RGL e-Book Cover

(Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

(Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software)

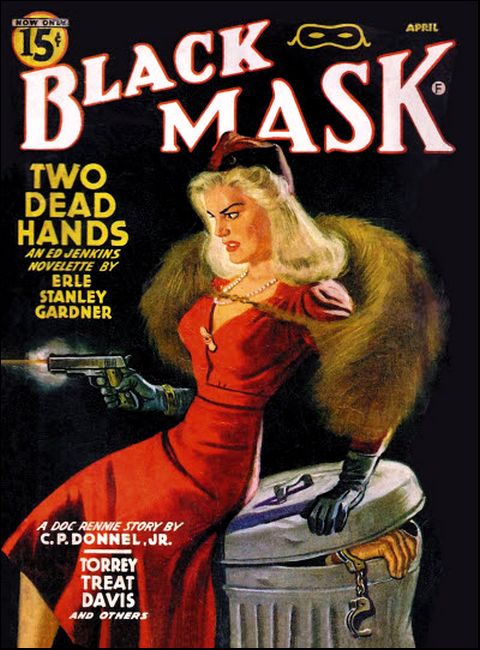

Black Mask, April 1942, with "Walk Across My Grave"

IT is necessary to understand at the start that Mrs. Frelich was a good woman. The phrase is meant to be taken just as it stands: without quotation marks, without any ironic emphasis.

She awoke when the wind changed direction and blew sharp and cold through the bedroom window. She squirmed under the covers and muttered in vague protest, but the wind riffled the stiff lace curtains, rattled the window shade, and then came and put a chill ghostly finger on the tip of Mrs. Frelich's nose. "Oh, drat," she said drowsily. She flipped the covers back and got up, tubbily shapeless in her thick gray flannel nightgown, and padded over to the window. Her eyes were sticky with sleep, and she probably would never have seen the figure outside at all if it hadn't been moving so erratically.

As it was, she stood rigidly with her arms raised and her fingers hooked over the bottom of the window sash. She stared, and all her sleepiness was whisked away in an instant.

The moon was wan and thin among hurrying storm clouds, and the iron picket fence that enclosed Oak Knoll Cemetery made a neat geometric shadow, black against the dingy gray of the half-melted snow drift that clung to its base. Behind the fence the tombstones stood in ragged ranks, fat and short and tall and spindly, as still as the death that was under them.

The black figure was running between the tombstones. Not running anywhere in particular and not running very fast. Weaving back and forth, spinning and dodging and swerving with a crazy fluid grace.

Mrs. Frelich's voice came cracked and thick out of her throat. "Abe! Abe!"

Bedsprings squeaked in her son's room.

"Huh? What?"

"Abe!"

He bumped against the door. "Huh? What's the matter, Mom?"

"Look! The cemetery! Somebody—something—"

Abe stood beside her at the window, breathing noisily. The black figure below hit the iron picket fence and bounced away, whirling gracefully to keep its slack-kneed balance, but it tripped over a low headstone and went flat and squirming in a pile of snow.

Abe Frelich drew his breath in a gasp. "It's Dave! It's Dave Carson. He's drunk, that's what! He's drunk, and he thinks he's playin' football!"

"You go get him," said Mrs. Frelich. "Make him stop. It's terrible he should be doing that in there."

The black figure was up and staggering.

"Oh, no!" said Abe. "I ain't gonna fool with him! Not Dave Carson! Not the banker's son! Oh, no!"

Mrs. Frelich clutched tight at a curtain and crumpled it. "Look. He ran right into the Raymonds' stone. He's got to be made to stop."

"I'll call Tut Beans at the jail," said Abe. "It's more his job than mine. Let him get old Carl Carson sore."

JIM LAURY had run for sheriff of Fort County because he

wanted the job. It paid pretty well, and he knew he wouldn't

have to work very hard at it. Besides that, he really

enjoyed dealing with law-breakers, and he knew that the most

interesting ones weren't to be found among the regimented

masses who huddle uncomfortably together in cities but in

the small towns and the open country around them where

individuality is still more than a myth.

He was tall and sleepy-looking and he talked in a slow drawl. He never moved fast unless he had to. He was wearing his long brown overcoat when he entered the funeral parlor through the side door, and he unbuttoned the collar and turned it down, wrinkling his nose distastefully at the heavy lingering odor of wilted flowers that clung to the anteroom.

Ferd Runyon tiptoed through the curtained doorway and nodded at him eagerly. "Do you wanta see Rita, Jim?" Ferd had a nervous giggle that he had labored years to control. It rated as quite a serious handicap in his business. It popped out now, unexpectedly, and Ferd clapped his hand over his mouth. "'Scuse me," he said with the ease of long practice. "My dyspepsia.... The remains are in here, Jim."

Laury followed him in to the back room and watched while he folded back the top of the long white sheet.

"I ain't fixed her yet," Ferd said.

She was a pretty girl. Her face was a clear oval, white and waxy, and death hadn't disturbed the childlike composure of her features.

"It's the back of her head," said Ferd. "It's smashed like an egg. Do you wanta see?"

"No," said Laury. He stood still, his shoulders hunched, staring down.

"I'm kind of bothered-like," Ferd said slowly. "You see, it's the second tragedy in the Blenning family within a month, although you really couldn't call their Uncle Mort's passing a tragedy because the old boy was sure a pest and a burden to 'em.... But the Blennings had to pay for his funeral, him not having a dime, and I don't think Harold had much saved. I dunno how he's gonna pay for Rita, too. But the coffin's got to be nice on account of there'll be a crowd."

"Yes," Laury said absently.

"Harold's credit is good," Ferd said, still working at his problem, "but he don't make much.... Jim, how is Dave Carson?"

"He's in Doc Bekin's hospital. He's unconscious."

"He's fakin', I bet," Ferd said, and his giggle blurted out. "'Scuse me. My dyspepsia. You ain't gonna let him get away with it, are you, Jim? You ain't gonna let him get away with murderin' poor Rita Blenning just because old Carl Carson is a banker and has a lot of money, are you, Jim?"

"Maybe not," Laury answered.

"I voted for you, Jim.... 'Scuse me."

"That's all right," Laury said. "So long, Ferd."

Laury went back through the anteroom and out into the damp chill of the wind. The buildings of the main street stretched away from him in a double straggling row, looking cold and colorless under the leaden sky, black smoke whipping away from their chimneys in driblets. Snow that the last thaw hadn't cleared away lay in slick discolored piles along the curb.

WALDO OOSTENRYCK was kicking his toes against the low

cement step. He was bundled clumsily into a thick overcoat

that had belonged to his father. He wore mittens with leather

facings on their palms and a lumberjack's cap with fur

earflaps. "Find any clues?" he asked, peering eagerly up at

Laury through his thick glasses.

"Oh, sure," Laury said casually.

"How many? What were they?"

Laury didn't answer. He was watching a man cross the street, coming diagonally toward them.

"Boy!" Waldo said. "Here's old Carl Carson now!"

Carl Carson was thick-set, and there was solid slow strength in the way he moved. His heavy-joweled face looked tired, and the lines were deep and harsh around his mouth.

He nodded stiffly to Laury. "Hello, Jim.

"Hello, Carl," Laury said. "Waldo."

Waldo's mouth was open. "Huh?"

"Go inside and look for clues. Take your time."

Waldo tripped over the low step and knocked his head against the door. He tried to pull the door open, finally pushed it and fell into the funeral parlor.

"How do you put up with him?" Carson asked.

"You can get used to anything with practice," Laury said idly. "And his father controls 150 votes in the northern part of the county."

"I see." Carson looked down at his feet and then up again. "This is an awful business, Jim. Can you tell me anything more about it?"

"Dave and Rita went to a show together," Laury said. "Afterwards they stopped in and had hot chocolate at Bernie's Candy Shop. Then they drove out north, past the limekiln, and parked on that side road west of the old Snyder Mill in back of the cemetery. We found Rita in the car there. The door was open, and she was half-in and half-out. She'd been hit with a tire-iron. It was lying beside the car."

"Doc Bekin says Dave was hit with that same tire-iron," Carson stated. "It gave him a bad concussion."

"Is he going to be all right?"

Carson nodded. "I guess so. Jim, that wasn't Dave's tire iron. He didn't carry one. I know because the one time I was silly enough to ride in that streamlined puddle-hopper of his he had a flat. Of course he had no spare. He didn't have a tire iron either."

"Maybe he got one after that."

"No," said Carson. "Dave is absent-minded. Sometimes I think he's played so much football he's punch-drunk, but I suppose all parents have doubts about their children's sanity now and then."

"Yes," said Laury, watching him.

Carson cleared his throat. "I know what people are saying. They think that Dave and Rita had a fight and that he hit her with the tire iron and then hit himself over the head and ran through the cemetery pretending he had been knocked goofy so he wouldn't be suspected of Rita's murder."

"I've heard it hinted," Laury admitted.

Carson said: "Well, I'm his father and a little prejudiced on that account, but I don't think Dave is the type that hits people with tire irons. He's been mad at me lots of times, and he never got that violent about it. If he wouldn't do it to his father, he wouldn't do it to a stranger."

"You could hardly call Rita a stranger, could you?" Laury asked. "I got the idea somewhere that she and Dave were serious about each other."

"Then you got the wrong idea. Rita was pretty and cute, because she was young, but she was no deeper than a bird bath. She'd have made Dave miserable if he'd married her."

"Did Dave know that?"

"Yes. I told him so."

"What did he say?" Laury asked curiously.

"Told me that I was a hard-hearted old fossil with a soul like shriveled shoe leather."

"What did you say?"

"I admitted it. It's true. But what I said about Rita was true too, and Dave knew it."

"Do you suppose he told Rita what you said?"

"Dave is dumb," said Carson, "but not that dumb."

"If he had told her," Laury said, "I imagine she'd have been sort of put out about it."

"Probably."

They were silent for a moment and a car went past them with a loose chain thumping noisily under one fender.

Carson said slowly: "Being a banker in a small town like this is not all roses, Jim. You have to be hard sometimes, and people get the idea that you enjoy it, that you're sitting there snickering every time you turn down a request for a loan. No one will ever admit that he's a bum risk. He blames your actions on personal spite. A banker gets handed all the dirty little jobs that have to be done, just as a matter of course. People, even the best of them, resent him. They get a sort of a thrill when they think the banker is going to get it in the neck for a change. That makes them see things a little cockeyed. I'd like you to remember that, Jim."

"All right," said Laury. "Harold Blenning is coming this way."

Carson's face looked a little older suddenly. He set his shoulders solidly and turned around and waited for the other man to approach. His voice was even and emotionless as he said, "Good morning, Harold. I can't tell you how badly I feel about Rita. You and your wife have my deepest sympathy."

Harold Blenning stared at him without answering.

"Goodbye, Jim," Carson said in the same even tone. He walked down the street toward the bank, his heels clicking hard and crisp on the cement.

Harold Blenning said, "He's a mean man." He coughed once ineffectually, putting his gloved hand to his chest. His eyes were watery and red-rimmed. "Mean and hard. Don't care for nobody."

"He cares for his son," Laury said. "A lot."

"No, he don't," Blenning denied. "Not a bit. He's always mockin' at Dave—makin' fun of him because he's good-hearted and jolly. Hates for anybody to be happy, old Carson does. He wants to make Dave sour like he is."

"I don't think so," Laury said.

"I do. I know so. Old Carson cares more for a dollar than anything. He's a mean one. Dave ain't like that. Dave's a good fella. He'd never do that to Rita. No, sir. But old Carson would. You just remember that, Jim. He hated Rita, and there ain't anything he wouldn't 'a' done to stop her and Dave from marryin' like they wanted."

"Would he have hit his own son with a tire iron?"

"Yes, he would," said Harold Blenning. "He's that mean. And that's the first thing my poor wife said when she heard about our Rita. She yelled right out that it was old Carson that was to blame. You remember that."

"I'll keep it in mind," said Laury.

Blenning went in the funeral parlor and Waldo bumped into him in the doorway and stumbled down the cement step.

"Jim," said Waldo eagerly, "did old Carson offer to?"

"Offer to what?" Laury asked.

"Bribe you to lay off Dave?"

"Oh, sure," said Laury.

"How much, Jim? Five hundred?"

"Yeah."

"Boy!" Waldo exclaimed. "Did you take it?"

Laury shook his head absently. "No. I'm holding out for a thousand."

"Well, I dunno," said Waldo doubtfully. "Five hundred's a good bribe. It wouldn't be very hard for us to frame somebody, Jim. I mean they do that every day in the cities. I've read all about it, so I can tell you how."

"Later," said Laury.

He started up the street, and Waldo trotted along beside him.

"Jim, do you want me to tell you my theories of the case?"

"Not right now. After a while."

"Where you goin' now, Jim?"

"Back to the jail."

"Are you gonna grill suspects there, Jim?"

"No."

"Well, what are you gonna do, Jim?" Waldo demanded.

"Take a nap."

LAURY'S office was pleasantly warm and gloomy. He was lying

on the cracked leather couch, hands folded behind his neck,

staring up at the shiny steam pipe that stretched diagonally

across the ceiling, when Waldo came in and looked at him

disapprovingly.

"You been sleepin' for two hours. Are you ready now?"

"Ready for what?" Laury asked.

"To hear my theories of the case."

"All right, Waldo," Laury said.

Waldo had his notes typed, and he referred to them importantly. "Well, first there's the physical aspects of the case, and they ain't much because frozen ground and packed crusted snow won't take good footprints and everybody wears gloves when it's cold so there wasn't any good fingerprints. So we've got to ratiocinate."

"Do what?"

"Use our brains. Now first we'll take the mysterious stranger."

"Who is he?" Laury inquired.

"He ain't a he, he's a theory. The police in cities always use him when they're baffled. They go and pick up some old bum and beat him over the head until he confesses."

"That sounds like a nice idea."

"Not for us," Waldo said impatiently. "There ain't no mysterious strangers in this town. Of course, we could always get the police in Lake City to catch us an old bum and ship him down here so we could frame him, but I don't think we oughta do that except as a last resort. I think first we oughta arrest the person who really murdered Rita."

"That's a pretty radical notion," Laury said.

Waldo leaned over him earnestly. "I know it, Jim. It's contrary to all modern police practice, but don't condemn it until I explain how I got it figured out. I was stopped for a while because old Carson is gonna bribe us and my preliminary survey indicated he was guilty."

"Is that so?" Laury said.

"Sure. It was obvious. He didn't like Dave to go with Rita. He knew they were out together last night, and he knew they parked out there by Snyder's Mill lots of times. So he laid for them. He bashed Rita, and then Dave got mad at him for doin' that so he bashed Dave, only not so hard."

"But now you don't think he did?"

"Not after he showed he was anxious to cooperate with us."

"Cooperate?" Laury repeated.

"Sure. That's a term the police in cities use when they want you to bribe them. They ask you if you're gonna cooperate. If they ask you if you're gonna cooperate with the constituted authorities, that means you've got to bribe the district attorney too. It's very technical."

"I can see that," said Laury.

"So I took a secondary survey," Waldo said. "Itemized. And now I know who is guilty."

"Who, Waldo?"

"Rita's mother. Mrs. Blenning. She's got social ambitions and she wanted Rita to marry Dave. But Dave's old man said no. So Rita was willing to sacrifice herself for Dave's happiness and not marry him. When Mrs. Blenning heard that she went into a frenzy and hid in Dave's car when it was parked in front of the picture show and beat them over the head when they parked back of the cemetery."

"That's very interesting," Laury commented gravely.

"So we'd better arrest Mrs. Blenning right away," said Waldo. "We'll grill her. I know how to do it. We'll shine a strong light in her face and take turns yelling questions in her ear and threatenin' to beat her up. When she's real scared and shaky and exhausted, we'll take her over to the funeral parlor. I'll hide under that table that Rita's lying on, and when you bring Mrs. Blenning in, I'll make Rita sit up and point at her. That'll fix her. She'll either confess or throw a fit."

"I'd bet on the fit," said Laury. "Have you got any more theories, Waldo?"

"No. But I'll think of some."

"I'm afraid you will," Laury agreed. "In the meantime, send Tut Beans up here as soon as he comes in."

Tut Beans was a wry, shy man with a skin the texture of carefully polished leather. He sat down carefully in the chair Laury indicated and looked at the floor between his feet.

Laury said, "Take your time, Tut, and tell me what happened last night."

"It was a mite after midnight, I reckon," said Tut in a barely audible murmur, "and I was sittin' in the jail office, maybe dozin' a little. Abe Frelich called up and said Dave Carson was drunk and playin' football in the cemetery and for me to come and get him. I said for Abe to do it. I said he was the caretaker of the cemetery and it was his job." Tut looked up at Laury and down again instantly. "It was all-fired cold out."

Laury nodded. "What did Abe say?"

"Said he wasn't gonna. Said he wouldn't fool with Dave Carson. Said old Carl Carson was the chairman of the cemetery committee and Abe wasn't gonna get on his blind side by roustin' Dave around. So I said I'd come."

"And then?"

"I woke up Billy Lee and let him out of his cell and told him to keep track of the place. Was that all right to do, Jim? Billy bein' a prisoner? Didn't want to leave the jail without nobody watchin'."

"Sure, Tut. How long has Billy got to serve yet?"

"Mite over two months."

"I guess we'll have to frame him, like Waldo is always advocating, and get him sentenced again. He's too valuable a prisoner to lose."

"That Waldo," said Tut diffidently. "Seems to me like he has overly queer ideas. Don't seem reasonable to me."

"They aren't," Laury told him. "Don't pay any attention to them and don't argue with him. There's no point in it. When anybody gets as far off base as Waldo is most of the time, you might just as well let him dream."

"Been doin' that," said Tut. "Got out the county car last night and went to the cemetery. Found Dave there. Knew right away he wasn't drunk. Had the staggers, like a sick horse. Had blood on him, so I took him to Doc Bekin. Doc said it wasn't Dave's blood, so I called you. Mighty ashamed to waken you." Tut cleared his throat. "Did I do what I should, Jim? I like this job mighty well. Sure grateful to you for gettin' it."

"You do fine, Tut. You're my best deputy."

Tut swallowed hard. "Makes me mighty pleased to hear that, Jim. I'll—I'll be gettin' to work."

"All right, Tut."

THE wind had died now, but the chill in the air was sharper

and more penetrating. The steps squeaked mournfully under

Laury's feet as he climbed up to the high front porch. He

moved his hand toward the white circle of the bell and then

the door opened with a rush and Mrs. Frelich said, "Hello,

Sheriff! Come in and sit!"

"Afternoon, Mrs. Frelich," Laury said, and entered the narrow hall.

Mrs. Frelich indicated another door. "In here by the stove where it's warm. I've got some hot coffee right on the stove. I'll get you a cup."

"Not just now, thanks. Hate to bother you, Mrs. Frelich, but I'd like to ask a question or two."

"Why, yes," said Mrs. Frelich. "Anything. Abe said you'd be here, and I've been waiting. I'm so sorry about all this. Rita was such a sweet girl. I remember when she was born just as well. And Dave Carson. How is he, Sheriff?"

"He's still unconscious. He got hit pretty hard."

"His poor dad. I'm going to stop in and say a word to him and the Blennings too. It's terrible, the whole thing. Those poor people."

"It's hard for them," Laury agreed. "Will you show me the window where you were standing when you saw Dave?"

"Why, yes. Right up these stairs."

He followed her up and then along the narrow hall to the back bedroom.

"Here," said Mrs. Frelich. "This one. The wind was blowing like sixty, and I got up to close it."

Laury looked out the window and down the gray snow-scarred slope past the precise line of the iron fence. A dark figure was moving slowly among the tombstones.

"Abe's fixing the Blenning lot," Mrs. Frelich explained. "It makes you feel bad to think... Rita was always so warm and alive."

"Seen much of Dave Carson lately?" Laury asked.

"Why, yes," said Mrs. Frelich, puzzled. "To speak to, I mean. When he comes home for weekends and vacations from college. I saw him just day before yesterday, and he joked and joshed with me. I never dreamed then..."

"Did you recognize him when you saw him last night?"

"Why, no," said Mrs. Frelich. "I was that scared I wouldn't have recognized anything."

"Ever had any trouble with your eyes?"

"Why, no," Mrs. Frelich said uneasily. "No. It's a little hard for me to read fine print, that's all."

Laury pointed. "See that end-post of the fence? There's a short section between it and the next post this way. How many pickets in that section?"

"Five," said Mrs. Frelich slowly.

Laury nodded. "Thanks. Well, I'll be going along."

They went silently along the hall and back down the stairs.

"Some coffee?" Mrs. Frelich suggested uncertainly.

"No, thanks."

Laury opened the door and went out on the porch. He hesitated at the head of the steps and turned around. Mrs. Frelich hadn't shut the door. She was watching him, and her plump face was fined and drawn and old.

Laury cleared his throat and then he couldn't think of anything to say. He went down the steps and on down the slope.

When he was close enough, he counted the pickets in the short section offence. There were five of them. Laury turned around and walked along the fence to the gate and went through it and along the path between the raised grave plots.

Abe Frelich was hunkered clumsily down on his heels beside an oblong of black mud-clotted earth. A shovel and a pick lay on the ground beside him.

"'Lo, Jim," he said. "I was just thawin' the ground a bit. It's froze pretty hard for diggin'...."

"Abe," said Laury. "I'm going to have to arrest you for murdering Rita Blenning."

Abe Frelich's face looked thick and lumpy. He spun around and came up to his feet with the pick raised back over his shoulder.

LAURY was lying on the couch in his office with his hands

folded behind his neck. "Come in," he said.

Carl Carson opened the door. "Evening, Jim. Don't want to bother you. Just thought I'd drop in..."

"No bother," Laury told him. "Sit down. How's Dave?"

"He's come around all right, but he doesn't remember anything that happened. Doc Bekin says that isn't unusual with concussion. Jim, do you mind telling me how you knew it was Abe?"

"No. Mrs. Frelich is far-sighted. She's got eyes like a hawk for distance. She didn't recognize Dave when she saw him running around in the cemetery—didn't even know what it was, let alone who. But Abe did. Not only that but he popped right up with an explanation that was about as far-fetched as they come. He said Dave was drunk and playing football."

"What was Dave doing?"

"Chasing Abe. He was dizzy and weak and knocked goofy, but he kept going. Abe ran away from him and got in the house and pulled his nightshirt over his clothes. He was pretty scared. He didn't mean to kill anybody. He had laid for Dave and Rita several nights. He had a flour sack for a mask, and he was going to scare them plenty. But Dave jumped him.

"Abe knocked Dave down. Rita was trying to get out of the car to run, and Abe thought she was coming after him. He hit her. Then he ran himself. Dave got up and went after him."

Carson cleared his throat. "Why did Abe want to scare them, Jim?"

"Don't you know?" Laury asked.

"Well, was it because of what I said to Abe a couple weeks back?"

"Yes."

Carson sighed. "That's what I meant about being a banker... I'm chairman of the cemetery committee, and I was the one who had to speak to Abe. He was getting careless and lazy and insolent, and he was drinking all the time. He made an awful mess when he fixed the grave plot for the Blennings' Uncle Mort. Harold Blenning complained to me about it. I told Abe he'd have to straighten out. I was pretty rough with him."

"Yes. He held it against you and the Blennings. The best way he could get back at you both was through Rita and Dave."

"Did he make any trouble when you arrested him, Jim?"

"He started after me with his pick."

"What did you do?"

"Told him his mother was watching us from the house. He dropped the pick and started to cry. It wasn't very pleasant."

"No," Carson agreed heavily. "No. I'll see that Mrs. Frelich is cared for.... I spoke to John Tyler about defending Abe...."

"A lawyer won't do Abe much good," Laury said. "He confessed everything."

Carson nodded. "Well... So long, Jim."

Carson's solid footsteps died away in the hall, and Waldo put his head cautiously around the door.

"Did you get it in unmarked bills?"

"What?" Laury said.

Waldo gestured impatiently. "The bribe!"

"Oh, that. No. I decided taking money was too risky. I made Carson promise to support me when I run for governor."

"You did?" Waldo exclaimed. "Boy! That was a smart deal, Jim! Why, with his money behind you, you can just buy thousands of votes!"

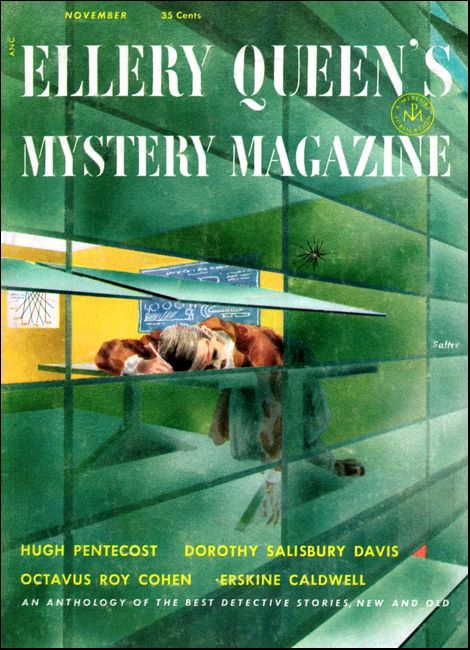

Ellery Queen's Myster Magazine, November 1953,

with "Walk Across My Grave"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.