RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

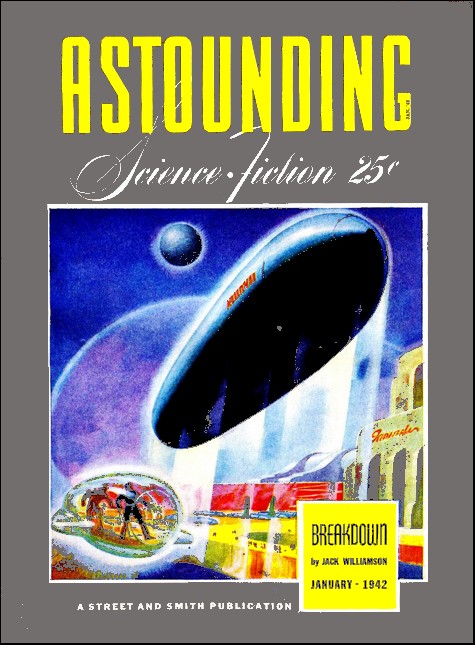

Astounding Science-Fiction, January 1942, with "Soup King"

The ship crashed on Venus, with a gold mine as its landing spot.

Fine for everybody but the cook. But he did better—he fell in the soup!

"WAW! Ga-a-ah! What slop!" roared Buck Reagan, captain of the interplanetary freighter Pelican, and hurled the offending bowl of broth from him. "Where'n hell is that fat slob of a swill-mixer? I'll soup him... I'll rip him into giblets... I'll—"

In the pantry the usually sunny-disposition cook, plump little Jimmy Laird, heard and quailed.

He had tried his best, but his bosses just wouldn't be pleased. And his bosses were everybody else in the ship, according to the age-old tradition that a ship's cook is the lowest form of human life. The chow was bad, he knew that. But it wasn't his fault. How could anybody dish up a palatable meal when all he had to work with were vile-tasting and worse-smelling synthetics? What did they expect but stinking slops when the ingredients were slabs of the malodorous trephainin, flavored with the bitter, belch-inducing vitamoses, reinforced by calorigen tablets, and supplemented by the nauseous compound called proteinax? But whatever the newest bit of hazing Buck Reagan had planned for him, it was never applied. For, while the skipper was still bellowing his displeasure, the mate cut him off with a sharp warning.

"Hold it, chief," shouted Holt. "We've lost the beam."

"What!" blasted the captain. His angry eyes sought the visiscreen, but all that there was to be seen there was shapeless, swirling white mists. The nepholoscopes were just as non-communicative—the readings all around and up and down were the same, one hundred percent. Clouds, clouds, everywhere. Venus was always like that, once you got below the topmost cirrus layers. Without the radio beam from Venusport, the planet's only authorized port of entry, blind landings were impossible. There were too many uncharted mountain ranges. Reagan's finger found the call button to the tube room and jabbed it.

"Up blasts," was the curt order that followed, and they set themselves for the kick of quick acceleration, for they had already braked down to airborne glider speed.

The tubemaster never had time to comply with the order. A shape flashed on the screen—a gray, dripping, cruelly jagged pinnacle of rock trailing wisps of cloud showed for an instant, then vanished. And with its vanishing there was a heavy jar and the scream of rending hull plates. The Pelican caromed off, swerved like a shying horse, then plunged sharply downward. A tube sputtered, tried to fire, and then the ship sideswiped another crag, bounced heavily, only to plunge nose first into something immovable and hard. The lights went out as men were flung about like tenpins. Then for a time there was dead silence broken only by a hissing as the broken ship's internal pressures adapted themselves to the lesser one of Venus' substratosphere.

"Well, at least we're all alive," drawled Holt, as the last man crawled out to join the huddled group shivering in the sleety rain. The deserted wreck of the Pelican sprawled before them, its crumpled nose embedded in a towering cliff and its precious cargo of food pellets for the Venusian colonists spilling out through the ragged wounds in its sides. They could see vaguely through occasional rifts in the misty curtain about them that murderous peaks rose everywhere. What lay in the valleys far below could only be guessed at, for they were buried under a blanket of scurrying clouds driven by the icy highland wind.

"Humph," snorted the captain. Alive, yes. But their ship and cargo were a total loss, and they had little idea where they were. Somewhere, far down in the steaming jungles of the foothills, there might be a trading post or regional smelter, but how far and in what direction they could only guess. Conditions on Venus were most unfavorable to surveying and few maps existed. But Reagan unfolded a sketchy chart and began puzzling over it.

Avrig, the tubemaster, took the opportunity to stroll away. He rounded the broken stern and looked despondently at his smashed tubes. He saw the last of his fuel supply dripping from his gashed bunker tank. And then he walked on to have a look at the ship's other side. It was as bad or worse than the other. Then he stared at the forbidding cliff that had stopped them. In another moment he was yelling madly and bounding back to where his shipmates stood.

"Hey, fellows—come see! I've struck it rich. Gold—tons of it. I'm a multimillionaire—"

"Whadda you mean, you're a multimillionaire?" asked Holt scornfully, "This is a co-operative outfit."

"Yeah," bubbled Avrig, jubilantly, "but the cruise is over—the old Pelican is done for—through. That washes up our agreement. But don't worry, I'll need help to cash in, so you'll all get a good cut—"

There were sullen murmurs among the crew and Holt growled.

"Our agreement says that all profits of the cruise 'however derived' shall be whacked up amongst us—a third to the skipper, a quarter each to you and me, and the rest divided equally among the men. Furthermore, the agreement is in effect until the end of the cruise, which means until we all get back to the port we started from."

"It's mine," insisted Avrig stubbornly, "by right of discovery. I saw it first—"

"I put the ship down here," said the captain coldly.

"Oh, yeah?" remarked Holt. "Or did I? I'm the guy that lost the beam."

They glared at one another. Then Buck Reagan suggested it might be sensible to see whether Avrig had really found anything worth squabbling over. The bedraggled group rounded the battered stern and gazed up at the cliff. It was there, all right, a colossal treasure. A great fault had split the cliff and in the wide fissure masses of quartz were packed, heavily grained with metallic gold and studded with immense nuggets. Jimmy Laird gaped with the rest, but he did not share their elation. For he and he alone of all the ship's company did not share the common agreement. Behind his name on the muster roll were the qualifying words, "landsman for ship's cook, for keep and wages only." There was a moment of stupendous silence as the onlookers made estimates of the wealth before them. Then the captain spoke.

"There we are, boys. It belongs to all of us. Break out those tools in No. 4 and hop to it."

There was a chorus of approving yells and Avrig knew he was beaten. He shrugged and started away with the others.

"Excuse it, please, sir, but could I say a word?" Jimmy Laird had mustered up courage to address the captain otherwise than in frightened response.

"No. You're out of this," was Reagan's curt reply. "Grab a pick and get in there and do something to earn your pay. It's a cinch you're no cook."

"But, sir, the Venusian law—" Jimmy persisted.

"To hell with the Venusian law! With this dough we can grease our way past any law. Get going!" And Reagan emphasized his order with a swift kick.

Jimmy Laird went, crestfallen and wounded in spirit. For, despite his mistreatment, he still bubbled over with good will toward everyone, and he also feared the men of the Pelican were riding for a fall and felt that he should warn them. On a shelf in his galley there reposed a thick gray book entitled "The Revised Statute of the Dominion of Venus" and he had whiled away many of the tedious hours of the long voyage by reading it. Venus, he learned, had a very peculiar economy and therefore a very peculiar system of government and set of regulations. Jimmy Laird was a cook, not a lawyer, but he could read. Reagan's crowd were going about things the wrong way.

He might have swallowed the last insult of the captain if he had not been put in Avrig's gang for the afternoon shift. Avrig was full of rankling disappointment at having to content himself with a quarter share of his Golconda and consequently drove his men hard. And since many of them were as hard-bitten as himself and as likely to take a swing at him as not, he vented most of his irritation on the hapless cook, ridiculing him for his chubbiness and making sarcastic remarks about his flabby muscles. That night, when Jimmy Laird huddled down with the other crew members in their makeshift shelter for a night of cold, damp rest, there was a glow of resentment in his ordinarily mild blue eyes, and a flush of shame on his cheeks. Moreover, his hitherto unused muscles ached abominably.

It was some time after the others began snoring that he rose and stole into his wrecked galley. There he stuffed his pockets with concentrated food tablets. Then he slipped out into the raw, windy night. A moment later he was plunging down the mountainside, loosing small avalanches at almost every stride. And so went the night.

Morning found him deep in a forest of tall, coniferous trees in an upland valley. It was chill in that mist-filled grove, but not so chilly as on the bare ledges of the upper heights. When the fog was lightened and warmed somewhat by the invisible sun overhead, he fed himself and slept for a while. Later he got up and continued his journey downward. His theory was that if he followed the watercourses he would sooner or later come upon an outpost of what civilization there was on the cloud-enwrapped planet.

Day after day he went on, ever down, down, down. It got warmer as he descended and the vegetation more dense. He sighted many weird animals, but they scampered away as soon as they sensed his nearness. The greenery took on a tropical cast and the undergrowth grew thicker. Thorny creepers tore at his clothes and ripped his face and hands. His shoes wore out and had to be discarded. Yet he pushed ahead. He could not stop now. His food supplies were running low and when they were gone he would have to die. Venus was an inhospitable planet to Earthmen, despite its lush vegetation and teeming fauna.

He thought on that, one night as he rested beneath a giant fern. It must be due to the absence of ultra-violet light, he concluded. Nothing that walked, crawled, swam or grew leaves on Venus but what was poisonous to man. But it had not always been that way, as the many ruins of great cities now overrun by the jungle testified, or the exhumation of great numbers of mummies of highly developed anthropoids closely resembling man. Physicists attributed the toxicity of Venusian life to the presence of such excessive moisture in the air that the shorter rays of sunshine could not get through. That had been a recent development, dating only from a few hundred thousand years back at the time of the Neovulcan Age when myriads of volcanoes had spouted vast quantities of hydrogen into the air.

There was nothing Jimmy Laird could do about that except to take care not to eat anything of native origin. But it did explain the basis of Venus' lopsided economy. Since it was fatally unsafe to eat anything of organic nature on Venus, her chief import was food concentrates. Such, indeed, had been the cargo of the ill-fated Pelican. Her exports, then, necessarily had to be minerals, in which the planet also abounded. Therefore her population was chiefly composed of miners, who, because of the hard and expensive living conditions, tried to clean up in two or three years and retire to Earth with their profits. Hence the greedy and grasping nature of the temporary residents that had earned the second of the sun's orbs the name of "The Chiselers' Planet." And from those hard facts also rose the meticulous mining laws of Venus and the arbitrary nature of its government.

All of which was no help at all to Jimmy Laird during his next trying week. He ate the last of his proteinax pills and sighed. He no longer resembled his former self, for his grueling journey had stripped him down to bone and hard muscle. Now he was to know wasting hunger. But he struggled on, hoping against hope that somewhere in that foggy domain he would stumble upon a human settlement. He was in a lush, hill-inclosed valley, torn and twisted by many recent geological upheavals. The stream he followed broadened into a lake and he saw that the mouth of the valley was choked by a range of hills through which the mountain torrent had been forced to cut a canyon. To skirt the lake he had to make a wide detour along the flanks of the surrounding mountains. It was on that trail that he made an astonishing discovery.

He came to a gully, down which a rivulet trickled. The gashed bank on the other side clearly revealed the tormented and twisted nature of the underlying strata, for layers of sandstone, folded like the crumpled pages of a book, were in plain sight, interspersed with other layers of clay, limestones and dark-colored matter. The gully was deep, but not too wide. He thought he might leap it. He withdrew a few yards and ran, gathering himself for the jump. But at the very edge of the ravine a creeper grabbed his foot. Instead of leaping free, he tumbled heavily and fell, face-down, into the muck of the bottom.

It was disconcerting. For he had instinctively yelled as he fell and struck with a wide-open mouth. When he sat up, not only was his face plastered with the clinging filth of water-soaked, decayed vegetation, but his mouth was crammed with it. He sat up, clawing fiercely with his hands to free his face of the slimy stuff and spat energetically to rid his mouth of it. Then his expression underwent a strange transformation. He froze where he sat, and blinked. His tongue tentatively roved his mud-incrusted teeth, his throat automatically gulped down what was found there. The sludge slipped into his gullet and he licked his lips for more. The stuff was good! It had taste—such taste as the old dietetic legends told of as pertaining to such archaic items as broiled sirloin, mashed potatoes and gravy, luscious artichokes and the like. Jimmy Laird smacked his lips and his hands reached down into the gummy slime for more.

"Boy, oh boy," he murmured, "not bad. No, not bad." Then, reconsidering, he revised his opinion. "It's wonderful," he breathed ecstatically.

For five days he camped beside that stream, eating greedily of its mud. His formerly opulent belly, then hanging in loose, flabby folds, regained its plump tautness. Once again rosiness drove the pallor from his cheeks. Jimmy Laird was himself again, despite his early fears that he might have poisoned himself by eating the forbidden fruits of Venus. Yet nothing adverse happened, and he set about making the strange food even more palatable. On the second day, after the first blush of enthusiasm for sustenance had worn off, he became aware of a certain grittiness in his Heaven-sent manna. He cured that by the simple expedient of filtering the substance through the tail of his shirt. Then it occurred to him that heat would improve it. So he contrived to build a fire, and, using the abandoned carapace of a huge tortoise for a caldron, made himself a pot of soup.

"Yum, yum," was his reaction, innocent of the fact that he was recoining an expression that had not been used for many centuries. And, appropriately, he rubbed himself in the middle in gesture of gratitude to whatever forest god had thrown the miraculous food in his way.

By sniffing diligently about the spot of his find, he finally located the source of the edible matter. It came from an inverted horseshoe crevice in the creek's bank, the barely exposed top of a sharp syncline. The waters of the stream had long since eroded most of the crumbly, olive-green substance that had composed the original stratum, but a good deal of it still clung to the top of the arch. He broke that off in chunks and made a pile of it beside his improvised camp. Then he systematically went about its refinement, bringing it to a boil, skimming off the scum that rose to the top, and filtering out the sand. Then he let it boil down to a stiff sludge which dried into a cake. Then he broke it into bits of convenient size and filled his empty pockets with them. Having thus fed, rested, and replenished his stock of provisions, he resumed his downward trek.

It was only two days after that that he stumbled upon a trail. It was a jumble of curious nine-toed footprints which he guessed to be the spoor of the sturdy hippoceras, the commonest beast of burden on Venus. Later he came across the ashes of old campfires, discarded food containers, and other evidence of man. It was not long before he smelled smoke and saw the stacks of a smelter looming up over the trees. And then he came to the edge of the clearing. Before him was a considerable town. The first leg of his journey was over.

He walked on, surprised that there should be so little signs of life. After a little, he entered a street between two rows of shacks. On the steps of one of the crude dwellings, two men sat. They were pale, gaunt and emaciated, as if from illness or long fasting, and their grimy miners' rags flapped idly on them. They were sizing up the rotund figure of the newcomer with unconcealed disfavor. Or was it envy?

"Howdy," said Jimmy Laird, ignoring their manifest hostility. "What town is this?"

"Hah!" snorted one, "as if you didn't know, you gluttonous slob. I can tell you this, though, you're wasting your time. We don't want no truck with Hugh Drake or any of his hirelings. We're hanging on to our claims, you understand, even if we starve. So you get to hell out of here while you're all together. This ain't a healthy section of town for profiteers or profiteers' jackals. See?"

He spat disgustedly. The other man spoke.

"You can tell Hugh Drake that a friend of mine had a letter a coupla weeks ago from Venusport, and that it said the Pelican was due any day. So we know the food caravan will be coming in most any time now. Hugh Drake can go pound mud in his ear."

"Hey," said Jimmy Laird. "I'm from the Pelican. She won't ever get to Venusport. She's lying way up on the top of a mountain, all smashed up."

The men looked at each other in frank consternation.

"Where?" they asked excitedly, springing to their feet.

Laird shook his head.

"I can't tell you exactly. 'Way up there," he waved his arm vaguely toward the misty region he had come from. "It took me the best part of a month to get down. The other men will be along later."

The men's faces fell. Now they registered blank despair.

"I guess Hugh Drake wins," said one, apathetically.

Jimmy Laird didn't quite understand the reference, but somehow he felt embarrassed. Absently, he put his hand in his pocket and drew out a chunk of his dried soup. He bit off a piece, then offered it to the others. They sniffed it, crumbled off bits, and popped them into their mouths.

"Say!" yelled the first one, "this is good. What is it—something new?" The other was chewing ravenously, the picture of bliss.

"It's better with hot water," said Laird, pulling a double handful from another pocket. "If you've got a stove and a pot, I'll fix you up a mess."

"We ain't got any money," said the starved miner, suspicious again, "and we ain't trading a grade-A iridium claim for no bowl of soup—"

"Oh, that's all right," assured Jimmy Laird. "I wouldn't think of taking money for this stuff. Anyhow, there's plenty more where it came from."

An hour later he was presiding over a huge tureen of steaming soup, while an endless procession of undernourished miners trooped past, each carrying a cup in hand. His new-found pals, Elkins and Trotter, had lost no time in passing the word around the neighborhood that Santa Claus had come to town. After the kettle had been emptied and refilled five times, the stream of starving men dwindled. Then Elkins and Trotter enlightened their benefactor as to the local situation.

"This Hammondsville is a tough town," said Trotter. "Old Man Drake owns the smelters; he owns the store and the bank and all these houses, and he owns the hippo herds. No matter what we do, he gets his cut. But where he gouges us the worst is on his food racket. Every year the caravan comes up and stocks the government dispensary and carries back the ingots in return. The hell of it is that they never leave enough at the dispensary and it usually runs out before the caravan gets in again. That's where Drake gets in his dirty work. At the dispensary we pay a pound of gold for an ounce of trephainin, but when we have to buy it from Drake, the sky's the limit. He'll say he hasn't got any to spare until a guy's practically starving and ready to assign his claim. Then Drake feeds him and pockets the mine. He's got a lot that way."

"He's a skunk," asserted Elkins, dismally. "Now you know what a jam we're in here. Down at the caravan loading square there's stacks of gold and iridium ingots as high as your head, and not a bite to eat. And if what you say about the Pelican is true, we may not get another caravan for months. The hospital's already full, and a waiting list to get in. But even that don't help. I hear they're about out of concentrates, too."

"Well, say," said Jimmy Laird, emptying his pockets, "that's not right. Take 'em this. I'll go back and get another load."

It was his turn to tell a story. He told them of the crackup of the ship, the gold strike, and what the captain and crew were doing. Trotter chuckled.

"I know that lode. It's a good one, but it's too far. Besides, you can't get a hippo to go above the timber line. Those fellows woulda been smarter if they had loaded up with the pellets in the cargo and come down with them. The way things are here, they coulda had all the gold and platinum in town. You did better than all of 'em put together. There's a big bonus offered for anybody that can start a food industry on this planet."

Laird described his find in detail.

"Lemme see," said Elkins, studying the ceiling. He felt very fine, now that his hunger was assuaged. "That would be Starvation Valley—all the strata churned every which way. You made a strike, then it dives outa sight. Many a one of us has gone broke there. It burns you up to keep having to drive new shafts, and even then you lose the pay streak nine times out of ten."

"Wait a minute," said Trotter. "This stuff of his is soluble. All we need is a drill rig and a donkey boiler and some pipe. Shove down a pair of pipes, shoot steam down one and soup comes up the other. Dry out the steam in condenser pans, and there's your concentrate. I think the fellow's got something."

There was a little talk of ways and means. It did not take long to find willing helpers. A dozen miners, grateful for being saved from Drake's clutches, came in with offers of the loan of equipment. Even a small herd of privately owned hippoceri was located. Then, at Trotter's and Elkins' insistence, Laird hied himself to the local registrar of claims and filed his claim. After that they assembled their expedition and set off.

It is remarkable what enthusiasm can do. In ten days Starvation Valley was a hive of activity. Men, not only willing but eager to work for mere food, had done wonders. Two donkey boilers puffed away, fed by cords of wood that had been cut by the volunteers. From four pipes driven deep into the sunken stratum, which Laird's self-appointed experts found sloped sharply downward from the outcropping he had found, jetted rich soup. The pipes delivered their streams through strainers to drying pans from which the condensed essence was cut in cubes and wrapped. A few of the patient, plodding, pig-like hippoceri were always present, being loaded with hundreds of pounds of their precious cargo for the lower valley.

"Old Hugh Drake will be plenty sore about this," grinned Trotter, "He hasn't made a dishonest nickel this year. But you'd better watch him, kid; he plays dirty pooh."

Jimmy Laird grinned back and pointed to the newly painted sign that one of his admirers had put up. It read:

"LAIRD'S LUSCIOUS SOUPERY—KEEP OUT!"

"That won't help you. kid, if the old pirate really gets his back up. He's got drag."

Laird found out that was true prophecy when he went down to Hammondsville again. He had just left the dispensary where he had been informed that the replenished stocks were more than satisfactory. "The stuff is swell." the chemist in charge said. "We analyzed it, and it's got everything—all the known vitamins, and calories enough to keep a working elephant going. We'll take all you send at the regular rate. Venusport and the other towns can use it, too, and that means that hereafter we can import a few luxuries from Earth." That had been reassuring, but when Jimmy Laird walked out and was halted by a member of the constabulary, he did not feel so good.

"Your name Laird?" asked the man. He was a hard-faced customer with steely blue eyes and a cast-iron jaw. Laird admitted that was his name.

"O.K. We've got a place all swept out for you at the hoosegow. This way."

Laird looked at the six feet of brawn, at the ham-like fists, at the flame gun at his belt, and back again to those boring, merciless eyes.

"Yes, sir," he said. And he followed. He felt miserably insufficient, as he always had when in encounter with the brutal, direct-action type. He sighed, but there was nothing else he could do. Just follow.

Mr. Drake, he was soon to learn, had preceded him to the town's police station. He was a skinny, grasping old man with gleaming eyes separated by a hawk nose.

"Get it all down," he croaked to the booking clerk, "illegal entry, working a mine without a license, inducing men to work for him without wages. I claim the reward under the terms of Article 456 of the Mining Statutes, which entitles me to receive one third interest in any confiscated property denounced by me."

"It's all down, sir," said the subservient clerk. "Officer, lock this man Laird up in Cell 21."

Jimmy Laird was pretty downhearted. He had had misgivings all along. For he had read those very statutes and knew they had him. To be eligible to own a mine on Venus, one must first duly pass the immigration office at Venusport, pay his head tax, and receive a license. The penalty for failure to comply was confiscation of the mine, a heavy fine, and deportation. If unable to pay the fine, he was subject to indenture to whatever citizen of Venus who did pay it. That meant he would probably become one of Drake's vassals.

Jimmy Laird languished in that jail for a solid month with nothing to divert him but his own gloomy thoughts. Then came a day when the footsteps of a keeper resounded in the metal corridor and he was told to come out. Court was about to convene.

The courtroom was packed. As Laird found out later, a famous high judge had been sent up from Venusport to try the case, in view of its importance, but Jimmy had no inkling of that when he glanced up and saw his forbidding countenance, and the scowling prosecutor arranging his papers. So he sat down meekly in the prisoner's dock and looked out onto the crowd of miners assembled in the seats. He picked out Elkins and Trotter and others he knew, and noticed that Elkins stood up and clasped both his hands together in the traditional distant salute of friendship. Then he turned to hear what the damning evidence against him was.

There was not so much of it at that. A drier-than-dust clerk of the central registration bureau at the capital testified that there had never been a mining license or entry permit issued to any James Laird. He sat down. Then Hugh Drake arose to speak of illicit mining operations in Starvation Valley he had observed from under cover, and of the distribution of non-approved food products at cut prices throughout the local area. He demanded confiscation of the mine, and all other penalties. After that the prosecutor summed up in a florid denunciation of schemers and would-be get-rich-quick irresponsibles who tried to exploit the lovely planet of Venus for their own selfish needs. Jimmy Laird listened to his eloquence with a quivering and despondent heart.

"Therefore," thundered the prosecutor, "I demand the condemnation of this Earthling upstart for illegal mining and the assessment of all the penalties he so richly merits." He yielded the rostrum with a triumphant glare at a small, dapper gentleman who sat at a nearby table. Jimmy Laird looked at him, also, and in some surprise, for he had not noticed him before and had no idea who he might be. The new figure got up and addressed the judge.

"I move," he said, in a startlingly clear voice, "that this case be dismissed for lack of jurisdiction. This is a mining court. My client is not, and never has been, engaged in the pursuit of mining—"

Jimmy Laird started. He a client! How come? He had hired no lawyer, or even seen one. They had held him too tightly incommunicado for that. Yet here was a man referring to him as "my client."

But the prosecutor was on his feet again and angrily objecting.

"Your honor, this motion is frivolous and absurd—mining is defined as the occupation of digging or tunneling in the ground. The defendant has done that. I know that my opponent in his brief contends that since the substance mined is organic, it ceases to be a mineral but a foodstuff. Again he is defeated by the definition. A mineral is anything that is obtained by digging, whatever its composition or ultimate origin. The decisions sustaining that point are too numerous to mention; the courts have invariably held that such products as petroleum, natural gas, coal, and even lignite are minerals."

"Quite so," smiled the dapper counsel for defense. "Are we then to presume that my learned adversary considers peanuts, truffles and potatoes minerals? Is the cutting of peat a mining operation?"

The judge blinked. Then said, "Go on."

"I have been retained by the outraged citizenry of this town to assist in this case, and I have studied all its aspects thoroughly. The nature of the alleged mineral, for one. Both the Geologic and the Biological Bureaus have made investigations and reports. The former states that prior to the Era of Neovulcanism, when Venus' climate was not unlike the Earth's, vegetables and animals nutritious to man abounded. At the time of the great eruptions, these were struck down, engulfed and buried by volcanic ash. The result was a layer of ancient forest mold enriched by the addition of many plants and animals. This was later overlain by other rocks, and became dessicated and compressed to its present form. But at no time has its essential organic nature been altered. The Biological Bureau reports that Laird's Luscious Soup is nothing other than an infusion of that substance which we now know to be so rich in vital food values, and soup, traditionally, is just such an infusion of selected organic juices.

"Moreover, the Viceregal Decree of Decimo 14, 2047, for the Encouragement of Food Production on Venus uses these words: 'Any person, of whatever planetary allegiance, and whether or not so specifically licensed, who may discover and develop a source of natural food upon this planet, shall be awarded a suitable bonus, a free site of operations, and shall be entitled to the full protection of the government, whether such food supply shall derive from farming, fishing, trapping, or otherwise.' That otherwise, I submit, disposes of the charges completely."

As the lawyer finished, the crowd broke into a wild cheering that made the walls rattle despite the judge's vigorous pounding for quiet.

"Don't let Hugh Drake put that over!... Hooray for Laird!... Boost home industry and tell the Synthetics Corp. to go to hell!"

While the excited miners yelled, Trotter advanced down the aisle carrying a steaming pot of Laird's Luscious Soup. The tumult was so great that no one could hear what passed between him and the judge, but in a moment the jurist raised the offered cup and took a sip. The smacking of judicial lips that ensued could not be heard, but the melting of his stern expression to one of easy contentment could be seen by all. Hugh Drake and the sycophantic prosecutor edged their way toward a side door. They had read the handwriting on the wall even before the judge sat up and cried:

"Case dismissed."

"Shucks," said Elkins, once they were outside. "It was no trouble at all. We passed the hat and then hired that fellow from Venusport. We figgered we owed that much to you."

Laird bubbled his thanks. But he noticed Elkins seemed troubled about something. Jimmy asked him what was on his mind.

"Well," drawled the miner, "it's this way. The fellers have helped all they could and you have a fair start and all that, so they're thinking something about their own business. You see, now that they're fed and grubstaked for the season, they want to get back to work on their own claims, I know that's going to be hard on you—there's so little free labor hereabouts, what with Drake having all the down-and-outs gagged and bound out to his smelters—but the boys'd appreciate it if you could let them go."

"Sure," said Jimmy Laird, not wanting to discommode any other human being, "I'll find a way."

It was not easy, though. When he got back to Starvation Valley and let his helpers go, he found that there were not enough hours in the day for him to stoke both boilers, cut and carry wood, run his drying pans and the packaging. And it was out of the question to load the hippos and drive them down to Hammondsville and back, unless he shut down from time to time. With the whole planet clamoring for the new and tasty food, he was reluctant to do that.

It was just when he was wrestling with that problem that the first of his former shipmates showed up. It was one of the tube gang, and he was as haggard and bedraggled a specimen as ever came stumbling out of the jungle. His clothes were in shreds and he was wolfishly hungry. Moreover, he carried not an ounce of gold. He had discarded that a long time back in his frantic effort to find haven and food before he caved in. Jimmy Laird fed him and gave him a place to sleep.

By twos and threes, the remainder of the crew straggled in, all in the same or worse condition. They had made the initial mistake of starting out with too heavy a load of the nuggets and not enough of the Pelican's bountiful supply of food pellets. The result was inevitable. By the time they reached Starvation Valley, they were empty-handed and mere shadows of men.

Captain Reagan was as hollow-cheeked and crestfallen as any. He took Laird's handout without a word and gulped it eagerly. The warm, strong broth perked him up considerably, and he cast an inquiring eye about the clearing where the two puffing boilers stood, the neat sleeping shacks and the cooking pans. Then he asked if there was a town nearby where he could make arrangements for the transport of their mountain treasure.

"Well, I'll tell you," said Jimmy Laird, hospitably ladling out another bowl of the fragrant soup, "there is, but I'd hate to see you go there the way you are. It's on account of those mining laws I tried to tell you about. They'll grab your mine, if anybody thinks he wants it, and throw you in the clink. And then, when you can't pay the fine, they'll sell you as a smelter hand. It's a hard game to beat."

Buck Reagan looked unhappy. After his cook's desertion, he had come across the volume of laws and read them.

"Of course," Jimmy went on, "knowing how you feel about it, I kinda hesitate to offer you a job with me, but then again it might help you out of your jam. I need men. And I'll pay good wages and feed you, too—"

"We'll take it," said Captain Reagan, despairingly, looking at the boilers with fresh curiosity. Jimmy Laird's flamboyant sign faced downstream so its face could not be read from where Reagan sat. "What will we have to do?"

"Help me make soup," said Jimmy Laird. And he never did understand why the captain almost choked.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.