RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

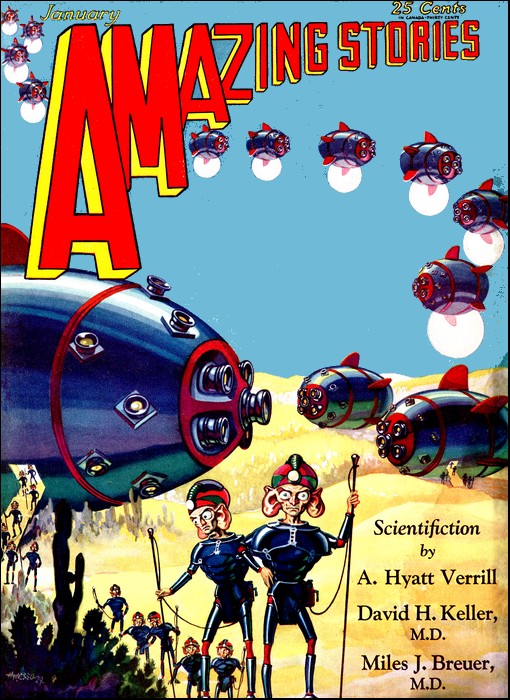

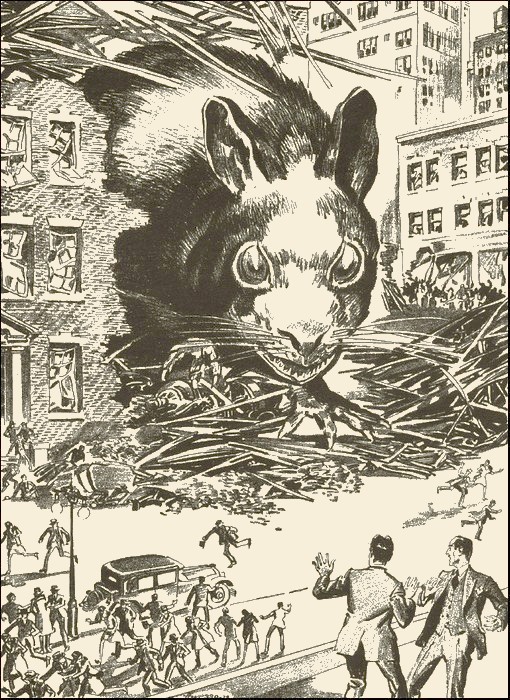

Amazing Stories, January 1930,

with "The Hungry Guinea-Pig"

From the flattened wreckage there gazed out at the

rapidly growing crowd across the street a pair of im-

mense pinkish-brown eyes...set in a head that looked

somehow like that of an extremely magnified rabbit.

WHAT makes a giant? What makes a dwarf? It is a generally accepted idea among gland specialists that one of the ductless glands is responsible for abnormal growth. If the pituitary gland is a factor, what would happen if some innocent and gentle animal were treated with the extract? Glandular science has become a most important part of medicine and some physicians specialize in its applications. Dr. Breuer must be recognized not only as an excellent writer of scientific fiction, but as an authority on his subject.

DR. CLARENCE HINKLE walked reminiscently westward along Harrison Street. Things had changed. The city had grown.

"The spirit of Chicago is growth," thought Dr. Hinkle.

Dr. Clarence Hinkle of Dorchester, Nebraska, was a country doctor of the modern, high-caliber type. He was thoroughly scientific in his methods and made use of all the facilities that modern science offers, in taking care of his prosperous farmer patients. He kept up with scientific progress by visiting conventions and taking post-graduate courses regularly. But this was the first time since his graduation that he had been back to Chicago and his Alma Mater. Now, after ten years of successful, satisfactory practice, he was on a pilgrimage back to old Rush. For study, yes; but also for a visit to the old places and to see old friends again.

He was especially anxious to see Parmenter. He and Parmenter had roomed together for four years, two on the South Side at the University of Chicago, and two on the West Side at Rush, in the center of the greatest aggregation of medical colleges and hospitals within the area of a square mile known to the world. Parmenter had been brilliant and eccentric. As a student he had done astonishing things in biochemistry. He had made a wild and brilliant record in the war. Hinkle had kept up a desultory correspondence with him, which had conveyed hints of some research of Parmenter's; something amazing, but without details of information. Parmenter's work had so impressed the University of Chicago that they had built him a laboratory and dispensary to work in.

Dr. Hinkle walked up Harrison Street looking for it. The huge bulk of the Cook County Hospital loomed ahead of him. Thousands of Rush graduates all over America will appreciate how he felt when he saw the old corner at Harrison and Congress Streets, with the venerable and historic building gone, and a trim, businesslike new one in its place. It seemed that sacred memories and irreplaceable traditions had been desecrated. But, progress must go on. However, the old "P. & S." was also replaced by a great maze of new buildings. And there ahead was a sign: The Parmenter Institute. So, they had even named the clinic after him! Indeed, he must have done something.

He stopped a moment to look the building over. Two trucks piled high with heads of cabbage drew up before the side entrance. The drivers conversed as they unloaded the cabbage.

"Yesterday," Dr. Hinkle overheard one of them say, "I delivered a load of freshly cut alfalfa here. You'd think they had a lot of big animals. Funny thing for this part of town. And tomorrow we'll be bringing more stuff; wait and see."

They carried basketloads of cabbage-heads up the short flight of stairs, and the porter of the building always opened the door and took the baskets from them.

"Listen!" whispered one of the truck-drivers to the porter, catching him confidentially by the shoulder; "what's all these loads of green stuff for?"

"For feeding our experimental animals," replied the porter haughtily, as though he knew things they were not competent to understand.

"What sort of animals?" asked the truck-driver, looking doubtfully at the building, whose windows were the same as those of the others with their small rooms.

"Guinea-pigs," replied the porter.

"Guinea-pigs?" The truck-drivers looked blankly at each other. "What are guinea-pigs?"

"Hm!" snorted the porter contemptuously. "Don't know what guinea-pigs are!" He saw them every day. "A guinea-pig is an animal like a rabbit; no, smaller—half as big. It looks something like a rabbit and something like a rat."

"Aw!" growled the truck-driver. "He's stringin' us."

"No," replied his companion. "That's true. I saw them when I was in the hospital. The doctors use them for speerments."

An inner door opened and a white-clad attendant stood looking out of it into the hall. For a while, as the door stood open, they heard a number of short, low-pitched, whistle-like notes. Then another hand slammed the door shut, and again the hall was dark and silent. To Dr. Hinkle's mind, the sound had no resemblance whatever to the squealing of guinea-pigs. The truck-drivers continued to carry cabbage and to tarry inquisitively.

Dr. Hinkle walked briskly up the front steps of the Institute, and into the office. He handed his card to the girl at the information desk, stating that he had an appointment with Dr. Parmenter.

"The doctor said you were to come into the office and wait for him," she said, showing him into an adjoining room.

IN Parmenter's office, a large desk was piled high with neatly arranged stacks of books and papers. Sections of bookcases filled with books, papers, and chemicals, covered almost all the wall space, except where it was occupied by a great steel safe. Since there was also a safe in the business office through which he had passed, Dr. Hinkle concluded that this one held, not money, but, rather, records of tremendous importance, or some sort of chemical preparation that might be dangerous in the hands of the wrong people. He sat down and waited, his eyes flitting back and forth among the titles of the medical, chemical, and biological publications.

As he sat in his chair, he could see through the open door down a long hallway. At the end of the hallway was another door; a curious door that seemed to be made of heavy planks placed horizontally, and held together with iron straps. This door was slowly pushed open, an interne emerged into the hallway, and with considerable effort tugged the door shut again and turned a heavy bolt. While it was open, Dr. Hinkle heard several more of those short, reverberating, fluty notes, like the low pipes of an organ. They were accompanied by heavy, dragging sounds, as of something tremendously heavy scraping on the floor with little short scrapes. Another interne came down the hall, and as the two met, the first one said:

"This can't go on much longer. It's got to be stopped."

The second one laughed a harsh, mirthless laugh.

"I guess we'd have stopped it already, if somebody would tell us how."

The two went back through the heavy door. Dr. Hinkle craned his neck to get a glimpse through it. In the vast half-gloom through the door, he caught a fleeting glance at a huge curved back and flanks, covered with long, straight brown hair.

"A cow? Or a bear?" he wondered in astonishment. "It's bigger than a couple of both. What in—"

Dr. Parmenter walked briskly out of a door down the hall, and seeing Hinkle in his room, hastened in. Dr. Parmenter had a worried look about him; a wrinkle in his forehead that he couldn't seem to smooth out, a wrinkle that betrayed some sort of preying anxiety. He looked much older than his country confrère, though the quondam roommates were really almost of an age. They stared wildly at each other, each surprised at the changes in the other. They gripped hands in silence for some minutes.

"Well, so this is what you're up to!" Hinkle exclaimed.

"You look like a million dollars!" Parmenter congratulated.

They sat and chatted small stuff for a while.

"You do look prosperous," Parmenter insisted. "You must be doing well."

"Oh, I've put aside a few thousand. Ten more years like these, and I could retire in modest independence."

Parmenter sighed.

"I can't seem to get ahead much financially." He paused wistfully. "You have a family?"

Hinkle nodded. "Two boys and a girl."

"Happy dog." Parmenter had a far-away look in his eyes.

Hinkle was also looking a little thoughtful.

"The medical drudge, the traveler over country roads, the custodian of colds and stomach-aches wishes to inquire," he said earnestly, "if there is not happiness in being known all over North America; in having papers published in every scientific journal; in being invited to great conventions as an honored guest; in having a dispensary built for you and called after you—a young fellow like you? You make me feel like a moron."

Parmenter's face warmed up a little with pride.

"And a colonel during the war!" Hinkle continued. "Do you know, I'm famous back home among the common folks just because I can say I used to room with you?"

Parmenter was silent but grateful. Finally he said:

"So you got into the fracas in France too? How did you go?"

"Oh," replied Hinkle, as though he disliked to admit it, "plodding along in a field-hospital unit. But you—" his voice rose in surprise again—"a medical man! How did you happen to go as an artillery officer. I'd think you'd want to give your country the benefit of your scientific training."

PARMENTER sat straight up in his chair. His face livened up with interest.

"Scientific training!" he exclaimed. "Maybe you think you don't need scientific training in the artillery. I dare say I made better use of what scientific ability I may have, in the artillery than I ever could have done as a mere medical officer. Wasn't it so in this war, that only one medical officer out of a thousand had any opportunity to do scientific work? The scientific training I got in the artillery corps has helped me to accomplish what I've done since the war."

Hinkle stared incredulously.

"If you don't think it takes science," Parmenter said, "to yank a four-ton gun into place in the middle of a field, and put a shell on a spot the size of a door ten miles away at the third shot—you've got another guess coming. That takes real figuring, and real accuracy in working. To come up into position one night, and by the next night to have the country for twenty miles ahead plotted into numbered squares, into any one of which you can drop a shell instantly, within ten seconds of a signal from an airplane observer—the whole medical department didn't use as much science as did our little battery of heavy field artillery. That was a glorious kick-up—"

He stopped and turned his head, as several fluty whistles came faintly from within the building.

"But this is just as exciting," he continued when the eerie sound had ceased. He smiled at Hinkle's look of amazed inquiry.

"I guess I'd better show you around," he said. "I've got something here that hasn't been published yet."

"I got a peek at some ungodly thing a while ago," Hinkle remarked; "What is it—a buffalo? No; it's three times as big. A dinosaur? I never heard of any animal that would fit what I saw. Is that what makes the tooting?"

Parmenter stood enjoying his friend's amazement.

"Perhaps I'd better prepare you for the sight first. I can explain briefly in a few moments. A few years ago I got interested in ductless glands and internal secretions, and my interest eventually narrowed down to two of them about which the least is definitely known; the pituitary and the pineal bodies. I've done a lot of work on these two little brain-glands and written a lot about them. Both of them are intimately concerned in body growth. You will recollect that in the pathological condition known as acromegaly, in which there is an excess of pituitary secretion supplied to the body, the limbs grow long, and tall giants are produced; and you know how stunted the individual remains in cases where the pituitary body fails to secrete adequately. Perhaps you have also followed McCord's experiments: he fed chicks with pineal glands from cattle, and they grew to three or four times the size of normal birds. Then, a couple of workers in California separated from the pituitary body a substance which they called tethelin, and which when injected into mice, doubled their growth.

"I repeated and confirmed their work, and made large quantities of tethelin. The fact impressed me that neither the pineal experiments alone nor the pituitary experiments alone produced a well-balanced increase in size of the experimental animals. I obtained the active principle of the pineal body, which I took the liberty of naming physein; I got it by four-day extraction with ether in the Soxhlet apparatus and recrystallization from acetone. Man, you should have seen the baskets and baskets of pituitaries and pineals from the stockyards, and all the ether and acetone we splashed. But, after all the dirty work, the half dozen bottles of gray powder that we got gave us a lot of satisfaction.

"Of course we injected the stuff into guinea-pigs. The guinea-pig is always the victim. At first we used six; and six controls which received none of the tethelin-physein solution. But we soon discarded the controls, for the injected animals grew like the rising of the mercury in a thermometer. They grew so fast that we had to kill five of them when they were as big as dogs, for fear that we could not feed them. This one we kept in order to ascertain the limit of size to which it would grow. Now we have had it six months, and it is as big as—well, you'll see. It is becoming difficult to feed, and it's a rough clumsy beast. I'd get rid of it, if I knew how—"

He was interrupted by a terrific hubbub from within the building. The whole structure shook, and there was a vast ripping, tearing. Crash after crash rent the air, followed by hollow rumbles and reverberations.

Dr. Parmenter dashed to the door and looked down the hallway. There were great cracks in the plaster, and chunks of the ceiling were raining down to the floor. The door at the end of the hall hung loose, revealing beyond it, not the semi-gloom of a big room, but the bright daylight of outdoors; just as though a piece of the building had been torn off. A huge rattling, banging din was going on, with clouds of dust filling the air.

He started down the hall, but a shower of bricks and plaster through the wrecked doorway deterred him. Seizing Dr. Hinkle's arm, he dashed out to the street, dragging the latter with him. Hinkle was puzzled; Parmenter was pale and looked scared, but seemed to know what was going on.

OUT in the street, people stood struck motionless in the midst of their busy traffic. Fascinated, like a bird watching a serpent, they stood glued to the ground, their eyes turned toward the Institute. A moment ago the business of Harrison Street had been going monotonously along, just as it had gone for a couple of score of years. Suddenly two or three people had stopped. Some sort of queer things had appeared in a window of the Institute, horrible looking objects, as though a monkey had jumped up on the sill. But no, the pink things were not arms and legs; each had a single huge claw at the end of it. The whole thing looked like an enormous rat's paw. The group of astonished people standing and staring at it increased momentarily.

Then the brick wall bulged outwards, and a section of it as big as a room fell out on the ground in a mass of débris. A vast brown back appeared in the opening, and the thing's clumsy scratching threw layers of brick wall across the street. The enormous animal rolled out and disappeared behind the three-story signboards in the adjoining empty lot.

Dr. Hinkle and Dr. Parmenter ran across the street to watch. There was a huge commotion behind the signboards; then with a crashing of breaking wood the whole structure of signboards went over. There were screams of people on the sidewalk who were caught beneath the falling mass, and the tinkle of glass from smashed automobile windshields. From over the flattened wreckage there gazed out at the rapidly growing crowd across the street a pair of immense, pinkish-brown eyes. They were set in a head that looked somewhat like that of an enormously magnified rabbit, though it was held down close to the ground. Behind it arched a great brown back, higher than the second-story windows, covered with long, straight brown hair, with black and white stripes and spots.

The creature looked around, jerking its head first one way and then another, apparently very much frightened. Then it moved forward a step to the accompaniment of crackling timber. The crowd surged away, and disappeared frantically into buildings and around blocks, as the animal slowly started toward it. Dr. Hinkle felt a sinking sensation within him as he realized that there were injured people on the sidewalk under that mass of wreckage that crunched and crumpled under the animal's huge weight. Everywhere, windows were filled with heads. In the Institute, the undamaged windows contained white-clad doctors and nurses. In the next block, an elevated train passed with a hollow, rumbling roar, and the giant guinea-pig crouched down and trembled in fear.

Then it ran out into the street with short, quick steps. One could get some idea of its size from the reports of the spectators, who stated that there was barely room in the street for it to turn around in. It had started across the street, and in its efforts to get loose it caught the odor of some scraps left behind at the unloading of the cabbage trucks, for it suddenly began to turn around. Its paw caught in the window of a flat across the street, and in its efforts to get loose it wrecked a side of the building. Beds, refrigerators, and gas-stoves hung out in the open air. The animal seemed very much frightened.

Dr. Hinkle and Dr. Parmenter had been carried by the crowd to the solid shelter of the Cook County receiving-ward. People began to sense that the thing was dangerous, and scattered precipitately away from the scene of excitement. An Italian fruit vendor was pushing his cart westward along Harrison Street. The animal smelled the fruit and immediately became very much excited. It turned this way and that, but always there were buildings in its way. Finally it stepped up on the roof of a two-story flat on the corner. The roof caved in, and the screams of women were heard from within. In its effort to extricate itself, it made a wreck of the building. Then it hastened down a cross street in pursuit of the fruit cart.

The Italian heard its approach and stopped; he stood paralyzed by fear. The guinea-pig never saw him at all; it leaped for the fruit and one accidental blow of its paw knocked him over and crushed him flat. Only a bloody, smeary, shapeless mass on the street remained to tell the tale. Parmenter, already pale and trembling, shrank back as the Italian screamed and raised his hands above his head, carried down by the giant paw. Parmenter's eyes had a cowed, beaten look in them.

THE fruit on the cart made a scant mouthful for the guinea-pig. It chewed very rapidly, with a side-to-side movement of its jaw. When it raised its head, its bare lower lip was visible, pale pink, and below it a group of short, white whiskers. The grinding of its teeth was audible for a block. Another train thundered along on the elevated railway, its windows crowded with curious heads. The guinea-pig became frightened again, and ran swiftly westward along Harrison Street. As it ran, its feet moved swiftly beneath it, while its body was carried along smoothly rocking, as though it were on wheels. It ran very swiftly, more swiftly than the automobiles that tried to get away from it; and the people along the street had no time to get out of the way. First a child on a tricycle was swept away, and then two high-school girls disappeared under it; and when it had passed, it left behind dark smudges, as when an automobile runs over a bird. It ran three blocks west, eating up all the potatoes and vegetables, baskets and all, in front of a grocery store, and then turned north. Hinkle and Parmenter lost sight of it, noting a car filled with armed policemen in pursuit of it. Parmenter's nerves were indeed shaken. He stared straight ahead of him and walked along like a blind man. Hinkle had to guide him and take care of him as though he were an invalid. Parmenter felt himself a murderer. All of these deaths were his fault, due directly to his efforts. Despite the fact that he was half paralyzed by remorse, he persisted in trying to follow the animal with a desperate anxiety, as though in hopes that he could yet do something to right the wrong. For a while he led Hinkle around aimlessly.

Then they heard the sound of the firing of guns, and breaking into a run, came around the block into Jefferson Square, a small, green park a couple of blocks area. There the guinea-pig was eating the shrubbery, tearing up great bundles of it with its sharp teeth. It smelled hungrily of the green grass, but was unable to get hold of the short growth with its large teeth. The bandstand and the bridge across the pond were wrecked to fragments. The police were shooting at the animal till it sounded like a battle, but it was without effect. Either its hide was so thick that the bullets did not penetrate, or else the mass of the bullets was so small that they sank into its tissues to no purpose. Once they must have struck it in a sensitive spot, for it suddenly scratched itself with a hind leg, and then went on chewing shrubbery. The police crept up closer and kept on firing; then all of a sudden the guinea-pig turned around and sped up the street like lightning. Before the police recollected themselves, it was out of sight, and the street presented a vista of overturned Fords, smashed trucks, a street-car off the rails and crowded against a building, and tangled masses of bloody clothes. A trolley-wire was emitting a string of sparks as it hung broken on the ground, and a fountain of water was hurtling out of a broken fire-plug. The animal disappeared to the north; the two medical men sought it for a while and finally gave it up.

Dr. Hinkle decided that he must get his friend somewhere indoors. They succeeded in finding a taxi in the panic, and drove to Parmenter's apartment. Hinkle had to support Parmenter and put him to bed. Parmenter would not eat. He continued to groan in incoherent misery. Hinkle went out and got some evening papers. The headlines shrieked.

"Monster Devastates West Side!" "Mysterious Animal Spreads Terror!" and so forth in their inimitable style. The reports said it was a fearful bear, bigger than an elephant or a freight engine, or that it was a prehistoric saurian miraculously come to life. They stated that it hunted people as a cat hunts mice, and that it had eaten great numbers of them, and in its savage rage had smashed buildings and vehicles. Gun fire had no effect on it, and it had in fact devoured a squad of policemen who had been sent out to kill it.

Parmenter sat up when Hinkle read some of these reports.

"The poor idiots!" he exclaimed in sudden and composed wrath. The grossly exaggerated reports seemed to have the effect of pulling him together.

"Newspapers act like a bunch of scared hens," he said contemptuously. "They're starting a real, insane panic, that's all. What do you think, Hinkle; is that guinea-pig going about deliberately killing people? Is it wrecking the town out of pure spite?"

"It is quite evident," Hinkle said, "that the guinea-pig is far more frightened than the people are. The deaths are mere accidents due to its clumsiness—"

"Yes," reflected Parmenter sadly. "A guinea-pig has about as little brains as any animal I could have picked out. If it had been a dog, it could be careful."

"And the thing seems to be hungry," Hinkle continued. "Hunger seems to be the main cause of its destructive proclivities. It is hungry and is hunting around for food. And food is hard to find in this little ant-heap."

Hinkle was correct. The whole subsequent history of the huge animal's wanderings about the city represented merely a hunt for food, and possibly a place to hide. It is doubtful if its hunger was ever satisfied, despite the vast amount of foodstuffs that it found and consumed. Certainly it paid no attention to people. The wrecking of the Lake Street Elevated Station was probably due to its efforts to find shelter. In the evening the guinea-pig tried to burrow under the station and hide. The space underneath the station was too small and the steel beams too strong; and it gave up and turned away, but not until it had so bent and dislocated the steel structure that the station was a wreck and train service was interrupted. The last report of the night located it on West Washington Street. People were afraid to go to bed.

IN the morning Hinkle dashed out after newspapers. The editorials corrected some of the previous day's errors about the ferocity of the giant guinea-pig, and called attention to the fact that it had definitely increased in size during its sixteen hours of liberty.

"If it keeps on growing bigger?" the editor suggested, and left it as a rhetorical question. The news items stated that during the night the guinea-pig had located the vegetable market on Randolph Street, for many buildings were wrecked and their contents had vanished. The Rush Street bridge was smashed, as were the buildings at the edge of the water. And the city was beginning to go into a panic; for no efforts to stop the animal had as yet been of any avail.

THE evening papers of the second day brought a new shock. Hinkle had spent the day following Parmenter about. The latter dashed this way and that, in taxicabs, surface-cars, buses, and elevated trains, in frantic efforts to catch up with the animal. They did not catch sight of it all day. They arrived in Parmenter's apartment in the evening, dead tired. Parmenter was in the depths of depression. Hinkle opened a bundle of newspapers they had not had time to read.

"LAWYER'S WIDOW SUES SCIENTIST!" announced the headlines;

"Mrs. Morris Koren Files Claim for Damages Against Professor Parmenter for Husband's Death. One hundred thousand dollars is demanded by the widow of the prominent attorney who was crushed in his automobile by the huge guinea-pig yesterday. The plaintiff is in possession of a clear and complete chain of proofs to establish her claim—"

Parmenter sat silent and wild-eyed. Hinkle clenched his fists and swore. He thought Parmenter was suffering enough with all these deaths on his conscience. Now, to have added to it a lawsuit with its publicity, and the almost certain loss of the property he had accumulated, and the complete wrecking of his career! Parmenter gazed now this way, now that, and sat for a while with bowed head. He rose and walked back and forth. He sat down again. He said not a word. Hinkle sat and watched his friend's sufferings with a sympathy that was none the less genuine for being speechless. Before him was a broken man, in the depths of disappointment and despair. All his life Parmenter had been working, not for his own interests, but for the good of mankind. To have the people to whom he had freely given of his life and work turn against him in this unkind way was something he could neither grasp nor endure. Hinkle never saw a man change so completely in twenty-four hours.

A later edition carried the announcement of another lawsuit against Parmenter. The Chicago Wholesale Market claimed $100,000 damages for the destruction of their buildings and merchandise stock. Their evidence was also complete and flawless.

By morning, Parmenter's depression was gone. He was pale, but calm and deliberate. His lips were set in a thin line, and the angles of his jaws stood out with set muscles. He had shaken off his nervousness and a steady light shone in his eyes. His keen brain was at work as of old. Hinkle understood; no words were needed. They had been roommates for four years and knew each other's moods. Hinkle gripped his friend's hand and put his left on Parmenter's shoulder. As eloquently as though he had said it in words, he was expressing his sympathy and his joy because his friend had found his strength again and in spite of his troubles. Troubles indeed, for the loss of life was already beyond estimate; and complete ruin for Parmenter was a certainty.

"Got to find some way of stopping the beast," Parmenter said succinctly.

"If it can be done, I know you'll do it," Hinkle replied. "Only tell me what I can do to help you."

"Stick around," said Parmenter. "That'll help." They understood each other.

Hinkle could not help admiring the sheer will-power of the man. Newsboys went bawling by the window. The morning papers announced a fresh string of lawsuits, claiming a total of damages of nearly a million dollars. Parmenter paid no attention. He nodded his head and went on making notes with his pencil on the back of an envelope. He had made up his mind, and news had no further effect on him. Only once he took Hinkle's breath away with a dispassionate, impersonal reflection:

"The civil damage suits will break down of their own weight. The matter has already gone so far that it is ridiculous. It won't pay any of them to spend any money bringing it into court. But, suppose it develops into criminal proceedings?

"Well, that's all I have to expect. Science does a lot of good. But sometimes it miscalculates and does harm. Under the laws of Nature, miscalculators pay the penalty of elimination."

Parmenter sat motionless most of the day. He moved once to eat mechanically, and once to receive reports by telephone from the Institute. His mind was busy, as usual.

THE evening papers brought reports that the guinea-pig had gotten tangled up in a trolley-wire and received an electric shock which had sent it scuttling to the Lake. The wire dropped to the ground, interrupting the streetcar service of that part of the city. The guinea-pig ran straight to the water. There it again smelled green forage and ran northward along Lake Shore Drive. In an hour it had devastated all the trees and shrubbery, and eaten up everything green in sight. Because it spent more time at this place, the police detachments caught up with it, and were again vainly pouring bullets at it.

Again something startled it, and it ran off westward. It ran so swiftly that it was out of their sight in a few moments. For the greater part of two days they pursued it about the city in this manner, and the tale thereof is largely a repetition of what has already been said.

Parmenter hit his knee with his fist.

"We've got to stop the brute somehow, or there won't be any Chicago left. Who would have thought that a brainless, clumsy, stupid thing would have the whole city at its mercy?"

HINKLE was turning over the pages of the newspaper, scanning the editorials that were already predicting what Parmenter had foreseen, the breakdown of the damage suits. The editor stated confidently that they would never get into court.

"Better get a lawyer anyway," Hinkle suggested.

"I won't need one." Parmenter's face brightened. Did he have an idea?

There was no time to ask. A strange murmur had arisen outdoors. A rushing, rustling hum, like that of a flowing river, came from the distance. Now and then shouts rose out of the confusion. Hinkle went to the window, full of curiosity at the city's manifold noises.

He stopped for a moment. He also had a quick brain, and in an instant the meaning of it flashed through his mind. He dashed back and caught Parmenter by the arm. With hats and coats in the other hand, he dragged Parmenter toward the back of the house.

"What's up now?" Parmenter demanded out of the depths of his preoccupation.

"A wild, raging mob!" Hinkle shouted. "The people are dancing with ferocity like a bunch of savages on the warpath. I saw clubs and guns. They probably found that there was no redress in lawsuits, and are coming after you to settle it themselves."

Parmenter still dragged back, reluctant to follow Hinkle.

"I don't care to escape," he protested. "What is the use of life in a world where there are people like that?" Hinkle stopped a moment.

"You seem to have struck some idea for helping this city," he said sternly. "Do you want them to lay you out before you can rectify this blunder of yours?"

They were blunt, cruel words, but they worked. Parmenter straightened up.

"You're right. I've got a scheme that will work. Come on!"

They hurried through the house toward the rear door. There they stopped. There was a mob in the alley; its fierce yells greeted them as they opened the door. They shut it again and went back in.

"Now what?" asked Hinkle. It looked hopeless. The mob was closing in on all sides of the house. Parmenter stood for a moment. There was a pounding on the front stairs of numberless feet. He hurried to the front door, pulling Hinkle with him; and the two stood so that they would be behind it as it opened. The mob raged and yelled outside and blows thundered on the door.

"They don't know us from John Smith," Parmenter whispered. "Put on your hat and coat."

His plan worked perfectly. The door burst in; its fragments swung on the hinges and splinters fell over the carpet and were trampled by a dozen yelling men, who plunged violently half way down the hall at one jump. In a moment the place was crowded. Parmenter and Hinkle waved their arms and yelled and mixed with them. No one in the mob knew what was going on anywhere except immediately about him.

They were carried on into the rooms by pressure from behind; the surge of them met the mob coming from the rear door. In a few minutes the fugitives had crowded their way out of the door and into the street. For a few moments and from a safe distance they watched the flames and the firemen. There must have been deaths in that mad stampede. Then they crept off to a downtown hotel and registered under assumed names.

Parmenter sat on the bed.

"You'd like to hear my idea?" he suggested, as though nothing had happened. Hinkle nodded his head because he was too much out of breath to speak.

"SIMPLE," Parmenter said ironically. "The human mind is a rudimentary mechanism. To think that it took me—me—three days to think of it. It is so simple that I'm almost afraid to spring it at once for fear there is some flaw in it. Let me take you through the line of reasoning by which I arrived at it, clumsily, blunderingly, whereas it ought to have been a brilliant flash through mine or somebody else's brain."

He lay back relaxed on the bed, his hand over his eyes, and talked.

"I wish to analyze the situation thoroughly; on the one hand to make sure that I am correct; on the other, to make sure that we are not passing up some good method just because nobody has thought of it.

"To stop this destruction of life and property, we've either got to catch the animal or kill it. There is no alternative, no third possibility. Is there?"

"No. Plain enough."

"They've tried to catch it. It went through the elephant chains of their trap in Lincoln Park, hardly noticing there was a trap there. Steel columns of the Elevated bend and snap under its weight. It would require weeks of special work to put together something that would really hold it. Our best bet is to kill it. Is that correct so far?"

"O.K."

"Now what are the possible methods of killing?" He held up an envelope on which he had arranged in a column:

Poison

Disease (infection)

Starvation

Trauma (violence)

"Is there anything else?" he asked.

Hinkle thought a while and shook his head.

"These are the only known causes of death, except old age. Now, some we recognize promptly as obviously out of question; for instance starvation. If we wait for that, we'll starve first. Consider disease. The only available method of producing a lethal disease, is by inoculating with some infection which works swiftly. But, if we do that, we are running the risk of its spreading its infection to the people of the city; the spread of infection might do more harm than the guinea-pig is doing. Perhaps that might be considered as a hope if there wasn't something better. Now, poison—"

"It looks as though poison were your real hope," Hinkle agreed.

"Yes. Looks like it. The police thought so too. They've tried poison-coated bullets, and the pig is still here. They've laid poison bait for it—"

"Do you think that the guinea-pig has developed some sort of an immunity against poison?" Hinkle was genuinely puzzled.

"Simpler than that. There is a quantitative relationship. It takes a definite amount of poison to be fatal. Consider strychnine for example. If you remember that it takes 1/1000 of a grain of strychnine per pound of body weight to kill; and suppose the beast only weighed a ton or two, you'd have to have a pound of strychnine. It probably weighs twenty or more tons. Where are you going to get ten or more pounds of strychnine, and how are you going to administer it?"

Hinkle sat and looked blank.

"Never thought of that," was his comment.

"Violence. Trauma. That's all that's left to us," Parmenter concluded.

"And that's out of the question," Hinkle said hopelessly. "How are you going to injure that thing?"

"To think that it's taken me three days to get the idea!" snorted Parmenter contemptuously. "If someone tried to sell you a machine as inefficient as the human brain, you'd throw it back at him.

"Trauma! Didn't I spend two years doing exactly that in France?"

Hinkle leaped to his feet.

"Artillery!" he gasped.

Parmenter nodded.

Hinkle sat down again, the hopeful look gone out of his face.

"No use," he said. "You'll do more harm to the city with the shells than to the guinea-pig."

"Say!" There was a sarcastic note in Parmenter's voice. "Do I have to tell you again that ballistics is a science? But, enough now. We'll get to work and do the arguing later."

Parmenter became a thing of intense activity. He sat at the telephone, called numbers, asked questions, gave orders, with the rapidity of a machine-gun. He seemed perfectly at home in it; obviously he had done it before. From the obscure hotel room he directed a miniature war. Here is some of the one-sided conversation that Hinkle heard:

"Alderman Murtha? This is Parmenter. I've worked out a plan to kill it. Authority to go ahead. Want me to explain it? All right, thanks for your confidence. We'll have it as soon as there is daylight enough to see by."

Another number:

"City engineer's office? Calling by authority of the police department. We want scale landscape maps of all the parks and plat maps of all the country from here to Clark Junction. Deliver them at once to the Fort Dearborn Hotel."

"Is this the Chief of Police? Has Alderman Murtha called you about giving me authority? All right, thanks. Where is the animal now? South Side? Listen. Order a dozen truckloads of green stuff, cabbage, alfalfa, anything, dumped in the empty space in Jackson Park, where the baseball diamonds are. Have it arrive there shortly before dawn, all piled on one big heap. Then lay a trail of the green stuff on in the direction in which the guinea-pig is at the time.

"And don't forget to keep your men away from that pile of greens!"

HE barked the last words out viciously. Then he called long-distance. He placed several calls, asking for Colonel Hahn. Finally the Colonel answered. Parmenter talked:

"You know of our misfortune here in Chicago—that's true, but we have just now thought of it. What's the biggest field gun you can rush over here? Right now, this minute. Yes, 150's will do the business. Two batteries. At Clark Junction. A few shells nothing! We want a five-minute barrage to cover an acre! Somewhere around dawn. You're a gentleman and a soldier. A credit to the service, sir!

"Mayor Johnson has telegraphed to the Secretary of War and the authority will come through promptly. I have maps ready for you; send a plane to the Cicero landing-field, and I'll meet it there. And two airplane observers."

He turned to Hinkle.

"Now do you get the idea?"

Hinkle slapped him on the back.

"A 150 millimeter barrage on the brute! That ought to fix him."

"Grind him up to Hamburger steak," Parmenter said grimly.

"But how will you keep from wrecking the town?"

Parmenter made a gesture of impatience.

"Not a building will be injured. The pig will be decoyed to a clear space in the park—"

"Yes, I got that idea."

"The area of dispersion for a 150-millimeter gun is about a hundred yards. That means the first shot will hit within a hundred yards of the target. They will first send over a few dummy shells, and the hits will be reported by airplane observers so that they can correct their range and angle."

"Looks dangerous anyway," Hinkle said thoughtfully. "I'm going to Milwaukee till it's over."

Of course he was not afraid. He was merely trying to carry off the situation lightly in order to encourage Parmenter. He followed Parmenter anxiously. There was little conversation during the two-hour ride to the landing-field. Three military planes were already waiting there. There was a swift conference over open maps and a few minutes' drill on signals, whereupon one plane rose and sailed away into the night, bearing the maps with it to the position of the gunners. Parmenter looked after them longingly.

"It gets into your bones," he observed. "I could hardly keep myself from climbing in with him. Just think! Four miles away the huge field guns are clanking into position; motors are roaring and the line is swinging round; men are toiling in the dark. By morning there will be a semicircle of Uncle Sam's prettiest rifles pointed this way. But, we'll forget it and hunt for a telephone."

A telephone was not easy to find in Cicero at one o'clock in the morning. They finally located one in the "L" station. Parmenter called the Chief of Police.

"Where's the thing now?" he asked. "Fine. All arrangements made? Coming."

Parmenter's eyes blazed. Again he was an artillery officer.

"Jackson Park," he said to Hinkle.

There were long waits for cars at night; a change from the elevated to the surface cars; a piece in a taxi, and the elevated again. Dawn was breaking gray over the lagoon when they arrived at Jackson Park. Parmenter raced with feverish haste to the flat, empty space where a score of baseball diamonds had been laid out for the use of the public. A string of half a dozen huge trucks was thundering away from the spot. Two loaded ones were proceeding slowly; men were throwing out a trail of cabbage and alfalfa bales behind them. In the middle of the open space was a heap of green stuff, big as a huge straw-stack.

Daylight was breaking rapidly. A bright orange blotch appeared out in the Lake; glorious streaks of crimson shot through the blues and grays of the water and sky; soon a glowing ball hung in a purple setting. For an instant the two medical men irresistibly admired the splendid spectacle of the sunrise. But in a moment they were interrupted by the noise of a couple of airplanes coming down in the open field. The pilots stepped out, pushing their goggles up over their helmets. Two motorcycle police came down the driveway.

The two aviators unconsciously saluted Parmenter, and then grinned sheepishly, because he was not in uniform. He looked so much a soldier that their action had been a natural one.

Parmenter gave orders for one plane to taxi across the field out of the way, and remain on the ground in reserve, while the other was to rise and remain in the air to direct the fire. The two motorcycle men were to locate the guinea-pig, and guide the bait truck toward it; and as soon as it had picked up the trail, to hurry back and notify him, here at the park.

WHEN the two motorcycles disappeared, Parmenter and Hinkle waited in nervous impatience. They walked much and talked little. The yellow of the sunbeams grew brighter, and it seemed an age before a motorcycle finally sputtered up to them.

"The pig is coming!" shouted the driver from a distance.

Parmenter threw a smoke bomb; the puff of yellow smoke was a signal to the airplane observer, who, by means of his radio, notified the gunners to get ready.

"Poor pig!" thought Hinkle to himself. "The city and its police, the United States Army, motorcycles, trucks, airplanes, 150-millimeter guns, all mobilized against a poor, lost, hungry guinea-pig!"

The motorcycle men stepped out long enough to tell them that the guinea-pig was near Washington Park; it had sniffed a truckful of fresh alfalfa and had whirled around to seize it. The truck was demolished and the driver had not yet been recovered from the debris. Parmenter turned a shade paler and set his teeth more firmly. The guinea-pig was now following along the train of alfalfa and cabbage that led directly to our heap in the park. Parmenter was silent as the motorcycle whirled around and dashed up the road.

A whining scream came from high in the air; there was a great splash on the beach, which threw up sand and water, left a puff of smoke behind it. The airplane was circling around in a figure "8" between the Lake and the pile of greens. Another scream and a crash in the shrubbery, not twenty yards from the pile of greens. A third heavy thud scattered the edge of the pile of green stuff.

"Good boys!" Parmenter breathed proudly. "They can still shoot."

Hinkle admitted that it was wonderful: the guns at Clark Junction four miles away, the airplane doing figure "8's," and a shot right at the edge of the pile. A fourth shot came over, and scattered the nice heap of greens all over, spread it flat on the ground. Although the shell had been a dummy and had not exploded, nevertheless the impact of it, squarely in the middle, had scattered the cabbage and alfalfa far and wide.

"Damn!" Parmenter was annoyed. No wonder. With the greens spread over an acre, how could the guinea-pig be located accurately enough to concentrate the fire properly? Someone had missed that point in the plans. They ought to have omitted that last shot.

Parmenter was swearing and shaking his fists. He started toward the scattered pile of greens on a run. Hinkle gazed dumfounded, as he began with demoniac strength to toss bales of alfalfa and heaps of cabbage back on the stack. He started over to help.

Suddenly, when Hinkle got near enough to be within earshot Parmenter whirled around, with a terrible, savage expression on his face.

"Back! Go back!" he roared.

The fierceness in his tone stopped Hinkle. He stood and stared.

"Go!" shouted Parmenter in an agonized snarl. "Go, damn you! Quick!"

Hinkle was too amazed to move.

"I wanted to help you pile it up—" he faltered.

Parmenter drew a pistol from his pocket, a huge forty-five caliber Army automatic, and pointed it at Hinkle.

"Now go!" he shrieked in a shrill voice. "Right now. And run! RUN!"

The command in his voice awed Hinkle. Despite the surging of a turmoil of conflicting emotions within him, he turned and ran.

"Don't stop till you reach the lagoon!" Parmenter ordered after him.

"Damn them and their mobs and lawsuits!" was the last thing Hinkle heard him growl.

He reached the lagoon and looked around. Parmenter was working feverishly, tossing greens on the rapidly growing stack.

Now there came a hubbub from the direction of the 63rd street entrance, the rattle of motorcycles, shouts, the crashing of brushwood, and an oppressive, heavy thudding. In a moment, half a dozen motorcycles drew up beside Dr. Hinkle. A hundred yards away, a huge, towering bulk loomed past. The great guinea-pig thundered by, its arched brown-and-white back as high as an apartment house, crashing through shrubbery, flattening out trees, sweeping aside fences and bridges as though they had been spiderwebs. It skimmed along, eagerly nosing at the ground, following the train of vegetables, piping its impatient huge, fluty whistles, ripping up lawns and driveways in frantic attempts to pick up the tiny fragments of food.

Suddenly it sighted the heap of food. It gave a gigantic leap in that direction, and ran.

"Parmenter!" shrieked Hinkle, and started out toward the busy figure of the scientist. A dozen hands seized him and jerked him back.

"Parmenter!" he moaned again, impotently.

Parmenter looked up at the yells of the motorcycle police. They were making Hinkle's ears ring with their shouts.

"Look out!"

"Come here!"

"What's the matter with you?"

Parmenter waved a light gesture to them, and calmly stepped out of the way of the gigantic rodent. The pig hungrily plunged its snout into the heap of succulent food he had prepared for it. Hinkle covered his face with his hands. The last thing he saw was Parmenter reaching out his hand to stroke the towering side of the busily feeding guinea-pig.

He also recollects momentarily hearing the roar of the airplane describing figure "8's" high in the air over the baseball park. Suddenly there was a long, wailing screech in the air, and a terrific roar. A volcano suddenly seemed to burst where the guinea-pig had been munching. Vegetables, guinea-pig, Parmenter, all disappeared in a flash. In their place was a wall of smoke, rising swiftly upward, with black fragments whirling and shooting in all directions out of it.

For five minutes, Hell roared and churned and blazed out there. The din was deafening, crushing. Showers of dirt and spatters of blood reached Hinkle and the motorcycle men. Then it stopped suddenly short, leaving a strange, painful stillness, punctuated by the feeble rattle of the airplane.

Out where the baseball field had been, a huge crater yawned. When the smoke eventually cleared out of it, there was no guinea-pig. Here and there were bloody masses of something lying about the acrid, smoking earth.

For many minutes, Dr. Hinkle stood on the brink of the reeking chasm, his hat in his hand, his head bowed.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.