RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"The Quests of Paul Beck,"

with "Drowned Diamonds"

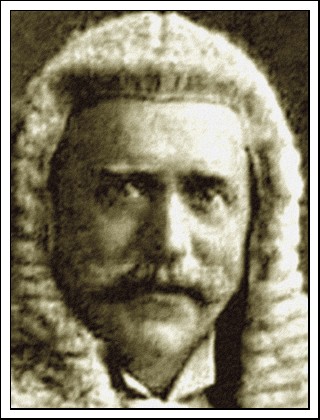

M. McDonnell Bodkin

Irish barrister and author of detective and mystery stories Bodkin was appointed a judge in County Clare and also served as a Nationalist member of Parliament. His native country and years in the courtroom are recalled in the autobiographical Recollections of an Irish Judge (1914).

Bodkin's witty stories, collected in Dora Myrl, the Lady Detective (1900) and Paul Beck, the Rule of Thumb Detective (1898), have been unjustly neglected.

Beck, his first detective (when he first appeared in print in Pearson's Magazine in 1897, he was named "Alfred Juggins"), claims to be not very bright, saying, "I just go by the rule of thumb, and muddle and puzzle out my cases as best I can."

...In The Capture of Paul Beck (1909) he and Dora begin on opposite sides in a case, but in the end they are married. They have a son who solves a crime at his university in Young Beck, a Chip Off the Old Block (1911).

Other Bodkin books are The Quests of Paul Beck (1908), Pigeon Blood Rubies (1915), and Guilty or Not Guilty? (1929).

— Encyclopedia of Mystery and Detection, Steinbrunner & Penzler, 1976.

MR PAUL BECK went to Eagleton on business. He stayed for pleasure.

He was sent down to secure evidence against a young bank clerk suspected of serious defalcations. The result of his investigations was to send to penal servitude a highly-respectable bank manager who had ingeniously endeavoured to shift his own guilt on to the shoulders of a subordinate.

The amount at stake was very large and the fee substantial. The job had only taken four days, and Mr Beck, who had nothing pressing on his hands, stayed on at the Rockwell Hotel, Eagleton. The place has so recently and so suddenly grown into public favour that it is hardly necessary to mention that Eagleton has been always one of the most beautiful, as it is now one of the most popular, watering-places in the three kingdoms. The town stands on a gentle slope, backed by a circle of high hills and fronted by a beautiful bay.

Doubtless the building of Rockwell Hotel largely helped to make Eagleton fashionable. At one corner of the bay a broad flat tableland, level as a billiard-table, runs out into the water. A foot under the soil is solid rock which meets the sea in a sheer wall fifty feet high. Of this wall twenty feet are over the water, and thirty feet under it.

Right at the edge the great hotel is built. The terrace at the back of the hotel looks not merely over the sea, but down into it. The boats are moored under the hotel windows, and spring-boards for bathers strike out from the railings of the terrace. It reminds one of Venice, with this difference, that instead of a dark, muddy canal there is a wide expanse of clear, blue water hedged in by the everlasting hills. No wonder the Rockwell Hotel made Eagleton popular.

Yet it was not the beauties of Nature—at least the inanimate beauties—that kept Mr Beck in the place after his work was over.

No doubt it suited him. There was a fine golf links at the further end of the town where the land begins to slope up from the sea. The sea-fishing was excellent, and Mr Beck, as we know, loved fishing of all kinds. A tiny motor launch—light and swift as a bird—whisked him over the bay to the spot, near or far, where fish were plentiful and hungry. These were potent inducements, no doubt, but there was still "metal more attractive."

The main inducement that held him in Eagleton was the charming companionship of Miss Alice Rosedale, the American heiress, who was staying with her father, Joshua Rosedale, at the Rockwell Hotel. Mr Beck liked girls—especially when they were so young and pretty as Miss Alice Rosedale. This stout, middle-aged detective was as devoted to the service of the sex as a knight-errant of old, and as ready when the chance offered to do them a service.

Let it be said the feeling was reciprocal. All the girls were fond of Mr Beck and treated him with an affectionate freedom and familiarity that made the young men grind their teeth with envy.

Miss Alice Rosedale publicly declared she was in love with him, and she was ready at any time to throw over any of her young admirers for a round of golf with Mr Beck, or a run over the bay in his motor-boat.

Yet, strange to say, her two chief admirers, though hating each other cordially, were both the very best friends with Mr Beck; moreover, her father had taken a special fancy to the good-humoured, good-natured detective.

"May I come?" he said one morning as Mr Beck went down the iron ladder from the hotel terrace to his motor-boat. "There is something particular I want to say to you."

"Of course," said Mr Beck, as he slipped the rope from the ring.

Mr Rosedale sat in the stern, smoking a huge cigar, while the boat slid out over the still blue waters of the bay—swift, smooth and noiseless as a skater on ice.

Plainly Mr Rosedale had a difficulty about that something particular he wanted to say to Mr Beck.

He began awkwardly enough at last. "It is only this morning," he said, "I heard you were the detective who got the young fellow out of his trouble and brought the real criminal to book. All the town was talking about the business, but no one knew you had a hand in it. I saw the new bank manager yesterday. I had a pretty big lodgment to make, and he told me the whole story in confidence. 'Gad! it was the smartest thing I ever heard."

There was no false modesty about Mr Beck. He beamed at the other's praise.

"Luck helped me as usual," he said, "but you'll keep the story to yourself—won't you? I'm having a real good time down here, which might be spoilt if people knew who I was."

"Oh, that's all right! I'm close as a clam. But I thought, perhaps, you might do me a trick of your trade while you are here. Now keep your hair on, at any rate till you've heard what I've got to say. I'm a rough sort of chap, and I've made my own pile. I've been in everything but gold mines, and I haven't missed that much, for pretty near everything I touched turned to gold. Live meat, dead meat, wheat and oil—I've had a go at everything that had a dollar in it, and I've nearly always been lucky enough to get in on the ground floor and come out at the top."

"There's nothing like luck," Mr Beck agreed sententiously.

"Well, my biggest bit of luck is Alice."

"That's so," assented Mr Beck, with emphasis.

"Alice gets what she wants," said her father.

"So I should imagine."

"Have you seen her necklace? No! Well, I'll get her to wear it to-night. I tell you it's fine. The middle diamond I picked up from a Kaffir at the Cape. I didn't ask where he found it. I've made many a good bargain in my day, but that was about the best. There's close on half a million dollars squeezed tight in that bit of glass. The other stones aren't bad—the smallest cost more than the big one. You can't match that necklace in America, and you can't match the girl in the world. Now I want you to keep an eye on both for me. See!"

Mr Beck was jointing his rod, and they were near the centre of the bay—sea, lake or river, he always fished with a rod.

"From what I have seen of Miss Alice," he said, "she is pretty well able to take care of her necklace and of herself."

"She's spry—that's so, she's spry, but girls and jewels tempt thieves. There have been three tries for the necklace, and it was nearly gone once. You know Jim Morgan?"

"He's no thief," interposed Mr Beck, bluntly. "He's a man if I know a man."

"In a way you're right—in a way you're wrong. He doesn't want the diamonds, but he's got a hankering after my girl. He'd steal her if he got half a chance."

"I don't blame him."

"Nor I, but I'll stop him. Jim is right enough. His father and I were partners once. Jim has made his pile on a cattle ranch. He can shoot and ride some, and he is very welcome to any girl in America except mine."

"And why not yours?"

Mr Beck had hooked a heavy fish and was playing him on his light rod while he listened and answered. The struggling, splashing fish and the imperturbable angler were curiously suggestive of the man's method.

"Why not yours?" he repeated, winding up his line, for Mr Rosedale had come to a halt.

"Well, it's this way," he blundered out at last shamefacedly. "Jim is a good chap. I'm not denying it—and he and Alice ran together when they were children. But I promised my old woman when she was leaving that I'd marry the girl to a lord, and I don't want to go back on my word. She's good enough for any lord."

"Too good."

"Well, a lord it is to be. I'd sooner have a French lord than a Britisher. Britishers are getting too common. What do you think of the Count Victor D'Armaund? He's spry!"

"Very spry," Mr Beck assented drily, as he brought the meek, exhausted fish to the boat's edge, and with a dexterous dip of the gaff nicked him on board.

"He's got five chateaux and a forest in France," said the millionaire; "he told me so, and his title comes down from the Crusaders. Of course I took his word for it, but business is business, and I've sent a man special to France to make sure. Alice seems to cotton to him; if the title, etc., are O.K., he might do."

"Yes," assented Mr Beck, drily as before, "he might—do." The last word came out by itself as he unhooked his fish, and with a quick jerk of his wrist swished the shiny bait back into the sea.

"But where do I come in?" he asked mildly, when Mr Rosedale again came to a halt.

"Well, I thought you might just keep a look round promiscuous-like, in case anything should happen. As to fee, just name it. I'll write the cheque when we go back; you put the figure in yourself."

Mr Beck took him up short. "Let us leave the cheque-book out of the question," he said. "I'm here for amusement, not money. I'm a rich man too, Mr Rosedale, I may say a very rich man. I have been lucky enough to be of service to people who have lots of money, people like yourself who were rich and over-generous, and they have given me a fair share of the spoil. I have made my own hits on the Stock Exchange as well. I've more money than I shall ever know what to do with."

"Then why——?" Mr Rosedale began.

"Why am I a detective you want to know? Because I like the work. Why does a dog set game? Instinct, I suppose. But it isn't altogether instinct with me. I have managed to help at least as many as I have hurt, and as I help the good and hurt the bad I feel I am a kind of Providence in a small way of business. Miss Alice and I are very good friends, and I should be glad, if you like, to keep an eye on her and her diamonds."

"Shake!" said Mr Rosedale. "I'll take you at your word. It's a load off my mind to know you are hanging round."

That evening there was a dance at the hotel, and Mr Beck, with his back to the wall, looked on benevolently while Miss Alice danced with the French count. A handsome man was the Count—tall and graceful, and swarthy, even for a Frenchman, with an abundant crop of shiny black hair, curly and silky as a water spaniel's. Strangely enough his eyes were steel blue, and gave a special character to his otherwise somewhat commonplace good looks. Most men looked twice at Count Victor D'Armaund, and most women oftener, to the danger of their peace of mind.

He "waltzed divinely," and the eyes of Miss Alice, as they swung and whirled to the languorous strain of the music, beamed with the girl's delight in a jolly dance and a perfect partner. Her dress was of fluffy silk, with a pretty rosebud pattern, and round her slim, white throat were the diamonds. It was a collar of gems rather than a necklace, with the famous Rosedale diamond blazing in the centre under the pert dimple of her chin.

She caught sight of Mr Beck by the wall, and flung him a saucy smile as she swept past. But there was no smile for the young fellow who stood beside Mr Beck—Yankee writ plain in his tall, lank, strong figure and keen face with deep-set eyes that glowered at the Count.

"Pop told me you wanted to see the diamonds," Alice said as she walked past after the dance, leaning lightly on her partner's arm. "Catch!"

She undid the collar of diamonds from her neck and tossed it—a flash of white light under the electric lamps—to Mr Beck.

He caught it lightly in a big, brown hand, and followed her to the door of the ballroom.

"I will sit out the next dance after supper with you," said Miss Alice, generously. "Pop tells me you are a judge of diamonds. I want to know what you think of mine."

Mr Beck got to a quiet corner under a lamp and peered closely at the jewels that lay—a little pool of limpid light—in his hollow palm, while his practised eyes appraised their value. The huge Rosedale diamond seemed to hold a fire imprisoned in its heart which broke forth in streams of coloured sparks through every facet.

"I wonder what your history will be," he said gravely, "when you are a hundred years over ground. Will you have the same grim story as the other big diamonds to tell of trickery, cheating, robbery and murder? Mr Rosedale is right; these gems will take some looking after. Well, I'll do my best while I'm here—I can do no more."

Miss Alice found him in his quiet corner, his eyes still on the gems.

"Ours, I think," she said, with a demure little curtsey, and with her hand on his arm stepped daintily across the room to the passage that led to the terrace by the sea.

"We will be quite comfy here," she said, as she nestled down amid a pile of silk cushions in a big wicker chair. "I sent Jim for the cushions," she added wickedly; "he doesn't mind you. But when I told him at first I was going to sit out with the Count he gave me a look like a bowie-knife."

"Why do you worry him?" asked Mr Beck.

"What do you think of my big diamond?" replied Miss Alice.

"It's one of the finest I have ever seen. I believe it is one of the twelve best in the world."

She clapped her hands in childish glee.

"I'm so glad! I couldn't quite trust Pop; he so cracks up all that belongs to himself, daughter included. You're sure?"

"Quite."

"Well, you shall put it on for telling me. There!" With big, strong fingers, that were wonderfully light in their touch, Mr Beck fastened the glittering collar round the fair neck, and the thought came to him that Mr Rosedale was right again—the daughter, too, would take some watching.

She was bewitchingly lovely in the moonlight, with that magic circle of coloured light at her white throat. Dainty and fragile she looked as a figure of Dresden china, but he knew what a wonderful reserve of strength was in that slight, girlish figure, where every muscle was of fine steel. He knew, too, that the dainty little lady had a mind and a will of her own.

"Now what about these two men?" said Mr Beck, coming, with quiet persistence, back to the topic she had evaded.

"I do my best," she said, with an unctuous upturning of the bright brown eyes, brimful and running over with mischievous light. "I divide my time fairly between the two. I row and swim with Jim, and I play tennis and dance with the Count. The Count doesn't swim or row, and Jim doesn't play tennis or dance, so it's a sort of fair divide. I'm sure neither of them grudges you your golf."

"My good little girl," said Mr Beck, "you don't want me to tell you that you can only make one man in the world happy, though you can make as many as you choose miserable? You cannot marry both Jim and the Count—not in this country, anyway."

She bubbled over with delicious laughter.

"Oh, you dear old Mrs Grundy! I see dad has been talking to you of the daughter as well as of the diamonds. He wants me to throw Jim over and marry the Count. Now doesn't he?"

Mr Beck nodded.

"Can you keep a secret?"

He nodded again.

"Well, I can't marry the Count because he's married already, and two wives are no more allowed than two husbands in this country. The Count told me himself the very first day. Perhaps he was afraid I'd fall in love with him and break my innocent little heart. Anyway he told me, and I begged him not to tell anyone else. That's where the fun comes in, you see. Pop is delighted and Jim is distracted, and I have my amusement for nothing."

"And when you are tired of your sport?" ventured Mr Beck.

"When I am I'll tell you, but that's not yet. Now take me back. I have promised the next waltz to the Count, and I just love to see Jim glowering."

She told the Count what Mr Beck had said about the diamonds, and the Count was much impressed. It seems that he also had some knowledge of precious stones.

"But you can never judge fairly by artificial light," he said; "it needs clear daylight to make sure."

"I will bring them down with me to breakfast to-morrow," interposed Alice—"I will be breakfasting at eleven. And you?"

"The same hour," gravely responded the Count.

"What a curious coincidence," said the girl innocently. "Then we shall meet at breakfast most likely."

Later in the night the girl and the Count had paused by the open window, after a long waltz which they had danced through from the first note to the last. The room was hot and the crowd great. Alice Rosedale was cool, fresh and dainty as a newly-plucked flower. Nothing tired her—nothing heated her. But the Count breathed quickly, and was flushed with exercise, and his gloves clung to his fingers as he took them off slowly.

"Tired out, Count?" said the smiling Mr Beck, pausing on his way to the door.

The Frenchman put the suggestion aside with a scornful little shrug.

"One is never tired in heaven," he said with his quaint French accent.

"I suppose I'm getting too old for heaven," Mr Beck rejoined placidly. "Good-night, Miss Rosedale; good-night, Count."

Contrary to custom, he shook the Count heartily by the hand as they parted.

When he got to his own room Mr Beck noticed several faint, greyish stains on the pure, smooth white of his right-hand glove. He examined them with a magnifying-glass, and then put the glove carefully aside.

The Count and Miss Rosedale met as she had prophesied at breakfast in the open air on the terrace looking over the tranquil sea just touched into sparkling ripples by the morning breeze.

A dainty breakfast tempted appetites that needed no tempting, and the beautiful surroundings heightened their enjoyment of the meal.

"May I have the felicity?" the Count asked, when they moved to a broad bench closer to the sea. He held his gold cigarette-case open.

It was characteristic of the man and his gallantry that the cigarettes had a faint odour of violets. They were specially designed for ladies' smoking.

The girl nestled more cosily amongst her cushions and looked out over the glorious view. The broad floor of blue water was circled by a range of hills whose peaks and curves stood in sharp outline against the sky. A fresh breeze was on the wing, and little waves, white-edged with foam, raced shorewards.

A white-sailed yacht a hundred yards from where they sat gave brightness and life to the picture. The crew were busy aboard, apparently hoisting sail and weighing anchor for a cruise.

To the right Mr Beck in his motor-boat was moving slowly with a fishing-rod arched over the bow and a line trailing through the sparkling water.

A softer light dawned in the girl's eyes as she looked out over the sea, wholly oblivious of the handsome Frenchman at her side.

"You have forgotten the diamonds," he said tentatively; "is it not so? Young ladies forget—yes."

She woke up suddenly at the sound of his smooth voice.

"Wrong," she said sharply; "women never forget when they want to remember. I have brought you the diamonds."

She drew the case from a flimsy little bag of brocaded silk where she kept her handkerchief and purse, and handed it to him carelessly.

He took it as carelessly, but she noticed at the time that his hand trembled as he took it and his face paled. Perhaps he had some presentiment of what was to follow.

When he opened the case a cry of delight escaped him. The diamonds were one blaze of dazzling, many-coloured light in the sunshine. The Count examined them carefully. "They are priceless!" he murmured. "Priceless! Matchless! May I be permitted? In your dark hair they would superbly show."

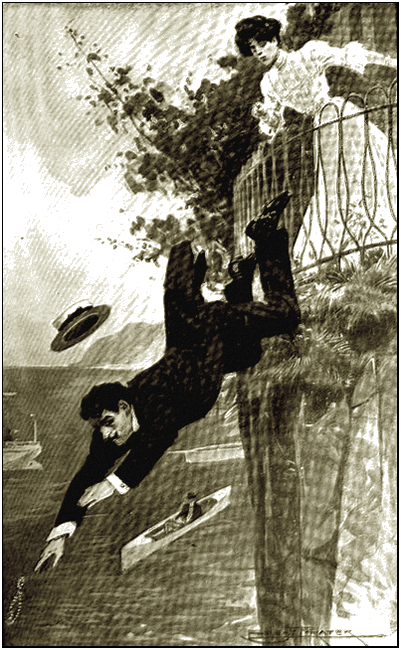

But as he took a hasty step forward to where she sat his foot caught in the edge of the rug and a stumble shot him against the railing that, waist high, guarded the terrace. His feet went up and his head down as he struck, and he was flung in an awkward heap over the railing into the sea. The diamonds left his hand as he fell and shot in front—a curved streak of light.

The diamonds left his hand as he fell and

shot in front—a curved streak of light.

A frightened scream broke from the girl's lips. She was on her feet in a moment, at the edge of the terrace, with eager eyes on the tossing water. Like a flash she remembered that the Count could not swim, and she stood ready to plunge to his rescue the moment he showed above the surface.

But he never showed. He went down like a stone, and the water closed on him unbroken.

While the girl stood poised like a statue of a diver at the terrace edge, Mr Beck, who had heard the scream and seen the splash, turned his motor-boat sharply towards the terrace, and as it shot by plunged for the spot where the Count had disappeared. The frightened girl thought he, too, was lost, so long he remained beneath the water, but at last his head broke the surface at least twenty yards further out to sea than where he went in. He came up empty-handed, and turned and swam straight for the motor-boat which had drifted in close to the terrace.

Meanwhile the crew of the yacht who had a full view of the accident dropped the sails they were hauling and rushed to the side excitedly. Two of them clambered into the punt that dangled at the stern, and rowed slowly backwards and forwards over the hundred yards' space of water that lay between the terrace and the yacht, with eyes close to the surface searching the depths.

It was all in vain. All in vain, too, a little later, a swarm of volunteers composed of expert swimmers and divers from the hotel, explored the water in all directions. There was no current in the place. The water, though deep, was very clear and free from wind, and the bottom of smooth, firm sand. The disappearance of the unfortunate Frenchman and the diamonds was a bewildering mystery.

Mr Rosedale rampaged over the place, now offering fabulous rewards for the recovery of the man or the diamonds; now shouting directions to Jim Morgan, who headed the splashing search party in the bay, and who was as much under the water as over it.

All this time the girl sat apart, silent and very pale. She showed no interest in the search. The man was drowned—nothing else mattered in the least. The horror of it stunned her. The passage from life to death had been so sudden—one moment smiling beside her, gay, handsome, full of life and spirit; the next dead.

What did it matter whether they found the corpse or the diamonds? The man himself whom she had laughed with and played with was gone out of the world. Sitting there in the sunshine, with the beautiful world around her, her warm heart was chilled with the horror of death. It had come so close that she could never again hope to escape from the grim shadow of that remembrance.

Her listless eyes chanced to light on the figure of Mr Beck, and in some vague way she was cheered at the sight of him. That sedate, comfortable, commonplace figure made horror seem unreal. After his first impetuous plunge into the water Mr Beck seemed to take no further part or interest in the performance. He had changed his clothes, had taken a solid, solitary lunch, and now sat comfortably in the stern of the motor-boat watching the animated scene in the water.

The quest was at last abandoned in despair. The white-sailed yacht meanwhile had gathered up its crew and put out to sea. Jim Morgan, his search over, was lounging disconsolately on the terrace when Mr Beck beckoned to him from the motor-boat.

"Well?" said Mr Beck.

"It isn't well—it's confoundedly unwell."

"Keep cool, young man."

"You might as well tell the devil to keep cool on his gridiron. I shouldn't mind the old chap cursing and growling, but the girl's face takes the life out of me. When I spoke to her just now she didn't answer, but she stared at me as if I had murdered that Frenchman. I never cared for him overmuch, I admit, but I was sorry he went under. I'd have saved him if I could. Where did he go to, anyway? He's not in the water I'll swear."

"Nor on the land," added Mr Beck.

"Of course not; I saw him go down."

"And didn't see him come up. So he's drowned of course, isn't he?"

There was a curious tone in his voice as he put the question that made the young American look up suddenly. Mr Beck caught his eye and winked.

"What the mischief are you driving at now?"

"Will you come for a short trip with me in the motor-boat?"

"Why?"

"I'll tell you and show you."

"Let her rip then; I'm just aching to know what's up."

Mr Beck turned the electric switch and started the engine. The bay was empty of pleasure boats, only far out in the offing gleamed the white sails of a yacht heading straight for the open sea.

"Now," said Jim Morgan, "you've got to tell me where are the man and the diamonds, if they are not at the bottom of the sea."

"There!" said Mr Beck, laconically, and he pointed a thick forefinger at the white-sailed vessel that seemed to come slowly back to them across the broad blue expanse of the bay.

"But how in creation," stammered the American, "did he get there?"

"Dived from the terrace to the boat."

"Not to be done," retorted the other, sharply; "the Count cannot swim a stroke. The boat was a good hundred yards off when he went down. The man doesn't live that could dive the distance."

"That depends on circumstances," answered Mr Beck, placidly as ever; "a tow-line was one of the circumstances. I might have guessed if I didn't see, but as it happened I did see. My blundering good luck helped me as usual.

"When I jumped overboard to rescue the Count it was all plain as a pikestaff. The trick was neatly arranged. A weight was laid with a line attached close to the terrace. Of course the Count could swim like a fish. He first picked up the diamonds, caught the weight, and was hauled hand over hand like a hooked fish under the yacht and up the other side.

"When I was in the water I saw him shoot past me without moving hand or foot as fast as a darting trout. It was easy to guess the rest, so I just came out and lunched and waited."

"But why wait? Why let us make a parcel of fools of ourselves hunting in the water? Why not nab him at once?"

"I was taking no risks, young man. He might have passed the diamonds to a pal. As it is, I'm quite sure he and the diamonds are safe on board the yacht, though we may have a little trouble in laying hold of them."

Jim Morgan's eyes brightened, and his lips tightened at the word "trouble."

Mr Beck nodded approvingly.

"So I thought," he said, as if answering some remark of the other. "Can you shoot?"

"Some," said the American, modestly.

He had been reckoned the best rifle and revolver shot in Texas.

Without a word more Mr Beck passed over a serviceable revolver.

"There are three of them, I think, on board," he said, "including the Count. But they won't show fight—not real fight. I want you to do a bit of fancy shooting to scare without hurting them."

"I'm there," Jim Morgan answered, examining the revolver approvingly; "it's a nice gun."

The space of sea between the motor-boat and the yacht closed rapidly. Mr Beck and his companion could distinguish the figure of a man at the wheel, and another leaning over the rail. More and more distinct the figures grew.

The man at the wheel was dressed in blue serge, with a stiff straw hat; the man at the rail wore white ducks, a blue coat with gilt buttons, and a gold-braided yachting cap. He held a binocular to his eyes pointed at the motor-boat.

With his hands hollowed to his lips Mr Beck sent a loud-voiced hail over the narrowing strip of sea. But the yacht held steadily on to her course. The motor-boat racing at twenty miles an hour, her keen prow cutting the water like a knife, doubled the yacht's speed. They were close under the stern when again Mr Beck yelled out a peremptory "Stop!"

For answer the man at the helm raised his right hand; there was a puff of white smoke and a sharp report, but the bullet flew wide.

"I thought so," said Mr Beck; "poor shooting! Your turn now, Morgan."

Jim Morgan raised his "gun" swiftly, his arm bent double, his elbow to his side. Without a pause for aim as the muzzle went up he fired. The straw hat, with a bullet-hole through the crown, skidded into the air, swooped on the wind like a soaring bird, and dropped far out to sea.

The steersman let go the wheel, and the yacht swung round with the wind. The man at the rails rushed to the side. Jim Morgan fired again, and his glasses jumped from his hand and crashed on the deck.

"What the blazes do you want?" he yelled.

"To come aboard," retorted Mr Beck; "lay to!"

"You'll pay dear for this outrage."

"Someone will pay dear, no doubt," Mr Beck retorted. "Let down the ladder."

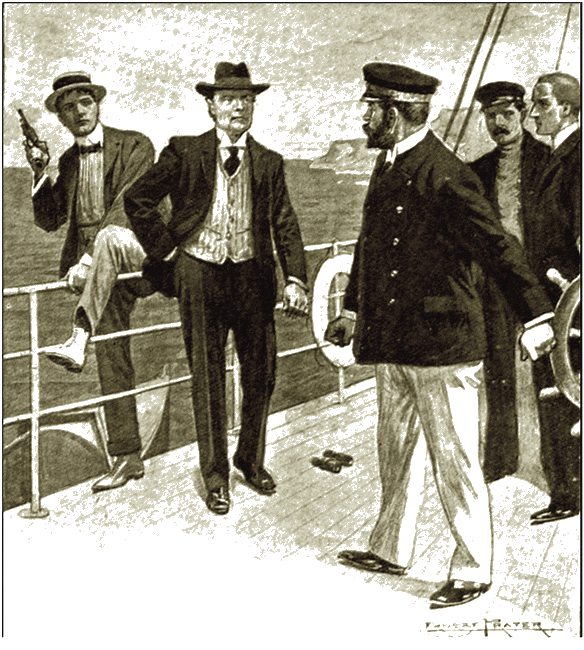

The motor-boat, with engines reversed, glided smoothly under the yacht's side, and Mr Beck climbed aboard. Jim Morgan, with revolver ready, followed. There were three men on deck. The stout man in the gold-laced cap, plainly owner and skipper; the hatless helmsman—a good-looking, fair-faced young fellow with close-cropped, straw-coloured hair; the third a foreign, sallow-complexioned, common sailor with shifty eyes.

The stout skipper foamed and spluttered with rage.

"May I ask again," he growled, "what is the meaning of this outrage? Why have you forced yourself on board my boat? I demand an instant explanation."

The stout skipper foamed and spluttered with rage.

"May I ask," he growled, "what is the meaning of this outrage?

"Why, certainly," replied Mr Beck, with invincible good humour. "I've come to arrest Count D'Armaund and his accomplices for the robbery of the Rosedale diamonds."

The stout man laughed scornfully.

"Find your Count," he said, "you are welcome to search for him."

"Don't need to," retorted Mr Beck; "I've found him."

He laid his big hand heavily on the shoulder of the bare-headed helmsman.

Again the stout man laughed derisively, and the bewildered Jim Morgan cried out:

"That's not the Count!"

But Mr Beck's strong hand gripped the man's shoulder firmly.

"It's all right, sonny," he assured the young American. "The Count's clothes, and the Count's wig, moustache and complexion have gone into the sea, but the Count himself is here. Allow me," and he snapped a pair of handcuffs on the man's wrists. "You're safe for seven years," he said pleasantly. "I've got your thumb and finger-marks on a white kid glove in a drawer in my bedroom at the hotel. See! Your turn next, my friend."

The stout captain's hand dipped towards his coat pocket, and on a sudden Mr Beck's smiling eyes blazed with anger. Quick as light a pistol was at the stout man's head.

"Hands up!" he cried sternly, "or I shoot you like a dog!"

He picked a revolver from the right-hand pocket of the pilot coat and tossed it overboard. "Ah! that's better!" and again there was the snap of the handcuffs. The third sailor submitted without protest, and the three huddled together disconsolately like fowl when a hawk is overhead.

"Now to find the diamonds," said Mr Beck, and as he spoke he caught out of the corner of his eye a glance of triumph between the Count and the captain, and guessed that his task would not be an easy one.

Nor was it. For an hour and a half, aided by Jim Morgan, he searched the yacht from stem to stern without result.

A sudden thought seemed to strike Mr Beck, and he picked up the binocular that lay on the deck, and examined it carefully. The bullet had cut the leather casing and slightly dinted the metal; otherwise the glasses were uninjured. Mr Beck adjusted the focus and looked back over the bay.

"Ah!" he said at last briskly, and closed the glasses with a snap. "What a confounded fool I am to be sure!"

"Well?" queried Jim Morgan.

"We're going back," said Mr Beck. Then with Jim's help he furled the sails, shipped his three handcuffed prisoners into the motor-boat, and, with the yacht in tow, trailed slowly back towards the hotel.

"See that chunk of cork ahead?" he said to his companion. "I want you to pick it up as we go by. I've a fancy it may come in useful."

"What for?" queried his companion.

"Luck!" replied Mr Beck. "I've a notion it means luck."

Leaning over the side Jim Morgan splashed his hand in the water, and caught at the cork as Mr Beck steered dexterously close.

He gave a cry of surprise as he pulled it aboard. To the underside of the derelict cork was fastened a fine silk fishing line, from which a weight hung far down in the water.

"Haul in!" directed Mr Beck, and hand over hand Jim brought his catch into the boat. It proved to be a small, yellow oilskin bag tied tight at the neck.

"Oh!" cried the Yankee, with sudden understanding.

"Yes," assented Mr Beck. "Neat, wasn't it?"

And cutting the string he poured the rescued diamonds like a stream of light from the dripping mouth of the bag. "The 'Count,'" he said, "is the smartest diamond thief in Europe."

Four people dined luxuriously together that night at the Eagleton Hotel. The Rosedale diamonds glittered again round the white throat of their lovely owner, who sat at the head of the table.

"I'm glad to have them back again, of course," said Alice Rosedale, and she caressed her gems with dainty finger-tips; "but I'm twice as glad the wretched man wasn't drowned before my eyes."

"Serve him right if he were," growled the angry millionaire. "I thought I knew a thing or two, but he has taken the starch out of my shirt front. The sneaking swindler! How they'll laugh on the other side when they hear I mistook a low-down diamond thief for a full-blooded French count."

"Oh, he was a French count all right," said Mr Beck, "and as full-blooded and blue-blooded as they make them. At the back of that he is the cleverest scoundrel in Europe. He was suspected of a hand in half a dozen big coups, but up to this there never before was a particle of evidence against him."

"Lucky I called you in," said Mr Rosedale. "Your jolly good health, old man!" And he drained a brimming bumper of champagne. "Say, will you take charge of daughter and diamonds as a permanent job, and name your own salary?"

"All right, if I may be allowed to choose my own deputy," retorted Mr Beck, and he laid a kindly hand on Jim Morgan's' shoulder.

"I'm satisfied," cried the millionaire, heartily.

"And you?" whispered Jim Morgan to the blushing girl beside him.

"Certainly not," she answered sharply, yet Jim Morgan seemed quite satisfied.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.