RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

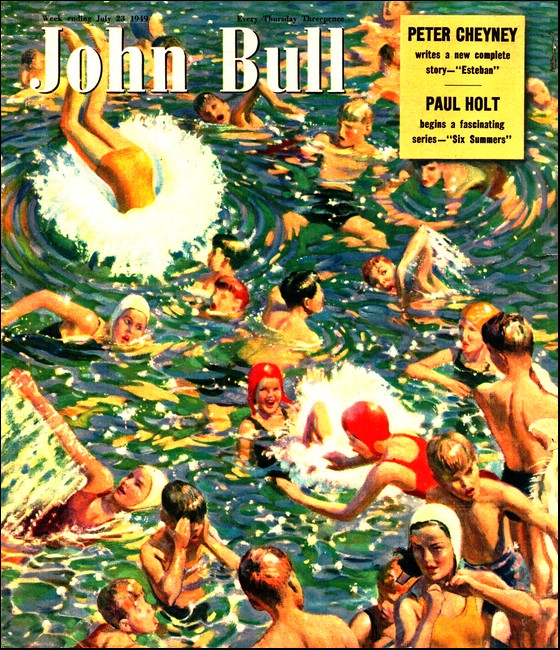

John Bull, 23 Jul 1949, with "Esteban"

Da Silva, the cattle rancher, was really stupid

not to allow his lovely daughter to

marry Esteban. Such a handsome rogue was far safer in the family than

out of it.

ESTEBAN came out of the shadow of the mangrove swamp, began to

walk along the winding cattle track that led towards Bana.

He was tall, slim and rangy. His skin was tanned to the colour of liver. His face was long but with humour lines about the mouth. He had soft brown eyes; white, strong teeth. He walked with a swagger, the Spanish spurs on his cuban-heeled cow-boots jangling. He wore dark, tight-fitting Spanish trousers wide over his boots, with a broad, tarnished silver stripe down the sides; a blue shirt open at the neck, a black, tight-sleeved bolero.

There were silver neck-cords on his sombrero. The black, pencil-line moustache above his attractive mouth gave him a cynical and sardonic expression which was belied when he smiled, and showed his white teeth. Round his waist he wore a wide gaucho belt studded with medallions. Over this was a pistol-belt with an American .45 automatic in a black holster on one side.

When he neared the coppice he whistled and the pinto walked out of the shadows towards him.

The horse looked rather like Esteban. It was a dun and rangy pinto and when you looked at it you thought that the high pommelled saddle, with its cow rope horn and Mexican back, was too big for it. Esteban swung himself into the saddle with a lithe and easy movement. He skirted the coppice; put the pinto into an easy canter. He rode through the heat of the afternoon. It was six o'clock when he arrived at the Anzanas shack. The shack, built of forest logs, plaster and mud, was set in a remote clearing towards the edge of the forest. It was a secret place, near enough to the cattle-grazing country to be dangerous—for the cattle owners.

Esteban dismounted; lighted a long, thin cigarro. He walked round to the other side of the shack. Olé Anzanas and his brothers, Pedro and Quincho, sat, swinging their legs over the edge of the broken-down veranda. Between them were two bottles of cachasa—one of them empty. They smoked brown, Spanish cigarettes. They looked bored, dirty and dangerous.

Olé said, his dark face wrinkling into a grin: "May the good saints preserve us... look who comes...!" He spat on the ground.

Pedro Anzanas said: "Good day to you, Esteban. How my heart bleeds for you. We have heard your sad news!"

Esteban shrugged his shoulders. "You are entirely wrong, Pedro. My news is not sad. Merely a little postponement of my happiness, I assure you."

Quincho said: "Yes...? Amigo, what madness persuaded you that da Silva would allow you to marry his daughter?"

Esteban sat down on the ground, cross-legged. Pedro Anzanas picked up the half-empty bottle of cachasa; threw it towards him. Esteban caught it adroitly; removed the cork; put the neck of the bottle in his mouth and drank.

Then he said: "My good friends, you will listen to me. Business is very bad for everyone these days. It is practically impossible for a gentleman to make any easy money, but I have an idea."

Quincho said: "May the good saints preserve us...! Esteban has an idea...!"

Esteban shrugged his shoulders again. He said: "I am informed by my beautiful Pilar, who adores me, and who is stupid enough to have a father like da Silva, that three days ago da Silva, for a reason best known to himself, insured his newly bought cattle with an insurance society near Zusta."

Olé said: "Why should he do a thing like that?"

Esteban smiled. "Possibly he'd heard that you had moved to this district, Olé. Now, figure to yourself, my heart goes out towards da Silva even though he has refused to consent to my marriage with his daughter. I have an idea that he needs money. I would like to help him."

Quincho grinned. "Madre de dios... it must be wonderful to be helped by Esteban!"

Pedro Anzanas said: "Keep silence... this should be good."

"I assure you it is," said Esteban. "Briefly, my idea is this. You, Olé, you, Pedro, and you, Quincho, are also very short of funds. I understand cattle raiding has been a little difficult of late because always the rurales are looking for cattle thieves. That is, of course, unless one has enough money to square Mendanda, our respected police chief. But supposing that tonight somebody were to cut out five or six hundred of da Silva's cattle, drive them over the mountain into the valley, do you think that, having insured this cattle, da Silva would worry too much about reclaiming them?"

Quincho said: "Possibly not. Perhaps he would rather have the insurance company's money."

Olé nodded.

Pedro said: "There is reason in this."

Esteban went on: "My idea is that tonight you should drive five or six hundred of the cattle over the mountain into Silver Valley. You three could do it easily. You are good llaneros."

Olé said: "All things are possible to men of good heart. What do we get out of this? It is one thing to have six hundred head of cattle in Silver Valley, but another thing to dispose of them, especially if they are branded."

Esteban said: "Half of da Silva's cattle are not yet branded. They came in only a week ago. This is the reason why he has insured the herd. Anybody's brand could go on them. There is always a good market for unbranded cattle. In fact," continued Esteban airily, "I will go so far as to say that I will find a purchaser for them. And at a good price." He picked up the cachasa bottle; took another swig. He threw the bottle to Olé.

Olé flipped off his Mexican sombrero with the back of his hand. Underneath was a sweat-soiled bandana handkerchief. He loosened the knot, wiping the sweat from his forehead. "I think the idea is good," he said. "Tonight we take the cattle. Tomorrow they will be in Silver Valley. We will take only the unbranded. When the time comes Esteban can come to us with an offer." He looked at Esteban. "Is this agreed?" he asked.

Esteban got up. He shook a little dust from his trouser leg. "My friends, I knew I could rely on you. You shall hear from me. Adios, and may the saints preserve you."

WHEN the evening shadows lengthened Esteban came down the

trail that leads from Zusta. He dismounted and took a track by

the side of a little wood. On the corner, standing beneath the

tree where they had always met, stood Pilar da Silva.

Pilar was tall and slim and curveful and beautiful. When she smiled her oval face was illuminated and her white teeth flashed.

Esteban kissed her hands. He said: "Now for me the sun has come out. How is it with you, my Pilar?"

Her face became serious. "Esteban, I am worried about my father. Last night by some means the corral gates were left open. Over six hundred head of cattle are gone. He is almost beside himself."

Esteban cocked one eyebrow. The movement gave his face a pleasant Machiavellian expression. He said: "But, carissima, surely the cattle are insured?"

She nodded her head. "That is so, but they were unbranded, because my father has been ill and occupied, and that is what makes it serious. He says that because the cattle are not branded the insurance company will be angry and suspicious. You know they insist always on stock being branded. Today, Señor Pravis, his lawyer came to see him. Pravis said that it would be a good thing for my father to offer a reward immediately; to deposit five hundred dollars for the reward with Señor Mendanda, the chief of police—the reward to be paid to anybody who could give any information as to where the cattle are. Pravis said this would give the insurance company confidence in my father."

Esteban said: "A good idea. Has he put in the claim on the company?"

She nodded. "He has reported the loss to the company's agent in Bana. He has claimed the insurance."

"That is excellent," said Esteban. "No one, I suppose, my sweet, knows anything about the cattle?"

She shrugged her shoulders prettily. "You know that in this part of the world there are lots of cattle thieves. It is almost too easy for them."

Esteban put his arm about her. He led her slowly back towards the track down by the side of Hie wood.

He said: "Return to your home, Pilar. Have confidence. All will be well."

She turned towards him. "I would care about nothing if my father would allow me to marry you."

Esteban smiled, he made a grandiose gesture with his right hand—an all-embracing gesture. He said: "Have faith, cara. Have faith in Esteban. Adios, my little chicken."

He watched her until she was out of sight. Then he returned to where he had tethered his pinto; mounted; rode off in the opposite direction.

IT was eight o'clock when he arrived at the small adobe hut in

which old José, an ancient range rider, lived. He found José in

the main room of the hut leaning over a bottle of cachasa.

José was old and fat and grey-haired, but there was the same

cunning twinkle in his eye, the same broad smile of welcome.

He said: "God be with you, Señor Esteban. What brings you to my poor abode? I am ashamed of it, but everything I have is yours."

Esteban sat down on the rickety stool. He said: "If that is so, my friend, we will start off with the cachasa."

José pushed the bottle across the table. Esteban took a long swig.

He said: "Listen, my old gaucho... times are hard and I think that a little happiness should come into your life. How would you like some money?"

José wrinkled his nose. "I would like it very much. How much money, Esteban? And what do I have to do for the money this time?" He grinned wickedly.

Esteban said: "Figure to yourself, my José. Last night six hundred head of unbranded cattle were stolen from da Silva's corral on the other side of the mesa. They have disappeared."

José shrugged his shoulders. "Why not? Since I was a little boy cattle have been disappearing in this country."

Esteban nodded. "Precisely, my friend. Last week the cattle were insured and da Silva thinks that the insurance company may be suspicious because they were unbranded, so, in order to regain the company's confidence, he has deposited a reward of five hundred silver dollars with Mendanda, the chief of police, for information as to the whereabouts of his cattle. You, José, will go at once to see Mendanda. You will give him information about the cattle."

José said: "For all that money I would give information to the Devil himself. What do I tell Mendanda?"

"You will tell Mendanda what is in effect the truth. You will tell Mendanda that last night was a lovely night. You could not sleep, so you mounted that ancient pinto of yours and rode over the mesa, and you saw Olé, Pedro and Quincho Anzanas driving da Silva's cattle towards Silver Valley. There is, as you know, a canyon at the end of the valley which is an ideal hiding place for a herd, and that is where the cattle are. You will demand the reward."

"But of course," said old José. "Naturally."

Esteban said: "Listen. Mendanda will know that what you say is probably true. He will know that Olé, Pedro and Quincho are among our most expert cattle thieves. He will suggest to you that he will pay you half the reward and keep the one half for himself. You know Mendanda?"

José shrugged. "Who doesn't?"

"Very well," said Esteban. "You will agree to this. You will take the two hundred and fifty silver dollars, and I shall call on you tomorrow morning and collect half. Is it agreed?"

José got to his feet. "Señor Esteban, I am already on my way."

Esteban said: "Good, José! When you die may your grave be covered with flowers for ever."

"A superb thought," said old José. "God go with you, Señor Esteban."

THE shadows had lengthened into darkness when Esteban threw

the reins of the pinto over its head on to the ground and

walked to the Anzanas shack.

Olé said: "Good evening, Esteban. The night is better for your presence."

Esteban said in his pleasant voice: "There is a little trouble, but nothing of importance."

Pedro said: "Always in the lives of great men there is trouble. What has happened, Esteban?"

Esteban shrugged his shoulders. "Consider, amigos, that last night some wastrel, who should have been better employed, observed you driving da Silva's cattle over into Silver Valley. Unfortunately, in order to regain the confidence of the insurance company, da Silva has deposited five hundred silver dollars with Mendanda as a reward for information about the cattle. Therefore, this wastrel, who observed your movements, will go to Mendanda, our esteemed chief of police, to claim the reward."

Pedro said: "If I knew who this dog was I would slit his throat. There is nothing worse than an informer."

Esteban squatted on his heels, carefully evading his long spurs. He said: "Be of good cheer. A little thought and all is made easy. Olé, you know the police corral beyond the Zusta road—the corral which our chief of police built for wandering cattle?"

Olé nodded. "I know it well."

"It is empty," said Esteban. "So, when it is a little darker, you and Pedro and Quincho will ride to Silver Valley and drive da Silva's cattle into the police corral. You see?"

Olé began to laugh. "This is very good...!" He turned to his brothers. "Understand, my brothers, we are to be public benefactors. We find da Silva's cattle which had wandered because somebody had left the corral gates open, so we drive them into the police corral. Esteban, you are a great man." His face became serious. "But what about us?" he asked. "We are to be public benefactors. We save da Silva a great deal of money. Are we to do good work and get nothing for it?"

Esteban said: "Listen to me. When this informant goes to Mendanda and tells him that he saw you stealing da Silva's cattle, Mendanda will never think for one moment that the cattle have been driven to the police corral. So what does he do?"

"It is obvious," said Olé. "He will arrest us. He will throw as into that filthy jail in Bana."

"Precisely," said Esteban. "So you go into jail wearing the expressions of martyrs. When you have been there a few hours I will arrange that the cattle are discovered in the police corral, and you, who are public benefactors, have been thrown into jail like common cattle thieves. And Mendanda, in order to save his own skin, in order that the whole population of Bana shall not laugh at him, will pay you the half of the reward which he has kept for himself. He will give you two hundred and fifty silver dollars. This I will arrange because you are my friends."

Olé got up. He said: "Come, my brothers, we have work to do. Esteban, as always I rely on you."

"So be it, amigos," said Esteban. "When I leave you the moon goes out. I am desolate."

Pedro said: "For us it is worse, life is miserable when you are not within the range of our eyes."

THE next morning, on his way to Bana, Esteban called at the

hut of old José and collected a hundred and twenty-five silver

dollars. These he divided and slipped into his boot tops. He rode

leisurely towards Bana.

At ten o'clock he entered the office of Cardona, the insurance company's agent, at the end of the little street.

"Señor Cardona," began Esteban, "I have always had a great appreciation of your mentality. Always I have said to my friends there is no greater representative of an insurance company than Señor Cardona. Always he has the good of his principals at heart."

Cardona nodded. "I am grateful for your good opinion."

Esteban crossed his legs; listened to the pleasant jingle of his spurs as he did so.

He said: "Señor Cardona, information reaches me that a large number of the cattle of my esteemed friend and, I hope, prospective father-in-law, Ramon da Silva, have disappeared. I understand that he has already made a claim against the insurance company. Is that true?"

Cardona nodded. "It is indeed true. The sum involved is considerable. It is perhaps unfortunate that the cattle were unbranded."

Esteban said: "Possibly there were good reasons for this. Da Silva has been ill and occupied. At the same time the company will be forced to pay. It would be bad publicity if they didn't."

"True," said Cardona. "They will pay eventually."

Esteban nodded. "Señor Cardona, I wish to do you a good turn because I have always liked you. I can save you and the company a great deal of time and money. When I leave here I propose to call on our respected and esteemed chief of police, Mendanda. I propose to give him certain information, as a result of which I assure you, Señor da Silva's cattle will be returned to him and the claim which he has made against the insurance company will be withdrawn."

Cardona smiled. "This is very pleasant news. You are indeed my friend, Señor Esteban. My principals on the mainland will be thrilled at the news."

Esteban raised one finger. "One moment. Señor... you will agree with me that the lowest peon is worthy of his hire. Is it not so?"

Cardona shrugged his shoulders. "Indeed, yes... depending, of course, upon what the hire is."

Esteban said: "Would a great company such as yours miss a paltry two hundred silver dollars? Is this too much for a herd of cattle to be returned?"

"I don't think so," said Cardona. "I have no doubt that when the cattle are returned to da Silva they would willingly pay you the two hundred dollars."

Esteban rose. He stood looking sorrowfully at Cardona, his expression a mixture of misery and outraged dignity.

He said: "So you doubt my word. Señor Cardona. You tell me that the company will pay me this paltry sum when the cattle are returned. Perhaps you will be good enough to explain to me why I, Esteban, should trouble to interest himself in their business when they do not trust me. Perhaps you would care for me to wash my hands of this matter. Do you think that I came here to be insulted? People who know me will inform you that I have killed a man for less than this."

Cardona said: "Señor Esteban, I assure you that you mistake me. Never for one moment have I doubted your integrity. In order that you may know this; in order that you may understand my affection and esteem for you I tell you that out of my contingency fund I will pay you the two hundred dollars at once, trusting in your word."

Esteban said: "Your words give me great pleasure. How wonderful is friendship and understanding and trust. Give me the two hundred dollars and I will sign a receipt."

OUTSIDE, in the narrow alleyway that led from the main street

out towards the mesa, Esteban deposited the two hundred

dollars in the bags concealed beneath his saddle-flaps. He

tethered his pinto to an adjacent rail; turned back into

the main street; walked towards the white adobe one-storey

building that housed the chief of police.

Mendanda, chief of the Bana police, sat back in his chair, his feet on his desk. He was dressed in a dirty white shirt, with blue linen trousers, kept up by a piece of lariat rope round his waist; his sombrero was tilted over his eyes, a long cigarro hanging from his mouth.

He said: "God be with you, Esteban. It is a long time since I have seen you."

Esteban sat down on a stool in front of the desk. "I have been busy. Many things have kept me away, but when news comes to me that there is a possibility of trouble for my friend Mendanda then I come to you immediately. A you know, I am your friend."

Mendanda spat out of the window. "This is great news for me. Your smile is like sunshine to me. Take anything I have." He spat out of the window even more artistically than before. "Tell me, Esteban?"

Esteban said: "There are unkind people in Bana. Hear everything. It seems that by some means the corral gate at da Silva's were left open. A herd of cattle strayed. You have heard about this?"

Mendanda nodded. "Did they stray?" he asked. "I have been told that Olém Pedro and Quincho Anzanas were seen driving these cattle to Silver Valley—their usual place of hiding. I have had an information lodged before me. This morning I have arrested them. They are in the jail. When I accused them of this offence they said nothing." He shrugged his shoulders. "They did no even offer me any money not to arrest them, which I regard as being very suspicious."

Esteban said: "Mendanda, you will listen to me. You have been tricked. As you have just said, if Olé, Pedro and Quincho had been concerned in stealing these cattle they would have offered you money not to arrest them. The fact that they have not done so is, as you say, suspicious. This is a plot against you."

Mendanda cocked one black eyebrow. He said: "So... tell me the plot."

Esteban said: "Some fool must have left da Silva's corral gates open. The cattle strayed. News of this came to Olé. He knew perfectly well that if they stole the cattle suspicion would fall or them, so they did not steal the cattle."

Mendanda leaned forward. "I see. What did they do?"

Esteban said: "For once they decided to be honest citizens. They have driven the cattle into the police corral—the purpose for which you built it." He grinned wickedly at Mendanda. "Now they are going to bring an action against you for wrongful imprisonment."

Mendanda said: "It appears to me that there are no longer any saints. It appears to me that there is no longer any justice in the world that this thing should be done to me. I do not like this."

"Listen, my friend," said Esteban. "Why worry? It is so easy."

Mendanda threw a cigarro across the desk to Esteban, who caught it deftly. He said: "Tell me, Esteban."

Esteban said: "It is as simple as this. Da Silva deposited five hundred silver dollars with you—a reward for information about the cattle. Have you paid it out?"

Mendanda said: "Yes and no. Then are no secrets between you, my friend, and me, and you know that for a person of my integrity my pay is very small. I gave the informant two hundred and fifty dollars. I thought I was entitled to the balance."

Esteban nodded. "Listen to me, Mendanda. These people, Olé, Pedro and Quincho may make trouble for you, more especially as they will say it was your business to know whether the cattle had been driven into the police corral or not, even though it is such a long way away and you have not had time to go there. Do this: release them. Tell them that you wish to apologize to them; give then the two hundred and fifty dollars that you have kept from the reward. As you know. I am friendly with them. I will get fifty dollars back for you."

Mendanda shrugged his shoulders. He said: "Everybody in Bana makes money except myself. I get only fifty dollars."

Esteban said: "No, This is my plan. You will send one of your rurales to inform da Silva that his cattle are safe and you will inform him that because of my great regard for him I have volunteered to put his brand on the cattle before they leave the police corral, so that the insurance company will be satisfied."

He shrugged his shoulders gracefully. "I am not certain," he continued, "how many cattle are in the police corral but if, for the sake of argument, there are six hundred head it may be that I will only brand five hundred and three, because, after all, some of the cattle may have run wild when Olé, Pedro and Quincho were driving them to the police corral."

Mendanda said: "I see. So that leaves ninety-seven head in the police corral. What then?"

Esteban said: "I have a purchaser. You and I are good friends. Always there has been great honesty between us. When I have sold the ninety-seven head of cattle. I will divide the money with you, Mendanda, because you are my friend; because our interests are mutual."

Mendanda swung his feet off the desk. He opened a drawer; produced an iron ring with a dozen solid keys dangling therefrom. He threw the ring across the table to Esteban. He said: "Let them out. Tell them to come quietly to me and I will give them two hundred dollars, reserving only fifty for myself as commission."

Esteban picked up the keys. "So be it... Adios, Mendanda. When you die the world will be lonely for me."

Mendanda said: "Go in peace, my friend. When the door shuts behind you a cold wind enters my heart."

WHEN the hot afternoon sun disappeared in the west, Esteban

came down the Zusta trail. Pilar da Silva waited by the tree. She

came towards him.

She said: "How wonderful is life. My father is so pleased. This morning Olé, Pedro and Quincho Anzanas drove back the cattle. It seems they had strayed; had been driven into the police corral. He is a little annoyed because some are missing." She smiled at him archly. "He's pleased with you, too, for your kindness in putting his brand on the cattle before they left the corral. You must have worked hard."

Esteban shrugged his shoulders. "For your father I would do anything. Yesterday right through the broiling sun we four worked on the cattle. Nothing is too much for my Pilar." He put his arm about her. "I have news for you, my sweet. You are to be my wife."

She looked at him, her eyes glowing.

"Always, as you know," said Esteban, "the good will of your father has meant much to me. When he told me that some of his cattle were missing I was able to supply the deficiency at a very cheap price. Some unbranded cattle which I bought last month will be delivered to him tomorrow. Not only that," he said, "but listen to this, light of my soul. He has decided that it would be safer for me and his house that I should be his overseer. He has agreed that you shall be my wife. Now he knows that no longer will his cattle stray; that everything in his house will be at peace. Come, cara, let us go home."

They wandered down the pathway towards the main track, Esteban's pinto trailing behind them. After a little while Esteban threw away his long cigarro, began softly to sing an old Spanish love song.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.