RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

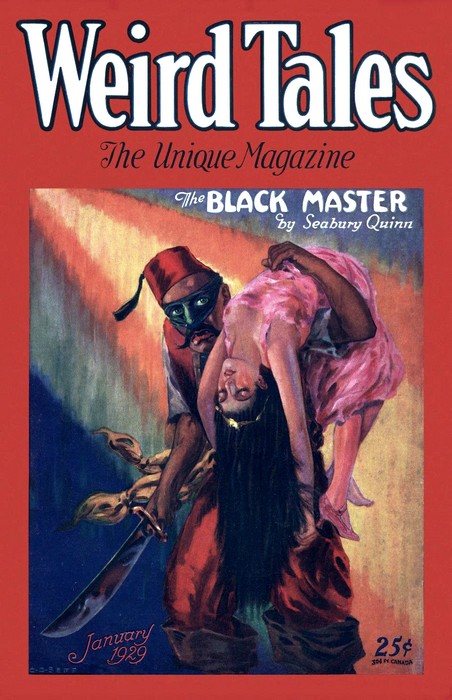

Weird Tales, January 1929, with "The Demon of Tlaxpam"

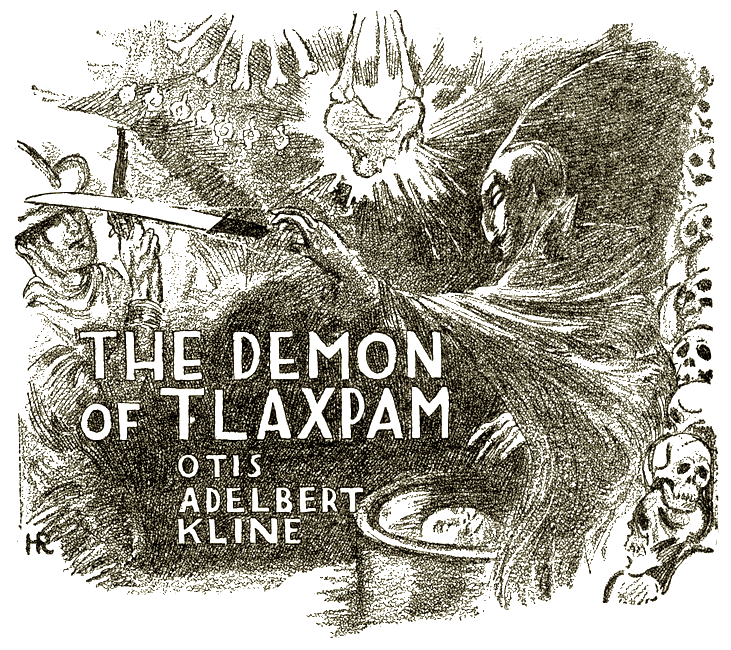

The manciac swung around and hurled the heavy

machete straight for the breast of the American.

Set in a remote Mexican village steeped in ancient lore and eerie rituals, this esoteric thriller tells the story of Bart Leslie, an American traveler who becomes entangled in a sinister mystery. The village harbors dark secrets, and Leslie soon finds himself confronting an enigmatic hermit who seems to hold the key to the village's secrets.... As Leslie delves deeper, he must face the titular demon—a manifestation of the village’s darkest fears.

"A TABLE for wan, señor? I 'ave ver' ex'lent place where the señor can see those dance girl do—"

"No."

Standing just within the doorway of Mexican Joe's notorious café, Bart Leslie scarcely noticed the diminutive head waiter, bowing solicitously before him. Leisurely, yet with piercing intentness, his eyes swept the smoke-clouded room, hovering for a moment at each table. The contortions of a dancing girl in flaming costume, slender hands on lissom hips, mantilla flying, tiny feet keeping time with the throbbing music of a brown-skinned orchestra, drew only a cursory glance from him.

"Per'aps the señor likes company. Yes? A table for two in a quiet corner, an' I send you wan ver' beautiful ——"

"No! Where's Mexican Joe?"

"Ees talk weeth some friend upstair. You weesh —?"

"Tell him Bart Leslie wants to see him, muy pronto! Sabe?"

"Si, señor. Gracias, señor."

Deftly catching the silver dollar which Leslie had flipped to him, he sped away among the tables and hastily climbed the stairway which led to a gallery over the orchestra platform and thence to the gaming-rooms above.

Leslie rolled a cigarette, lighted it, and waited. Presently he took a tightly wadded slip of yellow paper from his vest pocket, unfolded it, and scanned the contents. It was a Western Union telegram, and the date was the day previous:

MR. BART LESLIE

BONITA

DO ME THE HONOR TO DINE WITH ME AT MEXICAN JOE'S TOMORROW EVENING AT EIGHT. I HAVE AN IMPORTANT COMMUNICATION.

HERNANDEZ

Leslie folded and pocketed the missive once more, then glanced at his watch. It showed five minutes past 8. Time and place were correct, but where was Hernandez? And which Hernandez? He had known two —one a vaquero formerly employed on the Bar-X Ranch, the other an ex-captain of the Gila Men, a dread order of bandits, counterfeiters, kidnappers and murderers which he had helped to wipe out some time before.

His meditations were interrupted by the obsequious approach of the head waiter, followed by a short, wizened Mexican whose forehead was creased by a livid scar, and whom he instantly recognized as Mexican Joe.

The latter was effusive in his greeting.

"Ah, Señor Leslie, I am delight! I am honor, to 'ave the great Two-Gun Bart, the great Devil-Fighter, weeth us! Don Arturo ees wait for you een wan private alcove. Myself, I weel show you the way."

Considering that this same wily Mexican had once tried to drug him for a few paltry dollars, Leslie imagined that he was anything but delighted by his presence.

"All right, Joe, lead on," he said tersely. Then, loosening his two six-shooters in their holsters, both as a precaution and as a hint that he was prepared for treachery, Leslie followed the café proprietor between the tables and behind the orchestra platform to where a double row of curtained alcoves served as private dining-rooms for the more fastidious or secretive of the resort's patrons.

Pausing before one of these, he gently called:

"Don Arturo."

"Si?"

"Señor Leslie ees arrive."

"Bueno!"

The curtains parted and a tall, handsome Mexican, resplendent in purple velvet liberally trimmed with silver braid and adorned with buttons of the same metal, appeared in the opening and held out a slim hand, on one finger of which a dazzling ruby sparkled.

"Buenas noches, Señor Leslie," he greeted.

"May God give the same to you, Señor Capitán," replied Leslie, instantly recognizing Hernandez as a former officer of the dreaded Gilas.

After the handshake they entered the booth and were seated at opposite sides of the narrow table.

"No longer am I a capitan, amigo," said Hernandez, taking a frost-covered cocktail-shaker from the table and rattling its contents. "Only plain Don Arturo Hernandez, a civilian in the employ of my government."

"A decided improvement, I should say," replied Leslie, "and judging from that go-to-hell outfit you're wearing, you're making it pay."

Hernandez smiled.

"'Ee's not so bad," he replied, removing the top from the shaker. "I 'ave concoct wan dreenk which I 'ope you weel like. Those Manhattan an' Bronchitis cocktails I don' care for, an' I know you don' drink those tequila an' mescal, so I meex a dreenk where we meet on common ground."

He filled Leslie's glass, then his own.

"To unending friendship, amigo," he proposed.

Leslie bowed and drank the toast.

"A corking good Bacardi cocktail, if I'm a judge," he said. "Common ground is right! If your communication is as pleasing as your cocktail, we'll get along."

"It ees from my government," replied Hernandez, producing a large sealed envelope from his pocket, "an' it may be explain' quite briefly, though the details are here."

A waiter entered with the first course of the Mexican dinner accompanied by the usual plate of steaming tortillas. When he had departed Hernandez continued:

"My government was ver' mooch impress' by the way you clean out those Gila," he said, "an' such word has come to the capital of your prowess an' exploit along the border that they 'ave send me to request your co-operation in a matter weeth which they are unable to cope."

"Before you go any farther," said Leslie, "I may as well tell you that I am still in the United States Secret Service, and all my time and efforts belong to my government."

"That ees all arrange', amigo, in advance. My government 'as already approach and receive permission from yours to use your service eef we can make the satisfactory arrangement weeth you. It ees for you alone to say, now."

"I see. You believe in preparedness. Well, what's the racket?"

"It ees wan ver' dangerous beezness. Neat a town call' Tlaxpam many people die now, for two years —ver' sudden, ver' horrible death. They walk or ride along trail. All sudden, zeep! The head, she ees gone! Cut-off, sleeck like wan whistle! Horse come to town weeth headless body or weeth-out rider many time. Travelers find bloody corpse along the road weethout head. Others say they 'ave seen Satanás heemself lurking een the bushes. Wan peón heard a horrible laugh joost after a man was beheaded.

"Government send men to investigate. Zeep! They sometimes lose the head, too. They send the Rurales. Some Rurales also lose the head, but of thees murderer they can not find even wan track. Ees damn' bad beezness, I tal you."

"Sounds like a fairy-story to me."

"Maybe, but if you find thees fairy for my government they weel gladly pay you twenty thousand pesos and all expenses."

"Well. That sounds substantial enough. Let me see the papers."

Hernandez broke the seal of the envelope and handed him two documents. One was permission from the American officials for Leslie to spend sixty days in Mexico whenever he should elect to go. The other was from the Mexican government, commending his past unofficial services in ridding them of the Gilas, and offering him the reward mentioned by Hernandez. All expenses were to be paid regardless of whether or not he succeeded.

The Mexican watched him narrowly as he read and folded the last document.

"Ees all satisfy, amigo?" he asked.

"All Jake," Leslie replied.

"You weel go?"

"Of course."

"Cáspita! I tol' my government you're not afraid of those devil heemself. Put heem there!"

Silently the two men shook hands across the table.

"SON of wan gun! You tromp my ten-spot weeth a queen, eh? How you like that, an' that, an' that? Pay me."

"High, low, Jack. That's plenty." Bart Leslie fished in his pocket for a moment, then brought forth a handful of change, part of which he tossed on the table before Hernandez. Then he looked out the window of the private car furnished by the Mexican government to facilitate their journey to Tlaxpam. "Ought to be there soon, hadn't we?" he asked.

"Five minute more, maybe. Wan more hand?"

"No thanks. Have to be getting my things together."

Walking unsteadily to his sleeping-compartment, for the car lurched violently at every step, he closed and strapped his bag and handed it to the porter. Hernandez followed after gathering up the cards, and together they made their way to the platform.

"So this is Tlaxpam!"

Leslie looked out over a small group of sun-baked adobe buildings, then clutched the rail as the train halted with a jerk. He observed that the streets were deserted and remembered that it was the lazy hour of the siesta. Even the dogs slept.

"Ees the end of wan journey —the beginning of another. Follow me, amigo."

Hernandez stepped down from the platform and led the way around the corner of the station, the porter following with their bags. Here a driver slept peacefully behind the wheel of an ancient and badly battered touring-car.

Hernandez shook him awake.

"Alerta, hombre!" he roared. "Mil demonios! Did I hire you to sleep for me?"

The man awoke, then took their bags from the grinning porter.

"Pardon, Don Arturo. I did not hear the train arrive."

"You sleep like an os. Be off, then. You have your orders."

After considerable persuasion with crank and primer, the engine started noisily, and they rattled off down a narrow, dusty street. Presently they stopped before one of the larger adobe houses, the door of which was opened by a dark-skinned mozo as soon as they had stepped down from the tonneau.

After a bath, and a meal served by the same dusty servant, Leslie and Hernandez entered the patio to enjoy their cigars, and found comparative coolness on a bench beneath the spreading branches of a huge pecan tree.

"And now, señor," inquired Hernandez, politely, "how soon will you be willing to start on thees dangerous beezness?"

"Start? I have already started. What I want to do is to continue, and the sooner the better."

The Mexican puffed reflectively for a moment.

"You Americans are so eempetuous. Maybe you 'ave not notice something, eh? I breeng you here during the hour of the siesta. I speak not your name, but call you only 'amigo' een front of my mozos. For why? Thees fairy, as you call heem, may 'ave the spy any place. Een my very house! Eef he know you are here you are mark for death before you start. Sabe?"

"I see. You want me at least to get one chance at him before he bumps me off. But what makes you think he has spies?"

"Those other come. Zeep! They-lose the head too damn' queek. I don' like. They come weeth beeg noise and brag muy mucho. You come weethout noise and maybe do something. When they come everybody know. When you come, only I know. Ees not bad idea, eh?"

"Excellent logic, I should say. In any event it would be taking needless chances to herald my coming and my errand. But how and when do I start after your friend? 'Ogre' would perhaps be a better name."

"Tonight at midnight. Between now and that time you weel get all the rest and sleep you can. At 12 I weel 'ave a guide and horses to take you into the danger zone. Twelve picked men, armed to the teeth and carrying provisions and equipment, weel follow a half-mile behind you. They weel rush to your aid at the sound of a shot, and weel be subject to your command at all times. I 'ave arrange weeth a friend to quarter you een case you find it necessary to make camp. And now, amigo, weel you 'ave a leetle siesta before dinner?"

Bart Leslie tossed his cigar butt into the shrubbery, stretched his powerful arms, and grinned.

"That's the best thing you've said today," he replied.

FROM some near-by tower a bell tolled the hour of 11.

Leslie, who had retired immediately after dinner, was aroused from a sound slumber. He pushed back the covers and sat up in bed, trying to think what it was that had awakened him. Then the sound was repeated —a gentle tapping at his door.

Whipping one of his guns from the holster that swung from the belt on the chair beside him, he rose and tiptoed to the door.

"Que gente?" he asked. "Who is it?"

"Open, amigo," came back the soft reply. "Ees Hernandez."

"Ahead of your schedule, aren't you?" asked Leslie as he swung the door back.

To his surprise, there was no one in sight. About to step out into the dark hallway, he suddenly changed his mind as the sound of subdued breathing came to him from the right. Instinctively he knew there was someone crouching beside the door.

The warning of Hernandez flashed through his mind. Death, he was positive, lurked there in the corner of the hall —the mysterious and horrible end that had overtaken his predecessors.

He must act, that was sure. But how? To shoot through the wall would be to arouse the household —perhaps the community —and if the wall were brick-lined the bullet might be ineffective. A heavy mahogany chair standing beside the door gave him an idea. He knew that a scant two feet separated the edge of the doorway and the corner of the hall, hence he could calculate, with reasonable precision, the position of his concealed enemy.

First tucking his gun beneath his pajama belt, he quietly picked up the heavy chair by the back. Then, turning it so the front of the seat was forward, he swung it aloft and brought it down with crushing force at the point where he calculated the man's head would be.

As the chair struck a solid object a grunt of surprise and pain came from the corner, a heavy body pitched downward across the doorway, and a large machete clattered to the tile floor.

Before Leslie could find the switch to turn on his own light another flashed on in the hallway. There followed the patter of feet and a muttered exclamation in Spanish.

"Madre de Dios! They have keel the American already!"

"You mistake, Carlos. It is only a peón."

Leslie lowered his gun as he saw Hernandez and another Mexican, both in their sleeping-garments and carrying revolvers, rushing toward him.

"What ees happen, amigo?" the former asked him.

Leslie leaned nonchalantly on the back of the chair and mechanically reached toward his breast pocket for his makings, then remembered he was still attired in his pajamas, and grinned.

"That hombre knocked on my door and I thought it was you, so I opened it. When I found he was hiding in the corner I figured he wasn't friendly, so I quieted him with this chair."

"Ees plenty quiet, I tal you," said Hernandez, bending over the prostrate man, who was barefooted and wore the simple white cotton jacket and pantaloons of the same material common to Mexicans of the poorest class. "I theenk maybe you 'ave keel heem. Let us see." He turned him over on his back and a livid bruise on his forehead showed where the heavy chair had struck. Hernandez fingered this for a moment, then placed his ear to the fellow's heart. "Ees alive," he announced, "an' stunned." Turning to his companion, he said in Spanish. "Bind and gag him, Carlos. Perhaps we can make him talk when he revives."

The man called Carlos threw the would-be assassin over his shoulder as if he had been a sack of grain, and carried him off down the hallway.

"May as well dress now," said Leslie. "We can't get much sleep before midnight."

Hernandez shrugged.

"Joost as well," he replied. "Meet me downstairs when you are ready." Some time later Leslie, wearing full cowboy attire and two businesslike forty-fives, stepped into the spacious living-room. Finding it untenanted, he sat down on a divan and rolled a cigarette. A full twenty minutes elapsed before Hernandez entered.

"Ees no use," he said. "That damn' peón don't talk."

"Came to, did he?"

"Si, some time ago. We threaten weeth the hot iron —everytheeng. No use. Says he don't know about these head-stealers."

"What's his story?"

"Says he came only to rob the rich Americano."

"But he carried a machete."

"To be sure. Eef you 'ad step through that door —zeep! We find you weethout the head. Those damn' fairy are wise already, I bat you. Per'aps you better not leave tonight, amigo."

"Fast little workers, aren't they? Crave action. Well, let's give 'em some. Keep that hombre here and get him to talk if you can, but meanwhile let me take the trail. I'm not going to be seared off by a sneaking peón with a machete."

"But, señor, it ees more dangerous than ever, now. A little later we might ——"

"Nix on the mañana stuff. I'm going right now if you can get someone to guide me. Are your men afraid to go?"

Hernandez shrugged.

"My men are brave," he replied, "but it ees sometimes best to meex brains weeth bravery. Go then, eef you are determine', but remember, amigo, I warned you." He clapped his hands and the man Carlos appeared in the doorway. "Send José," he ordered, "and saddle the horses. José Gonzaga," he explained to Leslie, "weel guide you. Ees three-quarter Indian, and speaks no English, so you weel 'ave to converse in the Spanish."

A moment later a tall, swarthy fellow entered. Although he wore the dress of a Mexican vaquero, his high cheekbones, hawk nose and dark skin bespoke a predominance of Aztec blood. He was beardless, and three livid scars, two on the right cheek and one on the forehead, added to the ferocity of his countenance. For armament he carried a knife and revolver, both stuck in his sash, a carbine slung across his back, and two well-filled cartridge belts.

"Buenas noches, señores," he greeted with a flash of dazzling white teeth.

When both had made the customary polite reply. Hernandez said:

"Señor Leslie is determined to depart tonight, despite the fact that our plans have been discovered. You will therefore start at once and I will send the men after you as agreed." He turned to Leslie and extended his hand. "Adiós, amigo. May good fortune attend you."

Leslie shook the proffered hand.

"Gracias, señor," he replied. "I hope to play my cards better than I did on the train. Adiós."

JOSÉ led the way through the patio to the stables in the rear. Here Carlos held two rangy Mexican ponies, saddled and ready. To Leslie he handed a carbine like that carried by the guide, and a long sheath-knife.

Swinging the gun across his back and attaching the knife to his belt, Leslie mounted and rode forth, followed by José. The latter took the lead as they threaded the narrow streets, lighted only by the waning moon. Later, when they emerged into the open country, they rode side by side.

At first they crossed a waste of sand, gleaming a dull silver in the moonlight and dotted here and there with desert growths —giant cacti that reared their arm-like branches heavenward as if in a constant appeal for water, scrawny twisted mesquite in scattered clumps, and the more lowly prickly pears, their barbed and segmented branches twined and interlaced like the tentacles of cuttle-fish.

Later their trail led through a group of rocky hills, and thence along the bank of a narrow, tree-bordered stream, enclosed by towering canyon walls. When they entered the canyon, José paused.

"It is here, señor," he announced, "that the land of the demons begins. On this spot, just three nights ago, a headless body was found."

"And no trace of the murderer was discovered?"

"None. A riderless horse, blood-splattered and weary, wandered into Tlaxpam the next morning, and we knew what we would find, even before I started here with two companions. There was but one fresh trail —that of the horse that had borne the victim."

"Is the trail so little used?"

"Yes, señor, since the mysterious murders commenced. Formerly it was quite popular with those entering and leaving Tlaxpam from the north. Now it is shunned as a plague spot, although a detour of five miles is necessary to avoid this pass. Only strangers, travelers unacquainted with its bloody history, use it now and these seldom live to boast of it.

Many of these have been warned, have laughed at the warning, and have paid for their foolhardiness with their heads. A few who have escaped swear that they heard the whistling of the wings of Satan, who swooped down at them without warning, and whose frightful attack they avoided only by the utmost quickness and hassle in riding away. Others claim to have heard his horrible, blood-curdling laugh, and still others to have seen him lurking in the undergrowth."

"There are many people with powerful imaginations," replied Leslie. "How long is this pass?"

"Nearly a mile. From now on we are in grave danger. Shall we proceed at once, or wait until daylight?"

"Let us go on."

Scarcely had these words passed the lips of the American than both men heard a noise in the pass ahead of them. Mingled with the distant clatter of horses' hoofs they heard someone singing or yelling —perhaps both —and the sounds were punctuated with the reports of a gun.

"Some drunken fool," said José. "Ah! The sounds have stopped. Perhaps the demons have killed him."

The sounds of voice and gun had died, but the patter of hoofs was still audible. There sounded, however, another voice, high-pitched, cackling, as if in demoniac laughter.

"Santo Dios! The laugh of Satanás!" cried José.

"Pull over to that side of the road, quick!" ordered Leslie. "I'll wait on this side."

They had not long to wait. The hoof-beats slowed down from a gallop to a singlefoot. A horse appeared, rounding a bend in the canyon wall, but the animal was without a rider.

"Demonios! It has happened!" exclaimed Jose, crossing himself devoutly. "Maria Madre preserve us!"

Leslie caught the bridle of the riderless horse and, producing his flashlight, examined the saddle and the back of the beast. Both were spattered with blood.

"The body will be lying near the point where the singing ceased," said José. "Of that I am certain."

Again came the thunder of hoof-beats, this time from behind them.

"Our men are coming," José said. "They heard the shots and think we need help."

"Here, take the reins and bring the men forward when they arrive," ordered Leslie. "I'm going to look for the body and the murderer."

He spurred his pony forward. A short distance beyond the first bend he saw a ghastly thing in the moonlight —a headless body lying by the roadside. Dismounting, he brought his flashlight into play. There were no tracks of human being or animal near the body, other than those made by himself, his horse, and the horse of the victim. He walked ahead for fifty feet, then discovered a revolver in the dust of the road. Five of the six chambers had been discharged. Pocketing this, he again made his way forward. A walk of a quarter of a mile revealed no tracks other than those made by the victim's horse, and he knew the tragedy had not occurred that far back. Puzzled, he mounted and rode back to where José and the twelve men sent by Hernandez waited beside the body. The guide had dismounted and was standing beside the corpse.

"You found tracks of the murderer, señor?" he asked.

"Not a track."

"That was to be expected. I have found a paper on the body of this young fool, explaining why he rode through the pass. It seems he made a drunken wager with another young blood that he could come through unscathed. The paper is the other man's guarantee of the payment of a hundred pesos by this fellow's bank in case his headless body is found. What is to be done?"

"From what town did this man ride?"

"Rosario."

"Tie the body on the horse and let two of our men take it back to his relatives. Put the paper in the pocket where you found it."

When the two riders and the horse with its ghastly burden had been dispatched in accordance with his orders, Leslie posted his men by twos at intervals of a thousand feet along the canyon. Then, accompanied by José, he patrolled the road for the remainder of the night.

The first faint streaks of dawn found Leslie and his companion near the center of the danger zone. The former reined his horse to a halt as the odor of burning wood came to his nostrils.

"Someone is making camp near here," he said. "I smell smoke."

José smiled.

"It is only Tio Luis, the Anciano," he replied, "preparing his breakfast."

"Uncle Louis, the Old One? Who is he?"

"The Anciano is a very venerable hermit who braves the dangers of this pass to remain with the holy shrine of San Antonio, which he has attended since the death of good Father Salvador some years ago. Although he is but a lay brother, he is a most holy man, revered by all who know him, and a very good friend of Señor Hernandez. He has agreed to quarter our men if we find it necessary to remain."

"A shrine of St. Anthony here? But why has it not been moved?"

"Because it rests on a holy spot, venerated for more than two centuries. From a crevice in the hillside, just beside the niche containing the image of the saint, there flows a spring. This spring empties into a shallow pool where the sick have come to bathe for many generations and where countless miracles of healing have occurred. Whereas pilgrims often came alone in former years and at all hours, they now come only in the middle of the day and in considerable numbers for mutual protection on account of the murderous fiends who surround this place. Did not Señor Hernandez mention the Anciano?"

"He only said quarters had been provided for the men. How do we reach this place?"

"We have only to ride up the ravine at your left, down which this small stream trickles. It is the overflow from the sacred pool."

LESLIE assembled his men and led them up the steep path in the winding ravine which had been pointed out by José. Presently he emerged on a small plot of more even ground and beheld the home of the Anciano. It was a small abode hut, built against the steep hillside. On the left of the hut was a niche containing a life-size image of St. Anthony, and just in front of the image was the pool described by his guide, which was fed by a spring that bubbled from the rock. From a battered and rusty stovepipe that protruded from the side of the hut, there issued the wood smoke which was being wafted down the ravine, and which had drawn Leslie's attention to the place.

At the right of the enclosure was a long, low shed, open on one side and built from wide, rough, unpainted boards. This was evidently intended to quarter the horses of pilgrims as well as the pilgrims themselves, for rings were fastened at frequent intervals along the back wall.

The men tethered their horses and busied themselves with opening packs, preparing breakfast, and pitching tents, while Leslie and José went up to the hut of the anchorite. It was evident that he had heard their arrival, for a bent figure, attired in a ragged robe of rusty brown and leaning on a staff, emerged from the doorway and hobbled forward to meet them. As he drew near, Leslie saw a face that was seamed, wrinkled and emaciated above an unkempt gray beard.

The hermit paused before them and leaned on his staff.

"God bless you, my sons," he mumbled, with the peculiar sibilant enunciation that invariably denotes the paucity or absence of teeth. "You have come from my friend, Señor Hernandez, I presume. And you have passed the demons unscathed. Deo gracias."

"Unscathed thus far, Tio Luis," replied José. "This is Señor Leslie, the great Devil-Fighter, who has come to rid us of the demons that haunt this vicinity."

"Bueno! We have need of him, and our prayers for his safety and success will go with him on his dangerous mission. But come within and join me at breakfast if you can do with my humble fare."

They accompanied the aged hermit to the door of the hut, where he politely stood aside and bade them enter.

"All that you see is yours, my sons," he said as he followed them into the small front room. "Excuse me while I go into the kitchen to see about breakfast."

He hobbled through a curtained doorway into the rear room, and Leslie heard him puttering about to the accompanying clatter of pans and crockery.

José unslung his carbine, stood it in a corner, and flung himself into one of the chairs beside the bare table that stood in the center of the room.

"Huy, but I am tired," he grunted. "It has been a strenuous night, señor."

Leslie politely agreed with him, disposed of his own carbine, and took a chair on the other side of the table. While he waited for the puttering anchorite he glanced around the room. The furnishings were meager enough to suit the taste of the most humble of lay brothers; a low cot covered by a frowsy blanket, four crude chairs, and the table at which they sat, its bare top stained with food and beverages. Beneath the single window there stood a small, crudely constructed pulpit on which lay a book, evidently a missal. Both pulpit and book were covered with much dust, evidence that they had known little if any use since the passing of Father Salvador. The plastered walls were cracked, grimy, and festooned with cobwebs.

Presently the Anciano limped through the curtained doorway. Again apologizing for the meanness of the fare, he set before them some boiled rice, a huge chunk of honeycomb, and hot chocolate.

After consulting with José and the anchorite, Leslie decided to post two guards at each end of the pass for the morning, do a little exploring on his own account, and permit the other men to rest, relieving the guards at noon.

Accordingly, he set out after breakfast, resolved to make a minute examination of the scene of the tragedy enacted the night before, hoping that the morning sunlight might reveal some clue overlooked in his search by flashlight.

Arriving at the place where the foolhardy rider had been beheaded, he dismounted and scanned every foot of the ground in the vicinity. The road, at that point, was less than ten feet in width. On one side the cliff rose almost perpendicularly to a height of nearly twenty-five feet, and appeared unscalable. On the other, the stony ground sloped sharply to the water's edge. Some thirty feet from the point where the blood spots began, a clump of stunted willows had found foothold in the rocky bank. Leslie peered into these with a view to ascertaining whether or not they had been used for purposes of ambush, then uttered a cry of surprise at sight of a bloodstained object hanging among them. He drew it forth and recognized it instantly as the outer edge of a broad-brimmed sombrero. It appeared to have been cut from the hat by a very keen instrument, not in the form of a circle or oval, but more like an irregular hexagon, no two lines being equal but all lines straight, or nearly so. He noticed, also, that it was creased at each point where two straight cuts joined. An examination of the bushes revealed the fact that they had not been used as a hiding-place by a human being.

Puzzled, Leslie hung the blood-caked relic over his saddle-horn, mounted, and rode back to camp.

His men, with the exception of one who had been left on guard by José, were sleeping beneath the tents, the walls of which had been raised to admit the breeze. The guard took charge of his horse and looked curiously at the bloody hat-brim which Leslie removed from the saddle-horn.

He started for the hut of the hermit, intending to show his find to that individual, then paused as the sudden clatter of hoof-beats came from behind him.

Turning, he beheld one of his men emerging from the ravine. The fellow dismounted and ran to where he was standing, fear and horror written on his bronzed features. So great was his agitation that, although his lips worked spasmodically, he was unable to speak.

"Well, what is it?" snapped Leslie. "Have you lost your voice?"

The man crossed himself and muttered beneath his breath.

"Maria Madre preserve us!" he gasped. "We are all doomed men."

"But how? Speak to the point."

"The demons! They kill in broad daylight now!"

"Where? Who?"

"We were standing guard at the north end of the pass, Miguel and I. They have beheaded Miguel!"

"What did they look like?"

"I did not see them, señor."

"What? Your comrade slain before your eyes and you could not see the murderers?"

"Not before my eyes, señor. I —that is ——"

"You were sleeping, I suppose, on duty."

The fellow hung his head.

"We were very tired, Miguel and I, after the night's vigil. Things were so peaceful that we decided there could be no harm in our snatching a little sleep, one at a time. I stood guard for two hours while Miguel slept. Then he mounted guard, but it seemed I had scarcely closed my eyes before I heard him utter a choking cry. I caught up my carbine and leaped instantly to my feet. Before my eyes the headless body of my comrade slipped from his saddle, and at the same moment I heard the whir of wings above my head! Although I looked upward instantly, I saw nothing!"

"This whir of wings. Was it loud like the roar of an airplane?"

"No, señor. It had a much quieter tone, like the whistle of a large bird's pinions."

"What has happened, my sons?"

Wheeling, Leslie saw the Anciano, who had hobbled up unnoticed, behind him.

LESLIE explained the situation to the hermit and showed him the hat-brim he had found.

"Lend us the wisdom of your years, Tio Luis", he requested. "This is the most singular as well as the most hellish thing I have ever encountered. What do you make of it?"

The old man turned the gruesome relic in his bony hands, squinting at it with watery eyes.

"A man beheaded, the whir of wings —and this." He shook his head, handed the thing back to Leslie, and crossed himself. "I fear you are playing with fire that will destroy you, my sons. We have a saying: 'He must have iron fingers who would flay the devil.'"

"We also have a saying that is apt, Tio Luis," Leslie replied. "'Give the devil rope enough and he'll hang himself.'" He turned to the guard. "Saddle my horse, Pedro, and arouse José. We'll see if the devil has left any more souvenirs."

Once more the anchorite shook his grizzled head.

"'He was slain who had warning, not he who took it,'" he quoted. "You have my sympathy, my son —that and my prayers."

"The former is premature, but for the latter I thank you," replied Leslie. "Ready, Pedro?"

"Si, señor. José will be out in a moment. He is pulling on his boots."

José emerged from the tent as Leslie started toward the horses. Together, they mounted and rode down the ravine.

They covered the half-mile to the north end of the canyon at a brisk gallop. The body of the slain man lay sprawled in the middle of the road, and his patient horse stood near by, apparently not greatly frightened by the diabolical presence which had given Pedro so much alarm.

Dismounting, both men looked carefully for tracks of the slayer, but their search was as fruitless as before. Nor was there a cut hat-brim, such as Leslie had found on the scene of the last tragedy.

Compelled at last to give up their hopeless search, they tied the body of Miguel across his saddle and took it back to camp. Leslie directed that the corpse be rolled in an extra tent-fly and sent to Tlaxpam with one of the men. Then he detailed two guards for the north end of the pass and two to relieve those at the south end, warning them to take heed from the death of Miguel and do no sleeping on duty. These matters attended to, he instructed the camp guard to call him before sundown, and retired to his tent for a much-needed rest.

It seemed to Leslie that he had not slept more than fifteen minutes when he was aroused by a tug at his blanket. Opening his eyes, he saw José standing over him.

"The sun nears the horizon, señor," he said, "and the Anciano has bidden us to sup with him. Some pilgrims visited the shrine this afternoon and left gifts for the holy man. Among them were a pullet and a bottle of wine he desires to share with us."

"Pilgrims? Who were they?"

"Only two peons with their wives. They came here on donkeys from a hacienda near Tlaxpam, and departed after they had bathed in the sacred pool and deposited their gifts."

"I see. Tell the Anciano we accept with gratitude. A pullet and a bottle of wine will be preferable to tasajo and frijoles. I'll be along in a few minutes."

José departed, and Leslie pulled on his boots. Then he buckled his two gun-belts about him and stepped out of the tent, intending to wash for dinner at the spring. His men were squatting or lying around their cooking-fires, preparing their evening meal.

As he rounded the last of the tents he saw a man disrobing beside the sacred pool. On closer approach he recognized Pedro.

"What's the matter? Sick?" he inquired.

"A bath in the pool at sunset is said to cure boils," replied the Mexican, stripping off his shirt. "I have two on my back, señor."

"At sunset? I didn't know the time made any difference."

"Oh, but it does, señor. The Anciano told me so himself."

Walking past the image of St. Anthony, Leslie laved his face and hands in the bubbling spring. Then, much refreshed, he started for the hermit's hut. The sun was sinking, and he heard the splashing of Pedro as the lad entered the pool.

Rounding the corner of the hut, Leslie came upon José seated on the doorstep smoking a husk cigarette. In the kitchen he heard the anchorite bustling about among his pots and pans. The table was set and graced by a wide, wicker-covered bottle with a long neck.

"How is your appetite, José?" he asked.

"Like that of a wolf, señor. And yours?"

"Like that of a pack of wolves. I'm accustomed to eating lunch, but I've been too busy today."

At the sound of their voices the hermit limped out from the kitchen.

"Come in, my sons," he said. "Be seated and sample this wine with me while the pullet reaches the right degree of tenderness."

They obeyed his invitation with alacrity.

"This is really an imposition, Tio Luis," said Leslie as the old man filled their glasses, "but I couldn't resist. I promise you a dozen pullets and a dozen bottles to replace these when I get back to Tlaxpam."

"I, also," cried José, eagerly reaching for his glass. "We are eternally indebted to you. I propose the health of our host, señor."

The hermit bowed, smiled, sipped his wine, and rose. "I must look to our food," he said.

The two men sipped their wine and discussed the events of the day. Presently José emptied his glass and refilled it.

Then the anchorite entered again. In one hand he bore a large pot from which savory odors exuded. In the other he carried a deep plate over which a bowl had been inverted. Placing pot and plate on the table, he lifted the bowl.

"Chicken and chile!" cried José. "Food for a king."

"And tortillas!" exclaimed Leslie. "Did you bake them yourself?"

His words were followed by a shout from outside —then an excited babel of voices.

Leslie put down his glass and rushed out the door. He saw a man standing beside the sacred pool. The others, aroused from their places beside the campfires, were running toward their companion. He joined the rush to the pool and saw, in a moment, the cause of the commotion. A half-clothed, headless body with arms outstretched lay on the very rim of the pool.

"It is Pedro!" a man cried. "The demons have slain Pedro!"

"They will slay us all if we remain," said another. "I'm going back to Tlaxpam."

"And I."

"And I."

José came running.

"What has happened, señor?" he asked, his tongue a bit thickened by wine.

"We've lost another man." Leslie produced his flashlight and snapped it on. "See if you can quiet these sniveling cowards while I have a look around."

WHILE José, rendered eloquent and perhaps more fearless by the wine he had consumed, sought to quiet the fears of his comrades, Leslie made a thorough examination of the body. He judged from its position that Pedro had been seated on the rim of the pool with his back to the image, dressing, when the crime occurred. The other men, occupied with their evening meal, would not have seen the attack because of the tents intervening between the cooking-fires and the pool.

Using the jutting rocks for feet and hands, he next climbed the steep hillside at the left of the image, circled the point over the niche, and descended on the right side, searching every inch of the way with his flashlight. As there were no tracks other than those he had made himself, he concluded that the attack had not come from above. It was useless to look for tracks on the hard-packed ground around the pool, and there seemed to be no other clues.

His men, he noticed, were gathered in a small group around the loquacious José, and he was about to snap off his flashlight and go to the guide's assistance when the white circle fell on something that gave him pause. It was a large drop of blood on the stone floor of the niche, and directly in front of the image. With a low cry of surprise he bent over to examine it, then leaped up and whirled about, gun in hand, at the sound of a footfall behind him. He returned the weapon to its holster with a nervous laugh as he saw the Anciano standing there, peering at him with his little watery eyes.

"Sony, Tio Luis," he apologized, "but you gave me a deuce of a start."

"Do not mention it, my son," replied the hermit. "I should have announced my coming at a time like this. So the demons have profaned the sacred pool! Now, indeed, will the wrath of God smite them. You have found a clue?"

"Only a drop of the blood on the floor of the niche. It has some significance, of course —but what? How do you suppose this blood was dropped clear over here, a full ten feet from the body? And there are no blood-spots between, other than those around the body itself."

"It is as mysterious as all else that has happened. We have a saying: 'The devil lurks behind the cross,' and if this be true he would not hesitate to conceal himself in a shrine of St. Anthony."

"That explanation may suffice for you, but it does not satisfy me," replied Leslie. Then, noticing that some of his men were saddling their horses, he hurried to the assistance of José, whose alcoholic eloquence had apparently not been sufficient to deter them from their avowed purpose of returning to Tlaxpam.

"Get down, hombre!" he roared, addressing a man who had already mounted. The fellow hesitated, then did as he was bidden. He swung on the others. "What does this mean? Are you women in the uniforms of fighters?"

"We can not fight the devil," one man replied.

"We shall only lose our lives and accomplish nothing by remaining," said another. "Come with us, señor."

Leslie laughed.

"Go, then, cowards," he retorted. "Go back to Don Arturo and tell him you are afraid —that you are too white-livered to remain and avenge the death of your comrades. I'll stay and fight these murderers alone."

"Not alone, señor," said José. "I remain with you." He appealed again to the men. "The great Devil-Fighter stays," he said, "to deal death to those who have slain our comrades. Boon companions we have been for many years, we and those of us who have died for our cause. The Devil-Fighter, whom we have only known since yesterday —who has only known Pedro and Miguel a few hours —remains to avenge them. Is there one among us who can do less?"

"He is right," said the man who had just dismounted. "I remain."

"My duty is plain," said another. "I remain also."

"And I."

"And I."

"Viva Leslie! Hurrah for the great Devil-Fighter!"

Thus the mutiny was quelled and order restored.

In a trice, José had set them at various tasks, knowing full well that if their hands were occupied they would have less time for fearful speculations. The body of Pedro was wrapped and swung from the rafters of the shed. The watch-fires were replenished so that most of the camp was illuminated, and men were sent to relieve the guards at the ends of the canyon.

In order to hearten his men further, Leslie decided to ride down with the two who were to take the post nearest Tlaxpam. Nothing untoward occurring after an hour's vigil with these two, he enjoined them to be on their guard and rode away to see how the two at the other end of the canyon were getting along.

He had passed the camp and was rounding the next curve at a slow canter, wrapped in meditation as he pondered the terrible and amazing events of the last twenty-four hours, when with startling suddenness there came a sound resembling the whistle of huge pinions, directly above his head.

There was no time to think —yet he acted, by instinct rather than by reason. With catlike quickness he hurled himself sideways and hung, Indian fashion, supported by one stirrup and the neck of the pony. Something struck heavily on the saddle and he heard a sharp metallic click. Then the frightened animal bounded forward so suddenly that he nearly lost his hold. Deft horseman that Leslie was, he managed to regain his seat before much ground had been covered, but nearly lost his balance in doing so, because when he reached for the saddle-horn he grasped only empty air.

Pulling the pony to a halt he dismounted, unslung his carbine, and waited for a new attack. Five minutes elapsed —ten —fifteen, yet he saw nothing save the rugged canyon bathed in the moonlight, and heard only the chirruping serenade of insects and the occasional call of a night bird.

Holding the carbine in his left hand, he felt the front of the saddle with his right. The horn, he discovered, had been sheared away smoothly and completely. Thus, he was certain, would his head have been sheared from his shoulders had he kept his seat a fraction of a second longer when that awful, death-dealing thing had hurtled down at him from a clear sky.

And the thing itself. What was it? Something conceived by man, he felt sure —for Leslie was not superstitious —yet designed with such diabolical cleverness as to kill with almost superhuman accuracy and leave no clue that would hint at its I nature or modus operandi.

Convinced, at length, that he could not further his cause by remaining longer, Leslie removed his broad Stetson and fastened it to the saddlering with the chin-strap. Then he mounted with a better view of the air above his head and rode, carbine in hand, to where the two guards were posted. Finding that they had nothing to report, he left them with a warning to maintain the utmost vigilance, and rode slowly back toward the camp. While he rode, albeit he kept a weather eye for danger, he was thinking, and to such purpose that when he reached camp a new plan had completely formed in his mind. He greeted José with a disconcerting smile as that worthy came out to meet him.

"THE señor is amused?" José answered the smile of Leslie with a flash of his white teeth. "Perhaps he has discovered something."

"Nothing new, José," Leslie replied. "Just thought of a new scheme to work on this so-called 'devil'."

"And the scheme?"

"I'll show you in a minute. Go and ask Tio Luis if we may tear three or four boards off his horse-shed."

"Tio Luis retired for the night shortly after you left. Should we disturb him for such a trifle?"

"No, let him sleep, but bring four boards into my tent, a riata and a couple of good sharp machetes. Don't make any more noise than necessary, and say nothing about this to the others."

"Si señor."

As soon as José departed to do his bidding, Leslie went behind the tents and pulled a huge armful of grass. With this he entered the rear of his own tent, deposited it on the floor, and lighted his lantern. Then he opened one of his saddle-bags and took therefrom a complete suit of cowboy attire.

Jose returned in a trice with the boards and the machetes.

"Now bring me a saddle," Leslie ordered.

When José got back with the saddle he found the American industriously hewing one of the broad boards with a machete. The wood was partly softened by dry rot, though firm enough not to crumble, and was consequently easily shaped with the keen blade.

Leslie finished this board, which was about six feet in length, and handed it to José.

"Cut me another the same shape," he said.

José worked swiftly, but stole a curious glance at Leslie from time to time as the latter cut one of the remaining boards into four pieces, the other into two, and then proceeded to cut holes and notches in them.

The boards shaped, Leslie cut the riata, a piece at a time, and began lashing the boards together, using the notches and holes for the purpose. When José saw a figure resembling the frame of a scarecrow beginning to take shape he grinned broadly.

"Por Dios!" he cried. "Do you expect to fool the devil with so simple a thing?"

"Wait until it's finished," Leslie answered, drawing the trousers and boots over the frame and stuffing them with grass. "Bring a horse around behind my tent while I finish this work of art."

His own effigy completed to his satisfaction, Leslie clapped his Stetson over the head and lashed the thing to the saddle with what was left of the riata. Then he lifted the rear tent-flap and passed it through to the waiting José. Together they placed the dummy on the back of the surprised and annoyed pony, and stood back to view their handiwork.

"Viva!" exclaimed José. "Your double sits the horse, señor."

"Now for the rest of my plan," said Leslie. "I want you to saddle another horse and lead this one, giving it about twenty feet of rope. Ride very slowly up and down the canyon until the attack occurs. If we may judge by our previous experience it is almost sure to come. The enemy will attack the rear man for two reasons. One is that an attack on the man in front could be seen and perhaps frustrated by the man in the rear, and the other is that the thing looks like me in the moonlight and I have reason to believe my head would be preferred as a souvenir above all others in this company.

"While you are walking your horses on the trail below I'll follow at a distance of about a hundred yards on the cliff above. I have a pair of moccasins here that will eliminate any clatter I might make with boots and spurs, and will thus have a chance to view the attack from above while you look on from below."

"Cáspita! Now we will get this devil, for sure."

"I "hope so. Go and saddle up while I put on my moccasins. If we have any traitors in camp they will see us ride away together. If not, there will be no harm in temporarily deceiving them. I'll throw the end of the lead rope to you from behind the tent, when you're ready to start. Then I can hike over to the top of the cliff and wait for you."

As José, some moments later, rode down the arroyo apparently followed by the American, Leslie stood and viewed his handiwork with pardonable pride for a moment, then scurried up to the top of the cliff and waited for the guide to appear below him.

It was not long before what looked for all the world like two horsemen riding in single file emerged from the arroyo and started toward Tlaxpam at a leisurely pace. Following his preconceived plan, Leslie kept about three hundred feet behind them on the cliff top, his moccasined feet making no sound, his carbine held ready for action.

A full quarter of a mile had been covered when Leslie's quick eye caught the movement of a shadowy form near a clump, of brush at his right. It disappeared in the bushes almost instantly, and he paused, breathlessly awaiting its reappearance. The view had been so indistinct that he was not sure whether it had been a man or an animal.

After several minutes of waiting, he grew impatient and had just decided to explore the bushes where the apparition had dropped out of sight, when he saw it again, this time fully three hundred yards away and just on the brink of the cliff. It was undeniably a man, though grotesquely shaped, a man with what looked like a huge hump on his back. As he looked, he realized that the prowler was directly above the point where José and his own effigy would be, the guide having made considerable progress while he had been waiting for the reappearance of the figure.

Dismayed at this unforeseen circumstance that had caused him to lag so far behind the guide, Leslie rushed forward. As he did so, he was amazed to see the hump suddenly detach itself from the back of the man —no longer a hump, but something about the size of a peck measure. It was raised aloft, then hurled downward over the side of the cliff. Leslie halted and brought his carbine to his shoulder, but at this moment his quarry suddenly dropped from sight.

Cursing his own slowness, he again hurried forward, stepped into an unseen crevice, and fell sprawling, cutting his hands painfully on the sharp stones. As if in mirth at his discomfiture there came to him the raucous echoes of hideous, demoniac laughter.

He scrambled to his feet, caught a glimpse of the humpbacked figure again, and fired. Simultaneously with the crack of his rifle the figure dropped out of sight. Again he ran forward, his rifle held in readiness, straining his eyes in all directions for another sight of his quarry. He had almost come upon the spot where he judged the marauder had stood, when he caught the movement of something in the shrubbery, this time a full hundred feet back from the cliff. Again he fired and rushed forward, convinced that his bullet had found its mark. It seemed, however, that he was doomed to disappointment, for a thorough search of the shrubbery in and around the spot revealed nothing.

Returning to the brink of the cliff he took the precaution to call out before showing himself.

"José."

"Que gente?"

"I am Leslie. Do not shoot."

"Very well, señor."

Looking over the cliff, Leslie saw that his effigy had been decapitated, even as he had expected. It was well, too, that he had had the forethought to call out, as José had dismounted and was standing behind his pony, his carbine pointing across the saddle. "Did you see it, José?" he asked. "No, señor, but I heard it. Praise God it struck as you expected."

"So I see," replied Leslie, regarding the headless effigy, "but unfortunately I wasn't on the job to strike as I expected. I may as well ride back to camp now and think up a new scheme. This one won't work again. I'll keep to the cliff above you in case of another attack."

"Very well, señor."

BACK at camp, Leslie's men greeted him with a flood of questions, for they had heard the sound of his carbine. The appearance of José leading the horse which bore the headless effigy increased the amazement of the Mexicans, and Leslie left the task of explaining to the guide while he sat down on his cot to smoke a cigarette and think out the situation. Hearing laughter from the men outside as José told of the ruse, he decided that the salutary effect on them had been worth the effort, even though he had not succeeded in his purpose.

His cigarette finished, he ground it into the dirt with his heel and paced back and forth in the tent. As he was preoccupied with his efforts to think out a new plan of campaign, it was some time before he noticed that it was growing lighter outside. He stepped out, and found that most of the men had rolled themselves in their blankets to rest after the night's vigil. Two stood guard, however, and José squatted beside a smoldering fire, heating a pot of chocolate.

He was about to join the latter beside the fire when he noticed smoke issuing from the stovepipe that protruded from the side of the Anciano's hut. Evidently the hermit was an early riser. Perhaps, thought Leslie, he could offer a suggestion for the next move in the campaign. At any rate, he should be told about the boards and the effigy.

Going to the hut, Leslie rapped smartly on the door. There was no response. He rapped again. Still no response. Puzzled, he swung it open and entered. Seeing no one, he walked into the kitchen. There was nobody in sight, and no sign of a fire in the stove. Yet he had, just a moment before, seen smoke issuing from the stovepipe.

Confronted with this paradoxical, situation, he stepped forward and felt the pipe. It was quite warm —almost hot. He looked out the small window and saw that smoke was billowing from the pipe even more thickly than before. This led him to make an examination of the stove. One end, he now noticed, abutted against the adobe wall at the rear of the hut. He raised a lid, and a cloud of smoke whirled up into his face. Reaching inside the stove, he explored with his hand, and found that it was coming through a pipe which connected the end of the stove with the adobe wall.

If this told him anything, it was that someone had built a fire on the other side of the wall. But how had he got there? The hillside had been partly dug away when the hut was built. Evidently the digging had been deeper than appeared on the surface. He made a quick examination of the rear wall. All appeared to be solid adobe with the exception of a row of shelves containing canned goods, cooking-utensils, and other things, which occupied one side. These were of wood, apparently built against the adobe, yet they were his only hope. He pulled on the side nearest him, but it was apparently quite firm. Pushing brought the same result. Then he tried pulling the other side, and his heart gave a sudden jump as it gave and swung toward him. The shelving, he now saw, was nailed to a heavy oaken door with concealed hinges, the front of which was plastered with adobe.

A dark passageway yawned before him. He drew a revolver, stepped in, and pulled the door shut after him.

Pausing for a moment to accustom his eyes to the semi-darkness, he noticed that what light there was came to him from around a curve in the passageway. It was of reddish hue, and flickered weirdly in the gloom. As he advanced he noticed that the floor slanted abruptly downward.

He rounded the curve in the passageway, his moccasined feet making no sound, then came to a sudden halt; for not ten feet ahead was a sight that made his flesh creep —a grinning human skull, hovering with no apparent support, in midair. The fleshless features seemed to quiver with some ghoulish emotion, the eyeless sockets to sparkle with malignant intensity.

Conquering his repugnance, Leslie again advanced, and discovered that the skull was hung on a thin, black, hence invisible, wire just at the entrance of a square room. The apparent motion of the bony features was caused by the flickering light of a fire that crackled in a fireplace cut into one wall, and over which a huge black cauldron bubbled.

Stepping past the skull, Leslie was confronted by a charnel array that rivaled, if it did not exactly resemble, the most ghastly corners of the Catacombs. He was surrounded by skulls, some dangling from the ceiling rafters on wires of various lengths, some grinning down at him from the wall where they were arranged in divers geometric patterns, and the rest piled in a grim funebral pyramid in the center of the floor.

Feeling sure there was someone near by, Leslie looked carefully about him. There were two entrances to the chamber, the one by which he had come, and another in the opposite side of the room. After investigating the second opening, which led into a dark runway, he walked to the fireplace, curious to know what was being cooked in the kettle.

Peering over, he saw a seething mass of liquid with a dark spot in the center. Then the dark spot moved —it was black hair —and the ghastly dead face of Pedro, turning with the movement of the water, looked up at him. Beneath it, another head was slowly turning toward him —the head of Miguel. He drew back, sickened and horrified, then paused, listening intently. Distinctly, he heard the sound of footsteps in the passageway he had not yet explored.

With catlike quickness, he bounded noiselessly into the passageway by which he had come, and trusting to the comparative darkness for concealment he waited a few feet from the opening.

Prepared as he was for strange sights, Leslie gasped in amazement at the weird figure that entered —a tall, gaunt being, attired from head to foot in tight-fitting scarlet, and wearing a Mephistophelian hood and mask. As the man advanced to the center of the room with the springy tread of an athlete, Leslie saw that he was well muscled, and would make no mean antagonist in a rough-and-tumble fight. In his right hand he held a coiled rope, one end of which extended over his shoulder. He turned and eased a burden to the floor —a queer-looking contrivance that was fastened to the other end of the rope. It was cubical in shape, each dimension being about twelve inches, and was apparently made of steel. Projecting from the bottom on each of two opposite sides were three stout bars about four inches in length. Between each middle bar and corresponding end bar was stretched a powerful steel spring. The rope was fastened to an iron ring riveted near the bottom.

The demoniac figure knelt on the floor beside the thing and fondled it as one might a faithful dog. Then there issued from behind the hideous mask a horrid peal of laughter that caused cold chills to run up and down the spine of the American, for it was the same sound he had twice heard before, and each time after a headless victim had been found on the road.

The maniac —for such he appeared to be —continued to stroke the thing that lay on the floor before him.

"You have done well, degollador mio," he said. "Heh, heh, heh, my little one, you have done famously. Never was there a headsman like you. I swear it. Three heads between two suns! Cáspita! If the harvest continues thus, our vow will soon be fulfilled. Had that cursed Gringo not evaded us with his clever tricks we should have had four, but never mind, my pretty. I promise that you shall taste his cursed heretic blood ere another sun has set. Heh, heh, heh! We will fool this self-styled 'Devil-Fighter,' my little one. We will send him to try conclusions with Sátanas and his imps. But we must rest ere that is done, so now to business."

So saying, he half raised one end of the contrivance and pressed his knee against it. Then he grasped the two middle projecting bars and pulled them toward him with some difficulty because of the resistance of the powerful springs. At the sound of a sharp click, he released his hold and the bars remained where he had left them, the springs now drawn taut the entire length of the sides. He took hold of the ring, and gave the whole thing a shake. A gory head rolled out upon the floor, and Leslie instantly recognized the face of another of his guards, probably caught napping in the early morning hours.

Seizing it by the hair, the maniac carried it to the kettle and dropped it into the boiling water. Then, drawing a heavy machete from his sash, he prodded within the kettle, apparently testing the tenderness of the others.

Leslie, feeling that the time for action was at hand, stepped softly into the room, his six-shooter ready for action. The killer stood with his back toward him, still prodding the grisly contents of the kettle, but, loathsome and deserving of death though he was, Leslie could not shoot him down in cold blood.

"Surrender or die," he shouted.

The maniac swung around, and with the same movement, hurled the heavy machete straight for the breast of the American.

LESLIE had no time to dodge the keen blade of the killer that was hurtling toward his heart. He could not possibly have moved his body fast enough. He could move his hands, however, with lightning-like rapidity, or he would never have lived to earn the title of "Two-Gun Bart." With a movement quicker than eye could follow, he parried the blade with the barrel of his six-shooter, then covered his enemy once more as the weapon clattered to the floor.

"Your last chance, hombre," he roared, bounding forward. "Do you surrender?"

"I yield, señor. You see I am unarmed. What would you?"

"First remove that mask, that I may see what servant of Satan hides behind his features."

"But, señor ——"

"Remove it, I say!" He jammed his gun into the midriff of the killer.

"Let me go. I will pay you well —make you rich. The government offered you twenty thousand pesos. I will double it. I will ——"

"Dog!" With a sweep of his free hand Leslie tore the mask away. As he did so, a long, tangled beard tumbled down over the scarlet breast and the little watery eyes of the Anciano looked into his! Then the straight back bent, the shoulders assumed a familiar droop, and the voice became a sibilant whine.

"Mercy, good señor, en el nombre de Dios! Would you slay a helpless old man?"

"A cold-blooded murderer deserves no pity."

"But I was justified. I swear it. Give me a chance to explain."

"You couldn't possibly be justified, but if you are anxious to talk I'll listen for a little while."

"Gracias, señor. Do you know who and what I really am?"

"I know you as Tio Luis, the Anciano, and recently, as Tio Luis, the murderer. Anything else could matter but little."

"Of that you shall judge. My name is not Luis at all, but Tomas Perez. Neither am I of common mestizo stock, as you no doubt suppose. Through no fault of my own there flows in my veins enough Spanish blood to lighten the color of my skin and give me this beard, yet my people were Yaquis, and I am one of them, heart and soul.

"No doubt you have heard or read the sad history of my people. If you have not, then picture a tribe, a nation, peace-loving, hard-working tillers of the soil, oppressed for hundreds of years by every form of outrageous tyranny known to man, yet bearing it all with meekness, striving to overcome evil with good. Such was the nation of the Yaquis.

"Not content with squeezing the last peso from my people by unjust taxation, the government presently began the confiscation of our lands. A few of our sturdier souls rebelled and were promptly massacred. Then came the order for wholesale deportation. My thrifty father had acquired a small but fertile farm in the rich Sonora Valley. With the help of my mother, brother, sister and self, he had been able to eke out a meager existence and meet the extortionate demands of the tax collectors. One day the Rurales came with orders for the confiscation of our farm, and our deportation. We had done nothing wrong, yet we were Yaquis. That was enough for the government.

"A dashing young lieutenant was in command. My sister was pretty, and after he had ordered his men to drive us down the road like sheep, he bade her remain. I never saw her after that. With thousands of others of our race, we were transported to Yucatan, and there sold as slaves, mostly to the owners of the sisal hemp plantations. My mother died on the way —of grief, I think. My father succumbed, soon after our arrival, to the combination of hard work, cruel treatment and little food. Having the endurance of youth, my brother and I were able to keep body and soul together, though life was a constant horror. My chief consolation was derived from the good Padre who came to visit us, and who took quite an interest in me. It was in my talks with and observance of him that I gained a knowledge of priestly ways which has stood me in good stead since that time.

"But to go on. Although I have always been unusually quick-tempered, my brother had this trait to a more marked degree than I. Many times I have seen him fly into a frenzy over a mere trifle. Small wonder then, that he should, one day, let his hatred overmaster his judgment when the overseer struck him with a whip. He seized it and lashed his tormentor across the face, but his triumph was short —his end bloody —for the overseer decapitated him with his machete.

"For me this was the last straw. My sister had undoubtedly been ravished and murdered, my mother had died of grief, my father from cruelty, and now my little brother, the only one left for me to love, had been slain. All this I charged, and still charge, to the rapacity of the Mexican government.

"I was ordered to bury the body of my brother where it lay, unshriven, and mourned only by me. Over his grave, with tears streaming down my cheeks, I took a solemn oath that if ever I should be able to escape from that place alive I would take a thousand Mexican heads to pay the debt. I bided my time, and one day my opportunity came. When I left, I took with me the head of the overseer who had slain my brother.

"My first act on the open road was to rob a traveler of his mule, his pack, and his head. The pack, I found, contained a large store of cheap but gaudy jewelry which I hawked to advantage in the villages through which I passed. Whenever I saw the chance I would take a head, remove the flesh by boiling, and store the skull in my pack.

"Within a month my jewelry had all been sold and my money was exhausted. I obtained employment in the shop of a horseshoer, and it was while there that I conceived and secretly manufactured my little degollador, as I call it. It is so designed that when it drops over a man's head, the impact with his shoulders releases the razor-sharp blade, usually severing his head from his body. If the blade strikes a vertebra and sticks, then a sharp pull on the rope completes the job. But to go on with the story.

"I chanced to come here, and found that the place was admirably suited to my purpose. I did not live in the hut at first, but camped on the hillside not far from here. I succeeding in collecting many skulls from travelers riding beneath the cliffs, and of course I left no traces. One day while wandering on the hillside I came upon an opening that excited my curiosity. Seeing that it penetrated quite deeply I made a number of torches with dried grass and explored it. It led me to a small chamber behind the image of St. Anthony, and I found, to my amazement, that the slab which formed the rear panel of the shrine was, in reality, a door, easily opened from the inside, and swinging on brass hinges which, though corroded, were still serviceable. The drop of blood which you found at the base of the shrine bears me out in this, as I used that door when obtaining Pedro's head while you and José waited at the table for your chicken and tortillas.

"Exploring further, I found this room and its connection with the rear of the hut. The two rooms and the tunnels had evidently been used at some forgotten time by the keepers of the shrine, as a place of refuge during Indian attacks.

"That evening I took the head of Father Salvador while he was exploring the hillside for herbs. The next day, when a company of pilgrims came —they had already grown fearful of the neighborhood and came in numbers —I told them I had discovered the body near my camp. They swore he had been murdered by the devil, such being the popular superstition regarding the other deaths because I never left tracks, and it was not difficult for me to persuade them and the authorities who came later that I would be a suitable guardian for the shrine.

"One day I noticed the advertisement of a costumer in a paper from Mexico City which had been wrapped around a bottle of tequila given me by a pilgrim. I took a train down there and purchased three costumes from him like the one I now wear, giving, of course, a false name and address. The costume fitted well with the popular superstition regarding the place, and I felt that it would afford me considerable protection in case I was seen. Is there anything else that puzzles you?"

Leslie considered a moment.

"Yes. There are several things. For one, how does it happen that you can throw that thing with such uncanny accuracy?"

"In the same way that a vaquero can throw a riata with equal accuracy. By practise. I practised for weeks before I attempted to use it at all as a substitute for the machete. You are one of the very few live targets I have ever missed." He took a skull from the pyramid and handed it to Leslie. "Here. Roll this across the floor as swiftly as you wish, and let me show you."

Leslie waited for him to pick up the instrument of death and poise it aloft. Then he rolled the skull at the opposite wall. The Anciano hurled the thing with catlike quickness, but it fell, not over the skull, but over the head of the American. With a cackle of diabolical glee, the hermit jerked the rope taut.

LESLIE had holstered his revolver when he rolled the skull, hence both his hands were free. As the infernal machine descended over his head he instinctively put up both hands to throw it off, but this was prevented by the Anciano's jerking the rope taut. The keen blade was beneath his chin, almost touching his throat, but the trigger bars had not yet touched his shoulders. Had they done so his death would have been instantaneous. Still tugging at the rope, the hermit quickly shortened the distance between them. Then, grasping the ring with one hand, he dropped the rope and suddenly pressed down on the machine from the top with the other. The trigger bars struck Leslie's shoulders, but quick as the hermit had been, the American was again a shade quicker. Shifting his own hold, he had grasped the two bars that moved the blade, using the pressure on the back of his neck to keep it from his throat. The springs were tremendously powerful and he had all he could do to keep the keen blade away, the Anciano meanwhile keeping the thing pressed down on his head and jerking at the ring behind.

The struggle that ensued was the most fearful in Leslie's experience. The Anciano, he found, was a powerful athlete, notwithstanding his previous pretended feebleness. Twice his chin was cut to the bone by the razor-edged blade as the hermit jerked him about. The thing that galled him the most was the fact that he could not fight back. Although his six-shooters were belted about him he dared not let go with either hand to reach for a gun. His sole consolation was that his enemy was in like case so far as his hands were concerned, though a long way from being in such desperate peril.

Struggling intensely, bleeding profusely from the two cuts in his chin, Leslie soon found his strength ebbing at an alarming rate. He lashed out blindly with his feet and sometimes succeeded in kicking the enemy's shins, but the softness of the moccasins rendered this ineffective.

Knowing that the unequal struggle could not last much longer, Leslie at length resolved on a desperate plan. First relaxing, to make it appear that his strength was gone, he suddenly bent double and, at the same time, pushed upward with both hands. The hermit, taken completely by surprise, was first jerked forward, then catapulted over the head of the American. Although the movement jerked the machine from his head, Leslie received a severe cut on his forehead. The blood trickled down in his eyes, half blinding him, so that he could but dimly see the hermit lying on his back where he had fallen. Whipping out his knife, Leslie cut a piece from the riata and pounced on his prostrate foe, who appeared partly stunned from his fall. It was but the work of a moment to turn him over and bind his hands behind him. Another piece, cut from the same riata, served to secure his feet.

"There, damn you!" he snarled, rising unsteadily and wiping the blood from his eyes. "I guess you won't try any more tricks."

The hermit made no answer, but there came a sound that instantly put Leslie on his guard —the clatter of boots and the jingle of spurs in the passageway through which the Anciano had come. Instantly suspicious, Leslie drew both six-shooters and crouched behind the pyramid of skulls, convinced that no one but an enemy could have come from that direction. He lowered both guns with a nervous laugh a moment later, as José stepped through the doorway. Behind him came a dapper caballero whom Leslie instantly recognized.

"Hernandez!" he cried in surprise. "How the devil did you get here?"

"Ees ver' simple, amigo," Hernandez replied, warmly shaking the proffered hand. "I get desperate an' use the hot iron on that damn' peón today. Then he's talk plenty. Ees tal me Tio Luis gave heem the order to get your head, promising heem many blessing een return. He's tal heem that he who cuts a heretic gets eight years' absolution.

"Right away, I smell the mouse, and ride out here weeth two men. José, I find cooking breakfast, an' he's tal me you're in the hut. I go there, but find no one, so return to José. He's say maybe you 'ave gone to look for the trail where you shoot at the devil last night. We go there and find trail ourselves. It leads to a hole in the hillside an' a passageway which we follow to this place. I see you 'ave those devil, all right, but where ees the Anciano? You must get heem also to win those twenty thousand pesos, for both are guilty."

"Fair enough," replied Leslie. "I call you. Take a look at this man's face."

Hernandez bent and turned the Anciano on his back, then straightened up with a cry of amazement.

"Tio Luis! Son of wan gun! You win, amigo."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.