RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

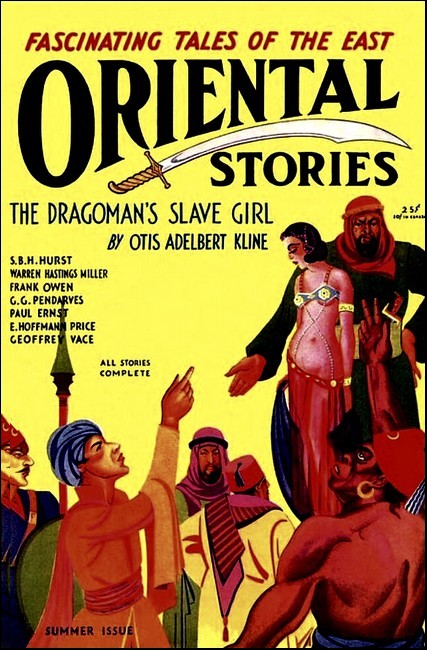

Oriental Stories, Summer 1931, with "The Dragoman's Slave Girl"

Otis Adelbert Kline wrote some half-dozen of these modern Arabian Nights tales, as told by white-haired Hamed the Dragoman, reminiscing of his youthful adventures when he was Hamed the Attar. One, "The Dragoman's Jest", was co-written with E. Hoffman Price, who died in 1988, and it is therefore still copyright.

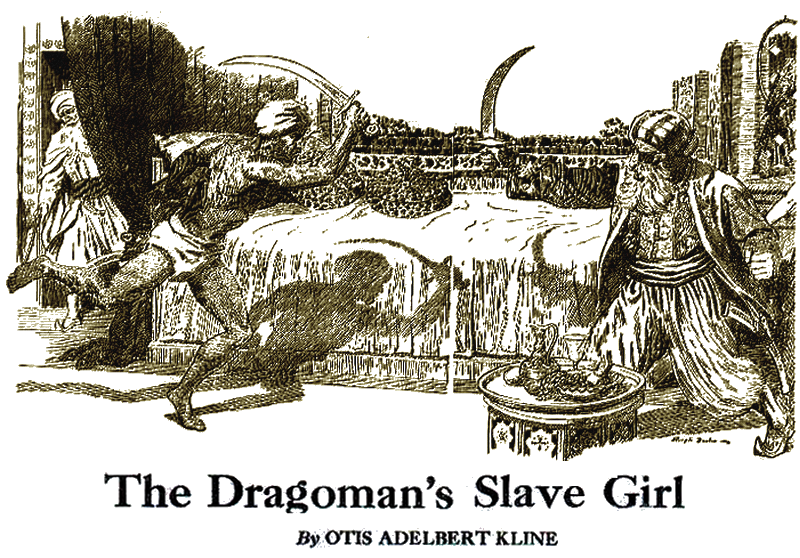

"With bared blade, I leaped at him."

A fascinating story of Hamed the Attar, which

has all the glamor of "The Arabian Nights."

IT is written, effendi, that there are roses of many kinds. They grow in many lands, and many are the gardeners. But there is only one beauty of the rose—of the white rose or the red, the pink rose or the yellow. That beauty comes from Allah Almighty, and when once we have seen and smelt one beautiful and exquisite rose, then indeed have we sampled that perfect bliss which awaits all true believers in Paradise.

Like a flower from the very Gardens of the Blessed was Selma, Rose of Mosul. When the great Weaver of Destinies crossed the threads of her life and mine, we were plunged together into a strange and wondrous adventure which came near to severing both, yet for a time they were entwined, each with the other. Then, indeed, did I sample that bliss which is reserved for the faithful in the Gardens of Allah.

You would hear the story? Tale-telling, effendi, parches the throat. Yet if you would listen, here is the coffee shop of Silat, who brews the best ahhwi helwh to be found in the Holy City, and who learned his art from the great Hashim, father of coffee brewers in no less a place than Estambul.

Here we have both comfort and privacy. Ho, Silat! Two narghiles, scented with your best rose attar and packed with golden Suryani leaf. And brew for us coffee, bitter as love's first estrangement, black as the throne of Shaitan the Damned, and hot as the molten lava that boils in the innermost lake of Laza. Give ear, effendi, and I will unfold for you this wondrous adventure which befell me in the days of my youth.

Looking upon this bent and aged form and this white beard, you can scarce picture Hamed the Dragoman of those days. For then I was straight and strong as a young cedar of Lebanon, with hair of midnight blackness and features that were not accounted unhandsome. Nor feared I man nor jinni. I have related to you, effendi, my adventure with Mariam, Oracle of Ishtar, which left me with an empty heart and the opulence of a merchant prince. Hoping to find solace and forgetfulness in the curious scenes which other lands might afford, I decided to travel and see the world. I accordingly converted my wealth into gold and set out.

FOR more than a year I wandered, visiting the great cities of far Cathay and distant Hind, and spending with prodigal abandon. But there came a bleak dawn when I awoke in Singapore after a night spent in drinking the fiery liquors of the Ferringeh and watching the contortions of brown-skinned nautch girls. I found myself with a head that seemed as big as the Taj Mahal, and a purse that had shrunk alarmingly. I accordingly abandoned my intention to travel home overland, and took ship for Basra. From there I journeyed up the Tigris to Bagdad, and thence to Mosul.

Having crossed the stone bridge and the bridge of boats, I spent the morning wandering among the ruins of the buried city of Nineveh. Then I visited the grave of Jonah, on whom be peace, who was once rescued from the belly of a fish by Almighty Allah.

After I had viewed these wonders, I went to pray in the Great Mosque at the call of the muezzin. Then, being hot and thirsty, I sought an airy coffee booth overlooking the souk.

My former great fortune, I found, had been reduced to a mere hundred dinars. It would be difficult to find employment as a dragoman, nor would it be lucrative, as few travelers of wealth were visiting the city at that time because of the oppressions and indignities heaped upon them by the new Governor, Mohammed Pasha, known as Keritli Oglu, the Cretan's son, whose cruel misdeeds had made him notorious throughout all Islam. Indeed it seemed to me that there were at least two dragomans for every traveler. I had once been an attar, however, and with a hundred dinars might open a small drug and perfume shop, and at least manage to exist. This I resolved to do.

As I sat there sipping my coffee, puffing at my shisha, and gazing abstractedly across the market square, I noticed that a great number of people were entering the stall of a rug merchant opposite me, but though more went in than the stall could possibly have held, none came out.

Puzzled, I paid my host, and crossing the square, was surprised to see the place evidently deserted. But a tall, night-black Nubian eunuch had gone in just as I came up, and in a moment I heard a voice say:

"You have the word?"

"Ayewah."

"Give it me."

"Zemzem."

"Enter." There was the sound of a latch, footsteps, and a door opening and closing. Then the merchant stepped from behind one of the rugs hanging in the back of the booth.

"Salam alek'," he greeted.

"Was salam," I replied, stepping into the stall. He drew the rug aside, and I went on into a tiny back room.

"You have the word?" he asked me.

"Ayewah,"' I replied, remembering what I had heard. "Give it me."

"Zemzem."

He pulled a tasseled cord, whereupon a curtain drew back disclosing a concealed door. Then a latch clicked, and the door swung open.

As soon as I stepped through that door I saw that I was in a slave mart. It seems that the British, the French and the Russians, all of whom had consulates in Mosul, frowned on the slave traffic. But so long as it was conducted behind locked doors through which none might enter without the secret word, it was impossible for them to take official cognizance of it.

I found myself in a walled enclosure, nearly filled with prospective buyers. They faced a great, flat-nosed, red-bearded fellow standing on an auction block, behind which was a door that opened in a small building at the far end of the lot.

FOR some time I stood there idly looking on, while he auctioned off girls and women, tall and short, young and old, fat and thin, willing and unwilling. There were slant-eyed, golden-skinned girls from Cathay, supple, brown-skinned nautch-girls from Hind, Nubian maids and matrons whose bodies were like polished ebony, and Abyssinians of the color of coffee. Then came the Circassians, Armenians, Persians, Nestorians and Yezidees, some quite good to look upon, and others distinctly ugly. But none interested me.

I turned to go, when suddenly I heard a chorus of "Oh's!" and "Ah's!" from the entire assembly.

Looking back toward the auction block, I was smitten with admiration for the witching vision of feminine loveliness that stood thereon. Then, scarcely knowing what impelled me to do so, I elbowed and jostled my way to a position just in front of the platform and stood there like the others, gaping up at the wondrous frail creature who, standing there beside her auctioneer, was as a gazelle beside an overgrown wart-hog.

Nor had Almighty Allah ever before vouchsafed me the privilege of beholding such grace and beauty. Her eyes were large and brown, and their sleepy lids and lashes were kohled with Babylonian witchery. Her mouth was like the red seal of Suleiman Baalshem, Lord of the Name, on whom be peace, and her smile revealed teeth that were matched pearls. The rondure of her firm young breasts, strutting from her white bosom beneath the glittering, beaded shields, was as that of twin pomegranates. And her slender waist swayed with the grace of a branchlet of basil, above her rounded hips.

The flat-nosed auctioneer stooped for a moment for a few words with a well-dressed dignified graybeard who was evidently the owner of the little beauty. Then he straightened, and after clumsily describing the charms of her whose beauty defied description, stated that her master had stipulated that she should not be sold to any one against her will, but that if sold at all she would be accorded the right to choose who would be her new master from among those who would bid for her. Then he called for bids.

With but a hundred dinars in my purse, I knew it was useless for me to bid, for this girl would undoubtedly bring thousands. Yet so smitten was I with her loveliness that had I, at that moment, the vast wealth of Haroun al Rashid, I would gladly have bidden it all.

Over at my left a voice bid fifty dinars. I saw it was the huge black eunuch who had preceded me into the mart. It was a ridiculously low offer for the little beauty, whose rich clothing and jewels alone were worth twenty times the amount. But to my surprise not another voice was raised to increase it.

The girl glanced out over the sea of faces expectantly. Then her eyes found mine—clung for a moment—and in them was a look of appeal.

"Sixty dinars," I said.

A beetle-browed camel-driver who stood next me, nudged me with his elbow. "Bid no more if you value your life, O stranger," he said. "You are competing with the eunuch of Mohammed Pasha."

Glancing about, I saw that several others were staring at me as if astounded at my temerity.

"Seventy dinars," said the eunuch, scowling at me.

Then I felt the point of a dagger against my ribs. "Raise the bid, O dog of a Badawi," a voice grated in my ear, "and you die."

Again those lustrous brown eyes looked at me with a world of appeal in their glance.

Suddenly I seized the wrist that held the dagger, swung it around in front of me, and twisted. The weapon clattered to the pavement, and I was glaring into the eyes of a villainous-looking Turk with a red tarbush and bag trousers. He grabbed for the dagger with his free hand, but I stepped on his fingers, so that he howled with pain.

Then I flung him from me, along the length of the platform. He fell at the feet of the Nubian eunuch as I bid: "Eighty dinars."

Half turning, I saw several more red tarbushes moving toward me through the packed crowd, and once I caught the glint of naked steel. I elbowed my way around the side of the platform so that I stood near the old man who seemed to be the girl's owner, with my back against the wall. Then I loosed my scimitar in the scabbard.

The eunuch, who had evidently been waiting for the Turks to reach me, bid:

"Ninety dinars."

I whipped out my scimitar and the tarbushes paused. A jambiyah hissed past my ear, snapping its point on the wall behind me before it clanked to the flag-stones. The Nubian frowned fiercely, rolling his eyes in my direction so that the whites gleamed against the black of his ebony skin. I turned to the old man who was the girl's master.

"I have but a hundred dinars," I whispered.

"Then bid, in the name of Allah, and save her from worse than death," he replied. "Remember, the girl will choose her master."

"One hundred dinars," I shouted, and the Turks moved closer, while blades gleamed menacingly, hemming me in.

"One hundred fifty dinars," roared the eunuch.

"I would bid more, but I have it not," I called up to the auctioneer. There was a look of triumph in the eyes of the Nubian. The ring of tarbushes around me began to move away. The auctioneer shouted to the crowd, enumerating the charms of the girl, which were plain to any but a blind man.

"Two hundred dinars," he cried.

"Who will pay two hundred dinars for this houri from Paradise? Why, her clothes, alone, are worth a thousand. One hundred seventy-five. Who bids one hundred seventy-five? Well then, sold to Mansur, chief eunuch of His Excellency, the Pasha, for—"

"One moment." The girl interrupted him with a voice as sweet and clear as the tinkle of a silver bell. "It was stipulated that I might choose my own master. I choose the young Badawi who has bidden his all—one hundred dinars."

"But you cannot choose this pauper when His Excellency's servant has bid—"

"I choose the Badawi," persisted the girl.

"I will pay you baksheesh on the hundred and fifty," said the old man, sotto voce. "Make the sale quickly!"

"Sold to the young Badawi for one hundred dinars," shouted Flat-Nose hurriedly, mindful of his extra commission.

While the girl was stepping down from the platform I tossed my purse to the graybeard, who promptly handed fifteen dinars to the auctioneer. The tarbushes were closing in again, and there was no mistaking their purpose. The girl came up beside me. She had resumed her black street garments and donned her yashmak, over which her frightened eyes looked up at me.

"Master, we must get to the street quickly," she said, "for if the eunuch gives the word you will be cut down without mercy. I know a way through the house behind us. Follow me."

But she had scarcely finished speaking ere the Nubian shouted, and a half-dozen of the Pasha's cut-throats, who had only been awaiting the word, sprang at me with bared blades.

AS the first of the Pasha's ruffians assailed me, I whipped out my scimitar and made as if I would lay his head open. But when he raised his blade to parry, I changed the direction of my stroke, and dealt him a leg-cut that laid him low. To my surprise, the graybeard to whom I had handed my purse drew his scimitar and came on guard beside me as the others rushed up.

With the girl behind us, we slowly backed toward the doorway, the old fellow at my side cutting and parrying with a skill that amazed me. The crowd was in an uproar that all but drowned the noise of our clashing blades. Taunts and insults were hurled by the bolder of the onlookers at the Pasha's eunuch and his soldiery.

Then suddenly, a tall Badawin sheik leaped to the platform, and with a push sent the flat-nose plunging into the crowd that milled below.

"I bear witness," he roared in a voice that thundered above the tumult, "that this is foul injustice. How long, O men of Mosul, will we stand idly by to see true believers robbed and murdered by the Pasha and his wolves?"

For a moment all voices were stilled.

Then there were cries of: "Down with the Pasha!" "Down with the Cretan's son and his wolves!"

Blades were drawn and brandished, and the mob which had stood idly by for the sole reason that it lacked a leader, was now ready to fly at our attackers. Seeing the way things were going, Mansur the eunuch quickly called off his scoundrels, who picked up the man I had wounded and laying him at the feet of the castrado formed a semicircle in front of him.

But now the leader who had come so suddenly to our rescue, again demonstrated his ability to sway the mob, which, numbering well over a hundred, was ready to make short work of our persecutors. Flinging his hands aloft, he cried:

"Hold! Enough! We seek justice, nothing more."

Then, as the mob paused, he turned to the eunuch:

"I have a question to propound, O Mansur," he said. "Tell me, was this damsel lawfully purchased by the young Badawi, or was she not?"

"She was not, O Tafas," growled the eunuch. "He bid but a hundred dinars, while—"

The Arab interrupted him:

"It was stipulated that she might choose her master, and she has done so. All is fair and according to law. However, it seems that you are like a walnut—must be cracked in order to be of use. Ho, men of Islam." A menacing roar from the crowd drowned his voice for a moment.

Seeing the way things were going, and realizing the peril in which he stood, Mansur quickly changed his tone. "It may be that the sale was lawful," he admitted.

"You will bear witness?" asked Tafas.

"I bear witness that the sale was lawful," said the thoroughly cowed eunuch.

The Arab turned to where we stood—the old man, the girl, and I.

"Depart in peace," he said.

"May Allah requite you," I replied, and we turned and walked through the doorway, down a long, dimly lighted hallway, and into the street beyond. Here we all paused, I in considerable bewilderment.

"Lead on to your house quickly, Master," said the girl. "I will follow."

"But I have no house," I replied. "I am a stranger, sojourning in Mosul."

"You have a tent, then? A camel or a horse? Take me away swiftly, I beg of you."

"No tent, nor horse, nor camel have I. Nothing but my weapons and the clothes on my back."

"In that case," said the old man, "I invite you to my poor habitation. We must get off the street as soon as possible, for I am convinced we have not heard the last of this affair from the Pasha. Let us make haste."

WE set off down the street, the girl following behind as is customary for slaves.

"By what name may I be permitted to call you," said the old man courteously, as we hurried along.

"I am Hamed bin Ayyub, late of Jerusalem," I replied, "where men once knew me as Hamed the Attar. Having lost my fortune through a scheming woman, I became a dragoman. Then, having won another fortune through a woman of quite a different sort, I became a traveler. You have witnessed the spending of the last of my latest fortune."

"My own fortune is in like case with yours," said the old fellow. "I am Hasan Aga, once the most opulent and powerful of the agas of Mosul. The girl you have just purchased is my niece, Selma Hanoum."'

"Then you, an aga, have sold your niece into slavery."

"Necessity compelled it," he said. "She is a great lady, and was wealthy in her own right until Mohammed Pasha came to Mosul. Her father, who married my sister, may Allah grant them both peace, was a pasha, and she his only child. He left to her the finest house in Mosul with its palatial furnishings, slaves, and the wealth to maintain it. But Mohammed the plunderer quickly found a way to dispossess her by unjust levies, and by lawsuits with perjured witnesses, brought before the dishonest kazi.

"Not satisfied with acquiring her property, her slaves and her wealth, the Pasha, having heard of her great beauty, attempted to force her into his harim, With her sole remaining slave, a faithful Maghrebi eunuch named Musa, she fled to my house for protection. Whereupon, the Pasha, who had already deprived four of our leading agas of everything they possessed, including their heads, began his persecutions of me. Today, I was left only in possession of my house, my head and my niece, and certain that it would not be long before I should lose all three. At first I had concealed much of my wealth and that of my niece, but this I was forced to bring forth to save my head and to protect her. Four days ago I spent my last para for food. Destitute and starving, we could turn to no one for help, as nobody could offer us succor for fear of incurring the Pasha's wrath. And so terrorized were the merchants by the Pasha's wolves that they would not purchase the jewels and ornaments of Selma Hanoum, though I offered them at a small fraction of their worth.

"This morning, my niece, as a last resort, besought me to take her to the slave mart and sell her, making the stipulation that she should choose her own master. But the Pasha's spies must have followed us, and informed their master, who sent his eunuch and his ruffians to frustrate her plan for escaping his clutches. Knowing that many of the desert Badawin would be there, she planned to choose one as her master, hoping thus to get away from Mosul. Some weeks ago I sent a messenger to her cousin and my nephew, Ismail Pasha, in Estambul, requesting aid. As soon as help arrived, it was my intention to repurchase the daughter of my sister from the Badawi who would buy her."

"It is unfortunate that she chose a Badawi without wealth or followers," I said. "I have nothing but my blade and blood to give in her service."

"Women were ever wont to employ the heart rather than the head in such matters," he replied. "But here is my house. Bismillah. In the name of Allah, enter."

A Maghrebi castrado of about my own size and build admitted us.

"This is Musa, the slave of Selma Hanoum," said Hasan. "Musa, this is your mistress' master."

I exchanged taslims with the slave of my slave-girl, and we went into the magnificent majlis, now all but denuded of furnishings. The eunuch brought us water for washing our hands, and prepared pipes for us. Selma Hanoum had retired to the women's quarters, but returned presently, clad in filmy harem garments that covered, yet revealed, every curve of her perfect figure, and wearing a light face veil.

While we three discussed the perilous situation in which we found ourselves, Musa went to the souk for food and coffee. He returned presently, and Selma prepared a meal for us that would have broadened the breast of a sultan. We regaled ourselves with deliciously grilled mutton, dolmas, leban, and an excellent pilav, after which came fruits, nuts and sweetmeats.

Then, with pipes going, we made merry over our coffee and 'raki despite our dangerous predicament. But our merriment was cut short by a thunderous knocking at the door. Musa answered, and returned carrying a basket which he set on the floor before his mistress. "A gift for Selma Hanoum with the compliments of the Pasha," he said. "Open it," she directed.

He raised the lid, took out a napkin, then gasped in horrified amazement. One look into that basket, and Selma drew back with a choking cry.

Wondering what gift could have so fearful an effect, I peered into the basket.

The sightless, glassy eyes of an Arab stared up at me from a severed and gory head. I recognized the drawn features of Tafas, the Badawi who had championed our cause in the slave mart!

NATURALLY the grisly gift of the Pasha threw us into a panic. But strangely enough, the girl was the coolest of us all.

"It is written on our foreheads," said Hasan to me, "that we are not long for this world. I doubt if we two will see the light of another day. Following this warning will come the soldiers. We will be dragged before the Pasha. There will be perjured witnesses to swear to such charges as may have been trumped up against us. Then—the swift stroke of the headsman, and the daughter of my sister will be at the tyrant's mercy."

"I, for one, do not intend to submit tamely," I replied. "When the soldiers come, I will fight."

"And I," agreed Hasan. "In our passing, we can thus take at least a few of the wolves with us."

"Valiant words, Master and Uncle," said Selma, "but how futile to rush into the jaws of death when, with a little planning, you may both live."

"A little planning? How?" asked Hasan, with the air of a drowning man clutching at a straw.

"There is the souterrain—the passageway which connects my house and yours."

"One can not exist for long in the souterrain without food and water," said Hasan. "Besides, if Hamed and I were to enter it, what would there be to prevent your being carried off by the Pasha?"

"Nothing," she replied, "nor would there be, were you to foolishly, if bravely, die fighting his soldiers."

She turned to me.

"Master," she said, "the house in which the Pasha lives is rightly mine. In the days when my father was governor of this pashalik, he dug an underground passageway leading from a secret panel in his Harim to another secret panel in the harim of this house, which he also owned. He believed in being prepared for troublesome times, which are not uncommon hereabouts. More than one pasha has been murdered in his own house, so he planned this secret means of escape. In this house he established my uncle, who was apprised of the secret of the passageway.

"All this was done before I was born, yet before he died, my father told me of it, and showed me how to open the panel in his arim, and to travel through to this one. It has never been used, and to this day none knows of it but my uncle and I."

"And you would have me hide in a souterrain while you are carried off to the harim of the tyrant?" I asked. "No. I would rather—"

"But, Master, remember the souterrain connects with the Pasha's harim. Once inside, I can find a way to get food and drink to you and my uncle. Then we can plan our escape. I have already thought of a disguise for you. Come into the harim and I will apply it now, as we may not have the opportunity later."

She took my hand and led me into the harim. Then she bade me remove my upper garments and my slippers. While I was doing this she brought a bottle of brown liquid and a cloth.

"You and Musa are of one size and build," she said, "and were it not for his dark skin you might almost be twins. This is some walnut juice which I prepared some time ago, intending to use it myself in an attempt to escape. Now it would be useless to apply it, for any woman leaving this house would be seized. But if I disguise you as Musa, and arrange another disguise for my uncle, we may yet all find the means to escape."

I did not like the idea of even pretending to be a castrado, but despite my protests she began applying the walnut juice to my face with the cloth. After that it was useless to protest. When my face, neck and ears were thoroughly stained, she skilfully colored my trunk, arms and hands, spreading the stain so evenly that I looked to be in very truth the Moor I was to pretend to be.

While she was staining my feet and legs, I said: "In applying this color to me, O fairest Rose of Mosul, you only make me look like that which I really am."

"You mean," she said, with manifest consternation, "that you are really a eunuch?"

"Not that," I replied laughingly. "I mean that I am really your slave. From the moment I saw you on the auction block, I have been your love-slave."

A telltale and most becoming flush mounted to her temples above the yashmak, but she only said, with a last dab at my thigh:

"There. That is as far as I may go. Musa will finish, and will furnish you with a suit of his raiment."

She clapped her hands to summon the castrado. When he arrived she gave him his instructions and rejoined her uncle in the majlis. A short time thereafter, without a white spot left on my body, and attired in garments like those worn by Musa, I returned to the majlis with the eunuch.

"By my head and beard!" exclaimed Hasan. "This is a wondrous transformation. It seems that Musa has suddenly become twins."

But Selma was not satisfied. She called for the walnut juice and standing on tiptoes, applied deft touches here and there to my swarthy countenance. I thrilled with the nearness of her, and could scarce refrain from crushing her in my arms.

But she finished in a moment, and returned bottle and cloth to the eunuch, who took them away to conceal them with my clothing and weapons. The latter he had replaced with a huge, harim guard's simitar and a jewel-hilted jambiyah thrust in my sash.

WE three sat down to our coffee and pipes once more, and a few libations of 'raki soon set us to chattering merrily. Musa, meanwhile, carried food and water into the souterrain.

Our merriment was short-lived, for there came a second summons at the door, more loud and threatening than the first.

"They have come!" cried Selma. "Into the souterrain with you, quickly!"

She hastily donned her street attire.

"Go, Hasan! Take Musa with you," I said. "I'll answer the door."

"But Musa is to remain with me," said the girl. "I am Musa," I told her. "I remain with you, and where you go, I will go."

"But you can not. They will detect and kill you."

"I remain," I persisted, giving the frightened Hasan a push toward the harim door.

Bewildered, and muttering pious ejaculations in his beard, he fled. A moment later I heard him exchange a few words with Musa. Then the panel clicked, and they were gone. The pounding on the door was by now so fierce that it threatened to fly from its hinges. Selma watched me with terror-stricken eyes as I went to the door and called:

"Who is it?"

"Daoud Aga, with soldiers. Open in the name of His Excellency, the Pasha," was the reply.

I slid the bar, flung the door wide, and stood with folded arms in the manner of a slave. Simitar in hand, a young and self-important aga brushed past me, followed by a dozen soldiers with muskets. Daoud Aga was the highest ranking military officer in the pashalik, the Yuz-bashi, or Captain of the Irregulars, and he took no small pride in the fact. Striding up to where Selma Hanoum sat, he demanded: "Where is the dog of a Badawi who had the temerity to cut down one of my men?"

"I know of no such Badawi, replied Selma, demurely.

"Where is your master—the man who bought you this morning?"

"Oh, my master! He has gone to the souk to buy tobacco."

"So! And where is your uncle, Hasan Aga?"

"Why, my uncle went with him."

"Lies! This place has been watched continually. None but your eunuch went forth and returned. Search the house, men."

"Search if you will, but you will find no one here save my eunuch and me." They searched the place thoroughly, but of course found no one.

"Once more," said Daoud Aga, "I give you the opportunity to tell me the whereabouts of your master and your uncle. If you will not answer me, then must you answer the Pasha."

"I can tell you no more," replied Selma.

"Very well. Then come with me."' He turned to his men.

"Bismillah!" he cried, with a wave of his hands. "Eat, in the name of Allah!" The men responded with alacrity, and "ate" to their hearts' content, though with some quarreling among themselves, for this simply meant "to plunder."

From the Pasha down, the entire governmental organization was a band of legalized freebooters, and it was said that only by permitting his men to "eat" on such occasions as this did Daoud Aga hold them together.

The loot must have been quite disappointing to them. The Pasha, by means of levies and false claims, had long since annexed nearly everything of value, and Hasan had sold most of what remained, in order to buy food.

Selma rose, and obediently followed the aga, while I, whom she had followed as master only a short while before, now followed her down that same street as her slave.

Despite the perilous situation in which I found myself, I derived some small amusement from the idea of being the slave of my slave.

IT was only a short walk to the Pasha's house. Not more than six doors separated the two places. Yet, I reflected, considerable labor was required for the digging of a souterrain for even this distance. We were ushered into the salamlik, where the Pasha sat, cross-legged on a diwan, smoking and talking to a half-dozen of his satellites.

He proved as ugly in appearance as in reputation. His Excellency had but one eye. One ear had been torn off. He was short and of immense girth, and his features were deeply marked with smallpox pits. His gestures and mannerisms were as uncouth as his features, and his voice was harsh and strident.

With a wave of his hand, he dismissed his hangers-on as we entered. Squinting up at Daoud Aga with his single good eye, he rasped:

"Well, captain?"

"I have brought Selma Hanoum into thy presence, in accordance with Your Excellency's commands."

"So? And where are the others? The traitorous aga, her uncle, and the murderous young Badawi who wounded one of my men this morning?"

"I could not find them, Excellency, and she refused to reveal their whereabouts; so I informed her she must answer to you."

The Pasha leered up at the slight cloaked and veiled form standing beside the captain.

"Where are your uncle and your master?" he demanded.

"If I knew I would not tell you," she replied.

"What? You defy me, the Pasha?" He clapped his hands, and Mansur, the huge Nubian eunuch, came through a doorway at his left.

"Take this lady into the harim, Mansur," he said, "and prepare a room for her. She must be detained, and it will be more comfortable there than in the jail."

"Harkening and obedience, Excellency," responded the eunuch, and led her through the doorway.

The Pasha squinted up at me, then turned to the captain.

"Who is this fellow?" he asked.

"Musa the eunuch, slave of Selma Hanoum," replied Daoud Aga.

His Excellency smirked. "Well come and welcome," he said. "I have use for you."

"I kiss the dust at your feet, O dispenser of justice and fountain of wisdom," I replied, with as much slavish humility as I could muster.

Once more he clapped his hands, and Mansur reappeared: "Let this castrado be bowad of the rear door," he said, "and guard of the women's sleeping-quatrters."

"I hear and obey, Excellency," responded Mansur. Then he beckoned to me, and I followed him through the doorway.

MANSUR led me through the majlis and up a stairway to a narrow balcony which fronted the women's quarters. Here a short, fat Nubian castrado whose shiny black torso was padded with rolls of flabby fat, stood guard.

"This is Sa'id, Bowab of the bab al harim," said Mansur, to me, and to the fat one, he said: "This one is Musa, slave of Selma Hanoum, who will guard the rear door and the sleeping-quarters."

I exchanged taslims with the greasy Sa'id, and was conducted into the harim. In the front was a roomy and magnificently furnished apartment. Here were more than a score of women and girls, some merely lolling, some smoking and chatting, some busy at needlework which no whit interfered with the clatter of their tongues, and the rest plying hair-tweezers and cosmetics in their efforts to improve on the handiwork of nature.

I was somewhat abashed at this sudden sight of so many unveiled and lightly clad females—no Moslemah deeming it necessary to hide her charms in the presence of a eunuch, who is not considered a man—and found it difficult to maintain an imperturbable countenance as Mansur led me through the room. Moreover, they were all staring at me and commenting on my appearance as if I were some new bit of furniture of doubtful value added to the Aarim by the Pasha.

The Lady Selma I saw, unveiled like the others, seated near a window with one slave-girl brushing her lustrous tresses and another staining her dainty toenails with henna, both working under the direction of a wrinkled hag. These attentions, I knew full well, meant that His Excellency was expected to call on the damsel that evening.

My blood boiled at the thought, and unconsciously my hand stole to the hilt of my simitar. Though there were many girls of considerable beauty in the room, Selma's loveliness outshone them all. She was a lone, budding rose in a weed-choked garden.

Mansur led me down a long hallway on which opened the doors of the women's sleeping-apartments, each wife and favorite concubine having a room to herself. At the end of the hallway a larger door led to a balcony which overhung that part of the garden reserved for the inmates of the harim. The balcony was screened with lattice work so that those standing thereon could see without being seen. An enclosed stairway led down into the walled garden.

A portly eunuch acted as bowab of the garden gate.

Mansur called him and introduced us. He was Sa'ud, twin brother of Sa'id, bowab of the bab al harim, and as like him as is one rice grain to another. Sa'ud went back to his post, and the chief eunuch gave me my instructions. I was to stand guard at the rear door of the harim, and to patrol the hall at regular intervals. At night I would sleep on a diwan beside the rear door, keeping my simitar always by me.

I remained at the door until some time after Mansur had left. Then I sauntered down the corridor and looked for a moment into the women's majlis. The two slaves were still busy with Selma Hanoum, under the directions of the old trot, trying to improve on the beauty of a rose which Allah Almighty had made perfect.

As I turned and sauntered back along the hallway, I knew that I was drowned in a sea without bottom or shore—head over heels in love. Returning to my post, I seated myself on the diwan beside the door, and was lost in a maze of lover's dreams when there came to my ears the soft tones of a lute, then the sweet voice of a female singer.

As I mooned there by the door, the words of her love song suited my mood:

"Thou hast made me ill,

O my beloved!

And my desire is for nothing but thy medicine.

Perhaps, O fairest flower, thou wilt have mercy upon me,

For verily my heart loveth thee.

O thou blushing rose! O thou perfect rose!

Heal my bleeding heart with the perfume of thy presence."

ALTHOUGH it was not time for me to patrol the corridor again, I rose, and walked to the door of the majlis to see who was the singer. Seated on a cushion near the door holding the lute, was a Maghrebi dancing-girl with slender waist, full, round breasts and exquisitely formed limbs. She was darker than Selma Hanoum, with hair that was black and lustrous, and eyes whose smoldering glances could kindle the flame of desire like a firebrand tossed among dry reeds. She turned those orbs on me while the other inmates of the harim cried their approval.

"Well done, O Fitnah! Allah approve you! Allah preserve your voice!"

"And do you like my song, O chamberlain?" she asked me, when the clamor of the others had subsided.

For a moment I was too astonished for speech at being thus addressed. But I recovered my voice, and said: "Does a starving man dislike food, or a thirst-parched desert traveler turn away at the sight of water? If these things be true then I can not abide your music. But if they be not true, then do I hunger and thirst after it."

The girl laughed, a low musical laugh. Looking at Selma, she said: "Your slave has a gifted tongue. From what country came he, and what is his name?"

"He is from El Mogrheb," replied Selma, "and his name is Musa."

"Ah, from my own country!" said the girl. "I surmised as much. From what city, Musa?"

I thought fast, and remembering the name of a Moroccan city, replied: "From Marrakesh."

"Why, this is amazing!" said Fitnah. "It was in that city I was born and reared. You remember the street of so and so that passed by the mosque of such and such?"

"Assuredly," I replied, though I had never heard, nor can I even now remember the names she mentioned, "as I went dow that street every Friday to worship at that very mosque."

"Marvel of marvels!" she exclaimed. "And to think that was the very street on which I lived! It may even be that we are cousins. You must tell me of your family and tribe some time. But now I will sing for you in memory of Marrakesh, that pearl among cities, which was your home and mine."

She sang again, stroking the lute softly and flashing at me from time to time such seductive glances that despite my love for Selma I was stirred by her witchery. Nor did her eyes look solely into mine, but swept over me appraisingly from head to foot, making me uncomfortably conscious of my bare limbs, naked torso and scant loin-cloth. When she finished I applauded and returned to my diwan.

This dancer, it seemed to me, had been well named. For "Fitnah" has several meanings, among which are: "beautiful girl," "seduction," and "aphrodisiac perfume." She was certainly a combination of all three—a lodestone to draw men's desires, well knowing how to shape them to suit her own ends. Such women are dangerous.

A NARGHILE stood beside my diwan, with tobacco and charcoal. I lighted it, and was puffing reflectively, meditating on the singular circumstances in which I found myself, when I heard the tinkle of anklets in the corridor.

Looking up, | saw Fitnah, carrying her lute. She did not so much as glance in my direction, but raised a curtain and entered a near-by doorway. A moment later, however, she peered out at me, and softly called:

"Musa."

"What is it?" I asked.

"I have need of your strength. My diwan is heavy, and I would have it nearer the window. Will you help me move it?"'

"Assuredly," I responded, and went into her apartment. To my surprise, I saw that her diwan was directly beneath the window.

She noticed my puzzled look, and smiled. "Certainly," she said, "you are not as dense as you pretend to be." Then she came up to me, swaying her shapely hips in the wanton manner of the gazeeyeh dancing-girls of the bazars, and before I knew what she was about, had flung her arms about my neck, pressing her shapely body close to mine.

I tried to draw away, but she clung the tighter, charming me with her smoldering eyes—fanning the flames of my desire. She was intoxicating! Overpowering! Maddening! Slowly our lips met, and clung. Rivers of fire coursed through my veins as I tried to shake off the spell of her accursed witchery. Again I tried to push her away, repeating the formula:

"I seek refuge with Allah from Shaitan, the Stoned!"

But she only smiled up at me, stroking my face and murmuring:

"Musa, I love you."

Suddenly the door-curtain was drawn back and a slender figure stepped into the room. It was Selma. Surprised, she looked at us for a moment, then said: "I am sorry to intrude, Fitnah. I thought you were alone."

I was too astonished and mortified to speak. And Fitnah did not. In a moment, Selma was gone. Resolutely, now, I tore the temptress' arms from around my neck—pushed her away. She flung back her head, hands on hips, eyes blazing. It seemed that she could be, at will, a cooing dove or a tigress.

"So," she said, "you do not relish the caresses of your little Moroccan cousin when Selma Hanoum is near. It may be, after all, that I shall report you to the Pasha. What are you doing in this harim masquerading as a Maghrebi eunuch? I knew you were no Maghrebi as soon as you spoke, by your accent. Then to test you further, I mentioned a certain street and mosque. You said that you walked that street and prayed at that mosque in Marrakesh. But unfortunately for the plausibility of your statement, both are in Cairo. I also suspected that you were no castrado. Now—I know."

"If it is gold you want as the price of silence, I have it not," I said.

She laughed harshly.

"Gold! I have enough for us both—for a dozen more like us, were all to live a hundred years. Until today I was the Pasha's favorite. He showered me with gold, jewels and presents. But today, Selma Hanoum robs me of my place. Today I must sit back with the others over whom I have lorded it, to be neglected—humiliated."

She snatched a dagger from her bosom—brandished it in my face.

"You see this? I had intended to sheathe it in the heart of Selma Hanoum, who was brought here to usurp my place. Then I saw you. It seemed a fair exchange. In taking the Pasha from me, she brought me you. My eyes are sharp, and I was not deceived like the others. Moreover, I was pleased with what I saw. But now—it seems that you would scorn me."

To my surprise, she dropped the dagger, burst into tears, and flung herself face down on the diwan. My first impulse was to flee, but before I had taken three steps I thought better of it. Here, indeed, was a dangerous, headstrong girl. Capable of committing murder because her plans were thwarted, she certainly would not be above carrying out her threat and reporting me to the Pasha. She must be calmed somehow—pacified.

I knelt beside the diwan, laid my arm across her shaking shoulders.

"Dry your tears, my pretty one," I said. "It was not scorn that made me act as I did, for I have a profound admiration for your exquisite charms."

"Then—what—was it?'' she asked, between sobs.

"Piety," I replied, "and humility. It is both unlawful and unseemly that I, a mere—"

"Oh Father of Lies!" she interrupted. "Do you think thus to deceive me? I will give you one chance, and one only. Tonight when the Pasha goes in to Selma Hanoum, come to me. If you do not, tomorrow will be the day of your death. You have until midnight to make your choice—the arms of Fitnah or the sword of the headsman."

"Why, that's a choice easy to make," I replied. "It will be a pleasure for me to see that, while the Pasha is engaged this evening, you do not lack a lover."

I REELED out of Fitnah's apartment, my brain awhirl. A plan had occurred to me on the spur of the moment, which had led me to make the rash promise that she would not lack an amorado that night. Yet this scheme, I now reflected, required the co-operation of Selma Hanoum if it were to have even a slight chance of success. And judging from the look of scorn with which she had favored me when she saw Fitnah in my arms, she was not in a mood to be of assistance to me.

Returning to my diwan beside the door, I flung myself down to think—to plan. What could I say to Selma? If I were to try to explain the compromising situation in which she had found me, would she listen?

So wrapped was I in the dark mantle of my gloomy meditations that I did not, at first, see that the object of my thoughts stood in her doorway and was endeavoring to attract my attention. But the persistent clinking of a bracelet against the door jamb caused me to raise my eyes.

To my astonishment, I saw that Selma was beckoning to me. When she saw that I understood her signal, she stepped back, letting the curtain fall in front of her.

Rising, I hurried to her doorway, drew back the curtain, and entered. Selma was reclining on her diwan in a pose that revealed every seductive curve of her perfectly modeled body.

As my eyes drank in the glory of her loveliness, I mentally compared her with Fitnah, who, though she would have been accounted a great beauty even in the seraglio of the Sultan, was coarse and uninteresting when compared to my little slave girl. So filled was my heart with the love of Selma that the very thought of Fitnah in my arms brought revulsion. It seemed to me that I must have been jinn-mad to have even been tempted by the charms of the Maghrebi after having once seen the Rose of Mosul. The voice of Selma recalled me from my ecstasy of adoration.

"There are some things that must be done quickly," she said, "and I can not accomplish them without your aid."

"Your slave but awaits instructions, hanoum," I replied.

She seemed to have completely forgotten the Fitnah episode, and the explanations which I had planned to make were thereby postponed.

"The panel," she said, "is in the room directly across from this one, occupied by Jabala, the Kashmiri. I must have that room."

"Are you suggesting that I strangle this Kashmiri?" I asked.

"Hardly that," she replied. "You seem to have persuasive ways with women. Suppose you induce her to take another room. There are several others vacant."

"I will try, hanoum," I replied, and bowing, withdrew.

Throughout the short interview she had shown no emotion whatever. I could not tell whether she had been angered at sight of the girl in my arms, or was merely indifferent. Neither boded good for me.

CROSSING the corridor, I raised the curtain.

Reclining on a diwan was a brown-skinned girl of voluptuous form and not unpleasing features. She was loaded down with jewelry and bangles of all descriptions. Finger rings, toe rings, anklets, bracelets, armlets and necklaces were hung on her person in such numbers that the aggregate would have been enough to start a small jeweler's shop. And not only were her body and limbs bedecked, but her face and head as well. Heavy rings hung from her ears, stretching the lobes. There was a diamond pasted to the middle of her forehead. And a large ruby flashed from one pierced nostril. Her headdress was decked with coins and metal ornaments.

"Is this the apartment of Jabala, the Kashmiri?" I asked.

"Jabala would not otherwise be using it, O chamberlain," she drawled, in a rich contralto voice with a husky undertone. "I have been instructed, ya sitt," I said, "to assist you to move to another apartment."

"But I do not care to move," she replied. "I like this apartment."

"Is it your desire that I so inform the Pasha?'' I asked.

"No, I will move. Here, carry this chest."

She pointed to an immense chest, which I upended and took on my back. My ruse had worked, thus far. It would be unfortunate if I should happen to stumble upon Mansur or the Pasha in the corridor.

I looked out. As there was no one in sight, I stepped forth into the hallway, and made for a room near the rear door, which I knew was vacant.

It was poorly furnished, and much smaller than the one occupied by Jabala, who was evidently well liked by the Pasha. I wondered what the consequences would be when she complained, which she would undoubtedly do next time he visited her. Well, that would be a bridge to cross when the time should come.

As I lowered the chest, Jabala came in behind me, her ornaments tinkling and clattering wich every step.

"It is a small room," she said, "and I dislike it, except for one thing."

"What is that?" I inquired, more out of politeness than curiosity.

"It is conveniently near your diwan," she replied, looking at me in a manner that reminded me of the appraising glances of Fitnah.

Horns of Eblis! Had she, too guessed? Or had Fitnah told her?

I backed hastily out of the room, ignoring the coquettish glance she cast at me from beneath long black lashes, and hurried to the apartment of Selma. She was gone. I stepped across the hall and found her already installed in the room just vacated by the Kashmiri. She closed the door and bolted it.

"I'll show you the secret of the panel," she said. "You may have sudden need for it at any time."

Stepping up on the low diwan, she drew back a corner of the handsome Kashgar rug which hung in the nook behind it. Back of it was a panel that looked no different from the others in the room, surrounded by a molding on which were carved rosettes, spaced about three inches apart.

"Observe," she whispered, "that it is the fifth rosette from the bottom."

She pressed the center of the rosette. There was a click, and the panel slid to the left, revealing a dark opening into which the top of a ladder, nailed to the outer wall, projected from below. Leaning over, she softly called:

"Uncle."

"Coming," was the reply from below, and I heard some one ascending the ladder. In a moment the bearded face of Hasan Aga appeared in the opening.

"What is it?" he asked. "Musa waits below."

"Nothing, except to give you this food," she said, handing him a bundle which she carried, "and to ask you and Musa to remain near the ladder tonight. I may have sudden need of you both."

"We will stay within call," replied Hasan. "Do you plan to run away tonight?"

"My plans are uncertain, as yet," she answered. "The Pasha's wolves have stripped my house," he told her, "and sealed the door with his seal. It may be, however, that we can escape over the garden wall without attracting attention. I go now, but we will be near the foot of the ladder, Musa and I. Allah guide and keep you."

"And you, ya amm," she replied. He descended, and she again pressed the center of the fifth rosette, whereupon the panel slid back into place. I resolved to broach my plan.

"Fitnah has discovered that I am no eunuch," I said.

"I surmised as much," replied Selma, dropping to the diwan.

"She knew I was no Moor by my accent," I went on.

"Yes?"

"And she trapped me into recognizing a street and mosque in Marrakesh, which are really in Cairo. She guessed the rest."

Selma looked at me searchingly.

"Did you say: 'Guessed'?"

I felt myself blushing furiously, and for the first time was thankful for my walnut juice complexion.

"Selma, believe me," I pleaded. "I did not mean to make love to her—did not want her in my arms. I swear to you by the Most High Name—"

"Stop!" she commanded imperiously. She regarded me with a look of regal hauteur, eyes flashing furiously. Though fortune had made her my slave-girl she was still the daughter of a pasha.

"How dare you mention the Most High Name in the same breath with that brazen adulteress? Go! Leave me! Do you think I am interested in your vulgar amours?"'

"Only insofar as they concern our mutual desire to frustrate the Pasha," I replied, nettled. "I had a plan which involves this Fitnah. If you do not care to hear it, I will go. I came into this affair, risking my life, for one reason alone. I love you, and desire to serve you. From you, I have asked, and now ask—nothing."

"That is true," she admitted, softening. "Allah forgive me, I spoke without right or reason."

She rose, and gently laid a hand on my arm.

"I'm sorry," she murmured, contritely. "Please tell me of your plan."

"Tonight the Pasha comes to you," I said. "This Fitnah has threatened to betray me, unless—"

"Hush," she admonished. "Speak in a whisper. Some one may hear you."

And so I whispered in her shell-pink ear the plan that had occurred to me when I had, under compulsion, made a certain promise to the Maghrebi dancing-girl.

LATE that night I lay, turning and tossing on my diwan beside the rear door. Needless to say, I had not slept. Twice, earlier in the evening, the Kashmiri had appeared in her doorway, signing to me with her eyes. But I had pretended not to see. Once, as I patrolled the corridor, Sa'id, the fat Bowab of the bab al harim, had called to me across the majlis, volunteering the information that the Pasha was drinking in the salamlik with boon companions. Faintly there had come to me the sound of dance music, followed by drunken shouts and ribald laughter.

The inmates of the harim had all retired. Many of them snored, but loudest of all snored the plump Kashmiri, whose room was near my diwan. Under other circumstances I should have cursed her for it, but that night I was thankful to be thus loudly apprised of the fact that she slept.

It had been a long, nerve-racking vigil. In the early morning stillness every sound was intensified. From some near-by roost a cock crowed. Others answered him, each in a different pitch. A young cockerel essayed to imitate them, but his voice broke in the middle with a choking sound, and he ended with a feeble squawk.

Suddenly I heard footsteps at the dab al harim, and some one gabbling loudly—drunkenly. Leaping up, I hurried to the women's majlis. Across the room came the Pasha, leaning heavily on the brawny arm of Mansur. I made profound obeisance as he came up. He was very drunk and very maudlin.

"Peace upon you, lord of the bedchamber," he said to me. "Where's my little rosebud?"

"I kiss ground between your hands, O protector of the poor," I said. "The lady eagerly awaits Your Excellency's coming, and pines because you have remained away from her for so long."

"I was busy," he said with drunken gravity. "Very important conference. Take me to her."

He turned to the big Nubian. "Go to bed, Mansur."

The huge eunuch bowed solemnly, but grinned derisively behind his back as Mohammed lurched over to support himself by clinging to my arm. As Mansur moved away, the Pasha looked up at me, squinting his single, bloodshot eye.

"Wallah!" he said, swaying from side to side. "I've drunk enough 'rak this night to float the Russian fleet. Did you say the lady was pining for my company?"

"She is devastated by Your Excellency's neglect of her," I replied. He fumbled at his waistband—found and produced a piece of gold which he handed me.

"Allah increase your prosperity," I said, pouching the gold.

"Lead on," he ordered. "Don't want my little rosebud to suffer any longer than necessary."

"The lady has asked, as a special favor, that her room be kept in darkness this night," I said, as we strolled down the corridor. "You know she has—"

"Say no more," he interrupted. "Her wish shall be granted. Light or dark, it's all the same to me."

We stopped before the door of the apartment, and I drew back the curtain. The Pasha stumbled in. I closed the door behind him and dropped the curtain. Then I turned and crossed the corridor, entering the opposite room in which a single candle sputtered, and softly closing the door behind me.

The girl on the diwan sat up. "I must have fallen asleep. Has he come?"

"Yes, hanoum," I replied. "He is very drunk, and has gone in to Fitnah. Thus far my plan has worked. The girl has discovered the trick by now, of course, but she will not dare to say anything. As for the Pasha, he is so overcome with 'raki that I doubt if he could tell a woman from a camel, let alone one woman from another. Besides, the room is in darkness. I suggested this to Fitnah for safety's sake, then told the Pasha it was your wish that it be kept dark."

"Which was quite true," she said. "We must tell my uncle and Musa of this."

Turning, she raised the rug and pressed the button. The panel slid back, and a low call brought Hasan Aga and Musa she said, scrambling up the ladder. Then we four went into council. The aga and eunuch were convulsed with laughter when I told them how we had thus far outwitted the tyrant and his scheming concubine.

But after, Hasan grew grave.

"We are safe enough for the present," he said, "but when the Pasha wakens it will be a different story. Both of you will be in deadly peril."

"Perhaps it would be best if we would all go into the souterrain now," said Selma. "It might be that we could hold out there until the arrival of Ismail Pasha."

"Your cousin may arrive tomorrow," said Hasan. "On the other hand, he may be delayed for weeks or months. Or he may never come. It is possible that he has not been granted a firman. In this case, we should starve in the souterrain without help from outside. For who, in this city, would dare to help us? The fate of Tafas and others before him is a sufficient warning to prevent others trying to befriend us.

"On the other hand, we might try to escape under cover of darkness. But where could we go? And how? Without horses or camels or the means to hire or purchase any, we could not get far. We would only be apprehended and exeauted, and Selma would be returned to the Pasha's harim without hope of succor."

"Why not slit the throats of this Cretan's son and his wench, and hide their bodies in the souterrain?" asked Musa.

"There is nothing I would like better," said Hasan, "and there are thousands of true believers in this pashalik who would applaud the act. But it could only bring death to all of us in the end. The arm of the Sultan is long, and the majesty of his government must be maintained."'

"It seems to me," I said, "that the hanoum and I should be able to carry on here for at least another day. The Pasha mentioned no names last night, and it was only natural for me to lead him to the door of his favorite. As for this Maghrebi, she will not dare to expose me to the Pasha for fear I might reveal her defection."

"One never knows what a woman will do," said Hasan. "However, if it is the wish of Selma that this be done, I see no serious objection. There is, after all, little choice between one course and another. Musa and I will be here within call if trouble arises, and as a last resort we can bolt the door of this room, pry out the window bars to make it appear that we escaped that way, and then enter the souterrain."

And so it was agreed. Hasan and Musa returned to the souterrain, and I to my diwan beside the door.

I arrived just in time to make ablution and pray the dawn prayer. Presently a slave-girl brought me my breakfast. Soon the harim inmates began coming out of their rooms. Some went into the malizs, Selma among these. Others strolled out into the garden.

Presently Fitnah came out of her apartment and strode toward me, hands on hips, her brow a thundercloud of wrath.

"So, O consort of a flea-bitten camel," she snarled, "you thought to play a trick on your little Moorish cousin. For this, O mangy dog, shall your head and shoulders part company this day."

"I but carried out your wishes, ya sitt," I said, feigning bewilderment and great humility. "You feared that His Excellency's favor might be transferred to another, so I brought him to you. Now you reward me with threats and abuse."

But her anger was no whit abated.

"You will soon learn, O great blundering baboon," she predicted, "that Fitnah does not threaten idly. You well knew my desire, yet you brought me this old he-goat, too drunk for aught but sleep. What cared I if he went in to Selma on one night or another? My rule of this harim is ended, in any case, and I am not jealous of his maudlin caresses."

"Could I then disregard the wishes of the Pasha?" I asked. "What do you mean?"

"Why he commanded that I conduct him to his little rosebud. Who, other than you, his favorite, would he name in such endearing terms?"

Fitnah looked at me long and searchingly.

"If this be true," she said, "I will forgive you. If not, your head shall be forfeit. We will know when the master wakens."

She turned and walked off into the majlis, hands on swaying hips, to mingle with the others.

Some three hours later the Pasha poked his ugly, pock-marked phiz and shaven poll out the door and bawled loudly for coffee. A half-dozen girls came running at his call, bearing steaming pots and cups. Among them were Fitnah and Jabala. He squinted down the corridor at me.

"Where is Selma Hanoum?" he asked.

"In the majlis, Excellency," I replied.

"Fetch her," he commanded, and withdrew into the room, followed by the girls.

I went into the majizs and quickly told Selma of what had occurred.

"If Fitnah tells," she whispered, "you must contrive some way to have Musa take your place."

Then, aloud, she said: "Conduct me to His Excellency."

The Pasha was in a vile humor. It was evident that in his long bout with the 'raki he had come off second best. Jabala was bathing his pock-marked brow with cold water while Fitnah poured coffee. The others were standing around, trying to curry favor by looking sympathetic. He tossed off a cup of searing hot coffee, then looked up with his single, bleary eye as I led Selma before him.

"How was it, Selma Hanoum," he demanded, "that you were not in attendance on me when I wakened this morning? Should I, the Pasha, be left alone, to die like a dog, unattended?"

"I leave you, Excellency?" said Selma, with a look of surprize. "I do not understand."

"It was my diwan you shared last evening, my lord," cooed Fitnah, proffering more coffee.

"What!" The Pasha struck the cup from her hand, spattering her with the hot liquid and shattering it on the floor. Then he glared up at me.

"How came you to do this, you filthy blackamoor?" he demanded.

"I but obeyed your Excellency's orders," I replied. "Your command was that I conduct you to your little rosebud. It was my understanding that you meant none other than, Fitnah, your favorite."

"So! You misunderstood! Wallah! We have something strange here."

"I can explain, my lord," said Fitnah.

Cold chills chased up and down my spine as I saw the venomous looks with which she regarded Selma and me.

"Then do so, and make an end of it," growled the Pasha. "I am in no mood for mysteries this morning."

"This man brought you to me," continued Fitnah, "because he is an impostor. He is neither Moor nor eunuch, but the lover of Selma Hanoum, whom she has brazenly smuggled into your harim."

It was a bold speech, and I could readily see the craft that lay behind it. For at one stroke, Fitnah planned thus to get rid of both me and her hated rival.

The Pasha's face went livid. For a moment he said nothing, but only glared at me, making little choking noises in his throat.

"Mansur! Get Mansur!" he finally managed to articulate. "We'll soon test the truth of this statement." One of the girls dashed out of the room to call che chief eunuch.

"Permit me to suggest, Excellency," I said, "that Mansur's ministrations might prove embarrassing here before your ladies. With your permission, I will await him in the room across the corridor. In the meantime, I might suggest that you make inquiry of Fitnah as to how she acquired the intimate knowledge that she seems so sure of, and also learn why, if she possessed this knowledge, she did not denounce me before."

With this parting shot, I bowed and withdrew.

Once outside, I leaped across the corridor, entered the room opposite, and softly bolted the door behind me. Then I opened the panel and called Musa. He must have been at the very foot of the ladder, for he arrived at the opening in a few seconds.

"Unbolt the door," I told him, "and wait here. Mansur will come to examine you, for you have been accused of being an impostor—neither a Moor nor a eunuch. Talk no more than necessary, but if you are questioned, remember what I told you of last night's adventures, and stick to the story."

Musa chuckled. "Who accuses me?" he asked.

"You are accused by Fitnah, the Maghrebi dancing-girl," I replied. "'Remember the story. I'll be waiting behind the panel."

While Musa unbolted the door, I crawled through the opening and closed the panel behind me. To my surprize, I saw a small peephole, cut beneath the panel, which I had not noticed from the outside. To this I applied my eye. Scarcely had I done so ere the giant Mansur burst into the room.

Glaring at Musa, he roared: "So! You are neither Maghrebi nor eunuch!"

"On the contrary," said Musa, stripping off his loin-cloth and dropping it to the floor, "I am both." Mansur stared at him for a moment, then laughed uproariously. "Waha!" he exclaimed. "Behold! If I mistake not, the Moorish girl will get forty stripes for her pains."

Just then the Pasha lumbered through the door.

"What's this talk of stripes, Mansur?" he asked, "'and why this boisterous laughter?"'

"Billah!" replied the Nubian, "if this man be not a eunuch then am I a flaxen-haired Ferringeh. Your Excellency can see for yourself that the girl lied."

"Why, so she did,'"' said the Pasha. "The stripes will be in order, Mansur. Lay them on without stint, but take her to a room at the end of the corridor and close the door so her cries will not disturb me."' "Harkening and obedience, Excellency," replied the Nubian, hurrying away with a broad grin on his face. Mohammed turned to Musa. "Resume your loin-cloth, O lord of the bedchamber," he said.

"Then fetch Selma Hanoum to me here. I like this room better than the other."

"To hear is to obey, my lord," replied Musa, donning his loin-cloth. Then he went out. Swiftly I descended the ladder. Hasan Aga was waiting in the darkness at the bottom.

"What mischief is afoot now?" he asked. "The Pasha has ordered Musa to bring your sister's daughter to the room above," I said. "The time has come to strike."'

"Agreed," he answered. "Lead on, and I will follow."

I MOUNTED the ladder swiftly, Hasan at my heels. Scarcely had I reached the top and applied my eye to the peephole, ere I saw Musa enter the room with Selma Hanoum. The Pasha was seated on one end of the diwan. As the two came before him, he said:

"Stand guard outside, chamberlain, and close the door. See that I am not disturbed."'

"I hear and obey, Excellency," replied Musa, but looked questioningly at Selma as he said it. She nodded slightly, and he went out. I could see that she was deathly pale. Evidently she had strong faith in those of us who waited behind the panel or she would not have permitted Musa to go.

The Pasha took a bottle of 'raki from the taboret and poured himself a stiff drink. Raising the glass to the girl who stood before him, he said: "With health and gladness!" Then he gulped it down, and seized her wrist. "Sit here beside me, little rosebud," he said. "Be not afraid."

She jerked her arm free, eyes blazing.

"What! You resist me?" he bellowed, leaping to his feet. "Why then, I'll tame you, little tigress."

Quickly I slid the panel back and sprang through the opening. The Pasha heard me, and half turned, whipping out his simitar.

"Treason!" he shouted. "Assassins! To me, Mansur! To me, Sa'id!"

With bared blade I leaped at him, intending to stop his mouth for good. I slashed at his bull neck, but his steel was there to meet mine, and he countered with a stroke so swift and sure that only my skill and extreme quickness of wrist averted my entrance into Paradise at that instant. Despite his age and girth, he proved to be a master of cut and parry.

"Fool," he grated. "Think you to best a seasoned swordsman like me? I have slain of youths like you, a thousand save one, and you shall make up the thousand."

Too eager to end the contest with dispatch, I received a slashed shoulder for my carelessness. Presently, however, I managed to bind his blade with mine—a trick I had once learned from a Ferringeh swordsman—and whirling it from his grasp sent it clattering into a corner. Weaponless, and expecting instant death, he sank to his knees, groveling before me, crying:

"Mercy, lord chamberlain! Spare me, and I will make you rich and mighty."

"Bind, gag and hoodwink this whining dog," I told Hasan.

This the aga did with great good will, while I stood over him with the simitar. Meanwhile, I heard the clash of steel on steel outside, and knew that Musa was engaged. I was about to go to his assistance when the noise ceased, and he came in, grinning.

"The fat bowab of the bab al harim attacked me," he said, "but my point raked his cheek, and he turned and ran, screaming that he had been murdered."

"Bolt the door," I told him. But I spoke too late, for at that moment, Mansur rushed through the doorway, brandishing his huge simitar. Swinging his heavy weapon with both hands, the giant Nubian struck at me—a mighty blow that, had it landed, must have split me in twain. But I sidestepped, and brought my blade down on his head with all my might. It bit deep into his wooly skull, and he pitched to the floor without a sound, dead.

Musa sprang to the door and slid the bolt. Outside I could hear the frightened screams of the Harim inmates, the heavy footfalls of running men, and the clank of weapons.

"The guards are coming," I said. "Into the souterrain, all of you. We'll take this fat pig with us. You first, Musa. Then the Pasha, followed by Hasan. I'll follow Selma Hanoum in case they break down the door before we close the panel."

We bundled the bound, gagged and blindfolded Pasha through the opening, and placed his feet on the rounds of the ladder. Then, Musa supporting him from beneath and Hasan steadying him from above, they took him down into the souterrain.

Selma, who had donned her street attire, quickly followed them. The door was splintering beneath the blows of the soldiers as I closed the panel and descended the ladder. At the bottom, Musa took up a lantern he had left there, and led the way between gray stone walls down a dank and musty passageway.

Presently we came to the foot of another ladder. Here Musa passed his lantern to Hasan, and together, he and I got the Pasha up to the top. When we were through the panel opening, the aga and his niece followed. We took the Pasha into Hasan's majlis, and removing his hoodwink and gag, but leaving his hands bound, seated him on the floor.

"I regret, Excellency," said Hasan Aga, "that I can not seat you on a diwan, or even a rug. But, as you can see, your soldiers ate from my house with their usual thoroughness."

The Pasha looked up sullenly. "I'm a man of few words," he said. "Name your price, and let us get down to business."

"As you may have surmised," said Hasan Aga, "we are desirous of leaving Mosul. We will require horses, camels, slaves and traveling equipment, and, let us say, five thousand pounds Turkish."

"Five thousand pounds!" groaned the Pasha. "There is not so much wealth in all my pashalik."

"We will also require your company for at least three days on the road," continued Hasan, "after which you will be given a horse and our blessing."

"Release his hands, that he may write," he told Musa. The eunuch removed his bonds, but before he could begin there came sounds of a tremendous commotion in the street outside.

First we heard much cheering and the barking of dogs. Then came the thunder of hoofbeats, the shouts of riding men, and the clank of weapons. Selma ran to the window—peered out through the lattice.

"No need to bargain with this Cretan dog, now," she said. "It's Cousin Ismail Pasha and his brave riders."

She hurried to the door and flung it wide, then rushed out into the street with Hasan and me hurrying after her in wild excitement. Behind us came the Pasha, with Musa, bared blade in hand, watching him as a cat watches a mouse. "Alhamdolillah!" exclaimed Hasan. "Allah be praised! It is indeed Ismail Pasha!"

The young Pasha, a handsome, richly dressed youth mounted on a prancing jetblack stallion, pulled his steed to a halt before us. Springing lightly from the saddle and tossing his reins to an attendant, he warmly greeted Hasan and Selma.

"I have the firman,"' he said, exhibiting an official-looking packet. "Mohammed Pasha is deposed and I am to govern in his stead until the arrival of the new appointee, Hafiz Pasha."

THE next day, Hasan Aga and I were seated in his refurnished majlis, smoking and sipping coffee. Outside, the rain poured down in torrents, as from the mouths of water-skins. Presently there came a knocking at the door. A moment later a servant ushered in Musa.

Leaving his dripping aba and muddy shoes at the door, he came up, and bowing low before me, said: "Saidi, I bear a message for you from my lady. She bids me inform you that, having rid her house of the Cretan and put it once more in order, she would feel honored if you would visit her this afternoon."

"At what time?" I asked.

"At such time as suits your convenience, my lord," he replied. "Tell her to expect me in half an hour," I told him. He bowed, and withdrew.

A half-hour later, with my cloak drawn tightly about me to keep off the pelting rain, I was picking my way up the muddy street toward Selma's house, when I saw a short, rotund and quite familiar figure hurrying toward me in bedraggled garments, followed by a number of urchins who were shouting insults and pelting him with mud balls. It was Mohammed Pasha.

In order to escape his young tormentors, he dodged into the doorway of a deserted and nearly roofless house. Coming up, I checked the youngsters as they were about to follow him inside. Then, giving them a handful of coppers, I told them to be off.

The deposed Pasha squinted at me without recognition, for I had succeeded in removing most of the walnut juice from my skin and was now dressed with the splendor of an aga, from Hasan's own wardrobe.

"May Allah reward you, said," he said, "but not as I have been rewarded. Yesterday all those dogs were kissing my feet. Today, every one and every thing falls upon me, even the rain."

He was a picture of dejection, standing there in his wet, mud-stained garments with the water sifting down on him through the leaky roof.

Moving on, I was soon at the door of Selma Hanoum's house, where a slave took my shoes and cloak, and ushered me through the salamlik into the majlis. In a moment, a slender, veiled figure came down the stairs and walked toward me. It was Selma.

"Your slave girl welcomes you to her house, Master," she said, taking my hand and conducting me to a diwan.

Then she clapped her hands, whereupon slaves brought a pipe, coffee things, and a brazier of glowing charcoal. She waved the slaves away, and with her own fair hands lighted the pipe for me. Then she prepared coffee over the glowing brazier while I told her of my meeting with the deposed Pasha.

"It is the justice of Allah," she said. "Through his own misdeeds the Cretan's son has been reduced to beggary. Most folk believe that he deserves worse, but Allah is all-knowing."

She moved a taboret up close to the diwan, and sitting on a cushion before me, poured coffee. Then she handed me a steaming cup. I sipped in silence, waiting for her to speak, for I was positive that she had sent for me that she might purchase her freedom. She was tantalizingly close, and Shaitan tempted me to crush her in my arms. But I forbore.

Presently she asked: "Is there aught else that your slave girl can do for you, Master?"

Allah! How I loved her—desired her above everything in this world or the next. But I knew such thoughts were madness. Returning my cup to the taboret, I stood up.

"Let us have done with this pretense of master and slave, hanoum," I said.

"Why, if you wish, my lord," she replied, also rising. "You bought me at quite a reasonable figure, and I am willing to pay you a good profit on the investment. What do you say to a thousand pounds, Turkish?"

"I say: 'Keep your gold,'" I replied. "For I give you back to yourself, free of all debt or obligation."

"But you are without funds. Surely you will accept a reward for your brave services."

"I have my reward, hanoum. It is better than gold, for it can never be taken from me—better than friendship, for it can never prove false. It is my memory of one beautiful and exquisite rose, which I have seen, loved, and lost."

With that, I turned and strode toward the door. There was a patter of footsteps behind me. A little hand was laid on my arm. I whirled to see her standing there, unveiled in all her loveliness. And in her eyes there shone a light which a man may see but once, yet never misunderstand.

"Oh my Master!" she cried.

"Leave me not desolate!"

Tender, yielding, lovely as a rose pearled with dew, she came to me—gave me her sweet lips.

"Take me, Hamed," she murmured. 'Never let me go. All that I am, all that I have, is yours."

AND so, effendi, Selma, the one beautiful and exquisite rose, became mine, bringing me happiness indescribable and wealth untold. And we lived together a life of joy and contentment until Allah Almighty saw fit to receive her into His mercy.

Ho, Silat! Bring the sweet and take the full.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright