RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

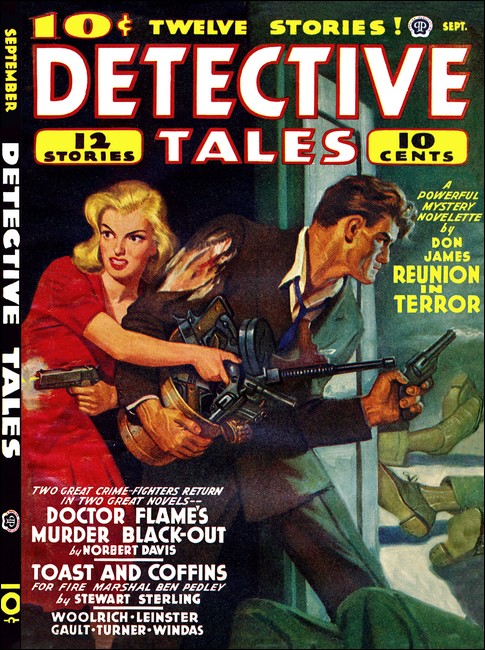

Detective Tales, September 1942, with "Doctor Flame's Murder Black-Out"

Doctor Flame, who spent his life serving the destitute, expected hardship. But he had never followed a corpse-strewn trail, in the midst of a city-wide black-out, to a young girl patient clutching a crimson razor!

THE truck thundered through the narrow streets with the horn blatting raucously and the head-lights cutting a swath in the swimming darkness that night always brought to the slum district. It was cold, and the air was acrid with coal-smoke even inside the closed cab.

O'Phelan was driving, and he coughed thirstily now, shivering. He was a little man, fox-faced, with a long nose that wiggled inquisitively. He was bundled up in a sheep-skin jacket, and he wore a red stocking cap and a red muffler.

"Klogatz, my friend," he said. "It's a night to chill the bones of a baboon, and I'm thinking it's a beer we need before we start out rattling people's garbage cans. Now if we'd just pause for a second or two at the Green Clover over on Decker Street—"

"No beer," said Klogatz. He sat solid and squat, thick arms folded across the barrel of his chest.

O'Phelan struck the steering wheel with his mittened fist. "Ah, the pity of it! The sin of it, that a scholar like me must ride through the night with nothing for company but a Polish lump of lead with mud for a brain!"

"Look out!" Klogatz shouted.

O'Phelan grabbed the steering wheel with both hands again and twisted it frantically. Klogatz reached down and seized the emergency brake.

One of the front wheels bucked against the low curb and up over it, and the dual rear tires locked and screamed as they slid over the rough paving. The truck rocked to a stop.

O'Phelan knocked up the door catch with his elbow and was out on the sidewalk like a flash. He darted ahead and caught the arm of the dark figure that stood frozen three steps out from the curb.

"So!" he snarled. "You'd run out in the middle of the street in the dark, would you? And with no warning at all. You'd be looking to get a damage suit against the city, eh?"

The head-lights were twisted sideways now, and the woman was out of their direct beams. She was short and thick-set, middle-aged, shabby in a long black coat that had seen better days. Her hat was shapeless, and it looked as though it had been hastily slapped on her head. She was breathing in sobbing broken gasps that shook her whole body.

"Let me go! Let me go!"

"I saved your life." said O'Phelan crossly. "If you know or if you care. What ails you that you should go jumping at trucks in the dark?"

The woman's face was a stiff white mask. She twisted against O'Phelan's grip.

"She is scared," said Klogatz. "Let her go."

O'Phelan turned on him. "Who asked you—"

The woman jerked frantically and got away from O'Phelan. She whirled and half-fell, and her voice made a whimpering wordless sound in the darkness. Then she caught herself and ran desperately up the street. The hurried, irregular tap of her foot-steps echoed and then was gone.

"Drunk," said O'Phelan. "Or maybe crazy."

"She is scared," said Klogatz.

"Have it your own way, then, lump-skull!" O'Phelan snarled. "And what do you think I am? Me, with my heart in my throat and my stomach tied in a bow-knot?"

"No beer," said Klogatz.

"Oh, so you think I'd stoop to play on your sympathy, do you?" O'Phelan raged. "You think I'd beg you for a small glass to soothe my nerves when they're ready to hop out of my head and—"

A MAN loomed up suddenly in the flare of the head-lights. He was tall and thin, with a sharply white face. The frozen moisture of his breath plumed out raggedly in front of him.

"See a woman run past here?" he asked shortly.

"Did I?" O'Phelan said. "I did. And if I hadn't she'd be spattered on the pavement like a broken egg."

"Which way'd she go?"

"Wait," said Klogatz. "Who is it that asks?"

"Yeah," said O'Phelan. "Who are you to be chasing her through the streets?"

The tall man dropped his hand into his overcoat pocket. "Mind your business. Which way'd she go?"

"As to that," O'Phelan answered blandly, "I disremember."

The tall man's hand came far enough out of his pocket to reveal the gleam of metal. "You'd better remember again, or you'll wish—"

"Troop," said a voice. "Stop that."

The newcomer was back in the shadows, bulking fat and enormous, his face a pale shapeless circle. He moved away as they turned to look, and the light reflected slickly from his patent leather shoes.

The tall man said: "These guys saw—"

"I said stop it. Come along."

"Yes, sir," said the tall man.

He threw a dark look at O'Phelan and Klogatz and walked quickly after the fat man. O'Phelan and Klogatz stood watching them. Just before they reached the intersection, a long shiny sedan slid into sight and paused. The fat man and the tall man got in, and a door closed with a solidly luxurious thump. The sedan disappeared.

"That fat one," said Klogatz. "That is a bad one."

"The tall one is bad enough for me," O'Phelan answered. "That was a gun he had in his pocket. I wonder why they're chasing that poor woman."

"It is not our business," said Klogatz. "We work."

"You mean—-right now?" O'Phelan asked weakly. "After I almost ran over a woman and got my life threatened all in the whisk of a minute? Oh, I ought to sit down somewhere and compose myself—"

"No beer," said Klogatz.

"Did I ask for a beer?" O'Phelan shouted.

"Be quiet," Klogatz ordered. "Someone else comes."

O'Phelan looked around. "Eh? Ah, it's Doctor Flame! Doctor! Ho, Doctor!"

Doctor Flame stopped short, peering with one hand raised to shield his eyes from the head-lights. "Who is it?" He was a slight and shabby figure, long overcoat dragging carelessly to his heels, battered old hat pulled low over his forehead. He carried his bulging medical satchel in his right hand.

"O'Phelan and Klogatz, Doctor. And it's a mean, cold night to be out, eh?"

Flame came closer. "I heard some shouting. Was there any trouble?"

"Just a bit of an argument," O'Phelan said.

"He does not pay attention when he drives," Klogatz added in his stolid, measured tone.

"That's a filthy lie!" O'Phelan yelled. "I'd smash you flat, you Polish ape, if the good doctor wouldn't have to waste his time patching up your good-for-nothing hide again!"

Flame said: "Speaking of patching, I have been meaning to have a look at your arm, Klogatz. But it's too dark here in the street...."

"Sh!" O'Phelan exclaimed triumphantly. "I know the very place, Doctor! Just step right in the truck, and we'll be there in the wink of an eye!"

THE truck shuddered as O'Phelan threw it into reverse and backed off the curb. O'Phelan straightened it around, and it rumbled on up the street.

Klogatz, standing on the running board, hammered on the window and shouted, "Where are we going?"

"Right here," O'Phelan answered, and swung in against the curb in front of a bleary green neon sign that spelled the words Green Clover Café. He got out of the truck and batted through the doors of the place like a bandmaster leading a parade. "One side, please! Make room for Doctor Flame!"

Flame and Klogatz followed him, and Flame nodded to the man behind the bar.

"Good evening, Rogan. May I use your place for an examining room for a moment?"

Rogan was a sawed-off little man with a cheerfully battered grin. "To be sure, Doctor!"

"Take off your coat and shirt, Klogatz," Flame said.

The cafe was small and square, unadorned with any furniture except the bar and a line of battered chairs against the wall. Smoke billowed in blue shifting layers against the low ceiling. Men were crowded thick in front of the bar—mill workers with tired faces.

They shoved back now, making room, mumbling quick greetings to Doctor Flame, some of them in foreign tongues. They all knew him. He might ride on a garbage truck and examine his patients in a slum saloon, but his wishes were obeyed instantly because these men knew him.

This shabby little man with the ugly, tense face and the fiercely burning eyes was Doctor Edward Carl Flame, who could string a half-dozen degrees in advanced medical theory after his name. He practiced in the slums not because he had to, but because he wanted to. Because he hated suffering and sickness.

He lived on fees that would have been scorned by the elegant specialists up-town. He didn't mind. He had found people here who needed him and trusted him.

The slum people never understood him—never tried. They only knew that Flame helped them as no other man ever had. In return they gave him a savage, clannish loyalty that went far beyond words.

O'PHELAN helped Klogatz out of his fleece-lined jacket and his pullover sweater and heavy flannel shirt and peeled the top of his woolen underwear off his thick shoulders. Klogatz's torso was an enormous, muscled wedge. A jagged red scar ran from the top of one shoulder, down in a semi-circle following the line of his shoulder blade, and ended on his right side under his arm. Flame began to probe gently on either side of the scar.

O'Phelan looked around confidentially at the tensely interested faces of the onlookers. "Ah, you should have seen Klogatz the day that happened! We were picking up cans over on Delancy Street when some drunken skalpeen drove his car into the side of the truck and tipped it over on Klogatz before he could jump clear. Smashed him like a bug! And that little tit-mouse of a doctor on the ambulance took one look at him and says his arm will have to come off!"

"Raise your arm," Flame said to Klogatz.

"But it didn't come off!" said O'Phelan. "There you see it, stickin' up like a red-wood log! And why? Because I ran yelling through the streets and found Doctor Flame! I brought him to that bloody receiving hospital. And there I sat, sick as a dog, while Doctor Flame carved Klogatz up like a side of beef and put him back together again! I swear it's true!"

Flame straightened up. "It's coming fine, Klogatz. If it bothers any, come and see me."

"I thank you, Doctor," said Klogatz. "I do not forget this—never."

"Can we give you a lift to where you're goin'?" O'Phelan asked.

"No, it's just a block. I'm going over to Rizzio's to take the cast off his boy's arm. Thanks, Rogan."

"'Tis nothing," said Rogan. "Will you have a short drink to keep out the cold, Doctor?"

"Not now, thanks." Flame went out into the night.

"But I will," said O'Phelan, "since you're so kind as to mention it, Rogan."

Klogatz was putting on his coat. He reached out one thick arm, caught the tail of O'Phelan's sheep-skin jacket and jerked him away from the bar.

"No drinks."

"What!" O'Phelan squalled furiously. "You dirty Polish lump of lead! You'd dare refuse me after I helped Doctor Flame examine you, and me with the worry for your health dinging in my brain like a fire gong?"

"No beer," said Klogatz, heading for the door and dragging O'Phelan behind him.

IT was almost two hours later that Flame came around the corner and walked down the block toward the dingy building where he lived and had his office. Removing the cast from the Rizzio boy's arm had been a simple enough task but Papa Rizzio had complicated it.

The fracture had been a bad one, compound, acquired when the Rizzio boy had tried to hop a truck and missed, and all the time it had been in a cast Papa Rizzio had been terrified with fear lest the arm never be right again. When Flame had demonstrated tonight that it was just as good as ever, Papa Rizzio had forced Flame to sit and drink tall glasses of red wine while twelve Rizzios expressed worshipful gratitude.

The street on which Flame lived was never well lighted, but a black-out warning had come while he was still at Rizzio's and now it was pitch-dark. A siren made a thin eery keen in the distance.

Flame's hurried foot-steps echoed emptily until he stopped at the bottom of his front stairs, wondering if there were any calls he had forgotten.

Standing there, he had the uneasy sensation that there was someone close to him. He turned his head quickly each way. Nothing moved in the darkness, and there was no sound except the faint stir of paper rubbish in the gutter. He shrugged and started up the steps.

A voice whispered hoarsely: "Wait. Please—"

Flame turned around. "What?"

"Wait, please. Are you—Doctor Flame?"

Flame stared into the darkness under the steps. "Yes. Who are you?"

The shadows moved a little. "Can I see you—for a minute, please?"

"Certainly," Flame answered. "But not here. Come on inside."

"I don't want—nobody to see...."

"Nobody will see you," Flame said. "Come along."

He opened the wide front door and went into the warm antiseptic-smelling waiting room. The steps creaked outside, and then a woman slipped through the door and shut it quickly.

Flame ran his fingers lightly around the window to make sure the black-out curtains were tight and then snapped on the drop-light over the big center table.

His woman visitor was middle-aged and stocky, and she wore a long black coat that fitted her badly. It looked like a hand-me-down and her hat did, too. Her heavy-jawed face was blue with cold, and she was shivering.

Flame opened the medicine cabinet and poured a jigger of brandy.

"Drink this," he ordered. "Why did you wait out in the cold, especially when there's an air raid warning on? This office is never locked."

The woman's teeth chattered on the rim of the glass. "I didn't want nobody to see...." She drank the brandy and coughed.

Flame pointed to a chair. "Sit down."

"I don't care what your name is," said Flame. "Why did you want to see me?"

"It ain't for me. It—it's a friend."

"Well, where is the friend?"

The woman's throat muscles moved as she swallowed. "Do you know anything about people's brains? About people that are—crazy?"

"A little," said Flame.

"Do you know what it is when a person thinks other people are after her, trying to hurt her all the time?"

"It might be several things," Flame said, watching her narrowly. "It could be paranoia."

"Yes!" said the woman, nodding in relief. "That's it. That's what they say. Could you tell if a person had that?"

"Probably," said Flame. "But not without seeing the person."

The woman leaned forward tensely. "Would you go with me—not knowin' me or anything—and see a person like that?"

"Can't you bring the person here?" Flame asked.

She shook her head quickly and desperately. "No! They're tryin' to find her and take her back, and her so young and pretty and scared. They nearly caught me—"

"They?" Flame repeated. "Who are they?"

She shook her head mutely. "I can't tell you. People—ones that live around here—told me you was a smart doctor and a kind one and that you wasn't afraid of nobody. Will you go with me?"

"Surely," said Flame.

"Even if—if someone was to try to stop you?"

Flame picked up his coat. "We'll worry about that when it happens," he answered.

"Wait," said the woman. "Just one thing I want to ask first. If people were really tryin' to persecute this person, then she wouldn't be crazy because she thought that, would she?"

Flame said: "Certainly not."

"I knew," the woman whispered. "I knew it. She's not crazy at all. They're makin' it up!"

"Better wait until I see her," Flame advised. "Shall we go?"

"If we could go out the back way.... They was watchin' for me a while ago...."

"Let them watch," said Flame. "If they try to stop me when I'm on my way to a patient, they'll wish they hadn't, whoever they are."

"No!" the woman begged breathlessly. "You don't know what.... Please! The back way!"

Flame shrugged. "All right. Follow me."

THERE are degrees of degradation even in the slums, and the blocks back of Trailer Street touched the bottom. The buildings were age-warped monstrosities and the streets were always slick from water that crept up like a sluggish animal behind the mills. Fog moved in snaky tentacles close over the sagging roofs.

The very air was chill with a nameless life of its own and Doctor Flame, hurrying along behind the woman, felt a deep stirring pity for the miserable people who lived here.

"Wait," said the woman.

Flame couldn't see her in the gloom, but he could hear the labored rasp of her breathing. He sensed that she was listening with a terrible intensity.

"There's no one here," he said.

They crossed the black street and entered a narrow passageway that seemed to open up mysteriously. Flame felt the close press of walls on either side, and he stumbled in a puddle that sloshed icy water over his shoes.

"Here," said the woman.

A key clinked in a lock, and hinges creaked.

"It's a little hall," the woman explained.

She tugged at Flame's sleeve, and he stepped up and inside. It was scarcely warmer here than outside and almost as dark, but there was a slit of light showing under a door.

"It's Bessie," the woman called in a low voice. "I'm back with the doctor. Don't be afraid, dear."

A key clinked again. The door swung back slowly. The woman screamed, crazily.

The room was brightly lighted, and a wood stove gleamed warm against one wall. There were two straight chairs and a sagging table, and an iron cot in the corner.

A man was lying half-under the cot, his skinny legs twisted grotesquely. Blood showed on the front of his gray flannel shirt. He was an elderly man with scanty white hair, and his mouth was open.

Flame started forward, and in the same second he sensed movement in the hall behind him. Before he could check turn, he was struck hard in the middle of the back, and shoved.

He stumbled into the little room. The woman started to scream once more, and the sound was clipped off in mid-note.

Flame caught himself and whirled around. He was just in time to catch a glimpse of a tall man with a sharp face. The tall man had his arm around the woman, holding her, pulling her backward, and his gloved left hand covered her mouth. Her eyes bulged in terror.

Before Flame could move the door slammed in his face, the lock clicked. A voice gave some quick order in the hall, and the outer door banged shut.

It was characteristic of Flame not to shout useless pleas or threats or pound on the door. He stood rigid for a second, breathing hard, listening. Then he turned and dropped on one knee beside the body.

There was no need for a doctor here. The gash across the man's skinny throat had sliced deep. The man had died quickly.

FLAME stood up and strode over to the one window, pulled away the ragged blanket that served as a black-out curtain. The sash was nailed shut and there were heavy boards behind the glass.

He looked at the rest of the room. It was pitiably barren of all personal touches. It had none of the small things that even the poorest people carry with them to make a semblance of home. A tall box at one side served for a clothes closet, and there was nothing in it but one soiled uniform-like dress made of stiff-starched blue cloth.

He went back to the door and listened with his ear against the panel. There was no sound from outside. He opened his satchel, took out a small scalpel and a pair of thin-necked forceps.

Very gently he pushed the forceps into the key-hole. As he had thought, his captors hadn't taken the time to remove the key. He caught its nub deftly with the forceps and turned it. The lock clicked softly.

He dropped the forceps in his pocket and stepped back, holding the scalpel, ready to slash anyone who opened the door. No one did.

After a moment, Flame opened it. The hall was empty. He picked up his bag and went into the dark alley.

He still held the scalpel as he stood for a full minute on the soggy door-step listening.

Dropping the scalpel carelessly into his pocket, he found a match and struck it. The yellow light made shadows dance in jittering malignance.

Flame leaned down, shading the match. The mud in front of the step was smeared by many feet. Still stooping, Flame moved along the passage-way.

He found what he was seeking then. Small foot-prints that would have fitted easily on the palm of his hand. They didn't belong to the woman who had brought him here, or to any man. They had been made by small high heels and a wedge-shaped sole.

Flame straightened up and blew out the match. He was tense standing there in the darkness, uneasy with a chill of foreboding. The woman who had brought him here hadn't lied. There had been a girl waiting—a girl who was thought to be mad and who had gone away leaving death behind her. Flame didn't yet understand the other things that had happened, but he understood madness, and he knew its danger.

FLAME was back in his own neighborhood. He had come up Trailer Street and across Delancy past the now blacked-out Green Clover. He turned into the street where he lived. There was nothing moving in the darkness, save for Flame, until a voice shouted at him shrilly: "Hi, there—Doctor Flame! Wait!" Running foot-steps made a quick thud-thud-thud on the pavement, and a small bundled figure bobbed across the street and pulled to a stop in front of him. "Hi! I was waitin' for you." He was a boy ten or eleven years in plaid macinaw and knitted cap.

"You shouldn't be out during a blackout," Flame said. "What's your name?"

"I was just goin' home from deliverin' my papers. I'm Harry Harkness. My dad runs the Fourth Avenue Precinct Club. You know him—ward captain for this district."

"Oh, yes," said Flame. "Limey Harkness."

"His real name is John," the boy said quickly. "They just call him Limey 'cause he was born in London."

Flame said, "What can I do for you, Harry?"

"There's a crazy dame wants to see you."

"What?"

Harry Harkness stamped his feet. "Gee, it's cold. I told her to wait in your office. I told her you never locked the door. But she's crazy. She gave me a dollar to watch for you."

"What do you mean, crazy?"

"Oh, you know, like all dames. Bawlin' and takin' on. Dames make me sick."

"Where is she?" Flame asked.

"Waitin' in that little alley that goes back to old Moe's junk-yard. I told her that was a dumb place to wait, but dames are nuts."

"Take me to her!" Flame ordered.

Harry Harkness led the way down the block and around the corner.

"Right over there," he said.

The alley-mouth was a pit-black square bordered by the buildings. Flame slowed to a casual walk.

"I don't see anyone," he said.

"I don't neither," Harry Harkness admitted. "She's probably hidin'." He cupped his hands and shouted. "Hey! Hey, you! Here's Doctor Flame!"

The wind whisked his words away, and there was no answer, no stir of life from the alley. Harry Harkness plunged into it unhesitatingly.

"Hey! Where are you, dopey?"

Flame went after him. "Wait, Harry! Come back here!"

Harry's voice came out of the darkness. "She ain't here at all. She paid me to watch for you and then she beats it! Ain't that like a dame?"

He blundered back toward Flame, who caught him by one arm and steered him out into the lesser darkness of the street.

"Are you sure she's not there?" he asked.

"Yup," said Harry. "There ain't no place to hide in there. I felt all around."

"Could she go out the other end?"

"Nope. Old Moe's got a gate there. He keeps it locked. It's got barbed wire on it. I can't climb it, so no dame could."

Blue head-lights turned the corner above, and a car slid down the street. It flowed past them, and then suddenly halted.

"Gee!" said, Harry Harkness. "Cops!"

THE car was a new gray sedan, with police insignia painted on the doors. It backed rapidly until it was even with Doctor Flame and Harry. A man opened the door and slid out from under the wheel.

"Gee!" Harry Harkness repeated. "It's that old sour-puss, Inspector Conniston!"

Conniston was a tall man, erect and square-shouldered. His eyes were a cynical blue. He was wearing a dark tailored top-coat and a dark hat.

"I want to see you, Flame," he said in his clipped speech. "I was on my way to your office."

"I want to see you, too," said Flame.

"Yes," said Conniston. "I can imagine. Were you down on the Flats back of Trailer Street about a half-hour ago? Don't lie—"

"I was there."

"Damn you, Flame," Conniston said irritably. "You can get into more trouble than any other six people I know. Don't you have any regard for your friends? Don't I have enough worry keeping this lousy district in line without you going around stirring things up?"

"You'll manage," Flame said, smiling.

"No thanks to you," Conniston snapped. "I'll be damned if I can understand why you ever came to this rat-hole, but I'm tired of arguing about that."

"Have you heard any news?"

"No. The police are still on precautionary status. What were you doing down in Feegan's Lane?"

"How did you know I was there?" Flame asked curiously.

Conniston made a stiff gesture. "Some stool-pigeon said Doctor Flame was locked in a room with a murdered man. We found the corpse, all right, but not you."

"Who was the victim?"

"Name of Simpson. A bum. He lived up-stairs over the room where he was found. He was sort of the agent for that tenement. He had a record as a drunk, but he'd never been pinched for anything more serious than that. What do you know about him?"

"Not as much as I'd like to," Flame answered. "I really did want to see you. I was on my to my office to call you. I wanted to talk to you before you did anything. But since then there's been a new development. Harry tells me that—where did he go?"

Conniston said, "The kid? Oh, he ran off like a rabbit when he spotted me. All the kids in this district do that. You'd think I had small-pox. What is this one's name?"

"Harry Harkness. His father is Limey Harkness."

"That slick little blabber-mouth. I'd like to put him where he belongs, and one of these days I will."

"I've always heard he was reasonably honest."

"He's a politician," Conniston said flatly. "All politicians are lice."

Flame chuckled. "You hate almost everybody, don't you?"

"Yes," said Conniston. "And so would you if you were a cop. Now tell me about Simpson."

Flame explained about the woman who had come to see him; about her friend who was supposed to be insane, and about his trip to the Flats.

CONNISTON listened. "So," he said quietly. "A nice dish you've cooked up. A homicidal maniac loose. If that gets out it'll set this place off like a time bomb."

"Homicidal mania is a much rarer form of insanity than people think," Flame said.

"Not rare enough for me. I can figure out what happened easily enough, even if you can't. This dippy dame escaped from wherever she was locked up and got this other dame—the one called Bessie—to hide her. Old Simpson got to prowling around to see what was going on, and the crazy one slit his throat. And she's still loose with whatever she used."

"A razor, I think," Flame observed.

"That's dandy. Why didn't you stay down in the Flats? Or phone me right away?"

"I wanted to talk to you personally first. I didn't want you to throw out a drag net for this girl."

Conniston stared at him. "Why not?"

Flame frowned absently. "I haven't seen the girl. I was guessing from the barest sort of description of her symptoms, but paranoia is a most dangerous mental disease. Paranoiacs see the devil's face everywhere they look. Everyone seems to be threatening them. If this girl has such tendencies, the police will drive her completely mad. The results might be worse than you think. She might slash at anyone she sees."

Conniston swallowed. "You mean she might run amok?"

"Something like that."

Conniston cursed to himself. "And I have to look for her during a sample blackout that's liable to turn real any minute!"

Flame said: "I think you were right about one thing. She was locked up somewhere and escaped. Someone was looking for her—someone Bessie feared. Find out where she was locked up and who she is. If she is a paranoiac, she must have been under the care of a doctor. Find him."

"How?" Conniston demanded.

Flame shrugged. "I don't know."

"That helps," said Conniston. He stood still, chewing on his upper lip. "All right. But if I don't turn something up soon, I'm going to throw a drag-net around this whole district—black-out or not—and search it from rat-hole to rat-hole!" He got in his car and slammed the door.

THE instant that Flame entered his office, he knew that at least a part of his quest was ended. The girl was there. The office was dark. He could not see her, but he could feel her presence. She was watching him, like a cornered animal, with a horrible strained intensity.

Flame moved carefully. He made no attempt to turn on the light. He shut the door behind him and leaned against it. She was on the far side of the center table. A floor board creaked there.

Flame said quietly: "Would you rather we'd talk in the dark?"

He could hear her breathing—quick shallow gasps that filled the darkness with terror. He waited patiently, not moving, and then her voice came in a hoarse whisper:

"If you try to keep me here, I'll kill you."

"I don't blame you," said Flame.

"I can do it. I've got a razor."

"Yes," said Flame gently. "Keep it in your hand. Then if I come near you, you can kill me."

Her breathing quieted. Flame could see her vaguely now—a dark shadow beyond the table.

"Everyone—even that little boy—said you could be trusted. Will you promise to let me go when I want to?"

"I promise," said Flame.

"Turn on the light."

Flame flipped the switch, and they were looking at each other. She was very small, and her face was a white oval with small perfect features that were haggard. Her eyes were a luminous black. She was wearing a black tailored coat, and a blue scarf around her hair.

"Hello," said Flame, smiling.

She moved her right hand, and the oblong blade of a razor shimmered. "Stay where you are."

"I will," said Flame.

She relaxed some. "Will you help me?"

"Yes," said Flame.

"Will you give me some money?"

"You're welcome to what I have. It's in my wallet in my inside coat pocket. Can I take it out?"

She leaned forward. "Yes."

Flame took out his battered wallet. He found three crumpled bills in it—Papa Rizzio's contribution from the family sugar bowl. A five and two ones. He put them on the table carefully and stepped back.

The girl swept them up in her left hand. "I'll pay you sometime. I have to have it now to get out of this district before the black-out lifts. I can't hide here. Everyone stares at me and watches me—everyone I meet."

"Of course," said Flame.

Her eyes gleamed. "Why? Why should they?"

FLAME looked surprised. "Your clothes. That coat must have cost a hundred and fifty dollars and the scarf twenty-five. People don't see things like that down here."

"Oh," said the girl. "I didn't realize. That is true, isn't it?" Her face tightened. "I've got to go. They'll find me."

"It is dangerous," Flame agreed in a worried tone. "You'd better go now."

"You—you're really going to let me go?"

"Why, yes," Flame said. "Use that side door back of you. No one will see you from the street."

"Can I come back later?"

"Oh, no," Flame said quickly. "They might see you. You find a safe place to hide and then call me. I'll come to you."

"Thank you," the girl said breathlessly.... She slid out the side door like a wraith, never taking her eyes from him until the door closed. Flame stood listening for a moment and then sighed deeply. He took off his broad-brimmed hat. There was a sheen of perspiration on his bulging forehead.

He had just made a decision no lesser man would have faced for a second. He had used his judgment in a gamble that made him shiver. If he lost, he would have to pay the reckoning. It would be a terrible one.

Behind him the door-bell split the silence with a sudden shrill clamor. He opened the door, expecting to see almost anything in the world except the dandified little man who faced him, standing erect with his carefully brushed derby canted over one arm and his slick blond hair gleaming.

"Good evening, Doctor," said the little man in a faintly English voice. "It's Limey Harkness, at your service. I've a specimen here that I think might interest you."

"Someone sick?"

"He isn't—yet," said Limey Harkness. He turned his head. "Bring him up."

Feet scuffled on the stairs. Somebody grunted heavily and someone else whimpered a little. Limey Harkness stepped neatly aside, and a man stumbled into the room and fell into the wall.

FLAME caught a glimpse of the men who had shoved him. There were two of them—big and heavy-shouldered, one with a flattened nose. Then Limey Harkness said:

"Wait there, boys." He shut the door. "Now here it is, Doctor. A low fellow by the name of Stevane."

Stevane was a miserable specimen even for the slums, dirty inside and out. His face must have been pale enough normally, but now it was as white as paper. One sleeve of his ragged coat had been ripped out. He had no hat, and his colorless hair stuck up in clumps. He was crying.

"What's the mater with him?" Flame asked.

"He's a dirty copper's nark," said Limey Harkness. "A stool pigeon."

"No!" Stevane whimpered. "I'd never—"

"Quiet," said Limey Harkness. "You'll speak when you're asked. My boy Harry is a smart one, Doctor. He heard what Conniston said to you about someone tipping the cops off to you, and he came and told me. So some of the boys went out to knock on a few doors. Sure enough, they were soon talking to Mr. Stevane. He's the one who called copper on you, Doctor. Aren't you, Stevane? Speak up and answer right."

Stevane gulped. "Yes."

Limey Harkness smiled at him. "That's nice, Stevane. Now tell the doctor how much you wish you hadn't done it."

Stevane stared at Flame with horribly bulging eyes. "Honest, I never meant— I never thought it'd make any trouble for you—Please don't—don't let 'em—"

Flame made a little distasteful gesture. "Never mind that. I don't care what you did, but why did you do it?"

"Don't lie, Stevane," said Limey Harkness. "You wouldn't want to go where you're goin' with a lie in your mouth."

Stevane strangled a terrified sob. "It was a fella by the name of Troop. He used to be a detective—loft squad. They caught him pointin' jobs for some of the boys that knock over fur vaults, and they booted him off the force. He—he knows plenty about me. He could send me away—"

"And don't you wish you were safe in jail?" Limey Harkness asked casually. "Instead of here with me? Keep right on talking, my dear fellow. Go right ahead."

Stevane's voice was a breathless mumble. "Troop said I hadda help him find a dame. She was down here somewhere, livin' here. Name of Bessie Rainey. He had it narrowed down. She was livin' in the Flats. He'd seen her comin' out of there and almost caught her, but she got away. He said he'd pay me fifty bucks if I'd find her, and if I didn't—"

"So you found her," said Limey Harkness. "Get on with it."

Stevane nodded stiffly. "Old Simpson was one of the guys I thought of first. I knew he picked up side-money hidin' out fellas that was hot. I took Troop over there and—and—"

"Yes?" said Limey Harkness gently. "And?"

"I never did it," Stevane said with a sort of numb desperation. "I never—never—"

"Troop did it, then," said Limey Harkness.

Stevane's dry lips opened and shut. "Yes!"

"You're a liar," said Limey Harkness, and reached for the door knob.

"Yes!" Stevane shouted in sudden frantic terror. "I mean no! Troop didn't do it! But neither did I! Honest—I never did! I couldn't find old Simpson. I went around to the back and looked for him, and the door was open, and there he was on the floor with his mouth open...."

"Never mind all that," said Limey Harkness. "The doctor and I have seen quite a few dead ones and expect to see a few more before we get through. What did you do?"

"I shut the door. I was scared an air raid warden would spot the light. I went back to the car...."

"Car?" said Limey Harkness softly. "During a black-out? Whose car?"

"Troop's," said Stevane.

"No," said Limey Harkness. "Whose?"

Stevane moistened his lips. "Troop told me it was his."

LIMEY HARKNESS smiled again. "Maybe you think I'm joking, Stevane. Troop probably did tell you the car was his, but you know it had to have special permission to drive around during a black-out. They don't hand out permission to people like Troop. You're the kind that would snoop around a bit. Whose car was it, Stevane? You answer that—now."

"You got to give me a chance. If Troop finds out that I—"

"Why, you fool," said Limey Harkness. "You poor fool. Are you more afraid of Troop than of me? Why then, just say good-by to the doctor, and we'll be on our way."

Stevane's whole scrawny body began to shake uncontrollably. "No, no, no! You can't—you wouldn't—It was a fat guy by the name of Doctor Ogelthorpe!"

"Are you sure that was the name?" Flame asked.

"Yes," Stevane whispered. "Let me out of here. I don't know nothin' more, I swear it. I only called in after Troop grabbed the old dame because he said he'd turn me up for the job unless I peached on Doctor Flame."

Limey Harkness looked at Flame and raised his eyebrows in polite inquiry.

"Let him go," said Flame.

Stevane mumbled thanks in a blubbering breathless voice, watching Limey Harkness like a rabbit watches a snake.

Limey Harkness opened the door. "Let him go, boys."

Stevane ducked out through the door. Limey Harkness shut the door softly.

"Not nice to think about, Doctor. I mean, people as low as that. There aren't many of them about, and now there'll be one less. Tomorrow everyone will know he called the cops on you. If he ever shows his face around here again, he'll be smashed like a bug in two minutes flat. This Troop, now. I don't know who he is or who his doctor friend is or what they are to you, but I could have them looked up if you wish."

"No, thank you," Flame said.

"Then if there's nothing else, I'll be running along." Limey Harkness put his derby on carefully and straightened the front of his neat overcoat with two quick deft hand-pats. He was still smiling in his casually incurious way.

"Good night, Doctor," he said. "I trust I'll have the pleasure of seeing you—"

"Wait," said Flame. "I haven't thanked you—"

"That's not necessary. That's how I get out the votes."

Flame smiled. "Did you do all this just to get me to vote for the candidates you back?"

"No," said Limey Harkness. "I did it so other people would. You have a great influence in this district."

"Wait," Flame repeated. "Aren't you—curious about all this?"

"No," said Limey Harkness. "I'm never curious." He nodded courteously and slipped out the door.

Flame shook his head absently. The queer and devious ways that the slum people took to serve him had surprised him a good many times in the past, and this was another instance in the long line of them. He had a great many other dangerously pressing things to consider now. He located a state medical directory and began to leaf through it.

THE cab drew up at the quiet intersection and slowed as the driver felt for the curb. He set the hand-brake and looked over his shoulder.

"This is about the best I can do. I can't look for house numbers without usin' my spot, and they'd have my license in ten seconds if I tried that during a black-out. The place should be on the left side of the street up about a half-block."

"This is fine," Flame told him. He signed his name and emergency permit number in the driver's call book. "I'm sorry I haven't any change."

"I wouldn't take no dough from you," said the driver. "You want I should wait?"

"No, thanks," said Flame. He got out, carrying his medical satchel, and the cab puttered away in the darkness. This was the exclusive residential section north of the city. The air felt clean and tingled in Flame's nostrils. Even the stars were closer and brighter. There were no other lights anywhere.

Flame stepped across to the sidewalk, and then a voice said: "One moment, please."

Flame stopped. Feet scuffed on cement, and then a dimmed flash-light outlined the faint bulk of the man holding it.

"Air raid warden," he said, coming closer. "May I ask where you're going?"

"To Twelve-twenty-two Teakley Place," Flame answered. "I'm a doctor. Here's my emergency permit."

"Thank you. That's the Blaine house. I'll take you there."

Flame said: "I was looking for a Doctor Ogelthorpe."

"Yes. He lives at the Blaine house. This way. Be careful. The curb is high here."

"Have you heard any news about the air raid?" Flame asked. "No."

Flame chuckled. "How many times are you asked that during a raid?"

"Seven thousand on the average," said the warden. "Of course, we haven't had many black-outs here as yet and people aren't used to them. They're doing all right, though. This hedge circles the Blaine house."

THE hedge was like a dark wall close against the edge of the sidewalk, high and thick, its dried leaves rustling a little in the dead silence.

The warden flicked on his dimmed light. "This is the gate. The front entrance is straight down the path. Do you want me to take you to the door?"

"No, thanks," said Flame. "Good-night, then." His feet clicked away, and Flame pushed the wrought iron gate open and felt his way along the flagged walk toward the house that loomed huge and ghost-like before him. He stumbled against broad steps and then went across the width of a porch and groped until he found a bell.

The door opened instantly, and Flame slipped through it. He was dazzled for a moment by the bright lights in the high-arched hall. He shut the door, blinking at the man in front of him.

THE man had stepped back in surprise, and now he was staring at Flame with impersonal curiosity. He was enormous, fat without looseness, and his face was a pallid circle with eyes that were like black beads. His hands were disproportionately small and delicate, and he wore tiny patent leather shoes. "Who are you?" he demanded.

"My name is Flame," Flame said. "I'm a doctor."

The beady eyes sharpened a little. "Doctor Flame? I don't think I know that name."

"Yours is Ogelthorpe, isn't it?"

"Yes. What of it?"

"I have something to say to you."

Ogelthorpe's tight lips moved in a disdainful smile. "I don't think I'd be interested, Doctor—ah—Flame. I have a patient here who requires undisturbed rest. The air raid warning has disturbed her enough as it is. I'll ask you to leave this house."

"I'm not going," said Flame, "until I learn a little more about your patient. Where is she?"

"In her bedroom, of course. She's very weak. What business is it of yours?"

"I've made it mine. What's her name?"

"Mrs. Turnbell Blaine. This is her home."

Flame said: "The medical directory gives this as your address and doesn't list you as having an office."

"I live here," said Ogelthorpe in a coldly patient voice. "I am not engaged in general practice. Caring for Mrs. Blaine takes a great deal of my time. I don't think you have any authority to question me, and again I'll ask you to leave."

"Not yet," said Flame. "What is the matter with Mrs. Blaine?"

"Nothing but age and a recurrent heart condition."

"Age?" said Flame, puzzled.

Ogelthorpe nodded. "Yes. Mrs. Blaine is seventy-seven years old."

"I don't believe you," said Flame.

Ogelthorpe moved his massive shoulders. "That's your privilege. Inquire at any of the neighbors, if you wish. They all know Mrs. Blaine. She has lived here most of her life. Your insolence has aroused my curiosity, Doctor Flame. Just what is the point of this questioning?"

Flame watched him. "You employ a man named Troop."

"No, I don't," said Ogelthorpe blandly.

Flame tried a shot in the dark. "You were seen in his company tonight in the slums."

"The slums," Ogelthorpe repeated, raising his eyebrows lightly. "I see. You're from there. That accounts for your rather—ah—peculiar costume. I wasn't seen there tonight in the company of anyone, because I've never been there in my life. This questioning is quite pointless, Doctor Flame. I can prove the truth of everything I have told you, and I will do it if I'm asked by the proper authorities. I think you'd better go back where you came from. Perhaps the black-out has made you a little hysterical."

"A man Simpson was murdered tonight," Flame told him.

"How very interesting," said Ogelthorpe. "Are you leaving?" He stood immovable, watching Flame contemptuously, and there was no break in the smooth wall of his self-assurance.

FLAME stared back. The whole pattern that he had reasoned out of the events and the queerly dark hints that he had seen and heard this night was breaking up. Ogelthorpe was too sure. He probably could prove what he said, and if so, Flame had been wrong all along.

A squeaky voice shrilled suddenly: "Who's that you're talking to, Doctor Ogelthorpe?"

Ogelthorpe whirled around, sure in his movements despite of his bulk. "Mrs Blaine! You shouldn't be up!"

She was half-way down the long wide sweep of the stair-case—a grotesquely shrunken little figure with her scanty white hair frizzed up and fastened in metal curlers, dressed in a pink robe with the white of a long nightgown showing below it. She was grasping the stair railing with claw-like hands, and her head jerked in little bird-like motions.

"I shouldn't be up!" she echoed triumphantly. "But I am, I am! And that fat old nurse is down! Because I gave her my medicine! And now she's snoring with her mouth open. I stuck her with a pin and she didn't budge!"

"Rather strong medicine to give an old lady with a heart condition," Flame observed.

Ogelthorpe's beady eyes flicked toward him. "Nothing but a very mild sedative—entirely harmless. The old lady is affected with senile dementia. She exaggerates."

"What's that?" Mrs. Blaine shrilled. "What's that you're saying about me?" She came on down the steps, swaying jerkily, holding on to the railing. "Where are all the servants, that's what I want to know!"

"This is their night off, Mrs. Blaine," Ogelthorpe said smoothly.

"Night off!" she echoed angrily. "Tis not! This is Tuesday! Their night off is Thursday!"

"I told them they could go tonight," Ogelthorpe said. "You must go back to bed, Mrs. Blaine."

"You told them they could go tonight? Why?"

"Yes," said Flame. "Why?"

Ogelthorpe turned toward him. "I'm telling you for the last time, Doctor Flame. Get out of here." He didn't raise his voice, but there was danger in its tone.

"No, you don't!" said Mrs. Blaine. "Oh, no, you don't, Doctor Ogelthorpe! This is my house, and I want to know what that funny little fellow is doing in it. Who is he?"

"His name is Flame," Ogelthorpe snapped. "He's a quack doctor from the slums."

"Quack," Mrs. Blaine repeated, peering eagerly. "A quack, eh? He doesn't look like a quack to me. If he was a quack he'd be dressed better—like you, Doctor Ogelthorpe."

"That's enough!" Ogelthorpe said. "I am going to take you back to bed."

"No! Not until I see Elinor."

"She's asleep. You can't see her."

"Oh, yes I can!" Mrs. Blaine said defiantly. "I won't wake her up, but I'm going to see her! I've got a feeling you're hiding something from me!"

Flame's deep-set eyes were gleaming. "Who is Elinor, Mrs. Blaine?" he asked.

"She's my grand-daughter. What business is it of yours?"

"I think she's a patient of mine," said Flame.

THE silence congealed in the hall, and even Mrs. Blaine seemed to feel it. She drew her robe closer around her skinny throat.

"Damn you," said Ogelthorpe. "Now you've done it. It's your responsibility."

"I'll take it," said Flame. "Let's look at your grand-daughter, Mrs. Blaine."

Mrs. Blaine looked old and tired and very confused. "She's sick. Her mind's sick."

"Yes," said Flame. "Let me have a look at her."

"All right then, damn you," said Ogelthorpe. "If you must have it. Elinor is a dangerous paranoiac. I've been keeping her here at home—under my care—instead of sending her to an asylum where she belongs because I wanted to save the Blaine family from any scandal."

"Elinor—Elinor wouldn't harm anybody," Mrs. Blaine protested weakly.

"Oh, wouldn't she?" Ogelthorpe said brutally. "Well, she escaped tonight and killed a man down in the slums. Cut his throat. That's what brought this little quack down on us. I was trying to save you from the shock of knowing that, and I would have if he'd minded his own business."

Mrs. Blaine swayed. "Killed—killed—"

"Yes!" said Ogelthorpe. "I told you she was dangerous. I warned you. It's your fault. You hired that damned old Bessie, that came around begging at the door. I told you not to. She helped Elinor escape."

Mrs. Blaine stared at him, her withered lips working silently. She finally forced words out:

"Where—where is Elinor?"

Ogelthorpe spread his small hands, palms up-ward. "I don't know! Bessie helped her to hide in the slums. I searched everywhere down there for her. I found Bessie, but Elinor got away again—after she'd murdered a man. You didn't want any scandal, did you? Well, you'll have plenty now."

Mrs. Blaine clutched at the bannister frantically. "They'll—arrest...."

"They certainly will," Ogelthorpe agreed. "They'll arrest Elinor now and put her away in the State Asylum for the rest of her life."

"I'm not so sure of that," said Flame.

"What?" Ogelthorpe said blankly.

Flame said: "Mrs. Blaine, your granddaughter is not a paranoiac. She is not insane in any ordinary sense of the word. She is suffering from a severe case of hysteria exaggerated by narcotics and other—treatments Doctor Ogelthorpe has given her."

Ogelthorpe's thick lips curled. "And what do you know about paranoia?"

"Quite a lot," said Flame candidly. "An article I wrote about it is required reading in ten medical colleges."

Ogelthorpe's pallid face went a shade whiter, but he didn't lose control of himself. "Perhaps that's true, but you don't know anything about Elinor. You've never seen her."

"Yes, I have," said Flame. "I examined her. I say now—and I'll swear it—that she's not a paranoiac or any other kind of a maniac and never was and that any signs of mental uncertainty she may exhibit are the results of your treatments."

"You—saw her?" said Ogelthorpe slowly.

"Yes."

"Where is she?"

"I don't know."

OGELTHORPE watched him for seconds and then shrugged his shoulders with a fatalistic movement. "Then we'll have to do it this way," he said. He withdrew from his coat pocket an automatic. "Troop, come here."

The tall man with the sharp face stepped into view. He was carrying a Police Positive.

"I told you," he said. "He's too smart for us."

Mrs. Blaine stumbled down the stairs. "What is it? What are you doing?"

Ogelthorpe said, "Mrs. Blaine, this man is a dangerous fake. He treated Elinor, and now he thinks he can cash in on it through blackmail. I'll see that he doesn't. You must go to bed now. Take her upstairs, Troop."

Mrs. Blaine struck weakly at Troop. "No! No, I won't go! He's not a fake! You are, yourself! You'll not hurt him, do you hear? He's to stay and tell me—"

"If you move, Doctor Flame," said Ogelthorpe, "I'll shoot. Believe me!"

Troop swung Mrs. Blaine's small body up easily in his arms and started up the stairs. Mrs. Blaine cried out weakly again and again, like a lost child.

"Make her swallow one of those tablets in the green bottle in the bed stand drawer, Troop," Ogelthorpe ordered. He had not lost his self-assurance, and as Troop and Mrs. Blaine disappeared at the top of the stairs and the child-like cries died away, he nodded slowly at Flame. "Things are clear to you now, I suppose?"

"Yes," said Flame. "It wasn't a nice story when I first caught a glimpse of it, and it's no nicer now. You worked your way into the confidence of Mrs. Blaine."

"Quite," said Ogelthorpe.

"And then the grand-daughter interfered with you."

"She came home from school," Ogelthorpe said. "She didn't trust me. Surprising, isn't it?"

"Not very," said Flame. "You knew she would undermine the old lady's confidence in you, so you went to work first. You persuaded the old lady that Elinor was insane and then provided proof enough to convince her. An old lady made miserable and a girl tortured until she has almost lost faith in herself. You must feel very proud of your accomplishments."

"There's no need for that," Ogelthorpe said flatly. "I was playing for higher stakes than you could even conceive. The old lady has almost five million dollars and no near relatives except her granddaughter. I wanted just a piece of it at first, and then I thought I might as well have it all. Now I have. I'm the sole executor of the estate. It's all left for me to manage for the benefit of poor Elinor until she—oh—regains her sanity."

FLAME said evenly: "Mrs. Blaine knows what you've done now. She'll change her will."

"She won't," said Ogelthorpe. "Because I'll see that she doesn't. Even if she did, I'd swear that she was mentally incompetent to make a will. No doctor has seen either her or Elinor for the last year. It's my word and my word alone. That will be enough."

"You're forgetting one doctor," said Flame.

"You?" said Ogelthorpe. "No, I'm not."

Troop came down the stairs. "The old lady's out like a light, and that dim-witted nurse is snorin' like a flight of bombers."

"Good," said Ogelthorpe. "Now you—"

From back in the darkness of the big house there was the faint tinkle of breaking glass.

"That Bessie—" said Troop. "I tied her—"

"Go back and see what happened!" Ogelthorpe snapped. "Quickly! Doctor Flame, do not move. I warn you."

Troop ran back along the hall and through the rear door. He was back in a second, breathing hard.

"She's gone! Bessie's gone! She couldn't have gotten loose herself—not the way I tied her! The window's broken from the outside, and the ropes cut—"

"With a razor," said Flame, his voice very low.

"Yeah," said Troop. "They look like they were...."

Ogelthorpe's beady eyes gleamed. "How did you guess that?"

"Elinor had a razor when I saw her," said Flame.

"Elinor had—" Ogelthorpe stopped and swallowed. "And you let her go—with that? You criminal fool, she thinks she's insane! I've told her often enough that she is! I've convinced her, and if her mind has slipped...." He hesitated, biting his lips.

"This is gittin' too fast for me," Troop said slowly.

Ogelthorpe was still glaring at Flame. "Anything that happens.... If Elinor harms anyone, it's your fault! You'll be done for!"

"So will you," said Troop. "You can't buck this bird. He's got more pull with the police department than the mayor has."

"Shut up," said Ogelthorpe, recovering himself. "We're all right. Elinor and Bessie can't get far in this black-out. They haven't any money or any place to go. We will find them. And when we do, we'll have that murdered man down in the slums to hold over their heads. We'll be better off than we were before!"

"Except for this guy," said Troop.

"Yes," Ogelthorpe agreed. "Except for Flame. But you'll take care of him. You'll make it look like Elinor...."

Troop's thin face looked cruelly triumphant. "Sure. But there'll be no more of this 'sir' stuff to you. There'll be no more orderin' me around like I was your valet. We're fifty-fifty after this."

"Yes," said Ogelthorpe. "Certainly."

Troop grinned wolfishly. "I know what you're thinking, chum. I'm watching you."

"Get Flame out of here," Ogelthorpe said.

Troop walked around behind Flame and shoved his revolver hard against Flame's back. "Feel that? It's cocked. One jiggle from you, and she blows."

Ogelthorpe's voice was smooth and thick again. "I'm very sorry, Doctor Flame. I abhor violence. But it is necessary now, and you were warned. If you hadn't meddled...."

"March," Troop ordered, pushing with the revolver. "Out the back way. Get moving."

Flame walked steadily down the hall in front of him and through the door opposite the one Troop had used before. They went through a dining room with a long table gleaming lustrously in its center, through a narrow dim pantry and into the spicy-smelling cleanliness of a darkened kitchen.

The revolver still pressed warningly against Flame's back. "That door," said Troop. "Right ahead. Open it."

"All right," said Flame.

"You're a cool one," Troop told him. "Do you think you'll get out of this? Do you think you can buy me off? Not unless you've got five million in your pocket, you can't. Oh, I've got that fat slob where I want him now! I'll pay him back for a few things I've taken! Don't try to run for it in the dark. You won't get far."

In pitch darkness they went across an enclosed porch and down two flat steps to a graveled walk.

"Straight back on the path," said Troop. "We're goin' to the garage and take a ride. The car's got a doctor's plate on it, and we won't be stopped. If we do, keep your mouth shut tight. We're goin' back to your office."

THE gravel crunched slightly under their feet, and the squat low bulk of the garage loomed ahead of them. There was a sudden metallic slam and clatter, and then a voice said angrily:

"Klogatz, will you kindly watch your clumsy self and make less noise? I am listening for enemy bombers."

"You do not know enemy bombers," said Klogatz.

"You lie in your teeth," said O'Phelan. "I do so. They snore like an old sow. I think there's one up above now, and it's us that should be getting medals by the dozen, Klogatz. Going on with our work silently and bravely with our very lives in danger."

"Stand still!" Troop hissed in Flame's ear.

"Be quiet!" Klogatz said abruptly. "There is someone close to us."

"What?" said O'Phelan. "Where? Who is it?"

Silence seemed to fold down over the yard, and there was no noise at all until O'Phelan's voice sounded very close, just at Flame's left.

"Well, now. Here we are. Two of them. A tall one and a short one."

"Stand back!" Troop snapped. "This is an emergency! We're taking the car out of the garage!"

"Klogatz," said O'Phelan. "Did you hear that voice? I think I've heard it before tonight. Let's see."

There was a snap and a flashlight, shielded by O'Phelan's palm, made a dim red glow.

"Well, now," said O'Phelan in a pleased tone. "Will you look what we have here, Klogatz?"

Troop jumped back and away from Flame, his revolver gleaming dangerously. "Stand back, you! I'm an officer, and I'm arresting this man! Stand back or I'll shoot!"

"Did you hear that, Klogatz?" O'Phelan asked. "You wouldn't interfere with an officer in the pursuit of his duty, would you?"

"Yes," said Klogatz.

"Then do it!" said O'Phelan, and snapped off his light.

Troop's revolver made a blasting roar of sound and a smeared powdery flash in the darkness, and then there was the sharp smack of flesh against flesh and a thudding scrambling tangle on the ground.

O'Phelan touched Flame's arm gently. "'Tis nothing at all, Doctor. We had a word with this fellow earlier, and we don't like him. He was chasing a woman, then. It seems he's a bit free with his gun. Klogatz, do not kill him entirely just yet. Did he hit you?"

"No," said Klogatz. "Did he hurt the Doctor?"

Flame drew a long deep breath. "Not a bit. He would have, if it hadn't been for you two."

"Is that so?" said O'Phelan. "Hit him again, Klogatz."

"It does no good," said Klogatz. "He is unconscious. Maybe his neck is broke."

"We can always hope," said O'Phelan. "Now what is all this, Doctor, if you'll tell us, please?"

Flame said: "This man and another wormed their way into the confidence of the old lady who owns the house back of us. She had money and they wanted it. When her grand-daughter tried to protest, they pretended the girl was insane and shut her up and kept her a prisoner. Perhaps they even succeeded in driving the girl mad. I don't know yet."

"A dirty business," said O'Phelan. "An old lady and a girl and these two crooks after the money they could steal and lie and cheat away. Maybe you'd best make sure that one's neck is broke, Klogatz."

"It is," said Klogatz.

"Then we'll talk to the other one," said O'Phelan. "Come along."

"No," said Flame. "You don't understand. It's very dangerous. He's desperate and he's armed...."

"So are we," said O'Phelan. "Give me that gun he was waving around, Klogatz. Come along now, Doctor."

THE three of them went back along the path and across the back porch into the quiet darkness of the kitchen. They were half-way across it when the pantry door burst open ahead of them, and Ogelthorpe shouted:

"Troop, you fool! Why did you shoot? You'll bring the air warden—"

Klogatz hit him from the side and spun him around and knocked him into the wall with a jar that shook the room. Ogelthorpe screamed as shrilly as a woman, and then Klogatz said:

"I have his gun. His fingers are broke." Ogelthorpe's cry stopped in mid-note, but there was another scream above and over it that went on higher and higher, full of bubbling unending terror that was beyond endurance.

"Bring him along!" Flame snapped. He ran through the dining room and along the hall, following the sound that filled the house with its hysteria. His feet drummed thunderously on the stairs, and then he was in the upper hallway and there was a lighted doorway bright ahead of him.

It was a bedroom, softly lighted and furnished for the care of an invalid, with radio and book-case and low medicine table next to the wide high bed. The bed clothes were all crumpled and twisted now and horribly spattered with red.

Mrs. Blaine was curled into a rigid agonized little ball, and the blood had come from between the skinny fingers on her hands that were both clutched tight around her throat. Flame had no eyes for her after one swift glance told him she was beyond all human help.

There was a numb dread twisting him as he stared at the girl named Elinor. She was standing rigid at the foot of the bed, and she was holding a razor in her hand. The blade was not clean now.

It was she that had been screaming, and she stopped as sobs welled up and strangled the sound. Her face had lost all semblance of sanity.

"Glory!" said O'Phelan in a whisper from back of Flame: "She's a maniac!"

Ogelthorpe, struggling in Klogatz's grip, cried shrilly: "This will be your end, Flame! This is your doing! You let her loose with that razor—"

"Shut him up," said Flame tightly.

KLOGATZ'S thick fingers clamped over Ogelthorpe's mouth. Flame looked slowly around the room. A fat woman in a nurse's uniform was dumped into the corner like a heap of unclean laundry. She was snoring in gurgling thick gasps, still asleep under the influence of Mrs. Blaine's medicine in spite of the uproar around her.

"That razor in her hand," O'Phelan whispered, staring with dread fascination at Elinor. "She'll be coming for us...."

"Be quiet," said Flame. "Stand still." He stepped forward, one long pace and then another, and Elinor seemed to realize his presence for the first time. She turned her head slowly and stiffly.

"Elinor," said Flame slowly and calmly. "I've come to see you."

"... see me," she echoed. Her eyes glittered inhumanly, watching him. "I'm Doctor Flame. You know me."

"... know you," said Elinor tonelessly.

"Yes," said Flame. "Look at me, Elinor. I'm your friend."

"... friend," said Elinor, and there was a question in her voice.

"Elinor," said Flame. "Look at me. I'm your friend. I'm helping you now. Put the razor down."

A muscle in her thin face twitched.

Flame said slowly: "Put the razor down. Put it down on the bed, Elinor."

Stiffly, like some mechanical puppet, she turned and put her arm out and opened her red-stained fingers. The razor dropped on the bed.

Elinor turned her glance away from Flame to look at it, and then all the stiffness went out of her body and she collapsed, falling to the floor.

"Oh, glory!" O'Phelan was awed.

Ogelthorpe got his mouth free from Klogatz's hand. "Hypnotism! A quack's trick, and you won't get out of this—"

Klogatz's fingers clamped down again.

O'Phelan swallowed hard. "Doctor, did you really let her go with that razor when you knew...."

"Yes," said Flame quietly. Perspiration glistened on his face, and he glanced around the room with desperate intensity.

Then he breathed deeply once. He touched O'Phelan on the shoulder and pointed toward the closed door across the room and then toward a chair.

"Oh," said O'Phelan.

Flame went quickly to Elinor and dropped on one knee beside her and felt for the pulse in one limply out-flung wrist. After a second, he got up and took the white telephone from its stand.

HE dialed a number and waited, watching O'Phelan drift quietly across the room with the chair in his hands. At the closed door, O'Phelan put the chair down and braced its back firmly under the knob. He looked at Flame inquiringly. Flame nodded.

A voice in his ear said: "This is the police department."

"Inspector Conniston, please," Flame requested. "It's an emergency."

The line clicked and Conniston said: "Yes? What is it?"

"This is Flame."

"Oh, you! The black-out has just been lifted, and I'm starting that house-to-house search at once. There's been no report of any insane person escaping from anywhere, and I can't take a chance on delaying any longer. That girl might murder a half-dozen more people—"

"I've found her."

"Where?" Conniston barked.

"Here at her home. Her name is Elinor Blaine. She lived with her grandmother, Mrs. Turnbell Blaine. She was being treated for paranoia by a Doctor Ogelthorpe, and she escaped tonight. Mrs. Blaine has just been murdered."

"Murdered! Wait while I put that out on the radio!" Conniston's voice withdrew to an excited mumble and then came back closer again. "Flame! The prowl car will be there in five minutes! What happened?"

"A doctor named Ogelthorpe and a former detective named Troop decided that Mrs. Blaine was old and helpless enough to be fair game for them. They moved in on her. Ogelthorpe gained her confidence and persuaded her to leave him a very sizable bequest. Then Elinor Blaine, the grand-daughter, turned up and tried to put a spike in the wheels. Ogelthorpe decided to provide her with a case of paranoia to get rid of her."

"Good God!" Conniston exclaimed. "How did he do it?"

"Drugs and hypnotism and lies and ready-made hallucinations, and I imagine a few other things that were worse."

"Well, damn the rat, he must have succeeded! I mean, the murder of Simpson—"

"No," said Flame. "Look at your reports again. Isn't there any record of an insane woman escaping from an institution recently?"

"No, I told you! Oh, a poison murderess by the name of Bertha Rickson escaped from the State Asylum for the Criminal Insane a month back, but she's a middle-aged woman—"

"Yes," said Flame. "I've found her, too."

"Found her?"

"Yes. She is going now under the name of Bessie Rainey. When she escaped from the asylum, she needed help and needed it badly. If you'll look it up in the medical directory, you'll find that a Doctor Ogelthorpe was a resident physician at the State Asylum for one year. He resigned—by request. I don't know what they caught him doing, but he got out before they could fire him. Bessie Rainey knew something about him, and she came here looking for help. He didn't want anyone reviewing his past history right then. She sensed that, and she played it for all it was worth. She made him give her a job in the house, but that wasn't enough. She tried to move right in on his racket. She helped Elinor escape. She knew that whatever happened Elinor would be so grateful that Bessie would be in clover for the rest of her life."

"Flame!" Conniston yelled into the telephone. "Where is that woman? She's a hell-cat! She poisoned a whole family she was working for! Five of them! Two kids!"

"She's safe," said Flame.

HE watched the knob of the closet door turn very stealthily and slowly. The panels of the door creaked, and the braced chair moved just a little and then held firm. O'Phelan was staring at it with his mouth open.

"Bessie murdered Simpson," Flame said. "He knew who she was. He picked up side-money hiding out fugitives. He interfered when she brought Elinor to his tenement building. Maybe he thought the risk was too great, or maybe he wanted a cut of the money in prospect."

"He got his cut," Conniston said. "Bessie decided then to blame his death on Elinor. She had stolen some of Ogelthorpe's medicine for Elinor. It wasn't medicine at all. It was some derivative of hemp—like hashish or marihuana—that produces sensory hallucinations. She gave it to Elinor and left her unconscious at the tenement while she went to find me. She had me all prepared to come in and find a maniac—Elinor—and a dead man, but Elinor regained consciousness and left before we got there, carrying the razor Bessie had planted on her. Elinor had heard Bessie speak of me, and she came to me. I let her go again." "You—let—her—go!" "Yes. I knew she wasn't insane. She was so full of dope and so keyed up that if I'd tried to stop her by force, she'd have had a complete mental collapse."

"Good God, man! What a chance you took! If you hadn't been right...."

"But I was," said Flame. "Elinor came back to the house here. Troop and Ogelthorpe had caught Bessie and were keeping her prisoner until they could locate Elinor and get things under control again. Elinor freed Bessie, and Bessie killed Mrs. Blaine and again framed Elinor for that murder. Bessie, you see, has the queer twisted cunning of the genuine homicidal maniac. They kill, not just because they're mad, but because their madness gives them an insane justification for killing. Mrs. Blaine had heard enough and seen enough, without realizing it, perhaps, to prove that there was a connection between Doctor Ogelthorpe and Bessie. She was harmless, really. An old, broken woman whose testimony would have meant nothing in a court. But Bessie feared her and hated her, and she knew that if Mrs. Blaine was dead then all the money would be Elinor's, and Bessie had a great deal more influence with Elinor than Doctor Ogelthorpe did because Elinor was grateful to Bessie for hiding her and helping her. Bessie meant to have Elinor's money—all of it—and she came very close to getting it. If Elinor thought she was crazy and a murderess and that Bessie was her only friend...."

"Where is Elinor now?" Conniston demanded.

"Right here beside me. She's unconscious. She was completely exhausted physically and when the dope wore off; she collapsed. I hope she won't remember anything that happened. I don't believe she will. With care, she'll be all right."

"Stay there!" Conniston ordered.

He went on yelling, but Flame couldn't hear him now because Bessie had started to scream senselessly and pound on the closet door. Flame paid no attention. He put the telephone back on its stand and knelt down beside Elinor again.

O'Phelan kept a wary eye on the closet door. "And how did you know that—that she-devil was in there, Doctor?"

"She smeared Elinor's hands with blood," Flame explained, "and she got some of it on her own. There's a little streak just below the door knob. See it?"

"Now I do," said O'Phelan. "Did you—really hypnotize that little one?"

"No," said Flame. "Elinor's mind was an exhausted blank. She couldn't think for herself. Anyone could have taken control of her like I did."

"Not anyone," O'Phelan denied. "Not me. And not that fat fake.... What's the matter with him, Klogatz?"

"He fainted," said Klogatz.

"Fainted, is it?" said O'Phelan. "And what are those red spots on his throat, then? They look like finger-marks to me."

Klogatz said: "There is an ice box in the kitchen down-stairs. A big one."

"Now don't be an ignorant Polish numb-skull," O'Phelan advised him. "All rich people have ice boxes like that."

"This one has beer in it."

"Klogatz!" O'Phelan screamed. "Get out of the way! Take care of yourself or you'll be trampled in the rush!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.