RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

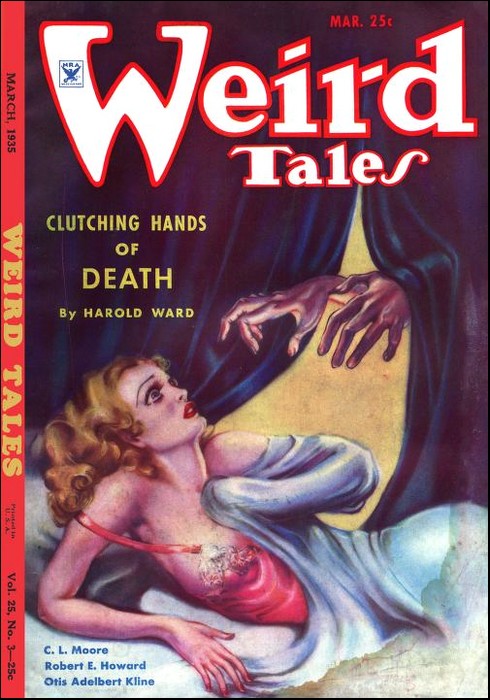

Weird Tales, March 1935, with first part of "Lord of the Lamia"

Otis Adelbert Kline has proved himself a master of many different kinds of stories—adventure, weird, detective, and pseudo-scientific tales. His published books include "Planet of Peril," "Prince of Peril," and "Maza of the Moon." He is also the author of an unusual motion picture, "The Call of the Savage." In the eery mystery story, "Lord of the Lamia," which begins in this issue, he weaves with skilful hands the threads of an amazing legend of old Libya into an astounding story of Egypt of the present day. We feel sure you will enjoy this story.

"There is no country in the whole world that hath in it more mar-

velous things or greater works than hath the land of Egypt."

—Herodotus.

JOHN TANE, archaeologist and explorer, fanned his youthful sun-bronzed features with his pith helmet, and with the tip of his polished oxford prodded the sleeping bowab, or doorkeeper, on the stone bench beside the door. The latter blinked drowsily, adjusted his red tarbush, and got to his feet.

"Is this the house of Doctor Schneider?" asked the American.

The swarthy Egyptian doorkeeper answered affirmatively, then inquired respectfully: "You are Tane Effendi?"

"I am." Tane glanced curiously up at the mashrabiyeh windows that jutted out over the narrow street, then back at the door on which he deciphered the Arabic inscription: "O God." And below this: "The Excellent Creator is the Everlasting."

"My master is expecting you, effendi." The bowab swung the door open, and shouted to someone inside. "Ya Hasan. Tane Effendi comes." Then he stood respectfully aside, with a courteous: "Bismillah! Enter in the Name of Allah."

Stepping through the door, Tane found himself in a narrow passageway which turned first to the right, then to the left, before he reached the inner court, where a tall negro servant saluted him with the salam.

"My master awaits you in the reception room," he said, opening a second door.

Tane entered a large room that was pleasantly cool after the glaring heat of the city streets. In the center of the tiled floor a fountain of marble and onyx splashed musically. Beyond it, at the far end, was an alcove, the three walls of which were fronted with cushioned diwans. On the middle one of these sat a short, corpulent man, with a round, moonlike face, a bristling blond mustache, and weak, watery eyes which squinted through thick-lensed glasses. He was smoking a narghile, and his costume was entirely oriental from skull-cap to cordovan slippers, yet the cast of his features was obviously Teutonic.

"Velcoom to Cairo, und to mein house, Herr Tane," he said, with an accent that matched his features.

"Greetings, Herr Doktor," replied Tane cordially, as he strode across the room. He kicked off his oxfords and seated himself, cross-legged, among the cushions.

"You vill haff a pipe und coffee? Yes?"

"By all means." Tane tossed his helmet to one side and ran his fingers through his tousled mop of damp blond ringlets. Then his eyes strayed around the room, and he said: "So this is the place you are leasing to me for two hundred pounds a year. Not half bad, if this room is a fair sample."

The doctor clapped his hands, and a dark-skinned servant girl entered noiselessly through a curtained doorway.

"A narghile und coffee, Marjanah," ordered her master.

"I hear and obey," she replied, and departed soundlessly.

Doctor Schneider turned to his guest. "You like it, eh? So do I. It is only because I need the money so badly to carry on my vork, dot I let it go."

"By the way, how is that new expedition of yours coming on?"

"Oh, yust so-so."

"Digging for the mummy of some ancient princess, somewhere in the Libyan Desert, weren't you?"

The little pig-like eyes of the doctor flashed in sudden anger. "How did you know dot?" he demanded. "Somebody has been vot you call, shooting the mouth off."

"Saw it in the paper," Tane replied. "They said you had exhausted your resources searching for that mummy, and had failed."

Doctor Schneider's look of anger vanished. "Dot iss true," he admitted. "Yet mit the money you pay me for this place, I vill carry on, und in the end I vill vin. You haff brought the money? Yes?"

"First six months' rent in advance. I believe that was the bargain," Tane replied.

He drew from his inside pocket a heavy bag, which chinked musically as he placed it on the taboret.

"Count it," he invited.

Nothing loth, the doctor complied. Then he swiftly thrust the bag beneath his sash as Marjanah came in with a tray containing a steaming brass coffee-pot and two tiny cups. Behind her trudged a native boy, carrying a water-pipe, which he set before Tane.

WITH the amber mouthpiece between his lips, Tane inhaled deeply, and the pipe purred like a stroked cat. The boy turned the charcoal while Marjanah poured the coffee. Then both withdrew.

"Where's my receipt?" asked Tane, exhaling a cloud of fragrant smoke.

"Here." The doctor drew a folded paper from beneath his clothing and passed it to his visitor. "I don't vant my servants to know I'm getting so much money. Servants gossip, und news travels fast. Und the profession of robbery is an honorable vone among the Arabs —ven they can get avay mit it. I'll moofe out in the morning. By the vay, how soon do you get married?"

"My fiancée is due here in three weeks," replied Tane. "We expect to get married as soon as she arrives, and to spend our honeymoon rambling about Egypt, with this house as headquarters. Then we'll settle down here and I'll go to work on the excavations."

"Yah? Dot's nice."

"Hope you'll find time to call and see us when we —say! What's that?"

He was interrupted by the sound of chanting outside the latticed windows, which swiftly grew in volume:

La ilaha illa I'laha: Mohammadur rasul I'lah. Sala I'lahu' aleyhi wa salami

"Vell! Sounds like a funeral procession. Vant to see it?"

The doctor rose and waddled to the window, swiftly followed by Tane. Six ragged blind men were walking slowly, chanting the Muslim profession of faith over and over. Behind them trudged two darwishes bearing the flags of their order. Then came an old white-bearded darwish, obviously a shaykh, a number of men, and a group of boys, one of whom carried a copy of the Koran on a small platform covered with an embroidered handkerchief. The boys were chanting in a higher and livelier tone than the blind men:

I extol the perfection of Him who hath created whatever hath form;

And subdued His servants by death;

Who bringeth to naught all His creatures with mankind;

They shall all lie in the graves.

Following the boys marched four pallbearers carrying a large coffin draped with a bright Kashmiri shawl. And behind the bier trooped half a dozen women, uttering piercing shrieks, and wailing: "O my master! O my lion! O camel of the house! O my father! O thou who brought my food and bore my burdens! O my misfortune!" at the tops of their voices.

"Must be the corpse of some great und holy darwish," said the doctor. "Maybe even a welee, a Muslim saint, that they are taking to the Bab en Nasr Cemetery." The procession continued on its way uninterrupted, until the bier was opposite the door of Tane's newly acquired house. Then the four pallbearers suddenly slumped to the ground, as if the weight of their burden had become intolerably heavy. Instantly the procession was thrown into confusion. Several of the marchers turned and tried to lift the coffin. But they appeared unable to budge it. A curious crowd quickly gathered, chattering and gesticulating, while the blind men, the boys, the darwishes and the mourners made zikker, by crying "Allah" over and over in rapid monotone.

"Gott im Himmel!" exclaimed the doctor. "A saint's miracle!"

"I don't see any miracle about it," said Tane. "Those men are exhausted."

"You don't understand. Vait und see vot happens," the doctor told him.

In the meantime, the old shaykh had shouldered himself to a position beside the bier. He held up one hand for attention.

"There is no Majesty nor Might, save in Allah, the Great, the Glorious!" he cried. "It is plain that our deceased brother, on whom be God's mercy, does not wish to be buried in the Bab en Nasr Cemetery. Allah willing, I will now determine his true wishes."

So saying, he stooped, and tugged at one end of the coffin as if he would drag it toward the door of the house across the street. But it remained immovable. Puffing from his exertions, he now tried to point it toward another door on that side, but failed. "It is not in that direction," he panted. "We must try another." He walked around to the other side, and tugged again, this time in the direction of Tane's doorway. The coffin slid easily and smoothly in that direction.

"Alhamdolillah!" he exclaimed. "God be praised! We have learned our brother's wishes. Take up the coffin, men." With bewildered expressions on their perspiring faces, the pallbearers swung the coffin to their shoulders once more. In the meantime, the shaykh had hurried to the head of the line and turned the chanting blind men so that they now faced Tane's door. The bowab, who had been watching the proceedings with popeyed amazement, swung the door open and stepped back respectfully as the first of the procession entered.

"Now what the devil are they up to?" asked Tane.

"Follow me, und you vill see," the doctor replied.

BY the time Tane and the doctor reached the courtyard, the last of the funeral procession was marching in. The bier, on arriving opposite the doorway, again stopped, and the pallbearers crumpled to the ground once more. Immediately the din of the chanters and mourners was redoubled as they again made zikker: "Allah! Allah! Allah! Allah!" repeated endlessly.

The white-bearded darwish, spying the two men before the door, stepped toward them.

"I am Shaykh Ibrahim," he said in Arabic. "Which of you two is owner of the house?"

"I am the owner," Doctor Schneider replied, "but my friend, here, is its new master, for I have just leased it to him."

"Then this occasion is singularly fortunate for both of you," said Shaykh Ibrahim, "for our revered and holy brother, Nureddin Ismail, has miraculously chosen to honor your house as his tomb and shrine."

"What the devil!" exclaimed Tane, in English.

"Take care, mein friend," warned the doctor. "You are in the Muslim quarter and must conform to its customs. 'Ven in Rome, do as the Romans.'"

"But I leased a home from you, not a mausoleum," objected Tane. "Good God! You don't mean to say they are actually going to bury the old buzzard here!"

"Dot's yust exactly vot they are going to do," replied the doctor. "Und if you know vot's good for you, you von't try to stop them. It vould be safer to slap a hungry lion in the face."

He turned to the old shaykh, who had been watching them in evident bewilderment, and said in Arabic: "Ve are pleased and honored that the saintly Nureddin Ismail should designate this poor house as his last resting-place. Are you aware of the exact spot where the welee wishes to be buried?"

"Not yet," replied Shaykh Ibrahim, "but with the help of Allah we will soon locate it."

"Hell's bells!" fumed Tane. "I won't stand for it. Don't mind it so much myself, but think of bringing a young bride into a house with the corpse of that old desert rat."

"The corpse von't bother you. It will bring you luck. This is the body of a saint, und it is a miracle you are vitnessing."

"Miracle, my eye! You can give me back my money and take your lease. I'll find another house."

"Not so fast, mein friend," grunted the doctor, a glint of anger in his watery eyes. "The deal is made, und already I, myself, have arranged for other quarters. Vot vould I do mit two houses, I ask you? Be reasonable. I couldn't help this. Vot do they say in your American contracts? 'Not responsible for acts of God.' Dot's also in your lease, if you vill take the time to read it. Today you are my guest. Tomorrow I moofe out, und the house is yours."

While the two were talking, the old man had been busying himself about the coffin, attempting to drag it this way and that. Finally, when he pulled it toward the door which led to the reception room, it yielded, sliding easily over the tiles.

"Glory to God, to whom belong all Majesty and Might!" cried the shaykh. "Our pious brother has indicated his choice."

Once more the pallbearers took up their burden, proceeding directly into the reception room with it, while the chanters and mourners, now mingled indiscriminately, crowded in after them. When Tane and the doctor finally succeeded in getting into the packed room, they found the coffin deposited on the central diwan which crossed the back of the alcove.

"Good Lord! They are not going to leave it there, are they?" gasped Tane.

"I'm afraid so," replied the doctor. "But it von't matter much. They'll vall it up und build a new diwan in front of the vall. Here come the masons, now."

While many willing hands removed mattresses, cushions, rugs, taborets and pipes from the alcove, the workmen mixed their mortar and brought in great heaps of bricks. Soon a substantial wall, reaching from one side of the alcove to the other, began to rise before the coffin.

"No reason vy ve should stay here," said the doctor, after they had watched the proceedings for some time. "Let's go upstairs." He opened a door on one side, which revealed a stairway leading upward. "Go ahead. I'll follow," he said.

TANE mounted the stairs, the doctor climbing heavily just behind him. At the top was a small landing, which led into a spacious room almost identical with the one they had just quitted.

"If I had a hareem," said the doctor, "this vould be the ladies' sitting-room, or majlis. But since I haff no hareem, it vill do as vell for us as the room below." He waddled to a door at the right and swung it open. "In here is your bedroom. Ven your servant comes mit your luggage I send him up. In the meantime, I have vork to do, if you will excuse me. Marjanah vill bring you a pipe und coffee, und ve haff dinner at eight."

"Thanks," Tane replied. "See you at dinner. And don't bother about the pipe. I think I'll take a nap. I'm dog-tired after my journey."

"All right. But I'll send you up a cold sherbet, anyvay. Or maybe you like something stronger."

"No, a sherbet will do nicely," replied Tane.

"Ya, sure. Sweet dreams."

Tane had scarcely divested himself of coat, tie and shoes, and stretched himself on the diwan, when Marjanah arrived, carrying a tray on which stood a tall slender glass filled with cracked ice and a pink liquid. He tasted it; it proved to be pomegranate juice sweetened with honey.

Shortly after he had finished his refreshing drink, the American sank into a deep slumber.

THE doctor, as soon as he had left Tane, waddled across the majlis, descended the stairs, and entered the reception room, where the masons already had the brick wall before the coffin shoulder-high. He passed thence through another doorway via a hallway to the kitchen, where Mustafa, his Turkish cook, was preparing a huge quantity of lamb, cut in small pieces and grilled on skewers, heaping platters of rice drenched with clarified butter, and immense quantities of bread.

A half-dozen other servants stood about, sampling the food, among them Marjanah. The doctor beckoned to her.

"Prepare a sherbet for mein guest," he said, "quickly!" Then he turned to Mustafa.

"Start sending the food into the courtyard," he ordered. "I vant to get this commotion over mit."

With voluble bursts of Turkish and Arabic, and much violent pushing and pulling, the cook soon got his fellow servants started toward the courtyard, staggering under huge platters of rice, grilled lamb, and bread.

Doctor Schneider watched them impatiently. Then he turned, as Marjanah came up with a tray on which was a small glass of pomegranate juice and honey.

"Here. Giff me that tray," he commanded. "Then get me a tall glass full mit cracked ice."

As soon as her back was turned, the doctor glanced slyly at Mustafa. The cook was busy over his stove. Quickly extracting a small phial from beneath his garments, the doctor emptied its contents into the sherbet. Then he concealed the phial and waited. Presently Marjanah returned with the glassful of cracked ice. Into this he emptied the smaller glass.

"Take it up to Tane Effendi," he told her.

As the girl departed to do his bidding the doctor rubbed his pudgy hands together and looked after her with a smile of satisfaction. Then, after giving Mustafa minute instructions about dinner, he went out into the courtyard. The male members of the funeral cortege, together with the masons and their assistants, were seated about the platters of food which had been placed in the courtyard, eating ravenously. At the other side of the courtyard, the women were as busily engaged with a smaller consignment of meat, rice and bread.

Waddling across the court, the doctor saluted his guests as he passed them. Then he entered the reception room where Shaykh Ibrahim sat before the walled and plastered tomb, performing the office of mulakkin, or instructor of the dead.

"O servant of God!" he was saying. "O son of a handmaid of God! Know that tonight there will come down to thee two angels commissioned respecting thee. When they say to thee, 'Who is thy Lord?' answer them, 'God is my Lord,' in truth; and when they ask thee concerning thy Prophet, say to them, 'Mohammed is the Apostle of God,' with veracity; and when they ask thee ——"

"Enough, mein friend," interrupted Doctor Schneider. "Vy go on mit this farce, ven only you and I are left in the room? Let us get down to business."

"Waha! You are right," replied the shaykh. "Those dogs and sons of dogs have all deserted the service at the first smell of meat. No better than hyenas and jackals are they, for they hold the comforts of the flesh to be greater than the blessings of the spirit."

"Vell, vat of it? They did yust vat ve vanted them to do. You are sure everything is all right —that the coffin is unopened?"

"Not only am I sure, but I will swear it by the triple-oath."

"Dot's enough. I belief you. For each virtuous deed is a reward. You haff done vell. I promised you fifty pounds. Here is your gold."

The shaykh greedily reached for the bag which the doctor passed to him, and emptying the clinking contents in his lap, made a swift count.

"I was reduced to beggary by the fees of the mourners," he said, after he had replaced the last gold piece in the bag.

"Another pound for that," the doctor told him, tossing a piece into his lap.

"And the pallbearers demanded a ruinous sum because of the extra work."

"Another pound for them, und it is the last," the doctor told him, flipping him another gold piece. "Go, now, und partake of the food mit the others. Then get them out of mein house as soon as you can. I haff vork to do."

WHEN John Tane awoke, the full moon was shining down on him through the ornate lattice of the mashrabiyeh window, making intricate shadow patterns on the diwan and floor. He sat up with a start, and was instantly aware of a headache and a feeling of nausea, accompanied by a peculiar bitter taste and a mighty thirst.

He glanced at the luminous dial of his wrist-watch. Nearly midnight! He had slept eight hours. Instantly he realized that only one thing could have produced this long sleep with its disagreeable after-effects. He had been drugged. But by whom? And for what purpose?

Someone, he noticed, had drawn a coverlet over him. And on looking around the room he discovered that his baggage had been delivered. That meant that his Arabian servant, Ali, had been here. Perhaps he was sleeping in the majlis outside his door. Softly he called: "Ali."

There was no response.

He called more loudly: "Ali!"

Still no answer.

Shirtless and shoeless, he rose and walked to the door, his feet making no sound on the thick rug. The majlis was lighted only by the moon, but he easily made out the form of a man lying on a mattress beside the door. A closer inspection revealed the hatchet-like features and thin wiry form of his servant, Ali.

Tane shook the sleeper —gently at first, then with considerable violence. But he was unable to awaken him. Evidently Ali, also, had been drugged, and quite heavily.

As he stood, nursing his splitting head and wondering what it all meant, Tane heard the sound of somebody running rapidly on the floor below, followed by a thud and a groan. Then there was a sound as of someone dragging a heavy body across the floor. Obviously, there was deviltry afoot, and he and his servant had been drugged in order that they might not see or hear what was going on. Swiftly and soundlessly he bounded to the stairway and descended to the reception room. Like the upper rooms, it was unlighted save by the rays of the moon, but a faint yellow light filtered between two silken curtains that hung before one of the doorways. And from behind the curtain there came a strange muttering in a tongue that seemed vaguely familiar. Suddenly he recognized it as ancient Egyptian.

Pushing the curtains aside, he crept along the hallway behind them until he came to the door of a room through which the yellow light streamed and from which the sounds emanated. The light, he saw, came from two short, thick candles set in a paneled niche in the wall. The panels had been pushed to the right and left, revealing a dark opening, before which stood a tall thin man with a scraggy gray beard and a prominent hooked nose that gave him a hawk-like look, dressed in the costume of a Persian of rank and wealth. In his hand he held a yellow scroll which he was reading aloud by the light of the two candles.

Except that the cushions and coverlets on one of the diwans were in disarray, Tane saw no sign of a struggle. He wondered if this man were an intruder, who had come to read some ancient litany for the departed welee.

"Pardon me," he said. "I thought I heard ——"

His sentence remained unfinished, for at the first sound of his voice the hawkfaced man dropped the scroll and turned, regarding him with glittering eyes. Then his lean, claw-like hand shot down and came up with a short loaded club which had been thrust beneath his sash. With a cat-like agility most remarkable in a man of his years, he sprang straight for Tane.

The American stepped nimbly to one side, barely in time to avoid a vicious blow. Then he leaped in, seized the Persian's arm, and clamped on a bone-crushing wrist lock. Instantly the weapon clattered to the floor. Tane immediately shifted his hold, drew the arm of his attacker up over his right shoulder, and heaved. The hawk-faced man described a sweeping arc, and alighted in front of the doorway with considerable violence.

Tane bent and retrieved the club, then stood awaiting a renewal of the attack. But to his surprise, his antagonist, who had sprung to his feet and drawn a wicked-looking knife, suddenly darted out of the door and down the hall. The American followed, but was barely in time to see the hawk-nosed one dash across the reception room and out into the courtyard.

FURTHER pursuit being useless, Tane returned to the lighted room and, impelled by curiosity, went up to the niche to examine the scroll which the old man had been reading. Instead of paper, parchment, or papyrus, it was of thin beaten gold, on which the hieroglyphic characters were embossed and painted with lacquer. He instantly recognized the characters as very ancient, apparently belonging to the second or third dynasty. They were so battered, and so much of the lacquer had cracked off, that reading them was quite difficult; so he pronounced the words aloud to make sure of the sound and sense of each:

Rekh nefer st'er t'et-a ten au atef-a neter nejer

Re au mut-a heqt nebt taui Pilatra—

As he read, he mentally translated:

O fortunate man! Sleeping, I speak to you. I am the daughter of the beautiful god Re, and Pilatra, Royal Princess of the Two Lands. Being less than goddess, I must sleep, but being more than woman, I never die, and blessed indeed are you who awaken me. For though all Libya once bent beneath my scepter, you now have the power to make me your slave, for ever—

Tane read on and on, but beyond this point, though he was able to pronounce the words by means of the phonetic symbols, he could not understand them. Evidently they constituted a mystic formula, couched in some ancient and long-forgotten language.

So absorbed had he been with the ancient scroll that he had noticed no other details. Now, however, as he laid it down, he turned his attention to the dark opening at the rear of the niche. Just inside the opening, he was surprised to see the side of a coffin, the lid of which had been removed and tilted back against a newly built brick wall behind it. Why, it was the rear of the wall the masons had built that afternoon! And this must be the coffin of Nureddin Ismail! The panels of the niche in this room had opened into the alcove of the reception room. Now they opened into the tomb of the welee.

Impelled by curiosity, Tane leaned forward and peered into the coffin. Then he exclaimed in amazement. For it contained, instead of the shrouded corpse of an old darwish, a richly gilded and lacquered mummy-case, the lid of which was fashioned and colored in the likeness of the swathed form of a slender girl, with lovely, youthful features crowned by a royal diadem that was fronted with a golden uraeus.

Instantly, the archaeologist in Tane came to the fore. This, he realized, was a rare find, such as might not be turned up again in a century of searching. Eager to examine the mummy, he carefully lifted the cover, and leaned it back against the lid of the coffin. Then he gasped in astonishment. For instead of a mummified human being, he saw only a long, rope-like thing which stretched from one end of the mummy-case to the other, swathed in musty linen wrappings that were brown with age. At the head-end of the case, the tip of the thing entered a jewel-encrusted golden crown, fronted by a uraeus similar to the one depicted on the lid.

Wondering what could be wrapped in the cerements, he loosened and began unwinding those at the head end. So weakened were they by the dry rot of countless ages, that despite the utmost care, they broke and fell apart at almost every turn. Beneath them were stronger wrappings, which he also unwound, revealing the scaly head and body of a large haje, or African cobra, in so perfect a state of preservation that the black and yellow coloring of its gleaming scales was as bright as that of a healthy, living specimen.

Tane was not surprised to find a serpent swathed in mummy wrappings, for he knew that the ancient Egyptians embalmed and buried many of their sacred beasts, birds and reptiles, as well as favorite household pets. But he was surprised to find it in so perfect a state of preservation, and in a coffin which had obviously been constructed for the mummy of a royal princess, with its head in a jeweled golden crown which might once have graced the fair brow of the lovely being whose likeness was depicted on the lid.

Carefully, he slid the diadem from beneath the serpent head, and held it up beside one of the candles for a detailed examination. The uraeus and framework were of solid gold, exquisitely wrought, and studded with gems, the most brilliant of which were two sparkling emeralds that formed the eyes of the serpent. Only fragments remained of the cloth lining and plumes —the "two feathers of truth" —which, like the cerements of the serpent, had reached a state of extreme fragility.

Some tiny hieroglyphics graven inside the framework and containing a royal cartouche, caught his eye. He read:

Wrought for the great goddess Lamia, holy and beautiful Queen of All Libya, Daughter of the Sun and Mistress of Life and Death, by the least of her slaves, Mena the goldsmith.

Scarcely had he finished reading these lines when a rustling sound attracted his attention. Turning, he started in surprise and alarm, at sight of a large black-and-yellow cobra crawling out upon the ledge of the niche. Knowing how deadly the bite of a haje can be, he leaped back instinctively in an effort to get out of reach of those terrible fangs. At this, the snake slithered down from the ledge and glided swiftly toward him, knocking over and extinguishing one of the candles as it did so.

Wildly, he looked about him for some avenue of escape, but he could see none, for already the reptile was between him and the doorway. In his defenceless position, he used the only weapon within reach, the short club which he had taken from the hawk-nosed intruder, throwing it with all his might. Straight for the serpent's head flew the loaded billy, yet the snake avoided it with ease, and came on. Desperate, Tane hurled the only remaining thing he might use as a weapon —the heavy golden crown.

Though his aim was good, the serpent once more dodged the throw, and the crown rolled out beneath the hangings that curtained the doorway. Fearful of those deadly fangs, he again leaped back, but this time his feet encountered an unexpected obstruction. He fell over backward, alighting on the floor in front of a diwan.

Then two things happened simultaneously. The remaining candle in the niche sputtered out, and a hollow groan sounded from the diwan behind him.

TANE scrambled TO his feet, and strove to see the creature that menaced him. But there was no window in the room to admit the moonlight, and his eyes could not penetrate the darkness. From the direction in which he had seen the serpent, he heard an ominous rustling, which grew fainter, and presently ceased. This led him to believe that the reptile had coiled and was ready to strike. In the meantime, there came the sound of heavy, labored breathing from the diwan, followed by another groan.

Suddenly he remembered a box of safety matches in his trousers pocket, and lighted one. The first thing the circle of yellow light revealed was the object which had tripped him. It was a man's leg, projecting from beneath a pile of rugs and pillows on the diwan. He held the match high above his head until it burned his fingers, as he strained his eyes into the gloom for sight of the serpent. But it had disappeared.

Lighting another match, he turned his attention to the person on the couch. Swiftly, he pulled away the rugs and cushions, revealing the rotund form and porcine features of Doctor Schneider. The doctor's face was streaked with blood from a cut on his forehead, and he was breathing heavily.

"You!" Tane exclaimed, staring down at the doctor in amazement. "What happened?"

"A robber," groaned the doctor. "He took mein gold und broke mein head. There is a lamp on that taboret. Light it, und help me to the bathroom. I must have vater und a bandage."

Tane located the lamp and lighted it with a third match.

"There's a big haje loose in the house," he said, as he helped the doctor to arise. "We'll have to watch our step."

"A haje! Ach, mein Gott! But vere —vere did it come from?"

"I saw it crawl out of the niche. By Jove! I must have unwrapped it myself. There was a snake swathed in mummy-cloth and I thought it was dead. Good joke on me."

"Good joke! Gott im Himmel! If only it vas a joke! But neffer mind. Help me to the bathroom."

Tane assisted the doctor to arise. Then, juggling the lamp with one hand, and supporting the injured man with the other, he led him across the room and through the doorway, meanwhile keeping a sharp lookout for the venomous haje.

"Second door to the right," grunted the doctor. "Ach, mein head! It goes round like a pinwheel."

There was a well-stocked medicine cabinet in the bathroom, and Tane, after mixing the doctor a stiff drink of brandy and water, applied an antiseptic and deftly bandaged his head.

"I feel better, now," said Doctor Schneider, when Tane had finished. "Better haff a drink, yourself. You look as if you need one."

"You said it." Tane poured out three fingers, and took his brandy neat. "Maybe it will help to clear my head. Somebody drugged my sherbet. And my servant, Ali, sleeps as if he, also, had been drugged."

"It must haff been an inside chob," said the doctor. "Someone learned I had all that gold, und planned to rob me. But tell me vot happened before you found me. Did you catch sight of the robber?"

"I chased an old, hawk-nosed Persian out of the place," Tane replied. "He was reading from a golden scroll before the niche, behind which the mummy-case was so cleverly concealed this afternoon."

"Scroll? Mummy-case?" The doctor appeared puzzled. "But tell me, mein friend, had he finished reading the scroll when you appeared?"

"I don't think so. In fact, I'm quite sure he hadn't, for he was still on the part I could understand. There were a number of words that must have been in some pre-dynastic dialect, which I could not understand."

"So! Then you read the scroll?"

"Yes."

"Aloud?"

"Aloud."

"Hum. Und you say you saw a mummy-case?"

"I not only saw a mummy-case, but there was a mummified serpent in it, and a golden diadem. I unwrapped the serpent. And it, or another, later crawled out of the niche, knocked over one of the candles, and came toward me. I was examining the diadem at the time, and first tried to stop the snake by hurling the club of the Persian. I missed, and so threw the only thing I had at hand —the crown. The serpent dodged, one of the candles burned out, and then I heard you groan."

"Vell. The first thing ve better do iss look for that snake. It von't be safe for any of us to sleep mit it crawling around the house. I haff a couple of simitars hanging on the vall of the reception room. Ve'll get them und look around." Cautiously, they made their way to the reception room. The doctor took down two crossed simitars from the wall and handed one to Tane. Then he lighted another lamp.

"Suppose you look in the courtyard," he said, "vile I search in the back of the house. Say, vat about that crown you threw at the haje?"

"It rolled out into the hall."

"Funny ve didn't see it. But neffer mind. I look for it, also. If you see or hear anything strange, call me —schnell!"

LANTERN in one hand and simitar in the other, Tane opened the door and stepped out into the courtyard. Here the moonlight was so bright that the lamp was superfluous, except in the darker corners, where he poked about cautiously with the simitar. After making a complete examination of the courtyard, he stepped into the entryway. At the second turn, he came upon the body of a man, lying with arms outflung. It was Wardan, the bowab. Tane bent over him. One look convinced him that the doorkeeper was dead. His tarbush was lying on the tiles, and the back of his shaven head was crushed in, as if by some heavy instrument. The door stood slightly ajar, and Tane closed and bolted it. Then he made his way back to the reception room. It was untenanted, but the glint of lamplight from the hallway told him that there was someone in the other room. Parting the curtains, he traversed the hallway and entered the room, where he found the doctor staring at the niche.

"Vell. Vot luck?" asked the doctor, turning at his entrance.

"I didn't find the snake," Tane told him, "but I found your bowab, murdered."

"Wardan dead! Poor devil. Then he vasn't in on the robbery plot. Say, vot's all this cock-und-bull story you haff been telling me about mummy-cases und snakes und crowns? There vas no crown lying in the hallvay. Und vere is the golden scroll? I found the club all right, in here on the floor —a deadly thing loaded mit lead. But you couldn't haff seen a mummy-case behind these panels. Look."

Tane looked. Instead of the dark opening behind the panels, he now saw a solid brick wall. He looked closer. It was not the new wall put up by the masons that afternoon, but a very old wall, which evidently had stood for many generations. And it fitted so tightly against the back of the niche that nothing much thicker than a sheet of paper could have been inserted between it and the sliding panels.

"Well I'll be ——"

Tane leaned over and tapped the wall with his knuckles. Then, setting down the lamp, he flung his entire weight against it, pressing with both hands. But it was as solid as the house itself.

"It appears, mein friend," said the doctor, gravely, "that the drug you were given made you see strange visions. Hashish, maybe, eh?"

"But I tell you I saw and touched all those things. They were real. I handled them. I read the scroll."

"Tactile impressions are as easily imagined as visual," replied the doctor. "You can see for yourself that you couldn't possibly haff looked into any opening behind the niche, unless you haff X-ray eyes und can look through a vall. Und even so, you vouldn't haff X-ray hands that could reach through the vall. No, mein friend, you are the victim of a drug-dream —a hallucination. Better forget that part of it when you talk to the police. I'll have to notify them, on account of Wardan's death. Just tell them you chased out a robber who had slain Wardan, knocked me unconscious, und robbed me."

"Maybe you're right," agreed Tane, "but it's damned queer, just the same."

"You vait here," said the doctor. "I'll go und call the police. Und don't try to make them believe that drug-dream, or ve are liable to be accused of murder."

The doctor took one of the lamps and went out. As soon as the echo of his footsteps had died away, Tane took up his lamp and once more went to the niche. Again he examined the brick wall and the sliding panels. But he could find nothing to indicate that they had not been in this same position for generations. Presently he thought of the candles which had been burning on each side of the niche. Each had been in a small brass tray, but one, he recalled, had been upset by the serpent. There should be some tallow on the ledge. A careful examination revealed none. Then he looked above the places where the candles had stood. Above each was a spot which was considerably darker than the surrounding wood. He rubbed one of the spots, and his finger came away with a smudge of greasy carbon. So there had been two candles burning there, after all. But what had become of them? And what had happened to interpose a solid brick wall against the back of the niche during the time he had been exploring the courtyard?

As he was about to return to his seat on the diwan, he noticed a white splotch on the floor. Bending, he picked it up. It was a piece of tallow which had spattered from the overturned candle. At the sound of approaching footsteps, he thrust this meager bit of evidence into his pocket, resumed his seat on the diwan, and lighted a cigarette.

DOCTOR SCHNEIDER waddled into the room, followed by four burly native policemen.

"There is the hashisbin!" he said in Arabic, pointing a pudgy finger at Tane. "Overpower him quickly, for he is very dangerous. He slew Wardan mit a single blow, und came near to killing me."

"Why, you ——"

Tane sprang to his feet, and lashed out with both fists as the four husky natives pounced upon him. His first blow found a brown face, and its owner staggered back to crash against the opposite wall. His second caught another policeman in the midriff, and doubled him up, left him gasping for breath. But the other two each caught an arm, and their combined weight bore him down upon the diwan.

The American pretended to go limp. Then he suddenly wrenched his right arm free. The man on his left still clung, but a short-arm punch to the point of the jaw broke his hold, and he slumped to the floor. Again the man on his right seized his arm, but he drove a crashing left hook to the fellow's ear, tore his arm from the clutching brown hands, and leaped to his feet.

At this instant, a tall, lean, hatchet-faced Arab appeared in the doorway. It was Ali, and in his hand he held Tane's Colt forty-five.

"Good boy, Ali!" he exclaimed. "Give me that gun."

Then he whirled, facing the five men in the room. "Hands up, all of you," he ordered, "or I'll shoot, and shoot to kill."

Sheepishly, the four policemen raised their hands. But the doctor paid no attention to the command.

"You, too, Schneider," said Tane, pointing the pistol in his direction.

"Go ahead, shoot me. You vouldn't dare," scoffed the doctor.

"Oh, wouldn't I?"

The forty-five roared, and the German's silken cap leaped from his bald head.

"Himmel! Vould you murder me?" the doctor cried, elevating his pudgy hands with surprising alacrity.

"A moment ago you accused me of being a murderer," Tane replied. "I might be tempted to live up to the name. Steady!" His gun muzzle swung toward one of the policemen whose hands were wavering downward, and once more they became stiffly perpendicular.

"Now, doctor," said Tane, "what's this all about? And why did you accuse me of murder after I drove off your attacker and bound up your wound? You'd better come clean, or ——"

The sentence remained unfinished, for at that instant he suddenly felt something hard prodding him in the back, and a low, well-modulated voice from behind him said: "I'd advise you to drop that gun."

Tane dropped the forty-five. There was nothing else for him to do. As the heavy weapon thudded down on the rug, the pressure on his back was removed. Then the curved handle of a Malacca cane flashed out from behind him, hooked the pistol, and dragged it back.

"And now, effendi, you will walk to the diwan and seat yourself beside Doctor Schneider," continued the suave voice.

Tane walked obediently to the diwan, turned, and sat down beside the doctor. Then a man, evidently an Egyptian, stepped through the curtained doorway. He was slender, of medium height, with dreamy brown eyes and a closely cropped, jet-black beard. He wore a green turban and a brown burnoose which was open in front, revealing a gold-embroidered white kamis, confined at the waist by a scarlet sash. Tane judged him to be about forty years of age. In one hand he carried a Malacca stick, and in the other, the American's revolver. And Tane suddenly realized that he had been neatly tricked —forced to drop his weapon by the prod of a walking-stick.

"Hagg Nadeem!" exclaimed the doctor. "How in ——"

"At your service, as always, Doctor Schneider," said the Egyptian, politely, with a profound bow. "I happened to be passing, and heard the sound of a shot. The door was ajar, so I came in to investigate. And now, perhaps, you will acquaint me with the cause of this disturbance, as well as the reason why four of my men have been held up at the point of a gun in your house."

Tane had heard of Hagg Nadeem. And the reports he had heard had been so many, so varied, so tinted with superstition, and so utterly preposterous, that he had almost come to regard the man as a purely mythical figure. Not only was he said to be an dim, a Muslim holy man, learned in the Koran and the faith of al Islam, and a hagg who had made the prescribed pilgrimage to Medina and Mecca, but he was also an Oxford graduate, and well informed in the sciences and the arts. Among his own people, many revered him for his piety and religious learning. Others condemned him as a jinni in league with Shaitan the Damned, a necromancer, a worshipper of Egypt's ancient and terrible gods, and a practiser of both white and black magic. Though he bore no official title, soldiers, police, and other public servants, both military and civil, bowed to his authority without question. And it was whispered that he was a member, if not the actual chief, of the secret police of the country.

For a moment, the German seemed too stunned with amazement to reply to the query of the Egyptian. But the latter persisted.

"I await your explanation, doctor," he said.

"I haff already made mein explanation to these four bolicemen," grunted the doctor, at length. "That man," indicating Tane, "killed my bowab mit a club, und tried to brain me. I escaped him, und called the bolice."

"The doctor," said Tane, "is a cockeyed liar."

"One moment, effendi," said Nadeem. "Permit me to finish questioning him." He turned once more to Doctor Schneider. "You say this man tried to kill you. Why?"

"He vas drug-crazed —mit hashish, probably. Don't know vere he got hold of it. I calmed him down, took the club avay from him, und vent und bound up my head. Then I called the bolice. Ven they tried to arrest him he fought like a fiend. Then his servant came und gave him the pistol, und ven I vouldn't put up my hands, he took a shot at me. The bullet vent through my cap, as you can see." He pointed to the punctured bit of headgear behind him.

"Why, of all the unmitigated prevaricators!" Tane's rage all but choked him.

"Here's the club," continued the doctor, tossing the loaded billy at the feet of the Egyptian. "He told some vild, harebrained story about candles burning in the niche, an ancient scroll of solid gold, und a mummy-case mit a snake in it. I had to humor him in his murderous mood, of course, but I didn't belief him. Hashish makes men see queer things."

"Quite true," agreed Hagg Nadeem.

He turned to Tane. "May I inquire your name?" he asked.

"John Tane of the American Archaeological Society."

"What were you doing in this house at this time of night?"

"I rented the house from Doctor Schneider yesterday afternoon," Tane replied. "Paid him six months' rent in advance. He was to move out in the morning."

"I see. Sorry, Mr. Tane, but I'm afraid I'll have to place you under arrest. This, I take it, is your servant. Since you are partly disrobed, I'll permit you to send him up for such clothing and other articles as you require, with two of my men as an escort."

"This is a damned outrage," fumed Tane. "You'll hear from my Government on this, and don't forget it."

HAGG NADEEM smiled sweetly, seemingly unimpressed. While Tane gave orders to Ali, Hagg Nadeem lighted a cigarette and strolled carelessly about the room, as if there were nothing there that particularly interested him. Yet Tane, somehow, felt that his searching brown eyes were taking in every detail.

Ali returned in a few minutes with the required things, and deftly assisted his master in making himself presentable.

"Since your servant is not accused, he may remain here and look after your things," said the hagg. "And now, if you are ready, we will start."

He turned to Doctor Schneider. "You will be expected to appear before the kadi, to prefer charges against this gentleman in the morning," he told him. "Come, Mr. Tane."

As they passed through the outer door, Tane noticed that the grisly object which had once been Wardan the bowab had been removed —probably by his relatives.

They traversed several narrow, deserted streets in silence. Then Nadeem said: "Though I grieve to confess it, our jail is rather a filthy place. Most of the malefactors brought there crawl with vermin, and they are none too clean. I'm afraid it will be very disagreeable for you."

"I don't doubt it," replied Tane. "But why rub it in?"

"I was about to suggest," continued the hagg, "that you spend the night in my home —let us say, as my guest. Under guard, of course."

"Thoughtful of you. But I wouldn't think of imposing ——"

"No imposition, I assure you. It will be a pleasure. After all, you have not yet been proved a murderer —only accused. It may be that you are entirely innocent of even any complicity in the matter."

"Thanks for the charitable thought."

They strode on again for some moments without conversation. Then the Egyptian paused before a doorway, and rapped sharply with his Malacca. A sleepy bowab opened the door. "Here is my house," said the hagg. "Bismillah. Enter in the Name of Allah."

"Praise His Name," replied Tane, in answer to the Arabic politeness, and stepped inside, followed by his host and the four guards.

IN its arrangement, the house of Hagg Nadeem was quite similar to the one Tane had rented some hours before, but much more luxuriously appointed. As he sat in the reception room, sipping a sherbet and smoking one of his host's long oriental cigarettes, his eyes strayed from one to another of the priceless objects of antique art which the room contained.

"I had not heard that, among other things, you were a connoisseur of antiques," said Tane.

"These things? Mere trifles. Some day, inshallah, I will show you my private museum." He smiled his sweet, dreamy smile. "But now, effendi, I should be infinitely obliged to you if you would relate to me, in detail, everything that happened after you called on Doctor Schneider yesterday afternoon, to rent his house. I know that you are weary, and need rest. At the same time, please realize that you are accused of a serious crime. If you are innocent, the quickest way you can aid me in learning the truth is by telling all you know."

"I have nothing to conceal, though some of the things I have to relate may sound fantastic —even unbelievable," Tane replied.

"Please let me be the judge of that, effendi. Proceed."

The American related his story in detail —his payment of the gold to Doctor Schneider, his awakening near midnight with the unmistakable signs of having been drugged, his encounter with the hawk-nosed Persian, the incident of the scroll, the mummy-case and the serpent, his finding of the injured doctor, and the latter's subsequent treachery.

"Did you tell Doctor Schneider that you had read the scroll aloud over the mummy-case and then unwrapped the haje?" asked Nadeem when he had finished.

"I did," Tane replied, "but he evidently thought that part of it all a hashish dream. He almost succeeded in convincing me that this was the case, also —would have done so, in fact, if it hadn't been for this." Reaching into his pocket, he produced the bit of candle wax he had found on the floor and passed it to his host.

The latter sniffed at it and tested its hardness with his thumb-nail.

"Looks genuine enough," he said. "I'll have it analyzed and checked microscopically, though, to make sure."

"To make sure of what? What do you mean?"

"This," said the hagg, "is evidently a bit of one of the candles used by the high priests of a certain secret sect of ancient times, when practising a branch of their black art —specifically that of raising the dead. These candles were made from the fat of virgins secretly sacrificed before the crocodile god, Sebek. This fat was mixed with beeswax in which had been incorporated several potent drugs and a compound of aromatic resins, gums and essential oils."

"Good Lord!" exclaimed Tane. "You don't mean that innocent young women were actually slaughtered to make these candles! Why, I have been studying the ancient records for years, and never heard of such a thing. If this is true, I'll have to admit that you are far better informed than I on the doings of the ancient Egyptians, despite my years of study and research."

"There are reasons why I should be so informed," replied Nadeem, passing him the gold-and-ivory cigarette box. "It happens that I am directly descended from a high priest of Sebek. Despite the fact that I am a Muslim, a believer in the one true God, as have been my ancestors for many generations, the ancient documents of my forebears have been passed down from seventh son to seventh son intact. It appears that I have been the first of the line with the temerity to break the ancient seals and examine them, since the conversion of the family to the faith of al Islam."

Tane selected and lighted a cigarette. "You have no idea," he said, "how intensely interesting all this is to me. I presume that none but a seventh son of a seventh son of your house would be permitted to examine the documents."

Nadeem smiled his sweet, pensive smile. "Unfortunately, that is quite true. In fact, there is an ancient curse laid upon the custodian who allows them to fall into alien hands —a curse which would bring a horrible doom not only upon the desecrator, but upon my family in all its branches."

"And you believe in the efficacy of the curse?"

Nadeem shrugged. "I should dislike to test its power. There have been numerous instances, within your memory and mine, in which people have suffered death, sudden and inexplicable, after defying such a curse. It will be a long time before the world forgets what happened to the desecrators of the tomb of Tutankh-Amen, son of Amen-hetep the Fourth, which was protected by such a curse."

"It is my belief that these, and all other similar instances, can be traced to natural causes," said Tane.

"Mine also," replied the Egyptian.

"Has it ever occurred to you that such a curse might operate through natural channels?"

"Can't say I ever thought of it in that way."

"In many things the ancients were better informed than are we," Nadeem said. "And while I grant you that there is nothing really supernatural, that all things must take place in accord with the laws of Nature, or Allah, it is my belief that these ancient priests and master magicians —the genuine adepts —were in possession of a number of scientific truths which gave them tremendous power over the uninitiated, and which have not been rediscovered by our modern scientists. I do not claim that they really understood all the natural laws they put into effect in performing their so-called miracles and feats of magic. However, they had much leisure for study and experiment, and learning that certain causes produced certain mysterious effects, made use of them."

"I can't think of any application of natural law which would explain my weird experience of this evening," said Tane. "I would prefer to believe that the greater part of it was a drag dream, but the presence of the carbon spots in the top of the niche and a bit of candle wax on the rug is evidence that at least part of the experience was real. It is difficult for me to believe that a serpent, dead for five thousand years, should suddenly come to life and crawl away because of the reading of a bit of mummery over it, accompanied by the burning of two candles made from the fat of virgins. That's too preposterous for any sane man to swallow."

"A true scientist," said Hagg Nadeem, "weighs every fact with which he comes in contact before drawing a conclusion. If he is in search of truth, he can not afford to ignore a single fact, however absurd or illogical it may seem. In this case, you are basing your assumption on the hypothesis that it was a real haje you saw and handled, when what you actually saw may have been something entirely different, temporarily assuming the shape of a haje."

"That would be preposterous."

"Not necessarily. You are, I take it, familiar with the Lamia legends."

"Of course. A great English poem was based on them."

"I know. Lamia, by Keats. His picture of Lamia, the brightly colored female serpent that transforms herself into a beautiful girl, conforms to the ancient belief —or superstition, if you will —of the deadly, beautiful creatures called Lamias, half woman, half serpent, who visited men in their sleep, sometimes to make love to them, sometimes to drain them of their vitality, and often, in the end, to slay them, drinking their blood or devouring their flesh."

"A superstition undoubtedly evoked by the desire dreams of some ancient, lovelorn swains," said Tane.

"Not necessarily. It is recorded that one of these creatures once ruled all Libya. In fact, her name was Lamia, and that is why all such have subsequently been called 'Lamias'."

"I've heard of that, also," Tane told him. "It is said that, to this day, Greek mothers frighten their children into obedience by mentioning her name."

"Precisely. And it seems that a belief which has endured so persistently through the ages must have some foundation in fact. Perhaps there were, and are, such things as Lamias."

"At least the ancient scroll and crown I saw, if I really saw them, seem to confirm the fact that there was once a queen of Libya by that name, who claimed to be the daughter of a god and a royal princess."

"That is true." Hagg Nadeem snuffed his cigarette and stood up. "And it follows that since you read the scroll and unwrapped the serpent, you may have an opportunity to learn whether there was or is such a creature, and if so, whether she will live up to the promise made on the scroll, to become the slave of the man who awakens her. I will leave you, now, to a well-earned rest. Since I can not invite you up into my hareem, this will serve as your bedroom. Sleep as late as you like. The guards and servants will have orders not to disturb you. If you have need of anything, clap your hands. And I'll see you tomorrow. Just now, I have important work to do. Hadrak."

"Ma salam," Tane replied.

AS soon as his host disappeared through the doorway, the American went to the window and peered out. A sentry, with rifle and fixed bayonet, paced just below him. He went to the courtyard door and looked through the interstice between the curtains. Another guard stood there. A third door led into a narrow hallway, lighted by the yellow rays of a brass lamp. And seated at the end of the hall with every evidence of alertness was a third armed guard.

Returning to the diwan, Tane sat down. He decided that an attempt to escape would be foolish, futile, and dangerous. After all, where could he go to help his case in any way? To escape to the American consulate now would do him no good, even if it were possible of accomplishment. He would be traced and compelled to return to answer the murder charge, anyway. The diwan was most inviting, and he was very tired and exceedingly sleepy. With a yawn, he began to undress. A few moments later, clad only in his shorts, he blew out the light and settled down among the cushions and coverlets. Shortly thereafter, he fell asleep.

It seemed to Tane that he had scarcely closed his eyes in slumber, when he suddenly became wide awake. The moon had set, and the room was shrouded in that deceptive darkness which precedes the dawn, the various objects looming up as bulky shadows. He could see nothing amiss, yet he had an inexplicable premonition of danger —of some alien presence in the room. He held his breath and listened. A faint rustling sound came from the mashrabiyeh window, and he strained his eyes through the gloom to learn the cause. Suddenly he detected a movement, a wriggling sinuous motion through one section of the lattice. Good Heaven! It was a snake —a huge, mottled haje with scales that gleamed dully!

He strove to cry out, but could not make a sound. Then he tried to sit up, preparatory to running out the door and calling the guard, but found that he could not so much as move a finger. Such experiences had been his before, in dreams, but this, he was convinced, was no dream. The snake slithered down from the lattice and disappeared in the gloom beneath the window. The rustling sound now continued on the floor, and the fact that Tane could no longer see the reptile, made its approach immensely more terrifying. Again he made a desperate attempt to shout or move, but in vain. A cold sweat bedewed his forehead, and he was oppressed by a feeling of suffocation. The suspense of lying there, waiting for death to strike him from the shadows, was horrible, enervating. He almost wished the haje would sink its venomous fangs into his flesh and end it all. It was thus that the incomparable Cleopatra had found swift surcease from her troubles, ages before.

In breathless silence he waited for that hooded head to rear itself above the edge of the diwan. But instead of the serpent's head he was suddenly aware of something light-colored, and faintly luminous, moving upward from the floor. It was a pair of plumes —the two feathers of truth! They nodded above a diadem, fronted by a uraeus with glittering jeweled eyes. And beneath the diadem, there slowly materialized the face and form of the girl he had seen depicted on the lid of the mummy-case. She appeared to be draped in something white and filmy, which revealed every line of her slender, perfect figure.

"Who are you? What are you?" he tried to ask. But his voice would not function. He could not so much as whisper.

Although he could not hear his own voice, the figure seemed to hear it —or read his thoughts —for she answered him, her voice low and musical. And the language she used was that of ancient Egypt.

"Don't you know me, lord of my awakening? I am Lamia, once proud Queen of Libya, and now —your slave. I am still weak, for this is the first night, and so I can not serve you yet. But I will gain strength in the manner you and all adepts know, and then you may command my service and my power. You are in great danger, my master —such danger as will tax our combined efforts to thwart. I go now, to gain strength, but I will return and watch over you."

Slowly, soundlessly, she sank downward until only the nodding plumes showed above the rim of the diwan. Then these disappeared. Shortly thereafter there was a rustling sound at the window. He caught a flash of gleaming scales on a serpentine body that wriggled swiftly through the lattice-work.

For some time Tane lay there, listening. But the only sounds that came to his ears were the heavy tread of the sentry below the window, and the occasional matutinal crowing of the restless cocks of the neighborhood. Suddenly he discovered that he could move once more. He sat up, found his matches, and lighted the lamp. Its yellow rays shone to every corner of the room and revealed —nothing.

Sleep, he found, was impossible. He smoked cigarette after cigarette in a fruitless effort to soothe his jangled nerves. Presently, after what seemed ages of waiting, the dawn came. He blew out the lamp, settled down once more on the diwan, and presently fell into a troubled sleep.

TANE awoke and sat up, bathed in perspiration. He glanced at his watch. It was twelve o'clock, and the air quivered in the stifling noonday heat. Then a huge negro, who had been standing before one of the curtained doorways, said:

"I have drawn a cold bath for you, sidi. Will you step this way?"

"Will I!" Tane leaped to his feet, and followed the black giant through the doorway, down a hallway, and into a modern, tiled bathroom. A cold tub and a brisk rub-down made him feel like a new man. The negro brought him shaving things, and when he had finished, came in with his clothing, freshly pressed. As soon as he was dressed, the black man said:

"This way, sidi."

The servant conducted him back into the reception room. There he saw Hagg Nadeem seated on a diwan with a taboret before him.

"Salam aleykum" he greeted.

"Aleykum salam," replied Nadeem. "Will you breakfast with me? I, too, have just arisen."

"With pleasure, hagg."

The Egyptian clapped his hands, and a servant entered with a huge tray containing iced watermelon, eggs, toast, grilled fish, and a pot of spiced, sweetened coffee.

"Bismillah," said the hagg, piously, as he attacked his watermelon. "With health and appetite."

For some time they addressed themselves to their food in silence, after the oriental custom. Then, after they had rinsed their hands beneath a ewer brought by a servant, dried them, and lighted cigarettes, Nadeem said:

"I just received some good news for you from the kadi. It seems that Doctor Schneider appeared this morning and withdrew his accusation of murder against you. He said that he, too, had been drugged last evening, in addition to the blow on the head, but that now, since his faculties are clearer, he believes your story about the Persian."

"Drugged. So that's it. I wondered why he acted so queerly last evening. By the way, I had a curious experience after I retired. Sort of a vision, or dream. I seemed to be awake, and yet I couldn't make a move or a sound."

"Interesting. And what did you see?" Tane told him.

"Waha!" exclaimed the Egyptian. "And you call that a dream?"

"What do you mean?"

"At midnight, in the full of the moon, you read the mystic incantation aloud over the mummy-case of the ancient Queen of Libya, by the light of two magic candles. Then you opened the case and unwrapped the mummy. It is prophesied in the ancient writings that the man who does these things becomes Lamia's lord."

"Then you believe that what I thought I did and saw last night was real?"

"As real as this bit of candle wax, which is your only physical evidence. Yet small and insignificant as it is, it is enough to disprove the drug-dream theory, for such dreams do not materialize substance."

"That is true enough. Then you think I am—"

"Lord of the Lamia."

Tane looked at him in astonishment. "I can't believe it. I won't. It's all too incredible —too uncanny. Such things can't be."

"It may be that future developments will prove you wrong," said the hagg, solemnly. "We know nothing of the natures of these creatures called Lamias, or their powers or tenacity to life. Cold-blooded animals are notoriously difficult to kill, particularly serpents. There is an authentic record of a frog found alive in the wall of an old building, where it had been imprisoned without food or water for many years."

"But," said Tane, "assuming that a serpent did remain in a state of suspended animation for five thousand years, you still have the inexplicable phenomenon of that serpent changing to the semblance of a woman and returning to its original form, all in the course of a few moments."

"Even that," said Hagg Nadeem, "is not so difficult to believe as it might appear on first thought. I take it that you, like most scientists, hold to the theory of organic evolution."

"We use it as a working hypothesis," Tane replied. "Things happen as if it were true."

"Exactly. You believe that your ancestors in the dim and distant past were once reptiles."

"So it would appear."

"Even the science of embryology furnishes analogical proof of this. For, at one stage of its development, the human embryo resembles a young salamander."

"That is true."

"You will grant me, then, that the evolutionists believe a reptile gradually turned into a human being —say over a period of many millions of years. And the embryologists tell us that a reptilian form, under proper conditions, becomes a human form in the course of a few months."

"Of course."

"Then, effendi, I submit that there is but one difference between what your scientists tell us, and what you say you witnessed last night. That difference is 'time'. You saw, or appeared to see, a reptile become a human being. The evolutionists say this has happened. The embryologists say it still happens. Yet you did not believe the evidence of your senses because it happened so quickly."

"But," said Tane, "the girl appeared to change back to the serpent form once more."

"Why not? Combine two gases, oxygen and hydrogen, in the correct proportion, and under the proper conditions, and they become water. Treat the water with an electrical current, placing a receptacle over the anode and one over the cathode, and you reverse the process, for in the one you will find oxygen and in the other, hydrogen. The water has changed back to its original form. The time required for the change depends only on the dispatch with which the process is applied."

"You have offered analogical proof," said Tane, "but nothing more."

"Permit me to remind you," smiled Nadeem, "that your own scientists have offered nothing more than analogical proof for a biological theory which many of them believe religiously —the theory of evolution. However, time will reveal what is true and what is false. And in the meantime, let me warn you that your life is in grave danger. Here is the gun," handing him the forty-five, "which I took from you last evening. Keep it constantly within reach, and be ever on your guard."

"May I ask," queried Tane, "from whom or from what I am in danger? I have injured no one. Why should anyone wish to kill me?"

"You are Lord of the Lamia. Hence there are those who envy you and will try to supplant you. She will be your greatest protector, and will watch over you. But she is not invulnerable. I, too, shall watch, and do what I can. But you must help yourself. You have a saying: 'The Lord helps those who help themselves.' It will be wise for you to live up to it in this respect. I presume that you will want to get settled in your new home today, so I will not detain you longer. The doctor, I understand, moved out this morning. I will send a man with you to show you the way."

"I do have a devil of a lot to attend to —servants to hire, furnishings to buy, and all that. So, if you will excuse me, I'll be on my way."

Nadeem clapped his hands, and a short, dark-skinned fellah appeared.

"You will conduct Tane Effendi to his home, Mahmud," he ordered.

"Good-bye. Thanks for the hospitality —and the warning," said Tane, as he followed the servant out the door.

"Ma salam," replied Hagg Nadeem, smiling sweetly.

Tane found his servant, Ali, seated on the bench beside the door of his empty house, smoking his chibouk. He dismissed his guide with a coin, and entered, Ali at his heels.

"There have been many people here seeking employment, sidi," said the Syrian, when they reached the reception room. "Also there came merchants with rugs, mattresses, pipes, utensils and other household articles, having heard that you had moved in without furniture. But I told them all to return later."

Tane sat down wearily on the edge of the cushionless diwan, and lighted a cigarette.

"We'll just camp here for today," he said. "Tomorrow will be time enough to see about servants and begin buying the furniture. Just get a couple of mattresses, a rug apiece, some food, and such utensils and dishes as you will need to prepare and serve it." He rose and handed his servant five pounds. "Lock the door as you go out, so I won't be disturbed by peddlers and job-hunters."

After he had finished his cigarette, Tane decided to have another look at the mysterious niche which had baffled him so completely, and to explore those parts of the house which he had not previously seen. He accordingly went through the now curtainless doorway, into the room where his strange adventures had taken place. Divested of its rugs and furnishings it had a bare and forbidding look, and despite the brightness of the noonday sun, he had, on entering it, an eery feeling of impending danger —of some lurking, sinister presence.

An examination of the niche revealed the same thing he had last seen —the ancient brick wall flush against the panels as before. But from behind that wall there now came, faintly but unmistakably, a charnel odor that was suggestive of the presence of an unembalmed corpse. So disagreeable was this effluvium that he was glad to close the panels again, pausing only to re-examine the points above where the candles had stood. To his surprise, he now found no carbon there, though he distinctly remembered having previously soiled his finger with soot in examining it. But no matter what he had seen in that niche before, his olfactory nerves convinced him that a corpse was now entombed within it.

Passing thence into the hallway once more, he came to the bathroom. Here, everything loose had been removed, and the mirror door of the medicine cabinet stood open, revealing its emptiness. He was about to go on, when a flash of color attracted his eye —a bright bit of something red and gold, which lay on the tile floor. Bending, he picked it up. It was a piece of wood, gilded and lacquered, which had evidently been split off an ancient mummy-case.

After minutely examining it, he dropped it into his pocket. It was undoubtedly part of a mummy-case —perhaps the very case he had viewed the night before.

Returning to the hallway, he walked on toward the kitchen. But suddenly, just as he stepped through the doorway, the thick smothering folds of a burnoose were thrown over his head, two pairs of powerful arms pinioned his, and he was tripped and thrown to the floor.

TANE struggled fiercely but futilely in the clutches of his captors. They quickly found and removed his gun, and bound his wrists and ankles with ropes that bit painfully into the flesh. The cloak, which was strongly redolent of camel, was kept over his head. And with a knife pricking the flesh over his heart, one of his captors warned him that unless he kept silent he would be instantly slain. He was then rolled up in a rug, lifted to the shoulders of three men, and carried off.

He heard a door open, then guessed by the way he was being tilted, that his unknown captors were taking him down a stairway. He judged from their whispered conversation and the sounds of their footsteps that there were at least six of them. They walked on a level surface for some distance, then tilted him again, this time evidently carrying him up a stairway. Another door opened. A moment later, he was stowed away in what appeared to be a camel litter. A man seated in the litter with him pricked him with a knife and again warned him to be silent. Then he heard the cameleer alternately coaxing and cursing the beast, until it arose with many snorting, grunting protests. The litter gave a lurch, then settled down to a steady, swaying motion as the great beast started off.

At first Tane knew by the sounds about him that they were passing through the bazars, probably along the Sukten Nahhasi toward the Bab al Fotun, for he heard the mueddins calling the Faithful to the thur, or noon prayer, from the minarets of the many mosques clustered in this vicinity.

Some time later he heard a traveler inquire if this were the Bab al Hasaniyen, and a reply in the affirmative, which told him that he had passed out of Cairo and was probably on the Abbasiyeh Road. Where, he wondered, could his mysterious captors be taking him? And why? He had been a fool to allow himself to be caught thus off his guard. Hagg Nadeem had warned him. But who would have thought to find enemies hiding in his house? And how could they have gotten in with Ali guarding the door?

As he pondered these questions, he presently noticed that all road-sounds had ceased, and that the thudding of the camels' feet was muffled, as if with sand. Apparently, they had turned off the highway into the desert.

Tane's bonds, now perspiration-soaked, chafed and stung his wrists almost unbearably. And the stifling heat engendered a keen thirst that added to his torment. But the camel lurched on and on, hour after hour, until Tane's wrists and ankles grew numb and he sank into a half-smothered lethargy —a hideous nightmare of heat and thirst and torture.

Presently, when it seemed that he had reached the limit of his endurance, the endless swaying ceased, and Tane heard the cameleer's guttural "Ikh! Ikh!" as he commanded the beast to kneel. The animal lurched downward, grunted, and came to rest.

After Tane had been dragged from the litter and unrolled from the rug, the smothering cloak was removed from his head, and he saw his captors —six lean, dark-skinned, black-bearded Bedouins. One bent and unbound his ankles. Then two others caught him by the elbows, cruelly wrenching his bound wrists, and jerked him to his feet.

He swayed dizzily between the two kidnappers, and looked about him. They had halted at a small oasis, a shallow water-hole and a few palm trees, surrounded by the billowing sands of the Libyan Desert. Over beyond the water-hole a guard, silhouetted by the rays of the setting sun, leaned on a long rifle, watching a half-dozen camels. And near at hand a dozen of his fellows squatted about a campfire, smoking and chatting. Behind them was a large tent, the front wall of which had been raised to admit the evening breeze.

At this instant, the old man emerged from the tent. With a start, Tane recognized him as Shaykh Ibrahim, the darwish, who had conducted the funeral. With chin held high, he chanted the adan mughareb, the call to the sunset prayer. Instantly, all the ruffians except the camel guard and the two men who held Tane, rushed to the pool to make their wuddu ablutions. These finished, they faced Mecca, while the shaykh led them in prayer.

Prayers over, the old man rose from his rug, and, turning, entered the tent. Tane's two captors dragged him forward, and into the tent, at the back of which the old darwish was seated on a mattress, smoking the narghile from which he had weaned himself long enough to perform the pious office of imam. As the American was hauled up before the shaykh, the swarthy Bedouins crowded in behind him, and seated themselves on either side, along the tent walls. All glared at him with open hostility, and there were muttered imprecations of "Infidel! Christian!" and "Dog of a Frank!" Though his throat was parched and his tongue was so dry it rattled against the roof of his mouth, Tane knew better than to ask for a drink of water. These ruffians meant him no good; hence they would give him nothing either to eat or drink. For if they were to give either and then slay him they would violate their desert code —the law of the salt. He resolved to face it out boldly, asking nothing of them, and if need be, show these hard-bitten cutthroats than an American could die as bravely as any of them.

The old shaykh passed the flexible stem of his pipe to the man at his right, and squinted up at the tall young man standing before him.

"I have been informed that you are Lord of the Lamia," he said in Arabic. "Is this true?"

"And if I am, what then?" replied Tane, defiantly returning his gaze.