RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

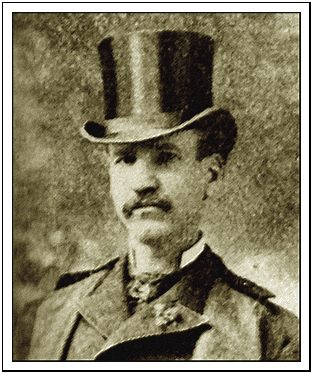

Robert Duncan Milne (1844-1899)

THE Scottish-born author Robert Duncan Milne, who lived and worked in San Fransisco, may be considered as one of the founding-fathers of modern science-fiction. He wrote 60-odd stories in this genre before his untimely death in a street accident in 1899, publishing them, for the most part, in The Argonaut and San Francisco Examiner.

In its report on Milne's demise (he was struck by a cable-car while in a state of inebriation) The San Fransico Call of 17 December 1899 summarised his life as follows:

"Mr. Milne was the son of the late Rev. George Gordon Milne, M.A., F.R.S.A., for forty years incumbent of St. James Episcopal Church, Cupar-Fife. and nephew of Duncan James Kay, Esq., of Drumpark, J.P. and D.L. of the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright, through which side of the house, and by maternal ancestry (through the Breadalbane family), he was lineally descended from King Robert the Bruce.

"He received his primary education at Trinity College, Glenalmond, where he distinguished himself by gaining first the Skinner scholarship, which he held for a period of three years; second, the Knox prize for Latin verse, the competition for which is open to a number of public echools in England and Ireland, and thirdly, the Buccleuch gold medal as senior and captain of the school, of the eleven of which he was also captain.

"From Glenalmond Mr. Milne proceeded to Oxford, where he further distinguished himself by taking honors, also rowing in his college eight and playing in its eleven.

"After leaving the university he decided to visit California, a country then beginning to be more talked about than ever, and he afterward made the Pacific Coast his residence. In 1874 Mr. Milne invented and exhibited in the Mechanics' Fair at San Francisco a working model of a new type of rotary steam engine, which was pronounced to be the wonder of the fair.

"While in California Mr. Milne for a long time gained distinction as a writer of short stories and verse which appeared in current periodicals. The character of his work was well defined by Mrs. Gertrude Atherton, who said:

"'He has an extravagant imagination, but under it is a reassuring and scientific mind. He takes such a premise as a comet falling into the sun, and works out a terribly realistic series of results: or he will invent a drama for Saturn which might well have grown out of that planet's conditions. His style is so good and so convincing that one is apt to lay down such a story as the former, with an anticipation of nightmare, if comets are hanging about. His sense of humor and literary taste will always stop him the right side of the grotesque.'"

A caricature showing Robert Duncan Milne and a San Francisco cable-car.

THE story I am about to relate will seem absurd to most, fanciful to many, but suggestive, I hope, to a few. Absurd to those whose ideas are bounded by the iron pale of dogma and prejudice; fanciful to those who, though intellectually capable of grasping the philosophy set forth, yet can not see beyond or behind the school they have been brought up in; suggestive to the few who still retain independence of thought sufficient to know that they as yet know nothing of the inner workings of nature. I offer no apology and ask no credence for the facts narrated. My province is simply to state them, and leave the conclusions to be drawn from them to the public.

About a year ago I chanced to drop in, one Sunday afternoon, at a certain public hall, where a so-called spiritualistic meeting was in progress. Though by no means a disciple of this creed, philosophy, superstition, or whatever else it may be styled, I have yet found sufficient originality of idea in its supporters to justify me at least in giving the subject a fair examination, so far as in me lies. It has always seemed to me that, taken as an entirety, the principle which is aimed at in this—shall I call it philosophy?—is a pure and elevating one; that, however its individual exponents may err through motives of gain or some passion equally ignoble, the main idea is not to be judged by the conduct of a class of its supposed adherents.

There can be no question that the idea of a hereafter, conditioned in a reasonable mode, where there is room, opportunity, and encouragement for the development of the spiritual and intellectual portion of man's nature, is a prepossessing and seductive one. If the conception is vain and baseless, there can be no question that a large proportion of intelligent people, in this country more especially, entertain it; and I think it may be safely admitted that those who do not entertain it, unless they are extremely ignorant or depraved, would be glad if they could reasonably do so. To my poor apprehension, the hereafter of the spiritualists has more to recommend it—has more flesh and blood, so to speak—more reasonableness, more affinity with ordinary humanity, and is constructed on a less fanciful plan, than the heaven of the theologians. But the proof? Ah, the proof—the proof the existence of a hereafter at all, conditioned in any manner whatsoever, or constructed on any plan—has it been produced?—is it forthcoming? The dominant and, theoretically, the purest religion on earth bases the dogma of immortality on faith, and faith it defines as the "substance of things not seen." On the other hand, the claims of the spiritualistic philosophy have never been universally, or even widely, acknowledged; its assertions are open to refutation; its proofs are not such as would be admissible in a court of law. The many mysterious phenomena which it professes to produce have been actually and perfectly produced by the ordinary art of the conjuror, and so long as there is a possibility of producing them by natural means, the unbiased judgement will accept the readier explanation of their production.

The phenomenon of materialization, more particularly, has never been placed on an irrefutable basis, nor subjected to the test of scientific investigation; but has, on the contrary, been frequently exposed as the creature of palpable and glaring fraud. While the true spiritualistic deplores this fact, and deprecates sentence being passed upon his philosophy because of it, the true disciple of positive science demands, as he has a right to do, indisputable proof of the alleged phenomenon. That such proof has not yet been forthcoming, and that the so-called phenomenon of materialization—that is to say, the appearance of a being who lived upon this earth, at some period in the past, in a substantial and recognizable form, without the possibility of deception or fraud in such appearance—has never been attested by competent and unprejudiced witnesses, is a very strong argument that this phenomenon will not bear scientific investigation, and that conclusions drawn therefrom, as bearing upon the actuality of a future existence, however convincing they seem to the eye of faith, are not admissible in the logic of exact science.

It has, strangely enough, fallen to my lot to witness an example of this phenomenon worked out, not only without the aid of the ordinary paraphernalia of mediums, cabinets, darkness, and the other conditions of so-called spiritual manifestations, but in a purely material manner, and in strict accordance with scientific law. Nay, more than this, the lady who was the subject of this rehabitation in her original human form, did not vanish, like the "baseless fabric of a vision," after reincorporation, but retains her substantial form, and is at this moment in full possession of all the functions of life. Yes; the vast problem is at last solved, the door of the mystery is unlocked, and all doubts as to the existence of intelligent spirit independent of corporeal framework is set at rest forever. That others may arrive at a similar conviction upon this all-important issue is my object in giving the following history to the world.

Some months ago, I happened to be present at a spiritualistic meeting in a certain public hall of this city. The exercises began, as is customary, with an oration by a so-called inspirational speaker. Next, a lady "medium," seated at a table covered with folded slips of paper, upon which names of deceased friends had been previously written by as many of the audience as chose to do so, delivered what purported to be communications from spirits answering to the written invocation. After this, a cabinet, such as is used by most materializing mediums, was wheeled upon the stage, at an opening in which appeared semblances of human hands and faces, the medium being, to all appearance, securely bound within, and consequently supposed to be incapable of producing the phenomenon in question unassisted by external agency. All this I had witnessed many times before, and had long since ceased to wonder, not at the manifestations, but at their meaningless puerility. Surely, I thought, the mechanical display of hands, and the discordant rattle of musical instruments is scarcely a fitting occupation for a departed spirit, nor does it impress one strongly with the dignity of the future life. While indulging in this train of reflection, a gentleman who sat next me made a remark singularly coincident with my engrossing idea:

"Strange, is it not," said he, "that dupes and charlatans should be suffered to tamper with the sublime mystery in nature! It is this monstrous burlesque which brings the living reality into discredit."

The remark was singular and suggestive. It seemed to imply more than it expressed. I recognized in the speaker a gentleman whom I had seen at these meetings on several previous occasions, and also a physician of good reputation and practice, one whom I knew well by sight though not from personal acquaintance. I felt curious to know to what extent Doctor S— believed in spiritualism, if, in fact, he did so at all, and so took occasion, when the meeting broke up, to improve the opportunity he had given in dropping the above remark by introducing myself. As it happened that our ways both led in the same direction I walked up the street with him.

"What is your opinion, Doctor, of the phenomena we have just witnessed?" I asked, point blank.

"I think they are clever tricks," replied the doctor. "I have seen Heller and other first-rate conjurers produce results far more inexplicable."

"Do you, then," I continued, "include all so-called spiritual manifestations in the same category?"

"By no means," he answered, with animation. "There is no question in my mind that the manifestations afforded by certain media are genuine. But they are empirical. They bear the same relation to the true service of spiritualism as the nostrums of the quack doctor do to those of the regular practitioner. The quack may, and very frequently does, achieve results in therapeutics, but he does not know why he so achieves them. He does not grasp the inner meaning of what he does. Therefore he is a quack. In like manner the medium has no conception of the natural law by which the manifestations of rapping, clairvoyance, and materialization are brought about. Until these phenomena are formulated and reduced to a scientific theorem, reasonable people—that is to say, people who hold faith and imagination subservient to reason—will have nothing to do with them. Science holds aloof from their consideration, as yet, for two reasons: firstly, because most men of science consider the examination of the subject trivial and beneath their dignity; and, secondly, because those who are broad-minded enough to give the subject consideration at all, do not know where to begin. They are in the position of Archimedes, who volunteered to move the sun if he were given a lever and a fulcrum. They are even better off, for they have the lever of the physical sciences; all they want is the fulcrum. They do not know where to begin the attack. There seems to be no single foundation-stone of scientific fact whereon to build a logical scientific structure."

"Yet you tell me that you, who are well known as a man of scientific methods of thought, attribute these phenomena to a genuine scientific cause," I remarked.

"Certainly, I do," acquiesced the doctor; "and what is more, I have no doubt that I have arrived at a proper conception of that cause."

"Are you at liberty to explain its nature?" I asked.

"I can give it to you in one word," he replied: "electricity."

"Pardon me," I said, "but this does not explain anything to me at all. It seems to me that a vague generalism only leads us farther from the concrete fact we wish to get at."

"I am aware," he went on, smiling, "that the phrase I employed is a generalization in which ignorance finds refuge, and by which quasi philosophers evade a subject they are unable to grapple with. I know that 'electricity' is considered responsible for all natural phenomena which can not be explained on any known scientific hypothesis—earthquakes, cyclones, tidal-waves, sun-spots, and what not. It would therefore be a very easy way of getting over the difficulty in regard to the cause of spiritual manifestations to merely say that they had their origin in some form of electrical action. But we must be more particular; we must condition that action in such a manner as to reasonably account for the phenomena."

"And you say you have done this?" I observed, inquiringly.

"I can at all events account for all so-called spiritual phenomena in a manner satisfactory to myself," replied he, "and I am considered somewhat fastidious, logically speaking, and difficult to please," he added, dryly. "But here we are at my house. Won't you come in and rest, and perhaps I may be able to explain myself more minutely?"

We turned into the grounds and entered the house. As we entered the drawing-room a lady rose to meet us, whom the doctor introduced as his wife. She immediately after sank down upon the cushions whence she had risen to receive us. I could see at once that Mrs. S— was in the grasp of that most pitiless and hopeless of all maladies, consumption. I could see, too, that she retained traces of what had once been remarkable beauty of a refined and intellectual order. As our conversation progressed it insensibly glided from a discussion of the meeting we had just left to a consideration of the spiritual philosophy in general and the mystery of future life. The lady spoke freely and unreservedly upon this topic, speculating calmly upon her approaching dissolution, which the doctor acknowledged himself powerless to prevent. Florida, Italy, Madeira, all had been tried, but they had only served to retard, not avert, the approach of the inexorable destroyer. Then, as frequently happens in such cases, Mrs. S— had expressed a wish to pass away peacefully amid the scenes she loved; and that this wish had been acceded to by the doctor showed conclusively that he, too, considered the case beyond the reach of human aid. While noting the tender care and consideration with which the doctor arranged the cushions and performed those hundred little nameless offices, which only affection dictates, for his invalid wife, I could not help wondering, as so many more have fruitlessly done, at the mysterious provision which does not permit us to know whether the emotions and affections are merely the chance mechanism of a moment, or enduring and imperishable entities which have an infinitely more lasting existence than the forms of matter with which they are now associated. I at length rose and took my leave, being accompanied to the door by Doctor S—, who repeated his promise to go more fully into the subject I had come to investigate on some future occasion.

Months passed, during which I paid no further visits to spiritualistic meetings, nor was I again thrown in the way of Doctor S—. In fact, our meeting had dropped entirely out of my memory, when it was abruptly recalled, a few days ago, by the receipt of the following note:

863 E Street, January —th, 1883.

Dear Sir:

You will doubtless remember meeting me and accompanying me to my house one Sunday in August last. I then promised to explain to you my views on the subject of spiritualism. I am now ready to fulfill that promise. I particularly request that you will come to my house this evening, as early as you can. You can confer a lasting obligation on me by doing so, as I have a most important personal reason for desiring your presence. Tomorrow will be too late; and if you can not be at my house this evening by six o'clock, please let me know upon receipt of this, by messenger.

Yours truly,

Stephen S.

EVEN had I been otherwise engaged, the earnestness of the

doctor's letter would have induced me to forego the engagement;

but as I was not, I immediately dispatched a messenger saying

that it would give me great pleasure to accept his invitation.

Six o'clock accordingly found me at the entrance of the doctor's

mansion. I rang the bell, and the door was opened by himself. He

was evidently expecting me. He shook me warmly by the hand, and

led me into the drawing-room, where a comfortable fire burned in

the grate, and where I had, on my former visit, been introduced

to his wife. I remarked her absence, and immediately inquired

after her health.

"Mrs. S—," replied the doctor, gravely, in answer to my query, "is, I grieve to say, at the point of death. I do not think she will last through the night." I forbore to make any comment on this singular communication, though I could not help feeling inwardly surprised that the doctor should have chosen such a time as the present to explain his views on the subject of spiritualism. Nor was the mystery lessened by the reflection that he might possibly have only made the promise a pretext for securing my presence to assist him in watching over and soothing the final hours of his dying wife, for I neither belonged to the medical profession nor was I an intimate friend of the family; and the circumstances of the case forbade the supposition that my attendance was required in any capacity of mere ordinary utility.

The doctor seemed to divine what was passing in my mind. "I supposed," he said, "you are surprised at my sudden and urgent invitation of today, in connection with what I have just told you. The fact is, I want you as a witness," emphasizing the final word; "and a witness in a double sense. I desire you to witness the proceedings which will take place tonight, both as a man and a critic. Your critical observation is for yourself, your personal for me. Things may take place tonight which may necessitate your appearing and giving evidence in a court of law. Without such evidence I should be running a risk. I have selected you for a number of reasons, which I need not now mention. Are you willing to oblige me, and at the same time inform yourself upon the profoundest and most vitally important problem which can be presented to the human family—namely, the existence of individual intelligence after death; or, to put it in ordinary phraseology, the immortality of the human soul?"

To say that I was amazed at this speech of the doctor will scarcely express the condition of my feelings. Had late watching exerted (as it will frequently do) an unsettling influence upon the brain, so as to induce a train of fantastic ideas upon the subject most near to it at the moment? Or was the doctor, after all, really and actually an enthusiast upon the subject of spiritualism? A glance at the grave, kindly face before me, and the clear eye that looked penetratingly into mine, convinced me that the first of these theories, at all events, was not supported by appearances. As to the second, I had no means of determining at present.

"I am perfectly ready," I said, "and shall be glad to witness whatever you desire, though I do not quite understand your allusion to a court of law. Of course, I shall object to witnessing anything that might seem contrary to my notions of what is right."

"I pledge you my honor," returned the doctor, earnestly, "that though what you may witness will be totally unprecedented both in operation and in result, I will do nothing but what is perfectly admissible for a man of science to do, and nothing unbecoming a gentleman."

"Pardon my hesitation," I answered; "I shall be delighted to assist in any manner under these conditions."

As I finished speaking, the doctor opened the door and led the way to another portion of the house. I noticed, as we passed along, that a peculiarly pungent odor of chemicals pervaded the air; but I attributed this to the fact that the doctor probably compounded medicines in his own laboratory. We presently came to a door, which the doctor opened and motioned for me to follow. I found myself in a spacious and richly furnished chamber, evidently a lady's, and had no difficulty in recognizing, in the wan and emaciated figure, reclining on a couch near the fire, the lady to whom I had been previously introduced as the doctor's wife.

She was stretched at full length, with her head thrown back upon the pillow and her eyes closed. To my surprise, she was elegantly dressed in white satin.

"It is her bridal dress," explained the doctor, in hushed tones, as we noiselessly approached the couch; "it was her particular desire that the operation should take place under these conditions."

The operation! thought I. Ah! that explained it all. It was a new operation which the doctor intended to perform—possibly a dangerous one; and he desired my evidence in case it should not turn out as he expected. But why so if the operation were legitimate? It might be legitimate and yet new; and his desire for secrecy might arise from a wish to conceal its modus operandi from his brother practitioners. This solution of the matter seemed satisfactory.

While I had been thus meditating, the doctor had been bending over the lady, evidently feeling her pulse. He now rose to an erect attitude, and said:

"It is time that we should commence our preparations. I must ask your assistance to place my wife in the position necessary for the operation. We must carry her over there." Drawing aside the drapery, a strange spectacle was revealed. At the left-hand side there was set upon the floor a large oblong tank of glass, about seven feet long by three feet in and the same in depth. I had seen similar receptacles used as aquaria. Within this receptacle was placed a species of table, consisting of a long, narrow slab of plate-glass set upon supports of the same material.

A similar slab of plate-glass served as a lid to the tank, from the top of which projected a glass funnel connecting with a table of the same material which ran perpendicularly down to nearly the bottom of the tank, its end dipping into two or three inches of colorless liquid which already lay there. This tube and funnel were near the left hand end of the tank, while at the right hand end there was another apparatus as follows: Two glass tables, similar to the one I have just described, descended from the lid in the same, but not to the same depth. One ran down merely for a few inches into the body of the tank, and was there lengthened by a flexible india-rubber continuation ending in an inverted glass cup; while the other, with a similar termination, descended to within a foot and a half of the bottom. After emerging from the lid these tubes were bent at right angles, and extended to the side of another glass receptacle, nearly the counterpart of the first in all particulars, except that its longest diameter ran vertically instead of horizontally; in other words, it stood on end instead of lying flat on its longest side. From the ends of these tables projected wires, one of them ending at a point about midway from top to bottom of the tank, the other at a point some eighteen inches higher. These wires, I could now see, extended through the tables to the horizontal tank, their other ends projecting from the terminal glass cups. A few seconds sufficed to enable me to note these particulars, which, though inexplicable to me, were, at the same time, mechanically considered, very simple.

The doctor, after drawing aside the curtain and critically examining the apparatus, requested me to assist him in removing the massive glass slab from the top of the reservoir. This done he returned to where his wife was lying, kissed her, and placing his hand beneath her shoulders, asked me to take hold of her lower limbs, so that we could lift and carry her elsewhere. Guided by him we noiselessly raised the insensible body from the couch, and carried it toward the alcove. Still following his injunctions, we together lifted the inanimate form over the side of the tank, and laid it carefully upon the tabular glass slab that lay at the bottom, the doctor placing the forehead directly under, and in contact with, the lower glass cup I have previously referred to. I then assisted him to replace the massive slab, which served as a lid or cover, on the top of the tank. This done, the doctor regarded the tanks in rapt attention, while I stood silently by, waiting to see what would transpire. Presently an idea struck me with most forcible impression. That lady was not dead. An operation was about to be performed on her. These two facts I was aware of—I had them from the doctor. But there was another fact I was also aware of, and that was that this living woman was now shut up in an air-tight reservoir, and that, sooner or later, unless the air were renewed, she would infallibly be asphyxiated. I communicated my conclusion to the doctor.

"You are perfectly right," he assented, gravely. "A human being, or animal, in ordinary health, would speedily be suffocated under such conditions. But the lady before you is dying. Her respirations do not number three a minute. My knowledge of the case tells me that long before the store of air in that reservoir is exhausted, she will die of inanition."

"Will die of inanition!" I repeated, aghast. "What can you mean? What, then, is the nature of the operation you said you were going to perform to save the lady's life? Why do you not proceed with it?"

"I did not say I was going to perform an operation to save the lady's life," rejoined the doctor, slowly, and with marked emphasis on the latter words. "In point of fact, the operation does not begin until after her physical death."

"Then, sir," said I, "I consider you have deceived me. You have taken advantage of my supposed ignorance, or my supposed indifference upon such matters, to secure the assistance you could have obtained nowhere else for your unhallowed experiments. But you have miscalculated your man, sir. I care not if you are a representative man in the medical profession. I only know that you are acting in a grossly inhuman manner. I only know that this lady is not yet dead, and that you are waiting, by your own admission, for her death, in order to institute I know not what cold-blooded experiments upon her lifeless body. But I shall not aid or abet you in them; nor shall I witness them. On the contrary, I shall take immediate steps to have these proceedings stopped and investigated," and I walked toward the door.

"Stop!" called the doctor. "Do not touch that door-knob or you are a dead man. I anticipated that something of this nature might happen, and accordingly took the precaution to connect the door- handle with a fully charged secondary battery when we entered. See!" and he held out an iron rod, insulated by a glass handle, close to the door-knob. The quick flash which passed from the one to the other convinced me that I was in a prison more secure than the Bastille, and guarded by an incorruptible and inexorable warder.

"And now," said the doctor, "that you see the folly and fatality of the course you were about to pursue, I hope you will not again interrupt me in the progress of this operation. I dare not leave the neighborhood of my wife for an instant. I repeat the assurance which I gave you before, that nothing should be done derogatory to the character of a physician or a gentleman, and I beg you will believe it. None but the narrow-minded and depraved can impugn my motives or misinterpret my acts. Believe me that all which I value most in life lies mute and inanimate within that crystal casket at this moment, and that whatever you may witness is done simply and only for the good of her." And he again took up his position of watcher intently and earnestly before the reservoirs.

My scruples were not yet conquered, for the events and circumstances of the evening were not of the class to induce mental ease and confidence. I noticed, however, that the windows of the apartment were securely barred and bolted, and, for aught I knew, might be protected by the same unseen and deadly agency as the door. I felt, therefore, that it was folly for me to attempt to communicate with the outside world as matters stood, and so resolved to muster up all my moral energies in opposition to whatever did not strike my innate conceptions as being right and proper in the actions of the doctor himself.

From being profoundly subjective, I instantly became keenly objective. I appreciated the extraordinary situation I was in. In front of me, a woman dying; wan, emaciated, inanimate; shut up in an air-tight, transparent sarcophagus; clad, as if in mockery, in her bridal dress. At my side a sedate, intellectual-looking man, well past the meridian of life, watching, quietly but earnestly: watching, watching—for what? Myself, creature of circumstances, inveigled, entrapped into witnessing, I could not predict how much of the horrible or illegitimate, but utterly powerless to do more than protest.

I presently found the intense vigilance of the doctor becoming infectious. I, too, began to watch the figure before me with eager curiosity, though without the faintest conception of why I was doing so. I began to speculate upon the meaning and purpose of the tanks, tubes, and wires I saw before me. Suddenly a flash of light darted from the end of the lower wire in the upright reservoir to the end of the upper one. The flash was precisely similar to the one I had just seen pass from the doorknob to the insulated rod. The doctor started, and clutched my arm.

"Did you see that flash?" he asked, in suppressed tones. "Do you know what it means? The body which lies before you is dead. The spirit which animated it has passed from it. It is now in the other reservoir."

It now occurred to me that I had a madman to deal with, and the most dangerous species of madman, for there was certainly method in his madness. I had never been in a similar position before, but I had read that the best way to act under such circumstances is to feign acquiescence in the ideas and caprices of the lunatic. Escape was impossible, as I have previously intimated, and to thwart the man would, doubtless, have meant to provoke a hand-to-hand contest with the odds in his favor; for are not madmen possessed of superhuman strength and courage? I had always heard so; so I resolved to act with prudence, and to endeavor to lead rather than compel.

"Are you positive," said I, "that the lady is dead? Had we not better examine the body more closely, so as to arrive at absolute certainty? Had you not better send for another physician? Suppose I go and fetch Doctor B—. He lives only a block away. I won't be a minute."

I had also read that lunatics could be managed by diverting the current of their thoughts, and so made this attempt.

The doctor glared at me keenly for a moment, then said:

"There is no necessity for it. You can implicitly trust my diagnosis that my wife is dead. Even if the external appearance of the body were not sufficient proof of this fact, the electric flash which we just witnessed in the other reservoir, sets all doubts at rest."

"How so?" I inquired.

"Simply because soul, spirit, intelligence, the life principle, call it what you will, is neither more nor less than a form, a mode of that force which we call electricity."

"Then what are you?" I asked, carried away by the earnestness and gravity of the man, and forced to believe, in spite of myself, that there must be some meaning in the strange paraphernalia I saw before me. "What are you? A spiritualist? What is the meaning of all that I see here?"

"A spiritualist? Yes. A materialist? Yes. Strange as it may seem to you, I am both. Spirit is really and truly nothing but a form of matter. Nothing can exist which is not material. It is simply our blindness and ignorance which draws a distinction between matter and spirit. The soul is simply individualized electricity—an intelligent secondary battery, if you will; a storehouse of the life principle, capable of using and controlling all forms of co-existent matter. You will at once comprehend my reason for employing glass solely in the construction of all the apparatus. Perfect insulation is, of course, necessary to prevent the escape of the subtile principle within." And the doctor stepped to the interior of the alcove.

"I must now," he continued, as he drew aside a curtain and disclosed, upon a raised platform, a third reservoir, also of glass, and filled with some colorless liquid, "I must now proceed at once with the operation."

As he said this he introduced into an aperture in the top of the raised reservoir, the end of a bent tube which had been lying on the floor against the wall; placing its other extremity in the funnel on the top of the tank in which the body of his wife lay. He then withdrew the stoppers from the ends of the tube, and as this had previously been filled with liquid, the contents of the higher reservoir began to flow into the lower one through the syphon which was thus formed.

Inch by inch the level of the liquid rose in the lower reservoir; up the legs of the glass slab on which the body lay; up the sides of the slab itself, until it began to well around the form of the body. As the syphon was about two inches in diameter, a very few minutes sufficed to discharge the contents of the one reservoir into the other, and by the time the body was completely submerged, and the liquid had risen several inches above the face, and within about an inch of the cup at the end of the flexible tube, the doctor removed the syphon from the funnel, and stopped the discharge. I had now become so engrossed in the mystery of what I saw that I forgot my previous misgivings. I kept my eyes fixed intently on the horizontal reservoir before me. Presently a whitish vapor rose from the surface of the liquid. It rose from all points, as fog rises from the ocean. It moved in sluggish convolutions, permeating, pervading, and rendering opaque the clear, vacant space above the liquid. At the same time—could I believe my eyes?—it became apparent that the body was melting away. The white satin dress had already disappeared, and the exposed portions of the frame has assumed a deep yellow hue. There was no doubt of it, the body was being speedily corroded by some powerful chemical agent. I became faint and sickened at the spectacle, and, sinking back into a chair, closed my eyes.

"There is no necessity for our witnessing this stage of the operation," said the doctor drawing the curtain before the alcove. "Dissolution and decay shock our senses, because we unconsciously recognize in them a degradation of life, and life is our inestimable possession. But conceal the mystery as we may, whether in the recesses of earth, the chamber of a crematory furnace, or a bath of corrosive acid, the same end is reached—namely, the resolution of the body into its simple elements. I may add that there is nothing novel in the mode I am now employing. It was discovered some few months ago by an Italian savant, Professor Paolo Gorini, of Lodi, and is capable of completely destroying a human body in twenty minutes, at a cost of eight francs, the principal ingredient used being chromic acid."

I could now understand why the doctor wished my presence from a legal point of view, as, if what he stated was correct, and inquiry should be instituted on the disappearance of his wife, my evidence would be most important. Still I could not fathom the object of so disposing of a dead body. The circumstances were, to say the least, suspicious, and the presumption would be that such disposition was resorted to for purposes of concealment, and to evade a proper inquest into the cause of death. I accordingly stated my views upon the matter.

"I perfectly recognize," he answered, "the truth of what you say; but there need be no apprehension on that score now. The danger which I apprehended consisted in the escape of the electrical energy—otherwise the spirit—through some crevice or imperfect joint in the first reservoir, when it passed from the body, and before it was finally lodged in the second. Although, as I have explained to you, spirit is individualized electrical energy, it is yet, in a measure, amenable to the laws which govern electricity in the abstract. Although it was definitely agreed upon between my wife and myself that the vital element should pass from the reservoir, where her body underwent a physical death, into the adjoining receptacle, where its rehabilitation in its primitive form was to be consummated, and although a suitable conductor, in the shape of this lower wire, which ran, as you saw, from the neighborhood of her head to the interior of the second receptacle, was arranged so as to facilitate this transmission, yet there might have been, and most probably were, electrical influences, whose extent I could not possibly determine, outside the first reservoir, ready to exert an irresistible attraction upon the element within, had there been any possibility for them to do so. There was not. The crystal compartment was a perfect non-conductor. The flash of light which you saw pass from one wire to the other, about half an hour ago demonstrated that my wife's spirit was yet mistress of itself."

I was fascinated, in spite of myself, by the doctor's language. It was quiet, confident, and deliberate. In spite of the wild absurdity and apparent baselessness of his fantastic conceptions—as they then seemed to me—I caught myself speculating upon the materialistic theories of life and spirit, and confessing that such a solution of the vexed and mysterious problems of existence, here and hereafter, would reconcile many points apparently irreconcilable on any other hypothesis.

My speculations were interrupted by the doctor drawing aside the curtain and reentering the alcove. In the few minutes during which the reservoir had been concealed from view a great change had taken place inside. The milky, opaque, and cloud-like vapor which had filled its upper portion had disappeared. Judging from large drops which covered the glass, like beads of perspiration, or like the moisture with which window-panes are obscured on a frosty morning, the vapor had condensed, and was returning to the liquid mass below it. The body which had lain upon the glass slab was now resolved into an indistinguishable and formless congeries of porous matter, resembling sponge in color and texture, and literally melting and crumbling before our gaze. The doctor seemed satisfied.

"You will presently witness," said he, "the operations of that mysterious electrical agency called vital force or spirit, in its dealings with inorganic matter. This was my second reason for inviting you here tonight, as I wished to have an intelligent witness of this portion of the proceedings as well, and as I had promised at some time or other to explain to you the true relation of electricity to spiritual phenomena."

By this time the last vestige of matter had vanished from the slab where, half an hour before, we had laid the body of the doctor's wife. The liquid in the reservoir retained the same transparent appearance as ever.

The doctor then readjusted the syphon as before, between the reservoirs, and proceeded to decant more of the fluid from the one to the other. Slowly the liquid rose in the lower reservoir, till it reached the bell-shaped termination of the flexible tube, through which ran the second wire to the upright reservoir. At length the glass cup touched and floated on the liquid. After letting the surface rise about an inch higher, the cup rising with it, the doctor again disconnected the syphon.

A strange phenomenon now made itself apparent. There were, as I have stated, two wires, running from contiguous points in the vessel containing the fluid, through glass tubes, to contiguous points in the upright empty compartment. The lower end of each of these wires was now immersed in the liquid. From the end of each wire there immediately began to rise a train of tiny air bubbles, which broke at the surface of the liquid, and beneath the cups. It reminded me exactly of the vaporization of water effected by the galvanic battery, when both of its electrodes are introduced into the fluid; the two constituent gases, hydrogen and oxygen, being set free, as is well known, by electric action at their respective poles.

"You see," remarked the doctor, "that this part of the operation follows the ordinary laws of electricity. As soon as the poles of the intelligent battery in the upright compartment became united by contact with a common medium—namely, the fluid in the reservoir—disintegration of that fluid commenced. You will remark my use of the term 'intelligent' battery. An ordinary material battery would decompose merely so much of that fluid as consists of water—would liberate, in fact, only the two elements, oxygen and hydrogen; but the 'intelligent' battery, the spirit, is capable of exerting a much subtiler and a much wider force. It is now in process of liberating and attracting to itself, in the form of gas, every element which was originally decomposed and is now held in solution by the fluid on which it acts. Carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, sodium, sulphur, albumen—every element, in short, which once composed the body of my wife is now being extracted from that reservoir in the form of gas, and passing into the other compartment by way of these tubes."

As I examined the phenomenon more closely, I could see that several trains of bubbles were being formed at various points on those portions of the wires which were submerged in the fluid; and that each train rose, separate and distinct, to the surface, though all broke within the peripheries of the terminal cups.

"Each of these series of gas bubbles represents one of the elements composing the human body," explained the doctor, "and all are now passing into the other compartment, where they will be recombined in the form they originally went to make up. You will presently witness the real triumph of mind over matter. You will witness the mysterious and wondrous manner in which the intelligent battery, called 'spirit' or 'soul,' attracts, combines, and weaves together the various elements of inorganic matter which go to make up the vehicle through which it works, while confined therein, called 'body.'"

"The phenomenon of materialization, as evolved by genuine spirit mediums," went on the doctor, after a pause, "is an actual and bona fide phenomenon, for you will presently witness its accomplishment. The error the spiritualists fall into consists in supposing that the phenomenon is supernatural; and the public is misled by this consideration, and by the fact that in many cases it has been proved to be fraudulent, into inferring that the phenomenon is, in every case, fraudulent, and, consequently, that the spiritual hypothesis on which it is based is delusive and imaginary. When, however, both phenomenon and hypothesis are reduced to a scientific formula, there is no longer room for doubt or cavil."

"Then, you mean to tell me," I said quietly, for I had now passed beyond that mental stage in which I had recognized the doctor either as a lunatic or an enthusiast, and was content to be a passive spectator and commentator on whatever might transpire, "you mean to tell me that the body which has just been corroded and dissolved—the body of your wife—will be reconstructed and reincorporated in that receptacle?"

"I do," said the doctor, "and why not? The process which is about to take place is simply an expansion of a process which goes on about us, unnoticed and unremarked, which is nevertheless equally remarkable with this. What is the power which attracts steel filings to a magnet? You answer electricity. What is the power by which the seed, the germ, the egg of plant or animal attracts, combines, and modifies the various elements which are necessary to its sustenance and growth? You do not know. Of two seeds, apparently similar to the eye, planted side by side in the same soil, why is it that one attracts to itself certain salts and alkaloids, and grows into a nutritious vegetable, while the other attracts other salts and alkaloids—from the same soil, mind you—and becomes a plant whose appearance is repulsive, whose smell is rank, and whose taste is poisonous? Because it has an inherent power to do so, you answer. But when I ask you to explain the nature of that power, you are lost. We will call it, if you please, for lack of a better term, 'the vital principle.' One of its peculiarities is that it attracts affinities and begets likes. Now, the 'vital principle' of a human being, or the 'soul' or 'spirit,' as it is variously termed, is, as I have already stated, an intelligent battery, answering to the 'vital principle' in the seed or germ; both alike possessing individuality, the difference being that the former is intelligent, the latter instinctive. Now, following up the analogy, the human germ or egg possesses merely instinctive individuality, or the power to attract and appropriate such substances as are suitable to its corporate development and sustenance and within its reach. But when the life-principle becomes separated from its corporeal surroundings, it becomes endowed also with higher powers as an intelligent individuality. It then exerts control over matter to the extent and degree to which it was schooled while in the body. Do you follow?

"I think I comprehend the line of your argument," I assented.

"Of course, it is ridiculous to suppose that the immature intelligence of the still-born child, or the depraved intelligence of the barbarian, should possess powers coincident with those of the well-developed and well-conditioned being; and it is equally ridiculous to suppose that an intelligence should be placed here in a school of matter, and subsequently relegated to some immaterial condition where its past experience would be valueless. Nature does not deal in such wanton waste of energy as this."

"But," objected I, "how is it that if, as you assert, the phenomenon of materialization is an actual, natural, and scientific fact—how is it that such materialized bodies always disappear, vanish, melt into thin air, and leave no trace of their existence behind them? Why can not they retain their corporeality, so to speak, and remain as living, unimpeachable witnesses of the truth of the phenomenon? This would end all doubt about the matter, and set argument at rest forever."

"That fact is also dependent," replied the doctor, "upon a simple, natural law. Just as a magnet exposed to undue or prolonged excitement will part with its magnetic property and become powerless to attract until re-charged with the electric fluid, so the intelligent battery, or spirit of a man, though competent under certain conditions to attract to itself from surrounding space all the elements necessary to reconstruct the body it formerly inhabited, is incompetent to retain them in their forced combination for any considerable length of time. Why, consider, my dear sir, the gigantic expenditure of force necessary to bring together from the atmosphere the necessary quantities of all the alkaloids, metals, and gases which go to make up the material constitution of the human body! Areas of atmosphere, leagues in extent in some cases, have to be ransacked for the necessary elements. The energy exerted in doing this is tremendous, and the magnet, in effect, becomes demagnetized—hence the inevitable disintegration which follows. It is needless to criticise the natural provision in this—it is obvious. Besides, the spirit has explored new fields, has entered new conditions, and come under other influences since leaving the body, and, it may be safely predicated, would not resume its former existence if it could. But, in the case of my wife here, the conditions are altogether different. Her spirit has come under no extraneous influence, and requires to exert but a moderate amount of energy to attract and recombine the constituent elements of her body, as they are all within easy reach, and are even now undergoing the process of reincorporation."

I cast my eyes on the upright glass compartment into which the gases liberated from the fluid by the wires were passing, as the doctor said, through the insulating tubes. The extremities of both wires—I could now judge that they were about eighteen inches apart—seemed to be enveloped in a pale, lambent flame, while in the vacant surrounding space a wonderful scene was visible. A luminous, nebulous mist, seeming to roll and convolute upon itself, by turns bright and dark, transparent and opaque, now here, now there, but endowed with marvelous and incessant activity was more marked and the mist more luminous in the immediate vicinity of the ends of the wires. Even while we looked it was evident that a gradual change was coming over this cloud-like substance. The homogeneous mist began to resolve itself into individual atoms. Myriads of tiny, shining globules shot hither and thither, wheeling, darting, turning on themselves in seemingly endless convolutions. The eye was pained and the sense of vision bewildered in attempting to follow their movements. As the peculiarity of the first stage of the phenomenon lay in general motion, so the second lay in individual or specific. The whole scene impressed one with the idea of life—fervent, intensely active, purpose-teeming life. After a further interval—how long I know not, as my interest was so keenly aroused by what I saw that I became oblivious of time—a multitude of the vibrating molecules seemed to arrange themselves in a fibrous network around the two central nuclei, at the extremities of the wires.

"Those myriad atoms that seem to be instinct with life and motion, do you know what they are?" asked the doctor. "They are the factors of the original bioplasm—the physical basis of all organic life, whether vegetable or animal. The controlling agency at work can produce any of life's protean forms at will if possessed of a knowledge of the proportions necessary for their construction. Only the higher intelligences, however, possess this knowledge."

"That delicate network which is being woven around the wires—what is it?" I asked, carried away by the wondrous spectacle. "See: it spreads farther and farther from the centres, as if an invisible loom were at work upon its fairy texture! Inch by inch it grows under our gaze. Now the borders of the two parent nuclei have united. The upper one assumes the outline of a head, the lower of a heart. The network is spreading in every direction. It seems to take on the outline of shoulders, of arms, of legs."

"That mysterious network," replied the doctor, "constitutes the muscular and nervous tissue. It is one of the simplest products of bioplasm, consequently among the earliest formed. It is a point of distinction between a body developed from an embryo and a body formed as we see it now, that the organs in the former case are simultaneously developed, while in the latter simplicity of structure claims priority of production."

While he was yet speaking, the fibrous tracery assumed the distinct form of a human being, and along specific lines of the figure flowed and ebbed a colorless ichor, which gradually took on a reddish hue, and around the endless ramifications of which grew a series of thin, transparent envelopes, which I had no difficulty in classifying as veins and arteries. The changes of appearance were so kaleidoscopic and unexampled in their rapidity, that almost before I had time to appreciate the significance and memorize the particulars of one phase of this spectacular lesson in anatomy, another had taken its place. A glimpse of the different internal organs of the body was rapidly obscured by an ever-thickening veil of flesh, through which the form and structure of the bones was rather felt than seen. By the time that I became fully conscious of all the changes that had taken place, a female figure of rare loveliness stood before me, clothed in a white satin dress. I recognized the dress as that which the doctor's wife had worn when we consigned her to the reservoir about an hour before, as my watch told me, though the occurrences of the evening seemed to occupy a week. I recognized, as I said, the dress, but I did not recognize in the figure that stood before me—a perfect type of feminine health and beauty—the wan and emaciated lady whom I had known as the doctor's wife. The body smiled, nodded, and spoke, though the thickness of the glass was such that the latter action was only evidenced by the movement of the lips. The doctor's face wore a joyful and triumphant expression, as he beckoned to the lady and pointed to the bottom of the compartment. The signal was probably prearranged, for it was at once understood. The lady stooped, raised a small lid from a box-like receptacle, and took thence a piece of bread, some fruit, and a glass of water, and began to eat and drink.

"This," said the doctor, "is the most essential proceeding of all. Although my wife's body is perfectly materialized, the fact must not be lost sight of that it can be resolved into its component elements again as speedily as it has just been reincorporated, by the converse of the method just employed. In other words, by the failure of that individual vital energy which served to materialize it. The only way in which this result can be counteracted is by introducing into this corporeal, yet ethereal, body a sufficiency of ordinary food, the digestion and assimilation of which acts as an indissoluble link between the various component parts of the organism, and builds up an impregnable barrier against dissolution or dematerialization. It is essential that my wife should remain where she is until the natural vital processes are in full play, and in order that she may not be suffocated meanwhile I must immediately bring my force and exhaust pumps into action to supply that air-tight compartment with pure air." And the doctor walked to another part of the alcove and began to manipulate the pistons of an air-pump which connected with the compartment his wife was in. "Two hours," he continued, "will suffice for all purposes, and my wife will then be free. I will beg you to relieve me from time to time, as the operation is fatiguing."

I expressed my willingness to do so, and fell to speculating on the marvelous occurrences I had just witnessed. Absurd and incredible as it had seemed to me an hour before, the result was there. The mystery of existence had been probed and solved, and the substantial evidence lay in the lady, who was now sitting upon a narrow glass bench, which had escaped my observation, at one side of the compartment, and smilingly watching the doctor, with whom she was keeping up an animated sign correspondence. I was suddenly startled by an abrupt exclamation from the doctor.

"Great God!" he cried, "what is to be done? The valve of my force-pump is broken! The exhaust cylinder is safe, but of what use is that if I can not supply air to be exhausted?" and he approached me with agony depicted on his brow.

I glanced at the lady, and saw by the uneasiness she manifested—she had risen from her seat and was anxiously making signs to us—that she thoroughly appreciated the nature of the catastrophe. In another moment she held her hands up to her head and sank heavily down upon the floor of the compartment. There was but one course to pursue. To leave her where she was meant asphyxiation. To release her could not possibly be worse, perhaps not so bad. The doctor understood this but vacillated at the idea of the nullification of all his efforts. I sprang to the compartment, put my shoulder against it and endeavored to move it. It was too firmly based to move. Looking around I espied a hatchet lying near, and with one blow shivered one of the plate-glass sides to fragments. It was the work of a moment to drag out the lady, and by this time the doctor had recovered from his temporary weakness, and was at his wife's side. She had fainted away, and the bloom had died from her cheek. Instinctively I rushed to a sideboard and seized a water-jug and decanter. The contents of the first I threw into her face, the latter I put to her lips. As we knelt there beside her it seemed as if she were again melting away into the ethereal essence whence she had originated.

The satin dress became filmy and lost its lustre. Through its texture could be seen the skin, and the strange molecular motion with which I had become familiar in the reservoir, was again discernible in the surface portions of the frame. There was no room to doubt that the converse of the process of materialization just witnessed was being enacted beneath our eyes. In a few short minutes the component elements of her body would be disintegrated, and the lady who had been so mysteriously restored to life and health would once more vanish into nothingness, and blend with the surrounding atmosphere.

Hurriedly and abruptly the doctor spoke:

"Extreme measures must be taken," he said. "The time has been too short for the food she has partaken of to assimilate. Her body will disintegrate unless something can be introduced into the system which goes straight into the blood. There is only one substance which possesses this property, and that is alcohol."

So saying he grasped the decanter and poured about a glassful of its contents, which were brandy, into his wife's mouth. The effect was instantaneous. The body which seemed to be fading away under our very eyes, began to resume solid corporeal proportions.

The dress, on the other hand, continuing to become more filmy, the doctor hastily enveloped his wife's form in such wraps as lay near.

"The force which materialized the inorganic matter composing the dress," explained the doctor, "has no power to preserve its elements from disintegration, since nothing can be introduced into its texture capable of intimate assimilation therewith, as is the case with organic matter. It is, as I have said, the ability to weave and knit a homogeneous substance into the organic tissues of the body that alone prevents that disintegration which a short time ago was imminent. The human body, as you know, is ever renewing itself and wasting away. Little by little the tissues which have just been materialized will be replaced by fresh matter constantly being assimilated through the organs of nutrition. Even the introduction into the blood of the small quantity of alcohol just used will suffice to arrest molecular disintegration until the digestion of the food proper shall have taken place. After that there is nothing to fear."

In a few minutes the lady opened her eyes, looked around her, and embraced her husband. We had triumphed. About two hours afterward I took my leave, the doctor assuring me that digestion and assimilation had now done their work, and inextricably woven their material texture into the ethereal tissues of his wife's frame.

A week after, when Mrs. S— reappeared in society, all the friends of the family were amazed at her sudden change from the condition of a dying consumptive to one of a lady in the full flush of youth and health. None, however, knew the secret of this change but the doctor, myself, and now, for the first time, the readers of this narrative.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.