RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

"Painted Angel," Herbert Jenkins, London, 1938

"Painted Angel," Herbert Jenkins, London, 1938

"Painted Angel," Herbert Jenkins, London, 1938

A traveller going from Berlin to Hamburg disappeared at a small Prussian frontier town under extraordinary circumstances. The search for him, the various accounts of his possible fate given by various people, and the effect of his disappearance on his wife and his friends make up the story that passes from one incident to another in Germany, England and Italy.... Painted Angel, following closely in the tradition of George Preedy's most successful work, reveals a remarkable picture of England and the Continent during the early part of the nineteenth century.

THIS story is based on an historical incident of which there are many varying accounts and that has never been satisfactorily explained. The novel is, however, a work of fiction, all the characters are imaginary and do not refer to real people, save when an historic name is used for one of the minor personages.

The mystery that is the foundation of the story will be familiar to most readers. The solution offered here is the invention of the author. No reference is intended to actual happening nor to the famous family that was involved in this extraordinary occurrence.

George R. Preedy.

Richmond, October, 1937.

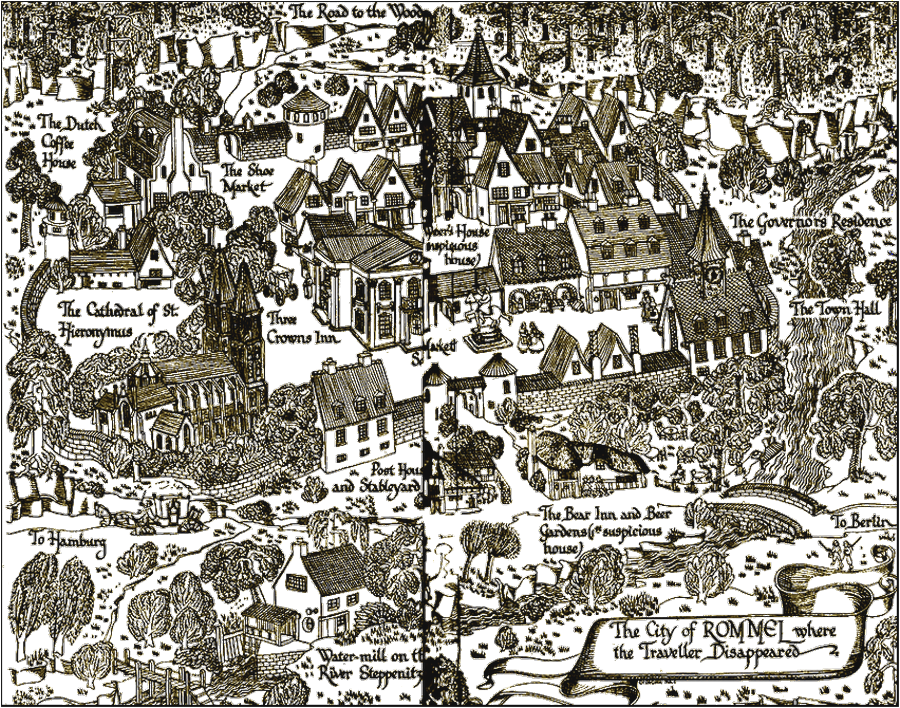

The City of Rommel.

ON a cold, windy afternoon, of Saturday, November 25th, 1809, the post-chaise from Berlin to Hamburg stopped to change horses at Rommel, a small town close to the frontiers of Prussia and Mecklenburg. It was a little late and the postmaster greeted it with an impatient grumble; he had little to do save grumble, for Jacob Scharre was an old decayed fellow who left his work to his wife Elizabeth, his son Anton and his servant Louise Mendel, who between them looked after the post-station and the small tavern adjoining it. The younger Scharre now went out to see if there were letters or travellers for Rommel. There were two passengers in the coach and Anton, an idle gambling fellow of a bad reputation, noted with greed and surprise the cloaks that they wore, sable, one lined and faced with purple velvet, the other with yellow satin. Why did not gentlemen so richly attired travel with their own retinue instead of in the public coach?

This seemed to Anton a most surprising question and he eagerly asked the strangers their destination and plans.

One of the travellers replied that they would proceed later to Hamburg and made enquiries about the hire of a carriage and horses; a servant descended from the box and with the help of Anton took several valises and cases from the coach; these were carried into the tavern where the two travellers had already proceeded.

Frau Scharre kept the one room clean and cheerful; a strong heat came from the earthenware stove and, from the little kitchen at the back, a smell of cooking; Louise Mendel was serving wine, chicken and soup to two Jews in fur caps who sat at the table near the stove.

She looked up as the strangers entered, bringing cold air with them, curtsied and asked what she should serve. She was as astonished as Anton had been by the appearance of the travellers and eyed the sable cloaks with the same kind of greed and amazement. She was a stout girl who often acted as letter carrier; her small eyes, sand-coloured hair and loose mouth gave her a disagreeable expression, but she was fresh and healthy-looking and seemed eager to please.

The Jews, who appeared to be respectable merchants saluted the newcomers very civilly and returned to their meal, while, drawing out account books, they discussed gains and losses in low tones.

Old Scharre himself, who had caught a glimpse of the travellers from the windows of the post-house, came hobbling in, curious and a little suspicious; only recently had Prussia been freed from the domination of the all-conquering French, who still held the fortresses of the country and what had been the Holy Roman Empire was honeycombed with the agents and spies of Napoleon. Scharre had been a sergeant in the army of King Frederic Henry and knew a thing or two, he flattered himself; these men were foreigners he was sure, though they were talking German together.

In reply to his enquiries the younger traveller said abruptly, "We are merchants, travelling to Hamburg—we will have a little food, if you please, and presently a carriage with four horses, as I have already told the ostler."

"Gentlemen," said Scharre, "this is a poor place for you. I make no pretensions. The gentry go to The Three Crowns in the market-place."

"It will do very well," replied the stranger. "We shall not stay long."

He seemed nervous and exhausted, and, sinking into the wooden chair by the fire, rested his head in his hand; his companion was silent and appeared engrossed in the study of a folding pocket map.

Elizabeth Scharre, a robust woman and Jacob's second wife, came in to set another table in the warm circle near the stove, and she too had her quick, inquisitive stare at the travellers. The short day was coming to an end and the oil-lamps were lit by Louise; the two women went to and from the kitchen and the dining-room. Scharre loitered by the stove; in the kitchen Anton tried to get some information from the manservant who sat with the baggage by his side, drinking beer. He was, however, a taciturn Swiss fellow, and knew nothing, or would say nothing beyond that his master, the younger traveller, had engaged him in Vienna to travel to Hamburg; he added: "And what is our business to do with you?"

"Well," said Anton Scharre, "the police are very active, now we've got rid of the French, and the new government is trying to clean things up a bit after so many years of war; and Rommel being nearly a frontier town, we here at the post-station have been asked to keep our eye on the travellers who pass through."

"I suppose," replied the Swiss stolidly, "you get a lot of scum and rabble of all sorts, on a highway between a capital and a big port, eh?"

"We do. There are scoundrels of every kind abroad—old soldiers too," he winked heavily. "I wonder that your master thinks it safe to travel without a guard—why those cloaks he and his friend are wearing—"

The servant did not answer and Anton started on another tack.

"There's some queer places even in Rommel, that the police have got an eye on, believe me. The new Governor says we've got a bad name and he's going to—well, clean it up a bit. That place opposite, The Great Bear, well, the daughters of the house aren't ugly. The French used to go there."

The words conveyed a sly, half-menacing warning as well as curiosity, as if the man was demanding the help of the servant in some design on the master, or, at least, trying to probe into the reason for this foolish kind of travelling in such times as these; but the Swiss merely looked down at the handsome luggage beside him and was silent.

Anton then went into the dining-room; the Jews who had come across country and were taking the night coach to Hamburg were still sitting over their coffee, conversing in gentle voices; the two travellers were by the stove, the younger talking to Jacob Scharre.

"Who is the Governor of Rommel?"

"Captain the Graf Von Alten, sir."

" Where could I find him?"

"The Governor's house is in the market-square, he lodges near The Three Crowns, sir."

Perceiving Anton enter the room, the young man interrupted the postmaster and said quickly, "The ostler—he shall take me. I must see the Governor."

"That's my son, sir. He will show you the way."

With a nod to his friend, the traveller flung the purple velvet-faced sables over his shoulder, pulled on his peaked cap and with an authoritative gesture motioned Anton to precede him. As they stepped into the cold dusk he said abruptly:

"I am armed, I carry a brace of pistols."

"Wisely, sir," replied the other with a wry smile. "I was telling your man these were dangerous times."

It was now about half-past four o'clock; the post-station was on the outskirts of the town, on the high road at the junction of the road to Rommel; the traveller went, therefore, along this branch road, and after passing along a road bordered by pine-trees, saw before him the mediaeval turrets of the old town rising dark against the dim sky. Lights showed in doors and windows and there were a good many people about among whom showed here and there the uniforms of the Prussian army and those of Mecklenburgers and Imperialists. The King of Prussia was expected to return soon to Koenigsberg and there was every kind of activity in the state just released from the complete dominion of a conqueror and striving to reconstruct after the disastrous war. At Saalfeld, at Jena, and at Averstadt the strength of Prussia had been broken, her King forced to flee to the confines of his dominions and to beg for peace. This had been granted at Tilsit, but on terms that left Frederic William III ruling over a kingdom reduced to the size and significance of a small German state. The recent disaster of Austerlitz had forced the Emperor into a peace as humiliating as that of Tilsit.

The patriotic and able measures of the King of Prussia and his ministers, Herr Stein and Herr Von Hardenberg, had, however, not only set the country up again but instilled new life into the people, and there was no sign of misery or depression in the town of Rommel some eighteen months after Tilsit had degraded the Brandenburger.

Anton Scharre remarked on this to his silent companion, adding slyly:

"You're not French, sir?"

"No, Austrian."

"Ah, well, we don't like the French." Anton, who was a squat, swart man with heavy features, grinned. "And we're afraid of them—spies, sir, spies everywhere."

The traveller did not answer. They had now reached the market-place; this was a large square that seemed too vast for the size of the town; the buildings that surrounded it were in the old German style, with overhanging gabled fronts, or blunt hip roofs, save for one notable exception, an imposing building on classic lines, at the far angle of the square. This consisted of three storeys, each with straight rows of french windows; the façade was plaster and beneath each window was a relief of a laurel wreath and swag; a fine arch led into the coach-yard and an entrance in the centre had doors flung open on a noble staircase. This house was brilliantly lit, the gleam of lamps and candles showing like clusters of stars at all the windows; a board above the door had Gasthaus in scrolling Gothic letters, but it was obvious that the pretentious mansion had originally been built for a nobleman; and there was another entrance in a side street that led to the shoe market.

"That's where you should have stayed, sir," said Anton. "The Three Crowns: it's lit up because they are giving a big ball there to-night—all the nobility, sir."

"Where is the government house?" demanded the traveller with a casual glance at the hotel. Scharre took him to a modest building that housed the offices and apartment of the new governor or Commandant of Rommel. Leaving Scharre in the street, the stranger entered and demanded Graf Von Alten; he was, however, absent. A Lieutenant Wulf received the visitor in a small, dull office; the soldier looked up from his desk, prepared for routine business, and remained staring, his quill in his fingers, at the person of the traveller, as the people in the post-house had stared.

"My name is Bacher. I am an Austrian merchant, travelling to Hamburg; here is my passport." So saying the traveller put his hand into his bosom and drew out a document that he handed to the officer.

As that person read this slowly he was making a furtive scrutiny of Herr Bacher, the officer's attention being first attracted to the sable cloak that was so unusually handsome; but the wearer was more remarkable than his garments. He was about twenty-five years of age, tall and slender, though wide in the shoulders; his features were regular and straight, his complexion fair, his eyes large and blue grey, his hair bright brown, closely curling and growing into small whiskers in front of his ears; his expression was thoughtful, self-absorbed, yet disturbed by spasms of apparent anxiety and distress.

He wore a handsome grey travelling suit, a coat and loose pantaloons or overalls frogged with black braid, a shirt of extremely fine cambric, a black silk stock and a peaked cap of grey cloth with a black tassel; the sables were clasped across his bosom by a cord of knotted silver, a gold seal on an elaborate ribbon of pearls hung from his fob pocket.

Lieutenant Wulf noted that the hand that held out the passport was of singular beauty and adorned by a massive sapphire intaglio. Altogether the impression made by the young man and his attire was of splendour, wealth, uncommon good looks, breeding and brilliancy, all in contrast to that grave, preoccupied air, occasionally shot by wildness or apprehension. The passport—an Austrian one countersigned in Berlin—was in order; looking up from it, the officer asked:

"Well, Herr Bacher, what can I do for you?"

"I am staying for a few hours at the post-station. I should like a guard—at least a couple of men."

"You carry valuables—you are afraid of something?"

"Both. I travel with a friend, Herr Bisschop, and a Swiss servant only. We trade in jewels. I have some varieties with me. I believe that we have been watched, followed—"

The young man spoke rapidly and with so odd an accent that the soldier cocked an eye at the passport. Austrian, eh?

The traveller continued to dwell on the dangers of roads, the disorders and confusion subsequent to the terrible defeat at Austerlitz—the difficulties of travelling at all.

"Prussia is well policed," returned Lieutenant Wulf. "We cannot always prevent beggars and vagabonds from coming across the frontiers but we have few robberies. You shall have your safeguard."

The young man thanked the lieutenant warmly, and the latter, not ill pleased to show his efficiency, called in his orderly and gave his instructions; a quarter of an hour later the traveller returned to Scharre with two stout Prussian carbineers and a corporal behind him, to the amazement and dismay of the ostler.

"I have valuables with me," said Bacher briefly, and Scharre said cunningly that it was a good idea to have the soldiers.

He felt, however, very uneasy; he had a bad reputation and had been in one or two scrapes: the girl Mendel, too, had been in trouble; it was said that the new governor was a severe man. Anton Scharre hoped that this stranger had not been warned against them—it was very odd to ask for a safeguard; if there were complaints of pilferings, old Scharre's job would be lost and with it all their opportunities of gain.

The house where the governor lodged was on the same side of the square as The Three Crowns. Opposite were the Cathedral and the Town Hall, beneath which was a beer-cellar. At the side of this was the street that led to the high road and the post-station.

Instead, however, of crossing the square to return the way that he had come, Herr Bacher told Scharre that he had other business in the town, and passing in front of The Three Crowns, turned round the angle of the hotel, so that Scharre thought that he was going in by the side entrance, perhaps to see the governor who might be there. But Herr Bacher passed on to the shoe market where was a decent hostelry called the Dutch Coffee House. Opposite, the other side of the square, stood a small house a little apart from the others; it was modern, with mansard windows in the high roof and a door with a fan-light, reached by circular steps that opened directly on to the road; the lower windows were shuttered, a bright light showed in those of the second storey. The attention of the little party was attracted to this house because loud music and voices were coming from it, and, as they passed, the door was flung open and two men came out, shouting and pulling at one another's collars. The soldiers moved forward and at the same time a woman hurried out of the house and spoke sharply to the disputants, who returned quickly through the door where the woman stood for a second, the light of the hall full on her pretty, flushed and sensual face that was set off by a little veil with silver stars tied under her chin.

Her alert, bold eyes defied the soldiers, then glanced at the young traveller; she shut the door.

"That's a bad house, sir," said the corporal as they went on their way; "kept by a man who calls himself Baron Weber. Gambling goes on there and worse things. It'll be shut up soon."

The episode had been over in a moment or so, and the young man had appeared to take no notice of it, though he had stared for a second, with his wild look, at the fair, luscious woman, who had appeared so abruptly out of the murk and who had, before she disappeared into it again, made a quick gesture that might have been a beckoning one.

At the corner of the shoe market, by a little alley where there was a cobbler's shop, the traveller hesitated and put his hand to his brow as if he had changed his mind or forgotten his destination.

On Scharre's asking him where he wished to go, he said that he thought he would, after all, return to the post-house. It was only a small purchase he had wished to make, and that could wait until he reached Hamburg.

The little party then retraced their steps from the shoe market, round the angle of The Three Crowns, across the market-square diagonally, by the Town Hall, down the open and then the pine-bordered road to the post-house.

Merrymaking was going on in the tavern that stood opposite, at the other angle of the road; the light from the upper, unshuttered windows fell on the swinging sign of The Great Bear; behind were beer gardens that sloped down to the Steppenitz, a tributary of the Elbe that ran under a bridge on the Berlin road to a mill-race beyond.

The traveller asked about this tavern that was the only house beside the post-station in sight, and Scharre repeated what he had said to the servant that the host's daughters were not ugly and that French soldiers had much frequented the place when they had domination in Prussia.

The little party then re-entered the yard of the post-station. The soldiers were given a silently hostile reception by the Scharres and their servant; it was the first time that a guard had been put over the post-house.

The carriage ordered by the travellers was ready; Elizabeth Scharre stood beside it, gossiping with the post-boy. Herr Bacher countermanded the carriage, which was taken away by the grumbling postilion, and returned to the kitchen where his friend, Herr Bisschop, was still studying his map.

The two Jews had been joined by a third; they were reproaching him with being so late that they had missed the afternoon coach to Hamburg, now they would have to wait until the night mail. The three sat over the stove discussing their affairs; the newcomer was a young, vigorous man in a half-Eastern dress such as the Prussians wore, and Herr Bisschop looked at him very sharply over the top of his map.

In the kitchen the Swiss still sat over the baggage, the soldiers were stationed at the door and the Scharres withdrew into an outhouse where Anton gave his account of the traveller's call at the government house, his purposeless journey up the side street and his return with the escort.

Everything was quiet until about seven o'clock, when Herr Bacher and his friend came into the kitchen and asked Louise Mendel, who was putting some dried beans on the fire for soup, to order the carriage again in about an hour's time; they would like, first, they said, some rest, and they asked if there was a bed or sofa.

Herr Bacher seemed ill and agitated and pressed the servant as to the possibility of obtaining a bed.

The girl said no, only those belonging to the family that were not fit, but in a closet off the tavern room there was a large table on which travellers sometimes rested—"but not people of your quality," she added shyly.

"That will do," he said, and Anton, coming then into the kitchen, the gentleman asked him to go for the carriage, and, upon a grumble that the ostlers and postboys complained about keeping the horses standing about and the work of bringing the carriage up for nothing, the traveller pulled out a long blue silk purse and said:

"I have plenty of money. Everyone shall be fee'd."

Anton and the servant exchanged glances; they could see the gold shining through the meshes of the knitting. With equal carelessness the gentleman, after he had put the purse away, pulled out his watch; this was also gold, and several jewels hung from the seals.

The Swiss, who had risen in his master's presence, now asked if he should take the luggage to the carriage; the answer was—"in an hour or so."

There was a knock at the door; the servant went and came back with a note that she gave to the younger traveller; Herr Bacher was written on the envelope.

"Who brought it?" asked Herr Bisschop, and the girl answered that it was a stout fellow with his hat over his eyes; she added pertly that she supposed it must be from the Governor, "or who would know you are here, sir, unless you are being followed?"

"Of course," replied the traveller, opening the letter with trembling fingers, "it must be so—"

He read the note, crushed it in his hand and threw it on the kitchen fire.

"What I expected," he said to his companion. "The same as in Berlin."

"It is of no importance," smiled the other and left the kitchen.

Herr Bacher then remained by the fire, and taking out a handsome set of tablets scribbled and effaced some words on them.

The young man then followed Louise Mendel to the closet where the table sometimes used for billiards stood; he asked her to fetch his friend and to leave a light. She saw him fold up the sables for a pillow and put the case of pistols ready to his hand, and she noted the beauty of the little weapons as he took them out of the flap pocket of his pantaloons.

In the dining-room the Jews were walking about with the bored fatigue of men tired of waiting in idleness; they had remarked with satisfaction on the presence of the safeguard; they too had valuables, they declared, and the roads were in a bad state. They made casual conversation with the other two travellers.

Herr Bisschop went into the little closet now lit by one small lamp; the other traveller was stretched on the table.

"I will try to sleep," he said.

Speaking for the first time the other asked: "Can you sleep? I cannot."

He was a dark, elegant man, a few years older than his companion and with a cool, alert manner in keen contrast to the agitation betrayed by the other; though he had been silent, save for a few words with the Jews, and inactive since his arrival at the post-station he gave an impression of energy, authority and courage.

"I will stay by you," he said. "You should not have gone to the town without me."

"I took the ostler."

"I trust none of them."

Herr Bacher sighed.

"Hold my hand, and then perhaps I shall sleep."

The other did so and remained seated on the one chair while his companion stretched on the table fell, for a while, into an uneasy sleep; then Herr Bisschop gently disengaged his hand and returned to the tavern dining-room.

An hour passed; the carriage was waiting, the postboys had returned to the stables and the Scharre family took it in turn to mind the horses, finally wearying of this and leaving the animals in charge of Louise Mendel.

"I cannot disturb my friend," said Herr Bisschop dryly. "He has not slept for nights."

Old Scharre then questioned him as to the journey and his nationality.

"I am Dutch," replied Herr Bisschop coolly. "We are merchants."

He then discharged the reckoning while Jacob Scharre remarked that the gentleman spoke excellent German for a foreigner—"but your friend now, I should have thought he was a foreigner."

"You have a good deal of curiosity and a good deal of impertinence for the office of postmaster," replied the traveller coolly.

At nine o'clock he ordered the Swiss to put the baggage in the boot of the coach and then dismissed the soldiers, saying that he and his friend were leaving Rommel and had no need for further protection; his friend was either still asleep in the closet or had left the tavern; no one saw him.

It was a cold night and sleet was falling, but the weather was not severe for the time of year; the lamps in the carriage were lit, the coachman on the box and still the two travellers lingered.

The three Jews slept by the stove and the Scharres sat over the kitchen fire while Louise Mendel helped the Swiss with the luggage. When all the arrangements were made Herr Bacher appeared; his sleep had not refreshed him for he looked pale and disordered; he woke the Jews by calling for pen and paper; when these were brought he scribbled a note, hesitated, then thrust it into the pocket of his pantaloons.

The Swiss fetched the sables from the table in the closet and put them in the carriage where the other gentleman had left his cloak. It seemed as if the long-delayed equipage was about to start at last—the gentlemen had pulled on their peaked, tasselled caps and thick gloves—when Herr Bacher said that he would go to the town and thank Captain Von Alten for sending the guards.

"No need," his friend objected. "Besides, he will probably be at the ball held at The Three Crowns."

But the younger man insisted that he wished to go to find Captain Von Alten.

The Scharres and the post-boys were now becoming exceedingly impatient; it was past nine o'clock and the rain was increasing. The three Jews had come out on to the road to stretch their limbs and to get a little fresh air; they looked curiously at the waiting equipage, then wandered up the road, regardless of the weather and well wrapped in their heavy coats. The Swiss servant got on to the box beside the coachman and Herr Bisschop and his friend packed their sables in the interior of the carriage. Elizabeth Scharre and Louise Mendel stood with lanterns at the door of the post-house. Sounds of music came from behind the closed shutters of The Great Bear opposite.

"I have forgotten my gloves," said the elder of the travellers. He returned to the dining-room and came out again with the gloves in his hand; when he opened the door of the carriage he asked: "Where is my friend?"

No one knew; they thought that the gentleman was in the carriage, but, no, that was empty. He must have alighted by the other door, that on the side of the road towards the tavern; no one had seen him; the two women went up and down waving their lantern, the post-boys, sick of the long delay, shouted.

There was no response.

The three Jews returned, shaking the water from their caftans, said no, they had not seen the traveller.

Herr Bisschop got into the carriage and again began studying his folding map; after half an hour or so he alighted and joined in a thorough search for his friend. The first place he looked in was The Great Bear, but the landlord declared no one had been there.

At this he again countermanded the carriage, feeing the postilions for their trouble and ordering the luggage to be again placed in the hotel.

The night mail to Hamburg then came up, and the three Jews went off in it. Herr Bisschop, with Anton as a guide, then went to The Three Crowns, where the ball was being held, and asked for the commandant, to whom he reported the absence of his friend, who had then been missing about two hours.

Captain Von Alten acted promptly; he ordered the traveller and the servant to come to The Three Crowns and, after closely questioning them, ordered them to remain in custody in a decent apartment with a guard at the door.

Then he sent for the missing man's baggage and opened it; there was nothing but clothes—lavish, expensive—in the valises, no papers of any kind, no clue to the owner's identity; there were several articles of jewellery that bore coats of arms—all the same and quite unknown to the Prussian noble—and the cipher or monogram W.B. These initials were on the linen. Lieutenant Wulf undertook investigations.

Herr Bisschop answered all enquiries civilly; there was little to say save that they were two merchants travelling to Hamburg; he showed his passport—given at the Hague—in perfect order.

The name of the Swiss was Christian Möller; his papers were, too, quite correct; neither of the detained men could throw any light whatever on the disappearance of the third traveller. Anton Scharre suggested that he might have gone to the gambling hell kept by Baron Weber or to The Great Bear, and Herr Bisschop asked for the two sable cloaks that had not been sent with the baggage.

Captain Von Alten at once ordered out a search-party of soldiers. By the time the wet dawn had broken Rommel and the surrounding country had been thoroughly combed, but neither at the gambling hell, nor at The Great Bear nor anywhere else was there any trace of the missing man. One of the sable cloaks had disappeared, too; no one had seen it.

The police then took the matter up. For the next week Rommel was in a state of commotion over this curious episode; then the missing sables were discovered hidden in a barn near the post-house; the girl Mendel and the woman Scharre were arrested for the theft, but Anton Scharre, believed to be an accomplice, could not be found. It was not unusual for him to leave home for weeks or even months.

The Steppenitz that flowed near the town and some lakes in the nearby woods were dragged without result.

No one came forward to make enquiries about the missing man, who seemed to be without family or friends; this, the police thought, seemed very strange in the case of one so obviously wealthy. The civil authorities were also much impressed by Lieutenant Wulf's description of Herr Bacher and his earnest demand for a safeguard. Why? There were, after all, no valuables in the baggage.

Herr Bisschop could throw no light on this or any other mystery connected with his fellow-traveller, who was, he declared, only a chance acquaintance, picked up at Berlin; some dispute arose between the civil and military authorities as to the investigation. The Swiss had no information to offer either; he had been engaged in Vienna a few weeks before and knew nothing of his master. The Scharres spoke of the note, but no one knew who had sent that or what was in it.

Baffled and exasperated the Burgomaster of Rommel at last acceded to the young Dutchman's insistent and rather haughty request backed by the Governor to be allowed to continue on his way. There was no excuse for detaining him; Holland, like Prussia, was at present neutral in the European conflict and there was nothing against Herr Bisschop, who answered all enquiries with suave civility and in excellent German.

A week after his friend's disappearance, therefore, he left Rommel by the mail coach for Hamburg, taking the Swiss with him. The other traveller's luggage was detained by the police; this included the sable cloak lined with purple velvet for the theft of which Louise Mendel and Elizabeth Scharre received each a sentence of six months' imprisonment.

Suspicion pointed to the male Scharres as the accomplices in this crime, and the old man was deprived of his post, leaving with his wife for Westphalia, soon after.

The affair had also attracted the attention of the police to the establishment kept by the man calling himself Baron Weber, and in order to avoid unpleasant notoriety he accepted the Burgomaster's suggestion that he should close his house and depart from Rommel. Soon after the landlord of The Great Bear also left Prussia.

The search for the missing man continued with great thoroughness, but there was no clue to the manner of his fate, nor was anything heard or seen of him again save this:

Six weeks after his disappearance an old woman, Caroline Vischer, was gathering cones at the edge of a pine-wood when she was frightened by a large black dog that barked loudly at her, then ran into the forest.

She was so impressed by this incident that when returning the next day on the same errand she took her grandson with her; the dog did not appear, but on the ground covered with pine-needles lay a pair of grey pantaloons or overalls, quite clean and dry and neatly spread out.

The boy at once thought of the missing traveller of whom all Rommel had been talking and eagerly searched in the pockets of the trousers. He found nothing but a scrap of paper on which were a few lines written in a foreign language.

Hoping for a reward the boy took the overalls to the Burgomaster, who paid him liberally. Lieutenant Wulf and the two soldiers who had acted as guards at the post-station identified the garment as belonging to the missing man; they were of a peculiar fine grey cloth, and the three Germans had particularly noticed the traveller's clothes were costly looking and appeared foreign.

Lieutenant Wulf had indeed preserved a very good recollection of the appearance of Herr Bacher that he had related carefully to Captain Von Alten and to the police.

The piece of paper was eagerly scrutinised; it was written in English and in a delicate script; the Burgomaster could read it easily.

'I am surrounded by dangers and doubt if I shall ever reach home. In the event of my death do not hesitate to marry again. If any harm befalls me it will be the result of the intrigues of the Comte de Véfour.'

That was all; there was neither beginning nor end nor any superscription.

The pantaloons could only have lain a short time on the spot where they were found, for the weather had been wet and the overalls were dry and the paper unspoiled.

The Burgomaster made a neat dossier of the queer case and filed it; he put on foot enquiries into the personalities concerned in it and in particular tried to trace Comte Véfour. But in a country convulsed by war—overrun by enemies, with Vienna in the hands of the French and most of Europe under a military dictator, it proved impossible to pursue enquiries to a satisfactory solution. The Burgomaster was obliged to lock up his dossier and to try to forget an affair as exasperating as it was mysterious; then about three months after the traveller had disappeared, information about him that caused the Prussian Police the greatest possible surprise and alarm, reached Rommel.

TWO foreign ladies and a maid arrived at The Three Crowns, Rommel, and proceeded at once to the first floor, the whole of which had been engaged for them by an advance courier. It was a cold January evening, but a few townspeople lingered about in the hope of seeing the strangers whose arrival had been for long expected and discussed.

There had not been much of interest to reward the loiterers for their patience; the carriage was good, but had been hired in Berlin, as had the coachman and groom; the luggage was ordinary and the two ladies themselves who had passed very quickly into the hotel were dressed in fashionable travelling pelisses and hats no better than the inhabitants of the frontier town had seen often enough before, while the elderly maid was as impersonal as the valises she carried.

The host himself, Herr Kichner, received the ladies with much respect and some disquiet; he had the air of a man braced for an unpleasant experience. It was with reserve that he asked if the apartments—two bedrooms, two closets, a salon and a dining-room—were to the taste of the guests.

The answers were hasty, indifferent, after a mere glance round the large, clean, bare rooms; one lady asked if a gentleman had yet called for them, and the other if this suite was where the balls were held when there was one at the hotel.

Herr Kichner replied precisely, using French, the language employed, with a good deal of fluency, by the ladies.

"Madame, a gentleman came here an hour ago. He is staying at the Dutch Coffee House—near the post-station. He left this note." Herr Kichner presented it and bowed to the other lady. "No, the balls are held on the ground floor, where usually we have the restaurant. Here we have the refreshment and toilette rooms—unless the suite is let."

"Thank you." The lady who had spoken first gave the landlord a direct stare. "You know who we are, of course, and why we are here. We are using common, easy names, Mrs. Day and Mrs. Clark. We travel on Swedish passports and a French laisser-aller, given us by M. de Châteaurenne, the French Ambassador at Berlin. We are under the protection of your police and if you wish to know anything further of us, go, pray, to them, and leave us in peace."

"I have, madame, already understood as much," replied Herr Kichner. He was a heavy man with harsh iron grey hair and whiskers; his manner hardened, and beneath the deference due to his guests was a growing hostility; his small, yellowish eyes turned uneasily to the other lady who, seated on a striped satin settee, was resting her face in her hand in an attitude of fatigue, as she said:

"Pray, when this gentleman arrives, conduct him here at once. He is our escort, and has travelled with us from London. He was detained in Berlin by formalities. It is very difficult for women to travel in time of war, and on such an errand as ours!"

"You have, madame, my most respectful sympathy and that of every citizen of Rommel."

The lady who remained standing replied:

"We must try to discover that for ourselves. Will you serve supper here? At once? Nothing gross or heavy. My companion is not well."

"At once, madame."

"Call me Mrs. Day—remember—and my friend is Mrs. Clark. Another gentleman has been appointed to meet us here—a Herr Leermann. He may arrive to-morrow, the day after, in a month's time—I don't know. He too will stay at the Dutch Coffee House, us know when he calls here."

While the lady was speaking the landlord furtively regarded her and then the weary traveller on the stiff sofa; he was wondering which of the two was the heroine of the drama that had for two years excited and exasperated Rommel and which was the mere friend or companion. He had the impression that both were equally and passionately concerned in the mystery that they had come to investigate; he noticed that there was little difference in age between them and that they were much alike, though she who went under the incognita of Mrs. Clark was no more than pleasing, graceful and attractive while the so-called Mrs. Day was an uncommonly beautiful woman.

As soon as they were alone the sisters took off their bonnets and pelisses with little sighs of fatigue; the elderly maid unstrapped the valises and laid out wraps and slippers, bottles of eau-de-Cologne and smelling salts. The tall windows were shuttered, neither the lavish candles in the sconces, nor the large fire on the hearth could give any air of cheerfulness to the high-ceilinged room with the pale walls and the scant elegant furniture. Mrs. Clark protested that the suite was gloomy and that they did not need so many rooms; Mrs. Day reminded her that they could not have endured the presence of strangers on the same floor.

They spoke no more to one another; in silence they adjusted their toilets, in silence ate the meal sent up. The maid dined also in the suite that she told the waiter she had no intention of leaving while she remained in Rommel.

In silence the ladies had read the note given them by the landlord; Mrs. Day then placed it in a portfolio, full of papers, that she kept locked in one of the valises.

The supper was just removed when the landlord appeared to announce that the Commandant of Rommel, Captain the Graf Von Alten, was below and wished to wait on the ladies.

"Admit him at once," said Mrs. Day, "and the other gentleman, as soon as he comes."

There was an air of melancholy and uneasiness in the trim blank elegance of the hotel room as the Commandant entered. He was acutely conscious of this, and of the fact that it emanated from the intense suppressed nervous emotionalism of the two women, at whom he looked with a similar mingling of curiosity, deference and hostility as that felt by the landlord, while he, like Herr Kichner, had the air of a man braced to confront an unpleasant experience. Yet what he saw was essentially charming; by the fire sat Mrs. Clark, in a graceful, musing attitude. The firelight lay in golden glimmers on her tight-fitting blue silk dress, gave warmth to her violet robe that was high collared and edged with sable, and set off with radiance her brown hair that was swathed round her head in a Grecian style.

She was about twenty-five years of age, delicately formed, small-boned and plump in a comely fashion, her features were precise, her hazel eyes tired and slightly bloodshot. By the exercise of a little trouble and a little coquetry she might have passed for a very pretty woman, but at present she was clouded by sorrow, lassitude and indifference to everything but a painful task and a thwarted passion. Her sister who stood the other side of the hearth, leaning on the low, formal marble mantel-shelf, was about two years younger and her resplendent freshness was scarcely marred by anxiety or fatigue. She was also dressed in the classical style, a long grey silk gown being girdled under her full bosom and a straight overcoat of black satin fastened over it with golden clasps. Her hair was gathered into careless plaits, curls and tresses that formed a coronet for a proudly carried head. She had beauty of line, colour and graceful movement, light grey eyes, dark brows; a slight flattening of the cheek-bones and a mole on the short upper lip, together with an expression of energy and passion, gave her an attraction beyond that of insipidness. The Commandant looked at her twice and steadily, while he gave the lady on the sofa a slight glance only.

"Which is Lady William Bracebridge?" he asked carefully, with a stiff bow.

The seated lady responded.

"I am that unfortunate creature," she said, in a low voice. "I call myself Mrs. Clark. My sister, Miss Lydia Ardress, passes as Mrs. Day."

Heavily and without emotion the Commandant condoled with the speaker, whose position, he admitted, was worse than that of a widow; gravely he assured her of the sympathy of himself, his country, his government, with her and her family, in her terrible distress.

"And I admire, madame, the courage that prompted you to undertake this tedious and dangerous journey."

"I was not able to endure inaction," replied the Englishwoman. "I had the company of my dear sister and of my old nurse, now my maid. Sir Francis Lisle, who was my husband's nearest friend, escorted me. He is staying at another hotel in Rommel."

Captain Von Alten bowed again at the conclusion of this stiff speech; before he could reply, Lydia Ardress spoke, the richness of her voice tempering the severity of her words.

"Pray, sir, leave aside all comments on my sister's frightful position. Before we undertook this journey we promised one another to be entirely practical. We dare not indulge in emotion. We ask all whom we have to meet to help us by being—impersonal—"

She then seated herself beside her sister and asked the Commandant to take a chair. He narrowed his eyes and lips; he was a handsome man of middle age, his features refined by suffering and heavy thoughts; the precision of his braided uniform, his sword, belt and thigh-boots emphasised the sparse masculinity of his figure.

"Very well, madame," he said, slightly raising his deep voice. "I understand that you have come to Rommel to enquire into the disappearance of Lord William Bracebridge in this town, two years ago, exactly, last November."

Miss Ardress inclined her head.

"I can offer you facilities for your search," continued Captain Von Alten. "But I cannot really help you. I believe that your quest is hopeless—you asked for sincerity—here it is. Two years have passed since that night of November 25th 1809—the affair has become world famous and given Rommel, unfortunately, a melancholy celebrity. Governments—police—private detectives have all worked in vain to solve this mystery. Every possible clue has been followed up—every solution considered, tested. Exhaustive searches have been made all over the continent, high rewards offered. I advise resignation."

"You tell us what we know," rebuked Lydia Ardress. "It is true that the case has been gone into most thoroughly and that it remains completely mysterious. But we refuse to lose hope."

"On what grounds?" demanded the Commandant. "I fear that you are misled by the sad delusions of affection, by the excitement—perhaps the fascination—of an obsession."

Rosa Bracebridge rose suddenly.

"What do you think was my husband's fate?"

"It is not for me to give an opinion. I cannot go beyond my duty. I am commanded to assist you in this—to me—hopeless search. What do you wish me to do?"

He turned to Lydia Ardress who seemed to be the spokeswoman, and she answered:

"We are scarcely ready to tell you. We have only just arrived. We want to make close enquiries in Rommel, to learn from you personally all your activities in the case."

"I suppose he might have come into this very room," interrupted Rosa abruptly, staring across the pale, bare chamber.

"He did not come to the ball," replied the Commandant, who had risen from the dainty chair where he had sat stiffly.

"That is not yet proved," said Lydia.

The landlord, still grave, preoccupied, now entered, and held the tall, handsome door open for Sir Francis Lisle, the fourth of the English travellers. He then withdrew, after a narrow look of sympathy at Graf Von Alten.

It was Lydia who made the presentations; Sir Francis was as easy as the Prussian was cold and reserved.

"We deeply value this courtesy, sir," he exclaimed. We had not thought to trouble you until the morning."

"Day or night I am at your service, day or night there is nothing that I can do," replied the Commandant as he viewed the Englishman with a dislike even more pronounced than that he had allowed himself to show towards the women.

"I admit," said Sir Francis, "extraordinary difficulties—but I refuse to be disheartened." He seemed, however, fatigued and to be forcing his air of confidence as he turned to the fire and stood, with a half smile on his face, looking at the others. He was a man of remarkable charm and comeliness, no more than thirty years of age, finely bred, courteous to softness, but with an air of being, if need arose, equal to any circumstances or events; the elaboration of his travelling clothes amounted to foppishness; for all his amiability, he appeared to the sharp scrutiny of the Prussian officer to be a peculiarly offensive example of a rich, haughty, secretly insolent English lord.

Graf Von Alten disliked all of them and particularly the man who was looking at him with cool, handsome tired eyes, and he said, with subdued anger, as he turned towards the door:

"I shall be in my office to-morrow if you have any commands for me. I wish, mesdames, I could have given you a more cordial welcome to Rommel. You will understand, perhaps, how this dreadful affair has galled us all in Prussia—particularly here."

"I do appreciate that," said Sir Francis softly.

Something in his tone made the dull colour creep into the Commandant's smooth shaven cheeks; with rising violence he added:

"There is hardly anyone in Rommel who has not been suspected of murder, kidnapping, espionage, treachery—who knows what vileness? The most odious rumours have been abroad. They are not silenced yet. Indeed your visit has stirred them all up again. The whole town has been as if under a curse ever since the disappearance of Lord William."

"One understands," smiled the Englishman. Either side of him Rosa and Lydia stood in drooping elegance, and, as the Commandant thought, disdain; on the younger woman's face at least was surely mockery.

"The young man's own folly was at the bottom of the trouble," concluded the angry officer as he opened the door. "Why did he, a British Plenipotentiary, travel under a false name? Without an escort or attendants? Dressed so extravagantly? With a false passport? Perhaps if you can answer all these questions you will come a step nearer to solving the mystery."

"We have, possibly, already answered them," said Sir Francis softly. "The ladies are fatigued. I came only to see if they were comfortable. We will leave everything until the morning. Good night, Lydia. Good night, Rosa."

He pressed their hands and turned to join the officer at the door, who, however, stayed him with an abrupt gesture.

"There is something I must deliver to you all." He called sharply down the corridor, and an orderly appeared carrying a magnificent sable cloak edged and faced with violet velvet. "This is the mantle that Lord William was wearing, that the Scharres and the woman Mendel stole. As it was impossible to send anything so costly to England, I have kept it safely."

The soldier placed the sables carefully over the settee; both the women recoiled with a movement that was little less than a shudder; Sir Francis, without comment beyond, "We heard of this," signed the receipt that Graf Von Alten produced.

There was a second's pause; everyone looked at the superb garment that had belonged to the missing man, as if another silent, formidable personality had entered that bare cheerless room.

Then Sir Francis swept up the glossy sables and said, "I will keep these. Good night, my dears."

"Good night, Frank, good night." The feminine voices fell softly with, to the Prussian's ear, an insufferable accent of affected refinement as the door closed on the pale salon.

"Now they will cry a little, and Mrs. Prosser will make tea, then Rosa will fall asleep on Lydia's shoulder and they will sit so, on that hard sofa, until the fire is out," said Sir Francis with his soft smile. The Prussian stared in disgust at this sentimentality, but the other only added, "Oh, don't you see how they suffer? What hardships they have undergone?"

"Suffer? I suppose there have been a great many widows in the last twenty odd years."

"But the circumstances are so atrocious."

The two men went slowly down the wide stairs. Sir Francis trailed the sables that hung carelessly on the frogged sleeve of his travelling coat; the Prussian's dislike of him increased, he noticed jewels on finger and fob, in the folds of the prim, exquisitely laundered cravat, he was exasperated by seeing a sleek, pig-eyed, purple satin snow-jowled English lackey waiting in the hall—so there were five English people for him to cope with. He said harshly as his orderly fell into step behind him:

"Really, you know, your friend must have been too young and inexperienced for his mission. I suppose if his uncle had not been your Prime Minister, he would never have obtained it—see what distress, what scandal, what trouble such folly leads to."

He saluted, without waiting for a reply, and passed out into the wet, cold night. Sir Francis did not look after him; he summoned the landlord, waiting at the foot of the stairs, by a crook of his raised finger.

"The ladies are to receive every attention. You will bring your accounts to me. We may stay several weeks."

The man assented, with forced civility. Sir Francis lingered, looking at him slightly.

"The least inattention may have disagreeable consequences," he added pleasantly.

Then, followed by the silent servant, the Englishman too passed into the rainy street of Rommel.

The little town was full of rumours, suspicions and an eager, furtive curiosity. People walked up and down, past the statue of Roland in the public square, past The Three Crowns and the house in the corner where the Commandant lodged, in the hopes of seeing one of the English travellers whose arrival had caused so much resentment and commotion not only in Rommel but in Prussia.

In every beer-shop, coffee-house, in every parlour and kitchen the mystery was discussed and always with uneasiness as if the speakers feared to find themselves involved in something sinister. Prussia was again virtually under French domination and the system of espionage employed by that government was known to be efficient and unscrupulous, so distrust and dread were sown everywhere and there were few who did not see in every stranger, and even in their own friends or relations, a spy of Napoleon's.

There was a more tangible fear caused by the presence throughout Germany of the detested douaniers montés, French troops heavily armed and well mounted, who under the pretence of inspecting and protecting the customs scoured the country and were believed to be responsible for many outrages, arrests, murders and robberies that had never been brought home to them. Those who lingered in the wet market-place of Rommel on the 30th January 1811, were rewarded by seeing the traveller whom they termed the 'English lord' arrive at The Three Crowns, and, after half an hour, leave the hotel and proceed to the much older, step-gabled house where the Commandant lodged above the rooms that served him as an office; he used this place as the barracks were without the town, inconveniently situated.

The citizens of Rommel marked with envy and spite the handsome clothes of the Englishman, his easy carriage, his soft smile that seemed to place him above the possibility of taking offence, his complete self-assurance that was so deep seated as to be almost imperceptible beneath his charming manners.

"They are insolent, boastful fools, these English," said the Burgomaster, Herr Wendt, who did not disdain to call at The Three Crowns for a glass of punch and to satisfy his curiosity. "They do crazy things, and then a whole country must be upset for years. I suppose, Herr Kichner, these travellers incline to treat us all as if we were murderers, or, at best, paid spies of Napoleon's?"

"Yes," agreed the landlord in a discreetly low voice. "They are very haughty and suspicious. I have not seen the ladies since they arrived last night. The servant, Mrs. Prosser, acts as intermediary with my staff. She speaks a little bad French. The lord is always accompanied by the fellow whom he calls Burton and who is quite unapproachable."

"Well," said Herr Wendt with malicious satisfaction, "I saw him—the lord—going to the Commandant's quarters, but if he really wants to know anything he will have to come to me. After all, it was a police affair and I succeeded in taking it out of the hands of the military."

"What can anyone tell him, Herr Burgomaster? What does anyone in Rommel know of the disappearance of the mad Englishman?"

"What indeed?" Herr Wendt sipped his punch and looked out of the tall window of the parlour at the gigantic statue of Roland, blurred by rain.

Sir Francis Lisle sat opposite the Commandant, who, upright in a stiff chair, had his desk, loaded with files and packages of papers, before him; the Englishman's hand rested on a large green portfolio, bulging with documents.

"I will put, very briefly, the outlines of this extraordinary and mysterious affair," he said.

"I already know them too well."

"Forgive me, I do not think that you have ever heard them as they appear to an Englishman, a friend of Lord William's."

Herr Von Alten was forced to agree; staring at the raindrops sliding down the panes of the tall uncurtained windows, he listened, his stern melancholy face impassive, his finger-tips joined.

"Bracebridge and I were at Eton and Worcester College together. We both chose the diplomatic profession. I went to the Hague, he to Stockholm where I afterwards followed him. He was recalled to London, while I remained in Sweden. He was appointed Envoy Plenipotentiary to Vienna and entrusted with a secret mission to the Emperor Francis, who had just been driven into a new war with France."

"Lord William's uncle is your Premier?"

"Not his uncle, his father's cousin, Lord Clinton, but family influence was, of course, used. Bracebridge was—is—the second son of the Earl of Castledown, an old peerage, but a small fortune. He married Rosa Ardress, daughter of the Bishop of Winchester—brilliant, sensitive, ambitious, my friend wished to play a notable part in defeating the schemes of Napoleon—the appointment to this important, secret mission filled him with great pleasure. He took it up in the spring of 1807."

"How old was he? We have different accounts."

"In his twenty-fifth year. He wrote to me from Pesth, and from Vienna, he had high hopes—it was before Austerlitz—that he would be successful in his mission."

"What was it?"

"My dear Commandant, as you said last night, I cannot go beyond my duty—my instructions. Bracebridge was sanguine—even to the extent of thinking of asking his wife to join him in Vienna when Austerlitz brought him the sharpest chagrin. There was nothing for him to do but to return home. He had a French safe conduct. He was in communication with his family by means of a courier, one Hoffman, who took his letters—and even parcels—to and fro. His last was written from Vienna, shortly before he left the capital. During the entire month of December his family anxiously expected his arrival—every knock on the door raised hope."

"Why this apprehension?" interrupted the Commandant harshly.

"They knew the dangers of Europe in a state of war, they feared the violence, the treachery of the French Government—the length, the perils of the journey. In early January Lord Clinton sent for Lord Castledown and advised him of the disappearance of his son, at Rommel, on the night of Saturday, the 25th of November 1809."

"All this is perfectly well known to me."

"But hardly the distress, the anguish, the dreadful uncertainty in which the family—the friends, and they were many—of this brilliant young man—are involved—have been—since two years ago. His mother refuses to give up hope—his father does not believe that he is dead."

"Hence this romantic resolve on the part of these ladies to explore Europe?"

"Does that resolve appear strange to you? Consider the position—my unhappy friend had been married barely a year—nothing could allay his wife's distress. Her sister, always her affectionate friend, offered to accompany her. This decision was only known to Lady William's parents, to her parents-in-law and to me."

"You had—in the present state of European affairs, after the alliance of Napoleon and the Emperor Francis—the leisure for this knight-errantry?"

Sir Francis was untouched by the taunt.

"I obtained leave of absence from the Stockholm Legation, where I was chargé d'affaires, to investigate this mystery. The British Government is most wishful to see it solved."

"I know, they have offered a reward of a thousand pounds for any information—the like amount, I think, was offered by the Bracebridge family. Surely the fact that neither sum has been claimed should prove to you that your quest is hopeless?" Graf Von Alten dropped his chin into one of his hands, the weariness on his fine face deepened. "Forgive me, but to me—concerned by the state of my country—of Europe—this case seems to me trivial. Thousands of young, brilliant, beloved men have lost their lives since this conflict began. Lady William should resign herself; she has youth—and many advantages."

"Forgive me," replied Sir Francis quietly, "but that sounds like an attempt to hush up the whole affair. Your attitude has from the first been hostile, Captain Von Alten. What! Do you expect the representative of His Britannic Majesty to disappear on his journey from Vienna to Hamburg—in a frontier town where he stops for rest and refreshment, and no hue and cry to be made? A man belonging by birth and marriage to influential families, with French, Austrian and Prussian diplomatic passports?"

"Sir, the hue and cry has already been made. We have had two years of it." The soldier's face and words were stern. "Not only Rommel, but the Kingdom—the Empire—has been combed. Allow me to tell you once more that your friend's own folly is responsible for the tragedy. Remember he travelled without escort or attendants, under an assumed name, and making an ostentatious display of wealth."

Sir Francis picked one word out of these remarks.

"Tragedy? You think that Lord William is dead? Murdered? By French spies or robbers?"

"I think," answered the Commandant stubbornly, "whatever his fate, he brought it on himself."

The Englishman laid his portfolio on the desk.

"We have heard, Captain Von Alten, many contradictory stories of that fatal—as you think it—night. Prussian, French and Austrian papers have all published different accounts. By word of mouth we have heard others. Even if we were convinced that Lord William is dead, we could not endure this uncertainty as to his fate. We want to know how—and why—he died."

"The French Government is helping you?" asked the Commandant with a faint smile.

"They have treated us in an open manner."

"And you put faith in that?"

"I did not say so. Lady William wrote to Napoleon for passports to seek for her husband, desiring that they might be sent to Lord Clinton. But I advised her not to wait, as if they were refused we could not risk going—"

"So eager to persuade a fond woman to undertake a dubious adventure?"

"So eager!" smiled Sir Francis. "As, perhaps, had you been in my place, you would have been. Lady William was reckless of life itself. I obtained passports from the Swedish Minister in London and we sailed to Gothenburg, got into Russia before the French arrived and so through Pomerania to Prussia."

"It is a long way round by the Baltic."

"Our voyage was tedious, but not adventurous. When we arrived in Berlin, we waited on the French Minister. M. de Châteaurenne is, unfortunately, of great influence in Prussia."

"More so than the King," replied the Commandant grimly, "but perhaps we shall soon alter that."

"Doubtless. M. de Châteaurenne was charming. He said that he already had our passports, signed by the Emperor himself. Lady William replied that as she had asked for the passports to be sent to London and had left for the Baltic without anyone save a few members of her own family knowing; it was very surprising to find the passports waiting in Berlin."

"It merely shows that the French spies are better than yours."

"That is precisely what Lady William said, and M. de Châteaurenne admitted it. However, we have our passports, and they will take us all over Europe free of annoyance."

"If you have sufficient money," said Captain Von Alten sharply. "You said that Lord Castledown's means were moderate. He has other children, so, I believe, has Doctor Ardress. Such a search as you propose will cost more than I can calculate."

"I am a wealthy man," said Sir Francis, as if he spoke of quite indifferent matters. "And my government will help meet these expenses."

The table was strewn with papers, maps, plans, sketches, as with rigid impassivity the Prussian explained what he had done to try to find the missing Englishman; this was his narrative that he gave as dryly as possible and that Sir Francis listened to attentively, without comment.

"I was at the ball given at The Three Crowns when a Swiss servant came to look for me. I interviewed him in the hall. He told me that his master was missing, and all the circumstances. I at once acquainted the police. The missing man's property was sequestered, his companion and the Swiss I put into rooms in the hotel with a guard of cuirassiers over them. A fur cloak was missing; the police went in search of this. Our newly organised Town Police, under the orders of the district magistrates, were extremely scrupulous and able. We had been threatened by the French that unless we kept severe order and cleared the roads of vagabonds, deserters and dispersed soldiers, they would send mobile columns of their troops to do so. You may imagine then that we were very alert. Rommel was, and is, excellently policed. The same night that the traveller disappeared, the police searched the post-house, the taverns and all likely places; four magistrates called on me before the ball was over and I told them of the missing cloaks. My lieutenant told me that this traveller had asked for, then sent away, a safeguard. I had to leave Rommel on the Monday morning; when I returned I found that the police had taken a description of the fur cloaks from the Swiss servant—fetching him away from the hotel with beadles. I protested at this infringement of my authority; the Burgomaster, Herr Wendt, took the part of the police. There was a good deal of disputing and justifying of themselves on the part of the civilians. I, a noble, a governor of a frontier town, a soldier, was indignant at the way I was treated by small shopkeepers. On Wednesday, November 29th, the fur cloak was found, concealed in a wood house belonging to the Scharres. These people declared that they thought that the sables belonged to one of the Jews who had stopped at the post-house on the Saturday night and that they were waiting an opportunity to send it to him; the woman Scharre and the servant girl were found guilty of the theft and received a sentence of imprisonment; her son fled. I sent a report of the whole affair to the Supreme Court at Berlin. My government bade me make every effort to find the missing traveller. I charged the magistrate to take these means of searching—all gamekeepers and huntsmen in the surrounding country to have the whole ground tracked by hounds. Experienced people to investigate all ditches and hollows, caves and woods. This was done, without results. I then ordered the river Steppenitz to be let off during two days by the millmaster and the bed searched. The good repute of the town as well as prestige of myself and the police being now at stake, the river-bed, every copse and ditch, every wood and field, was searched with hounds and sticks until the beginning of December. All houses and gardens were also searched. Particular attention was paid to the haunts of the younger Scharre, who had a bad character. Cellars and lofts were inspected, boxes and chests opened, all loose earth turned over. I paid all expenses and offered a reward of ten thalers for the least scrap of information. Meanwhile the other traveller and the Swiss became tired of waiting under guard in The Three Crowns and requested me to give them passports for Berlin, as they had decided not to continue their journey to Hamburg. This I did and they left Rommel on December 10th. In this I acted under instructions from Berlin. There was nothing against them, although they excited the suspicions of the Burgomaster. Six weeks after the disappearance of the traveller a pair of overalls were found by an old woman near the fir wood at Quitzow. In the watch pocket was a scrap of paper. The trousers were dry, the paper clean, and so they must have been placed there shortly before they were discovered, as it had been raining for three weeks previously. The Quitzow fir wood was then searched thoroughly by huntsmen, peasants, hounds and police. I rewarded the zealous inhabitants of Quitzow with a barrel of beer and ten quarts of brandy. Nothing was found. I then received information that the family of the missing man had deposited 500 thalers with the Bankers Schickler, that were to be paid to anyone giving a clue as to the fate of the lost traveller. This reward promise was published all over the country, together with a promise of full pardon for any complicity in any crime. There was no result. At the end of March 1810 a stranger arrived in Rommel and, after interviewing me, gave a sum of 208 thalers to the Burgomaster to satisfy those who had spent money on this search. He obtained a receipt for the satisfaction of the family of the missing man. This is all that I know as to the affair. A year after the disappearance a judicial commission was sent from Berlin to investigate the case, without result. All the documents relating to the disappearance I sent to Berlin, keeping copies."

Sir Francis thanked the Governor, complimenting him on his zeal and accomplishments, well worthy of the post he held as the commandant of a frontier town.

"I will not weary you further now. I will only ask you a few questions that can be very briefly answered. When did you discover the identity of the traveller?"

"Only when the stranger arrived to pay the expenses of the search."

"Yet French, British and German papers had been, since the end of December, full of the disappearance of the English Envoy."

"It was not my business to take any notice of that. The Moniteur and other Napoleonic journals definitely described Lord William as insane and stated that he had committed suicide. I believed nothing until officially informed."

"You allowed the other traveller and the servant to leave Rommel, without investigating their story? You believed that these two men were merchants?"

"It was not my business to enquire into their bona fides; their passports were in order. My government ordered me to allow them to depart."

Sir Francis put together with a careful hand the piles of documents that the Governor had shown him in corroboration of his story, replaced them on the bureau and rose. The rain was still falling, the plain room was close from the fumes of the tiled stove in the corner. Both men looked weary. The Englishman thanked the Prussian, but added in his habitual tone of soft courtesy:

"You realise that your mistakes have made this enquiry very difficult?"

"My mistakes, sir?" The repetition was a challenge. The Governor stood erect before his chair, all his uneasiness, his hostility suddenly unveiled.

"Yes. Your disputes with the civil authorities, your sudden absence from Rommel caused grave delays. You allowed the Swiss servant to go—he has never been traced since. In the same way you permitted the keeper of the gambling house, Weber, the Scharres, the landlord of The Great Bear, the servant girl, all to disappear. The three Jews were not sought for—how impossible, after two years, to find all these people!"

"I am only answerable to my government."

"Doubtless. But this is a matter of international importance."

"Permit me, on my side, one question. Who was the second traveller, who called himself Herr Bisschop?"

"Surely you know that?"

"Perhaps. I want your confirmation."

"He was Baron Kassel, the Austrian diplomat," smiled Sir Francis, "who was sent with Bracebridge as far as Hamburg—by the order of the Emperor Francis."

"Can he tell you nothing?"

"We have his full story, of course; it throws no light on the disappearance of Bracebridge."

The Governor slightly lifted his epauletted shoulders.

"There then, I must leave the matter."

His manner was a dismissal; Sir Francis put his portfolio under his arm, gathered up his beaver and gloves, then asked:

"Could I, for one moment, speak to Lieutenant Wulf, if he is still in Rommel?"

"Certainly." The Governor struck a bell, gave a command to the orderly who appeared, and Lieutenant Wulf was shortly in the room; his Captain explained to him the errand and identity of the stranger and Sir Francis produced from his breast pocket a small purple leather case that he opened. It contained a miniature portrait of a young man wearing a blue velvet coat; the texture of this material, the pure complexion and glossy hair of the youth were rendered with a rich, dainty touch that gave the portrait a romantic bloom and lustre far removed from realism.

"Is this the gentleman who called on you and asked for the safeguard?"

"Yes—there can be no mistake. It is Lord Bracebridge?"

"Lord William Bracebridge, yes."

The Governor glanced curiously at the portrait of the missing man that was, he said, the first likeness of him that he had seen, though a description of the unfortunate traveller had been for nearly two years circulated throughout Prussia. This agreed with the miniature; everyone who had seen the traveller had remarked on his good looks, elegance, his blond colouring and youth.

"When he called here," volunteered Lieutenant Wulf, who now had this account by rote, "he seemed much disordered. He appeared nervous, weary and excited. He wore dark grey trousers, a coat with braid, a tasselled cap and carried a sable coat worth at least 300 thalers. Not that the night was very cold, only wet."

"It is curious," remarked Sir Francis, "what importance seems to be attached to that sable coat and how everyone seems to have remarked it. I should have thought that so near the Baltic furs would have been common enough."

Neither of the soldiers replied to this comment and the Englishman, again thanking them, left the house and turned again into the large square. He was at once conscious of several groups of loiterers, all of whom were furtively observing him; he noticed that a guard of cuirassiers had been placed outside The Three Crowns and a policeman was moving on some knots of idlers who were gazing up at the windows and at the reflection of the fire on the ceiling of the rooms on the first floor of the hotel that was all they could see of the apartments now occupied by the English ladies.

The Englishman felt discouraged, and as if he were surrounded by suspicion, malice and resentment; the whole town had to him a sinister aspect. It seemed to be full of secret enemies, of abominable mysteries, of traps and spies, his task seemed almost hopeless and he dreaded the prospect of the approaching winter; the weather had already broken and soon travelling would be difficult; they should have left England earlier—but the plan had been to start next spring; it was Rosa's impatience that had made them start in the late summer, and the journey had been full of delays.

He glanced up at the stone statue of Roland that rose gigantic and dark above the market-square; even this ancient hero seemed to have an air of menace. Sir Francis smiled at his own fancies; he had often regretted that he was too sensitive for his profession and suffered much, therefore, under his urbane exterior, from melancholies and moods that did not trouble many other men of his position and gifts.

Ignoring the whisperings, the glances, the nudgings on the part of the lingering citizens of Rommel, Sir Francis walked to the residence of the Burgomaster, Herr Wendt.

His servant did not accompany his master; he had been sent off on other business.

After dinner Sir Francis related to Rosa and Lydia what he had done during the day.

"The Governor is hostile. I am convinced that he knows more than he admits. He is intelligent and patriotic, zealous and efficient; he dislikes us very much."

The women did not answer; the confinement to the strange hotel room, the wet day, the oddness of their errand had sapped their spirits. The sight of the soldiers and police before the doors, of the lingering crowds had made them feel that they were in prison, perhaps awaiting some more severe fate. They had written and torn up several letters home; how write when there was nothing, really nothing, to say to those who waited with such desperate anxiety for news?

"The Burgomaster agrees with me," said Sir Francis; "he is inflamed beyond caution against the Governor. I almost brought him to admit that he suspected Von Alten of knowing a great deal. The Burgomaster complains of the Governor's sudden departure—directly after the ball—without going to bed—from Rommel—and of his absence, and then of his protest against the zeal of the police."

"Where did the Governor go?" asked Rosa, with her hand to her aching head.

"The Burgomaster does not know. He complains, too, that the Scharres and the other prisoners were released, under an amnesty, by the Governor, and that he allowed them, and several other people, important to our purpose, to leave Rommel and disappear. The messenger who brought the note cannot be traced."

Lydia spoke; she looked down at her sister's hand that she held tightly in her own.

"What could this Governor do or be? He is a Prussian, a gentleman, a soldier, as they told us in Berlin, of a fine record."

"He might be a French spy. The Prussian Government might even have given him orders—acting under French coercion. King Frederic I and his Ministers are hardly—since Austerlitz—free agents. Their position is nearly as humiliating as that of the Emperor Francis."

"Orders—for what?" Rosa leaned against her sister.

"For the secret removal of William—to some fortress occupied by the French. Von Alten, if he wished, would be able to contrive that. The Burgomaster insists there is a strong rumour in the town that William called on Von Alten before he disappeared, but this the Commandant has always resolutely denied."

"We come back to the first opinion," said Lydia, "that William was seized by the French because of the papers he carried. They could easily have done that."

Though this statement was put in childish words, it had an undefined air of terror and resignation. Lydia added sharply:

"Rosa, don't look so frightened! Did we not promise one another that we would have courage? Frank, have you discovered anything from either the Governor or the Burgomaster that helps us?"

"Nothing. Save a confirmation of my suspicion that the affair was muddled from the first, there was this dispute between the civil and military authorities, the carelessness that allowed so many witnesses to disappear. But that they—the Prussian police—are really efficient and made exhaustive searches—is proved. I saw all the documents. Leermann has not arrived yet?"

"We have heard nothing," said Rosa. She leaned forward into the circle of the firelight. "Frank, I don't like this hotel. It is too large and pretentious—at least, could they take the guards away?"

"There is not another place fit for you," replied Sir Francis. "I do not think that the guards are necessary. I will speak to the Governor about that."

The sense of disquiet increased among the three people; it was Lydia who, with an effort over rising agitation, said:

"What are we going to do?"