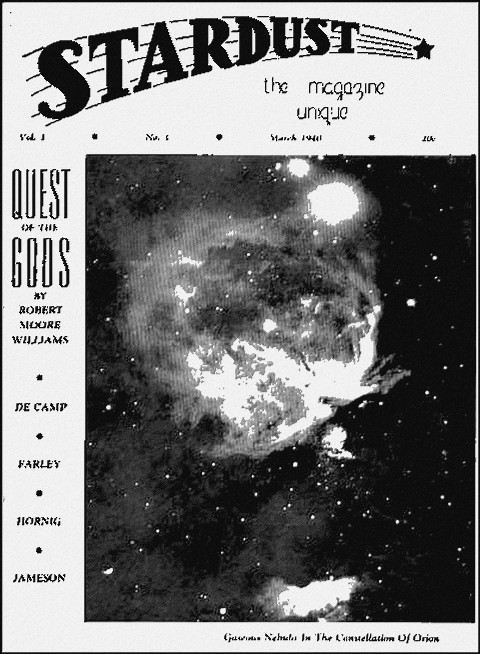

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

Stardust, March 1940 with "Einstein in Reverse"

It is an established fact that the Universe is in constant motion. What then would the Universe look like if seen from "Absolute Rest" if such a condition could be possibly attained? The author of this short story tells you the answer to that, problem, but in answering it another, greater problem appears!

"H-m-m," grumbled the Professor, gnawing at his scraggly beard as he withdrew his hand with the dividers from the dim visiplate on which the images of all the stars shone faintly. "Are you sure you applied components for each and every bit of motion?"

"Oh, quite," assured Harry Longwill, his experimental pilot. "Check with me if you like. Here's the figure for the Earth's rotational velocity, its orbital velocity, the Sun's own motion toward Vega, our rotational velocity about the axis of the Galaxy, the drift of our Galaxy toward the Ultimate Point, Zeta, plus the other eight factors you gave me, and finally there is the rotational speed about the Ideal Center of the Whole Universe."

"Ah," breathed the Professor, relieved. "It seems all to be there. And we have been accelerating all this time along a resultant exactly contrary to those figures?"

"Yes, sir. It is more than three months now since we hopped off on this voyage—braking ourselves in Absolute Space, so to speak. In another few minutes we should have exactly overcome all those velocities. Then we can observe the real movements of all the heavenly bodies, not merely have to deduce them as heretofore."

"It will astonish the world." said the Professor, thinking rosily ahead to the day when he would mount the rostrum of the Great Hall of Science and read his paper to an admiring world. He had already selected its title: "The Proper Motions of the Universes as Seen from Absolute Rest."

Longwill looked back at the visiplate. Outside the scintillating points of the universe gleamed much as they always had, or at least so he thought when he first looked. Yet, strangely, the stars seemed a bit smaller and closer together, and the black areas of the reaches of the Extra-Universe seemed larger and more intense. Presently the whole of the Earth's own Galaxy seemed to be but a cloud of fine mist, clinging to the periphery of the space ship itself, and the outlying brilliant clusters of the far-off Island Universes seemed much nearer. Yet they, too, had shrunk. They were barely visible as minute puff-balls of smoke, just a few yards away.

Twist the viewfinder as he would, he could get no other picture, and his astonishment was deepened as the faint mist he was watching became even more nebulous, as if it were vanishing into the pores of ship itself.

"What do you make of that, Professor?" asked the Pilot.

The last faint glimmer of anything outside had vanished. As far as vision could reach in any direction there was—nothing. Nothing but the void and the utter darkness of starless space. The Galaxy, the Universes and all about them had vanished. There was no more of anything except the lonely ship and its two curious occupants.

For a moment the Professor's expression was one of deep bewilderment. Then he tugged ruefully at his beard and gave an apologetic little laugh.

"Sorry, Longwill, that I got you into this. To be truthful, I did not expect such a tragic ending. It was terribly careless of me. I admit. You see, in my anxiety to be the first to achieve absolute motionlessness. I overlooked some of its implications. We are all that there is, now.—You and me."

Longwill stared at him. Was the Professor mad?

"As you know, Einstein demonstrated that when an object attains the maximum possible speed, that of light, its dimension in the direction of its motion becomes zero."

"Yes, but..."

"It follows from that, that since we have dimensions in three or more directions, we must have some speed in each of those directions, but somewhat less than that of light..."

"Naturally, but...."

"Well. That those dimensions we are used to have always been stable and finite indicates that our speeds in the various directions have been stable and finite. Had we gone faster in any particular direction. we would have shrunk correspondingly. Now, we did not do that. On the contrary, we reduced our speed in every direction until we achieved zero velocity. That put us at the other end of the Einsteinian curve. Our dimensions, being limited by our velocities, now have no limits, because every conceivable velocity we had has been cancelled. Hence we have become infinite in size. The universe we knew, being itself finite, is therefore tucked away somewhere in the interstices of one of your or my atoms!"

Longwill looked glum.

"And our points of reference with it?"

"Yes There is no way back. Once we become infinite, there is nothing we can do about finite things."

"But we're still accelerating," objected Longwill. "Then what?"

"Oh, dear," said the Professor, reaching for his slide rule. "That raises another problem."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.