RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

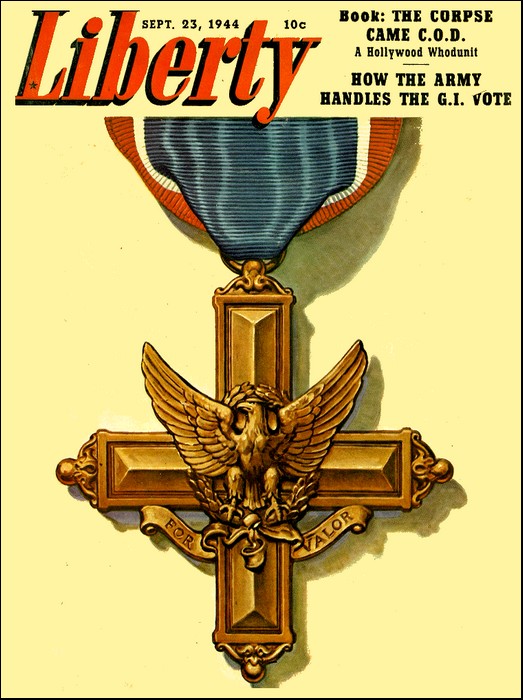

Liberty, 23 September 1944, with "Roll Me Over Easy"

She was just an honest working-girl—even though she did

pick up a man who didn't belong to her. Or was it vice versa?

JUST in case you've never seen it, the Pacific isn't always calm. Sometimes, when the wind is from the nor'-nor'-west, the breakers come in about as high as that lamp-post, with a bump and a ka-whoosh, and if you're not as good as Abe, they put a finger wave in your ears and sand in your good sinus.

Abe coasted right up to where the tourists say "O-o-oh" and stood up and shook herself and tightened the drawstring in the small of her back. She was petite and quite neat and tidy, taken in all. She pulled off her white rubber bathing cap (pre-war) and shook out her hair (blonde, and not dark at the roots, either) and walked up the slope of the beach through the salt froth and goo, leaving nice small high-arched footprints behind her, until she reached the place where she had left her towel and bag.

The bag was red and shiny, decorated with white plastic initials—A for Abiel and B for Burch. The towel was not red nor shiny—nor even there. A character was occupying the space where it had been. The character, definitely masculine, was long and lean and deeply tanned and had close-cropped hair and a concave stomach. It also had its eyes closed and its toes turned up.

"I beg your pardon," said Abe.

The character opened gray-green eyes and regarded her thoughtfully. "That's all right, honey. I'd already guessed the ending of that dream."

"I would like my towel," said Abe.

The character pursed his lips. "As an opening, that's sort of an oldie, but I'll accept it. Sit down. What's your name, and how old are you, and where's your husband?"

Abe said clearly, "My name is Abiel Burch, and I'm twenty-two, and I have no husband. And I want my towel."

"You can drop that gag now, honey. You've succeeded in meeting me. I'm Smith. John Smith. I mean, for a fact. But don't believe all the things you read about me in hotel registers and court records. I'm actually a very upright citizen and an excellent conversationalist. Sit down and we'll beat the gums a bit."

"Give me my towel," said Abe in a remarkably restrained voice.

"Well?" said someone else. "Well?"

This new element was a girl, and she was beautiful. It's a word that is bandied about pretty carelessly these days, but here it was justified. She had black sleek hair and flashing brown eyes and flawless skin tanned to the color of a good brand of malted milk.

She was wearing a red satin bathing suit that would have resulted in her immediate arrest or a first-class riot, had she appeared in it any place where admission was charged. She was carrying two hot dogs in one hand and two bottles of pop in the other.

"Hi, honey," said Smith. "Meet up with a Burch. Her first name is Abiel, but I'll bet she'll let you call her Abe after you've known her for five minutes, like I have. Abe, fill your eyes full of Cass Simmons and compliment me on my good taste."

"It's a fine situation," said Cass. "A girl can't turn her back any more without some sniper moving in." She dug a tinted toenail into Smith's ribs. "Take some of this."

Still reclining, Smith reached up and relieved her of one hot dog and one pop bottle. "Thanks, honey. Abe, sit down and gnaw yourself a chunk."

"I paid for those supplies," Cass stated. "And I'll supervise their distribution. This is all posted property here, Burch. Private and no trespassing. Must you hurry away so soon, I hope?"

"I want my towel," said Abe.

"She goes on like that all the time," Smith explained. "A one-track mind, I think."

Cass snorted. "Towel! Are you very sure you didn't accidentally drop a handkerchief, too?"

Abe was a little white around the lips.

"He—is—lying—on—my—towel."

Cass nudged Smith with her toe again. "Get up."

Smith sat up, balancing the hot dog and the pop. He had been lying on a towel—a blue-and-white towel with the initials C and S scrolled artistically in its center.

"Oh," Abe murmured.

"I was under the impression," said Cass, "that the C stood for Cassandra and the S for Simmons. Have you any other explanation for them?"

Abe swallowed hard. "I left—I left it right here. I did."

"It's very dangerous," Cass told her, "to leave private property lying around on a beach. You can better believe I won't do it again."

"Now, Cass," said Smith, chewing cheerfully on some hot dog. "You wouldn't love me if I wasn't irresistible. And don't you be downhearted, Abe. It was a nice try."

Abe picked up her bag and walked down the beach very rapidly.

THE sun was advertising its last appearance for the day, throwing gaudy red streamers all over the left half of the sky and painting the surface of the ocean a very ghastly hue indeed. Abe was standing on the corner of Colorado, waiting for the bus that went wheezing and sneezing over the steeper parts of the surrounding landscape.

The hood of a custom convertible job that was long and jauntily rakish and a brilliant pale blue slid up even with her.

"Hi, honey," said Smith. "How'd you know I would come by this way? Have you been waiting long?"

Abe stared at him in silence for the count of ten. Smith smiled charmingly. Abe turned around and started to walk up the hill. Smith hooked his thumb over the horn ring on the inlaid steering wheel and held it there. The horn played the first four notes of How Dry I Am—in tune, too, but loud. It was that dry for a total of eight times, and people began to open their windows and look outdoors.

"You stop that!" said Abe, coming back quickly.

Smith did. "Hop in, honey," he invited, opening the door.

"Will you take me straight to my boarding house?" Abe demanded suspiciously.

"I'm sorry, Abe," Smith said, "but I'll have to this time. No use hinting about a longer ride. This candy-wagon isn't mine, and I promised to bring it right back."

Abe stepped back. "Does this belong to—?"

"Yup," said Smith. "Come on. Use up some of her gas coupons. Help wear out her tires."

ABE hesitated and then slid cautiously into the far corner of the wide seat and closed the door. "I live at Sea View Acres. That's up this street ten blocks and then over two."

Smith was still wearing nothing but his trunks. "It's a long walk," he commented. "No wonder you have corns."

"I don't have corns!"

"What's that?" Smith asked, pointing.

"That's a blister! And you mind your own business! And just why aren't you in uniform, may I ask?"

"I'm conservative. I go in for the more conventional types of swimming attire."

"You know very well what I mean. I should think a man of your age would have something better to do than to lie around the beach with—with—"

"Her name is Cass Simmons," Smith said. "And I want to tell you I'm engaged in some pretty important work there."

"What?"

"Providing for my future in this brave new world you read about. Sometime a cute tot with curly hair is going to toddle up to my wheel-chair and ask, 'Grand-pappy, what did you do in the fifth from last Great War?' And I'm going to answer, 'Married a million dollars, you nosy little rat, and if you think it's easy, just run out and try it.

"I think that's utterly loathsome."

"Loathsome?" Smith repeated, surprised. "A million dollars? Oh, no. You've got it mixed up with something else. A million dollars is very wonderful. Do you know how long it would take you, if you started counting now three numbers every second, to get up to a million?"

"I'm not interested. Turn left here."

"A depressing district," said Smith. "Are you one of these socially conscious people who knock around in the slums by preference?"

"I stay here," Abe said clearly and coldly, "because I can't afford any better place. I work for my money."

"How odd," said Smith. "It's a sort of getting there the long way round, isn't it?"

"It's a lot better than being a—a—a gigolo!"

"Oh, no," Smith denied. "We have a very soft time of it. Of course you have to have natural gifts—charm, personality, good looks."

"This is it. Let me out here."

Smith stopped the car. "It's too bad I haven't time to come in so you could display me. Shall I blow the horn so your fellow inmates can come out and gape as I drive off?"

Abe slammed the door. "Just go away—as far as possible!" She opened the gate so violently that it groaned in aged protest.

"Hey, honey," said Smith.

Abe kept right on going up the board walk. Smith touched the horn, but so lightly that it only said "How." Abe stopped and faced around very slowly.

Smith was holding up her shiny red bag, "Look, dear. I know you just wanted to make sure I'd come back, but won't you need this in the meantime?"

Abe returned to the car and snatched the bag from his hand.

"Thanks?" Smith insinuated gently. "I know the lower classes neglect the small courtesies, but you mustn't let your environment influence you too much."

"You get out of here."

"Now you mustn't be piqued because I didn't kiss you good-by. It's hard waiting, but you'll find it all the more thrilling on account of the suspense."

HE drove off with a richly expressive farewell burp from the chrome exhaust pipes. Abe took several deep breaths, clenching her fists, and then went through the gate and up the walk again.

Sea View Acres consisted of an enormous expanse of ground, all of seventy-five feet wide and a hundred and fifty deep, filled up with the sort of structure that would be most likely to be named Sea View Acres. It drooped around the edges and sagged in the middle, and fifty years before, someone had painted it a very natty brand of yellow. Hanging on its porch was a little item constructed of colored glass strips which, when the wind blew, tinkled and clinked in a manner that was maddening to anyone possessed of a sense of rhythm

Abe went under it and into what was nothing less than a parlor, and Mrs. Mulvaney, the proud proprietor of this shambles, stopped rocking and knitting and wheezing long enough to leer in a manner that was not quite obscene.

"My dear!" she said. "And aren't you the clever one to wait until you found something really worth while! Is he a close relative?"

Abe said, "He's a—" She decided not to go any further with that, and asked, "Whose close relative?"

"Now, dearie, don't be so secretive. Of the Simmonses. I recognized the car."

"His name is Smith."

"Smith," said Mrs. Mulvaney, pondering. "I don't recall the name. Perhaps he's a cousin. But don't fret. The Simmonses wouldn't acknowledge any relatives who weren't rich. How did you manage to meet him?"

"I think I'll go take a shower now," said Abe.

"Dearie," said Mrs. Mulvaney, "do you remember the day?"

"What day?" Abe asked.

"This is the day your guest fee is due, my dear."

"I'll bring it right down," Abe assured her.

She went up the stairs and along a hall to her bedroom. There she opened her bag and fumbled around among the débris. There was a small waterproof purse pinned to the bottom. Abe unfastened the pin and took out the purse and opened it. It contained a return bus ticket, a four-bit piece, a dime, two nickels, and a penny. It did not contain a twenty-dollar bill.

Abe began to feel a bit cold and queasy at a point just two inches below her ribs. She dumped the contents of the bag out on the bed and pawed them over. There was nothing present that even faintly resembled coin of the realm.

Abe stood up straight and began to breathe loudly through her nose. It took her all of a second and a half to figure out where the twenty-dollar bill had gone and who had taken it there. She paused long enough to peel her bathing suit off and replace it with a pair of slacks, a blouse, and some huarachos. Then she marched downstairs.

"Do you know where the Simmonses live?" she asked.

"Of course, dear," said Mrs. Mulvaney. "Up on the Rim with the rest of the swells. 340 Harkness Road. But before you go, hadn't you better fix up your face just a little and select a costume that isn't quite so wrinkled? And remember, rich young men are very easily frightened off. Don't press him too hard, dearie."

"I'll press him one right in the teeth," said Abe.

THE Rim lived up to its advance billing. It was littered with estates of one kind and another—all with a certified view of the ocean, and all surrounded by walls high enough to relieve the occupants of the necessity of looking at it. At 340 Harkness, Abe found a large gate that was shut and a little gate that was open. She selected the latter and went through it and up a quaintly crooked path paved with red sandstone, which ended in front of a long sun terrace. Smith was on the terrace, wrapped in a striped bathrobe now, reclining in a chair constructed exclusively of chrome and red leather and contemplating the mysteries of the twilight while chewing meditatively on a wad of gum.

"Hi, honey," he said without any noticeable signs of either enthusiasm or consternation.

Abe walked right up to him and pointed her finger. "You stole twenty dollars from me!"

"Now that's more like it," said Smith. "As an opening it catches the attention and gives you a chance for a fast follow-up. You should have used it in the first place instead of clowning around with that corny lost-towel gag."

"I'm serious about this," Abe warned.

"Naturally," said Smith. "You don't run across an opportunity like I am every day. But relax. You're doing all right. I'll speak to you the next time I see you on the street. I'll even remember your name, I bet."

"You give me my money!"

CASS appeared in the French doors at the rear of the terrace. She wore a white quilted robe that positively hadn't been picked off a bargain counter, and she was carrying a tray with two tall frosted glesses on it. She hesitated for a moment, then came forward and put the tray on the glass-topped table that stood beside Smith's chair.

"Look here," she said. "Can't a girl leave her man in her own back yard without having competition barge in on her?"

"I'm not competition!" Abe cried.

"I know it, Burch," said Cass. "But how am I going to persuade you of that?"

"All I want," said Abe shakily—"all I want is the twenty dollars that he stole from me."

"I suppose a girl with a face like yours gets a little desperate at times," Cass said, "but you're going pretty far now, aren't you?"

"He took twenty dollars from my purse! He did!"

"I suppose," said Cass, "that twenty dollars is about the largest amount you can think of without gasping, but what would he want it for?"

"Now you just listen here," said Abe, swallowing. "You can laugh and—and sneer about twenty dollars, but it's the last of the money I saved for my vacation, and it was going to last me for another whole week! And if he doesn't give it back to me I'll have to go h-h-home!"

"That's an idea," said Cass. "Why don't you?"

"I won't! I'll have him arrested! That's what I'll do! You'll see!"

"I suppose you would," said Cass. "You're just the type. Wait a minute."

She disappeared through the French doors.

"Nice work," said Smith admiringly. "You might as well have upped the ante a bit, though. Never sell an act like that short."

"What do you mean?" Abe demanded.

Smith leaned forward to peer interestedly. "Can you break out with tears like that any time you want?"

"Wh-what tears?"

"These."

Abe slapped at him. "You keep your hands to yourself! And they're not tears!"

"They're certainly convincing imitations," Smith said. "What formula do you use?"

Cass came out on the terrace. She was carrying two crisp new ten-dollar bills folded lengthwise. She handed them to Abe.

"Here you are, and let's see a lot less of you from now on."

Abe accepted the bills numbly. "But this isn't my—these aren't—" And then she began to have palpitations and black spots before her eyes and a horrid iciness back of her knees. "Oh! O-o-oh!"

She tried dramatically to tear the bills in two. They wouldn't tear. She crumpled them up, one in each hand, and threw them down on the terrace and stamped on them. She turned around and marched down the path, shoulders back, heels clicking.

Cass said, "The service entrance—and exit—is in the rear."

TO save bus fare, Abe walked all the way back, and as she approached it in the gloom, Sea View Acres looked just about as cheery as the mad monster's castle in that last B picture you saw.

"Now," said Mrs. Mulvaney, still holding down the parlor, "you see? And you can't say I didn't warn you. You should listen to the advice of people who have had experiences in this line, dearie. I could tell you things about rich men—"

A very nicely fitted naval uniform walked in.

"Oh," said Mrs. Mulvaney. "Oh! How do you do?"

"O.K.," said Smith. "And remind me to tell you how gorgeous you're looking sometime. But right now run out in the kitchen and reel in a roast. I want to have a conference with the babe here."

"Oh, you," Mrs. Mulvaney simpered. "You sailors." She hesitated coyly in the doorway, then pointedly disappeared.

"Where .did you get that uniform?" Abe demanded.

"This?" Smith asked. "Oh, I borrowed it from my cousin Slevak. You wouldn't care for him. He's a dull fellow."

"That's an ensign's uniform," said Abe. "And that's a South Pacific campaign ribbon—with two stars on it."

Smith looked down and counted. "One, two. You're right, at that. Here's something old and something new just for you."

He handed her a towel that Abe had seen somewhere before. Pinned to it was a twenty-dollar bill that also had its familiar aspects.

"You took—" said Abe. "All the time you had—and you let me—"

"Yup," said Smith.

"You—you—you—you—you—'*

"Mustn't say the naughty word," Smith warned. "Look. It's your own fault. For a week I've been trying to call me to your attention. I smiled and I smirked and I winked. I think I even leered a time or two. No soap. So I had to resort to what are commonly called drastic measures. Hello, Abe."

"If you have the nerve to think that after this I would—would—would—"

"Would what?" Smith inquired, interested.

Abe opened and closed her mouth three times and then said suspiciously, "What about Cass?"

"I will tell all," Smith said. "There shall be no secrets between us. When we came in, Cass was waiting at the dock to pick herself a sailor for a souvenir. Since I was by far the most handsome and most personable one there, she picked me, and since my resistance was low, what with malaria and termites of one kind and another, I didn't resist hardly any—at least, not until I got a good look at you."

"I don't believe one word of that," said Abe flatly.

CASS came into the parlor. She was carrying a battered valise, and she held it up waist high and dropped it with a thud.

"You dog," she said. "You filthy, ungrateful, two-timing rat."

"Don't tell me now," said Smith. "Let me guess. I've got it. You're referring to one J. Smith."

"Yes," said Cass. "And if I never refer to him again, it'll be a lot too soon. And as for you, Burch—you're welcome!"

She went out and slammed the door so hard the echoes played touch-tag all over the, building.

"Maybe I should have tipped her a dime," said Smith.

"How did she know you were here?" Abe asked.

"Probably because I told the butler to pack my bag and send it over."

"And what did she mean by that 'welcome'?"

Smith smiled photogenically. "You pulled down the jack pot, honey. You've won first prize. Namely, me."

"I—wouldn't—have—you—for—a—gift!"

"Aw, now," said Smith. "Not even if I said please nicely? Like this, 'Please nicely'?"

"Well," said Abe. "We-ell..."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.