RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Argosy, 1 April 1939, with first part of "Sand In The Snow"

.

California has snow-capped peaks and burning sandy wastes—and Jim Daniels, following the threads of the strangest case he ever undertook, found that sudden and violent death was apt to occur in both climates. In fact, peril seemed to travel in the wake of the Young Millionaire with the Scarred Face, ready to pounce at any moment. An exciting novel of a brilliant young attorney's midwinter vacation from safety.

IT was his wife's mink coat that started the whole thing. Jim Daniels had no reason to get mad about it. Ordinarily he wouldn't have. It just came at the wrong time. He admitted all that later, but by then it was too late. The ball was already rolling down its swift, disastrous path.

Late on that decisive afternoon, he was sitting in his office reading over his latest copy of the Supreme Court's Advance Reports. The crook-necked lamp on his desk was on, and pooled the light in a greenish cone that glistened back from the pages of the Report, and profiled the hard-cut strength of his features. His eyes smarted from the fine print, and he had one hand up shading them. He was thin with high, square-set shoulders, and even in repose he gave a greyhoundish effect of restless, hard-driving energy, of unquenchable and impatient ambition.

Cora Sue Daniels opened the door softly and peeked at him around its edge. She was wearing a hat that looked like an exaggerated felt stocking cap.

"Hello, dear. Plunk said you were alone."

Daniels marked his place with a forefinger and looked up. "Hello, Cora Sue. Come in."

She crossed the office, leaned over the desk and kissed him, brushing his forehead with lips that were soft and cool and possessive. Daniels raised his hand and dabbed automatically at the spot. He had learned from experience that his wife's lips were likely to leave an indelible red mark on anything they touched.

Cora Sue twisted the neck of the lamp until it reflected on her slim, small person like a spotlight. "This is my new coat, Jim. Isn't it sweet?"

Jim winced at the choice of the adjective and watched her obediently as she twirled slowly around, holding the coat away from her and then close to her body, and then posing with a mannequin's occupational hauteur, her head tilted back.

"It's nice," Daniels said absently.

His adjective wasn't good either. Nice... The furs were deep and rich and gleaming, perfectly matched, perfectly shaded. Daniels was reflecting that it probably cost just about twice as much as he had made in the last year. But that wasn't his affair. He didn't have to pay for it.

Cora Sue's father, A.J. Bancroft, had settled a ten-million-dollar trust fund on her when she was eighteen. The income on the trust was irrevocably and completely hers.

Daniels didn't take to the idea. That and the other hundred-odd million that A.J. Bancroft could shake out of his sleeve if the occasion demanded had come very close to preventing the marriage of Daniels and Cora Sue. Daniels was no fool. He liked money just as well as anyone else. But he knew that when a hundred-odd million is concentrated in one fortune it ceases to be merely money. It attains an new identity. It becomes a responsibility, and a very great one. Such a responsibility, in fact, that the sheer mass of it is liable to dwarf and absorb the personality of anyone closely connected with it.

That was what Daniels didn't want. He had a fierce ambition to carve out his own career. He didn't want any of Cora Sue's money or any of A.J.'s either. He wasn't interested in the mere accumulation of money. He wanted to excel in his own profession on his own merits. He was sure that he could.

But Cora Sue had the trust fund. It couldn't be revoked. She couldn't give it away if she wanted to. Daniels was not selfish enough to want her to deny herself the benefits of the income. Nevertheless it made his own attainments seem pretty unimportant, and sometimes that annoyed him. It did now.

He was frowning, and Cora Sue said: "Don't scowl so, dear. I think you've been straining your eyes lately. You need glasses."

"No," said Daniels. "My eyes are just tired."

Cora Sue nodded. "They are. And so are you." She watched him thoughtfully, chewing on her under-lip. "Jim...?"

"What?" Daniels asked, bracing himself mentally. He recognized the signs.

"You have been awfully tired and nervous lately..." She took a deep breath and came out with it. "Why don't we go on a nice vacation, so you can rest?"

"Vacation?" Daniels repeated blankly. "At this time of the year?"

"Yes! Because it's this time of the year. Because it has been a nasty winter, and still is. Just look at the weather."

Daniels glanced reluctantly toward the window of the office. The pane reflected the green desk-light; and beyond it the wind howled in slow, mournful cadence, tapping and prying with myriad fingers that were half sleet, half snow. The whole city was cold, smoky, snowy chaos.

"And you can't get an injunction against that," Cora Sue said, waving a hand toward the window.

"Yes, I know," Daniels admitted. "But I can't go on a vacation now."

"Why not?"

"Because the courts are in session. This is the busiest time of the year for them—and for me."

"You don't have any customers—oh, all right: clients—right now, and Plunk said you didn't have any cases scheduled for trial for the next couple of weeks."

Daniels' lips tightened. "I don't have now—no. But I will have."

"Jim, you need a vacation."

"Where would we go on a vacation at this time of the year?" Daniels demanded, exasperated.

"To California."

Daniels stared at her incredulously. "California!"

Cora Sue nodded. "Yes. Blair Wiles has invited us to visit him. He has places both at Phantom Lake and Desert Sands. You see, first we could go to Phantom Lake for the winter sports and then go down to Desert Sands and bake the cold out of us and swim and lie in the sun..."

Daniels was watching her narrowly. "Who is this Blair Wiles?"

Cora Sue shrugged casually. "Oh, he's an old friend of the family. Owns a shipping line, or something." Cora Sue made the shipping line sound like an aunt's old bed-jacket.

"You mean the Wiles Freight Line?"

"Yes. He inherited it. He doesn't run it himself. He just sits and collects dividends."

"Nice," Daniels commented. "The answer is still 'no.'"

"But Jim! We could fly, and you wouldn't be gone long, and it wouldn't cost much! I could pay..."

"No," said Daniels.

"Please, Jim! I've already written Blair and told him that we'd come."

"Then write him again and tell him we're not."

"Jim, I haven't seen Blair for years and years, and I..."

"No," said Daniels. He kept his voice even and low with the effort he would have used on a feeble-minded, tongue-tied witness. "Now will you please go away? I'm trying to work." He reached out his hand for her.

Cora Sue stood still for a moment, staring at him. Her blue eyes were tearful, and her lower lip poked out in a childish pout. Daniels stared steadily back at her. He let his hand fall, though.

Cora Sue swallowed with a gulp. "All right, Jim. I'm sorry I bothered you. Goodbye."

"Goodbye," Daniels said stonily, and felt like a heel.

SHE closed the door very softly behind her. Daniels

blew out his breath and immediately began a mental

inventory of his idiocy. It was very thorough. The

trouble was Cora Sue was right. He did need a

vacation. His nerves were as jagged as the teeth of a

saw.

But he couldn't take one now. Figured from the angle of court business, this was his most important season. And for the first time in his career he was beginning to feel that his practice was no longer a series of loose and casual threads that had no connection with each other. It was beginning to have a form and personality, a pattern. It was going to go on now, growing. He had to be here, watching and guiding it, nursing in along until it got to the point where he could sit back, like the parent a grown son, and let it support him. He couldn't take a vacation. His conscience would allow him no rest even if he did.

The door opened, and Plunk Nelson said: "Hi, boss," in a falsely cheerful voice.

Plunk was short and squat and ugly. He had a thick-lipped mouth, and he wore enormous horn-rimmed spectacles that gave him the vaguely stupid air of a frog trying to read a book. He was Daniels' secretary, receptionist, assistant, and general major-domo. He was determined to become an orchestra leader. He was holding his job temporarily, until such time as Fame and Fortune came along and tapped him on the shoulder. This made a pleasantly restful legend, and gave him a coat of protective coloration.

Daniels said: "By any chance, do you remember my telling you not to give out information about my clients or my cases?"

Plunk blinked. "Well, Jim, she's your wife..."

"Never mind who it is. Don't do it."

Plunk shook his head vigorously. "I won't again. Honest. But, Jim, you really ought to take a vacation..."

Daniels didn't say anything. But his look was so eloquently murderous that Plunk shivered and backed out of the office and shut the door hurriedly.

Daniels sighed. He covered his eyes with the palms of his hands, bracing his elbows on the desk. He breathed evenly and slowly, trying to fight down the quivery jumping rawness of his nerves.

He was still sitting that way when Plunk opened the door again. Daniels looked up at him.

"A customer." Plunk's eyes were glistening eagerly behind the thick lenses of his glasses. "A dame. And guess, who?"

"I don't feel like guessing games," Daniels said savagely. "Who?"

"Mrs. Gordon Gregory!" Plunk said triumphantly,

"Who's she?" Daniels demanded.

"The babe with the production-belt husbands!"

"That what?" Daniels asked blankly.

Plunk spread his hands. "Don't you ever read the scandal sheets, Jim?"

"Not if I can help it."

"Well, look," said Plunk. "Mrs. Gregory is the widow of the Gregory that owned all them steel mills. He married her when he was about eighty-two because he said she had such a cheerful smile—ha-ha!—and he left her all his dough when he died, on account he was an orphan and didn't have no kids. She's got so much she can't count it."

"What about the husbands?" Daniels asked.

"She's been married about six times since then, is all. Every one of 'em took her for a ride, and she had to settle plenty on 'em to get rid of 'em. On top of that she's been sued about ninety times by other guys for breach of promise and by dames that claimed she alienated their husbands' affections. If you could land her business, Jim! Boy! She's always knockin' around in court for one reason or another!"

Daniels nodded slowly. "Send her in."

"Come to think of it," Plunk said dreamily, "maybe I ought to shine up to her. Maybe she'd put up some dough for me to organize a band with. I got just the arrangements and the boys to step right into some big broadcasting spot and wow 'em. I can see the bunch now—all with monkey-jackets and white pants with gold braid down the seams—settin' there and ridin' out a tune while I wave the stick and give the crowd the old personality—"

"Send—Mrs.—Gregory—in!"

Plunk came out of it. "Uh? Oh. Sure, sure. Right away, Jim."

MRS. GREGORY was utterly different from what

Daniels had expected after Plunk's categorical

buildup. She was small, rather plain, and she did

have a nice smile. It was a pleasant, wistful,

appealing smile, childlike and trusting and timid. It

begged people not to be too outrageous. She wore a fur

coat that made Daniels think of Cora Sue's multiplied

by two. She had brownish, straight hair and a round,

plain face that was innocent of any makeup. She wore

three diamond rings on one hand and four on the other,

and any of the stones could have been used as a naval

base.

Daniels blinked; his eyes hurt. Mrs. Godfrey's hands could have illuminated a Hollywood opening. Plunk pulled up a chair, bowed Mrs. Gregory into it with penguin grace and tiptoed out of the room.

Mrs. Gregory noticed Daniels' eyes riveted helplessly on the diamonds, and she held up her hands and wiggled her stubby fingers.

"I like diamond rings," said Mrs. Gregory, smiling. "Don't you?"

"Well—yes," Daniels admitted. He liked the Fourth of July, too.

"I've always liked them," said Mrs. Gregory, admiring the rings. She looked over them at Daniels. "You're Cora Sue Bancroft's husband, aren't you?"

"Cora Sue Daniels is my wife," Daniels said shortly.

"Of course. That's what I meant. I've heard ever so much about you. How clever and brilliant—and honest you are."

"Well, thank you," Daniels said, embarrassed. "You—you wished to see me about some business?"

"Oh, yes! This is very, very confidential."

"Is it?" Daniels asked impassively.

"Yes. Very. Now I want to ask you a question, Mr. Daniels. Is it—is it possible for a lawyer like you to go with a client to transact some business. To—to protect her?"

"Surely," said Daniels.

Mrs. Gregory nodded, relieved. "That's fine. This business of mine is quite a ways away. It will take you several days."

Daniels held up his hand. "Just a moment, then. You understand that if I have to leave my office for any length of time, it will mean neglecting any other clients that might want my services. In other words, it will cost you quite a lot, depending on just how long I'm away."

Mrs. Gregory's hand made a glittering, casual sweep in the air. "Oh, that's all right! The cost doesn't matter. This is very important."

"I see. Where am I to go with you?"

"To California."

Daniels blinked. "You said—California?"

"Yes. At Phantom Lake."

"Oh," said Daniels slowly. "You wouldn't, by any chance, be planning on staying at a place owned by a man named Blair Wiles, would you?"

"Why, yes! Aren't you clever though. Blair invited me to come and stay, and I'm sure he wouldn't mind if I brought my attorney along—"

Daniels stood up. "But I'd mind. I'm sorry, Mrs. Gregory. I can't handle your business for you."

She stared up at him. "Why not?"

Daniels shook his head. "I don't wish to discuss the matter further. I can't handle it. Doubtless you can find another attorney who will be glad to. Good day."

Mrs. Gregory protested helplessly. "But—but you must! I don't know any other attorney who can be trusted—that I'd want to trust with—with—"

Daniels went over and opened the door. "I'm sorry. I can't serve you in this case. Good day."

"But there's no one else—" Mrs. Gregory wailed.

Daniels moved the door meaningly. "Good day, Mrs. Gregory."

She went slowly, still protesting vaguely, like a bewildered child. Daniels went back to his desk. He was so angry he couldn't control the trembling of his hands.

Plunk appeared in the doorway, his face twisted up into a weirdly dismayed grimace. "Jim! Jim, what—what—"

"Shut up and get out!"

"Huh? Oh. Sure. Sure, sure, Jim."

Daniels picked up the telephone on his desk and dialed savagely. He waited in a fever of darkly bitter rage, and a polite smoothly southern voice said:

"This here is the residence of Mr. James Daniels."

"Call Mrs. Daniels."

"Yes, sah, Mr. Daniels. Hold the phone."

Cora Sue's voice said cheerfully: "Hello, Jim, dear."

Daniels' words came in a sudden harsh rush: "Listen, Cora Sue. I told you that I am not going to take a vacation! I meant that! I am not going to go to California! And I don't like the idea of your sending your friends up here and trying to bribe me into going with fake cases and charity fees! I will not have you interfering with my business with tricks like that! Is that clear?"

"But, Jim! Wait! I-I don't know what—"

"I'm not going to argue about it! But don't ever do it again!"

He slammed the telephone back in its cradle and sat down in his chair. He was breathing as though he had just finished the ascent of Everest and now he felt a queer, let-down sickness deep inside him. He had let his temper get completely away from him.

Plunk opened the door again, cautiously. "Jim..."

"What?" Daniels asked wearily.

"Listen. When Mrs. Gregory went into your office, she left her handbag on a chair in here. It's set with diamonds and stuff, and I didn't want it lyin' around loose like that, so I picked it up and put it in the desk. But it opened when I took it out again to give it to her just now as she was leaving, and there was a gun in it!"

Daniels shrugged. "Well, what of it? She has the right to carry a gun if she wishes. Was it set with diamonds?"

Plunk shook his head slowly. "That's it. I wouldn't have thought nothing of it if it had been one of them funny little pearl-handled babies women carry when they think they gotta have protection or somethin'. This here one wasn't. This one was a .38 Smith and Wesson Special. It filled that whole bag full. That ain't no ladies' toy, Jim. That gun packs a mean punch."

"Forget it, Plunk," Daniels said. "I'm not interested in Mrs. Gregory and her armament. She can string a Howitzer around her neck for all of me."

Plunk squinted, worried. "I dunno now, Jim. A woman wouldn't go carryin' a whoppin' big revolver like that around with her unless she had a mighty good reason for doin' it. That thing must weigh two and a half pounds. You suppose she's plannin' on takin' a pop at somebody?"

"I wouldn't know," Daniels said with magnificent finality. "Mrs. Gregory and her possible course of action don't interest me in the slightest."

Later, he was to think of those words often.

IT was dark when Daniels drove down the wide, tree-lined street. The wind had stiffened, and the snow came down in a long, fierce slant, plastering itself endlessly against the little coupe's windshield. The windshield-wiper groaned and clicked and muttered, fighting unavailingly to keep its measured pace.

Daniels swung wide into the middle of the street, chains banging under the fenders, turned up into a wide, graveled driveway. He went through an open iron gate, past the thick hedge beyond it, and the great, high, white length of the house was ahead of him.

Daniels winced mentally every time he saw the house. That was foolish, too, and he admitted it. It wasn't his house. It was Cora Sue's.

Cora Sue had seen it at one time or another and liked it. When she had gotten married she had called up the trust company and told them so. That was all there was to it. When Cora Sue and Daniels returned home from their honeymoon, the house was all ready for them—bought and paid for, furnished by the city's most exclusive and expensive interior decorator, staffed with a complete set of properly wooden-jawed servants.

The trust company was efficient. No doubt about that. Daniels often thought they were a little too efficient. They ran the place. They hired, fired, and paid all the servants—except Poinsetta, Cora Sue's personal maid. They paid all the bills. Daniels never even saw any of them. Not that the trust company officials ever intruded. They were as unobtrusive as the plumbing. Daniels had never seen any of them, either. But they were always present in spirit. Daniels felt like the favored guest of a palatial hotel.

Stopping in front of the wide front entrance, he put these thoughts resolutely out of his mind. Those things, and a good many others, were annoying, but they weren't Cora Sue's fault. They were the fault of the fact that she had been born with a lot of money. She couldn't be blamed for that any more than Daniels could be blamed for the fact that he was born with a strawberry mark on his left breast. Daniels had let his temper slip once today, and he was determined not to let it happen again. He was already feeling pretty contrite about the way he had spoken to Cora Sue over the telephone.

His footsteps sounded hollow and cold going across the porch, and then the big front door swung back and bathed him in warm, soft light.

"Evenin', Mr. Daniels!" Poinsetta greeted. She was fat and short and very black. She had been Cora Sue's nurse ever since Cora Sue's mother had died, and she was an established and respected member of the household. She took no back talk from any of the "company trash" as she called the servants installed by the trust company, and next to Cora Sue, Daniels was the apple of her eye.

"Hello, Poinsetta," Daniels said.

A uniformed butler came in through the door to the servant's quarters and advanced with a measured, stately tread.

Poinsetta eyed him evilly. "Git!"

The butler stopped short. He blinked at Poinsetta warily and then beat a dignified retreat.

"Huh!" said Poinsetta triumphantly. She helped Daniels out of his coat, shook the snow out of it carefully, hung it up.

"Mighty nasty weather, Mr. Daniels."

Daniels nodded absently. "Yes. Where's Cora Sue?"

Poinsetta opened her mouth vaguely. "Huh?"

"Cora Sue. Where is she?"

"Why—why, she gone."

"Gone!" Daniels echoed incredulously. "Gone where?"

"Californy."

DANIELS swallowed. He felt as lost and forlorn

as if he had suddenly been dropped in the middle of

a strange desert. His breath seemed to have caught

in a hot, tight ball in his throat, and he had to

swallow and then swallow again before he could speak.

"When—where..."

"She start goin' right after you call on the phone."

"Oh," Daniels said weakly. "Why—why didn't you go with her?"

"She say somebody got to stay home and take care of you because you ain't fit for to take care of yourself. And anyway, I got to watch this here company trash. They go to stealin' everything that ain't nailed down if I don't watch 'em."

"Oh," said Daniels.

Poinsetta watched him sympathetically. "You and Cora Sue, you got yourselves a mad on, huh?"

Daniels nodded slowly. "I guess so, Poinsetta."

"Cora Sue, she cry after you talk to her on the phone. She cry when she go, too."

Daniels stared silently and miserably at the floor.

Poinsetta said slowly: "Mr. Daniels, she ain't done what you said she done."

Daniels jerked his head around. "What?"

He stared at her.

"She ain't done what you bawled her out for."

"How do you know?" Daniels demanded tensely.

"She say so to me. She say you bawl her out for sendin' you fake cases. She say she don't know what you talkin' about, she ain't never done that, at all."

"Are you sure?" Daniels demanded, horrified.

Poinsetta nodded firmly. "I sure. Cora Sue, she don't never lie to Poinsetta. Never. Besides, she ain't gonna monkey with that business of yours. No, sir! She scared to death of that business. She tell me lots of times that business mean an awful lot to you, and she goin' to keep out of it and never bother you. She say when you get mad about that business, you can sure raise hell."

"I did this time, all right," Daniels admitted, staring blankly ahead of him. "I was sure she sent Mrs. Gregory with some crazy idea of fooling me into going to California. It was too much of a coincidence—Mrs. Gregory coming in right after Cora Sue had been talking about going the same place, wanting to pay me to go there... Good Lord! Now I have done it! Losing my temper and giving her the devil for something she didn't even do. Was—was she mad, Poinsetta?"

"No," said Poinsetta judiciously. "She just cryin'. But she gonna be mad—awful mad—pretty soon. That's the way she does. First she cries, and then she gets mad."

"She's got a right to be this time," Daniels said. He drew a deep breath, throwing his shoulders back. "Poinsetta! I'm going to California—now!"

Poinsetta grinned. "Yo' all packed." She waddled toward the stairs, stopped at the bottom to look back over one shoulder. "She goin' by the airplane."

Daniels nodded. He went into the study, took the telephone directory out of its carved mahogany cabinet, flipped through the pages until he found the number he wanted. He dialed it with quick, savage haste and waited impatiently.

A polite feminine voice said: "Northwest Air Lines."

Daniels said: "I want to reserve a passage to California on the night plane."

"I'm sorry, sir. All passenger planes are grounded on account of the storm."

"Grounded!" Daniels said blankly.

"Yes, sir. The last plane went out at four-thirty this afternoon."

That was the plane Cora Sue must have taken, and Daniels chewed his lip in indecision.

The polite voice said: "If you wish, sir, you can reserve passage on the morning plane at Salt City. That is out of the storm area. You can make connections by taking the train there tonight."

"All right," said Daniels. "Make that reservation for me. The name is James A. Daniels."

"Thank you, sir."

Daniels hung up and flipped through the directory again until he found the number of the railroad station. He dialed it, and when a voice answered, asked:

"What time does the Western Limited stop here tonight?"

"At seven-twelve, sir."

"Thanks," Daniels said. He looked at his watch. He had about a half hour to pack and drive ten miles through traffic across the city. He dropped the telephone back in its cradle and ran out into the hall.

"Poinsetta! Poinsetta! Hurry! My bag, quick."

"I hurryin', Mr. Daniels. Don't fret me."

DANIELS made it—by one sandy eyebrow. The train was moving by the time he got arranged in his seat. The Limited was a new, fast train, and it started without any rumbling or banging or jerking. It slid away into the night like a great, quiet beast, and the only noticeable noise was the slight click-click, click-click of its wheels over switches. It gathered speed imperceptibly, and scattered lights began to flick past like steaming yellow blurs.

Daniels leaned back into the cushioned softness of his seat and breathed evenly and deeply, trying to stifle the pounding thunder of his heart. This was the last car in the train, an extra, and there were only a few passengers in it.

Daniels looked them over casually, not very interested until he happened to notice the man across the aisle. He smiled sympathetically, then. The man was young, so young he could hardly be called a man. At the moment, he looked more like a boy because he was sleeping.

His thin face was wan and wearily relaxed. He was curled up in his seat, and his slight body swayed back and forth with the slight motion of the train. He was wearing a wrinkled, shiny blue suit that didn't fit very well. His hair was thick and brown and stubborn, sticking out straight in a clump at the back of his head.

Watching him, Daniels wondered what he was doing on a special-fare train like this one. The suit had the two-years-ago look of a hand-me-down, and its wearer didn't look exactly over-nourished. His cheeks were pinched and pale; and his body was scrawny.

The train went around a curve, and the boy swayed loosely outward away from the seat. Daniels thought surely he was going to fall off, and he stiffened, preparing to call a warning. But the youth didn't fall. Something held him by the left arm. Something that clicked a little.

The youth's left arm was covered by an overcoat, but the movement of his body had shifted the coat slightly, and Daniels caught a glimpse of bright metal under it. Daniels blew out his pent-up breath in a noiseless whistle. The youth's left wrist was handcuffed to the arm of his seat.

Another man came down the aisle and stopped beside the youth's seat. He was heavy-set, but he walked quickly and lightly for all of that. He wore dark clothes and a broad-brimmed black hat tilted casually on the back of his head. His face was broad and heavy-jowled, shot with tiny red veins, and his eyes were small and alert and suspicious staring at Daniels.

"Hello," Daniels said.

The heavy-set man's eyes didn't move or blink. "Hello," he said finally. He turned away then and took a couple of candy bars out of his pocket. He leaned over and touched the youth's thin shoulder. "Pete. Pete, wake up."

The youth slept on, drugged with weariness too old for his years and experience.

"Pete," said the heavy-set man again His voice was surprisingly gentle. "Come on, Pete. Wake up."

The youth didn't move, and the heavy cadence of his breathing went on unchanged. He was occupying all of the seat, and the heavy-set man stood uncertainly in the aisle, staring down at him.

Daniels said: "You can sit over here if you want to."

The heavy-set man glanced at him sharply again. He was silent for a moment, studying Daniels, and then he nodded and said:

"Thanks."

Daniels moved over, and the heavy-set man sat down beside him.

"Hate to wake him up," said the heavy-set man. He looked tired, too, now that he was relaxed. He took off his hat and wiped a flushed forehead with his handkerchief. "The kid ain't slept for two days. And besides, when he's sleeping he gets a chance to forget..."

"What?" Daniels asked.

"Things," said the heavy-set man.

Daniels was curious. "My name is Daniels. I'm an attorney." He took one of his cards from his wallet, extended it.

The heavy-set man looked at it thoughtfully. "Glad to know you. I'm Biggers—deputy-sheriff from Crater County, California."

"What did he do?" Daniels asked, nodding across the aisle. "Escape from the reform school?"

Biggers shook his head slowly. "No. I sure wish that was all he had done. He murdered his gal."

"Murdered!" Daniels echoed incredulously. "That kid?"

"Yeah. Pete Carson is his name. We had him in jail waitin' for his trial, and he lammed out on us. Got picked up back East on a vag charge, and they recognized him from our circulars. I'm bringin' him back."

"But he's so young!"

"Don't I know it?" Biggers asked gloomily. "Listen, I've known that kid for years. He's always been a good kid, and I've always liked him. What do you think I feel like—draggin' him back to what he's goin' to?"

"What is he going to?"

Biggers made a mute and eloquent circle around his neck with his forefinger and thumb.

"No!" said Daniels, sickened at the thought.

Biggers nodded wearily. "Only they don't hang 'em in California now. They put 'em in a gas chamber. But that ain't so pleasant to think about, either."

Daniels protested: "But if he hasn't been tried yet..."

Biggers shook his head. "It's one of them things. It's an open-and-shut case. It's on ice. Pete ain't got any defense at all, and this escape of his ain't gonna do him any good. I don't have to testify at his trial, thank God for that. This here is bad enough without that, too."

"Where did the murder take place?" Daniels asked.

"At the upper end of Crater County. That's the Phantom Lake district."

"Phantom Lake," Daniels repeated. That name was beginning to haunt him. It was like the refrain in a song you don't like that is played too often on the radio. First Cora Sue, and then Mrs. Gregory, and now a murderer. He looked up at Biggers. "Do you happen to know a man by the name of Blair Wiles?"

"Him? Sure." Bigger's eyes were alert and curious. "Friend of yours?"

"No. I never saw him in my life. I've heard about him, though, lots of times."

"Uh," said Biggers. He shrugged heavily. "Well, it just goes to show you."

"Show you what?"

"He killed a guy, but he's still runnin' around loose. He throws a bit more weight than Pete does."

Daniels stared incredulously. "Wiles... killed a man?"

"Yeah, It went down as an accident, and maybe—if you ain't too particular—that's what it was."

"How did it happen?" Daniels asked.

"Wiles was a lush. He had a handyman and stooge he took around with him to drive for him when he was too drunk. Name of Randall. Well, this time Wiles got drunk but he wouldn't let Randall drive home. They were up on that Phantom Lake road, and that ain't no place to get comical with a car. There's a lot of curves, and Wiles went off one of 'em. The car dropped a hundred feet into a canyon and burned. Killed Randall."

"Was Wiles hurt?"

"Plenty. Spent two years in a hospital. Nobody could figure out how he got even that much alive. I guess maybe you could say he paid for his little trick that way."

A dining-car waiter in a white jacket came through the car tapping his musical chimes softly.

"Dinnah. Last call for dinnah. Last call."

Biggers got up. "I'll have to wake Pete up now. He ain't been eatin' at all lately."

He took the handcuffs off Pete Carson's lax, bony wrist. He straightened the thin body up on the seat and shook him back and forth gently.

"Pete! Come on, now! Wake up!"

"Huh? What?"

"Wake up, boy."

"Huh? Oh." He dug wearily at his eyes with his knuckles. "What, Mr. Biggers?"

"We gotta eat, Pete."

"I-I don't think I want nothin' to eat, Mr. Biggers. I don't—feel like eatin'. You lock me up and go ahead. I'll stay here."

Biggers shook his head. "No, Pete. Come along now and eat something. Just for a favor to me."

Pete got up reluctantly. "All right, Mr. Biggers. I-I'll try, anyway."

"That's the boy. You come on now and wash up, and then you'll feel better. You gotta eat something once in awhile."

"Why?" Pete asked wearily.

Biggers cleared his throat uncomfortably. "Come on, Pete. Let's wash up."

THEY went on down the aisle, and Daniels watched

them go, his face twisted in instinctive aversion. It

was Daniel's inherent sympathy for the underdog in his

struggles with the merciless mill of the Law that had

spurred him on to becoming an attorney. He had never

lost that tilt-at-the-windmill feeling. He had it now,

for Pete Carson, stronger than he had ever had it

before.

He wanted to help, and he was wondering if there wasn't some way he could when he noticed the man standing quietly in the aisle beside his seat.

"Mr. Daniels?" the man asked. "Mr. James A. Daniels?"

Daniels nodded. "Yes." He stared curiously at the man. He hadn't noticed him in the car before. He was to learn later that this was only natural. Hassan had a gift for receding quietly into his background that would have taught a cheetah tricks in stealth.

"I am Prince Dak Hassan," he said, with a bow as faint as his accent. "I am very pleased indeed to make your acquaintance."

He made a quick sharp click of his heels. He was short and slender man with graceful, catlike movements. He wore expensive gray tweeds, dark blue shirt, a darker blue tie. His face was a perfectly smooth, round, darkly tanned oval, and his eyes were cool, round green. He had an ingratiating smile and perfect, glistering teeth.

"How do you do?" Daniels said blankly.

Dak Hassan bowed again and sat down beside Daniels without being asked. That was also characteristic.

"You do not know me? You have not read my name in the papers?"

"No," Daniels answered truthfully.

Dak Hassan shrugged gracefully. "It seems hardly possible. It is often there. In the society columns."

"I never read them." said Daniels.

"No?" Dak Hassan was surprised. "That is very strange—in your case."

"What do you mean—in my case?"

Dak Hassan smiled. "I cannot have made a mistake. You married Cora Sue Bancroft, did you not?"

Daniel's voice congealed slightly. "Yes."

Dak Hassan spread his hands. "So that is why I am surprised."

Daniel's frowned. "I'm sorry. I'm a little tired tonight, and I don't seem to be following you very well. Let's start over again. You said you were a prince?"

"Indeed, yes."

"Of what?"

"Radisztan."

Daniels blinked. "What did you say?"

"Radisztan. It was a province of the old Russian Empire."

"Oh," said Daniels.

"It is a very old title," Dak Hassan said modestly. "Mine is a very ancient and honorable family. Indeed, yes."

"Oh," Daniels said again.

"Is yours?" Dak Hassan asked.

"No," Daniel admitted.

"You have no social position?"

"Not a bit."

"How strange," said Dak Hassan, "How very, very strange. But that makes your accomplishment all the more of a credit to you."

Daniels was watching him narrowly. "Just what accomplishment are you talking about?"

"Marrying the Bancroft money, of course. What else?"

"Marrying the Bancroft..." Daniels' voice trailed off, and his lips tightened.

Dak Hassan nodded amiably. "Yes. Of course."

Daniels started to get up. His fists were itching.

"Please," said Dak Hassan smoothly. "Engaging in fisticuffs is not only rude and undignified but in this case, quite unnecessary. We are in the same business, you and I."

Daniels stared at him. He still was sure he'd better not try to speak.

"Yes. Quite so. One must have money. If one is not lucky enough to be born with it and is not stupid enough to wish work for it, then one must marry it."

Daniels stood up. "I think I've heard enough." His tone was even and as full of menace as a red light.

"Please," said Dak Hassan pleasantly, "calm yourself."

Daniels reached for him and stopped with his hand an inch from Dak Hassan's pensively tailored shoulder. Dak Hassan hadn't made any noticeable movement, but he was holding a gun in his right hand.

He held it down low, out of sight of any of the passengers in front or in back of them. It was a .25-caliber Mauser automatic—a wicked, efficient-looking little gun. Dak Hassan held it though he knew how to use it.

"Please sit down," said Dak Hassan in a smooth, pleasant voice. "If one is of royal lineage, one must take precautions against being rudely handled. Please sit do down. If you attack me, I will shoot, I assure you of that."

He would shoot. Daniels knew it suddenly. Dak Hassan's eyes were as cold as greenish marbles, and his pupils looked like tiny, dead-black pinpoints. Daniels sat down slowly.

"Thank you," said Dak Hassan. He put the small automatic back into the inner pocket of his vest. His expression was as pleasant as ever. "You Americans are so sentimental about marriage, I have learned. One must take precautions when talking to the ordinary person, but I do not think it necessary in your case."

Daniels found a perverse humor in the situation all at once, and he grinned, faintly amused.

"Thank you," said Dak Hassan. "That is so much better. I am an admirer of yours. It would be most unfortunate if we should quarrel over a triviality."

Daniels nodded. "It would. So you're in the business of marrying money?"

"Oh, yes. Quite so."

"How are you doing?"

Dak Hassan shrugged. "Indifferently well at present. I shall do much better shortly."

"So?" Daniels said. "How?"

"I am going to marry Mrs. Gordon Gregory. You know her?"

"Faintly," said Daniels.

"She does not, unfortunately, have as much money as your father-in-law does, but she has enough, I think, to support me in a manner befitting my position." He spoke of it as if it was something he had skillfully run-up out of a few bits of wire.

"Oh, undoubtedly," said Daniels. "Does she know you're going to marry her?"

"She is not, as yet, irresistibly convinced of that fact. But she soon will be, I assure you."

"I see."

"And then, there is my title, of course."

"Certainly," said Daniels. "Your title."

"She will marry me," Dak Hassan said with quiet confidence. "I do not anticipate any great difficulties, although at the moment she is trying to elude me under the mistaken impression that if I am not near her she will be able to forget me." He paused, quietly amused. "No woman can forget Prince Dak Hassan."

"I don't doubt it," Daniels commented.

"Thank you. I am following her now to persuade her of that obvious fact."

"Following her?" Daniels repeated.

"Yes. She is going to Phantom Lake. So am I."

"Oh," said Daniels. "You, too." His mental radio tuned on again on that grinding refrain.

Dak Hassan raised his eye-brows. "Why do you speak in that tone?"

"My wife is there."

Dak Hassan spread his hands. "I understand. You are apprehensive because I might displace you in her affections? Have no fear. When one is a gentleman, one does not poach on another's preserves."

"That relieves my mind."

"It is nothing, my friend. If one cannot trust a prince of royal lineage, whom can one trust?"

"I sometimes wonder," Daniels said. "I'm a little hungry. Will you join me at dinner?"

"Indeed, yes! It will be a very great pleasure. You will pay for it, of course?"

"Oh, of course," said Daniels.

IT WAS morning, and the sun was warm and incredibly bright when Daniels got out of his taxi at the intersection and paid off the driver. He waited at the corner until the signal clanged and then burred comfortably to itself, changing its mechanical arms from "Go" to "Stop". Then he walked across the street and down.

His overcoat was hot and thick over his arm, and the handles of his heavy suitcase were wet and sweaty in his palm. The sun pierced the back of his suit and made an uncomfortably warm spot between his shoulder-blades. Several pedestrians glanced curiously and knowingly at the overcoat as he walked along.

He turned in a lot between two buildings, walked under a sign that said: Cars for Rent—U-Drive, in enormous red block letters. A board shack stood on the corner of the lot, and there was a fat man sitting on an old auto seat in front of it, lounging back comfortably and smoking a big, black cigar.

"Howdy," he greeted, moving the cigar so he could talk around it. He sized up Daniels' suit and overcoat and grinned. "Just come in from the East?"

"Yes," Daniels admitted.

"You're smart, comin' here," the fat man informed him enthusiastically. "Ain't this the most marvelous country you ever laid eyes on? Take a look across the street. You see that lawn over there? It's green, ain't it? You see that tree in front? It's green, too. And feel that sun!" If be had been directly responsible for the climate he could not have been smugger.

"I am feeling it," Daniels said.

"It's wonderful! And this is in the dead of winter, mind you! Why, I was just readin' in the paper that they're havin' a blizzard back East! Can you imagine that? Think of them saps back there diggin' out of the snow, freezin' their ears and gettin' chilblains, and here I sit without even a coat on! And, look! You see that tree down on the corner? That's a palm tree. A real, live palm tree! I bet you never seen one of them before, did you?"

"Yes," said Daniels, wondering if the palm tree were some relation of the fat man's.

"Where?" the fat man demanded skeptically.

"In California. I went to college here.'

"You did? Where?"

"Stanford."

The fat man thought a minute. "Stanford. Oh, yeah. That's the school up north we always beat at football. You shoulda gone down here. We got lots better colleges down here."

"I'll remember that next time." Daniel told him.

"Yeah," said the fat man. "Stanford's in northern California and that's just sort of the hind-end of California. That part of the state don't amount to much."

"What do the people in northern California think about that?"

The fat man shrugged. "Them? Who cares? They're crazy or they wouldn't live there. Take San Francisco—that's an awful place. They got nothing but fog there—day and night, winter and summer. It's terrible!"

"Ever been there?" Daniels asked.

"No! And I ain't goin' there, neither You want to buy you a nice second-hand car, mister? That's the thing to do. Then you can drive around and see the scenery. Why, you can go down south of here a few miles and pick ripe oranges right off the trees, right now, and..."

"I don't want to buy a car. I want to rent one."

"Oh," said the fat man. "For how long?"

"About a week."

"Okay. Where you goin'?"

"Up above Phantom Lake."

The fat man pursed his lips and shook his head. "You don't wanta go up there. It's 'way up in the mountains. It's cold up there, mister. You can see the snow on top from here." The fat man had obviously been delegated by a resourceful providence to keep Jim from folly.

"I still want to go there."

"Okay," said the fat man resignedly. "Okay. But are you sure you can get through? It snowed up there last night."

"Yes. I called up. They said the roads were passable,"

"Ummm," said the fat man. "Well, I'll tell you now, mister. We got the best roads in the world out here, and we got the best highway service, too, but sometimes the boys get a little optimistic. When they say passable they might mean the roads are passable if you got a snow plow with you."

"I'll take a chance."

"Okay. Damn, now I got to find you some chains. You'll need 'em up there. I don't know whether I got any or not. They don't equip cars with 'em in this country any more. Never need 'em. Wait while I look."

THE road had been climbing for hours—climbing

in long, gracefully banked curves that went on

endlessly upward. Daniels' hired sedan burbled and

grunted and knocked protestingly, and his arms were

beginning to ache from constantly turning the steering

wheel back and forth, back and forth.

The air was colder, much colder, and it had a heady, winy tang to it. It was light and thin and clear, and Daniels could feel his heart pumping harder to make up for its loss in oxygen content. The vegetation along the roadside was dark and resentfully shrunken with frostbite.

Occasionally, as the road turned majestically back and forth, he could catch a glimpse of the valley, miles away now and down thousands of feet below, like a green-and-brown checkerboard. Nearer him, there were brown, dirty half-melted rolls of snow high on the canyon sides. Rocks were cold gray lumps sticking out of the sparse earth.

The red ball of the sun slipped down behind the mountains ahead and night dropped on him noiselessly, like the swift descent of a black curtain. Daniels switched on the lights. The road kept climbing steadily. It turned around once far enough for him to get a glimpse of the valley again. It was still day down there, bright and warm with sunlight, and then the road went away from it finally and the mountains gathered closer, cold and awesomely lonely.

The snow gathered more thickly along the roadside, glinting back icily bright from the headlights, pinching in on the edges of the road, narrowing it.

Daniels saw a service station and headed in beside the brightly painted pumps. The attendant came trotting out, his breath making a long steamy plume under the lights.

"Hi! Gettin' kind of cold, eh?"

Daniels nodded. "Pretty cold. Fill it up, will you?"

"Sure. Going up much higher?"

"Up back of Phantom Lake."

"That's topside. You'll run into plenty snow. We got a lot of it last night. If you've got chains, you'd better put 'em on here. You'll need 'em a mile or so up."

"Are the roads clear?" Daniels asked.

"I think so. The boys been workin' on 'em all day. They should be about through by now. They'll be on control when you get up high."

"On control?" Daniels questioned.

"Yeah. They only let cars go through one way at a time. No room to pass. You may have to wait for a while if anybody's comin' the other way. They'll signal you."

Daniels put the chains on with the attendant's help, thanked him and paid him, and drove on up the endless grade. The chains beat noisily on the fenders for a while and then the snow crept across the surface of the road and muffled their clatter. The headlights glinted in brilliant reflections from snow-burdened brush and stubby trees.

Daniels had lost all track of the time, hypnotized by the steady, labored drone of the motor, when he saw the jerking swing of an electric lantern ahead of him. He slowed up and stopped beside the man who held it.

The man came around to the side window, beating his arms across his chest to stir his circulation. He was stocky and short and young with a cheerfully red, wind-bitten face. He wore a thick blue stocking cap and a sheep-skin jacket.

"Hi, mister. Goin' up much further?"

"I'm going up to Blair Wiles' lodge."

The man nodded. "You can get through that far all right. The boys with the plow are on up above a ways. Do you know where Wiles' place is?"

"No. Never been there."

"It's about two miles on up from here. You'll see his sign on the right side of the road. Turn off there. Don't park on this road."

"Can I get through?"

"Yeah. Wiles' chauffeur was down today, and he told me he'd shoveled a way through to the garage. You can get that far. The garage is about two hundred yards above the road. Wiles' lodge is about a mile up from there. You'll have to walk. There's a path, and be careful you don't get off it. The drifts are too deep for a man to get through without skis or snow-shoes, and it's going to snow some more tonight. Better hurry along."

"Thanks," Daniels said.

HE DROVE on. The snow plow had been at work on the

drifts here, and the road ran along like a narrow,

curving trench with glistening white side-walls. The

grade was steeper and not so well constructed. The

sedan thumped and chugged along laboriously.

Daniels found the sign—an artistically jagged board with the word WILES printed on it in red block letters. There was a break in the drift beside it, and Daniels turned in. Tires had chewed their way through the flat, unbroken surface of the snow, and Daniels steered along their tracks. Branches whipped coldly along the fenders, and the car rocked crazily over bumps, groaning in every joint.

The tire tracks went up a steep hump, angling slightly sideways for purchase, and Daniels' sedan quit halfway up with a final tired groan. Daniels got it into low, raced the motor, kicked out the clutch suddenly. The car edged forward, skidding slightly, made it up over the hump with a triumphant, exhausted sputter.

There was a small, cleared space here with the dark outline of a building almost covered with snow at the far side. Daniels judged that this was the garage, and he drove up against one of the doors and got out of the car. He took a long, deep breath of relief and then opened the hood of the car, intending to drain the water out of the radiator.

He was groping down into the engine, looking for the petcock, when some slight movement caught his eye. He straightened up, startled.

There was a man couched under the dark shadow of the eaves of the garage. Daniels could see only the small dim blur of his figure, and the steely glint of some object he was holding out straight in his right, hand, pointing it at Daniels.

His voice came thin and raw, shakily desperate: "Put your hands up! Quick! I'll shoot!"

Daniels stiffened and raised his hands slowly above his head.

"Stand still, now! Don't you move!"

Daniels said: "It's Pete Carson, isn't it?"

The metallic object jerked in the man's hand. "Huh? How'd you know? Who're you?"

"My name is Daniels. I sat across the aisle from you on the train the night before last. Can I put my hands down, Pete? I haven't got a gun, and I'm not going to hurt you."

"Yeah. But don't you try any tricks! I'll shoot!"

"Shoot?" Daniels questioned gently. "What with, Pete? That wrench you're pointing at me?"

Pete's breath caught in a taut sob. "Don't you come for me! I'll sling it at you! I-I will!"

"I'm not going to come for you," Daniels assured him. "I want to help you, Pete, if I can. How did you get away from Biggers?"

"He went to sleep, and I jumped out of the car and run. He didn't have the handcuffs on me. I hitched a ride on a truck and got up here."

"How did you and Biggers get to California so quickly?"

"Biggers, his nephew flies a plane—does skywriting and orchard-spraying and stuff. He was waitin' for us in Reno, and he flew us in."

"I see. Come here, Pete. I won't hurt you."

Pete came closer, step by step, warily. His face was pinched, dead, paper-white by the cold, and he was shivering under his thin overcoat in spasmodic, uncontrollable jerks. His eyes were wild and dilated with panic.

Daniels watched him carefully. "I've got some brandy in my suit-case."

He pulled the case out of the rear of the sedan, opened it with fingers that were stiff and clumsy inside his gloves. He found a hammered-silver flask and handed it to Pete. Pete opened it and took a long, gulping swallow. He doubled up, coughing in choked, rasping gasps.

"I ain't used—ain't used..."

Daniels rescued the flask. "I know. But it will make you feel better. Had anything to eat today?"

"N-no."

"I thought not. Listen, Pete. I'm an attorney, and I want to help you. Do you believe that?"

"Why?" Pete demanded suspiciously. "What do you wanta help me for? I ain't got no money to pay you."

"I don't want to be paid. All I want is to help you. Will you believe that, Pete? Will you trust me?"

Pete's mouth twisted in horrible uncertainty. "Well... yuh—yes. Yes! I will!"

"All right. I want to ask you one question. Biggers said you were accused of murdering your girl. Did you kill her, Pete? Look straight at me. Did you?"

"No! No, no! I never—"

"You swear that, Pete? Look at me."

"I swear. I swear I never touched—"

"I believe you." Daniels stood still, watching the white wreath of his breath, tense with his own thoughts. "Will you trust me now, Pete? Will you do what I tell you to?"

"What—what you gonna tell me?"

"To give yourself up."

"No! No, no! I won't! They're gonna put me in—in that place—gas—"

"Not if you're innocent."

"They will! They will! They got it all figured! They got my prints right in the room where she was! They know we had a fight that day! They found blood on my clothes! They will do it! They'll take me and they'll put me in that place where the gas—"

"They won't if you're innocent. Listen carefully, Pete. I've got about one hundred dollars in my wallet, and here's the keys to this car. If you were lying to me just now, if you really are guilty, I'll give you the money, and you can take the car and make a run for it. That's the best chance you'll ever get—if you're guilty. But if you take the offer, I won't help you any more. I'll be through with you. Take your choice, Pete."

Daniels took out his billfold and extended a flat packet of money and the car keys. Pete's breath rasped in his throat. He grabbed the money and the keys out of Daniels' hand, jumped for the car. He opened the door and stopped short, and stood tensely there, swaying a little. Then he slammed the door shut suddenly and sat down on the running-board. He put his head in his hands and started to cry with childish, shuddering sobs that racked his scrawny body.

Daniels sighed lengthily. The strain had been so breathtaking that he could feel the perspiration moist on his forehead in spite of the biting cold. He took the money and the keys out of Pete's lax fingers, pocketed them.

"Come on, Pete," he said gently. "We'll go up to Wiles' lodge and call the police. They're probably right on your trail. You couldn't have got up here without leaving traces they could follow. Why in the devil did you come clear up here?"

"I-I used to live—up here. I figured I could hole up in some lodge where nobody was livin'. Lots of people only come up in the summer."

Daniels shook his head slowly. "Pete, the police would think of that the first thing. They'd have dug you out in a day, and I'm willing to bet you wouldn't have gotten ten miles in my car without being picked up. You didn't have a chance."

"I-I didn't never have no chance."

Daniels' voice was hard and flat and determined. "But you're going to get one now. Come along, Pete."

THE lodge was a high, dark building, and it seemed to rise out of the white, misty blanket of the snow in reluctant little jerks as Daniels and Pete Carson walked up the twisting slope of the path toward it. There was a long porch on one side, the snow drifted almost level with its railings, and windows along the wall behind it. The drapes were pulled shut and light peeked out in sly, narrow slits.

Pete Carson stopped at the foot of the steps. He stood there, small and shivering and scared, his thin shoulders hunched, staring up at the dark bulk of the lodge.

"What's the matter, Pete?" Daniels asked.

"You—you won't..."

"I won't let you down. Come on."

Their feet squeaked coldly on the steps, thumped across the snow-laden boards to the front door. Daniels found an iron knocker and hammered it emphatically. The sound rolled away like a drumbeat in the silence.

There was no sound of footsteps inside, but the door swung suddenly back and shot bright light in their faces. The man who had opened it was tall and thin, stooped a little, and he was holding a big revolver in his right hand.

"Who're you?"

"My name is Daniels. James A. Daniels. I think my wife is staying here."

"Daniels!" the tall man exclaimed. "We didn't expect you! But come in! Come in!"

Daniels stepped through the door, and Pete Carson sidled through behind him.

The tall man slid the gun back in his pocket. "I'm Doctor Morris, Mr. Daniels. It's a pleasure to meet you. I've heard a great deal about you."

He had a narrow, long face with aquiline features. His eyes were grayish blue, wide-set and candidly intelligent, and his hair was a shining, burnished white, thick and straight. He had a gray mustache that made a penciled line above lips that were thin and flat and cynically twisted at the corners.

He went on: "Your wife has already retired. We were out skiing all day, and she got pretty fagged out. I imagine she's asleep. Shall I go up and tell her you're here?"

"Wait just one moment," Daniels requested. "I have to make a very urgent telephone call first. Have you a phone here?"

"Surely. In the other room. By the way, I'm sorry I greeted you by waving a gun in your face. There's a murderer loose up this way somewhere, and I didn't feel like taking any chances...."

Daniels nodded. "I know. Here he is."

Morris jumped back, clawing for the revolver. "What! You—he—"

"Don't be a fool," Daniels said coldly. "He happens to be my client. I brought him up here to surrender to the authorities."

Morris' thin face flushed slowly. "I'm very sorry, Mr. Daniels, for my display of nerves. I'm not used to being introduced to murderers in such a casual and unexpected way."

Daniels shrugged. "Pete is not a very desperate character. In the first place, he's not a murderer, and in the second place he's pretty hungry, cold and miserable right now. Is there a place here where he can be a little more comfortable?"

"Certainly. This way."

They followed him through a wide door into an enormously high, long room that ran the whole length of the lodge on the south side. A fireplace filled the whole wall at the far end. There was a log all of ten feet long burning in it now, crawling with bluish, hungry flames. That was the only light in the room, and the shadows wheeled deep and soft and dark in the corners and among the long, polished beams against the ceiling.

A man sat stiffly immobile in a chair that faced the fire. His back was turned, and the edge of a heavy white blanket draped over one of his rigid shoulders. He didn't make any move to look toward them.

Morris jerked his head to Daniels, walked over beside the chair.

"Blair, this is Mr. Daniels—Cora Sue's husband. He has arrived unexpectedly with a guest who is temporarily a fugitive from justice. Mr. Daniels—this is Blair Wiles."

The man didn't turn his head. He turned his whole body, inching it stiffly around in the chair until he could face Daniels. He was almost completely covered with the blanket, and his body below his shoulders was gross and heavy, limp with a loose lifelessness. His face was a horribly criss-crossed mass of scars—reddened, ugly, deep scars that pocketed the shadows from the fireplace and moved them like groping black fingers across his mutilated features. He wore a black patch over one eye, and the other one was a dilated reddish-white ball set deep in scar-tissue. His voice came thick and harsh, straining at the chords in his throat.

"How do you do, Mr. Daniels. It is a surprise to see you here. I understand from your wife that your business affairs were too pressing to allow you to leave. I heard the words 'murderer' and 'client' used in your conversation with Doctor Morris. Were you referring to Pete Carson?"

"Yes."

"He is here with you?"

"Yes."

"Are you in the habit of bringing murderous clients with you when you make social visits?"

"If I choose," Daniels said flatly. "If you wish, we will leave at once."

Wiles' one reddened eye watched him, unblinking. His gross body was unstirring and lax under the blanket. Daniels stared straight back at him, coldly, and the silence grew until it was like a heavy hand laid over the room.

Wiles said: "You are very quick to take offense, Mr. Daniels. And I am regretfully short-tempered due to certain—bodily defects that are no doubt obvious to you. I ask your pardon."

"Surely," Daniels said. "Pete, come up here close to the fire and get warm."

Pete edged up beside them. He stood there shivering in his inadequate overcoat, his hands pushed out timidly toward the flames. He looked pitifully like a stray cur, mangy and down-at-the-heels, cringingly ready for an unexpected blow from any quarter.

"You," said Blair Wiles. "Pete Carson."

Pete swallowed. "Yes, sir, Mr. Wiles."

"Why did you kill that girl, you fool?"

Daniels said shortly: "He didn't. And if you have any questions concerning the matter, address me. I'll answer you, if I see fit."

Wiles' lips moved in a grotesque travesty of a smile. "You are blunt, aren't you, Mr. Daniels? May I ask how you contacted your client? We had information just a short while ago that he was at large in the vicinity."

"I didn't contact him. He found me. He was looking for me. That's why he ran away from the officer who had him in custody. He wished to persuade me to take his case."

Pete stared, open-mouthed.

Morris chuckled. "You ought to prepare your client for those little surprises, Mr. Daniels."

Daniels turned around slowly and looked at him.

Morris held up one hand quickly. "No offense. That was a poor attempt at humor. We all seem to have got off on the wrong foot here. I'm sorry for my part in it."

"And I for mine," said Wiles. "You are my guest, Mr. Daniels. Please forgive me for being remiss in making you feel welcome. Morris, get some brandy."

Morris went over to a side-table and brought back a tray with a crystal decanter and glasses on it. Daniels poured some in a glass and handed it to Pete. He took another glass for himself. Morris started to turn away with the tray, and Wiles said:

"Give me some."

Morris smiled wryly. "Speaking as your doctor, Blair, you've had enough for tonight."

Wiles voice didn't change in the slightest. "Give me some brandy." Laboriously he brought one stiffened, scarred hand from under the blanket, extended it.

Morris shrugged and put one of the glasses in the hand. He poured some brandy in the glass.

"More," said Wiles.

Morris poured in some more with a resigned gesture. Wiles raised the glass toward Daniels and then tipped it up to his lips. He didn't bend his neck at all, and some of the brandy spilled out of the glass, ran down his chin. He wiped it off with his scarred hand. Daniels nodded and drank his brandy. Pete sputtered and coughed getting his down.

Morris came back from the side table and said: "By the way, Mr. Daniels, if you will look closely you will see another guest over on the couch in the corner. I neglected to introduce you before because he is not conscious at the moment."

The couch was draped in the shadows that crawled along tie polished walls. The man on it was enormously long and thin. His grotesquely oversize feet extended ever one end and hung there laxly, their long toes pointed at each other. He had thin sandy hair and a jutting beak of a nose. One skinny arm trailed down on the floor, and his mouth was wide open.

"Mr. Foley," Morris said. "His wife is around the premises somewhere, too. They are an interesting pair. Every time they go out together they have a race to see who can pass out the quicker. I think Mr. Foley won tonight's contest by about five minutes. He is the source of our information about Pete Carson. Incredible as it may seem, he is an honorary deputy-sheriff, and the authorities called him to tell him to be on the lookout for the fugitive. He lives three or four miles further over toward the lake, and his servants called here to relay the information."

Daniels nodded absently. He had heard a sound outside, and he had turned his head slightly now, listening with an intent expression on his face. He heard the sound again—a faint, distant shout.

"Pete," he said. "Come here."

He walked over to the couch, picked Foley up by his gaunt shoulders and shook him violently.

"Wake up! Come on! Wake up!"

"Blub!" said Foley, choking. "Huh? Wha'?"

"Wake up!" Daniels shook him more violently.

Foley's eyes opened. They were wide and blue and glassy and had no more comprehension than the painted eyes of a wax store-dummy. But his voice, surprisingly enough, was clear and quite precise.

"How do you do, sir? Have I met you before and will you allow me to buy you a drink?"

"No!" Daniels said emphatically. "Listen. This is Pete Carson, my client. He is surrendering himself to your custody as an officer of the law here and now. Do you understand what I'm saying?"

"Most certainly," said Foley. "If I may say so, sir, your argument is logically precise, but I must insist that your conclusion will be necessarily false and misleading because your premise is founded on a fallacy. Will you let me buy you a drink?"

"No."

"Thank you," said Foley. "I will have one, too. Waiter, bring another bottle."

Daniels let go of his shoulders. Foley instantly flopped back in the couch and closed his eyes, apparently picking up his stupefied sleep at the exact point it had been interrupted.

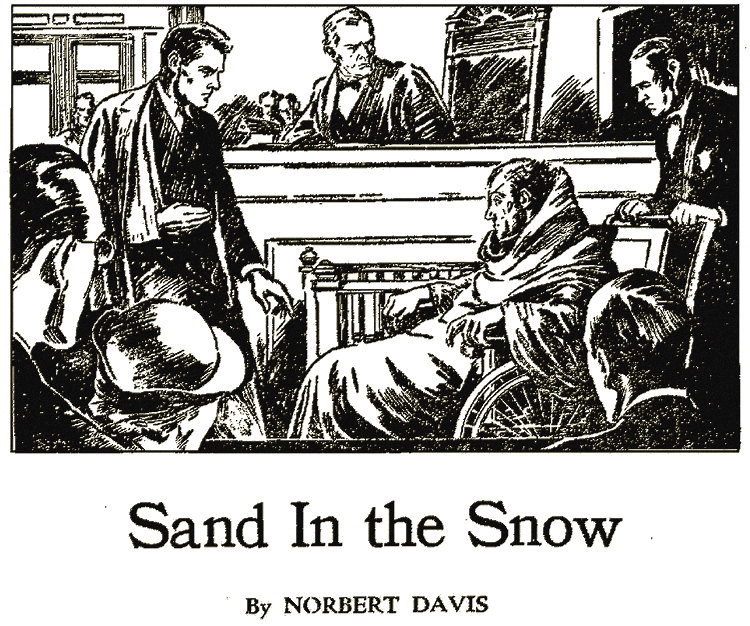

Daniels said: "Pete, sit down here beside him and stay there." He turned to look at Morris and Wiles. "You are witnesses that I have formally and voluntarily surrendered my client to a qualified officer of the law."

Morris was grinning. "Mr. Daniels, you are certainly a most resourceful man."

Daniels didn't pay any attention to him. He was listening again with taut concentration. Suddenly there was another shout from outside, much closer this time, and then the beat of footsteps on the porch. Something hammered violently on the outside door, and before any of them could move it opened with a resounding crash. A burly thick-shouldered man thrust into the room, holding a rifle ready across his hip.

"Hah!" he said in a triumphant bellow. "Got you, you little rat! Put up those hands!"

Daniels said: "One moment. Just who do you think you are?"

There was a vitriolic bite in his voice, and the burly man stared at him, taken back for a second. He wore a lumberjack coat of crimson and black plaid, corduroy trousers, and high boots. He had a hunting cap pulled down over his ears. His face was as red as the plaid on his jacket, and he had a drooping yellow mustache that partially concealed the thick-lipped looseness of his mouth.

He swung his rifle around. "That—that's Pete Carson! He's a murderer..."

"I'm very well aware of who he is. Who are you?"

"Why, Grimes. I'm the sheriff..."

"Can you prove it?" Daniels asked coldly.

Doctor Morris chuckled, wryly amused. "He's the sheriff, all right."

"I'll take your word for it," Daniels said. "Now, Grimes, what do you mean by acting in this manner? Are you aware of the fact that you have just committed two felonies—and very serious ones?"

Grimes' lax mouth opened. "Me? Two—felonies?"

"Yes. For one—assault with a deadly weapon."

"Me? Why, I never touched..."

"You don't have to touch anyone. An assault is an attempt—I said, attempt—coupled with the present ability to commit a violent injury on the person of another. If you assault anyone with a deadly weapon, it becomes a felony, and you're pointing that rifle at me right now."

Grimes jerked his rifle aside hastily. "I didn't mean..."

"Besides that, you're guilty of burglary."

"Burglary! I am not! You can't say I stole—"

"You evidently aren't very familiar with your own penal code. I'll quote you its definition of burglary: 'Every person who enters any house, room, apartment, tenement, shop, warehouse, store, mill, barn, stable, outhouse or other building, tent, vessel, railroad car, mine, or any underground portion thereof, with intent to commit grand or petty larceny or any felony is guilty of burglary.' You entered here with the intent to assault someone with that rifle, which is a felony, and the proof of that is that you did so assault me."

"It's a lie!" Grimes yelled. "You can't say that! I came in here to get Pete Carson, and I got a right to do it because I seen him through the window, and he's a fugitive—"

"He is not. He's at present in the custody of a properly qualified officer, to whom he surrendered voluntarily."

"Huh?" Grimes said, amazed. "Who?"

"Mr. Foley, there."

"Why, he's asleep!"

"There's no law in this state," Daniels said precisely, "that requires an officer to stay awake after he makes an arrest."

Grimes had recovered himself, and his red face slowly turned a rich purple. "Why, damn you! You can't talk to me that way! I'll show you—"

"Whoa-up!" Morris said quickly. "Don't get in over your head, Sheriff. This man is James A. Daniels. He's Carson's lawyer, and also he's A.J. Bancroft's son-in-law, and A.J. Bancroft has more cash assets than the United States' Treasury and a nasty disposition on top of it."

"Uh!" said Grimes, deflating rapidly.

Daniels looked at Morris. "When I want your help, I'll ask for it. I can take care of my clients without aid from you or A.J. Bancroft or anyone else."

"Sorry," said Morris.

Daniels nodded at Grimes. "You can take Pete away now. Be very careful. These gentlemen and myself are witnesses to the way he appears at present. I want to find him looking that well, or better, when I see him tomorrow. If I don't, I'll file charges against you."

Grimes swallowed. "Why—why, I wouldn't lay a hand on him, Mr. Daniels."

"Don't—if you want to go on being sheriff. Now get out. Take him along with you."

"Sure," said Grimes. "Come on, Pete." He took Pete's thin arm and led him toward the door. There he paused and looked back. "—I'm sorry I busted in on you..."

"Quite all right," said Blair Wiles in his thick voice. "Good-night, Sheriff."

GRIMES and Pete went out, and the outer door made a

hollow thud closing after them. Morris gave a little

whistle of awed admiration, staring at Daniels.

"You certainly swing a big stick. I'd hate to be on the witness stand with you cross-examining me. Were you really quoting from the penal code—that about burglary?"

Daniels nodded. "Yes. I went to law school in California, and I had occasion to memorize lots of the sections at one time or another. I have never forgotten them. I'm sorry to seem so abrupt with the sheriff, but I believe in impressing officers that my clients are to be treated with care and that I'm not fooling about it, either."

Morris chuckled. "You certainly impressed Grimes."

"And me," said Blair Wiles. "If I ever get into trouble, I shall certainly remember you, Mr. Daniels. I like the way you protect your clients."

Daniels said: "I believe in seeing that they get every protection the law allows them, That is my sworn duty as an attorney...."

"Jim."

It was Cora Sue. She was standing in the doorway that led into the hall. Her blond hair was tousled, and she looked like a sleepily indignant child. She was wearing a blue dressing gown and blue bedroom slippers with white fur on them.

Daniels went toward her quickly. "Cora Sue, honey!" He put his arms around her and held her close "I came as fast as I could to apologize, dear. I'm sorry for the way I talked to you. You were right. I did need a vacation—badly. Forgive me?"

Cora Sue pushed herself away. "I heard some shouting down here. It woke me up. I heard your voice, too. What were you doing?"

"Well, I..."

"He was protecting a client," Morris said, "and doing a darned good job of it, too."

"A client!" Cora Sue echoed. "Who?"

Daniels swallowed. "Well, Cora Sue, it's a man by the name of Pete Carson. I met him on the way out. He's accused of murder..."

"Murder!"

"Well, yes. He's not guilty, though."

"So," said Cora Sue. "You come out here for a vacation, and the first thing you do is get involved in a murder trial."

"But, Cora Sue, he's just a kid, and he's not getting the breaks. Honey, I couldn't stand seeing him get pushed around like he was just because he didn't have anyone to go to bat for him...."

He had started in a rush of words, but now, looking at her pale, set face, he paused uncertainly.

"Jim," said Cora Sue. "I'm mad. I'm good and mad at you. And I'm tired, too. I'm going back to bed. I'll talk this over with you tomorrow when I feel better."

She turned and marched back through the door, her slim, small shoulders held stubbornly erect. Daniels stood there forlornly and watched her go.

"Never mind," Morris said soothingly. "It happens in the best regulated of families, Mr. Daniels, I can assure you. Would you like another brandy?"

"Yes," Daniels said dully.

He walked across to the fireplace and stood there with the glass held in his hand, staring blankly at the windows. And then he was not staring blankly any more, because there were eyes staring straight back at him.

They were outside, behind the slick shine of the window-pane. They were narrow and malignantly steady. They were peering through the small space, like a thin inverted V, where the bottoms of the drapes didn't quite meet each other.

Daniels straightened up incredulously. He could see the rest of the face, besides the eyes, and there was something the matter with it. It was grotesquely swollen and shapeless, and it had no features at all. It was white.

Then Daniels suddenly realized why it looked that way. It was bandaged. It was completely covered with bandage, wound around and around it, until only its eyes were visible.

The white thing that should have been a

face peered in for a moment, then vanished.

The glass slipped out of Daniels' stiff fingers and shattered on the hearth. The bandaged face was gone, quicker than the flick of an eyelid, and the window-pane was shining and as blank as if there had never been anything behind it.

Blair Wiles had turned his stiff, unwieldy body to peer at Daniels, and Morris said:

"What's the matter?"

"There was someone—looking in that window..."

Daniels turned and gestured silently. With an effort he got hold of himself now; he was irritated that his voice should have been so hoarse and uncertain an instant before.

"Where?" Morris demanded incredulously. "I don't see—"

From upstairs, Cora Sue screamed. She screamed once and then again, in a rising crescendo of terror.

Daniels spun away from the fireplace, darted for the door. He was in the shadowed length of the hall, and at the back he saw the latticed pattern of a stairway. He went up the stairs four at a time, lunging with reckless haste. At the top there was another and longer hall running at right angles to the lower one.

Cora Sue was standing halfway down it in front of an open door. She was standing rigid, staring into the doorway, one hand pressed flat against her lips and the other out in front of her as though she were trying to push something namelessly horrible away from her.

Daniels caught her shoulders. "Cora Sue! Are you hurt?"

"No! No, no! Mrs. Gregory..."

It was the first time Daniels had known that Mrs. Gordon Gregory was already one of the guests at the lodge, and he turned around now and saw her in the bedroom beyond the doorway. She was lying across the bed, rigidly, on her back.

Daniels let go of Cora Sue and went into the bedroom step by step. Mrs. Gregory was wearing a pair of blue silk pajamas. The top had been ripped cleanly down from the V of the neck and thrown back. Her face was in the shadow, and her slim body looked startlingly like that of a young girl. Her breasts were small and high and firm, and there was a reddened, narrow slit in the white skin just below the left one. Blood had slipped down away from it and coagulated on the flat tautness of her stomach.

From the door, Morris said: "What—what—Oh!" He came in quickly and leaned over Mrs. Gregory. He looked at the wound and then took hold of one of her lax wrists. He let go of it instantly. "She's dead."

Daniels stood rigid for a second, and then he whirled and jumped for the door. Cora Sue caught at his arm, trying to stop him.

"Jim! Wait! Where—"

"Stay here!" Daniels shouted over his shoulder.