RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

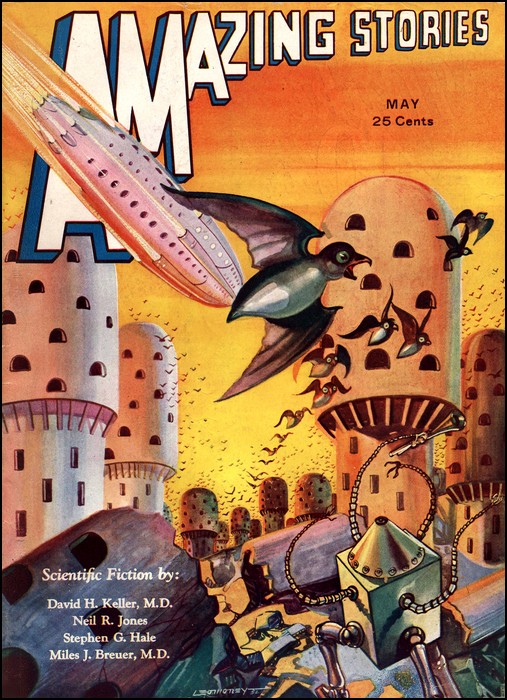

Amazing Stories, May 1932, with "The Perfect Planet"

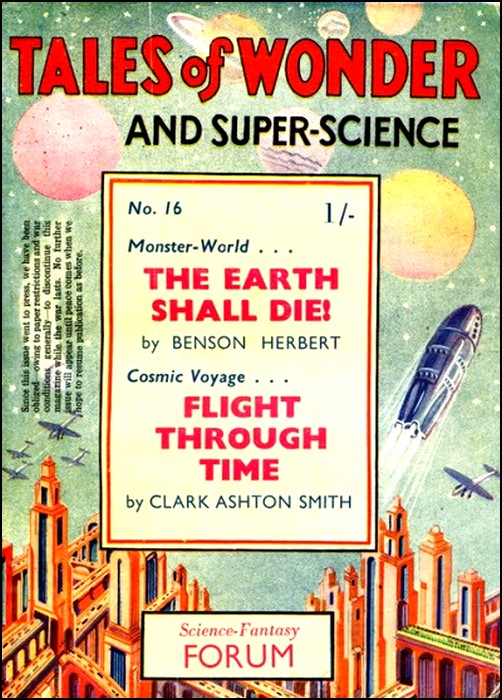

Tales of Wonder and Super-Science, Spring 1942,

with "Breath of Utopia"

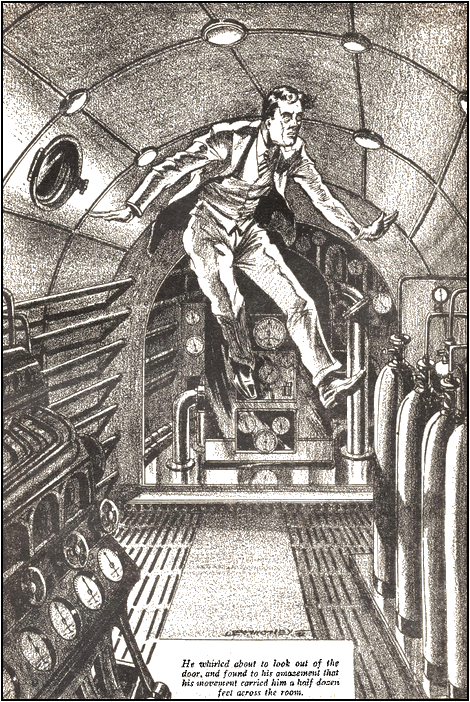

He whirled about the look through the door, and found to his amaze-

ment that his movement carried him half a dozen feet across the room.

WHAT is it that enables us to think clearly, or prevents us from seeing the obvious solutions to even ordinary, everyday problems? Isn't there some medicine or help for the muddle-headed individual, who means so well? Dr. Breuer thinks there is—and perhaps he is actually working on something himself, even if he does locate this "miracle-working something" on another planet.

"GUESS I'll look for the meteor," said Gus Kersenbrock out loud.

There was no one in those vast solitudes of sand-hill and sage-brush to hear his voice, but the arrival of that inspiring idea seemed to cheer him up. He lifted his head, and his drooping body became alert with interest.

He had been mooning along gloomily over the sand-hills for the greater part of the Sunday afternoon; for the sand-hills were his refuge when he was troubled and depressed, which the Lord only knows was often enough. Here among these wastes of sand, majestic as a frozen sea, he could think. That is what he had been trying to do now—in his halting and difficult fashion.

"Just because my head works too slow," he talked aloud, kicking at a tuft of gray sage, "that snob of a Thompson is taking my girl to the circus and I'm snooping around here like a coyote. Now, after it's too late, I can see what I'd ought to have said and done; nowadays you can't boss girls around by yellin' at 'em. I can't blame Kitty for going with a fellow that's got good manners and dresses swell and tries to please her all the time."

His feet crunched along through the sand. The low sun, shining orange-yellow through the dust pall, cast shadows of the low, rounded hills toward him.

"It don't seem right. Hard as I work, I can't more'n earn a bare living for myself, and have nothing left to offer to Kitty. A girl don't want a pauper. Thompson leads an easy life and has lots of money. Supposin' everybody knows he's a bootlegger; as long as he never gets caught he is more welcome at dances and parties than I am. And he comes by the garage in his swell clothes and sneers down at me when I'm under a car in my grimy overalls—I could throw a grease-rag in his pink face!"

About that time he conceived the idea of looking for the meteor. He stood on top of a rounded knoll of smooth, shining sand, somewhat higher than the others. He peered in all directions for signs of the meteor. But he saw nothing, except far in the distance behind him a tiny black dot where his Ford coupé stood. He had driven it as far as he could, until the road disappeared and the sand became too deep for driving. Everywhere else were unbroken, billowed wastes of sand.

"I suppose," he grumbled on, "after Forbes fires me for fumbling that transmission job and I'm sunk with nothing to live on, then I'll figure out how I could have fixed it."

At seven o'clock the previous evening he had flung down.his tools and left the shop in utter discouragement. He had been trying to repair the reverse gear of an old Model T Ford that would not work. All that afternoon he had toiled in the black grease, with gear-wheels and wrenches all about him.

"Who the hell can understand that?" he had exclaimed, and decided to spend his Sunday afternoon in solitude among the sand-hills, with his .22 rifle, some sandwiches, and a canteen of water.

The idea of searching for the meteor had struck him when the afternoon was all but over; but it lifted him somewhat out of his depression. Two weeks before, about four o'clock in the afternoon, all of the little town of Chadron had been startled by a flash of green light that was bright even in the afternoon sunshine, and by a dull, thunderous reverberation. It seemed to be almost on top of them, at the very edge of town at least. But every inhabitant of the village had joined in a minute search of the ground for miles around, and not a trace of the fallen star had been found; finally it had drifted out of their memories. Of all of them, Gus alone recollected it, when on this Sunday afternoon he found himself headed right in the direction of the place where it had been seen to fall.

Gradually his despair mellowed into a sort of peaceful melancholy; his dumb anger against Thompson subsided, and in its place came a stirring sort of glow of kinship with this spreading grandeur about him. Gus Kersenbrock was not outstanding for mental brilliance, but he did have a poetic sort of soul; he loved the wastes of sand and the riots of sunset color. Even the thin, gray coyote outlined for a second on the crest of a distant hill, seemed like a brother and a companion in the wilderness.

Then he saw the Ball!

He had just trudged up to the brow of a rounded hill, and saw it down in the valley ahead. It was huge, round, and greenish. It lay partly buried at the end of a vast furrow in the sand, that looked as though a Brobdignagian had dragged his gigantic boot there. The Ball did not look like anything he had ever heard of, seen, or imagined.

Afterwards he had always called it "The Ball," because of his first impression of it from a distance, sunk in the sand, with heaps of sand thrown up about one side of it. But as he came close, he made out that it was shaped like an olive, rather longer in proportion to its transverse diameter, and somewhat lighter in color; but taken altogether, looking very much like a huge olive. Arriving all out of breath under the bulging lee of the thing, he touched it with his hand. It was smooth and felt like glass; and he thought he could see a little distance into its translucent substance. He walked around it, and suddenly perceived that it had a door, swinging open.

For the first time it struck Gus that the ovoid was not some inorganic product of natural forces. To come to think of it, it could not possibly be a fallen meteor; those usually splash an immense hole in the ground, throwing up a circular mound of earth in crater form. This thing, if it came from above, must have landed with reasonable care and gentleness. Tales of Zeppelins bootlegging liquor from Canada to St. Louis entered his mind. He wondered if it would be best for him to wait for darkness and quietly steal away.

The door was heavy and countersunk, like a safe door. There were three other circular openings in different parts of the ball, covered with glass or some transparent stuff. For half an hour he lay there watching and listening intently; but not a sound, not a movement, not a glimmer came from within. That gave him courage to approach it again.

Then he got an idea, simple and cunning rather than brilliant. He tossed a pebble into the open door and scuttled into hiding. He heard it clink on a metal floor, but not a sound answered it. After waiting another fifteen minutes he was reasonably sure that there was no one about the apparatus. He walked up to the open door and thrust his head inside.

The light streamed in through the open door and through the three circular windows. Vague shapes of machinery stood about. The interior was a single compartment corresponding in general shape to that of the exterior of the huge ovoid. He waited until his eyes became accustomed to the subdued light within. Nowhere was there a sign of a living thing. He climbed inside.

He found himself in front of a table on which there were knobs and handles and dials and scales. He concluded that it was some sort of a control board. He stood in front of it with his hands clasped behind him, refraining carefully from touching it, because his primitive caution warned him to let it alone. Then he sauntered about inside the place trying to understand what it was all about. From the shape and size of the interior he could see that this room occupied all of the space within the vessel. Yet, there were no cases of liquor to be seen. In fact there was nothing of a familiar nature. He could not say what it was that he expected to find, but we can guess: papers, books, canned food, furniture, a hat or a coat. There was nothing that he could recognize, and a vast amount that he could not; a vast amount that seemed utterly strange and bizarre to him.

THE machinery seemed more familiar to him than the other objects. He was a mechanic, and in a simple fashion a very good one. Though their forms seemed utterly strange, he could guess the uses and purposes of some of the mechanisms. At one end were coils and vacuum-tubes that must have belonged to the high-frequency electrical field. Nearly opposite the door were many metal cylinders in rows, with valves at the tops, which reminded him forcibly of the drums in which they received their supplies of acetylene and oxygen for welding in the garage where he worked. He recognized a small electric dynamo-generator and the light-bulbs and heating devices Which it operated, though the things were of the most odd and unearthly shapes.

He was conscious of a curious sensation from the moment he had stepped into the interior, and in the back of his mind he was trying to define it; a sort of feeling of ease and power and lightness. A mournful howl suddenly splitting the air outdoors startled him for an instant; he whirled about to look out of the door, and found to his amazement that his movement carried him a half dozen feet vertically up into the air and a dozen feet across the room. Then he floated down gently to the floor. Two things were going on in his mind at the same time: he decided that the noise outside was a coyote and not the owner of the vessel, and he was forced to conclude, strange as it might seem, that the force of gravity was decreased within the vessel. It was many days before the corollary of the latter conclusion dawned upon him: that he was inside an interplanetary flier, and that gravitation was decreased to suit the convenience of beings from a planet smaller than ours. At the moment he still struggled with the idea that it was some sort of an illegitimate conveyance for smuggling or bootlegging.

He was roused from his puzzled thoughts by a sizzling sound and a queer odor. He found that he had descended gently on the tops of the metal flasks with stopcocks, and that to regain his balance he had seized one of the valve-levers. He must have released some of the gas in the containers, for it was sizzling out and filling the room with an utterly strange odor, very penetrating and somewhat aromatic. It reminded him distantly of crab-apple blossoms. Instinctively he grasped the lever again, and trying it this way and that, eventually, after several anxious minutes, stopped the sizzling. He went to the door, trying to ascertain if he had any ill effects from having inhaled the gas. He could feel no change; everything seemed as usual. What such large quantities of stored gas could possibly be for, he could not imagine. Frightened into better caution by his first slip, he examined the place thoroughly, until forced to desist by the gathering twilight. He started homeward, as much puzzled as ever; marking in his mind carefully the location of the Ball, with the intention of visiting it again. He went home in a considerably improved mood. He had had an adventure, and adventures were scarce for auto-mechanics in the sandhill country.

MONDAY morning, as he started for his job at the garage, he was still worried about the Ford reverse gear, and the fear of tackling it again made his steps lag.

"Being scared is just a feeling," he said to himself. "My feelings aren't going to run me as long as I've still got a perfectly good noodle. So here goes!"

He was amazed because he was thus able to see it as he had never seen it before; and he was amazed to find that the mechanism of the Ford transmission when he tackled it, was perfectly clear to him. Without any trouble, he could picture the large internal gear with the small one revolving backwards within it. It was more like a pleasant game than a difficult job to take the mechanism and systematically put it through its movements one by one, testing each function until he came to the lost set-screw on the inner shaft. He felt exhilarated after he had got the thing together working perfectly, and looked around for another job.

Gus was again amazed at himself when that forenoon his employer, Forbes, started a foolish wrangle with a customer, a tourist in a Cadillac. Gus had always been rather afraid of Forbes, and had a vast respect for the latter's ability to sign checks to the Skelly Oil Co., for two hundred and forty dollars every month. But it certainly showed lack of judgment on Forbes' part to argue with the man with an Ohio license-plate about the virtues of the sandhill country. If the Ohio man insisted that this was a God-forsaken place and a hell of a hole, Abe Forbes should have nodded, thanked him for his purchase, and asked him pleasantly to come again. How plain it looked now! Yet Gus had never noticed it before, even though it was happening constantly. So he hurried up, filled the tourist's radiator with water, polished his windshield, and told him how to find the better of the two roads to Alliance,

"Thank you! Come again!" shouted Gus pleasantly as the tourist drove off grumbling. Like a light breaking across a foggy sky, it dawned on Gus that Abe Forbes was driving half the good business to Alliance by his habits of arguing with customers about non-essential trifles.

Early in the afternoon it became vividly apparent to Gus that the front of the garage was disorderly and dirty. "Good business won't come to a junk pile," he thought, and set about putting things into attractive shape. By evening he had in mind a half dozen things about the business that were being done wrong, in a muddled, stupid fashion, and was planning remedies. He was amazed that such obvious things had been allowed to go so long without being recognized. "We've been blind. Blind as bats!" he thought. He was full of the exhilaration of plans for revolutionizing the business of the garage.

THEN came evening and with it, thoughts of Kitty. He called her on the telephone. "How are you, Kitty?" he asked in a jolly tone, that surprised her so that she nearly dropped the receiver. "I'm mighty anxious to get a look at you. Can you do my eyes a favor tonight?"

"Why—oh—why—oh, yes!"

Kitty was embarrassed because she had already promised Thompson a date. But she was so astonished at the expression in Gus' voice that she wanted to see what had happened to the boy.

The only thing that had happened to Gus was that now he could see. He could understand how Kitty felt about things. He couldn't blame her for getting impatient with an unkempt, blundering mechanic. So, he telephoned to Chadron's little florist shop, and then got to work to clean himself up and set out his neatest clothes, in the meanwhile keeping his mind busy thinking up pretty speeches for Kitty.

"Oh, Gus!" she exclaimed when she saw him and the extended bunch of flowers.

She could not think of another word to say, but right there, Thompson fell a thousand miles.

FOR about three days after that, Gus was so enthused over the hundred and one things to do, that stood out so simply and plainly all about him, making the world such an easy and straightforward place to work with, that he forgot all about the Ball. During those days, Kitty saw only him, and courteously asked to be excused when Thompson called. The garage was transformed, and customers were surprised.

Several times Thompson sauntered into the garage, nattily dressed, smoking a cigarette with a jaunty air, but covertly studying Gus, keeping an eye on him, trying to discover what had happened and how. Gus greeted him cheerfully and went on with his own affairs.

Then, somehow, things began to slip. He didn't know how nor why. He couldn't find the trouble in the gasoline pump, and paid no attention when Forbes answered crossly to an impatient driver who was waiting for his tank to be filled. Within two days he had cross words with Kitty over the silent look of disappointed reproach she had given him for thoughtlessly teasing her and hurting her feelings, as had been his clumsy wont in the past.

He spent all day Saturday on the carburetor of a Packard car and then got it back together wrong; it backfired and started a blaze under the hood of the car, and Forbes took twenty-five dollars' worth of damages out of Gus' pay check.

Sunday he committed a blunder in a baseball game because he consistently underestimated the speed of the Alliance players; his team blamed him roundly for the loss of the game, and he resigned his place on it. To cap it all, there was Thompson taking Kitty home from the game, with a leer of satisfaction on his face at Gus' downfall.

"All because I'm naturally dumb," Gus muttered to himself. "I don't get things figured out plain, somehow. I can't see 'em. Only after they've gone wrong, I can see how I'd ought to done it. Well, guess I'd better go out in the sandhills and bum around with the coyotes a while. That seems to be where I belong."

HE was startled to find himself right beside the olive-green Ball. Down below the surface of everyday, conscious thoughts, one's mind does queer things; and undoubtedly Gus' mind had in some way unconsciously associated his discovery of the Ball with the few days of clear vision which had so simplified the world's puzzles for him, and brought a taste of success. Up on the surface of his consciousness it had certainly never occurred to him that way. While he was busy brooding about his discomfiture in baseball, Thompson's machinations against him. and the threatened loss of his job at the garage, his unconscious mind had guided him back to the Ball, in the vague hope that somehow the Ball might again grant him another respite of grace. All the while he was thinking of other things and believed he was wandering aimlessly.

He approached the Ball a second time from a slightly different direction. That accounted for his finding the skeletons and the instruments. There were three of the skeletons huddled together in a hollow between two low sand mounds, already stripped of whatever flesh they might have had, by birds and beasts. They did not look human. The skulls were long and bulging and the limbs amazingly long and spindly; the creatures must have stood seven or eight feet high. There were no ribs nor vertebrae, but instead of them, plates of a horny, chitinous substance. A number of strange utensils of some sort were scattered about them—rods, tripods, metal cases.

GUS felt very reverent and melancholy about the little heap of relics, and gazed at it in silence for some minutes, not completely understanding its significance at the time.

He spent two hours inside the big spheroid. He looked it all over again carefully, but had sense enough not to bother the controls nor to touch anything about the mechanism. He found an object that must have been meant for a chair; a cushion-like thing shaped like a tomato. As he climbed up on it, it sank down deeply and comfortably with him. There he sat in silence and puzzled, trying in vain to catch the fleeting idea of how the Ball had helped him.

He was disappointed. Beyond the exhilarating lightness due to the diminution of gravity within the machine, he observed no effects of any kind, though he watched eagerly for them for several days. As a matter of fact, the dragging, leaden feeling in his legs that surprised him when he jumped lightly out of the door of the Ball, remained on his mind for some days as an ironic reminder of his failure.

Back to the dreary days of monotonous and ineffective toil. Back to the bitterness of seeing Kitty driven around in Thompson's luxurious car and the taunting leer on Thompson's face. Even the forgetfulness of troubles which baseball practice had once afforded, was now denied to him. The grease and grime and disorder, the disheartening mechanical problems, the clumsiness of both himself and Forbes, seemed all the harder to bear because of the memory of a few days of clear vision and efficient action. Desperately his mind sought some way of getting back to that.

One day he suddenly paid another visit to the Ball. The evening before he had come upon an item in the Nebraska State Journal. It looked rather insignificant, sandwiched in between sensational paragraphs on politics and crime; but it stuck in his mind and haunted him, all day.

It had been a particularly terrible day. He was groaning over the stripped gears of a Pontiac car, whose occupants stood about and criticized him; and Forbes fumed, but knew even less about the mechanism than Gus did. Gus went to bed exhausted that night, but still vaguely disturbed that there was something he ought to do about what he had read in the newspaper. During the night his subconscious mind must have worked it out, for he leaped out of bed early in the morning and dashed across the room for the paper to take another look at the item:

Drs. Loevenhart, Lorens, and Waters report that by means of their experiments with mixtures of sodium cyanide, carbon dioxide, and oxygen on insane and feeble-minded patients they have succeeded in quickening sluggish mental powers. After inhaling this gas their subjects talked much more rationally, reasoned better, and gave evidence of much more agile mentality. As soon as the effects of the gas passed off, they relapsed into their former stuporous or comatose states. Full scientific details of the matter are given in for March 16, 1929, Volume 92, No. 11, page 880. The results presented in this preliminary report are slight in degree, but are remarkable in their promise of sensational developments in a totally new field.

GUS was galvanized into activity. He dressed with race-horse speed, and hurried through the still sleeping streets to the lunch-counter on a run. The sleepy waiter came wide-awake when he saw Gus' energy, and served his fastest breakfast. In a few minutes Gus' Ford was rattling full speed ahead into the sandhills.

He arrived at the Ball's swinging green door breathless; he climbed in like a man who knew what he wanted and was going after it. In a thoroughly brisk and businesslike way he walked over to the cylinders in which the gas was stored and threw the valve of one of them wide open. His lungs, panting from his progress through the deep sand, took in the pungent fluid in deep breaths. For many minutes he stood there in front of the cylinder, inhaling the crab-apple-odored gas as deeply as possible. Then, like a flash it occurred to him that he was wasting it, and he turned it off with future needs in mind.

He rather expected to feel some physical sensation from its effects, but there was none. However, it had worked. He knew it had worked because of the promptness with which the idea of economizing the gas had come to him. In his ordinary state he could never have thought as fast as that, nor seen the point so clearly. Furthermore, the fact that he was able to deduce from his own prompt recognition of the need of saving the gas, that the gas had taken effect, was a bit of reasoning that encouraged him very much. He hurried back to town.

"What the hell do you mean?" roared Forbes, as Gus drove into the garage at ten o'clock. "This ain't an afternoon tea. You're fi—"

Gus smiled at him with calm and cheerful assurance.

"We'll be way ahead by noon," he said confidently. "I can fix that Pontiac in half an hour and then I can find the trouble in your check-book:"

He went to work, leaving Forbes standing there and staring. By noon the Pontiac was fixed and the tourists had been sent off satisfied. The check book balance was straightened out. And Gus had Forbes convinced that the space about the filling pumps in front of the garage ought to be paved with cement. Forbes was astonished into speechlessness.

By evening things were running beautifully at the garage; it was as well-organized and things worked as smoothly as they do in the big institutions in the cities; tourists went away declaring that they were sending all their friends in this direction—merely because Gus was able to see their viewpoint instead of his own, and was able to browbeat Forbes into seeing it because he understood Forbes' viewpoint. At the end of three days, Forbes had voluntarily given him a substantial raise in pay, and was still ahead because of the rise in receipts.

Again, Kitty was reconquered. It seemed easy to Gus; all he had to do was to put himself in Kitty's place, and treat her as he would like to be treated himself. Kitty was not only all his, but the happiest and most radiant young woman in town. She was overjoyed in Gus because she had always loved the solid and sterling qualities beneath his rough exterior. This new Gus was as strong and dependable as the old, but also courteous to her and thoughtful of her every wish. He was a wonderful man and all hers; and she glowed with pride as she walked down the street with him. The matter of the baseball team was not so easily handled; but Gus, being able to see things in their proper relationship, felt that it was a minor matter, and let it drop for the present as unimportant.

Thompson was disturbed. He walked past the garage many times a day, with black looks in Gus' direction; and Gus could see Thompson studying him in a puzzled fashion. At times he found Thompson following him about at night.

"Think you're smart!" Thompson once said sarcastically. "Well, never mind. I'll get you yet. I've got the means to do it with. You won't last long.

Knowing that Thompson was utterly unscrupulous, Gus was momentarily alarmed.

Gus found that he had to make another trip to the Ball on about the fifth day. It was a brilliant moonlight night this time, and he drove in the evening, taking Kitty along. The trip to the Ball was chiefly silent, because Gus was already losing some of the clear and full comprehension and sympathy that was his when he was under the influence of the gas. For the same reason he had failed to notice that Thompson had been watching closely and in secret all day, and was now following in his silent, powerful car, without headlights.

With wildly beating heart he turned on the valve and breathed the pungent gas for ten minutes.

His talk on the way home with Kitty was an inspiring one. By this time it was clear to him that the Ball was an interplanetary flier, whose occupants had perished in their first attempt to get about on Earth; and that the "gas" in the metal cylinders was merely some of the air of the planet from which they had come, stored under pressure for their long journey; and that its purpose was merely to supply the breathing needs of the passengers of the space-vessel.

"Think of the millions of inhabitants of that lucky planet," he said to Kitty, "who have the benefit of breathing an atmosphere that has the power of clearing your understanding and lining up your thoughts, as it has done for me!

"What a world! A world free from blunders and misunderstanding! A world in which there is only sympathy and no thoughtlessness. Suppose that all its people understand everything around them clearly—that they just see with their eyes open—each person understands how others feel about things, and his sympathy for the other fellow is stronger than his own selfish desires! What a world! No hate, no scraps. People getting along pleasantly, quietly, happily. No wars. Even money would hardly be needed. Service to others would be the principal end of living. Think of it! A planet on which every individual is happy!

"A perfect world! And this green Ball has come to us from it! The three unfortunate travelers met their deaths in this dreary desert, before they had gone a thousand yards from their machine. But maybe that was the kindest thing that could have happened to them. Suppose they had gotten among the squabbling, selfish humans on this planet? Gosh! Don't you wish we could get into the thing and sail up to the Perfect Planet, Kitty?"

"What a dreamer you've become, Gus!" Kitty exclaimed, enjoying the poetry of it, as any woman would. "But it's wonderful enough right here. When I think of how wonderful you were the first time you took the gas, my imagination runs away with me. Why! you could increase the business of the garage and make an immense salary; in fact pretty soon you could start a garage of your own or buy out Forbes. Then you could buy a drug-store and a picture-show, and lots of businesses, and you would be the richest man in Chadron. They might make you mayor, and elect you to the Legislature, and you could go to Lincoln!"

While they were on their way home, Thompson explored all around inside the Ball, and finally went away, shaking his head in bewilderment. But the malevolent gleam never left his eyes.

SUCCESSFUL days followed for Gus. He fixed a motor which had hobbled in from Alliance, where no mechanic was able to repair it. He spruced up the appearance of the garage, and put system into its working, and Forbes started a profit-sharing scheme with him. He got along beautifully with Kitty. Life was a thrilling inspiration when things went smoothly and efficiently. Even Forbes began to respect him.

On the fifth day, however, little blunders began to creep into his work. A cross word to a customer, a false move in a repair job, neglect of some obvious little word or deed, began to irritate him and make him feel self-conscious. The effect of the gas was wearing off and he needed some more. By this time he had enough of his own way about the garage so that he was able to get into his Ford coupé and drive out to the Ball.

"If things keep on going, I'll soon be able to get rid of this coffee-pot, and get me that keen little Studebaker roadster. But, for the present, I'd better save my money, so that Kitty and I could look for a house."

He left his car as usual at the end of the ruts that are called a road, and started on foot across the sandhills. About half a mile from his car, a man with a rifle popped out from behind a bank and stopped him.

"Can't pass here!" the man said. "Government operations going on."

Gus was surprised. He couldn't imagine any sort of government operations that would be of any good around here. Excavating for some of those buried bones and fossil turtles, perhaps. He said nothing and resumed his walk toward the Ball by a detour. Again he was stopped by a man with a rifle, who said that government operations were going on. He went around a circle of several miles trying to get to the Ball, but found it effectively surrounded. As he drove home disconsolately in his car, he pondered. These men looked too much on the side of the tough and disreputable to be government men. There was something suspicious about it.

The next morning he felt the lack of the gas more acutely. He was cranky and incompetent, and had several clashes with Forbes. Kitty came in, and after a few words, looked at him queerly, and finally went out with a sad, puzzled look on her face. Then Thompson dawdled in with a triumphant leer. He watched Gus in insolent silence, smoking a cigarette in violation of the garage rule. As Gus threw down a wrench with an exclamation of helpless exasperation, Thompson guffawed in satisfaction.

A light broke upon Gus. He remembered Thompson's trailing him about, and vaguely recollected a car far behind them when he had driven out with Kitty. He stalked menacingly up to Thompson.

"Say!" he exclaimed. "What's the idea? I found that Ball. You have no right to it!"

"Careful with that greasy wrench, Bo!" Thompson warned, glancing out to the sidewalk and exchanging a significant glance with a burly looking tough who stood there. "No rough stuff. For your own good, see!"

"That Ball is mine!" Gus pleaded weakly, seeing the ruffian sidling toward them.

"Try and get it!" laughed Thompson.

"But why are you doing this?" Gus asked anxiously.

"Since I have the upper hand," Thompson sneered, "I can afford to be nice and tell you all about it. I want Kitty. I get what I want. She seems to prefer me to you, except when you've been in that contraption out there. I don't know what it is nor how you do it, but I've proved it. I've followed you out there; and after you've been there, you have a way with people. So, you don't get over there again until I've had my way with Kitty."

He spun on his heel and walked away, leaving Gus stunned.

"And it won't be long, either," Thompson flung back. "I'm rushing her fast."

He stopped and turned back to Gus.

"Then I'll blow up your thing out there. How long will Forbes keep you after it's gone? He has no use for a clumsy tramp. Then what will you do? I can see you now, walking down the railroad-ties in ragged shoes and a scraggly beard, cooking coffee in a tin can. What will Kitty think of you then?"

He walked away, followed at a distance by his uncouth bodyguard, leaving Gus dumbfounded. Thompson's words cut into his heart like ice, and he felt himself helpless. As a result, his work was all the more clumsy and inefficient. It was a busy day, and both he and Forbes were desperately snowed under. Forbes swore continuously.

"You're the damnedest fellow I ever saw. Some days you're good. Today you're just a damned nuisance around here, and I'd like to kick you out."

EVENTUALLY the interminable day was over, and Gus dragged home in hopeless discouragement. With the gas gone, he was lost. Dumbly he turned to Kitty for solace. But, as was his wont, and as is human, he blundered from the first.

"So you've been fooling around with that Thompson again, eh?" he flung at her. He knew it was a tactless blunder, but it just slipped out. Kitty looked at him sadly.

"He's a crook and a coward "

"If that's the way you're going to talk to me, you don't have to come," Kitty answered hotly.

A quarrel followed. Gus slammed out of the door and slumped gloomily into the night. As he got across the street he saw Thompson go into the yard and up the steps of Kitty's house. A chuckle came over to him through the darkness.

Gus was beside himself with rage and anger. He stood there paralyzed for a long time; whether it was minutes or hours he did not know. Then he walked; he covered every block in the little town, walking off his anger. Finally, late in the night the idea came to him. He whirled about and ran toward his room. He seized his .22 rifle.

"I might as well get killed as to go on like this," he muttered grimly.

He got into his Ford coupé and stepped on the starter. It was dead. He looked under the hood. The distributor wires were cut. The manifolds were cracked and showed signs of heavy blows. The carburetor was smashed flat. It would take hours of work and expensive parts to repair the damage.

Gus felt a wave of weakness sweep over him, and almost sank to his knees. Everything was going against him. That fiend, Thompson, was too strong and too clever for him. Now he was helpless. What could he do? He was beaten to a standstill.

Desperation however suggests plans, and Gus was desperate. He leaped out of his car and hurried toward his employer's garage, paying no attention to the man following in the shadows at some distance behind. He opened the doors and got into Forbes' big Nash. The motor roared and the powerful car dashed out of the garage. Gus was out in the street, but not before a man had leaped up on the running-board. The dark shape hung on with one hand, and maneuvered something, a gun, with the other.

"East!" commanded a hoarse voice, accompanied by a flourish of the big pistol.

"So, you're one of Thompson's men?"

"East, I say, or I'll put some bullets through the carburetor!"

Gus obediently turned the car East. He was playing for time to think. He was desperate; he gritted his teeth, lights blazed before his eyes, and his head throbbed.

"Hey!" shouted the dark form in hoarse warning. "Both hands on the steering wheel!"

Half a block ahead stood a gasoline pump at the curb, Chadron's rival garage. It was hardly visible in the dark, but Gus well knew where it was. Again the low cunning of the desperate animal was aroused. One hand left the steering-wheel and raised slowly.

"Hey!" the man yelled. "Both hands, I said!"

Crash! The man was gone. There was a thud on the pavement and the clatter of the rolling, sliding gun. The Nash tore on, with Gus at the wheel, having grazed the gasoline pump by an inch, scraping his assailant off the running board, and leaving him behind, a groaning, squirming prostrate mass in the dark.

With pounding heart and muscles tight, Gus continued his course east. He made three miles out of town, described a big circle to the south, and finally turned back west on the old familiar trail. His headlights were dark. Then, when he reached the end of the road, he crept forward along the sand, with his little rifle ready. He was mostly animal and very little human just then.

His alert ears caught the hum of a car far away, but he could see no sign of it. Disregarding it, he crept on toward the Ball. It was hard to find in the starlight. It seemed that he crept and crawled about wearily for hours, this way and that. Finally he saw it, and realized that he had been near it and had been circling it. He was astonished that he had not encountered any guards.

He crept on toward the Ball. Infinitely careful, slowly as a snail, painfully tense, he approached the towering mass. No one interfered with him. He could see the door above him in the starlight, and no one about. His heart pounding, his head throbbing at the thought of getting the gas again and taking his place in the sun, he rose slowly; slowly he put his head in, slowly he climbed in. It was move, stop, listen; move, stop, listen. Not a sound did he make, nor a sound did he hear. When he got well inside he turned his flashlight toward the drums of the longed-for gas.

"Ha!" chortled the voice of Thompson just outside the door in the blackness. "Just what I wanted."

Gus felt the stab of astonishment go right through his being. Instinctively he turned the light toward the voice, and there was Thompson climbing to the door and leveling a gun at him.

"Now you'll show me how you work your pretty little racket," Thompson gloated. "It might do me some good after all. After that, what becomes of you won't interest anybody."

Gus' muscles tightened.

"I might as well get shot as go on with it," leaped through his brain.

Gus leaped, gathering every ounce of strength.

It was terrific. He had forgotten the diminished force of gravity within the Ball. He hit Thompson like a flying projectile out of a gun. Thompson went down with a grunt, firing his gun wildly once; a second or so later the flattened bullet tapped back to the floor. Gus rolled over and over and found himself standing on his head. He recovered his balance, and by the aid of his flashlight secured Thompson's gun and threw it out of the door. He clutched his fingers to get them around Thompson's throat. At that moment, Thompson fell and landed on his back and neck with terrific force.

Both of them staggered and rolled across the room, into some fragile things. There was a smashing and a tinkling of broken fragments. The crackle of a blue electric spark drove them in opposite directions. Gus still had his flashlight, and he searched the place with it for Thompson. He was aching to get his hands on Thompson, knowing that he could shake him like a terrier shakes a rat. He discerned him bending over some smashed things. Thompson suddenly straightened and something crashed down on Gus' hand, making it numb and painful. The flashlight fell to the floor and broke, leaving them in darkness. In another moment, Thompson had leaped upon Gus. taking him by surprise.

Gus however, was more familiar by this time with the decreased gravity, and thought of it at once. A great heave of his back sent them both up into the air, and before they alighted, Gus managed to get a more advantageous hold. In a tight clinch they rolled about, rose, staggered, made wild plunges and surprising leaps, smashing into things, and wrecking every breakable article about the place.

They crashed into the stacks of metal cylinders several times, bringing forth a resounding clank. Gus was slowly getting a better hold under Thompson's shoulder and in front of his neck, and bending him backwards. A sudden kick of Thompson's sent them reeling away from the stack of cylinders, and Gus' coat caught on some projection and gave a resounding rip. At the same time, a sizzling, faint but distinct hiss began, though neither of them heard it; nor did either of them note the penetrating, crab-apple-like odor. Gus was straining to break Thompson's back, and Thompson was wildly reaching for something with which to crack Gus over the head, but gradually his soft muscles and dissipated habits were telling against him. He was weakening.

Then, as they rolled and catapulted into the end where the machinery stood, and slammed into a caseful of apparatus, there was a loud crack, the blue flash of a spark, and both of them twitched and lay still.

FOR many minutes they lay there, and everything was silent except the faint sizzle of the escaping gas. It began to look as though the long struggle, for success and happiness and a girl, had ended equally and conclusively for both of the two dark, motionless forms stretched on the floor. An electric charge, disturbed by their combat after its long interplanetary journey, put a sudden end to the conflict.

After many minutes, one of them stirred, gasped, and breathed deeply; and in a moment the other did the same. There were groans and sighs and turnings over. Consciousness returned gradually to both of them at about the same time. Both sat up together and faced each other in the darkness. Both staggered to their feet, still silent. Finally, Gus spoke first.

"Are you all right? I hope I haven't hurt you."

Thompson shook his head, as though that were far away from his mind.

"I've been a fool," he said.

"We all are—most of the time," Gus replied.

"I'm quitting my silliness, and being fair from now on. We'll let Kitty herself decide between us."

"You mean—" gasped Gus, "—we're friends?"

"The only thing to be."

They shook hands impulsively, and forgetting the lowered gravity, executed a big leap upward and toward each other.

"As long as the gas holds out," Gus reminded. He explained the action of the gas.

"That means," Thompson said, stepping over to shut off the valve from which the gas was still escaping, "that we'll have to use it regularly; and as soon as possible have it analyzed so that we could make some more. We'll both use the gas, and if Kitty prefers you, you're welcome and have my congratulations.

"Then we'll set up and manufacture the gas, not only for our own continued use, but for others. We'll supply it to begin with, until others get started. Before long, the whole world can have it. Then indeed old Mother Earth will be the Perfect Planet."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.