RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

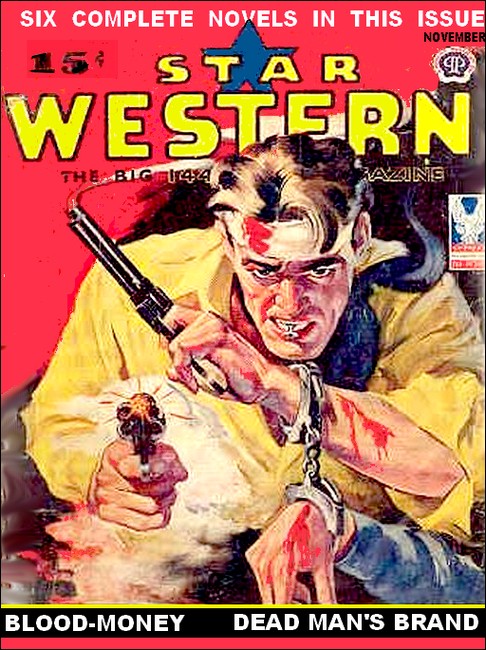

Star Western, November 1942, with "Dead Man's Brand"

Nothing in the world he could either do or say would convince the cold-eyed, manhunting sheriff of Three Pines that Dave Tully, drifting pilgrim, wasn't actually his own murderer—carrying out a grim masquerade in the vain, desperate hope of avoiding hang-noose death.... For his filled grave would also fill the pockets of the crookedest murder combine on the roaring gold frontier!

DAVE TULLY was riding with his right knee crooked up around the saddle horn, reins held in his left hand. He wasn't riding that way because it was comfortable or because he preferred it, but because he wanted to watch both where he was going and where he had come from without craning his neck too much. He was holding a Winchester carbine in his right hand.

He wasn't looking for trouble, but he was expecting it.

His horse plodded along laboriously up the steep grade, snorting now and then with the effort, and his narrowed blue-gray eyes studied this high country—mountains jumbled together in broken, uneven folds with the rock jutting bare and jagged from their sides. The sun was an immense, hot hand laid against Tully's back. The air was thin and lifeless.

Almost at the top of the grade, Tully pulled up and sat looking back down the trail. There was no movement on it anywhere except the thin jiggle of heat waves. Tully hadn't expected to see anything else, but he would very much have liked to. For someone had been following him for the last three or four hours. A man who was very smart about keeping out of sight, and who knew the country, as Tully certainly did not. Just as he didn't know either why he was being trailed, or what this mysterious trailer looked like.

He had tried to find out. He had waited several times, as he was doing now, and twice had doubled back on his trail. He had come close enough once to hear the clack of rocks rolling under a horse's hoofs, but that was all.

Tully froze, watching his horse. The horse was looking up the trail ahead, and its ears were pricked forward enquiringly.

Tully flipped his leg over the horn and sat square in the saddle, listening, but the silence was so intense it seemed to hum in his ears. Then he pulled the horse over to the left and walked it ahead slowly.

At the top of the grade, the trail angled sharply around a weather-worn rock slide. Tully rode up into its shadow and then pulled wide to the right so he could look around it.

There were two horsemen blocking the way fifty yards dead ahead. Both of them held rifles, and they raised them instantly when they saw Tully.

"Hold it!" one of them shouted.

Tully slapped his spurs home and spun his horse back and around in a sudden flurry of dust.

He left the horse near the place he had halted before and ducked into the shelter of a crevice that cut down through the rock wall. He climbed up, boots slipping on loose stones, and then braced his back against the angle at the top of the crevice. He slid the barrel of the carbine over the ledge in front of him and waited, breathing hard. He could see both ways along the road now, and the ledge covered him from an approach in either direction.

Below him, his horse stamped and snorted in protest. And then a voice, directly behind him, said softly: "I figured you'd hole up about here."

Tully sat rigid, a trickle of sweat running down clammily across his cheek.

"That's right," eased the voice. "That's the way to act. Just sit nice and quiet. And now you can slide that carbine a mite forward."

"It's cocked," Tully said. "It'll let go if I drop it."

"Then you uncock it first, son. Be real careful how you do it."

Tully did so, and pushed the carbine over the ledge. It fell on the other side with a metallic thump.

"That's fine," said the voice. "Now I'm gonna sing out, son. Don't get jumpy. Oh, Bert! Ed!"

"Yeah, Jim," another voice answered.

The two horsemen Tully had seen rode cautiously around the rock slide.

"Here, boys," said the man behind Tully. "I've got him. Now, son, you just sorta slide down the rocks the way you clumb up."

"Can I turn around first?" Tully asked.

"Sure, if you're a' mind to. Take it slow."

Tully looked over his shoulder. The man was squatting on the slope just above him like a huge, ungainly frog. He had a reddened, wind-burned face that was frayed with a stubble of gray beard, and his blue eyes stared back at Tully with round, solemn curiosity. He was wearing a black store suit, so worn it was shiny and greenish at the seams, and the long-barreled six-shooter in his right hand was aimed squarely at Tully's face.

But Tully was staring incredulously at the small, nickeled star that was pinned on the man's sweat-stained vest.

"That's right, son," the man answered his unspoken question. "I'm sheriff of Three Pines County, and that's where you are now. Jim Fellows, by name."

"Well, what are you after me for?" Tully asked.

"Why, as to that," Fellows said, "you never can tell. What, for instance, might your name be?"

"Dave Tully."

"You sure of that, son? Your memory ain't failin' you or nothin' like that?"

"No," said Tully. "That's my name. What about it?"

Fellows moved the six-shooter meaningly. "You just turn around and slide down to the road."

Tully shrugged and obeyed. One of the two riders had caught Tully's horse, and both of them stared at him with a sort of wary interest.

"This him?" one asked. He had a dourly sullen face and a long, bedraggled mustache.

Fellows slid down to the road in a shower of loose rock, puffing breathlessly. "Reckon so. Says his name is Dave Tully. Run down and get my horse, will you, Ed?"

The dour-faced man rode on.

The second rider shifted in his saddle, still staring down at Tully. He was much younger than either Fellows or the man called Ed. He was wearing a gaudy pink shirt and an immense peak-brimmed sombrero. Under the hat brim his face was thin and white.

"He ain't wearin' no belt gun," he observed.

"Nope," said Fellows. "But he's mighty free with this-here carbine. He can get it ready awful fast when he gets spooky. Come pretty near runnin' me down a couple times today, and I was trailin' him as quiet as an Injun."

"I don't like people followin' me around," Tully said. "What was the idea? I'm getting tired of this."

"You'll get tireder before you're through, son. You're liable to get so tired it'll be fatal. Care to tell me your name again?"

"It's Dave Tully."

Fellows nodded at the pink-shirted rider. "You heard him say that, Bert. You're a witness, should he try to back out of it later."

"I don't want to back out of it!" Tully said angrily. "It's nothing special, but it serves me all right. What's the matter with it?"

"Nothin'," said Fellows. "Nothin', son. Except it ain't yours. You didn't bury him deep enough, son."

Tully stared at him. "What?" he asked incredulously.

"Dave Tully," Fellows explained. "You shoulda buried him deeper after you killed him. The coyotes dug him up, and he was identified."

"You must be crazy!" Tully said. "I'm Dave Tully, and I haven't been dug up by coyotes, either!"

Fellows nodded at Tully. "I'm afraid he's right, son. I got a telegram from Sheriff Sloan tellin' me that you had murdered Dave Tully and was pretendin' to be him so you could collect some property Dave Tully inherited."

"That's a damned lie!" Tully shouted. "I'm Dave Tully! I inherited some property from my uncle, and I came here to see what it was! I've got the letter from the lawyer right here now in my pocket! Want to see it?"

Fellows jerked the six-gun up instantly. "It won't do you no good to yell an holler. I know you got that letter. Sheriff Sloan said you took everything Dave Tully had on him—letters and papers and money and all. You couldn't expect to get Dave's property unless you had some proof that you was him."

"I am him, I tell you!"

"Now, son," Fellows said. "No use takin' on about it this way. You're caught fair, and you got to swallow your medicine. Sheriff Sloan is investigatin' who left the country in a hurry about the time Dave Tully was murdered. When he finds out, that'll be you, probably. Anyway, we'll find out when he comes to fetch you back. He'll recognize you."

"He sure will!" Tully snapped. "He's known me for years!"

"Then you might as well tell me your real name, son."

"Dave Tully!"

"You're a stubborn cuss," said Fellows. "But it ain't gonna do you a bit of good. You're goin' to jail in Clearwater, and you're gonna sit right there until Sheriff Sloan comes to fetch you. Here comes Ed with my horse now. You gonna get on your own horse and act quiet and sensible, or do you wanta get roped and dragged to Clearwater?"

"I'll act quiet," Tully said grimly. "For now."

CLEARWATER was far different from the sprawling, open range towns that Tully was used to.

Rock canyon walls towered high above it, and there were three wooden bridges on the main street that crossed and recrossed the icy-blue fast flowing stream that gave it its name. Houses were built in ragged layers back and up from the canyon floor.

The deep mountain twilight had fallen when they rode across the lower bridge into the straggling, two-block business section, and lights showed brightly yellow behind open windows and doors. Men were shadowy, lounging figures along the boardwalks and on porch steps, and they shouted eager questions at the riders.

Fellows merely flipped a hand absently in answer, but Bert of the pink shirt was ready and willing to talk to anyone who listen.

"Sure!" he shouted. "We got him! Naw! No shootin'. He give up as soon as we braced him.... Sure! Yellow, like all bushwhackers!"

The jail was a long, low building pushed in close against the canyon wall at the upper end of the main street. Fellows dismounted heavily at the hitching rail in front and nodded at Tully.

"Just come right in, son."

A group of the loafers crowded around now, staring curiously at Tully, but Fellows waved them back.

"Keep away now, men. You'll learn all about it soon enough. Bert, you put the horses in the corral. Ed, you stay here at the door. I don't wanta be disturbed."

Tully preceded him into a small, bare room papered with reward posters and crowded with two dustily jumbled desks. A scrawny little man with an egg-smooth head popped up from behind one of the desks, rubbing his hands with avid curiosity.

"Hi, Jim! Got him, did you? Did he put up a fight, Jim? Was there shootin'? Anybody get beefed? Hey, Jim?"

"Take it easy, Elmer," Fellows said. "You'll give yourself a stomach ache. This fella didn't do no shootin' because I didn't give him no chance to. Now, son, you just empty your pockets there on the table."

Tully turned out the contents of his pockets. "I've got a money belt, too," he said. "Want that?"

"Well, son," said Fellows apologetically. "I think maybe we'd better have it. Might be evidence. Can't tell."

Tully unfastened the money belt and laid it on the table. "I've got the remains of three months wages in there."

"It'll be safe," Fellows promised. "We don't aim to rob prisoners around here. Elmer will put it all in a bag and put your name on it. And now I think maybe Elmer had better just look again, in case you forgot anything. Hold up your hands and stand steady, son."

Elmer darted around the table and dove into Tully's pockets with both hands, as eager as a squirrel after acorns. He turned out the lining of every one and even investigated the tops of Tully's boots.

"Nothin'," he said in a disappointed tone. "But he's a tricky one, I bet, Jim. He's got a mean look in his eye. He's a dangerous fella, all right, hey?"

"Sure," Fellows said.

The dour-faced Ed leaned in the doorway. "Say, Jim, Bogan is here. Claims he's got a telegram for you."

"Let him in," Fellows ordered.

Another man edged in through the door. He was tall and painfully thin, and his face had the lifeless, dead-white color of dough. He squinted painfully at Tully through dusty, thick-lensed glasses. He wore long pasteboard sleeve guards, and he was carrying a yellow telegraph message blank in his right hand.

Fellows nodded patiently. "You got a message for me, Bogan?"

"Uh? Oh, yeah. Just come through." Bogan held the blank up close to his glasses. "Description of the fella Sheriff Sloan thinks musta murdered Dave Tully. Brown hair. Blue eyes. About five-ten. Medium weight. Real fast and shifty on his feet. Carryin' Dave Tully's Winchester carbine and ridin' Dave Tully's roan horse branded K. Name's Pete York."

Fellows looked at Tully. "Are you Pete York?"

"I'm Dave Tully," said Tully wearily.

Bogan goggled at him incredulously. "Does he still claim that, Jim? Don't he know his goose is cooked?"

"He ain't convinced. Gimme that message." Fellows read it through, moving his lips to form each word. He looked up at Tully. "This description fits you right to a T. Sheriff Sloan says Pete York was a drifter. Didn't do no work. Just loafed around town for awhile and rode grub-line. Blew outta the country right at the time Dave Tully first disappeared. You're that Pete York, ain't you?"

"No!" said Tully. "I don't even know him; never heard of him. This whole business is loco. I'm not dead. Nobody has murdered me."

Elmer giggled. "Somebody's gonna hang you, though. Hey, Jim? This fella's gonna get hung, ain't he?"

"Looks sort of like it," Fellows admitted soberly. "You're in a tight spot, son. Bogan, you run back and send Sheriff Sloan a message tellin' him I found this fella for him and to come and get him. Elmer, gimme your keys. Son, you march ahead of me right through that door over there."

Tully pushed the door open and went into a narrow corridor lined with the glint of steel bars. June bugs batted themselves sizzlingly against the reflector of a kerosene lamp set in a wire guard in the ceiling.

Fellows unlocked a cell door. "In you go, son. Set and think awhile. You'll make this a whole lot easier for everybody if you'll sort of relax and admit what you done."

Tully didn't even bother to answer him. He went in the cell and sat down on the hard board cot. He rested his chin in his hands and stared silently at the floor.

Fellows peered uneasily through the bars, wheezing a little, and then said: "I'm gonna go and get me supper now. I'll bring you somethin' back, or else Elmer will."

He went out of the cell block, closing the door into the office firmly behind him.

"Hey, you," said a voice. "You got any tobacco?"

Tully looked at the cell across the corridor. A leathery, raggedly bearded face was peering at him through the bars.

"No," he said. "They took it away from me when they searched me."

"That's the way they do," the bearded man said glumly. "Fellows is proud of this here rat-trap of his, and he's scared somebody'll burn it down on him. What's your name?"

"Dave Tully. You wanta argue about it?"

"Me? Argue? What for? It ain't exactly a pretty name, but it sounds good enough. Mine's Day. They call me Rainy Day, on account I never take a bath unless I'm caught out in one. What'd they put you in here for?"

"For shooting myself."

"The hell you cry!" said Rainy Day. "You mean, in this stinkin' rock-pile country you can't even shoot yourself without they put you in jail?... Hey, wait a minute! Didn't you get hurt when you shot yourself?"

"I got killed," said Tully glumly.

"Somebody's been foolin' you, mister. You ain't dead."

"Try and tell the sheriff that!" Tully glumly.

"H'm'mm," said Rainy Day. "It's lucky I got such a good brain on me. This looks like it's gonna be tough to figure. Suppose you tell me about it, huh? I got lots of time."

Tully spoke disinterestedly: "I've been working on the Ballard spread up in the Solo River country, where I lived all my life. A month back I got a letter from a lawyer named Carter here in Clearwater tellin' me my Uncle Zip had died near here and left me some property. I didn't think it'd be much, but I figured I could use a little change of scenery, so I rode up this way to see about it."

"Zip Tully," Rainy repeated reflectively. "I knowed him! And I wanta tell you there ain't a meaner, dirtier, crookeder old skunk ever lived on this earth. If you take after him, you better go shoot yourself again. But this time, do it up good!"

"I only saw him once, when I was ten years old. He came to visit us, and my dad ran him off the place because he stole my dad's watch and sold it to a peddler."

"Sounds like Zip," Rainy agreed. "I swear he was meaner than a tarantula. Had an old shack outside of town aways in the brush. If that's what he left you, I don't blame you for shootin' yourself. Nothin' there but three cows that he probably stole somewhere, and one old horse with the heaves."

"I suspected it would be something like that," Tully said. "I just came along for the ride."

"This here shootin' yourself...? Where does that come in?"

"Fellows got a telegram from Sheriff Sloan back in Solo sayin' that somebody had killed me and buried me and was pretendin' to be me so he could collect what I was gonna inherit from my Uncle Zip."

"Doggone! You mean, they actually claim you went and murdered yourself? Why, a smart fella like me can see right away there ain't no sense to that. Who was you supposed to be when you was murderin' yourself?"

"A drifter named Pete York. I never set eyes on him, but he's supposed to look like me. Accordin' to Sheriff Sloan, he's ridin' my horse and shootin' my rifle and probably wearin' my clothes, for all I know."

"What you gonna do about it?" Rainy asked curiously.

"I don't know, but I'm getting damned mad. I've been laughed at and pointed at and hooted at like some freak in a circus, and I don't like that."

"Can't say I blame you," Rainy agreed. "And it'll take that sheriff about a week to get here from Solo providin' he starts right away. Which he won't, if I know sheriffs, and you can bet I do. And this ain't the kind of a rest home I'd pick out for a week's visit, if I was pickin'.... Say, are you really Dave Tully?"

Tully got up and looked for something to throw.

"All right!" said Rainy quickly. "A man can ask a civil question, can't he? You say you're Dave Tully, and I believe you. You know why?"

"Why?" Tully asked warily.

"On account I sized you up, and I'm a fella that can judge character quicker than a wink. Now you're pretty smart. A pretty smart fella wouldn't go and shoot somebody just to get a rock pile and a shack and three no-good cows and a horse with the heaves. A pretty smart fella don't mind shootin' somebody now and again, but he wants to make something out of it."

"What are you in here for?" Tully inquired.

"For vagrancy and bein' drunk and disorderly and disturbin' the peace and firin' a gun inside the city limits and some other stuff like that. They handed me sixty days. But that don't make no difference, 'cause I think I'll leave tonight. This place ain't up to the standard of jails I'm used to."

"I suppose you're just going to walk out whenever you get ready?" Tully said skeptically.

"Oh, sure," said Rainy.

He thrust a long, skinny arm through the cell bars. His begrimed hand hovered over the lock, and there was a thin gleam of metal between his fingers. The lock snapped suddenly, and Rainy pushed the cell door open.

"You've got a key!" Tully exclaimed.

"Sure. Made it outta my belt buckle," Rainy said, closing the door and locking it again. "I was just waitin' until they brung my supper before I left. I escape from jails better on a full stomach. You wanta come along?"

Tully stared. "What?"

"I'm a fella that likes company. When I'm all alone, I'm liable to start talkin' to myself and convince myself of somethin'. And then you take and look at this reasonable. If you are Dave Tully, then they ain't got no slightest excuse for lockin' you up in jail for murderin' Dave Tully. If you ain't Dave Tully, then you damned well better get out of here and mighty quick.... Now don't get riled again. I was just presentin' you with some logic. I'm hell on logic. Took a correspondence course in it once. In a jail where they took my belt buckle away from me."

Tully came close to the cell door and gripped the bars, staring across at Rainy. "It wouldn't be healthy to play tricks on me, friend."

"No," Rainy admitted. "My logic already convinced me of that. I ain't foolin'. You can sort of trail along if you want."

"There are a couple of people around here I want to see," Tully told him grimly. "I didn't like some remarks that were passed about me."

"All right by me," said Rainy. "I'll just trot along and listen while you talk to 'em. I'm hell for listenin'. I listen even better than I talk, and that's sayin' a lot, ain't it? Now you just set quiet—"

The door into the outer office opened suddenly, and Elmer's eagerly gloating voice said: "Right this way. He's right in this cell. See? That's him—that's the killer. Ain't he a mean lookin' fella, though?"

The soft-looking, worried man with Elmer wore a cutaway coat and a flowered vest. He approached the cell gingerly, tip-toeing, and peered in through the bars with a sort of fascinated awe.

"Now, Pete York," said Elmer importantly. "Step up here. This here is Lawyer Carter, and he wants to talk with you."

"Huh-hello," said Carter in a timid croak. His round, pink face wrinkled like a baby's. "I d-don't like this! I d- don't know what to do! I'm not used to things like this!"

"Speak right up to him," Elmer advised. "He's a killer, all right, but I'm here to see he don't try no tricks."

Carter swallowed painfully. "Well, I—I'm the representative of Adelbert Tully's estate. I mean I'm appointed by the c-court to turn over his p-property to his nephew, David Tully...."

"Go ahead and turn it over," Tully invited. "I'm Dave Tully."

"Don't get sassy, you!" Elmer snarled. "You know you ain't nothin' but a dirty murderin' bushwhacker, and that your name is Pete York."

"Now, now," Carter pleaded anxiously. "I—I want to do right here. Young man, have you any p-proof that you're Dave Tully?"

Tully sighed. "Yes. It's in the jail office. Look at it."

"Hah!" Elmer barked. "Stuff he stole off that poor Dave Tully that he murdered in cold blood. That's his proof. Enough to hang him!"

"I d-don't like this!" Carter wailed. "I only want to do what's right. Young man, can't you identify yourself some other way? D-don't you know anyone in this country?"

"No."

"Couldn't you t-telegraph or—or—"

"Who?" Tully said. "And what would it prove?"

"I don't know!" Carter said, almost crying. "I'm only t-trying to do what's right. I want to t-turn over the property to David Tully, and I don't know who he is or who you are. It isn't right to put this burden on me! It isn't fair to give me this responsibility and hold me liable if I make a m-mistake!"

"Go away," said Tully.

"You see?" said Elmer. "You hear that? That's the kind of a hairpin he is! Don't care for nothin'. Defiant. Oh, he's a killer, all right!"

Carter said helplessly, "I can't d-do anything until I know...."

"Do it somewhere else," said Tully.

"Not another word outta you!" Elmer warned sharply. "Come along, Carter! Leave this-here killer to stew in his own juice!"

Carter tottered along the corridor beside him, and they went back into the jail office and closed the door.

Rainy had been peering interestedly through his cell door. "You know," he said conversationally, "I never in my life seen a guy talk so much about bein' honest as that Lawyer Carter. It sure worries him a lot, and I wonder if maybe he ain't got some reason to worry about it."

"Do you think he's crooked?" Tully asked.

"Well, now," said Rainy. "Once I heard of a lawyer that was honest. Mind you, I never seen such a party. But for all I know, there may be an honest lawyer somewhere. If there is, he keeps himself well hid." He reached through the cell door, and his hand slid across the lock. "It don't look like they're gonna feed us, and anyway the grub ain't such-a-much around here. I think I'll be leavin'."

He pushed his own door open and leaned casually against the front of Tully's cell.

"Get a move on!" said Tully.

"Now listen," Rainy advised. "Just simmer down. That's the whole secret of jail-breakin'. Take it easy. Don't go hollerin' and yellin' and bustin' down walls and filin' bars and like that. Just stroll along like you was goin' out for a drink or somewhat. I can't unlock your door because my belt buckle key won't fit it. I'll just go and fetch your key from Elmer. Sit quiet."

He went down the corridor as silently as a shadow. The jail office door opened an inch at a time without the faintest sound, and he crouched there, peering through. After what seemed an hour, he suddenly opened the door wide and slipped inside.

Tully listened, holding his breath. There was a little grunt and a scuffling sound and then complete, dead silence. Tully felt the sweat coming out on his forehead.

Rainy came back into the corridor, jingling a bunch of keys in his hand, whistling softly and contentedly. He found the one that fitted, and opened the door.

"Step right out."

Tully stepped into the corridor, drawing a long, deep breath.

"Come along," said Rainy. "Let's go see Elmer."

He led the way back up the corridor and into the jail office. Elmer was sitting in his chair with a lariat wound around him until he looked like a bulky caterpillar. There was a red bandana poked into his mouth, and above it his eyes bulged at them in awful, fascinated horror.

"His eyes ain't really gonna pop clear out, I don't think," Rainy said.

"Maybe they would," Tully said, "if I put my fingers in the corners and sort of urged a little bit."

Elmer made muffled, mouthing noises. His face and shiny head turned queerly greenish.

"Maybe so," said Rainy. "Try it."

Elmer moaned and then slumped in his chair.

Rainy chuckled. "Man, you sure sounded mean. Get your stuff over there in the cupboard. I already got mine." Tully found his possessions, including the money-belt, in the cupboard and his carbine in the rack behind one of the desks. He tried the action.

"Where's your belt gun?" Rainy inquired.

"Never use one. Don't like 'em."

"He don't like 'em," Rainy repeated, awed. Then he shook his head. "Man, what if your horse dumped you somewhere in the middle of nowhere when you was carryin' that carbine in the saddle scabbard?"

"No horse dumps me."

"Listen," said Rainy, "I never seen a man yet that didn't get himself dumped now and then."

"You're lookin' at one now."

"You're Dave Tully, all right," said Rainy. "Zip Tully was loco, and I can see it runs in the family. We better sort of mosey before the sheriff turns up. I'd just as soon not meet up with him."

"Why not?"

"Don't let that-there dumb look of his fool you. He's had medicine. You notice he carries two guns? He ain't doin' that just for fun. He ain't very smart, but he's fast."

"They said they were going to take my horse to the corral."

Rainy nodded. "Down back of the Lone O Stable. I ain't got no horse, but I suspect I can find one down there that'll do for now. Come on."

THE mountain night was like black velvet, and the air felt cool and tingling after the closeness of the jail. Lights burned, warm and yellow, behind windows and shadows streaked the street. They passed three men walking in the first block, and Rainy said: "Howdy," gravely and politely to each one. They all answered casually.

"See that?" Rainy said to Tully. "Just like I said. Act like you're mindin' your own business and nobody pays you any attention. That's the secret of my success. I give it to you free for nothin'."

"Thanks," said Tully.

Rainy stopped in front of the narrow, dark mouth of an alley. "Here," he said. He looked quickly up and down the street and then ducked back out of sight.

Tully followed him along the darkness between two buildings, weeds rustling and scraping against his legs.

"Pole fence here," Rainy whispered.

Tully felt ahead blindly, and his hand struck a peeled log. A horse snorted.

"I dunno whether your horse is in here or in one of the stalls inside," Rainy said.

"In here," said Tully. "The one that just snorted. Now, if I can find a rope, I can get him."

"How you gonna rope a horse in the dark?"

"I'll just heave it at him. If it hits him anywhere, he'll stop and stand."

"Smart horse," Rainy commented.

"Naw. He's dumb. He thinks if a rope touches him anywhere, he's caught. Where can I find a rope?"

Rainy guided Tully toward the saddle room of the stable. Inside hoof-trodden dust was soft and noiseless under their boots.

They stepped through the big door and into the warm closeness of the stable. A horse stamped, and the sound echoed hollowly.

The front entrance of the stable made a square of light ahead of them. There was a lantern on the ground just outside it, and men were dim, hunched shapes squatting around it.

"Here's the door of the dickey room," Rainy said in a cautious whisper. "But it's padlocked. Look—there's a bay mare in the first stall over there. I been meanin' to steal her for quite some time. She's a lulu, but she's skittish. Sneak up and slap her on the rump. She'll jump around and make enough noise to cover me. Them men won't pay no attention."

Tully stepped forward and leaned over the high sidewall of the stall. He slapped out and down with his hand, and his palm hit a sleek flank. The horse snorted and stamped indignantly, lunging against the other side of the stall.

"Got it," Rainy murmured, and Tully felt his way back to him cautiously.

"Pried off the hasp," Rainy said. "Come on inside. Careful with your heels. There's a board floor."

Tully felt his way past him into the thick, leather-smelling, narrow room. As the door closed, Rainy snapped a match on his thumbnail and then hid its flame between cupped palms.

"All right," said Tully. "I see my gear. Saddle bags, blanket roll, saddle, and rope."

"There's mine, too," said Rainy. "That fancy one with the silver doo-dads. I always wanted a saddle like that."

He blew out the match, and they moved cautiously in the pitch-darkness out into the stable.

"Don't fall over your feet," Rainy said.

"Don't let that mare stomp you to death."

"Say, listen," Rainy muttered. "I stole more horses than you ever saw."

Tully slid out into the open behind the stable, and slid his hands along the peeled logs until he found the corral gate. Dropping his gear on the ground, he slipped through, when he flipped his lariat out blindly ahead of him.

The horses milled and stamped, and one of them snorted loudly. Tully instantly reeled in the lariat and flipped it hard in that direction. The rope hit something before it fell to the ground.

Tully walked up on it carefully. "Whoa, boy," he whispered. "Easy, now." He ran into the side of the roan and caught its mane. "Easy."

The roan was a docile animal, but Tully had always figured that this was not because it was good-tempered or affectionate but because it was lazy. It was a good horse, though, especially considering he hadn't paid anything for it. He had won it in a poker game.

He walked it back to the gate, slipped on the bridle and saddled it, working silently and expertly. There came the soft thud of hoofs in the dust.

Rainy muttered: "Hell's fire, ain't you ready yet? You ain't never gonna make a success as a horse thief if you can't work faster'n that!"

"All set," said Tully.

"We'll go back out the alley the way we come. No way to get outta this town except by the main street. Say, there's a fella you know squattin' out in the front of the stable. Wears a pink shirt and a white hat and a pearl-handled gun and answers to the name of Bert."

"I want to see him," said Tully, his voice flat-toned.

"You're soundin' mean again. I swear, you remind me of Zip Tully more all the time. We better just mosey along before somebody finds Elmer."

"I want to see Bert."

Rainy sighed. "All right. Don't get up on your ear. You sneak through the stable. I'll lead the horses through the alley and come around in front the other way. There's four fellas out there."

Tully handed him the reins of the roan.

Rainy said: "Wait. Where's that short rifle of yours?"

"Right with me," said Tully, reaching back with his right hand and freeing the carbine. "I only carry it here in case I might want it quick and got both hands full."

"You got the most surprisin' ways of doin' things," said Rainy. "I swear I never see the like. Take it easy."

Tully went back into the gloom of the stable and soft-footed between the double row of stalls, heading toward the lighted square of the front door.

The mutter of men's voices grew louder as he approached. Four of them were sitting on upturned boxes around the smoky lantern.

Bert was talking. "... Sure. We figured it that way. Sheriff Fellows went ahead and spotted the bird, and then he signaled us and we circled back around in front of him. Then Ed and me blocked the road and hollered at the fella. He run back just like we thought, and Sheriff Fellows nailed him."

Another said: "What if he hadn't run? What if he'd have blowed at you? What then?"

Bert managed to swagger even sitting down. "Well, you fellas have seen me shoot, I guess. You toss a tin can in the air, and I hit it six times before it hits the ground. But these-here bushwhackers, they're scared to stand up and shoot it out...." His voice trailed off and his white, wizened face seemed to lengthen as his mouth dropped open.

"Go ahead," Tully invited. "Mighty interestin' story you're tellin'."

He was standing just at the edge of the lantern light, the carbine barrel slanted over his left arm. He had his thumb on the hammer and his finger on the trigger, but the muzzle was pointed at the ground.

Bert gulped. "How—how—?"

"You didn't think I'd stay in that squirrel cage jail, did you?" Tully asked, surprised. "I just let you arrest me and bring me along on account of I was comin' this way, anyway. But what were these remarks you were makin' about bushwhackers bein' scared and all that?"

There was a little stir in the darkness, and then Rainy's voice said conversationally:

"That fella in the black shirt is gettin' nervous-like, Dave. He's got a gun, and I bet he wants to pull it out and let it off. He can if he wants to, can't he?"

Tully nodded at the man. "Go right ahead, mister."

Black Shirt froze, rigid. Then very slowly he raised both hands, palms out. "I don't wanna," he said hoarsely.

Tully looked back at Bert. "You pull your gun. I mean it."

Bert's skinny hand inched down gingerly toward the pearl handle of his revolver.

"That's right," Tully commended. "Pull it out slow and keep the muzzle to the ground."

Bert drew it that way, one shoulder hunched up, his face twisted into a stiff grimace.

"Now," said Tully. "Let's see if you're fast. Just tip her up and let go any time. You give the word." Tully's carbine was still slanted casually over his arm.

Bert's breath made a whistling sound. He began to shake all over, and then suddenly the revolver slid out of his fingers and thudded into the dust. Bert whimpered a little.

Tully looked at the man in the black shirt. "You wanna try it?"

"No," said the man quickly.

"Got a rope, Rainy?" Tully asked.

"Here," said Rainy. The lariat sailed out of the darkness and thumped down in a loose, snaky coil beside the lantern.

Tully nodded at Bert. "Start tyin' this gent with the black shirt. Lie down, you."

Black Shirt sprawled out awkwardly on the ground. Bert picked up the lariat with fumbling fingers and started to rope his feet together.

"Tight," Tully warned. "Hands behind him. Careful of those knots. Rainy, are you watchin' the street?"

"Naw," said Rainy. "I'm takin a siesta."

Bert's voice quavered. "I—I ain't got a knife to cut the rope...."

There was a light thud in the darkness, and a horn-handled pocket knife was trembled in the stable wall just over Bert's head. He ducked down, wincing.

"If I'd meant to hit you, you wouldn't be jumpin'," said Rainy. "Hurry up."

Bert sawed through the rope. Tully moved his carbine meaningly, and without any more command than that the other two men hunkered down in the dust. Bert tied them up, panting with his efforts.

"Tote 'em back inside the stable," Tully ordered.

Bert panted and heaved and hauled at his companions, dragging them back between the stalls. He straightened finally, staring fearfully at Tully.

"W-what you gonna do with—with me?"

"This," said Tully.

He shifted his carbine to his left hand and his right fist came up and over in a swift arc. There was a sharp splat of his knuckles and Bert's feet raised off the ground six inches. He came down flat on his back, arms outspread. He didn't move. He didn't even groan.

"Don't forget my knife," Rainy warned from the doorway. "I paid five dollars for that knife, and I only had it for twenty years now."

Tully picked it up out of the dust and tossed it to him.

"You plannin' on makin' this stable your permanent home?" Rainy inquired. "I had an idea we started out to escape from jail or something."

"In a minute," said Tully. He nodded at the bound men. "Which one of you is the hostler?"

"M-me," said one of them.

"Where's your coal oil?"

The man swallowed. "What? You ain't—ain't—?"

Tully moved his carbine.

"It's in—in the store-room. Over there."

In the store-room, Tully located the red can and a bucket. Carefully he poured some of the oil into the bucket and then found a broom and sloshed it in the coal oil. He came back to the bound men carrying the dripping broom. They stared from it to him with bulging eyes. Their jaws hung open.

"Me an' my pardner are gonna step outside now and close the front door," Tully told them. "I'm taking this broom with me. We've got some errands to do around here before we leave and we don't want to be bothered. If any one of you start hollerin' before we're gone, I'm gonna light this broom and heave it up into the hay-mow. Maybe somebody'd come along in time to get you out, and maybe they wouldn't. If you feel lucky, start hollerin'."

He backed out of the stable and swung the big front doors shut. He put the lantern down in the dust where it had been before and threw the broom carelessly aside.

"Want this?" he asked, picking up Bert's pearl-handled gun.

"Naw," said Rainy. "I outgrew stuff like that when I quit wearin' short pants.... You just made yourself a bad enemy there, Dave. That Bert is one of them scared fellas that's too scared to admit he's scared, even to himself. That kind of a fella can't stand to look foolish. He'll start poppin' and steamin' and frothin' at the mouth just like a hydrophobic skunk You wanta watch out for him, Dave. He'll gun you sure as I'm a liar."

"Maybe," said Tully, tossing the pearl-handled gun into the weeds beside the building. "Ready to go?"

"Oh, no," said Rainy. "No. Let's stick around for a couple more hours."

Tully swung up on the roan. "You lead the way."

They jogged through the dark, shifting shadows of the main street, and the horses' hoofs drummed across the first wooden bridge and then the second.

Rainy indicated the lighted windows up the slope of the canyon on either side of them. "Look at all them folks feedin' their faces, and me hungry as a lobo wolf. It just goes to show you that honesty is the best policy. If it pays."

They were crossing the third and last bridge when there was a sudden weird metallic clamor that echoed a re-echoed deafeningly between the canyon walls. Doors banged open and men shouted hoarse questions.

"That's all for us," said Rainy calmly. "Sheriff Fellows come back from dinner and found Elmer. We better just lollop along a bit now."

He spurred the bay, and the horse broke into a lunging, impatient gallop. Tully's roan hammered along beside it. The wind blew crisp in their faces, and the night seemed to close around them protectively.

A mile down the road, Rainy suddenly flipped his hand warningly and then pulled up. Tully slid the roan to a halt beside him.

"We turn off here," said Rainy. "That horse of yours any good at climbin'?"

"I don't know. I never tried him."

"You'll find out," said Rainy.

He turned at right angles off the road. There was a thick wall of dried brush here, and it scraped and dragged at Tully's legs as the roan smashed through it. The ground sloped up steeply, and a branch whipped him across one cheek bringing involuntary tears to his eyes.

From ahead Rainy said: "We're goin' up now. It's steep, and there's loose shale. Watch yourself."

The darkness was impenetrable. Tully heard the bay mare grunt in protest, and then rocks slid and clattered softly. He spurred the roan, and the horse went forward willingly, heaving up in hopping lunges, scrambling desperately for footing. Rocks rolled treacherously, and twice the roan slid back almost on its haunches as Tully threw his weight forward in the saddle to help.

They came up on level ground suddenly, and the roan snorted in protest and moved its feet in gingerly uneasy little half-steps.

"There's a ledge here," Rainy said. "Follow along behind me. Keep your leg against the rock. It's a long ways down."

The roan edged forward under Tully, and his leg scraped against the sheer rock face. They went endlessly along in the blackness with the roan cat-footing.

"Up again here," said Rainy. "Not so steep."

The roan gathered itself and lunged. They went up in hard, thudding crow-hops, up and into the clear. The sky was an endless dome pressing close and soft above them.

Rainy chuckled. "Your horse can climb, all right. The posse won't follow us up here. They'll go boilin' right on down the road to try to cut us off at the railroad junction and the cross-road to Crater Valley.

"They built a narrow-gauge to haul ore from the Goliath Mine," Rainy continued. "They ain't workin' the mine now, but I reckon they figure on openin' it up again sometime, because they're holdin' their right-of-way—runnin' a couple cars through twice a week. Whole thing belongs to the Blaisdell-Bell outfit. They got mines in every part of the world. You heard of the B and B Mining Company, ain't you?"

"No," said Tully.

"Well, you ain't been around much, then. They're the biggest outfit in the world I guess. Your Uncle Zip used to work for 'em, or so he said."

"He was liable to say anything, according to my dad," Tully observed. "My dad said he was the biggest liar that was ever born."

"Nope," said Rainy. "I am. But Zip could do pretty well, I got to admit. Him with his stories about Death Valley and Australia and South Africa and all that. He ever tell you anything like that?"

"I don't remember. I told you I was only ten years old the only time I ever saw him."

"Yeah. What you figurin' on doin' now?"

Tully said: "I came to get my property, and I'm going to get it. I'm gonna lay low somewhere for a couple of weeks and wait until Sheriff Sloan comes to get me. He'll identify me."

"Where you figurin' on doin' this layin' low?"

Rainy was a shadowy, hunched figure with his beard making a weirdly elongated square of his face.

Tully watched him narrowly and then said: "Now, I'm grateful to you for gettin' me out of that jail. But you did it of your own free will, and right now it seems to me you're acting awful curious. Just how is it that you know so much about this country if you're a stranger here—this cut-off trail and all that?"

"Mister, I never yet went into a country without first locatin' the back-way out and a few hidey-holes here and there. That's how come I've lived so long.

"Dave, I come up to this country because there's people like sheriffs and marshals and like that sort of lookin' for me here and there, and I wanted a place to sort of rest up for awhile. It wouldn't be too good for me to go movin' around fast and fancy right now, so suppose I show you a nice little place to sit for awhile?"

"Then what?" Tully asked warily.

Rainy spread his hands. "Nothin' at all. Just when you get identified and all that, you sort of tell the sheriff that I'm an old friend of yours. Sheriff Fellows is gonna feel pretty red in the ears when he finds out you really are Dave Tully like you told him all the time, and he's gonna want to do you a favor.

"Suppose you tell him you'd like for him to forget my jail sentence and play like I ain't hangin' around here. You could tell him, too, that I just sort of borrowed this horse and saddle temporary-like—meanin' to return it and pay the owner rent, and all that."

"Well, I'll tell him. I don't know whether he'll believe me or not, though. I wouldn't, if I were him."

"You ain't, though. He's dumb. Let's go, then. We head right along the top of the ridge here for about five miles. Just keep right behind me."

"Where we goin'?" Tully demanded.

"To see some friends of mine. Come on."

RAINY pulled up the bay, and his skinny arm made a straight, shadowy bar in the darkness, pointing down and ahead of them.

"See it?"

There was a window like a bright, jewel-size square sparkling in the night far below them.

"That's where we're goin'," Rainy added. "Little place that belongs to a fella by the name of Dan Lawson. You'll like him."

"Yeah," said Tully. "But will he like me? Don't seem to me like I'm such good company to have callin' on you right at the minute. Nor you, either."

"Dan won't mind... much," said Rainy.

They rode down a long gradual slope to the floor of the valley, and tall grass swished slickly against the legs of the horses. The window crawled closer, and they could see the low, shadowy outlines of the house and the indistinct blur of corral and ranch buildings back and to one side.

"Dan!" Rainy shouted. "Oh, Dan! Open up!"

An opening door made a sudden lighted outline beside the window, and a man loomed up in it, tall, bearded and darkly gaunt.

"Who's there?"

"It's Rainy, Dan." He swung off his horse and said to Tully: "Tie your horse to the rail. We won't be stayin' long."

"There's a fella layin' out behind the corral," Tully said softly. "I saw his gun barrel glint."

"That's just Laury," Rainy said. "It don't matter. Come on."

The man stood waiting for them silently and somberly in the open door. He was wearing a long six-shooter in a cross-draw holster, and he kept his hand on its butt, leaning forward to peer into the darkness.

"Friend of mine, Dan," Rainy said. "Name of Dave Tully."

"Howdy?" said Tully.

Dan Lawson didn't answer. He stood still, blocking the door, neck crooked forward at an ugly angle.

"Back up, Dan," Rainy said. "We're comin' in and set, since you was so kind to ask us."

The man backed up reluctantly. In the lamplight his face was thin and cut deep with wrinkles, and his eyes were bleakly bitter.

"Thought you was in jail, Rainy," he said.

"Got sort of tired of it. Wasn't no social life."

"You escaped," said Lawson.

"Why, no," said Rainy. "They let me out for recess."

Lawson jerked his head. "He escape, too?"

"You're gettin' fussy in your old age," Rainy said. "We'll sit down."

Tully side-stepped quickly away from the open door, leveling the carbine. "Tell him to call in his stake-out first."

Lawson swung his head to glare at him, and muscles made quivering lumps along his jaw beneath the gray beard.

"Better do like he says, Dan," Rainy advised, seating himself comfortably in a raw-hide bottomed chair. "He's liable to get nervous if he's crossed."

Lawson glared at Tully for a moment more and then stepped to the door and shouted: "Laury! Come on in!"

Heels made light, quick thuds on the hard ground, and a girl stepped quickly through the door. She was tall and slim and full-breasted, and she was wearing riding jeans and a man's blue work shirt. Her hair was black and sleek, done in a knot low on the back of her neck. She smiled at Rainy with a sudden flash of white teeth.

"Hello, Rainy, you old devil," she greeted cheerfully. She was carrying a long-barreled rifle, and she leaned it against the wall beside the door. "What're you up to now?"

"Not a thing," said Rainy. "Just sittin' and restin' my poor, weary bones and lettin' your pa give me dirty looks. This here is a friend of mine, Laury. Name of Dave Tully. You made him right nervous sneakin' around and pointin' rifles at us."

Laury looked at Tully and nodded, smiling. "Hello. A friend of Rainy's is a friend of ours. Don't mind pa. He's feelin' sour because he got beat out on a horse trade last week."

"They got the law behind them," Dan Lawson said sullenly. "Rainy's got no right to bring the law around here. I don't want people lookin' too close at me."

"Pa heard you were in jail again," Laury said to Rainy. "For bein' drunk and disorderly."

"That's what they tell me," Rainy admitted cheerfully. "I don't recall much about it, myself. Me an' my pardner busted out together."

She turned to Tully. "What did they have you in for?" she asked frankly.

"Murder," said Tully.

There was a thick little silence in the room. Laury wasn't smiling any more, and she looked at Rainy inquiringly He nodded.

"In a gun-fight?" Laury said slowly.

"Nope," said Rainy. "He bushwhacked a fella, is what they say."

Dan Lawson made a choking sound in his throat. "You got no right to bring him in here! Get him out! Right now!"

"Take another dally, Dan," Rainy advised. "He ain't guilty."

"Of course he says that!" Dan Lawson cried furiously. "You don't think he'd admit he was guilty, do you? Get him out of here! You want to put us all in prison?"

"I didn't ask to come," said Tully. "And I don't care about stayin'."

Laury made a little motion with her hand toward her father. "Pa! Be quiet, now. Rainy'll tell us plenty about this."

"Sure," said Rainy. "It's kinda complicated-like. It seems that Dave, here, is a nephew of old Zip Tully."

"Zip Tully!" Laury exclaimed, making a disgusted face. "I saw a gila monster once, down south, and that's just what he reminded me of."

"My Uncle Zip don't seem to be any more popular than I am around here," Tully observed. "I guess maybe I'm glad I didn't know him any better."

Laury shivered. "Oh, he was awful! Dirty and—and a liar. And worse!"

"Fact," Rainy agreed. "Anyway, it seems like he left his property to Dave."

"Why, he hasn't got any property," Laury said. "Just that old shack and a half-section of rock piles."

"Yeah," said Rainy, "but Dave didn't know that, so he come along to see what he inherited, and Sheriff Fellows went and grabbed him and put him in jail for murder."

"Who was he supposed to have murdered?" Laury asked.

"Himself," said Rainy. "Seems like Fellows got a telegram from Sheriff Sloan, back where Dave comes from, sayin' that somebody had murdered Dave Tully and was pretendin' to be him."

Laury stared. "Well, are you Dave Tully?"

"Yes," said Tully. "And I'm not dead. And I didn't shoot myself or bury myself, either. This is just a dumb mistake Sloan made. Probably somebody did get murdered and buried, but it wasn't me. Anyway, I'm not going to sit in jail and wait while they unsnarl things. I don't like that jail. And now that I'm here I'm going to get the property I inherited, even if it ain't worth a dime."

"He's stubborn," Rainy commented admiringly. "And when he gets his back up, he can get mean quick."

"I'd get mad, too," said Laury.

"Laury!" Dan Lawson shouted. "Are you crazy? We ain't gonna have nothin' to do with this fella, nor Rainy, neither! Get out—both of you! Get off my place!"

"Dan," said Rainy softly, "you go to hollerin' like that and I'm liable to start hollerin' myself—only not here and not at you. I'm liable to start hollerin' about horses and cows with funny brands on 'em."

Dan Lawson's hand flipped across toward his six-gun.

"Now, Dan," said Rainy, not moving. "I wouldn't do that, was I you."

"Pa!" Laury said sharply.

Dan Lawson stood rigid, and then finally he relaxed a little.

"Pa," said Laury, "Rainy's our friend! He wouldn't bring anybody here that wasn't all right."

"I don't like it," said Dan Lawson thickly. "If there's a murder charge on him, the law will be hot after him. And he ain't no ordinary puncher. He don't handle himself like one. He's too quick and ready with that gun, and he sees too much. He's done some shootin', and not jack-rabbits, neither."

"You should know, Dan," said Rainy. "And I think maybe you're right. How about that, Dave?"

Tully said: "There was a sheep war on the Solo a year back."

"Hell's fire, yes!" Rainy exclaimed. "The Solo sheep war! I remember that. Ten-twelve men killed. Was you in that?"

Tully nodded. "They came down from the Big Piney, and tried to graze across our range. Four big outfits with hired gun-slingers in front. Things sort of sizzled for awhile."

"Yeah," said Rainy. "I was in a sheep war—just one. I don't want no more of that. No wonder you walk easy and jump quick. You see, Dan?"

Dan Lawson nodded reluctantly. "But that don't mean the law ain't after him now."

"Never mind that," said Laury impatiently. "That'll be straightened out as soon as he gets identified. All he has to do is lay low until then. What do you want us to do to help you, Rainy?"

"I want your pa to get on a horse and lead another and start out for Beaudry. He can be goin' over there to do a little tradin'. I figure Sheriff Fellows will start circlin' back when he finds we didn't go through the junction, and he'll light on this place pretty soon when he does. I want you to stay here, Laury, and tell him your pa is away, and that me and Dave come in and then headed out for Beaudry. Fellows will see Dan's trail and follow it. That'll keep him busy for awhile."

"Where're you going?" Laury asked.

"Up in back of Table Rock Canyon. I spotted a nice place to camp up there. We'll just sit around and fish and whistle for awhile."

"I don't like it," said Dan Lawson.

"I don't recall askin' you whether you liked it or not," Rainy told him.

"We'll do it," said Laury. "Pa, you get ready to get started."

"And we could use a little food," said Rainy.

Laury laughed. "I'll get you something right now."

"Wait," said Tully. "I don't want you people gettin' in trouble on account of me. None of you know me, and that story of mine don't sound very reasonable. I'll just go along and cut my own trail."

"Trouble's done already," Dan Lawson said gruffly. "Might as well go through with it now. Laury, you pack me some grub. I'll go get the horses."

He stamped out the door.

Rainy grinned and winked at Tully. "That was the best thing you coulda said to him. If you'd asked him for help, he'd started snortin' and puffin', but as soon as you act uppity about it, why then he wants in. He's ornery."

"And he's my pa," said Laury.

"Sure," said Rainy quickly. "That's right. And that's a sure sign he must be a really fine fella at heart."

Laury laughed again. "Don't try to smooth me down, you old liar. I'll get you something to eat. You sit down and relax, Dave Tully. I told you any friend of Rainy's was a friend of ours. Pa's touchy, and Rainy rubs him wrong, but he'll go through for you now he's started. I'll fix you up some sandwiches to eat on the way. You better not hang around here any longer."

THE fire was like a sleepy red eye in the darkness, built in under the cut bank with a thick tangle of willows above it to keep its reflection off the rock face of the narrow canyon walls. Tully was lying beside it, rolled in his blankets, using one saddlebag for a pillow. He sat up suddenly now and reached for his carbine.

"Uh?" said Rainy sleepily. He was sitting on the other side of the fire, his back propped against a rock.

"Somebody coming," said Tully. "You hear anything?"

"Aw, you got nightmares," said Rainy.

Tully was listening with his head tilted. "You're a hell of a watchman. Hear that?"

Brush crackled thinly down-canyon.

Tully kicked free of his blankets and slid back into the dense shadow of the willows. "I'll cover you."

"See you do," said Rainy. He let his head drop forward drowsily again. Rocks rolled and clattered, and a horse wickered loudly.

"Rainy!" a voice called.

Rainy jerked his head. "Yeah! Here, Laury!"

A horse burst through the circle of brush, and Laury swung down from the saddle.

"Oh, I thought I'd never find you! Where's Dave Tully?"

"Here," Tully said, stepping out of the shadows.

Rainy chuckled. "He's the only man I ever seen that can snore and listen at the same time. He was sawin' logs like a lumber-jack, and still he heard you before I did. Anything the matter, Laury?"

She knelt down in front of the fire. "Yes. Sheriff Fellows came. He had eight men with him. I told him what you said, and he went off on pa's trail toward Beaudry."

"Well, that's all right, then," said Rainy.

"No! That's why I came!" Laury drew a deep breath. "He was so mad he could hardly talk straight."

"I suspected he would be a little irritated," Rainy admitted complacently, twisting a cigarette.

Laury made an impatient gesture. "Oh you don't understand! Rainy, he doesn't intend just to arrest Dave. He didn't say much, but I could tell by the way he acted and what he said to the other men that he'll kill Dave if he catches him."

"So?" said Rainy slowly.

"I got a little of the idea behind it. Rainy, nobody has ever escaped from his jail before—nobody. And you did it so easy. Just unlocking the doors and then tying up Elmer and scaring him half to death and taking the horses right out of the Lone O Stable and tying up those other men—then going back and forth right on the main street of Clearwater. It made Fellows look like a fool. And on top of that he had already telegraphed that other sheriff and said he had Dave. Rainy, he's so mad he's half crazy. He'll hunt Dave down now if it takes him a year!"

"He'll quit as soon as he finds out I'm really Dave Tully," Tully said.

"No, he won't! He doesn't care about that now. It's personal!"

Rainy tugged at his beard. "Yeah. Maybe you're right, at that. He's got kind of a reputation. I forgot that."

"Where'd he get his reputation?" Tully asked.

"Used to be an end-o' line troubleshooter for the U.P. Kept order in the boomtowns. I told you he wasn't no slouch. He got them two guns as a presentation for his good work. I suppose this business don't sit so good."

"He's got more men out looking for you," Laury said. "More than the eight, I mean. They'll cover all this country, Rainy. You can't stay here."

"Not if he really means business," Rainy agreed. "Maybe we better bust ourselves back into jail, Dave. I reckon I could handle it."

"No," said Tully. "I been choused around enough."

"He's gettin' mean again," Rainy said to Laury. "Can't do a thing with him when he gets that way."

Laury glared at him. "You had no business getting him out of jail, you old fool! Why didn't you leave him in there? Look at the trouble you've gotten him into!"

"Yes, ma'am," said Rainy weakly. "But he's kinda good company in spite of bein' mean. And I'm a poor lonesome old fella—"

"Stop that! This is no time to joke!"

"No," Rainy admitted. "It really ain't, I guess. Don't you worry, Laury. We'll pull up into the back range. Fellows can't find us there if he hunts for ten years. Ain't nobody up there but mountain goats."

"No," said Tully flatly and finally.

They both looked at him.

"No, I'm not goin' on the dodge just because somebody got murdered back on the Solo River. I didn't have anything to do with it, no matter what Sheriff Sloan says or Fellows thinks."

"What you gonna do, Dave?" Rainy asked.

"I'm gonna straighten this out. I don't know how yet, but I'm startin' now. I want to go down and see my Uncle Zip's place."

Rainy shook his head. "That's right back near town, Dave."

"I'm goin' there. Now!"

Rainy scratched his head. "I'm afraid he's kinda serious about that, Laury. When he gets his mean up, he takes sudden notions."

"But you can't!" Laury said.

Tully had started to roll up his blankets.

Rainy sighed and drew his six-shooter and spun the cylinder. "Come to think of it, that jail was a nice peaceful, place to set and think." He replaced the gun in his holster. "There ain't a particle of use in arguin' with him, Laury. He just won't pay no attention."

"You don't have to come along," Tully told him.

"Nope," said Rainy. "But I'm comin'. So now that makes me even dumber than you."

Tully nodded at Laury. "Thanks for ridin' up to warn us. I sure appreciate that, and all the rest you've done."

Laury glared at him furiously. "Oh! You—you're both fools!"

"Reckon a man could get himself elected governor on that platform," Rainy agreed gloomily. "You ride on home now, Laury. I got a notion Dave and me is goin' to be busy as a couple of bees in a beer barrel."

"There," said Rainy.

Tully squinted down and ahead in the darkness. "I can't see anything."

Rainy slapped the bay with the reins, and it began to pick its way down the steep slope. "We're comin' in from the back way. Ain't nobody here, I guess, or we'd heard 'em or seen 'em before this. I guess everybody else figured like me—that you wouldn't be loco enough to stay around here."

Tully let the roan follow down into a crooked gulch, and dried brush snagged at his legs.

"Look out for the rock piles you inherited," Rainy warned. "Shack's right ahead."

Tully could see the vague, squat loom of it now, pushed in close against the weathered rock face. It was built lopsided and helter-skelter, and the roof sagged wearily.

"Reckon Lawyer Carter musta give the animals to some neighbor to keep," Rainy observed. "Don't see 'em. You ain't missin' much if they're gone." He swung out of his saddle. "Come on. Might as well look at it all, now we're here. Tie your horse good. I ain't no walker."

Tully got off the roan and followed Rainy across the open space in front of the shack. Loose rock rolled and clattered under his boots.

Rainy kicked a can away from the sagging door-stoop. "Zip sure liked to live in luxury. Door ain't even shut, but I suppose there ain't anything in here anybody would want."

The hinges creaked as he pushed the door back, and the air that came out of the shack reeked of old tobacco and whiskey and cooking grease. Tully stepped inside, and the dirt on the floorboard grated under his heels.

There was a sudden dry, sibilant buzz that filled the whole shack.

"Stand still!" Rainy said sharply. "It's a rattler! Wait'll I strike a light. Don't shoot him!"

The match flame spurted in his fingers and he raised it above his head. The diamond-back was ten feet from the door directly in front of them, piled into a thick-muscled coil. The wedge-shaped head was back and up, ready.

"Open the door wide," Rainy ordered. "Get away from it."

Tully pulled the door back against the wall and stepped quickly aside, stumbling against the shadowy ruin of a chair. Rainy, still holding the match high, took one step and then another and, then thrust his boot out, sole up, straight at the snake.

There was a flick that was too fast for the eye to follow and a thud as the snake struck the boot sole. Rainy came over and down and stamped his heel hard on the snake's head before it could whip back into its coil. There was a sickening, hollow crunch. Rainy put the toe of his boot under the thick body and kicked it writhing through the door.

"Huh!" Tully exclaimed, releasing his breath. "I wouldn't do that for five hundred gold!"

"It was probably just a friend of your uncle's," Rainy said. He raised the match again, shielding it with his palms. "Now you can take a look around and see the beautiful estate—"

It happened very fast then. Tully slapped at his hands and the light snuffed out.

All in the same motion, Tully swung his carbine around and fired at the window at the end of the room. The .44 made a flat crash that seemed to move all the air in the room.

Tully flicked the lever and fired again instantly, shooting at the thin board wall below the window this time. There was an agonized scream outside the window and the crackling thrash of brush. Tully jumped for the window. He slammed into a bed, and dust came up into his nose in a thick, stinging cloud.

He kicked his way clear, flipped the carbine around butt-foremost and smashed the glass out of the window. He thrust the barrel through the opening. Rock moved and clicked up the slope. Someone fell with a breathless grunt and got up again, and then Tully caught the vague outline of his figure against the sky. He fired three times faster than a man could count.

There was another sobbing cry that cut itself off in mid-note, and something fell and caught and then rolled again in a little avalanche that clattered rock against the shack. Tully whirled and made for the door. Rainy was out of it ahead of him, six-shooter tilted in his hand. They stayed flat against the warped wall of the shack.

"More'n one?" Rainy breathed.

"I don't think so. I just spotted his face when you lifted the match. He had his gun all aimed."

They waited while the night seemed to settle slowly back in its place. One of the horses moved uneasily, but there was no other sound.

Rainy began to slide along the wall, and Tully followed him cautiously. They reached the corner of the shack and stopped and listened again. After a while, Rainy went on around the angle and circled out a little bit.

"Here," he said. "I'm gonna strike another light."

"All right."

The match snapped and flared. The man called Bert was lying almost exactly in the same position as he had been after Tully had hit him in the livery stable. He was flat on his back with his arms flung wide, but he wouldn't get up again this time. The pink of his shirt was changing into a thick soggy red, and his eyes stared wide and sightless.

"You sure beefed him," Rainy said. "He wasn't no good, Dave, but he was a deputy. Now we're in up to our ears."

Rainy blew out the match. "He figured you'd come here sooner or later if you wasn't caught, and he'd have laid here a month to pay you back. He's that kind. It's as nice a case of self-defense as I ever see, but how you gonna prove it?"

Tully didn't answer.

Rainy squinted, trying to see his face. "What you gonna do now, Dave?"

"Go into town and see Lawyer Carter."

"Tonight?" Rainy asked incredulously. "Right into town?"

Tully took some cartridges from his pocket and began to push them through the loading gate of the Winchester. "Yeah. Right into town. Tonight."

THE tangled clump of willows hung over the canyon edge like a wig slipped sideways, roots of the stunted trees hooked in the crevices like gnarled fingers. Tully and Rainy were on foot now, crouched close in the darkness.

The peaked roof of the house was just below them—a slanted shadow in the night.

"No lights inside," Tully said. "Is he married?"

"Naw," said Rainy. "He's an old maid. Got a housekeeper, but she don't stay on the place."

"Let's go."

Tully began to slide downward, holding to the willows, hooking his heels hard in the scanty soil. He dropped with a light thud close to the wall of the house, and Rainy came down noiselessly beside him.

"Let's try the doors first," Tully suggested.

"Ain't no use. He's got bolts on 'em. Lemme work on this window."

There was a slight squeak as his pocketknife blade worked between the sashes of the window. Metal grated against metal.

"Get it?" Tully asked.

"Yeah. Wait." Wood creaked in protest, and then the window began to rise silently an inch at a time.

"I think this here is his office inside," Rainy said. "He works at home sometimes. If it is, there's a desk right here."

Tully heaved himself up and ducked silently through the window. The air in the room was musty and thick, still carrying some of the day's heat. Tully's fingers rustled among loose papers.

Rainy came catlike through the window. "This is the office," he whispered, "and the door's over here."

Tully followed him and the opening door moved the air slightly.

They heard the snoring, then. It sounded like the person who was doing it really meant it. Each snore began low on the scale and went on up and up and then ended in a gurgling pleased wheeze.

"Man alive!" said Rainy. "There's a fella that can beat you all hollow."

They went quietly along the hall and then up a carpeted flight of stairs. The snores were coming from the first room at the right in the upper hallway. They went through the door into the darkness of the bedroom. The snores went on undisturbed.

"Pull down the shade," Tully ordered. "We got to have a light."

The window shades rustled, and then Tully struck a match and lighted the glass-chimneyed lamp on a stand beside the head of the bed.

Carter was lying in the middle of the bed on his back with his mouth wide open. When the light hit his face, he rolled his head back and forth uneasily and mumbled. Tully poked him lightly with the carbine barrel.

"Go 'way," said Carter, eyes shut tight. "Ain't time.... Huh? Huh?"

Tully poked him again. Carter sat bolt upright suddenly. He was wearing a tent-like white nightshirt, and looked more than ever like an over-sized baby. His round, soft face went paper-white, and he stared at Tully unbelievingly.

"Wha-wha-wha—?"

"Keep your voice down," Tully warned.

"O-o-o-oh!" Carter moaned, letting out all his breath. He gasped and choked, one hand up to his throat. "D-don't, please, shoot me! I—I didn't d-do any thing...."

Tully sat down on the edge of the bed. "I want to talk to you for a minute. How much legal work have you done for my Uncle Zip?"

"You mean Adelbert T-Tully? None—before this. And, oh, I'm not going to do any more! No, no! I t-try to do what's right and—"

"How come you're handling his estate?"

Carter swallowed. "Well, I'm the only lawyer in t-town."

Tully nodded. "I see. Now I want to know just what that estate consists of. Are you gonna tell me or not?"

"Yes!" said Carter quickly. "B-but there's just that half-section of land north of town and the shack on it. Three cows and a calf and a horse."

"What's the land worth?"

"Practically nothing. It's no good for grazing, and you couldn't raise anything on it. There's a spring, but it's not very big, and in the summer it d-dries up. I've got an offer for it, though, if—if you're Dave Tully."

"How much?" Tully said sharply.

"Two hundred and fifty dollars. Mr. Bogan's offer was r-really quite generous."

"Bogan," Tully said thoughtfully. "Isn't he the telegraph operator?"

Rainy was leaning against the wall beside the door. "Yeah. An' the narrow-gauge station master at the junction, too. A private leased wire runs along the tracks, but the B and B Company always took messages for Clearwater on it."

Tully's eyes narrowed. "Things are gettin' just a little clearer now. You remember I said that Sheriff Sloan made a dumb mistake? Now I don't think he did. I don't think there was anybody murdered on the Solo River, and I don't think Sheriff Sloan sent any telegrams sayin' there was, or sayin' that it was me."

Rainy grinned. "Huh! You mean, you think that Bogan just faked all that?"

"Sure. It'd be easy for him. He could find out my name and where I came from by talkin' to Carter, here, and then he could easy find out that Sloan was the sheriff there and write out any kind of a message and tell Sheriff Fellows that it came from Sloan."

"Hell's fire!" said Rainy. "Sure, he could."

Carter was staring from one to the other. "I—I don't understand.... B-but you two escaped from jail, and that's not right. No, it isn't. You—you ought to go back. Then, if you're really Dave Tully, I'll d-do all I can...."

Rainy ignored him. "Why you figure he did all this high- flyin'?"

Tully shrugged. "I dunno. I think it must have something to do with that railroad. I think they must be goin' to extend the line, and he knows where. It don't make any difference. We'll just go ask him and find out for sure."

"What?" said Carter uneasily. "Wh-what are you planning...."

"We're going to wrap you up in a bundle," Tully told him. "We're going to wind you right up in your sheet, just so you won't go hollering around."

"Oh, no!" Carter wailed. "You m-mustn't do that! I—I've got a weak heart and—and—"

Tully jerked the sheet off him in one backward heave. "Rip this into strips, Rainy. Sit still and shut up, Carter. I got no time to fool with you."

The station was square and solid and dark, built flush with the slick double gleam of the narrow gauge tracks. There was a pile of ties fifty yards down-track from it, and Tully and Rainy came quietly up into the shadow of that. They had left their horses in a grove across the junction road.

"No lights," said Tully. "You sure Bogan sleeps in the station?"

"Yup," said Rainy. "That way he don't have to pay no room rent. He ain't a man to throw his money around. We better get movin'."

Tully slipped around the end of the ties and ran with short, light steps for the station, hunched low, swinging his carbine in his right hand. He flattened himself against the station wall and watched Rainy duck across the open space after him.

Rainy was breathing hard. "I told you I ain't no walker, and I sure ain't no runner, neither. I got a blister on my heel big as a dollar."

Tully slid along the wall to the door. The big knob was cold and smooth under his palm, and it turned easily, without noise. He pushed the door open slowly, keeping back against the wall. There was no sound from inside the station.

Rainy breathed against Tully's ear. "He sleeps in a little closer to the left of the ticket window."

Tully nodded. He stepped into the station and felt the movement of the boards under his feet as Rainy followed close behind him. Single file they crept diagonally across the room, and then Tully reached out and felt the panels of a closed door ahead of him. He let his fingers drift downward until they caught the latch.

There was a tiny click as it came up, and they waited there, tense and not breathing. Then Tully began to push the door back very gently. He could catch only the barest outline of the room inside and the lighter square of a window directly ahead. The narrow bed was to his right, just far enough back to clear the door.

Tully stepped closer to it—one long, cat-like stride and then another. He was directly above it now, and there was a dim figure rolled up in the tangle of blankets and the white shine of a face.

Rainy's fingers dug hard into his shoulder. "The guy ain't breathin'!"

Tully slid his hand into his pocket and brought out a match. He snapped the head on his thumbnail, and the flame spurted.

"Huh!" said Rainy.

Bogan lay on his side, twisted and curled like some crushed insect, and his whole face was black with powder burn. The bullet had hit him just above the cheekbone. His pillow was stiff with clotted blood.

Tully moved the match a little, and the flame glinted back from the thick spectacles lying on the chair beside the head of the bed.

Then something else, lying on the floor, caught the light and gleamed golden.

Tully reached down and picked it up and rolled it back and forth on his palm. It was a discharged .44 brass revolver shell.

"Hell's fire!" Rainy blurted. "And everybody knows that carbine of yours is a .44!"

"If they don't know it," Tully said, "I got a good idea who'll tell 'em. And I got a few more ideas, too. If it wasn't Bogan that faked up this deal, there's one other fella—"

A floorboard creaked in the outer room of the station. Tully slapped his hand shut against the flame of the match, snuffing it out. The hammer of Rainy's six-gun made a soft, muffled click. His fingers touched Tully's sleeve and tugged lightly once.

Tully moved beside him toward the door. Rainy tapped his shoulder once and then pushed very gently. Tully hugged the side of the door.

"Now!" said Rainy, suddenly and loudly.

TULLY spun out of the doorway into the main room. He took a long jump to his right, heedless of the noise, and dropped on his knees.

A shot slashed out from across the room, and then another and another in an orange yellow blur. Tully fired back twice, shooting low under the flash, and out of the corner of his eye he saw the blast of Rainy's gun from the other side of the door. The echoes drummed like thunder under the low roof, and the sharp odor of powder burned and tingled in Tully's nostrils.

Something fell with a sprawling thud, and the outer door boomed shut. Rainy fired again from a position further along the wall.

"Dave," he said softly.

"Yeah."

"Man, I didn't jump as fast as you did. He put one right through my hat."