RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

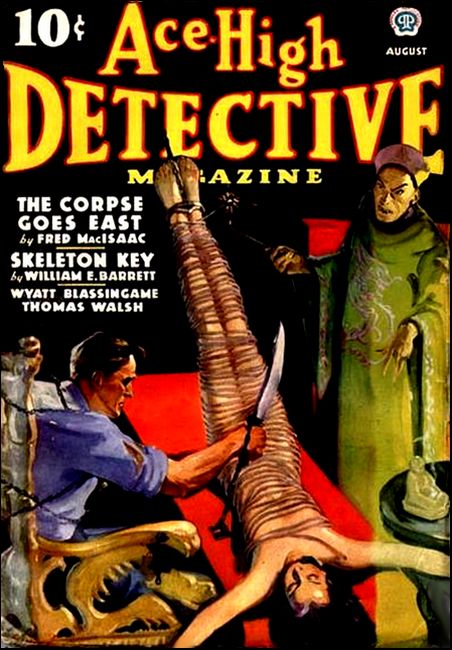

Ace-High Detective Magazine, August 1936,

with "The Upside-Down Man"

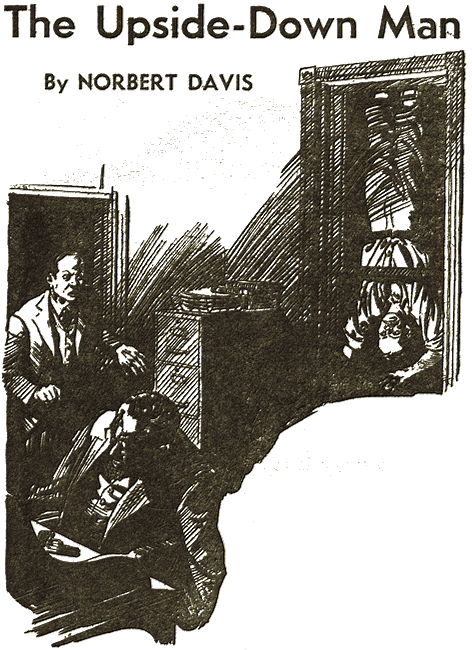

"He was hanging upside, down outside the window again."

Matt Flint's way of breaking up framed murder trials was to do a little framing of his own. But when he undertook to defend the thin, little man, Schrader, he had to go one step farther. And that step brought him face to face with a killer who struck—upside down.

HOWARD LEE ELLIOTT pushed the swinging-door open, and sunlight splashed hotly yellow on the damp coolness of the floor, climbed the bar in a yellow streak, reflected itself from the bar mirror in a thousand bright little glitters. Howard Lee Elliott let the door flap shut behind him and came across the room with his quick, firmly confident stride.

"Scotch and soda, please," he said in his flatly cultured, English voice.

"Yes, sir," Mike said, and ice rattled in his little tin scoop, tinkled coolly, pleasantly in a glass.

Elliott was a tall, blond young man with handsomely regular features. His teeth were a white, even streak against the deep tan of his face, when he smiled. He smiled now, watching his own reflection in the bar mirror, until he saw Flint watching the reflection, too. He stopped smiling, then, and turned his head with a little startled jerk.

Flint was standing about ten feet away, leaning against the bar and sipping thoughtfully at a big mug of beer.

Elliott stared very coldly at him for a space of ten dragging seconds, and then deliberately turned his back and moved farther away along the bar.

Mike saw him do it and stopped making the drink. "Come to think of it," he said, "I ain't got no Scotch."

"Rye will do," Elliott said absently.

"I ain't got no rye, neither," Mike said. "In fact, I ain't got anything you'd like to drink."

"What?" Elliott asked in a blankly amazed tone.

"The door," said Mike. "It's right over there. It opens and shuts real easy."

Elliott's handsome face went grayish white under the tan. "I see," he said tightly. He turned sharply on his heel, strode across to the door. He stopped there, looking back over his shoulder at Flint and Mike. "Birds of a feather," he said.

Mike picked a beer mug off the back counter, swung it back up over his shoulder.

"Don't!" Flint said sharply.

Mike put the beer mug very slowly down on the counter. Elliott laughed on a forced note. The door flapped open and shut, and he was gone.

"Thanks, Mike," Flint said. "But I've seen you throw a beer mug before. You'd have cut off his head as likely as not."

"Maybe not," said Mike, "but I'd of sure put a new part in that blond pompadour. I seen him. I seen what he did. Nobody pulls that stuff around here. When Matt Flint drinks at my bar, anybody that don't want to drink with him don't drink."

FLINT said, smiling in his darkly sardonic way: "He was

afraid I'd contaminate him." He was a thin man, bonily tall.

His features were all thin, hard, and his face seen from the

side gave the impression of blade-like sharpness. He was

slouching now, lazily and carelessly, but no matter what he

did he always looked the same—as if he had a tremendous

driving force inside him that he was keeping carefully

checked. "You forget, Mike, that I'm the black sheep of the

law profession in this tow. Of course, Elliott is a doctor,

but the Bar Association and the Medical Association are pretty

close, and I was kicked right out of the Bar Association on my

ear."

"Yeah," Mike said. "And that's the damnest, screwiest thing I ever heard of, and I've heard some funny ones in my time, too. Here's the only honest lawyer they ever had in their damned Association, and they toss him out."

"I violated the ethics of my profession," Flint said, smiling and sipping at his beer. "I bribed a juryman."

"Sure," said Mike. "Sure you did. And what for? To get a kid, that didn't have a dime, out of a murder rap. But that ain't the worst of it. The worst of it was that the kid was innocent all the time. That's the part I can't figure. You bribe a juryman to decide the case the right way, and for that they kick you out."

"That didn't make any difference," Flint said. "I was still guilty of bribing the juryman. The kid was innocent. I knew it. I never defended a man that wasn't innocent. I wouldn't take a man's case unless I knew he was innocent. But if he was innocent, and I did take his case, then I'd get him off. I'd always figure the guy was trusting me with his life, and if I wasn't smart enough to get him off, using legal means, then I'd use any that came to hand and take my chances."

"That's the kind of a lawyer I go for," Mike said.

Flint swirled the beer around in his mug. "That was a funny case, when you stop and think about it. It was right before election, and the district attorney was out to get a conviction. He jiggered the jury panel. No matter what twelve guys I picked out of the whole bunch of them, I'd have had twelve of the D.A.'s stooges on the jury. I went him one better. I fixed one of the stooges, and I picked the best one. He was smart enough to get the others to decide my way. But they nailed me on the deal. If the real murderer hadn't confessed about then, I'd be on the inside looking out. But the D.A. knew he couldn't get a conviction under the circumstances, so he just had me disbarred."

"In my opinion," Mike said, "the district attorney is a chiseling rat. I don't like him no better than that blond baby that was just in here."

"Elliott thinks pretty well of himself," Flint said.

"I don't like him," Mike said. "I don't like the way he looks. He always looks like he just bought his clothes yesterday and just had a shave and a haircut. And I don't like that way of talking he has, either."

"He can't help that. He was raised in Boston and graduated from Oxford. His folks are Society with a big S. He goes in strong for ethics and honor and breeding and family and whatnot."

Mike nodded knowingly. "Yeah. He don't mind dough, either, I bet. I bet he ain't gonna have to hold his nose when he grabs off Abe Rule's dirty millions and that niece of Abe's with the vegetable name."

"Letticia," Flint said. "Letticia Hartwell. She's a very pretty girl."

"Un-huh. The fact that old Abe just got himself murdered without no will and she's his only heir—that helps a little, too. Of course, everybody knows old Abe never seen an honest dollar in his life. Every dime he's got was picked up on graft paving and building jobs. But I bet that don't worry Society Elliott."

"I wonder," Flint said thoughtfully.

"Hah!" said Mike. "Anybody can stand a lot of stink for a million dollars. Take it from me."

FLINT saw her when he came out of Mike's place. She was

standing across the street in the spindling shadow of the

Criminal Courts Building. She was talking to Howard Lee

Elliott. She was looking up into his tanned, handsome face and

laughing at what he was saying to her.

She was very small, daintily neat. She had none of the craggy, grotesque ugliness that had made her uncle, Abe Rule, such an outstanding figure in any crowd. She had a delicate, heart-shaped face and full, soft lips. She was dressed very neatly and plainly now in tailored blue suit and a small blue turban. Flint had seen her in this neighborhood quite often. She did social-service work in the slum district, four blocks away.

As Flint watched her, she stopped looking up at Elliott's face, and the smile went away from her lips suddenly, leaving them twisted grotesquely. She was staring over Elliott's broad shoulder at something behind him.

She screamed, and the shrill sound of it cut through the street-and-traffic noise like the slice of a sharp knife. Elliott whirled around to look behind him.

Letticia Hartwell pointed her finger straight at a thin little man, twenty feet from her along the sidewalk, and screamed again.

"It's he! It's Harold Schrader! He murdered my uncle!"

The thin little man had stopped dead still at her scream. He was crouched close against the wall of the building, like some hunted animal. And now when Letticia Hartwell screamed his name, he put his hands up over his ears as if he were trying to shut out the sound. He turned and fan blindly, straight across the street toward Flint. Tires screeched, as drivers of two cars swerved both ways to avoid him.

A policeman swung around the corner at a dead run. He saw the running figure of the thin little man, saw Letticia Hartwell pointing at him and screaming. He stopped short in the middle or the sidewalk. The thin little man ran blindly, right straight toward him. The policeman waited until the thin little man started to pass him, and then put out his foot and tripped him up. The thin little man went down hard on the cement in an awkwardly tangled sprawl.

He started to scramble up, and the policeman swung his night-stick. The blow made a dull, whacking sound on the thin little man's head. He went down on his face again, and the policeman swung the night-stick up for another blow.

"That's enough," Flint said from behind him. He didn't raise his voice.

The policeman turned around and said, "Who the hell . . ." and then stopped when he saw who it was.

"Yes," said Flint softly.

"Well, he was resistin' arrest," the policeman said.

"He wasn't, and he isn't," Flint contradicted flatly.

The thin little man sat up on the sidewalk slowly. The night-stick had cut him a little over his right ear, and he put his hand up to his head and then stared dazedly down at the blood on his fingers. He looked around and saw the crowd pushing close to him, gaping curiously. Letticia Hartwell came up with Elliott close behind her.

"That's the man!" she said breathlessly. "He's Harold Schrader! The police are looking for him! He killed my uncle!"

The thin man sobbed suddenly. He put his face in his hands, and his narrow shoulders jerked spasmodically.

Elliott was pulling at Letticia Hartwell's arm nervously. "Let's get away now, dear," he said nervously. "They'll take care of everything. There's no real need . . . scene ... all these people. . . ."

"He ain't hurt none," the policeman said to Flint. "I didn't hit him hard."

"That's a very lucky thing," said Flint, "for both you and him. You can take him to jail. See that his head gets bandaged and that he gets a drink to brace him up. Put him in one of those new cells on the north side. You can tell anybody that gets curious about it that he's a very good friend of Matt Flint's, and that I'm going to come and see him in a half hour, and that I expect to find him in pretty good shape."

"Why sure, Matt," the policeman said. "Sure thing."

THE bars bothered Schrader. He tried not to look at them,

but every so often his washed-out, colorless eyes would stray

toward the door or window of the cell, and then he would blink

quickly and swallow hard. He couldn't have been very old,

but he looked old. He had the beaten-down appearance of a

meek, mild little man who has lived in constant fear of some

domineering character.

"Yes," he said. "Yes, thank you. They treated me very well. They kept asking me how good a friend of yours I was, and how I came to meet you. I—I didn't know what to say, so I didn't say anything."

"That's smart," Flint told him. He was sitting on the edge of the bunk. The shadow from one of the window-bars cut slantwise across his face and concealed some of the harshness of his mouth and jaw, emphasizing the kindness, sympathy in his eyes. "When you don't know what to say—don't."

Schrader said uncomfortably: "Who—who are you? I know your name, of course. But, I mean, the police were so respectful—"

FLINT smiled. "I'm not anybody, to tell the truth. Just a

disbarred lawyer. But I've got sort of a reputation around

this town. I'm supposed to be a very bad guy to cross, because

something unfortunate always seems to happen to people who do

it."

"I'm—I'm very, very grateful to you for helping me, but I don't have very much money saved. ..."

"And I can't take any fees—being disbarred. So we can go right ahead with free conscience. Why don't you tell me about it?"

"I'd be glad to. I—I really didn't kill Mr. Rule. I mean, that's a foolish thing to say here, isn't it? But I really didn't do it."

"I'm sure you didn't," Flint said. "Otherwise, I wouldn't be here."

Schrader stared at him incredulously. "You—you don't think I did it?"

"No."

Schrader gulped noisily. "Thank you. Thank you, Mr. Flint. I thought everybody—" He turned his head away and blinked rapidly.

"What were you doing down here this morning?" Flint asked.

"I came down to give myself up. I couldn't stand it any longer. It was foolish of me to run when Miss Letticia saw me, but I just couldn't help it. It seemed as if the whole world were screaming and pointing at me."

"Sure, I know," said Flint. "It gets you that way. Start from the first."

Schrader nodded. "I worked for Mr. Rule for the last five years, I was his secretary. He had quite extensive property holdings, houses and buildings that he rented. I took care of that and his correspondence. He could hardly read or write. I lived at his house."

"I get it," Flint said. "Go on from there."

"The night Mr. Rule was murdered, I had gone out to the motion pictures. It was the servants' night off, and Miss Letticia had gone out with Mr. Elliott. There was no one home but Mr. Rule. The house is a very large, old-fashioned one, and Mr. Rule's office is on the third floor. As I turned in the front walk when I came home from the pictures, I noticed the light was on in the office, and then I saw the crippled man, hanging upside down from the eaves right above the window."

"You saw what?" Flint asked.

"The crippled man, hanging upside down from the eaves."

Flint nodded. "Yes. I guess I heard you right the first time. Go on."

"It startled me terribly."

"I can understand that, too," Flint said.

"He was a small man, smaller than I am. He wore a steel brace that ran the whole length of his right leg. He was hanging there head down, looking in the top of the window of Mr. Rule's office. He didn't see me clear down on the ground, of course. Before I could shout or call out or do anything, he took hold of the top of the window—the windows have a broad sill both above and below them—let go of the eaves with his legs and swung himself right around in the air and in through the window. The bottom half was open. He did it so quickly and easily that—that it seemed incredible."

He still looked astonished.

Flint said: "I'll agree with you there all right. Incredible is the right word for it. Go on."

"I started to run toward the house, and just as I went up on the front porch I heard the shot. I was terribly frightened. I fumbled with my keys, getting the door unlocked. Then I ran up the stairs to Mr. Rule's office. The door was open, and he was sitting in his chair behind his desk. He had been shot through the head, and there was blood all over his face. There was a gun lying on the desk in front of him."

"And the crippled man?"

"He was hanging upside down outside the window again. Then, in a second, he twisted himself and climbed, somehow, onto the roof.

"I could hear him. I could hear him walking. It was terrible. I could hear that click-clock sound of his brace going across the roof. I'll—I'll never forget that sound. I wake up sometimes at night, and—and I can hear that click-clock sound coming toward me in the dark...."

"I know," said Flint. "I know. What happened then?"

Schrader shivered a little. "I—I didn't know what to do. I was so frightened I was numb and icy all over. I grabbed the revolver off the desk, and I followed that click-clock on the roof. I followed it clear across to the other side of the house. The rooms were all dark, and there wasn't any sound anywhere except the click-clock, click-clock on the roof above me. Finally, it stopped, and I just stood there below where it stopped, and I couldn't think of what to do."

"And then?" Flint asked gently.

"Then I ran. I ran out of the house and across the street, and I pounded on the door of a house and yelled that Mr. Rule had been murdered. A woman opened the door. She saw me there, and I still had the revolver in my hand, and she screamed at me: 'You killed him! You murdered him!' Then I dropped the revolver there and ran again. I could hear that voice screaming at me the whole time. I hid in an old abandoned shack Mr. Rule owned down on the edge of the marshland south of the city, until I couldn't stand being alone any longer, then I came to give myself up."

"Have you told anyone else this story?" Flint asked.

Schrader shook his head. "No."

"Don't," said Flint "Don't say anything about it to anyone, you understand? They won't bother you much. They think they have an open-and-shut case—and maybe they do."

FLINT pushed the slatted screen door open and went inside.

It was a small, square room with stained plaster-board

walls. There were two small round tables on each side of the

door, and directly across from it there was a short, scarred

counter. A few dusty bottles sat on the shelves behind the

counter.

The fat man was sitting in a specially braced and padded chair at the end of the counter. He had an abnormally big, pink face and very wide, round eyes that were a clear, bright blue. He nodded his gleaming bald head at Flint gravely and said: "Hello, Matt. If you'll reach over the counter, you'll find a glass on the shelf underneath." He indicated the jug beside his chair with a big smooth hand. "It's just old-fashioned dago red, but it's pretty good."

"No, thanks, Roxie," Flint said, pulling up a chair. "This is a business call."

"That's good," said Roxie. "I'm always open for business, even on a hot afternoon. Matt, do you think I'm a criminal?"

"I know you are," Flint said.

Roxie nodded amiably. "That's what I always figured myself, but I find I'm wrong. You know, I'm sending my cousin Tim's kid to college, and the other day I dropped around to see how he was coming along. I was reading a book he had, and it said that people like me were merely maladjusted cogs in the whirring machinery of our modern social and economic system and should not be penalized for their variations from normal behavior." Roxie fished a folded scrap of paper out of his shirt pocket and looked at it. "Yeah. Got it right that time. I've been memorizing it all morning. It's about time for Craigie to come around and hit me for a pay-off on my Pond Street bookie-joint. I'm going to try it on him."

"I don't think it'll do much good," Flint said.

"No," said Roxie sadly. "Politicians are uneducated people. But it sounds nice."

"Very nice," Flint agreed. "Roxie, I want to tell you a story."

"Go right ahead," Roxie invited. "I like stories."

"Suppose I told you that I saw a crippled man—a little fellow with a brace on his leg—doing nip-ups and hand-stands on the roof of a house in the dead of night? Hanging by his heels from the eaves and flipping in and out of windows and doing all kinds of stunts like that?"

"Why," Roxie said thoughtfully, "then I'd say that Clip Hansen had probably gotten tired of the sinkers and coffee they feed him down at the mission on Front Street and had been out cutting a caper."

Flint sat very still for several seconds, and then he said, "So," very softly, and began to smile in a quietly triumphant way. "Then there actually is a man who could and does do things like that?"

"Sure," Roxie said. "Clip Hansen used to be the daring young man on the flying trapeze. Traveled with a circus. He was a damned good acrobat, but he got sniffing the little white powders. He got a load on at the wrong time once, saw four trapeze rings where there were only two—and picked the wrong ones. He missed the net coming down, and he lit with his right leg doubled back under him. They never could fix it. He wears a steel brace on it."

"But he can still climb around on rooftops?"

"You bet," Roxie said. "The guy is really good in spite of that brace. I've seen him climb right up a smooth wall where you'd swear there wasn't a finger hold for an ant. He's hot stuff on a vine trellis. He's so light it don't take much to support him."

"He's still on the habit?"

"When he can get it. That's the only reason he ever does a job. Otherwise, he'd rather be just a bum. The cops have never tumbled to him. They just don't figure a guy with a bad leg being a second-story worker."

"I'd like to talk to him," Flint said.

"No quicker said than done," Roxie answered. He reached under the braced chair and pulled out a telephone, dialed rapidly. "This is Roxie, Joe," he said into the mouthpiece after a second. "Go find Clip Hansen and tell him to come over here right away." He hung up the receiver without waiting for an answer and put the telephone back under his chair. "It might take about a half hour before Joe's boys locate him."

"In that case," Flint said, "I'll have a try at some of that dago red and tell you all about this business."

FLINT heard the click-clocking noise that Schrader had

described to him. It was faint at first, like the ominous,

muffled tick of a hidden watch, and then it grew gradually

louder. It came up to Roxie's slatted screen door and stopped

on the outside.

"Come on in, Clip," Roxie said.

The door opened, and Clip Hansen came in. He walked very unevenly, bobbing—-taking a long step with his good leg, a short step with the crippled leg. He made the click sound when he put his weight on the braced leg, the clock sound when he lifted his weight from it. The brace was made of brightly gleaming steel, and it ran from a specially built-up shoe all the way up to his hip.

"Hello, Roxie," he said. He smiled and blinked his eyes very rapidly. "They said you wanted to see me."

"Yeah," Roxie said. "This is a friend of mine—Matt Flint. He's a lawyer."

"Was a lawyer," Flint corrected.

Roxie nodded. "Uh-huh. Get yourself a glass under the counter, Clip, and have a drink of wine."

"Thanks," Clip Hansen said. "Don't mind if I do." He found a glass and poured some of the red wine out of the jug. He was a very small man, stunted, wirily muscular. He had a thin face that was paper-white, and brown eyes that were set very close together and that he batted nervously whenever he looked straight at anyone. He wore a coat that was several sizes too large for him and had a big patch on one elbow. His black trousers were frayed badly around the cuffs.

"Sit down," Roxie invited. "Me and Matt here was talking about a new game I just invented."

Clip Hansen made a greedy little sucking noise sipping at his wine. "Game?" he repeated.

"Yeah. Hunting rats."

Clip Hansen blinked rapidly at him. "Huh?"

"Hunting rats," Roxie said. "There's a basement under this joint—down through that trap-door." He pointed to the far corner of the room. "It ain't very big, and it ain't got any other entrance or any windows. There's a sewer main runs through this block about twenty yards from this building. There's a pipe running into the cellar that connects with the main. I dunno why it's there, but rats come through it into my cellar from the sewer main. I rigged up a wire bottle neck and fitted it over the end of the pipe. They can get through it into the cellar, but they can't get back out again. I got eight of 'em down there now. There was nine, but the ninth was a little fellow, and the other eight chewed him up."

CLIP HANSEN put his wine down and pushed it away from him.

He made a little distasteful grimace and swallowed hard.

"Ever seen those sewer rats?" Roxie asked him. "They're big guys. About as big as a poodle."

"Yeah," Clip Hansen said. "Yeah. I seen 'em. The damn things give me the creeps. Them slimy tails—"

"They ain't so pleasant to look at," Roxie admitted. "But they sure make swell huntin'. I tell you how we do it. I got a night-stick here that I borrowed from Captain Regie of the racket-squad. You take the night-stick, and you go down in the cellar and close the trap-door. It's dark as the inside of a hat down there, and you can see the rats' eyes shine. You don't have to go after 'em—they'll come after you. They're hungry as hell. You watch their eyes, and when they come for you in the dark, then you swing at 'em with the night-stick."

Clip Hansen held the smile on his face, but the strained muscles jerked the corners of his mouth. "And—and if you miss?"

"That's bad," Roxie said. "The rat'll take a hunk out of you. They got teeth like needles. And if they get a sniff of blood, the whole bunch go nuts and come for you all at once. You just don't want to figure on missin'. Like to try it, Clip?"

"No," said Clip Hansen, and his thin shoulders twitched a little. "No, thanks. Did—did you wanta see me about something?"

FLINT waited. "Oh, yeah," Roxie said.

"I damn near forgot. Flint's got a job for you." Clip Hansen, blinking quickly at Flint, began to stir jerkily. "Job?" he said.

Flint nodded. "Yes. It's a tough one—probably the toughest you ever tackled. I want you to tell me the truth."

"Truth?" said Clip Hansen. "What d'you mean by that, huh?"

"I'd have a hard time explaining the idea to you," Flint said. "So we won't go into it. Just tell me why you killed Abe Rule."

The legs of Clip Hansen's chair scraped on the floor as he pushed backwards away from the table. "Huh? Say, what you tryin' to do? Say, what're you two guys pullin'—"

"Sit still, Clip," Roxie said gently. "Don't get all in an uproar, now. You're among friends. Just do like Flint says. Tell us why."

Clip Hansen's tongue flicked thinly over his lips. "You're jokin' me, huh?" he said, smiling nervously. "You're kiddin', huh? Abe Rule? I don't know nothin' about Abe Rule."

"Don't you remember swinging in his window the night he was murdered?" Flint asked softly.

"I never did! I never was there! What do you guys think—"

"The rats," said Roxie. "The rats in my cellar. They're pretty hungry, Clip. It's dark down there, and their eyes shine red."

Clip Hansen got up with a sudden click of his brace. "You—you can't—you don't dare—"

"Don't I?" Roxie asked. "You know better than that, Clip."

"Why did you kill Abe Rule?" Flint asked.

"I didn't!" Clip Hansen screamed at him. "You ain't gonna make—You ain't gonna put me down there with them—" His hand flipped under the looseness of his big coat.

Flint kicked his chair back, lunged over the table at him. He was too slow. In one incredibly quick motion Roxie came up out of his braced chair and smashed his big, smooth fist squarely into Clip Hansen's face.

The fist didn't travel more than twelve inches, but when it struck it made a sound like a sharp handclap. It knocked Clip Hansen up in the air, clear off his feet. Falling, he twisted his small body around and as he came dawn his head hit the edge of the counter at an angle.

There was a dull, snapping sound, and then Clip Hansen's brace made a clattering, metallic noise on the floor. A stubby little revolver slipped out of his lax fingers, skittered over toward the wall. Clip Hansen didn't move at all.

For a long moment, there was a tense, thick silence, and then Roxie's braced chair squeaked a little, protestingly, as he lowered his bulk back into it.

"Well," said Roxie. "Well, Clip sort of stepped out of his class that time. He must have been loaded up to the eyebrows, or he woulda known better. I don't let anybody pull a gun on me when they're standin' that close."

"He's dead," Flint said tightly. "That was his neck that snapped."

"He is, and it was," Roxie agreed.

"What are you going to do?"

"Nothing," said Roxie. "Just nothing at all, Matt. I figure it's up to you. I'm just a kibitzer in this game."

"I'll see that you're kept in the clear."

Roxie nodded calmly. "I know you will, Matt. That never worried me for a minute. But, come to think of it, I better do something, after all. Craigie is gonna be in here for his pay-off pretty soon, and if he sees any bodies lyin' around the premises, he'll want three times as much."

Roxie got out of his chair with that same smooth movement. He caught hold of Clip Hansen's big coat and dragged him effortlessly over to the trap-door. He opened it and pushed Clip Hansen through. There was a steely dash as the brace hit on concrete somewhere below. Roxie lowered the door again.

"Well, that makes my little story partly true," he said. "There weren't any rats in that cellar before, but there's one down there now."

THERE was a ship's model on the mantel. It was a large

one, a four-master, fully rigged, and it stood almost two

feet high. It seemed to fit in excellently with the rest of

the gloomy, high-ceilinged room with its clumsy old-fashioned

furniture and darkly figured wall-paper. It was a musty room

with an uncomfortable air of deadness and disuse about it.

Flint stood-dose to the mantel, examining the ship's model with thoughtful inattention. He was frowning a little, and there were gravely worried lines around his mouth and eyes. He turned around when Letticia Hartwell came into the room.

She looked very small and dainty, freshly modern, in strange contrast to the antique fustiness of the room. Her black hair was drawn smoothly back from the white oval of her face, and her lips were softly red, inviting.

"Mr. Flint?" she said. "I'm sorry to have kept you waiting so long."

"She kept you waiting until I could get here," Howard Lee Elliott said, coming in the room after her. "I understand that, for some strange reason, you've taken an interest in Harold Schrader. I warn you, Flint, that I won't stand for any of your usual methods in your treatment of Miss Hartwell."

"Usual methods?" Flint repeated blandly.

"I know you won't stop at anything," Elliott said. "There's nothing you won't do to get one of your clients free, but I'm here to protect Miss Hartwell, and I will."

"Who's going to protect you?" Flint asked.

Elliott flushed darkly under his tan. "You—"

"Please, Howard," Letticia Hartwell said wearily.

"I mean it," Flint said. "You need some protection. Now, may I speak to Miss Hartwell if I promise not to raise my voice above a whisper?"

"If she wishes," Elliott said stiffly.

Letticia Hartwell said: "Howard, you're being a little ridiculous. Go ahead, Mr. Flint."

"Thank you," Flint said. "I really don't have a great deal to say, but you may find it quite interesting. You see, I had two reasons for pushing myself into this business. For one—Mr. Elliott."

"Thank you very much," Elliott said heavily. "You can be sure I appreciate it."

"I hope you do," Flint said, "but I'm afraid you won't. The other reason was Harold Schrader. I was sorry for him— really sorry. He's a meek little fellow, hardly able to hold up his own end when things are going smoothly. And here he is in a situation that would be hard on the toughest—the whole world against him. He needed a friend, if ever I've seen a man who did."

"And so you elected yourself his champion," Elliott said sarcastically.

"Yes," Flint admitted. "He could have done worse."

"I scarcely see how," Elliott said. "But please go on with your story. It's very interesting."

"Harold Schrader told me his story," Flint said slowly. "He told me that when he was coming home the night Mr. Rule was murdered, he saw a crippled man, swinging from the eaves over Mr. Rule's office window, saw him get into the office. Schrader ran in the house, and then he heard the shot. When he got up to the office Mr. Rule was dead, and the revolver was lying on the desk in front of him. Schrader grabbed it, instinctively, and started to chase the sound the crippled man was making on the roof above. Schrader was scared silly, naturally enough, and when the scare really got hold of him he quit trying to catch the crippled man and ran out of the house. Some hysterical woman scared him even more, and he hid."

"That's the most insanely fantastic story I've ever heard!" Elliott said.

Flint nodded. "Yes. It is. But it's true. There was a crippled man on the roof, and I found him."

Elliott laughed contemptuously. "I don't believe—"

"You will," Flint said thinly. "Having no—ah—official standing, I have to use what methods I can find. I have arranged for some of my acquaintances to interview the crippled man. They're a little crude, but they get results with lighted matches applied judiciously."

"Torture!" Elliott exclaimed.

FLINT nodded. "Yes. It's the method for questioning

suspects that has more and older legal precedent than any

other. It's always been used since there was any law. The

crippled man will talk. I wonder what he'll say. What will he

say, Miss Hartwell?"

"You!" said Elliott, coming a step forward. "Don't you dare—"

"Wait, Howard," she said. She was staring at Flint levelly, unafraid, unexcited. But all the youth and freshness seemed to have washed out of her face and left it old suddenly, and weary. "You were playing with me, weren't you, Mr. Flint? The crippled man has already talked. You know what he said. He said that I hired him to come to the house that night."

"You hired—" Elliott said in a stunned voice. "You—"

"Yes," said Flint, speaking directly to Letticia Hartwell. "You hired him. You met him at one of the missions on Front Street where you do your social-service work."

"No!" Elliott said thickly. "No! Letticia—"

She raised her head a little, bravely. "Yes, I did. It's useless to explain now. It's useless to try to justify myself. I can never do that. But my uncle never loved me. He hated me. He hated my sister and my father. They were decent and clean and honest. They were both poor, but they would never touch a cent of his dirty money. They were both killed in an accident, when I was twelve. My uncle took me in, and he tried to spoil all the things they had taught me—all the decent and clean and honest things. I never got to see or know decent people. My uncle was a beast, and all his friends seemed the same—politicians, crooks, thieves, gangsters. I met Howard, and it seemed that he was everything I wanted out of life. . . ."

Elliott said: "Dear, please—" She went on quickly. "I didn't tell my uncle about Howard, but he found out, anyway. He had friends, everywhere. He told me he was going to spoil it for Howard and me. He said, the fool, that Howard was after his dirty money. That was too much. I struck back. I knew he had incriminating private papers in the safe in his office. I couldn't get to them. He had the door on a spring lock, and it was always locked when he wasn't in. I hired the crippled man to get in that safe—get some of those papers. I meant to threaten my uncle with them, if he interfered with Howard and me."

She looked straight at Flint. "It was an accident that night. I don't suppose the crippled man told you that, but it was. My uncle surprised him at his safe. They fought. ... I would never have let Harold Schrader suffer for it, Mr. Flint. Do you believe that? When he appeared today, I was desperate—I screamed. But I would never have seen him punished."

"I believe that," Flint said.

Elliott came toward her. "Dear, listen to me—"

She made a tired gesture. "No, Howard. That's what Mr. Flint meant when he said you needed protection. You needed protection from me. All this would have come out sooner or later, and you would have been ruined, disgraced. Your name and pride, your social position—place in your profession, your family all smashed—gone."

Elliott shook her. "Will you listen to me? Do you think I care for that? Do you think I blame you for what happened to your uncle? I know what kind of a man he was. Listen. Flint has no proof of any of this. Just the word of a confessed murderer. You could never in the world be convicted. Profession, family name, pride, social position—what do they matter? I'll have you—you! Well go away somewhere, where no one knows, start over together. . .

"Howard!" said Letticia Hartwell. "You would—do that—"

"Yes, he would," said Flint. "But would you?"

There was a thick, tense little silence while the two of them, standing close together, stared at him.

"You didn't let me finish," said Flint. "You forgot, Miss Hartwell, that Elliott often accompanied you on your slumming tours. Clip Hansen, the crippled man, had seen him, knew he was interested in you. Elliott had much more to offer Clip Hansen than you did, Miss Hartwell. Elliott is a doctor, and he could offer morphine. Clip Hansen was an addict. When you made your little proposition to him, Clip went around to see Elliott to see what he could see. Elliott approved of the plan but he introduced a little variation of his own. He offered a premium if Abe Rule didn't live through the robbery."

"That's a lie!" Elliott said savagely. "That's a dirty lie!"

"No," said Flint. "I searched Clip Hansen's room. On one of his visits he had picked up a hypodermic outfit from your office, when you weren't looking. It has your name engraved on it. You see, Miss Hartwell, your uncle wasn't much good in a lot of ways, but he'd had enough dealings with crooks to know one when he saw one, even if he did have an English accent and a degree from Oxford and a family name."

"You," Letticia Hartwell said to Elliott in a thin, soft voice. "You would have done that to me. You would have married me and let me think all my life that you had sacrificed yourself for me—spoiled your career because you loved—"

"I had to have money—I had to have it, I tell you!" Elliott was suddenly screaming, clawing at his collar. "I took funds at the hospital—"

"Yes," said Flint, "and all that will come out, too."

A SAGGING, lifeless kind of silence swelled out the room,

as Howard Lee Elliott reached automatically for his hat

on the table. After that outburst—that single,

torn-loose protest—all life seemed gone out of him. Now,

he walked slowly toward the door, almost as if a command from

Flint had ordered him there.

Then Flint felt the girl's presence at his side. Her eyes were slowly losing that expression of dull shock; and something more dangerous was in them, instead.

"You always get your clients off, don't you?"

He nodded. "Mostly—if they're innocent."

She said steadily: "No matter how. I've heard that about you, too."

Was she crazy enough to believe he'd try to get Elliott off?

"What I mean," the girl said measuredly, as if laying her words out, one by one, by thumb rule, "is this. I was supposed to see Clip Hansen this evening. To pay him for his work. And he told me he'd be here—if he was still alive." Her face was still drawn, but cold mischief danced in her eyes now. "That meeting was set for two hours ago. Something—must have happened to him."

"Yes," said Flint, hand on the knob. "Something did."

Seconds ticked off stumblingly; one, two, three—

Then her voice came closer. "I'm like you are. I believe in getting an innocent man off—no matter how. I'll keep your secret. Don't worry. I'll testify that I heard—heard his confession," and she indicated Elliott's stiff, sleepwalker-like figure.

Flint knew that his own methods were undoubtedly ruthless. Yet, beside her own, they faded away into nothingness.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.