RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

Thrilling Wonder Stories, December 1941, with "Time Column"

YEARS ago Science-fiction was considered escapist literature of the most violent sort, creeping into the realm of the written word as a lusty successor to the Yellow-back Novel and the Penny Dreadful. Today that classification not only would be unjust; it isn't so considered in the general attitude of the reading public.

Nowadays folks escape with detective or western or love stories. Science has moved so rapidly to the fore that science-fiction barely manages to stay far enough ahead to be considered prophetic.

In this year of disgrace particularly, 1941, when the world is being subjected to shocking news of daily bombardments, and is changing so rapidly that newspaper headlines become in twenty-four hours as passé as the Mauve Decade, to write science-fiction with any attempt at prognostication is to invite disaster, especially when it deals with present world situations.

Such a story is Time Column, by Malcolm Jameson. By the time you read these lines international situations may have changed so radically that certain bits of this splendid yarn may read like yesterday's newspaper.

Nonetheless, this is a timely story and is worthy of being remembered long after many political aspects have faded. Here's what Malcolm Jameson has to say about Time Column:

In common with other decent-minded people, I have been outraged at the spread of international gangsterism throughout the world. I can't hang the men responsible for it actually, but I can in effigy, so to speak. So, in Time Column, instead of inventing a villain. I borrowed the arch-villain of all history—Adolf Hitler. The problem was to overthrow him.

Now, science-fiction is so full of instances where clever scientists have smashed brutal tyrants that it was hard to find a method that was new. Time travel has always had an appeal for me, so I explored its possibilities as a means of waging war. I found that a flanking movement, carried out through the dimension of Time, was the answer. But since all existing Time machines operate only in one dimension, a problem at once arose.

To attack a place from the rear (in the time sense) the army must be moved to the spot at some prior time and in a way that its movement would not be recorded in history. That involved going back to prehistoric times, which in turn produced a new set of problems dealing with food, supplies, transportation, etc. It was evident at once that the attacking army would have been self-supporting from the moment it was launched. It was also evident that such an army could be quite vulnerable to sabotage.

By pouring all these factors together and stirring vigorously, the answer came out the way it did. The stuff jelled into the Time Column. Near the end there was one last hitch, and I lost a lot of time thinking up appropriate ways to dispose of the masterminds of villainy. Eventually I sidestepped the issue by adopting the simple expedient of turning the whole gang loose with no one to prey upon but each other. After that, nature presumably took its course. —Malcolm Jameson.

Empress Brunhilda's entry was deliberately paced and dignified.

(Chap. X)

Across the abyss of years Major Jack Winter leaps

to save

the world—and finds something priceless he had lost.

HE felt in his change pocket but all he could find were two coins. The sixpence was too small, so he gave the taxi driver the other—a shilling. Then he bounded up the steps of the War Ministry, resplendent in his new uniform of a major of the British Special Engineering Corps.

Major Jack Winter flashed his appointment card on the bobby at the door and passed on in. In a few minutes more he was fidgeting in a chair across the desk from a stodgy major-general. But there was nothing stodgy about the general's mind.

"Ah, quite so," he was saying, "your papers are in perfect order. Moreover, we have many letters from trustworthy sources, including the American Embassy, as to your special abilities. That explains why we have commissioned you in the Special Engineering Corps. Although your country is not wholly at war, a number of your immediate companions will be adventurous Americans like yourself."

The old gentleman cleared his throat, resumed.

"You are perhaps wondering at the secrecy thus far preserved. It is now time to tell you. Your corps has been assigned to a very daring undertaking. It is no less a project than the immediate invasion of Germany and the capture of Berlin!"

Major Winter blinked. It was early fall of 1941, and England was still girding herself to resist her own invasion, an event that might occur any day—as soon as Hitler finished his detour through Russia. Such a bold counter-stroke seemed impossible. But all Winter said was:

"Good sir. Count me in."

"You are not stunned—dismayed?" asked the general.

JACK WINTER fingered a spot just over his heart.

A small gold locket lay there, out of sight beneath

his uniform. It contained a picture of a lovely

girl, fair-haired and blue-eyed, looking out at

the beholder with frank, brave smiling eyes. Frieda

Blenheim had been his fiancée. Two months ago she

had died under the axe of a top-hatted headsman in

Leipsic.

She had been a music student there when the frontiers were closed against her. Her offense was that of being caught by Gestapo agents in the act of feeding two miserable Polish refugees cowering in her cellar. Treason, they called it, though she was American to the core, despite her heritage of German blood.

"I would go through hell," Jack Winter said harshly, his fierce intensity making the words more like a more like a prophecy than the expression of an idle wish, "to get to Berlin. Before I die I intend to find that arch-devil Himmler and wring his scrawny throat with my own two hands."

"Ah," said the stodgy general, a trifle startled at the other's vehemence, "so much the better. Here is a pass which will admit you to the conference now in progress on the floor above. They are discussing the expedition. You have been appointed as special aide to the commander. Your duty will be to look after supply."

"Supply?" echoed Major Winter blankly. "I asked particularly for a fighting job."

"Don't quibble," admonished the old man calmly. "You will find fighting enough where you are going. Take the second door to your left. The meeting has already begun."

Major Jack Winter entered the conference room and stood for a moment in the background, silent. A heated argument was in progress.

"Preposterous, I say!" bellowed an old war-horse, thumping on the table. A bristling white mustache accentuated the redness of his face. Winter recognized him instantly as General Sir Stanley Formley-Higgs. K.C.B., V.C., D.S.O., etc., veteran of many campaigns. He had fought with the Zulus and the Afghans, had seen service in Burma, China and the Sudan. Just now he was nearly choking with indignation.

"It is absurd! Fantastic! Idiotic! I want nothing to do with it! A detour of ten thousand years in time, indeed! What crackpot advanced that idea?"

"I did," Sir Stanley asserted a crisp, cold voice quietly, and Winter noted that the speaker was tall and spare and aquiline, with jet-black eyes. His head was square as a die and topped with a stiff pompadour. He wore civilian clothes, and in his hands was a sheaf of papers.

"Within a few months Germany will be an empty shell, attacked from every side," he went on. "She is already spread out perilously thin over occupied territories, and Hitler's troubles in Russia are just beginning, despite his seeming triumph in Greece and the Balkans. If you could appear suddenly in the heart of Germany with an army, you could roam over it at will, just as Xenophon did in ancient Persia."

"Granted." snapped the general. "If we could only get there."

"I have perfected the machine that will enable you to do it."

"Yes, a time machine!" snorted the florid general. "Har-rumph!"

Winter could not repress a start. This kind of talk was crazy. But was it? In the throes of war the British Empire would not go to the time and expense of assembling a special engineering corps of military experts and squander millions on supplies just to talk about a fantastic dream.

What a stupendous conception! What a staggering idea! If possible, it could revolutionize warfare. It could turn the world topsy-turvy. It was as far beyond Hitler's fifth column tactics as these were beyond the old espionage system. A Fifth Column—through time!

MAJOR WINTER let his imagination roam freely for a

moment, envisaging regiments of troops being fed into

some sort of hopper or contrivance which would carry

them back through the centuries to a time where there

would be no opposition—before even recorded

history began. He saw these troops making their way

across sea and forest and marsh into the heart of

wild, primeval Germany, setting up their machinery,

and coming back through the centuries to burst forth

in the very heart of the enemy's citadel. A detour

through time! A Trojan Horse, indeed! A surprise

attack that had no precedent in history!

Major Winter leaned forward and touched a fellow listener on the shoulder.

"Who is that man?" he asked in a terse whisper.

The other glanced curiously at his lean, drawn face which still had the marks of recent grief. "Hugh Snyder," he whispered back. "A mathematical genius and inventor. You must be Jack Winter. My name's Kelly. Intelligence."

They shook hands briefly, and turned back to listen. Winter reflected on what little he knew of the man who bore the name of Hugh Snyder.

Hugh Snyder was a shadowy and almost legendary figure who for several years had been whispered about in the highest governmental circles as being engaged in developing a secret weapon that would astonish the world. Until today no one other than a few cabinet officers and the small and select group of technicians who worked with him in his hidden laboratory in Cornwall had actually seen him. Winter looked at him with a new interest. This venture promised opportunities in warfare that he had never thought of before.

"Since our mathematicians have at last found the great fundamental formula which binds energy, matter, space and time together," Snyder was saying, untroubled by the skeptical looks on the faces of some about him, "we are able to state that we can now manipulate matter so as to make it go backward in time and then bring it forward to the present again.

"Time may be regarded as a sort of rut or groove down which matter has already passed. It seems to be continuous to the past, but non-existent as to the future—as the furrow behind a plow. By the use of special solenoids formed of alloys of rare metals we can convert electric current into a curious negative gravitational force which cuts the barriers of past time with ease. Matter placed in its field can be projected at the rate of about a thousand year a second. Even living organisms suffer nothing by it. The only objections are—"

"Yes, yes," interrupted Sir Stanley, testily. "Let's come to those."

"First, the metals needed are scarce and expensive. Besides iridium and tungsten, we must employ several of the rare Earth metals, and their isolation is notoriously difficult. The machines we have just built or which are under construction are all that we can possibly build. Hence the need for their most economical use. Secondly, we have not been able to penetrate the future. Thirdly, owing to the very high speed of travel, a fine control of time movement is impossible. I find that the smallest practicable unit is five thousand years."

"Due to?" queried a member of the General Staff.

"Due to Time Inertia. Enough current to jolt the subject into movement at all will kick it fifty centuries on the same impulse. That may seem to be too coarse a unit, but it really doesn't matter. Our controls are so delicate that by a reversal of the current, the time traversed on the back track will be equal to the other. In jumps of five thousand years or so into the past it is immaterial whether there are a dozen more or less years' error. If the two legs of the journey are equal, the discrepancies cancel out."

THERE was a rustle of papers as Snyder finished.

Winter seated himself, exhilarated at the prospect of

participating in this daring adventure whose route lay

in the uncharted depths of prehistoric time.

The plan was astounding in its boldness and yet so simple! Walls of fortifications meant nothing any longer, such a Time Column could by-pass them and come up inside. Moreover, as an offensive weapon it had no peer. Even should the enemy learn that there were such time-traveling vehicles, they would not know where and when they would materialize and begin spouting men and guns.

Winter listened with keen interest as the details were discussed. He learned that a small test machine had been tried out with experimental nights to the Cornwall of 3,000 B.C. and successful return. The country was reported to be bleak and desolate and without inhabitants, but astronomical observations made by the explorers checked the time range exactly.

They emerged from their return trip unharmed, having been gone exactly the amount of time they had spent in ancient Cornwall plus the dozen seconds needed for the flight. It was then that GHQ had decided to gamble on the expedition. They authorized the building of as many machines as possible and the detail of picked divisions for the fighting job.

Winter's Engineering Corps was to handle transport, and that he learned quickly, was to be an important job. He began taking notes feverishly, in a glow of burning ambition.

The council went on to talk of fuel and ration problems, since nothing was known definitely about the Britain of fifty centuries before.

An auxiliary army of artisans must be provided to assemble the ships that would be needed in 3000 B.C. to move trucks and tanks and field-guns across the North Sea. Power for the Time machines must be provided at both ends, and there were thousands of other items. Last of all, they close the site for the take-off—a spot in a forest of Scotland, not far from Glasgow. Callandar was the name of the place.

Winter gathered up his notes and got up from the table in high spirits. At last he was about to get somewhere. In America he had raged and denounced as one small nation after another had been tricked or bulldozed into subjection by the Nazis. He had watched the brutal tactics with high indignation.

But when they cruelly murdered his sweetheart, Frieda, he could contain himself no longer. He had thrown up his engineering job and hastened to Canada, begging to be sent to the Front.

Well, here he was, and in what a Front—the Time Column!

He dreamed that night of the occupation of Berlin, of the sudden eruption in its center of an army of angry veterans, of their quick seizure of the nerve centers of the Reich.

That would be enough. The universal wave of uprising among the enslaved peoples of Europe could be counted on to do the rest. It was breath-taking, colossal. And he was part of it!

BEYOND Callandar the woods were teeming with activity. Major Winter walked through them, accompanied by Captain Kelly, the brigade's intelligence officer. Everywhere there were shops and factories or assembly plants, carefully camouflaged by bough-decorated low roofs. Gasoline storage tanks abounded, and the finishing touches were just being put to an electric generating plant for the Snyder Time-Shuttle.

Hugh Snyder himself, the dark and taciturn inventor who had spoken so forcefully at the conference in London, joined them. He was a queer and cold sort of codger, Winter thought, somehow not as friendly as the major had figured at the conference.

"These are the propulsion rings for the Class-B machines," he said, pointing to a long row of metallic hoops laid on brick piers.

A bank of transformers stood close by and electricians were completing the hookup. Alongside the first of them a gang of welders were busily assembling a huge steel sphere from orange-peel-shaped plates. When finished, the sphere would have a diameter of about fifty feet.

"The rings are expensive, containing as they do many pounds of rare and costly metals, but at that they are far more efficient than the other system for transporting large quantities of material," explained Snyder

."What other system?" asked Kelly.

"The use of Class-A machines, the self-propelled ones," the inventor replied. "So far I have built only one of those, though there is one other under construction. They are the same size as these spheres, but have less carrying capacity, owing to the necessity of having to carry their own generating plant. Moreover, their cruising range is only some fifty thousand years. After that the elements have to be renewed, and since those are chiefly platinum and iridium, we can afford to build only a few. We must use these sparingly.

"On the other hand, the Class-B units are inert. They proceed through time much as a batted ball does through space. We place them within those rings, load them, then throw an impulse of power through the rings. They at once disappear and rematerialize thousands of years in the past. To send them back to the present, of course, it is necessary to have another set of sending rings at the other end. On such an expedition as this, such a complementary station at the an other end is perfectly practicable."

"Yes," commented Winter. "I remember the general plan. But when do we start, and for where? Where is that completed Class-A machine?"

"I am taking you to it now. We will get in and take a run back to prehistoric times to pick the site for the other base."

They went on in silence. Winter noted that a number of tanks had already arrived and were parked in groups of three and four, awaiting loading into the time transports. In another place he saw stacks of steel plates, nicely curved and punched for rivets, which was to be sent back in time and erected to serve as storage tanks for the immense amounts of gasoline to be needed by the army.

There were machine tools, too, and small blacksmith's forges, field kitchens, mountains of cases of canned goods, and much else. It was a little awesome to see assembled in one spot just a fraction of the stuff required to maintain a considerable army in the field for half a year or more. And he was responsible for a big part of this.

The Class-A time machine was a silvery sphere with no ports and but a single circular door which, however, was wide enough to admit a ten-ton truck or the fuselage of a small fighter airplane. Winter's quick eye took in at once that such a plane was already loaded inside the machine, its detached wings neatly laid alongside it. Its pilot stood beside the door, talking with the several men who were to go along to re-assemble it.

"All set, Miller?" inquired Snyder sharply.

"Yes, sir," replied the aviator. "Everything is ready."

SNYDER inspected the interior of the sphere,

testing a tube there and a connection in another

place. Then he closed the door.

"You will experience a few queer sensations, but there is nothing about them that will hurt you. Time velocity is impalpable. What you will feel will be a sort of earthquakish vibration as the ship adjusts herself to the rise and fall of the ground level through the ages."

Major Winter watched him closely as he set the starting lever. A gauge above the power bank calibrated to 50,000 years registered full. The speedometer over the operating desk registered zero. Snyder put the lever in the first notch and pressed a button.

Winter and Kelly felt a slight surge, followed by a trembling that sent electric thrills through their frames. There was a moment of nausea, an instant's blindness, then a sharp jolt. "Not bad, eh?" And the ordinarily scowling and silent Snyder allowed himself a wry smile. "We're there."

"Where?" chorused several shaky voices.

"On the same spot in Scotland, only five thousand years ago," answered Snyder. "Get out and have a look at three thousand years before Christ."

They clambered solemnly out, looked and gasped. The forest was gone. Everything was gone. All about them was only a grassy plain. The mountains in the distance were no longer familiar of shape, being harsher—more rugged. A frightened doe rose from the grass and scampered away. A bevy of startled birds fluttered upward with raucous cries and joined her flight. Of human habitation there was no sign.

"Looks okay," said Major Winter, taking over and affecting a calm that he was far from feeling. "But it would certainly be a devil of a spot in which to have a breakdown. Trot out the plane, boys, and put it together. We'll take a short hop and look around."

Queer thrills were making his spine tingle. It was uncanny to be assembling a super-modern airplane in the Bronze Age. He found it hard to believe this was real or himself more than a figment in a weird dream.

Yet a few hours later he and Kelly squeezed themselves beside the pilot in the tiny two-seater. He was beginning to like Kelly very much. The plane was a special job by Grumman with low speed and no armament, but having a goodly cruising radius. They set her motor humming and shortly were over the highlands to the north of them. The country below appeared to be virgin country. There was neither a crude man-made shelter nor a wisp of smoke to be seen.

"Take a turn in the opposite direction, Miller," ordered Winter.

The pilot obediently headed south. They crossed the Clyde, circled northern England and came back north along the east coast. It seemed to them that the east coast was farther east than it should have been, and much less indented. The Firth of Forth had narrowed to a rivulet.

It was not until they were nearly back to their starting point that they saw the first vestige of humanity. Atop Stirling Rock they spotted rectangular designs, and swooping low, they saw that these were the crumbling ruins of a habitation of some sort, gone to ruin untold centuries before.

Then, about ten miles beyond, they sighted a solitary human figure sitting on a stone and idly watching a flock of some dozen sheep.

"A man!" yelled Winter. "Set her down, Miller."

IT was an old man, haggard, long-bearded, and

almost naked. His only garment was a brief skirt of

plaited strips of fur, faintly suggestive of the kilts

of plaid that were to follow four thousand years

later. When the plane grounded a few hundred feet away

from where he sat, he only lifted his head. He looked

on apathetically as the three men approached him,

showing neither surprise, fear nor pleasure. He simply

sat, staring at them woodenly.

"Hard-headed Scot," commented Kelly. "He isn't human."

Kelly, who was a linguist, addressed the ancient Breton in several languages, but got only a sullen silence for a reply. He plied him with pure Gaelic, and finally elicited a couple of sour grunts. The three officers sat down in a semi-circle while Kelly persisted in his attempts at communication.

After fifteen minutes the intelligence captain managed to get somewhere, dragging coarse guttural sounds in bursts of two or three words from the old man's throat. Then the conversation began to proceed a bit more smoothly. At last Kelly sat back and reported what he had elicited from the incurious old man.

"He says he thinks he is the last man alive. It has been twenty years or more since he saw another human being, and that was when his wife and sons were taken by the terrible sickness—obviously a plague which swept across Europe. He does not know what the ruins on top the rock represent—perhaps a castle of the giants who ruled this country thousands of winters before his own race began.

"Legend has it that they were a fierce and warlike people and built houses that floated on the water. They preyed on other people who lived in a vast land on the other side of the sea, out of which the sun rises, bringing back many captives and other booty."

"What became of them?" asked Winter.

There was more painful interrogation. The old shepherd had not used his meager vocabulary in years.

"He says no one knows. There was an old tale about a sickness that killed ninety-nine out of every hundred. The gods, as he calls them, then fled to the northland where it is always ice. He thought our plane had been sent by them to take him to Valhalla. That is his story."

"Hmmm," mused Winter. "I guess it's lucky in a way we stopped where we did. It would complicate things for us enormously if we had to fight our way through pre-Norsemen, and look out for an unknown plague to boot. Let's leave the old guy alone and report back to Snyder. He'll be anxious to get his machines started on this time shuttle."

They returned to their starting place to become panic-stricken. There was no Snyder, and more alarming, no time-machine. There was only an indentation in the grass where it had been, and a small mound of stuff beside it. The three officers left the plane and ran over to the pile. It proved to be a pup-tent, a few cooking utensils and two cases of assorted grub. There were three hunting rifles, too, and ammunition for them. That was all.

"Marooned, by Jupiter, in Time!" yelled Miller.

Winter looked at Kelly, and Kelly looked at Winter.

"Hold it, chappie." said Kelly quickly, his own lips white.

"What do you think of this fellow Snyder?" asked Winter bluntly.

Kelly shook his head.

"Personally, I haven't doped him out yet. Intelligence has combed his pedigree from A to Z and they say he's regular, but somehow the more I see of him the less I like him. Take the malevolent way he stares at you. Take this..."

"Yes, this," thought Winter, with an involuntary shudder. Three men and a few supplies alone in a depopulated country, five thousand years away from their own era and kind. Far off, beyond the forests of primeval Europe and the Mediterranean, there was an alien civilization in Egypt under the first pharaohs and in the valley of the Tigris. Those crude peoples, he recalled, were not hospitable to strangers. They made slaves of them, or sacrificed them to their gods.

Why had Snyder abandoned them?

"I agree with you," he said aloud, making an effort to pull himself together. "When I heard him explain his machines in London that day, I was fairly well impressed, but somehow since—"

THE sound of a distant shot caused him to quit

speaking. All three of them wheeled and looked toward

the quarter from which it came, hope stirring in their

hearts. For an ancient gunshot was impossible. The

Chinese hadn't invented gunpowder yet.

Then they saw the crew who had assembled the plane coming through the high grass. One had a doe on his shoulder. Apparently they had been hunting to while the time away When the mechanics arrived, they brought the explanation of Snyder's abrupt disappearance.

"Oh," said one of them, "Colonel Snyder said the site looked okay, so he took off alone. Said it would save hours getting the expedition started. The Class-B machines ought to start coming pretty soon.

"Hm-mph!" snorted Winter suspiciously, glancing at Kelly. "I still don't like it. That was a report we were supposed to make."

That night he tossed on his cot and tried to think it through, but somehow he could not put his finger on the source of his suspicions. It was only that there had seemed to enter Snyder's attitude toward the expedition a subtle change for the worse. That was the incomprehensible thing about it.

He had invented the means and had fathered the idea, yet lately, when watched at moments when he was off guard, he seemed contemptuous of it, almost sneering. It was that sly change of manner that was so baffling.

In the morning, though, the fleeting uneasiness of the little pioneer group seemed silly. They were awakened by the sound of howling klaxons, and sprang from their blankets to see a number of the Class-B machines dotting the field about them, with others materializing every moment. Several were disgorging their passengers. Men in uniform or dungarees were swarming out, and presently a captain came up and saluted.

"Reporting with the first consignment," he said. "Inside is a duplicate set of the propulsion rings in sections ready to be hooked up. We brought along a knocked down power-plant to run 'em so we can shoot the empty spheres back home. Where do you want 'em. Major?"

"Five hundred yards to the left of where the containers lie," directed Winter, putting last night's doubts out of his mind.

Inventors were queer people. The explanation might lie there. In any case, his own job was not intelligence, but transport, and no man in the Time Column was more anxious to get to Berlin than he. There was still a sea to cross and miles of forest to traverse before another set-up was made.

He walked over to show the engineering squad where to set up the generating unit. Kelly followed him, grinning.

"The Time Column is on the march," said the Irishman. "Think of it, Jack—ping-pong across the centuries, with fifty-foot spheres for balls!"

"I am thinking of it," said Winter grimly.

But he was thinking of Leipsic in 1941 and Frieda Blenheim.

IT took three days to erect the plant and get it working. Major Winter had occasion to pat himself on the back many times for the completeness with which he had worked out his supply schedule. He had made few errors of calculation.

The first of the spheres held a donkey boiler, a pair of electric generators, a transformer, and all the tools and accessories needed to put them into operating condition. The next group was loaded with the nested arcs of the projector hoops that needed only coupling together and being put on suitable foundations. After the second group, more of the Class-B machines kept popping into sight every few hours—as fast as the receiving area was cleared—bringing bricks and mortar, more workmen, galvanized iron and studding for the shacks to be built; and more important to the men on the ground, food supplies and a first-class camp cook.

It was Winter himself who fired up the boiler, using fuel oil from the drums that had come with it. A score of the empty time-travel spheres were already in place on their propulsion rings. As soon as his generators were up to speed, he cut in the circuits one by one and watched the steel globes vanish, bound back to the year 1941.

"Hold everything. Jack," said Kelly, after seeing the fifth one make its shimmering disappearance. "Shoot me back in the next one. Any message for the folks up there?"

"Yeah," grunted Winters. "Send down my mail, and a batch of late newspapers. This business of fighting a war at five thousand years' range is duller than I thought. And tell that bird Snyder to leave me a note next time he does a quick fade-out. That first night here was a nightmare."

Kelly grinned, nodded and stepped into the machine. Five seconds later, according to the watch on his wrist, he was walking out of it into the Twentieth Century. A sentry saluted him and called his attention to a sign nailed to a nearby tree.

WARNING!

KEEP CLEAR OF THE PROJECTORS

AS TIME SHUTTLE S MAY

MATERIALIZE AT ANY MOMENT.

He pulled aside to allow a file of troops to pass him. They marched straight into the machine he had just vacated until the officer with them called "enough!" There was a flicker, and the machine disappeared. The expedition was beginning to move in earnest!

"Down below," as everyone was beginning to call it. Major Winter and his gang worked ceaselessly throughout the daylight hours. When nightfall came they would throw themselves on the grass, exhausted, while a night shift took over. These men tended the two propulsion rings that handled the gas transport.

Every hour a sphere filled with high test gasoline materialized and had to be connected to one of the two pipelines that led down the slope to where the great storage tank had been promptly erected. The motorized equipment already in use required great quantities of fuel, above which consumption it was necessary to build vast reserves.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Miller in his plane scouted the eastern shoreline and found a suitable harbor in which they were to launch the motor-driven barges then being prepared in sections at what would some day be Clydebank. Those would be the last things to come down.

Pine forests had first to be located, trees cut and dragged by tractors to the harbor. A gang of workmen had already established an advanced camp there and was building several sets of pile-driver leads against the day when the pines should arrive and they could construct the docks.

Back at the main base, Winter's growing crew had built storehouses, into which carloads of hams, barrels of salt meat, flour, beans, coffee and sugar were being carted daily. Cigarettes were regarded as a necessity, and those came in large quantity. Another storage tank was being erected at the harbor and a pipeline between it and the one at Main Base laid.

GENERAL WORREL, the rather fatuous commander of

the entire expedition, marveled at the efforts of the

indefatigable young American. He, like the overseas

young man, nursed a private grievance against the

Nazis, as well as cherishing the universal indignation

caused by Hitler's arrogance toward the rest of the

world.

His home in London had been gutted by fire and half the members of his family killed. He was not sure where the others were. All members of the British Time Column took joy in their work, knowing that every hour was bringing them closer to the day of reckoning. Overtime spent in greasing the skids for Messrs. Hitler, Himmler, Goebels, and their gang was a positive pleasure.

"This is a remarkable maneuver, all right," said Worrel one day, "and magnificent in its simplicity.

"The only thing that troubles me is that for a time we will be cut off from two-way communication with 'up there'. It is a pity we haven't one of the Class-A type machines back here."

"Yes," agreed General Worrel thoughtfully, "but they are very expensive. The partly finished one is all we are going to get. There is no more material. But why do we have to be cut off?"

"Because the shuttles require rings and power at both ends," explained Winter. "As soon as all our stores are accumulated and we are ready to cross the sea, they will ship down the remainder of the rings for us to take them with us. After we have moved our expedition to the site of Twentieth-century Berlin we will need every one of them for the sort of surprise mass attack we have in mind. The tanks, infantry, and the propaganda experts who are to take over the Axis radios and spread the news must be sent up promptly. After the victory we can send back for the technicians and laborers."

Worrel nodded. He could see the difficulty of keeping in touch with GHQ.

"The final plan will be sent down by the second Class-A machine," he commented. "After it comes, we will leave Scotland altogether. From then on we will have to move blind on a strict time schedule."

Yes, time was the essence of it. The Battle of the Atlantic was growing critical; the night bombings were making a wasteland of England. Speed was everything.

It was for that reason that when the order came an hour later, via Captain Kelly, from General Sir Stanley Formley-Higgs with orders for Major Winter to come 'up there' on the first morning shift of shuttles and enjoy a week's leave. Winter raised his eyebrows in astonishment. He was not only surprised but angry. He had too much to do to take leave.

"What the devil does this mean?" he growled.

"Oh, that," said Kelly mysteriously. "That is my doing. I took a long shot and hit. I signed your name to the application."

"What!" stormed Winter, "at a time like this?"

"Take it easy and listen." Kelly dropped his voice and took the precaution to go outside and take a turn around the tent to be sure there were no eavesdroppers.

"I have just now been sent down here to stay. But friend Snyder is still 'up there', ostensibly seeing to the final touches on the number two machine. Every day he goes off to Clydebank, where it is building but I had my men tail him repeatedly. He doesn't go to Clydebank often. Usually it is to Edinburgh where invariably he has shaken his trailers.

"He knew he was being followed and squawked to GHQ—said it was a slur on his honor. So they telegraphed me to lay off and sent me down here. I don't like it. I tell you, there is something about Snyder that smells."

"What has that got to do with my taking leave?" demanded Winter. "I'm no sleuth. If your men couldn't tail the guy, how—"

HE broke off questioningly. "He knows I'm off the

case," said Kelly, and Winter was impressed by his

earnestness, "and he is not so likely to be suspicious

if he bumps into you. You can go and come with a

freedom I never had. Maybe the brass-hats know all the

answers, but I won't be easy about this show of ours

until I know why Snyder goes to Edinburgh when he says

he goes down the Clyde."

"I see. What else have you got on him?"

"I went into his room one day and noticed he suddenly clamped his left palm shut. I got him excited and he began gesticulating. I finally had a glimpse. His palm was plastered inside with lampblack and tiny specks of unburned paper."

"Oh." said Winter, comprehending. "He'd just burned a secret message."

"Exactly. I tried to trace that but all I could learn was that a porter had brought it from a dirty tavern called 'Jock o' the Heather' in Edinburgh. You'll find it in a twisty lane in that run-down district behind the Castle. It's a dive, the sort of dump you wear old clothes to and leave all but your silver money at home. Now, if a fellow with nothing to do, like a soldier or sailor on leave, should decide to go there and hang out..."

"I get you," said Winter slowly. "You want me to spend my week's leave haunting this joint, trying to get the lowdown on Snyder."

"Yeah," yawned Kelly. "And a week's fling after this grind won't hurt you, either."

"Done," said Winter, because he had never ceased to wonder over the subtle change that had come over Snyder since that first day in London.

FINDING the "Jock o' the Heather" was not such a

tough assignment. Winter simply prowled the district,

exploring the maze of lanes and alleys, until he

stumbled upon the tavern, and a miserable, dirty place

it proved to be.

A slatternly barmaid was presiding when he entered. She regarded him with obvious disapproval, spilling half his ale when she served it. But he pretended to be half-tipsy, appeared not to notice, and wavered off to a nearby dark booth to consume the bitter stuff.

He stayed all afternoon, even feigned sleep for awhile, holding his head down on the stained, black old table. Later he appeared to revive and had a drink of whiskey. After a little jollying and some mild flirtation, the bar girl relaxed her hostile attitude a little, and a couple of bluejackets from a cruiser laid up at Rosyth joined him in his booth. Thus, he became accepted as a respectable barfly.

It was not until the fourth night of his leave that he saw or heard anything of interest. By that time the habitues of the place had pegged him as an U.S. sailor from whom they could cadge occasional drinks. His speech was so broadly American, and his habit free but not lavish of spending, that he was unmistakably stamped as a friendly outlander. Whatever the occupations of those who frequented the place, they had come to feel that he was a stray of no consequence to them.

By the time that fourth night rolled around, Winter was moodily doing nothing but sitting in a black corner, guzzling booze and thinking of Frieda behind his newspaper.

Then his vigil was at last rewarded, and the hand that held the edge of the evening paper trembled just a little.

On the other side of the room, in another booth, sat Snyder. With him was a rough-looking civilian Winter had never seen before. Snyder himself was in civilian clothes, despite regulations to the contrary. He had been granted a colonel's commission, out of gratitude for his marvelous invention.

They were talking earnestly in low tones.

Winter noticed that though the place was fairly crowded and many drinkers were standing, none of the usual hangers-out made any effort to occupy the two other empty seats in Snyder's booth.

Winter shifted his position so he could peek between the chairs and see beneath the table, taking good care at the same time to keep his own face partly shielded by his newspaper. His neck was stiff and his patience threadbare by the time he saw what he waited for. Two hands stole forward, met on touching knees. Fingers wriggled and something white and flimsy passed from Snyder to his companion. That was all.

Shortly thereafter Snyder got up, stretched and yawned elaborately, and left the place.

Winter waited a discreet ten minutes, then called the girl to settle his reckoning. Snyder's companion seemed to have the same idea and at the same time. But Winter got the worst of it.

The barmaid was maddeningly deliberate, and the other man beat him out the door by a full minute. When Winter got out into the black street there was no one to be seen in any direction.

A swift run to each of the adjacent corners revealed nothing. In a darkened city and in the rough, cobble-paved alleyways that twisted and intertwined like the snakes on the Lao-coon group, finding a man with a minute's start was a sheer impossibility.

Jack Winter sighed and gave up the chase.

THE next morning he stayed at the base at

Callandar. In the afternoon he strolled through

the forest and watched idly as the workmen loaded

machine-guns and ammunition into the shuttle spheres.

A few of the motor-barge engines were beginning to go

down.

Within another two weeks, the expedition could begin its trek to primeval Germany.

He encountered Colonel Snyder, standing near the number one Class-A machine, which had been used for the single trip to the year 3,000 B.C. The inventor was scowling at it as in deep meditation, the outcome of which he did not like.

"Big night in town last night, Colonel?" asked Winter casually.

Snyder wheeled, still scowling. Then he smiled in an oilish fashion.

"On the contrary," he replied, with a remarkable show of good will for him. "I wish I had. But I was held up the whole day long by those Dummköpfe—those dumb-bells at Clydebank. They are taking an insufferable time to assemble my other machine. Claim that tungsten is hard to get now, and that the government has shut down on iridium. It may be weeks before they deliver it. I was so tired when I left that I took a room in a Glasgow hotel and spent the night there."

"Too bad," commiserated Winter. "I had better luck, myself." The other leered understandingly, then stalked away. Major Jack Winter looked after him, and his lip curled.

"You dirty liar," he was thinking. "Now I know you smell!"

JACK WINTER turned in that night, still debating just what further steps he could or should take. Officially his hands were tied. He finally dropped off to sleep with the problem unsolved.

It was well past midnight when the air raid siren sounded. But it was too late to drive the raiders off, for the Nazi pilots had a perfect picture and understanding of their objective. A steady droning roar furnished an awful obligato to the detonation of bursting bombs and the hammering of ack-acks. The bombs fell like rain, and the effect was devastating, soul-shattering—and deadly in the uncanny accuracy.

Great trees were uprooted, splintered to fine shreds and flung about like match sticks. Buildings were ignited by incendiaries, springing into full flame as though they had been previously soaked with oil. Fires lit simultaneously at a hundred places. Terrific, blinding, destroying concussions swept the camouflaged forest area in every direction. Bugles blared, men ran for bomb shelters, the antiaircraft guns hammered away. But it was futile. This base had depended more on secrecy and camouflage than armament and RAF units for safety. The accuracy of the raiders was uncanny; the havoc and carnage were awful.

Jack Winters staggered awake, blinking. Callandar Base was being blasted into ruins around him. If the attack kept up another ten minutes nothing would be left of this vital surface base. But how? Then Jack Winter had a wild thought. Could this bombing raid be the result of that paper he had seen Snyder slip to the ruffian in that Edinburgh tavern? But that didn't make sense. Snyder was here, too. Would he have risked his life in such a mad scheme?

The idea was preposterous. It didn't fit at all with Snyder's original plans to enable England to execute a huge military maneuver by way of a Time Column.

Hastily Winter pulled on his clothes and ran out into the lurid night. One place was as safe as another, and he had to see what damage was being done. In a minute there was respite, as the second wave of bombers passed over. Then Winter managed to get on into the forest.

Already the damage was immense. It was easy to see. Even the power house was burning brilliantly. In another area the flaming general storehouse gave a terrible illumination. A crescendo of noise overhead warned of the coming of the third and final flight of destroyers.

Winter ran past the site of the propulsion rings where a source of the shuttles had been in the process of loading. The spot was hardly recognizable. The rings had been hopelessly warped or torn apart and flung in every direction. Only shapeless, twisted metal and yawning, smoking craters marked the place from which Main Base had been fed. Groaning aloud in his anguish. Winter found temporary shelter under an overturned tank body.

Winter ran past the site of the propulsion rings,

which were now only shapeless, twisted metal.

As he cowered there, stopping his ears against the deafening crash of the bursting, rending bombs, the full enormity of the catastrophe came to him. This meant that all the assembled equipment here was lost, and to figure the correct inventory and await its replacement would mean all sorts of delay. And to Winter delay was maddening.

He wanted to drive ahead, to get to Germany—to avenge Frieda Blenheim and all of suffering humanity that had felt the blight of that same withering hand of the demon.

Nor was this all. The rate of the invasion of the Time Column into modern Germany had been cut in half. For the rings were practically irreplaceable. Worst of all was the fact that the enemy had smelled out this base. This raid was of the magnitude of that one over Coventry—and on an innocent looking forest. The Nazis knew. And there would be other raids.

He caught sight of a figure skulking in the trees ahead, darting occasionally from one to another. The figure was tall and spare and wore the jacket of a colonel. It was Snyder, and the man was sobbing in his rage.

Winter sprinted after him and was almost on him when he saw him step out from under the deceptive shelter of a tree and shake his fist angrily at the planes in the roaring heavens. Then he ran on, never seeing Winter.

Winter, puzzling over this queer act, followed the inventor. He stumbled and fell. He scrambled to his knees and saw that Snyder was making for the Class-A Time-traveler, which by some miracle had thus far escaped destruction. Winter grabbed no the bar of iron that had tripped him and ran after.

He was not quick enough to overtake his man before Snyder reached the machine. Snyder climbed in and began closing the door behind him. Winter thrust the iron bar forward and inside far enough to prevent its being shut. Snyder tugged and swore, but the door would not close.

"Not so fast," shouted Winter. "I'm going with you."

Snyder recognized him and surlily opened the door. He looked not only angry but frightened as he closed the door and set the travel lever in a notch. Then he reached for the starting button.

"No you don't," snarled Winter, and his fist landed clean on Snyder's jaw.

The thin man went down, out cold. Winter glanced again at the travel lever. It was in the third notch, not the first, which would have stopped them at Main Base.

He changed the setting, and then, as the inferno of explosions recommenced outside and successive concussions rocked the ship, Winter pressed the button himself. The machine vibrated sickeningly, and then all was quiet. Nineteen forty-one was five thousand years in the future.

Snyder was coming to. He dragged himself groggily up onto an elbow, then sat up and began to rub his jaw.

"Fool!" he growled, "I was trying to save the machine, and you struck me—your superior officer!"

"Yeah?" was the answer. "It may interest you to know that I was in the 'Jock o' the Heather' last night."

"So?" said Snyder, regaining his customary calm and speaking quite smoothly. "Are you intimating that I was there, too? That, my friend, is something you cannot prove."

"Neither can you prove I struck you," was Winter's quiet rejoinder. "Just what is your game, Snyder? You are of German ancestry. I know. But you voluntarily contributed your invention to Great Britain."

"They why do you question me?" said Snyder haughtily.

And Winter had not the answer to that one.

There was a bitter and hostile silence between them as they walked across the field at Main Base toward the General's quarters. It was near dawn when they got there, but they woke him up. He received them sleepily, sitting on the side of his bunk and running his hands through his tousled hair as they talked.

Snyder, as his rank permitted, made the first report. He stated simply that there seemed to have been an unexpected chance air raid and that his only thought was to save the invaluable Class-A machine from a bomb hit.

"That is a lie," blurted out Winter, furious at the casual manner of the other's report. "It was a devastating, planned raid, with hundreds of planes coming over in at least three waves. As nearly as I can make out there is nothing left 'up there'. There has been treachery, sir, but I am not prepared to say from what quarter."

"Ah. well," said the general, yawning, "those things happen in wartime. We cannot always have smooth going. There is nothing we can do about it tonight. Tomorrow we will take it up in council."

WORREL lay back on his bunk and pulled up the

blanket, signifying the interview was at an end.

Winter bit his lip. There seemed nothing to do but

withdraw. Snyder saluted stiffly as if to follow.

But when Winter got outside and looked around, the

inventor was not with him. Winter glared at the door

venomously, shocking awake the drowsy orderly who

stood before it.

"The senile old fool!" he said to himself. "Why did they have to drag a man out of retirement to head a jam-up expedition like this? He's the uncle of some Lord Something-or-other on the distaff side, I suppose."

He listened for a moment, but all he could hear was the faint mumble of voices. He could not guess at what Snyder was telling now and he had no pretext to re-enter the place. He turned dejectedly and went to his own quarters where he related to Kelly all that had taken place.

"It's tough," agreed Kelly, "but Snyder's position seems as impregnable as his actions seem impossible. My fingers have been slapped, and so will yours be if you have nothing more positive to offer than this. We have a couple of bits of uncorroborated circumstantial evidence and a flock of vague suspicions. GHQ believes in the man, so does Sir Stanley, and reason says we ought to. So unless we can pin him down with cold facts we're licked before we start."

Winter wearily pulled off his blouse and made ready for bed.

"We've got odds enough to fight on this stunt without having to deal with sabotage and favoritism," he complained bitterly. For two cents I'd—

"Skip the two cents and come to bed," advised Kelly. "One stink is enough, and tomorrow is another day. We've got the guy with us back here now. All we have to do is stay on his trail and not tip our hands any more than we have. Sooner or later we'll trip him up if he is guilty."

The morning's conference was a stormy one. The more the problem was discussed the more acute it appeared. Most of those present agreed that the intensity of the raid was proof that the Nazis knew of the existence of the base. They could be expected to follow it up with others at definite and regular intervals.

As long as these persisted, it was a reckless waste to send up units of the time traveling equipment. For the shuttles would be useless without propulsion rings to send them back, and all those left in 1941 had been destroyed. Even if the B.T.C. should send up some of their own sorely needed units to replace them, a topside power plant would have to be rebuilt.

"I can take the Class-A machine and go up to reconnoiter damages," offered Snyder.

"No," objected Winter, speaking out hotly despite his relatively junior rank. "It's time capacity was only fifty thousand years and we have already used up fifteen. If we use another ten now, and ten later, we will have only enough to make a single reconnaissance to Berlin when we get there. The extra trip you propose would use up our margin of safety. As much as we dislike it, we must wait—or otherwise go on as we are."

Several of the senior officers nodded in agreement with him. He listened with grim satisfaction as the vote was taken and it was decided to wait at least a few days for a possible contact from 'up there'. Perhaps not all the rings or power lines had been destroyed. Perhaps the second Class-A machine would be finished soon. Meantime he watched the sour visage of Snyder, who clearly did not relish having his proposition turned down.

MAJOR WINTER by that time realized keenly how silly

and baseless his and Kelly's suspicions of Snyder must

seem to those in authority, but he was still convinced

that the man was doing everything he could to wreck

the B.T.C. He did not mean to let him slip away until

he had solved the mystery. Winter leaned over and

whispered to Kelly that hereafter they must keep a

sharp watch over the parked Time-Traveler, and the

intelligence officer nodded grimly.

The council went into a discussion as to ways and means if it were found they were cut off indefinitely. Winter sat staring at the table, and a tumult of questions kept plaguing him.

Snyder had invented the machine. Snyder had sold the War Office on using it. Snyder had been commissioned and sent along with the expedition. Then he had subtly changed his attitude. He went off on strange, secret trips to dark rendezvous. He sent and received notes that had to be burned. Winter was convinced that he had had prior knowledge of the air raid and had tried to escape it by jumping back in time—not to Main base, but beyond. Now he was trying to duck again. Why?

If he had been loyal in the beginning, which was obvious, what had brought about the change? Threats? Bribes? The Gestapo was skillful in the use of both. Yet if he had been a Fifth Columnist, why had he given Britain so unique and valuable a weapon of war?

Was it simply to divert and waste the rare metals so sorely needed elsewhere, not to mention the other stores and equipment and men employed? That did not make much sense either. It was too cheap a price for so epoch-making an invention.

A deep frown furrowed Winter's brow. His mind began to play with a new theory. Supposing Snyder was really a Nazi agent, could it be that the invention was a German one which had been thoroughly tested and found to contain secret defects that would prove fatal in the end? It might appear workable and pass all superficial tests, and the British could be expected to snap at it as a golden opportunity. They would squander men and invaluable material on it only to lose them. This was a plausible theory, another example of the diabolical cunning employed by the Nazis in international intrigue. Yet Winter knew he could not prove a single item in his indictment.

"Why do we have to sit here and twiddle our fingers?" General World was demanding. "If they have smelled out the topside base and blasted it once, they will do it again. We can send up half our rings and reestablish the shuttle, but if they blast those, where are we? With a quarter of our Time equipment left, I say forget our losses and go ahead with what we've got. We have all our men, our guns, ammunition, and the bulk of our supplies. There are trucks and tanks and gasoline to run them."

"Can tanks swim, or thousands of tons of food fly?" asked the Naval aide caustically. "Where are our ships and the engines for them? They were next to come down. Now they are gone."

"We can build ships," shouted Worrel. "Like the Vikings did!"

"Out of what?" snapped the Naval man. "The only trees in this country are scrubs. We found that out when we went to build our docks."

There was a dead silence. Then:

"We'll wait for one week for orders from up there," ruled Worrel. "Then we make our own plans."

IT was just after four in the morning when Kelly shook Winter into wakefulness.

"You take over now, so I can grab a little shut-eye before breakfast," said Kelly softly.

Winter sprang to his feet and put on his coat and cap. He checked his automatic and saw it held a full clip. That he dropped into its holster and then slid out into the still black night. As he groped his way to the Time-Traveler he became aware of a ruddy flickering reflection from the curved hulls of some nearby shuttles.

Just then he heard distant voices yelling, and the clanging of an iron bar against a metal plate. Fire! As he rounded the Time-Traveler he saw where it was—the main storehouse had flames belching from one end of it. As he stared in sick horror it seemed to burst into blaze all over, and five seconds later was enveloped in raging fire from sill to ridgepole.

His first instinct was to rush toward it, but he checked it. For an instant he was torn between his obvious duty—to take charge of the fire-fighting party first to arrive—and his self-imposed task of guarding the Time machine. It was a hard choice, especially as he saw the grass catch fire and waves of flames run along the ground toward other buildings and shed. But the alarm had already been given and men by the thousands were pouring out of the barracks and onto the scene.

WINTER heard running footsteps behind him. He

turned to see a slender form leap in through the door

of the Traveler. Without an instant's hesitation

Winter made two tremendous leaps and dived through the

door after him. He stumbled and struck the slick deck

face down and slid entirely across the cab until he

brought up against one of the power units.

Stunned, he heard the door clang shut and experienced the momentary nausea and uncertainty as the machine launched itself through time. By the end of the five seconds Winter was on his feet and facing Snyder. His automatic was out and covering the inventor.

"Well," he said harshly, and his trigger finger itched to squeeze the steel under it, "you didn't get away with it."

Two tremendous explosions outside rocked the Traveler, and debris pelted its hull. Six or eight others followed in close succession, but farther away. Winter knew without being told what was happening. They were back at the old base in 1941, and it was being bombed again.

"General Worrel sent me to report the fire and ask for orders," snarled Snyder.

"Quick work," was Winter's sarcastic answer. "I'll deliver that report and get the orders. Then you and I will go back together."

He bound Snyder to a steel frame, taking no special care to be gentle as he twisted the heavy wire about his ankles, and wrists. He lifted Snyder's keys and snapped the lock on the control lever. Ignoring his captive's angry protests, Winter pulled the port open and looked out on an almost unbelievable scene of desolation.

Where once a sheltering forest had stood was only a churned waste of torn earth and blasted rock. What had been a bustling military base was no more than a welter of bomb-craters. Except for shapeless bits of metal and scattered human fragments, there was no sign that the place had ever been visited by man. It was full dawn by now, and as far as Winter could see the harried area stretched for miles. But the sky was clear of planes. That last stick of bombs must have been the parting gift.

SUDDENLY, as if materializing from thin air, a

steel-helmeted figure rose from the ground close by.

At first he scanned the heavens, then looked at the

waste about him. His eye lit on the time machine, and

he trudged through the loose earth toward it. Winter

saw he wore a Lt. Colonel's uniform and the special

badge of the GHQ.

"Thank God, you've come. Major," exclaimed the officer as he approached. "They thought you would, sooner or later, so they've kept me here in this dug-out waiting for you. We're the third on this detail—all the others were wiped out. The Huns come over every four hours, day and night. It has been hell."

He plucked a sealed envelope from an inner pocket.

"For your general. You fellows are to make your way to Berlin as per plan with what you've got. Under no circumstances try to come back, as we cannot maintain this place any longer. Later we will send you the final plan. By the time you are set and ready, the number two machine will be done. Good luck and good-by."

The colonel stuck out his hand, but Winter spoke rapidly for two minutes, sketching out what he knew and suspected about the inventor Snyder, concluding with the story of the fire, now raging "down below."

"Looks bad, I must admit," acknowledged the colonel. "I'll report it, and no doubt Intelligence will have another look."

"Thanks," said Winter laconically, and gripped the hand in farewell.

In a matter of seconds he was back on the plains of prehistoric Scotland, but the total elapsed time since his departure had been close to an hour. In that time much had happened. Winter opened the door and was aghast at the size of the conflagration. The rows of storehouses had already been consumed and were piles of glowing coals.

Now the big storage tanks were afire—fuel oil, lubricating oil, and gasoline. Heavy clouds of dense black smoke obliterated half the sky. There were acres and acres of black stubble where grass had been. Ten thousand sweating and grimy men were busy fighting the blaze, but the huge reserves of the Time Column had been wiped out.

Winter started away from the machine, still leaving his prisoner behind him. He saw Kelly staggering toward him, and he did not recognize the captain at first, for his face was covered with soot and his uniform resembled nothing but old rags.

"Good Lord!" groaned Winter.

"Let me break it to you gently." said Kelly panting. "As you see, everything—or almost everything—is wiped out. The old man is hopping up and down like a pea on a hot griddle. He's yelling for your blood. You weren't in your quarters and you weren't at the fire. Snyder has been filling him full of stuff."

"Snyder!" said Winter contemptuously, jerking a thumb toward the Traveler door. "Go in and have a look. We've got him. He set the fire, and I nabbed him in the act of making a getaway. Come on. Help me untie him and we'll take him straight to the old boy. This thing is going to be settled now."

Kelly looked at him in blank astonishment.

"Don't you understand, Jack Winter?" he pleaded. "Snyder is the fair-haired lad. He's got a pre-arranged alibi for everything."

"Come on," said Winter grimly. "My colors are nailed to the masthead."

Kelly shrugged, and complied. With their sullen prisoner they strode over to where the angry old general was pacing back and forth and cursing a blue-streak at the general incompetence of every man in his division. When he finally paused to look up at the three approaching officers, one marching with hands upraised and a pistol at his back, he was purple.

"Stop that nonsense!" he bellowed. "Winter, hand that gun to my adjutant. Snyder, come here and tell me what all this is about."

The general almost choked with rage. Snyder dropped his arms to his side. When he spoke it was quietly and with restraint, as if in sorrow, not anger.

"As you remember, General, I called on you late last night and told you the peculiar circumstances about my relations with Mrs.—our mutual friend, let us say—in Edinburgh, which I believed explained fully the absurd suspicions of Kelly and Winter." He coughed discreetly and shot an exulting sidelong glance toward Winter, who was boiling.

"Oh, quite," grunted the general. "The confounded asses!"

"After that, I warned you of the extremely vulnerable position we would find ourselves in if by any chance our stores should be lost by theft, storm or fire, and recommended the issuance of orders today for redoubling the sentries?"

"Yes, yes," said the general impatiently. "Of course. I remember. We talked most of the night."

"I also informed you that these two officious young men had set themselves as custodians of my time machine, which, in the event of any such catastrophe might prevent me from going immediately back to our old base and reporting the matter."

"You did." assented the general, glaring at Winter and Kelly. "And I told you to ride over them roughshod and go. It was then the fire broke out."

"Exactly," said Snyder with perfect suavity. "I went, but Winter followed and held me up at the point of a gun, making me a prisoner. Now he has the effrontery to charge me with starting this fire."

"Did you ever hear of those cigar-size, delayed-action incendiary bombs, General?" burst out Winter, unable to restrain himself longer. "He could have sprinkled them about yesterday and still have spent the night—"

"Silence!" roared the general. "I'll have no more of this. Winter, you are relieved from all duties. You are under arrest."

"No. General." protested Snyder, as if the matter were no more than a trifling annoyance, "I am not vindictive. I think perhaps Winter has too big a job for him and that he and Kelly suffer delusions, but I see no point in persecuting him. I thing he has orders for you."

Winter, in the excitement, had forgotten about those. Now he presented them in stony silence. The general tore them open and read them hurriedly.

"Damnation." he growled, "what a pass!" He scowled about at the still raging fires and the tired, baffled men fighting them. To Winter and Kelly he gave the curt order. "Get down there and help. I'll take this mess up later."

THE next council of war was less stormy. They could

not go back. Not only did their orders flatly forbid

it, but if the Germans kept up their bombing it meant

suicide. They could not stay where they were, for

there were no trees for timber. There was no local

population to press into service.

To scatter over Britain—and that is what they would have to do to survive—meant they would soon degenerate into a race of savages. They might exist as isolated and widely separated small groups of hunters, but in the end they would surely die. Moreover, most of them were itching to get on to Berlin.

Someone remembered the Winter-Kelly report of a previous race. Those two officers, being out of grace, had been excluded from the conference. Now they were sent for. Winter did the speaking, confident and unregenerate despite the rough official handling he had had.

"Yes. We were told that in former ages this land was inhabited by giants and gods and that there were castles and towns. That means people, flocks, perhaps farms. They had ships. I have looked over the salvage from the fire and I find that our stock of flour is little damaged and that we have several hundred tons of ham and bacon left. Some of it is charred, but most of it is edible.

"Hundreds of drums of gasoline were recovered from the tanks of trucks, tanks and tractors. We can abandon most of those and use the gasoline to propel the few trucks we need to carry our guns and ammunition. In that other age we may find horses or oxen to haul the trucks when the fuel gives out. Let's quite wasting time here and jump back another five thousand years into the past."

A babble of voices arose. Some approved, others not. The daring proposition was argued pro and con. In the end the pros had it. They would go back. A deeper detour into the past seemed to be the only feasible course open. They would split their supply of repulsion rings and set up a new shuttle, this time to the year 8,000 B.C.

Worrel objected it would be a shot in the dark. Someone should go ahead and scout. That brought the thing back fairly into Winter's and Kelly's laps. They had interviewed the solitary shepherd of this age; hence, they were the only men competent to deal with the antique languages. They were chosen to lead the punitive expedition deeper into the past.

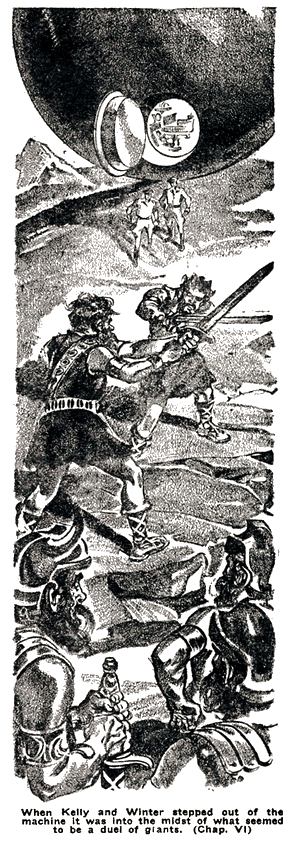

EIGHT thousand, B.C.! When Kelly and Winter stepped out of the machine it was into the midst of what seemed to be a duel of giants. Two tremendous, red-bearded men stood facing one another on a spot about a hundred feet from the Time-traveler, each raining blows on his adversary with a long double-handed sword.

Their only garments were kilts of pelts and rough sandals. Despite their eight feet of height and immense bulk, they danced about like fencers, parrying the blows that were falling upon them with a swiftness and dexterity that was amazing. A group of their kind stood beyond them, looking on.

There was a shout of amazement and the battle stopped abruptly. Both men turned to stare at the strange globe that had materialized out of thin air. Both bellowed like bulls and fearlessly charged forward, waving their ruddy bronze weapons in circles above their heads.

Kelly tried in vain to indicate their mission was peaceful, but the giants continued their charge. The lust for murder was in their red eyes. Major Winter did not hesitate a moment. His face stern and cold, he whipped out his pistol and fired two shots point-blank. The human behemoths pitched headlong forward, their broadswords flying from their hands and clanging against the hull of the Time-traveler.

Winter stepped over the bodies and, still holding the pistol ready, regarded the awe-struck group of giants. They had started to follow the charge, but had stopped and were gazing open-mouthed at the sight before them. Their two greatest champions had been slain by this pale wraith of a pygmy who had appeared from nowhere with no more formidable weapon than a black stone held in his hand! It was magic!

"Now talk to them," ordered Winter grimly. "They will listen. But don't try to sell them the idea of time travel. You'd better just say we are wizards from beyond the western sea who have come to call on their king. Find out where he hangs out. While you are palavering, I'll have Miller and the boys put our little scout plane together."

Kelly picked out the most important looking of the surviving giants, a big brute a head and a half taller than himself, and began talking. He found to his relief that he had less difficulty reaching a common tongue than he expected.

Languages change vastly in the course of a few thousand years, but this primitive one seemed nearly static. It resembled closely the jargon of mixed Gaelic, old German and early Norse that he had used on the shepherd met in 3000 B.C. By the time the plane was assembled he had learned a good deal.

"I think these fellows are forerunners of the Vikings," he said to Winter, as the giants crowded around to gape at the plane. "You remember the shepherd said that his forefathers immigrated to the northland after that great plague a century or so before his time. And from the names they have, I take it they also represent the origins of the later Nurse mythology.

"This guy calls himself Thrym. The king's name is Skrymer, and he lives in a castle called Yottenholm. That must be at Stirling, from his description of it. Legend eventually made them into fearsome giants, though you can see for yourself they are ordinary men—just big."

"Yeah," grunted Winter. "Well, let's get going. Do you think you can coax your friend Thrym into the plane? It may save more fireworks when we get to Yottenholm. You and I can straddle the fuselage and hang on to struts."

Thrym was delighted. He had admired the "chariot" in the early stages of its assembly and had offered to send for a team of oxen to draw it. When he saw how light and easily managed it was, he told a gang of his retainers to do the pulling instead. But the addition of the wings mystified him. He complained they would catch on bushes and trees.

THEY wedged him into the seat beside the pilot and

strapped him in. He started violently at the first

roar of the engine, and his minions scattered like

frightened deer. The sudden jerk of the swift take-off

run and the almost immediate soaring into the sky

reduced him to speechlessness.

He stared in glassy-eyed silence as they circled Stirling Rock and watched with horror as the ground rose up to meet them.

"Now I know you are truly wizards." he gasped when the little machine bumped to a stop on the plain in the shadow of the rock. He tore away his fastenings and got out, visibly shaken.

"I will go ahead and prepare the way," he added, after a moment. "It is a long, hard climb. Skrymer will send down litters and bearers... unless it is your wish to ascend by some strange magic of your own."

Winter glanced up at the sheer cliff. The place was an inland Gibraltar, straight up on three sides, approachable only by a steep hogback ramp on the fourth. Kelly gave vent to a low whistle, and Miller groaned.

"We will await Skrymer's hospitality," Winter told the giant gravely.

Skrymer's hospitality proved hard to take. His castle consisted of a single immense room. Its walls were of stacked field-stones and boulders chinked with mud. The roof was built of massive timbers piled across whole tree trunks used for beams. There was no opening anywhere except for the great door.

The gloomy interior was filled with the smoke of cooking, mingled with the stench of carrion, and flavored slightly by the aroma of dogs, horses, cattle, and unwashed human bodies. It was lit by burning wicks laid in seashells filled with melted fats. The floor was ankle-deep in rubbish— bones, ashes and refuse dominating. In one corner was a middenheap.

The banquet their host gave them was particularly revolting. The food was prepared before their eyes, beginning with the first step of driving eight oxen in and slitting their throats with bronze knives. They were then quartered and roasted on spits in pits alongside one wall.

The table was an elevated trough along which the diners stood, snatching at the meat with their hands or cutting off hunks of it with the bone daggers they wore stuck in their waists. They washed down the food with a frothy drink that looked and smelled like sour milk, but tasted like low-grade Ozark moonshine. There was neither bread nor vegetable other than a bitter root that had some resemblance to a potato.

When the shepherd of 3,000 B.C. had described his predecessors as fierce and turbulent, he had been accurate. These men were all noisy braggarts, and fights broke out frequently. They fought in every conceivable way—with swinging ham-life fists, by grappling and clawing with bone-breaking wrestling holds, with their knives of stone or bone—even with their bronze broadswords.

Three times during the night the servitors had to bring rawhide ropes and drag corpses from the hall. Yet the other feeders at the trough scarcely seemed to notice. The boasting conversation went right on.

Winter and Kelly stood beside Skrymer and talked to him. They watched in wonder as he stuffed huge handfuls of dripping, sizzling meat into his rapacious mouth. His capacity as a drinker was incredible. He would toss off the vile mead a quart at a time and never turn a hair. Two sips of it made Winter's head swim and he resolved to risk no more. Skrymer talked freely and boastfully.

Oh, yes, he knew the great land across the water to the East. There was much loot to be had there. He raided it every few years. That was where they obtained the rare bronze for their swords. They also got a mysterious substance that had certain limited uses—cloth, Winter discovered. It made better sails for the ships than skins.

Ships? Yes, he had ships. Many of them. As many as there were hands and toes on the three of them. His gillies were building more. The perils of the sea were great. On every foray they lost many of their boats. That was because of the serpents and great monsters that dwelt in the depths below.

Would he consider an alliance with the wizards and build additional ships for them? He would. He guffawed and said they looked like very puny men, but he had been told they could fly like birds. Skrymer had told moreover how one of them had slain his two best warriors merely by blowing his breath on them. A gift of magic like that ought to be helpful in getting past the sea monsters.