RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

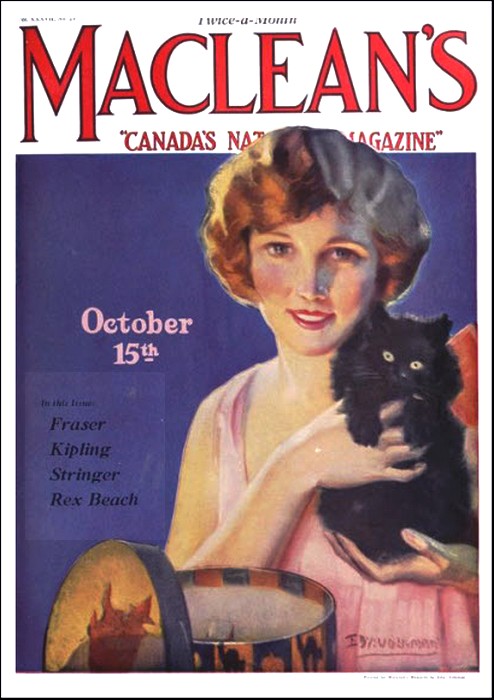

Maclean's, 15 October 1924, with "The Lady Who Lived A Dream"

A CURIOUS sound made Miss Moss look up from her sewing and peer between the geranium leaves and the thick pattern of the Nottingham lace curtains that blocked her cottage window.

Old Wilfrid was going by, riding in his ricketty old goat carriage. It was a tiny goat and a home-made box of a carriage, used for conveying logs. Wilfrid had chosen this lonely stretch of road to climb in and make the little beast drag him; he was a deformed old man, almost idiotic, a gnarled hump of hideous bone covered with repulsive flesh, and heavy, too, with his huge wooden club foot.

The goat thrust her head out, opened a livid pink mouth and gave this harsh cry of protest as she shuddered along with her burden.

Miss Moss gazed dumbly.

She felt that she knew just what the goat was feeling.

It seemed to her that she, too, was being driven on by something hideous and powerful that she had to drag against her wish and strength.

The goat and the old man passed on down the lonely autumn shadowed road and Miss Moss turned flatly to her sewing; she was machining a bodice for the vicar's daughter; it was all queer little pieces and frills and seams and linings. Miss Moss put them together with a fussy air of importance.

It was Saturday and on the other end of the untidy table stood her week's purchases, 2-oz. packages from the village shop.

THE room was small, crowded and dirty, the furniture had the battered dignity of those who support a forlorn cause.

A low fire burnt cautiously in the meagre grate; on the mantelpiece, by the cheap German clock, was a harsh photograph of a rustic in khaki, in front of which was a paper poppy.

It was Armistice week and to-morrow there was to be a special service in the church and it would really be almost half-full and you would see people there who never went any other time.

Miss Moss went every Sunday. She sat on a bentwood chair between the altar and the choir stalls, and when the singing came she stood up and her chin quivered, so that from a distance you might have thought that she sang too.

To-morrow there was to be an anthem and Miss Moss had re-trimmed her hat; it would be a great day for Miss Moss.

She lit her opal-colored lamp with the moon-like globe, and then she went out into the garden and looked at her one rose-bush.

There were two dark red blooms hanging among the dull leaves, slightly sodden and dreary-looking, but Miss Moss thought they were wonderful for November.

To-morrow she would carry them through the village, and one she would leave on the base of the War Memorial, that looked half like a sign-post and half like a gravestone, and the other she would take into the Church and place in the shelf case vases on the table under the list of the village fallen.

And everyone would know she was doing this in memory of Charlie Warren, the gardener at the vicarage, and everyone would remember what a sad romance she had had and how he had been killed before she had ever been able to marry him, or even tell people she was going to marry him.

MISS MOSS looked at the photograph of Charlie Warren when she came back into the house; she had picked the two roses in case it rained in the night, and she set them on the chimney piece as if she set them on a shrine.

To-morrow she would be quite a person of importance; everyone would think of her romance and how she "had given her man" and when the vicar spoke of "those who mourned loved ones" she would know that she was included.

She took out her hat, a shapeless brown felt on which rosettes, feathers and clusters of beads were pinned at odd intervals; she patted it lovingly and drew the two long quills carefully through her fingers.

It made her think of angels, big, firm, white wings, like a Christmas goose's wings.

Miss Moss went to the square of looking-glass, that hung between a colored print of the Prince of Wales and a view of Margate.

Her mouth would not quite shut over her two remaining teeth; her complexion was of a bilious paleness, curiously flecked with brown, her nose had size and no substance, the nostrils looked too narrow to admit even her imperceptible breath.

She wore a chest protector above and beneath her narrow bodice; there was cotton-wool in her ears and about her clung a faint yet pungent odor of cloves and camphor.

Her purblind eyes, the tint of milky cocoa, were further dimmed by spectacles; with awkward fingers she put on the hat, tugging it down over her ears; then with the aid of a long pin she fastened over her left ear a long tassel of varicolored beads, the fallen fruit of some jumble sale, that had in turn disfigured a lamp shade, a scarf, a bag and a Chinese doll.

A STEP and a knock—Miss Moss was expecting this; she thought feebly of the goat with the livid pink mouth of protest; but the beast had continued to drag along her hideous hate and Miss Moss went to the door.

Of course it was the new cook from the Vicarage, the London woman who had relations in Stockwell; Miss Moss admitted Nemesis and put her kettle on the fire.

"Looked in for a cup of tea, Mrs. Galpin?" she asked sharply.

"Can't say as I have." Mrs. Galpin flopped into the chair nearest the miserable fire that she glanced at with contempt. "I've only got half-an-hour, hurried like—but I had to let you know I'd heard from Stockwell."

Miss Moss rattled and clashed out two cups and a tea-pot; they appeared to leap from some hiding-place; she brought out cake from a paper and a tin, unswathed it and licked her fingers.

"Can't say I like yer hat," added Mrs. Galpin, who wore black bonnets of sober dignity, "leastways not the tassel."

"I was only trying it," said Miss Moss in her thin, genteel voice.

"Well, I should leave off. Old mutton dressed up like lamb don't deceive no one. You've got more bits on that old shape than ever I wasted money on in a life-time."

"I thought it was quite my coloring," said Miss Moss obstinately.

Mrs. Galpin returned heavily to the original attack.

"I've heard from Stockwell. From me relations there."

"I knowed you would," said Miss Moss with resigned bitterness.

"And it is the same Charlie Warren what keeps the green-grocery shop."

"Same as who?" quavered Miss Moss with rabbit-like defiance.

Mrs. Galpin nodded to the photo on the mantelpiece.

"Same as him. With the poppy and the roses. Me don't need no flowers—see him trying to sell 'em off half dead, Saturday nights—"

"He wasn't killed!" murmured Miss Moss, tumbling cascades of powdered tea into the purplish brown tea-pot.

"You know it," said Mrs. Galpin scornfully. "That was a mistake got into the country paper and you knew it. Miss Moss. And you let 'em put his name on the war memorial and in the Church. And you gave out he was going to marry yer!"

MISS MOSS made the tea in mulish silence.

"Soon as I heard that name Charlie Warren, when I come here, I thinks of the young fellah at Stockwell; he came from Kent and him a gardener, too, I thought it was the very same, and so it is—fancy you. Miss Moss, telling them lies!"

"I'm sure I thought he was killed, seeing it in the papers," flustered Miss Moss,

"But he told my people, when they spoke of me being here how he'd worked here for a spell," protested Mrs. Galpin, "and he remembered you all right—said he'd written and told yer he was invalided out and setting up in Stockwell, and married; said he felt he oughter after all the parcels yer sent him."

"It was in the papers he was killed, no one here knows any better," said Miss Moss, nervously mumbling a piece of cake,

Mrs. Galpin sipped the leathery tea.

"You took good care of that!" she nodded. "Wid yer fairy tales, indeed! He must be twenty years younger than you, Miss Moss."

"Eighteen," said Miss Moss, hurriedly. "Eighteen."

"Pore young fellah!" cried Mrs. Galpin. "And you spreading round the tale he was after yer and mucking up his picture with poppies! It's a shime."

"He don't mind," Miss Moss defended herself. "He don't know—no one here don't know he's alive, and he don't know he's dead."

"It's a shime," repeated Mrs. Galpin. "Hoodwinkin' a whole village. Shows the one-eyed place it is. As I've found it."

MISS MOSS sipped her tea: she betrayed traces of excitement.

"Where's the harm=" she asked. "Everyone respects him—with his name on the memorial and in the church —it's better to be an angel what's prayed and sung about, one of them heroes the country's proud of— than one of them ex-service men everyone's sick and tired of—respects him, that's what everyone does now, thinking him in Heaven. They wouldn't think anything of him if they knowed he was in Stockwell."

"And what would they think of you if they knowed the lies you'd told—about marrying him?"

Miss Moss held her head high.

"I don't know about lies, Mrs. Galpin. He had a fancy for me."

"Why didn't he come back for you then, instead of marrying some one else?"

"That's my cross," gulped Miss Moss. "Some of us 'as them."

"Not that kind—if we keeps our eyes open," said Mrs. Galpin rising. "You should have got a husband easily before you had that fussy taste in hats—well, I'm off."

She paused, brushed the crumbs off her "raincoat" that was drawn over her print dress.

"I should tike away them flowers if I was yer," she suggested.

"They're for the service to-morrow," said Miss Moss in agitation.

"You're never going—now?" demanded the cook, "taking on like a widder when the man's alive and never asked yer. Well, I am surprised, Miss Moss."

MISS MOSS shivered; for years she lived on this romantic prestige of the non-existent love story, the false death; her loss had been like a halo round her drabness; she clasped her hands tight and misery made the loose muscles of her face wobble.

If only it had been true—to have had a man, to have lost a man—if only it had been true.... She thought of to-morrow, the special anthem, the sermon, the sympathetic glances, herself in the choir, bowed with resigned grief, herself placing the two flowers, one on the memorial, one in the church.... She-would have worn the hat she had re-trimmed; she liked the tassel, really—and white cotton gloves and a necklace of Bethlehem mother-o'-pearl and a chain of Job's tears—and people would have said—"It's very sad for Miss Moss."

"I don't say I should have liked this to get about," she murmured.

"No, I believe you," said Mrs. Galpin, "but I don't see no reason to be a party to your goings on."

Her look, her attitude held threat. Miss Moss wilted as the guilty might in the glare of Heaven's lightning.

SHE clutched at her hat and fumbled at the goose's quill; it gave her a dismal courage, for it made her think of what she would lose if Mrs. Galpin exploded her secret... the seat in the choir, the respect, the kindness, the glory of her lover's name, cut deep, in stone and brass... they'd erase it... and how they'd laugh, at least the young women; women who had everything were so cruel... angels' wings—she felt them rushing away from her.

"I could give you five pounds," said Miss Moss.

"Five pounds!" Mrs. Galpin was plainly impressed.

"Four pounds, eighteen shillings and sevenpence," corrected Miss Moss nervously.

Mrs. Galpin hesitated.

"It 'ud come in useful for Christmas," she conceded. "And it's no affair of mine if you like to make a fool of yourself."

"No one will know if you don't tell," urged Miss Moss.

She knelt down jerkily, and began fumbling in the bottom of a cupboard packed tight with tangled odds of cuttings and ends of silk and wool. She dragged out a battered cash-box and unlocked it and counted out the money under the beady eyes of Mrs. Galpin.

"You're a woman of means." that lady remarked. "I suppose you do pretty well with the dress making in a place like this where no one knows what's what. I don't want the sevenpence; well, I won't say a word, you'll find me fair, Miss Moss."

WITH a pitying look she was gone, folding the dirty paper notes and putting the heavy silver coins into her clumsy purse.

Miss Moss looked dismally into the despoiled cash-box; a letter lay at the bottom.

It took a long while to collect nearly five pounds when you could only put by pence at a time; but Miss Moss resolved to start at once... sevenpence, she'd got seven pence, and when the Vicar's daughter paid her she could put another shilling... and doing without margarine, five pence a week.

She peered at the paper poppy and the two roses; all three looked equally lifeless; one wasn't real, like her romance.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.