RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

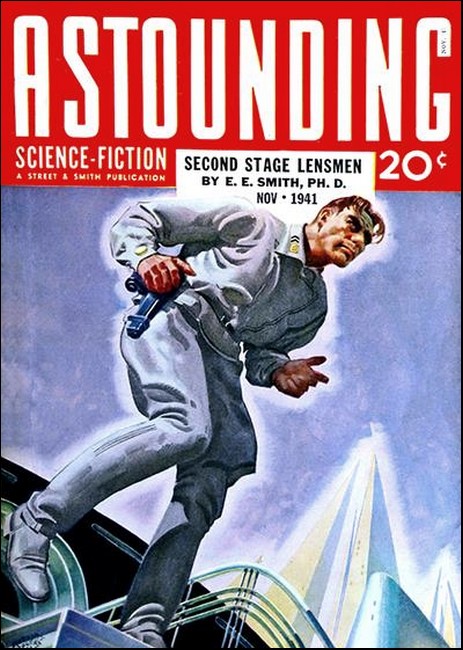

Astounding Science-Fiction, November 1941,

with "You Can't Win"

When a big-time crooked gambler runs up against a space navigator's computation of curves as applied to gambling devices—he can't win!

IT'S tough to be broke on Venus! They never... well, hardly ever... give you a break there. It's always the old army game.

Larry Hoyt was the first to come to. And for a long time he wished he hadn't, for his head ached abominably, his mouth was filled with fuzz that tasted like Eros swamp water, and he knew that those hot pains down in his belly could only come from an injection of concentrated lye. But after a while he ungummed one eye and blearily looked around.

For a minute or so the smoke-filled, dank air revealed nothing; then he saw he was in a flophouse—one of the joints down in the Asiatic quarter. The walls were lined with bunks, and every bunk held an inert form, stentoriously and alcoholically snoring. The soggy floor was paved with other prone forms—last night's sweep-up of the better—or shall we say, less bad—dives. A bartender with a conscience or with some glimmering of pride in the reputation of his house must have, in each case, called in one of the harpies waiting outside and flung him a quarter of a sol to take care of the souse until he woke up again. It was Venus' only concession to decency, but made virtually necessary by the deplorable tendency of men to die when bounced unconscious out into the soup-paved dark alley of the City of Love. The scavenger squad—public health service to you—complained bitterly whenever the night's take of corpses exceeded a hundred.

Hoyt looked, gagged violently, then fell back, weak and jittery. The men in the other bunks were all yellow, red or brown. His pal Jimmy Elkins was not among them. Unless, of course, he was in the bunk underneath; and Hoyt, in his dizzy condition, dared not risk leaning out far enough to look into that. He lay for a little while trying to piece things together, but try as he would, the fog always closed in just as he was about to snatch a scene from the lurid evening before.

Presently an attendant came—an almond-eyed, ocher-faced old man wearing a robe of cheap blue cotton cloth.

"Makee wakeside, huh?" he demanded, prodding Hoyt in the arm. "Oklay, now makee outside. 'Nother man need bunk."

Hoyt groaned and sat up. That time he saw Jimmy Elkins in a far corner of the room, weaving uncertainly on his feet and trying to button up the only buttonable garment left to him—his khaki shorts. Otherwise he was dressed only in a mud-spattered singlet.

"Hey, Jimmy," called Hoyt feebly, "what's the dope? How did we get here?"

"A-a-arh," growled Elkins, "another of your bright ideas. Nothing would do you but we go to the Flying Dragon. The usual thing happened, that's all. You dropped a couple of hundred at the conjunction layout and then balked. So they sicked a couple of cuties on us, and like a damn fool I went with you into the booth. Then—well, blotto. Old stuff."

"Hell," said Hoyt. He had just discovered that his clothes were as incomplete as those of Elkins, and the pants pockets were turned wrong side out.

"Yeah," affirmed Elkins, whose own eyes looked like two fried beets, "and now we gotta get down to the ship—looking like this!"

"We'd better stop off and get a shave first," said Hoyt, rubbing his hand thoughtfully over his quarter-inch beard, "and a raincoat to cover us up with—"

"What with?" snorted Elkins. "We're clean. There's not a sou between us. What's more, the old Clarissa may hop off any minute. God knows what time it is—or day, for that matter. Those Mickey Finns the Dragon dishes out are pretty potent."

Hoyt completed his sketchy dressing in meek silence. Then the pair of them followed the silent Oriental to the door. A moment later they were ankle-deep in Venusburg's slime, trudging along through the scalding drizzle that prevailed three hundred days out of three hundred.

"Nope," said the man at the spaceport gate when they finally reached it. They looked more like studies purloined from a sculptor's studio than men. Wet clay caked them from head to foot. "Your ship—or what you claim was your ship—soared out two days ago. This is Wednesday, you know."

"What!" gasped Hoyt. According to his reckoning, it should have been Monday. "B-but they couldn't. I'm the chief engineer and this is the junior astragator—"

"Was, you mean," snapped the gatekeeper. "These shippers don't monkey around on Venus. You get back on time or else. Get going, you bums, or I'll have you locked up."

"You don't understand," intervened Jimmy Elkins. "The Matilda ought to be landing about now. We can explain everything to the skipper and go back on her; she's of the same line, you know."

"Git!" said the gatekeeper, loosening his blaster in its holster.

THE Company's agents in the Adonis Building were adamant. A rule is a rule, they said. If they started making exceptions, they would never lift another ship off Venus. It was tough, of course, the clerk commiserated, but you have made your bed—now lie in it. Hoyt and Elkins exchanged miserable glances and then slopped their way through the filthy streets to the Terrestrian consulate general.

"Sorry," said the smug messenger, for the two bedraggled specimens were not permitted to enter the office, "but they can't be bothered. If the consul general undertook to help such cases, he'd have no time for serious work. Sober up, get a job, and then pay your own passage home. It's the only way."

"Damn," remarked Hoyt fervently. They had no choice but to turn away, for a swarthy Sikh cop was making unmistakable gestures with the heavy hardwood club he carried. Venus has small time for those who cannot take it.

"Now what?" asked Elkins. "You've always set yourself up as the brains of this pair. What does the master mind produce to get us out of this?"

"Aw, shut up," growled Hoyt, but he led the way out into the rain. At the next corner he turned to the right and plunged down a sloppy ravine that led to the swamp's edge. They slipped, slid and floundered, but they did not stop until they reached the door of the Flying Dragon, now strangely tawdry in the orange light of Venus' daytime. By night it had—or seemed to have—glamour. Now it was unspeakably cheap and shoddy—a dump, in short.

"Just one more bounce," sighed Elkins as the third series of rappings on the barricaded door brought no response. "That leech Rooney wouldn't give you—"

"Well, what is it?" snarled a voice to one side of them. A hard blue eye was regarding them through a peephole. It was the eye of Mugs Rooney, proprietor of the palace of pleasure known to spacemen of the nine planets as the Flying Dragon.

"I want to talk with you, Rooney," said Hoyt, with as much authority as he could put into his voice. It was a ludicrous attempt from such a disreputable figure. Rooney laughed a short, hard laugh.

"Money talks with Rooney," he snarled. "Show me some and you get in, otherwise I'll call the patrol and have you rounded up as vagrants. Five years in the swamps ye'll get for that. We have bums enough on Venus as it is."

The peephole cover began to close.

"Hold it, Rooney, I'm no bum!" shouted Hoyt, thoroughly angry and cold sober now. "I was here the other night with more than five thousand sols, and before I could spend two hundred of it your thieves drugged me and took it away. I want it, or enough of it to get off this damn planet on. And I mean to have it—"

"Or else?" sneered Rooney with one final show of the eye. Then the peephole closed with a vicious snap. Hoyt stood quivering with impotent rage in the hot rain and cursed the man and all his kind.

"You think of brighter and brighter things every hour," commented Elkins caustically. "What did you hope to get by that? If you had been halfway civil, we might have had a shot and a sandwich for a handout. The worst of them will do that—once. At least it would have pulled us through the day."

"Ah, skip it," muttered Hoyt disgustedly.

Then he turned and began the long, slithering climb back up the gully. His anger and disgust were chiefly at himself, for he was too old a spaceman not to know what to expect in a joint like Rooney's. To go, carrying a whole year's pay in his pocket, was no less than rank insanity. Suddenly he sat down in the mud and dropped his face to his hands. Elkins sank helplessly beside him. He was a good kid, in a routine way, but no good in a situation as bad as theirs. Once down on Venus, and a man was out.

"I'm thinking," mumbled Hoyt when Elkins nudged him once and suggested casting about for something to eat.

The enormity of their position was more apparent every moment. Discharged and black-listed by the spaceship company, they could not hope to get out by working their way. It would take money, and lots of it. Moreover, Hoyt was seething with the desire to avenge his damaged ego. For a man of his experience to be put through the wringer like the rawest rooky or greenhorn cadet! It was intolerable. He wanted to make Rooney pay, and pay through the nose. He wanted to run him out of business. He wanted that worse than to get clear of Venus.

"Let's go see Eddie," he said at last, rising and whipping some of the muck off his legs. He had a plan. It was rudimentary, but a plan.

"Eddie?"

"Yes, Eddie Charlton, master mechanic over at the sky yards. We were buddies at school together, and since then I've thrown him lots of repair jobs."

"That 'buddies at school' business wears pretty thin after a few years on Venus," reminded Elkins, his pessimism deepened by the growing gnawing in his stomach, "but let's go. It's our only chance, as I see it."

THEY got their first small break at the gate of the sky yard. The gateman would not let them in, but he sent for Charlton and he came out. One look at the miserable pair told him the whole story, and he shook his head sadly.

"Sorry, Larry," he said, interrupting the other almost as he began. "I know it backward. It happens every month, and there's nothing I can do about it. I only make so much, and I simply cannot carry double. Here's a five-spot for the both of you, and it has to be the last one—"

"Wait, Eddie," implored Hoyt, "you don't understand. I don't want a handout. I want a stake. Enough credit in your shops for a small machine tool job. Do you remember when we studied mechanics and all that stuff about gears and roller bearings and the other parts that went into primitive machinery?"

"Vaguely—under old Professor Tinkham, that was."

"Well, listen—"

Larry Hoyt drew Charlton aside and for fifteen minutes poured forth exposition and impassioned plea. Charlton frowned at first, then nodded from time to time.

"Yes, yes," he agreed, "I see it, but what's the payoff?"

"Rooney will fall for it. It's a gambling gadget, and he'll go nuts over it as soon as it's proved to him that a sucker can't win at it. The beauty of it is that it's strictly on the level."

"I see where Rooney makes a lot of dough, but where do we get off after the manufacturing profit?"

"We won't sell it to him outright—we'll lease it on a royalty basis."

"So you hope to get even with Rooney by making him richer than ever?"

"He won't get as rich as he thinks," said Hoyt cryptically.

Charlton thought it over for a moment. "O.K. You two fellows come in and get cleaned up. You'll look better with those whiskers off and minus a few layers of mud." Hoyt winked solemnly at Jimmy Elkins.

"First we go to the cleaners, then we go back and take Rooney."

"You tried that the other night," said Elkins sourly.

"I wasn't tooled for it then," laughed Hoyt. Despite his mud-incrusted skin, his aching head, and his complaining insides, he was feeling positively good by then.

"THERE she is," said Charlton a bare four weeks later.

They stood in the assembly room of Shop No. 5. Before them sat a huge silvery bowl, breast-high, and some six feet in diameter. It had a small hole in its bottom, leading to a bucketlike catching basin; its cover was a convex glassite dome. Inside the dome was a cunningly contrived two-armed crane capable of manipulation from the outside. Beside the contraption stood many open boxes containing small balls of uniform size, all highly polished, but of obviously different materials. Some were gold, some were copper, some steel. Others were of white ivory, still others of clear crystal.

"Fine," exclaimed Hoyt.

He was a very different-looking man than when he had first entered the plant. He no longer wore the horribly soiled remnants of the blue space officer's uniform, but the trim brown business suit invariably affected by Terrestrial traveling salesmen. Where he had formerly been what was meant to be clean-shaven, he now wore a snappy mustache. Only people who had known him long and intimately would have been likely to recognize him.

"She's true as a die," expatiated Charlton, "a precision job if we ever turned one out. That bottom curve is mathematically correct to within a few wave lengths of light. She's been buffed until the coefficient of friction is so near zero that you can forget about it. The gilhickey on the side is a vacuum pump that keeps the interior completely exhausted. And we topped it off by putting that continuous camera on the side so that you have a photographic record of both the start and finish. It's strictly on the level, and it can't be monkeyed with."

Larry Hoyt examined it again. He smiled approvingly at the inverse curve that formed the bottom. Most people would have taken it for the lower half of an ellipse. He picked up a couple of balls at random and fed them to the clutching fingers of the small extensible cranes through the air-lock slots available for the purpose. He worked the crane, placing them at random, and let them drop. They rolled down the incline and toward the hole in the bottom. There was a single gentle bong as they hit the concealed bell below.

"Fair enough," said Hoyt. "Load her on a tractor and start her down. I'll go ahead to the Flying Dragon in a rick."

"Good luck to you," wished Charlton with hearty sincerity. "That little job stands us three thousand sols. If your scheme doesn't jell, my head's in the bucket along with yours. We may go to the swamps together."

"Not a chance," laughed Hoyt, and picked up his professional-looking sales kit.

In it were elaborate plates of the equipment that was about to follow him to Rooney's place. Not only that, but he had taken the precaution to have business cards printed, styling himself "Mr. Hoyt, Interplanetary Representative of the Tellurian Novelty Co."

A half-hour later he was seated in the inner den of the notorious Mugs Rooney, face to face with that slippery gentleman himself. Rooney was studying a placard placed before him. His gorillalike eyebrows were puckered into a scowl, and he chewed his stumpy black cigar viciously. The placard was headed with heavy, bold face type. It read:

YOU CAN'T WIN!

Positively no magnets or house interference—

you do everything—you pick the balls—

you place them—you start them off—you

say which one is running for the house and

which for you—you judge the finish.

YOUR BALL CAN'T WIN!

Ten sols a throw— try your skill and judgment.

A no-limit game by special arrangement.

Come on!

If you insist on being a sucker—

here's your game.

Because

YOU CAN'T WIN!

"It don't make sense," growled Mugs Rooney, shaking his head dubiously. "It's bum psychology. Why should I clutter up my floor with a machine nobody'll play when I've got to make every square foot pay, what with protection and all? Sure, they're suckers, but where's the percentage in reminding 'em?"

"Did you ever figure how many dimes people feed into the pin games?" countered Hoyt. "And what do they win? Practically nothing. But they keep coming back. Because they hope they will do better next time. It's like that."

"Nope," said Rooney with an air of finality. "Now if you could rig it so that a sucker could win once in a while—"

"That would spoil the whole appeal," said Hoyt. He jerked his chair closer and assumed the air he so often watched in action in the dining saloons of the great Interplanetary liners. "Now, Mr. Rooney, my company is favoring you with a rare opportunity. The machine I am bringing here is the only one of its kind in existence. You will have exclusive rights. We admit that after a while the novelty will wear oil and the customers will stop playing it, but it will be at least a year before the news gets around. For that reason we are not proposing to sell it to you, but lease it. You give us fifty percent of your winnings and you keep the rest. As soon as the take falls below a certain amount we remove the machine. Isn't that fair?"

Rooney scowled some more.

"What about the losses?"

Larry Hoyt smiled indulgently.

"How can there be losses? You don't bet you can win—you simply bet the sucker that he can't win. On this machine nobody wins. It's always a tie."

"Can't see it," grunted Mugs Rooney, rising.

"It's on the way," insisted Hoyt. "Here's a counter proposition. Let me install it and operate it for three nights. I'll pay you a flat floor rental of a grand a night, banking the game myself. You take over any time you sign the contract."

"Have you got the thousand?" asked Rooney, brightening.

Hoyt dragged it out. It was the last of the stake Charlton had advanced him, less a ten-spot just to cover incidentals. It left him a skinny margin with which to bank a fast gambling game, but he thought it would be enough.

"Bring her in and set her up," said Rooney, pocketing the grand note.

He clapped his hands for the bartender.

"A coupla slugs, Al, for the gent and me. The private stock, you know."

THE Ball-Race was the attraction of the evening. After all, a ten-spot was regarded as chicken feed in the Flying Dragon. Human curiosity being what it is, man after man came up and looked at the machine and wondered why it was unbeatable. So he took a chance. And having taken a chance, he took four or five or ten more. And some very persistent and optimistic drunks took twenty to a hundred.

A typical example was the spare, gray-haired old man who kept strictly sober the whole evening. He seemed to be a student of systems, for he carried notebooks with him and jotted down the play of the machines. For a long time he had been recording the outcome of the Conjunction game—that futuristic offspring of roulette—where nine circles, representing the planets, wheeled at varying speeds and were brought to a halt by chance. The game paid high odds for exact conjunctions, oppositions, quadratures and quincuxes, depending upon the number of planets so related, and lesser odds on approximations within ten degrees. But when he saw the "You can't win," sign he abandoned that table and came over to it.

He watched the game a while, then selected a pair of balls. One was of Venusian mock-ivory, as light as pith; the other of platinum, heavy and compact. He planked down his ten-spot and fed the balls into the machine. The heavier he placed, using the delicate little cranes, at the very top edge of the bowl; the lighter about an inch from the central hole. He released them simultaneously. The heavy ball dropped swiftly, almost straight down, and gained velocity as it sped across the steadily but more slowly declining path. The lighter ball stood almost stationary at the start; then, beginning to move, it rolled lazily toward the hole. The heavier ball caught up with it at the very lip, and they dropped through with a single "Bong!"

"Player fails to win," chanted the croupier in his monotonous tones. "He chose the lighter one."

The old man frowned and coughed up another fee. This time he interchanged the balls. The result was identical. He tried two platinum balls, discarding the ivory one. It made no difference. He tried a platinum and a copper one, each placed at an equal height, halfway up the slope. The result was the same.

"It can't be," he muttered, and dug down into his wallet for more funds.

He spent one hundred and eighty sols before he gave it up, baffled. No matter what the initial starting point, or of what material the balls, they always reached the hole at the same instant and fell upon the bell below with a single "Bong!"

So it went. The more they were stumped, the harder they tried.

"Here's your thousand for tomorrow night," said Hoyt as the last jaded player staggered from the room. It was a one-grand note he had peeled off from the outside of his roll.

"To hell with it!" said Mugs Rooney, "I'm not interested in chicken feed. Here's your contract. I'll take over. You've got something there, brother."

"I thought so," chuckled Hoyt.

That morning he paid his shipyard bill in full. Then he went out and hired an auditor—a man to stand by the machine each night and count the take. Every dawn that man collected the Hoyt half, deducted his own commission, and delivered it.

By the end of the week, Hoyt was not only out of debt, but positively rich. That was when he went into a second huddle with Charlton, and he did not miss having a few words in private with Jimmy Elkins, who he had been supporting in the interim.

"I don't see it, but I can make 'em," was what Charlton said.

"You're a damn fool, but it's your money," was the Elkins response.

All the reply Larry Hoyt made was a wide and cheerful grin.

IT was a night after that Hoyt and Elkins showed up in the Flying Dragon. Hoyt had shaved off his dapper mustache and was once more dressed in the standard blue of a spaceship engineer; Elkins wore the uniform he was accustomed to. Neither had been seen in that make-up since the night of their original downfall; and no one, not even the proprietor, took notice of them. The Venusburg joints were one-shot affairs. They either cleaned you out and wrecked you so that you couldn't come back, or they gave you such a liberal education you rarely ever chose to come back. So they didn't bother to look for old customers at the door.

Both the boys had taken the precaution to stop by the Cupidon bar and have a few, so that they were equipped with an authentic breath appropriated to the time, place and occasion. They affected a slight stagger as they walked.

They each dallied with the Conjunction game awhile, losing several hundred net, despite one brief killing made by Elkins. Then they ambled over to the Ball-Race game, about which were clustered a group of gaping suckers. Hoyt bought a pair of balls and lost. He bought several pair more, with identical results. He quit, apparently disgusted, and the seemingly soused Elkins followed suit. Then Hoyt backed away and reread the sign. It had been amended as he had originally suggested. Tacked to the bottom of the insolent invitation to play was the following addendum:

IF YOU DON'T TRUST THE HOUSE'S BALLS,

BRING YOUR OWN. THERE IS A VENDER JUST

OUTSIDE. WE CHARGE FIFTY SOLS FOR

VERIFYING THEM. THEY MUST BE OF

STANDARD DIAMETER AND WEIGH THE SAME

AS OUR BALLS OF SIMILAR MATERIAL

"Jush-h a minute," slobbered Hoyt, leering at the croupier. "I think I'll try the outside balls. O.K.?"

"Sure," said the croupier, negligently. "But you can't win."

"We... hic... we'll shee," gulped Hoyt, and staggered for the door.

Presently he was back. In the meantime the chief inspector of Venusian police had come in, accompanied by a couple of deputies. They stood in the background, watching.

"Here's a gol' ball—genuine gold," floundered Hoyt, producing one from his left-hand vest pocket. "I'll back it against anything you've got. Pick your own ball."

"Nothing simpler," said the croupier easily, "but we won't take advantage of you. Commissioner, won't you please pick a ball—any ball—and place it anywhere? I call on you to be a witness to the fairness of this game."

"Sure," agreed the commissioner, and he picked a bright-red copper ball and placed it. Hoyt set his at random and released the crane grips.

Everybody in the place gasped. For they had just watched the cashier caliper the ball for diameter, and weigh it on micrometer scales with a standard gold ball of the house in the other pan. They matched to the milligram. Yet Hoyt's ball had lost! That time, for the first time in the local knowledge of the game there had been two bongs on the bell—the first when the house's copper ball had hit it, the other when the slower golden ball had struck.

"Think of that," murmured Hoyt, soddenly, "and I thought I had a sure thing."

He retrieved his ball and stuck it back into his vest pocket. Then he pulled out a flask and took a big drag, glaring all the while at the silver bowl that had robbed him of another sixty sols.

"Hey, wait a minute!" he yelled, suddenly, "I've been gypped. I didn't put it in the right spot. I wanna try again—"

"Why, certainly, sir," said the obliging croupier, reaching out for the cash.

"But this time I'm goin' to win—see? Gimme the manager. I wanna shoot the works." He fished out the ball again.

"Just a minute," said the croupier, suddenly hard as nails. "Let's see if that is the same ball."

Hoyt handed him the ball, blindly, and paid no attention while it was being measured and tested. In the meantime Mugs Rooney came up.

"What's the squawk?" he asked, roughly.

"The guy's lost a dime or so. Now he wants the sky for a top."

"Shoot," said the proprietor of the Flying Dragon. Then, sharply to Hoyt, "Where's the dough?"

Larry Hoyt fumbled with his coat, then produced a fat wallet. He slapped it down on the table.

"Never mind counting it," said Rooney, in an off-hand way, with one eye on the police inspector. "We'll do that in the morning when we're making up the deposit. The guy can't win. You know that, don't you, fellow?"

Hoyt cocked a bleary eye.

"Sure, shoot!" he said. The inspector came closer to the table.

Hoyt set the two balls with fumbling hands, then wavered backward and asked Rooney if the house was satisfied.

"Anything's all right," said Rooney, indifferently. "Drop 'em."

IN the moment of pandemonium that followed, Elkins had a chance to lean over and have a few words with Hoyt.

"How? How did you do it?" he asked, in frank bewilderment. "It was the same ball, I'll swear to that. Once it lost, now it won—"

"I had two balls," whispered Hoyt, "but they were up to specifications. They were the identical diameter, weight, and had the same degree of polish. Only they were not homogeneous.

"You see, the contour of the bottom of that bowl is that of an inverted cycloid. That is a curve that has the peculiar property of being a tautochrone—that is, any freely rotating object released at any point on its surface and actuated upon by nothing but gravity, will reach the lowest point in exactly the same time as if released from any other point. That is why a platinum ball and a pith ball take the same time, whether let go from the top or at the very brink of the hole."

"Yes," nodded Elkins, "but once your ball went slower and you lost. This time it went faster and you won. How come?"

Hoyt smiled. People were milling about and Rooney looked flustered. He was busy counting the contents of the wallet under the watchful eye of the police inspector. But there was still a moment to talk.

"They weren't homogeneous balls," explained Hoyt. "The total weight was correct, but the first ball had a hollow center, a platinum shell, and a thin plating of gold outside. The other had a solid core, thin pith around it, plus the same outside plating. See? It's all a matter of inertia."

"Inertia?"

"Yes. The sole force acting on the balls was gravity. It could employ itself one of two ways, or a combination of both. It could either impart translation or rotation. On a dense core ball, the resulting movement is chiefly translation, as there is less leverage consumed in the rotation. On the hollow ball most of the energy went into rolling the ball over, and therefore there was little left available to give it forward speed. Therefore the difference in speed. In homogeneous balls the proportion is the same, whatever the total mass."

"Why, sure. But I wouldn't have thought of that!"

"I figured Rooney wouldn't. I think he is in a jam."

ROONEY was in a jam. He had counted out the contents of the wallet three times and he sat like a fish out of water, gasping helplessly.

"B-b-but I haven't that much," he stammered, "even if I throw the house in."

"You know what we do with welshers in Venusburg," reminded the inspector, sternly.

"Yeah," wailed Mugs Rooney, "but the guy tricked me. Somehow. It's not fair."

"Too bad," remarked the inspector, signaling one of his assistants to produce the irons. "Every man has his turn—you've had plenty. Read the sign up there—"

Rooney, feeling the grip of steel on his wrists for the first time, turned and gazed at his own sign. It said starkly:

YOU CAN'T WIN!

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.