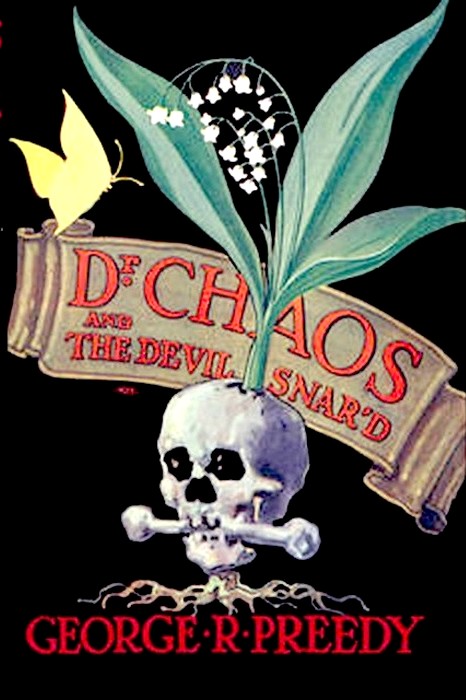

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

"Dr. Chaos and the Devil Snar'd," Cassell, London, 1933

Dr. Chaos is a brilliant but morally ambiguous scientist whose experiments push the boundaries of life and death. His obsession with controlling fate and bending natural laws leads him into increasingly dark territory. Set in old London, the novel is eerie, cerebral, and richly atmospheric, with Bowen's signature blend of historical detail and gothic suspense.

".... At my back I always hear

Time's winged chariot hurrying near;

And yonder all before us lie

Deserts of Vast Eternity."

Andrew Marvell

THE upper part of the house in the alley which ran between Holborn and Lincoln's Inn had long been empty; the lower floor was occupied by a taciturn watchmaker whose window was full of medley of curious objects. The passage was dark and narrow, two posts at either end prevented any but foot-passengers passing through; the houses had once been respectable dwelling-places, but had long since fallen into decay and disrepute and most of them were now used as storehouses for the goods of the little shops beneath. There was a print-seller, a cobbler, an old woman who sold haberdashery, and another who made toffee and coconut tart.

The watchmaker's shop was at one corner near the posts that divided the alley from the large cobbled square of Lincoln's Inn Fields and the fine opulent mansions of brick and stone. The watchmaker, whose name, Uriah Lilliecarp, was written in a tall, scrolling hand in gold letters above the shop, seemed to do but little business beyond that of the making and repairing of watches and clocks, for the stock behind the dirty glass of the bow-fronted window never altered. The bundles of heavy silver knives and forks with foliated handles, the cases of knives in horn and agate tarnished unheeded from week to week. And the various antique clocks in brass and silver-gilt remained stopped, each at a different hour, until the rusted hands dropped from the dials on which the figures were no longer decipherable.

Among there heavier objects were a few cases of jewels, cut steel buckles and sword-tassels, a necklace of large pink stones that were like drops of blood curdling into milk, several little broken toys in gold and silver, and here and there a faded miniature showing in a broken leather case. And always, as long as anyone who passed down the passage could remember, the sparrows nested undisturbed about the chimney-pots above the watchmaker's shop.

One day in early spring, the boards were taken down from in front of the broken casement of the upper floor, repaired with clean glass, and hung with curtains of green serge, while on a narrow door which gave on to the passage and which served both the watchmaker and the upper part of the house, a placard was put out on which was written: "Dr. Chaos, Doctor of Physics"; under this was a list of various medicines and their properties and the prices at which Dr. Chaos sold lotions, drinks, ointments and pills.

This was sufficient of a novelty to arouse the curiosity of the passers-by, and those who had occasion to step into Mr. Lilliecarp's shop for the repair of a watch-glass or the works of a clock, asked him, where he sat in a corner of the window catching the scanty light of the alley, who was the new-comer, and what were his antecedents and pretensions?

Mr. Lilliecarp, however, a man with a white greasy skin and pale strained eyes, who seemed to have neither age nor character, knew nothing. He himself slept in a little room at the back of the shop and had been there more years than anyone could remember.

The letting of the upper part of the house, he muttered, we nothing to do with him, and those who were curious must make inquiries of the landlord.

Nobody was sufficiently interested to go to this amount of trouble. They smiled, shrugged, passed on, and forgot Dr. Chaos and his placard. This, however, attracted the attention of the Ancient Royal College of Physicians who, by virtue of their Royal Charter from His Gracious Majesty King Henry VII, in peremptory fashion bade Dr. Chaos remove his board. They also summoned him to appear before their Council and to explain his pretensions, display his diplomas, prove his knowledge, or be regarded as an impostor and a cheat.

Dr. Chaos made no reply to this challenge, but he complied with the law. He removed the offending board an substituted it by another on which was merely written: "Dr. Chaos".

One evening he came down into the watchmaker's shop and asked him to mend a chain for him. It was in very delicate linked red gold. Uriah Lilliecarp looked at it with that interest and curiosity which he no longer had for anything save matters appertaining to his craft. He asked questions about the gold, where it had been assayed and where it had been worked; he remarked that it must be of considerable value owing to its great fineness, for it was almost without alloy and therefore, being too soft, had broken.

Dr. Chaos smiled and replied that the gold had come from mid-Germany.

He sat on the high stool, worn smooth and polished by the patience of many customers, while the watchmaker retiring into his taciturnity set to work to examine and to advise on the repair of the exquisite chain.

"It is not ordinary gold," he grumbled at last, "and I do not know if I am capable of mending it. You must leave it with me for a least a day or two."

"How dark it grows in the shop," replied Dr. Chaos. "Had you not better light a candle?"

"Thank you, I can still see quite well here by the window, though it is true that daylight leaves the alley very early."

"I wonder you do not choose a better position for work so delicate and requiring so much light."

The watchmaker came to the counter and stared at his visitor through the dusk.

"I might say the same of you. Why have you taken those old and disused rooms? I can promise you that you will get very little practice here."

The two men looked intently one at the other. The person who named himself Dr. Chaos was of an odd and extraordinary appearance, neither young nor old, heavily made, yet with a look of swiftness as if no occasion would find him at disadvantage. He seemed like one ever on the alert, who could strike or run or shout or command instantly, powerfully, and with success. His head was large, but his features were small, neat, bloodless and obscured first by a pair of silver-rimmed spectacles and secondly by the shadow of a large, tow-coloured wig which was in need of curling and dressing. His clothes were shabby and non-descript, his powerful and finely-formed hands stained from dyes and chemicals. He spoke with a foreign accent. He would have well passed in a crowd for a lawyer or doctor of a meaner sort, yet, on a close inspection there was something peculiar about the man.

Uriah Lilliecarp lit the candle of mutton-fat that he might the better inspect the visitor. Not that the watchmaker's curiosity was aroused, for he had no longer any interest in human affairs, but he had thought, without fear or surprise: "Perhaps the fellow is a rogue, and has taken the rooms in order one night to murder me and rob my goods," and he added in his mind: "I shall have some bolts put on my door and sleep safely." Then he remembered the gold chain and his thin lips curled with a dry smile, for it was worth all his belongings put together.

"Why have you come to England?" he asked, watching the new flame melt the hard yellow fat of the candle.

"I have practised my business in many cities—it is not like the first time that I have been to London. Very likely I shall not stay long."

"What is your business?" asked the watchmaker indifferently.

He fixed his blurred glance—for his eyes were blood-shot and tired through concentrating on minute pieces of mechanism and handling very small instruments— on the face of the stranger. He saw that the pinched features were overcast by an expression of despair which gave them almost a deathlike look, as if they were settling and fixing into the likeness of a stony mask.

"If you come upstairs one day I will show you my business. Physic is not my only profession; I am an alchemist, a great adept. If I told you I knew hot wot make gold, would you, with that chain in your possession, laugh at me?"

"I do not concern myself," replied the watchmaker, "with laughing at anything. I have heard before of gentlemen with such pretensions and even met them. I was not, in my youth, as quiet as I am now, but travelled abroad. But these magicians always seemed in poverty, despite their golden secrets, and I commonly heard them named impostors, charlatans, and frauds."

Dr. Chaos was not offended at this plain speaking. He replied:

"I follow out my own purposes in my own way. I have greater powers than you, or perhaps any others, would think. If anyone should come into your shop and want other things to mend beside watches, pray send them up to me and I will remit something to you of my fee."

"Money is of little use to me," muttered the watchmaker. "I have neither wife, child, nor chattel. I work here in my window all day, and sleep well, in the bed I have made myself, all night, and I eat with relish, ay, and drink with zest, the pies and ale sent in to me from the cookshop and the tavern."

"Do you, then, never dream?" asked Dr. Chaos.

"Very likely, in my sleep. When I wake I forget everything."

"I see you are an honest man," remarked the stranger. His spectacles in their silver rims flashed in the strengthening light of the squat candle. " I trust you with my gold chain. I suppose you have your stop strongly locked at night, and the watchman is warned that you have treasures here?"

"It is safe enough; but if you have any doubt, take it upstairs with you and bring it down to me in the morning."

Dr. Chaos bowed with a certain foreign and stately grace that the watchmaker despised. As he took his way back to the upper part of the house Mr. Lilliecarp put away his instruments for the night, then went outside and directed the boy, who came always at this hour to put up the shutters and drop in place the iron bars across them. He heard the man upstairs walking to and fro, and saw a light in the windows— looking on to the alley—which had been so long shuttered and sealed with dust and cobwebs.

The spring air was chill, the street lamps the colour of primroses in the thickening darkness of the passage and the paler bluish shadows of Lincoln's Inn Fields beyond. Multitudes of small stars like chips of ice began to twinkle above the dark crooked lines of the city.

Some people passed so often down the passage that it almost had become part of their lives. They knew all that there was in the windows: when the stock of the pastrywoman changed, when her cakes became stale and fly-blown; at what hour the cobbler would be standing in the doorway in his leather apron, and at what hour he could be seen in the window cutting soles and heels, stitching with hairy fingers and bare arm upraised in the gloom of the shop. They knew, these passers to and fro, when the boys came to put the shutters up at night, when they came to take them down in the morning, and that there was never any sun in the passage, but, even at midday, dark shadows.

One of these people who knew the passage so well was Miss Pleasant Rawlins, who had come to and fro between Holborn and Lincoln's Inn since she was a small child. She lived with her guardian, Sir Thomas Lemoine, in Great Queen Street, and when she was in town she went every Sunday to a chapel the other side of Holborn, near Gray's Inn. Also, sometimes two or three times a day, she would use the passage to go shopping or visiting her friends in Red Lion Square and Queen's Square, or any such distance that was not far enough away for the coach to be brought out.

She was an independent young woman, and liked, if possible, to go afoot, but she had never been down the passage alone. She was always accompanied by a maid, or a footman, or Miss Jane Vondy her governess. She was seventeen years old, and for the most part of the year she was at school in Hampstead; but, as she was restless and capricious and a great heiress, she was often allowed to come home, and stay, not only for the holidays but at any time that might suit her whim, at the house in Great Queen Street with Miss Vondy.

Miss Pleasant was an orphan, and her guardian was often abroad or at his country place. He did not trouble much about the girl whom he found rather disagreeable and tiresome, but he did his duty by her conscientiously, paying handsomely for her education, and fee'd a number of dependents to wait always upon her and guard her person.

The handsome house in Great Queen Street was Miss Rawlins's own property. She had lived there with her father and mother, both of whom she could remember but slightly. Her father had been killed in the war, and her mother had died so suddenly that people said it was from a broken heart. They had left Miss Pleasant a considerable fortune both in land and in stocks, house property, and in pictures, jewels and furniture.

But, though she was so rich an heiress that her fortune might have been reckoned at no less than thirty thousand pounds—she had few friends, partly on account of her circumstances (having been so early orphaned, without brothers or sisters, and under the guardianship of a man who had but little interest in her), and partly owing to her disposition which was dreamy, brooding and sullen.

She yearned after liberty, yet she did not know what she would have done with it had she had it, she wanted to travel but had no idea what were the places she would like to see. She wanted, and this above all, lovers, yet she could not tell what quality she most admired in men. She greatly needed encouragement and reassuring; she thought, in the secrecy of her proud heart, that she was no beauty, that were it not for her money many might pass her by as a creature without charm or grace.

But here she a little wronged herself. She had a pleasing shape and a flawless complexion, a quality of bright brown hair and grey eyes both lively and gentle. But her teeth caught on her lower lip, which was too full; her forehead was over-high, and she had nothing of that happy expression of docile sweetness which was commonly expected of so young a girl.

The source of all her trouble was that she was lonely and dreamt too much, but no one cared sufficiently about her to fathom her discontent. Miss Vondy did her duty by her and nothing more; the governess was saving against the day when she would be done with this dreary task and be away to Edinburgh and marry a poor gentleman who loved her and waited for her there.

That spring, Miss Pleasant came home from the school in Hampstead. Her excuse was that there had been much illness in that suburb and she feared to risk her health. Miss Daulby, who kept this select and expensive school, gave her consent, so the girl came to the large, precisely-ordered, handsomely-appointed house in Great Queen Street in which there was nobody but the servants. There was nothing for her to do but to go walks with Miss Jane and call on such friends as she knew in the neighbourhood.

The first time she went down the passage she noted that great novelty, the board with the name of "Dr. Chaos". She teased Miss Jane to go into the shop that they might make inquiries as to who this stranger could be, but the governess rebuked her nervously and hastened on. She did not like the look of that board displayed beside the watchmaker's shop, and it gave her, she knew not why, an unpleasant sensation to see those windows, which she could remember shuttered over for so long, open. At one of them she had seen a large transparent globe in which there were splinters of light caught from the strip of a sky above the passage, and some strange instrument.

"The man is a quack," she said, and Miss Pleasant pouted; this gave her already slightly heavy face a sensuous, unpleasant expression.

When they next passed down the passage she insisted on stopping at the haberdasher's and buying some pins and laces, though Miss Jane protested that the goods were too cheap and common. Little did Miss Pleasant care if they were, for she began immediately, not looking at the boxes that were placed before her, to ask Widow Dawson who was the man who had hung out the board next to Mr. Uriah Lilliecarp's door.

The Widow Dawson had heard nothing good of the stranger. Of course, everyone in the alley had had something to say about him, and those who believed in such things said that he was a wizard, magician, or alchemist, that he affected to brew potions and to make charms.

"Love potions and love charms?" asked Miss Pleasant Rawlins, though Miss Jane frowned and fidgeted and would have her go on with the choosing of her braids and pins.

The haberdasher became prudent and discreet. She really knew nothing. The man called himself a Doctor of Physic, but the name was strange, was it not? She did not think that any sensible person would go to him. He might be a forger or a coiner, though for her part she must say she thought he was peaceful enough. She had seen him coming and going down the passage, mostly in early morning or after dark when the lamps were lit. He walked with a stick, as if he had gout or rheumatism; he bought his food at the pie-shop but drank neither beer nor ale.

"So you see," put in the governess, "this is a most ordinary person and we will waste no more time discussing him. Come, Miss Pleasant, choose your braid and pins and we will be gone." And she frowned at Widow Dawson to say nothing more on this subject lest it should take the fancy of the wilful girl.

Miss Pleasant quite understood their purpose, but was not to be denied indulging her curiosity. Indeed, she seldom denied herself anything.

"But you live above your shop, Mrs. Dawson, and you must be able to observe him if you wish to!"

"Surely, miss, I have something better to do."

The haberdasher spoke self-consciously, for she knew that she had spent many an hour peeping from behind her curtains across the narrow way into the room occupied by Dr. Chaos.

The heiress fingered, without looking at it, a length of scarlet braid.

"Do any people go there? Does he always draw his curtains at night? What does Mr. Lilliecarp know of him? I have a broken watch, I shall take it in to-morrow."

But this was too much for the equanimity of the governess. She insisted that Mrs. Dawson should not these impertinent questions and she hurried the purchases and took away her petulant charge.

"A wizard," sighed Miss Pleasant, as they stepped into the alley. She looked up at the two windows above the watchmaker's where the globe gleamed faintly against the newly-set panes of glass.

"And if he were a wizard," replied the governess crossly, "what need have you of him? You have everything you want, miss, without having recourse to magic."

The girl laughed. The sound of this laugh touched the elder woman, for it was horribly unhappy. The governess thought, with a touch of almost remorse, of her own good fortune, of the man and the home and the agreeable future, safe, protected, awaiting her in Edinburgh. She was sorry for the rich and desolate girl beside her, so she said, in far warmer tones than she usually employed, towards her charge:

"Life has not begun for you yet, Miss Pleasant. You will find a husband, someone who will love you, who will find in you what no one else can, who will think you are different from all the world, and so will change all the world for you."

"Someone who will love me," said Miss Pleasant Rawlins.

They passed the watchmaker's window; the girl would pause—though her companion urged her on—and look in.

"How long those pink stones have been there! I remember them since I was a child, and those piles of silver knives and forks! I wonder who used them last and who will use them next. Is he not a strange man—Mr. Lilliecarp, always seated in that window mending a watch? He reminds me of God, Who, as I suppose, always sits like that in Heaven making souls."

The light was beginning to recede from the sky, it was very quickly dark in the narrow passage. The girl looked up at the two windows above the watchmaker's. She saw a taper lit there, and reflected like many fallen stars in the globe.

"Oh, Miss Vondy, could we but go up, perhaps he would tell our fortunes!"

But the conscientious governess knew that she was with the heiress exactly to prevent such follies as this.

"No, Miss Pleasant, we must go home now, it is getting dark."

"Go home! For what?" asked the girl, and her sad laugh rang down the passage, which was quite empty save for these two debating women. "And what shall we do when we get home? The curtains will be drawn and our dinner will be served and then we shall sit and sew, or perhaps play a game of cards, or I shall sing a song and you will tell me my mistakes. Or you will write to Scotland and I shall read a book. Oh, it is all dull, dull, dull!"

They came out into Lincoln's Inn Square. The sky, pure of any speck of cloud, was the colour of a fading harebell; the creeping air was very still, the houses looked forlorn and shapeless round the dark square.

"It is as cold as if it blew off an iceberg," said Miss Pleasant.

"Whatever makes you think of an iceberg?" asked the governess.

The young girl did not reply, but clung to her arm and looked round absently. There was no one about except a few coachmen who sat idly on their boxes swishing the necks of their sleeping horses with long whips.

Another person to whom the passage was very familiar was Haagen Swendson, a Danish timber merchant whose ship often put in at Rotherhithe. He used the passage because, where it joined Holborn, was a shop where he bought tobacco. This was a short cut for him when he came up from the inn, "The Four Billiard Tables," where he lodged in the Strand.

His ship the Ice Maiden, with a load of deal, put into the Thames soon after Pleasant Rawlins had first noticed the board with the name of "Dr. Chaos" upon its dirty surface.

The young merchant, turning down the familiar passage in search of his favourite tobacco shop, smiled at the board; he had often seen such placards. He wondered a little at one appearing in this place, which has always been to him meticulously respectable, and he pondered, very idly, what manner of clients this Dr. Chaos might hope to obtain.

He had taken this walk more or less mechanically, because it was well known to him and one that he never failed to make frequently when he was in London. And when he reached the tobacconist's shop he stood staring in a self-absorbed fashion through the diamond-paned windows at the pipes and cut tobacco and rose-wood roots displayed there, and presently turned away with his hands in his pockets without making any purchases. Frowning, walking slowly and still absently so that he often jostled into angry passers-by, he came to "The Black Bull" at Holborn, which was a tavern with which he was very familiar.

He entered, ordered a pint of ale, and sat very moodily with his chin in his neckcloth and his hands still in his pockets, his feet thrust out. The ale was served but he did not drink it; people came and went in the busy public parlour but he did not see them. The only thing of which he was conscious was a small coin the finger and thumb of his right hand grasped in his breeches pocket. He was interested in this because he was thinking of money, and this coin represented to his overheated fancy almost the whole of his fortune. He was, briefly, ruined. He did not know how he could possibly tell his father, who was neither very generous nor very wealthy, how he had gambled away, in Copenhagen, far more money than he could possibly pay, and how he had written out bills that he could not hope to meet, and how the whole of his substantial but modest fortune of the timber merchant would not suffice to meet these secret extravagances of his son.

He had left Denmark in an agony, snatching at the chance of the voyage to England as an excuse to put off the day of reckoning, and while he had been on the North Sea, master of the beautiful ship and her company of strong men, he had felt a sense of liberation and freedom, even felt proud in a way, of himself, of his own strength and youth and health, as if he were beyond the possibility of degradation or misfortune.

During those few days he had felt able to battle with any difficulty, and the terrible situation in which he stood had become almost a matter of indifference to him. But when the Ice Maiden had put into the wide reaches of the river gradually narrowing to the docks, and had at last cast anchor amid the fogs and vapours of the alien capital, Haagen Swendson had felt despair return.

He had hardly been able to follow his familiar custom of landing from the ship and, attended by his servants with his baggage, going to his usual lodgings at the tavern in the Strand.

He had now several days of inactivity before him, for he had very little business to transact while the ship should be unloaded and reloaded, and he knew not how he should endure this space of waiting. While he had been in his mood of wild exultation on the sea he had thought that he would use this time in London to raise money; now he realised that though he might be able to make a loan on his own note of hand, and even to raise something on his father's expectations and perhaps be paid in cash for the load of the deal instead of by bills, yet all of this put together would amount to nothing compared with the sums he owed in Copenhagen.

Seated there, with one hand fumbling round the coin in his pocket and the other slack and idle, and his chin in his neckcloth and his heels on the sawdust floor, the young man thought of suicide, but even as the idea come into his head it seemed to him a stupid, a ridiculous action. He could not conceive of himself as dead; he was so much alive that he seemed part of all the life in the world, and he could not imagine an end to all the zest, vigour, and activities that was himself.

At last, with a sudden movement of self-disgust, he plucked out the last coin from his pocket, paid for this untouched drink, and went out again into the sunlight, the pale, northern, melancholy sunlight, and turning down Holborn again came to the passage.

As he passed the watchmaker's shop the young man chanced to glance up, and he saw the object which had so often attracted the curious glance of Pleasant Rawlins, a globe, made of some gleaming material, in which the high lights danced and sparkled. And, as if some chance ray of this light had fallen into his own heart, he felt a sudden thrill of hope. He was not yet lost and damned; there was, at least, a few days' respite before him. He need not be, for the moment, penniless. He could easily discount a bill of his merchant father.

He dare to think, the instinct of the born gambler reviving in him: "Perhaps I might be lucky. With a few pounds in my pocket and chance on my side I might regain hundreds, nay, thousands, and have sufficient to make of me again an honourable man."

These thoughts were so powerful that they had caused him to pause in the narrow passage, and as he stood thus motionless and glancing up at the gleaming object in the window of Dr. Chaos, he saw behind it the large skull and small, pale, death-like features of that person himself, who was without his wig and had a red and white spotted foulard tied around his head so that it seemed almost as if he had bandaged a wound on his brow, for the kerchief appeared blood-stained.

"That is a man who knows something," thought the young Dane, and almost he turned into the narrow doorway beside the board and went up the dark, crooked stairs, to seek out that strange-looking creature and demand if he could be of any help to him in his deep trouble. But he argued with himself: "I am not a boy. My plight cannot be bettered by deals with charlatans. I should know better than this, I must be weakening in my intellect."

He passed on towards Lincoln's Inn Fields. Dr. Chaos leant out of his narrow window and looked after him long and eagerly.

A footman brought to Mr. Uriah Lilliecarp a watch that needed repairing. It was a lady's watch, egg-shaped, crystal back and front so that the works were as visible as the dial. It came, like an egg out of its shell, from the exact-fitting metal case which was enamelled with pink and blue flowers.

The watchmaker had not often been entrusted with so valuable a toy. He examined it with a loving and intent interest and then declared:

"There is nothing the matter with this; it is in perfect order."

The footman grinned.

"My young mistress bade me bring it. She says that it does not keep the time. She will come in herself this afternoon to ask your advice."

"What is the name of this lady who understands so little about watches?"

"Miss Pleasant Rawlins. She is the heiress of Great Queen Street; you will have heard of her of course, Mr. Lilliecarp?"

"I know nothing about any of my neighbours," replied the watchmaker. "They do not in the least interest me."

"Well, however that may be," replied the lackey, lingering on the worn threshold of the little shop, "I suppose you have some curiosity regarding the strange curmudgeon who lodges above—this Dr. Chaos, as he calls himself, and a mighty insolent name for a doctor of physic to give himself, so it seems to me."

"I know nothing about him," replied the watchmaker. "He has been in the shop once on the matter of a trifling repair. I much wonder that I should be so plagued by questions about this fellow. Here, take back your watch, there is nothing amiss with it. It must have cost at least a hundred guineas and was well worth the money."

But the footman refused to take the toy; he did not wish, he said, to disobey orders and lose a good place.

Lounging in the doorway, he endeavoured, with the insolence of a lackey who cannot find sufficient malice to amuse his indolence, to discover what Mr. Uriah Lilliecarp might know of the man who lodged above. But the watchmaker replied: "Nothing!" with so sour a look and so tight a snap of his lips that the footman, with a curse, went his way.

When Mr. Uriah Lilliecarp said: "Nothing!" in reply to the questions about Dr. Chaos, he was not telling the truth. Only twenty-four hours before, when the shutters had been up and the candles lit in the little room at the back of the shop, Dr. Chaos had come down the stairs and forced his company on Mr. Lilliecarp for a least a couple of hours. He had brought his pipe with him and he certainly smoked the most wonderful tobacco—the perfume of it lingered yet about the little shop. He had also brought, in a little pouch of soft leather, a handful of unset gems which interested Mr. Lilliecarp very much. He had often read of such things and he had a large book where there were diagrams and paintings of precious jewels, but he had never handled them. He was pleased and impressed to be able to run them through his fingers: blue, orange, green, and violet fire, hard as brilliant.

Dr. Chaos had seemed indifferent to these pleasures. He had talked of himself and his adventures and of the marvels that had come his way during his progress from one country to another. He had lived on a whaler in the White Seas and descended the silver mines of Nassau; for an entire summer he had dwelt on the summit of one of the mountains of the Caucasus Range and for an entire winter in the valley of the Cashmere.

With Miss Pleasant Rawlins's watch in his hand, Mr. Lilliecarp stood reflectively, trying to think what Dr. Chaos had really talked of the night before. The narrative had held him enthralled at the time, but now he discovered that he could remember very little of it. It had been extraordinary, and although told in a dull monotonous tone he remembered it as something brilliant and glittering.

The watch was very valuable. Mr. Lilliecarp wondered if the little fool to whom it belonged knew that it really was not out of order at all. He locked it carefully away among his greater treasures: set opals, morsels of fluorspar from Derbyshire and bright, gleaming, valueless pebbles of variegated colours.

One still afternoon Miss Pleasant Rawlins came to the alley to claim her watch. She was out alone and this gave her an air of breathless excitement. She scarcely knew how she had achieved so great an adventure; very silly and skilfully she had deceived Miss Vondy, pretending that she had the megrims, and must lie down alone in a shadowed room. And then, when the governess had gone out on her own business, the girl came creeping downstairs, in stockinged feet with her shoes in her hand, opening the big door very carefully and closing it with great precaution, and then, slipping on her shoes and flying round the corner across the cobbles of Lincoln's Inn so that the lazy hackney-coachmen stared at her, and so into the watchmaker's shop where she stood breathless and a little ashamed.

"There is nothing the matter with your watch, miss," said Mr. Lilliecarp sullenly, for he did not like being disturbed at his work, particularly for a frivolous excuse. He unlocked the drawer under the counter and brought out the smooth, egg-shaped crystal, which Miss Pleasant received negligently.

"Yes, it goes very well," she agreed. "My guardian bought if for me in Paris last year for my birthday. I liked it very much at first, but I am now tired of it. Of course, Mr. Lilliecarp, you understood that I only sent it here that I might have the excuse to come and fetch it. I want to ask you something about Dr. Chaos."

Mr. Lilliecarp frowned with annoyance, but the spoilt girl was not to be so easily thwarted. She rested her elbows on the counter and leant forward eagerly, her hood falling back from her bright hair, her slightly prominent eyes sparkling with real excitement as she added:

"Tell me, do many people go up to him? Does he sell love potions and make charms?"

"What should I know of any such matters, Miss Rawlins?"

The watchmaker returned to his work, mounting his stool before the little table in the window.

"If I am so pestered by questions about the fellow I shall have to move."

Miss Rawlins laughed.

"Why, you would never do that, Mr. Lilliecarp, you have been here so many years. I can remember you when I was a very little girl and used to come here with my mother. She brought a necklace once, to be mended. Come now," she insisted in a coaxing tone, "tell me about this man. I saw a curious globe in his window and once, himself, looking out. He has a strange face."

Before Mr. Uriah Lilliecarp could answer, there was a step on the stair and the girl turned quickly and stared through the little side door which had been left partly open. A woman was coming down from Dr. Chaos's room. She was meanly dressed and had an insignificant presence, but there was about her expression and deportment a lively air as if she had received good news. Miss Pleasant Rawlins clapped her hands in an ecstasy.

"See, Mr. Lilliecarp," she said, lowering her voice, "people do go up to him, and that woman looks pleased. He has told her something quite delightful, I am sure."

"It is no business of mine," grumbled Mr. Lilliecarp, fixing his magnifying glass in the eye, and taking up the tweezers with which he lifted his tiny cogs and wheels into place. Then, cautious as he was, he felt it his duty to utter a warning. "This Dr. Chaos may be, for all I know, a rogue and a thief, and in my opinion an honest young woman should have nothing to do with him."

He spoke with some feeling, for he was recently much disgusted with the foreign doctor. He had made an effort over his natural reserve and gone upstairs and visited the strange lodger in his newly-furnished rooms. He had not liked the look of the place nor the manner in which Dr. Chaos greeted him, but he had brought himself to ask for another sight of the jewels with which Dr. Chaos had dazzled his eyes the other evening when he had told him his adventures by the light of the candle in the little room behind the shop. At this, the Doctor had laughed unpleasantly, and had declared with a sneer that those were not jewels but fabrications of glass, or of a material something like glass, which he had been able to make himself by dint of long study and much diligent application to science.

The watchmaker was annoyed that he had been deceived, and he was also suspicious that, when it suited him, Dr. Chaos would endeavour to pass those false gems off as genuine. Perhaps, indeed, that was the purpose for which he had come to London. Dr. Chaos must have read these doubts in the dull eyes of Mr. Lilliecarp, for he said, sarcastically:

"If I had wanted to cheat with the jewels should I have told you that they were only sham?"

And then, with no courtesy, he had closed the door in the face of the watchmaker.

It passed into his mind to tell this story to Miss Rawlins but he could not give himself the fatigue of doing so. He was quite sure that she had no business to be out alone. She was, after all, no affair of his; he did not like her, nor understand her, nor the world in which she moved, so he made no protest as, with another laugh, she slipped the crystal watch into the silk bag which was fastened by long blue ribbons to her waist and excitedly tiptoed out of the shop and up the dark stairs that led to the room of Dr. Chaos.

At the top of the stairs was another door, and on it was the board which Dr. Chaos had been forbidden by the College of Physicians to hang in the alley. Miss Rawlins peered at it speculatively and saw thereon a list of the services which the foreign doctor was prepared to render to his fellow-men. She was much delighted to read that he offered to tell fortunes, to make potions, that he was an expert in washes for the complexion, in pills for the gout, the falling sickness, and quinsies, that he could cast horoscopes and foretell storms on the sea and land.

So much was set forward in plain English, but there was a great deal more in a foreign tongue that might have been Latin or Greek or even Hebrew for all that Miss Pleasant Rawlins knew. She bit her full under-lip in some trepidation and then, with her little bare knuckles, knocked at the dark and formidable-looking door. Her need for haste urged her cowardice; she knew that at any moment her absence from the house in Great Queen Street might be discovered and that Miss Vondy, with the servants or footmen, would come hot-foot after her. It was very likely that the governess, who was no fool, would think of looking for her in the watchmaker's shop. It was true that she had given Charles, the lackey, a gold piece not to say that she had sent him with the watch the other morning, but then she did not trust him and knew that he did not trust her.

When her knock was not instantly answered her spirits fell and the narrow stairway and the dim shadows with which it was full seemed to hold a menace. Her courage ebbed away; she was about to descend the stairs when the door was suddenly opened and Dr. Chaos, in ragged gown, tow wig, with his pinched, pale features and silver-rimmed spectacles which were filled with a dim bluish glass, stood looking down at Miss Pleasant.

"Well, madam," said he, with a grave air of respect that greatly increased her confidence, "what do you want with me? Will you please step inside?" And, with a courteous air, he held open the door.

Miss Pleasant Rawlins thus entered the first of the apartments of Dr. Chaos. She looked round very eagerly, expecting some great wonder or curiosity, but the room was bare and poorly furnished and her disappointment showed in her instant pout.

"Where is the room with the globe in the window?" she demanded.

"That is my private room, workshop and laboratory, and one in which I never allow strangers. You will tell me your business here, if you please, madam."

Dr. Chaos set a plain wooden chair for the spoilt young woman who, having, under the influence of his respectful manner, recovered her full self-assurance, contrived to flounce and toss her high head.

"I've no business; I hoped you were a wise man or a wizard and could tell me something of the future."

"And if I could, madam, what help would that be to you?"

He regarded her keenly, while his long white, capable fingers played along his chin.

"If you knew something of my history, Dr. Chaos, you would be sorry for me," and her full lips quivered with self-pity.

"You are too young to have had much of a history, Miss Rawlins."

"You know my name, then."

"You are almost a neighbour of mine. You live in Great Queen Street just across the square of Lincoln's Inn Fields. I make it my business to find out something of my neighbours."

"So that you can more easily tell their fortune," said she disappointedly. "Is there no magic in it after all?"

At that he smiled in a manner that chilled her flippancy.

"There is magic enough in it for you, madam. Now tell me what you desire."

At that the foolish girl, angling for she knew not what golden bait, related her history and her discontent. She was an heiress and an orphan, at once guarded and lonely. She feared she was unattractive, no amorous adventure had come her way. She was incurably romantic and fancied things from day-dreaming. She longed for a lover—a handsome, gorgeous, splendid lover who would woo her for herself alone, having no care for her fortune. She had scarcely ever seen a man who came up to her expectations, she wanted to know if any such existed and if there was any chance of meeting him. But this she did not tell to Dr. Chaos nor did she need to, he understood her perfectly, leaning against the bare wall biting his forefinger and looking at her while she exposed her soul, at once sly and simple, her heart full of innocent guile, her shallow mind, her empty discontented days.

He knew more about her than she had told him. He was aware, for instance, of such facts as the exact amount of money she had, how much was invested in the Stocks, what her property consisted of, the position of her guardian, the number of servants who attended her, the vigilant devotion of Miss Jane Vondy to her duty. He knew all about the school at Hampstead where Miss Pleasant Rawlins sighed away her idle hours.

"You must have patience," he remarked, and as that was the last word she wished to hear, fierce disappointment sprang into the girl's prominent eyes. She rose pettishly.

"Why, that is what my guardian and what Miss Jane says whenever I complain of anything. Patience indeed! It is true that I am only seventeen, but it already seems to me as if I had waited a lifetime for something to happen."

"Something will happen soon enough," remarked Dr. Chaos in a tone of conviction that again brought the colour to her cheeks, the sparkle to her eyes.

She clasped her hands eagerly.

"Oh, do tell me! I can pay you well. I have nine gold pieces on me now—they are my quarter's allowance—but I do not need to spend them for I run accounts in the shops. See, I would have given you ten, but Charles had to have one for taking the watch this morning and saying nothing about it."

He checked her foolish chatter. He needed no more self-revelations from her, he could see her entire heart and soul clear before him just as Mr. Uriah Lilliecarp could see the works of her watch through its crystal case.

"You must not stay now," he said in a soothing tone. "That would be stupid, would it not? Your absence would be detected and you would be so carefully guarded that you would never be able to get out again."

"Yes, yes, that is very true," she agreed immediately.

"Well, then, you have made my acquaintance and that, for the moment, is enough. I know all about you and I will endeavour to discover something of your future. You must come again. Perhaps you would write a little note, pushed under my door, or even sent through the post, I do not know how much liberty you can contrive," and he gave his sudden disagreeable smile.

Miss Pleasant Rawlins thought that if she had some definite object in view she could contrive a good many secret absences from the mansion in Great Queen Street.

"Can you really tell my fortune? Can you see what is coming to me?"

"Who is coming to you, you mean," smiled Dr. Chaos, opening the door for his foolish client. "Not yet, but I shall soon know everything. You are not so unimportant as you think, my child," he added reassuringly. "A great and glorious destiny is opening before you. You are on the threshold of something entirely new and brilliant. Eat well, sleep well, keep up your heart and reveal yourself to no one."

"When shall I come again?" cried Miss Rawlins, quivering with joy.

"When you can contrive it. Not too soon, I have much to think of. I am also greatly occupied, not only do numbers of people come to consult me but I make many experiments. Next time I will show you my workroom and some of the curious things that I have there. Now you had better hurry home."

And, with a very genteel air, he handed the heiress on to the head of the stair and closed the door in her face. She stood for a second and looked at the placard, which shook with the rattling of the lock into place. Then she tripped downstairs, feeling happier than she had ever felt in her life before. The strange, the new, and the wonderful was opening out before her puzzled and enthralled gaze.

As Miss Pleasant Rawlins stepped into the passage Haagen Swendson was passing. He had changed a bill of his father's, he had money in his pocket; he had eaten a good meal and drunk a bottle of wine, and, moreover, he had been down to the ship and stood again on the deck of the Ice Maiden among his countrymen who were unlading the long, pale pinkish planks of wood. The scent of the sawn pine trees and the sea creeping into port had been in his nostrils and he had felt some faint reflection of the strength and courage he had known when crossing the North Sea.

He had thought of his home, the substantial mansion, the handsome country house in Denmark, of his father, his mother, his brothers and his sisters, and he had felt buttressed and fortified by that stolid life behind him, by all that silent but real affection. It had seemed to him that it was impossible that he should come to real harm, that somehow this horror would lift. Perhaps he might visit a gambling hell that very evening and win back at least a large portion of the money.

So he had turned into the familiar passage with a heart and a step lighter than he had known in the morning and he had determined this time to buy some of his favourite tobacco and not to turn away like a distracted fool from the shop window.

As he passed the watchmaker's he again glanced up at the globe which had caught his eye and his fancy before, and at that moment Miss Pleasant Rawlins stepped into the passage. He looked at her quickly and curiously, at once suspecting that she was a client of Dr. Chaos. He was surprised to see that she was so young and a gentlewoman, but he guessed that she had no right to be out unescorted. He thought her plain and uninteresting, but he marked her expression of elated expectancy just as she marked this same expression on the face of the woman who had visited the doctor before her, and he thought to himself: "I wonder if he could help me after all?"

Miss Rawlins did not notice the young merchant at all. He was on the other side of the passage and her head was in the air and full of whimsies. She was also hurrying, for she wished to reach home before Miss Vondy missed her. If she had noticed him she would certainly have looked at him keenly for he was remarkably handsome, much above the common build and stature, and of a distinction beyond his station and prospects; this beauty of his had been largely his undoing, by getting him into the company of those who had more money and leisure and fewer responsibilities than himself.

When he had bought his tobacco the young Dane lingered in Holborn and turned over in his mind the various places that he knew of in London where they gambled. It was a wild hope that the few pounds in his pocket might be turned into hundreds and thousands, but there was nothing before him but wild hopes, and he recalled, as he leant against the shop window and filled his long pipe with the tobacco he had just bought, that even if he lost all the money there were other things he had which he could turn into money or even pledge as they were—links, studs, buckles, his handsome dress-sword, and even a watch set with sapphires that a woman above him in rank had one given to him in Copenhagen. And remembering the watch which always remained in his pocket, he thought of Mr. Lilliecarp and, like Pleasant Rawlins, decided that a visit to the watchmaker would be an obvious excuse to find out something about Dr. Chaos.

It was most unlikely that the charlatan would be able to help him, indeed, it was most unlikely that any person or thing would ever be able to help him again but the old rogue might know a few tricks that would prove useful in this horrible crisis.

At this point the young man checked his thoughts. He was both honest and honourable, and frowned to think to what desperate extremities he was turning in his mind.

Haagen Swendson passed the board on which was written the name of "Dr. Chaos" and entered Mr. Lilliecarp's shop. Without ado he put the watch set with sapphires on the counter and asked the irritated old man what was the value of the trinket.

"Beyond my buying," replied the watchmaker sharply, for he did not think that the Dane was a customer of his but only one who came spying or inquiring after Dr. Chaos.

The young man replied with native good humour.

"I did not seek to sell it, only to know the value of it in English money."

Mr. Lilliecarp reluctantly took the jewel in his hand. It was an exquisite object, as beautiful and as valuable as that which Miss Pleasant Rawlins had recently left so uselessly in his charge.

"I suppose," he said, "you might get fifty guineas for it." And he added with rude intent: "Unless it is stolen property and the constables are after you."

"No, it is my own," replied the young Dane, who had taken no offence at these uncivil words; he took some mournful pleasure in adding: " I am a gentleman and of some standing," for he did not know how long he would be able to make that boast with propriety.

Mr. Lilliecarp was slightly rebuked. He liked Haagen Swendson almost as much as he had disliked Pleasant Rawlins. Even to the jaundiced eyes of the watchmaker the young man was attractive in his candour and good nature, besides being extremely agreeable to look upon. He was so tall and fair, clear-eyed and fresh complexioned, spoke with such a gleam of white teeth and curve of clear-cut lips, was so neatly and precisely appointed that he seemed to make a light even in the dim, dirty old shop. So that when he asked the question which was now as familiar as it was tiresome to Mr. Lilliecarp that person replied with good humour surprising even to himself, for when the young man said:

"Who is this Dr. Chaos who lives above?" The watchmaker replied:

"He is some sort of quack, and though I am not one to gossip about my neighbours, I would avoid him if I were you. Surely a gentleman of your appearance can be in no need of such as he."

"You would be surprised," said the young man softly, "how much I do need—well, someone."

"I suppose so," said the watchmaker. He stared down at the circle of sapphires on the watch which still remained on the counter. The bright colour, like little stars or mountain flowers, was the brightest thing in the place and these sparkles of azure light dazzled the old man's eyes. He felt inclined to talk, which was a very strange thing for him for he had been largely silent for many, many years.

"You'd hardly believe," he began, "there was a young woman in here now—why, she has everything there is in the world, pampered, rich; why, she had a watch worth a hundred guineas in her hand and a bag full of gold pieces. I know all about her and where she lives and what her fortune is. I've seen her go up and down this passage since she was a little whining child, and now she must run away from her guardians and come in here puling about her troubles and her discontent, asking after this same Dr. Chaos, if you believe it, and running upstairs to see him. She went out but now."

"I saw her," replied the Dane without much interest. "I thought that she had no right to be out alone."

"She'll do something foolish before she's finished." said Mr. Lilliecarp with disgust. "A silly, spoiled creature with her head full of fairy tales."

"She looked happy as if the rogue had told her some good news."

"That wouldn't be difficult would it, sir?"

Mr. Lilliecarp smiled, and the young Dane was fascinated by this contortion on the stiff features.

"Perhaps not," he said. "Do you think this old villain could tell me anything to make me smile?"

He took up the watch and returned it to his pocket. He thought of the woman who had given it to him, he had been very fond of her and hoped much from her affection. She could have put him beyond the reach of his present misery, but the difference between their two stations had been too great, cowardice and pride had overruled her love. At the last minute she had drawn back. Very likely he would never see her again, or, what was worse, at such a distance that they would never speak.

"Fifty guineas," he repeated absently. "Of course, it is worth a great deal more than that."

"That is all you will get for it," said Mr. Lilliecarp sourly. His native ill humour returned.

"I am again wasting my time on a customer who is no use to me," he muttered to himself. "This is not an ante-chamber for Dr. Chaos's clients to linger in."

Haagen Swendson smiled.

"But I certainly should pay you for your trouble," said he, bringing out his purse.

But the watchmaker waved him aside and returned to his seat in the window. Haagen Swendson sighed. There was something in the shop lulling to the senses, he would have liked to have lingered there, it seemed a retreat from all his distresses and troubles. His pipe had grown cold, he put it in his pocket, went out at the door without speaking again to the taciturn watchmaker, turned and after only a moment's self-ridicule, up the narrow stairs to the upper door where the board hung which detailed all the pretensions of Dr. Chaos. On reading these the young Dane laughed aloud, and knocked vigorously.

Dr. Chaos answered this summons almost immediately. His tone was quite different from that with which he had greeted the young lady.

"Well, my fine young man, and what can I do for you?" he asked in a tone of hollow joviality, and plucking the reluctant merchant by the sleeve drew him inside. "Why, I am busy to-day", he said with laughs between the words; "quite busy. It seems to me that my stay in London will be extremely profitable."

"To you or to your clients?" asked Haagen Swendson. With a smile at his own folly he glanced round the bare room and at the shabby attire of Dr. Chaos.

Here was a man who obviously could do nothing for himself. Was it likely that he would be able to do anything for others? Dr. Chaos seemed to read the young man's glance and smile, for he said instantly:

"You despise me, no doubt, but maybe I can give you some good advice. I shall not pretend that I know who you are or anything about you. Tell me your story."

The Dane shook his head.

"All I need tell you is that I require, quite definitely, a large sum on money. I am only in London for a few days, and in that short space of time this money must be raised or——" He raised his hand and let it fall again.

"A common enough situation," replied Dr. Chaos. "I have met with it in most cities where I have sojourned. Do you think I can help you?"

"No, I scarcely think that. I came here because I am in a wretched state of unrest. I saw your globe at the window."

"H'm, that seems to attract people," smiled Dr. Chaos. "It is not, of course, so difficult to make money. I have been quite successful in that direction myself on several occasions."

The young merchant laughed good-humouredly.

"I quite understand that anyone like yourself would be, as you say, successful; you must know a great many tricks. And then, of course, it is possible for you to move from capital to capital under different names to try different expedients. But for me," he added sadly, "it is different. I am young, I am definitely placed in a city in a certain society, I cannot become a rogue and an adventurer."

"You want, in short," said Dr. Chaos agreeably, "money to enable you to stay in your present position and respectability?"

Haagen Swendson nodded. He was, as Pleasant Rawlins had been, rather depressed by the drab, unfurnished room and the shabby appearance of Dr. Chaos himself. If this man were a clever charlatan he seemed one down on his luck and not likely to be of much use to anyone.

Dr. Chaos read the young man's expression as he had read that of the young woman, and laughed now, as then.

"I can, I repeat, give you some good advice, which no doubt you have greatly lacked. Tell me, first, of your own ideas. You say you are in London for a few days and in that time you must raise a large sum of money. How large is it?"

Haagen Swendson named it, and Dr. Chaos pursed up his lips and moved his head quickly so that the slant light from the window gleamed on his spectacles.

"You must have been a fool," he remarked. "What sort of fun did you get for all that expenditure?"

"I don't want to think of that now, but only how I can get out of my present difficulty. I intend to be quiet and sober for the rest of my life. I very well perceive my own folly; I was under some infatuation."

Dr. Chaos grimaced.

"Well, what do you propose to do? Tell me that first, before I make my suggestions."

"I have a few guineas in my pocket," smiled the young Dane sadly, "and a few valuables. I intended to find out some club where the play is high and again try my luck."

He looked, half-shamefacedly and half-expectantly at Dr. Chaos as he spoke, and laughed again. Then, as if profoundly dissatisfied with himself he rose from the bare chair which the physician had set for him and went to the small window. He was so tall that his fair head almost touched the low ceiling as he peered down into the shadowed passage and into the dust-soiled panes of the tiny shop opposite where there were old books which had not been read for many a year, piled indifferently one on the other, and old portraits where the likenesses were obscured by cobwebs and dirt.

"Do you expect me," asked Dr. Chaos proudly, "to suggest some trick whereby you may load the dice or mark the cards? I am afraid, sir, that all such devices are too well-known, and in the kind of place where you propose to go people will be on the look-out for just such fooleries."

Haagen Swendson looked over the shoulder of his fine blue coat.

"No, I hadn't thought of that," he answered indifferently. "I thought that you might have an idea——"

"I have several. My first advice to you is not to waste any of that money you have gambling. Live plainly and hoard all you have got; you may find that a few odd guineas will make all the difference between success and failure."

"You have then," exclaimed the young merchant eagerly, "thought out some scheme?"

"I have thought of a scheme, yes, I wonder it did not occur to you yourself. Why do you not get married?—an heiress, some woman with plenty of money and not too disagreeable in her person?"

Haagen Swendson shrugged.

"I certainly thought of that. But if a man wants to marry a woman with money he must have money too. There are always parents or guardians, people who make a thousand inquiries, looking after her. There are one or two women whom I could marry at home; they have respectable fortunes, but not sufficient to pay my debts and keep us in comfort, too. Besides, if it came to talk of a marriage there would be contracts, lawyers and settlements, and my father"—here he winced—"would get to know my desperate affairs."

"It is not so difficult as all that," said Dr. Chaos smoothly. "An heiress may be won secretly; she may be married without her guardian's consent; she may even, on occasion, be abducted—a marriage can be arranged in this country very privately. You may have a chaplain up from the Fleet for a few guineas, and at half an hour's notice he will marry you to some trusting creature and make you master of her fortune."

The young Dane looked incredulous. Although he came so frequently to London he did not know much about England.

"But afterwards?" he said, "would not such a marriage be at once annulled?"

"It could not be without a special Act of Parliament. The law in this peculiar country is most obliging towards needy gentlemen like yourself," smiled Dr. Chaos. "I have been here before, and, if I may say so, with due modesty, have had a hand in one or two such enterprises which have been completely successful. The abducting and marrying of an heiress is in itself quite an entertaining sport," he added thoughtfully.

"It does not attract me," replied the young merchant. "If you have nothing better to suggest——" And he reached out for his hat which he had flung on the chair.

"Nothing better to suggest!" cried Dr. Chaos, again moving his head rapidly so that there was an angry gleam on his spectacles. "Surely this is a very easy way of gaining a large sum of money? No, indeed, I have nothing better to suggest. In fact, I know of no other means by which you could, in the space of a few days, nay, a few hours, make yourself master, perhaps, of a hundred thousand pounds in cash, the stocks, and property."

"A hundred thousand pounds," repeated the young man, dazzled by the thought of so large an amount. "That would indeed get me out of my difficulties! I could pay all my creditors without my family or my father knowing anything of it."

"And settle down again to a respectable life with the lady," smiled Dr. Chaos.

"Ah, the lady! That's the difficulty! I don't want to get married and I certainly don't want to have to make love to a strange woman."

"Well, if you are stiff-necked there is the door."

"No, no," said the young man hurriedly; "I can quite see that I must be prepared for something distasteful. Yet you talk so glibly of an heiress; do you know of one? Is there any such creature whom I might come at?"

"She sat here but now," said Dr. Chaos, indicating with a flick of his finger the chair on which lay the young man's hat. "She sat there complaining to me of her hard destiny. She is spoilt and very young and peevish, is at school at Hampstead and longs for a lover."

Haagen Swendson looked downcast. He was no man for an intrigue, especially an intrigue in which a woman was mingled. He thrust his hand in his pocket as he stared down at the dirty boards.

"She has neither father nor mother. Her guardian is often away, she is in the care of servants and the governess. They are quite careless how they allow her to come from the school to the house they have in Great Queen Street. She was able to get away to-day and pay me a visit."

"What did she come here for?" cried the young man with a look of distaste. "With due courtesy, Dr. Chaos, you are no company for a schoolgirl."

"She wanted to know the future, my dear sir. She wanted some kind of excitement. Of course, she longed for me to tell her of a lover. I prophesied everything brilliant and beautiful and sent her away happy."

At this last word Haagen Swendson's blue eyes flashed.

"Ah, that was the little creature who was leaving the shop just as I came past—I remember. Happy!—yes, she did look happy. I noticed nothing else about her," he added regretfully.

"She is not beauty. She has a hundred thousand pounds at a mean computation, almost certainly much more," said Dr. Chaos.

"Her guardian, whoever he may be—I suppose he is a man of wealth and position—would not be likely to think of me as a husband."

"Certainly not. Were you to apply for her hand to Sir Thomas Lemoine you would be thrown out of the house. Did I speak of any such folly as waiting on her guardian!"

"What then am I to do?" asked the Dane reluctantly.

"There are several things that you can do. One way is—you might make her love you. It would not be difficult, I can contrive that you meet here."

Haagen Swendson interrupted hastily.

"I should not care to do that. Indeed, I have no aptitude; I should be clumsy and half-hearted," and he added in a mutter, half under his breath, "there is something very mean about the transaction."

"Then you could abduct her," suggested Dr. Chaos. "I could arrange that also. There are many ways in which it could be done. You only need a coach and a pair of good horses and two o three servants whom I could very easily hire for the occasion. She could be snatched up while she is out walking, or delivered into their hands when she comes here on one of her foolish errands. I need only allow her to stare into the crystal and then someone comes behind and claps a kerchief, with a little laudanum on it, over her mouth."

Again Haagen Swendson interrupted and this time very uneasily.

"That is very horrible, I do not care to even hear it talked about."

"How, then, do you think you are going to get her—if every contrivance is horrible to you? It would be much better if you were to make her love you. There is, however, yet a third way. You may pretend a false arrest: you can get two sham bailiffs who will put her out of her coach and say she is but a cheat who owes her tradesmen money and so you can hurry her off to the sponging-house. And there, when she is thoroughly frightened and distressed, you can tell her that she will be free of all her debts if she has a husband, and then you may come in with a chaplain and so you can be married."

But Haagen Swendson dismissed this suggestion with a shake of his head.

"I cannot do it."

"Then I am afraid you are wasting my time," said Dr. Chaos, thrusting his hands in his pockets and hunching up his shoulders, "and I must charge you a couple of guineas for half an hour's consultation, which, though useless to you, need not be wholly unprofitable for myself."

Without demur the young man searched in his pockets for the money.

"I suppose you think I am a fool?"

"I certainly do. I have known many a fine young fellow put on his feet by such an expedient. For the last few years it has been quite a favourite diversion among our young men of fashion."

The Dane jingled the two guineas in his broad white palm and then asked suddenly:

"This is against the law, the English law. What is the penalty?"

"One that is never enforced," smiled Dr. Chaos.

"But the penalty—there must be one. Tell me. You do not think that I should be so stupid as to embark on this enterprise and not know what I was risking?"

"Considering that you said your affairs were desperate," replied Dr. Chaos angrily; "considering also that I have not the least doubt that even this morning you contemplated suicide"—the way the young man started showed him his surmise was correct; he smiled at the success of this shot in the dark—"I do not think it is for you to be talking of danger. Under an old law of Henry VII the penalty for abducting an heiress is death on the gallows, but we need not think of that for a single moment. The family very seldom prosecutes in these cases and even if you were arrested and tried you would be acquitted. No one need know of the embarrassment of your fortunes and your action would pass as the impatience of a lover. Besides," he added impressively, "here is your protection. You cannot be convicted of such an offence unless the woman herself swears against you, swears that she was forced and married unwillingly under some fear either of death or imprisonment."

"And any woman," said Haagen Swendson, "so outraged would so swear."

"I perceive that you know very little of the fair sex," said Dr. Chaos with an odious smirk. "You must also be a man of singularly little vanity. Let me then assure you that you are quite a personable fellow and that the little victim I have in mind will enjoy the whole affair thoroughly. What did she come here and ask me for if it was not for such an adventure as I have set forth?"

Haagen Swendson laughed sadly and uneasily. He laughed at himself, at destiny, at the charlatan. He despised them all, yet could not find the strength to turn his back on temptation.

"Poor child," he said tenderly. "She came to you to buy dreams and this is what you would sell her."

"Dreams come true," nodded Dr. Chaos. "I think that I shall do her a very good turn. Where would she find a more likely husband? If you will only be a little complacent you may very likely come to love her yourself. She is, after all, quite charming, and so young she might easily be trained. You might make of her," added the quack, "exactly the kind of woman you wish, and how glad your worthy father and mother will be when you take home to them a beautiful English maiden of unexceptional birth and education with a large fortune as a dowry!"

Haagen Swendson listened intently. He could judge the old rogue for exactly what he was worth, yet these scoundrels knew a good deal—they travelled all over the world and picked up experience and wisdom, sly and gutter-bred very often, but none the less extremely useful wherever they went. It must have been through some stroke of good luck that he, in so desperate a plight, had thought of coming up the crooked stairs to the door of the man who named himself Dr. Chaos, for here was a scheme ready-made and not too difficult (though repugnant to all finer feelings), of which he himself had never for one moment thought—to marry by force or guile or treachery an English heiress. There was, in the Dane's blood, something wild and daring, something bold and headstrong, a streak of the sea-rover beneath the deep veneer of the respectability of a man of business. To that part of his nature this reckless enterprise appealed. For the danger he did not give a second thought; he was naturally fearless and it did not occur to him that any woman, much less a schoolgirl, would swear away a man's life.

As he saw it, though he did not trouble to reflect so far, any female creature, however deeply wronged and outraged, would save a gentleman from the gallows by declaring that she had gone willingly to her wedding. He thought of the girl with regret and compunction. As he had said to the quack, she had come in her folly to buy dreams and she was to be offered a fortune-hunter—— He wished that she were more beautiful, a little older, not a fool; and he thought of the woman who had given him the watch set with sapphires.

At the same time he intended to reform and why not have this woman as his wife as well as another? No doubt, as the charlatan had suggested, she was docile and could be well trained.

"Supposing she doesn't come again?" he suggested. "My time is short. I must take up these bills and cognizances when I return to Denmark; I cannot at the utmost, have more than ten days in London."

Anxiety, pitiful to see in one so young, clouded his handsome eyes.

"Leave it to me," said Dr. Chaos; "she will come again and that soon. I can contrive everything—at a price, you know."

"From me and from her, I suppose," said the young man; "how much do you want?"

"Five per cent. on her fortune," replied Dr. Chaos promptly; "that is very little more than government interest, and surely a small price to save you from death and damnation."

He spoke with an ugly menace and shook his lean forefinger at the young man like some hideous schoolmaster suddenly admonishing a pupil.

"Death and damnation!" The words were not too strong. It had been that. To shoot himself, to return to Copenhagen, to face disgrace, worse than disgrace—humiliation, the ruin of those who loved him, to see the name, the family, the firm, all reduced into confusion because of his criminal folly. Better, surely, this design on the person of a schoolgirl. What harm would it do her?—and he could, if he chose, spend the rest of his life in making her happy. He promised himself that, applying a quick salve to a conscience too easily wounded to be a pleasant companion for a man of his temperament.

"Where are you staying?" asked Dr. Chaos.

"At the 'Four Billiard Tables' in the Strand."

"Keep yourself close, don't spend any more money than you can help. I perceive you are well dressed, I suppose you have other fine clothes?"

"Above my station," replied the young man shortly.

Dr. Chaos nodded.

"That is well. You are made for the part, and so is she," he laughed, rubbing his hands together, "and so is she! And in twenty-four hours I shall have heard from her again. I can arrange for you to meet here and we will see what impression you make upon her heart."

Haagen Swendson did not reply to this. He had gone as far in the business as he, for the moment, could. He bowed gravely, and without touching the quack's hand, descended the crooked stairs into the alley where the shadows then lay thick.

The light was already lit in Mr. Lilliecarp's window and he was seated on his high stool, busy with his tweezers, cogs and wheels, as the young merchant passed by into the blue gloom of Lincoln's Inn. The wind blew cold and crept under his warm clothes and his fur-lined cloak; it blew from the river, the sea, from the north, from the ice-floes, or so he imagined. He thought with homesickness of his ship the Ice Maiden so clean-scrubbed and newly-painted with her great figure-head of a high-breasted woman with red drapery girdled round her waist, yellow hair flying back, and staring blue eyes, monstrous, splendid, dauntless.

He wished that he could sleep on the ship, but he did not dare do this because of the comments it would cause. He had a deep nostalgia for his own country and a hatred for this foreign land, even though in it salvation seemed promised. Never before in his careless, protected youth had he counted the cost of folly. He longed for happiness, for safety, for a pure and pleasant affection.

He walked down Great Queen Street and looked at the flat-fronted mansions and wondered in which of them Pleasant Rawlins dwelt. A fragment of paper and a few straws blew down the street; in the gin-shop on the corner of Drury Lane were sounds of loud quarrelling and the yellow flares of lamps fed by rank oil.

Haagen Swendson turned through Covent Garden and walked carefully between the heaped-up garbage of rotting vegetables, decaying flowers and broken fruit. Before the church of St. Paul's he pulled up suddenly like one who meets an unexpected obstacle. He was, at heart, a very religious man, and of a noble and generous disposition. Pale clouds, blue from moonshine, rose curdling into the greenish heavens. The street lamps were lit one by one, primrose-yellow in the dusk. On an impulse that he mistrusted but could not resist, Haagen Swendson turned into the church, which was lit by warm, even, dull yellow light in which the newly-varnished pews and gallery, made of deal such as himself shipped from the pine forests of Norway, glistened. The walls were whitewashed and on them were mural tablets covered by the names and virtues of deceased men and women. On the altar were two vases of lilies.

It did not seem a place in which to pray, but the young Dane bent his knees shyly in one of the pews, and folding his hands with a touching confidence that he was nearer to God in this place than outside in the streets on which the moon looked down and above which the lonely clouds curdled in the eternal blue.

He could not form his prayer, but he knew that he wanted to put up some petition for himself and for Pleasant Rawlins. He had a childish and a frantic hope that out of the evil he planned some good might come, that out of the dishonour he was more than half-inclined to undertake, honour might grow. Though he could not bring himself to lure her to love him, he thought that he might so far force his inclination as to make himself love her, and he believed, in a kind of confused simplicity, that if he could bring this to pass he would be justified before her, before himself, and before God.

There was an evening service in St. Paul's, and the pew-opener in the black dress and shawl came to set the books in their places. At sight of her the young man rose self-consciously and tiptoed out of the church. The old woman's bleared eyes peered after him, not because she saw he was a foreigner, but because of his considerable handsomeness. She sighed as she went back to her dull task; there was something about the young man that emphasized the ugliness of the church.

Miss Pleasant Rawlins could not sleep that night for fierce excitement. She lay under the heavy rose-coloured worsted curtains of her bed which hung like a cloud in a corner of the room, and made her, crouching on the pillows, appear small and insignificant in comparison.