RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

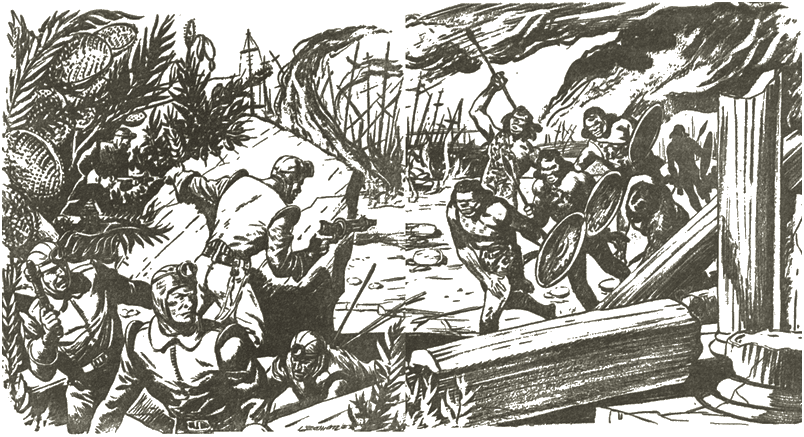

Thrilling Wonder Stories, August 1942, with "Land of the Burning Sea"

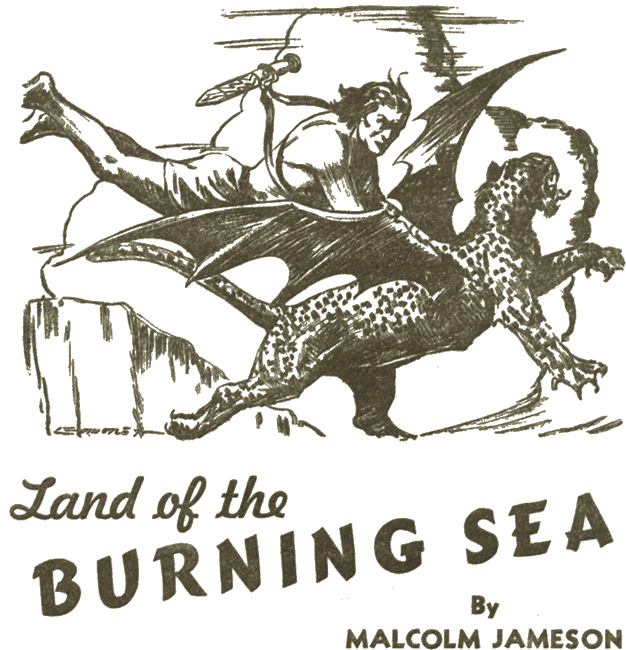

Prescott leapt astride the frantic flying leopard's back.

The World Becomes So Perfect in the Distant Future That All Joy Is Lost—and

It Takes a Young Barbarian to Lead Humanity Back to Freedom and Happiness!

THE cloud-filtered sunshine glinted softly off the superb bronzed shoulders of the young barbarian crouching on the ledge. It was a narrow ledge, high on the wall of one of Venus's deep mountain gorges, and was slippery with moisture, but the surefooted young tribesman did not seem to mind that. His eyes were narrowly probing the driving mists that swept the canyon below.

Once he let his hand stray down to touch the hilt of a skinning knife stuck in his girdle as if to make certain just where it was. Then he crouched lower, tense and eager. For already his keen ears had picked up sounds of approaching game, hidden by the swirling mists below. What he heard was the drumming of beating wings and the curious mewing cries of a flock of Venus's flying leopards—the fierce and untamable pterofelidae.

A moment later they broke cover, climbing now out of the fog and battling against the gusty winds of the gorge. "Wild Hal" Prescott thrilled at the sight, for to bring down one of those savage winged creatures meant more than mere meat and a good pelt—it meant a good fight, and there was nothing in his wild, carefree life that he loved better than a good fight.

His gaze sharpened, for he was shrewdly estimating the erratic approach of his prey. Then he chose one for his own—a magnificent animal, lithe and strong and beautifully spotted. It was winging its way along the face of the cliff a little below him and some distance out over the canyon.

He gathered himself tautly for the leap. Then he sprang—sprang outward in a flat, horizontal dive, with his empty hands outstretched before him. Out and down—the timing and muscular coordination must be perfect, for to miss by so much as a hand's breadth would plunge him headlong down through the mists onto the cruel crags below.

The leopard sensed his coming and swerved, but Prescott gave a twist to his flying body and swerved, too. He knew what to expect of the beast. He struck even as it was in the act of turning, and his strong hands clutched a wing.

In another instant he was astride the cat's back, gripping its flanks with his knees and its tough throat with his hands. The animal snarled a frantic scream, and down they went in a smother of beating wings, snapping jaws and slashing talons, twisting and turning as they fell.

Wild Hal hung on desperately. He managed to loose one hand and pluck the knife from his belt, but the time for the kill was not yet. To kill the cat in mid-flight would be to lose the support of the flailing wings. The death stab must be withheld until just before the tiring leopard crashed.

Prescott waited until he saw the canyon floor rushing up at them, then buried the knife to the hilt between the creature's shoulder-blades. As they struck, he leaped nimbly clear of the murderous claws and bounded to one side where he could watch as the cat thrashed out its life. When it had twitched its last, he threw its heavy carcass over his shoulder and started on the long trail home.

HAL PRESCOTT was pleased with himself, for he was the only hunter of his tribe who had the skill and the boldness to dive on a flying leopard in flight—the only way a man could approach one and not instantly be torn to shreds. His entry into the village would be the signal for a festival. That night there would be feasting on the green, merriment and dancing. By then the women would have prepared the leopard steaks and the small boys the skin. Later, after the other hunters had come in and the wineskins passed around, the dressed hide would be presented with appropriate ceremonies to the chief of their clan, Father Jedson.

At length, he came to the clearing made for their primitive vegetable patches. Beyond that, a little cluster of stone houses nestled among luxurious flower beds. Smoke rose idly from the communal kitchen hut. To Prescott's mind, it was the most beautiful of all places—colorful, comfortable and hospitable.

Every time he returned to it he was gladder than ever that he had been born a wild Sybarite, especially since now that he was a man and admitted to the tribal councils, he was learning something of the hated enemy race that lived in the lowlands.

Perfectionists, the hill men called them contemptuously, from the fanaticism with which they worshipped a god called Efficiency and strove for the Perfect Life. It was their idea of life which was so hateful to the wild men of the hills, for to them any life which was purely utilitarian and had no room for beauty, love or joy, would be intolerably drab and dull.

His thoughts were cut short by the rush of whooping children and excited women who had seen his approach. He laughingly let the small boys take his burden and carry it triumphantly ahead as the procession went on toward the houses. Father Jedson came out and beamed his congratulations. Then Prescott went through the carved portal of the chief's house and sat with him over a jug of mead until time for the festivities to begin.

It was well into the night before the merriment reached its peak. By then the feast had been finished, the crude instruments made from gourds and tough barml vine brought out, and the singing and dancing started. Wineskins lay about, and everyone was happy. But their fun came to an abrupt end. In the midst of the gaiety, a spent runner came dashing in and fell panting on the grass.

"My village," he gasped. "It's gone."

The dancers stopped in mid-stride, and the musicians laid down their instruments. They recognized the stricken man as a member of another rebel tribe living in an adjacent valley.

Consternation reigned. Could the Perfectionists be raiding again after so many generations of relative peace?

"I came in late from hunting," said the man when he regained his breath, "and found only ruins and ashes. There were no signs of my people. They are gone, too. If I had only been there earlier, I might have—"

"You would have gone also," said Father Jedson, quietly. "Spears and knives are useless against blast-guns and deadly rays. I fear your people have been carried off to Erosport for public execution. That is the accursed custom of our enemies. I know them well, I lived among them once."

It was the keen ears of Hal Prescott that first heard the strange whirring overhead. Something wide and black was slowly descending from the sky.

"Run for your lives—scatter!" shouted Father Jedson, looking up. "It is a war helicopter! They will ray you!"

THE warning was too late. There was a sudden burst of light overhead, and a green ray shot down and swept the revellers. They seemed to melt under it, slumping limply to the ground as the ray passed over them. Prescott was in the act of drawing his knife when it struck him.

To his surprise it did not pain him, for he did not know that it was a hypnotic ray. It did no more than turn his muscles to water and deprive him of all will to movement other than a languid rolling of the eyes. Like the others, he sank helplessly to the ground, utterly listless and weary.

The flying machine came down and grounded at the edge of the green. A group of armed monitors sprang out of it, led by a proctor in a glittering helmet. These at once began the systematic destruction of the village, house by house. And as they went about their fiendish work, three other men emerged from the helicopter.

They were garbed in the black robes of the Court of the Inquisition. Prescott knew that, for there were many legends about that court, a place where those who committed the deadly sin of Waste were tried and punished. For before the Perfectionist god of Efficiency, the most heinous of all crimes was a useless act. The three priests stood in the midst of the firelight and scowled disapprovingly at everything about them.

"Far worse than the other," snarled one, "a den of iniquity. Dancing, drinking, feasting on carrion! Fah!"

"With music and singing, too," said another scornfully, picking up a gambea or makeshift guitar that one of the musicians had left. He smashed the offending instrument and threw its fragments into the fire.

"Abominable, indeed," said the third of the black-robed ones. He was handling a wineskin gingerly as if it were a loathsome thing. Then he slit it and let its contents waste gurglingly onto the grass. "We have been remiss, brothers. This heresy must be stamped out, completely and ruthlessly."

The proctor came up and reported finding intricate carvings in stone over the doors of several of the huts, and carved beams within—strange useless designs of interwined leaves and berries with delicately cut birds and squirrel heads peeping out.

"Smash them! Smash them!" screamed the elder of the Inquisitors. "Oh, what villainy, what depravity. Such a frittering away of effort! We must make examples of these savages. Proctor, do your duty."

Hal Prescott looked on and saw all those things, helpless to stir a finger. He could only watch with impotent rage as they finally set fire to the houses, and then began carrying the numb victims of the ray into the helicopter. His fury knew no bounds when two undersized monitors picked him up and carried him along with the others, for it would have been but a second's work to wring both their necks if he but had his normal strength.

THE machine took off, leaving the smashed and burning village below. An hour later the prisoners were herded into Erosport's bleak jail, each staggering drunkenly, now that the effect of the ray was beginning to wear off. Prescott found he had at least a little luck. They put him in the same cell with Father Jedson.

"Tomorrow we die," said the old man calmly. "Let us hope it is by a humane instrument. They do not give quarter. They have not for several centuries—not since the rumors of what happened at Rizam got about. I know. I used to be one of them until I saw the light and ran away."

"I do not understand," Prescott burst out angrily. "Why should they persecute us? We have not harmed them. We just live in our own little valley for the sheer joy of living."

"That," said the grizzled chieftain, "is why we are punished. Our crime is to accept pleasure wherever we find it, and that, to a Perfectionist, is neither more nor less than sacrilege. Our feud began a thousand years ago, at the time of the Great Schism. That occurred following the unification of the human race at the close of the bloody Twentieth Century.

"Before then the principle of efficiency had been developed in industry and adopted to some extent by governments, but it was in twenty-one eighteen that the engineers and scientists elevated the principle to godship and assumed priestly titles. The opening of the planets to colonization by the perfection of space travel caused the idea to spread all over the Solar System. There was no escape from it.

"But there were some, such as your forefathers, who could not bear the rigid, joyless planned life of a Spartan society. They withdrew to the hills and founded villages like ours, where it was possible to really live. Subsequently, others, such as I, deserted the false civilization of Perfectionism to join you. At first the Perfectionists ignored us, but after the Rizam affair, they began a war of extermination. We were lucky to survive this long."

"You spoke of Rizam. Where is that?"

"Very far away. It is an Earthlike planet of the star Mizar, and was opened to settlement some five hundred years ago. At that time they took many of our people from concentration camps and carried them out there to do the rough pioneer labor.

"But a couple of centuries ago all communication with Rizam ceased and ships sent to investigate did not return. Many thought that there had been an uprising of Sybarites. At any rate, from that day to this the Perfectionists abandoned all effort to convert us. They killed us instead."

"Let them," exclaimed Prescott hotly. "I would rather die than lead the life of a robot!"

"Silence in the cells!" roared a harsh voice, seemingly at his elbow. "What you have said will be used against you." Father Jedson started, then laid a finger across his lips. He had lived in the hills so long he had forgotten there were such devices as scanners and microphones.

"Use and be blasted!" Prescott shouted defiantly at the unseen voice.

IT WAS no trial, but a mocking farce. The smug inspectors of the Inquisition related with something like horror the vile evidence found in the village—hand-forge, looms and spinning wheels—inefficient, crude tools. But still worse and absolutely unpardonable was the frivolous waste of effort as evidenced by the cultivated flower beds, the existence of a winepress and musical instruments. The door carvings were the last straw.

"Death," shouted the Chief Inquisitor, "I can bear no more. Death under the ray for all but those two." He pointed an outraged finger at Father Jedson and Hal Prescott, who stood together. "The old one is a renegade from our own faith. Let him die in the Thanatope."

Prescott felt the old man flinch, and knew from that, that the thanatope must be an awful thing, for Jedson had always been a man of iron. Then he heard the last words spoken.

"As for the insolent cub beside him, a special fate is reserved for him. Even after apprehended, when he should have been repentant, he scoffed at our mode of life and blasphemed against it. But first, he shall witness the elder scoundrel's death."

The monitors sprang forward. But that time Hal Prescott had not been softened to helpless jelly by any green ray. The full force of his husky frame was behind the fist that crashed against the first one's chin and hoisted him clear over the bar of justice, as those presiding there chose to call it. A second swift blow felled another, and a third was in mid-swing when a proctor went into action. His tetanizer was in his hand and he let its dreadful stream of activating rays play up and down upon the raging Sybarite. Prescott fell twitching to the floor, his muscles set in the agonizing cramps of tetany. It was more than a living man could endure. He fainted.

When he came to he was in a bare courtyard. At the far end stood a group of men, women and children—his fellow tribesmen. Beside him was Father Jedson, waiting dejectedly for the executions to begin. Suddenly, from a tower overhead, a ray lashed down—a violet one—and the group at the far end sank silently to the ground.

The ray blinked out. Its deadly work had been done in a tenth of a second. Then Prescott understood what the old chief had meant when he spoke of humane means. He turned to look at Jedson, but found a couple of monitors were already strapping him into a strange machine.

It resembled an ancient set of stocks, having a seat and holed boards in which the hands and feet were locked. But sets of wires dangled from it, and curious jars and containers sat on the platform around it.

"This, my son," said Father Jedson, as they began attaching small sucker cups to the back of his neck, and connecting electric leads, "is the most diabolic invention ever achieved. It is the ultimate in efficiency, and therefore holy in their eyes. It produces the maximum of agony at the minimum cost of energy input."

No one tried to stop him. He went on.

"A small initial current from an exciter coil gives the first painful impulse. The victim reacts and thereby sets the neural currents of his own body into great activity. If the reaction is rigidly controlled, the pain will be severe, but not unendurable. But if it is extreme, excruciating agony ensues.

"In any event, after the first excitation, the outside current is unneeded. The victim proceeds to execute himself. Whether he is to have a long, lingering death full of milder pain, or torture of hours' duration is matter for his own will to determine."

STRONG arms pinioned Prescott from behind, and despite his struggles, forced him down into a chair that had been brought for him. He was bound to it securely and bade to watch. He could hardly avoid doing that, for he was face to face with the miserable Jedson and only a few yards distant.

"Console yourself, my boy," were the old patriarch's last words, "the more I writhe and scream, the shorter will be my martyrdom. If I have the strength to carry out my will, that is the way I will do it."

The Head Proctor reached down and closed a switch. Jedson's spare body jerked madly and his face was twisted horribly. Then, as the fiery oscillations tore at his nerves, the agony of his ordeal found utterance. The old man shrieked without restraint, tearing at his bonds. Hal Prescott, sickened unspeakably, could close his eyes but not his ears. A murderous hate filled his heart, and at that moment he would gladly have presided at the execution of the whole Perfectionist race.

But Jedson could not keep it up, no more than any other man had ever done. It was unbearable, so he relaxed after a little, and sat for a long time doing no more than whimper and tremble. Then he would scream and jerk again. Hour after hour Prescott had to watch those terrible alternations until he wondered at what moment his last remnants of sanity would go. The day wore on into the night, but under the ghastly green of the floodlight overhead there was no diminution of the torture. Those who had initiated it cared not at all which way Jedson chose to conduct it. Either was the quintessence of cruelty.

It was well past dawn, and the third shift of monitors was on guard when Jedson's struggles ceased and they unloosed his body from where it sat.

"This big fellow," laughed one of them, touching Prescott, "ought to last three times as long. The old one was half gone before he started."

Prescott glared venomously at him, recognizing him. He wished now he had let go with his full strength, the day before, for it was the guard he had catapulted head over heels with his first blow. But the guards said no more—they only covered him with their tetanizers and indicated he was to follow them back into the court room.

"You have seen the Thanatope at work," sneered the Inquisitor, "you have also been quoted as saying you prefer to die rather than lead the Perfect Life. I now direct you to choose again. Conversion to our faith, or death?"

"To hell with your filthy way of life," shouted Prescott. "Death!"

"Well, well," remarked the judge, as if secretly amused. "So you really meant it. Very well, following our rule of never pampering a heretic, you shall live. Higgleby!"

A man dressed in the orange surplice of a Dean of Redemption stepped up.

"This barbarian is to be sent on the very next transport along with our own penitents, to the Indoctrination Center on Mars. There he is to be inculcated in our faith and broken to our way of life. In view of his strength and agility, he may some day make us a good monitor."

It was only the memory of the effect of a tetanizer that restrained Prescott from a fresh outburst. He gritted his teeth and followed his captor down the hall. The orange clad one did not speak at all until they were at the door of the cell.

"I am glad you got a break," he said, pleasantly, "civilized life is not bad, once you are used to it. You are young and ignorant—that is all that is wrong with you—and full of pernicious ideas."

"A break!" snorted Hal Prescott. If he could not murder, he wanted to die.

He sat down in his cell and stared vacantly at the floor. Father Jedson gone, all his tribe gone, his village gone. And he had still to live. His punishment was the severest of all.

A monitor came in and pressed a needle into his arm. Then Hal Prescott went out like a light.

HE HAD but the vaguest impression of what happened to him for the next several weeks. He knew that he had been carried on board a spaceship, and that men had come and talked to him from time to time. Nothing was said that stuck in his memory, yet he had the feeling that somehow an immense store of information as to how Perfectionists lived and what they expected had been injected into his subconscious mind.

Perhaps he had been wholly hypnotized. He was aware, too, of putting up a stout resistance to the intrusion of the propaganda. It must have been that that had prompted many painful needlings.

There was a stop en route—Grand Lunar Junction, someone said—where a batch of probationers from Earth were brought on board. They had all erred in some respect, but in the main their fall from grace was due to clumsiness or simple stupidity. Even the most devout fail at times to achieve ideal efficiency. Aside from that shadowy memory, Prescott knew little else until they let him regain full consciousness just before the transport shuddered down on backing jets into her receiving pit at Ares City Skyport.

By that time the fiery rage that had possessed him at the trial had cooled to a smoldering, calculating hatred. He had learned the futility of open resistance. Hereafter he would appear to be docile—even grateful, if it could be done—for the instruction offered him. Behind that mask he hoped to learn how to sabotage the system and avenge the atrocities perpetrated on his kind.

Consequently, when the monitors gave the signal, he went meekly with the others and climbed into the huge tractor that was to carry them across the sandy desert to the House of Penance. But it was only a seeming and temporary surrender, for the last sufferings of his beloved chieftain had burned themselves indelibly into his soul. He could not undo them now, but he would avenge.

When the tractor had lumbered over the yielding sands and drawn up at the gate of the Indoctrination Center, Prescott got out and lined up with the rest at the registration house. The others passed through quickly, as each was already provided with a fat dossier covering his career since birth. Hal Prescott was given the works.

"Hey, you, up onto the metabolometer there," called a novice in the green and white stripes of dietician. A Deacon of Dietetics looked on. Prescott did as he was told. At once his body was bathed in shimmering light and a queer feeling shot through him as the analytical machine probed his vitals.

The light faded and the machine coughed up a small white card curiously punched with symbols. The attendant glanced at it. Then he fed it into a slot and in a moment five smelly purplish capsules dropped out. He handed these to Prescott together with a small cup of yellowish, bitter liquid.

"Swallow those," he directed. "Later you will be given others as required."

PRESCOTT nearly gagged, but managed to get the foul-tasting combination down. He was wondering when they would be given breakfast, especially since he had eaten no real food since his capture. In the prison and on the ship they had fed him hypodermically.

"Listen attentively," said the hygienist, crisply. "The first day probationers come here we explain things. After that they follow the routine without further instruction. This machine establishes your metabolic rate, your total available energy, your vitamin requirements and other data.

"The card it delivers is a prescription for your sustenance for the day. It contains exactly the number of calories you will need. More would be waste. Hereafter you will visit this machine at the beginning and end of each day and do as I have shown you."

"You mean we don't eat?" asked Prescott sullenly. But as he looked at the wasplike waist of the instructor atrophied from a lifetime of pellet foods, he knew the answer. It was no.

"You have eaten," replied the hygienist sternly. "For your information it has been more than two hundred years since the great Hinkle, Archbishop of Dietetics, decreed that animal carrion and broken bits of vegetation were immoral food.

"Moreover, the synthetics are cheaper and more compact. Less time is used in consuming them, and since they are unpalatable, there is no temptation to commit the unpardonable sin of gluttony. Understand? Now go into the next laboratory for your aptitude tests."

Prescott stepped down and strode across the room.

"Easy there," called a monitor. "Cut those strides down by two inches and take them a little slower. You will get just as far and not use so many calories."

Prescott flushed angrily, but did as he was told. Now he understood the shambling gait and listless manner of the lower class Perfectionists. It was another tribute to their vile god, Efficiency. But what he was to encounter in the next room made that admonition mild. This time he was placed in a complicated contrivance called the psychometer.

The examination took most of the day, during which he manipulated various levers, punched buttons at certain signals and performed a great number of other acts under the orders of his examiners. In the end that machine coughed up a card too. The examiner read it and shook his head mournfully.

"You are a fine animal," he said, but the tone was anything but complimentary. "However, your readings show a total lack of discipline. Everything you do is full of lost motion and the amount of wasted energy you put into every movement is deplorable.

"We would not think of assigning you to work until we have taught you to stand and move your arms and legs. Tomorrow we will start you in at Motor Training, doing simple things against a stopwatch and slow motion pictures."

He made a notation on the ration card also.

"You have excess energy—too many calories," he added, "for what we want of you. We'll cut that down too."

PRESCOTT winced. It was bad enough to not have real food, but to be deliberately weakened by planned undernourishment was too much. Just then a gong began tapping.

"The hour of devotion," said the machine operator reverently. He pointed to several reclining chairs. Prescott had noticed them before and wondered about them since he had not yet heard of a Perfectionist doing anything the comfortable way.

"Lie while you listen," directed the instructor, "it saves energy. Every time the voice says 'Report!' punch the button on the arm. I warn you—if you fail, or are late, you will be punished severely."

Prescott was grateful for the rest, for the day had been a gruelling one, but in a few minutes found out that it was only another means of torture, mental this time. The voice was pompous and dry, and according to the announcement was that of Humbert, Deacon of Orthodoxy. The discourse was partly fulsome praise of the Planned Life, the rest bitter denunciation of the sinful Sybarites.

He charged they squandered their lives away in silly uselessness and were certain to degenerate into savages. It was very tedious and absurd and Prescott found himself nodding. But in a little he learned there was no evading listening. In one of his dozes he missed responding to the irregularly barked command to report, and on the instant a sharp voice rang out from another loudspeaker on the wall, "Four-eighty-seven-V inattentive—penalized by three tetanizations to be applied immediately after the lecture. For the second offense it will be double."

After that Hal Prescott listened, though to his mind what the sanctimonious voice was saying was pure drivel. It was dark when he had recovered from the painful cramps of his subsequent punishment and was led off to his sleeping cubicle. This was one of a long row of detached one-room huts whose gaping doorways opened out onto the desert itself.

As he stumbled into the place he noticed that there was no fence about the Center such as a semi-prison would have, nor were there any locks on his door. In fact there was no door at all. Nor could he see any sentries other than the monitor who had conducted him to his cell. It was a strange sort of prison—no doors, no walls, no guards. Then came the disillusionment.

THE monitor was still outside the door. Like the other instructors of that first day, he occasionally spoke, though Prescott had noticed that the older probationers went about their work automatically and in silence.

"Your cell is doorless," the monitor explained to him, "because it has been found that the desert night air is restful and healthy. But don't think that because there is no door you are free to walk out. Look!"

He reached up above his head and did something with his hand on the outside of the little hut. There was a click.

"I have set the invisible trigger rays. They interlace your doorway and the least interference with them will set off an electronic blast that disintegrates everything in its path. At the reveille signal in the morning, the current will be shut off. Then you can come out. If you try it before, it will mean sure death. Some of you fellows have used that as a way of suicide. Well, if you can't stand the speedup in the apprentice shops, that's all right with us." With that, the monitor walked away. Prescott shivered, for the Martian desert turns intensely cold the moment the sun sets. By the lavender moonlight of Deimos he could dimly make out the contents of his cell. It was bare except for a thin, limp mattress lying directly on the flagstones of the floor.

There was something lying across it, and Prescott found that to be a heavily quilted sleeping coat. He put it on and lay down on the hard mat and for a long time stared out through that doorway with its false invitation to freedom. Outside he could see the bright, unwinking stars and all the yearning for liberty which was characteristic of a free soul surged up within him. In that instant he abruptly changed his plans.

He sat up and studied that tantalizing doorway. Was what the monitor told him a real warning or pure bluff? It was some time before he hit on the way to find out. With his strong fingers he ripped the seam of his mattress and extracted a handful of the long fibers with which it was stuffed. He crawled with them to within a foot of the door and from that point he cautiously probed the vacancy immediately above the sill.

It was at about six inches above the floor that the fiber encountered the first of the unseen rays. A bolt of miniature lightning lashed out from one jamb to the other and the tip of the fiber exploded silently but with a brilliance that was blinding. For a moment Prescott sat where he was, unable to see and badly startled by the abrupt violence of the force he had set off. His trembling fingers still held the stump of the fiber, now riven to a fine fluff. The guard was not bluffing. The doorway was barred by sudden death.

IN a moment he tried again and found the second of the rays—parallel to the bottom one and a little over half a foot above it. He knew what to expect that time and was not so shaken by the swift, starlike flare. Upward he went and located the rest of the rays. The topmost one was at the level of his chin. He sat back and listened, but apparently the bright flashes he had set off caused no alarm. There was only a slight smell of ozone.

For a long time he thought over the devilish mechanism of that door and of a way to beat it. Between the upper ray and the lintel, there was room for the passage of a man's body, but there was no way to reach it. It was tantalizing. For if the rays had been concrete and visible, an agile man might contrive to crawl between them. Since they were not, it would be little short of suicide to make the attempt, as the slighest brush meant extinction.

He recalled his resolve to conform, but what he had experienced and seen that day was discouraging. They were going to rob him of his strength. Worse yet, he had observed the older probationers dragging themselves hopelessly about the place, beaten and spiritless slaves, mere automatons. In time, the system would do that to him also. No—if he was to avenge his fellows, he must be free, and the sooner the better.

Hal Prescott arose, shed his sleeping suit and stripped to his pantlets. The biting air made him shiver, but he must not be encumbered. He walked to the back of the cell and squatted, sizing up the height of the door and its invisible barriers. Then, as a check, he hurled one sandal after the other through the unguarded upper space. One went through. The other was a trifle low and vanished hissing in a burst of dazzling fire.

"Hmmm," thought Prescott, observing the penalties of a miss. But at that the risks were no greater than diving down upon a flying mountain cat. So he went into his steely crouch, and without giving further thought to its danger, launched himself into the same javelin-like flight he had so often practiced in his homeland gorges. There was a swish of air, and he felt his back-hair lifted faintly as it narrowly missed the underface of the lintel. Then he was pitching, face down, into the gritty, ruddy sand outside, to plow a foot or so onward.

Prescott rolled over to a sitting position and began picking the grit from his eyes and nostrils. As soon as he could see and without regard for the many raw spots and abrasions on his chest and thighs, he got to his feet and ducked into the shadow of his sleeping hut where he would be out of the moonlight.

He waited and listened, but there was no alarm.

Apparently his captors had full confidence in the unbeatability of their door traps.

The cold drove him to activity. Before starting out into the desert, he must get some clothing. He could see but one light in all the buildings of the Center and that was in the guardhouse through which he had entered the institution the day before. He stole toward it, peered through its open door. There was only one monitor on watch, and he seemed to be following the iron rule that one must never be idle, for he was engaged in operating a calculating machine of some kind.

PRESCOTT slid into the room and selected a weapon of handy weight and size from the rack where the day monitors kept their guns when off watch. He did not know the proper use of the gun but it fitted the hand and made an excellent club. After that it was but the work of a moment to steal up behind the night sentry and strike him down.

A few swift turns of electric wire snatched from the machine he had been working on completed the trick. The fellow was neatly bound and gagged. Prescott stood back and admired his handiwork. If he knew anything about wallops on the head, the fellow would be out for the rest of the night. He helped himself to one of the heavy coats and a pair of sandals he found in a locker and then stepped out into the night.

The going was easier than he expected. At night the sand was easy to walk on. A light frost had hardened its surface into a thin crust that most of the time would support the weight of a man.

Prescott struck out boldly across it and took the back-trail to the skyport. He was unused to deserts and had no way of knowing how extensive this one was or what lay beyond its edges. Possibly he might stow away on one of the numerous spaceships he had noticed lying on the landing field the day before.

It was just dawn when he arrived at the edge of it, and he was relieved to see the ships were still there. One monster liner was a trans-galactic cruiser, carrying, he had been told, a relief expedition to Razim. Between him and it rose a huge timbered structure from which rumbling sounds came and clouds of reddish dust. A cranelike arm extended upward from it at a sharp angle and its tip rested on the dome-plate of the ship.

Prescott could see several men walking across the field, and to avoid being seen by them he cut in closer to the building. Perhaps by hiding among its frames, he could study the layout of the ship and plan a way to get aboard. He had taken only one step when something happened to jolt him into swift action. A siren wailed, and in the wake of its warning howl a battery of loudspeakers about the field began to blare.

"Proctors alert! A heretic escaped Center... heretic escaped Center... armed and dangerous... trail points toward skyport... seal and search all ships... report capture to Abbot-in-Charge, Indoctrination Center."

On went that braying chorus, repeating its message interminably. And over its clamor, Prescott could hear the ring of metal on metal as ships' entry ports were slammed shut, and he heard the shouts of men beginning to search the field.

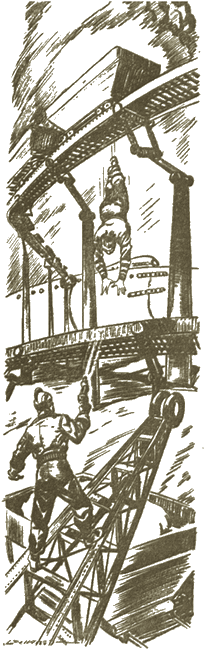

He ran to the side of the structure near him and scrambled up it like a monkey, snatching at small projections and crevices for holds.

He was near the top when he heard yells below and looked down to see a group of monitors. Their leader was a red-faced proctor who was angrily bellowing orders. Prescott hastily resumed his climb and had already thrown an arm over the topmost beam when something hot flashed hissingly by his ear and burst with a sickening ping beyond. He did not expend an instant in seeing what was beyond the beam above him. He simply flung himself over it.

HE was surprised at what happened next. He was falling sheer. He had not recognized the structure for what it was, a fuel depot for interstellar ships. It was a row of huge hopper-bottomed bins fed by a roaring conveyor belt overhead from which tons and tons of floury ground desert sand were being dumped. He happened to have popped into a bin that had just been emptied, and consequently dropped a long way before his heels struck the smooth, inclined walls of the tapered bottom.

Prescott dived and fell into a hopper-bottomed grain bin.

He was helpless to check himself as he shot on downward to the yawning hole at the bottom. He struck it, went through, dropped another few feet, and then brought up in a soft bed of the red flour which at once splashed upward in a cloud of choking dust.

Prescott sneezed violently. Then he was aware that whatever he had dropped onto was moving and that the racket about him was deafening. The dust cloud dissipated partly and he saw next that he was in one of a chain of dust-laden buckets moving along beneath the spouts of the bins. And his glimpse over the side showed him that monitors were already in the tunnel, running up and down and looking for him.

He pulled his head down and snuggled deeper into the dust. Fortunately the dust was ground so finely as to be almost impalpable and therefore behaved much like water. The bucking and jiggling of the bucket quickly erased any surface irregularities. The mounds over where his legs were stuck levelled off immediately.

So he crawled all the way under, leaving only his face exposed. He felt that he was in a fairly safe hiding place, for the dust clung to everything it touched and his face was thoroughly powdered with it and therefore not likely to be noticed.

He was right in that. He had hardly dug in before a monitor stuck his head over the side of the bucket and gave its contents a swift glance. Prescott squeezed his eyes shut and waited. When he opened them again, the inquisitive monitor was gone. But something else was happening.

The bucket had changed its motion. It was rising sharply. In a moment, it was clear of the tunnel and in the open air. Again Prescott was faced with an acute dilemma. He knew now where he was going.

He was being carried slowly and bumpily, but inexorably, up the crane-borne incline to the dome of the big ship he had seen.

When the bucket reached the pinnacle, it would dump him and its contents into the ship's bunker. That probably would mean instant burial and suffocation. On the other hand, even above the din of the conveyor, the yells of the manhunting monitors could be heard. To stand up in the bucket would mean he would be skylighted and immediately blasted out of existence.

He decided to chance the hold. After all, his original plan had been to stow away on board a ship.

Suddenly the bucket tilted. Prescott slid out of it along with the rest of its contents and found himself plunging into dusty darkness in a cataract of fine sand.

HE managed to extricate himself from the torrent that followed, only to find himself in a blind-walled compartment, filled with choking dust, with more of the fuel pouring in every minute. Presently the downpour ceased, and he could see the yellow square that marked the hatchway overhead. Two heads showed in it, peering down into the interior.

"He musta got in here," insisted one, a monitor. "We gotta search it."

"Nothing doing," said the other. "I'm closing the hatch. We shove off right away—Rizam bound. If the guy's here, it's just too bad. This is our reserve bunker, and we may not open it all the way. You can burn that stuff down there, but you can't eat it."

"Gotta search," said the other doggedly. "It's the Abbot's orders, and no third rate Curate of Astragation is going to tell me—"

"Easy, buddy. The skipper of this bucket is a Prebendary. Get that? Where does a lousy Abbot get off telling him what he can and can't do? Outa my way. I'm battening down." The heads disappeared, then the blob of light as the hatch cover was put on and battened down. Then there was utter darkness. A little later the ship shuddered, leaped like a skyrocket. That was bad, for Hal Prescott had still to get used to sudden accelerations. But worse was to come. For he was on an interstellar liner this time and unprepared for the wild burst of acceleration that was to be applied when once the ship was clear of Mars and jumped to almost the speed of light.

A few shots of anti-traumatic serum might have saved him, but he was an unlisted and unwanted passenger. When that terrific surge came, he simply gasped, saw a demented whirling of bright lights against a bloody background, and fell limply against the bulkhead.

He lay there for a long time—a period measurable in weeks and months—in the curious state of suspended animation that any organism is subject to when it is suddenly catapulted forward at colossal speed without prior preparation.

But days later Hal Prescott came to in suffocating heat. He shed his thick coat and stared into the darkness. For a moment, the wild fears engendered by claustrophobia almost got the upper hand, for he was not used to being imprisoned in dark, tight places. But he mastered them and went fumbling about the walls. Then he remembered. There was no outlet from that bunker, unless far below, yards deep beneath the powdered fuel.

Then he remembered the heat gun he had, and tried it. It worked amazingly. In a little while he was grimly at work on a spot in the bulkhead, burning his way through the glowing metal. The cut went through, and he tore out the circular piece of steel and hurled it behind him. Then he crawled through the orifice into a dimly and mysteriously lighted room, dropped lightly to its deck and looked about him.

It was a store-room of sorts, contained nothing but heavy, tough crates, and numbered pieces of machinery. Nothing in it was edible, and Prescott craved food, for in his long slumber he had become emaciated and felt pathetically weak. So he turned his back on the contents of the room and tried its door.

It gave at the touch, and he found himself outside in a slick and shiny corridor. The door closed softly behind him and locked itself with a click, as he discovered when he attempted to push it open again. There was nothing to do, then, but go on. Which he did.

THE corridor was a short one and seemed to give onto another at right angles to it a little way ahead. Prescott proceeded down it with the utmost caution, because behind the next turn there might be a Perfectionist monitor with his accursed tetanizer in hand. So he walked silently, half holding his breath until he reached the intersection. There he paused and listened.

He was instantly glad he did, for strange, whiffling sounds could be heard. It was puzzling, for there seemed to be two separate ones, one superimposed on the other. One was a steady squishing, having an irregular rhythm of its own, quite distinct from the occasional spasmodic snuffling and choking sounds that accompanied it.

His first thought was that it was some small animal in distress, writhing in agony on the slick floorplate. He waited a bit, but the sounds kept up. At length he could stand the uncertainty no longer. He determined to risk a look, and prepared for almost anything, he thrust his head around the comer.

"Almost anything" is the phrase to use, for the quick gasp Prescott stifled told how unprepared he was for what he saw. It was something he had often dreamed of, but never encountered, even in the idyllic mountain valley he called home. Nor was it anything he'd thought he would ever see in the bowels of a Perfectionist galaxy cruiser.

Before him knelt a girl—an incredibly beautiful girl—and she was wielding a dirty wet rag and sobbing bitterly the while! He stared at her, dumbfounded. What was she doing in this lonely, empty corridor? Scrubbing the deck, obviously. But why?

The deck was burnished, rustproof metal and spotless as a polished mirror. No amount of work could make it cleaner. Moreover, no Perfectionist of whatever caste ever performed manual labor or permitted it to be performed when a machine existed that could do it quicker or better. Yet there she was, scrubbing away in the most primitive fashion, and grieving over it, too.

She must have sensed his approach, for when he looked at her she stopped her scrubbing motions. Without looking up or moving she said to him in a low voice full of scorn and resentment,

"I know you are there, but you needn't spy on me. I sinned. I confessed. The penance is being performed as the Bishop ordered. Go 'way. Leave me alone!"

She choked down a sob and went back to her scrubbing. He stood still, not knowing what to do or say.

"Go 'way, I tell you," she snapped angrily, "you give me the heebie-jeebies." She straightened up and sat back on her heels, glaring at him through tear-moistened, smoldering green eyes. The full view of her confirmed the vision he had already conjured up from the sight of her tousled honey-colored hair and the graceful lines of her back and arms.

The hill women he was used to were knotty-muscled tree-climbing creatures, jolly and companionable, but clothed in rough homespun and with skin roughened by the harsh gales of the upland country. Unless he had seen it with his own eyes, he would not have thought it possible for a girl to have the sinuous beauty of a ledge serpent and with it the unleashed vitality of a hill-cat.

"Now I know," he said slowly, "what they mean by Perfection."

THE look of resentment on her face suddenly changed to one of startled wonder. She struggled to her feet, still clinging to her rag, looking at him full in the eyes all the while.

"Oh!" she said, after a long, staring interval, "Now I know who you are. You are the barbarian who escaped from the Center. They said you were dead. But I see you aren't, so I'll have to do something about you."

It was his turn to be startled. A minute or so before he had been tense and ready to grapple with any human being that interfered with him and kill or be killed. But he felt utterly disarmed and helpless.

Moreover, the calm way she was studying him from his dust-powdered hair down to his rust-encrusted bare feet was most disconcerting, and all the more so for the reason that approval and disapproval seemed to be struggling for mastery of the expression of her face. For the first time since he had awakened he was keenly conscious of his unkempt and disreputable appearance. Red grit clung to him everywhere.

"L-like what?" he stammered, completely at a loss.

"Like getting you bathed," she said, cocking her head to one side and with a mischievous twinkle in her eye. "You look like a cast-iron man that has been left out to rust. You are filthy. And what's worse, you're shedding that stuff all over the floor. I'll be blamed for that. They'll say I sulked and committed sabotage. And that'll mean more demerits for me."

He threw back his head and laughed. Her answer was so unexpected that the absurdity of it swept his tension away in one breath. And then be saw that his merriment was not shared by her, that she was regarding him reproachfully.

"All right, all right," he said, more soberly. "But what's this about demerits? What sin is it, anyway, that compels you to do penance by scrubbing floors and weeping?"

"I wasn't weeping," she flared, but she dabbed her eyes with the rag, just the same. "I was only snuffling a little."

"Oh," he said. "But the sin? Was it so terrible, really?"

"Pretty terrible," she admitted sheepishly. "The full charge was frivolous wastage of material and time with subversive intent. That's what the Prebendary called it. But it wasn't that way at all. I cross my heart. I mean—well, there wasn't any subversive intent. I just felt like doing it, that's all. I didn't mean anything by it."

She blushed prettily and dropped her eyes.

"Go on, girl," he urged. "You still haven't told me. What did you do?"

"Fancy work!" She made the admission half apologetically, half defiantly, and looked up at him as if to see how he took it and how deep his disapproval was. "It was this way. One of the atomic blast gang backed into an electronic stream and it burned away part of his dungarees—part of him, too.

"The Dean of Hygiene patched him up, but he couldn't do anything about the breeches. There weren't any spares to fit the man and no machine to reweave the damaged part. Somebody said it could be done by hand, but nobody wanted to do it. Handwork is menial and low, you know. It was a silly thing to do, but I volunteered."

"Go on," he said, smiling at the appealing look in her eyes. She seemed thoroughly embarrassed.

"Well, I stitched 'em. I took a whole day at it. It was the first time I ever handled a needle, so I did my best. I put the patch in first. Then I went over the stitches again and again to make them strong. He was a big man, you know. I thought it would be better if I crisscrossed 'em some, so I put in circles and triangles, all interlaced—spirals, too, in different colors. It was beautiful, I thought, but—"

"You poor dear," he exclaimed, and forgetting all about his dustiness clasped her to him and kissed her tenderly. She had covered her face with her hands and was crying convulsively. Perfectionist be blowed! She was no Perfectionist, but a suppressed artist—one of his own kind, trapped in a hostile environment.

"Th-hey didn't like it," she moaned, clinging to him. "Th-they said it was unnecessary. Th-they said it was a scandalous piece of ex-exhibitionism. They said it was their duty to cure me of such pranks. So I have to do this now—four hours every day until I've fully repented."

HE kissed her again, and when he got his breath he kissed her some more. Suddenly she pulled apart from him and pushed him away with her arms.

"No, no," she said. "I mustn't do this, either. It's a waste of time, too, and that makes it a sin. You see, I'm rated as a class B female."

"Class B!" He almost yelled it, reached for her and tried to pull her back.

But she eluded him.

"I keep forgetting you are a barbarian," she said, dabbing at the dust on her silky plastic smock. "The Class B ones are the non-maters. I'm not the mother type. They say my genetoscope readings are terrible, rebellious chromosomes and all that. That's why I have to be a dietician."

At the word genetoscope his face darkened and he remembered where he was. Genetoscope readings, indeed! If hers were bad, he thought, with grim humor, his would blow the instrument's fuse.

"That bath," she reminded him, looking ruefully at the stains that still clung to her smock. "It's the fourth door on the right behind me. You'd better hurry. The inspector will be along any minute to check up on me."

SHE was waiting when he came out.

"Well!" she said, looking his clean, glistening torso over with unmistakable favor, "you did a good job. But you're thin. I see I have to feed you. Come along."

Prescott followed her obediently. The feeling of apprehension he had had when he first emerged into the ship was gone. For once he was thankful for the rigidity of the routine followed by the Perfectionists since one could predict nicely what they would do and when—if one knew the schedule. He did not, but she did, and he trusted her.

They came to another door and she opened it by a quick manipulation of its dial lock.

"Sustenance storeroom," she explained, briefly. "It's lucky for you I issue the nutriment, or you wouldn't have any."

The thought of nutriment cheered him still more. She had already shown some symptoms of Sybaritism, maybe she had some real food in her lockers.

"I could eat a horse," he said by way of answer. By that time they were inside and the door locked behind them. She was appraising his gaunt ribs professionally.

"You'll eat eighty grams of omnivit," she said, firmly, "and two hundred of proteinax, with a half a liter of solution K-48 to round it out. And like it. No horse. I don't know what a horse is, but, we haven't any."

She counted out the capsules and dropped them into his hand. Then she drew a beaker of rose-colored liquid and handed that to him. She pushed him into a tiny inner storeroom and pointed to a chair.

"You'll be all right here. Eat your ration and be quiet until I come back. Nobody else is likely to come in. I've got to go back and finish my penance now."

He sniffed the foul-smelling pills and the equally obnoxious fluid. They might be loaded with pep and vitality, but they had a bitter taste and to a mountaineer's keen nostrils, simply stank.

He grimaced, but said politely:

"Thank you, angel."

"My name is Nesa," she said stiffly. Then the door clicked behind her.

He eased himself onto a seat and relaxed. For a bit he pondered the queer turn that had taken place in his affairs, but for a few minutes before he had been prowling the empty corridors of the ship hoping to come upon some vital part of it. In his desperation it had been his intention to destroy it and with it as many of the hated Perfectionists as possible.

But that resolve had to be altered now. He could not blindly wreck a ship and a creature like Nesa with it. And who knew? If there was one Perfectionist like her, there might be others. For the first time since his capture, doubt invaded his mind. He might do better to observe before striking.

Of a sudden Prescott's train of thought was interrupted. He heard sounds in the outer room. Nesa had returned! There was someone with her! For an instant his blood ran cold. Had she betrayed him?

HE listened to the voices. The other was a man's—a rasping, unpleasant voice, despite its owner's obvious efforts to conceal it by a syrupy, wheedling intonation. Then came Nesa's voice, low and frightened, but distinct.

"No," she said, "I can't do it."

"But," he pleaded unctuously, "all the obstacles are cleared away. The message came through today. I took it myself—I happened to be testing the long range receiver when it came. The Eugenics Board has rescinded its ban on your marriage. The genetoscope on which you were tested was discovered to be out of adjustment."

"I have been tested five times," she replied coldly, "and on as many machines."

"But the board has overlooked that," he urged, "they have granted you qualification as a mater, and since my name is highest on the application list there is no more to do than go to the Prebendary and be married."

"You are lying, Deacon Kolb," she said with chilling scorn. "I know your uncle is Presbyter of the Eugenics Board and might have done it, but he did not. You received no such message. We are trillions of miles out by now and have received no communications from Earth in days. It is a deliberate forgery."

"Be careful, my pet," he said. His tone was ugly and ominous. "A layman dietician with a record like yours should think twice before using insolence toward a wearer of the blue. I have only to report it to have you sent away to the House of Penitents for years. On the other hand, if you rejoice as you should at my generous offer, I will guarantee to make you a priestess of the first rank. Come!" There was no immediate answer, but Prescott heard instead the sounds of a scuffle. Then there came a stifled scream. It was Nesa's.

"Stop! Take your slimy paws off me!" But the scuffling continued, and a heavy heel struck against the door behind which Prescott was listening. Prescott was raging inwardly, full of fury and itching to fling the door open and intervene, but he held himself. To do that would compromise Nesa hopelessly. If the blackguard now struggling with her were as thorough-going a villain as he sounded, it would give him the very lever he was looking for. But the next words and sounds galvanized Hal Prescott into action.

"You little cat!" snarled the panting deacon. "Take that!"

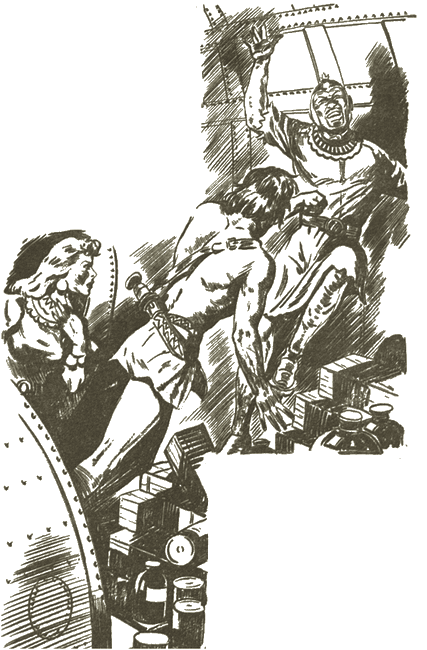

IT was the resounding smack of a heavy slap that catapulted the Venusian heretic through the door. Before him was Nesa in the clutches of a big brute of a man wearing the silver lightning-jagged blue toga of a radio expert, and she was fighting him back tigerishly.

Prescott's left hand grasped the reverend deacon by the scruff of the neck and whirled him around. Then his right drove forward like a battering ram and sent the amorous radioman reeling against the bulkhead on the far side of the room. The man leaned there groggily for a moment, spitting teeth and brushing feebly at his bloody lips with a hand that was obviously unsteady.

A terrific punch sent the Deacon reeling against the bulkhead.

"When I smack 'em, you dirty swamp skunk," said Prescott, standing firmly before the man, "they're my own size and sex. Here's more, if you can take it."

And he doubled up his fist and showed it to him. But the deacon evidently had enough. A deep triple scratch adorned one cheek, the other was swelling rapidly. He only shook his head, but his hand was groping the bulkhead back of him. Then it stopped, and Prescott saw the hand flutter.

"Oh, stop him!" cried Nesa, suddenly realizing what he was doing. She had just got up off the floor where she had been thrown when she was released from Kolb's clutch by Prescott's vigorous yank at him. "He's rung the alarm. The monitors will be here any second."

"It'll be different then," sneered Kolb. "Then we'll see."

"What do you mean, we?" yelled Prescott, diving for him. The deacon cowered and threw an arm up to protect himself, but it was no use. His adversary knocked it aside with one fist and drove the other into his eye. Kolb did not wait for its mate, but sank whimpering to the floor.

"You shouldn't have done that," said Nesa, quietly, though she was rubbing her own inflamed cheek thoughtfully. "It only makes things worse."

"How could they be?" asked Prescott grimly.

There was no answer to that, and no time to deliver it if there had been, for the outer door swung open, and a proctor and a file of monitors stood in it. Blasters and tetanizers were ready in their hands.

"What's going on here?" asked the monitor, sternly, looking at the belligerent, half-naked man before him and the battered deacon struggling to get up from where he had fallen and at the same time trying to rearrange his disordered priestly garments. "Who is this man?"

"He is my friend," said Nesa, proudly. "That is all I know."

"He is a heretic and a criminal," said Kolb, venomously. "He is the escaped probationer from Mars that you searched the ship for. Now you know why you didn't find him. She sheltered him! I demand her arrest, too. I tried to capture him, and would have, but she interfered with me. Take them to the Prebendary at once!"

Prescott laughed out loud. Nesa crept up beside him and slipped one of her hands into his. She lifted his hand so the proctor could see the scuffed knuckles.

"That is what interfered with him, if you really want to know," she said.

"I see it," said the proctor, with a cold glance at the discomfited deacon. It was plain to see that his private opinion did not altogether square with what was expected of him officially. "But let's go."

THE Prebendary was a tall spare man with a flowing white beard and an abundant mane to match. Nesa and Prescott stood in the sinner's box before him, while the accusing deacon and the proctor had their place at the right. Prescott studied the old man's face and concluded that since he had to be tried, it was better to be tried by such a man than by any other.

There was something about the commander's mien that made him think of his old chieftain, Jedson. There were the same compelling eyes, eyes that could be either sternly commanding or genuinely understanding. The face also had that bland innocence of expression that often masks a keen and observant mind.

"Yes," said the Prebendary, "let's start at the beginning. Speak, Proctor."

The proctor told his story. Just what he had seen and no more. Then the deacon stepped forward and told his, though his telling of it was somewhat impeded by having to talk through swollen lips and unaccustomed vacancies in his dental lineup. He had, he said, made an honorable offer of marriage and was astonished at his intended's sudden change of heart.

He had heard sounds inside the inner room and found there the reason for it. He recognized the man instantly as a stowaway and tried to seize him, but she attacked him from behind. During the scuffle that ensued, he inadvertently touched the alarm signal, and the monitors interfered before he could complete the capture. Having testified to that, he withdrew.

"You acted very promptly, indeed," said the Prebendary, dryly.

"I did my best, your reverence," said Kolb, meekly. "May I suggest that your reverence will save time by dispensing with the testimony of the two culprits. Only perjury is to be expected from heretics and abettors of heretics."

"A very shrewd suggestion, deacon," said the Prebendary, with elaborate politeness, and Prescott's heart sank as he saw the beaming smile that accompanied it. "But an old man with a proven record of rectitude may be indulged in small things. It has been a long time since I dealt with a heretic, and I am curious to hear what this one may say. You are excused."

Deacon Kolb muttered something and stepped back. He did not look happy. The Prebendary turned his face toward Prescott in an unspoken invitation to begin.

"Your reverence," Prescott blurted eagerly, for he was as hopeful now as he had been despondent the moment before, "she did not harbor me. She never saw me before until I burst out of that storeroom to save her from attack. She—"

"Just a moment, please," said the Prebendary, mildly. He beckoned a monitor. "Have the Curate in charge of Dietetics take stock of Nesa's stores." He turned to Prescott again. "Go on, but spare me these minor perjuries, if you please. One doesn't get into locked storerooms without either having the combination or wrecking the door."

FOR a moment Prescott was nonplussed, but the order to take stock of Nesa's stores gave him a cue. There would be a few pills missing, but not enough to make the charge of harboring him stick. He did not care much what happened to him, but he wanted to exonerate her and discredit the deacon. So he apologized for his first hasty words and went back to the beginning.

He told of coming aboard, of sleeping, and his escape from the bunker. He told of meeting her in the passage and demanding food. She fed him a few pills and locked him in, saying she would be back shortly. Then he related all that had followed, omitting nothing and adding nothing.

"Hmmm," said the Prebendary, stroking his beard. He beckoned another monitor. "Have both the signal logs brought me—the one in the communications room and my private one, the intercept one. Also the ammeter cards." Then he sank back dreamily in his seat, looked softly at the ceiling a moment, then closed his eyes as if resting. The deacon shifted uneasily on his feet, and the unmarred portion of his face was very pale. Presently both monitors returned, and for a time the Prebendary studied the papers they had brought. Then he called for Kolb.

"Deacon Kolb, I want to thank you for revealing a most deplorable weakness in our organization." The deacon brightened upon hearing that, and for an instant looked almost cocky. "I find it is possible to fake an incoming call by using a distant-control sending set mounted in another part of the ship.

"You knew of course that my master set intercepts all messages, but you did not know that it also recorded the range and bearing of the source. I am somewhat surprised to learn that the Board of Eugenics has a sending station in your sleeping quarters. I am even more surprised to hear that one of my senior priests should press a marriage offer on a young female on the authority of a permission forged by himself.

"I think that this case presents so many unpleasant ramifications that I shall hold it over until we arrive at Razim, where there should be a full court of the Inquisition. In the meantime, you will regard yourself as under arrest and not leave your quarters without my permission. You may now leave the chamber."

But the good deacon could not leave the chamber. He had fallen to the floor in a dead faint. The proctor made a sign and two monitors picked him up and carried him out.

"Nesa may return to her duties."

She bowed, turned, and with the barest flicker of her glance as it swept by Prescott's conveyed a wealth of gratitude. A monitor made way for her, and the door clicked behind her. The Prebendary looked at Prescott, and that time Prescott could see that all the hardness was gone and in its place an infinite weariness, as if what had just passed had been painful to him.

"Do not be afraid, my boy. I have your entire record. It was sent me shortly after leaving Mars by the Abbot there. I do not blame you for your hostility to our order, for you are too ignorant of it, and none of us have gone about your conversion in the proper manner. I have long thought that the methods at the Indoctrination Center were unduly harsh.

"Therefore I am going to give you another chance. The events of today are forgiven, and you are reinstated as a probationary. I shall provide you with what you need and supply a tutor. In the meantime, the proctor will take care of you."

The Prebendary rose and left the room.

A reverent hush prevailed until the door had closed behind him. Then the proctor beckoned to Prescott to follow him the other way.

"Boy, what a break you got!" he exclaimed. He added, with a wide grin, "but you rated it. His ex-reverence Kolb has been overdue for a good walloping for one heckuva long time."

Prescott understood then something that had been puzzling him ever since the entry of the monitors into his little private scrap. On every other occasion when he had been rambunctious, the first thing any monitor did was cut him down with a shot of tetany.

"Thanks," said Prescott. "Thanks for everything."

TO Prescott's amazement, he was made a monitor. The job was not hard, as practically the entire complement of the Evangelist were handpicked people, chosen for their skill and reliability.

That was because the ship was going to Razim, where current conditions were unknown.

His hours were long, and at first the steady routine galled him, but as he became more used to rising and retiring at fixed hours and being at some one else's beck and call, he found it far from intolerable. In his own native habitat, of course, he had waked or slept as he chose like a wild animal, and acted only on the whim of the moment, hunting, fishing, or aimlessly rambling as he chose.

The one detail of Perfectionist life that irked him most was the total absence of what he regarded as proper food, but even that had been made palatable now, for it was Nesa who operated the metabolometer and doled out his daily ration to him. That morning contact was always a brief one, and they seldom spoke, but it gave him the courage to go on.

He found that the duties consisted chiefly of assembling in one of the several guard rooms and waiting for calls. Every compartment of the big ship had at least one alarm button in it, certain others had automatic scanners and dictaphones, so that an organized patrol was unnecessary.

In order to keep the monitor force on their toes, the Head Proctor spent most of his time prowling about the ship and ringing alarms at random, whereupon the nearest squad rushed to report. At other hours the monitors were drilled in marksmanship in the several weapons they carried, also ju-jitsu, wrestling, boxing and other arts of policemanship. These exercises suited Prescott perfectly, and he made a great showing at them.

HIS tutor was not an unpleasant fellow, though much he said Prescott disagreed with. But he was the sort of man who would permit argument and discussion, and that helped. He was a dried-up little man, well into middle age but still only a Curate of Orthodoxy. His low rank was due, in all probability, to the fact that he was not as dogmatic as the bishops thought he should be. His name was Stiver. He and his pupil had many spirited tilts on the pros and cons of their respective faiths.

In the end Prescott was forced to admit there was something to be said for Perfectionism. On Venus, he had eaten what he pleased and as much of it as he pleased, but not always when. There had been occasions when game was scarce, when the berries were eaten by the birds before he found them, or when the wild potato crops failed. Prescott had known gnawing hunger, had even gone through a severe famine that wiped out half his tribe.

On the Evangelist, no one ever truly ate, but no one ever hungered. There was the matter of disease, too. A sick Sybarite either got well or died, just as the pterofelidae did, depending upon his constitution. Every few years, the deadly swamp-pox took its heavy toll, and many of the old were blind. Prescott had yet to see a pockmarked or a blind Perfectionist.

"Yes," he would concede, "you have steady nutrition, sanitation, health. You have better shelter, not the drafty, leaky shacks we live in. You have good illumination, not the smelly tiger-fat lamps with handwoven cottonweed wicks. You have deadly weapons and communications and all that. But what for? You don't live, you just exist. Why not a little fun?"

"It won't work," the Curate would say, wearily, and start his arguments all over. The burden of his discourse was that it had been tried and failed. That had been in America, just before the Totalitarian transition period. Even in that distant age, there had been in existence nearly all the virtues of Perfectionism, though somewhat undeveloped, but there had also been the taint of the pleasure principle.

"They were vicious to the core, those Americans," the Curate said, sadly. "It seems incredible to us now, but history tells us that they used to congregate by the thousands in darkened halls and sit for hours hypnotized by the flickering of shadows on the wall.

"Thousands of acres of arable ground were let go to grass, and multitudes of men wasted their afternoons knocking little balls about so that they would fall into tiny holes. Just why has never been made clear, as they always promptly retrieved the balls. Again, great industries specialized in making small vehicles in which half the population ran about aimlessly over the countryside using fuel that would have powered countless factories for the making of useful things.

"There were many such vices, but perhaps the most pernicious was the time-wasting device known variously as courting—that term is found in the older texts—and necking, which is the later and more decadent version. The silly young creatures of that day did not know that a brief two minutes in a genetoscope would give them the correct answer to a question they often spent years of experimentation on, frequently to get the wrong result."

"Deplorable," Prescott would murmur, maliciously. He remembered some boyish experimentation of the sort with a hill girl from over the southwest spur. It was vastly preferable, in his opinion, to the somewhat unpleasant probing done on him by the genetoscope they used.

And so it went. Stiver registered some points, but Prescott was far from being converted. He kept thinking of Nesa and the ban on both of them.

"Pfui on the Eugenics Board, the stuffed shirts!" was his thought on that score. An ounce of instinct is worth a pound of science. That was Prescott's view, and he refused to change it.

At other times, the Head Proctor would talk to him.

"We don't know what to expect at Razim," he said, one day. "Earth lost contact with it about two hundred years ago. Something happened, but we don't know what. It may only be that the ships couldn't come back—the older ones had to have uranium and there wasn't much of it on Razim "This is the first one big enough for a trans-galactic flight that has been built since atomic power came in. It burns iron, and you can pick that up almost anywhere. That stuff you came aboard with is just reserve."

"Uh huh," said Prescott. They were ten months out now and they hadn't broached it yet. He was glad he got out of the bunker.

"We sent a good many ships out there in the old days, but it took ten years or so then to make the trip one way. So not many came back, ever. The last we heard they had built some fine cities and had a first-class civilization going.

"The planet is a lot like Earth, except it has no moon and it sits straight up and down on its axis. That makes the seas tideless, and the weather very regular. The place is ruled by a cardinal and it ought to be pretty well run. The capital is where we're heading." The proctor stopped and looked at Prescott questioningly, as if making a final size-up of him. Then, with a show of hesitation, he went on.

"There's something I think you ought to know, but I don't know whether I ought to tell you. But I'll take a chance—you've gotten to be pretty regular. The Prebendary is worried. He thinks maybe there'll be trouble. That's one reason he let you go. You're a big husky and a good rough and tumble fighter. You may come in handy. Then again, he might want an ambassador."

"Ambassador? I don't get it."

The proctor looked about him, then bent forward and almost whispered.

"The last ship back said there had been a Sybarite revolt."

"I see," said Prescott, thoughtfully. He was more glad than ever he had taken that risky dive over the trigger rays of his cell at the Martian Center. On this planet he might find buddies.

The star Mizar brightened to the minus ten magnitude, then to twenty.

Then it became a definite disk. A new star popped up beside it. That was the planet Razim. The Evangelist slowed to a quarter of the speed of light and prepared to cut still more.

All hands were called to assembly in the chapel, where a huge visiscreen showed all that was before and under them. It was during Prescott's rest period, so he was free to sit where he pleased. It pleased him to crowd into the dietetic section and jam himself down beside one of its lay workers.

"Hi, angel," was his greeting.

"The name is Nesa," she said stiffly. "How often must I tell you?"

"Oh, I dunno—as often as I see you, I guess. Hope that'll be a million times or more."

"Oh, look!" she said. A huge blue disk was cutting onto the field of the screen. That meant the ship had altered course and was diving straight at the planet of their destination. The bluish tint grew paler, turned to silver with green patches and white, showing where the continents lay and the polar ice caps. In a little it grew so large that only areas of the surface were visible, and those slid by rapidly. The Evangelist was circumnavigating the globe now, losing altitude all the while.

PRESCOTT'S keen nostrils dilated. He sniffed the air again to make sure. Ah, there it was more distinct than ever—air, genuine air, with the reek of pine scent in it. They must be very low, and the Prebendary had ordered outside air to be sucked in and distributed through the ducts. It was a welcome change from the sterile, odorless stuff of the long voyage.

Prescott looked more closely at the screen and saw they could not be much over a couple of miles up. A deep blue ocean now rolled beneath, colored here and there by greenish or yellowish patches where an occasional submerged island almost broke the surface.

"Beauty does get you, doesn't it," whispered Nesa, gripping his arm.

He could not answer at once. Something was in his throat. The sight of the free rolling sea with white touches of foam where the bigger waves tumbled their crests, and the clouds floating above were too much for him. He had not seen water, cloud, a growing thing or beast since the day they dragged him drugged from his rude cottage among the Venusian crags.

There had only been steel walls—slick, flat, uniform, imprisoning. At the sight of that wind-ruffled sea, all the barbarian in him rose to the top, and he had nothing but contempt for the miserable automatons who sat docilely in serried rows all about him. For all but one, that is—he bent his head near her ear.

"That is just the beginning," he whispered. "When we get there, we'll run away, and I'll teach you things—what roast boar tastes like, how to cut a flute out of a reed, how to sing, dance and play and many other things. You will be my probationer then—no more pills and stinking solutions."

"Savage!" was her retort. But she squeezed his arm and nestled closer.