RGL Edition, 2025

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL Edition, 2025

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

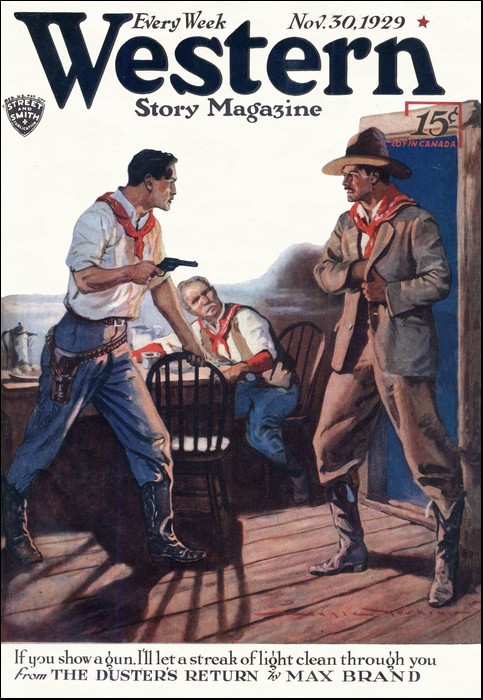

Western Story Magazine, 30 November 1929,

with "The Duster's Return"

THE face of Renney was never greatly welcome around the Ridley house, while The Duster and I were staying there. Of course, The Duster had the best reasons in the world for not wanting to have a sheriff around; and though I've luckily kept out of danger of the law, still no man likes to have the shadow of the jail falling across the toes of his boots, and every time I see a policeman I begin to think back to the time when I stole apples, and swiped watermelons in the moonlight. But this afternoon I was less glad than ever to see the sheriff riding in from the road through the trees.

For one thing, it was hot, and when I say hot I don't mean what they call in the East "that dreadful humidity." No, I mean the dry heat that they tell you in the West is so healthy. Maybe it is. So is an oven then. Everything felt it. The bluejay that went overhead like a jewel seemed looking for shade more than mischief, and the two squirrels that used to scold me every day at the top of their lungs, now moved slowly through the branches of the trees and only swore at me now and then, softly, as though they were saving their breath. It was so hot that the sun fire heaped up higher and higher on the naked ground outside the grove, so that you could see it shimmering like water, and looking through it the mountains appeared out of joint, as though they were reflected in a cheap mirror. Then, now and again, the wind rose just strongly enough to topple that pile of flame and send it invisibly sliding and pouring in among the tree trunks. When it reached me, it burned the damp back of my hand dry in a minute and made the hairs stand up and the skin prickle; it burned my eyes and slid like scalding water down my neck. On that day, there was no comfort except in a pipe and in looking down the hill through the trees to where the Christmas River was running pale blue, like the sky, with a white cloud or two stuck in the quiet shallows at the bend. Talk was the last effort that I wanted to make. I had finished the lunch dishes and scrubbed out the kitchen and had everything ship-shape, and I swore that the only hot thing The Duster should have for supper would be coffee, so that the afternoon lay ahead of me as restful as the run of the river itself. Even thinking was hard, and it was better to watch the brown trunks turn into green leaves and needles, and the foliage turn into the sky, and the sky turn into the great white sun flare that was traveling slowly west toward the horizon.

But there came the sheriff on the same runty mustang that he usually rode, biting at its bit, jerking out its head to make the reins slip through his hands, and always hunting for half a chance to get hysterical or just plain mean. He had an eye as red as a ferret's, and looked as though he lived on raw meat. But there was Renney in the saddle looking tired, not of the horse but of things in general.

He looked like a tramp. He hadn't shaved for a week, and his nose was whisky-red from the weather, and he wore an old red-flannel shirt that was sun-faded to a dirty pink over the shoulders, and caked with dirt and dust.

He came up, drew rein, and dismounted with a jingle of spurs and groan of stirrup leathers, while the mustang tried to take a piece out of his shoulder. It missed, and threw up its fool head and stuck out a stiff upper lip, ready to receive what it deserved. Renney was too tired and hot to bother with that, though, and he only made a threatening motion with his hand. I waved my pipe at him by way of greeting.

"Is The Duster here?" says he.

"The Duster ain't," said I.

"Rode out?"

"Yes."

"When is he due?"

"Don't know."

"You're glad to see me, it look like," says Renney. "Shall I sit down and rest my feet? Thanks, I will. You got a pretty cool place here," says he, as another wash of the sun fire came drifting through and burned me to the bone.

He wasn't joking, either. He'd been out where the air was all aflame and this shade felt good to him.

"How are things?" said Renney.

"Fair," said I, seeing that he was bent on talking and making sure that I wouldn't say a word. Because I guessed that he wanted me to talk about The Duster, and I knew too much about him to get going on the subject.

"You got a toothache, maybe," suggested Renney, arranging himself beside me on the doorstep, "and don't want to open your mouth and let in the cold air?"

"Renney," said I, "what are you after?"

"Ideas," said he.

"About what?"

"About The Duster."

"I'm glad you let me know," said I. "I thought that maybe you'd ridden over this way for the sake of the scenery, or the exercise, or something."

Renney grinned, but the smile didn't last long.

"Old son," said he, "how long are you going to stick with this?"

"I'm leaving in a coupla days," said I.

"You said that last month."

I sighed. It was true. Every day I told myself that The Duster was a crook and that if I didn't look out, he'd make me another. But every morning I put off leaving until the next day.

"He's got a hold on me," I admitted.

"He has on me, too," said Renney.

"Aye," I answered, "but not as big as you'd like to have on him. With handcuffs, if you could make them fit!"

"Sure—at first," said he. "But I'm not so certain of that now."

He stopped in the making of a cigarette, a sure sign that a man is dreaming. It began to seem to me that he was thinking out loud.

"I don't make him out," says the sheriff. "We know that The Duster is the best all around gunman and yegg and slick gambler in this part of the world. He'd admit it himself! But in the midst of his fame, as you might say, and while the world is still at his feet, what does he do but chuck everything, as far as we can see, and come here to settle down?"

I thought of the Muncie bank robbery, but I didn't speak, naturally.

"Then," went on Renney, "he makes a grand play to get permission of the minister to bury the ashes of his old partner, Manness, up there in the cemetery, and though the minister fights hard, somehow The Duster manages to get the thing done—I don't know how. Then he makes a play to get young Tommy Lamont over on his side, and the first thing that you know, we find Tommy carrying hundreds of thousands of dollars of stolen money; and Tommy's jailed; and The Duster gets him loose!"

"Does he?" said I innocently.

"You know he did," said the sheriff, with a good deal of decision. "In the first place, there's no other man in the world who would've been able to do that job. Well, The Duster did it, and the whole town is sure that he did, and the whole town loves him for doing it! Isn't that clear? He made a fool of me, that night, but I don't carry a grudge on that account. Only—I'd like to talk things over with him."

"He'd like to, I'm sure," said I, lying pretty easy.

Because I knew that no matter how often The Duster had fooled Renney, still, he was pretty much afraid of the brains of that man. I couldn't see why, when he'd showed the upper hand so often.

Just as we were talking, along comes a couple of riders flickering down the road past the tree trunks and stop in front of the house. We can hear their voices, and the first is that of the minister's daughter, Marguerite Lamont, saying something to "Duster, dear!" and The Duster answers. We hear them laugh like a song together, and I look at the sheriff and see him wearing a frown that is half painful and half mere thought.

Then The Duster comes toward us, and the girl gallops away. The Duster comes toward us, singing, and this was the song that he sang. It comes up into my memory like a sound up a well shaft, hollow and sweet:

"Oh, my name was William Kid,

As I sailed, as I sailed;

My name was William Kid

As I sailed.

And I murdered Mister Moore,

For I hit him from before,

And I left him in his gore

As I sailed."

It wasn't the sort of a song that sounds cheerful; particularly when a fellow like The Duster is doing the singing. How many did he leave in their gore? Well, I never heard from him, and what others say you never can believe. Gossip always talks in headlines and capital letters.

When he saw the sheriff, he reined his horse straight over and dismounted and shook hands. He was such a fine actor that you would have thought that he was meeting one of his best friends. I mean, he was cordial, and grave, and considerate. Renney went to the mark like a bullet.

He said: "Duster, what's it all about? Come clean with me and tell me what you aim at here in Christmas?"

"Why, Renney," says The Duster, opening his eyes very innocent, "I want a quiet home after a hard and troubled life. That's all that I want."

Sometimes I thought that he overdid his acting; but perhaps that was because I'd lived so close to him and began to know him so well. Renney narrowed his eyes.

"That's what I want to be sure of," said he.

"Or?" says The Duster, raising his eyebrows a little.

He was mocking Renney, demanding what he could do, as you might say, flaunting his safety under the nose of the sheriff, but Renney didn't lose his temper.

"Not to you, Duster, at present," says lie. "But I'm wondering about others. Straight men make others straight. If you're really settling down here, then perhaps the boy was sent off to go straight, also. Tommy Lamont, I mean."

"I don't know anything about him," says The Duster.

"You don't know where he is?"

"No, of course not. Poor Tommy! Since he broke jail I've not heard from him."

Renney smiled a little.

"I can tell you, then," said he. "He's up in Canada in a logging camp, in British Columbia!"

THAT was a stroke. It hit The Duster between wind and water, and such a look as he gave the sheriff I hope I'll never receive. You could see the cold, hard consideration in his eyes, as he asked himself whether it would not pay to draw a gun on Renney. He decided not in the next instant, but he was so hard hit that his color had changed, and his nostrils quivered.

I never had been quite sure of The Duster's attitude toward Tommy Lamont. At first I thought he simply used the youngster as a leverage to work on the minister; and after that, as a hold on the affection of Marguerite Lamont. But this day it showed in his face that he loved the boy.

Even that calm, steady voice of his, always under such good control, now went out of hand and shook as he said: "You're going to extradite him and bring him down here, Renney?"

The sheriff made a long pause.

"It's my duty to do that," he said. "I owe that to the law."

"'Baldy,'" said The Duster to me, "will you fix me up a cup of coffee?"

I was gathering my heels under me with a groan, when Renney interrupted with: "You might as well let him stay with us, Duster. You can't buy me off with cash."

That was another stroke. I felt that for the first time in my life I was watching The Duster play a losing game, and I got excited and curious. My respect for Renney went up a thousand per cent, at least. I remembered what The Duster himself once had said that a crook always has a big advantage over an honest man, because the crook is always dealing from the bottom of the deck. Yet here was Renney taking tricks!

The Duster made a little gesture with both hands.

"What can I do, Renney?" he asked.

"Be good," said the sheriff.

I thought it was a joke, and got ready to smile. Then I saw that I was wrong and that Renney meant what he said. Be good!

"What has that to do with Tom Lamont?" snapped The Duster.

"This. I've had my eye at long distance on Tom ever since he reached that lumber camp, and it appears that he's trying to do what's right. Which makes me think that you gave him some right advice when you took him out of the jail and sent him away. But I'm not sure. I'm watching both ends of the line—Tommy up there, and you down here. A wrong step from you, and I get you if I can—but most certainly I get Tommy!"

The Duster took out a handkerchief and wiped his forehead. He was thinking as hard as he was able, I knew, and fighting something out inside himself.

"You've made yourself a factor in this town," went on the sheriff. "The boys think you're the greatest man in the world. The tramps and dead-beat prospectors, and broken-down punchers, they love you because you've ladled out money to them and shown them through a good many tough spots in their going. And even the old-time respectable citizens are now willing to say that probably John P. Thurlow is no longer The Duster, but an honest man trying to go straight. It may have been the bright example of The Duster that sent Tommy Lamont wrong; but it's also fair to say that The Duster seems to have brought Tom back onto the right trail. Now, Duster, I've come to you and I'm asking you for surety."

"What?"

"Surety that you'll stay straight from now on."

"And then?"

"Then I forget the past. My duty is to arrest poor young Lamont. But I don't want to. I ride in the name of the law, but I want my work to count among good men. I'd rather keep one man straight than arrest a thousand crooks. I want to see Tommy Lamont go right. But a thousand times rather than that, I'd see The Duster really turn into John P. Thurlow, honest citizen of the town of Christmas."

Now, take it by and large, that was the most surprising speech that I ever heard from any man. It suddenly popped my eyes open. We can't help looking on the police as our enemies; but suddenly it occurred to me that really they're our best friends. But they harden up their hands and their words for crooks, and that's the side of them we see. It dawned on me that the sheriff not only was honest, and brave, and smart, but that he had a heart of gold. He was the enemy of no man except the thugs.

"You want surety," said The Duster. "Well, I'm here living peaceably in Christmas."

"You may drop over the hill any day and bust a bank to smithereens."

The Duster took thought.

"What sort of security do you want? he asked.

"The security that most men give, for they take root like a tree and bind themselves to society."

"That sounds rather educated and difficult to me," said The Duster, with a trace of a sneer.

"You understand me perfectly," said the sheriff, without any anger in the face of that mockery.

"You mean, Renney, that I should settle down and raise a family—give my bond to society in that way?"

"You hit the nail on the head."

"Lead up the girl, then," says The Duster. "I'm to step out and ask the first comer if she'll take a chance with an ex-crook?"

"You know I don't mean that," replied Renney. "And the strongest reason that brought me here to-day was a girl. I mean Marguerite Lamont, Duster."

Well, it would have done you good, knowing what The Duster was, to see how the sheriff paralyzed him time after time, in this way. If he had been upset by the mention of Tommy, he was simply staggered by this talk of Tom's sister. He looked fighting hot again, snapping out: "What of her, Renney?"

"I'm not insulting you," said Renney gently. "But the whole town except her father has seen what I've seen. Her eyes are always on you when you're around, and she gives away her hand every second; as every good woman does, I think, and thank Heaven for it! Only, Duster—suppose she gives her hand away to the wrong man?"

The Duster glared at the sheriff, then at me, as if he would have struck us both. Then he started up and walked back and forth with long, quick strides, and his horse started to follow him, making a lot of clumsy evolutions to keep up with his master.

There was a good deal of meaning to that—the horse and the man—the pricked ears of the beast, and the dark, working face of The Duster. People and animals both had reason to fear him, and yet they loved him, too.

Renney said not a word. He reached over and made a little stack of pine needles, like a child building a house. He was building a house, for that matter, and I certainly admired his craft.

"I suppose you haven't talked about this in other places, Renney?" said The Duster at last, coming to a halt in front of the sheriff, and still looking as though he would love a fight with almost anything.

"Of course not," says the sheriff. "It's your business, Duster, and not mine at all. I'm only asking you. And, in the first place, do you know a woman you like better?"

"Better than that child?" said The Duster, throwing up his head.

"Aye, better than Marguerite Lamont."

"Renney, do you hear me?" said The Duster. "Suppose a marriage to her would seem to you a proper giving of hostages to society. But what of her? What hostages can I give her? What surety?

"Your word, man, which you've never broken, so far as I know."

That was a good touch. It surprised me. But when I came to think of it, I couldn't remember that The Duster ever had been accused of making his way by lies.

He gripped his hands and stared desperately at Renney.

"Man, man," said he, "you know what I've been. I've come when I chose, and left when I chose. I've had what I wanted and when I wanted it. I've picked out a road and never asked where it led. I've ridden by day; but I've ridden by night also. I've worked when there was spice in the job. I've lazed when I felt like it. And the thing's in my blood. How can I give it up?"

"You've been hunted like a fox," answered Renney. "You've slept in snow—like that trip you made west from Alberta—and you've ridden rods in February—as when you jumped from Detroit straight through to Butte. You've starved for a month at a time, as you did in the Pecos country three years ago. You've gone in rags, or hardly clothed—the way you got out of Phoenix not so long back. You've had your money by the hundreds of thousands, but you've lost it, squandered it, fooled it away, used it to bribe or buy weak 'good' men, lavished it on fine horses, dropped it at races, spilled it out like water for a few bright days in New Orleans, or New York, or Denver. You've learned to be startled by your own shadow; to jump up wide awake when the wind whispers at night; to never sit except with your back to the wall; to keep away from windows and doors; and always to have your right hand empty, and ready to grab the butt of a gun! Do you call that a happy life?"

The Duster reflected.

"Aye," said he, then, "better than eight hours a day; carpet slippers and a newspaper at night; a baby squalling at dawn; and the first of the month like a gun at your head."

How would the sheriff answer that, I wondered? He had the answer pat.

"She would make up the difference, and more," said he.

I saw The Duster fumble at his throat like a schoolboy puzzled by a hard question.

"I can take the chance when I'm gambling only with myself; but how could I gamble on her happiness? Suppose I made some wrong step; or that she had a look into the story I've lived; or that I stopped lying and drawing the curtain over what I've been? It would break her heart!"

"You talk," said Renney, "like a child. There's only one real wrong that you could do to such a woman, and that would be to stop loving her."

He stood up as he said it, and The Duster went and caught him by the shoulders.

"Renney," said he, "could I do it?"

Imagine The Duster, if you can, saying such a thing?

"I can't answer you," says Renney, with a twisted grin. "You'll have to ask Marguerite."

The Duster did not speak again. But he got to the back of his horse and into the saddle with one prodigious leap, and was gone away through the trees like a frightened wild cat.

I waited until the dust of his going had settled down, and the last dead leaf had fluttered back to a place on earth. And still I stared after him, seeing in my mind the way that bay must be turning the curves under the spur, and the look of The Duster as he leaned over the pommel and jockeyed an extra bit of speed out of the gelding.

"Kind of dry, that tinder," I said to Renney at last.

He was looking the same way with me, but none too happy, I should've said.

"Aye," said he, "and he'll burn without any smoke, I hope, and last a long time."

"He will," I declared, though I wasn't at all sure. "Tell me, sheriff," said I, "how you come to know so much about women?

"I don't," says he.

"You certainly seem to have Marguerite Lamont by heart," I argued. "I never heard any woman talked out better."

"Well," said Renney, with a sigh, "there's some of them that carry their title on their forehead. And besides, she used to smile at me once in a while, before The Duster came up like the sun and turned the other men black for her."

"UNTO thine own self be true!" says some one.

A friend of mine says that is Shakespeare, though it sounds pretty Bible to me; but you never can tell the two apart. One sounds like a pulpit set up in the mountains, and the other sounds like the mountains brought into the pulpit.

Which I mean to say that whatever The Duster was, he was true to himself in the pinches, and that's about all that a man can ask of another, I suppose. For my part, I'd only ask a man to be honest about once a week, but when The Duster came charging up to the house of the minister like a tiger out of the jungle, we know what he did and said, because there was another man present.

Who? Why, the same man he had cheated, scoffed at, beaten, and then upheld in his church as if for the sake of sport. The girl's own father—the minister himself! Why did The Duster do that? For lack of shame? Or to show his own power over men and women? Well, I don't know, but my job is simply to set down the facts.

Beside the minister's shack, he pulled up the gelding on his two hind legs and hit the ground before two more were down. He went up to the front door and gave it a whang, and the voice of the minister bawled out and asked him in.

When he went in, there sat Lamont behind a deal table that served him as a desk. He was in shirt sleeves, his hair tousled up by his shoving his big hands into it as he thought, and a scowl on his face as he drafted out next Sunday's sermon with an indelible pencil on cheap, rough paper. Which was as much as to say that he hoped his ideas would be immortal, but had his doubts. He had wetted the lead of his pencil from time to time while he worked, and the result was a round purple patch in the center of his mouth.

"What d'you want?" says Lamont, and then sees that it's The Duster himself, which must have made him come as close to trembling as a Scotchman can.

"I want to talk to you," says The Duster.

"Do you need a crutch for that?" says Lamont. "Or will that chair help you out enough?"

The Duster did not take the chair.

Instead, he stood behind it, with his hand resting on the top rung, and his hat in his hand, acting humble. But he never could really be humble. There was too much proud fire coldly lying in his eyes, all the time.

"I have come to tell you a story," says The Duster.

He gives a bow toward the kitchen door, where Marguerite shows herself, slim and white against the dimness of the rear room of the house. She had her sleeves tucked up over her round arms, and an apron tied around her, and in her hand there was a dish towel with which she was polishing up a glass. I imagine her standing there and glowing at The Duster like a star in the dusk of the day.

"And I should like to have your daughter hear it, also," says The Duster.

Lamont turned around in his chair so that it squawked like a puppy that has been stepped on.

"What have you to do with this?" says the minister, glowering at her.

"I don't know, daddy," says she, mild and meek as usual.

"Come in, then, and we'll soon find out," says the minister, and in she comes, too fascinated and shocked and delighted with the presence of The Duster to even remember to put down the towel and the glass, but from time to time giving it a rub; looking down at its brightness, or hesitantly up at The Duster as though his face were a dazzling light, or sadly and sweetly out the window where she saw not the green hills and the cows that grazed there, or the blue, deep sky beyond, but something else about which you and I know nothing at all.

"Now?" says Lamont, looking grimly back at The Duster.

He answered: "I wanted to tell you a story, sir."

"About what?" said Lamont.

"About a sheep, sir."

"If you have to put in the sheep, leave out the 'sir,'" said Lamont. "Now, what is it?"

"Once upon a time," said The Duster, "there was a sheep born with teeth like a wolf."

"Go on," said the minister. "I like the beginning of that story because it sounds like a confession."

"The truth always does," said The Duster, "because it comes as rarely as Sunday."

"Stuff!" said Lamont. "Go on with your yarn."

He gave his daughter a hard look, but got no more out of her than if he had looked at the zenith of the sky.

"This sheep," said The Duster, "one day got through a hole in a hedge, meaning no harm, and began to eat the neighbor's grass; and when the neighbor saw it, he sent out his dogs and they gave it a terrible run, but when it could run no longer, it turned around and fought, not with its head and its feet, but with its teeth. It killed a couple of the dogs and hurt two more of them so that they went howling home.

"After that, the sheep was so frightened by what it had done, and so delighted to be free, that it scampered on back to its home flock.

"But when it came through the hole in the hedge the other sheep smelled blood. At once they set up the cry of 'Wolf! Wolf!' and the rams ranged themselves on the outside of the flock, and the wethers behind them, and the little lambs inside them, and the bell-goat in the center of all, and they kept on shouting, 'Wolf! Wolf!' until the farmer came out with a gun and saw the red on the white thing by the hedge, and fired at it, and sent a slug through its body, and another slug through its face."

As he said this, The Duster paused in the making of a cigarette and absently touched his cheek, where there was a little white scar.

Then he went on:

"The poor sheep that was born with teeth—which was not his fault at all!—ran away as fast as he could, and would have been found and killed by the dogs of his own master, if it hadn't been for the coming of the evening. When he got off in the woods, he licked his wounds and wondered at the strangeness of the world, and stayed there, starving and wondering, until his wound was well.

"When he came out of the wood again, he found out that the simplest way to live was on the bodies of his fellows—that is to say, the other sheep whom he found, here and there, most of whom didn't have teeth, but a great many of them with very long wool. He collected enough fleece to keep him warm and sold the rest for food, and lived very well, and would have been extremely happy if he could have forgotten the warmth of the old nights when he slept in the fold with all the other sheep breathing and blinking around him. You understand how it is?"

"I don't understand a thing you're saying," said the minister, who was such a clever man that he didn't mind being stupid now and then.

The Duster turned slightly toward Marguerite and made a little bow, which was one of his ways.

"Do you understand me, Marguerite?" says he.

This sudden and grave appeal made her lift her hands—the glass and the dish towel with them—up to her breast.

"Yes," said she. "I mean to say, I think that I understand you perfectly, John."

"Is that his name?" roared the minister, suddenly frightened and therefore, speaking very loudly.

She shrank back into her chair.

"Duster, I mean," said she, whispering.

The minister made a face, but he kept the words from coming out and sat up in his chair, scowling first at The Duster and then at his daughter. He changed color, too, and he had mighty good reason for that.

"Go on about this eternal sheep!" he commanded.

"Certainly, sir," said The Duster, appearing to like his humble role on this occasion. "The poor outcast sheep went—"

"The one with teeth, you mean?" asked the minister.

"Yes, sir."

"Drop the 'sirring' and get on!"

"The poor outcast sheep, sir," said The Duster gently, "went up and down the face of this earth, not sadly, but kicking up his heels and even bleating a little now and then, but still, as I was saying, remembering from time to time the sheepfold, like a safe little village, and the farmer's dogs, like the strength of the law, and the farmer himself like a powerful judge. Do you follow me, sir?"

The minister growled, but said nothing. He was too busy watching Marguerite, who was sitting on the edge of her chair with the glass pressed against her breast like a diamond beyond price, and her eyes staring wildly at The Duster—and something more.

"This sheep," said The Duster, "that went wildly wandering up and down through the hills, taking what he wanted, going where he wished, laughing at the law, and at the little churches, and the men that pray there, and all such things—this same fellow, one day came back and looked over the rail of a fold—or a village, as you might say, wondering how many fleeces he could pick up there in his regular occupation."

"I suppose you mean that he was a robber?" said the minister harshly.

"That was his occupation," said The Duster very mildly, "and as the poet says, there's no harm in a man following his occupation, sir."

"What poet says that?" bellowed Lamont, getting red in the face.

"Shakespeare, sir," said The Duster.

Lamont was silenced. For even a minister will accept quotations out of Shakespeare, it appears, though I never could learn why.

"To go back to the poor lost sheep that looked into the village," went on The Duster, "he was used to seeing all sorts of people. There were men he had robbed in banks, and there were men he had robbed on trains; and there were men he had robbed at the card table, and men he had robbed on the highway. He was used to reading the minds of men through their faces. Except for ministers, whom he always found extremely difficult, sir."

"Confound you, you rascal!" said Lamont, and then coughed and glared at his daughter to warn her that she was looking like a frightened and enchanted goose.

But Marguerite did not heed him. She would not have heeded fire from Heaven, if it had suddenly poured down between her and the face of The Duster.

"Get to the point!" said Lamont abruptly.

"I shall, sir," said The Duster, "at once."

"YOU were looking over a fence into a village wondering whom you could rob, in the last sentence, if you want to find your place," said Lamont.

"The sheep was," said The Duster.

"The sheep? Bah!" muttered the minister.

"That was about what the sheep said," replied The Duster. "I don't want to conceal that he had grown rather hardened in spirit from walking the hills by day and night."

"Chiefly at night, I suspect?" sneered the minister.

"Exactly, sir, so that he was familiar with the stars," said The Duster. "And when he looked down into the crowd of the people in Christmas, he saw a great many good men and women, and some not so good; but most of them were concealed or dimmed by a mist that rises up from human faults and sins and sorrows, except on Sunday mornings, when, of course, you brush them all away with your good sermons, sir."

You see that The Duster had brought the scene around to twelve o'clock, as you might say, and struck a gong with his last words that echoed into the minister's heart, and certainly into the heart of Marguerite.

"Your sheep—your stars—your mists—I wish you'd get down to the facts of your case," said the minister.

"I hoped," said The Duster, more gently than ever, "that you would have some sympathy for this poor sheep."

"We'll tell in the conclusion," said the minister.

"That sounds more legal than Christian," said The Duster. "However, I want you to know that the sheep had been out in the weather so long, and was so long unwashed by such things as good Sunday sermons, that he had weathered very dark. In fact, you might have called him a black sheep. But this black sheep, when he looked over the fence into the village at the people inside, and saw their faces, dim with sin and complacency, and wind, and 'good works,' and talk, and scandal, and gossip, and backbiting, and treachery, and envy, and hatred and petty cheating, and lies, and all the other things that go to make up the dust in a village street—among all these, so bright that it was like the stars he was so accustomed to see shining over the midnight hills, he saw one face always before him—"

He made a slight pause, and looked straight at Marguerite, and as he did so, the glass tumbled from her hand. She made a vague gesture to recapture it, but it crashed on the floor into a million pieces, and she sat there holding the dish towel against her breast like a cross, say, or a child.

The minister leaned in his chair and looked at his girl with despair and fear, but she did not regard him a whit. Her lips had parted. He could see her breathe, and with every breath the light waxed and waned in her eyes.

The Duster was looking straight at her, now, and for once in his life I suppose he was not acting, as he went on in such a voice as no man and no woman ever had heard from him before:

"She was so gentle, so good, so beautiful, that my heart stopped like the hands of a watch which will always point to a Sunday morning, and the church on Christmas Hill, and Marguerite."

The minister came to his feet with a lurch, like a steer that has worked free from the mud at the edge of a tank.

"What do you mean, Duster?" he cried. "What are you saying here?"

"I am simply telling you a story of a black sheep, who fell in love," said The Duster.

Her own name seemed to have frozen up speech in the girl, but at this, she uttered a little cry, and the poor dish towel fell from her, and she sat with her empty hands turned up, looking partly like a child and partly like a saint, which is exactly what she was.

"Do you love my girl?" said the minister.

"I do, sir," said The Duster.

The minister turned toward Marguerite, but when he looked at her, there was no need whatsoever of asking a question.

And all the labor, the disappointments, the pain, the loss of his good wife, the disgrace and disappearance of Tommy, his son, were probably less to him than the shock of seeing in the face of Marguerite that she did truly love this man. He was no fool, and if he knew anything in the world it was that his daughter would never love twice. She was the sort of a sword, you might say, that can cut through a mountain of steel, but it is only good for one stroke.

So Lamont stood there for a moment, swaying, gripping his big labor-roughened hands, and breathing harshly, like a man who has been running uphill.

All he could say for a moment was: "You've spoken in front of me. I want to remember that. You've spoken in front of me."

Now he rubbed his knuckles across his forehead.

"Marguerite?" he said at last.

Of course she heard the pain and the loss and the misery in his voice, and the fear which he felt for her sake, and the cherishing which he had given to her, like a father and like a mother, too. But, after all, there is one time in her life when the best of women is strong enough to be cruel, and this moment had come to her. All she felt for her father made her voice low, but it was audible as the breath of life or the beating of a heart.

"Ah, daddy," said she, "may I have him?"

Those words I have turned in my mind a great many times, and I would not change them. It was like a child asking for a toy.

The minister, like a man fatally hurt but still marching in the ranks, went straight on to do the duty that lay in front of him.

"I have no right to give you or to keep you, dear," said he. "You love The Duster—"

He had to pause, there, and fight with himself for a minute. For I suppose the very name "Duster" brought up into his mind his own struggle against this man, his defeat, the disgrace of that burial of a heathen outlaw in the sacred ground of his cemetery, and all the killings and lesser crimes which were counted into the record of John Thurlow.

However, he was able to go on again presently, and say: "And all that I can do is to try to see that your future will be fairly safe in the hands of your husband. I think that I should try to do that, Marguerite."

Even if she had been able to find breath for an answer, I suppose she would not have had any words. So she slipped from her chair for the first time, and going to Lamont, she stood beside him, looking up into his face with trembling lips and never daring to venture a second glance toward The Duster.

Lamont put his arm around her and pressed her closely to him, as though he were saying farewell to her forever. And, in a sense, I suppose he really was.

He started to say: "Duster," but caught himself, and instead began: "John, I have to ask a guarantee from you?

"Yes," said The Duster.

"You can give it or not," said Lamont. "Certainly, I haven't any right or power to demand it from you. But I think we all three must try to forget that black sheep which had been wandering on the hills, as you were saying a little while ago. We ought to forget him and consider that this fellow who walked into Christmas town is a new man. He has no past. His name is John P. Thurlow. He does not talk about the things that he has been; but he tells me that he will not spend on my daughter a single penny that he has—won—before to-day. And in the future, he will keep his hands clean. No stolen money out of the past, Duster," he broke out with a great voice. "For both your sakes, dress her cleanly, even if it has to be in rags!"

The Duster made a start and drew himself up. He raised his hand and his face, but Lamont rudely knocked them down.

"Don't swear!" said he.

The Duster gasped—even The Duster!

"Don't swear!" said the minister. And he added his one really bitter speech that day: "You'll have to prove yourself worthy by time, before your oaths are worth considering. But give me your hand on it, as one gentleman to another."

You could abash a mountain sheep on a high rock almost as soon as The Duster, but he was abashed now. All he could do was to silently take the hand of Lamont.

And that poor man took his daughter in his arms, and kissed her two or three times, saying over her in a muttering voice: "My darling, my darling! Oh, my darling!"

Then he gave her to The Duster with his own hands.

WHEN The Duster came home, it was late in the day. The sun had gone down, coolness had fallen on us out of the sky, the stars began to step out thin and small in the east, and a good fresh wind came and blew the smoke and steam of the cookery out of my face.

I was making a Mulligan stew. That may make you think of gristle, lean shoulder meat, and a few rib bones with strips of fat sticking to them, a scattering of stale vegetables with the life cooked out of them, and all the moldy old bread in the bread can dropped in to give the thing substance. But T mean real Mulligan, than which there's nothing better. I mean a good young chicken that's fat to the ridge of the back and larded with fat; a chunk of pork with the salt soaked and then parboiled out of it; and these I two cooked together, while you cook quickly in separate pans, your carrots, and tinned beans, and tomatoes, and a smell of garlic, say, to make the taste all stick together.

Now. I had just put all the vegetables into the main pot, telling myself that if The Duster came home late he could have cold stew and go hang, because I was ready to eat just then; but as I was lifting the pot off the fire to the back of the stove, T heard the hammering hoofs of his horse rush in under the trees and slide to a stop in front of the house.

"Good news," says I to myself, "good news—for The Duster!"

For thinking of the pretty, kind face of the girl suddenly wiped the smile off my face.

He came striding in, throwing his hat into one corner and his quirt into another, and looking, as usual, three inches and thirty pounds bigger than the truth about him, which I once had carried senseless in my arms across that same room and laid on the bunk.

"It's done, Baldy," says he.

"It is," says I, "and it's chicken Mulligan, and a lot too good for the likes of you. Smell it?"

He sniffed. Mostly he always did what I told him to about little things that didn't count.

"It's done," says he again.

I looked at him. His face was shining like the face of a boy on Christmas morning.

"Aye, and not overdone," said I, "which is lucky for you that you came home just now. Pull up a couple of chairs to the table and cut a coupla slices of bread from that loaf. Homemade, mind you! I baked it this morning at three hundred in the shade. Which I ain't training for high temperatures, either, like you ought to."

The Duster slashed off a couple of slices from the loaf, absent-mindedly. But instead of sitting, he began to perambulate up and down the room.

He picked up the quirt and hung it on a nail. He took it down again and slashed the air.

"How fast are you going, Duster?" says I. "I hope you get there in time for supper. Did you hear me say that this is chicken Mulligan?"

"Baldy," he says for the third time, "it's done, I tell you!"

"Aye," says I, "and that's what I'm trying to get off my mind, and put the Mulligan on. Sit down."

Still he didn't sit down.

He came and leaned over, his hands gripping the back of the chair opposite me, low down, so that his eyes were not high above mine.

"Do you think that it won't pan out, Baldy?" he asked me.

I stopped eating, although the Mulligan was prime. The Duster, the great Duster, was talking to me like any young fool in love. He was asking my advice!

"Hey?" says I, fighting for time.

"Do you think it won't go?" said he.

"By the soft eyes of her," says I, "I knew it was a marriage the first time she seen you."

He frowned a little, but his mind slid over my mean remark and went back to his subject.

"You think that we have a chance, Baldy? You sent me to her, you remember?

"The sheriff done that," said I. "Because he figured you had to get punished outside of jail."

"You don't really mean what you say," said The Duster, with a sigh. "I wish you'd talk seriously to me, Baldy. You think we have a chance for happiness together?"

"Sure," said I. "Part of the time you'll have a fine time together, the pair of you."

"Part of the time?" says he. "Which part?

"The part when you're out of prison," said I.

He tried to laugh, but only squawked.

"Sit down," said I. "Before the grease gets up to the top of the stew."

He poured out a cup of coffee, burned himself with it, and went on pacing the room without swearing, merely licking his blistered lips.

"I love her," says The Duster, like a man running under double wraps, and speaking softly. "I love her!"

"I love the Mulligan," says I, "and thank my stars I didn't forget to put in the garlic! Sit down, Duster, and don't act like a crazy man!"

"Ah, Baldy," says he, "what a grand thing it is for a girl or a boy to have a father—a good man—a brave, simple, strong, good man like Lamont!"

"Him that you made such a fool of?" I reminded him.

"Heaven forgive me!" says The Duster, just like that.

I got pretty nearly scared when I heard him, it was so' unlike his old self.

"Are you gunna cry about it?" says I.

"I love her," says The Duster, as though it was something new for me to hear.

"I'd as soon you wrote me a letter," says I. "I'm not going to marry her."

"Gentle, sweet, and pure!" says The Duster.

"Pass me the coffeepot," says I, "and mind you don't let the lid fall off. I've been figuring on mending it, if you'd ever remember to get me a soldering stick, when you're downtown."

"My sweet girl!" said he. "Heaven help me to take care of her; and keep me straight—and keep me straight!"

"I heard you before," said I, "but it's not my ground that you're sinking the rise in. How did Lamont take this punch."

"Like a man," said The Duster. "Like a good man and a true father."

"He's a glutton for punishment," said I. "He's an iron man, and if he could give the way he takes, he'd been the champion of the world. While you're up, will you put a stick of wood in the stove? I forgot the fire for the dishwater."

Of course he paid no attention to me. He didn't even get angry, which I would have liked; but, at any rate, I'd stopped him talking if I couldn't stop him pacing, and I went moodily on with supper, forgetting the good taste of the Mulligan, even, and eating more than I wanted of it, at that, and nearly breaking my teeth on the edge of the coffee cup. I was worried for that poor Margie!

At last he cut in again with: "I'll be able to do it. I'll get work. I'll stick to it. I'll never go back!"

That made me mad. He was praying out loud, as you might say.

"Sure," said I, "you'd be all right if things were a little changed."

He came hurrying over once more and planted himself where he could watch my eyes when I answered.

"Changed in what way? he asked.

"If all the week was made up of Mondays, I mean," said I.

"You think that I'll weaken, and quit work, and slide back to the easy ways of making money," said he. "But you're wrong, Baldy. You know me only in part. I don't know myself. This day something is added to me!"

"Sure," said I. "You'll soon have a new cook that'll work without wages, but you'll still have to buy the Mulligan for two. Have you got the makings?"

He gave them to me with a sigh, still looking hard ahead into his future.

I built myself a cigarette, and though I felt pretty hard, I managed to keep from tearing the paper.

"Have you told her about the three hundred thousand that you start on for capital, and the field where it grew, and the color of the flowers when it bloomed?" I asked him.

"It's gone," said he. "I'll give it all away. Not to that cur of a Muncie, perhaps. But to some worthy charity and—"

His voice trailed away, as though he were trying to find the right spot to drop that lump of money. Of course I had forgotten my lighted match, by this time, and it burned the tips of my fingers before I was able to drop it and say: "Give it away—Worthy char— "Listen to me, Duster! Do I look worthy to you?"

He smiled down at me in a sort of quiet, fond way.

"Ah, Baldy," said he, "as if you'd take the stuff—the stolen stuff, I mean. Old man, I'd trade everything I have for the sake of your honesty! Then I'd know that our home was founded on rock."

"If you were like me," said I, "your home wouldn't be much more than a rock, for sure. And if—"

Now, as I said this, I saw The Duster straighten with a twitch-back of his shoulders, and I knew that he was looking at some one who had silently entered the room.

I turned my head and there I saw a thing I wish never had dawned upon my eyes.

He had stepped lightly in, and instantly to the side, so that he would have solid wall behind him, and not space through which gun muzzles could be poked into his spinal column. His face was the same as I remembered it—muddy white, like the belly of a catfish. A face that did you no good to see.

And when I saw him now, I let out a sort of a choked screech that hurt my throat, for I was looking at the ashes that The Duster had buried so carefully up there on Christmas Hill. I mean, I was looking at the man whose ashes those were supposed to be, for there in the room with us, casting his shadow on the wall, was Hector Manness!

"CHOKE that old fool," said Manness, "before he wakes up the entire town, crowing as if the day were here!"

"No," said The Duster, "as a matter of fact, the night seems a little darker than usual."

Manness merely smiled, and replied: "There's the same old light touch! I'm glad to see that you haven't lost it, Duster. Cuts a man's throat so that he hardly knows he's lost his life until he tries to draw the next breath. Shall I sit down?"

"Not in here," said The Duster. "If you sit down in here, think how much you'd be in the lamplight, Hector? The limelight, as one might say. And so many people anxious to see you—dead or alive!"

Once more Manness smiled, and I never saw a smile that failed to improve any face as completely as that failed with Manness. I had heard so much about this man and had even seen him before, that I couldn't help knowing about his loathsome career in the past; but I didn't have to know about it. I could see it all printed in the brain and the flesh of that sick-looking scoundrel. He was a little frightened, now, by what The Duster had said. And he didn't make any effort to cover up his fear, but let it glisten in his eyes and jerk at his lips. Still, he was also pleased; as though by having been called the "chief" monster.

"They don't love me, Duster," said he, "and it looks as though your friend, there, didn't love me, either. That's a grief to me."

"Aye," says The Duster. "When they catch you, they won't acquit you. They'll take your nine lives all at once. They'd take ninety, if you had 'em!"

"Are you proud," said Manness, "because the fools have let you off five times when they should have hanged you? Or are you trying to frighten me? And to wind up with, are we going to keep on talking in the presence of that superannuated eavesdropper there?"

Now, a man can take so much, but no more, and though I had no more chance with that magical hand of Manness than I did with The Duster, still, I felt that I had to take a stand here and now. So I said to him: "Manness, you've spoken of me twice as though I were a dog. The next time, I'll have my teeth in you."

Manness looked me up and down.

"Do you know who you're talking to, Wye?" said he.

"I know fairly well," said I. "I don't know all about you, but I know some samples of the sneaking murders, and stabbings in the back, and throats cut at night, and such like things that you've done. They ought to hunt you with a snake charmer!"

Somewhere it had been floating around in my mind that Manness had one vulnerable spot, and that he went almost crazy when he was insulted by being compared to a snake. I think there was a story of a fellow in Butte who had made that mistake, and the yarn went on that, in revenge, this Manness had actually got hold of him and dumped him into a snake cave, and then stood by while the poor wretch came lurching out, squirted full of venom from fifty bites, and watched him yell and twist and die there in the Montana sun. That's pretty horrible, but I've heard it vouched for by honest men; and certainly when you looked at Manness, and his sinuous leanness, and his unearthly, bright, unwinking little eyes, you could see why he'd resent the comparison. When he heard me speak now, he fairly turned blue around the lips, and his right hand flicked inside his coat so fast that I couldn't have brought my gun out of the holster in time to stop him.

The Duster could, however, and with a flash of his hand, he covered Manness there by the door.

"I'll let a streak of light clean through you, Manness," said he, "if you shove a gun at Wye!"

Manness kept his hand inside his coat for an instant, while he rolled his look from me toward my protector. I thought that he would take a chance with both of us, but that idea couldn't have lasted a tenth of a second with him.

He brought out his hand with—a sack of tobacco and a package of brown papers between the tips of the slim fingers.

"You talk like a fool, Duster," said he. "You never had any real sense of humor. I wanted to see what sort of nerve your crook had—and I see that he hasn't got much!"

I might as well be frank. I was scared into the shakes, true enough, but The Duster was kind enough not to look at me.

"You'd give anybody the horrors," said he. "Nobody feels at home with a Gila monster."

It made my hair rise to hear that. For two reasons. The Duster had put his gun away, so that he stood on even terms with Manness at that moment, and this meant that a fight was as likely as not. It meant, furthermore, that The Duster was inviting trouble, and whatever else men said about Manness, no one ever had doubted his courage, any more than they doubt that of a lion.

But whether it was policy or fear of his master, he did not choose to accept the challenge at this moment but merely smiled—which was no more than a flash of white teeth.

"You've never grown out of your school days," says Manness. "Forever drawing a line and putting a chip on your shoulder. Stop being a child, because I want to talk with you."

"Fire away," says The Duster coldly.

"Alone," said Manness.

"But there's the point. I don't know that I care to talk to you alone."

"Are you afraid to?" says Manness, leering at him.

"I'm busy," said The Duster.

"Thinking of Marguerite, I suppose?"

I thought The Duster would strike a slug into him at that. He hung on the trembling verge of it, at least, but then controlled himself with a big effort. I wonder how Manness could have learned of that affair so soon? For he seemed to know everything.

"As a matter of fact," said Manness, "that's what brought me here. I wanted to make that marriage more possible for you, Duster, if you'll believe me."

"I believe that you never wanted to do anything to any man's advantage," declared The Duster. "I'm not going to talk to you, Manness. You've broken a promise in coming back here."

"Ah, yes," says Manness. "But you know that man only proposes, Duster. The luck was horribly against me. However, I'll prove that you ought to send that gray-headed old man out of the place while we have a chat. I want to suggest that before you can safely marry her you'll have to remove a few obstacles. You'll surely see that."

"Obstacles?" said The Duster, lifting his eyebrows.

"The worst kind."

"Such as what?"

"Why, obstacles that may come up in her own mind, d'you see?"

"I don't know what you mean, Manness."

"You'd better, though."

"You're lying, as usual," said The Duster in final decision. "You know nothing about the affair at all."

"Don't I? No, you know that I'm telling you the truth."

"How could you know about her? No more than the night could know about the day, Manness."

He said it with open disgust and scorn, but Manness answered: "You have to remember that the devil has more ears than any one else. But make your choice. One way or the other. I'm offering you your chance, Duster!". He stepped a little toward the door, full of anger and hate—the only two emotions that could be natural to the beast.

I saw The Duster waver and then fall from his high ground.

"Baldy," he said to me, "let me have a minute alone with Manness, will you? You haven't watered the horses this evening, anyway."

Manness sneered at me as he won his first victory, but I said to The Duster: "Good luck, old man! Remember that if he so much as scratches you, you're finished, because he's sure to have poison on the end of his knife."

I thought that idea made some impression on The Duster; it certainly made Manness jerk as though I had hit him with a whip. But then I had to leave the room, mightily unwillingly, because the things that Manness couldn't talk about in front of me were not likely to be the things that would do The Duster any good hearing them alone.

I went out, but I didn't water the horses. I wouldn't have missed that conversation for any price.

All I did was to walk straight out in the path of the lamplight toward the barn, and then, stepping out of the light, I yanked off my boots and came back like a flash to the house and slid in under it. I mean, the old shack was raised on stilts from the ground to keep it from molding floors in the rainy season. It was boarded up with a skirting originally, but this skirting had rotted or been torn away, and the result was that there were big gaps through which I could easily work.

I got under, therefore, and lay down close beneath a big knot-hole through which the dim lamplight fell down and showed me a beetle struggling along with some sort of a burden.

After I got there, for a second. I heard Manness say that he would take a look to see whether I'd really gone, and heard footfalls cross the floor.

They stepped out onto the ground in front of the door, and I actually saw that pale wretch crouch and look under the house. He remained there for ten seconds. The only reason I didn't pull a gun and shoot him in self-defense was that I was actually too frightened to move a hand. I thought I saw him spot me and reach for a gun, but in another moment he straightened up and stepped inside the house again.

"That's the trouble with good men, Duster," said he. "No matter how honest they may be, they haven't the courage to do what they want to do. Look at this fellow, Baldy Wye. He wanted to protect you from me, by keeping near enough to listen; but he didn't love you as much as he feared me, and he's slipped off there to get rid of the trouble and wash his hands of you, while he waters the horses!"

He laughed, and I hated him, and was shamed, and then foolishly proud as a boy to realize that even old Baldy Wye had slipped one over on Hector Manness.

Just after that there was a pause, in which I heard the galloping of horses on the road, and the rattle of voices of young fellows, bawling out to one another as they went. I was afraid that noise had blotted out some of the conversation from above me, but it hadn't. And the first thing that The Duster said I heard as plainly as though I had been in the room.

He said: "I don't need the help of Baldy Wye or any other man. I can take care of myself with you; I always could, and I always can."

"On the contrary," said Manness, "you're absolutely in my hands!"

WHEN I was a boy, I remember that my mother told me there was no fool as great as the man who ever believed a proved liar, but still, as I lay there under the floor, I couldn't help believing Manness. For there was a ring and a thrill in his tone. Acting sometimes passes for the truth, but this sounded like the dropping of a pure golden coin.

"In your hands?" said The Duster. "No, no, Hector, I'm out of them for the first time in these years. I'm out of them, and I'll never come into them again."

"We'll see. We're going to talk the thing out, aren't we?"

"I suppose so, but let's be quick about it, Hector. You're as pleasant a sight to my eyes as—"

"As that Gila monster you were speaking of a minute ago?" suggested Manness briskly.

"Put it however you please. Let's be ended. I told you that the Muncie bank was the last job I'd work with you on. I meant it. The job is finished. I had your solemn word of honor that you'd never trouble me again when the work was done. And you know, Manness, that I didn't want to tackle that affair. The fact is that I was through before it started. You begged me to come in. You swore it was the last time you'd borrow my help. And like a fool I believed you!"

He stopped for an answer, and, to my surprise, Manness did not attempt to make one. He allowed The Duster to begin again, and the latter immediately continued:

"I was sick of you and your ways and your works a long time before, and I told you so. Is that true?"

"It's true, Duster," answered Manness—not submissively, but as though he had to admit the truth.

"I would have broken with you then," said The Duster, "but I didn't want to leave you in the lurch. They were cornering you. The whole country hated you like a plague. You had no friends, and no place where you could turn. You knew you were done for. Once caught, there was no chance for you. They would hang you with joy. No juryman would dare to vote in your favor for fear of being lynched after the trial was over! I had made up my mind to quit you and, therefore, I wanted to see you safe first of all. So I proposed that I should try this huge hoax that I've worked in Christmas. I'd come here and try to bury your ashes in the churchyard—the ashes of Hector Manness! That would prove that you were dead. And when luck brought us on the old Apache Trail to that thigh bone with the imbedded bullet, like your own, of course you remember that it clinched the purpose in my mind. I would come up here and prove to the world that you were dead by fighting to bury your ashes in consecrated earth. So I did it, didn't I?"

"You certainly did," said Manness, as before giving away every chance to dispute.

"And the scheme worked, didn't it?"

"It did. Every paper in the country carried articles about my demise!"

He laughed, snarlingly, as he said this.

"Yes," went on The Duster, "they carried the articles. Up to that time the police along every border, and at every shipping port, had been on the lookout for you. They were keen as hawks about you. But now they know that you're dead, and the way is open. You can get out anywhere, with hardly a chance of them finding you. People don't recognize dead men in living ones! A change of complexion would have been enough disguise for you!"

"That's still true," said Manness.

"Aye," said The Duster, "but before I did this, I made you swear that we were done as partners. Heaven knows why I ever worked with you at all—unless it was as Baldy Wye suggested just now, that I wanted to see if I could be a snake charmer!"

It was as bad an insult as you could imagine, but still that fellow Manness swallowed it without a murmur.

"And after I had done the work, you came back and begged me to help you to one last stake. You'd gambled the other stuff away. If I would help you on the Muncie haul, you'd clear out and never bother me again. Well, I agreed to that. To rob Muncie was simply stealing from a thief; that wouldn't be on my conscience hardly. So I did it. And again you swore, when we parted—I with a slash along my ribs that might some day send me to the penitentiary—that you wouldn't dare show yourself over the edge of my sky line so long as you lived. Is that correct?"

"All perfectly correct."

"Then what under the sky gives you the brassy nerve to come here to-night and trouble me again?"

"Luck!" said Manness, with an odd quietness. "Bad luck. I've been cleaned out again, Duster."

"Bah! What's that to me?"

"You were always a charitable fellow. You never turned down an old partner."

"I'll stake you to a ticket out, if that's what you mean."

"I do. A half-million-dollar ticket out."

"Explain, Hector."

"It's the simplest game I ever saw. After Muncie's safe was cracked, every last one of his depositors—and you know he had some big ones—has transferred to the First National right here in the town of Christmas."

The Duster stamped on the floor, and I saw a thin shower of dust fall down through the knot hole above my face.

"You want me to help you crack that job?" he asked. "Why, man, you know my principles! I don't mind relieving some fellow with a fat purse of some of the stuff that lines it. But the First National here has the accounts of all the little one-horse farmers; and the old broken-down cow-punchers and prospectors have loaded their last savings into it. The old-timers have planted in that bank their funeral funds. You want me to lift money like that?"

He changed his tone: "Manness, how did you lose what you got on the Muncie split?"

"The yellow crooks in the stock market!" snarled Manness. "The sly, sneaking, smooth-speaking, lying, hypocritical, back-stabbing crooks in the stock market! I had a sure thing outlined. I would have turned that three hundred thousand into three million sure—ten million in three months, if I had any breaks in the game at all. I had something surer than wire-tapping. But the yellow dogs gave me away, and the three hundred thousand slipped with that chance. Curse them! I'll have some of them for it. I'll have some of them, Duster, in a way they'll remember!"

"Snakes?" said The Duster.

I heard a gasp of rage and controlled fury from Manness.

"Will you listen to this job I have lined up?" he asked.

"Not to a word of it."

"I've got Pemberton willing to work with us and let us in on the ground floor. He asks fifty thousand flat, and that's every penny we'd have to put out!"

I remembered Pemberton's round, rosy face, and honest smile, and kind, dim gray eyes. Well, I could hardly believe that he had sold out his employers in that bank. We'd been saying for years what an asset an honest man like Pemberton was to the Christmas First National. Men used to put their accounts in that bank simply because they liked to see the good fat smile of Pemberton, fat as a walrus' cheek.

"Not if he'd sell out for five cents. It doesn't interest me, Manness, and there's an end. I'd rather rob my grandmother than such a bank as the First National here!"

"Well, Duster, you have no choice," said Manness. "I've got to have you in. And you belong to me for this last job!"

I waited.

Then The Duster said: "Tell me how I'm in your hand, Hector?"

"This way. Before I came to see you to-day, I wrote a letter to the editor of the little paper here in Christmas. I told 'em frankly—for their own good, you know—that their sheriff was a simpleton and that the whole town was fat-witted. I pointed out how you have come here, buried some random bones and wood ashes that you called my remains, got yourself the confidence of the town, and after robbing the Muncie bank with me, you've become engaged to the nicest girl in the town and intend to live on the coin you've stolen."

"You didn't mail that letter, Hector?"

"Of course not. I left it in the hands of a friend, to be mailed within three, days, unless I return. I had in mind that you might murder me, of course, if you were not feeling logical minded, this evening."

"Interesting idea," says The Duster, and even I could tell that he was shaken to the ground. "Not a scrap of proof for either of the things you say!"

"My signature will prove that I'm alive. That signature's pretty well known, Duster. And for second proof, they can find a brand-new, half-healed scar of a bullet wound raking across your left side."

No one spoke for some time, and my aching ears could hear the voice of the little alarm clock begin to break out into the silence, making a sort of irregular pulse, as though it were slowing to a stop, and seeming to falter on with a greater and greater difficulty.

At last I heard The Duster say:

"I'll tell you, Manness. I have my share of the Muncie split without a penny gone from it. You can have that!"

"You fool," cried Manness, really breaking out for the first time, "there's a million and a half for the taking in the First National! It's got deposit boxes bulging, to say nothing of cash, besides! Dang your share of the Muncie split! I want you in this with me!"

I heard The Duster breathing like a broken-winded horse.

"Hector," said he, "you've got the thing all lined out safely. Why not go ahead? Then you won't have to make any split with me."

"I had the Muncie business all lined out, too," said Manness. "But what happened? The double-crossing cur of a cashier sold me, and I would be under the sod right now if I hadn't had your fancy gun-work to blow a hole in the trap for me! No, no, Duster, when f walk into the First National vault, I'll have you beside me in the good old way!"

"Why don't I kill you?" says The Duster softly, thoughtfully.

That villain Manness answered as quick as you please: "Because the girl's worth murder or perjury. I looked in on her the other night. I wondered how she could have you so paralyzed. But even I could understand. She even made me, Duster, want to settle down. Do the job with me, Duster. Then ride ten miles across country to the place where I've left that letter to the paper. Take it into your own hands. Read it. Burn it. And then I'm gone out of your life for good! You marry the girl. You're rich, and can lead a beautiful life—"

I didn't wait to hear any more argument, or the answer, but started to crawl out from under the house, because I knew that The Duster was a gone goose.

AFTER I got out into the night, safely away from the wickedness that was in that little shack of a house, I remembered that the horses were to be watered, and I went slowly out to the barn. Dolly threw up her head and nickered at me as I shoved back the sliding door, and somehow the sight of her fine head thrown up so high and the faint flash of her big eyes made me feel worse than ever.

Because it made me think of the difference between men and horses—horses that will run for you till they die, and men that you never can trust. I went to Dolly and untied her halter rope and that of the gelding and led them out to the watering trough. I had pumped it brimful that same evening, so that it took a good bright section of the stars on its face, and even when it had been ruffled by the thrust of the muzzles of the horses—Dolly always gets in above the nose—there were still little specks of fire in the far corners.

I watched those horses drink until a coyote sang off a hilltop behind the town, and the two big heads jerked up, and the ears pricked, and they stamped as if they were frightened to death. They were only playing a game of pretend, because they knew they were as safe as could be, but when I spoke to them—being between the pair—they turned their heads over and drooled water confidingly all over me. Then they drank again, and I wondered over them a little, and wished that the way of a man in life could be as simple and straight as the way of a horse. But when I raised my head, I could look through the trees to the light that shone out of the window of the house toward me; and inside that room I knew that Manness was completing his plan with The Duster.

A fine sight, that light through the night, turning around side of a big tree all faintly green, like a mist. But it made me feel worse still, because I knew that I really loved the poor Duster, and that most certainly I was going to betray him before the morning came!

I didn't want to. I told myself that no matter what happened, I would never do it. But I knew all the time that I would have to, almost like the fellow who tells himself when he leaves the ranch that this time he won't touch a drop when he gets to town. Because that fellow never can get past the first swinging door!

I watered the horses and put them up, and fiddled around, shoveling hay down into the manger. And then I waited a while at the door of the barn, but no matter how much time I killed, I knew that I would have to go to the sheriff.

Because when The Duster said that the First National was loaded with small accounts, I knew that he was only speaking the truest kind of truth. In fact, I knew twenty of the men and women who had those accounts, and the least of them was worth saving.

The Duster had no right to be considered. I argued that out in detail. It was true that I was fond of him. It might even be true that after this one job he would go straight. But his one happiness could not be balanced against the happiness of the scores of people who would be about ruined if the First National went bust.

I thought of them and their faces. And then I thought of Marguerite Lamont and her face, and I can tell you that I felt sick and faint.

However, just as I had known that I would do in the first place, I found that my feet were going down the street toward the sheriff's house, and pretty soon I arrived at it.

There was no more miserable little shanty in Christmas, where you could find plenty of the poorest in every section of the town, even on the top of the hill, near where Lamont's church stood.

Well, I went up to the little house and there was Renney sitting in the doorway smoking away at his pipe. He must have had the eyes of a cat, because there was no light streaming out from the house, and yet he knew me at once.

"Hello, Baldy," says he.

"Hello, Renney," says I. "How are things?"

"Pretty good with me, but kind of failing with the cabbages," says the sheriff.

"What cabbages?" says I.

"Them that I planted out behind the house," says he.

"You got a patch?" I asked, feeling glad that the talk could float along for a while without coming to the point that I would have to make before very long.

"Yeah. I planted 'em out all according to directions. I got them started. I used to sit out there and watch those doggone cabbages growing. I used to tell myself how much they'd sell for, and they'd keep me in cabbage soup for half the year, and leave enough of them over for me to sell a right smart lot and get me a new bridle, which I sure been needing for a long spell. I used to wake up in the night and smell those cabbages out there. I used to get up and stand at the window and watch them waiting there all in line, looking like silver in the moonlight.

"'It's all right, Renney,' I used to tell myself. 'Those cabbages are sure doing fine.'

"Then I'd go back to sleep."

"Well, what happened, sheriff?"

"There comes along an evening when I notice some white moths fluttering around out there. I didn't mind. If they liked the smell of those cabbages, they was free to inhale the bouquet of 'em, as far as I was concerned, because I believe in a liberal policy, even where it comes to moths. But the trouble was that the moths had other ideas than perfume. Pretty soon, I begin to notice that there is holes appearing in the big, broad, tender new leaves of the cabbages. Like they had been burned through with a sunglass!

"'Too bad!' says I. 'And I must look into this.'

"But about that time I'm called away on a trip, and when I come back here, those cabbages of mine look like they'd been used for transfers on a street-car line, they're so punched full of holes. And I know that the moths and their younglings had turned the trick against me. So about all that's left of my cabbage patch is the smell, Baldy, as you can tell for yourself!"

"Yes," says I, "I sure can smell it."

"But as for the sight,"' says he, "I hate to light a lamp in my house lately, because when the light streams out the window it shows me my new bridle all chewed to pieces, and my cabbage soup gone sour. Why don't you set down and have a smoke?"

"I ain't here for long," says I. "I come to talk to you about something."

"Well," said Renney, "I've wanted to talk to you about something, too. How did The Duster come out with Marguerite Lamont? That's what I want to ask."

"I dunno. I should suspect pretty well."

"I'm glad of it," says the sheriff. "That man has been so bad that the other side of the leaf is pretty sure to be worth reading. I used to wonder that a straight shooter like you, Baldy, would work for such a thug as The Duster, but since I've studied him some more and worked over his case, why it seems to me that in a lot of ways The Duster is a straight shooter himself."

"Does it?" said I, surprised.

"You bet! The Duster, now, is a fellow who never would double cross a friend, no matter what the friend did!"

That remark hit me pretty hard, and I stood mulling it over in my mind for a time.

"Sheriff," said I, "the fact is that I want to talk to you about something that The Duster has in mind to do."

"Yes?" says he. "Did The Duster ask you to come down here and talk to me about it? Because," he added, "I figured that we were pretty near friends enough, now, for him to come and talk to me on his own hook."

"He's friendly enough to you," said I, "but the fact is that he's being dragged into a—a—"

The sheriff waited a second and then said:

"Sometimes it's hard to get hold of the right word, ain't it? I remember that my father used to say that words that came hard sometimes weren't the right ones to speak, after all."

"What d'you mean?" said I.

"Why, nothing," said the sheriff. "How did you leave The Duster?"

"I left him on a high place, walkin' a tight rope," said I.

"So you came for help?"

"In a way, yes."

"Well, a fellow like The Duster is best left alone, in a pinch."

"Sheriff," I said desperately. "The fact is that The Duster is going to—"

The sheriff was taken with a fit of coughing, and then sneezed, and then cleared his throat loudly.

When he got through with that fit of noise, he seemed to have forgotten that I was talking, and only remembered that The Duster was the theme of it.

"Poor old Duster!" said he. "He's had his hard times—and his good ones. But he's going to have better luck in the long run, I figure, when he's married to Marguerite Lamont. He's a strong man, but she's a stronger woman."

"Stronger than The Duster?" I gasped.

"Aye. She'd die for the right—or for her brothers—or her father—to say nothin' of the man that she picks out to love. The Duster's brave. But she's fearless. He could face death, but she could laugh at it. Oh, yes, she'll be the stronger of the pair, and when the end of the day comes The Duster won't say: 'What have I been doing to-day?' but simply: 'Have I pleased my wife?'"

He finished off, chuckling.

"Does The Duster deserve her?" I asked.

"Who deserves to be followed by as much as a good dog?" said the sheriff, dodging me. "But then, The Duster has his points. As I was saying, he's a man that never would double cross his friends!"