RGL Edition

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL Edition

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

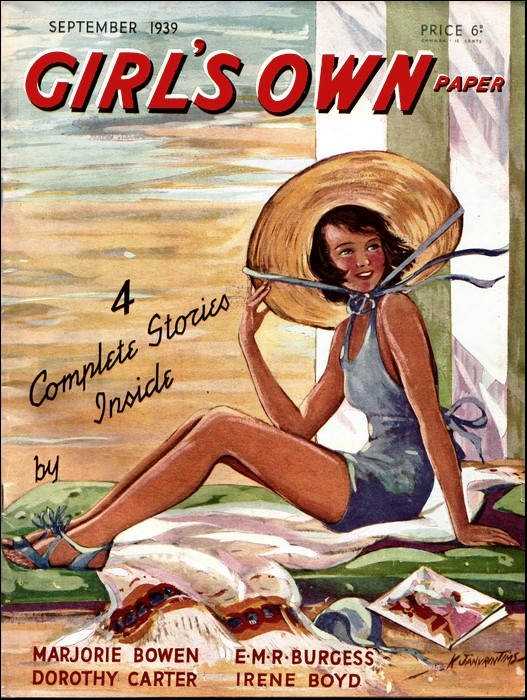

Girl's Own Paper, September 1939,

with "The Necromancers"

LAZARILLO DE TOLMES was in a dilemma. It was one which prevented him from taking his noon-day repose. He sat in his white-walled chamber and looked out on to the dusty street blazing with sun, which he could see through the slats of the green blind.

And as he gazed with unseeing eyes, he bit his finger-tips, and his yellow face was wrinkled with perplexity and chagrin.

He had always lived rather on the edge of things and walked in places where a single mistreading might lead him into danger, but so far he had protected prudently his dubious career and contrived to secure the profits without incurring the perils of his many double dealings.

He passed as a doctor of medicine and was even a professor of Salamanca, but the money that kept up his comfortable home and swelled his private hoard came from other sources than from the practice of his profession.

He was a charlatan and had a large secret sale of lotions, potions and potent drugs for almost any disreputable purpose.

And, further than this, he dabbled in alchemy, in occultism, in charms, and in witchcraft.

This was by far the most profitable part of his business and worth the great risk of discovery which would have meant death in the most hideous manner the officers of the Holy Inquisition could devise.

Tolmes had no belief in the arts he practised; he was a mere cheat and his skill consisted in the apt way he could play on the credulity of his patrons and the ingenuity with which he could give a semblance of magic to his tricks.

He employed an old woman, named Camilla, and a wretched Franciscan by the name of Father Cheves, and in the sordid kitchen of the former he would exhibit his spells and incantations, raise spectres in the darkened mirror and gaze into the future in slabs of polished jet.

The two instruments of his impostures had always worked well under him, been faithful in the performance of their duties, strict in the keeping of his secret and moderate in their demands for pay, and he had commonly left what he called all the witchcraft foolishness to them while he attended to the more reputable business of perfumes, medicines, and potions.

But lately had arisen the serious trouble that kept him brooding at the window and staring into the streets of Madrid at an hour when he was usually comfortably asleep on his couch with a glass of iced sherbet ready for his waking.

A few weeks ago a lady had called upon him and bought some soap and some perfumes.

She was young, handsome and accompanied by a duenna, and in that like many of his clients; she was also masked—this, too, was a common thing.

After making her purchases, she had lingered and after much hesitation, stated that she wanted a charm.

It took Tolmes an hour to wring from her that this was to be a charm to take away the life of her husband.

Tolmes had been startled; never before had such a service been asked of him.

However, the gold the agitated lady showed him soon put him at his ease.

He undertook to do what his fair client asked of him, destroy her husband under the guise of a long lingering illness.

He felt that he was justified in doing this with a clear conscience, since he knew it to be utterly out of his power to inflict any illness on anyone by means of magic.

And when, finally, he should have to confess that the experiment had been a failure, he could alway put the blame on refractory spirits, and his client would be afraid to ask him to disgorge his unearned gains.

So Tolmes had settled the question, very comfortably for himself, and so, for a few weeks the matter had stood.

THE lady had reluctantly disclosed the name of her husband, a court official; old Camilla had hung about his residence to obtain his likeness and an effigy of him had been constructed in hard wax and placed before a slow fire in the witch's kitchen, where it was daily stuck with pins which were supposed to hasten the end of the victim.

Tolmes had given no more thought to this mummery, as the lady paid regularly and made no complaint, until a few days ago when she had visited him, radiant with excitement, to say that her husband was now confined to bed and was rapidly sinking into great feebleness of mind and body.

He had taken, in amazement and consternation, the necklace she had thrust on him to pay for a continuation of the charm, and that evening had hurried round to old Camilla's kitchen near the river.

What he had seen and heard there had given him a very strange and uncomfortable sensation.

He waited, he watched and judged, and he came to the terrible conclusion that these two miserable tools of his, whom he had always regarded as pitiful tricksters, had actually got into touch with the unseen world of evil and were actually working a spell that was causing the death of an innocent man.

This was the problem before Lazarillo de Tolmes: was he to go on, or was he to draw back? Should he confess his lifelong trickery, disavow his accomplices and return what was now blood money, or should he permit the charm to proceed, the victim to die?

This last meant a large sum of money for him, but he shrank from it, low and mean as he was. He had meant to cheat, not to murder.

Besides, he was afraid of the consequences, afraid of discovery, afraid of the spirits themselves, which had been raised at his instructions, but which were utterly beyond his control.

The simplest way would have been to stop the incantations and remove the figure from the fire.

But the witch and the wizard would not stop—they defied him.

A handsome reward had been promised them at the successful termination of their experiment, and they were not going to forgo this for any scruples whatever.

He might dismiss them, but he knew well enough that they would go straight to the Inquisition and save themselves by denouncing him.

The problem was acute, and the position perilous and hateful.

Tolmes groaned aloud.

He wished that he had never seen the handsome lady who was so lavish with her gold and who had led him into this terrible dilemma.

Remorse and fear worked equally in his mind—even while he was wondering what to do, the life of Don Guzman de Tassis, equerry to the King, was ebbing away.

He rose hastily from his blank contemplation of the street and wiped the drops of perspiration from his forehead.

He would again visit old Camilla and try to bring her to reason.

Never before had he been so imprudent as to go to the witch's kitchen in full daylight, but now he did not care; wrapping his mantle round him he hastened out into the glare of the sun and made his way through the intricate back streets which led to the dwelling of old Camilla.

This worthy passed as a washer and carder of wool, and several baskets of bleached yarn stood about the dirty doorway, and the room that gave on to the street was filled with looms and spinning wheels, carding-frames and shuttles, while hanks of wool, dyed and undyed, hung from the smoky roof.

Tolmes made his way through this, and descending a steep flight of stairs at the back of the house, went at once into the underground kitchen—or cellar.

The air of this place was foul and smelling of sulphur and several other potent drugs.

It had a concave roof, from which hung a lantern whose powerful light shed a yellow glow round the windowless chamber.

In the centre of the stone floor was a huge diagram in white chalk, an elaborate pattern of signs and figures.

In the centre of this was a brazier, resting on a single foot.

A slow dead-looking fire burnt here and a thick blue smoke arose and languidly spread abroad.

One side crouched Camilla.

She wore a dark red dress, and her head was tied with a black handkerchief.

On her knees rested a big book with brass clasps; her thin greasy fingers were eagerly turning the pages, and by her side was a porcelain jar from which she continually took handfuls of some aromatic substance and cast it on the flames.

Directly opposite to her sat the monk; his gaze was turned earnestly on the fire, his hands clasped about his knees, which were drawn up almost to his chin.

His wrinkled face, thin, greedy, avaricious, was like that of the hag; each had unkempt grey hair falling over their ears, and each had the same expression of devilish concentration and interest in their task.

Neither looked up at the master when he entered and he did not look at them, but at the third figure.

It was a life-sized wax model of a cavalier, wearing doublet and hose and a deep lace ruff and coloured in natural hues.

SUPPORTED by a rush-bottomed stool, it stood erect behind the fire, and features and limbs were already blurred and wasted by the heat. The face seemed to wear an expression of distress and the wax had run on the cheeks into the likeness of tears.

Tolmes came to the fourth side of the fire, completing the strange group.

Credulity fought with disbelief as he gazed at these creatures he had so long despised and at all the implements of his former cheatings and tricks.

Could devils and spirits really be invoked by these stupid, clumsy means?

Yet that very morning his cautious inquiries had elicited the information that Don Guzman was worse—weaker every hour.

Camilla threw on some spices and a fragrant odour arose.

She then again consulted her book and whispered something across the brazier to the monk.

Tolmes could bear it no longer.

"This must stop." Fear lent firmness to his tones.

The old woman glanced disdainfully at him.

The monk began to mutter an incantation under his breath.

Tolmes was disgusted.

"Do you think that you can deceive me?" he cried.

"Do you think that you can deceive us?" answered the Franciscan harshly, "You have no power at all, and now that you see we have, you are frightened."

Never before had his dependents spoken in such a tone to Tolmes. Indignation and rage made him pale and stammer, "Don Guzman is dying!"

Old Camilla looked up, mumbling her lean jaws viscously.

"Well, did not you take money to kill him? Did not you pay us to undertake this experiment, which is being perfectly successful?"

And her wicked eyes glanced disdainfully at the wretched wax figure.

The truth, a stranger indeed to Tolmes, was forced from him by this insolence of his instruments.

"You know well enough, both of you, that it was only jugglery."

"You never said so," sneered the monk, "You boasted to the lady you could do anything, even raise the dead."

"What is that to you?" cried Tolmes in a rage, "You knew my intention, ruffian that you are!"

"You told us to work a spell on Don Guzman de Tassis," replied the monk doggedly.

"Well, well, let it be now, in the name of heaven," exclaimed the wretched charlatan.

"Why should we let it be when we are to be paid a hundred ducats apiece on the gentleman's death?" inquired Camilla sourly.

"Because I order you," said Tolmes.

But his power was gone; they only laughed at him, their former servile humility changed to rude defiance.

Tolmes stared at them with rage mingled with awe.

These two figures formerly regarded by him with contempt as grotesque, almost ridiculous, had now become vested with a mystery and terror which rendered them full of dignity and horror.

How had they, miserable creatures that they were, stumbled on any occult secrets?

He could still hardly credit their power, for he had not believed at all in magic; that was why he had played his tricks so contentedly on the borderlands.

The monk rose from his place and spoke: "Hark ye, our terms are changed now, we shall not take a maravedi less than half of what you get."

"I wash my hands of all of it!" cried Tolmes in a white agitation.

"No, seņor, no," replied the Franciscan, "for you will be useful in getting us clients. Besides," he added, with a leer, "how will you make your noble living?"

Tolmes was silent, cupidity struggled with fear as he thought of the golden opportunities he was throwing away.

"Now we are in touch with the devil," remarked Camilla, "we can certainly make a great deal of money."

"You can make it alone!" cried the charlatan, "I will earn my money in some honest fashion, not this way!"

They laughed in derision.

"You honest!" mocked the hag.

"It will not be so easy for one so long out of practice," said the Franciscan.

Tolmes glared at them in silent, bitter wrath.

"Besides," said Camilla in a practical tone, as she gazed earnestly into the magic fire, "that you, Seņor de Tolmes, are quite in our power now."

"In your power?"

"Certainly. First, we could tell all your customers that you are a cheat, and so ruin you; second, we could denounce you to the Inquisition for the death of Don Guzman; third "—she looked up at him—" we could make a wax image of you, seņor."

Tolmes felt his knees fail beneath him and his heart flutter.

The foul acid atmosphere of the kitchen was like to choke him.

His mouth was hot and dry and his ears buzzed; with helpless eyes he stared at the image of Don Guzman.

"What does she want her husband murdered for?" he asked helplessly.

"One supposes she has found someone better to put in his place," sneered the hag.

"It will be discovered!" lamented Tolmes, "It will be discovered and we shall be burnt! And that was a death I always disliked!"

"You disturb the incantation," said the Franciscan haughtily.

"You will vex the spirit," added Camilla, "and he will do you a mischief." Tolmes shuddered.

He was silent, meditating many strange things. If he forcibly stopped the business (supposing that he could) he would lose his livelihood; if he let it go on he would lose his soul.

It was difficult at the moment to estimate which was of most consequence.

And then there was his conscience.

For he found that he still possessed one; he was genuinely sorry for Don Guzman and began to hate his wicked wife.

In vain he sought about for some means of saving the cavalier without jeopardising his own safety; his brain, usually so fertile in crafty expedient, was a blank on this matter.

He wished, in his despair, that his insubordinate servants would drop dead before him—he could have found it in his heart to have murdered them.

Bitterly he longed for the old quiet, decent life of chicanery.

Bitterly he cursed the day when he had employed two such ruffians as the wretched Camilla and the monk.

A low chuckle of triumph broke from the hag, and Tolmes, glancing in terror at the image, saw that the head had drooped forward and was melting in a long, thick stream of coloured wax.

Tolmes could bear it no longer.

With a strangled cry he ran out of the hideous cellar, up the dark stairs, through the room full of yarn and out into the street.

IT was a relief to be in the warm, clear air and bright sunshine of outer day. But his terror remained with him. The horrid sight his eyes could no longer see remained before his mind.

He resolved to give all the money taken from Don Guzman's wife to the poor and to tell her that he would go no further in the matter.

Fired by this new thought, he hurried along through the heat towards the square white palace of Don Guzman.

Near the gate he met Don Pasquale de Lormes, a rival charlatan and a fellow whom he much disliked.

Tolmes was hurrying on when the other caught him by the cloak.

"Seņor, have you heard the news?"

"What news?"

His tongue seemed to swell in his mouth, he could hardly form the words. The other charlatan sighed, "Don Guzman de Tassis is worse."

"Worse?"

Tolmes was reduced to vain repetition of the other's words, "Much worse."

Tolmes struggled with his terror.

"Why is it such a concern of yours, seņor?" he managed to ask.

"Alas, it is a great concern of mine!" replied Don Pasquale.

"Why?"

"Because he had just appointed me his physician," was the sad answer.

"Physician!"

Even at this moment Tolmes could not let that pass.

"How did you get the position?" he added contemptuously.

"On my merits," said Don Pasquale meekly; he was ever an assuming man.

"Well, then, cure him."

So saying Tolmes tried to pass on; but the other locked his arm in his and drew him under the shade of an ilex tree which hung over the wall of the garden of the Guzman palace.

"I cannot cure him," he said in a confidential and meaning tone.

"Why?"

Tolmes began to tremble.

"Because," said Don Pasquale, still further lowering his voice, "there is magic in it."

"Magic?"

"Nothing less."

"Nonsense!" stammered Tolmes.

"No nonsense at all, my friend. Don Guzman is dying from an incantation."

"Impossible!"

"Not at all—you and I, Don Lazarillo, know well enough.that it is not impossible."

But Don Lazarillo was not going to admit that easily.

Don Pasquale would hear none of his protestations, but locking his arm tighter in his, drew closer to him.

"Dying from an incantation. And I know whose, Don Lazarillo."

The wretched charlatan tried to get away but the other held him tight.

"Do you deny the visit of a certain lady and a duenna, who gave you a necklet of blue stones and red crosses?"

Tolmes groaned in dismay.

"Do you deny that she gave you, besides, a lot of gold and promised you more on the death of Don Guzman?"

Tolmes would have fallen but for the wall behind him.

"And do you deny," continued Don Pasquale, in a low, tense tone, "that the effigy of my unfortunate master is wasting before a slow fire in the kitchen of Dona Camilla, your creature?"

"How did you know?" groaned Tolmes.

"How did I know?" returned the other grandly, "I also am a professor of magic."

Don Lazarillo stared at him in a miserable, abject silence.

"It is my duty," said Don Pasquale, "to denounce you to the Inquisition."

The sallow face of Tolmes turned a lively, greenish hue.

"How much do you want?" he asked in a queer voice.

"Rather a great deal," replied the other, "You see, when Don Guzman dies I lose a very good place."

"How much?" repeated Don Lazarillo feebly.

Don Pasquale named a sum.

Tolmes shivered; it was half his fortune. With a groan he said so.

"The Inquisition," remarked the other, "will take all, including your skin."

Don Lazarillo wiped the damp from his forehead.

"Very well."

"I will come home with you now," said Don Pasquale cheerfully. Tolmes could not refuse.

IN his comfortable little counting house he signed over to his rival five thousand ducats, which was more than half the proceeds of his long life of work, cheating and pilfering.

And was the provision he had put by for his old age.

As soon as it was dark Don Pasquale came to fetch away the treasure.

"You are a lucky man," he remarked, "I might have been hard-hearted."

But Tolmes, who had sat all day motionless, only stared dismally at the yawning mouths of his empty coffers.

All his pity for Don Guzman was now lost in pity for himself and in amazement at that power of magic which he had so long pretended and so long disbelieved in.

As soon as it was completely dark he hurried round to Camilla's kitchen.

The two were still crouching over their fire.

And the wax effigy was now a shapeless mass which was beginning to melt completely away.

"He dies to-night," said Camilla.

"And we had better leave Madrid," said Tolmes sourly.

But his associates were quite out of hand. Even when he told them of Don Pasquale they only smiled.

"We will make a wax figure of him to-morrow," said the monk.

Don Lazarillo was horrified to find that he was inwardly pleased at the idea.

But his elation was short.

"He knows a better magic than you," he said.

"We will see about that," answered Camilla.

Though disconcerted at Don Pasquale's knowledge of their doings, she still stoutly maintained her opinion that she would be able to defeat the rival charlatan on his own grounds.

About the dawn the last drop of wax had melted in the greasy pool on the dirty floor and the untended fire died out.

The two exhausted magicians threw themselves into a corner, and Don Lazarillo staggered home with the weight of murder on his soul.

In the middle of the morning Don Pasquale came to see him.

Tolmes greeted him with a haggard face.

"You need not be frightened," said the other, "Don Guzman is not dead."

"Not dead!"

"No, I cured him, and out of gratitude he has given me a country house and a thousand ducats in gold. In fact, he has been so good to me I feel I ought to denounce you to the Inquisition for attempting his life, after all."

The unhappy Don Lazarillo groaned.

"You have come for the rest of my money!"

"Well, perhaps—you can keep what Don Guzman's wife gave you," he added, "I have no wish for that money."

An hour or so later, Don Lazarillo de Tolmes, homeless and penniless save for the money and the necklace of the wicked masked lady, decided to try his fortune elsewhere than in Madrid.

He soon found that his remaining ducats were false and that the necklace was made of glass, but he never discovered that Don Guzman's illness was a colic caused by a mixture of senna and camomile flowers, over ripe figs and pepper, administered to him by Don Pasquale, or that the lady and the duenna were servant girls hired by the same personage, but to the end of his dubious career he continued to believe in magic.

As for Dona Camilla and the monk, nothing could exceed their disappointment at the sudden recovery of their victim; they spent the rest of their lives trying to discover what had been wrong with the incantation.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.