RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

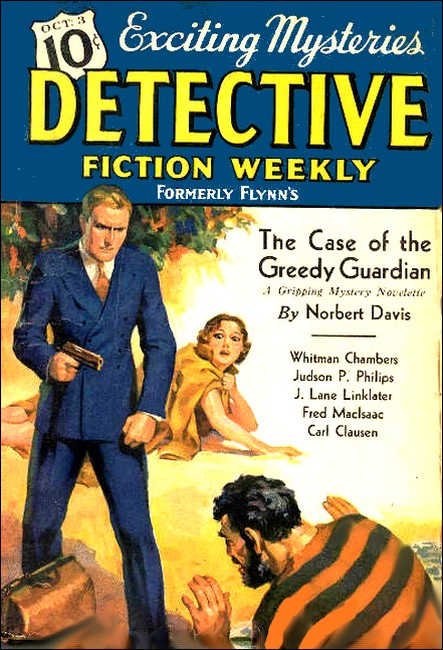

Detective Fiction Weekly, 3 October 1936,

with "The Case of the Greedy Guardian"

"You! Hands up!" the thin old voice rasped.

Slattery turned slowly toward the new menace.

On a lonely, hostile isle deceit and money and

dynamite are the weapons of a scheming madman.

SLATTERY was carrying his trench coat folded over his left arm. He was carrying the bag with the hundred thousand dollars in it in his right hand. He slogged along the narrow path with a sort of weary determination, bent forward a little with the weight of the bag, swearing to himself in a grumbling monotone. Each footstep raised a little puff of dry, sandy dust that hung motionless in the thickly hot, humid air.

The pines were tall, darkly silent on both sides of the path. The underbrush was dry, brownish, artificial-looking. There was no sound anywhere at all, except the thud of Slattery's dragging feet and the slight creaking of the handles on the leather bag. Sweat stung Slattery's eyes, and he stopped to wipe his forehead with the palm of his left hand. Standing there, he looked around him slowly and cursed the woods and each individual tree, plant, and bush in them with a sadly bitter vehemence.

When he ran out of breath, he sighed drearily to himself and walked on again, grunting on each alternate step. He went around a sharply angling turn in the path and stopped short. He was looking right down on the lake. The water was a flat, motionless floor to the brazen ceiling of the sky, so brightly blue that it hurt his eyes.

A dog growled warningly at him. Slattery looked down the bank at the lake's edge below him. The path ended there in a spindling little dock made of dry curling boards which extended out from the shore about ten feet. There was a small boy in blue overalls and a big straw hat sitting on the end of the dock with his feet hanging over the edge. His back was toward Slattery, and he didn't turn around.

The dog was sitting beside him. It was some sort of a cross-bred fox terrier, small and scrawny.

"Hi," said. Slattery.

The small boy didn't move or say anything.

Slattery went slipping and sliding down the bank, stepped cautiously out on the dock. It creaked a little under his weight, then held steady.

"Hi, sonny," he said.

"Keep still," the boy ordered out of the corner of his mouth. He was holding a bamboo pole that was patched here and there along its length with adhesive tape. A linen thread ran from the tip of the pole down to a flat round cork which floated on the surface of the water. He was watching the cork with tense concentration.

Slattery watched it, too, absent-mindedly scratching the fox-terrier behind one floppy ear. The cork bobbed a little, sending out quick widening circle of ripples. The boy's grip tensed on the pole. The cork bobbed again, and then again, and then became motionless. The ripples died.

"Hell," said the boy. He looked over his shoulder at Slattery reproachfully. "You scared him."

"Sorry," Slattery said. "Maybe he'll come back."

THE boy looked him over from head to foot. He saw a tall, thin man with a homely, big-boned face, a long nose that was bent a little to one side at the end, a wide, good-humored mouth, and wide-set grey eyes that had laughter glints deep back in them.

The boy relaxed. "Aw, that's all right. Guess he ain't hungry."

"Maybe not," Slattery agreed. He scratched the terrier under the chin. "Say, know where a guy by the name of Farr lives around this neck of the woods? He's got a place called Three Pines."

The boy nodded. "Sure. Over yonder."

He pointed straight out across the lake toward a blue hazy shimmer of trees and land.

"Which way is the shortest path around the lake?"

The boy moved the pole, dragging the cork carefully around to a new position in the water. "You could walk around this lake forty years, and you'd never get there. It's an island in the middle."

"Oh," said Slattery blankly. "How do you get there? How do visitors get to the place?"

"I don't wanta go there and they don't have no visitors. They don't want 'em. Not even this close. They shot at me the first couple times I fished here."

"Shot at you!" Slattery repeated incredulously. "What did you do?"

"Nothin'. Just sat."

"Oh," said Slattery respectfully. "You just—sat?"

"Sure. I got a right to fish here."

"That's one way of looking at it," Slattery agreed.

"Anyway the guy ain't a very good shot. He's got one of them government rifles, I think, and they're good for this far, only I don't think he knows how to gauge windage. Missed me more than ten feet every time. Scared my dog some."

"Oh," said Slattery. "Scared the dog." He nodded: sympathetically at the terrier, and it sat back on its haunches and grinned approvingly up at him. "Well, I've got to get over there someway or other. How can I do it?"

"Boat," the boy said. He pointed down under the dock.

Slattery leaned over, peered into the dusty shadows. There was a flat-bottomed rowboat tied to one piling.

"Mine," said the boy.

Slattery nodded slowly. "How much to rent it? I might not come back today."

The boy looked Slattery over again, frowning slightly. "Free to you, mister. Leave it here when you get through. I can walk."

"Well, thanks," Slattery said gratefully.

He lay down flat on his stomach on the hot boards, reached around under the dock and untied the boat's painter, hauled the boat out into view. He lowered himself gingerly into it, put the bag of money carefully on the bottom. He sat down, found the oars, pushed away from the dock with one.

"So long."

The boy nodded gravely down at him. "So long."

SLATTERY began to row slowly and evenly. The thole pins creaked and thumped, water swished from the oar blades in dripping semi-circles. The dock and the boy and the dog traveled slowly away from him.

"Hey, mister!" the boy called. Slattery stopped rowing.

"Yeah?"

"Can you swim?"

"I can, but I don't make a practice of it. Why?"

"There's a plug in the bottom. Sometimes it comes out."

Slattery looked down at the whittled pine plug in the bottom of the boat. Water bubbled around it in a thin, moving froth. Slattery sighed lengthily.

"Thanks for telling me," he said.

He rowed on again, swaying back and forth slowly with the movement of the oars. The dock and the boy and the dog grew smaller gradually, a little hazy.

The .45 automatic in Slattery's shoulder holster kept hitting the bicep of his left arm as he pulled on the oars. After a while he got tired of it and stopped for a moment to take the automatic out of its holster and put it down carefully on the seat in front of him. He went on rowing slowly while the shoreline faded into the blue-heat haze. The squeak, thump, swish of the oars made a sort of sleepy cadence.

There was a little blubbering cry. Slattery stopped rowing with a startled jerk, turned around. He was still about a half-mile from the island shoreline. He stared around him blankly and then suddenly found a yellow spot in the blue of the water about twenty yards off to the left.

The blubbering cry was plainer this time.

"Help!" A tanned arm slashed weakly beside the yellow spot, stirred a little white froth in the water.

"Hey!" said Slattery. "Hold it! I'm right with you!"

He swung the boat around clumsily, dug the oars in the water in rapid, jerky strokes, watching over his shoulder. As he came closer, the' yellow spot turned into a short, thickly-tangled mass of gold-colored hair around the tanned oval of a face. Blue eyes stared up at him, widely scared.

"Grab hold, sister!" Slattery said, extending an oar.

The girl caught the blade in a frantic lunge.

Slattery stood up and hauled her in to the side of the boat. Both her hands came up, gripped the gunwale frantically tight. She had nice hands, tanned and small, with slim strong fingers. She was pretty, even now, when her lips were blue and pinched with cold and her teeth chattered, spasmodically.

"You're a long ways out," Slattery said. "What were you trying to do—swim across?"

She nodded, panting in broken gasps. "Yes. Would have made it. Only water's too cold. Got cramp."

"Cramp!" Slattery said. "Where?"

"Both legs."

"Good night!" Slattery exclaimed. "Here. Let me help you in the boat!"

She shook her head, and the water swirled her yellow hair. "No, no!"

Slattery stared blankly. "Huh? Why not?"

"I-I haven't any clothes on."

The water was very clear. Slattery saw now that what she said was quite true.

"Uh!" he said, startled. "Well—are you a nudist or something?"

The blue lips, tightened. "My bathing suit was pulling at my shoulders. I dropped it back about a quarter-mile."

"Oh," said Slattery. "Well, bathing suit or not, you can't stay in that water with cramps in your legs. I've got a trench coat you can wear. Come on!"

"No—"

Slattery got her by the arms just above the elbows, heaved back and up. She came over the side in a slithering rush. The boat rocked precariously, took water over one side, righted itself again. She huddled in the bottom, legs doubled back under her. Her lips were twisted, trembling. Tears made crusted streaks in the wetness of her face. She clawed feebly at the calves of her legs.

"Turn over on your stomach," Slattery ordered. "Go on."

She rolled over. She had long, straight, slimly rounded legs, deeply tanned. The muscles in both-calves were bunched now into a lump the size of Slattery's fist, drawing her small, slim feet up tightly at the heels.

"This'll hurt," Slattery said. He took hold of the calves of her legs, one in each hand, and suddenly dug his fingers into the cramped muscles with all his strength. The girl rolled back and forth in the bottom of the boat, beating at a thwart with her fists, making agonized little moaning noises. The cramped muscles suddenly let loose, relaxed under Slattery's fingers.

"Oh—!" the girl said breathlessly.

Slattery lifted her up, put her on one of the seats. He unfolded the trench coat, wrapped it tightly around her.

"Better?" he asked.

"Oh, yes!"

Slattery sat down again, facing her. "You've got plenty of the old moxie. I've seen lots of big, strong guys howl like Indians over one cramp, let alone two. That's kind of rough treatment I gave you, but it's the best way to fix them quick. You have to loosen the cramped muscle."

"I know. Thank—"

SHE stopped short, staring at Slattery's automatic. Slattery picked it up, put it back in his shoulder holster.

"Don't mind that. I just carry it for ballast."

"I-I never saw such a big automatic."

"It's an Army .45," Slattery said amiably. "I carry it because it makes so much noise when it goes off that it scares the guy I'm shootin' at to death even if I don't hit him, which I usually don't."

He leaned over and opened the bag he was holding between his feet on the bottom of the boat. The hundred thousand dollars was packed flat in it under his clean shirts, and socks. It didn't show. Slattery came up with a round quart bottle of colorless liquid. He pulled out the cork, offered it to her.

"Better have a swig. It'll warm you up."

She took the bottle gingerly. "Thank you."

"Don't smell it before you drink. It's tequila. And go easy. It's pretty strong."

She tipped the bottle up, took one small swallow. She choked, coughing, her face twisting.

"Oh! Horrible!"

Slattery rescued the bottle. "It takes some getting used to, at that. Feel better now?"

"Y-yes, thank you. It does warm you up."

Slattery picked up the oars. "My name's Slattery. What's yours?"

"Gloria Farr."

Slattery stopped the oars in mid-stroke. "Gloria Farr! You old Daddy Farr's niece?"

"Yes."

"Well," said Slattery. "Well, well. I was just on my way to see your uncle."

Her blue eyes were wary suddenly, watchful. "You—you're the man from the Trust Company?"

"Yeah," Slattery said, digging in with the oars. "I better get you back to the island in a hurry. You need a nice hot shower, a couple more drinks, and a rest. You're going to have a pair of sore pins tomorrow."

"Yes," said Gloria Farr. "Yes. I guess—I may as well go back again."

Slattery rowed easily, swaying back and forth, taking deep, even strokes. Gloria Farr had stopped shivering, and her lips had regained some of their normal color. She looked very small, huddled in the folds of the trench coat, but she had a competent, firmly resolute air. She was watching Slattery thoughtfully, and after a while she said:

"Thank you for—all you've done."

"Anybody would have done the same," Slattery said.

He turned to look over his shoulder. They were nearing the island shoreline, and he could see the thin line of white sand at the water's edge. He pulled harder on the oars. They slid up towards the beach. There was a rumbling shout from off to their right. Slattery looked over his shoulder, still rowing. A man was standing on the beach about a hundred yards away. He was a squat, immensely wide outline with spindling bowed legs, long sloping shoulders that hunched forward, loosely dangling arms. His face was a black and white blur.

"Who's that?" Slattery asked.

"Karl," Gloria Farr said. "He's my uncle's servant—cook and house-boy and handy-man."

The thick man yelled incoherently and started plowing through the sand toward them, running clumsily on his short, bowed legs.

"What's eating him?" Slattery inquired.

"I don't know," Gloria Farr answered tightly.

Slattery ran the prow of the boat up on the sand, hopped out and pulled it higher.

"Can you walk all right?" he asked.

She said: "Yes, thank you." She stepped carefully over the seats, out on the beach beside him.

THE thick man arrived in a driving rush, spattering sand ahead of him. He had a short, bristly beard, blue-black, that covered half his face and gave the impression that he had no neck at all, that his small head sat directly on top of his wide shoulders! He had small, colorless eyed, narrowed now into furious gleaming slits.

"You—you—" he said, thickly incoherent.

He swung a ham-like hand and hit Gloria Farr on the side of the face with his palm. The blow made a flat popping-sound, and the force of it whirled Gloria Farr clean around and knocked her sprawling on the sand, on her side.

The thick man raised his foot to kick her, and then stared with bulging eyes. The trench coat had opened when she fell, and she was lying half-naked on the sand. The thick man stared for about a half-second, and then Slattery hit him.

Slattery took his time about it. He took two short steps forward and turned, bringing his whole arm around in a stiff, swishing arc. His fist took the thick man just behind the ear.

The thick man's knees bent a little, and he went off sideways, staggering, waving his arms. He went knees-deep into the water before he could catch his balance, and then he straightened up with a raging bellow and charged Slattery,

Slattery had the .45 automatic in his hand, barrel raised a little. Without hurrying, he used his left hand to jerk the slide back, making a sharp metallic double-click.

"Shoot him," Gloria Farr urged in a small clear voice with a note of hatred in it.

The thick man stopped short, and his colorless little eyes stared widely at the automatic. He was still in the water over his shoe-tops, and now he backed up a step, seeming to be trying desperately to think.

"Come right ahead," Slattery invited very softly.

The thick man made a mumbling noise and backed up another step, still visibly cautious.

"You! Hands up!" Slattery turned slowly to look. The man who had spoken was standing back up the slope of the beach near the edge of the brush. He was a thin, scrawny little man wearing an old-fashioned linen duster that covered him completely from head to foot. He wore an immense white sombrero with a brim that looked to be a foot wide. He was holding a long-barreled bolt-action rifle aimed in Slattery's general direction. In spite of his age he handled the gun capably.

"Hello, Mr. Farr," Slattery said calmly. "I'm Slattery—from the Mountain Trust. You're supposed to be expecting me."

The rifle muzzle jerked up, and then the little man was running down the beach toward them. Under the big sombrero he had a thin, hollow-checked face criss-crossed with a deeply interlaced pattern of wrinkles. He had a voice that was a high, thinly nasal whine.

"Mountain Trust! Why didn't you say so? What—"

"Call off your monkey," Slattery said, "or I'll shoot him and skin him for a trophy."

"Karl!" Daddy Farr barked at the thick man. "What have you been doing?"

Karl grumbled in a sullen monotone, watching Slattery with dully malignant eyes.

"He hit Miss Gloria," Slattery said.

"Oh," said Farr, dismissing it with a shrug. "He was angry at her because I told him to watch her and she ran away. Karl loses his temper easily."

"This time he almost lost something else," Slattery said.

Gloria Farr got up slowly from the sand, wrapping the coat around her. "Thank you, Mr. Slattery." she said. The prints of Karl's fingers stood out whitely on her cheek from his brutal blow,

"You!" said Farr suddenly, staring at her. "Why, you're—you're naked! You haven't any bathing suit on under that coat! Aren't you ashamed? Haven't you any decency, any self-respect?"

She stared at him silently, for a moment. Her blue eyes looked very wide and dark, and there was a pulse hammering visibly in the hollow of her throat. She gathered the coat closer around her, turned around, and almost walked into the man who had come up behind her without making the slightest sound.

He was a young man, below medium height, with a round greasy face that was very darkly tanned. He wore a white suit, a dark shirt. He had a black, glistening mustache over redly-pouting lips that were smiling a little now.

"Gloria, dear," he said in a voice that was a softly-caressing, whisper. "Are you all right?"

He put out his hand toward her, but he didn't quite touch her, because Gloria Farr drew back quickly and Slattery snapped the safety on his automatic. The dark man held his hand there in mid-air and looked sideways at Slattery. Slattery's face was wooden, expressionless, but he moved the automatic a little and the sun glistened dully blue on its barrel. There was a strained and awkward silence.

"Oh," said Farr. "This—this is Gravens, my secretary."

Slattery nodded amiably. Gloria Farr walked carefully around Gravens, on down the beach.

"This is Mr. Slattery, Gravens," Farr said. "The man from the Mountain Trust."

"Ah," said Gravens, and nodded politely.

Daddy Farr came closer to Slattery, tugged at his arm. "Did you bring it—did you?"

"Bring what?" Slattery asked.

Farr's wrinkled face writhed into a terribly eager grin.

"The money, man! The hundred thousand dollars I sent for!"

Slattery looked at Farr, at Gravens, at Karl. They were all watching him with wolfishly tense faces. They moved in a little closer around him.

"Oh," said Slattery vaguely. "The money! No, I didn't bring it. Of course not."

Barr's mouth jerked. "Why not? Eh? Why not? My orders were plain enough, weren't they? I said I wanted a hundred thousand dollars in cash sent up here at once!"

"Sure," said Slattery, "Sure. But a hundred thousand is a lot of money, even to a Trust Company. They're not passing out sums like that unless they know where it's going and how it's going to get there. They sent me ahead to map out the route."

"Oh, the fools!" Farr exclaimed, jerking his thin body from side to side. "The stupid, blundering fools! They know I'm vested with complete discretion as Gloria Farr's uncle and guardian to handle every dime of her money! Why do they quibble? Why do they delay? I tell you time is vital!"

"Why the rush?" Slattery asked.

"There's no mystery about that," Gravens said softly. "Mr. Farr has the chance to buy a very choice piece of timberland up here. Several big lumber companies have been trying to get it for years. But the owner is a queer old character named Coogan who absolutely refused to consider an offer for it. That is, he did until Mr. Farr gained his confidence. The old fellow won't trust banks. He wants the cash—and at once. The timber will be a very excellent investment for Gloria. It's worth three times what Coogan is asking. We wanted to move quickly and secretly before any of the big lumber companies found out the old man is thinking of selling. They'd run up the price if they knew." He hesitated for a second, watching Slattery with wide brown eyes that had an oily sheen to them. "Are you sure you didn't bring the money with you?"

"Why, hell, yes!" Slattery said emphatically. "You don't think anybody would trust me with a hundred thousand dollars, do you? If I ever got my mitts on that much I'd hike for the nearest border!"

"I read a feature article in a newspaper about you once," Gravens said in the same soft voice. "I remembered it, because it said that you were the highest bonded employee of the Mountain Trust. Company. It said you were bonded for a half-million dollars, and because of the type of your duties and the discretion invested in you, the company had to pay about five times the normal amount for your bond. Now a hundred thousand is only a fraction of half a million. The Trust Company wouldn't lose anything if you ran out with it. They'd just collect from the Bonding Company.

"Hah!" said Slattery. "You think so! You should read that bond. It's got more ifs and ands and whereases in it than you ever saw. It covers lots of things, but it sure stops short when it comes to me running around loose in the weeds with a hundred thousand in my pants pocket. It doesn't cover anything like that."

"So?" said Gravens politely.

"Well—well, when can they get it here?" Farr demanded.

"Couple hours after I phone in my report," Slattery said. "They'll fly it up in a plane, probably land in the lake."

"Uh," Farr said petulantly. "Well—well, all right!"

"Shall we go to the house?" Gravens asked quietly.

"Eh?" said Daddy Farr, looking at him blankly. "Well, why? He wants to go back, phone in—"

"I think we'd better go to the house first," Gravens said.

"Oh!" said Farr. "Oh, well—yes. Surely!".

"Mr. Slattery is probably very tired," Gravens said, smiling. "A few hours won't make any great difference."

"I am tired," Slattery said promptly. "In fact, I'm nearly dead. I had to sit up all night on that dinky little putt-putter they claim is a train, and I had to walk seven miles after I got off, and then row myself a couple more."

HE stepped into the boat, picked up the black bag from the floor-boards. The three men on the beach were watching the bag speculatively. Slattery hefted it, changed it over to his left hand, took a firm grip on the handles.

"All right," he said easily. "Lead the way."

"Yes," Daddy Farr said in a thoughtful tone, taking his eyes away from the bag with a distinct effort. "Yes, of course. Would you mind coming this way?"

He started off up the beach the way Gloria Farr had gone. Gravens and Karl waited, watching Slattery.

Slattery jerked his head. "Go ahead."

Farr turned around. "Oh—ah—you wouldn't object if Karl locked up your boat in the boat-house, would you? It's just down the beach around that point."

"Why lock it up?" Slattery asked.

Farr wiggled his thin body inside the linen duster. "Well," he said, embarrassed. "It—it's my niece. You know why I brought her up here?"

"No," Slattery said.

Farr drew a line in the sand with the toe of his shoe.

"Well," he said, "it's an awful thing to have to say about one's brother's child. But—she's absolutely immoral. This business of swimming without the bathing suit was typical of her actions. I have no doubt that she took it off when she saw you rowing near her. I brought her up here because I caught her making love with the man who tended our furnace in the city."

Farr's wrinkled face twisted, and he shook the heavy rifle in front of him. "An ash-man! That was really too much! I've had constant trouble with her before, but I couldn't stand that!"

"It's probably some mental maladjustment," Gravens said silkily. "I think she'll outgrow it. She's still very young, you know, and her parents both died when she was a baby."

"Ummm!" said Slattery thoughtfully.

Farr looked at him sharply. "Did she try to make love to you?"

"Not that I noticed," Slattery said.

"She will," Farr said. "If she gets the chance. I'll try to keep her away from you, but in any event you'll be prepared."

"Yeah," said Slattery.

"You don't mind about the boat?"

Slattery shook his head. "Nope."

"All right. Come this way."

Farr turned around again and started walking. Slattery jerked his head at Gravens, indicating he was to go first. Gravens smiled knowingly, looking from the bag to Slattery's face. He chuckled softly, followed after Farr. Slattery waited for a second, then said to Karl in a flatly metallic voice.

"Listen, dog-face. Don't make any more funny moves in my direction. If you even so much as wiggle your ears at me again, I'm going to start a little Fourth of July celebration all of my own." He raised the automatic meaningly. "Catch on?"

Karl's dull little eyes wavered. "Yes—sir," he said in a thick mumble.

"Remember," said Slattery.

He walked quickly after Farr and Gravens. He had gone about ten yards and was catching up to them when he saw the face watching him from the brush. Only the face was visible, like something disembodied, moving a little as the bony jaws chomped on something that bulged the thin, weathered cheeks. The face had a little goat-like beard and wide, bulging blue eyes. The eyes were centered greedily on the bag Slattery was carrying in his hand.

Slattery stopped short. "Hey!" he said loudly.

The face disappeared instantly. There was no noise, not even the slightest movement of the brush where it had been. It was just not there any more.

Slattery swallowed hard, staring. Gravens and Farr had stopped at his shout, were locking back at him.

"What is it?" Farr called.

"I just saw somebody in the brush," Slattery said.

Gravens shook his head, a little pityingly. "You couldn't have, Mr. Slattery. There's no one on the island but Mr. Farr, myself, you, Karl and Gloria. It's very small. Perhaps the sun. It's very glaring here near the water..."

"Yeah," said Slattery. "Lead on."

THE house was back, hidden in the trees. It looked like a motion picture set representing a hunting lodge. It was long and low and rambling, built of halved logs with the bark still on them. The dark shadows of the pines were thick and gloomy around it, and the lake breeze rustled the brush in sly, dry whisperings.

Daddy Farr and Gravens went up the two steps to the low porch and waited there for Slattery to join them.

"Would you like a little something to eat?" Gravens asked silkily.

Slattery nodded. "Yeah, I'm hungry as hell:"

Gravens smiled. "All right. Karl is our cook. He'll fix something up for you as soon as he comes."

"Karl, huh?" said Slattery thoughtfully. "I guess maybe I'm not so hungry, after all. I'd like to take a little nap instead. Is there any place I can lie down?"

"Certainly," said Farr. "Show him, Gravens."

"This way," Gravens said.

Slattery followed him through the wide doorway. It was an immense living-room, higher inside than the house looked to be, with a balcony running clear around it. There was a big natural stone fireplace on the far side with a pile of neatly-quartered logs beside it. Gravens and Slattery went single file up a flight of stairs, part way around the balcony. Gravens went through an open door, down a short, dark-hall with Navajo rugs on the floor that were streaked jaggedly white and red. He opened a door at the end of the hall.

"This bedroom is ready. You won't be disturbed here. There's no one else in this wing."

Slattery went into a room that had a low-beamed ceiling, unfinished pine furniture that was low and comfortable-looking. There was a wide bed on one side, under the small window set aslant in the sloping wall

"The bathroom is next door," Gravens said. "Would you like anything else? Can I get you a drink?"

"No, thanks," Slattery said.

"Then good by—for a while," Gravens said softly. He backed out of the room, closed the door behind him noiselessly.

Slattery waited, listening to the creak of his footsteps going down the hall. He was still holding the bag with the money in it tightly in his left hand. After a moment he walked over to the door, looked at it carefully. The door had a lock, but there was no key in it.

"Huh!" Slattery said absently to himself.

He went back and sat down on the bed, sinking into its softness with a long, relieved sigh. He opened the bag, took out his bottle of tequila, and took a big swallow of it. He choked, shuddering, gasping for breath. When he had recovered himself, he took another swig and went through the same procedure over again. He corked the bottle, put it back in the bag, closed it and snapped the catches. He put the bag carefully between his feet on the floor.

He found a limp cotton sack of tobacco and a package of brown papers in his coat pocket and started to roll himself a cigarette with casual ease. He raised the cigarette to lick the flap shut and stopped with his mouth open, watching the door.

The knob was turning very slowly and silently. Slattery slowly lowered the cigarette, holding it in his left hand. He reached inside his coat with his right, brought out the .45 automatic. He balanced it carefully in his hand.

The knob clicked, and then suddenly the door flipped open and Gloria Farr slipped inside the room, shut the door quickly behind her. She leaned against it, breathing hard, watching him with widely blue eyes.

SLATTERY swallowed noisily and lowered the automatic. "Better knock next time," he said slowly. "I damned near shot through the door. I'm getting a little jumpy."

"I'm—sorry," she said in a low voice. "I didn't want to make any noise. I didn't want my uncle to know I was here. He forbade me to see you."

"Oh," said Slattery aimlessly. "I see."

Her face seemed to grow darker and smaller, and her mouth was a thin red line. "Did he tell you any thing about me?"

"Well," Slattery said uneasily. "In a way—yes."

"I know. He told you about me being immoral. Didn't he?"

"Yup," Slattery admitted.

"Do you believe that?"

"Hell, no," said Slattery, grinning at her.

She relaxed. "I'm sorry. I should have known you wouldn't. You—you're a pretty, decent sort, aren't you?"

"Well," said Slattery. "There's some argument about that. You could find people who wouldn't agree with you at all. But I just figured your uncle was sort of a nut on the subject, and I didn't pay much attention to him."

"A nut!" she repeated thinly. "That's putting it—kindly! You know how he's played up in the newspapers. 'Daddy' Farr! The kind, rich old gentleman who loves little children. Who is always giving dinners for orphans and news-boys and crippled children. That's the side the public sees and hears. But I never do! All I see is a nasty snarling, hateful little mind! He hates me. He hated my mother—tried to keep my father from marrying her. It's been a hell for me ever since I was old enough to understand. Everything I say he twists around to give another meaning. He watches me constantly, peeping, prying, spying. Sometimes I think I can't stand it—even for another year. I'll come of age then, and I'll be free of him. But—but it seems sometimes like I can't last it out. Like this morning when I tried to run away—swim the lake..."

"Uh-huh," Slattery said sympathetically.

"He brought me up here to keep me away from everyone. He never would let me go out with young people. Here Karl watches me all the time."

"He isn't what I'd call a high-class guardian for a girl," Slattery observed slowly. "Not the way he acted this morning."

"That isn't the first time he's hit me," she said.

"No?" said Slattery, frowning. "Well, maybe I better have another little session with him."

"He—he's terribly strong."

"Uh-huh. But I'm awful tough. Where does the greasy gravy gent come in?"

"Gravens? My uncle wants me to marry him." Her face twisted suddenly into a disgusted grimace. "He's what my uncle considers an upstanding young man."

"Well, either your uncle's wrong, or I am," Slattery said.

She hesitated, listening. "I've got to go now. I—I just wanted to talk to you. If I stay longer they'll miss me and if they find me here they'll—they'll say—"

"Not to me, they won't," Slattery said grimly.

"Thank you. Good-by." She opened the door, slipped quietly through it into the hall. She closed the door noiselessly. Slattery sat motionless on the bed, scowling thoughtfully. He licked his cigarette, twisted the ends, lit it. He smoked it clown to a short stub, still scowling, then got up and ground out the butt in a copper bowl on the dresser. He took a straight-backed chair from one corner, braced it carefully under the door-knob. Going back to the bed, he threw the pillow on the floor, replaced it with the black bag. He lay down on his back on the bed, resting his head on the bag. He put the .45 on his chest and folded both hands over it. He went to sleep in about five minutes...

SLATTERY woke up all at once and sat up straight in bed with a startled jerk. The .45 automatic slid off his chest, thudded heavily on the floor beside the bed. Slattery rolled over and grabbed it blindly, and then sat up again, blinking around him. It was dark in the room.

"Good gosh!" Slattery mumbled, digging at his eyes with the knuckles of his left hand. "I can't have slept this long—"

He fumbled the cheap watch out of his pocket, stared incredulously at the luminous dial. He had slept this long. It was after eight o'clock.

Slattery slung his feet over the edge of the bed, pushed himself forward. The shot came then. It sounded as though it were right below him. Right after it there was a thump that shook the walls a little, and then a dragging clatter of sound.

Daddy Farr's high, whining voice screamed: "Gravens! Gravens! What—" His feet made noise pounding across the living-room, and then his voice shrieked on a frantically hysterical note "Murder! Murder! Help—"

Slattery jumped off the bed, slammed across the room. He kicked the chair out of the way, jerked the door open. The hall was empty, dark, but there was light coming from the door to the left that opened out on the balcony around the living-room.

Slattery ran that way, burst out on the balcony, and stared down into the living-room. Reading lamps threw deeply greenish pools of light over the two soft leather chairs on either side of the big stone fireplace. But there was no one in the room.

Daddy Farr was screaming again. "Murder! Help! Karl!"

Slattery ran around the balcony, down the stairs. He slipped on the soft rug at the bottom, righted himself, and ran to the big front door. It was wide open and so was the screen door that backed it. Slattery went out on the front porch.

There was a light on the porch, at the front, over the two shallow steps that led up from the path below. Oh the path, just inside the circle of light, there was a figure sprawled flat on its face on the ground. The figure wore Daddy Farr's old-fashioned linen duster and Daddy Farr's big white sombrero. But it was not Daddy Farr lying there, because Daddy Farr was sitting on his heels beside the sprawling figure, rocking back and forth and screeching insanely.

Slattery jumped down the steps, ran forward. "Here! What's this? What—"

Farr stopped his screaming and stared at him with eyes that bulged widely out of the wrinkled smear of his features. "It's Gravens! Somebody shot him! Shot him!"

Slattery knelt down beside the sprawling figure, gently turned it over on its back. The round, darkly greasy face of Gravens stared up at him. Gravens' thickly pouting lips were open slackly, and his brown eyes were very wide, very glassy, and quite dead.

There was a little black hole squarely between the eyes, and blood that looked black and thick had slid down over one cheek in a lacy, criss-crossed pattern.

"What happened?" Slattery asked softly.

Farr glared wildly at him. "They meant to shoot me! You see? He's wearing the hat and coat I always wear. In the dark they thought it was me, and they shot him!"

"What happened?" Slattery repeated.

Farr swallowed hard. "We—were reading there by the fireplace. I-I asked him if he would go down and take a look at the boat-house to make sure that Karl locked it like I told him to. So he got up and said it was a little cool down by the lake and he thought he'd get his coat and hat. So I told him to take mine. He put them on and went out the door. And there was a shot, and I heard him stagger down the steps and fall. I ran out here."

Slattery carefully worked the big white hat off Gravens' head. He held the hat up into the light. The bullet had not penetrated. Slattery lowered the head again, looked curiously at the hat. His eyes narrowed suddenly. He looked at where his fingers were holding the hat on the brim and then looked down at Gravens.

"Huh!" he said absently. He put the hat down on Gravens' dead face and stood up.

"I tell you they thought it was me!" Farr said hysterically. "Somebody heard about that money you were supposed to bring, and they were waiting—"

Slattery stiffened. "Money!" he choked.

He whirled around and jumped back up on the porch, slammed through the front door.

"Don't go!" Farr shrieked. "Don't leave me—"

SLATTERY was going up the stairs to the balcony three at a time. He hit the top, whirled abound the balcony, in through the door that opened on the short hall. He ran down the hall, skidding on the rugs, kicked the door of his bedroom open wide.

There wasn't much light in the room, and the shadows seemed to move slowly with the rustle of the pine trees outside. But there was enough light for Slattery to see that the bag with the hundred thousand dollars in it wasn't on his bed any longer.

Slattery grunted breathlessly. "That does it!" he said thickly.

The small window over the bed was open, the curtain moving a little in the night breeze from the lake. Slattery got to the bed in two long jumps, landed in the middle of it on his hands and knees. The screen on the window was slit parallel with the base and ripped loose along the bottom.

Slattery pushed it back, peered down at the ground. There was another window on the ground floor directly below his, and a little light came palely through it. Just enough light to show a weathered goat-bearded face peering up at him with its thin jaws chomping busily on something. Just enough light to reflect slickly black from the smooth sides of the leather bag.

"Stop!" Slattery yelled breathlessly.

The bag and the face jerked out of the light in that uncannily silent way. Slattery fired down into the shadows where it had disappeared three times. The big gun smashed hard against the heel of his hand. The reports hammered in a confused roar of sound. The glass in the window rattled a little.

Slattery crawled right straight through the window. It was too narrow to turn around in, and he dropped head first toward the ground as soon as his legs cleared the sill. He managed to turn partly around in the air and came down hard on his left side with a jar that numbed his whole body.

He staggered dizzily to his feet, fighting to get a breath. He was out of the yellow swath of light that came from the window now, and it was as though a thick black blanket had been clapped tightly over his eyes. All around him branches rustled in sly, quiet murmurings.

Slattery plunged into the brush, heading diagonally away from the house. He threshed his way straight ahead for about twenty yards. Branches flicked across his face like sharp cutting little whips, dragged at his legs. He tripped over a hidden log and fell flat on his face. Dust from the thick carpet of pine needles choked him, and he seized his throat with his left hand to keep from coughing.

He got up to his knees and stayed there for a moment, listening. There was noise far off to his left. Brush crackled faintly. Slattery got up and ran blindly that way, protecting his eyes by holding his left arm in front of his face. He bumped into trees invisible in the darkness, stumbled over hidden obstacles, but he kept his head down, kept his legs moving, kept on driving stubbornly ahead through the darkness.

He was getting closer to the noise. He could hear it even above the sound of his own progress. There was the heavy thud of shuffling feet now. But the feet didn't seem to move. They stayed right in the same place, and as Slattery slowed a little, trying to stare through the brush, he could hear the sound of breathing—heavy, labored breathing. And then the flat plopping noise of bare fists hitting flesh.

Slattery kicked through another clump of brush and then stopped short, widening his eyes in incredulous, unbelieving amazement.

It was a little clearing in the woods covered over with an ankle-high carpet of dry brush. There was a moon now, fat and red on the horizon, and its ghostly thin light showed the two men fighting in the middle of the clearing.

They fought silently, viciously, savagely, without any words or any pauses. They were slugging at close quarters in a sort of blind frenzy.

One of the men was Karl. Slattery recognized the wide sloping shoulders, the long ape-like arms, the spindling bowed legs. The other man was taller, straighter, but with shoulders just as wide. This second man wore no clothes except for a tight pair of shorts that were the same color as his tanned body.

Slattery gaped in dazed wonder. The tall man was driving Karl straight back across the clearing, pounding one chopping blow after another into the bearded face. Karl tried to guard, tried to hit back, but he was clumsily helpless against the other man's lithe quickness, his savage determination. They were at the edge of the clearing now, and the shadows there seemed to reach for them hungrily.

Karl stumbled a little. He was facing Slattery, and Slattery could see the bruised raw mass of his face over the black beard, see the dull little eyes bulging in strangled terror. He managed to duck under one of the tall man's blows, suddenly dove forward, arms outstretched.

The arms clasped tight around the tall man's waist, and Slattery saw Karl's thick fingers lock together behind the bare, smoothly muscled back.

Karl made a thickly grunting noise of triumph. His arms seemed to swell like thick snakes as he squeezed the tall man against him.

SLATTERY started forward and then stopped again. The tall man's long body seemed suddenly to be a sharply etched outline of corded muscle. He had bent backwards under Karl's sudden lunge, but now he began to straighten up. The muscle writhed and bunched across his wide shoulders, along his back. He had his hands gripped behind Karl's back in just the same back-breaking hold that Karl had on him. And now under the tremendous pressure of Karl's thick arms, he began to arch his back.

Karl's breath whistled in his throat. His eyes were like bulging red-veined marbles. His mouth was wide open in the black bristle of his face. He was bending slowly over backwards. He screamed suddenly—a thin, mewling note of horror. He let go of the tall man, tried to squirm free.

The tall man dropped him suddenly. Karl staggered backwards, and in that second the tall man caught him. He picked up Karl's thick body clear up off the ground, whirled and bent over. Karl went sailing through the air back toward Slattery like some monstrous, flapping bird. He hit the ground on his head, and there was a dully muffled crack. The tall man staggered a little, catching his balance, and then walked towards him. He didn't even see Slattery. He bent over Karl, turned him over roughly.

"Nice work," Slattery said. "He needed—"

He didn't get a chance to say anything more. The tall man reached him in two incredibly quick jumps, flung his doubled fist forward in a looping right. The fist was a white-knuckled smear in front of Slattery's eyes. He ducked instinctively, got down far enough to take the blow on his forehead.

It felt like the whole world had suddenly flipped over and dropped on his head. He tripped and went sprawling backwards in a dim, red-shot haze that flickered crazily in front of him. He had only time to feel the jar as his shoulders hit the ground, and then the tall man dropped on his chest with both knees and long, thick fingers gripped his throat and clamped down like a living vise. Slattery's eyes popped under the pressure.

He writhed back and forth on the ground, managed to jerk his right arm free of the tall man's crushing weight. He jammed the muzzle of the .45 hard into the tall man's bare, muscled stomach. His thumb found the safety lever on the gun, pushed it off with a sharply metallic click.

The tall man froze, kneeling on top of him. Slattery pushed harder with the automatic. The tall man's thick fingers loosened slowly on his throat.

Slattery coughed painfully. "All right—Tarzan," he said in a thick mumble. "Back off, or I'll blow you down!"

The tall man got up off him very slowly. "Oh! I—I thought you were Gravens."

Slattery sat up, still keeping the automatic leveled, and rubbed his throat gingerly with his left hand. "I'm not—I'm happy to say Gravens is lying back by the lodge, deader than a pickled herring."

"Dead?" the tall man exclaimed incredulously.

"Uh-huh. Shot right through the bean."

"Who—who shot him?"

"I don't know," Slattery said. "But now that we're on the subject, just who the hell are you and what're you doing running around here half-naked?"

"My name is Burks—Tod Burks. I swam across from the mainland to see Gloria."

"Huh!" said Slattery, amazed. "Why?"

"Because I love her!" Burks said angrily. "They brought her up here to get her away from me! They didn't think I'd have money enough to follow her, but I sold all my books and instruments and pawned half my clothes, and I came!"

"Well, I'll be damned," said Slattery faintly.

"I'm camping across the lake in a pup-tent I borrowed from my roommate. I swim across every night and wait for her to duck out of the house. She couldn't get out tonight. They had her locked in, but I climbed up to her window and talked to her a while. She told me Karl had hit her, and I hunted him up. I told him before what I was going to do to him if he ever laid a hand on her again. I meant just what I said."

"I guess you did," Slattery said soberly. "I heard something pop when you dumped him, and I think it was his neck."

Burks whirled around to stare at Karl's thick, motionless body. "Neck! You mean—?"

Slattery pushed himself up off the ground, grunting with the effort, and walked over to Karl. He leaned over the lumpy, inert body.

"Yeah," he said slowly. "It was his neck. He's dead."

"Dead!" said Burks. "But I didn't mean..."

Slattery nodded. "I know. It was self-defense. I can swear to that. He was sure tryin' his best to break your back when I came on the scene. He would have if he could. I'd sure have hated to have him get hold of me like he had you. You carry around a lot of power, boy."

Burks was staring down at Karl with a sick, nauseated expression on his tanned face. "You get that shoveling coal," he said absently.

Slattery looked up. "Shoveling coal?"

Burks nodded "Yes. I'm an engineering student. I've been working my way through school tending people's furnaces. That's how I met Gloria. I was taking care of their furnace—"

"You're the ash-man!" Slattery said.

Burks nodded again. "That's what Farr called me. He said I was after Gloria's money! As if I'd—"

"Money!" Slattery said, gasping. "Good gosh! I forgot it again! Listen, did you see a little goat-bearded gent with a black bag running around here?"

Burks stared at him. "What?"

Slattery made an impatient gesture. "I know it sounds screwy! I can't help that. There is such a guy carrying such a bag. And the bag is full of Gloria Farr's money. I figured he'd head for the boat-house. Come on."

He plunged into the brush again with Burks trotting lightly after him. He slid down the bank of a steep little gully, crashed through the brush along its bottom, came but suddenly on the beach. He stopped short, looking both ways.

About a hundred yards to their right there was a low flat structure a few feet up from the water's edge.

"That'll be it," Slattery said.

He plowed heavily through the deep sand. Burks ran easily and lightly beside him. The moon, higher up now, threw grotesquely jiggling black shadows ahead of them, and the water of the lake was a cold, still-gleaming green.

Ten yards from the boat-house, Slattery dug his heels in the sand and stopped short. One of the wide doors was open, sagging drunkenly on a broken hinge.

"He got here first," Slattery said tightly.

He walked slowly up to the door, the big automatic held hip-high in front of him. The interior of the boat-house was a thick square of blackness. Slattery peered vainly past the door, trying to pierce the gloom. He fumbled a match out of his pocket.

"I don't know how many boats there are—"

He snapped the match on his thumb nail, held the spurting yellow flame over his head. It wavered suddenly in his fingers, then steadied again.

Burks looked in over his shoulder, said at last, in a sick voice, "He's dead?"

The little man with the goat beard was dead. He was lying on the half-board floor with his head propped up against the side of the boat. The boat was painted white, and the little man's head, lolling against it, had left a great bloody smear. A heavy bloody hammer lay beside the body.

The little man lay there, looking unwinkingly back at the light. He looked very small and in some way pathetically childish in spite of the wrinkled, weathered cheeks and the little beard.

Slattery didn't have to answer Burks' question.

The black bag was turned upside down, on the ground beside him, and Slattery's shirts and socks were scattered helter-skelter over the sand-drifted boards. Slattery could see into the bag from where he stood. It was quite empty. And there was no money visible anywhere on the floor.

"Why!" Burks said suddenly, peering more intently. "That's old Coogan!"

The match burned Slattery's fingers, and he flicked it away from him. "What? Do you know him?"

"I know of him," Burks explained slowly. "Everybody does around here. He's a character, an old trapper, a little touched in the head. Claims to own all this country through here because he used to trap over it years ago. Of course, he doesn't."

"Coogan," Slattery muttered to himself. "Coogan. Where have I heard—hey! That's the guy Farr was going to buy some timberland from!"

Burks stared at him incredulously. "Why—why, he doesn't own any land! Everybody knows that! This land all around here belongs to the government."

"Well, what the hell?" Slattery queried in a puzzled tone. He stiffened suddenly. "Say! I'm going back to the lodge and talk to Farr. I've got a lot of questions I want that old boy to answer!"

"I'll go with you," Burks said quietly.

They started back up the beach. About twenty yards from the boat-house, Slattery kicked a short yellow stick out of the sand. He leaned over curiously and picked it up.

"What's this?" he asked, holding it to the other man.

"It's dynamite," Burks answered calmly.

Slattery made a startled, choking noise and held the stick at arm's length away from him. "What—what—?"

Burks reached for it, looked at it closely. "It's a half-stick. See where it's been cut?" He took the stick in both hands and twisted it.

"Hey!" Slattery said, alarmed. "Watch out!"

"There's no danger," Burks replied absently. He kicked around in the sand, uncovered several more short sticks.

"Good gosh!" Slattery exclaimed, backing up rapidly.

Burks was examining a couple of the other sticks. "They've been cooked. See how soggy they are?"

"Cooked!" Slattery repeated. "You don't mean somebody eats—"

"No, no! Dynamite is made of nitro-glycerine. That's the explosive in it. It's a liquid in its pure form. It's diluted in dynamite. Someone cooked this to get the concentrated explosive. It's a dangerous thing to do."

"I should think maybe," Slattery agreed. "Say, I'm beginning to see. Coogan, the dynamite, Gravens, the money—"

"Tod! Tod!"

GLORIA FARR came running down the beach toward them. She was wearing blue silk pajamas, a blue bath-robe pulled tightly around her waist. She was barefooted. Burks ran to meet her, swung her up easily in his arms. "Gloria, dear!"

She was panting heavily, sobbing a little in breathless gasps. "I—broke down the door with a chair. I couldn't stay there alone any longer. I heard the shot and uncle screaming. And when I got out I found Gravens lying there, dead. What—what is it? What's been happening? What's been happening?"

"Plenty," Slattery answered grimly. "I'm beginning to get the answers now. You see, the Mountain Trust thought it was funny your uncle wanted all that dough sent clear up here in secret and in a hurry. Farr was given complete control of it in your father's will, but we looked into it anyway. We found out the old man has made a lot of screwy investments with his own money. He's been losin' right and left, and right now he hasn't hardly a dime of his own to jingle in his pants.

"Well, I think he decided to begin on your dough. First, he got the idea of marrying you to Gravens, but that didn't work out so well, so he got a new idea."

Burks said uncertainly, "You mean?"

Slattery shrugged. "I don't know, of course, but I'm guessing that he meant to knock Coogan on the head and then use the nitro to blow up the house with him in it. You couldn't identify the body if it was blown to pieces and the house burned over it. It would be assumed that Farr was the guy that got it—if he disappeared. Everybody would think the dough was stolen or blown up with him. About Gravens—I'm guessing again—but I think he was in the way. Farr didn't care to split with him. So he shoots him and tries to make it look like somebody is gunning for Farr and got Gravens by mistake. That's really what tipped me off. Gravens was supposed to be shot because he was wearing Farr's hat and coat. But the hat was on backwards."

"What?" Burks said blankly.

"I took Farr's hat off Gravens. It was on backwards. A man putting on a strange hat invariably looks inside to see which is the front and which is the back. You see, Farr meant to take the dough and skip. Coogan would disappear at the same time, and if there was any blame passed around, everybody would think the poor old screw-loose did it all. Nobody would be looking for Farr. As I said, that's just guessing, but I'll bet I'm pretty close."

"You are," said Daddy Farr. "You're pretty close."

He was standing just in front of the boat-house. The shadow cut him off at the waist and made it look like there was just half a body suspended there motionless in the air. His wrinkled face was twisted into a terribly fixed, malignant grin. He had a quart bottle in his right hand, raised back over his shoulder. The bottle was partially filled with sluggishly gleaming liquid.

"The nitro-glycerine!" Burks said in a numb whisper.

"Oh, yes!" Daddy Farr, said, and he laughed on a high, whinnying note. "You were perfectly correct, my dear Slattery!" He brought his arm down in a smooth arc, hurled the bottle of explosive straight at the three of them.

Slattery jerked his automatic up to try a snap-shot at the bottle, knowing even as he moved that there was no possible chance of him hitting it. But before he could raise the muzzle, there was a thin whip-like crack. The whole world seemed to split wide open in one thundering blast of sound that shook the ground under their feet. A great hand slapped Slattery all along the length of his body, pushed him through the air. He was slammed back onto the sand, and a crazy circle of red flares seemed to chase around and around inside his head.

His chest was pushed flat against the ground, and he choked and coughed, trying to get air into his lungs. Faintly through the booming in his ears, he could hear Tod Burks saying anxiously:

"Gloria! Gloria! Are you all right?"

Her voice said "Y-yes."

"Hello, mister," another thin voice called.

SLATTERY forced his numb muscles to respond, slowly pushed himself into a sitting position. A figure materialized out of the red glare that blinded him. It was the boy he had met fishing on the pier that morning. He was standing over Slattery, staring down at him soberly. He was carrying a short-barreled .22 rifle in the crook of his arm.

Slattery gasped unbelievingly, "You—you—"

The boy nodded gravely. "I was watchin'. I shot the bottle before it left his hand. I didn't know it would blow up!"

Slattery looked around. Tod Burks was kneeling beside Gloria Farr, helping her to sit up. Slattery looked at the place where Daddy Farr had stood. There was a shallow, wide hole blasted in the sand. The boat-house was flattened right down to the beach, as though some gigantic heel had stamped down on it, ground it into splinters. Slattery shivered a little and looked quickly away.

"How—how did you get here?" he asked blankly.

"With my uncle—Nick Coogan," the boy said. "And he's not crazy either! He's—he's just a little funny because he stayed alone so much when he was trappin'."

"Sure," Slattery said gently.

"Farr killed him," the boy said, swallowing hard. "I heard Uncle Nick yell, but I was too far away to help, so I waited in the brush for Mr. Farr to come out of the boat-house. Uncle Nick was pretty good to me! He—" He sobbed suddenly, a dryly harsh, gasping sound that he tried to choke down in his throat.

Slattery got up unsteadily, put his arm around the boy's shoulders. "You did just right! Believe me, you did! Come on, let's get away from here."

"There's no boats," the boy said. "They're all smashed to pieces. Mine was tied behind the boat-house. The explosion has sunk it. The one I lent you was inside the boat-house. Uncle Nick broke in to get it."

"I'll swim back," Tod Burks said. "I'll send somebody over to pick you up."

"I'm going with you!" said Gloria Farr.

"All right," Burks said, smiling at her. "I'll tow you."

She fumbled at the cord on her bathrobe. "Will you look the other way for a moment, Mr. Slattery? I still haven't got—"

"Well, here now," Slattery objected uncomfortably. "Maybe you shouldn't."

Gloria Farr laughed a little unsteadily. "Don't worry, Mr. Slattery. Tod and I have been married for four months. We didn't tell my uncle because he would have had the marriage annulled."

"Oh," said Slattery blankly. He turned his back.

There was a little pause, and then a quick double splash in the water.

"Good-by," Gloria Farr called.

Slattery turned to look. Their heads were shadowed blobs on the smoothness of the water, close together. As he watched, Burks struck out effortlessly, in a slow slashing crawl. Gloria Farr's head bobbed along evenly beside him.

"Well," sighed Slattery, looking uneasily at the scooped-out hole in the sand. "I guess I'll have to poke around and see if I can't find a few shredded bills to take back with me."

"Bills?" said the boy. "You mean the money? I've got all that."

Slattery whirled to look at him. "What did you say?"

"I took the money out of the bag. I made Uncle Nick open it up and show me what was In it. Uncle Nick didn't want the money. He just wanted the bag. He's always wanted one like that—made of nice shiny leather."

"Good night!" Slattery groaned faintly.

"I knew he stole it," the boy explained uncomfortably. "But—but he cried when I took it away from him. He wanted it so bad. I—I was going to pay you for it, mister. I would have taken your other things out only I didn't have any way to carry them."

"Well," said Slattery, "Well, well!"

There was a plaintive whine from behind them. Slattery jerked around, startled.

"It's Muggsy—my dog," the boy said. "The explosion scared him pretty bad. Here, boy."

THE little fox-terrier crept along the sand toward them, cringing low, whining a little. He recognized Slattery suddenly and came forward in a spattering shower of sand and hopped up and down against the boy's leg, making glad yapping sounds.

"Well," said Slattery numbly. "I guess—I'll go to the house and try to find a drink."

"I took a bottle out of your bag," the boy said. "I hid it with the money. It had a funny label on it, and I didn't think it would be good for Uncle Nick to drink it."

Slattery drew a deep, incredulous breath. "My friend," he said, "you are—you are—something!" He reached for the lad's hand, shook it gravely. "Lead on!"

They went down the beach together—a long shadow and a short shadow, with the fox terrier a humped little blur tagging at their heels.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.