RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

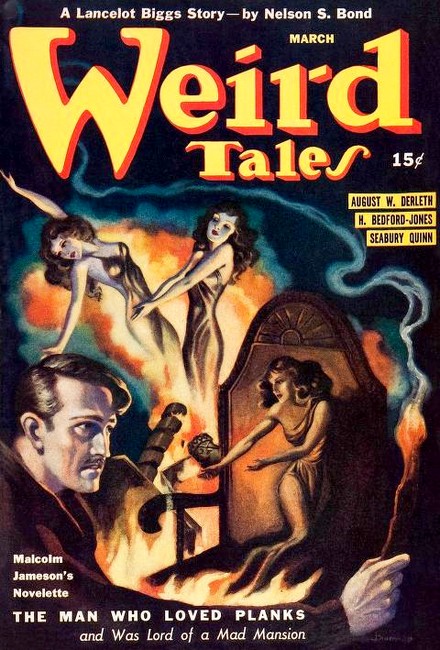

Weird Tales, March 1941, January 1944,

with "The Man Who Loved Planks"

Many of them had lived for hundreds of years in unbelievable agony—

a hand in one city, a foot in another, the head on a different continent.

THE Lord of Mad Mansion was dead!

"Yes," reaffirmed the wizened little doctor from Milburn, "dead as a doornail. I found him lying in the great hall of his house on a pile of old lumber, his arms full of oak boards. What a house! We should have committed him long ago, for surely if there was ever a madman—"

Words failed the village practitioner.

He took off his glasses and wiped them, shaking his head dismally all the time. Then he peeped at his watch. I knew he would be with me for some time yet, as he had just then sent for the coroner. And I knew, moreover, that all I had to do was listen, for the estimable doctor had not been awarded the title of village gossip for nothing.

"Madman?" I queried, stepping back from the easel and eyeing the work I had in hand. I was trying to complete a painting of the giant elm that stood just west of the gatekeeper's lodge I was using as a studio. "An eccentric, I should say, but hardly mad."

The doctor snorted. I laid on another brushful of color, for now I knew I must bring my work to a swift completion. Within a few hours the hitherto sequestered estate would be overrun with curious morbid crowds. There would be police and lawyers—and, of course, Ada Warren, the acid-faced spinster sister and heir presumptive of Mad Mansion. Ada could be counted upon to evict me at once, if only on account of her hatred for Kendall—Enoch Warren's sole friend and adviser. For it was from him and not from the recluse of the Mansion that I had received the privilege of tenancy.

"Eccentric, eh!" said the doctor presently, with a nasty, barklike little laugh. "You should see the inside of that house! Not a stick of furniture in it. No, sir! Not a bed, nor a chair or even a stool. The old man slept, apparently, on a pair of blankets thrown down on the tiled floor of the great hall. He was a maniac, I tell you. Imagine a man of his wealth living in such a fashion. No furniture!"

"That is odd," I commented, "two vanfuls of it went through the gates only last week. I peeked into one and saw many beautiful pieces—"

"That's just it," exclaimed the doctor, "that is why I say he was mad. He bought that furniture for the pleasure of breaking it up! Antiques, they were—all of them. Some even came from great museums. Do you wonder that his sister Ada tried to stop him from squandering his millions in that way?"

"It has always been my opinion," I said, as dryly as I could, "that what use a man made of the money he had made himself was his own business. I never talked with Enoch Warren but once, but I have often watched him rambling through the trees here. He struck me as extraordinarily mild and gentle, very fond of trees and nature. It is true that he forbade me to approach within five hundred yards of the mansion itself, but that again was his privilege. A man has a right to privacy, and if he chooses to make a hermit of himself—well, what of it?"

"Bah!" cried out the doctor. "You are talking nonsense! No one has unlimited right to destroy property, and no sane man would shut himself off from all society. And what of the consequences to others? The destruction of his mills threw thousands of men out of employment!"

The doctor glared at me, as if daring me to answer that. I shrugged and went on painting. There were too many aspects of the Warren case that baffled me as well. The difference was that the doctor was indignant and steamed up over it, while I was not. I shared old Enoch Warren's love of trees. That is why I paint them exclusively. It was that common love, indeed, that made it possible for me to break into that otherwise inhospitable estate. And it was for that reason that I chose to regard him as an eccentric rather than a lunatic.

"You recall that, of course?" snapped the doctor, looking at me sharply. "That was the beginning—eight years ago. Just a year after Mrs. Warren's death, when old Enoch came back here to live."

Yes, I remembered the story vaguely. I knew that Enoch Warren had built his ornate, castle-like mansion back in the nineties and had installed his empty-headed, baby doll wife in it. And I had heard that later they became estranged and he made it a point to be away on business most of the time. After her death he came home once—ostensibly to check the inventory of the great house's contents before putting them on the auction block.

I recalled that the flighty Mrs. Warren had gone in heavily for priceless antiques in her desire to climb into the Four Hundred, and that it was these items that had brought Warren back East. A million dollars was not a sum to leave to hirelings to collect. The matter of the inventory was something the shrewd captain of industry wanted to look into himself.

"He spent one night here, they tell me," I remarked, to show my interest, "stating he would return west the following day. Only he didn't—he has stayed here ever since."

"Exactly," replied the doctor. "And that was the night he lost his mind. Until then he was a normal, highly successful business man. Every queer thing he has done has been since."

"Yes, go on," I said, squeezing another tube of white onto my palette.

"It was two weeks after that that the museum scandal occurred. Of course, a man of his wealth and prominence could get a thing like that hushed up—"

"He must have," I said, "since I have never heard of it."

"Perhaps not. But there were ugly rumors at the time. In fact, there are still plenty of people anxious to dig up these grounds to find the remainder of that young woman he was supposed to have killed and dismembered."

"Now you do surprise me," I admitted. "I would not think Enoch Warren capable of killing anything."

"He was found," said the doctor, very impressively, "in the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum with the freshly severed arm and hand of a young woman hidden under his coat. A guard swore he had seen him inside the ropes of one of the exhibits stroking a dining table with that arm! They detained him there for awhile, in the curator's office, but in the end they let him go. It is worth noting there, I think, that a little later the museum sold him the particular table involved at a very, very fancy price."

"Meaning he bribed them?"

The doctor laughed deprecatingly. "What else is there to think?"

I kept on painting.

"It was the last time he ever left these grounds," the doctor went on, "except for the day he astonished the executives of his vast chain of lumber mills and yards by descending upon them in the New York offices. That was the day he extinguished his company."

"I do remember that," I said.

The whole world does. On that day Enoch Warren ordered every sawmill he owned demolished and all his existing stocks of lumber burned. Likewise he deeded to the government thousands of acres of standing timber to be reserved forever as national parks.

"Then," cried the doctor, triumphantly, as if he had abundantly proved his point, "after settling a paltry quarter of a million on his sister Ada, he hires this creature Kendall to spend the other millions he owned in the buying of antiques! What more do you want to prove the man is mad?"

I could see in that outburst how the man's small-town mind was tainted with the venom of unsatisfied curiosity. Milburn folk loved to know in detail what their neighbor was doing. For a number of years not one of them had been allowed within the grounds of Mad Mansion, let alone into the house. The first of those privileges had been extended to me and, I should say, sundry truck drivers who each month brought more loads of furniture. But entry into the great house itself was forbidden to all save Kendall, the world renowned expert on wood grains and textures.

"I am afraid," I said quietly, "that you have not proved your case. Enoch Warren worked hard for many years to keep a vain, frivolous, society-struck woman furnished with the funds she needed to further her ambitions. She died and the necessity for his work was at an end. He chose to retire and devote himself to a hobby. I see nothing insane about it."

"What!" fairly yelled the little doctor. "Don't forget that when other men retire they sell their property, they don't destroy it. Then there is the matter of the woman's arm—"

"Pah! That is in the class with werewolf yarns," I exclaimed, not troubling to conceal my disgust. The town doctor's chatter was beginning to pall on me, built as it was on one part fact, three parts rumor, and the rest sheer surmise.

He jumped to his feet, fairly quivering with anger.

"Oh, so you think this fellow Kendall's on the level, then? You think that all that money went for real antiques? Well, just wait until you have seen the house. That's all. Just see the house!"

He bustled about the room in a great state of agitation, muttering. It was a case of outraged virtue or something, for in a moment he added a bit to his other information that I had not even guessed before and had no inkling of what it meant.

"I happen to know," he sneered, "what is in Enoch Warren's will. Ada is cut off, and so is Lionel, his nephew. Arthur Kendall is to get everything—this estate, the house, what money is left, and the antiques! Hah! Where are the antiques? Do you suppose that a man as shrewd as Kendall would have sent real antiques up here for that old man to chop up with an axe even if he had really bought them as the newspapers report? Not a chance! And the money! 'To carry on my work, which only the said Arthur Kendall understands' is the way the will reads. His work, the doddering old fool!"

THE little doctor stopped, bristling with emotion. I do not know what else he might have said, for just then there was a chorus of honking horns outside. I opened the door and peered out. It was a car containing the coroner and some others, also a flanking squadron of State Police on motorcycles. I could not miss seeing the long caravan of miscellaneous other cars banked in the road behind them. Those were packed with villagers, intent on satisfying the curiosity that had been balked so long. Reluctantly I took down the heavy ring of keys and went to open the gate.

Enoch Warren, the Lord of Mad Mansion, was dead! My own anomalous position as half guest, half employee would shortly be ended. No longer could I expect to roam the wonderful groves of the quiet estate, secure in the knowledge that I would encounter no one unless it was Warren himself, striding through the woods with his handsome gray mane flying to the breeze, patting and talking to his fine trees as if they were human. Nor could I shut the world out by simply pointing to the sign above the gate that read, "NO ADMITTANCE ON ANY PRETEXT." From now on the law would be in charge, whatever that was.

And I knew, without being told, that Ada Warren would sue to break the will. And that she would win.

I drew the gate open and silently motioned the caravan waiting so noisily outside to come on in. Then I went back into my lodge and locked the door behind me. At the moment I had no thought or desire to follow the prurient crowd into Mad Mansion itself. I thought only of the morbid, sensation-seekers I saw pass in behind the officials. Picks and spades stuck out of their car windows. By now they were doubtless digging in the shrubbery between the glorious trees. They would be looking ghoulishly for the buried fragments of a young woman—one lacking a left arm. Such is the power of wild rumor!

IT was another twenty-four hours before I opened my door again. In that time I had seen many cars pass in and out of the open gates. One had held the sour, frozen-faced Ada Warren with fat, indolent Lionel lounging beside her. With them were crisp, legal looking men, carrying brief-cases. Those, no doubt, were her attorneys.

I saw Arthur Kendall come in, alone and bearing the expression of a man in intense agony. He stayed a long while, but when he drove out he did not stop to speak with me as I hoped he might. Later, after the undertaker had come and gone, there were more police to arrive, and to my immense relief they cleared the grounds of the souvenir hunters and set their own watch on the gate. Their captain knocked at my door and wanted to know if they might make coffee on my stove and I said yes. After that I was left to myself.

Interested only in my art and caring nothing for idle gossip, I had never concerned myself in the least with the various legends concerning the Lord of Mad Mansion, as the neighboring country folk had come to call Enoch Warren. Evidently he had seen some of my work somewhere, for he sent Kendall to arrange for my coming to the estate to paint several of his best trees.

The arrangement was that I was to have the use of the gate lodge and the run of the groves, but must not go near the house.

ONE day Enoch Warren came up behind me as I was sketching and stood looking over my shoulder. Eventually he said: "You have some understanding of them, don't you?"

"I hope so," I replied.

"Do they ever talk to you?" he wanted to know.

"I am not quite that poetic," I laughed. But I realized at once I had said the wrong thing, for he stalked off as if offended. Later, however, he sent Kendall to me with carefully-drawn sketches of two magnificent trees and commissioned me to make full color paintings of them. They were not trees that I knew, though I think I know all the finer ones in the dozen nearest states.

Later. Kendall returned to criticize the canvases, insisting on a number of small changes. He directed me to entitle one "Chryseis," the other "Arethne." Afterward they paid me for the work and hauled the pictures away for framing. I had not seen them since.

On the day following my interview with Milburn's little doctor, I was astonished to hear a fresh commotion at the gate. I looked out to see two large farm trucks piled high with slabs of oak bark. A gang of grinning workmen sat on top their curious cargo. The leading driver bore a pass signed by Kendall, requesting me to allow them to enter, and stating that he himself would be along shortly to direct them where to put the bark.

Hardly had the trucks passed through the gate until I was favored by another visit from the garrulous man of medicine. He was as perky and irrepressible as a sparrow, and I could see that he was bubbling over with some new and exceptionally spicy bit of gossip.

"So you think Enoch Warren was sane?" he began, cheerfully, apparently having pardoned me for my coldness of the day before. "Well, we found something besides his will. He left directions for his funeral...."

"Don't sane men ever do that?" I countered. I do not like that doctor.

"Not funerals like the one he wants. He won't have a preacher, nor any kind of Christian service. No, sir! He wants to be buried with a tree's ashes, to the tune of a crazy rigamarole he has all written out. And believe it or not, the tree's name is Arethne! He! He! He!"

"What's so funny about that?" I demanded.

He choked his laughter off with a sputter. "You oughta see the tree! A mess of boards glued together, the nut! And get this—this is a scream—he directs that the funeral shall not be held until Mr. Kendall has had time to suitably clothe Chryseis. Imagine that—'suitably clothe'—that's what the directions say. Now, I ask you—was the man sane?"

"I am a painter, not a psychologist," I replied stiffly. "I wouldn't know."

The doctor looked a bit crestfallen. Then he murmured something about having a string of calls to make down the road and left me. Shortly after that Kendall came.

HE stopped his car before my door and called to me. Always the serious, almost melancholy type, he was habitually a man of few words. He only said, "You may come up to the mansion any time you like—everyone else has poked his nose in, why not you?"

Then he perceived that what he had said was ungracious, and he hastened to add, "I didn't mean that last the way it sounded. I mean I would like at least one person around who has some glimmering of what I have to deal with."

"I'll be up shortly," I promised. And I cannot deny that despite my summary handling of the gossipy doctor, I was consumed with curiosity myself.

The sight of the mansion was a greater shock than I had anticipated. The building in its prime must have been a monstrosity, built as it was in a style of architecture that combined the worst features of Rhenish castles, neo-Norman-Gothic, and U.S. Grant jigsaw. But now the stone building stood hideously naked, its windows closed by rusty, warehouse type iron shutters.

I suddenly remembered that during the wood-burning phase of Enoch Warren's "insanity," he had stripped the building of its ornate porches and blinds and had burned them in one huge bonfire before the door. Some said that he had even gone so far as to rip the floors from throughout the house, so that above the stone and tile of the ground floor there was nothing to be seen but naked joists.

The two bark-laden trucks still stood before the door, but much of their load had already been carried inside. I stepped across the litter-strewn ground to the front door, avoiding as far as possible stepping on the chunks of bark the men had dropped behind them. The door was open and there was the hum of voices deeper within the house, but I did not go farther in than a few steps at first. The sight that greeted me was enough to stop any ordinary man in his tracks.

The light was dim, but in the first immense room in which I found myself I was astonished to see nondescript bundles of boards, planks, sticks and bits of wood of every conceivable length and shape stacked until they almost touched the stark floor joists overhead. In amazement I picked up one of the smaller ones of these bundles and examined it. It was bound with wire and bore a tag. The astounding label read "Phryne, parts of left hip and thigh, fragments of a hand."

I gazed again at the strange assortment of boards that made up the bundle. They were all of oak, hand-polished, evidently fragments of what had been once a piece of fine furniture. Some were flat boards, such as form drawer fronts, others were turned spindles, others were mere splinters. Somehow I felt a queer sense of disgust at the very holding of the scraps of this low-boy or whatever piece it had been, and was aware at a growing sense of resentment at the evidences of wholesale vandalism about me.

For every one of those bundles was similar. Whether composed of oak, walnut, cherry or mahogany, each appeared to be the tied-up fragments of what had been a beautiful product of the cabinetmakers' art. They varied enormously. Some bundles were of rungs and rails of chairs, banister spindles or wide planks such as must have come from desk tops or the side rails of beds. Some were firmly bound with wire or rope, others were no more than segregated piles of loose lumber. But all had been robbed of what incidental hardware they had once possessed, and all showed the common sign of being of selected hardwoods.

Though saddened by the wreckage, a series of dull, heavy thumps such as are made when heavy weights are dropped, reminded me that I still had to find Kendall and see more of the house. The trail of broken bark led me to a door that gave admittance into what must have been a ballroom or banquet hall.

If I had been astonished at the collection of boards in the outer parlor, that was a tame emotion to what I experienced here. In the room were three roughly cylindrical colossi of wood—three amazing aggregations, each from twelve to eighteen feet in length and perhaps six feet in diameter, of odds and ends of boards and planks fastened together. They lay athwart heavy blocks, and the men I had seen on the bark trucks were working on them under the direction of Kendall. They seemed to be rounding out the monstrous things with plastic wood applied from tubs. And as that was done, others were covering the rounded forms with slabs of the imported bark, fastening it on either by glue or by concealed wires.

Kendall wheeled as he heard me enter. Immediately he flashed what was obviously meant to be a friendly smile, but in the brief instant before he recognized me it seemed to me that as he turned, unaware, I had a glimpse into the soul of a man burdened with a responsibility so terrific he knew he could never discharge it. He started to say something to me, but at that instant we heard the sound of a heavy truck crunching to a stop outside. A roughly dressed man appeared in the doorway and calling out, "Three crated pieces for Mr. Warren. Where do you want 'em?"

Kendall's face lit up like that of a condemned man on hearing of his reprieve.

"There"—he pointed to a space within the door, then called back to his bark workers to knock off what they were doing and wait.

I watched with considerable interest as he knocked the crating away and tore the burlap from about the newest acquisitions. Two of them were of oak—a highboy and a wardrobe. The other was an exquisite piece of mahogany, Chippendale, I thought, a sideboard. I glimpsed a fallen tag. It read—Value $53,000. Kendall was running his finger along the grain of the wood, appraisingly, and his troubled frown was gone.

"Just in time," he said to me, across the top of the highboy. "The old man would be happy if he knew. This is mostly Arethne. There is a little more in the wardrobe, too, though that is mostly Chryseis and Melne."

Naturally, his words meant nothing to me. I supposed the terms he employed was common trade jargon of connoisseurs.

He rummaged around in a corner and produced some tools. Without further words, and with reckless disregard of possible injury to the beautiful parts, he attacked the museum piece before him, ripping it apart. As each bit came away, he would scrutinize it carefully, then lay it on one of the several piles about him, or toss it into a corner with other rubbish. In a short time, before my amazed and somewhat indignant eyes, he reduced both the oak pieces to the wooden elements of which they were built.

SETTING two of the workmen to the task of similarly demolishing the mahogany sideboard, he picked up one of his little piles of boards and carried it across the room to where the huge bulk they were encasing in bark lay.

He examined the boards in his hands very carefully, then began a methodical search of the queer aggregation of wood that lay on the blocks. Presently he found what he was looking for and immediately, using glue and a few thin nails, he affixed another board to it. As he went about adding other boards to other spots, I suddenly comprehended what he was doing. The realization of it detracted nothing from the sheer madness of his undertaking, but it did serve to explain the present internal condition of Mad Mansion and the destruction of the antiques. Those huge blocks of assembled wood particles were in reality gigantic, three dimensional super-jigsaw puzzles! Enoch Warren, aided and abetted by Kendall, had been attempting to reconstruct ancient tree boles by piecing together the planks and bits that had originally been hewn from them!

It was staggering. I looked again, and I was right. Not only was the wood the same, but the grain of each component piece fitted exactly with that of its neighbors. What a colossal undertaking! And at the same time, how futile, for of what possible use could it be? But it was clear enough that the celebrated antique collection was hopelessly lost—destroyed in the furtherance of a wasteful and expensive hobby, and it was also evident why Warren had hired Kendall, the expert on wood identification, for his buyer. But why? Why indulge in such a fantastic game? There was hardly any choice. Enoch Warren was more than eccentric; he was insane. Now, even I was convinced of that!

Kendall stood back from his work, the last piece firmly embedded to round out the irregular cylinder that had once been a tree trunk. He signaled his men to go back to their work and complete the barking of the bole. Then, he took the remaining boards and added them in like manner to the other two monstrosities in the room. I could see that the third one was far from complete—it would require many highboys and whatnots to make a tree of it.

Meanwhile, the men had torn the sideboard apart and asked him what to do with its pieces.

"In the far corner," he said, "the bundle marked Xaquiqui." He added, to me, as if explaining, "Mayan—Enoch Warren was delighted to find her. It was his first knowledge that there were such things in the New World. That's why he gave up lumbering. But I can't bother with joining those today, although I do think we'll get a leg out of it."

That cryptic explanation was far more confusing than enlightening. The sideboard very obviously had not one, but foul legs, each of them marvels of beauty in line and detail. But again we were interrupted, this time by the arrival of a crew of house movers. Those he set to work tearing out the wide French windows that pierced the outer wall. From the massive dollies they brought along, I deduced they intended removing the finished tree bole from the room.

THE funeral was held the next day, at dawn. There were not many present. Lionel and Ada Warren were there, glum and angry looking, and several of Warren's old mill employees. The coffin had already been placed in the grave when I got there, but that apparently was a mere preliminary. Supported by heavy iron beams laid athwart the unusually wide grave, the enormous oak log lay, the bole of what in its day must have been the queen of trees. I hardly recognized it as the medley of scrap wood I had seen the day before within the house. Kendall's job of reconstruction had been superbly done. "Suitably clothed" was the injunction in the will.

The two younger Warrens' scowls deepened as an elderly man, one of Warren's former superintendents, began reading in a fine, resonant voice. That was no ordinary funeral, but a pagan rite conceived by Warren himself. The words I heard were of the poetry and beauty of nature, and there was no reference to death—not until the closing words when I was almost startled to hear the familiar phrase "ashes to ashes."

Upon uttering the last sentence, the master of ceremonies mounted the butt of the log and lit a match to it. It must have been saturated with oil, for in a moment it was blazing vigorously from end to end. With a gesture of dismissal to the few present, the man who had conducted the odd ritual walked away. In a few minutes they all had gone but Kendall, who continued to stand there staring moodily at the blazing pyre. I started to leave too, but he called to me to stay.

Neither of us spoke for more than an hour. We simply stood there, fascinated by the surging flames and the smoke that billowed up to drift lazily off to the southeast. Chunks of burning bark broke loose now and then and fell hissing onto the coffin underneath. Later, the rain of ashes and living embers became incessant, and the crackling popping of the burning oak filled the ears.

Kendall plucked my sleeve. His face was grim, as if he had seen some horror and was striving to hold himself together.

"Suttee!" he exclaimed huskily, "do you realize that? Suttee, no less. But she insisted on it. For months he refused, and they quarreled often. Then he promised. And made me promise."

"I am trying to understand all this, Mr. Kendall," I said, "but what you say is a riddle. All I see is the ghastly whim of an eccentric rich enough to indulge himself. The cost of that bonfire to the world, though, is incalculable—think of the art treasures—"

"But think too of the agony—" he burst out, and there was unutterable sorrow and pain in his face. But he stopped and after a moment said very quietly, but with a trace of bitterness, "I'm sorry. I thought you knew, I was hoping you could see. Of all people you are the most likely one—you have studied trees, love them, know their moods—"

He paused, and I noted uncomfortably that his eyes were wet.

"If you could see, I would not have to tell you. Since you do not, there is no use my trying. You would laugh and call me insane, like those fools did Enoch Warren. You saw Ada Warren glaring at me today, and you may know that she is bringing suit to prevent my getting the money. Undue influence, they claim! Yes, there was influence all right, strong influence. The strongest of all—great love. Arethne it was, though, not I; and there she goes—with him."

After that outburst, he lapsed into bitter silence. We sat, finally on the turf, spellbound by the pyre. At last, with a sharp crackling and a groan, the huge log broke in the middle and its sagging ends slid into the grave itself. A great shower of sparks scurried upward, wheeling and twinkling in the pall of smoke overhead. The grave, deep and wide though it was, was full to the brim with smoking ashes, symbolic of something I had not yet guessed. Seeing Kendall still submerged in his own dark thoughts, I quietly slipped away and left him alone with his grief.

THE acrid contest over the will was drawing to a close. Avid sensation seekers greedily read every word as Enoch Warren's eccentricities were exposed in the press. Souvenir hunters infested the estate, despite the police guard. At Kendall's request, I kept an eye on the shuttered mansion, for the court proceedings kept him in town much of the time. He seemed to fear that people might break in to carry away the precious rubbish left behind by Enoch Warren, and intrusted me with the key so I could look in from time to time to see that the remaining two synthetic logs were unmolested.

One evening late, I had gone to the top of the hill to watch the full moon rise, and thinking I heard sounds within the house, I let myself in. It was quite dark in there, except in the banquet hall. Through its east windows a flood of moonlight made everything clearly visible. The two oak logs were still where I saw them last, but in the place of the one called Arethne there was something else. It was only a beginning, as many loose boards lay scattered about the glued-up core, evidently handy to be fitted and cemented to the rest.

That, I observed, judging by the darkness of the wood, was to be a mahogany log. In an inner corner stood the iron bedstead Warren had used. Kendall must have moved it there to sleep on the nights he stayed in the house.

I sat down on it, and being drowsy and the bed a comfortable one, I was soon stretched out, staring at the ceiling and thinking about Warren's bizarre hobby and the colossal impudence of it. What astonished me most was Kendall's obvious intention of carrying it on. One would have thought that the death of Enoch Warren would have released him and that he would then abandon the silly business and go back to his former occupation.

I may have slept, but presently, for no readily apparent reason, I suddenly became aware that my heart was pounding and my breath coming in heavy pants; goose-flesh tingled on my arms and legs. I sat up, startled, then knew that someone was in the room with me. There was a vague but exotically delicious perfume, and I sensed rather than heard a low breathing. Abruptly, as if materialized on the instant out of the air itself, a beautiful girl stood beside my bed, not a foot away. She was gazing at me as if in earnest entreaty. Then, suddenly, she sat down on the edge of the bed beside me and began caressing my forehead with her tiny hands.

I did not move nor speak, nor did she utter a sound at first. But in a little while she began talking soothingly in a strangely whispering language. It was suggestive of the susurrus of high branches lightly tossed by a June breeze. Compelled to guess at her meaning from her tone, I assumed she was reassuring me as to her reality, despite her inexplicable apparition. But I did not need that. Tender and fairy-like though her fluttering touch was, it was real; she was no phantom.

Yet despite the calmness with which I submitted to her ministrations, a vague horror—not of her, but of something that affected her—grew on me. I looked at her more closely, straining my eyes in the pale, soft moonlight, and then I knew. She was covered with scars, she must have been hideously slashed at some time. Thin lines they were, almost hair lines, most of them, that covered her otherwise white and shapely body. One, heavier than the others, ran diagonally across her torso, from armpit to hip, as if she had been sawn in half and rudely sewn back together again. Then I observed that an ear was missing—that the outer curve of the thigh was gone, as if sliced away—and there were many minor scars lining her arms, face and hands. All those details I could see quite clearly, once I looked, for of clothing she had not a shred.

MY emotions by then were tender ones, but mingled with them was an upsurging of hot indignation, growing into anger as I contemplated her cruel wounds. It was then that I recalled with some difficulty a little of what Kendall had said to me. His hitherto esoteric utterances had been so far away from sense that I had actually forgotten.

"Chryseis?" I hazarded, speaking softly. Like a delighted child she clapped her hands and laughed, then sprang away from me and went into a graceful dance. Ah, so Chryseis was her name. But he mentioned another, or two—Melne, Arethne?

"Arethne?" I tried, but she ceased dancing and knelt beside me, face pillowed in her arms, and wept bitterly. In a moment she rose and gestured hopelessly toward the area where the funeral log had lain. But when I spoke the name Melne, she brightened again and called out in her queer, delightful language to an unseen person.

On the instant another like her appeared, and for a brief time joined her in her dance. It was a grotesque dance then, for I could not fail to see that the second nymph was not only scarred as was Chryseis, but that she lacked an arm, that part of one leg between mid-thigh and ankle, and a portion of the back of her head. But marred though she was, her mutilations detracted nothing from the wild grace of her pagan beauty, nor did they seem to impair her ability to dance.

As if the self-revelation of these two was a signal, other apparitions—or so I thought them, though they were real as my own self when I touched them—showed themselves in every direction. My first reaction was a gasp of horror at seeing the banquet hall take on the aspect of a charnel house, for wherever I looked there were fragments of dismembered-like creatures. Fingers, slices of arms, legs and torsos, slivers of head, sprouting ears or tresses of wavy hair, lay all about me, suggesting the atrocities of the infamous Nana Sahib at Cawnpore. Yet, on the other hand, they seemed firm and alive, twitching and moving of their own accord.

Strangely, I felt no fear. Somehow I knew that whatever catastrophe had caused the gruesome relics, it was one that had occurred long, long ago. Chryseis and Melne had gone over to where the nucleus of the mahogany log-to-be was, beckoning me to come and look. Beside it were the fragments of a dark-skinned beauty, and while the two nymphs busied themselves picking up the scattered boards about the floor and arranging them in strange juxtapositions, I noticed that the disjointed parts of the dusky one were reorienting themselves. In a moment I could see that there was the greater part of another nymph there, or an Indian Princess, judging by the nobility of the face which gazed at me unblinkingly from lustrous black eyes.

Chryseis returned to me and with vehement gestures toward the helpless one on the floor, addressed me passionately in her pathetic, rustling speech. It was plainly an appeal for my assistance, but of all she said the only word I recognized was "Xaquiqui," evidently the appellation of the one at our feet, or of the mahogany log with which she was associated.

While amazement and sheer incredulity were struggling for the mastery of my emotions, my intellect was vainly trying to function—to postulate some rational explanation of what I beheld. But my mind and soul was unexpectedly relieved of the burden of decision, for there was the sound outside of an automobile grinding to a stop before the door. The creatures before me scurried to their logs, and at the click of the latch vanished as abruptly as they had appeared. I was sitting alone in the vastness of the empty banquet hall staring into the steep shafts of silvery moonlight that struck downward through the windows. Between me and the light were only the fantastic silhouettes of the jigsaw logs.

ARTHUR KENDALL was surprised to find me within the house, no doubt, but his agitation over some other matter was so great that he wasted no time expressing it. All he said was a gruff, "Oh, you here? Please wait outside in the car. There is a private matter I must attend to here."

His voice was so charged with emotion, and his face so haggard and drawn, that I actually felt a sense of indelicacy at looking at him. There was a torment of soul there that an outsider shrank from seeing.

He kept me a long time—more than an hour, it must have been, for the Moon climbed until it reached its zenith. Once I thought I heard a wail from the depths of the mansion—not the wail of anguish of the physically stricken, but the high cry of poignant sorrow such as one might expect from a suddenly bereaved bride, or a fond mother at the foot of her son's gallows.

When Kendall did come, it was with a rush, as a man possessed. He sprang into his seat, stepped viciously on the starter, and whipped the car down the curving drive at a reckless speed. He slowed, though, for the gate, and once we were out on the road he drove more sanely.

"So you saw them, at last?" The form of it was a question, but it was a statement. He sighed heavily and slowed the car to a crawl.

"I'm glad they let you see. Whatever happens hereafter, there will be some strength and consolation in feeling that there is at least one human who understands what Enoch and I were compelled to do. Compelled, yes! How could we know of the long, hopeless sufferings of those dear creatures and not try to help them? Some we could save, or hoped to. For the others—there is always fire."

He stopped the car and looked back toward the mansion, but behind us was only the dark masses of the midnight woods. Presently he started slowly forward again, talking as he drove.

"Enoch Warren saw them first, the night he slept there after his wife's death. He woke with a start, in the middle of the night, feeling something lying on his chest, pluckling at the hem of his blanket. Then that something crawled up across his throat and he felt fingers lightly brushing his jaw and cheek. Just as you would have done, he grabbed at the hand and caught it. It was surprisingly small and light, a woman's hand, and it seemed to come away in his grasp, as if he had pulled it clear off the body that owned it. When he reached up further, with his other hand, to seize the arm that should have been there, there was nothing. Still holding his capture tight, he got up and made a light, and found he was holding the living hand of a severed arm.

"I say living, because the fingers wriggled in his, squeezing his hand. It was perplexing, and you can imagine how he searched the house. Our time is too short to tell you in detail of all those painful and slow first steps he had to take to solve the puzzle of the lonely, living hand. It could beckon as well as squeeze, and it would tap out messages with its fingertips. Patiently he followed its every hint.

"In time he learned that it was identified with the oak desk that stood in his bedroom, one of Mrs. Warren's antique purchases. Then, driven or led by the hand, he found that downstairs there were more parts—some of the upper arm that belonged to his hand, a bit of leg, and some other unidentifiable fragments. These, in turn, appeared to be associated with a piece of furniture, an oak buffet. Experimentally, he wrecked the two pieces of furniture, and sorting out the boards that seemed to match, he joined them together and found that by doing it some of his fleshy fragments correspondingly welded themselves together. But there were some of the body slivers that did not fit at all, and of course there was much missing.

"His wife's records showed that both the oak pieces were Ravenshaws, and he found an offer of a third, which she must have refused to buy on account of the price asked. He at once ordered it, tore it apart, and was rewarded by discovering he had the head to his body—to his delighted eyes she was a lovely blond goddess, no less. He devoted many months to conversing with the head, learning its language. In time he understood enough to hear her story.

"That was Arethne. She was a very ancient tree nymph, hamadryad of a wonderful oak that grew in a grove near Stonehenge, and there had been a time when she was the object of worship of multitudes. In the year 1572, Hugh Ravenshaw cut her tree down and made it into furniture—"

"HOLD on," I objected. "Hamadryads cannot survive their tree. They die with it."

"That," he said, "is a gross error, a mistranslation of the old legends. Tree nymphs survive until the bole has been totally destroyed, whether by rot or fire. You may divide the bole, and the hamadryad with it, but neither ceases to exist, as you yourself have seen.

"But back to Arethne. She was very anxious to be reassembled. She said the agony of being hewn into planks was not so great as you might imagine, but the perpetual distress of being dispersed—a hand in one city, a foot in another, and perhaps the head on another continent—was painful beyond description. It made re-embodiment, or materialization, impracticable, for whenever she attempted it, she only succeeded in frightening the human she tried to appear before. Such efforts on the part of herself, or cousins, are the foundations upon which so many ghost legends are built. After a few decades of such experiences, she quit trying and resigned herself to her miserable doom. The fact that the cabinet work made from her tree was so beautiful and masterfully done made her situation all the worse, for they were carefully preserved. She had abandoned hope even of relief in death."

"But why," I asked, "should a hamadryad want to re-embody herself?"

"Because, although they are the souls of trees, they have the bodies of women. Now that there are no more satyrs, necessarily they must choose their lovers from among us. It is a hard fate for a lovely pagan creature to be dismembered and dispersed so finely, part in a museum there, another in a private collection in another place—in the midst of warm life, not dead, yet not able to partake of it.

"Her early efforts to reveal herself to potential lovers repelled, rather than attracted them. It was not until she met Enoch Warren that she found a human with the sympathetic nature and capacity of mind she yearned for. It was in search of the rest of her that he went to the museum that day, taking her arm with him to help him pick the pieces he must have. You see, by then he was well known in nymphian circles, and other dispersed hamadryads would show their pitiful fragments to him in the hope that he would aid them too. It was very confusing. It is a hard matter to match bits of the same body, especially when they are not adjacent, and it complicates things immeasurably to have to pick them from a jumble of alien parts.

"That is how he came to hire me. I could recognize them in their wooden form and need not expose myself to the embarrassment of being caught as he was, with a human fragment in my possession.

"I hunted Ravenshaws all over this country and Europe, and in the end we recovered most of Arethne's tree, and we fitted it together as you have seen. Once she was complete, she remained embodied most of the time, only withdrawing into the tree when strangers, such as the truckmen, would arrive at the mansion. She took a great interest in the living trees on the estate, and would go out at night and mingle with their nymphs, although she thought them all distinctly of a lower class than the Old World hamadryads. It was largely due to her urging that Enoch burned his sawmills, that and the appearance of Xaquiqui. He did not believe at first that they are everywhere that there are trees.

"You see, in acquiring all that furniture, we had many pieces left over, as craftsmen mix their lumber indiscriminately. In the Ravenshaws we found much lumber from other trees of her own grove—two of them her own cousins, or sisters, hamadryad relationships are too involved for me to wholly understand. Those were Chryseis and Melne. Driven by his own impulse of compassion and by Arethne's pleading, he continued his buying, searching for the remainder of those trees. Soon we had enough to start their reassembly."

"But," I objected again, "wouldn't certain parts be irretrievably lost? The chips and sawdust and so on. And in all these centuries surely some whole boards must have been burned."

"Exactly," he admitted, "and therein lies the tragedy of it. Melne, whom you saw, is as complete as we can make her. It is true that there is a pair of stools in the Vatican made from her trees, but they refuse to sell them. Even if they would, they are unimportant—a pair of fingers, I think. I have searched everywhere—there is no more."

Some time before we had reached the top of the hill that leads down to Milburn, and he had stopped the car and parked at the side of the road, looking from time to time over his shoulder. I was aware of a redness flickering on the windshield, and I turned to look too. Behind there was a ruddy glow lighting the sky, and in another minute a high yellow flame lifted itself above the treetops, licking the smoky clouds. From the direction of Milburn came the sound of pistol shots. Then the clangor of bells, and finally the scream of a siren.

Arthur Kendall put his car in motion. Then, without a word of explanation, drove it crosswise off the road and killed his engine. Doggedly he sat there as the lumbering fire truck chugged up the hill from the village, and when the outraged firemen stopped at his barricade and swore at him he merely fumbled with the switches on the dashboard and pretended to be trying to start a car that would not start. The impatient firemen gathered around and a dozen pairs of arms pushed us literally off the road. Then, with siren screaming, they drove on past to the conflagration behind us. Mad Mansion was in flames.

"It was the only way," said Kendall, with a sob. He was driving furiously now. "We have burned others where there was no hope. So it must be with Chryseis."

"But why? Chryseis is whole—"

"Yesterday," he said grimly, almost biting the words off, "the court set aside the will. Ada and Lionel Warren inherit. Everything."

I still could not see.

"An hour later Ada signed a contract with Seymour and Wrigley. It is that that I cannot bear. Seymour and Wrigley are restorers of antiques. They have photographs of every bit of the original furniture, and they know most of the original component boards are there. All those we have collected there will be scattered again, sold in the open market, to appease Ada's insatiable greed. I did the kind thing—they agreed with me, awhile ago, begged me to set the match."

"You loved Chryseis?"

He nodded. "For two years she has been my wife."

He let me out at Milburn, and drove off blindly into the night.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.