RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

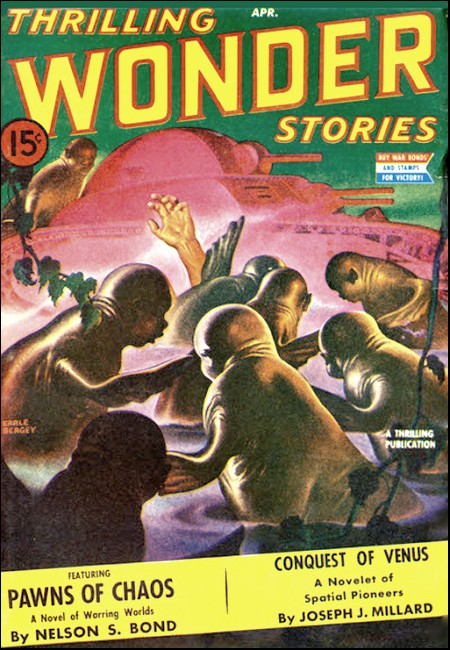

Thrilling Wonder Stories, April 1943,

with "Lotus Juice"

Ulysses Had Nothing on Sid Barton, Alias Paul Trewin, When

the Young Chemist Was Venus-Bound on the Trail of a Mystery!

THE ship's lounge was not a cheery place. It was just a compartment set apart where the few occasional passengers of the Venus-bound freighter could sit during the tedious run from Earth. A dozen of them sprawled in chairs, snoozing or daydreaming—employees all of Venus Enterprises, which owned the ship and most of Venus. Some were returning from errands on Earth, the rest were new men hired as replacements for others to be invalided home.

It was in the latter class that the one who styled himself Paul Trewin fell. He, alone, was alert, watching with grimly determined eyes and hard-set mouth the growing disk of the silvery planet. In a few more hours they would be landing. Then what?

Paul Trewin rose, glanced about him, and strode to the cubbyhole that was called his room. There he took two slips of flimsy paper from a secret place in his luggage. For the thousandth time he read over the formulae he had jotted on one of them.

They were excerpts from his missing father's notebook, now safely filed with a trustworthy institution on Earth. Trewin had long since memorized the entire contents of that book, but had taken the precaution to carry along the formulae as a last minute refreshener.

He dared not hold the memo longer, so he carefully tore the paper into small bits, chewed and swallowed them. After he had disposed of them, he took one final lingering glance at the other sheet of paper. It was a copy of the last letter he had received from his father, the eminent Doctor Claudius Barton, and the date on it was nearly two years old. It read:

Dear Sid:

The quest is ended! All the details and the diagrams of the machine I have devised are described in the code that only you and I know, and are in the note-book I am entrusting to our good friend Bill Latimer for personal delivery to you. Knowing the close scrutiny applied to everything leaving this accursed place, I dare not do otherwise. The Company's greed is unbounded. I need not add that they never hesitate to use bribery, blackmail, theft, intimidation, even murder, to obtain what they are after. It may well be that this will never reach you, though I am hopeful.

There is less hope for the sample bottle of essential oil that should accompany it. It is bulky, and also radioactive, so that there is no possibility of Latimer's smuggling it out. I'll have to entrust it to the common mail, suitably enclosed in lead. If it arrives safely, file for patents at once, not only on the product, but the mode of manufacture and its uses. If it does not arrive, and you do not hear further from me, you will know the worst. Venus Enterprises has been watching me closely for some time, and there are days I tremble.

Should the worst happen, I implore you not to seek revenge, since if they can get me, they can get you also. But find my body if you can and take it back to Earth with you, even if you have to exhume it. I am confident the study will prove profitable.

Dad."

Sid Barton, alias Paul Trewin, stood with clenched fists and blazing eyes as he destroyed that final communication. No bottle had ever come, nor any other letter. Inquiries addressed to the Regent of Venus had come back endorsed simply, "Not known," or "Believed lost in jungle about three years ago," according to the whim of the clerk responding. On the other hand, Venus Enterprises, more generally known as "Vent," had made no effort to market the marvelous new oil, which indicated that if they had it they lacked some vital link in the chain of production.

It was for the triple purpose of solving that mystery, as well as retrieving his father's remains and avenging his death that Sid had altered his personality to that of Paul Trewin, consulting biochemist.

His forgery of background and experience must have been convincing, for Vent had hired him after many gruelling examinations and the most meticulous search of his bogus past. If any of the suave, Earth representatives of Venus Enterprises suspected his disguise, none betrayed it by the flicker of a lash. In a short time Paul Trewin would be at work in Vent's big laboratory at Erosburg. And in that laboratory lay the records he must have.

THE newcomers huddled together on the concrete platform under the shelter of a metalloid shed. All wore the corrosion- and water-proof slickers, boots and helmets that were the "must" outdoor uniform for all Earthmen on Venus. A torrential rain was falling with a thudding roar, blotting out the view in all directions. All about was a sea of yellow mud and water puddles onto which the incessant downpour fell, only to rise again as an evil-smelling, scalding vapor.

Trewin was cynically amused at the hot indignation of some of his fellow hirelings over the searching examination they and their effects had just been subjected to. The fresh-caught Earthlings did not yet know that once they were on Venus human dignity no longer counted. Except for the pitifully inadequate Patrol Detail, who found it more expedient to look the other way than forever to be quarreling with the influential vested interest that owned much and controlled the rest, there was no power on Venus to which appeal could be made. Trewin was doubly thankful that he had not clung to those flimsy notes.

Presently, through the hot mists, the waiting passengers could hear a tremendous splashing and the singsong patter of Venusian "dibbies" calling out. A string of rickshaws drew up, pulled by the plodding natives up to their knees in the yellow muck. The vehicles were light affairs and their wheels were shod with wide tires of woven wire which acted snow-shoewise to keep them from sinking hub-deep in the mire.

The passengers piled in, and without a word the rickshaws dashed off again. There was no need to tell them where to go. A new arrival in Erosburg always went first to the administration building of Vent.

There was little to be seen except the plunging, mud-spattered bare legs of the native dibbie. But on rare occasions the rain would cease long enough to let the eerie yellow light of the upper air pervade everything. Then the gaping newcomers could glimpse gigantic palms, swaying gently and dripping diamonds, while gaily-colored bird forms swooped and darted with shrill cries among them. Monstrous hippolike creatures wallowed about the trunks, but Trewin merely glanced at them with mild interest. On Venus the worst enemy of man was man himself.

They passed on by a dibbie village of grass huts on stilts, where native children sported in the mud. Then the rain closed in again and no more was seen until the huge outlines of a windowless building suddenly loomed before them. The string of rickshaws slowed, then halted.

The Earthmen went forward one by one to be examined at the portal. It was a door guarded by bastions manned by heavily armed members of Vent's company police. It was more than ever apparent that one entered Vent's stronghold by invitation only. Or, as Paul Trewin reminded himself grimly, by ruse.

Five of the machines had gone on, when Trewin's puller hitched his vehicle forward and stopped before a spy lens. Trewin displayed his passport and orders to report for duty, saw the blink of a green pass light, and then got out as the portal slid open for him. He paid the rickshaw man the two coppers that were his customary due and added another for a tip. He stepped inside, heard the portal click shut behind him and found himself in a bare, metal-lined room. A guard surveyed him sourly, then pressed a button and a panel slid back, revealing a shiny cubicle.

"Get in," said the guard.

Trewin stepped in, the door shut immediately and the cubicle began to rise. A moment later it stopped. Trewin stepped out into a small room without other visible opening. Suddenly the lights went off and his heart leaped, but after a minute or so of blackness the lights came on again, this time with blinding brilliance.

A voice began barking questions at him through an unseen transmitter. Trewin answered them patiently, but he recognized the shrewd questioning as a variety of the "third degree." At length there was a long pause, followed by the curt order:

"Take off your oilskins and drop them where you stand. Then enter the door that opens and follow the corridor all the way. Mr. Fawley will see you in the last office of the row."

Mr. Fawley! Trewin could hardly suppress a start. Fawley was the head of Venus Enterprises, and few of Vent's wage slaves ever talked face to face with him. But Trewin strode down the corridor as boldly as though his heart were not filled with misgivings. Things had been too easy; it did not bode well.

AT the end of the corridor he found a gleaming room in which was a big desk. Behind the desk sat a man regarding him coldly through milky pale eyes, whose mouth was compressed into a hard, straight line. Trewin sniffed the cool dry air of the room and understood the absence of windows; out of the corner of his eye he glimpsed the heavy leaden door of a vault.

"You are Paul Trewin, formerly a consultant chemist, now employed by us as a research man." It was an announcement, not a query.

"I am."

"You are rated as an expert in essential oils derived from super-tropical vegetation. I presume you are familiar with the pioneer work of Dr. Claudius Barton?"

"Reasonably. I have read his published papers. My field was in Malaya and Borneo; his in the Congo. They are quite a distance apart."

"Ah," murmured the man behind the desk, never relaxing his icy, boring gaze. After a long and wordless scrutiny, which Trewin took without flinching, Fawley rose and went to the vault door, twirled the combination and swung it open. He went in, then reappeared with a heavy container which he placed on his desk.

"What do you make of this stuff?"

Trewin approached the desk and examined the bottle. It was a bottle of lead glass containing a heavy, oily liquid which was purple in color. He unstoppered it and sniffed a faint aroma mildly reminiscent of honeysuckle. It was the stuff his father had described in the notebook.

"I wouldn't know, sir," replied Trewin, frowning; "it's unlike anything I ever saw. You've analyzed it, of course?"

"Partially. What we want to know is how to make it."

"Not knowing the composition, or its properties," said Trewin, "I can't answer that offhand. If you would let me have your lab report and the files on it—"

"Never mind the analysis," snapped Fawley. "That is unimportant. We already know what it will do. Let me show you one of its properties."

The steely-eyed chief opened a desk drawer and produced a pipette and a beaker half filled with water. He drew out a tiny droplet of the purple fluid and let it fall into the glass. The water promptly took on a violet hue that gave off an enticing odor.

"Taste that."

Trewin looked only at the beaker, thinking hard. Then he picked it up and drank, in the full conviction that it would not harm him. If Fawley suspected him, he would hardly have played so elaborate a game merely to poison him in his private office. Yet his father had made no mention of his discovery as having possible beverage uses; this particular compound had been designed as a source of atomic power—a revolutionary discovery, since it was an organic compound made from one of the commonest of the wild plants on Venus.

An amazing thing happened as the pleasant sip trickled down his throat. Trewin straightened up like a slouching soldier suddenly snapped to attention. He knew his eyes were blazing, and he tinged with energy and ambition, with a desire to excel all men in whatever his hand found to do. In a moment the first great glow was over, but he retained the sense of well-being and power.

"Great, eh?" Fawley asked with a curious, crooked smile. "Now you see why we want to go into mass production. Think of what a droplet of that will do for efficiency. It is sustaining also. It contains several powerful vitamins and an almost incredible amount of energy units; little other food is needed with it. Imagine what would be the result if we sold it throughout the system!"

"Big dividends, I should say," drawled Trewin. "But doesn't it burn people out?"

"There are armies more at the employment gates," shrugged Fawley, adding pointedly. "There will be big dividends, as you say. There will also be a substantial reward for the man who shows us how to make it."

"Why not ask the man who made this?" Trewin wanted to know.

Fawley coughed discreetly, then drilled Trewin once more with his cruel eyes.

"The man who produced this batch died, unfortunately, without telling us the secret of it. He had a little laboratory out in the wilds. His plant is still there, intact, but none of our experts here have been able to unravel the process. You have a rare opportunity to get off to a good start with the company should you succeed where they have failed."

"I'll do my best to unravel every angle of it," assured Trewin, trying to keep the grimness from his voice.

"Very well," said the man at the desk, jabbing a button. "You will start at once." Then, to the guard who appeared as if from nowhere, "Take this man over to Monkle and tell him to get going. Monkle knows what to do."

MONKLE proved to be a guard captain, a big, bearded fellow, coarsely jovial one instant and brutally harsh the next. Beside him was a bald, fish-eyed person who introduced himself as Torden of the research department, offering a limp and clammy hand. Trewin liked the looks of neither of them, and also noted that though Monkle could have broken him in two with his own bare hands, he wore a blaster in a shoulder holster and a pair of needle guns at his belt, not to mention a wicked skinning knife strapped to his right leg.

"Step on it," growled Monkle. "The musher's waiting."

The musher was a big amphibious tank, manned by a crew of half a dozen dibbies. They climbed into it and it rumbled off to a portal which mysteriously rose like a portcullis to let them through. They skidded sharply as the treads struck the slimy street, then lumbered off through the rain-sodden town. Despite the padded seats, Trewin found musher riding anything but comfortable. The machine plunged indifferently through lakes and mud wallows, or slithered down a muddy embankment to crash its way through mangrove-like swamps, hurling shell-bearing sea things right and left. Thus they floundered for hours until at length the steel monster heaved itself up onto a mudbank and lurched to a grinding stop.

"End of the line," yelled Monkle, snatching out the ignition key and pocketing it "All out."

They got out, and Trewin noted the expressions on the faces of the docile dibbies as they lined up in the drizzle outside. Their faces were pathetic and resigned, as was the custom of their fatalistic race. Every dibbie knew that few of them who went with the man Monkle on an expedition were ever seen again. And Trewin had a shrewd hunch that he was in the same boat with them. But he shrugged the thought off. He had come too far to turn back now.

"Straight up the hill," said Monkle, sloshing along behind.

A little way up the slippery path they passed a broken-down musher. Its treads and sides were encrusted with rust and scale, and overgrown with mosses and vines. Scattered about it were many bones and human skulls.

Trewin could hardly suppress a shudder at the sight, for they evidenced another horrid Venusian custom. No one bothered with burials on that easy-going planet, for the abundance of crawling and flying things, aided by the humid heat, made the rite unnecessary. Any cadaver would be no more than a mass of clean-picked bones within a matter of hours.

The group plodded on. After pushing their way through much lush vegetation, they at length came to a clearing in which sat a low structure built of blocks of native cypress and bearing a rain-tank on its roof. Beyond it a conveyor belt ran to a distant hopper-like structure standing in the midst of a profusion of brightly-flowering bushes. Trewin took it all in at a glance. It was similar in layout to their first plant in the valley of the Congo. There was no doubt that he was about to enter his missing father's secret laboratory. And then?

Monkle unlatched the door and went in, only to reappear with a bundle of machetes. He dealt these out to the dibbies, growling at them the while in the guttural monosyllables of their dialect. Then he turned to Trewin, giving him a rude shove.

"Inside you, and get that gadget working."

TREWIN went in without remonstrance. It was his role to play meek now. He surveyed the big machine that filled most of the room. Yes, this was it. It was built on the same general lines of the one in Africa, but was far larger and more complex. He did not marvel that the experts sent by Vent to unravel its mysteries had failed, for if he had not helped his father construct the earlier model, and had not the advantage of the coded notes, he would have been as badly stumped as any of them.

"Well?" Monkle was impatient. Trewin noted that Torden had a sheaf of papers in his hand, which he was studying with a puzzled air.

"Give me time," replied Trewin, angrily. "Your other experts must have worked on this thing for hours—how do you expect me to understand it at a glance?"

Monkle grinned knowingly, but ended with a growling, "Okay, but make it snappy."

Trewin looked at the fuel gauge. There was enough to power the machine for days. Then he examined the settings of the master control dials. At first he was baffled, for they seemed set slightly off neutral. Neutral would give water. The slight variation must then mean water with impurities. He read the code symbols on the dials carefully, matching them with those in his memory. Then he grinned inwardly. His dad, the foxy old cuss, had set the machine to produce swamp water! A glance and a sniff of the half-filled bottles sitting about the floor at the delivery end confirmed his suspicions.

"Yeah. Swamp water," snarled Monkle, behind him. "Come outside a minute. I want to show you something else, so you'll know where you stand."

The "something else" was an irregular row of crumpled and disintegrated human skeletons lying about on the soggy soil.

"Those are the other research guys that couldn't get nuthin' but swamp water," Monkle explained thunderously. "Get it?"

Trewin nodded. His dilemma was acute. If he failed to give them what they demanded, they would torture him to death; if he gave in, Torden would take notes and the secret would be theirs, whereupon they would kill him. Either course meant failure, and Trewin had not stuck his head in the noose to fail.

"If you weren't so hard, Monkle," he said, with a show of defiance, "you might get somewhere. I'm trying, but you're not giving me the breaks. Listen, I'm a young fellow—and practical. I don't want to die yet, and I think I can make that machine work. But I have to have a little cooperation."

"Like what?"

Trewin's mind raced. His father had told him that the Venusian lotus plant's juices were the most complex organics he had ever encountered. Their molecules were dizzily arranged in intricate ring systems superimposed on chains and grids. By the use of ultra-violet rays, supersonics, and a few simple catalysts, they could be cracked and then rearranged in an infinitude of other ways. One familiar with the machine could synthesize a product of any desired properties by simply setting the dials. But in order to take advantage of this, Trewin had to stall his captors.

"Like providing the thing with fodder," answered Trewin, hopefully. "Somebody has to supervise the hopper, another the macerator—"

Monkle laughed.

"The dibbies are doing that. See 'em cutting the stuff? The hopper's nearly full."

"But that's what's wrong," cried Trewin. "That's why they always got swamp water! You shouldn't cut 'em, but pull 'em up by the roots and feed 'em whole—stems, leaves, roots, berries and all."

"Okay," grinned Monkle, with studied insolence. He bellowed orders to the head man of the dibbie crew, who promptly signalled his understanding. That's that. What else?"

BUT Trewin couldn't think of anything else. He had to take a chance now. He turned his back and went in to where the machine was. He walked around behind it and released the hidden catch that locked the dials. He opened the water supply valve and drain, adjusted the violet light and super-sound feed knobs, then came back to the master dial. Torden had followed his every step, noting each action in a little book.

Trewin considered the master dial and then began setting it to his father's formula. The purple color and the enticing odor were, he knew, derived from the flowers; the vitamin and food content from the leaves, and the oiliness and power from the berries. He set the dials to omit the power. The stuff would thus look and smell like the original sample, but would be valueless commercially.

But Trewin had to do more than that. So far he had only ensured his swift death rather than a cruel, lingering one. His captors would look, smell, taste—then shoot. He considered for a moment the properties of the root juices. His father had left them out of the present formula for several reasons. One was that they were poisonous.

Poison? His hand reached for the dial, then faltered. No, that would not do. They would be sure to try it on a dibbie first. But he might modify the poison. He rapidly thought over a list of narcotics, hypnotics, and other nerve-damaging drugs. He selected one and set it up. As an added fillip he reached over and stepped up the odor ingredient by several notches.

"She's ready," he announced, slapping in the power switch. He leaned back against the work bench as the macerator began to grind and the conveyor rumble. Surreptitiously he dipped some grease from a pan by his elbow and stuffed it into his nostrils as a filter. Then, as the converter before him started humming, he placed an empty jar beneath its delivery spout.

All three waited, their eyes glued to the spout. Presently a purple drop-appeared. Another and another, the drip changing to a trickle, then a stream, as the bottle began to fill.

"Got it all down, Torden?" asked Monkle, drawing a needle gun.

"Got it," grinned Torden, evilly. "Shoot."

"Wait!" shrieked Trewin. "Hadn't you better check it? I think it's all right, but I'm not sure."

"You know it's right, Doctor Sidney Barton," sneered Monkle, taking slow aim. "We knew who you were all the time."

"Maybe he's right," intervened Torden, doubtfully. "He's never actually worked the machine before. Fawley'll skin us alive if we've busted it."

As Monkle reluctantly lowered the gun, Trewin snapped the power off. He reached for the bottle and handed it to Monkle. Monkle raised it to the light and shook it to examine its color and consistency. Now was to come the crucial test of the desperate gamble.

Monkle lowered the container and sniffed. His nostrils caught the enticing, familiar odor, but now it had been raised to compelling intensity. He fairly leaped for the bench to snatch a beaker. He dropped a little of the new fluid into it and took a taste.

"Wow!" he yelled. "It's the McCoy, all right."

"Make him taste it," ordered Trewin with startling brusqueness.

"Huh?" said Monkle, but at the same time handed the tumbler dumbly to Torden. Torden demurred. He had evidently seen the cowed look come into the guard's eyes.

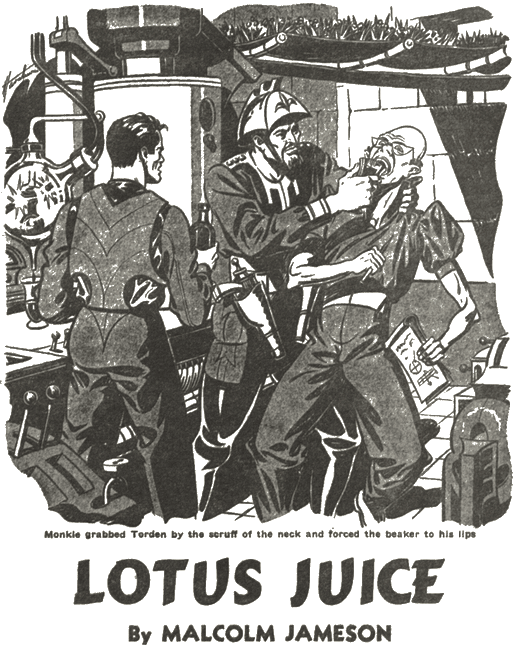

"Taste it, I tell ya!" roared Monkle, grabbing him by the scruff of the neck with a hairy paw and forcing the beaker to his lips. "Didn't you hear what the master said?"

The hapless research man had no choice. He gulped down a mouthful. Then both men turned and looked at Trewin helplessly, as if awaiting further orders.

BARTON regarded them both sternly. His trick had worked; they were susceptible to instantaneous hypnotism, baited by an irresistible odor which he himself could not smell.

"I am your master," said Barton. "You will obey every order I give, whether oral or mental. The time for lying and double-dealing is past. I want the truth—the whole truth, from the very beginning."

He beckoned Torden to him.

"Give me those notes."

There were not only the notes, but photostatic copies of the pages of his father's notebook and letter to him. Barton asked Torden where they came from.

"Mr. Fawley had Latimer frisked," whined the chemist. "We took copies of everything and returned the originals so that he wouldn't suspect. But nobody could break the code. So we put out ads for new chemists, hoping you would answer. And you did."

"Yes?" snapped Barton. Then whirling toward the gaping Monkle, "What's your story?"

"I been watching your old man ever since he hit Venus. Fawley said to leave him be until the old buzzard got some results. Then he picked up the notes and the sample jar. So he says to give him the works and he came along with us. We got here, but the old man wouldn't talk. So we gave him the old one-two-three. He still wouldn't talk. He croaked himself. So we bumped off all his dibbies and put the musher on the blink, so it'd look like they all got caught here and starved to death. He kept sendin' me out here with other research guys, but none of 'em had what it takes, so I bumped them off, too. I guess that spills it."

"Where is my father?" asked Barton in a voice of thunder.

"Oh," said Monkle, pointing to a door in a far corner, "in the storeroom there."

"Sleep!" commanded Barton, and watched them both droop to instant slumber. He rushed to the storeroom door and yanked it open, then paused in horror on the threshold. Tears brimmed his eyes and a great lump seemed to choke him. There was his father's body spread-eagled against the wall like an animal trophy!

But it was a time for action, not sorrow. Barton steeled himself to his task. Upon examination he found they had fastened his father to the wall with giant staples driven around his wrists and ankles after having subjected him to cruel treatment.

Barton's first impulse was to cut the body down, but upon reflection decided to leave it where it was for the time being. By some manner it had resisted the usual Venusian disintegration, and his father had hinted that was something worth looking into. So the younger Barton softly closed the door and made it fast.

"Tell me more about my father's death," he barked, waking Monkle from his stupor.

"Yes, master. It was this way. The old boy was just about to break, but he looked groggy, too. So Fawley said to lay off a minute. Then the old guy said he'd spill but that he felt faint and wouldn't somebody give him a drink of that orange-colored stimulant over there."

"Over where?"

"Oh, it ain't here any more. Fawley took it off to Erosburg with him to analyze. Anyhow, the old coot took a snifter. Then passed out. Foxy, huh? He ducked while the ducking was good."

"That will be all, Monkle," Barton said. "Wait here." He left the guard and withdrew to a far corner of the room to think the situation out. His father was dead. It was true that the body showed no sign of dessication, but neither had it pulse or breath. For nearly two years it had hung there without food or water, a manifest impossibility for a living man. He had Monkle and Torden in his power and could kill them with a thought. Those were the facts, but what did they avail?

Fawley was still alive and unpunished, and the prestige of Vent undiminished. Young Barton knew that it would be as impossible for him, as it had been for his father, to get out of Venus alive with the precious evidence of the great discovery unless he somehow subdued Fawley. Then, too, he had to get a sample of the liquid his father had drunk. There was only one thing to do. He had to go back to Erosburg at once.

It was getting dark, so he hurried back to Monkle who was sitting quietly, awaiting his orders.

"Can you find the way through the swamps at night?" demanded Barton, and receiving docile affirmative he followed with, "Very well, snap out of it and let's go. Bring Torden along."

IT was well after the time of Vent's opening hours the next morning when the musher drew up before the door of the administration building.

"Get this," warned Barton. "Tell Fawley you have succeeded and that you have a bottle of the new stuff and a translation of the code. Don't mention me, but I'll be right behind you. The minute you get into his office let him smell the stuff. See that he drinks it, too."

All the successive barriers of guards waved them pass. Barton stayed close behind until they reached the door of the private office. He delayed there only as long as was necessary, then entered. Fawley was already under the influence of the will-destroying potion and as helpless as his minions.

"I want everything you robbed from my father's laboratory," commanded Barton, "plus all analyses made of them, including the substance by which he met his death."

FAWLEY meekly brought it forth. "Now," announced Barton, "we are going to the Regent's high court where you will confess to my father's murder, and you will forget that my father drank poison."

"Yes, master," they chorused.

Their departure from the building was as unimpeded as the entry. No guard in it could have been brought to believe that their shrewd general manager, their burly captain, or the wily chief chemist were under the mental domination of the young stranger walking along behind them.

When they reached the courtroom, Fawley advanced to the bar, held out his wrists for manacles and began to drone out his sordid story. A deputy regent was sitting as magistrate, and his eyes nearly started from their sockets at what he heard.

As Fawley spoke, Barton saw a shifty-eyed guard slink from the room. In less than ten minutes a pompous gentleman came rushing in, uttering indignant objections. He was, it appeared, the general counsel for Venus Enterprises. The magistrate ordered him to listen to the confessions.

"But, Judge," bellowed the irate lawyer, "this is a farce. I can't make it out. What if you have got three free and full confessions to murder? That don't make a case. Where's your corpus delicti? I defy any man living to produce a recognizable body of a person alleged to have been killed two years ago in any of the swamps!"

"I'll take that challenge," said Barton quietly. "Just wait until I have attended to a few other matters."

Those few other matters did not take long. The three murderers were led away. Barton filed his petition to have Venus Enterprise's charter revoked on various and well-sustained grounds. He made application for a charter of his own. By that time a detail from the Patrol headquarters had shown up. It consisted of a captain, a medical officer, and a photographer.

"I'll ride with the Patrol," said the company attorney stiffly. The Patrol captain grudgingly grunted permission. The Patrol had no love for Vent, but as a rule found it useless to buck it. Today they were enjoying their first ray of hope.

Just as they were leaving, a stranger stepped up and introduced himself as Kelling, chief newscaster of the system-wide televox service. He had overheard the confession and smelled a five-alarm scoop. Barton invited him to come along.

A patrol car followed the floundering trail of the musher closely. The two cumbersome machines pulled up onto the banks of the swamp together. Barton pointed out the stack of dibbie bones beside his father's wrecked vehicle. Farther on he showed them the pale skeletons of the unfortunate chemists.

The Patrol captain growled something and made a note of it. After that they went on to the laboratory.

"Here, gentlemen, is the final proof," said young Barton as he led the way to the storeroom in which his father had been placed.

The Patrol captain looked about, then turned to the blustering counsel-general.

"The charge sticks," he announced. "Try and talk your way out."

The doctor went outside to examine the remains of the other victims, while the photographer took many pictures. They offered to remove Barton's father, but Barton would not permit it.

"The trial may be postponed for months. He is as well off here as anywhere—better, if I may say so," he said. "I'll be responsible."

THEN the Patrol party turned their car toward Erosburg, leaving young Barton and the newscaster behind. Barton at once began a feverish study of Vent's analysis of the orange liquid. It corresponded to a compound listed toward the end of his father's book. He noted, too, that this particular formula was bracketed to another. And he wondered again about his father's emphasis on the desirability of recovering his body for study. Had his father merely devised an embalming fluid that was proof against local conditions? Or had he foreseen his danger and concocted a potion which would induce suspended animation?

Barton set the dials according to the new formula. There was ample raw material in the hopper to make the amount he would require. It was not long before he had a liter of it—a brilliant green liquid that smelled of blood.

"Let's take him down now," he whispered to Kelling, too tense to speak out loud. Silently the other helped him carry the limp form to the bench. Barton found a hypodermic needle, sterilized it, filled it with the green liquor, and proceeded to administer it.

It was minutes before he got a response. Then there was a perceptible rise in temperature, a faint flush, and the beginnings of an almost inaudible heart beat. A sudden, spasmodic inhalation of breath ended the injections.

Young Barton stood tense and anxious, watching the fluttering heart beats and labored breathing. It was an hour before the old man opened tired, vacant eyes. Understanding came into them abruptly.

"Take it easy, Dad," urged Sid, his own heart pounding now.

"I knew you'd do it, lad. I knew it." Dr. Barton was smiling now. "But what about Vent?"

"No. They didn't get away with anything. But you'd better take a nap now. We'll tell you all about it later," his son reassured him.

Young Barton made his father as comfortable as possible and then proceeded to pack the musher with the things he wanted to take back to Earth. He carefully set the controls of the huge machine back to swamp water and locked the set. He poured out the remaining power oil in the fuel flask. The machine would be useless until he returned again.

Later, when his father had rested and eaten, they undertook the trip to Erosburg. But it was not until they were well clear of the stratosphere and headed for Earth that young Barton told his father the climax to all he had done.

"But, son," objected the old man, who despite his mistreatment had retained his sense of justice, "you have put these men on trial for my murder, and drugged them into pleading guilty. And I am still alive!"

"No," admitted Sid, with a shrug, "they didn't actually murder you, but I wouldn't worry if I were you. They'll probably manage to get out of that charge. But if there is any worrying to be done, I'll have to do it."

"You!"

"Yes. I broke my word. I said I'd produce your body in court to clinch the case. But I'm darned if I do!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.