RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

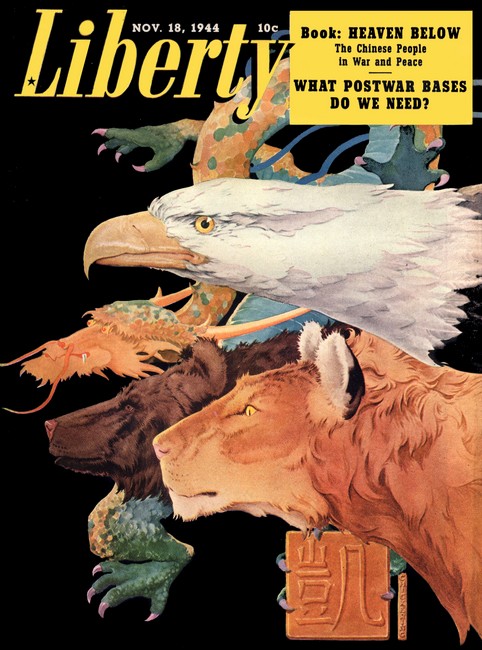

Liberty, 18 November 1944, with "Blow the Man Down"

Quentin always forgot to show up for a date with his girl, but he had an awfully good memory for ships—which turned out to be pretty useful in a romantic way after all.

THE rain intruded itself with all the boisterous and unappreciated enthusiasm of a drunk barging in uninvited on a formal dinner party.

Porky was driving the big dingy sedan, and he said, "You want some advice, Dutch?"

"How much will it cost?" Dutch asked.

"Nothin'," said Porky, surprised.

"No," said Dutch. "It's overpriced."

Dutch, more formally but much less frequently known as Bettina DeVries, was sitting in the far corner of the front seat. She was tall and she was thin and she had black hair and smoky gray eyes with a determined gleam in them.

"All right," said Porky. "But, anyway, you should give this Clinton Quentin party the brush-off, because he is nothing but a dope."

"He is not," Dutch denied. "He's a very smart lad. He knows more about ships than anybody alive. He can tell you the name, number, and capacity of any ship built in the last forty years, and even, if you insist, the color the smokestacks are painted."

"So he's a dope," said Porky. "You know what ships are? They're obsolete. Pretty soon now some kid is gonna ask, 'What is a ship, pappy?' and pappy won't even know, unless he took a gander in a museum on his off day. You work in a plane factory. You should know that. You take tonight, Dutch. Now, you know it wasn't right for Quentin, that dope, to stand you up when you went to all the trouble of gettin' dressed all pretty for him at the plant, with all them dim-witted dames pokin' you in the eye and steppin' on your toes while you was doin' it. I wouldn't commit marriage with that Quentin dope, Dutch."

"He didn't ask you to marry him."

Porky looked at her. "Did he ask you?"

"No. This is leap year. But he said yes."

"Then you're stuck," Porky stated. "He's got you. He's like to sue if you don't go through with it. But you better think twice."

"You think about stopping," Dutch ordered. "I don't care to walk six blocks in this rain."

THE sedan swished through water gurgling in the gutter and paused. "See you, Dutch," said Porky. "Don't forget to lower your landing gear."

Dutch nodded glumly, trying to crawl inside the collar of her coat. She ran pigeon-toed and squishing across the neat plot of grass and up the apartment-house walk. The door mumbled and hissed and let her reluctantly into a lobby that was neat and new and had powder-pink walls. Dutch scowled at her image in the jag-edged mirror and then went up six steps and along a hall lined with shiny blue doors.

One of the doors was ajar, and Dutch pushed it wider and went into the living room of an apartment surrounded by the same powder-pink walls and decorated with off-blue furniture.

There was a man lying on his stomach in the middle of the rug. He was a tall and bony man with corn-colored hair that dribbled down over his forehead, and blue eyes effectively distorted by a thick pair of rimless spectacles. He had a blueprint spread out in front of him, and he was studying it with soulful absorption.

"Hello, Dutch dear," he said absently, looking up and then down again at the blueprint.

Dutch didn't answer. She shut the door carefully. She sat down in a chair quietly. She watched him, but eloquently.

It took about ten seconds, and then Clinton Quentin looked up again and smiled at her in his bashfully endearing way. "Gee, you look pretty, Dutch."

"Why?" said Dutch.

"Uh? Oh. Well, that's a new dress you're wearing, isn't it?"

"Why?" said Dutch.

"What? Oh, you mean our date tonight."

"Yes," said Dutch. "I can recall that faintly if I put my mind to it."

"Gee," said Quentin. "You're not mad, are you, Dutch?"

"Not any madder than you'll be dead in about a minute."

"Aw, Dutch," said Quentin. "Take it easy. Now I want to explain to you just how—"

WATER burbled plaintively in a pipe behind the wall. Dutch came out of her chair in one catlike leap and landed, facing north.

"Who's that in the bathroom?" she said through her teeth.

"Relax, Dutch. I was just going to—"

"Who—is—in—the—bathroom? "

"A hero," Quentin said quickly.

Dutch looked at him. "A what?"

"Well, he is," said Quentin.

"Ten times."

"Ten times what?"

"Torpedoed," said Quentin.

Dutch sat down again reluctantly. "I don't make much sense out of this, but you'd better—right now."

"He's a mate in the merchant marine, like I'm trying to tell you," said Quentin. "And he's a hero because he's been torpedoed ten different times. And his name is Smaltz."

"Smaltz?" Dutch repeated thoughtfully.

"Yes, but he doesn't like to be called that. He says it was a slight error on his mother's part. His full name is Terence O'Shea Smaltz. He's been thwarted."

"What was that again?"

"Thwarted—in love. This girl he goes with won't say she'll marry him right away, like she should. He feels terrible about it."

"Does he have to do it here?"

"Sometimes you're awfully hard, Dutch," Quentin said. "I felt sorry for him. He came down to the yard today to bust a jug of fizz on the Johnson A. Bestwyck when it was launched, and then when it was over he didn't have any place to go."

"I can give him a destination."

"Now, Dutch. He's a hero! How would you like to be torpedoed ten times?"

"How would he like to massage wing flaps all day?"

"Oh, that's different," Quentin said. "He really feels bad, Dutch, and I told him you'd help him."

"Help him feel bad? I'll be glad to."

"Now, Dutch," Quentin warned. "I'm going to be disappointed in you if you act like this."

Dutch rested her elbows on her knees and her chin in her hands and stared at him in a thoughtful, calculating manner.

"I am," said Quentin.

Dutch sighed. "What's your idea of how I should act?"

Quentin cheered up instantly. "Well, all you have to do is to see Clarabelle and tell her what her duty is."

"What is it?"

"Why, she should marry him, of course, and right away, too, so he won't be worried all the time."

"Just supposing I told her that," Dutch said, "why should she believe me?"

Quentin looked wildly amazed. "Well, you're smart, Dutch."

"I doubt that at times," Dutch told him, "and this is one of them."

"Oh, you can persuade her," Quentin said confidently. "You won't have any trouble. I told Mr. Smaltz we'd go with him to the Borodino—it's that fancy new cocktail bar on Fourth. Clarabelle goes there sometimes because it's so refined. She told Mr. Smaltz she might maybe be there tonight if she didn't have anything important to do. Of course, we're taking a chance on finding her. She's very popular."

"Something tells me," said Dutch, "that Clarabelle and I are going to remain the merest chance acquaintances."

"You'll like her. She's very beautiful, Mr. Smaltz says, and has a wonderful personality. It won't take us long, Dutch. You just persuade her to marry Mr. Smaltz, and then you and I will go to the picture show."

"Why?" Dutch asked.

"We always go to the picture show on Wednesday."

"This—isn't—Wednesday."

"Then that's why I forgot our date!" Quentin said triumphantly.

"It always makes me a little ill to have logic like that explained to me," Dutch stated, "so let's drop it. Let's run a test on this Smaltz specimen. Or has he taken a lease on the bathroom?"

"He has to clean up and shave and everything awfully carefully," Quentin said. "Clarabelle is very particular about that. She says if a man dresses sloppily on a date, it doesn't show proper respect for the girl. She says when a girl gives a man a date, it's an honor, and he should act like he appreciates it."

"That's a very interesting point of view," said Dutch. "Don't you think so?"

"Yes," said Quentin seriously.

Dutch drew a deep breath and let it go again. "All right. Knock on the door and leave an early call for Mr. Smaltz."

Smaltz saved him the trouble by appearing under his own power. He was so neatly creased and painfully scrubbed he looked like a self-illuminated window display of a dress designer's conception of a mate in the merchant marine. He had a one-story forehead, and he was a little wide between the eyes, but he looked like he could read.

"This tie," he said anxiously. "There's a crease that doesn't quite center below the knot. Can you notice it?"

"No," Quentin assured him. "You look just dandy. This is Dutch."

"Is it?" said Smaltz.

"Probably," said Dutch. "What's the beef with your bag, Smaltz?"

"Dutch!" Quentin protested. "Don't mind her, Terry. She's just joking. She's very interested in your difficulty with Clarabelle. She wants you to explain it to her."

Smaltz thrust out his lower lip sullenly. "It's her old man. He put ideas in her head."

"From what I hear, he must have been a fancy operator," Dutch observed. "I did detect the use of the past tense there, didn't I?"

Smaltz nodded. "Yeah. He's dead. How can you argue with a guy that's dead?"

"It's hard," Dutch agreed. "What are you interested in selling him?"

"Well, he was a captain, see? For twenty years on the same ship. All through the last war, too. And he never got torpedoed. He said there was no sense in getting torpedoed."

"No sense?" Dutch repeated.

"Yup. He said if a ship gets torpedoed, that's on account the officers are dopes and don't know their business. He said if the officers were competent it wouldn't happen. The trouble is, he proved it. He never lost an inch of paint or even a passenger all the twenty years he was operating. He never got sunk or went aground or even had to put out a distress signal. He must have been really a lulu."

"How does this fit in between Clarabelle and you?"

"She compares," Smaltz said glumly. "Me and him, I mean. Ten ships I lost already. Clarabelle thinks that's too many. It shows I've got a flighty character or else I got flustered in a pinch, or else I haven't had the right training. I can't persuade her different."

"Dutch can," Quentin said. "You'll see. Dutch is very clever."

THE Borodino had been conceived by a man who was a movie fan and dedicated to the relaxation of people with the same or similar tastes.

"There's Clarabelle now!" Smaltz announced. "See?"

Clarabelle was down at the end of the bar talking animatedly to two characters.

"Gee," said Smaltz, "how do you suppose I can persuade her to join us?"

"Just ask her," Dutch said. She pointed to a swirl in the smoke. "We'll be in that booth."

"This is a swell place," Quentin said.

"There's nothing wrong with it," Dutch agreed, "that couldn't be cured by a slight touch of arson."

"Folks," said Smaltz proudly, "this is Clarabelle. This is Dutch, and that's Quentin."

"Dutch," said Clarabelle with a gay tinkle of laughter. "That's a funny name, but it fits you."

"Thanks," said Dutch, after a suitable pause. "Won't you join us?"

Clarabelle hesitated prettily. "I shouldn't really—I have a very important engagement. But just for a few moments. And oh, here's the waiter! Pierre, I'd like un Borodino Boolevard Speciale.... They are a little expensive, of course, but I find them so refreshing."

"I'll try one," said Smaltz. "I'll bet they're wonderful. Just like you."

"Silly," said Clarabelle with a roguish tilt of her head.

"Beer for the proletariat," said Dutch.

"Say," said Quentin, "I think I'd like to try—"

"A beer," said Dutch.

"Yes," said Quentin doubtfully.

"Oh, are you two married?" Clarabelle asked.

"No," Quentin answered, "but we're engaged. With a ring."

"How nice!" Clarabelle exclaimed. "And I think those small diamonds are awfully cute, too."

The waiter came back, and Dutch drank a lot of beer very quickly. She put the glass down reluctantly and said in a fairly polite voice:

"I understand you and the Smaltz have ideas along the same line."

"Oh, that Terence," said Clarabelle, "he's so—so persistent."

"There are worse faults," Dutch remarked.

"You bet," Quentin said solemnly. "Terence is a swell fellow."

"Aw," said Smaltz-.

"Oh, I think he's awfully cute, too," Clarabelle said. "I do, too, Terence! Really! But do you know what he does, Dutch?"

"What?" Dutch asked.

"He gets torpedoed. Just one time right after the other. He's always getting torpedoed. I think there's something funny about that, don't you?"

"It's just killing," Dutch agreed.

"I mean funny peculiar. My father never got torpedoed, and he took lots and lots of trips right through the whole other war. He said there was no point in getting torpedoed. I think there must be something wrong about a person who does it all the time."

"Aw," said Smaltz.

"I do, Terence. Truly. I'm sorry, but when one is a girl like I am and is constantly receiving offers of marriage, then one must be very careful about making a choice that might lead to the ruin of her whole life. One must be absolutely sure, Terence."

"I'm sure," said Smaltz.

"But, you see, that's not the important thing. Oh, I only wish my father, the captain, were here. He was such a strong and successful man. Everyone trusted him so. When he retired and left the Barton Bellflower, the crew lined up and cried. Actually. He was so dependable; they felt lost without his hand at the helm."

"Barton," said Quentin. "Bellflower. Oh, yes. She was built in 1911 by Banner Brothers for the Rockaway Bay Refuse Disposal Company."

THERE was a quite dreadful silence. "A garbage scow," said Smaltz slowly, at last.

"No," said Quentin, surprised. "Not a scow. A tug. It was one of the—"

Smaltz put his hands flat on the table and leaned on them. "Garbage!"

"It isn't true," said Clarabelle faintly.

Smaltz let out his voice a couple of stops. "Look at him! He hasn't got sense enough to lie! And even if he had, why should he?"

"Ah-hu-hu!" said Clarabelle brokenly.

"Go ahead," Smaltz snarled. "Go ahead and blubber. See what good it does you. And he never got torpedoed! Why should he? You think the Germans got nothing better to do than to fertilize the bottom of Rockaway Bay?"

"T-Terence," said Clarabelle—"ah-hu-hu!"

"And he never lost a passenger," said Smaltz, shifting into high. "What kind of passengers? Pigs? And he was a strong man, was he? I bet he anyway smelled that way!"

"Ooooooh!" Clarabelle wailed. "Ah-hu. ah-hu!"

"You got the brassbound nerve," said Smaltz, rattling the glasses on the back bar, "to compare a deep-water mate with a garbage-scow skipper? You know what I say to your old man, and especially to you? Blah! Did you get that? Blah!"

He made for the front door, leaving dents in the floors

"Ooooooh!" said Clarabelle. "Ah-hu! He's going to leave me!"

"Gee!" said Quentin, awed.

"What'll I do-o-o?" Clarabelle sobbed.

"You're a little dated, dearie," Dutch told her with the merest trace of sympathy. "The rest of us dropped that hard-to-get act long before Pearl Harbor. If you don't want to lose what looks like it might be a fair-to-middling husband, you'd better run awfully fast and cry awfully loud and sing awfully small. And you'd better hurry. There's a taxi stand two blocks down the street."

CLARABELLE scrambled. But she had time enough, when she got halfway to the door, to turn around and come right back again and slap Quentin neatly on the mouth.

"Hey!" said Quentin, flabbergasted.

Dutch sputtered a little in her beer, watching Clarabelle's exit.

"Hey," said Quentin in an injured tone, "what did she go and do that for?"

"Dear," said Dutch in a kindly voice, "if you were running around on a catwalk carrying a bag of cement and decided to light a cigarette, wouldn't you sort of look below before you dropped the sack?"

"I wouldn't be carrying cement on a catwalk," Quentin told her. "And if I was, I wouldn't drop it. Cement is expensive. Sometimes you say the silliest things, Dutch."

"Yes, dear," said Dutch. "Drink the beer now."

"Well, she shouldn't have hit me like that," said Quentin. "After we helped her, too."

"Come, come," said Dutch. "Time presses."

Quentin followed her out.

"I'll drive," Dutch said, opening the door of Quentin's neat convertible and sliding under the steering wheel.

They drove several blocks north of there, and then Dutch stopped the car at the curb in front of a house that had a light on the porch.

"Here we are."

Quentin felt for the door handle. "O.K. I'll just—This isn't where you live, is it?"

"No," Dutch answered. "It's the residence of a party named Throckley. The Reverend Throckley."

"Oh," said Quentin. "Friend of yours?"

"Not a friend. A business acquaintance. Now try hard, dear. This is Friday the eighteenth. Does that date mean anything in particular to you?"

"Friday," Quentin repeated thoughtfully, "the eighteenth. Say! That's the day we were going to be married!"

"Not were," Dutch corrected. "Are."

Quentin started to count on his fingers. "Monday was the thirteenth—"

Dutch slapped his hands. "Stop that! Are you going to marry me or not?"

"Well, certainly I am," said Quentin. "I just didn't think—"

"Don't bother to start at this late date," Dutch ordered. "I'll handle that end of it. You just concentrate on answering the man's questions—correctly."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.