RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

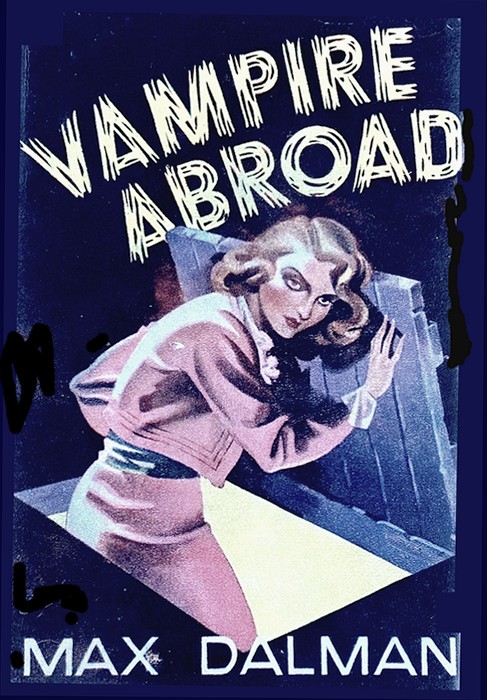

"Vampire Abroad," Ward, Lock & Co., London, 1938

"Vampire Abroad" is a classic British murder mystery with a macabre twist. The story begins when Sir Arthur Scarsdale is found dead in his locked bedroom. The local doctor diagnoses heart failure—but Sir Arthur's nephew Shelton, a newly qualified doctor, suspects something more sinister.

As Shelton investigates, he notices strange details about the body. A post-mortem reveals the shocking truth: Scarsdale's body has been almost entirely drained of blood.

Set against the backdrop of a genteel English estate, the novel blends traditional whodunit elements with eerie gothic overtones, making it a outstanding example in the genre of vintage crime fiction.

FOR the third time, with polite but increasing insistence, Benton's knock sounded on his master's door. He was beginning to feel worried. During the past ten years, almost without a break, he had called Sir Arthur Scarsdale in the same way and at the same time. Punctually at half past seven he had entered the room, placed the morning tea on the bedside table, partly drawn the curtains and awaited further instructions. And for the same period his master had reacted to these attentions in precisely the same way. Waking at the very opening of the door with something between a snort and a grunt, he would yawn once or twice, gulp down the first cup and suck his moustache noisily, and only then feel sufficiently aroused either to give the valet his dismissal or to express his further requirements, ranging from a dose of bicarbonate of soda to an elephant rifle.

But that morning things had been different. Never before in all his experience had Benton found the bedroom door locked; and never before had the baronet failed to awaken at the slightest sound. In spite of his fifty-eight years, Sir Arthur Scarsdale still preserved the virtue of early rising and the capacity for becoming instantly alert from however deep a sleep, which he had acquired during a long and adventurous career as a hunter of big game previous to his accession to the title. Of both he was extremely proud, and to Benton it was unthinkable that the first knock should not have brought him to the door in an extremely bad temper almost instantly. The only explanation which occurred to him was more disquieting even than the silence within the room. Benton knew of the visit of Dr. Arnley the previous evening, and the tablets which he had prescribed for sleeplessness and occasional sick headaches by which Sir Arthur had been troubled; and the mere thought of sleeping tablets brought to the valet a vivid recollection of the time when, as a young man, he had found a former employer wrapped in a sleep from which he had never awakened. At the remembrance of his discovery sudden alarm overcame him. Laying the tray on the floor, he beat with his fists on the panels, heedless for the moment of anything but the necessity of obtaining an answer.

"Sir Arthur! Sir Arthur!"

From inside the room there was no reply; but lower down the passage another door was flung violently open. Though Benton had never seen the young man in green silk pyjamas who emerged from it, the talk of the servant's hall made his identification easy. He himself had heard Sir Arthur speak of his young cub of a nephew, Peter Shelton, who, to the surprise of everyone, and not least to his own, had finally completed his medical degree in London. It might have been this achievement which had resulted in a reconciliation between nephew and uncle which Shelton's arrival at an unduly late hour the previous night, in bad condition after a farewell celebration party, had done much to destroy. On the evidence of Slater, the butler, who had been present at their meeting, their interview had been a stormy one, and by no means designed to bring about the gift or loan of sufficient money to buy a practice which had caused, if not Sir Arthur's invitation, at least his nephew's acceptance.

"What the blazes—?"

Perhaps Shelton had inherited the family temper; almost certainly, judging by his appearance, he was at that moment the victim of a headache comparable to any of his uncle's, though differently caused. Clearly Benton's knocking had been more than his nerves could stand, for he spoke with a vast irritation.

"What's up? What the devil d'you think you're doing?"

Benton flushed a little at the tone of the rebuke; then his anxiety reasserted itself. He broke into eager explanation.

"It's your uncle, Sir Arthur, sir!" he said a little incoherently. "I came to call him—"

"Good heavens above us!" Shelton interrupted rudely. "Does it take an earthquake to do that? For the Lord's sake do it quietly, or let the old—let him have his beauty sleep in peace! He needs—" He put his hand to his forehead and closed his eyes. "Oh, Lord, I've got a head! You might get me—"

"But there's something wrong, sir. Your uncle always wakes at the least sound. He never locks his door. I've never known him to lock it... The doctor came yesterday, sir—Sir Arthur had been complaining of headaches lately, sir, and he left some tablets. I thought—do you think, sir—? You see, sir, I can't wake him. I've knocked—"

"You have," Shelton conceded grimly. "I heard you... Tablets? What sort of tablets? Sleeping stuff?"

"Sir Arthur didn't say, sir. But don't you think—"

"Sleeping tablets would account for it. Muck! Some fools dish 'em out like sugar, when all that's needed is that one should behave like a reasonable being—" He broke off the disquisition on what was evidently a favourite subject and put his hand to his eyes again with a groan. "Better leave him. He'll sleep it off in time."

"But, sir, supposing—"

"Anything wrong?"

Neither of the two had noticed the slim, middle-aged man who had joined them. The thin, aquiline face showed an unnatural pallor suggestive of ill-health even under the tan of one who has spent a long time in the tropics, and in spite of the thick dressing gown which he wore he shivered slightly in the cold morning air. The valet evidently hailed his appearance with relief.

"It's Sir Arthur, Mr. Faringdon, sir," he answered eagerly. "I've knocked, but I can't make him hear. And the door's locked, sir. In the ten years I've been with him, I've never known it happen. I'm afraid, sir. Perhaps something's happened—"

"The sleeping tablets would explain all that," Shelton broke in irritably. "He'll wake all right—and in the deuce of a temper, if I know anything about—"

"It's Mr. Shelton, isn't it?" Faringdon's interruption was no less effective through being polite. "Your uncle told me that he was expecting you last night. My name is Faringdon—James Faringdon—"

"The explorer?" Shelton frowned a little in his effort to concentrate; then felt moved to an apology. "Sorry if I was rude—"

"Not at all... But don't you think, Mr. Shelton, that in view of your uncle's age his failure to answer is—well, rather disturbing? He is no longer a young man. And lately, as you may not know, he has not enjoyed the best of health. Dr. Arnley has been attending him for high blood pressure—"

"What? Might be a stroke, you think?" Shelton asked a little dubiously. "He didn't look like it last night—and he'd have had one then if he was going to! He looked in the pink—good for years, I should say... But, anyway, what the devil are we supposed to do?"

"There's another key?" Faringdon turned to the valet. "It seems to me we'd better open the door. If anything were wrong—Perhaps the butler, or Mrs. Woodney would have one?"

"I'll see, sir!"

As the valet hurried away, Faringdon gave a tentative twist to the handle of the door and pushed; then he bent down and put his eye to the keyhole.

"Key's not in the lock," he announced as he straightened himself. "I can't see anything... Really, Mr. Shelton, I don't like it. I believe that you have not seen your uncle lately? Perhaps you do not know that he has an unconquerable prejudice against being shut in, quite an obsession? I can't think that—"

"Sort of claustrophobia? No, I didn't know that." Shelton glanced uneasily at the closed door. "Then he'd never lock himself up... But—well, you're an old friend of my uncle's, Mr. Faringdon. You know that we haven't been on the best of terms—and I'm afraid that he was pretty furious with me last night. If I go bursting in there and he is all right—" He smiled ruefully. "Well, you can imagine... Though you're right, of course. We'll have to make sure."

"I see your position. But I'm afraid we should take the responsibility, even to the point of breaking in... As your uncle's only close relative, and his heir—"

"Heir?" Shelton gave a short, mirthless laugh which was full of bitterness. "As it's always been understood that he'd leave me as little as he could—and last night he told me so pretty plainly—" He stopped, looked again at the door, and continued in a different voice. "But I shouldn't like to think that anything had happened to the old boy, of course... It's all right, really. Just the tablets. If doctors will go dishing out drugs to people who only need to be made to act sensibly it's no more than you might expect. He'll sleep it off."

"But an overdose?" Faringdon countered. "Have you thought of that? I'm not aware what the tablets were, but if Sir Arthur had not been warned of any special danger in taking too many—"

"Hell!" Shelton started, and then passed his hand over his eyes again. "Never thought of that. I'm not bright this morning... Where the deuce is that fool servant? He's taking all day. If it's that—Good Lord, he might be dying while we stand here!"

"Might knock again?" Faringdon suggested.

Shelton's large fist thudded obediently on the woodwork with a violence which threatened to make the use of a key unnecessary. Certainly no one inside the room could have helped hearing it, but the door remained closed. There was not a sound when he paused to listen. All at once he began to be afraid.

"Uncle! Uncle! Wake up! Wake up!"

In the silence which followed, hurrying footsteps from the far end of the passage made them both turn. Like themselves, the newcomer had evidently just been awakened, perhaps by Shelton's last thunderous effort. As he came to a halt beside them, his tall, gaunt figure seemed to tower even above Shelton's own six feet of muscle. Under the iron-grey hair a pair of keen eyes glanced curiously from one to the other.

"What—?" the newcomer began. "Something wrong?"

"Scarsdale doesn't answer, Turton." It was Faringdon who replied. "His door's locked. We wondered if—"

"What the devil are you waiting for, then? Smash it in!"

"The key," Faringdon explained. "Benton's gone to see—"

"Don't wait for that! The man may be dying. Get a move on!" He looked at Shelton's well-built figure approvingly. "His nephew? Good! You and I can manage that together. If the lock doesn't give, the wood will—"

"Wait! Here's Benton!" Faringdon intervened as the valet and Slater appeared at the head of the stairs and hurried towards them. "Slater, where's that key?"

"No—no key sir!" The butler was breathless with haste. He looked with scared eyes from one to the other as he spoke. "Only the one, sir—in the door. There's never been more since I was here. The master, sir? He's not—he's not—"

"That's what we're going to find out!" Turton snapped. "Don't waste time! Here, Shelton—ready? Now!"

With a violence which hurt Shelton's thinly-clad shoulder abominably they crashed against the door together. Between them they weighed at least twenty-five stone, considerably more than the door had ever been constructed to stand. A panel cracked.

"It's coming!" Turton panted. "Again! Now!"

This time it was not the woodwork but the lock which gave. Shelton, nearest the hinges, managed to save himself as Turton fell headlong into the room. For a second they all hesitated, staring into the half darkness resulting from the stray gleams which filtered through the thick curtains. Turton jumped to his feet.

"Come on! Slater, draw those curtains. Shelton, you're a doctor, aren't you? Hurry up!"

Shelton was vaguely aware of his bare foot striking something hard as he hurried across the room to where Turton was already bending over the bed. He had a glimpse of a dark outline against the pillow in the twilight of the darkened room. Then the curtains flew back. Even as they did so, Turton straightened himself with an exclamation.

"Good God! Dead!"

"Sure?" Shelton's professional instincts seemed suddenly to arouse themselves. He pushed the other aside impatiently. "Let me see!"

But almost the first glance at the waxen-looking face was enough. Automatically he stretched out a hand towards the wrist which lay uncovered by the bedclothes; then an exclamation was forced from him.

"He's cold! Dead for hours!"

"Faringdon, get Arnley on the 'phone!" Turton seemed suddenly to have assumed control of things. He turned to where the man he addressed stood shivering just inside the door. "Say what's happened. There may be a chance—"

"There isn't." Shelton spoke with quiet decision. He stood erect, eyeing the still figure on the bed curiously, as though it was something incredible. "Poor old boy! If I'd known—I wonder what—Ah!"

He stretched out his hand eagerly towards the pill-box which stood beside a half-emptied tumbler of water on the table near the bed. Taking a tablet from it, he moistened it with the tip of his tongue. Then he whistled softly.

"Luminal?" He tipped the contents of the box on to the palm of his hand. "Three—five—seven! The ass! How many—?"

He looked from the tablets to the dead man with his brows creased into a frown; then as a thought seemed to strike him replaced them in the box, and taking up the glass, sniffed at its contents carefully. Turton broke in with angry impatience.

"Aren't you going to do anything?" he demanded. "Why, he may not—"

"There's nothing to do," Shelton's voice was a little hushed. "He's been dead an hour or more—"

"You've just qualified, haven't you?" Turton shot out. "Arnley's an experienced doctor... Thank heaven, he'll be here in a minute or two. His house isn't a hundred yards away—"

"Arnley must be an—" Shelton started to reply heatedly, but restrained himself. "I tell you there's no hope. I wonder—"

Pulling back the bedclothes he bent down and began to look more closely, while Turton fumed impatiently in the background.

"You've seen men dead?" Shelton looked up at him. "Notice anything wrong?"

"Wrong?" Turton echoed the word contemptuously. "What d'you mean?"

"Don't know... Oh, general appearance and so on. I can't quite place it... Somehow he seems smaller. As if he had shrunk—"

Turton made an unintelligible noise. There was a moment's silence.

"What killed him?" Turton demanded at last. "You don't think that he—not suicide?"

Shelton shrugged his shoulders. "Can't say. Only I shouldn't think it was the stroke which Dr. Arnley in his wisdom seems to have thought possible. I'd have said, seeing him now, that he was rather anaemic than otherwise—"

"But that—those?" Turton pointed to the tablets. "How many had he taken? Did they—"

"How on earth can I tell?" Shelton's mingled feelings culminated in a wave of irritation. "Now, how could I? Maybe Arnley can say. He gave the damned things. He ought to know how many there were."

"Well, perhaps we'll know the truth—when Dr. Arnley arrives," Turton rejoined acidly. "You take it pretty calmly, Shelton, I must say. But then, after last night—well, I suppose you'll not be a loser by this! You're lucky—" He broke off, perhaps at the sight of the sudden clenching of Shelton's fist and shrugged his shoulders. "Well, that's not my business... What's keeping Faringdon? Slater! Slater! Go and see—"

"He—he's dead, sir?"

Benton had at last ventured to approach, and stood looking from the two men to the bed with a kind of timid obstinacy. Shelton nodded.

"Then, sir, there's something wrong!" The valet turned to Turton appealingly. "Why did he lock his door, sir, for the first time in ten years, sir—ever since I've known him? And in his own house, sir? Sir Arthur never locked his door... It's not right, sir. Why should he do it last night?"

"Better ask Mr. Shelton that; he saw him last," Turton said drily. "And he's Sir Arthur's nephew—"

"If you mean—" Shelton broke out furiously, but Turton had already turned away towards the door.

"Locked his door," Benton stood looking down at his dead master. "But—but he can't be—"

"I'm afraid he's dead," Shelton sympathised.

"Nothing we can do—Benton raised his eyes suddenly, and Shelton's voice died away at what he saw there.

"Faringdon! Faringdon!" Turton bellowed in the passage. "Oh, you're there! Where the devil have you been?"

The two entered together. Shelton noticed that Faringdon had partly dressed, and Turton seemed to notice the same fact with disapproval.

"Really, Faringdon, when poor old Scarsdale's dead—"

"No reason why I should be." Faringdon's calm contrasted with the other's excitement. "If I'm laid up with a chill, that's not going to help things much, is it? I've malaria on me now—Sorry, Shelton. Bad luck for you, coming back to this. Can hardly realise it. Known him for years."

"I hardly knew him," Shelton confessed. "But it seems bad luck that we should quarrel the night before—oh, well."

"Dr. Arnley coming?" Turton pointedly addressed himself to Faringdon. "Why doesn't the fool hurry? We might do something—"

"There's nothing to do!" Shelton snapped. "D'you think I'd be standing here if there was? Nothing but sign the death certificate—and I should say Arnley was the right man to do that! If you're implying—"

"That's all right," Faringdon placed a restraining hand on the younger man's arm. "You're sure he's dead, aren't you? We're all a bit on edge, you know. Turton doesn't mean anything."

"There's no doubt he's dead—worse luck. But Turton—oh, look at him yourself!"

Faringdon advanced towards the bed as he stepped aside; then all at once he seemed to hesitate. A look of horror spread over his face. Before Shelton could catch him he fell senseless to the floor.

CONVEYED though it had been in Faringdon's customary calm and tactful way, the intelligence of Sir Arthur Scarsdale's death might well have come as a shock to Dr. Arnley. Sentimental considerations apart, it is disconcerting even to a member of a profession habituated to death to hear that the host who had invited you to shoot his covers has been found dead in bed on the morning in question. And, like all doctors when confronted with a consequence which they have not foreseen, he was not without grounds for a haunting suspicion that diagnosis or treatment might have been at fault. Dr. Arnley, to his secret sorrow, had often felt such a doubt, though he would have been the last man in the world to admit it. Acquiring his semi-rural practice some twenty years previously, in a district where people normally fell ill and died of the same things under conditions which rendered the presence of a doctor superfluous, inevitably he had forgotten much of such training as he had originally received, and in his heart he knew it. Patients liked his air of decision; for the very doubts which he occasionally felt about unusual cases had made him more inclined to be definite after the event, as they had also rendered him more capable of covering possible mistakes in advance. Private patients swore by him, less because of his brilliance as a physician than owing to his power of listening sympathetically, commiserating delicately, and extolling the virtues of the dear departed. The ability to shoot a pheasant as accurately as a less socially desirable doctor might remove a troublesome appendix had increased his popularity with his wealthier patients, and though recently troublesome competition by a younger man had reduced his income more than he would have cared to admit, his reputation in the neighbourhood stood high.

But as Slater showed him up the stairs he was obviously worried. The day before he had diagnosed migraine; and from migraine, he told himself obstinately, Sir Arthur had certainly been suffering. But whether he had or not, there had certainly been no ground for believing that he suffered from anything so badly as to spoil the next day's shooting. Blood-pressure a little high; digestion a little weak, chiefly through injudicious eating; a bit chesty in winter—there was no reason why the baronet should not have lived for years. But there was that luminal. Of course the baronet had had it before; in spite of a tendency to overdose himself he was a man to be trusted with it. But twelve grains in half grain tablets—Dr. Arnley had a horrible feeling that it might seem excessive, and just at that time he was horribly nervous of the slightest slur on his professional ability.

Turton, who was known to him, having been his next door neighbour at a shoot three days ago met him at the stair head.

"Glad to see you, doctor. Bad business. 'Fraid it's no use. He's dead. Or so his nephew says—"

"His nephew? Ah!" The slightest possible spirit of antagonism stirred in the doctor's mind, quelled almost immediately by the thought that the nephew was now the new baronet. "Yes. I think Sir Arthur mentioned that he was coming... A medical student, I believe? He should know."

There was the faintest possible emphasis on the word "should," but Turton did not take the same trouble to conceal his feelings.

"Cocksure young ass!" he criticised. "Seems to think there's something funny about it... You'll soon see."

"Of course—of course!" Arnley had paled the least degree and he hurried on. "Yes, as you said, Mr. Turton, a terrible business. As a personal friend I may say that I feel it deeply—very deeply. Why, only yesterday he had invited me—"

"This way." Turton steered him towards the bedroom, the whereabouts of which, in his agitation, he had temporarily forgotten. "Dead when we found him I think—in his bed. I heard a noise and found Shelton and Faringdon fluttering about outside like a lot of hens because he didn't answer. Then we broke in the door. Died in his sleep, I should say... What do you think it was, doctor? A stroke?"

"Possibly—yes, very possibly. Without further examination I couldn't say. Sir Arthur, you know, was one of those men who might have lived for years—or died quite suddenly. I had warned him gently to be careful. Anno domini, you know, Mr. Turton, anno— but what's this?"

Just inside the doorway, Shelton was supporting Faringdon on a chair, while the butler hovered near with a glass of brandy and a towel hastily wetted in the adjoining bathroom.

"Oh, Faringdon fainted," Turton explained casually. "When he saw the body. South America knocked him up, you know, fever and so on. When he looked at—"

"The bat! The bat!"

Dr. Arnley jumped and looked round as Faringdon cried out. His eyes had opened suddenly, and he was staring past the group standing round him with an expression of utter horror. Then sanity seemed to reassert itself. He sat up weakly.

"I—I'm all right," he said; but shuddered as he glanced towards the bed. "Give me that brandy!"

He had drained every drop of it before he spoke again, and a little colour came into his cheeks.

"Help—help me get out of here. I—I'm not feeling well."

Dr. Arnley took his wrist gently between his fingers, but his face showed nothing of the jumping pulse which it revealed.

"Shock," he said soothingly, "just a simple shock and general weakness... I should prescribe a tonic for you, Mr. Faringdon. You are run down. Nothing serious, of course... I am not surprised that you feel this—this sad event deeply. Perhaps if you lay down for a little—"

Faringdon snatched his hand away impatiently and made an effort to rise.

"Help him, Slater!" Turton commanded. "There, that's right. Don't worry, Faringdon... Give me your other arm."

When Turton returned, having seen the butler and his charge safely in the next room, the doctor had already advanced towards the bed where Shelton had waited to receive him. The young man's attitude was unencouraging; and the sight of the glass and pill-box at the bedside filled him with disquiet, but he was the acme of professional calm, controlled though distressed.

For a moment the two stood looking at each other in an embarrassing silence. Turton, in his self-appointed capacity of master of ceremonies ended it with an introduction.

"This is Dr. Arnley, Shelton," he said brusquely. "This young man is Sir Arthur's nephew, doctor."

The form of address did nothing to placate Shelton, but Dr. Arnley extended a hand.

"Good morning—er—Sir Peter!" Shelton started as if he had been stung. In the stress of the moment, even the correct butler had refrained from giving him his very-recently acquired title, and the idea that he had become a baronet by his uncle's death was not one upon which he wished to linger. He eyed the doctor with dislike, and shook hands reluctantly. could have wished that we met under happier circumstances, Sir Peter," Arnley continued unctuously.

"There is no doubt, I presume, that Sir Arthur is dead?"

"None. Though I'd hardly thought yet of assuming the title. It's not half an hour since we found him." There was a rudeness in Shelton's manner which even the doctor could not entirely ignore. "You'd better look yourself. You've been attending him."

"Yes—yes, of course." Mortification and nervousness were blended in Arnley's voice, but he tried to pull himself together as he turned towards the bed. "Had you—had you formed any conclusion yourself, Sir Peter, with regard to the cause of death?"

"None. I've not examined him. I thought, as you'd have to give the certificate, I'd better leave that for you. You'd been attending him, and would know what he'd be likely to die from."

"That is so, of course." Arnley did not look up. Ordinarily that should have been so, he reflected; his difficulty was that the examination yesterday had revealed nothing at all which really appealed to him as a possible cause of death. "Yes, of course," he murmured again. "The old trouble, I'm afraid... Yes."

"You'd been expecting it?" Shelton asked with a malice which no one perceived.

"Expecting is too strong a word, Sir Peter." Arnley straightened himself, and casually, very casually as though it were a detail of very minor importance, stretched out his hand towards the pill-box. "I see that he has been following the treatment which I recommended," he observed as he opened it. "Ah!"

His sigh of relief was distinctly audible, but only Shelton understood it.

"You're satisfied as to the cause of death then?" he asked.

"I fancy there will be no difficulty about that... Sir Arthur, you know, Mr.—Sir Peter, was no longer a young man. He had lived an active life, a full life, and one not unworthy of a man of his abilities. Any little thing at his age—any additional strain or worry—"

This time, unintentionally, the doctor had got home. Shelton flushed noticeably.

"You're not suggesting—?" he began hotly, but Turton intervened.

"What did he die of, doctor?"

"Bearing in mind all the circumstances," Arnley said carefully, looking appraisingly at Shelton as he did so. "Bearing in mind all the circumstances, the history of the case, and his condition revealed by my cursory examination of him yesterday," he continued gathering strength as he continued, "I should say that there was no doubt. Yes. Cerebral haemorrhage—undoubtedly I should say that he never regained consciousness. He was lying like that when you found him?"

"Yes," Turton answered. "Cerebral what's-its-name? That's a stroke, isn't it? Thought so... Hullo, Faringdon! Better?"

Faringdon nodded. "It was stupid of me," he apologised. "When I looked and saw him—" he broke off, keeping his eyes averted from the bed. "Funny. I've seen dead men often enough, you'd think." He laughed without conviction, breaking off abruptly. "Finished your examination, doctor? What was it?"

Dr. Arnley inclined his head. He was unpleasantly aware of Shelton's silence; it almost seemed to convey an accusation. But it was not in his nature to precipitate any kind of trouble with a baronet, and his next shaft was entirely accidental.

"Yes," he assented. "A stroke, Mr. Faringdon—following some slight shock or worry... He seemed all right last night? Who saw him?"

"That was you, Shelton—saw him last, I mean," Turton volunteered. "How was he then?"

"Yes, I saw him."

"And how did he seem then, Sir Peter? Worried at all? Depressed?"

"Well, by all accounts—" Turton began and stopped, eyeing Shelton meaningly.

"Yes, we quarrelled," Shelton cut in. "But he was all right when I left him. Perfectly well. Just going to bed."

"Quite, quite," Arnley said soothingly. "Well, Sir Peter, I can do nothing more. I cannot say how much this has upset me. I will let you have the certificate—"

"Doctor, might I have a word with you privately?" Shelton interrupted incisively. The doctor raised himself with dignity, but the young man's next words. "I won't keep you a minute. Something placating. thing just occurred to me which, as a professional man—"

"By all means," Arnley acquiesced a little stiffly. "Where—?"

"In my room? It won't take long."

Conscious that the eyes of both the other men were upon them Arnley followed his conductor obediently, but with a steadily growing resentment at the interference which the request seemed to threaten. There was a trace of defiance in his attitude as the door closed upon them.

"Well?" he asked.

"It's just this." Shelton hesitated for a moment; then continued with a rush. "I've no wish to interfere in your case. But my position is peculiar. I'm a qualified doctor. As you yourself reminded me, I inherit the title at least as a result of my uncle's death. I was the last person to see him alive, and we parted—well, on poor terms... The servants seem to think that there's something queer about it already—the locked door and so on. You see what I'm getting at?"

"Quite," Arnley agreed untruthfully. "Quite."

"Now, you say death was a stroke following some agitation—such as our quarrel. I don't agree with you. My uncle was perfectly well when I left him. It might be said that I killed him. I want that lie knocked on the head once and for all. Are you perfectly sure of your diagnosis?"

For a moment their eyes met. In the young man's expression the doctor read a mixture of emotions which troubled him. He took refuge in a dignified politeness.

"I appreciate your apology, Sir Peter, but I must say that I fail to comprehend your meaning. Am I quite sure—?"

"My meaning's simple enough." Shelton jerked a finger towards the adjoining room. "I'm suggesting that any quarrel we had had nothing to do with his death, directly. I'm suggesting something else caused it. That luminal—how much had he taken?"

"Really, Sir Peter!" Arnley protested. "Are you accusing me of—"

"I'm making no accusations. But that box of tablets was by his bedside. The number it had contained wasn't marked on it—and, by the way, it should have been. So far as I know at present, my uncle might have taken a fatal dose, purposely, by accident, or through the instrumentality of another person. He'd certainly taken some. I want to know if he took enough to kill him. And I want to know if you warned him properly what you'd given him. I'm simply asking—how much had he taken?"

Dr. Arnley's face from being a little pale had changed almost to purple. His wrath prevented him from replying immediately and Shelton continued.

"I don't mind telling you that I think your idea of haemorrhage is nonsense. He didn't look like it to me. In fact, he looked particularly bloodless—almost anaemic. I know it would be a convenient way out for you—something nice to put on the certificate—"

"Anaemic! Really, sir!" Arnley spluttered. "I examined him only yesterday—"

"And found—just what?"

"His blood pressure was high—"

"High enough to cause death? But that doesn't matter. How much luminal did you give him? How much was missing? Did he know he could poison himself with it?"

There was a distinct pause before Arnley spoke. "I—I am not prepared to say," he said gruffly. "Without wishing to be offensive, I must tell you, Sir Peter, that I am not prepared answer to such questions regarding my professional duties except when put to me by someone who has a right to ask them. If you wish for an inquest—"

"But I don't. I merely want to abolish that nonsense about his dying from a stroke following our quarrel. Why, don't you see, in view of those pills and my being a doctor they'll be saying I poisoned him next?"

"I can only say this, Sir Peter." Arnley's anger had changed to a cold fury, and he spoke with a deadly calm. "Your uncle had suffered from migraine, and on previous occasions I had given luminal to be taken during an attack. He was familiar with the use of it, and aware of its dangers. I offer you my assurance that there was not missing from the box a sufficient quantity to kill him, judging by previous experience. But he had certainly taken a large dose—a larger dose than I recommended. I can scarcely imagine his doing so, unless he acted on the advice of some other person whom he believed competent, or unless it was administered to him without his knowledge by someone—"

"Then there was a large dose missing? Enough to cause death? And you didn't mention it?" Suddenly the purport of the doctor's last sentences was borne home to him. "But—Good God! You can't think—You don't mean—?"

"I have already expressed my opinion that it was not as a result of the luminal which he had taken that your uncle died. You prefer, apparently, to believe that it was. Very well. The matter is easily settled. I shall refuse my certificate, and demand a post mortem. If an inquest is necessary, I shall, in mere self defence, be obliged to reveal that Sir Arthur had taken a far larger dose than I had ordered. The Coroner is at liberty to form his own conclusions as to how or why he came to take it, or who might benefit by its administration... That is, I think, sufficient. I hope that you are satisfied?"

For a moment Shelton struggled for speech. He looked as if he might resort to personal violence, and Arnley stepped back a pace in evident alarm. Then Shelton laughed unpleasantly.

"Very well!" he said. "We'll leave it like that.... Will you tell them or shall I?"

"Naturally I shall tell them." Arnley opened the door with an impressive air. "In view of your suggestions—"

He broke off at the sight of the group which awaited them outside the door of Scarsdale's room. Faringdon and Turton had been joined by an elderly woman whom the doctor recognised as the housekeeper, Mrs. Woodney, and the three had evidently been discussing the conference which had been taking place, for they stopped talking guiltily.

"After consultation with Sir Peter, who, in addition to being Sir Arthur Scarsdale's heir, was the last person to see him alive," Arnley announced as Turton looked his inquiry, "I have modified my earlier opinion. I have come to the conclusion that, in view of all the circumstances, a post mortem will be desirable in the interests of all parties concerned. I shall inform the Coroner accordingly."

Faringdon started forward, and his face was ashen, though scarcely more amazed than those of Turton and the housekeeper.

"What—what do you mean?" he gasped. "How—how did he die? You can't think that—He wasn't—?"

He broke off, conscious of the eyes of the others upon him. Turton came to his rescue.

"What the devil's this?" he demanded. "A post mortem? Good Lord, you don't think the man was murdered, do you?"

"Mr. Turton," Arnley replied with due solemnity. "I would point out that no suggestion of that kind has been made by me—"

"But you were definite that it was a stroke—not five minutes ago!"

"And I still believe that to be the most probable explanation. But I may say that the attitude of Sir Peter has left me no alternative, for my own protection. I have every reason to think that a post mortem will reveal death by some perfectly natural cause—"

"Then, why the deuce cut him up?" Turton snapped. "Damned nonsense. Simply making a scandal. Oh well, I suppose you know your business—and I'm not blaming you, Arnley... I'll show you out, doctor."

Arnley seemed to have recovered something of his self-possession as he bowed stiffly in assent.

"Good morning, Mrs. Woodney. Good morning, gentlemen... Mr. Faringdon, I should recommend you to take every care. If you would let me prescribe for you, just a simple tonic, I believe you would find it beneficial... Good morning."

With a shake of his head Faringdon turned and disappeared into his room as they made their way up the passage.

"It's idiocy, Arnley—sheer idiocy!" Turton broke out as soon as they were out of earshot. "And I'll bet it's not your idea, eh?"

"The suggestion, I am afraid, came from me. But Sir Peter's accusations left me no choice—"

"Accusations?" Turton's eyebrows rose. "Shelton accused you of being responsible, did he? That's comic. People who live in glass houses, I've heard—"

"I must warn you, Mr. Turton, against any such implications. I can understand Sir Peter's anxiety, though I scarcely sympathise with his attitude."

"He seems a bit touched to me—or swelled-headed," Turton snorted. "I think they're all daft. What d'you think of Faringdon—going off like that?"

"Mr. Faringdon is clearly in a run-down condition, but that is scarcely surprising... There was one thing that puzzled me. You heard what he said when he regained consciousness?"

"Wasn't listening. What?"

"He said 'The bat! The bat!' And he seemed terrified. As if he had seen something... Turton, I wonder what he meant?"

"Meant he was bats in the belfry!" Turton laughed at his joke, but Arnley did not even smile. "Of course, that was just delirium, or something like that. You can see he's got fever on him... Queer what people will say when they're coming round. I've heard them myself. Churchwardens swearing like bargees—though that was after anaesthetics. Means nothing."

But Arnley did not immediately agree. A vision of Faringdon's horrified face seemed to persist in his memory.

"The bat! The bat!" he repeated almost to himself. "I wonder what he meant?"

EVENTS had moved rapidly a few hours later when a saloon car driven by a plain-clothes policeman entered the gates of the drive leading to the Hall. To his unutterable delight, their progress had rescued Colonel Cheddington from a Church bazaar which his presence as Chief Constable would doubtless have adorned. On the other hand, it had deprived Superintendent Wilkins of a quiet evening at home, and he felt accordingly unamiable. He was visiting the Hall for the second time that day, and as the dark bulk of the house became visible at the far end of the avenue his comment showed that he liked it no better on closer acquaintance.

"Gloomy hole, isn't it?" he asked. "If I were the new heir, I'd cut a few of these trees down and whitewash the place. Might be habitable then."

"Vandal!" The Chief Constable reproached him. "Don't you realise it's one of the architectural gems of the County? Though I admit I'd as soon live in Dartmoor... Anyway, I think young Shelton had better whitewash himself first!"

"I'd hardly say that, sir—"

"You might look on the cheerful side," Cheddington said plaintively. "This is the first murder you've looked like having since I came, and you won't admit it is one! Here's our case. Shelton comes to the ancestral home, wanting cash. Scarsdale is going to give it, but they have a row—probably he cuts him off with the proverbial shilling. That night, the old boy's door is locked for the first time in history. Everyone sleeps the sleep of the just, but he's found dead next morning. Shelton gets fussy, and Arnley demands a post mortem. Then the beans are really spilled; because, as far as they've got, the learned doctors can't find anything Scarsdale died of. But he's dead. And Shelton, as a doctor, should know all kinds of subtle ways of polishing people off. Good Lord, he's spent over six years learning about it—"

"I didn't know that's what doctors learnt," Wilkins interposed drily.

"Well, if you don't like Shelton, there's Faringdon, who faints at the sight of the corpse and burbles about bats. Or Turton, who doesn't seem to have liked the post mortem. Or Benton, the faithful valet, who's so free with his accusations—"

"Or Mrs. Woodney, the housekeeper, against whom there's nothing whatever!"

"That's what's so suspicious. No motive, and no opportunity! Magnificent! Wilkins, if ever you want to commit an undetected murder, make sure you have neither—"

"Then I shouldn't want to do it and couldn't anyway," Wilkins objected reasonably. "Seriously, sir, you think there's something badly wrong?"

"I think the ways of providence are strange—and I've got out of that bazaar... And it's fishy, Wilkins, very fishy, for a nice, respectable neighbourhood—"

The stopping of the car opposite the steps leading to the great doorway interrupted him. He opened the door and got out, standing for a moment to look around the limited prospect which the half light allowed. It was not the first time that he had visited the hall, but he had never before considered it from a professional point of view. Now, in the dusk, the long, low building looked unwontedly sinister. There were lights in the lower rooms; one, at the far end where the curtains had evidently not been drawn, cast a yellow shaft of light on the terrace; but the upper floors were in darkness, and against the sky the curiously-shaped gables stood out in fantastic outline. He was trying, with poor success, to locate Scarsdale's bedroom from his limited knowledge of the interior, when a polite cough made him aware that the Superintendent had joined him and was waiting with obvious impatience.

"Gathering the general lie of the land, Wilkins," he explained. "Most important... Looks the sort of place where anything might happen, doesn't it? Shots from the darkness, ghosts with clanking chains, secret passages—"

"Never ran into any of them myself," Wilkins confessed. "I'm a bit sceptical about—Good Lord! What's that?"

He started back and put up a hand protectingly. Something had whizzed past, almost within a yard of his head. From the deepening grey above a thin shriek sounded. He looked round quickly, as the Chief Constable dissolved into uncontrollable laughter.

"It's a bat, Wilkins—only a bat!" he managed to gasp after a moment. "You see—you're catching the spirit of the place." His laughter stopped abruptly. "Yes, a bat. And, by the way, that's queer. You remember what Faringdon said?"

Without waiting for an answer, he composed his features to an official dignity and mounted the steps. Wilkins prepared to follow him, feeling a little sheepish. He had a real respect for his superior, much as he deplored his impish sense of humour and romantic imagination. And yet, as he stood there, looking over the shadowy garden, he himself was conscious of a feeling not unlike that which must have prompted Cheddington's remark about ghosts. The centuries-old building must have seen so much happen in its time. Even a ghost would scarcely be more out of place than a policeman. All at once he was aware that the door behind him had opened, and that the Chief Constable was already parleying with Slater. He turned to mount the steps.

"Sir Peter out? What, still?... Oh, again. Yes, I'll see Mr. Turton or Mr. Faringdon. Or both. They're available? Good."

Cheddington turned to raise his eyebrows as they followed the butler inside. He did not speak until they were alone.

"Shelton's out—again!" he said. "You missed him this afternoon. Where's he gone now? Not bolted?"

Wilkins shrugged his shoulders. "Probably he's plenty to do," he suggested. "Might just have gone for a walk. Looking over the place, maybe, as he's come into the property."

"Yes. The estate's entailed. Not much else. If Sir Arthur didn't make a will in his favour he won't have gained much... Wonder if they've found the will? And—"

Slater's return made him break off. The butler held the door open invitingly.

"If you'd come to the library, sir," he suggested. "Mr. Turton and Mr. Faringdon are both there."

Following him down the long corridor Wilkins was again conscious of the sensation which he had felt as they waited outside the doorway. Later alterations at the Hall had been confined to the installation of cunningly concealed electric light, and a few improvements to sanitation such as baths, unimportant to our forefathers; and, in the passage at least, the interior must have been very much the same for the last two or three centuries. The first glimpse of the library was almost a disappointment, in spite of the dark oak panelling and Jacobean furniture; for here modernisation had proceeded at least to an extent which made it comfortable. At the far end, an uncurtained French window, must, he thought, be that which he had noticed from the terrace.

Turton and Faringdon rose from their chairs behind a table littered with papers as they entered; and Turton, who, as usual, seemed to have constituted himself spokesman, advanced to meet them.

"Evening, Colonel—good evening, Superintendent. I'm afraid you're luck's out again. He flounced out half an hour ago—young ass! Anything we can do?"

"That depends." Cheddington seated himself in the chair which Turton indicated. "I suppose he'll be in soon?"

"Lord knows," Turton answered disgustedly. "Well, how are things going? The post mortem—?"

"Nothing definite yet. They're analysing things and so on—I'm not up in the ghastly details." Cheddington made a grimace, and no one would have guessed that a study of corpses was among his relaxations. "There'll be an inquest, though, I'm afraid."

"So Wilkins told us. Though I'm hanged if I see why. Arnley was attending him, and he wasn't in any doubt until—"

"He is now," Cheddington said simply. "I see you've been busy here. Found the will? I should have thought this was Shelton's job."

"He's gone out to cool his head—and his temper!" Faringdon had been on the point of speech, but Turton anticipated him, and instead he extended a cigarette-case to the visitors. Turton grinned. "Fact is, we had a row. As it happens, Scarsdale had told us about his will—"

"You've found it?"

"Yes. Ordinarily, we shouldn't have hurried. But the circumstances are exceptional. Had to regularise things somehow."

"It was the will which annoyed Shelton?"

"Partly... I suppose you're hardly interested, but you can see it if you like—eh, Faringdon?"

Faringdon made a gesture of assent. "Personally, I've no objection," he said. "Unless you think you'd better wait for Shelton."

"Don't see why." Turton crossed the room to the table and selected a large envelope. "Here. You'll see, perhaps, why Shelton's cut up."

Cheddington glanced over it in silence for a minute, skimming its contents. Looking at Turton, Wilkins found it easy to understand how his assumption of authority might irritate the young man even without the assistance of the will. Cheddington finished and passed it over to the Superintendent without comment.

"You see, Shelton gets the unentailed estate only when he marries or reaches the age of thirty," Turton pointed out. "Until then, Faringdon and I are trustees, paying him the income or such part as we think fit. That riled him."

Cheddington nodded, not unsympathetically. Faringdon seemed to comprehend what he felt, for he volunteered an explanation.

"You must understand, Colonel, that Scarsdale had reason to doubt his nephew's discretion. And he'd not known him personally. On the other hand, he was a great believer—as a bachelor—in marriage as a steadying influence. He was speaking of it only the night before he died... It rather struck me. He seemed to regard it almost as a settled thing."

Wilkins handed the envelope back to Turton. "No other important bequests," he commented. "A few to servants—five hundred to Arnley. Why was that?"

"Oh, Arnley's attended him for years," Turton explained. "Been paid for it, though... Still, I suppose Scarsdale thought he deserved it."

"The unentailed estate, I suppose, is considerable?"

"Certainly." It was Faringdon who answered. "We've hardly worked it out... Incidentally, there was one thing we ran across—"

He stopped and looked at Turton who nodded.

"Of course. Better tell them. You never know... There may be nothing in it, Colonel, but we found a note among his papers of his having cashed a cheque for a thousand in cash... We've not found where it went to."

"A thousand cash?" Cheddington looked his surprise. "And was that usual?"

"Quite unexampled." Faringdon frowned a little as he answered. "Scarsdale went to the bank and drew it in person five days ago. He never mentioned it. There's no sign of it, or where it's gone."

"He didn't bet?"

"An odd fiver if he happened to go to the races. No more. But that may clear itself up."

"You'll pardon my suggesting it but—well, there's no possibility of blackmail? No women or anything?"

Faringdon shook his head. "Very unlikely. For one thing, I wouldn't care to be the man or woman who tried to blackmail him. And then, he was quite open with us, even about his private affairs. You see, we've known him for years. Turton met him on a big game trip in Africa; I met him the same way in South America. We kept up the acquaintance. Not being married, I think he liked to unburden himself to someone. He was that type."

"Anything to do with Shelton?"

"I doubt it. You see—"

He broke off abruptly as the door opened. It was Shelton himself who entered, and he scowled at the sight of the group by the fireplace. His manner as he advanced towards them was the reverse of cordial. Faringdon hastened to introduce the visitors.

"Oh, Shelton, this is the Chief Constable, and the superintendent. As they missed you this afternoon, they looked in hoping to find you—"

"Yes. Why?"

The answer was blunt to the point of rudeness, but Cheddington smiled.

"Well, Sir Peter, your uncle died suddenly," he explained. "I'm sorry to say the post mortem is unsatisfactory. An inquest will be necessary. We have to make a few inquiries."

"You think my uncle was murdered?"

From the Chief Constable's expression one might have imagined that he was the last person to be capable of such an idea.

"Really!" he expostulated. "At present we can only say his death was unexplained. Several possibilities arise—suicide, for example."

"I see." Shelton smiled contemptuously. "And, of course, I'm suspect?"

Faringdon intervened placatingly. "There's no need to take this attitude, Shelton. You must see that—"

Shelton deliberately turned away from the speaker, facing the Chief Constable defiantly.

"If this is an official interrogation, do I have to speak before these—these gentlemen?" he asked. "If not, I've nothing to say."

Faringdon placed a restraining hand on Turton's arm just in time to avert the threatened outburst.

"If it's agreeable to you, Colonel Cheddington," he suggested, "perhaps we had better leave you? If there is anything further, we can see you afterwards."

Cheddington nodded. He did not speak again until the door had closed behind the two men; then there was a trace of sternness in his voice.

"Making every allowance for your feelings, Sir Peter, I scarcely expected this reception. As a doctor you know perfectly well what happens when a death certificate is refused. You were, I think, the last person to see your uncle alive. Naturally we require a statement from you."

Shelton flushed. "Sorry," he muttered. "I—I've had a bad time to-day. Even the servants seem to think—" He paused. "Sit down, won't you? What do you want?"

Cheddington and Wilkins seated themselves obediently, and even accepted the cigarette which he offered with belated courtesy.

"You broke into your uncle's bedroom with Mr. Turton, I believe," Cheddington began. "What conclusion did you yourself reach, as a doctor, regarding your uncle's death?"

The question seemed to take Shelton by surprise. He hesitated.

"I'm only just qualified," he explained. "I've only hospital experience... Anyway, I didn't examine him."

"But you disagreed with Arnley's view of cerebral haemorrhage, didn't you? Why?"

"Honestly, I don't know... Well, partly, I had the impression that Arnley didn't know, and wanted something nice and plausible for the certificate. Then there was the luminal—more than any sensible person would entrust to a patient at once."

"You know he'd taken luminal?"

"I looked at the box on the table. And the glass had been used. Besides, you could see he had."

Wilkins glanced across at his superior. The thought which was in his mind was that, since Shelton's fingerprints would be on the glass after this examination, there was no way of telling if they were there before. Perhaps Cheddington thought the same.

"Sir Arthur took nothing while you were with him the night before?" he asked.

Shelton flushed. "Nothing," he answered after a pause, and hesitated. "Oh, I suppose you've heard about that. We were having a row. I didn't exactly go to his room to tuck him up. And I wasn't—well, I'd had something to drink."

"I see. Do you remember seeing the pill box?"

"I—I don't know." Shelton fired up suddenly. "I see what you're getting at! Well, I didn't—"

"I didn't suggest you administered it. Your uncle was looking well when you saw him?"

"Probably. He was in the hell of a temper. I know that."

"And you had only recently become reconciled? After you took your degree?"

"Yes."

"Can you give me any idea of how this visit came about? Your uncle wrote to you?"

"Oh yes. He'd seen my name in the list of successful candidates. Suppose he thought I'd turned over a new leaf. He asked me to come here, and hinted that he'd be prepared to shell out a bit. I ought to have been here about eight. But as luck would have it, I ran into some men I knew. We celebrated a bit. I didn't get here till eleven. He was alone here, and was pretty short with me. I lost my temper—then it started."

Cheddington nodded. At some other time it might be necessary to press for further details. Temporarily he let things rest.

"Your uncle hadn't mentioned any specific sum?" he asked. "Say a thousand pounds?"

Shelton looked at him in real or assumed surprise. "Why should he? I didn't owe that much. And, if he was going to help, it wouldn't go far in buying a practice, would it? We'd not discussed details."

"I believe you are informed about the provisions of your uncle's will?"

The young man flushed angrily, and seemed for a moment on the verge of an outburst; but he controlled himself.

"Yes."

"Perhaps your uncle had already informed you?"

"What he'd done?" Shelton broke out. "He did nothing of the kind. He said that—"

"The will was discussed, then?" Cheddington prompted as he stopped. "He said something about it?"

Shelton's face set obstinately. He made no reply.

"Perhaps your uncle alluded to some changes which he proposed?" Cheddington was merely guessing, but Shelton's manner was beginning to irritate him. "Was that it?"

"I've nothing to say!" Shelton snapped out with some violence. "I see what you're after. You can find out for yourself. I won't—"

Right in the middle of his indignant outburst he jumped to his feet. He was staring down the room towards the uncurtained French window and his anger had given place to a sudden amazement.

"What—?" Wilkins began. Both he and the Chief Constable had also risen, and were following the direction of his gaze. "Anything wrong?"

"At the window!" Shelton pointed. "A face—I saw it. Someone was there—"

Wilkins looked his incredulity, but Cheddington had turned in time to catch the merest glimpse of what had startled the young man. He had reached the window and flung it open by the time the others joined him.

All three stood looking out. The faintest possible breeze made a slight sound in the trees, but otherwise everything was still. After the brightness of the room everything seemed black. All at once Shelton started forward.

"There!" he said simply. Almost with the word he had crossed the terrace, jumped down the low wall which separated it from the rest of the garden, and the next minute was lost in the darkness.

Wilkins swore, trying to push his way past the Chief Constable. His one thought was that Shelton was trying to escape. Cheddington put out a restraining hand.

"Wait!" he said. "Listen!"

Only vague noises from the darkness indicated the direction of Shelton's pursuit; then even these died away. The Superintendent was moved to impatient protest.

"He's bolted! Diddled us with that yarn—He'll get away clear—"

"No." Cheddington was still staring in the direction where he had last heard the sounds. "There was something. I saw it. Just a glimpse of something white—moving. I wonder—"

"We'd better search," Wilkins persisted. "They can't have got far—"

"The garden's like a jungle—and we don't know our way about. Besides, I think even Shelton was too late... He's coming back."

Almost as he spoke, the tall figure of the young man emerged into the patch of light from the window. He was coming slowly, looking back now and again, as though expecting to hear something.

"You mean you swallow that?" Wilkins asked. "The questions were just getting awkward—he had to do something—"

Cheddington silenced him with a gesture. Then he called out.

"Any luck?"

Shelton did not reply immediately. He had reached the terrace wall and was just preparing to clamber up when all at once he stooped, disappearing from view. As he rose and climbed the parapet, Cheddington's eyes focussed on the crumpled piece of paper in his hand.

"See anyone?" he repeated. "What's that?"

"There was someone," Shelton said a little doggedly. "I was as near as possible—No. Couldn't tell who it was."

"The paper?" Cheddington took it as the young man held it out and smoothed it flat for an instant before closing his hand hurriedly, crumpling it again. "Where'd you get this?"

"Just down there. Saw something white—What is it?"

Cheddington did not answer. "Shall we go inside?" he suggested, standing aside to let the others precede him. "We can talk there."

On the threshold he stood for a minute looking out before he closed the window, this time drawing the curtain across. He looked at Shelton inquiringly.

"I saw a face at the window," Shelton said. "Something was moving in the garden. I lost it near the trees. Couldn't tell which way to go. So I came back?"

"A face? Man or woman? What sort of face?" Wilkins asked, and the unbelief in his voice was manifest. "You're sure you saw it?"

Shelton stiffened. "Oh, that's your attitude? Well, then, you can—"

"Not at all. I saw something myself." Cheddington soothed him. "That's all you can tell us?"

"Yes. Except the paper. What is it?"

"I'll keep it for the moment, if you don't mind. I don't see that there's much we can do—until daylight... Now, I wanted to look over the house, Sir Peter. I expect you're scarcely familiar enough with it? I wonder if you could find someone—Slater, say, or Mrs. Woodney?"

Perhaps there was relief in Shelton's ready assent. Wilkins frowned disapprovingly. Personally he would have continued the interrupted interview. He was moved to audible protest as the door closed, and they were left alone.

"You're not asking him—?"

"That can wait." Cheddington motioned him again towards the window, drew the curtain and opened it. "Because, you see, there was someone there. Look!"

The surface of the terrace had suffered through the lapse of time and here and there irregularities in the stonework still held pools from the shower that afternoon, though the surrounding portion was dry. Cheddington pointed to a spot a little to the left of the window. The outline of a footprint still damp beside the puddle which had caused it was unmistakable. The Superintendent bent down hastily.

"Good Lord! A woman!" he said. "Who—?"

"A woman," Cheddington agreed. "Here, lend me a pencil."

He stooped for a moment to draw round the drying patch, striking a match as he finished to examine his handiwork more closely.

"That'll do. Now, that will be there to-morrow. Come inside. I expect there are more traces. You couldn't walk on the lawn in those heels without. We'll see to-morrow."

"A woman!" Wilkins repeated as they went back to the fire. "But everyone says that Scarsdale was a hermit—"

"It mightn't be anything to do with Scarsdale. But there's another reason why I want to look round the house. To see if anyone got in. This way we can do it without fuss. You see, there's this."

He held out the paper which he still held, and Wilkins took it. At the first glimpse he started.

"What—?"

It was a bank note for one hundred pounds. He stood looking at it in amazement. Cheddington took it hastily from him and pocketed it as the library door opened.

THERE is a type of person who derives a solid satisfaction from the contemplation of human mortality. Mrs. Woodney, the housekeeper, belonged to it. Funerals were her recreation; death and illness her delight, and hearing her speak of her family misfortunes a listener of sympathetic heart might have been moved to murmur: "What! Widowed only once? Poor woman!" in amazement at the perversity of fate which withheld from her a repetition of what was manifestly the greatest moment of her life. To her list of the good and great who had gone the way of all flesh, she had lost no time in adding the name of her late employer, and the circumstances of death in his case evidently made a special appeal. Of him, his life, and his passing, she talked continuously as she guided the detectives in their tour of the house.

At any other time Cheddington might have found it depressing, but as things were he welcomed it. Before they had left the ground floor he had learnt more of Scarsdale's habits than he himself could ever have known in life. And generally, so far as he could judge, it was a tissue of solid facts about the dead man, only occasionally interwoven with a silver thread of romance. The first occurrence of this, while Wilkins was examining the fastenings of the gun-room window, came as a surprise to him.

"Often he'd sit at that window in the sunset, sir, on a summer evening, looking out over the park," Mrs. Woodney said sentimentally, à propos of nothing in particular. "I've often wondered what was in his mind. Sometimes it's seemed to me that his heart was broken; that he was dreaming of someone he had loved and lost. But there, sir! He won't sit there again!"

Cheddington gulped. From his slight knowledge of Scarsdale, the idea of his being a victim to the tender passion was more than he could swallow. More probably he thought, the baronet's mind had been on the pheasant shooting; but he did not say so.

"It never occurred to me that way," he admitted truthfully. "Of course, he never married. And it would account for the big game." He waved his hand to the trophies which covered the walls of the gun room, in common with most of the lower storey. "Rejected by the girl he loved, he chose going for the lions instead of going to the dogs, eh? Judging by the number of heads, his disappointment must have been serious!"

Fortunately the flippancy escaped his guide. His chance gesture had started her on a new tack.

"Of course, sir, he didn't shoot all these himself. Some were given to him by friends he'd met abroad, sir, like Mr. Faringdon. Why, sir, these aren't a fraction of what he had! He was a great collector. Lots of his heads were shown in museums and places."

"I think I'd prefer stamps myself," Cheddington said gravely. "Do you happen to remember if Sir Arthur ever actually mentioned an unhappy love affair?"

"No, not to say mentioned it," Mrs. Woodney's tone conveyed that, if he had never put the idea into words, his actions had proved it beyond suspicion. "No, he never said anything, but I was always sure myself... And then, sir, look how his heart was set on his nephew enjoying the happiness which he had missed. I believe he'd always hoped to see Master—I mean, Sir Peter's children running about the house before he died."

"That would be why he was so keen on marrying him off," Wilkins observed innocently, and wondered why Cheddington choked. "You remember what Mr. Faringdon said—about the will—"

"Might we look upstairs now?" Cheddington broke in hurriedly, conscious that their conductress was all ears for this latest piece of information. "If you wouldn't mind leading the way, Mrs. Woodney?"

Perhaps it was the hope of gleaning further tit-bits which made her silent until they had reached Scarsdale's bedroom, glancing into the room where Faringdon had slept on their way. She was evidently prepared to indulge in further reminiscences, but Wilkins spoke first.

"I went over here thoroughly this afternoon, sir. Everything as it should be. Both windows open, here and in the bathroom—though the one in the bathroom is too small for anyone but a very small man to get through—"

Cheddington glanced round. Mrs. Woodney offended by the Superintendent's intervention, had withdrawn to a dignified distance and was waiting with a pursed mouth expressing disapproval.

"A small man, Wilkins," he murmured, "or a woman!"

Wilkins started. Like his superior, he was thinking of the footprint on the terrace.

"Yes, sir," he agreed softly. "But there wasn't a trace of anyone having entered—unless they flew. Under the bedroom window at least the stonework would be bound to show marks. There weren't any."

"And the door was locked." Cheddington looked round the room. "Where was the key found? Could it have been pushed under? There's a wide enough crack."

Wilkins shook his head. "Right over here in the corner by the bed," he answered. "It couldn't possibly have been thrown here—either underneath the door or through the window. But, you see, it wasn't far from where Scarsdale's coat was hanging. If he'd pocketed it, it might very well have fallen out when he undressed."

"Yes," Cheddington admitted the suggestion with some reluctance. "And, in that case, I don't see how anyone could have been here at all... But I don't know about Scarsdale locking his own door. And if he did break the habit of years, that's part of the puzzle. Was he frightened? Did he think someone was going to try to get in? Did he expect to be—?" He broke off, conscious of Mrs. Woodney's eyes upon them and walked over towards her. "You saw the room, Mrs. Woodney, before the body was moved. Was everything as usual?"

"Everything, I think, sir. Poor gentleman, he lay there just as if he had passed away in his sleep. Of course, there were the tablets by the bedside, sir. But I've known him take those before, and though I don't hold with doctor's stuff myself, he didn't seem to take any harm. He suffered with his head, sir. From the stomach, if you know what I mean—"

Wilkins scarcely listened as she plunged into a maze of reminiscences about her own, Scarsdale's, and most other people's illnesses. Though he was by no means inclined to agree with his superior's romantic view of the tragedy, going along in the wake of the other two he was wondering about the locked door. Suppose Scarsdale had had reason to fear an attack, on that particular night only, who was his imaginary assailant? Faringdon, Turton, and all the members of the household had been there for several days before, and so far he had heard nothing of any quarrel which might have precipitated a crisis. Except with Shelton. And, of the whole household, Shelton alone had just arrived the night Scarsdale decided to lock his door. Shelton slept in the adjoining room; he could easily have slipped out without awakening the household. Of course, the same applied to Faringdon. But, if Scarsdale himself had locked the door, so far as he could see, no one could have committed murder at all. Then again he mentally excepted Shelton and the doctor. For Shelton could easily, while he was in the bedroom, have slipped something into the glass; or the doctor, who had afterwards taken charge of the pill-box himself, might have given something which was not what it seemed.

By the time he had got so far, they had faithfully traversed the servant's corridor, and glanced into several rooms, including that where Turton had slept. Mrs. Woodney's company, and their extended tour was distinctly beginning to pall upon Wilkins. He had quite satisfied himself that, whatever might have been the purpose of their visitor who had left the note, she had not succeeded in entering the house. He was inclined to call it a day. But Cheddington's zest seemed to be undiminished. He interrupted an interesting discussion on lilies as funeral tributes to point to a door which the housekeeper appeared to have missed.

"Does that go anywhere, Mrs. Woodney?" he asked. "Whose room is that?"

"Well, sir, it's not really used. It leads to the attic steps—it's an attic really, though we generally call it the museum. You see, sir, poor Sir Arthur had a big collection—all sorts of things, far more than he could ever show in the living rooms. And he'd keep little things to remind him of his travels. I expect it would seem a lot of rubbish to you, sir—"

"Not at all. I'd be very interested!" Wilkins sighed as Cheddington opened the door and led the way up the steep staircase, wondering mournfully if the Chief Constable would continue his progress heavenward at least as far as the roof. Cheddington switched on the light and looked round the long, raftered room which evidently extended right over one wing of the house.

"Ah, yes," he commented. "Quite a bit of stuff here, isn't there?"

His statement erred on the side of moderation. Crates, boxes, baskets and miscellaneous objects of all kinds strewed the floor in every direction. Some had been opened; others, apparently, had not been touched since their arrival, and in addition to the specimens visible and packed, Scarsdale had evidently used it as a store room for some of his camping equipment. Cheddington pointed to a pile which lay at the stair-head.

"All Scarsdale's—I mean Sir Arthur's?" he asked. "A pretty mixed lot."

"Oh no, sir. Those were Mr. Faringdon's when he went up the Andes. He left them here, sir... And those cases were his last expedition—the ones that haven't been opened. Those were what he brought back his dead ones in, sir—"

"Dead ones? Why, he hadn't got any alive, had he?"

"Oh, yes, sir. Snakes and all sorts. He didn't bring them here, sir. They were given to the Zoological Gardens... Most of the rest of this belonged to Sir Arthur. That elephant's tusk was from one he shot in Africa. Those boots were Tibetan—queer things, aren't they, sir? He tried to go there, but they wouldn't let him. Those bottles have got lizards and things in them—in spirits, sir. That hatchet..."

Wilkins listened a little absently, reflecting with some sadness that, if Cheddington intended to search the attic and examine all the specimens, they would certainly be there all night. Some means must be found of interrupting the flow of Mrs. Woodney's loquacity. He looked around him desperately, then picked up an object near him.

"A shoe off the horse he used in Canada," she was saying. "That was the time he was nearly frozen..."

"I suppose this is the pump of the bicycle he crossed the Sahara on?" Wilkins interposed sarcastically. He worked it as he spoke. "It's broken anyway. Smashed it mending a puncture at Timbuctoo—"

"The Superintendent will have his little joke, Mrs. Woodney!" Cheddington explained as Mrs. Woodney's eyes opened in astonishment. Evidently she had never before heard this particular piece of history. As he caught the grim look on Wilkins's face, his heart smote him. "It's very interesting. I'd like to look round properly another day. I've just remembered an appointment—"

Mrs. Woodney cast a suspicious glance at Wilkins as he hastened to lead the retreat, though Cheddington lingered even then to throw a last glance round the dusty, lumber-strewn loft. Perhaps he had his reward, for the housekeeper, who parted coldly from Wilkins, displayed more animation in her farewell to him than one would have thought possible for her to feel about anyone who was still in the land of the living.

In the library, they had evidently interrupted something perilously near a scene; the situation was at least strained. In an armchair by the fire, Faringdon was making a strenuous pretence at reading the morning paper, while Turton, opposite to him, bit savagely at his pipe. Shelton had apparently been pacing the far end by the French window. Wilkins wondered whether he was on the look out for a possible repetition of the surprise visit. To his relief, Cheddington did not prolong the agony. His sigh of gratitude was audible as the front door closed behind them. Cheddington heard it and laughed.

"Yes, that's over for to-night," he said. "I'm afraid you didn't appreciate Mrs. Woodney... What a mine of material that woman is! What a trial it will be—in all senses of the word—if we get her in the witness box... By the way, I'll drive. I'm leaving Johnson here."

"You don't think that's necessary?" Wilkins asked in amazement. "Why, so far as our search has shown anything—"

"You forget our lady friend. She might return. Besides, if one, why not more? I'll arrange reliefs, and we'll have an all night watch."

Seating himself in the car, Wilkins was just comforting himself with the reflection that, if he was a sufferer through the Chief Constable's zeal, others would suffer more, when Cheddington's first words as he returned from giving the detective his instructions almost made him revise his opinion.

"Now for Arnley!" he announced happily. "We'll just call round there—"

"Why, I thought you'd finished for to-night." Disappointment was audible in the Superintendent's voice. "And I don't quite see what good—"

"Can't possibly finish before eight o'clock. There's that bazaar... Anyway, Arnley and the police surgeon are foregathering in five minutes or so to greet us. They'll have a more complete report ready then."

Wilkins grunted. "You still hold the idea that it's murder, sir?" he asked. "I should have thought—"

"The idea? Why, it's simply got to be murder!" Cheddington sounded shocked at the mere suggestion that it might have been anything else. "It's a murder, and, what's more it's our murder. I'm not calling in Scotland Yard. Why should they have all the fun?... When we came here, there wasn't much obvious indication except that cautious phone call from the surgeon, and the locked door. Now, there's the missing thousand, the eccentric will, the mysterious lady visitor, the banknote—Wonder if it's one of the thousand pound lot, by the way? We shall probably see when we ask the bank... There are the makings of a first class mystery here—if only the surgeon doesn't spoil things... Any of those three might have done it—Here we are!" He slowed the car to a stop opposite the doctor's gate. "Why, even Arnley might!"

Whether or not it was the result of a guilty conscience, there was undeniably more than a trace of uneasiness in the little doctor's manner as he ushered them into the room where the surgeon was already waiting. Wilkins accepted a whisky and soda thankfully, but Cheddington was obviously on tenterhooks, and eager to dispose of any social preliminaries.

"Well, what's the verdict?" he demanded as he splashed the soda into his glass. "What was it killed him?"

Arnley cast a half-scared glance at the surgeon, who reached to the table at his side and tossed over a bulky sheaf of paper.

"There's the report," he said. "That is, as far as we've got so far... See what you make of it yourself."

Cheddington took the sheets eagerly, but his face fell a little as he skimmed the first page or two.

"It's a nice report," he said hesitatingly; then he winced as a particularly polysyllabic sentence caught his eye. "Really an admirable report! I'll enjoy reading it—in bed... In the meantime, I'd rather you gave me the rough outline. What killed him?"

There was a moment's silence. Arnley and the surgeon looked at each other before the latter finally spoke.

"We don't know," he said simply. "At last—we know why he isn't living, but we don't know how he died. That's what bothers us." He paused a moment and glanced at his colleague. "I don't quite know how to explain to you. Perhaps it wouldn't be a bad idea if Arnley told you the results of his examination the night before again."

Arnley cleared his throat and thought for a moment.

"It's impossible, you see, Colonel Cheddington—quite impossible!" he burst out unexpectedly. There was agitation in his manner. "It's inexplicable! Never in all my years of experience as a doctor have I encountered—"

"Better begin at the beginning," the surgeon interrupted. "How was he last night?"

With an effort, Arnley composed himself, cleared his throat again, and took a drink from the glass in his hand.