RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Alexey Kuzmich Denisov-Uralsky (1863-1926)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Alexey Kuzmich Denisov-Uralsky (1863-1926)

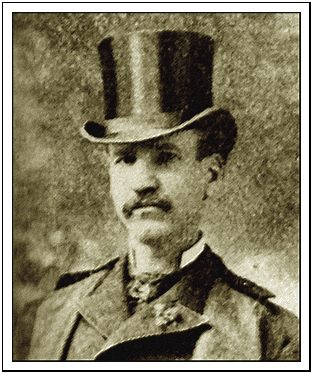

Robert Duncan Milne (1844-1899)

THE Scottish-born author Robert Duncan Milne, who lived and worked in San Fransisco, may be considered as one of the founding-fathers of modern science-fiction. He wrote 60-odd stories in this genre before his untimely death in a street accident in 1899, publishing them, for the most part, in The Argonaut and San Francisco Examiner.

In its report on Milne's demise (he was struck by a cable-car while in a state of inebriation) The San Fransico Call of 17 December 1899 summarised his life as follows:

"Mr. Milne was the son of the late Rev. George Gordon Milne, M.A., F.R.S.A., for forty years incumbent of St. James Episcopal Church, Cupar-Fife. and nephew of Duncan James Kay, Esq., of Drumpark, J.P. and D.L. of the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright, through which side of the house, and by maternal ancestry (through the Breadalbane family), he was lineally descended from King Robert the Bruce.

"He received his primary education at Trinity College, Glenalmond, where he distinguished himself by gaining first the Skinner scholarship, which he held for a period of three years; second, the Knox prize for Latin verse, the competition for which is open to a number of public echools in England and Ireland, and thirdly, the Buccleuch gold medal as senior and captain of the school, of the eleven of which he was also captain.

"From Glenalmond Mr. Milne proceeded to Oxford, where he further distinguished himself by taking honors, also rowing in his college eight and playing in its eleven.

"After leaving the university he decided to visit California, a country then beginning to be more talked about than ever, and he afterward made the Pacific Coast his residence. In 1874 Mr. Milne invented and exhibited in the Mechanics' Fair at San Francisco a working model of a new type of rotary steam engine, which was pronounced to be the wonder of the fair.

"While in California Mr. Milne for a long time gained distinction as a writer of short stories and verse which appeared in current periodicals. The character of his work was well defined by Mrs. Gertrude Atherton, who said:

"'He has an extravagant imagination, but under it is a reassuring and scientific mind. He takes such a premise as a comet falling into the sun, and works out a terribly realistic series of results: or he will invent a drama for Saturn which might well have grown out of that planet's conditions. His style is so good and so convincing that one is apt to lay down such a story as the former, with an anticipation of nightmare, if comets are hanging about. His sense of humor and literary taste will always stop him the right side of the grotesque.'"

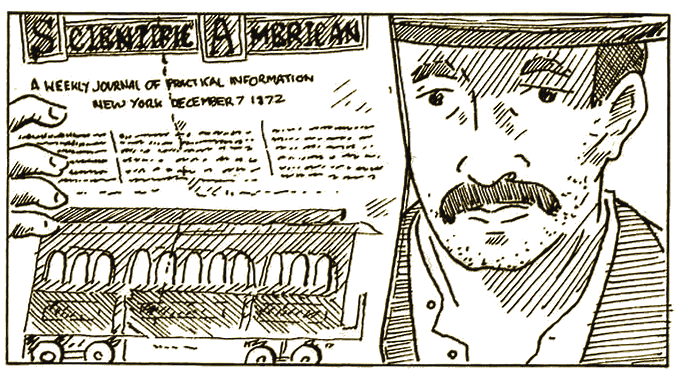

A caricature showing Robert Duncan Milne and a San Francisco cable-car.

IT is doubtful whether a more terrible or agonizing position can be conceived for a human being than to be compassed around by fire, every avenue of escape barred by the devouring element, and nothing ahead but the horrible certainty of being roasted alive, more or less slowly according to the nature of the surroundings. One generally associates the idea of the most fatal and hopeless conflagrations with buildings, but fraught as the burning of a large hotel or theatre may be with desperate situations, there are occasional instances in the free air and under the open canopy of heaven which may match any fiery ordeal ever bounded by four walls. Nor have we to look so far as the broad plains of Texas or its adjacent territories for instances like these. California sometimes supplies situations which, while they may lack the grandeur of dramatic breadth of the prairie fire, with its herds of fleeing buffaloes, its leagues of blazing grasses, and its desperate horsemen, nevertheless involve conditions of terror and peril comparable, within circumscribed limits, to those evoked by the red demon of the prairie.

The North of the Gualala River, which divides Sonoma from Mendocino County, is one of the principal logging centers of the state. The high bluffs overhanging the stream on either side merge, in their turn, into steep slopes reaching back into interior altitudes covered with redwood forests, and in many places rendered almost impassable by thick undergrowth or brush known in the vernacular by the generic term chaparral.

One sultry afternoon, not many summers ago, the loggers and mill hands in Harmon's Mill were taking their customary noontide hour of rest before resuming work. The mill and cabins where the men live are built upon some more than usually level bench land shelving from the river bank, while above and beyond the country slopes, away into cañons and mountain ranges more or less denuded of timber in proportion to their accessibility, and here and there covered, in tracts sometimes of many hundred acres in extent, with dense scrub growth and chaparral, through which the wayfarer has to work a slow and tortuous passage, keeping in view the general direction he desires to travel in, and pushing his way between or around the clumps or masses of brush as best he can. Now and again bare patches of a few rods in extent break the monotony of the wilderness of chaparral, but these are the exceptions, and not the rule.

"Mighty hot day," remarked Tom Briggs, as he got up from his reclining position, in which he, with half a dozen more of the mill hands, was in the habit of taking his after-dinner 'lay-off' on the shady side of the dining shanty. "Goin' to hev a purty tough time snakin' them big logs outen Little Creek Cañon, I guess. Mout's well hitch up them bulls an' be done with it, though," he added, philosophically, knocking the ashes out of his pipe and stretching himself preparatory to taking his departure.

"Seems to me this heat ain't natural," put in Long Jim, the tie-splitter. "There's a sort o' stifle in the air, too, that don't seem to smell right."

"Look up yar!" exclaimed Humpy Dick, pointing up the slope in front; "d'ye see that glimmer in the air? I'll bet that's fire."

The words had scarcely left his mouth when another logger joined the group.

"Boys," he said, hurriedly. "Little Creek Cañon's afire. Ef suthin' ain't done mighty quick we'll lose a terrible pile o' wood, to say nothin' o' the stannin' timber ef she spreads to the back ranges."

The camp was soon in commotion throughout its length and breadth. Parties were speedily organized, and set off in different directions to "head off" the fire and arrest its progress at all the strategic points in the neighborhood. Tom Bridges, the bull-whacker; Long Jim, the tie-splitter, and Humpy Dick, the logger, formed the members of one party that started up the right bank of the cañon. This bank was almost denuded of trees, but thickly covered with brush, through which the flames were now running riot, but steadily moving onward and upward. Suddenly, an exclamation from Humpy Dick caused the party to look in the direction toward which he pointed. There, not five hundred yards ahead of them, but lower down the slope, could be seen the thinly clad figure of an Indian girl, with something in her arms, frantically trying to make her way up the steep side of the cañon to a point which would be out of the reach of the advancing flames.

"I swar!" cried Tom Bridges, "that's Indian Meg. An' she's got her baby with her. Been a-berryin', sure, an' got caught afore she cud get out."

"Keep up the cañon, Meg," shouted Long Jim, making a speaking trumpet of his hands. "It's yer on'y chance. Ye'll never get out o' the way ef ye try to mount the hill."

Whether it was that the girl did not hear the advice given her by the woodmen, who were now themselves making the best of their way through the chaparral, above the track of the flames, or whether she considered that the safer course lay in getting to a position, like theirs, above the fire, it was impossible to tell. The only thing certain was that the poor creature, who was madly trying to steer her way through and around the compact masses of brush wherever opportunity offered, would never be able to reach a point of safety by following a diagonal coupled with an uphill course. Had she kept straight up the cañon, trusting to the woodcraft of the loggers to head the flames, she might possibly hold her own in the race for life, but as it was, with every yard she progressed the flames were steadily and surely gaining on her.

By this time, by almost superhuman exertions, the loggers had gained a point nearly abreast of the front line of the advancing fiery column. Half a mile below them, at the bottom of the cañon, they saw and hailed another party of their comrades, who were preparing to fire the chaparral in front of the mass already burnt--employing the old tactics of stopping the fire by depriving it of fuel, at the same time keeping the newly fired brush well in hand, by putting it out after it had run a few yards. Less than two hundred yards below them was poor Indian Meg, now dazed and blinded by the heavy rolling, dense blue smoke from the burning brush scarcely fifty yards behind her, hugging her baby to her breast and rushing aimlessly hither and thither among the masses of chaparral she could no longer see her way out of, but still untiring in her efforts to escape.

"Durn me ef I kin stand that," shouted Long Jim with an oath, making a dash, hatchet in hand, for a dense thicket some fifty feet in advance of the crackling flames. "Follow me, pards, an' see ef we can't get to Indian Meg afore the fire. Burn the stuff right ahead o' ye. Let the hull durned cañon go to blazes." And so saying the woodman disappeared among the blinding smoke. His comrades were not slow to follow him.

A quarter of an hour later, when the party which was beating out the fire from the bottom of the cañon up the slope came upon one of those little open areas, or blue patches, which occur at intervals among the chaparral, they encountered a sorrowful spectacle.

They came upon the charred and blackened body of Indian Meg, lying face down upon the ground, every vestige of scanty clothing burned away; beside her stood Long Jim, his face the color of charcoal, not a hair of his beard or on his scalp left, his shirt and overalls in blackened tatters, his boots yellow and cracked, his hands and arms blistered to a jelly, but nevertheless holding Meg's baby, which smiled merrily upon the surrounding group.

"I wuz too late," said Long Jim, in explanation, "to save the poor critter. The flames hed passed over her afore I come. Thar she wuz, jest as ye see her now, but the papoose was below her, an' she died keepin' off the smoke from its little lungs."

It was only an Indian squaw burned and an Indian baby saved. It was only a handful of rough woodmen engaged in fighting a few hundred acres of burning brush upon a Mendocino hillside; but it may be doubted whether the material instinct could have been more forcibly exhibited by any representative of the more civilized races, or whether more disinterested heroism could have been shown in fire or battle than on this occasion by a simple logger of the Gualala in an effort to save an Indian woman and her baby.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.