RGL Edition,

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL Edition,

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

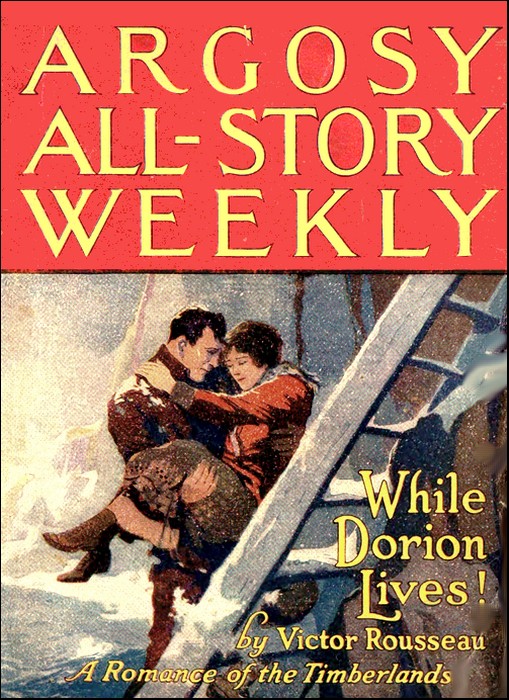

Argosy All-Story Weekly, 27 November 1920

with "The Consuming Fire"

SINCE the days of Bluebeard, the best way to make a man do a thing is to tell him to avoid it. The most jaded appetite tastes the forbidden with a relish. The boy climbs the fence not because he wants to get on the other side, but because the fence is there, telling him to keep out; and the heart of the debutante yearns toward the "dangerous" man whom her mother has "ruled out."

Consequently, though the world lay at the feet of young Ed Raleigh, and he could have traveled to Paris or Pekin with a full pocketbook and the consent of his father, the one region to which his heart turned was the forbidden Bald Eagle Mountains.

It was his father who forbade it.

"In them mountains," he was wont to say, "they's jest enough gold to break a man's heart and turn him into a waster." Yet Pete Raleigh had made his stake and found his wife in those same mountains, and the very ground he cursed was the scene of the tales he loved to spin.

The Raleigh ranch had spread through the length and breadth of the valley, but while this might be called the common-sense kingdom of Pete Raleigh, the kingdom of his fancy to which his memory inevitably turned was the Bald Eagle Mountains—the burned, brown peaks along the valley and the far-away crests of the upper range, blue with distance and tipped with snow.

To young Ed Raleigh that land was a fairy realm peopled with the men and women of his father's stories; and what the ancestral sword, rust-eaten, and the battle-hewn shields were to the young squire of the dark ages, the old mucking spoon and drill set of Pete Raleigh were to his son.

Until finally, having one day ridden a pitching outlaw in a fashion to have swelled the heart of the most hardy bronc-peeler with pride, Ed Raleigh awoke to the knowledge that he was a man. He reasoned, not without justification, that if he could stick to a wild horse without a bucking-roll, he could fight his own way and follow his nose through the world.

When he arrived at this decision the first place his eyes turned was toward the Left-Hand Cut, that deep defile like a knife cut through the Bald Eagle range where the railroad slid over the heights and down into the valley; for the Left-Hand Cut was the gate of fairy land, and in the center of the cut stood the town of Sierra Padre, in whose streets the men of his father's yarns had fought and drunk and gambled and died.

Ed Raleigh was too wise to tell his father where he was going. He merely kissed the white head of his mother, whispered in her ear, and then fled from her tears. An hour later he was plodding down the valley behind a pack-burro and seeing the world through the long, flapping ears in the most approved prospector fashion. And in his hand he carried his hammer, and started chipping rocks within five miles of the ranch-house.

To be sure, he knew nothing, or next to nothing, about ore; but six feet two of arrow-straight manhood, twenty-five carefree years on the range, and nearly two hundred pounds of stringy muscles, hard as sinews, are an equipment complete in themselves. Ed Raleigh did not know the color of hematite from the color of wild violets, but he intended to learn. He was eager enough to dig for the center of the earth, and about strong enough to get there.

Twenty-four hours brought him to the foot-hills, and two days more carried him into the cut. In the middle of the afternoon he drove his burro into Sierra Padre, and paused at the head of the single street. He could have shouted with joy, for everything was in place, everything was exactly as it had been when his father was there. He closed his eyes and winked hard; it was almost as if he were himself Peter Raleigh, not Peter's son Ed.

That shingle on the right announced the Wung Li laundry; the general merchandise sign was just as unreadable as it had always been since Garry the Kid shot up the town. And the horses in front of the saloon were the very horses who had ridden through all his father's yarns since Ed's fifth year.

Straight to the saloon went Ed Raleigh, and strode through the swinging doors; and then he stopped as a man stops in mid-ring when a straight left whacks against the point of his chin.

For behind the bar stood a big-man with grizzled hair and a prodigious paunch. Ed Raleigh winked again and then stepped to the bar.

"Are you Olaf Bjornsen?" he asked.

"Yep—that's me."

Ed Raleigh closed his eyes and clung to the edge of the bar. He felt breathless. Olaf Bjornsen! the same man, the same name. No, there was one discrepancy: the Olaf of his father's stories would have answered, "Ya, Ay bane that Olaf!" It was the son, then.

But the rest of the room was the same. The stove in the center had three iron legs, as it ought to have had, and the fourth one was of wood, black as iron from age and much sooty droppings. The familiar cobwebs trailed across the ceiling of unfinished boards; over to the side a picture of the mighty Salvator spread-eagling his field, and doing a spread-eagle himself to accomplish the feat; behind the bar the resolute face of John L. Sullivan with an American flag draped around his waist—the Boston strong boy in his youth.

It was all the same, down to the smooth, unvarnished surface of the bar—the same bar on which his father had rested his glass of red-eye in the glorious days of old.

"What'll you have?" Olaf Bjornsen was asking.

Ed Raleigh turned his eye to right and left. There were half a dozen other men in the room. That fellow with the scar on his cheek and the sidewise trick with his eyes—surely that was Whitey, the gambler; and the old man with the solemn beard must be philosophic Dan Morgan, who could deliver with equal impromptu ease an election speech or a funeral service. They were all there—all!

"Well?" Olaf was urging with a touch of irritation in his voice. "Come to life, kid. Sleepin'?"

"Come to life!" This fellow's vocabulary was the one jarring note in the entire picture.

"Red-eye," muttered Ed Raleigh, and mopped his forehead.

The bartender stepped back along the bar and picked up bottle and glass; Ed waited, suspended. Ah, there it was! The glass came spinning down the bar, and then rocked to a halt directly in front of him. If this were not the true Olaf Bjornsen, it was surely his reincarnation—Olaf with a twentieth-century tongue.

He poured his drink, raised it, and remembered to toss it off at a single gulp. Remembering again, he pushed the chaser scornfully away. A chaser for a fellow from the mines? Bah!

"New to town, ain't you?" inquired Olaf, eying the untasted chaser.

Ed watched him with incredulous disgust. According to his father, no question were ever asked in Sierra Padre. A man talked of his own volition, or else the town waited to know him by his actions.

"Kind of," he snapped.

He turned to glance out the window over a lordly prospect of rocks and mountains and calling distance, when the doors swung wide and an unsteady figure stepped within them. He was a tall man somewhere between fifty and sixty, and a generation of hard living had whitened his head and seamed his face as weather and a million years have wrinkled the front of Bald Eagle Peak itself.

But he was dressed like a youngster who has lately struck gold, perfect from his new hat to the dark yellow of his Napatan boots. His years sat easily upon him; his step was elastic and quick; his eye danced as he looked around the bar-room, and his body was still as light and gaunt as the body of a youngster in his prime. His working days were far from over; but as he stood there, Ed Raleigh noted an unsteadiness about the fellow which was not the unsteadiness of age.

"It's old Martin," observed Olaf Bjornsen, "and he's starting ag'in."

"He's finishin', you mean," nodded a bystander at the bar. "He's jest about gone."

Old Martin strode to the bar with fumbling steps and leaned his elbows upon it at the side of Ed.

"Whisky," he said hoarsely to Olaf Bjornsen. "Whisky, lad."

Olaf, turning for the bottle, winked broadly at the others; and a tide of anger swelled in the breast of Ed Raleigh. They were mocking the old man. He watched, sternly, with a bright eye. If this mockery went too far, there were ways of putting a period to it. He tightened his formidable right hand tentatively and loosed the grip again. The knowing grin, in the mean time, traveled up and down the bar.

Martin raised his brimming glass. His hand was shaking the moment before, but now it was perfectly steady—rocklike, as the hand of a crack shot when he draws his bead.

"Gents," he said in a deep voice with a little quiver of pathos at the bottom of it, "look at what I got in my hand."

"We see it, Jim," said the bartender sarcastically. "You was always able to keep more in a glass than any one in town."

"That's my reputation," answered Martin proudly. "Well, boys, this is the last drop of liquor that I drink in Sierra Padre! I'm wishin' you all luck! Here's to you!"

He downed the glass, and then turned a watery eye of sorrow on the others.

"Are you swearin' off?" queried Ed Raleigh sympathetically.

The old man looked at htm, and then started.

"You give me a touch, partner," he said, still keeping a keen glance on Ed Raleigh. "But, no, he won't look like you by this time. No, lad, I ain't swearin' off; but I'm leavin' Sierra Padre."

"Never comin' back?" asked Ed kindly. "Where you goin'?"

"To make the honor of Jim Martin clean—the honor of Jim Martin!"

The slight quaver grew more pronounced. From the corner of his eye Ed watched the open grins of the others, and he set his teeth.

"Some one been doin' you dirt, partner?" he asked, and his glance threatened the rest and wiped away their mirth.

"It has been did," sighed Martin. He straightened. He struck the bar with his bony fist, and the glasses danced and jingled. "It has been did!"

"But where you goin'?" persisted Ed. "Ain't they nobody to help you?"

"Nobody," said Martin solemnly. "This here thing lies between me and my Maker. Maybe under the stars I'll meet him and shoot him like a dog; and God will understand."

He looked about him, sighing.

"Joe," he said to the man with the stately beard, "it ain't easy to do it. It ain't easy to leave all you boys. Joe"—he approached the other and clasped his hand—"I know what's goin' to happen to me. I know that after I've killed him they'll get me. Yessir, I'll give myself up. After finishin' him, they ain't nothin' left for me in life. But I'll die happy."

Joe attempted to draw away, but Martin took it for a gesture of persuasion.

"Don't try to talk me out of it, Joe. My mind's set on it like a rock. I'm goin' out to get me a gun, and then I'm goin' down and get the train. I got only half an hour to make that train. And I got to get me some decent clothes. I ain't goin' to face him lookin' like a bum. Joe, I got the money, I got the time; he's as good as dead. But it hurts me, Joe, to leave you boys. It sure do. And to the end I'll be thinkin' of you—thinkin'—"

He choked and covered his face with a shaking hand. Ed Raleigh felt stinging tears in his eyes.

"Before I go," said the old man faintly, "I got to break my vow and have one more drink—with you, Joe."

The bartender, as if he read Martin's mind, was already opposite them with a bottle and two glasses.

"Here's to a quick trip, Jim," said the stately man. He winked cruelly at Olaf. "Are you goin' to give him a chance to draw?"

"Chance? Me? Him?"

Martin finished his whisky hurriedly and smote the bar, coughing.

When he could speak again he cried: "What chance did he give me? No, he played me a dog's trick, and I'm goin' to shoot him down like a dog; and stamp in his face when he's dead! But even that won't bring her—back—to me!"

Big Ed Raleigh shuddered, for he saw a sob swell the throat of Martin, and he had never seen a grown man weep before. But old Jim mastered himself even as his eyes grew dim.

"She's gone!" he whispered to himself sadly, faintly.

"Young man," and here he whirled and pointed a gaunt arm at Raleigh, "beware of women, like you'd be keerful of a pizen-mad dog. Beware of 'em! They sink teeth in you—here!" He touched his heart and then struck it with his fist. "A woman has made me all hollow in here. That's what she's done."

His voice changed. It shook him like a leaf that trembles on the quaking aspen before the coming of the storm; it rumbled from his chest like distant thunder on the mountains.

"But the gent that done me wrong is goin' to die before the sun rises. He's goin' to eat dirt, and die, and watch me laughin' while his eyes get dark!"

He struck the bar again with his fist

"Olaf," he called, "more whisky. I got to drink with this young gent. I got to drink to his health. I got to break my vow about not drinkin' ag'in in Sierra Padre. I got to make sure he's been warned plenty."

And when the glasses were poured he raised his own brimming potion.

"Think of the whisper of a woman like it was the hiss of a snake," he, said to Ed Raleigh; "think of her promises like they was spoke by a Mex—a yaller-hided Mexican greaser. Drink to me, lad, and tell me you won't forget!"

"I won't forget," promised Ed Raleigh, his eyes very wide.

And they drank solemnly together.

"And now, boys," said Martin, turning to the others, "I'm sayin' good-by and God bless ye before I go on my last trail. I'm prospectin' for death."

He raised a forbidding hand, though no one had moved to speak.

"Don't argufy. Don't be persuadin' me. Nothin' between heaven and the Rio Grande can stop me. And, boys, if you got women folk to home, bid 'em say a prayer for the soul of poor old Jim Martin when he's hangin' on the gallows."

He started for the door with long, wabbly strides, his body wavering.

"Good God!" cried Ed Raleigh. "Are you men going to let him go out and commit murder like this?"

He sprang after Jim Martin and caught his shoulder.

"Partner," he said earnestly, "no matter what you got ag'in' that gent, you be thinkin' twice. You ain't spry enough to get away from a marshal after you've pulled your gun. Where you goin'?"

"Down in yonder valley, lad. Leave go my shoulder."

"And what's the name of the man?"

"Pete Raleigh! And he's goin' to die before mornin'."

Ed Raleigh's hand fell, as though paralyzed, from the shoulder of the revenger. He gaped; he tried to speak; and before be could regain his self-control Jim Martin had staggered sidelong through the swinging doors.

When Raleigh came to life, half a dozen men blocked his way and drew him back. And—what curdled his blood—they were laughing.

"Let me go, you fools!" shouted Ed Raleigh. "Let me go, or there'll be some busted heads in here! Lemme go! He's heading down the valley to murder my old man."

"Hold on!" urged the white-bearded man, wiping tears of pleasure from his eyes. "Old Martin has been startin' down the valley after your dad's hide for twenty-five years and more; and he's never got away from Sierra Padre more'n once."

Ed Raleigh stopped struggling.

The amusement on all the faces around him was too genuine for a bluff.

"But what in the name of God does it all mean?" he gasped, bewildered.

"Are you Pete Raleigh's boy?" queried the stately elder, stepping closer. "By the Lord, I think you are. You have the look of Pete, as I remember him. Same dark, thin face. So you're Pete Raleigh's boy! I'm Patrick Swanson."

"Pat Swanson!" breathed Ed. "Why, you're the sheriff—"

"Not for twenty years," chuckled the old man. "I see your dad ain't quite forgot me, now's he's rich 'n' all that. Still remembers the sheriff and—"

"And the Taliaferro gang."

"Righto!"

"And how you fought Bud Jackson on the—"

"Morgan claim."

"Yes, yes!"

"Sheriff, it's sure great to meet you; but ain't there really no danger from old Martin? He sure talked like death and killin' and gun-play."

"Didn't he, though? He's been talkin' like, that, off 'n' on, for these twenty-five years—ever since your pa pulled his stakes out of Sierra Padre."

"But what's he mean about a woman? Dad was always straight, as far as I know."

"He's talkin' about Bess Devine."

"My mother! The infernal old fool, I'll—"

"Easy, lad. They ain't no harm in him. So Bess is your mother, eh? Last we seen of her was when she eloped with your pa."

Ed Raleigh scratched his massive head, frowning.

"But what does Martin mean by this rotten talk?" he. frowned.

"It's always this way. Ill tell you the yarn.

"Back there in the old days when Sierra Padre was first boomin', after gold was struck in the Bald Eagle, Bess Devine was the prettiest girl in the town. For a minin' camp, she was almost too pretty to be good. Mind you, I don't mean your ma wasn't the straightest, finest girl that ever stepped; but you take the finest kind of girl and put her down in a gang of men, without no competition to speak of, and she gets a lot of funny ways with her eyes.

"Speakin' in general, Bess played tag with the whole camp.. She could pick a man up with her eyes, and make him drunk with a smile, and then she slipped away to the next man. They was considerable Irish in Bess, which they's some in me, too. I understood; but they was a pile that didn't.

"When we give a dance, mostly the men was dancin' with each other. We'd tie a red string around the arm of some of the gents, and they was the ladies; and the others danced with 'em. But Bess was an honest-to-God girl, and they was always a crowd around her. She could pick and choose from a hundred, always. And she did do her pickin', right enough.

"She had her favorites, and she danced with 'em, but she always give the ones she left behind her best smile and her best look under the lashes of her eyes. Gives me a thrill yet to think how Bess used to handle us. She always made the ones she didn't dance with feel like she really wanted to dance with 'em more'n with any one else in the room—but they jest hadn't happened to ask her first.

"She was the kind of a girl, lad, that a man would see jest once, and then keep dreamin' about her for a year or so afterward. That's the kind of a girl she was. I can see her yet driftin' through a crowd, shakin' hands with newcomers, smilin' right and left, and sowin' the seeds of hell-raisin' all around her.

"Her eyes was as blue as the sky and her hair was as black as midnight, and they was a ripple like runnin' water in her laugh that started at your head and wound up in a shiver at your feet. That was Bess Devine—your mother.

"Well, among the other suckers who couldn't read Bess's mind, along come this Jim Martin. He seen her in the street and stopped and gaped at her like she was a fish out of water. And then he went to the dance and seen her again. And somehow—I think they'd been a fight between Bess and your pa—somehow Jim got the bid to take her home after the dance; and he was so proud he couldn't hardly see a step in front of him.

"The next day he started off straight for the mountains. He had his outfit, and he was goin' to find gold.

"Couple of months later on, your pa ups one day and elopes with Bess and goes away, down into the valley. He had his stake, and the only thing that'd kep' him in Sierra Padre some weeks had been Bess.

"Well, about the next day, down comes Jim Martin out of the mountains with sixty days whiskers on his face and his saddlebags loaded with ore. Whiskers and all, he goes straight for the cabin of Bess—and learns out from her pa that she's gone. And her pa didn't spare no words when he was talkin' about Pete Raleigh. I know, because I was sort of lingerin' around, and I heard, and what between old man Devine and young Jim Martin, it was the most outcussin'est time I ever heard. It laid over anything the Taliaferro boys ever done after I got 'em rounded up.

"After a while Jim comes back to the saloon and starts drinkin' and tellin' the boys that he was going down into the valley to catch the gent that run off with his girl. First he allowed that he'd get fixed up. He was goin' to look his best when he went down there. Because he wanted to kill your dad and then let Bess see what she'd missed by not takin' Jim Martin.

"Them was the days when I racked a star inside my vest and a forty-four—old style—on my hip; and I hung around promiscuous, waitin' to land on Martin before he left town.

"He'd cashed in with his gold and was loaded with yaller-boys, and he spent the whole day throwin' money away. The saloon got a lot of it, and his hand got so shaky that he couldn't handle his razor, so he hired a gent to shave him and give him a round hundred for the job. Then he went over to the store and got the best they have in the line of clothes. When he comes out of that store he was about the slickest thing we ever see here in Sierra Padre.

"Next he comes down the street and buys him a six-shooter. It was a beauty, and in them days it was a treat to watch Martin handle a gun.

"After that he comes back here to Olaf's place, all lit up already, and starts sayin' good-by to the boys. It took him a long time, because all the boys was fond of Pete Raleigh, and they tried to persuade Jim to stay quiet. But Jim Martin kept right on, and every time he said good-by he said it was the last drop of liquor that would pass down his gullet until he'd dropped Pete Raleigh in the dirt and stepped on his face. But every time he'd see some other friend of his and have to have jest one more drink.

"And every time he had another drink he set 'em up for the house and didn't ask for no change. Takin' it all around, it was a pretty fair payin' afternoon for Olaf's place. And Jim's money kept goin' like water.

"Pretty soon, down the street we heard the train whistle, and that was the train that Jim wanted to catch to get down into the valley. So he lets out a holler for the engineer to stop for him—like he could 'a' been heard—and starts runnin'.

"But he was overbalanced with red-eye, and when he got outside the door he doubled up on the steps and puts his head on the floor and went to sleep, peaceful as a kid.

"The train pulled out, and Jim Martin wasn't in the coaches. The next mornin' he woke up broke. Somebody'd rolled him for his wad, what he hadn't spent. All he had was his fine clothes and his gun. Well, he wasn't goin' to be able to walk down in them boots a three-day trip, and, besides, his clothes was sort of messed up from lyin' on the steps of the saloon. And he wasn't goin' to go down and do that killin' without bein' able to show himself all dressed up fit to kill to Bess afterward.

"The-end was, Jim Martin traded his gun and clothes in, and-borrowed a stake, and started out prospectin' again. It was two years, pretty near, before he come back, and then he come back with a nice lot of stuff and cashed it in proper. We'd all forgot about Bess and Pete by that time, but Jim Martin hadn't. He'd been off there in the hills swinging a pick and cursin' Pete in time with the swing of it.

"He started right in on the same program. He was jest burnin' up with hate for Pete. It was a sort of consumin' fire in him, like the sky-pilot says. He begun spendin' money real liberal; he bought fine clothes again, got him a gun, and then he bought him a ticket for the valley.

I wasn't sheriff no more then, so it wasn't no trouble of mine. Besides, I didn't have no hankerin' to mix things with Pete without it bein' my own fight, I jest sat back on my haunches with the rest of the boys, and Jim kept on swearin' that not another drop of red-eye would flow down his throat, and then havin' another drink, and gettin' real sad, and weepin' over the boys, because he wasn't never goin' to see them again.

"We begun makin' bets about whether he'd be too drunk to get to the train when it come in; but the boys that bet against him lost their money. He jest lasted to the train and got inside and done a flop in his seat.

"They was considerable excitement, and the boys sent for the sheriff. But before he got there the mornin' train come through the next day, and off of it stepped Jim Martin, bilin' mad.

"After a while we found out what had happened. Before his train got to the station down in the valley Jim was sleepin' sweet and soft and peaceful with his head on the arm of the seat. When he got to the station the conductor threw him off and left him on the platform.

"That was late in the evenin', and they wasn't nobody jest then in the station house. When the station agent come out in the early mornin' he seen Jim Martin still lyin' on the platform, smilin' in his sleep like a new-born baby, and he jest nacherally figured that Jim had come to the station to get a train and had been too drunk to quite make it. He seen how much money they was in Jim's pocket, and it was jest enough to take him up the line to Sierra Padre. Believe he kept Jim's gun for a souvenir.

"The agent got him a ticket and took the money and put Jim Martin aboard the first train to the cut. Jim come to on the way, and after a while it sort of soaked in on him that he was travelin' toward the mountains when he should have been travelin' away from 'em.

"He wanted the train stopped, but the conductor wouldn't do it. Then Jim was goin' to kill the conductor, and a lot of the gents on the train draped themselves over Jim to keep him quiet. They wasn't none too gentle, and when they got through with him Jim looked like he'd been fightin' a mountain lion, he was that tore up.

"Well, for a couple of days he went stompin' around town, cussin' his luck. Then he settled down when he couldn't bum no more drinks offen Olaf. He got another stake and hiked for the hills again. That's been goin' on ever since. This makes about the sixth time he's come down to town. Every time he goes back up to the hills and works away in the mines. Then when he has a little stake he takes it and goes off prospectin' by himself. Usually he makes some sort of a strike and stays with it till he gets out the easy pay.

"Then he comes down here rampin' and ravin' and cursin' Pete Raleigh and makin' lectures about what women ought to be and what they are. He always starts drinkin'; he always starts throwin' his money away, because they ain't anybody more generous than old Jim Martin. But after that second time he ain't never got as far as buyin' his gun."

The door opened; Peter Raleigh stood in the entrance. He was a very big man by nature, but with the light behind him he looked to his son like some biblical giant. That shaggy beard which was the despair of Mrs. Raleigh now flared out a little on either side, clotted with the dust and sweat of long riding, so that he looked as if a strong wind were still blowing against his face.

His coming made a little pause through the bar-room, and when he thudded heavily across the room all eyes jerked after him, stride by stride; he came to a pause before his son.

"Well, my fine young snapper," he roared, "what in hell might be the meanin' of this?"

His voice was made for the open; it raged and echoed through even the big bar. Ed Raleigh screwed up his courage and tried to match that volume.

"I'm starting for myself," he answered.

"You are, eh?"

"I sure am!"

"You're goin' to loot the mountains, maybe, and come back with a million inside a year, eh? You young, fool," snorted Peter Raleigh, gathering head, "I tell you, you're going to hit the trail home with me."

As a rule, he had his way with his family, and he would have had his way again had they been alone, but it seemed to Ed Raleigh, staring miserably past the shoulder of his father, that he surprised a meager, inward smile just twitching at the lips of Olaf, the bartender. It maddened him.

"Where you start for ain't my worry," he said quietly. "You go down into the valley or keep on into the hills. I won't stop you. No more will you stop me where I want to go."

There was a certain acid in the cool tone of this announcement that shocked Peter Raleigh back to good judgment; his wife had the same quality of voice when she was driven into a corner on some subject near to her heart.

"Don't you be sayin' things you'll be sorry for later on, Eddie," he said more gently. "You and me are going to walk outside and talk things over. Come along."

But once more Ed Raleigh saw a smile pass between Olaf and one of the others, and he grew hot to his hat-brim.

"What you got to say," he declared, "you can say right here. This was a good enough place for you to start talkin', and it's good enough for you to finish in. I can stand it if you can."

Anger always made Peter Raleigh half devil. He stood swaying with sudden passion.

"Now, by God!" he thundered. "You hear me, young gent, you start for that door or from this minute you ain't no—"

The door swung wide; a gust of voices rolled in from the porch, and then the loud tones of Martin.

"Come on in, boys, and have a drink. You'll need liquor before you come to the end of this here story. It's sad and ornery."

He came first, a trifle unsteady, and behind him were several who obviously had just come down from the mines.

"Dad," whispered Ed Raleigh, the color rushing from his face, "for God's sake, make your getaway. This is Martin, and he's lookin' for you with a gun."

"Martin?" Big Raleigh wavered, and then shrugged back his shoulders. "I've never sneaked away from any man, and I ain't goin' to begin now."

And Ed, knowing that this was irrevocable, stepped back and prepared for the fight.

"Are you still plannin' for that train?" said Olaf to Martin,

"And I'm goin' to get it. Olaf, I want you to know my friend, Bud Hendrix."

He waved forward a huge, black-bearded man.

"Bud has guaranteed to get me to that train." He turned. "Step up, boys, all of you. My dust ain't run out yet by a hell of a long ways." Here his eye fell upon big Raleigh; he halted, and then walked straight across the room and paused a pace away from Peter.

With a hand on his gun, Ed waited for the lightning move, the flash of steel; and in his heart he had never admired his father as he did at this moment, for the big man did not stir a hand. He waited for the other to make the decisive move.

"Stranger," said Martin suddenly, "you might as well know what's comin' off. Come and liquor up and hear a story what every man ought to know,"

"He waved toward the bar, and Pete Raleigh, after an instant of hesitation, smiled quietly and followed. As for Ed, he was ready for the trouble which he thought must come.

"Got your eye on the time, Bud?" asked Martin.

The other exposed a huge gold watch. "I'm watchin' every minute. If what you say is right, that gent ought to die, and I'll help you on your way."

"If I'm right?" roared Martin. "Don't the whole town know how Pete Raleigh done me dirt and sneaked away my girl and married her?"

By his side Pete Raleigh straightened, and for a moment Ed thought that the dénouement was about to come; but then he saw his father relax and watch Martin with an odd smile.

"For twenty years," said Martin, "I been hungerin' to get at him. For twenty years I been burnin' up with fire to see this gent face to face. And now the time has come."

Ed Raleigh shuddered, but his father had not stirred. He still stood there at the side of Martin, looking at the avenger with the quiet, reminiscent smile. Every one had taken his drink, and it was Pete Raleigh who proposed the toast.

"Martin," he said, "here's hopin' that you meet Pete Raleigh face to face—as close as I'm standin' to you now."

"Ah!" groaned Martin, and tossed off his drink. "Stranger," he went on, laying a hand on Raleigh's arm," I like you. You got a straight look about your eyes. Well, so-long. I got to go down and kill Pete Raleigh; this is my last try, and if I don't get him this time in the valley I'm goin' to call the deal off. When I come back, partner, I want to see more of you."

"Thanks," said Pete Raleigh. "Go get him."

"Time up!" barked Bud Hendrix.

"Wait a minute," pleaded Martin. "I got a gent here that can understand, and I want him to know—"

"Don't you hear the train whistlin'?"

"Damn the train! Partner—"

But Bud Hendrix was a man of his word. Far away the train hooted around the bend, and Bud, fixing one brawny arm under the shoulder of Martin, caught him with the other hand on the opposite side and fairly lifted him toward the door.

"When he's dead and buried," shouted Martin over his shoulder, "I'll come back and see you again, stranger."

Pete Raleigh waved his thanks.

"Set 'em up, Olaf," called Martin as he was borne through the door. "Set 'em up for all the boys, and I'll pay when I get back from makin' Mrs. Pete Raleigh a widow."

IT was some time later that Peter Raleigh remembered the mission which had brought him back to Sierra Padre, but when he turned his son was not in the saloon. He went hurriedly into the street and peered up and down, but there was still no sign of Ed Raleigh.

For far up the side of Bald Eagle Peak, steering his course through the ears of his burro, Ed Raleigh was voyaging into the old land of his father.

IN the mean time, notwithstanding the assistance of Bud Hendrix and his gold watch, Jim Martin again missed the train.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.