounding

development, purporting to be facsimiles of originals in European

galleries, lay beside them. In the centre of a railed enclosure

towered a monstrous and gigantic elephant, which a placard

announced to be an exact reproduction of the mammoth which was

found embedded in the ice of the river Lena, where its crystal

coffin bad preserved it intact for who shall say how many

thousand years? A creature twenty-six feet long by sixteen high

is worthy of more than a passing glance, and I stood examining

the pillar-like legs, the shaggy hide, and the enormous tusks,

and calculating whether or not the original of the massive hulk

would have tipped the beam at a hundred tons, when I was aroused

from my reverie by a voice at my side:

"A purty big beast, sir; but I seen bigger."

Mechanically I turned and inspected the speaker. A bronzed, bearded, and weather-beaten man of, I should say, about fifty, dressed in sailor fashion, leaned carelessly against the railing, and looked up at the mammoth.

"You've seen bigger? Ah!" I repeated in a preoccupied way, catching vaguely, at first, the purport of the remark.

"Yes," said the man, with rather more emphasis, "I seen bigger. An' what's more, ten times bigger. Why, that there mammot' ain't a patch on the beast I once seen. It was purty near's big's that when it was a babby."

I now turned and faced the man square.

"Look here, my friend," I said, "I don't know what you take me for, but I can assure you that there is very little use in spinning yarns of that sort to me. I flatter myself that I have too much knowledge of natural history, and the laws regulating the development of animal life upon the surface of our planet, to give them credence." And after delivering myself of this announcement, I paused to witness its effect. There was no effect. The man merely looked me in the face and said:

"I can see you're a man of eddication, sir, an' a better scholar, an' has more book larnin', no doubt, than me; but I tell you, jest as sure as you're a-stan'in' there, that I'm speakin' the pure truth when I say I seen a beast ten times as big's that there mammot', an' I was at the hatchin' of it, too."

I looked at the man closely and critically to detect, if possible, what object he could have in playing upon my credulity, but I could gather nothing from his frank countenance and apparent sincerity of expression. I determined, therefore, to seem to acquiesce, and draw him out.

"And, pray, in what part of the world did this strange creature live?" I asked.

"In Papua, or, as some calls it, New Guinea—a big island lyin' to nor'ward of Australey; maybe ye've heerd of it. An' for all I know the beast's there yet," replied the man.

SUDDENLY there flashed across my mind the remembrance of the

paragraph in the Australian paper, just quoted, and I could not

help connecting it with this man's assertion. Was it possible,

thought I, that there might be some germ of truth in these

strange and fanciful story of uncouth and gigantic creatures in

out-of-the-way wilds where men's foot-steps rarely tread? Was it

possible that under certain peculiar conditions and rare auspices

some stray specimen of long extinct races might yet survive?

Utterly improbable as the idea might seem, I was yet bound to

confess that it was neither logically nor naturally impossible,

and I determined to hear what this man might have to say, and

derive, if nothing else, perhaps amusement from his story.

Inquiry elicited the fact that Captain Sebright (he is now engaged as a pilot on the bay) resided on Jessie Street, and I accepted an invitation to call upon him the same evening, and hear his story, besides examining some documents in his possession which bore upon the subject.

During the course of the day I met my friend W——, one of the shining lights of the Academy of Sciences, and persuaded him to accompany me on my evening visit, though at the expense of a smile of pity and superiority. We accordingly called on the captain, and, after the usual preliminaries, our host entered upon his narrative as follows:

"I DON'T know if ye was ever in the South Seas, gen'lmen, but

atween you an' me, there's more room for queer things there than

any part o' the airth ever I was on. Talk o' yer

vegetation, yer trees, yer funny birds, yer rummy beasts, I can

bet that ye won't find the like nowhere elst, nohow. But the

queerest thing ever I see in the beast line, I seen on the island

of Papua. If ye got the time I'll tell ye how it was, an' then, I

reckon, yell think the same's I do. It's jest sixteen years ago,

mebbe a little more or less, that I shipped afore the mast on the

barkentine Mary Chester from Wellington, New Zealand, with

a cargo of coal for Singapore. It was in the month of October,

an' the cap'n he took the north passage by way of Torres Straits.

Well, we gets along all right as far's Cape Rodney, when a

typhoon struck us, an' afore we could shift our canvas, we was on

our beam-ends an' a-swimmin' for our lives. One o' the boats got

loose in the upset, an' me an' Ben Baxter, the bo'sun, clumb into

her, an' arter we was in we helped Mister Ince, that was the

second mate, to get in, an' we never seen one of the crew more,

nowheres. There was oars in the boat, an' we made for land, but

the wind blew us far up into the gulf of Papua. She kep' a-

drivin' us for, I guess, a day an' a half, till we was stranded

on a mud-bank, an' had to wade ashore.

"The natives come down to look at us, afeard like, but gradooally they got less skeered, an' then we went up with them to a sort of village they had, some two or three hunderd yards from shore. Now, mind you, in them times nobody knew nothin' about them blacks that lived in Papua. There was no trade in them days with Australey, nor none with other countries, for folks could get their spices an' birds far easier in the islands to the west, an' had no need to come to Papua. There was some trade with the north coast o' the island, but this part as we was stranded on was way down in the southeast corner, an' the breed as lived there was as diff'rent from the folks as lived a thousand miles off, at the other end o' the island, as a nigger from a Malay. The report was that they was cannibals, an' we was a little afeard at first that they might be out o' fresh meat; but they treated us fust-rate an' no mistake. From the first day that we got there we kep' a bright look-out for a ship, an' we axed 'em by signs if any ships ever comed that way, an' Mister Ince he drew the picter of a ship on a leaf of his note book, but they shook their heads an' larfed, an' it was clear no ship ever comed that way yet. The boat, I must tell ye, had got washed off the mud-bank the first night, an' spiked on a coral reef, an' was so stove in that we couldn't do nothin' with her, an' the natives had no tools that amounted to anything for carpenterin'. So there was nothin' for it but either to stay where we was, or else make for some other part o' the island.

"To nor'ward an' eastward ye could see nothin' but snowy mountains, an' south'ard there was nothin' but swamps, and mud- banks, an' forests o' camphor-trees an' sech like, while goin' west meant getting away from the sea, so we jest concluded to stay where we was, for a while, anyhow.

"The blacks guv us a hut to live in, made o' double lateen sails o' matting—that's the stuff them Malays make their huts on —and for grub we got what they got. There was no lack of oranges, banannys, an' coconuts; and for meat, kangaroos an' sech small game as they could trap or shoot with arrows. An' don't ye forget that them blacks lived purty comf'table for savages. It was the rainy season there, an' the sun was d'rect over our heads, for Mister Ince, the second mate, cut out a quadrant from a piece o' plank with Ben Baxter's jack-knife, an' told us that we was about 7" 30' south, by about 145" 30' east, an' consekently right in the bight of the gulf of Papua. It was the twenty-third of October when we got wrecked, an' Mister Ince said it was jest square midsummer for that latitude, 'cause the sun would travel south for the next two months, an' the next midsummer would come 'bout the middle o' Febrooary, when the sun got on the zenith again, comin' nor'ward. Well, gen'lmen, them savages was the ugliest people ye ever comed acrost. Thick lips? I guess not. Noses like a three-legged pot, beat flat, and two big holes knocked in the bottom of it? Oh, no! Paint? My stars! If they wasn' the most bijousest chromos I ever seen, you may swamp me dead. Why, they jest laid it on as if paint wasn't worth nothin', and no more it was; an' the women was wuss nor the men. But they was as kind-hearted a folk as ever ye see; an' if anybody goes for to tell ye that the Papooans is cannibals, leastways them as we was among, jest tell 'em for me that they're a long ways out in their reck'nin', though they do say that the up-country fellers'll gobble ye up quicker 'n 'scat.

"Them huts o' theirs, made o' coconut mattin', keeps rain out a durn sight better nor canvas, as ye may jedge when they makes their pots an' buckets out o' the same stuff, too.

"Well, gen'lmen, arter about a month or so we began to pickup a smatterin' o' their lingo. Mister Ince, though he was a eddicated man, an' ye would ha' thought could ha' talked it to wunst, was the backwardest of all. I managed to git most o' the grub words purty quick, an' 'How de do?' an' 'Good-bye,' an' them sort o' tricks; but Ben Banter, that was the ignorantst A.B. as ever shipped afore the mast, an' never knowed nuthin', an' couldn't write his own name, though he was bo'sun, he larned the whole of it to wunst. Ben got along with the lingo fust rate, an' bein' a big man, 'bout six foot four, I guess, an' broad in proportion, they was afeard of him, an' used to kneel down an' kiss his feet; but they didn't see nothin' in Mister Ince, that was a little man and sickly. Well, we'd been there 'bout six weeks, I reckon, when Ben says to us one night in the hut:

"'Boys,' says he, 'I'm goin' to get married.'

"'Yes,' says I, 'I thought so. I seen ye makin' up to that broad-beamed squaw with the yaller furbelows. Ye're goin' to do it, are ye? Well, I wish ye luck. Mebbe, ye want me for best man.'

"'Well, Ben,' says Mister Ince, 'I suppose we must make the best of it. Not a sign of a ship in sight, and no chance of one as far as I can see. I mean to try and find a passage to the south along the foot-hills when the rainy season's over, and I thought you would come along with us, but if you get married here we shall have to go without you,' an' Mister Ince coughed, an' I could tell by his cough that he wouldn't never make no passage along no foot-hills to the south in this world, for he was far gone in consumption, though be didn't know it.

"'Well,' says Ben, 'I don't know 'bout that, sir. 'Taint a regular marriage by a priest, ye know, an' I dunno if sech marriages is werry bindin'.'

"'You shouldn't look at it in that light, Ben,' says Mister Ince—he was allus sorter religious—'if the cer'mony is p'formed accordin' to the customs of the people ye're livin' with, it is your dooty to abide by the contract.'

"'Well,' says Ben, scratchin' his bead puzzled like, 'I guess if that's the case I'm the wust Mormon in the South Seas; but a pusson mout as well be killed for a sheep as a lamb, an' one more or less can't make much diff'rence noways.'

"So next mornin', sure enough, Ben was married, an' I'll tell ye how the thing was done. There warn't no cer'mony to speak on, but Ben an' the squaw stood facin' each other, and one o' the old men—I found out arterward he was a kind o' high priest—took an' fried a bananny, an' guv one end to Ben an' the other to the squaw, and then broke it in two in the middle, an' each o' them ate their piece, an' arter that they was reckoned married as tight as airy parson in the world could do it. An' now you gen'lmen mustn't go for to think that them savages wasn't as vartuous as white folks, 'case I tell ye they was. Every man had on'y one wife, an' wunst she was his wife there was no divorcin' of her, nuther. Each pair ockepied a hut, an' the little picaninnies wollered in the sand outside. As I said before, it was the twenty-third of October when we got wrecked, an' it was the third of December when Ben Baxter got married."

"But, captain," I interpolated, getting somewhat tired of the rambling story, and observing W-— smothering a yawn, "what has Ben Baxter's marriage got to do with the monster you asked us here to tell us about?"

"Jest everything in the world," responded the captain, with animation. "If it hedn't bin for Ben Baxter's marriage there wouldn't ha' bin no big beast a-cruisin around them Papooan swamps now."

THIS observation put a stopper on my objections as to the

relevancy of the story, and with some dim idea that the captain

was actually leading up to some conclusion by steps which were

necessary to the intelligibility of his narrative, I determined

to wait patiently.

"Ye see," proceeded the captain, "the squaw as Ben married was the chief's darter, an' out o' that there marriage Ben got bigger an' more popylar nor ever. Ye see, he could throw them savages a- wrastlin', give 'em the foot, an' beat 'em at the club game, an' they made a sort o' god out o' him. Now, I must tell ye that them savages hadn't no idee o' a soopreme bein'. an' didn't keer nothin' for no kind o' wuship of anythin' they cuddn't see, but they wushiped Ben Baxter, 'case they respected his p'ints, an' he was suthin' afore their eyes. Well, it comed on t'ward the middle o' December when the people o' the village begins to make big prep'rations for some sort of a feast, as I could see by their carryin' on an' fixin' up o' all sorts o' grub, an' paintin' themselfs up fresh, an' a hull gang o' savages come in from the country, mebbe eight hunderd or a thousand all told. There was hurryin' around, an' beatin' o' drums, an' clashin' o' metal plates, till we all of us wondered what next. Ben had gone to another hut to live with his wife, an' me an' Mister Ince was left alone by ourselfs. Mister Ince's cough got wuss an' wuss, an' on the fifteenth of December (for we kep' the days notched on a stick) he died, an' me an' Ben Baxter dug a grave, an' we rolled him up in cocoa-nut mats an' put him in, the savages all stan'in' 'round an' lookin' on; an' when we shoveled the sand over him Ben Baxter he cried, an' then all them savages began to blubber like babbies, an' ye never hear sech a hullabaloo in all yer life. An' afore Mister Ince died he guv Ben Baxter his pin an' his ring, an' me his watch an' his pocket-book, for he said he had no living relatives in the world as he knowed on. An here's a bit o' writin' which you gen'lmen 'll understand better nor I do, relative to the country we was wrecked in. It's a bit torn, but mebbe ye may get some facks out of it," and the captain handed us a sheet of note-paper written with pencil in a very small hand, partly indecipherable from age and wear.

W—— took the manuscript, put on his glasses, and after examining it intently for a minute or two, read as follows:

"October 23. 1865—B'ktine Mary Chester, Captain William Ayres; Wellington to Singapore, coal; foundered off Cape Rodney; all hands lost except self, Baxter, boatswain, and Sebright, seaman. October 24th—Made land; natives kind and inoffensive; made quadrant; took latitude from known data and approximately known longitude—7" 30' S, 145" 30' E., giving N. coast of bight of Bay of Papua... (here MS. becomes indecipherable) ... geological formations peculiar; surface outcroppings of Jurassic Period; chalk rocks, lias, and inferior oolite; bluish and grayish laminated clays; cliffs characteristically striped and banded; arenaceous marls and argillaceous limestones; here and there a ferruginous bed; ... conifer, araucariae; cycads abundant, pterophyllum and crossozamia; endogenous plants as well; ximia spiralis (Australian pine-apple) ... both vegetable-eating and carnivorous univalves, limpets, and whelks; starfish, sea-lilies, sponges, corals, ... inland beds of Jurassic fossils; whole mounds of bones of gigantic dinosaurian reptiles; particularly ichthyosaurus and iguanodon: thigh bones of latter eleven feet by... living vegetation as well as geological formation same as in Jurassic Period; most remarkable region; well worthy scientific investigation.... December 3d—Baxter married native woman to-day; shall try to make Cape Rodney when rainy season over; bad cough and very weak...."

"I can make nothing more out of this manuscript," said W——; "the rest is either torn or blurred. What I have read, however, convinces me that the writer had carefully noted the natural characteristics of the country he was cast into, and that these partook strongly of such as we know to have existed in the Jurassic Period. Strange," he mused, "that such a region should exist unknown to the scientific world. Why, it would well repay inspection by government commission. Strange, too, that it should lie in almost the sole spot of earth which still remains more of a terra incognita than even the interior of Africa or the Antarctic continent. And the fact that we know Australia to possess numerous living representatives of the Secondary Period, both in the vegetable and animal kingdoms, such as the araucaria, the screw-pine, and certain classes of shell-fish, leads us to infer that the island of Papua, lying in the same quarter of the earth, but more tropical, may possess similar or even more marked zoological characteristics. I must confess that the somewhat scattered notes I have just read have given me a fresh interest in Captain Sebright's narrative. I shall, with his permission, take much pleasure in submitting them to the notice of the Academy of Sciences at our next meeting. Pray, go on, Captain Sebright. I am all expectation as to the dénoûment of your story."

I was secretly pleased at the turn affairs had taken, and that, after all, my reputation for credulity, as deducible from this visit, would be materially lessened in the light of an endorsement by such an undoubted scientific authority as W——

"I GUESS I left ye, gen'lmen, where we was plantin' Mister

Ince in the sand," continued the captain, when W——

had done talking. "That was the fifteenth o' December, the same

day he died, for it warn't no use keepin' the corpse any longer

in that hot climate. Well, them prep'rations as I was a tellin'

ye about was kept up till the twenty-first o' December, which, as

ye know, is the longest day in the year south o' the line. But on

the mornin' o' that day I could see that suthin' onusual was

goin' to happen, an' I kep' my eyes skinned, case I might get

roped into suthin' as warn't in the game, for I tell ye there's

no trustin' them savages when they gets to celebratin', even if

they is purty rash'nal at or'nary times. 'Bout a' hour arter sun-

up the high priest comes for'ard, outen his hut, to where the

balance o' the blacks was a-stan'in', howlin' an' beatin' their

drums an' things, an' he makes them a sorter speech, an' forms

'em into a percession like, with twelve or fifteen young girls in

the front, an' then the hull gang begins to march to where there

was a big grove o' coconut-trees, an' orange, an' iron-wood trees

a-stan'in', 'bout a quarter o' a mile off! Now I must tell ye

that me, an' Ben Baxter, an' Mister Ince had often been curious

for to see what was inside o' that there grove, 'case it was

guarded day an' night, all round, by a troop o' savages with

weepons, but they never would allow nary one of us to get past

the outside; an' wunst when Ben Baxter offered to go through the

trees they actooally showed fight, an' Ben was so s'prised that

he concluded he didn't care to go nohow. Arter that we all kep'

a-wonderin' an' spekylatin' what sort o' a secret there was in

that grove; but,'s far's we could see, there was never one o'

them savages as went into it—not even the guards as stood

outside, well, gen'lmen, when the percession begun to form, an'

marched in the direction o' the grove, Ben was stan'in' alongside

o' me, an' he says, says he:

"'Jim,' says he, 'I'm a goin' for to foller up them blacks. I kin see there's suthin' goin' to be done inside that there grove, an' bust my toplights if I don't find out what it is.'

"An' I says: 'Don't ye do it, Ben, if they ain't willin', 'case no good can come o' counterin' 'em.'

"But Ben didn't mind me, but goes an' jines in, goin' hand- an'-hand with his wife, an' as I didn't keer to be left behind all alone, I followed up the march a little ways off. When we comes to the grove, the high-priest—a' old man, painted so's to make him look like a devil—calls a lot o' big, strong blacks, an' they drives the young girls as was a-walkin' in front right into the grove among them trees. An' afore they got 'em in the girls screeched, an' screamed, an' fell on their knees, an' cried enough to break anybody's heart; but them blacks pushed, an' rolled, an' hustled 'em in with their clubs an' the p'ints o' their spears, an' the rest o' the crowd kep' up a howlin', an' beatin' drums, so's you'd ha' thought all hell had broke loose.

"Well, gen'lmen, in course I didn't like to see this bizness goin' on, but what could I do? Why, if I had made a move to do anythin' I'd ha' bin chawed up into mince-meat too quick. In a minute or two they druv an' pushed all them girls inside the grove, an' as a lot o' the savages stood guard afore it, in course we couldn't see nothin' more, though the screechin' and yellin' went on wuss nor ever. In about a quarter of a hour the screechin' quieted down, an' arter a minute or two the priest an' the savages comed out, an' I could see blood on their hands an' their legs, as if they had been butcherin' sheep. Then all hands went back to the village except the guards as stayed constant at the grove, an' they had feastin', an' singin', an' dancin', an' kep' it up till mornin'. I didn't keer to jine in, arter what I seen, an' I jest lay in my hut a-thinkin' 'bout strikin' out an' leavin' the durned place anyway, when Ben Baxter comed into the hut, an', says he:

"'Jim,' says he,' atween you an' me, they've been a- slaughterin' all them young girls as was druv into the grove to- day, Now, sure's my name's Ben Baxter, I'se a-goin' what's in that there grove, an' if it's some idol, as I guess it is, I'm a- goin' to smash the durn thing up, an' put a stopper on them purceedin's wunst for all.'

"'Well, Ben,' says I, for I sees his mind was set on it, an' it warn't no use counterin' him, 'be keerful, an' don't take no more risks nor ne'ss'ry. But if ye are bound to go, why, I'm with ye. A feller mout jest as well git killed at wunst as stay in this hell-hole, anyway.'

"So, when it got to be dark, and all the savages was feastin' an singin', me an' Ben slips quiet out o' the hut an' makes for the grove. Now, I must tell ye that this grove covered about four acres o' ground, an' the north side of it was backed by as funny a cliff as ever ye see. It was about two hunderd feet high, an' the top o' it leaned over the grove so that the sun couldn't never shine upon them trees as were under its lee, not even on the longest day when he was south o' the line. Me an' Ben made a kind o' circle like around the grove so's not to let the guards see us comin', an' then we sneaked along the bottom o' the cliff till we reached the trees. I guess them guards thought, mebbe, it wasn't much use a-stayin' 'round in the cold when the fun was a- goin' on in the village. Anyways, me an' Ben crawled in, an' wunst under cover o' the trees we knowed we was all right, perwidin' we didn't make no noise so's to 'tract attention. Well, we crawled along through the grass till we come to a clear place in the middle, 'bout a quarter of a acre, as far as I could jedge, an' in the middle o' the space was a sandy mound— like about twenty foot high. There was a half moon jest a-rising in the east, an' we walked up to the mound, an' what do ye think we seen? As I'm a livin' man, the bodies o' all them girls as was druv into the grove that mornin' was a-lyin'butchered, with their throats cut, around an' all over that mound, an' the sand was red with the poor things' blood. 'Bout five or six lazy vultures flapped their wings an' flew away over the trees as we comed nigh, an' as we was afeared o' diskivery we got back among the trees in a jiffy, and waited.

"'Jim,'says Ben, arter awhile, 'there's some myst'ry in that there mound. 'Spose you go down to the hut, an' bring up them iron-wood shovels. I'm a goin' to find out what's under that heap.'

"So I crawls mighty keerful out o' the grove, gets the shovels, an' brings 'em back to Ben. Then we each takes a shovel and goes back to the mound, an' as we was goin' back over the open space the sand crackled like under foot, an' Ben stooped down an' 'xamined it, an' scooped out a hole with his shovel.

"'Jim,' says he, feelin' down, 'as I hope to die, if this here place ain't made o' nothin' else but human bones strike me blind.'

"An' I looked down too, an' dug down, an' found nothin' but bones, small an' big. An' jedgin' from the arey o' the clear place, an' the depth o' the bones, though we cuddent find no bottom to them so far's we dug, I should calk'late there must ha' bin thousands an' thousands o' people killed right in that spot, an' I says to Ben:

"'Ben,' says I, 'it's enuff to make a man shudder when he thinks how many poor critters must ha' bin slaughtered here to make all them bones.'

"An' Ben says, 'Yes, that's so; let's hurry up or else them savages 'll ketch us, and there'll be hell to pay.'

"So we went to the mound, an' fust we cleared away the bodies o' the twelve young girls as was layin' around dead, and we lays 'em side by side, orderly like, an' then we takes our shovels an' begins to shovel away the sand o' the mound, beginnin' at one side o' the bottom. It was purty stiff work, 'case the sand was more like clay, an' a dark, dingy color, 'pearin' to have been soaked with blood through an' through. Well, we shovels on for mebbe ten minutes, an' had got three or four foot into the stuff when I hears suthin' rattle like iron, an' Ben says:

"'Jim,' says he, 'I struck suthin' hard,' an' he jabs his shovel in agin, an' says, 'yes, whatever it is, it's almighty hard.'

"An' then I gives the thing a dig with my shovel, an' it seemed like as if I was hittin' a piece o' gutty-perky, for the iron-wood bounded back off of it, an' it guv a little.

"Then Ben says: 'That there thing is big. Lets get to the top o' the heap, an' shovel the sand off of it till we gets down to the durned thing, whatever it is.'

"So we both climbs to the top o' the mound, an' starts in to shovel like good fellows. Arter 'bout half a hour's work we got about six foot o' sand throwed off, an' struck our shovels on to that hard stuff agin.

"'This is the top of it,' says Ben,' an' I guess that there fust hole's at the bottom. I'm a-goin' to clear every grain o' sand off of it afore I stop, if it takes a month, an' find out what the durn thing is.'

"So we both starts in ag'in, sayin' nothin', but workin' steady. We must ha' worked purty quiet, too, for them sentries never heerd us, though they warn't more'n a hundred yards off. The moon was 'bout a' hour high when we began the job, an' 'bout five hours high when we got through an' got the thing clear, an' day was beginnin' to break in the east. An' what d'ye think it was? Well, gen'lmen, I'm blest if I ever seen a funnier thing in my life. It looked like a round ball 'bout twelve or fourteen foot through, but flattened out where it was layin' on the sand. Its color was a sorter yaller brown, an' the thing was wrinkled all over like the hides o' them rinosserys I wunst seen in Afrikay. We struck it with our shovels all over, but cuddent make nary mark nowheres, the stuff was so thick an' solid.

"'Well,' says Ben, wipin' his forrid, 'here's a go. I wonder what them saviges 'll say when they finds out what we done. That's a purty sort o' a god for to kill girls to,' an he hits the thing another lick with the shovel, so hard that it sounded all over the grove, an' next minute 'bout fifty saviges come runnin' in with their clubs an' spears, an' makin' sech a hullabaloo as ye never heerd in all yer life."

"WELL, when they seen what was done, an' the big round ball a-stan'in' where there had on'y bin a heap o' sand afore, they stood dazed like, lookin' at each other, an' at me an' Ben, who was stan'in' there leanin' on his shovel, onconsarned like. It was easy to see they didn't know what to do, case the hull thing was out o' their 'xper'ence, an' so we jest waited to see what would turn up. Arter a few minutes the high priest comes in with a gang o' blacks from the village, an' then the hull o' them stood jabberin' their lingo, an p'intin' to me an' Ben an' the big ball. Presen'ly the high priest goes to one side with some o' the jabberin' to themselfs they turned round, an' the priest made a sign, an' the balance o' the savages formed a circle around us, an' stood threatening like. Then Ben says to me:

"'Jim, them blacks means mischief, but the fust one as comes at me I mean jest to let him have it good. There's one got to fly up ahead o' me;' an' he took a tight hold o' the iron-wood shovel, an' I seen he meant bizness.

"'All right,' says I, 'I guess we kin die jest as hard as the nex' one if it comes to the p'int.'

"An' jest at that moment Ben's wife come a-runnin' in through the trees, an' breaks through the circle, an' stands alongside Ben, an' begins jabberin' like mad. I didn't know what she was a- sayin', but Ben did, an' as I found it all out arterwards I'll give ye the jist of it now. The rules o' the place was that no one should enter that there grove on pain o' death, and the high priest had said that we was to die. When Ben's wife come a- runnin' in, an' seen what was up, she told Ben his on'y chance was to do suthin' that the high priest cuddent do. Ben looked at me sorrowful, an' said:

"'What in blazes kin I do, Jim, that them savages will respeck, an' that they can't do themselfs? The high priest says that there thing's a god, an' if I'm a god I must pe'form a merricle to prove it, for, mind ye, them savages had still some ling'rin' idee that Ben was more nor a or'nery man.

"Then I thought a minute, an' I says: 'What did ye do with that can o' tar that was lyin' in the boat when we was wrecked?'

"Ben says: 'I guess it's lyin' there yet.'

"'Hold on till I fetch it,' says I. 'I guess we kin pe'form a merricle with that tar.'

"So arter some purlaver they 'lowed me to leave the grove, half a dozen o' the savages goin' with me to see I wasn't playin' to escape. When I got down to the shore, sure enuff there was the tar-can a-layin' in the bottom o' the boat, an' arter I got it I dug up a lot o' them mangrove roots as grows in the water, and when I got enuff, I starts up back for the grove, an' the savages with me, An' on the way up I smears four o' the wet roots with the tar that was in the can, on the sly, an' unbeknownst to the savages, that hedn't no idee what tar was anyways. When we gets back, I hands the roots to Ben, and tells him what to do. Then I waits quiet to see what would happen. Then Ben, an' his wife, an' the high priest got a jabberin', an' Ben hands the wet mangrove roots as hedn't no tar on 'em to the high priest, and axes him if he could burn 'em, at the same time tellin' him that he could burn his'n. I could see that Ben's move staggered the priest, for you bet he warn't no fool for a savage: but he put a good face on it, an' sent some o' the blacks down to the camp for fire-brands. Bimeby they comes back with the fire-brands, an' builds a big fire on the sand, an' the priest he takes his wet mangrove roots and makes passes over 'em, an' mumbles an' prays as nat'ral as any real priest ever I see, an' then he takes the biggest flamin' brand he could see out o' the fire, an' the littlest mangrove root he could find in the hunch, an' holds it steady in the flame; but it on'y fizzed and spluttered, an' though he kep' on holdin' it in the flame, there was nary burn in it; an' at last it put out the fire in the brand, and the blacks as was stan'in' round looked on solemn, as much as to say: 'What are ye tryin' to do, old man? Haven't ye lived long enuff to know that them wet mangrove roots won't burn?' An' the old priest looked kinder 'shamed of hisself for showin' the people there was suthin' he couldn't do. Then Ben comes for'ard, smilin', with his mangrove roots as had the tar smeared over 'em, an' bows to the comp'ny, an' takes one o' the roots and holds it to a blaze, the same's the priest did, an' in course the tar that was on it caught fire to wunst, an' blazed up like tinder. An' you jist bet them savages seen the p'int right away, an' every mother's son o' them downed upon his marrow bones, and slammed his forehead into the sand afore Ben, an' the high priest downed hisself too, an' crawled upon his knees to where Ben was a stan'in', an' kissed his toes.

"'Now, says Ben, to me, 'we got them savages jest where we want 'em, an' I'm a-goin' to spile this god bizness right now.' Then he hollers out in their lingo, an' commands 'em all to rise. An' they riz to their feet an' stood with their hands crossed on their breasts like mummies, the hull gang o' them. Then he sent some o' them down to the village for ropes, for they made tidy strong rope out o' coconut fibre, them savages did. An' while they was gone Ben says to me: 'I guess the best way to stop this murd'rin' bizness is to take that there ball out o' this grove, and cut down the trees.'

"'Well, Ben,' says I, 'you are the boss god now, an' I reckon ye better do it.'

"So, when the savages come back with the ropes, Ben set the whole crowd to work a-tearin' up an' knockin' down the trees with their iron-wood axes. It was purty heavy work 'case the trees was old an' thick, but soon there was a lane cleared wide enuff to drag the ball through into the open. There was one thing, gen'lmen, that I noticed pertikler, an that was that at high noon that there ball laid jest on the edge o' the shade o' the cliff, an' this bein' the longest day in the year, an' the sun at its furthest p'int south o' the line, it was easy to see that the sunlight hadn't never shone on the ball so long as it laid in that there place. I didn't think nothin' o' the suckumstance jest then, nut arterwards when I seen what happened, I called to mind that very fack for a explanation o' the mist'ry.

"Well, as I was a-goin' to say, when night comed on me an' Ben Baxter an' the savages lef' the grove, an' went down to the huts to sleep; but a lot o' them stayed in the grove around that ball, I s'pose through habit. An' next mornin' we all goes back to the grove, an' Ben an' me twists a lot o' them ropes into a three- strand hawser, for we cuddent tell how heavy the durned thing might be, an' we didn't want for to break the ropes with too heavy a strain. So, arter we got the hawser made, we throws a hitch around the ball, bringin' the two ends inter a slip-noose, leavin' about a hunderd feet o' cable for pullin' at. Then we gets about fifty o' the strongest savages an' stations 'em all along the rope, an' Ben gives 'em the word to pull. Jest then the high priest an' a lot o' the old gray-headed men kneeled down afore Ben, who was a-stan'in' right in front o' the ball, and began talkin' their lingo. I didn't know what they was drivin' at, but I heerd arterwards that they was prayin' an' beseechin' Ben not to move the ball, as suthin' fearful would happen to them, sayin' as how nobody knowed how long it had laid there, but there was a mound in one corner o' the grove made o' pebbles, an' each year, when the young girls was sacrificed, the high priest put another pebble on the mound. Fust of all, me an' Ben went an' looked at the heap o' pebbles, which was a sort o' pyramid 'bout ten foot high, an' as far's I could calklate, must ha' held more nor a million pebbles.

"'Why,' says Ben, when he seen that mound o' pebbles, 'that there ball must ha' laid there thousands o' years afore Adam an' Eve, or else that high priest is the durndest liar I ever see. Anyways, I reckon the last pebble has been throwed on that heap, an' that ball's a-goin' out o' this here grove this very hour, or my name aint Ben Baxter.'

"So we goes back to the ball, an' Ben he shoves the priest an' the old men out o' the way, an' gives the word to pull. But the durned thing stuck so fast to the sand that there was nary pull to it, till all of a sudden it tilts up, 'case me an' Ben an' about twenty more savages was givin' it a h'ist from behind, an' so it made a roll over, an', in course, the hawser slipped over the top.

"'Ye might ha' knowed that, Ben,' says I; 'we kin git that there ball out a durn sight easier rollin' it than draggin' it.' So we all gits behind it, an' jest rolled it over an' over, like a big snow-ball, till we got it clear o' the grove, an' right out on the open flat in front o' the village. An', although the thing was about fourteen foot through, it didn't weigh no more nor about five ton, noways.

"Then Ben says to me: 'Jim, I guess we've settled this bizness now; but the idee's got to be kep' up, an' I'm a-goin' to show them blacks the difference atween a real livin' god an' a big, round, horny ball. Jest fetch up that stool that I made when we fust comed here.'

"So I brung the stool up from the hut; an' Ben takes out his jack-knife, an' cuts steps in the side o' the ball, to climb up to the top of it, 'case he said it would look ondignified for a god to go sprawlin' an' scramblin' up the smooth side of a ball, a-holdin' on by his teeth an' eyebrows. When he was wunst up I throws up the stool to him, an' then he digs four holes in the top for to steady the stool's legs, an' then wipes his forrid, an' sets down. An' when the savages seen Ben a-sittin' on' the top o' the ball what they used to think was their god, when it was a-layin' in the grove covered up with sand, an' nobody knowed what it was, they sets up sech a whoopin', an' a hollerin', an' beatin' o' drums as ye never heerd in all yer born days. Arter that they builds Ben a big hut, with four ply o' coconut mattin', an' twice as big as any of the other huts, an' they brings him the best o' the fruits an' sich other grub as there was, an' he hedn't nothin' to do but jest take it easy. An' the high-priest knuckled to him, 'case the fo'ks all knowed how bad he was beat a-burnin them mangrove roots, an' he seen it warn't no use buckin' agin popylar opinion Every mornin' an' evenin', bein' the coolest time o' the day, Ben used to climb the ball, an' set down on the stool, an' smoke his pipe—for there was a weed on the island suthin' like 'baccy—an' he laid down the law to them savages if they got quarrelin' or stealin', an' guv 'em fifty or a hunderd strokes with a bamboo if they got onruly.

"Well, gen'lmen, things goes on jest the same as ever for the next five or six months, an' nary sign of a ship to be seen in the offin'. We begun to git 'customed to the kind 'o life, an' gradooally got to speak the lingo purty free, an' last o' all, I gets married myself to a purty nice young gal, I tells ye, take her all-in-all. It was the twenty-second o' December when we rolled the ball out o' the grove where, as I said afore, the sun hadn't never shined upon it, 'case it was layin' jest in the shadder o' the cliff; but arter we rolled it out on to the open flat in course the sun kep' a shinin' onto it all the time, exceptin' night times. Ben used to say to me when he comed down from the top of an evenin':

"'Jim, no man could go for to mount that there ball durin' the heat o' the day. The horn, or whatever stuff it's made of, gets red hot in the sun, an' burns ye as bad as red-hot iron'—which was a fack, for I felt it many a time.

"Well, it comed on to July or August, which is the winter season there, though the sun's jist near as high in the north as at any time o' the year, for there ain't much difference nohow in the tropics, and though I hain't particular sure 'bout the 'xack date, still you kin jist bet I remember what happened then jist as clear as if it was yesterday. It was a stiflin' day; not a breath o' wind stirrin'; an' I kep' indoors all day 'case o' the heat. 'Bout sundown I takes a turn as usual, and when I gets out I seen Ben a-makin' for the ball with his pipe in his mouth, the same's usual. He clumb up to the top by the steps cut in the side, an' sat down, the savages a-stan'in' round, an' talkin' to Ben the same as to a jedge in the court. I was strollin' around, smokin', and not pertiklerly keerin' for what was a-goin' on, havin' seen the same thing ev'ry evenin' for months, when suddently I hears one o' the savages givin' a yell, an' lookin' round, I seen that there ball a-movin' an' swayin' this-a-way an' that-a-way, an' Ben Baxter a-sittin' on the stool a-top with his pipe in his mouth, an' lookin' as white's a sheet, and his eyes a-rollin', and his hull body stiff like. I was paralyzed myself, and cuddent move a muscle, I was so s'prised, an' so was the savages, an' for about five seconds, I guess, though at the time it seemed more like a month, that there ball kep' a-shakin' an' swayin', an' everybody stan'in' lookin' at it, onable to speak or move through s'prise. Then all to wunst one side of it cracked and bust wide open, an' a head looked out, and it was the most hijousest head I ever seen or expeck to see. It was flat like a lizard, an' 'bout four foot long, an' two big eyes, like soup- plates, stood 'bout half a foot out from its forrid, an' it had a tusk comin' out from the top of its nose, 'bout a foot long. An' a second arter I hears r-r-rip, an' that there ball or shell bust right in two, an' a tremenjous beast comed out and stood upon the sand. Its body was 'bout twelve foot long, dark- brown in the color, an' scaly like a crocodile. Its fore-legs was short, an' its hind-legs big and strong, an' it had three sharp claws upon each foot. An' it had a tail like a lizard, 'bout ten foot long', that wiggled an' curled as it walked. An' jest as the ball bust the second time, the stool as Ben Baxter was a-settin' on fell down, an' Ben with it, an' hit the beast on the back o' the neck, an' Ben rolled over, and lay on the ground like dead. An', meanwhile, all the savages as was in the huts had come out when they heerd the fust scream, an' was a-lookin' on, all a- stan'in' still an' onable to move. An' the big beast stood still for about three seconds a-lookin' about him, an' seemin' puzzled like, an' onsartin how to act, an' then he moved off, makin' straight for the swamps an' mud banks as I told ye was covered with sago-palms, an' coconuts, an' big thickets an' all kinds o' trees an' brush. An' the fust move he made was acrost Ben's body, though he didn't notice Ben, an' seemed skeered an' afeard like. An' as soon's he moved all them savages, ev'ry mother's son o' them, set up sech a yell o' fear as no man ever heerd afore, an' they made a break for the woods, men, women an' children, till the last one o' them was out o' sight, an' I was left alone with Ben Baxter an' the ball. It's no use for me to say I warn't skeered, 'case I was, but when I seen that the beast had went away, I knowed there warn't no 'mediate danger, an' I went over to look at Ben Baxter. I stooped down an' turned him over on his back—he was layin' on his face—an' tried to rouse him, but he was stone dead. Nary scratch on him, nuther, for the beast, though I seen him walk acrost his body, hadn't put a foot on to him, or else he would ha' been smashed inter pulp. So I concluded that Ben had jest simply been skeered to death.

"It was three days afore the savages comed back to the village, an' then they was mighty slow an' keerful about it. That's all, gen'lmen, I've got to tell ye about it."

"And did you ever see this monster again?" I inquired.

"Hunderds an' hunderds o' times," replied Captain Sebright. "I lived with them savages for nine years arter that, till a schooner from Australey happened to come up the bay for nutmegs an' spice, an' I got off in her."

"What were the characteristics of the monster?" asked W—— "Did it ever attack the settlement, or make itself obnoxious in any way?"

"I never seen nor hearn tell o' no one bein' hurt by it. It kep' to the swamps and jungles, an' never bothered the folks in the village. It growed very fast, too, for it was on'y 'but twelve foot long when it was hatched out o' that ball, or egg, or whatever ye may call it, an' the last time I seen it it was 'bout sixty foot long, an' smashin' an' crashin' its way through big forest trees the same as if they was stubble."

"Did you never give the facts of the case to the public before this—I mean, did you never tell the story before just as you have told it to us?" I inquired, after a pause.

"Bless you, yes," returned the captain, smiling, "many an' many a time. But d'ye think they would b'lieve a word o' it? Not much. Some o' them would smile, an' look wise, as much as to say, ye can't come over me with yer yarns; an' some would git mad, and call me a old fool, an' I s'pose you gen'lmen is jest like the balance o' them."

"Have you any immediate use for this paper, Captain Sebright?" asked W——, taking up Mr. Ince's manuscript from the table, "If not I should like to borrow it for scientific purposes."

"You kin have it, sir, an' return it when you git ready," replied the sailor, and without further comment we took up our hats, said good-bye, and left.

"THIS is a most extraordinary narrative," observed W——, throwing himself into an easy chair, when he reached his rooms. "My reason refuses to credit it, and yet its internal evidence corroborates it. Had the story been told by a person of intelligence and education, I should have regarded it with very grave suspicion; but it seems scarcely possible that this ignorant sailor should have so arranged his facts as to tally with what would actually happen had the subject of his theme existed. The second-mate's description of the geological characteristics of that region, too, show that the physical conditions were just such as were essential to the production of such a prodigy. But the idea of an egg lying out upon the sand, and coming down to us from the Secondary Period;—"

"Hundreds of thousands of years ago," interrupted I.

"And its juices not getting dried up—"

"And not getting hatched out long before by the mere caloric of the atmosphere—"

"Why the thing is preposterous!" And W—— went to his bookcase and took down a book.

"Still," I ventured to remark, "the vitality of Nature's germs is almost infinite. To destroy species must be a titanic task. Man, at least, has always failed in doing it, and yet he is at constant war with all. Grain seeds which have lain centuries upon centuries in the buried vaults of Pompeii, and in the Pyramids of Egypt, have sprouted with the same vitality and vigor as those of last year's wheat crop; and shall we say that, under certain conditions, the egg of an animal might not preserve the vital germ for an equally indefinite period? Can you assert that such an instance is physically impossible?

"No," rejoined W——, thoughtfully; "I have no right to do so. Here," continued he, opening a volume, "is a representation of what the iguanodon, that monstrous dinosaurian of the Secondary Period, would look like, were it reconstructed from the few osseous remains found in the Wealden clays and other cognate formations. Let us see what the article accompanying it says, and how far it tallies with Captain Sebright's narrative," and W—— turned over the leaves till he found the place.

"Now," he continued, "this monster might possibly have been a teleosaurus, certain species of which, the book informs us, measured as much as thirty-three feet in length, three of which were occupied by the animal's head. Its awful jaws, which were well defended beyond the ears, opened as wide as six feet, through which it could engulf, in the depths of its cavernous palate, animals of the size of an ox. Or, possibly, a megalosaurus, which measured, we are told, thirty-eight to forty feet in length, and which is fully and graphically described in Dr. Buckland's admirable Bridgewater treatise. Cuvier, however, from the dimensions of the coracoid, (a process of the scapula,) supposes that the Megalosaurus Bucklandi may have been some seventy feet in length. But neither of these animals possessed the facial horn, and both were carnivorous—two facts which are at variance with Captain Sebright's description. Ah! here we have it—the iguanodon. 'Of more formidable dimensions than the megalosaurus was the Iguanodon, (or 'iguana-toothed'). which, so far as our researches have hitherto extended, must be pronounced the most gigantic of the primeval saurians. Professor Owen differs from Dr. Mantell in his estimate of the animal's length, which the latter makes from fifty to sixty feet. The comparative dimensions of its bones show that it stood high on its legs, the hind-limbs being much longer than the fore, and the feet short and massive. The form and disposition of the feet show that it was a terrestrial, as its dentition proves it to have been an herbivorous animal. The iguanodon carried a horn on its muzzle. A skeleton, nearly perfect, was discovered by Mantell in Tilgate Forest.'"

"It would seem, then," I remarked, "that our savants differ materially in their estimate of the size of these animals, and in view of the old apothegm, 'who shall decide when doctors disagree?' I suppose the testimony of Captain Sebright, and the captain of the Australian schooner who sighted the monster, as reported in the Brisbane Courier, both of whom put down the animal's length at from eighty to a hundred feet, is entitled to quite as much respect as inferences merely drawn from an examination of bones, though made by authorities however distinguished."

"Well," responded W——, thoughtfully, "unscientific men, and men untrained in forming nice estimates of dimensions in relation to distances, are more prone to err on the side of exaggeration than diminution of facts. The mere assertion of a parcel of sailors on a matter of size of any object seen would carry little weight in my formation of an opinion. But what does carry weight is Captain Sebright's account of the dimensions of the egg. If the captain's measurement of the egg's diameter—fourteen feet—is to be accepted, we must necessarily accept his measurement of the egg's depositor—eighty to a hundred feet. Ex pede Herculem—the size of the egg the size of the animal. The captain's testimony is unimpeached, yet it is not corroborated. Its strongest title to belief lies in the internal evidence of the story backed up by the credibility of the narrator. Meanwhile, I shall lay the facts before the Academy of Sciences, and await further accounts in the Australian papers."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.