RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Amazing Stories Quarterly, Summer 1929, with "Rays and Men"

NEXT to interplanetary stories, stories of the future seem to rank highest in the favor of our readers. It is natural that we should be interested in looking ahead—not only into our own lives, because they, after ell, are very much limited—but into the life of the world, so to speak. That is limitless, as we count time. Besides looking into the future through the eyes of a scientist or perhaps a mechanic or architect, Miles J. Breuer looks into the future through the eyes of a doctor. And because he is particularly adept at putting his notes into literary form, he gives us a cleverly written story of absorbing interest and scientific value.

THERE were some among those to whom I first told this story who had the idea that I was relating a wild dream produced by the influence of an unknown narcotic. But those to whom I had the opportunity to show the pink line of scar around the middle of my right thigh and the difference in size and pigmentation of my two legs, became silent and thoughtful. To those who asked me point-blank, was it or was it not a dream, I was forced to say that I do not know and cannot know. All I can do is to ask them: Is not time a function of living organisms, whose "living" depends upon irreversible chemical reactions? Any ray or chemical substance that can in any way influence the irreversibility of those chemical reactions which constitute "living" will certainly play strange pranks with what we know, as "time."

I GRADUATED from the University of Chicago Medical School in 1926 and took my year of interneship in the Lincoln General Hospital, because I was planning to settle down in Lincoln and practice medicine there. I had entered the study of medicine because I was fascinated by the scientific aspects of the work; for medicine is the science that is built up out of a score of fundamental sciences. Now that I was learning the meaning of the practical side of the profession, and beginning to realize how little of science entered into it, I looked with dismay at the life ahead of me.

A lifetime of making my living out of the distresses and misfortunes of my fellow-beings; taking their money at a time when they could least spare it; patching up the dire catastrophes that result from the blunders of the individual and of the social organization. For example, right now I have under my care two very sick men, one with typhoid fever and one with tuberculosis. The one fell ill because the community failed in its sanitary measures, the other because he is trying to fill a position in the social order to which he is not physically adapted. Ignorance, neglect, failure to see and to apply are responsible for these men's illnesses. The community or the State owes them, not merely a cure, but an apology and restitution. And here am I, a physician, struggling with these problems single-handed, and forced to take of these men's subsistence to keep my own self from starving.

Fortunately, I was kept extremely busy at the hospital, so that I had very little time for such discouraging thoughts. I maintained a cheerful front, as did the other internes. Dr. Mendenhoff, the venerable old chief of staff, had the faculty of making us young beginners feel as though we were doing a big work in the world. Bauer even managed to keep his hand in pure scientific endeavor, in spite of all the handicaps and discouragements that practical medical work holds out against scientific effort.

Bauer was the oldest of the internes—oldest in years as well as in service. He had spent some years in training as a research chemist; then his father's success in surgery decided him on a medical career. For a year he had been spending his spare time in a corner of the hospital laboratory in the effort to synthesize a more perfect anesthetic. He had a lot of gas-burettes and combustion tubes; he had drums of hydrogen sent in, and over and over again produced flasks of a very light, pungent, volatile liquid. I helped him with his efforts to work out its physiological effects on rabbits and dogs, and was very much impressed by the whole proceeding.

I had fully intended to learn much more about it from him; he had stacks of sheets covered with formulas in which the aliphatic carbon chain figured prominently. But I never got around to it. Up to the time that my finger became infected, I had gathered the idea that his stuff was some sort of a nitryl-hydrocarbon derivative. The experimental work with it demonstrated that it produced no nausea, nor any depression of the cardiac or respiratory centers, and was dissipated a few minutes after the cessation of administration. He was rather eagerly trying to study out how to manage his first trial of it on a human patient.

Then it was that I infected the middle finger of my right hand while doing a dressing on a pus case. The thing began to look dangerous, and the surgical staff member advised me to have it opened and drained under an anesthetic. Bauer was present; I saw inspiration leap into his face. He looked at me pleadingly. I felt so sick and miserable that I did not think about it twice. Offhand I volunteered to have his new anesthetic used on me, with only a lackadaisical interest in the outcome.

I rode to the operating-room on a wheel-chair, the pain from my finger throbbing through me like the strokes of a big engine; and as I climbed on the table, it occurred to me that perhaps I was conferring a favor on humanity in serving as the first subject for Bauer's anesthetic. Then the fussy little nurse laid a folded wet towel over my eyes.

Only after I had taken the first few breaths of the sweetish vapor that tingled in my lungs, did I begin to feel misgivings for having submitted to a thing so uncertain.

"If I never get out of this," I thought, "it's my own fault."

But I seemed to slide down out of consciousness so rapidly that I forgot it in a moment, and continued to breathe deeply in happy content. The last thing I remember was a vast, open, bluish airiness, and an intense ringing in my ears.

WHEN I opened my eyes I was not in the operating-room. I wasn't in my own room. But, I wasn't interested in where I was. So I closed my eyes again and lay a long time, resting comfortably. I lay on something so soft that I seemed to float.

The next time I looked, raising my heavy eyelids with great exertion, I seemed to be in a vast hall with walls of marble or some similar, almost translucent thing, pervaded by a soft twilight. My pleasant lassitude, in which I moved nothing but my eyes, lasted many minutes, during which time I observed over me a slender framework with thin glass plates in it, which covered me like some sort of exhibition-case in a museum. On an upright rod near my feet were a number of instruments with dials, a kymograph which was producing curves in red and blue, and thermometer-like scales. That was interesting. I lifted myself up to see what manner of instruments they might be, and found my head was tremendously heavy. There was a faint "clickety-click" among the instruments on the rod, and from the distance a gray-clad nurse sped toward me.

She seemed very much excited as she stopped outside the glass and looked at me. I laughed. Curious thing. Why should I laugh? It was undoubtedly some property of Bauer's anesthetic. My own laugh reached my ears as a thin, weak cackle. This served only to increase the excitement of the girl. She was young and fresh-looking, with classically regular features and a translucent complexion. Indeed she looked very pretty to my eyes. She reached down and pulled up a cord from the floor, and I felt a fresh, warm current of air on me.

Undoubtedly she was a nurse, though the cut of her uniform was different from any I had ever seen. But when I saw how the men were dressed, the strangeness of her garb ceased to trouble me. One man hurried in a few moments after she arrived; he had on some gray, flabby stuff, a jacket with sleeves to the elbows, a white ruffled collar around his neck with a flower in the front of it, and a pair of trousers that seemed to end at the bottom in slippers. The other man looked like a neatly dressed monk. He appeared a few moments later in a flowing cloak of brown. It occurred to me that cloaks lend a grace and a majesty to the movements of men, especially elderly men, that no modern clothes can give.

"He's awake!" the nurse exclaimed. My being awake seemed to be an intensely exciting matter.

The men glanced at the instruments on the rod, and the man in brown leaned toward me. The glass was gone; I was mystified as to what had suddenly become of it. Later I learned of the transparent membrane which contracted to a thick, brown ribbon when one edge was released. "How do you feel?" he said to me. Just yesterday I had been going around the wards asking the same thing of patients. I merely nodded; I did not feel like talking. He said something to the nurse and she went away. I regretted to see her go, for she was pleasant to look at. The men fell to talking rapidly in what sounded to my ears like a foreign language. Then I found that I could distinguish numerous English words in it, but could not catch the drift of what they were saying. As they talked, I fell asleep again.

When I awoke again I was in a little green room, on a gray metal bed. Over my head were several rows of bright copper rings as big as platters, strung on rods and emitting a sound. The nurse in gray stood over me, and as I opened my eyes, the rushing drone among the copper rings died away, and she swung the whole apparatus sidewise away from the bed. My mind was clear, and I felt strong and well. I sat up and looked myself over: I had to admit that I looked pretty thin. My infected finger was not painful, and looking at it, I saw that it was healed. A white linear scar remained over its palmar surface. As I was puzzling between my shrunken condition and the healed finger, the man in the brown cloak entered. The cloak had a rich, silky luster.

"What has happened to me?" I asked. Now my voice seemed quite normal.

"You're doing excellently," he replied, looking over some indicator dials at the end of the bed. I had to listen hard to understand what he said. He snapped the words off short, and put inflections and accents in unusual places. He noted my strained efforts at listening, and continued to speak with a slow and careful preciseness:

"We've put eighteen kilos on you in the last three days."

I remained silent and was tremendously puzzled. "Let us see if you can stand up," he suggested. I stood up and walked without any trouble.

"Three days!" I exclaimed. "Have I slept that long?"

THE nurse looked at me, smiled bewitchingly to herself

at what I had said, and slipped out of the room. Whatever

strange place I had gotten into, I was glad she was in it;

she lent the only touch of human reality to all this vast

mystification.

"I know you are puzzled," said the man in the brown cloak, biting the words off crisply. "We have been feeding you intravenously while you slept, and you have gained eighteen kilograms in weight. We have been trying the dynabole on you—" indicating with his hand the copper rings and the cabinet from which they swung —"rather a new thing, but it seems to be giving good results. Replaces that portion of the food required by the human body to produce energy. If we ever come to use it extensively, all the food we shall require will be to replace tissue waste. A couple of meals a week. But—" he changed his tone—"I have an unfair advantage over you. Let me introduce myself. I am Dr. Deland, Head of the Lincoln and Lancaster Hospital."

"Dr. Deland," I replied formally,

"I am glad to know you. My name—"

"We know you very well, Dr. Atwood. In fact, I think we can tell you a good deal about yourself that you do not know."

I looked at him steadily. Also, I closely scrutinized everything in the room. Certainly it was all elaborately prepared. Who he could be I could not imagine. But there was no question that I was the subject of some kind of a huge practical joke. The Rho Sigma, Tau's had done such things in our old undergraduate days; and this was another stunt worthy of the old gang. Even to the lovely nurse! Whom in the world had they gotten to play her part? She had certainly taken me in.

"Go on with the game," I said jocularly. "This looks like the best one yet, and I'm ready for all you've got. But I'd give a dollar to know who you really are."

He regarded me for a long time in silence. The kind, solicitous benignancy of his attitude was certainly acted out to a finish.

"What's it all about?" I said again, gaily. "Now that my finger is healed I'll take on the bunch of you. Let her rip."

He shook his head and there was a solemn expression in his face.

"I know about your finger," he said. "It healed two hundred and fifty-four years ago. You have slept from the effects of nitrylcylene for two and a half centuries!"

"Good boy!" I applauded. "I knew you fellows had something good, and I'm not disappointed."

"I have been trying to spare you the shock," he said, half to himself; "yet perhaps that will be the best—over and done with quickly."

He turned to me.

"Just put on some clothes and come with me."

He pointed to a folded pile, and noting my puzzled regard, helped me put them on. There was a baggy pair of trousers ending below in comfortable shoes, and a blouse with a ruffled collar. They were tough and strong, but thin and light as paper; they hung loosely in silky folds that were cunningly worked into the cut of the garment. Clever, indeed!

Then he led me down thirty yards of green corridor. We went up a silent automatic elevator, and later reached the end of a short, gray passage. As he opened the door, a rushing roar rolled into the peace about us. The wall of the building was two feet thick; the door opened on a balcony, and through it I could see brilliant masses of buildings and huge shapes moving majestically high in the air. My jocular attitude collapsed, and left me amazed and trembling.

"Behold Lincoln of 2180!" said Dr. Deland quietly.

I STEPPED out hesitatingly. The magnificence, the glory, the teeming activity of it struck me suddenly, hard, like a huge flood of water. I grasped the rail for support, for it made me feel weak. "Lincoln!" I gasped.

We were on the roof of the hospital, on the south side of a little tower-like structure, a good hundred feet above the street. Two hundred feet away were the roofs of the buildings on the opposite side of the street, great, graceful structures of a bright, glassy material. The one immediately opposite had a dozen huge, white columns in a row, and farther down, a greenish, translucent structure was a wonder of great interlacing arches. Hundreds of enormous buildings of different degrees of gleaming translucence, in tints of pink, blue, green, and gray were spread before me, with domes, porticoes, huge statues, and graceful little towers. All of them harmonized in respect to size, style, and tint; the city at which I gazed was not a hodge-podge of individual buildings; rather each building was an essential part in a unified design.

The individual buildings had a tendency toward a pyramidal shape; high up there was more space about them than on the ground. Toward the north there was a general decrease in the size and number of the buildings; while to the south and east they grew higher and more splendid, until in the distance, apparently in the center of the city, they were surmounted by a huge, bright shaft, towering into the heavens high above the rest. That tower—I had seen it only in architects' drawings, but I recognized it with a leap of the heart. That one familiar thing among all this strangeness had only been a dream, a matter of blue-prints, when I fell asleep two hundred and fifty years ago; and here it stood, massive and beautiful: the world-famed Nebraska State Capitol building.

There were huge things in the air, great fish-like affairs that rose, circled, and sailed away; and countless little darting ones, scurrying hither and thither, up and down; and a deep, droning hum, not unpleasant to listen to, came from all of them. The rush of traffic came up from below, and I moved closer to the railing to look down. Again I clutched the railing in astonishment.

The street looked like a river, crowded with people dressed in light tints of various colors, and an occasional one in a dark shade. Streams of them poured swiftly by into the distance. At first it puzzled me. Then in a moment I understood. The street itself moved in longitudinal sections, each half in an opposite direction; at slow speed near the edges, while the middle sections which were also the highest, moved so swiftly that they seemed a continuous stream of changing, blending tint. Next to the buildings was a stationary strip on which people walked, gathered in groups, and sprinkled into and out of the buildings. I let my eyes follow one man in pale orange as he came out of a doorway, crossed the stationary walk, stepped up on the moving section and moved slowly eastward; then he stepped up from one section to the next, each time moving more swiftly, until I lost him in the distance, whirling away on the middle section.

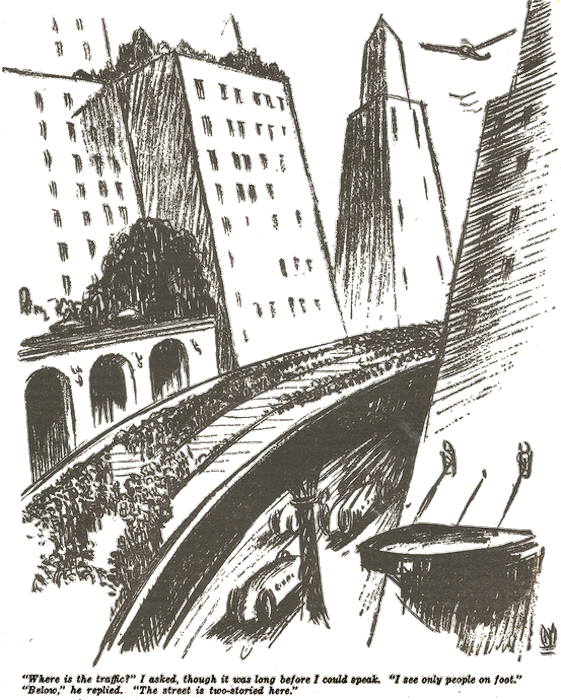

"Where is the traffic?" I asked, though it was long before I could speak. "I see only people on foot."

"Below," he replied. "The street is two-storied here."

I could not speak any more. Either because of the violence of the shock to my emotions, or because I was not yet in as good physical condition as I had thought, I was trembling from head to foot. My body began to sag until I thought I would fall. Dr. Deland supported me, and signaled for a little self-propelled cart, which conveyed me back to the gray bed in the little green room. Down in the quiet and subdued dusk of the chamber, that dazzling, whirling, magnificent spectacle still shone before my eyes.

I GAVE up my last effort at defending myself against

the realization of what had happened to me. It was a fact

that somehow I had crossed that awful gulf of years. It

was a fact that I was alone; all my friends, who had made

life worth living, were gone, mouldered and forgotten,

generations ago. I was alone in a world, the terrific

complexity, speed and high pressure of which were glaringly

obvious to me at the first superficial glance. I could

imagine how an upper Congo native would feel, if he were

suddenly set down in the middle of Broadway.

What would I do here? How could I ever find my place in this seething world? What would become of me in such a merciless maelstrom? Things had looked discouraging enough for me back in 1926, even though I was then thoroughly prepared for my function in the world. To have the difficulties before me suddenly increased a thousandfold dismayed me utterly. I was hurled into a despair so blank, so devoid of any glimmer of hope, that I lay motionless and face down on the bed, perceiving nothing, caring nothing.

Curse Bauer and his anesthetic! Then came the realization that Bauer was no more, not even a memory, and my misery was renewed. I only hoped that I could be eliminated quickly.

I felt a gentle touch on the back of my head. It was a soft little hand. I turned my head moodily, and saw the nurse standing beside my bed.

"It will not be so bad as all that," she said in a voice full of interest and sympathy. "Just think! they have been waiting for generations for you to wake up. They will take care of you well. You will be a special. Oh, what a jingle time for you!"

I jerked myself to a sitting position on the bed and stared at her. "Are you people mind-readers?" I exclaimed. She looked at me a moment and then continued. Obviously she had not understood what my question meant.

"You are lonesome," she said kindly. "I knew you would be. The doctors never thought of that." She smiled. I noticed that her eyes were brown. She sat by me a while and did not speak. I asked her what her name was.

"Elite Williams," she replied with another smile that noticeably brightened up the universe.

Somehow I felt better. Although Dr. Deland seemed to be trying hard to be kind and hospitable to me, yet everything he said and did merely emphasized the gulf between us. But this girl, so lovely and so capable, really understood. How much it helps if only someone understands! When she got up to leave, I did not protest; I knew she had her duties. But I felt desperately that I could not let her go. I wanted her to sit here by me forever. With her sympathy, perhaps I could manage to hew me out a place in this world after all.

I DID not recognize the ingredients of the supper that was brought to me, but its taste was very pleasing. During my subsequent meals it was only rarely that I was able to tell what I was eating; there were various pleasantly colored and flavored cakes and gruels and gelatinous dishes, and many fluid and semi-fluid ingredients. The next morning, Miss Williams, who was attending to some apparatus in the room while I breakfasted, cheerfully informed me that I could have my breakfast intravenously if I preferred.

"Do very many people eat—or get their nourishment that way?" I inquired.

"Not very many. We use it sometimes for sick people; and for well persons when they are busy and don't have time to eat."

"Wow! what a world!" I thought to myself. "Don't even have time to eat!" Like a pang, the depression of yesterday swept over me when I thought of it. Instinctively my eyes sought comfort by resting on Miss Williams as she worked about the room at things unintelligible to me.

She was tall, nearly as tall as I, but gave no impression of tallness; rather, she gave an impression of grace and vitality. She moved with perfect ease and a suggestion of buoyancy about her that made her seem to radiate a glow of fresh, vigorous health. She had brown hair with a bright sheen on the fluffy parts of it, done up lightly about her head; and her eyes were active and merry.

A nameless thrill filled me as I gazed at her perfectly proportioned face, her clear skin, her supple movements. There was something about the beauty and health of her that was different from the girls of my own time. I could feel my heart going wild and my head dizzy, though I liked the sensation.

Then Dr. Deland came in and spoiled it all. I wanted her to myself all the time, even though she was busy and hardly conscious of me. But I determined, for her sake, to buckle down and get interested in things, to understand them, and to make something of myself among these people. Back over Dr. Deland's shoulder I saw her look at me and nod her head in approval.

I turned to listen to Dr. Deland; and then for a moment my mind stopped in amazement. Her expression and attitude had shown approval of my determination to throw off my discouragement. But how could she have known what I thought?

I had to let the problem go for the moment, for Dr. Deland was talking.

"... since you are trained as a medical man, you will enjoy seeing the medical things first, you will want to become acquainted with our twenty-second century civilization. Come with me; I have some things to show you today."

Mutely I followed him to his office. There sat the younger man in gray. I judged that he was also a medical man, in some junior capacity. He was talking to a keen-faced, slightly gray-headed man in a pale violet cloak, about whom the most noticeable thing was a busy, brusque air. Dr. Deland introduced me.

"Mr. Shepard," he said. "Mr. Shepard makes airplanes."

Mr. Shepard looked worried.

"That's a lot of time to lose," he complained. "It will ruin me. Competition is mighty close nowadays."

"We can do it right away," Dr. Deland patted him on the back consolingly. "To-morrow is Sunday, and Monday morning you can be back at your office at work."

Mr. Shepard followed the nurse who came after him, shaking his head and muttering with worried anxiety. Dr. Deland called after him:

"It will do you good to forget your business for a couple of days."

Then he nodded to me and led the way down the corridor.

"Operating room," he informed me in the terse fashion to which I was beginning to grow accustomed.

I was keenly interested in the operating room. It was large and gray, with many pieces of apparatus ranged around the walls, reminding me vaguely of X-ray machinery. However, the operating-table in the middle looked familiar, as did the preparations of the surgeon and the nurses. Mr. Shepard was wheeled in, swathed in white.

"Appendix!" said Dr. Deland. His snappy manner was incongruous in a man who looked so old and kindly. "Must come out."

"But—" I stammered. "You told him he would be back in his office Monday—day after to-morrow!"

"Yes," sighed Dr. Deland. "Life is too busy, too strenuous nowadays. We cannot spare much time to lie around in bed."

Noting my stare of amazement, he continued, smiling: "Let's see. In your comfortable and leisurely day an appendectomy required two weeks in bed and another month of rest—a tremendous amount of time to waste.

"Now, we first of all eliminate the shock by means of our anesthetic, which has no after-effects of its own. It consists of a generalized nerve-block caused by a form of radiant energy electrically produced, and known as Theta Violet 60. Then we have various methods of accelerating wound healing. In this case we shall inject tethechrome for the deeper structures, and expose to Kowalski rays for the skin and fasciae. You can stand by and watch it grow together. By this time to-morrow, healing will be complete."

I stood there and watched the young man in gray wheel up a big cabinet and attach cables to the patient's chest and feet; I watched an appendectomy performed in just the way I might have done it myself; I saw them inject the wound with an intensely red substance and sew it up with a little machine like a hair-clipper; and all of the time my mind was troubled with the thought that this business man was too busy to spare a day and a half for the purpose of saving his life from an abscessed appendix. I thought of the whirl of people in the street and the throng of them in the sky. They themselves complained that it was strenuous. How then would I find it?

THESE thoughts buzzed in my head while Dr. Deland led

me around most of the day and showed me things in the

hospital; and I saw the things he showed me as in a daze.

I have only a confused recollection of them. The endoscope

was rather a wonderful thing: a sort of little telescope

that made its own incision through the patient's body wall,

and explored around inside the liver or lungs and took

photographs of the gross and microscopic structure within,

and then closed up behind itself the wound it had made. I

saw a patient receive an injection of some opaque mixture

in the blood and then watched on the fluoroscope of an

X-ray the streams of the opaque fluid going through the

valves of his heart, and filtering through the capillaries

of his lungs and kidneys. I saw a man with a terrifically

red and swollen knee; they swung an affair like an

automobile radiator over it, and I watched it grow pale and

relax in the course of twenty minutes.

"We can control the secondary induced radiations so accurately that we can regulate the dose to kill one form of life and not another," Dr. Deland explained. "When we have an infection, we determine what organism is present, set the specific dosage for that, and the patient's tissues escape without any effect whatever. Then the dose is altered so as to decompose the products of bacterial growth into harmless substances."

"But there are so few patients here," I remarked. "The hospital is two-thirds empty."

"This thousand-bed hospital was built a hundred years ago," he explained. "At that time it was appropriate for the Lancaster District. To-day it is triple what we need. There is less illness. Infections are prevented; accidents are prevented; people are born healthy and are trained to remain so. We have proportionately many more doctors and nurses than you had in your day, and plenty of work for them to do. But as their work is largely preventive and educational, we have fewer sick people."

I went back to my room, wearied mentally as well as physically. The methods of diagnosis, treatment, and prevention that I had seen were far beyond anything I had ever dreamed of. They made my head swim. Furthermore, they made me realize that with all of my eleven years of elaborate training for the practice of medicine, I was here perfectly useless. My medical training, the most modern and up-to-date that I could get, made me about as valuable as a Kickapoo medicine man. I was useless and helpless, good only for common labor, in a civilization where medical and surgical operations were probably all done by machinery.

"Is our world as terrible as all that?" Miss Williams asked me, as I came into my room and threw myself on the bed. "Or were all of you so sad and gloomy all of the time?" She had a tray of food waiting for me.

I threw off my gloomy mood.

"Naturally, things are more complex now, and they confuse me," I explained. "I'll learn, and I'll get over it after a while. I just hope that you will continue to be kind and encouraging to me."

"I'll do everything I possibly can to make things easier for you," she said; and her eyes spoke more eloquently than her words, of the generous impulses in her warm little heart.

"I'm grateful to you," I said. "You can never know what your kindness means. With your sympathy, I can do anything. I can get anywhere." I held out my hand. She looked at it for a moment, and then exclaimed: "Oh, I know! We've all been studying the history of your times since you awoke. A handclasp meant friendship."

She gave me her hand, and something within me made me grip it hard and desperately. Then calmly I set about eating my supper.

While I was eating, Dr. Deland breezed in. It always seemed that he did things in a most undignified way for a man of his age and wisdom.

"You are well enough now," he announced, "so that it is not strictly necessary for you to be in a hospital. My home is far enough away from here to get you out of the noise and pressure and confusion until you learn a little more about our ways. Come to my home with me; you shall live there as long as you wish; until you become established in Lincoln as a citizen."

EAGERLY I anticipated my first venture into the streets, and I was quite excited when we stepped out of the hospital on our way to Dr. Deland's home.

The street gave an impression of intense activity. The streams of people in variegated colors shooting swiftly past each other, the subdued rattle of the moving street, the rumble of the traffic from below, and the humming from the moving shapes in the sky, all made me feel rather uncomfortable. The people stepped deftly about the moving street from one section to another, but I came very near losing my balance when I stepped from the second to the third with Dr. Deland. After that I stepped so gingerly and balanced myself so carefully that people were inclined to turn and look at me. We rode a short distance, crossed the street by a graceful little archway overhead, and descended to the traffic level.

If it was uncomfortable above, it was doubly so here. The street was a wild torrent of huge, rumbling vehicles, which with the moving ways made such a din that we had to shout to each other to make our conversation heard. The dim daylight that filtered down through the translucent material of the moving street was reinforced by rows of big, white lights. I noted that the noise of the traffic was due far more to the heavy loads than to the operation of the machinery. Vehicles varied all the way from huge trucks hurtling like a house down the street on small, solid wheels, to swift, spidery passenger cars with wheels so big that they obscured the rest of the car.

We went into a garage for the doctor's car. He lived about twenty miles south of the hospital, and drove back and forth. It was a bright affair. It seemed to have been made of aluminum, with six-foot wheels and huge pneumatic tires. The body, with comfortable seats, was hung very low.

"Expensive toy," remarked Dr. Deland. "New solar power unit. Most of those cars"—waving his hand toward the traffic—"are run by cellulol, a distillate from the kashawa plant. But likely, in another generation all vehicles will be run by solar power."

As I was eager to see the machinery, he showed me a small box behind the seat. It contained a great many glowing white buttons on little partitions, and that p was all.

"But the engine and the transmission? Where are they?" I gasped, having expected to see some wonderful refinements along those lines.

"I'll do my best when we have a little time," he replied, "to explain to you the principle of direct traction without I the intervention of rotary motion. You wasted a lot of power that way in your day. But that is all the machinery there is in this car."

He drove out into the street, which was also divided into sections, the swiftest vehicles having the middle sections. We soon came out under the moving street and into the open. Here heavy trucks and freight vehicles-were less numerous and swift passenger cars predominated. The sidewalks along both sides of the street were in motion. The buildings were not so high here as in the business portion of the city; they were loosely spaced and interspersed with lawns, trees, and flower gardens. This quarter contained mostly hotels and apartment buildings.

I could not help being impressed with the harmony. In size, style, and arrangement of the buildings; a glance down the street revealed, not a row of individual buildings, but one beautifully consistent plan, into which each building fitted as an essential part.

"Let us stop," suggested the doctor, driving into the outer section, "while you look back."

The sight that met my eyes made me catch my breath. In the foreground were gardens and groves and palace-like buildings, as though taken from some fairyland city and set up on a stage. This spread in front of me for a mile, and out of it, like some towering mountain, rose the business district. First there was the outlying range of plain, massive buildings for storage and wholesale; then terrace upon terrace of increasing height, intricacy, and grandeur; here a row of immense domes; there a forest of little spires; toward the center the towering office and department buildings, and rising above it all, the white-and-gold tower of the Capitol building.

"What a city!" I sighed. "In my day men dreamed of such things, but did not consider them humanly possible. How does Lincoln rank among the cities of the United States?"

Dr. Deland smiled.

"Beautiful it is," he said. "It is widely famed for its beauty. But in size it is a mere country village. You shall soon see other cities, and you will find no two alike. You shall see Chicago, the many-storied city, where for a hundred square miles there are four, five, six layers of busy streets one above the other. You shall see New York, the city of magnificent heights; where there are offices, stores, and public assembling places hundreds of feet below the surface, in the rock; where there are viaducts connecting the floors of skyscrapers a thousand feet above the ground; where transportation in a vertical plane is as extensive and important as in a horizontal one. You will be interested in Rockefeller, Kansas, the 'artificial' industrial town that was built all at once like a single house; whose ground level is all free for traffic, whose rooms, offices, and inside spaces are all found above the level of the ground floor, while the roof of the city is one wonderful park."

In the meanwhile we slipped into the middle section, and I had a ride such as I had never had before. The surroundings melted into a blur, and I held on and gasped for air. The doctor leaned back nonchalantly at ease. In less than fifteen minutes from the time we had climbed into the car, we were at his home.

On the way I was able to note that homes fringed the highway from one to three deep, and the doctor told me that people drove as far as a hundred kilometers daily to their work. Behind the houses I could see growing fields; forest-like growths of the kashawa plants predominated. These grew from fifteen to twenty feet high every year, and from them was distilled a sort of fuel alcohol; also a paper was made from them, used for the manufacture of countless articles, including the clothes we wore.

I CANNOT remember everything connectedly. My next

recollection is that of sitting at the doctor's dinner

table with his family that evening. There were his wife

and four children, and I was surprised when I heard that

two daughters were married and not living at home. I

had supposed that in this advanced era, I should find

small families. The features of all of them were regular

as models. I recollected the people I had seen in the

streets. All of them had been perfectly proportioned in

face and figure; they all had a freshness and vigor, their

bodies were of a size and a power, and they moved with a

robust buoyancy that was rare in my own day. There were no

discrepancies in size, no cripples, no ugly faces. What had

happened to change the human race thus, in such a short

time?

Dinner had been ordered from the city by telephone; when the mistress of the house gave the signal that she was ready for it, a buzzer sounded and a circular panel in the wall opened with a swift rush like a powerful sigh; and from the opening a cylinder dropped into a padded basket, whereupon the panel clapped loudly shut. Out of this cylinder the dinner was put on the table.

Mrs. Deland beamed with happiness over her children. The eight-year-old boy was in uniform, and called himself an "Argonaut." This was a voluntary boys' movement which had for its object self-discipline in preparation for leadership in adult years. At this tender age, when children should have nothing on their minds other than care free play, this stern and implacable civilization was reaching down and beginning to mold their growing bodies and minds into slaves for its strenuous wheels.

The four-year-old boy was let very much alone to do as he pleased, but was talked to gravely and precisely, as though he were quite grown up. The twelve-year-old girl did not say much, but spent a good deal of her time buried in some kind of book.

The oldest girl present was sixteen. Her father pointed to a badge she wore, a cherub in blue.

"Estryn has just been rated, and received her badge yesterday. Blue is the highest color, and we are proud of her. She has chosen the vocation of motherhood. It is the most important one there is, and the integrity of our whole social structure depends upon it."

I was a little embarrassed, but the girl beamed happily. I finally ventured to ask:

"Has the bearing of children become a specialty, then?"

"Not the bearing, but the rearing. In practice it works out that the two coincide fairly closely. If a woman who does not have the motherhood training bears a child, she must give it up to be reared by properly trained persons; or she must take the seven years of motherhood training. If the State has already given her one vocation, the second must be at her own expense.

"In your day you did not educate your children. You sent them to school to get them out of your way. Then you slaved, paying for governments, insane asylums, wars, and courts, to patch up your original blunder. Today the State asks no other work of the mother than the training of her children. But that is so important, that in preparation for it, the State gives her a more accurate and through training than it does to any other class of producers.

"You lived about the time of the German War. Perhaps you were involved in it yourself. And you wondered if there would be any more wars. There were plenty more and greater ones, until man found out how simple and easy was the way out—not by ridiculously impotent peace congresses, but by training the children. Leblane, the Bordelais, with his International Pedagogic League in 1999, stopped war, which a thousand silly peace congresses had failed to do.

"It was very fortunate that he came when he did, for the advance of science continued in spite of political stupidity; a few decades later the destruction of human life was made so easy by the discovery of new forces, that without the new education, civilization would have been totally wrecked in a short time."

He studied me a moment quizzically and then shook his head.

"Don't you see that?" he inquired. "Look. Under conditions of savagery and barbarism, it required a good deal of hard muscular work to kill a man; it was good exercise and was not so very dangerous. Today, the pressure of a button with a finger will kill a thousand or a hundred thousand men. Today it is so easy to kill a man secretly, safely, at a distance, that if men wanted to kill, all laws, all governments, all police would be powerless to detect the criminal or to keep order."

I thought a moment in silence.

"I've spent most of my time in thinking about the saving of human life," I remarked; "but it seemed to me that during my day the ultimate refinements in the destruction of human life had about been developed."

"Your developments were still very crude," he said with a smile; "today we have a dozen methods infinitely more terrible than anything you ever dreamed of. For instance one of the simplest is the form of radiant energy known as the Sigma Parabolic. Any elongated piece of iron-containing metal, slipped into any kind of wire coil or solenoid of fair inductive capacity, and wrapped in detractive such as is found on pocket telephones or flashlights, will electrocute a man at a thousand meters, instantly, silently, invisibly.

"With powers like that abroad, where would your unorganized, untrained, emotion-controlled civilization of the twentieth century be? It wouldn't be safe for a week. How can you control power like that, except by the most rigid training of the emotions from the earliest childhood?"

"If we had only had that thing in the Argonne!" I thought to myself. But fearing that the remark would be lost on the doctor, I refrained from saying it aloud.

BUILT into the wall of their living-room was a cabinet affair with a ground-glass screen about a yard square. The family sat in the evening after dinner and watched a play that was being transmitted from a studio in the city. I derived a great deal of pleasure from watching the action in full colors on the screen and hearing the actors' voices and footsteps, and the sounds of their furniture and dishes. But I could not follow the play. It moved too rapidly for me and I soon gave it up. Dramatic technique must have changed radically, for the action to me was but a confusion and a babble and a running back and forth; I could make neither head nor tail of it. So I sat, watching the flickering, active, colored figures that talked and laughed and wept, and gave myself up to my own thoughts.

This was Sunday evening. I wondered if there were still churches. If so, the services could probably be transmitted over this "news-machine" as they called it. Perhaps that was all right if you got used to it; these people seemed to derive as much thrill from this play, as I had ever gotten in any theater on Randolph Street. In fact, they seemed a happy people; not only this family, but all the people I had seen. Among all of these uncanny mechanical things, the people lived a joyful, satisfied existence, if I could judge from their talk and from the gladness in their faces.

I suddenly realized that the play was over, and printed words were running over the screen; A catalogue of news events, plays, music, lectures, and all sorts of available entertainment, with figures for tuning into them. To please one of the boys, a sport event from the Gulf Coast was selected, and I was amazed to see a contest between sailing yachts, and a horse-race on the sandy beach. It gave me a curious comfort to think that horses still existed. Then there were pictures of jewels and women wearing them, a sort of "style show" from New York. The legend called them synthetic jewels, but they were more beautiful than anything I had ever seen. When the jewel picture was over, Dr. Deland's wife did a little tuning on the apparatus, and gave an order from where she sat to a dealer in New York, who assured her that the jewels would be delivered to her by pneumatic tube the following evening.

By bedtime my head was spinning from the marvels I had seen. In a pleasant little bedroom the doctor showed me how to get my bed ready by opening a window and pulling a lever. The bed and bedding had been turned up on edge all day and hung out of doors; a single movement of the lever brought them in and arranged them for sleeping. And all of the housekeeping was patterned on this same plan. Walls, floor, and ceiling were hard and smooth, and what little cleaning they required was done by a compressed-air machine. There was a soothing absence of bric-ŕ-brac and decorations. I was especially interested in the books in transparent, hermetically sealed cases, which could be opened by sliding a lever.

I cannot shake off the impression that I was at Dr. Deland's house for several weeks. As a matter of fact, I was there only one Sunday. Not that there was anything wrong with the hospitality of the family. Their treatment of me was certainly perfect in every psychological detail. In fact, as I recollect it, everything everybody did to me, during my stay in the Lincoln of the twenty-second century, was psychologically correct. Everybody did the reasonable, common-sense thing, which in the end was calculated to lead to the best practical results for all concerned. This contrasted strangely with some of the foolish, impulsive things that I did when I was there.

Dr. Deland's hospitality consisted in making me acquainted with his family and his home, and letting me atone to do as I pleased. The house was set in the middle of a couple of acres surrounded by hedges. Glimpses of other houses could be had through the foliage. A hundred yards back was the jungle of kashawa plants. Swift vehicles shot past along the road like streaks of lightning. Toward the west, one strange aerial vehicle after another sped by in the distance, all in the same direction. There lay one of the air-lanes. To the north lay the city.

I could see no hint or sign of it on the northern sky, but I felt it was there. I felt it was there so strongly that it ached. By the middle of Sunday forenoon I thought I would go mad. I walked about the grounds and gazed toward the north, and walked again. The strangeness of everything was uncomfortable and the inactivity was maddening. It would have been a welcome relief to have to work, to hunt for my living, or to fight for my life.

Even the girl's music failed to comfort me, though I remember it as something vastly stirring to the emotions; disquieting because I could not understand how it was produced nor what it was doing to me. Obviously, marvelous things had happened to music during two and a half centuries. I sat and watched her for a while, seated at a large keyed instrument; and then I fled outdoors.

I wanted to be doing something. I wanted to be working.

At least, that is what I thought at the time. Now, as I look back, I realize quite frankly that work was not really what I wanted. I did not understand then that work merely symbolized a method of getting back to the only girl who had ever caused me to look a second time at her. I only knew that I was very lonesome and very miserable'. If I insisted on working, they would have to put me to work around a hospital, because that was the only thing I was good for. As there was only one hospital in this "district," that meant that I would again be near the brown-eyed nurse, who could understand me and sympathize with my plight. All this hospitality, all these marvels meant nothing to me. I wanted to be near her and hear her voice. I longed desperately to be at the hospital. I tramped savagely around on the velvety, grass; I wanted to be at the hospital.

AT noon I told the doctor that I could not bear longer

to presume on his kind hospitality; that I was ashamed of

myself for permitting someone to support me when I was able

and should be doing something useful; that I was eager to

assume responsibility for myself and get at some kind of

work. He pondered thoughtfully over what I had said and

assured me that I was most welcome in his house; and that,

if he were in my place, he would not miss the opportunity

to relax a while and take things easy. Life was strenuous

enough anyway.

In the afternoon I stood and gazed up the road to the north. I was restless and miserable. I didn't belong among these people. They seemed to enjoy this world and this life, but they were made of different stuff; human nature must have changed. There was more intellect, less emotion. I didn't see how I could stand it here.

I walked down the lane between the adjacent grounds, to the east where I could see the gleaming kashawa leaves in the distance. The dark glossy green of the leaves and the cool depths of the thicket looked comforting. As I approached it, the thicket loomed high like a forest, a wall twenty feet high, of rich green, interlaced with the reddish tinge of the stalks. The leaves looked like the leaves of the castor-bean plant, but they grew on huge, branching stalks as thick as my arm. I walked in under them.

The cool, mysterious depths of the thicket attracted me. The ground was soft and perfectly clear of any undergrowth. I wandered on into the pleasant twilight, for the sky was completely obscured by the big leaves. I found a sort of exhilarating comfort in the presence of the green things, and a satisfaction in the physical exertion of walking briskly ahead. My strength was returning rapidly and it felt good to be moving.

I swung onward, feeling rather more cheerful than I had since morning, now dodging a low branch, now pushing aside a leaf that hung in my face, and really finding some hope for myself in this amazing world. I wonder if I am the only one so constituted as to be depressed when in the midst of nothing but masonry and machinery, and instantly cheered in the presence of Nature and her handiwork? Can man ever get completely away from his dependence on green things, both for mental and physical sustenance? I wondered, and felt grateful for this opportunity, after my recent experiences. Perhaps, if I could get out occasionally into a wilderness like this, I might endure life in this world of marvelous machines and still more marvelous human relationships.

The human relationships were indeed more marvelous than the machines. For, the Sigma Parabolic Ray came into my mind. Think of it! A world at the mercy of any man who chose to destroy it, and yet human nature was so trained that the world was perfectly safe!

A faint aromatic fragrance hung on the air, vaguely suggestive of cinnamon. I surmised that the plants smelled that way; but I enjoyed the exhilaration of a swinging, uninterrupted walk so thoroughly, that I postponed making sure. It had been a long time since I had stretched my legs so lustily. Finally, after I had been going at a good gait for some ten minutes, I stopped and broke off a leaf. The aromatic odor of the broken off portion was quite strong and suggested cinnamon. The stem of the leaf was dry and pithy, like a cornstalk or an elder branch. I looked about me. Far into the distance stretched the vistas of crooked, branching stalks, fading into dimness, a soft, confused dimness in the distance. A faint rustling came down from the tops, but down here it was still. Not a glimpse of daylight anywhere.

Regretfully I started back.

I walked along in a pleasant frame of mind, cheered up by my contact with Nature. Almost gaily, I traversed miles and miles of forest. It was some time before it dawned on me that my return trip was taking longer than the journey inward had required. And still there was no daylight, no visible sign of the open ahead of me.

I stopped, and a sinking sensation swept over me.

I was overwhelmed with the realization that I had carelessly plunged into this unmarked jungle and was lost.

"I'M sure I did not walk directly away from the edge," I thought to myself. "I must have walked more or less parallel to it. So, if I go at right angles to my present course, I ought to find the edge."

I set off at right angles to the course I had just followed; but it was a hopeless feeling. Which was right angles? Already I was not sure just which way I had come last. All directions looked alike among these crooked stalks. And I was beginning to feel fatigue. After all, I had not yet gotten back my normal strength and endurance. For a while my momentum carried me on, and then I sat down to rest.

The ground was soft and the air was warm, almost hot. I noted that clothes were lighter than the clothes that had been worn in my time. Had the climate become warmer then? It seemed that to grow this luxuriant profusion, an almost tropical climate would be necessary. I recollected a statement I had once heard that the carboniferous era was possessed of a warm climate because of the high percentage of carbon dioxide in the air, which prevented heat loss from the earth's surface. When the luxuriant vegetation of that period had fixed the carbon of the carbon dioxide into its carbohydrate molecule, the weather had become cooler. But now that during the two hundred and fifty years of my anesthesia, immense quantities of carbon dioxide had been returned to the atmosphere by the combustion of carbon fuels, its percentage in the air must again be sensibly higher, and the sun's heat must be more readily retained therefore.

However, a little panicky feeling began to steal over me. Just how serious was it to be lost in this jungle? The idea struck me that I might orient myself by climbing one of these trees. They did not look very strong, but I was desperate. I put my foot in a crotch and tried to raise myself up. The branch broke flimsily off at once; it could not support a tenth of my weight.

I tried again. I broke off all the branches around the big main trunk and tried to climb that. It was six inches through and looked as though it ought to be strong enough to support me. But I was not two feet off the ground before it collapsed with me.

I sat down again. Certainly, this field could not be limitless. No matter in which direction I went, if I kept on I ought to come out somewhere; somewhere where there were people. And people would help me get back to Dr. Deland's house. I leaped up and started out energetically, for this place might be several miles long and I might be setting out along its longest diameter. I would have to hurry to get out before night overtook me. Already I could imagine darkness, hunger, and thirst overtaking me.

Desperation drove me on in spite of leaden feet and a certain difficulty in getting my breath. The monotony of the endless repetition of crooked branches was deadening. The reddish stalks and dark green leaves began to numb my brain into a kind of coma. But I pushed doggedly on, confident that if I kept at it I must perforce emerge somewhere in the open. Then I would have no real difficulty in getting back to Dr. Deland's house. The fact that I had no sort of money with me to pay transportation worried me for a moment, but not seriously. I kept hurrying forward, past the forked arms of the trees; and in the dim distance the crooked tracery hurried along with me. It began to seem that I had been plodding through this endless jungle for hours and days....'

Then I came upon the broken tree. There were the branches I had broken off, the trunk that had collapsed with me, my footsteps in the soft earth, and the mark on the ground where I had rested. I had simply traveled in a circle!

I dropped to the ground in dumb despair. My mental state was so curious that I remember it to this date. On the whole I cared little whether I lived or died. Only when I thought of the gray-clad nurse, I felt a little pang of regret. But this world was no place for me, and what was the difference? But—to survive so miraculously for two and a half centuries, to see marvels undreamed of during my time—and then to perish of hunger and thirst in a jungle! I was disgusted. The ignominy of it! To be ground in some huge machine, to be crashed in a flyer high in the air, to be annihilated by some strange ray—that would have satisfied me. But to get blunderingly lost and die this way was too disgustingly primitive. That belonged to the Stone Age. Again I jumped to my feet, determined to find my way out somehow. The human mind is a queer bit of apparatus.

But I didn't get far. A pleasant sort of lassitude began to steal through my limbs. After all, my feelings of hunger and thirst had been imaginary. It had been only a short time since I'd had a good meal; and since then I had walked briskly and gotten tired. The weather was warm. Before I realized it, I had slipped to the ground and dropped off to sleep.

"OUGHT to be near here somewhere," said a brisk, muffled voice. I awoke, rubbed my eyes, and stretched my stiff limbs. It was pitch dark.

"Let's sit down here. I want to check my figures," said another voice. In a moment it continued:

"It can't be far. Two graph lines from the microphone direction-finder cross at this spot. We stopped the car right over the indicated spot, and there it hangs, square above us. I checked on three leads, his watch-tick, his heart-beat, and his breath-sounds; and they all agree. He must be within the radius of a dozen feet of where we sit; and he must be still alive, though probably unconscious. The galvanometer deflections are feeble, but steady.

"The carbon dioxide column is the most accurate. Through the oxygen exhaled by all these plants, the carbon dioxide exhaled by a human being is plainly visible in the spectrophotoscope; and just before dark we located that in the middle of this square. He's bound to be near by."

A bright light swept about, throwing a few crooked trunks into bright relief against the black background. I sat up, the significance of the words penetrating slowly into my dazed consciousness. They had located me by some very refined scientific methods. I staggered to my feet and went toward the source of the light.

"See!" said one of the dark figures with calm satisfaction, and in a moment the other was talking into a telephone.

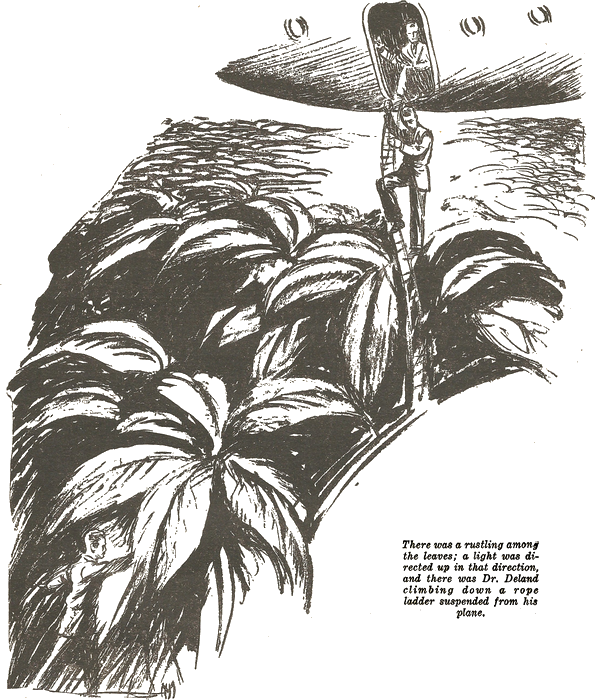

Then there was a rustling among the leaves; a light was directed up in that direction, and there was Dr. Deland climbing down a rope ladder. I apologized shamefacedly.

"I'm afraid I'm hard to take care of," I said.

"Small matter," said one of the engineers succinctly. "Glad to have the problem."

I climbed up the swaying ladder behind them, into the car of the airship, and a few moments later was lowered into Dr. Deland's front yard.

"I've been thinking all afternoon," the doctor said at the dinner table. "You are anxious to work. I must confess that your attitude puzzles me. Knowing that you might possibly awaken during my lifetime I have studied the history of your era closely. I did not gather from my study that it was psychologically possible for a person of your century to realize so powerfully the duty of the individual to the State. Every epoch has its psychological characteristics, which are with difficulty comprehended by the people of other epochs. A strong feeling for individual personal liberty, political and economical, was the psychic expression of your age, whereas the individual's obligation to the State is our own.

"However, it is probable that each epoch contains a few individuals who feel and live ahead of their time. We had intended handling you with consideration for the psychology of your own day; but we shall be only too happy to realize that you are one of us and to treat you as a modern citizen.

"Giving you immediate productive work was at first not an easy question. You must realize that to-day every job is highly specialized, and the man who does it must be carefully trained for it. With all your education, it would take you at least a year to train into the easiest position we have to offer. But, a happy inspiration came to me. You can step into real work at once."

He beamed at me as though he had accomplished a real triumph. I was glad. It would be gratifying to be able to work and to be somebody among these people. Only for a moment I permitted my thoughts to dwell delightfully on the nurse. Soon I would see her; now I must listen to the doctor. He continued:

"You have an untold advantage over the best of our historians. You have first-hand knowledge of men, places, and events of your day, that will be of immense value to us; and among historians you will be looked up to and sought after. I talked to several of them this afternoon.

"They will want you to give a complete systematic account of everything you can remember of your times, for their records. That will probably take many months. In the meanwhile you can be rated and your aptitudes determined so that you will know for what vocation you are most fitted and begin to train for it.

"You will be given apartments at the University, and can live right there with your work. To-morrow morning I shall take you there."

"THERE is one little inconvenience that will be imposed on you as a penalty for having gotten into affairs," Dr. Deland said to me as we sped toward the soaring skyline of the dazzling city on Monday morning. I wondered if he noticed my lack of genuine enthusiasm over my prospective job. I was rather annoyed at my own reaction to the matter. I had expected that a real job would make me feel better, but I only found myself constantly wondering how far it was from the University to the hospital.

"As long as you were at the hospital or at my home, it was possible for you to remain in retirement. But arranging for a place for you at the University and for an apartment for you to live in, involved publicity. The news is out. The public wants to see and hear you; and before going to the University you will have to appear on the news screen and say a few words to the world. You are a very famous person. Do you mind?"

"I suppose not," I answered. I had never thought about such a thing. As a matter of fact it was just a little thrilling to think that I would appear before millions of people all over the world.

Into the roaring depths of the tunnel under the clattering moving ways the doctor's big-wheeled car carried us; and the city closed over our heads. Countless passenger cars were streaming in from the country, outnumbering the heavy traffic at this time of the day, for people were swarming in to their work. Up on the upper street we found the noise of the machinery less obtrusive; faces were fresh and cheerful in the morning air, and the slanting sun shone brilliant on the dress of many colors. Especially the faces! They showed a uniformity and symmetry, a refinement that puzzled me. Had this somehow become a perfect human race?

Under a huge arched doorway, through a magnificent lobby, down a vast corridor, and into a richly appointed broadcasting studio the doctor led me. There, an unbelievably active man was waiting for us. He seemed to sense our coming before we had stepped out of the elevator; as he waited in his open door his personality raced down the hallway to meet us and expanded about us and whirled us away. He welcomed me, asked me a hundred questions, led me in, explained the broadcasting machine, and told me what to do and how to do it, all at the same time. He was all around the room in a twinkling; he gestured, chiefly with his fingers; he talked at a prodigious speed far past my ability to understand him. He was an official high up in the news organization, and I was being highly honored to receive his personal attention.

I stood in front of the lenses with the bright light on me, and he pirouetted among the tubes, smiling and frowning and gesticulating at me to coach me into proper attitudes and expressions. For an instant he shut off the machine.

"Remember! Millions are watching you!" he hissed.. I looked about the little room, hung with brown draperies, and at the blank lenses. The whole business looked a little foolish.

"Now tell them how it felt to wake up among us!"

I did my best at that, feeling very silly.

"Now, then, about your wanting to have work to do as soon as possible!"

I felt my face flush hot at this, and turned on him resentfully. This was getting personal. But he pranced up and down before me, out of range of the lenses, with a frantic expression on his face; he was suffering for all those millions of news subscribers. I stated briefly that I wanted to be a citizen on equal footing with the rest, and wanted to earn my privileges.

"Now promise them that to-morrow you will tell them about the 'radio' and the automobiles of the twentieth century."

If I could have reached him, I would have driven my fist into his face. He acted as though I were his personal property, and as though he were entitled to make a puppet out of me and my feelings as much as he pleased. I gritted my teeth and said what he asked me to. He shut the light off and in a moment was gone. I had a recollection of him bobbing up and down in a flash of thanks, and he was gone, while I stood there gasping.

"Brrrr!" I was clenching my fists and gritting my teeth to hold myself in. I came near saying some worse things than that; only there stood the kindly old Dr. Deland, looking at me with a somewhat puzzled expression on his face.

"Now to the University!" groaned my inward consciousness. Outwardly I said nothing. During my twentieth century life I had known people who wished that they could be living this far into the future. With all my power I wished I had them here to exchange places with.

WHY dwell on the details of my tedious experiences

at the University? It depresses me to think of them. I

had thought I would see classes of young people eagerly

watching me, as I talked to them of olden times; I had

hoped for appreciation in the faces of listeners, I had

hoped to read their enthusiasm in their faces and to answer

their interested questions.

Instead, I talked into a machine. For three days I sat alone in a small room, and talked to a machine, and then it became more than I could stand. By the end of the first day they had delivered to me a complete outline of everything they wanted me to talk about; I got a big printed book of a thousand pages. On the third day I was a quarter of the way down the first page of phonetic letters.

The machine had a microphone, and vacuum tubes could be seen when a lid was raised; a strip of tape ran through it, and I could turn switches to certain buttons and hear my voice telling me back the things I had said. For my own voice, it seemed to have a droning, melancholy quality to it.

I could not use the drawing machine, though it was easy enough to operate; keys with the names of objects and relationships on them were set like the keys of an adding machine; then the motor was started and in a few minutes the finished sketch came out. But my drawings all turned out to be twenty-second century scenes, objects, and people. However, as I command a pencil fairly well myself, I amused myself by illustrating some of my remarks with my own hand.

There were two more visits to the news studio. The next day I said a few superficial, sketchy things about my own age two and a half centuries back. The combination of human dynamo and jumping-jack was not there that day, and I went mechanically through what was asked of me by a courteous, but very young attendant. Apparently the results were disappointing to the world audiences, for on the third morning the dapper, chattering whirligig of a man was back. He smiled at me and stroked my shoulder; in fact, he twisted me around his finger. He had me acting like a monkey before the lenses just by the strength of his personality.

That evening I sat in my beautiful but lonely apartment at the University, trying to relax after the day's struggle with the dictation of history. It occurred to me to switch on the "news-machine." There I saw myself on the glass, with a sickly smile, and saying in a simpering voice:

"I am asked to tell what effect your modern age produces upon me; I am asked to give purely personal impressions. I must confess that while the mechanical developments that I see about me amaze me very much, it is the differences in people that really seem most profound to me. Such perfect health and comely personal appearance, such logical behavior; so little illness; such placid smoothness in the operation of everything; such an absence of friction between individuals and organizations it seems to be a world where reason reigns.

"And yet I miss something here. Why does everyone and everything seem so mechanical to me? Why is there such a lack of human warmth? Is it because human emotion is so thoroughly repressed among you? I feel very much alone in this world. The nearest one of you seems a thousand miles away—"

I sat there watching the glass and listening to the sound of my own voice, aghast. Is that what I had said this morning, under the influence of that gibbering little demon?

"I long for human nearness that meant so much in our day, even though our civilization was crude—"

What a fool I had been to lay my heart out on a platter before the gaping multitude! Usually I am retiring and secretive. I was horrified.

"It seems that somewhere in this world there ought to be an answering throb of emotion to the vast desolation that I feel—"

Had I actually said that? Cold shivers went up and down my spine. What business had that prying little mannikin to lay bare my innermost secrets this way? Now everybody knew just how I felt. They could probably guess a hundred times more than my words really said. I paced across the room, and then aimed a vicious kick at myself on the news glass. It shattered, and the pieces tinkled to the floor. My voice suddenly stopped.

"Damn!" I said to myself, and went to bed. It was hours before I could go to sleep.

In the morning I refused to accompany the young attendant who came to conduct me to the news studio.

"Tell them I'm fed up on broadcasting!" I said and shut the door.

Within ten minutes Dr. Deland came in.

"How do you feel?" he asked.

Just in that same tone of voice we used to speak to the patients at the psychopathic ward of the Cook County Hospital in Chicago.

"I'm not going to broadcast," I said, standing in the middle of the floor.

"Would you rather go to the hospital with me?" he asked kindly, it almost seemed sympathetically.

My knees almost gave way under me.

"Yes!" I gasped.

IN the door of the little green room at the hospital stood Elite Williams, smiling. From the way she held out her hand to me, I fancied that perhaps she, too, was glad to see me.

"Why shouldn't I be glad to see you? I've taken care of you for two years." Again amazement held me. I exclaimed: "You don't mean to tell me that you people have learned to read each other's mind? Scientific views in my day held that such a thing was not possible and could never be possible—thoughts are the functioning of a mechanism, and do not have a concrete existence that can be transferred to or perceived by others."

She laughed at my astonishment and explained: "No. Thought reading and thought transference have not been found possible. But we can interpret your postures, actions, and expressions, and deduce your thoughts from them. The people in your day must have been very naive; it is easy to tell what you are thinking."

"Well," I said, "I am glad that you know all about it, then. You do not seem to mind. If you did, this would be a terrifyingly confusing and lonesome world."

I do not know just what I might not have said or done next, had not Dr. Deland come into the room.

"Would you mind going through a diagnostic examination?" he asked, looking at me oddly, as though he expected that I would object.

"No," I replied. "I rather think I should be very much interested in the procedure. But why?"

"We all take them periodically; and you would have to eventually. But the request comes just now because your behavior shows some unstable deviations, and it is possible that some physical basis may be found for them."

I appreciated his frankness and told him so. Often since then I have thought about his perplexity over my behavior. Here was an era which understood psychology well enough to train people to live together in peace and harmony, and to keep a civilization stable and orderly, though one man by the touch of a button could wreck it flat. Here were people who could look at me and tell what I was thinking about. And yet they did not fathom what was the matter with me. My simple, old-fashioned mother would have recognized my trouble from its symptoms, at once.

Of course, at that time I had no idea what the trouble was myself. Now that I look back, it is all plain enough. But, I had never been in love before. All I knew was that I wanted to be near the hospital; and that I was miserable and unhappy at all times except when I was in her smiling and sympathetic presence. After all, far more foolish things than any I ever did have been committed by young fellows who were upset about a girl. My behavior merely looked so terrible to them, far more terrible than I realized, because it contrasted so diametrically with that of a whole race who never did such things. Why couldn't they tell by their thought-interpretation process that I was in love? Because they did not fall in love, and did not know what such a thing was?

While I waited alone in the green room, to be sent for and examined, I turned on the news-machine. The current news had no pictures; a voice was talking:

"The Sleeper acts strangely.

"Something is wrong with him.

"What shall be done with him?

"He wanted to produce, but broke down.

"He wrecked a news machine; was it a fit of illness?

"Is he sick? Or retrovert? Is it possible for a human mind to cross two centuries successfully?

"If it is not possible, what then?

"He has just consented to be examined at the Lancaster Hospital. Where does he belong in our world?"

The melodramatic hiss ended, and there began a report in a deep voice, regarding the course of a moon-projectile. But, intensely interesting as that ought to have been to me, I could not get my mind on it. Evidently these people were taking me seriously. Why? What could I mean to the world, except as an object of curiosity? For a long time I sat in a deep study, until Dr. Deland's voice brought me out of it.

"Medical men of your day," he explained, as I went with him to the diagnostic laboratories, "made their diagnoses by symptoms and on the basis of post-mortem pathology. They had not yet learned that disease is not a thing per se, but merely the visible result of an individual body not properly adapted to its environment. We do not try to know disease, but rather to find the maladaptation. This is the Barkeley Intonator, and determines the proprioceptive index——"

A NURSE was already strapping pads to my wrists; a

mellow little gong began to strike. While the nurse watched

a couple of dials, a transparent tape ran out of the

machine into her hand, giving the machine's verdict on me.

Out of that I was put on a delicately balanced beam in a

dark room, and beams of light cut the blackness about me.

The doctor explained that a tracing of my parasympathetic

functions was being made. I had stuff injected into a vein

and stood before the X-ray, and saw it darken through my

lungs. Efficiency curves of the heart, lungs, cerebellum,

stomach, and what else I don't remember, were run out on

kymographs as I went through one machine after another.

The doctor kept explaining what each one did and what the

result signified, but I gave up trying to comprehend it.

When they got through, they knew me piece by piece; they knew what each piece could do and whether it was any good or not, and how all the pieces went together. I felt like a watch that a jeweler has taken to pieces and put together again. I was stunned by it all; I was thrice discomfited because of the excellent medical education I had had in my day, for I could make neither head nor tail of any of the things they had done with me.

When they were all through they gave me a clear ticket. They found no fault or flaw in my physical structure nor in any of my functional activities. If I knew anything about reading faces myself, I recognized that they were more puzzled when they got through examining me than they had been when they began. Obviously I was as amazing to this world as this world was to me.

It was hard for me to realize, and it will be hard for my reader to realize how strange and puzzling the situation was to the twenty-second century people. To have somebody suddenly refuse to do a very obvious thing like broadcasting; to have him get a fit and smash up a news-machine! In our twentieth century, those things happen every day. Misfits and maladaptations are common. But the twenty-second century had eliminated these things and had forgotten that they ever existed. Therefore, they could not understand me. Only a few scientists understood me in the abstract.

"Now do I go back to the history department?" I asked.