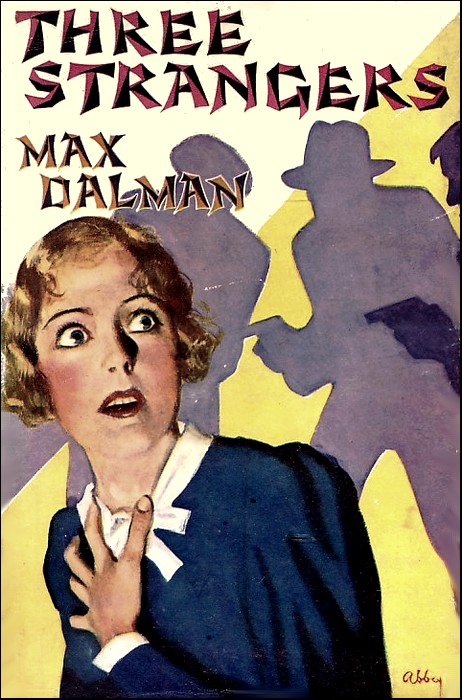

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

"Three Strangers," Ward, Lock & Co., London, 1937

"Three Strangers" is a vintage British detective novel set in the quiet English countryside—but don't let the setting fool you.

On the day of a man named James Remshaw's execution, three mysterious strangers arrive in the small Sussex village of Malford Bishop and make their way to Malford Manor, home to Theodore Hardwick and his daughter, Elizabeth. Each of these visitors has a hidden agenda....

OF Malford Bishop's two hundred inhabitants, only Theodore Hardwick was much disturbed when James Remshaw took his last walk to the scaffold one grey March morning. Even his indignant letter to The Times was partly habit. Every execution in ten years had similarly inspired him, and subeditors who had once condensed his effusions to five-line paragraphs had long since ceased to trouble. It was not that she shared his views, but the merest feminine curiosity which made Elizabeth halt outside the shop to search for her father's letter in the paper which she had just bought. A gust of wind made the flimsy sheets resist her obstinately, but she had just found the page when a violent collision almost threw her from her feet. Extricating herself from the voluminous folds of the newspaper, she looked up indignantly, and the sight of the stranger who had caused the collision gave her a mild shock of surprise.

The immaculate middle-aged gentleman whose hurried progress had been interrupted, smacked of the town from the crown of his neat bowler hat to his aggressively shiny shoes. In the little Sussex village he seemed as much out of place as a cow in Bond Street, and even as she waited for an apology Elizabeth found herself wondering at his presence.

With a singular discourtesy, the man ignored her. He was staring over her shoulder towards the tiny station from which the morning train was just pulling out, staring with a ludicrous expression of incredulity and dread. As she saw the fear in his eyes she turned instinctively to face whatever danger threatened.

There was nothing. In the bright morning sunlight, the winding street wore its usual air of perfect calm. In puzzled annoyance she was on the point of turning again when a muttered exclamation from the man partially enlightened her.

"Lord! It's him!"

It was only then that she noticed the second stranger. He was just emerging from the station, and though he was clearly the cause of the man's exclamation, nothing in his appearance seemed to warrant alarm. Something in the old-world respectability of his dress vaguely suggested to her a dealer in antiques, and his plump, cherubic face beamed with illimitable benevolence. He stood for a moment casting alert, bird-like glances about him through the gold-rimmed spectacles; then, with a brisk, jaunty gait, he moved over to where the solitary pony-cart kept a fruitless vigil for passengers' luggage.

Half-curious and half-angry, Elizabeth faced the bowler hatted man who still stood there. There was a touch of stiffness in her manner as she spoke.

"I beg your pardon!"

The stranger started and looked at her. He seemed to have just become aware of her existence.

"Sorry!" he said curtly. "Excuse me, lady!"

Brushing rudely past as he spoke he hurried up the road towards the church. He was almost running, and his occasional scared glances back towards the station left no doubt about the reason for his haste. Even in her annoyance Elizabeth wondered. The man was thoroughly frightened. He was scuttling away from the new arrival as if his very life depended upon it, fearful of being seen. As the corner hid him, Elizabeth looked again towards the station entrance. Unaware of the hasty retreat he had caused, the cherubic man was talking to the mournful driver of the pony-cart, apparently asking for directions.

It was then she saw the third stranger. In the young man's well-built figure in neat grey flannel, and the handsome, slightly boyish face there seemed nothing extraordinary. His conduct was more peculiar. So far as she could see, he was peeping round the edge of the parcels office doorway, ducking back quickly whenever the cherubic man cast one of his sudden glances in that direction. Plainly he was hiding, but, unlike the man in the bowler hat, there was nothing of fear in his attitude. Whatever the reason for his caution, his movements were adroit enough to escape observation. Still in blissful ignorance of his watcher, the second stranger crossed the road towards her, apparently himself going towards the church.

Elizabeth was aware all at once that she had been staring shamelessly. Before she could look away the man's eyes met hers. In the instant, unreasonably, she felt a rush of terror such as must have affected the man in the bowler hat. In sharp contrast to the chubby, smiling face, the eyes were cold, dead and pitiless and all at once his benignity seemed transformed to sneering cruelty.

It was the merest casual glance. The man paid not the least attention to her, but even as she called herself a fool Elizabeth felt shaken. In her confusion the newspaper slipped from her hand, and as she stooped hurriedly to retrieve it, one page, escaping her grasp, fluttered along the pavement with the unhurried elusiveness of wind-blown objects. Twice she missed it by an inch; then she was aware of a grey-clad figure darting past her.

"Got it!" The triumphant exclamation came just as she realized that the third stranger had come to her help. With a friendly smile he held out the sheet, but even as she stretched out her hand to take it he pounced again, intercepting two white fragments which were quietly making for a nearby puddle. "And these!"

Elizabeth found herself blushing at the ridiculousness of the situation, but the young man's smile was infectious. She laughed as she accepted the errant page and the fragments without looking at them.

"Thank you!" she said. "It was too clever for me—"

"Hasn't the devilish cunning of a hat, though," he responded cheerfully. "Try chasing a bowler down Piccadilly."

As if the thought had reminded him of his quarry, he broke off with a quick glance up the road. Elizabeth looked with him. The second stranger was just rounding the bend, and in a moment would be out of sight. With a smile the young man turned to her again; then a flicker of expression in his brown eyes seemed to show that he had noticed her interest in the man whom he was following. Elizabeth felt herself colouring again at the thought that he might have seen her watching them, but the young man did not appear to notice. Raising his hat, he set off at a leisurely pace after the other two.

For a moment a wild impulse tempted her to follow. There was something fascinating about the curious double chase, and the oddly different persons taking part in it, and though she ordinarily used the field-path which cut off an intervening bend, the actual road to the Manor was the way which the three men had taken. She had started to walk that way when the sight of the man who was coming round the corner made her change her mind and turn hurriedly down the lane which led to the fields.

It was none of the three strangers who was returning. She had recognized the newcomer at once, and for that very reason was anxious to avoid him. Of late, her meetings with John Kinoulton had been rather too frequent for her taste, and her instinct warned her that not all of them were accidental. As a respectable landowner, Justice of the Peace, and even a possible candidate for Parliament, she had nothing against her cousin, but she wished to give him no chance of making a proposal which she had no intention of accepting. Hurrying down the lane with occasional looks back, she gained the fields with a sigh of relief before Kinoulton's tweed-clad figure had passed the entrance.

Only then she became aware of the untidy mass of papers which she was still clutching in both hands, and confident that she was out of sight of the roadway, she stopped to rearrange them. With a little smile as she thought of the young man's boyish enthusiasm in his capture, she had replaced the wandering page, a little muddy from its travels, when something about the two fragments caught her attention. Like the young man, she had thought that they were pieces torn from the paper, and in that belief had accepted them. Now she saw that they were not. They were cuttings from two different papers, carefully removed with a knife, and she turned them over with some curiosity.

"The painless removal of undesirable citizens by legal execution or other means," she read, "may be justifiable and even commendable—"

It flashed upon her what it was. She had no need to glance at the signature below it. It was the letter which her father had written about the execution of James Remshaw. Someone at least had thought it interesting enough to be cut out and filed for reference.

With a slight bewilderment, she glanced at the second cutting. The staring headlines enlightened her immediately.

"Execution of Remshaw," they announced. "Huge Crowds at Prison Gates."

Automatically she read on, but the lines of print brought her no enlightenment. She remembered seeing accounts of the dead man's trial for a murder notable only for its callous brutality. As a thought came to her, she opened the paper and verified the fact that the portion containing her father's letter was still intact. In any case there would have been the second cutting to be explained.

She was thoughtful as she tucked the paper under her arm and, still holding the cuttings, pursued her way across the fields. Again and again she found herself thinking of the three strangers whose curious actions had excited her interest. The cuttings had not been lying there long. Even if one of them had not been from that morning's paper, they were still clean, and the wind would have blown them away. She had a growing conviction that they had been dropped either by the bowler hatted man or by the second stranger with the cruel eyes. She realized suddenly that both had disappeared on the road by which anyone unfamiliar with the village would normally be directed to the Manor.

The thought made her walk more quickly. Neither of the two had impressed her favourably enough to make her wish to have them visit the house in her absence. She was too well acquainted with her father's nature to think that he would be capable of dealing with them. Since her mother's death, she had borne the burden not only of the household duties, complicated by an inadequate income, but of her father's occasional outbursts of generosity which made more difficult a situation which depreciated investments had already rendered almost impossible. In the hands of a clever swindler, he would be like a child at the first mention of the words "capital punishment." The conviction grew in her mind that some such explanation must lie behind her discovery.

At the stile leading into the road, almost opposite the Manor gates, she stopped with an unaccustomed caution to look along the road by which the three men might be expected to come. As far as she could see it was empty, but she waited for a little, half believing that at any moment one of the three might round the bend. The lane was considerably longer than the path by which she had come, and in spite of the start which they had had, she might still have got there before them.

No one came. In a sudden revulsion of feeling she told herself that she was being fanciful. If the bowler hatted man had indeed dropped the cuttings, probably he had no more sinister intention than to request a subscription for some crank society. She had almost decided that her imagination had invented all the peculiarity of the incident when an accidental glance towards the gates made her change her mind abruptly. In a moment her suspicions were renewed. Here, at least, was one of the three.

It was the man in the bowler hat, and if he had indeed come subscription-hunting, his methods were distinctly original. Just inside the gates stood the ruined lodge, burnt out one night eight years before, and owing to lack of money, never repaired. With its boarded windows and fire-stained walls, though the outer shell remained comparatively intact, no one could suppose for a moment that it was tenanted; but the stranger was standing in the neglected garden examining it with the greatest attention. The oddness of his black figure, standing up to his knees in grass and nettles against the background of the deserted house, made her smile by its likeness to some academy problem picture, but something furtive and mysterious in his manner caused her to back into the hedge fearfully as he glanced round. The action reminded her of the other two men. There was still no sign of them up the lane. Looking again at the bowler hatted man, she saw him move to the lodge door and shake the boards which closed the opening. As if satisfied that no entrance could be obtained that way, he made for the corner of the house, apparently to investigate the back, and in a moment had disappeared.

Elizabeth was over the stile instantly. With a single glance up the empty road, she entered the drive and quietly opened the garden gate. As a girl, in defiance of parental warnings, she had thoroughly explored the ruin, and knew that the best method of approach was actually through a window on the opposite side from that on which she had last seen the man. She was conscious of the least touch of nervousness as she found the loose board and pulled it back; then, after a second's hesitation, she climbed on to the low sill and dropped down, letting the board swing back into its place as she looked about her.

Inside, the place was a chaos of blackened heaps of debris and charred rafters, lit only dimly by the light which filtered through the holes in the roof and the planking which closed the windows. It was months, even years, perhaps, since anyone could have been there, and though only a few yards from the roadway, it came to her suddenly that it was a place where anything might happen without anyone being the wiser. There seemed to be something sinister in the smoke-grimed walls and general desolation of the gutted rooms. Then she brushed aside her fears as imaginary. Whoever the bowler hatted man might be, he was certainly not a vulgar burglar of the holdup kind. Advancing a little way into the room she stood listening.

There was no sound, and the very silence seemed terrifying. Her mind began to conjure up gruesome visions of what the man in the bowler hat might have come there for, and she had to force herself to cross the room to the gap in the brickwork which had once been a door. Here it was lighter, the fallen ceiling having left a gaping hole in the damaged roof, but she had to pick her way carefully among the piles of wreckage. Then she heard something. It came from the room beyond, which had once been the kitchen; the ripping of a board from one of the closed windows. Peering round the edge of the doorway, she saw an oblong of bright sunlight flash in the window opening, closed almost instantly by the figure of a man.

As he dropped down, he tripped over a pile of rubbish, and she heard him swear. Somehow the sound was comforting, and it reassured her. Holding herself ready at any moment to dart back into the room from which she had come, she waited, watching the stranger's proceedings with growing interest. Pulling some kind of paper from his pocket, he studied it for a minute in the light that came through the window; then moved across the kitchen to the left-hand wall, examining the floor carefully as though in search of some minute object. All at once he seemed to have found what he sought, for he stooped quickly, and began to brush away the half-burnt laths and plaster which littered the floor.

Suddenly from behind her came a sound which brought her heart into her mouth. It was the closing of the board in the window by which she had entered. The thought of the man with the cherubic face flashed across her mind in a rush of terror. She was between two fires, but even the mysterious man in the bowler hat seemed preferable to the other. He had heard the sound too. Straightening himself, he stood for a second in the attitude of listening. Stealthy footsteps were crossing the room behind her. With difficulty she repressed a desire to scream. The man in the bowler hat moved quickly. In a second he was scuttling for the window, and in another had swung himself through. As Elizabeth made a motion to follow, she heard the footsteps on the very threshold.

There was no time for the window. Before she could have got through, whoever had entered would be in the kitchen. Slipping through the door, she dived for the dark opening which she knew to be the scullery, and with a wildly beating heart gained the refuge of the two walls which had once been the pantry, just as the intruder entered the kitchen.

She heard him cross the room, presumably to look at the broken board, and there was a pause. For a moment she thought that he had gone. She moved slightly, and her skirt brushed the wall, bringing a cloud of broken plaster with it. Slight though the sound was, the man in the next room had heard it. There was the sound of a quick movement; then footsteps crossed the room coming towards her. The suspense was unendurable. Clutching the newspaper desperately, she waited as a dim figure materialized in the darkness of the scullery itself. The paper crackled, and at once the intruder jumped back. From the doorway she heard a sharp question:

"Who's that? Come out or—"

In spite of the threat, the words brought a wave of relief. Obediently she left her refuge and stumbling across the scullery, faced the man who stood before her, gun in hand. It was the young man in the grey suit.

LOWERING the gun hastily he looked at her for a second in blank amazement.

"You!" he exclaimed at last in a tone of sheer unbelief. "You— What are you doing here?"

There was an authoritative note in the question, which nettled her. It was unreasonable enough to be held up at the point of a gun by a trespasser without being asked why she was there.

"I might ask you the same question," she said coldly. "I live here."

"Here?" He raised his eyebrows in a humorous expression with a glance at the ruined room, and her annoyance increased at what she was certain was an attempt at evasion.

"At the Manor," she explained without responding to his smile. "And you?"

There was a pause before he answered, and he seemed to be thinking what to say. Looking at him, Elizabeth decided that the youthfulness of his face was deceptive. There was an underlying firmness in it which made her add five years to his age. On the whole, she decided, it was a pleasant face, but his actions were unaccountable, and if he thought that she could be treated like a child he had to be shown his mistake.

"Well?" she asked.

"The fact is, I'm on holiday," he explained with what seemed to be a burst of confidence; then he paused again. "I mean, that's why I can't tell you why I'm here. Normally, it's the first thing I should do... But, you see, I'm just amusing myself."

"Shooting?" she suggested, and he laughed outright as he looked at the gun before slipping it into his pocket.

"That was a mistake," he admitted. "The truth is, I was nervous... And it was a bigger mistake to stand here in the daylight to hold you up. If you'd been the man I thought—" He broke off again exasperatingly.

"If I had?" she prompted.

"I doubt if you'd have resisted the temptation to plug me," he finished gravely. "When you shoot people, always get them in the light with yourself in the shadow. It's safer."

She had an annoying feeling that he was laughing at her; and yet she was not sure. He gave the advice with a seriousness which almost tempted her to believe that he lived in the reckless manner in which he talked. She hardened her heart.

"I suppose you know you're trespassing?" she pointed out.

"I had gathered it," he assured her. "Though one never knows. There's one right of way I know which goes right through a house—only most people are polite enough to walk round— You see, I was looking for someone."

"The men you followed from the station?"

"You did notice then?" he asked. "Yes—or one of them. The other—well, I don't know where he is at the moment." He passed a hand through his thick brown hair in a gesture between annoyance and bewilderment. But he's somewhere here. And I'm wondering why."

"Then you know them?"

"More or less." His reply was irritatingly vague, but he noticed the slight frown on her face. "A business acquaintance only," he amplified hastily. "In a manner of speaking, we are in rival lines."

The explanation seemed to amuse him hugely, but it did not enlighten Elizabeth, and she felt her temper rising. He was simply playing with her.

"If you won't explain, perhaps you will at least leave," she suggested in her coldest tone. "I have no desire to stand here all day talking to you."

"Now, I could do it myself easily!" His smile almost vanquished Elizabeth. "But then, I've always been fond of talking. Even as a child, and, if anything—"

"Will you go?" Elizabeth snapped rudely.

"If I refuse to go, you're not entitled to use more force than is necessary to remove me from your property," he assured her gravely. "If you are too rough, I can take an action against you for assault."

Elizabeth bit her lip, and then the smile broke through. The young man laughed in sympathy.

"You're talking utter nonsense," she told him, but she smiled as she said it. "And really, I don't want to stop here—"

"I'm awfully sorry." His voice was genuinely contrite. "I do talk nonsense, I know— And I certainly owe you an apology. If only I could explain—" He paused. "You see, I really am on holiday—for the first time for ages—and I'd ruled business out completely, and I was going to Littlehampton or Bognor, or Brighton—"

"Why didn't you?"

The rebuke only momentarily stayed the flow of his conversation.

"I probably shall," he answered. "Unless it's Eastbourne... Because, you see, I saw my two friends on the station just as I was making up my mind which it should be; I was at the booking-office, and I couldn't help hearing what they said. First of all Ted says, 'Third single to Malford Bishop,' and the booking-clerk looked it up in several books, including an atlas and a dictionary of geography, I think, and finally decided there was such a place, and gave him the ticket. And I was just pondering on that remarkable fact and the beautiful new clothes he was wearing and wondering if he was coming to a wedding, when Poldron came up. He peers through the window at the clerk and says, as if he was giving his benediction, 'Malford Bishop, third single,' and after looking it up in a few more books, the man gave him the ticket too. Then it struck me I might as well trail along to make up the party, and I went up to the window and said—"

"Single third, Malford Bishop?" she smiled.

"How did you guess? Well, he was ready for me, though he must have thought it was some kind of an outing, because when he handed me the ticket he looked out a bit nervously, as though wondering whether there were many more, and if he ought to warn them to put on a few more coaches... And the train was terribly slow, though I had two cups of tea and a bar of chocolate... It's all perfectly true."

"It might be, if only one could guess what you meant by it," Elizabeth said cuttingly. "You mean to say you don't know why you're here, or on what business?"

"My business is the same as that of the first and second murderers, whatever that is," he assured her firmly. "I mean the word in its figurative sense— You see, the one thing certain is that they're not on holiday. With either separately, it might have been, but the two together positively shout of something profitable and felonious. So I thought I'd be in on it."

"You mean," she asked in desperation, "you mean that they're criminals?"

"Distinctly so.... Our friend Edward is a sort of Jack of all trades. He must be a bit embarrassed in finding himself in such distinguished company—if he's noticed it."

"He has." Elizabeth recalled the look of fear in the bowler hatted man's eyes. As she thought of the cuttings, her voice faltered a little as she put the question. "The second man—he is dangerous?"

"He's a really nasty fellow." The answer was lightly given, but she knew that the words meant more than they conveyed. "Much worse than Edward... You see, he tries too many different lines. What I say is, if jewel robberies are your line, stick to them, or if it's selling dud stock, don't go further from it than confidence tricks. Now if, as I am almost convinced, Poldron's specialities are blackmail and fencing, they're kindred lines. One helps the other, you see."

For a moment Elizabeth had the thought that he must be making fun of her; the fear came to her suddenly that he was not, and with it the realization of what the fact implied.

"And you—you associate with them?" she asked a little hesitantly. She was half hoping that he would burst out laughing or deny it indignantly. "You are—"

"Force of circumstances," he broke in. "You see I—" He checked the explanation suddenly, and Elizabeth found herself thinking of the gun which had slipped into his pocket so easily. "I don't want you to think—"

"I think it's high time we went." She flushed a little as she spoke. "You—you—" She broke off in desperation.

"But I can explain," the young man pleaded eagerly, but she cut him short.

"I don't want to hear the explanation. You don't intend to detain me here, I suppose?"

"But—" he began in genuine distress. Then with a shrug of his shoulders he seemed to accept the situation. "Not at all," he answered with a rueful smile. "We'll go any time you like. Probably you'd prefer to see me off the premises?"

Elizabeth did not answer. She felt angry and vaguely ashamed of herself, and above all furious with the young man. She ignored the hand which he extended to help her through the window, but in spite of her averted face he walked by her side towards the drive.

"And I still don't know why we're here," he said a little mournfully as they reached the gate.

"I can tell you!" she burst out, and half regretted it the next moment. "It's nothing worth your while— We haven't any money."

The young man paused in the act of opening the gate and closed it again.

"You don't mean that it's anything to do with you?" he asked in manifest astonishment. "How do you know?"

There was something in his tone which in spite of herself made her answer.

"You picked up these." She held out the cuttings miserably. "I hadn't dropped them, but it must have been one of the other two men. You see, my father wrote that letter."

He read the cuttings with puckered brows, and she had to wait, for he was leaning on the closed gate.

"Theodore Hardwick—h'm." He murmured the words thoughtfully. "And there's no reason why— Your father's not a man with a large income and a dark past? or he's not likely to want to dispose of the family plate on the quiet with no questions asked? Or you—your large and expensive collection of jewellery is safely deposited at the bank?"

"Let me pass!" she flamed out suddenly. "I told you there's nothing worth your while. We're desperately poor. It's no use your wasting your time here."

She regretted the words instantly, but they had the desired effect. He opened the gate in silence, and only as she turned up the drive he said a single sentence.

"You know," he said thoughtfully, and in spite of her firmly turned back she heard him, "what you have just said is a great relief to me."

In spite of her chaotic feelings, she found herself wondering what the words meant as she hurried along the drive, resisting with difficulty an impulse to look back. Suddenly the thought occurred to her that the marks of her adventures in the ruined house were probably visible on her face, as they certainly were on her hands. Turning into the shrubbery, she opened her handbag and scrubbed her hands clean with her handkerchief, noting with some surprise that her experiences had left no more deadly trace than a shiny nose. As she repaired the damage, she looked at her reflection a little fiercely. The responsibilities of the household had made it graver than her age warranted, but most men might have found the blue eyes, tilted nose, and rather riotous brown hair attractive. With a little pang, she reflected that the young man had done so. The fact reminded her of John Kinoulton, and she wished rebelliously that the positions of the two could have been reversed. She shut the bag with an impatient snap.

"Elizabeth, you're a fool," she murmured to the vanished reflection, and walked along the path to gain the house by crossing the lawn.

Her face had regained its composure as her father opened the door, and her smile was almost natural.

"You've been hurrying, Elizabeth?" her father asked in mild surprise. "I thought I was late," she answered composedly.

"I've got your paper, Daddy, and they've used your letter—some of it."

"Ah!" Theodore Hardwick's face beamed as he stretched out his hand eagerly to grasp the paper. "Where?"

Elizabeth turned to the page in silence, but at the muddy marks on the sheet which had fallen, felt the question which her father did not ask.

"I dropped it," she explained. "The wind blew it away—I'd better go and see about lunch, Daddy."

With an effort Hardwick tore himself away from the correspondence column where he had found the three sentences which had survived, sandwiched between letters on plant fascination and bimetallism.

"I forgot," he said apologetically. "We have a visitor—a Mr. Poldron—aren't you well, Elizabeth?"

"I have a bit of a headache," she smiled reassuringly, conscious of the pallor of her face. "Mr. Poldron—what does he want?"

Something in her expression as she asked the question must have penetrated Hardwick's thoughts.

"My dear," he remonstrated. "He doesn't want anything. That is to say, he has an offer to make—a most attractive offer."

"He's not been persuading you to buy shares?" Elizabeth's heart sank as a phrase from the young man's conversation came into her mind. "You haven't bought any?"

"Of course not." There was a note of protest in her father's voice, like a man who feels that, for once, he is being wrongly accused. "He never mentioned shares. He wants to rent the house, and the figure he mentioned was—I forget! It was most generous—"

"You didn't accept?" Elizabeth interrupted nervously. "You haven't—?"

"You know I always leave business matters to you, dear," her father answered untruthfully. "I told him that he must ask you."

"I'll see him!" There was a glint in Elizabeth's eyes as she answered. "Where? In the morning-room? No, you needn't come, Daddy. I can deal with him better alone."

She had only a momentary tremor as she opened the door and entered. The man with the cruel eyes rose to his feet as he saw her, and gave a little bow. His whole face oozed benignity and kindness, until she looked again past the glasses of the spectacles. Whatever else the young man might have lied about, she was ready to believe what he had said of the man before her, but she smiled politely.

"Mr.—Mr. Poldron?" she asked. "My father told me of your offer... Won't you sit down?"

Mr. Poldron seated himself obediently, and benevolence shone from his face as he looked across at her.

"Your father, I believe, found my suggestion an attractive one, Miss Hardwick," he said without preliminary. "As he no doubt told you, I should like to take the house for the whole summer, furnished as it is. I would guarantee you against all damage to furniture, and would restore the structure to you in as good a condition as when I found it. In fact, with your permission, and subject to your approval of the designs, I should even wish to do some redecoration and repairs. The rent—"

Elizabeth made up her mind suddenly. She rose to her feet.

"I don't think we need discuss it, Mr. Poldron," she said decisively. "My father and I have spoken about the matter, and though I am sorry to disappoint you, we do not feel that we can let the house."

"The rent I offered was, I think, adequate." There was mild reproof in his tone. "But I am prepared to raise it if you insist... Shall we say fifty pounds more?"

"I am afraid it is useless, Mr. Poldron." Elizabeth had a pang at the thought of the money, but with such a man she felt that she dared not accept. "We are not letting the house."

"To me?" Poldron had risen to his feet, and she felt his eyes almost piercing through her.

"To anyone, Mr. Poldron," Elizabeth answered with finality. "If I may show you out—"

But Poldron made no move to follow her. Instead, he stood staring at her until her own glance faltered and she looked away.

"Sit down, my dear young lady," he said, and there was a steely note in his voice that belied his smile. "Do not decide rashly. I am afraid that I shall have to use arguments which I had hoped would be unnecessary."

Elizabeth longed to refuse, but there was something compelling in the man before her. She felt a clutch of fear at her heart as she obeyed him.

"It is a generous offer, very generous, Miss Hardwick," he said at last, shaking his head. "Believe me, you would do a great deal better to accept. I speak for your own sake. You had better accept."

The threat in his words was plain, and something told her that it was not an idle one.

"You will permit us to judge that, Mr. Poldron," she rejoined a little tremulously. "No matter what your offer—"

"Reflect, my dear young lady, reflect!" Suddenly his voice changed. "Miss Hardwick, my mind is made up. I wish to rent this house—and those who know me generally see fit to give way to my whims. Accept my offer—or I may find means to compel you."

FOR a moment Elizabeth sat still without answering. She was telling herself in her mind that the whole situation was incredible—Poldron's ridiculously generous offer, her own refusal, and his insistent threat. It was even more impossible that she should be sitting there meekly listening to him. It was temper more than courage which made her rise to her feet with a little spot of colour flaming in her cheeks.

"Mr. Poldron," she said very quietly, "this discussion has gone far enough. What your motive may be, I do not know. That you should threaten us—"

Poldron had simply sat there watching her, and all the benevolence had come back into his voice when he interrupted gently.

"Believe me, Miss Hardwick, I threaten nothing that I cannot perform," he purred. "For example, I know to a halfpenny the extent to which this house is mortgaged. How precarious your general position is, you know better than I do. I have here a list of your commitments so far as I am at present aware of them. I would ask you to believe that I am fully prepared in every way. Think carefully, Miss Hardwick."

But it was exactly what Elizabeth refused to do. If she had dared to consider the position, she might have weakened. She faced him trembling, but it was with anger and not with fear.

"Mr.—Mr. Poldron," she managed to articulate. "I have only this to say. If you will not leave, I will have you thrown out!"

Poldron rose to his feet with unruffled calm.

"I am afraid you do not follow my own excellent principles regarding threats," he rejoined. "I know the extent of your household staff, Miss Hardwick—and I doubt if the maid of all work would be equal to the task!"

He moved to the door without another word, opened it politely and bowed for her to precede him; and only on the doorstep uttered a final warning.

"Good morning, Miss Hardwick," he smiled, "you will hear from me again... If you should change your mind, I shall stay to-night at the inn."

Without answering, Elizabeth closed the door behind him. It was only then that she felt the strain under which she had been labouring, and for a moment she leaned against the doorpost before she found the strength to make her way to the kitchen where Mary, the inefficient but inexpensive servant was at her work.

"Couldn't seem to get on no way, Miss Elizabeth," she confided with a bright smile. "First there was one at the door and then another—a gipsy, two pedlars, and the man to read the electric meter."

Elizabeth looked up sharply.

"The meter?" she repeated. "They never read it until the end of the quarter—"

"He said something about a special check, mum. Someone had been cheating the company—only fancy! And he told me how you do it. You run a wire round from the main—"

"You let him in?"

"Oh, I had to, miss!" Mary, especially in moments of emotion, used the two forms of address with sublime impartiality. "They might have summonsed us!"

Elizabeth was thinking hard. The story to her sounded transparently thin, but it was just possible that it might be true. An idea occurred to her.

"Did any of the other men come inside?" she asked.

"Oh, yes'm!" Mary responded brightly. "One of the men had a new clean-all stick, and he offered a free demonstration. Said there was nothing to beat it for taking grease off stonework. And I bet him he couldn't, and he got mad, and tried to show me on the kitchen floor, and it didn't work a bit. I did laugh, miss, and he wasn't half mad!"

"Not the others?" Something in Elizabeth's voice quelled even the maid's flow of light conversation, and she subsided.

"No, miss," she said hastily.

"In future, no one at all is to be allowed in the house for any reason," Elizabeth told her firmly, but with little hope. "I am always to be asked first."

"You or master, miss?" the girl suggested, and Elizabeth caught her curious glance.

The question made the weak spot in her defences all too plain, for her father, she knew, was quite as easy to deceive as Mary. On the other hand, she could scarcely override his theoretical authority.

"Of course," she answered after a slight pause.

She was still wondering what it all meant when lunch-time came. It was a silent meal, for her father, from the way in which his lips moved, was composing some new attack upon the system of capital punishment, and she herself felt anything but conversational. It was only at the end that her father seemed to recall their visitor of the morning.

"Mr. Poldron went away, then?" he asked diffidently, as if he had a vague doubt that their visitor might not still be concealed somewhere about the premises.

"Yes, Daddy," Elizabeth answered in a good attempt at a normal voice. "I refused his offer."

"Quite right, dear, quite right!" he approved absently, and did not speak again until the meal was ended.

By three o'clock she had almost convinced herself that her fears were imaginary. Poldron with his financial threat might cause them annoyance, but he could do little more. It would always be possible to get the mortgage transferred, even if he made the attempt. She could see nothing else that he could do. She was inclined to laugh at her fears regarding the pedlar and the man who had read the meter. If they had managed to penetrate into the kitchen, she could not see what they had gained by it, for if there was one part of the house that could be considered impregnable, it was the back. In any case, the idea of burglars was ludicrous when there was so little to steal.

Sitting at the piano she had played herself back into good spirits when she was suddenly aware of the shutting of the door. She looked round, expecting to see her father. There was no one in the room. For a minute or two she played on before curiosity overcame her. Someone had evidently glanced in and shut the door again, and she wondered who it was.

Leaving the piano, she opened the door gently and looked out.

In the hall, outside, her father was talking to someone. She felt an unaccountable nervousness. Looking round the door she caught a glimpse of the stranger and drew back hurriedly. Evidently her father had seen her, for the next moment she heard his voice.

"Elizabeth! We have a visitor."

She smiled a little grimly. The visitor, whatever his purpose might be, was going to have a shock if she could give him one, but first of all she would hear what he had to say. Perhaps it was another offer to rent the house. She shivered a little at the thought of Poldron; but at least she was not afraid of the bowler hatted man. She was smiling as she advanced to meet him.

"This is my daughter, Elizabeth, Mr. Buckfast," her father introduced. "Elizabeth, this is Mr. Buckfast—Mr. Charles Buckfast."

"Good afternoon, Mr. Buckfast," Elizabeth said dutifully, but added nothing more. "It was her visitor's turn to talk; hers would come later. With genuine pleasure she noted a three-cornered tear in the knee of the striped trousers, due, no doubt, to a stray nail in the window through which he had climbed.

"Pleased to meet you, miss!" Buckfast said hesitantly, but her presence seemed to disconcert him, and reluctantly she was forced to help him out.

"Mr. Buckfast and I have already met, unofficially, Father," she smiled. "He nearly knocked me over in the village this morning! Of course, I didn't know he was coming here—then."

She wondered if the visitor had noticed the pause. If he but knew it, it suggested two coming surprises for him. Whether he had or not, he remained tongue-tied.

"Mr. Buckfast is from Australia, Elizabeth," her father explained. "He knew Jim Shoreham—perhaps you don't remember?"

"Shoreham?" Elizabeth's brows puckered a little at the vague familiarity of the name. "Why, of course—the gardener! Jim would be the son—the boy with the pimples—"

"Yes, dear!" Her father intervened hastily, evidently distrustful of what further reminiscences she might have of the point of view of eleven years old. Then his face seemed to grow inexplicably grave, and his eyes seemed to stare right through them both as if he did not see them. "Jim Shoreham—the son," he murmured almost to himself. "Shoreham was my gardener for fifteen years—"

"It's like this, miss," Buckfast broke in hastily. Hardwick's absent manner seemed to make him uncomfortable. "Shoreham and me were neighbours. Our ranches were next door to each other—we call them ranches out there—"

"Or stations?" Elizabeth suggested with perfect innocence.

"Well, you see, he was always talking of the old place back home, and I got so that I could almost see it. Then, when my uncle died and left me all his money—"

He paused for no apparent reason, and it only occurred to Elizabeth afterwards that at this point in the story he usually mentioned an eccentric clause in the will demanding that he should immediately distribute a large sum among the deserving poor. The necessity for omitting it in the present instance momentarily disconcerted him.

"You thought you'd like to see the reality?" Elizabeth suggested. "I hope it came up to expectations, Mr.—Mr. Buckfast?"

"I've shown Mr. Buckfast the house," her father explained, and the reason for the visitor's colonial acquaintance with the gardener's boy was borne upon Elizabeth. She made a shot at random.

"And the kitchen?" she asked. "A charming old eighteenth-century kitchen! We have a lot of people come to see it specially. Why, only this morning we had two! And then, you're interested in kitchens, aren't you? I knew that as soon as I saw you at the lodge this morning!"

Mr. Buckfast only gaped at her for a moment; then he swallowed hard. He seemed a very simple criminal, Elizabeth thought, but then, one had to make allowances for the fact that he was clearly out of his element. To her father her words were far less intelligible than Greek, a language which he knew thoroughly. He glanced from one to the other in utter bewilderment.

"You saw me, miss?" he managed to say at last. "Then it was you—" There seemed to be relief in his face besides embarrassment. "Of course, I didn't ought to have gone in without permission, but the place took my fancy—"

"And, of course, you knew it was Jim's old home?" Elizabeth helped him. "If I'd known why you came, I should have spoken to you. I expect you thought that it was your friend, Mr. Poldron?"

Buckfast's face went as white as paper. This shot had certainly gone home. It was a minute before he could speak.

"Poldron!" he faltered at last. "He's not— You know him?"

"He called this morning," Elizabeth smiled brightly. "He told me that he'd seen an old friend here who might be calling, and recognized you at once when I described you. He said that he very much hoped that he'd meet you, as there was something he particularly wanted to tell you... In fact, I shouldn't wonder if he wasn't looking for you now. Probably you'll meet him as you go out! He's such a charming old gentleman, don't you think?"

"He—he knows I'm here?" Buckfast was thoroughly demoralized, and with the feeling that she had got him on the run, Elizabeth pressed her advantage.

"He thought of calling back here on the chance of finding you," she assured him. "Let me see—about four, he said. Why, that's only a few minutes now! You'll wait, won't you?"

"Perhaps Mr. Buckfast would have tea," her father suggested. He could not guess at the reasons for his guest's discomfort, but with natural courtesy stepped to his aid. "We should be very pleased, Mr. Buckfast—"

"Oh, you must, Mr. Buckfast!" Elizabeth urged with malicious joy at the sight of his face.

"I—I—it's later than I thought, miss!" he refused. "I couldn't—got to catch a train—"

"What time?" Elizabeth asked. She knew the limited local time-table by heart, but suspected that their visitor did not.

"Four—four-fifteen!" Buckfast lied promptly.

"Surely not!" Elizabeth looked puzzled. "There's no train until—but I'll ring up the station and make sure."

"No, miss! I'll be going!" Buckfast said firmly with a glance towards the door. "Really I won't trouble you."

There was no point in keeping him longer, especially as in all probability Poldron was not coming, but Elizabeth decided to speed the parting guest with a final dig. She wrinkled her brows a little.

"Of course, if you're sure, Mr. Buckfast," she assented. "Oh, there's one thing I was wondering about—if you won't think me impertinent. Father said your name was Charles—"

"Yes," Buckfast assented doubtfully.

"Why did Mr. Poldron call you Ted? I know it's awfully curious but—"

"I—" Mr. Buckfast began. "He always calls me that, miss," he said at last. "Funny, ain't it? I'll be going, and thank you!"

Elizabeth would have let the routed enemy go, and she suspected strongly that Mr. Buckfast sincerely wished there was a train at four-fifteen. In perfect innocence, her father delayed the wretched man a little longer.

"So Jim's doing well, Mr. Buckfast?" he asked earnestly. "Is he married?"

"No," the visitor said hastily. "Yes, he did very well—I'll get along—"

"He's liked in the neighbourhood—respected?" Hardwick persisted, and Elizabeth looked at him curiously. He was asking the question as though it was a matter of primary importance and with a peculiar purposefulness in his manner which she could not understand.

"Yes, he was," Buckfast answered with a desperate glance at the grandfather's clock. "But he—"

"I was right, then!" The triumph in the old man's voice made even their visitor look at him in bewilderment, and Elizabeth was thoroughly at sea. "I was right. I knew it! If he had a chance— You can give me his address?"

"He's dead," Buckfast blurted out desperately.

"Dead?" Hardwick's voice was shocked. "But he must have been quite young—thirty? No, twenty-eight... Was it an accident?"

"Broken neck!" Buckfast answered hastily. "I must—"

"Perhaps you'd see Mr. Buckfast out, Father," Elizabeth suggested. An idea had come to her suddenly. She had better make sure where her visitor was going. With a sweet smile she held out her hand. "Good afternoon, Mr. Buckfast! It has been a real pleasure to talk to you! I'm sorry you can't stay. I'll tell Mr. Poldron."

Buckfast's reply was inarticulate, and as her father led him towards the door, still inquiring about Jim Shoreham, she slipped on her hat and coat and made for the side door. By the time she gained the front of the house, he was already hurrying down the drive, and, running across the lawn, she took the little path through the shrubbery which cut across to the gates.

Suddenly she stopped as a figure darted into the bushes just ahead. The exhilaration she had felt at outwitting one of the enemy seemed to evaporate in an instant. For a moment she stood quite still; then turned and began to walk slowly back towards the house. Brief as the glimpse had been, she had recognized the young man in the grey suit.

SEATED on a damp stone among the rhododendron bushes fringing the drive, Donald Moreton lit his fourth cigarette with a feeling of the deepest gloom. He had really meant to take a holiday. He was thoroughly tired of police, criminals and everyone, and all because of a chance meeting at the station and a girl who would probably never care a row of beans for him, he had missed lunch and sat for hours in a wet shrubbery watching the Manor front door. It looked to him too much like work to be pleasant, and it would have been a comfort of a sort if he had had the vaguest idea what it was all about.

He had seen Theodore Hardwick, the girl's father, whose fatuous letter to the papers seemed to have started the trouble, and it was his firm conviction that a more harmless old gentleman not merely did not exist, but never would. For a dull half-hour he had watched the old man in the garden, apparently shooing wood-lice off the rockery, but the sight had given him no inkling of why his house should have been a rendezvous for one of the finest collections of prize members of the criminal classes he had seen. There was Poldron, who was really dangerous. There was Ted, harmless by comparison. There was a gentleman in artistic overalls who had gone to the back door, and whose face he was almost sure lingered in his memory in connection with robbery with violence, with at least two dubious callers. He had taken the trouble of following Poldron back to the village, where, after a long trunk call, he seemed to have booked a room at the inn. For Ted he had waited a long time before he had finally seen him go up the drive, and even then he was awaiting his return, half inclined, in sheer desperation, to see if he could scare the truth out of him.

Through a gap in the leaves he commanded a view of the doorway. It seemed a long time before the bowler hatted Ted finally emerged, and extinguishing the cigarette, he crept back into the bushes to gain the drive. His quarry was in an inexplicable hurry, and he had to move quickly to gain the edge of the drive before he passed. Diving across a narrow pathway, from a clump of laurel, he was in time to see Ted go past.

Something had evidently disturbed him, and looking at his scared face, Moreton would have given a good deal to know what had been said to him in the house. Ted was looking round him nervously as though he expected to see someone at any moment, and there could be no question of following him along the drive. Slipping back through the bushes, he gained the little path which he had crossed and, judging by ear, kept pace with the hurrying man as well as he could.

He heard Ted cross the place where the path joined the drive while he was fortunately still out of sight round a bend caused by an old yew-tree, and hastened forward so as not to lose him at the lodge gate, with half an idea that he might make another attempt on the burnt-out cottage. All at once he halted abruptly. Ted was talking to someone in the drive and as he listened he recognized the oily voice of Poldron. At all costs he must try and hear what might prove a very illuminating conversation. With the stealth of a Red Indian, he crept through the shrubbery, finally crawling on hands and knees and feeling his way inch by inch to the detriment of his clothes, until he at last gained a point from which he could distinguish the words of the speakers. It was Ted who was speaking in the tone of a man who feels that he has a grievance that he dare not voice.

"But how could I know you were coming down?" he asked plaintively. "I've as much right—"

"How should you know enough to go to the Hardwick's house at all, Bovey? That is what I should like to know." Poldron's words were soft, but there was some undertone of threat in his voice. "Surely you'll be only too pleased to tell me?"

"I've told you!" Bovey said in a tone of desperation. "I just came down to ask about a friend—"

"At the Hardwick's? You're moving up in the social sphere, Bovey. I congratulate you! They may be as poor as church mice—which makes it all the more unlikely that you should try to cultivate their acquaintance, but—"

"He's a servant here—used to be, years ago," Bovey answered. "He—"

"So you do know?" Poldron's quiet voice came relentlessly. "So it was to ask about the gardener's boy, Jim Shoreham, you came? Or was it his ghost? Do you seriously mean to tell me that you don't know about him? I cannot bear the idea of people telling lies—to me, Bovey."

"I've told you all I'm going to!" Bovey said obstinately. "And anyway, you can't drive me off—so if that's what it was you wanted to say so particularly that you had to send a message through that cat of a girl—"

"Through the girl?" There was surprise in the mild voice. "She told you that?"

"Yes, said you were looking for me and wanted me particularly."

"Then, she knows... Or she knows something. That was why she refused—" Poldron broke off exasperatingly. "That's a complication. What else did she tell you?"

"Nothing!" Bovey said surlily. "She—she's a—"

"Hush, Bovey!" Poldron's voice sounded as though he was genuinely shocked. "For your information, I never mentioned you to her. Until I saw you a moment ago, I had no idea you were here. Why you are here, I know, and it is useless for you to deny it. How, I shall know eventually... And in the meantime, I only remind you that most people prefer to leave me alone."

"You can't do anything..." Bovey answered without conviction.

"I'm just remembering all the nice things you say to me, Bovey. And I needn't do anything. I don't mind your being here. If anything illegal should happen, how handy it would be to have someone—an old lag with a bad record—who would naturally take the blame."

"You—you'd frame me?"

"You're getting excited, Bovey," Poldron chuckled. "I wouldn't have to, you poor little rat! You'll frame yourself... Perhaps this interesting conversation has lasted long enough? You will excuse me if I bid you good afternoon... Which way were you going? No doubt to the village. How fortunate! Then we shall part at the gate, and you will be able to think."

Moreton, at least, was thinking pretty hard as they moved away. Poldron, it seemed, was not coming to the house; he must have seen Bovey enter and waited for him. Nor was he going to the village. Unless he was going across the fields, it meant he was going up the lane in the other direction, and so far as Moreton knew, that led nowhere in particular. He had to find out what was taking the more dangerous enemy in that direction, and Bovey could wait.

Peering out cautiously, he at last saw the two men separate at the entrance to the drive, and as he had expected, Poldron turned in the opposite direction from the village. Giving him time to attain a reasonable start, he set off in pursuit.

It was a tricky business following his quarry along the winding lane, and twice Poldron's habit of glancing round quickly almost led to his detection. The lane degenerated steadily, until they reached a point where, turning up through the beech-woods, it breasted the bare slopes of the downs as the merest sunken track. Moreton was puzzled where they could be going, but that was only one puzzle of many. Not least he was surprised at Bovey's unexpected obstinacy. Ordinarily he would have caved in at once when faced with a man like Poldron, and there must be some extraordinarily big prize at stake to tempt him to such competition.

Poldron turned up through the beech-wood, where the dry, crackling leaves underfoot made it necessary to keep a greater distance. Moreton was some way behind when the other emerged on the short turf beyond, and the worst of it was he could not see how he was to get any closer. Almost half-way up, the man he was following stopped in full view, seated himself gingerly, and lit a cigar.

From the edge of the wood Moreton watched him. For perhaps five minutes he sat there without a movement, except for the hand which occasionally raised and lowered the cigar. At last he raised his hands and seemed to yawn. A minute later, Moreton realized that it must have been a signal. Two men had left the cover of the beech-woods from separate points on each side of him and were moving up to join the seated man.

His position, Moreton realized, was one of some danger. The spot was lonely enough for drastic measures, and carefully as he had hidden himself from the man in front, it had never occurred to him to trouble about any possible watchers at the sides. He might very well have exposed himself to their view, but there was no sign of excitement as the two men seated themselves beside their leader and began to talk. Almost certainly they were the salesman and the man in overalls who had called at the house, and it was disquieting to think that Poldron had come prepared to take strong measures to achieve whatever might be his object. They conversed for some minutes, while Moreton reflected that, so far as avoiding being overheard was concerned, they could hardly have made a better choice than that lonely stretch of hillside. Not even a bird could have got near them unnoticed. He could only wait.

All at once one of the men rose to his feet and began to descend the track towards the wood, leaving the other two seated there. From his shelter, Moreton recognized him. It was certainly the hold-up man who had masqueraded in overalls at the Manor that morning, and in a flash he remembered the man's name. It was Strelley. With that recollection came others, far from reassuring. It was Strelley's custom, unusual amongst criminals of his acquaintance, to go armed, and Moreton remembered enough about him to know that he was a very ugly customer. His thoughts flew to the girl, alone except for her father and the maid, in the large, rambling manor-house uncomfortably remote from any neighbours, and he decided quite definitely that there could be no hope of his trip to the sea until Poldron and his assistants at least had returned to town, or were otherwise disposed of.

In the meantime, he had the choice of staying where he was or following Strelley. He chose the latter only after some hesitation. The man might be going back to the house, and he had no fancy for leaving it unguarded. With the additional handicap that he had to watch his rear in case he might be overtaken by the other two, he started to retrace his steps after Strelley.

They had gone only a short way before it became apparent that the Manor was not their objective. Through a white-painted gateway which evidently betokened a private drive, Strelley turned off to the left. With only a wire fence on each side, the route he had chosen led straight over a bare pasture, beyond which a clump of trees and the gables of a large house seemed to indicate his destination. Here again he could not follow owing to the exasperating lack of cover. Through the hedge, he watched helplessly as Strelley opened the gate at the far end of the drive and disappeared among the trees.

Unless he returned to the two men whom he had left on the downs, there was nothing for him to do but wait for the man's return. The visit to the house to which the drive led was puzzling. It was manifestly the residence of some country gentleman, and what took Strelley to it was beyond either his powers of reason or his imagination. The sight of a man driving a timber drag along the lane towards the wood gave him an idea. He might at least acquire information, and as the man drew abreast he stopped him, with a wary eye on the road down which Poldron and the other man might come.

"That'll be Mr. Hardwick's place, Malford Manor, won't it?" he asked. "Mr. Theodore Hardwick?"

"No, sir," the man answered readily. "You've passed it—if you came the village way. A drive up on your right—"

"I made sure this was it!" Moreton answered in feigned annoyance. "Why, who lives there, then?"

"It's Mr. Kinoulton's place—Brinton Abbey, it's called." The man pointed with his whip. "You'll find the Manor just along there, sir."

"Kinoulton?" Moreton echoed. "I don't seem to know the name... Isn't he new here?"

"Why, Lord, no, sir!" The man laughed. "Born here and lived here nearly all his life. He's related to Mr. Hardwick, too. Some sort of cousin, sir."

"It looks a fine place from here," Moreton admired. "Suppose it's not open to visitors?"

"Inside, the finest in the district, I'd say, but then, Mr. Kinoulton's wealthy. Owns half the land hereabouts. Mr. Hardwick could get you permission, I dare say, sir."

"That's a good idea," Moreton approved. "His cousin, you say? Seems a pretty prominent man."

"Justice of the Peace and most other things, sir." The man gathered up his reins. "And, if you'll take my advice, you'll see you don't come before the bench when he's on it whether for motoring or anything you like!"

"I'll try not to!" Moreton laughed. "Thanks. Good day."

There was still no sign of either Strelley or Poldron, and Moreton leant on the gate digesting the information. It helped him very little, unless it showed that the Abbey, rather than the Manor, was the house which was to be favoured with the attentions of the three. Yet he hardly thought so. Everything had pointed to Hardwick's place as the objective, from the cutting to Poldron's visit there in person. On the other hand, the idea that a man in Kinoulton's position could have anything to do with whatever the crooks were proposing was unthinkable.

He was aware suddenly that Strelley was returning along the drive, but he was not alone. Between him and his companion there was something thoroughly incongruous. The middle-aged man to whom he seemed to be talking excitedly must, he was convinced, be Kinoulton himself, and as they came nearer it was plain that he was very angry.

Moreton looked round quickly. He was not sure that Strelley would recognize him, but they would hardly say anything of importance if they knew someone was within earshot. He had to hide, and a gateway on the opposite side of the lane offered a convenient refuge. In a moment he had slipped through, and crouching behind the bank waited for them to approach.

Kinoulton, if it was he, was talking loudly. It might have been Moreton's fancy, but there seemed something besides anger in the voice. It sounded as though the man was delivering some kind of an ultimatum, in which he himself was not sure that he believed, and was trying by over-emphasis to bolster up his own confidence.

"Mind, tell Shoreham once and for all, I won't help him under any condition! And the next time he sends me any request of this kind, the man who brings it will find himself in trouble."

"I only gave the message, sir." Strelley spoke in an abject whining voice which, knowing his character, Moreton found almost comic. "I didn't know—"

"I believe you're together in it. You're getting off lightly. Now, I've no more to say. Clear off!"

"I didn't mean any harm, sir," Strelley persisted. "He said you'd been kind to him before, and might help if you knew how things were. He's in a bad way, sir. Maybe you've not heard from him lately?"

"I haven't, and I don't want to. Go back and tell him. That's enough. If you don't go—"

"Yes, sir—I'm going..."

Moreton heard Strelley turn up the lane towards the downs, and giving him time to get out of sight, emerged from his hiding-place, and with a quick look back to make sure that none of the three could see him, started after Kinoulton. The only risk lay in being seen by Poldron or the other two, and he was inclined to think that it was not very great. In all probability, Strelley had gone back to where the two men waited to report the success of his mission, or its lack of success. Kinoulton did not know him, and would hardly suspect a respectably dressed stranger. He even hurried to get close to the man ahead, and as Kinoulton stopped to light his pipe, acting on the impulse of the moment, overtook him and spoke.

"Excuse me, can you tell me how to get to Midhurst?" he asked.

Kinoulton had started at the unexpectedness of the question, but he answered politely.

"You'll find the turning just beyond the village," he said. "Malford Bishop, that is. It's just ahead. You can't miss it." A pair of keen eyes surveyed his questioner, and seemed to find the result satisfactory. He fell into step beside Moreton as he was about to move on.

"Walking tour?" he asked with a trace of curiosity.

"More or less." Moreton laughed. "I send on my luggage from place to place. Never could see the fun of a knapsack. Then I get there how I like. Thought I'd walk this bit."

"It's a good step, but you couldn't do better." The stern face of the man beside him softened as he looked over the stretch of downs and meadows before them. "I almost envy you!"

"A beautiful country," Moreton suggested in response to his obvious admiration.

"The best in the world! I never want to leave it—again."

There had been a very slight, but perceptible, pause before the last word, but it conveyed very little to Moreton. Kinoulton was very different from what he had expected. On the whole he was disposed to like him; though looking at the firm lines of his face, and the rather tight lips, he did not wonder if those brought up before him on the Bench thought otherwise. The mystery of the connection between him and the man called Shoreham, whoever he might be, was deeper than ever.

They walked in silence for a time, until they had nearly reached the gates of the Manor.

"There's a cut across the fields here," Kinoulton said at last. "It would save you half a mile, or so. See, over that stile, beyond the little copse to where you can see the station there... I turn off here myself."

"Thanks, I'm grateful." Moreton turned towards the stile from necessity. "Good evening!"

"Good evening."

Looking back, he saw Kinoulton turn up the weed-grown drive leading to the Manor.

TO John Kinoulton's disappointment, it was not Elizabeth, but her father, who greeted him as the door opened. Hardwick's obvious pleasure was not unmixed with surprise, for his wealthier cousin was by no means a frequent visitor at the Manor.

"You, John!" he exclaimed. "Come in. I've finished work for the evening. My pamphlet—"

Kinoulton's face softened to a smile as he followed Hardwick inside. He shared the opinion of the district generally that his cousin was a little mad, but to an even greater extent its affection for him.

"Elizabeth—is she in?" he asked with an attempt to make the question seem casual which was a dismal failure.

Hardwick looked at him understandingly as he motioned him to a chair.

"She's lying down," he answered, and noticed that his guest's face fell. "She doesn't seem herself at all this afternoon. I think she has had a trying day. One or two people have been bothering us."

"Money?" Kinoulton asked. "You know, Theodore, that—"

"Thank you, John, but we have discussed that before. You know that my daughter would feel strongly about it, and I entirely agree with her... We can't arrange it that way."

Something enigmatical in the way he spoke the last sentence made Kinoulton look at him keenly. It was almost as though they were intended as a test to himself. Sometimes his cousin puzzled him, and he was inclined to think that he had delusions on other subjects than capital punishment. Then he forgot the impression.

"I can't see her?" he asked, and the disappointment which he felt was patent.

"If you would like, I expect—"

Hardwick had risen to his feet and was moving to the door when his cousin stopped him with what seemed unnecessary violence.

"No!" he cried sharply, and Hardwick looked at him in mild surprise as he resumed his seat. "Better not, perhaps."

He stared into the fire for a moment in silence before he looked across at his host with the air of a man who makes up his mind.

"It was about Elizabeth I came," he said abruptly. "I want to marry her."

Hardwick's eyes studied him gravely, but he did not speak.

"I'm forty-one," Kinoulton continued suddenly. "Perhaps at an age when people are supposed to have outgrown youthful enthusiasms, but I love Elizabeth more than anything in the world. I don't know how long I have loved her. I've realized it perhaps in the past year or so. Lately I've felt I had to speak. Before, I didn't know what to do. I've known Elizabeth as a child for years—and she probably regards me in the light of a grandfather!" He laughed harshly. "I'm forty-one and she—"

"Will be twenty-one in June." Hardwick merely completed the unfinished sentence, and his words were devoid of expression. Kinoulton nodded.

"That was one thing," he said slowly. "Another—well, I wasn't sure how you would regard it, and I think that what you felt would be an important consideration with her."

"I want her to be happy," Hardwick answered simply. "She is like her mother—"

There was a silence which Kinoulton finally broke in a tone of fierce resolution.

"It's no use my going over my qualifications as a husband to you," he broke out. "We're the same family. By sheer luck, I've money and you haven't—and you won't accept it. You know that the will under which I inherited was written in a moment of temper. If he had lived, he might have made a different one entirely—probably would."

"If he had lived," Hardwick interjected quietly.

Kinoulton glanced quickly at his cousin, and for some reason he had grown suddenly pale. There was a pause before he spoke with the slightest tremor in his voice.

"That hardly matters," he said. "I wasn't trying to make out that I was a fine catch because our branch of the family happened to inherit the fortune. I meant that I could support her, that she could have what she wanted... It's no use my going on like this. I want to hear what you think. You know Elizabeth. You've known practically everything of any importance that's happened in my life."

"Yes," Hardwick assented in a voice which was barely audible. "Everything of importance."

His cousin seemed to detect some hidden significance in his tone, for he flushed and his eyes fell.

"I know I played the fool at one time," he said. "That was years ago. Since then—don't you think that a man can ever atone for his stupidities?"

Hardwick's smile was friendly.

"Yes, I do, John!" he said frankly. "Everyone in the neighbourhood respects you. It's not that—"

He broke off, saw the pain in Kinoulton's eyes and made an effort to explain.

"The fact is, it seems to me that it is not a matter on which I can decide," he said at last. "It doesn't matter what I know about you. It is what Elizabeth thinks. And with regard to that, I can only say that I don't know. I mean that she has known you long enough to decide for herself, and it would be wrong for me to attempt to influence her one way or the other... I appreciate your asking me. I certainly shall not try to influence her against you, but, speaking from my own point of view entirely, I think the whole business is a muddle. I had known my wife for three days before I proposed—and she accepted me. We were happy for fifteen years. I have known other cases—" He broke off and shrugged his shoulders. "Years ago I made up my mind that above all others it was the one subject upon which I would never offer advice."

"You mean, I have your permission to ask her?" Kinoulton asked eagerly.

"This is the twentieth century," Hardwick said a little dryly. "Would that make any difference? In fact, has it ever done? I don't know... Of course you can ask her—but not to-night." He smiled. "I honestly think, John, that that proviso is in your interest. She is nervous and excited. I think she is feverish. Whichever way she answered, she might think differently afterwards."

"She's not ill?" Kinoulton asked anxiously. "The doctor—"

"She is only tired. As I said, she was upset by two people who called."

"Who were they?"

Hardwick blinked across at him in mild surprise at the violence of the question. Kinoulton was sitting rigidly, leaning forward a little towards him, and his eyes were burning.

"Oh, there was a man who wanted to rent the house furnished for the summer. Elizabeth dealt with him. I think that he must have annoyed her, for she decided against his offer which was very generous—"

Kinoulton had relaxed and leant back in his chair.

"There's no need—" he began.

"But Elizabeth would say there was," Hardwick answered, and, himself a self-reliant man, Kinoulton felt a sudden pity for his cousin's reliance on his daughter. "The other—oh, he just wanted to see the house. He'd known a servant of the family in the colonies—"

"A servant?" Kinoulton snapped the words. "What servant?"

"I doubt if you'd remember him," Hardwick evaded. "He was, I thought, quite a harmless man. Something Elizabeth said upset him terribly. I didn't understand."

There was a brief silence. Kinoulton made a sudden movement.

"It was Jim Shoreham?" he asked, and his voice had suddenly grown quiet and controlled.

Hardwick hesitated.

"Yes, Jim Shoreham," he said at last. "The gardener's boy. He left us when he was eighteen, and two years after, his mother and father died in the fire at the lodge. It seems that he went abroad, and was doing well in Australia."

"That was all he said?" Kinoulton asked in a voice of unnatural calm. "To you or to her?"

"Not quite," Hardwick answered, and Kinoulton's knuckles clenched whitely on the arms of his chair. "Shoreham is dead."

"Dead?" Kinoulton made a movement as if to rise. "But—"

"Of course, he was still a young man," Hardwick continued as though he had noticed nothing. "It was an accident. His neck was broken."

"Dead," Kinoulton said again and stopped. He looked up suddenly from the fire, and his face seemed to have grown younger. "And you—?" he asked with a smile. "They didn't upset you?"

I was busy." Hardwick's eyes lit up. "I was writing my new pamphlet. It's here!"

Kinoulton smiled again affectionately, but with a trace of compassion.

"You're still trying to reform the world, then, Theodore?" he asked. "And, as a magistrate, I suppose I am, but yours is theory; mine is generally very indigestible fact. I wonder how your theories would work if—"

He broke off sharply, half turning towards the door. For a second he sat as if turned to stone.

"What was that?" he asked in a tense whisper. "You heard?"

Hardwick shook his head.

"Someone—in the hall!" Kinoulton explained. "The maid?"

"She left at six o'clock," Hardwick answered softly, and as Kinoulton rose to his feet he joined him. "Perhaps Elizabeth—"

"It wasn't her step." The positiveness in his voice might have surprised anyone but Hardwick. "It was a heavy step—a man's—"

All at once he slipped silently across the room, flung the door open and stood gazing into the darkened hall. Hardwick joined him, and feeling along the wall, turned the switch. The hall was empty.

"The door!" A breath of cold night air had made Kinoulton look in that direction. "It's open—"

"I very much doubt if I shut it," Hardwick admitted ashamedly. "I am very careless with doors. Elizabeth tells me so. Last week the policeman knocked us up at midnight."

"There was someone—something!" Kinoulton frowned. "We'd better look."

Stepping to the front door, he turned the key in the lock before he led the way to the drawing-room. He had touched the handle when from the dining-room next to it came a deafening crash. Almost knocking over Hardwick, he darted inside and turned the switch.

"Come out!" he commanded. "Come along! You're caught!"

But the sparsely furnished room was obviously empty. Only on the sideboard a heavy gong had somehow fallen from its support.

"Someone's been here!" Kinoulton exclaimed. Hesitating for only a second, he rushed to the windows, and carefully examined the fastenings. In a minute or two he turned to Hardwick with a puzzled face. "Someone was here!" he declared. "Someone must have been... It couldn't have fallen by itself. And no one came out."

He stood looking round him, and then shivered slightly as though he felt the cold.

"It must have been slipping all the evening," Hardwick suggested. "Probably the maid put it wrongly in position." He smiled. "Mary is like that. Elizabeth is the really efficient member of the household. It just slipped."

"It couldn't!" Kinoulton answered almost angrily. "Look at that support!"

He looked round the room again and his face showed blank bewilderment.

"You know the house," he said at last. "I suppose there aren't any secret passages—priests' holes, anything? This panelling—it's old. Perhaps—"