RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Liberty, 7 July 1931, with "The Woman With the Green Mole

James Francis Dwyer

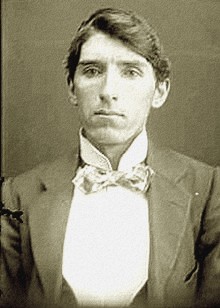

JAMES FRANCIS DWYER (1874-1952) was an Australian writer. Born in Camden Park, New South Wales, Dwyer worked as a postal assistant until he was convicted in a scheme to make fraudulent postal orders and sentenced to seven years imprisonment in 1899. In prison, Dwyer began writing, and with the help of another inmate and a prison guard, had his work published in The Bulletin. After completing his sentence, he relocated to London and then New York, where he established a successful career as a writer of short stories and novels. Dwyer later moved to France, where he wrote his autobiography, Leg-Irons on Wings, in 1949. Dwyer wrote over 1,000 short stories during his career, and was the first Australian-born person to become a millionaire from writing. —Wikipedia

"I sprang between them. 'Go away!' I

shrieked. 'You cannot have my son!'"

DURING the years 1922, '23, and '24 I followed a strange profession. I offered through advertisements in the American magazines to send each week from a different city a two-page letter and a picture of the town. After six months of advertising I had over a thousand subscribers. In that period I sent out more than one hundred and fifty thousand letters from one hundred and fifty towns in Europe and Africa. I am forced to tell of this because my story has a lot to do with the business I followed during those years.

In February, 1923, I rode from Algiers to Biskra. I stayed at the Royal Hotel on the Avenue Delacroix, and startled the post-office officials by thrusting into the mail ten hundred letters for the United States.

I thought Biskra an overrated place, and to kill the great discontent in my soul I walked into the baked countryside by the Route de Touggourt. At a kilometer from the town I came to a small café rejoicing in the name of Café du Printemps. There was a cool terrasse shaded by a large grapevine. I sat myself down and ordered a picón and grenadine from an Arab boy.

I watched the hot road. Plodding camels passed, grunting and squealing at their owners, who whacked them continuously; an occasional auto carrying American tourists.

Suddenly I was aware of a woman on the terrace. She bowed to me; I judged her to be the proprietress of the little café. We began to talk. I asked simple questions about the saison, tourists, climate, and her own clientele. In return for her information I told her a little about myself. Just a little. I knew that she could not understand my métier if I tried to explain about the Travel Letters, but I got over this by saying that I was a reporter, un écrivain, who traveled constantly and reported what he saw to tourists who were preparing their itinerary.

The fact that I traveled from one place to another interested her greatly. She questioned me about cities that I had visited. A strange woman, I thought. Slim, graceful, sad-faced; somewhere in the forties.

"I came to Biskra with my husband in the year 1905," she said, and her voice was soft and pleasant in the stillness of the hot afternoon. "My husband's name was Marcel Lieutard. He was killed by an Arab on this terrace. The Arab was insane. Marcel tried to put him out of the café. The Arab knifed him while they were wrestling. Marcel died before I could reach him."

The woman told of her husband's death in such a casual manner that I felt she had something more important to tell to me. I was sure that the tragedy had been handed to me as a sort of apéritif to whet my appetite for a more sensational story.

"When did this happen?" I asked, probing for the pièce de résistance.

"Seven years ago," she answered.

"And you have lived alone here? "

"We had a son." Her voice was very low. "He was twelve years of age when Marcel was killed. My son's name is Henri."

THE woman remained silent for several minutes. Then she turned suddenly toward me and asked a question. "When you travel around from place to place do you visit the fairs?" she inquired.

"Do I visit the fairs?" I cried. "Why, I go to every fair I hear of. I love them. Why do you ask?"

"It is nothing," she murmured, but I could see by her smile that she approved of my liking for fairs. "Tell me," she added, "what you like at the fairs? What amuses you?"

Wondering a little over her curiosity, I told of the attractions that had special interest for me, and she listened intently. I told her that I bought tickets for the raffles and spent hours trying to put a wooden ring around the neck of a champagne bottle. It seemed foolish to tell of my childish doings at fairs, but I felt that I was encouraging her to tell me something—something strange.

When I paused she nodded her head gently and started to speak. The big story was coming.

"Henri was a wonderful boy," she began. "He was so intelligent. And he was handsome. Do you know, monsieur, he read books at an age when most children do not know their letters? And he drew pictures of Arabs and camels that surprised folk who saw them. Also he played the violin."

Listening intently I thought of that immense rotunda of heaven where the most splendid seats are marked: "For mothers who loved greatly."

"He was romantic," murmured Mme. Lieutard. "He dreamed of far-away places. When I was young I too dreamed of distant cities. That is why I married Marcel. When he told me that he was going to Algeria I married him quickly."

Mentally I searched the café for Henri. I couldn't sense his presence. He was not there. I wondered what had happened to him.

"You saw the place where the nomads are camped?" said the widow, gesturing with her hand toward a sandy strip of land half a kilometer down the road. "Well, she camped there."

"She?" I repeated. "Whom are you talking about?"

"The woman," answered madame. "She came here in the springtime. She came in a wagon—a gay wagon that had the flags of many countries on it. It was covered and painted yellow, and her name was lettered on both sides. Yes, her name. Mme. Clémentine it was. A French name, but she was not French. She came from some place in Russia, but she spoke French.

"She came in a wagon. She was

pretty, and she had a manner..."

"Yes, the wagon was gay and bright. And she had a big white horse with an Arab boy to drive it. And that horse was afraid of her. Yes, he was much afraid of her. He was big and bold, with lots of shining brass on his harness, but when she came near him he shivered with a great fear. She slept in the wagon, but she had her meals here in the café.

"She was about thirty. She was pretty and she had a manner. When she walked she walked like the gouverneur général of Algeria, and when she would talk she used her hands and her eyes and her whole body. And if you looked at her eyes you could see the cities that she talked about. It is true. Let me tell you more. She had on her right cheek a green mole. A round green mole. Did you ever see a woman with a green mole on her cheek, monsieur?"

Mme. Lieutard leaned toward me, awaiting my answer. I tried to think of all the fair faces it had been my pleasure and privilege to view at close quarters.

"I cannot remember ever meeting a lady with a green mole on her cheek," I answered. "I might have seen one, but I cannot recall at this moment."

The widow seemed disappointed by my answer. I was puzzled. "If you had seen her you would not have forgotten!" she cried. "It is only a small mole, but—but it is she! It is the woman herself. Do you understand? The devil has put it on her face, like he has put the red spot on the body of the sand spider."

A great curiosity filled me. Mme: Lieutard was excited.

"What did this pretty lady do for a living?" I asked.

"She told one of the future," answered madame. "With the cards and with the sand, monsieur. It was extraordinary. Each little thing she knew. Nothing was hidden from her. She would spread a handful of sand on the steps of the wagon, and you would see yourself up to the very doors of death."

I was amused. I pictured Mme. Clémentine exchanging silly chatter for coin. I am not a moralist. I thought it a delightful occupation for a pretty lady from the Caucasus.

"She read the cards for Henri," cried the widow. "The cards said that he would make voyages—many voyages. I was frightened as I listened to her. I did not wish Henri to go away from me. No, monsieur. There was a little French girl in the Rue du Cardinal Lavigerie that I thought Henri would marry some day. He was but seventeen when the woman with the green mole came. Just seventeen."

"So," I murmured. "Seventeen, eh?"

The woman looked at me questioningly. "You are sure that you have never seen her, monsieur?" she said. "At the fairs that you visit?"

"No," I answered. "I cannot recall meeting a woman like her."

MME. LIEUTARD leaned toward me. "The officers of the caserne thought her a spy," she whispered. "Yes, they thought she was here to collect information. They stopped the soldiers from visiting her wagon."

This pretty Mme. Clémentine was evidently a person. A Mata Hari of the sands.

"The colonel hinted to her that she might find a place more suitable to her health," continued madame, "so one morning she called for her bill and paid it. I was a little upset as I watched her. I could not tell why. I was frightened. I shivered like the big white horse shivered.

"She stood there on the terrace, and she looked at Henri with her strange eyes. And Henri looked back at her like a little bird would look at a serpent. I became afraid. Dreadfully afraid. Listen, monsieur! Listen! I thought that I should set little threads come out from her face and weave themselves around the body of my boy. My boy that I loved! I did, monsieur! Little threads that made him her victim. There are women who have sold themselves to the devil in exchange for the power to bewitch men!

"I sprang between them, making sign of the cross.'Go away!' I shrieked. 'Go quick! You cannot have my son!' I was between them then, struggling to shield Henri from her eyes! Her dreadful eyes that went into his body and into his soul.

"I was pushing at her, clawing at her, praying to the Madonna for help to hold my son!

"We struggled with each other. She was strong. People stopped on the route and watched us fighting. Fighting for a soul! Arabs and soldiers stood there in the road, their eyes upon the terrace.

"I called out to them to help me. They were afraid of her, monsieur! They were! They had seen the white horse shiver as if he had the ague when she came near him. And she knew the future! Yes, yes, they were afraid.

"We fought into the road. She had Henri by the arm. He did not struggle. Not at all. He just looked at her eyes as she pulled him with her. And he could not hear my cries. He was made deaf by her magi©.

"She was strong! So strong! She pushed me to the ground. I caught hold of her by the ankle, but she kicked me in the face. She was cruel. She laughed as she kicked me. And Henri did not see that she kicked me. He did not see, monsieur! His eyes were fixed on bar face. He was in her power. She took his hand and they started to run down the road to where her wagon waited,

"I got to my feet and ran after them. I was weak. I fell again. The dust blinded me, but I got up and ran on. I saw them climb into the wagon—my Henri and that woman. I shrieked out to my boy. He did not hear. I fell in the road. But as I lay there I saw the white horse rear in the shafts as he always did; then, at a gallop, the wagon rolled down the route and disappeared in the heat haze.

"The Arabs and the soldiers helped me back to the café. I was stunned. I could not think. I could do nothing. I lay like a dead thing, the picture of my boy in every corner of the room.

"Weeks later people told me that I should have gone to the police. They said the police would have taken Henri from the woman and brought him back to me. But I would not have done that. No, monsieur. You see—you see, I loved Henri better than myself. Better than my life. I knew that he wished to go with her. There was something about her—some magic that he desired. I had never denied him anything. Never! If the police had brought him back to me he would not have been happy. She—she was romance to him. He had to go! He had to go!"

Tears slipped slowly down the cheeks of the widow Lieutard. I sat and stared at her. Her story distressed me. It was so direct, so simple, so convincing.

I pictured the dreamy boy of seventeen, his brain inflamed by the heat of Africa, longing to see things that were far from Biskra.

The tale roused memories of my own childhood. When I was a small boy of twelve, a traveling couple who came to our village informed me that if I could get my mother's consent they would adopt me and take me around the world.

I rushed home breathless and gasped out the news. A deep-eyed, shrewd mother listened to the very end, and I lacked the observation to see the tightening lips, the rising fire in the Irish eyes. With a suddenness that gave me no chance to dodge, a right hand caught me a clip or the side of the head, a left straightened me as I reeled, and another right connected again before I got out of range. Biting comments on my stupidity and the morals of nomads who had neither home nor country fell upon my ears as I fled; and, thinking the matter over at the back of the barn, I came to the conclusion that there were insurmountable objections to the proposed world tour.

The widow dried her eyes and regarded me quietly.

"When Henri left he went in such a hurry that he left behind something that he valued greatly, monsieur," she said, and her voice was very soft in the gathering dusk. "I know he misses it. You see, it was his mascot. It hung above his bed. He—he found it in the desert when he was but four years of age. I will show it to you."

She rose and went quickly into the café. I looked down the Route de Touggourt. Lights were twinkling in Biskra. Lonely Biskra.

The woman slipped back to the terrace. She had a small cedar-wood box in her hands. From this box she took an object aid thrust it toward me. The Arab boy had lighted a lamp in the café. I leaned forward to study Henri's mascot.

EVERY visitor to northern Africa has had offered to

him at each stopping place those curious crystalline formations called roses du Sahara. They vary in size from fragments the size of a quarter to great masses weighing two or three pounds. They are the result of the action of the wind on damp sand crystals, and they derive their name from the fact that the formation takes on the character of rose petals, Interlaced or superimposed.

It was one of these roses du Sahara that the woman had handed to me. The strangest that I had ever seen. The petals had taken to themselves the form of the true cross. The piece had a length of about three inches, with a crossbar of one and a quarter. And covering it completely were the petals. Dame Nature had produced something that was a little mysterious, a little frightening.

The evening was upon us now. My thoughts turned to the walk back to Biskra. The route was unlighted, and in the semidarkness one stood a good chance of colliding with a bad-tempered jack-camel hurrying home to his supper. I attempted to hand the mascot back to the mother of Henri.

"Listen, monsieur!" cried the woman. "Please listen!" She made no effort to take the cross from my outstretched hand. "You have told me that you travel and that you visit fairs. This—this I want you to do for me! A little thing, monsieur! I thought that some day—that some day you would see this Mme. Clémentine and my Henri at a fair! You see, her business is with fairs. She told me that she visits them all. Visits them to tell the future. Please! Please!

I rose to my feet but the woman rushed at me and clutched my arm. I felt a fool.

"You will know her instantly by the mole on her cheek!" she gasped. "By the green mole. And—and Henri will be with her. My Henri! You will make a signal to him. You will call him aside and you will give him—you will give the cross. Take it! You—you will give it to him and tell him that I sent it because—because I knew that he missed it! You will do this for a mother, You will do it for le bon Dieu!"

I PROTESTED. I told her I was overwhelmed with commissions. And this was true, I made an effort to escape. I flung a five-franc bill on the table in payment for the picón and grenadine and I turned, toward the road.

But Mme Lieutard clutched the lapels of my coat and held me.

"I have prayed each day I would find a means of sending the cross to Henri!" she sobbed. "And when you spoke of your wanderings and of your love of fairs I knew that my prayer had been heard! I knew! I knew! felt in my heart that Cod heard my payers, Listen—oh! listen! If you do not find my boy this cross will bring you good luck while it s with you. But you will find him. You will! I know! I know!"

I am an awful fool. Phrenologists in different cities of the world have told me that I am "injuriously weak" on such fine faculties as caution, secretiveness and firmness. I left the Café du Printemps with the Cross of Sahara in my pocket....

I came out of the desert by way of Constantine and Tunis, and thence by boat to Marseilles.

A good place to begin hunting for Henri was in that port of missing men. On a stretch of open ground at the back of the Bourse there was a line-up of battered motor cars and horse-drawn vehicles; and there I became a hunter a dreamy youth and a lady with a green mole on her cheek.

This I discovered on the first afternoon: these shows were not disposed to give any information to an outsider regarding one of their number. It was against the code. I spoke with six forains,and the six cunningly avoided my questions.

Did they know Mme. Clémentine? They might and they might not, I described the gay wagon and the big white horse. They assured me that there were lots of yellow wagons on the road and that showmen had a liking for white horses. But M,e, Clémentine? I persisted. She had a green mole an her cheek? No, they knew nothing of her. Perhaps they had met her, perhaps they hadn't. Europe was big.

Showmen and show-women wander across the face of Europe from St. Nazaire to Perm and from Hammerfest to Catania. There are a million fairs In the course of a year.

I prayed that luck would come to me. And prayer was a novelty to me. In my dreams I saw the lonely widow looking down the dusty road to Biskra, thinking always that she saw an Arab messenger bicycling toward the Café du Printemps with a wire from me reading: "Henri found. He is on his way back to you."

I lived on fair grounds in the hours that I could spare from my work of sending out a thousand letters a week to America.

On I wandered, the ever-present specter of the widow Lieutard walking at my side. Sometimes in the night at little hotels I awoke suddenly and saw her crouched in the corner, her lips moving. I knew what she was saying. I knew. "But you will find him. You will! I know! I know!"

I knew that she was driving me by thought transference. Driving me across Europe in search of Henri.

I copy from my old notebook the names of a few of the towns that I visited during those months. "Monaco, Grasse, Vence, Port Bou, Barcelona, Elne, Gerona, Perpignan, Narbonne, Béziers, Cette, Montpellier, Tarascon, Château-Thierry, Cologne, Brussels, Antwerp, The Hague, Namur, et cetera.

Of course fairs were not in progress in all of these towns at the time of my visit; but where there was a fair I visited it immediately and hunted industriously for Mme. Clémentine and Henri. Three times I met forains who admitted that they knew of the woman, but not one of the three could tell me of her whereabouts at the moment I questioned them. One had had his stand beside hers at the great fair of Seville—La Feria, which is held on the Prado de San Sebastian during Holy Week. Another had met her in Milan. The third had his "pitch" quite close to her in the old city of Nimes.

This last man was more communicative than his brother forains. He had talked with Henri—Henri Lieutard—one time of the Café du Printemps! I was thrilled. He said that Henri was a nice boy. Romantic and fond of travel. Cautiously I probed regarding the relationship between the woman and the youth. Was Henri her lover?

The showman was angry with me. He thought me a fool. He was certain that Henri was not her lover. Then why, I asked, does he stay with her? He ran away from his home to be with her.

A far-away look came into the eyes of the forain. "Most homes seem dull places to romantic boys, monsieur," he murmured. "I ran away from home because I thought it quiet. Didn't you wish to clear out when you were young?"

I grinned sheepishly. Up before my eyes came a picture of a listening mother to whom I chattered of a pair of nomads who wished to adopt me and take me around the world....

IN the month of August I came back to Paris. In a little hotel in the Rue de l'Isly I sat myself down and considered the matter of the Cross of the Sahara. I had taken the search so seriously that the failure to find the boy was affecting my health. The picture of the widow watching the dusty Route de Touggourt hoping for the long-delayed telegram had become a nightmare. You will understand that I am a fool. I am hypersensitive, and small things worry me.

I came to a decision at last. I would send the Cross of the Sahara back to Mme. Lieutard. I would write her a letter telling of my fruitless search, and I would beg to be excused. To me it seemed quite evident that the Almighty had not picked me as the finder of the wandering boy.

Carefully I penned a note, carefully I wrapped up the box that contained the cross. A sense of freedom was upon me.

I walked to the nearest post office with the packet and the letter. I would register them, to make my freedom more secure. I walked to the counter, and there, on the wall space which the frugal French rent out in post offices as we rent billboards, I saw an announcement of a fair at St. Cloud!

I put the packet in my pocket and walked toward the Seine. It was a Saturday afternoon, fine and sunny. I would give Henri one more chance.

I took a boat at the Quai du Louvre. The river looked lovely. The hills of Meudon were especially beautiful.

I told myself that the outing would do me good. Of course I wouldn't find Henri, but what matter? I could mail the packet and the letter when I got back to town.

The fair was in progress at the entrance of the great Parc de St. Cloud. Slowly I walked along the midway. There were many attractions that I had seen in other cities. They were like old friends to me. There was "La Belle Paloise," who was advertised as the heaviest woman in the world; "The Spider Lady," who sat in an iron cage with the supposed bones of men around her; and there was "Nature's Puzzle: The Half Man, Half Woman," who had been arrested more times than any other freak in the world.

I had reached the middle of the line when I stopped suddenly. I was looking at a covered motor van—a fine, brave van with the flags of many nations flying from it—and upon the smooth yellow sides were the words: "Mme. Clémentine, Seeress."

I moved forward like a person in a trance. I bumped against folk and neglected to apologize. I was staring at a dais built at the end of the car. Upon this platform was a woman of some thirty-odd years, a pretty woman, and upon her right cheek, plainly visible in the afternoon sunshine, was a green mole!

Much excited, I looked for Henri. The youth was not in sight. A big, square-shouldered man with the face of a bully was passing slips of paper to the persons who milled around the dais. When the seeker for information had written a question upon the slip, the big man collected a franc from each as he passed the papers to the woman.

Mme. Clémentine was busy. Fearfully busy. Francs were pouring into the treasury. From the movements of her hand I came to the conclusion that she wrote a simple "yes" or "no" on the slips handed up to her, and the speed with which she worked proved that she gave little thought to the questions.

THE inquirers, after their papers had been handed to madame, pressed forward with uplifted hands to receive answers; but although they kept a sharp watch on their own slips, there was quite a little confusion. A girl who had asked if her Pierre would marry her before Christmas received back a slip on which Mme. Clémentine had written an emphatic "no" to a query that read: "Will I have twins?"

The attendant with the face of a prize fighter thrust a question paper in my face. I accepted the sheet, scribbled a query, paid a franc, and saw the slip passed to the woman on the dais.

Immediately I regretted my action. I became suddenly afraid of the woman. I recalled the story told me by the widow on the Route de Touggourt concerning the terror that gripped the white horse when Mme. Clémentine approached. Well, on that crowded midway at St. Cloud I became fearful of her. There was something malign about that lady, something wicked and sinister. Yet there was a fascination about her. A curious fascination.

I backed hurriedly out of the crowd. I took shelter behind a wagon. I watched her with unblinking eyes as she worked quickly through the papers. She came to mine. I knew it was mine, because I had turned down the corner of the slip lest the big man read it while handing it up.

She lifted her pencil to write the usual "yes" or "no," but she did not write. For a minute or more she stared at the slip; then she sprang to her feet. She was angry—very angry. Her eyes blazed as she stared at the milling crowd.

"Who has written this?" she cried. "Who wishes to know the whereabouts of Henri Lieutard? Who asks?"

The bully rushed to her side and stared at the paper. He glared at the crowd, apparently ready to pounce upon the writer. For an instant I felt certain that they had murdered Henri.

The woman started to speak. She was excited; her voice was high-pitched. "I am not afraid to tell where Henri Lieutard is!" she cried. "He is in the wagon, asleep! Does anyone wish to know more?"

There was silence. The clients were startled by the outburst. I kept in my shelter, a little upset by the commotion I had caused.

Madame sat down. The bully tore up the slip upon which I had written my question. He spoke in an undertone to the seeress; she listened impatiently and waved him away. The work of divining the future began anew. But the snap had gone out of Mme. Clémentine. She watched the crowd with hard, suspicious eyes. The green mole glowed like an emerald. I had a belief that her temper increased its viridescence.

I moved away from her stand. Was Henri really in the van? My curiosity parched my lips and throat.

It was now five o'clock. With no plan within my brain, I watched the van and madame. Watched from a safe distance. I was certain that everything was not right with Henri Lieutard. If he ever needed a mascot I was sure that he needed one at that moment. The assistant had a murderous mug, and madame's eyes were not those of a saint as she screamed the challenge after reading my query.

Toward seven the attendance dwindled. Women rushed home to prepare meals; hungry husbands followed them. The showfolk started to prepare their own suppers. The odors of various kinds of stews were wafted along the midway.

Mme. Clémentine descended from her dais. She opened the door of the covered motor van and disappeared within. The big-jawed assistant followed. I crept behind some packing cases and watched.

Madame and the man reappeared. The seeress had thrown a gay Spanish shawl over her shoulders. The man locked the door of the van, put the key in his pocket, and took the arm of the lady. My heart was pounding mightily as I watched them turn toward the town. The two were going to sup in some café of the neighborhood. No ordinary forainswere they.

I watched them clear of the midway, then crossed hurriedly to the van. I put my lips to the keyhole in the door and called the boy's name. "Henri!" I cried. "Henri Lieutard!"

A choked Oui, oui!" came from within. Breathlessly I explained myself. In words that tripped over each other, I told of meeting his mother, of her story, of her action in confiding to me the Cross of the Sahara.

Cries of astonishment came from the van. I heard noises that suggested a struggle. But the door remained shut. I placed my ear against the keyhole. Someone, presumably the youth, was rolling on the floor of the van. I judged that Henri was a trussed-up prisoner.

"Come to the front of the van!" he gasped. "Quick! Quick!"

I rushed to the front of the machine and climbed up on the driver's seat. There was a heavy lattice of wood behind this seat. In the dim light I could see the face of the young man within.

"A knife!" he shouted. "Open it and push the blade through the slats! My hands are tied!"

At that moment I wished that I had never visited the Café du Printemps. Imagination leaped forward and painted a little picture that chilled me. I thought of my thousand subscribers scattered over the United States who would be waiting vainly for their weekly letter while I cooled my heels in a French jail.

It was too late to retreat. I thrust the blade through the slats, holding fast to the handle. I felt the movements of the youth as he pushed his bound wrists against the steel in an effort to cut the cords.

A cry of joy came from his lips. His hands were free. Breathlessly he asked for the knife. I passed it to him. He hacked away at other bonds on his legs and body. The big man and Mme. Clémentine had taken no chances with their prisoner.

"Stand clear!" he shouted. "I am going to smash the slats!"

I leaped to the ground, and as the wooden slats splintered under the blows from within, I made a discovery. A head peered around the side of the van; a small man with a keen face slipped to my side.

"Police," he murmured softly, and as Henri Lieutard crashed through the opening and dropped to the grass

I knew that we had the undesired company of a member of the Paris Sûreté, that clever band of crime trailers noted for their tenacity and intelligence.

Henri Lieutard screamed for his mascot. "La Croix!" he cried, his hands outstretched. "La Croix du Sahara!" I thrust the thing into his groping fingers. He stammered his thanks as he brought it to his lips. He seemed a little insane. Insane with joy.

THE Sûreté man took a hand at that moment. He had a clutch on Henri's jacket. Questions poured from his thin lips. This Mme. Clémentine—who was she? And the man? Quick! Quick! He urged Henri to tell everything. Why was she traveling around France? Why was she friendly, so friendly

with soldiers?

Henri Lieutard answered in a choked voice. He, Henri, had become suspicious of madame and her partner. He had made an attempt to leave them. The big man had beaten him. Together they had tied him up. For days he had been a prisoner in the van. It was dark behind the van. The Sûreté man flashed a small torch on Henri's face. There was visible evidence of a battle. The boy's right eye was closed and a large lump of sticking plaster decorated his nose. The detective was convinced that he was speaking the truth.

"Stay where you are," ordered the officer. "Both of you. I am going to search the van."

He climbed in through the aperture made by Henri, and for a few seconds we watched the beams of his flashlight as he poked around. For a few seconds only. I touched the arm of Henri. "Let's run!" I gasped.

Henri had no objections. We stepped softly into the gloom; then, keeping away from the lighted midway, we made for the town, running swiftly at the rear of the parked vehicles of the forains. We slackened speed as we came toward the Pont de St. Cloud. I swung toward the boat landing, but Henri gasped out an objection. Un moment!" he cried.

Along the banks of the river were half a dozen small cafés of a questionable character. The youth peered through the window of the first, shook his head, and rushed to the second. I was beside him as he looked through the dirty glass. Sitting in a corner were Mme. Clémentine and the big man who had administered the thrashing to Henri. They were drinking beer; the right arm of the bully was around the neck of the seeress.

Henri Lieutard slipped a franc to a waiter standing at the door and whispered a message. It was quite dark on the terrace of the café. The waiter hurried to the big man. The fellow listened, excused himself to Mme. Clémentine, and came at a trot toward the door.

He stepped on to the terrace, peering into the gloom, unable to see the crouching youth. And that moment of unguarded hesitancy was his undoing.

Henri Lieutard flung himself upon the bully. An unleashed panther was the boy. Fists flailed the face of madame's companion. They beat a tattoo on his nose and eyes. He staggered backward, unable to recover from that first fierce rush. A swinging right rocked him, and a flashing uppercut sent him sprawling into the roadway.

He staggered backward, unable to

recover from that first fierce rush.

I clutched the arm of Henri Lieutard. I pointed to the river. The Seine boat was sweeping down from Suresnes to the landing below the bridge. Clinging to his wrist, I started to run.

We passed the ramp of the bridge. I looked in the direction of the café. In the shadowy figures running toward it I recognized the figure of the Paris Sûreté man who had ordered us to wait. He was in the company of two local agents de police who ran beside him.

We sprang upon the boat as she was pushing off. A deck hand damned us as he helped us to keep our footing. Ahead lay Paris....

This Henri Lieutard was no talker. During the run to the Pont Neuf we had little conversation. He asked me half a dozen questions about his mother. Also he thanked me for the trouble I had taken in locating him. Several times on the journey he took the Cross of the Sahara from his pocket and looked at it intently. Once when I turned my head he brought it quickly to his lips.

We landed and walked up to the Quai du Louvre. He paused on the quai and stood for a moment as if considering some question. His lips moved but words refused to come. A strange, sensitive lad was Henri Lieutard.

After a few moments he got command of himself. "I —I am going home/' he stammered.

"To your mother?"I asked;

"To my—to my mother," he whispered.

I asked him if he had money. He said he had sufficient. He hailed a passing taxicab. We shook hands. He thanked me again and climbed in. The chauffeur repeated the direction: "Gare de Lyon, monsieur. Oui, oui, monsieur."

I stood and watched the taxi disappear in the soft night. I felt curiously lonely. The Cross of the Sahara was a comforting thing, in its way....

On the way back to my hotel I found a telegraph office open in the Rue de Grenelle. I wrote a message and handed it in. The telegram read:

MME. MARCEL LIEUTARD, CAFE DU PRINTEMPS,

ROUTE DE TOUGGOURT, BISKRA, ALGÉRIE.

YOUR SON HENRI STARTED FOR HOME THIS EVENING. HE HAS THE CROSS OF THE SAHARA IN HIS POCKET.

(SIGNED) L' ÉCRIVAIN AMERICAIN.

"When will it reach Mme. Lieutard?" I asked.

"Demain matin" answered the clerk.

As I went out on to the street I pictured the widow watching the Arab messenger pedaling toward the café on the Sabbath morning with the message that would bring joy to her heart....

L'Intransigeant of the following Tuesday carried an interesting morsel of news. The paragraph read?

Yesterday the police escorted to the frontier a Russian woman of the name of Mme. Clémentine and her companion, a man named Bazarov. Both are suspected of espionage on behalf of the Soviet. Both spies had wandered around France and her colonies disguised as showfolk.

After reading this far I sat back and calculated the time that had elapsed since the moment I said good-by to Henri. I came to the conclusion that he was, at that very moment, entering the little café on the Route de Touggourt. I felt very happy.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.