RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

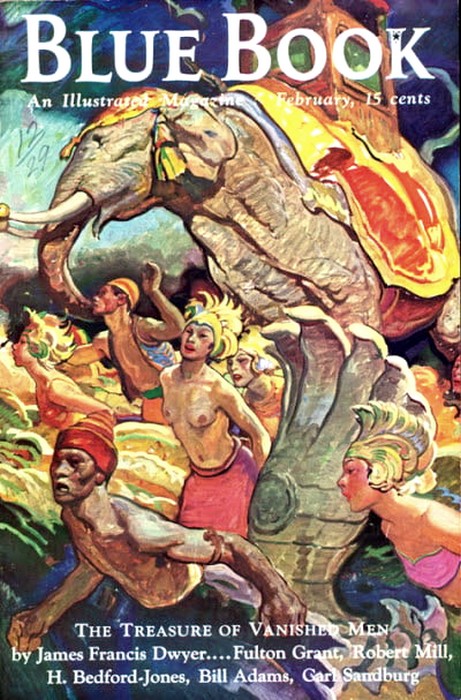

Blue Book, February 1937, with first part of

"The Treasure of Vanished Men"

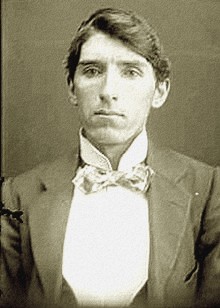

James Francis Dwyer

JAMES FRANCIS DWYER (1874-1952) was an Australian writer. Born in Camden Park, New South Wales, Dwyer worked as a postal assistant until he was convicted in a scheme to make fraudulent postal orders and sentenced to seven years imprisonment in 1899. In prison, Dwyer began writing, and with the help of another inmate and a prison guard, had his work published in The Bulletin. After completing his sentence, he relocated to London and then New York, where he established a successful career as a writer of short stories and novels. Dwyer later moved to France, where he wrote his autobiography, Leg-Irons on Wings, in 1949. Dwyer wrote over 1,000 short stories during his career, and was the first Australian-born person to become a millionaire from writing. —Wikipedia

A fascinating novel by the author of "Caravan Treasure," in which those

wild hawks of trouble, Thurland and Flane, seek the riches of Angkor.

THERE are days in spring that are so splendid," said my Uncle Thurland Spillane, "that the dear Lord rubs His fine hands together and He says to the listening angels: 'Let's be doing something.' Days like the one that is wrapped around us this blessed minute."

Flane Spillane looked slyly at his brother and laughed softly. After a pause Thurland went on, talking as if speaking to himself.

"It was on a day like this," he said, "that Marco Polo, that fine Venetian, started out for Cathay. For Cathay!The words are so sweet that they near choke me. And I'll wager there was the same thrill in the air when the great Sir Francis Drake swung the Golden Hind out of Plymouth harbor to circumnavigate the world. And although it was autumn when Columbus went aboard the little Santa Maria to discover the big wide country of America, I'll bet the Almighty had put the spirit of adventure into the scented winds of Palos. For there are days made by Him that whisper to brave hearts, and on those days things happen. Yes, things happen."

The words of my uncle Thurland Spillane, himself a Marco Polo out of Kerry, were thrilling to my ears. For Thurland was a god to me. Flane, who had rescued Thurland from the terrible abyss into which he had fallen when seeking the treasure guarded by the Woman with Feet of Gold (I told about that last year, as you may remember, in "Caravan Treasure"), was some one whom I loved and admired—but Thurland I worshiped. Thurland had been chosen to walk with the Angel of Great Happenings. The lean prideful head, the venturesome nose, the bold eyes that looked out like two spearmen on a castle wall, marked him as a wild hawk of trouble who brought the yeast of adventure into a world grown dull with fat and careless living....

We were, to my great delight, for T was but a boy of seventeen, sitting at a little table before the Café de la Paix; and all Paris streamed by us as we rested in the soft yellow sunshine. Paris, the blonde of the great cities—Paris, that, as Thurland said, "wears high heels that are a little turned because she has done a lot of walking."

All the trees along the Boulevard des Capucines were dressed up with tiny leaves as green as any that you'd find in sweet Kerry from which we had come. And the air was filled with the kisses of spring. Flane gave a sigh of contentment and sipped his drink. "It is certainly a fine day," he said; "and it is a pity we have nothing better to do than sit here in the sun and watch the world slip by us. What are you thinking about, Jimmy?"

"I was thinking about my Aunt Anastasia," I answered. "I bet she would like Paris."

"She's better off at the Green Tree Farm in Kerry," said Thurland. "There's peace and quiet there and that is better for her at this time. Paris is too heady. Some cities are worse than whisky. They make you drunk with the queer magic that is in the air. Places like Stamboul, and Cairo, and Fez, and Paris. You believe everything that you see and hear, just the way old Paddy O'Brien believed the leprechaun, when the leprechaun told him to put his gold under a stone in the potato-patch, and he would find twice as much in the morning."

"And did he?" I asked.

My uncle didn't answer; his eyes were fixed on three persons who had come to one of the little marble tables immediately in front of us: two men and a girl.

One of the men was a gray, foxlike person with shifty eyes and a mean, hard mouth. There was a moneylender in Kenmare with just such a mouth, the lips of him, ashamed of the hard words they had uttered, having turned inward so there was only a mark like two inches of dirty string to show where his mouth was.

And with this man was a youth and a girl that had the chrism of holy love upon their foreheads: a girl as beautiful as Deirdre of the Sorrows, with a soul as white as bleached linen, the big eyes of her filled with admiration for the flushed youth who was answering the cunning questions put to him by the man with the mean mouth.

IT seemed from the answers he gave, that the foxy man was a stranger to them. The queries were made in a whisper, but we could hear quite plainly the responses that the young fellow made to them. He and the girl, said the boy, proudly, were on their honeymoon. They came from a town called Dover, in the State of New Hampshire, and it was their first trip abroad. "We have," he said, and there was a fine note in his voice as he made the statement, "been married fourteen days! Just fourteen days!"

Now the man with the mean mouth put his elbows on the table and leaned toward the boy in the manner of a person who has something wonderful to tell. And as the boy listened, he got flustered as if he didn't like the talk of the other. And now and then he would turn his face toward the girl as if he thought a glance from her would help him out of the web that the other was spinning round him. The cunning web that the spiders of the Grands Boulevards spin around the innocents who come to Paris—the innocents who wander up and down like lost lambs in the jungle; for as Thurland remarked, that lady called Paris, with her dyed hair and her turned heels, shelters a lot of wolves who prey on the untraveled ones who come to see her.

Clever are the wolves. They will show the innocents this and that, and in the end they will blackmail them and rob them; and if they go to the police, they will get no satisfaction at all.

Now my Uncle Thurland was listening without appearing to listen. For he had a way like that; his eyes made a fine pretence of watching a comedy between an Arab rug-seller and a woman on the sidewalk; but they saw as well the flushed features of the boy and the growing distress on the face of the girl. And although I couldn't hear what the mean-mouthed man was saying, I think Thurland heard. Or he may have guessed, he being wise in the way of scoundrels, knowing cities in every part of the world.

The youth made an effort to break the web of the spider. He tried to rise from his chair, but the man put out a claw and drew him down again. And his whispering went on and on, words that were the devil's glue.

Now the boy caught the eye of my uncle, and something that he saw there made him stare so hard that the spider who was putting the web around him turned to see what he was looking at—turned and looked at Thurland, who eyed him the way a terrier would eye a rat.

FOR a few moments the man stared at Thurland, with his lean throat quivering as he gathered up his courage; then he spoke. "Are you listening in on other folks' business?" he asked sneeringly. "Have you nothing of your own to worry about?"

Now, before my uncle on the marble table was a half-tumbler of whisky and soda, with a big spiky lump of ice in it. With one hand Thurland grabbed the coat-collar of the fellow, pulling it away from his neck so that he made a funnel; then with the other hand he picked up the glass and poured the whisky down the spout he had made between coat and skin. And the piece of ice went with it!

It was done with a simplicity that was surprising. The speed and a sort of carelessness held for a moment those who had seen it. It held even the man with the hard mouth, the cool manner of the attack keeping him in his chair while you could count five.

He sprang to his feet then, his cane uplifted as if he would strike Thurland, but those eyes of my uncle held him. Spitefully they held him as he stood with his arm uplifted. Then, turning his head, he screamed "Police!" at the top of his voice; and the agent on the corner of the Place de l'Opéra came at a run.

"Qu'est-ce qu'il y a?" cried the agent.

In hot French the man told him what had happened. He had been sitting with friends, he said, and a man he didn't know from Adam poured a glass of liquid and a lump of ice down his back. From somewhere near his stomach he found what was left of the spiky piece of ice, and held it out to the agent as proof of what had happened.

The surprised policeman turned upon my uncle, his notebook in his hand. "Et pourquoi avez-vous agi ainsi?" he cried.

Thurland looked bored. "It was a mistake," said he carelessly, speaking in French; "I thought he was some one else." He smiled when he said this, and he looked hard at the fellow with the mean mouth. "I thought," he went on, "that he was a man that I met once on the Unter den Linden in Berlin—a cunning devil of a man who called himself a colonel, but who was no more a colonel than I am myself. A fine confidence man, he was. Many and many a tourist he flayed with the Rosary trick and other methods. The police were hot on his trail, but he dodged them. He called himself Colonel Considine; but his real name was— Hold on, my friend; I'm telling why I poured the whisky down your neck!"

But the fellow didn't wish to hear any more of my uncle's explanation. He broke through the ring of waiters and clients, and went at a run across the Place in the direction of the Boulevard des Îtaliens, dodging the cars whose drivers cursed him.

The surprised agent watched him till he was out of sight, then he turned and looked at Thurland who was laughing softly.

"Monsieur," said the agent, "I would like your name and address in the event of the complainant visiting the Bureau de Police."

Thurland laughed louder when the small policeman said that, and he patted him affectionately on the shoulder. "It's a bright boy you are to think of that," he said. "My name is Thurland Spillane, but as I travel a lot, the only address that will find me is the Green Tree Farm, on the road from Glengarriff to Kenmare, County Kerry, Ireland."

When the agent heard the strange names, he snapped his notebook shut, gave a snort of disgust and went back to his post. For the French believe that they have the finest language in the world, and it's only when a foreigner is ordering drinks or food, that they'll make an effort to understand him.

The young man and the sweet girl had stood close to Thurland during the talk, and now the youth spoke. "I know that you did that for our sake," he said simply. "You see—you see he spoke to us, and— and we couldn't get away from him."

"Sure, I know," said Thurland, shaking the hand that the young man put out. "Paris is full of them. If I were you, I'd speak only to the pretty colleen at your side."

The two blushed and walked away. Thurland sat down and spoke to the waiter. "Bring me another whisky," he said, "and don't put the ice in it till I see how much whisky is in the glass. It was the very weakness of the last drink that tempted me to pour it down the neck of that crook."

"Well," said Flane, after the waiter had brought the drink, "there's no harm in starting things. Do you remember Tommy Boylan, who thought to start a friendly conversation with a girl in Kenmare by saying: 'That's a hell of a hat you're wearing.'"

Thurland laughed, took a sip of his drink, then looked up at a man who had risen from a table at the very edge of the terrace and approached my uncle.

"PARDON," said the man, bowing like Mr. Delaney the dancing-master at Glengarriff. "I was listening when you gave your name to the agent. Did I hear it correctly? Are you Mr. Thurland Spillane?"

Thurland looked at the man before he answered. He was small and thin, with the face of a very intelligent sparrow. And in his eyes was a light that you might think was queer, but which was but the glow from the very active brain behind them, as we found out in the days that followed.

"You heard correctly," said Thurland.

The man took a card from his pocket-book and handed it to my uncle. "You might not recognize the name," he said, "but you might remember meeting me one night at Belgrade, when you were in the company of the Baron St. Ladau?"

Thurland glanced at the card and got to his feet. The cold manner in which he had received the inquiry about his name had fled, and he pushed forward a chair for the stranger.

"My brother," he said, indicating Flane; "and this is my nephew."

The small man bowed to each of us, and murmured something about being enchanted, which we knew wasn't true; for it was Thurland that he wanted to speak to, and no one else. No one else in all Paris, if one could judge by the satisfaction that was on his face and the wild excitement that showed in his words and actions. And as I looked at him, I thought that the Angel of Great Happenings with whom my uncle was permitted to walk, had heard his words about the beauty of the day and had created the little incident with the confidence-man as a curtain-raiser for something big and wonderful. That is what I thought, and what Flane thought as we watched the small man. For he had the pleased look of a terrier who has found his master after losing him in a crowd—a queer delight that bubbled out of him.

He wished to buy champagne, but Thurland would have none of it. And he got so excited that he couldn't speak at all, sitting and looking at Thurland. And all Paris swam by in the sunshine, the English and Americans, the Swedes, Germans, and Italians; and the four of us sat at the little table while the Fates were mixing the batter in which we were to stew and sweat in the months to come. Mixing it in the big mortar in which all adventure is mixed with the pestle of discontent.

A CHAUFFEUR in uniform broke in on our quiet. He addressed the small man, who turned to Thurland. "I want to talk to you," he said, "but I cannot speak here. At my house, yes? I live at Neuilly, and my car is here. Would you—you and your brother and your young nephew—would you come and have lunch with me? Yes?... Good."

Still laboring under the excitement caused by his meeting with Thurland, he led the way to a big American car that stood at the curb. The chauffeur opened the door, and we climbed in.

OH, a fine town is Paris, with its big broad boulevards. And never, I am sure, did it look finer than on the day we rode in the big car along the Avenue de la Grande Armée—and was ever a better name given to a street? And it was only when the car pulled up before a mansion, sitting like a fine lady in its own park, that Flane and I knew the name of the man with whom we were riding, Thurland spoke it. "No, Count Zavrel," he said, in answer to a question as to whether he was engaged in anything at the moment, "I am free for the time being at least, as Mike Hennessy said when he broke out of the jail at Tralee."

In the wide hall of the mansion a girl sprang upon the Count and hugged him wildly—a girl who was like the spring day, she being bright and smiling and full of life. A girl of twenty or so, slim and straight, who looked up at my two big uncles with an astonished grin on her pretty face.

"My niece Joyeuse," said the Count; and Joyeuse shook hands with us in turn, laughing as if she found something amusing in the fact that her uncle had collected us on the streets of Paris and brought us home for lunch.

"Joyeuse is a tomboy," said the Count, smiling at her. "She is an American, and has been given too much freedom. Now, I am afraid, she has come into my charge too late."

While the girl rushed away to give orders for the luncheon, the Count explained to Thurland that his sister had married an American, and that Joyeuse was the only child of the marriage. Both parents had been killed in a motor accident in California, and he had taken the girl under his care.

"But I cannot control her," he said dolefully. "If she had been brought up in my country, it would be different; but in America young girls do what they like. Je suis desolé."

He made a face as if he was dissatisfied, but we thought that he was delighted with the smiling Joyeuse, who now came back to inform him that lunch was ready to serve.

Now, of that lunch and the matters that followed, it is hard to tell. For the pouring of a glass of whisky and water down the neck of a scoundrel had brought us into an atmosphere of wonder and magic. And we heard things that savored of witchcraft, and black magic— things that might have been unbelievable if you heard them in any other city but Paris.... For in the quiet cities of the world, cities like London and New York, people are thinking of business and commerce, and go about their work soberly with no expectation of strange things coming into their lives at all. But in Paris, men and women dream of marvelous things happening to themselves, and many a fool sees dream-chariots on spring days in the Tuileries, and themselves riding battle-chargers in the wisps of sunshine above the Seine.

The Count Zavrel, so Flane and I discovered during the luncheon, was a Russian. He spoke English in a way that was better than an Englishman, because, and this was curious, he used the little mistakes he made in such a manner that he doubled the value of his words by his confusion. And he was an artist with words—a great artist, knowing their value and their appeal: bringing them forward in their proper order, the strong fierce words that have power and strength, and the fine-colored ones that bamboozle the listener with the beauty in them when they are uttered softly.

IT was when the lunch was finished that he started—cunningly, very cunningly. He laid in a background like one of the old painters, and although Thurland and Flane might have known what part of the earth he was speaking about, I didn't. That it was a place far away on the fringe of the world I guessed; but the name of it was a mystery to me. And at times I wondered if it was a real place, or if he was romancing like a story-teller in the Arabian Nights.

A fine tale he told. It was the history of a people that I had never heard of—a history that ran back over the centuries, so that most of it was but the gabble of ancients and had fine fat lies twisted into the bits of truth. It told of the start of this people who founded a kingdom. How their chief, out walking one day, came to the entrance to a hidden place where the people worshiped a snake-god they called Naga, a god with seven heads, and from that day they grew great.

"That was the beginning of the Khmer dynasty," said the Count. "The beginning of their greatness. They had, or thought they had, architects that were sent to them by the snake-god, and they built cities and palaces of great splendor. They built Angkor in the Ninth Century of the Christian era, and the modern world didn't know of its existence till forty years ago: It was buried in the great forests, dead and deserted for hundreds of years, till the French stumbled on it. Great towers that ran up two hundred feet in height; courts in which an army could rest; carvings and sculpture that the critics of the world think wonderful. And it was there in the forest with no life in it but the great bats that slept in it, by the millions and millions."

THEN it was that my Uncle Thurland spoke. "But there's nothing in Angkor now," he said coldly, as if he wished to steady the high talk of the Count. "I haven't been there myself, but I have spoken to men who have visited it. There's nothing there but ruins and bat's-dung and muck that the French are clearing out, hoping to get American tourists to come and see it."

The Count smiled, and looked at Thurland as a wise man would look at a smart boy. "You are quite right," he said. "There is nothing in Angkor. I speak of it only to whet the appetite. It is a little cocktail in words. It is just because there is nothing in Angkor that I mentioned it at all.... Why is there nothing in Angkor?"

Thurland grinned. "Some one took it, I guess," he said.

"Some one took it," repeated the Count slowly. "Some one took it; What fine words those are to explain the great happenings in the world! They explain everything without explaining. Listen. In the Fourteenth Century something happened to Angkor. We know that from the annals. What was it? You do not know?"

"I don't," said Thurland stubbornly.

The Count was upon his feet now. He was excited; his eyes shone; his features twitched; and the words were flung from his lips angrily.

"I will tell you!" he cried. "On a day in summer something came up from the marshlands of the coast I. Up by Phnom-penh! Creeping up the Mekong! Through the Tonlé-sap to the Grand-Lac! Something that squatted on the great terraces of Angkor-Vat and grinned at the yellow-robed monks that chanted their prayers!"

The hair on my neck prickled as I listened to the Count. And the heads of Thurland and Flane were thrust forward. In my mind I pictured some enormous animal, a cross between a hippo and a rhinoceros, swimming up to a far-off city and playing the devil with the little shops, the way Finnegan's red-and-white bull did when the flies got him mad at Glengarriff fair.

The Count had lifted his right arm, and now he lowered it gently as if pulling down a switch that gave the answer.

"It was the Plague!" he whispered. "The Plague!"

A terrible word is that word plague; It's a word that sounds black. "The Black Death," it was called in Scotland and Ireland hundreds of years ago, when it mowed down the people; and there was the "Great Plague" that swept London, when they marked the houses with a red cross and the words "God have mercy on us," and the dead-carts rumbled by in the night collecting the bodies the way they collect refuse in big towns today.

But of all the tales of plagues that I have ever read of or listened to, that story of the Count's concerning its coming to Angkor was the most thrilling. Perhaps it was the way he told it; but I know that it filled me with a sort of terror: I felt in a way that I was there with the stricken people, running and screaming and praying to the snake-god Naga who had deserted them.

In their thousands they dropped before the invisible hand that came across the great lake. Men and women and little children. Soldiers and servants, the rich and the poor. And they lay where they dropped, for no one would give them burial. Yes, they lay as they fell, the living stumbling over them.

"THEN," cried the Count, "the king ordered the evacuation of Angkor. They must leave, because the snake-god Naga had cursed it. A thousand pirogues made out of the trunks of the great trees that are called koki, pirogues with forty rowers in each, were gathered on Grand-Lac; and the king and his hundred wives, and the nobles and their wives went aboard them, leaving the poor of the city to shift for themselves.

"And into the pirogues they put the treasures of Angkor: The great pearls that came from Jiddah and Koseir, rose-colored like those that Marco Polo had seen placed in the mouths of the dead in the city of Ta-pin-zu; pearls that had been soaked for seventy days in the milk of white mares to increase their luster! Great emeralds that preserved the chastity of the women who wore them, so it was said; diamonds that made men invisible; and enormous rubies that were thought to be the eyes of dead snakes. And gold! Bars of gold that weighed down the pirogues till the rowers screamed in fear. And in the dark night, with the soldiers beating off the poor who tried to rush the boats, the great line of pirogues streamed across Grand-Lac, heading for the Mekong. And the plague got fiercer at Angkor, till the few that were left alive fled into the forests, and the bats moved into the great halls and towers—where they lived in the millions till the French came five hundred years later to evict them."

INTO the eyes of my Uncle Thurland came that strange look of treasure-lust that I had seen there on our journey to the Black Mouth. And Flane wet his lips and swallowed, as if he believed he had one of the rose-colored pearls in his own mouth. And myself I was pop-eyed with the wonder of the tale, and my chest felt as if an iron band had been put around it. I looked from Thurland to Flane, and then to the face of the girl Joyeuse. She alone was calm. Perhaps she had heard the tale before.

Thurland woke out of the trance put upon him by the story. He shook himself, shifted his great long legs, let a half-smile run over his face and then put a question: "And where did they go?-" he asked. "The pirogues, I mean."

The Count didn't answer. He moved toward a bell-button and pressed it. While he waited, he looked at his two clasped hands, and into the silence of the great room came the far-off whisper of Paris—the never-ending whisper. Day and night it goes up; for Paris is the City of Tongues that are never still, and tongues that have little wisdom in them.

A servant came into the room, and the Count spoke: "Faites venir le bonze. Vite!"

Now, I didn't know what a bonze was at the moment, but I learned in the hours that followed that it was the name given in Indo-China to one of the begging monks who spend their lives in the pagodas, praying and thinking about paradise to come. In a few minutes the bonze appeared, led by a French servant who was his guard and attendant; and when he came into the room the Past came with him. That Past about which the Count had been speaking. For the man was older than any other man we had ever seen! Older by years and years.

His age was like a whip that struck us across the eyes, making us blink with a queer pain; and I know that I caught a strange odor when he came through the door—the musky odor that they say comes out from crocodiles of great age. And when he stopped walking, and stood in a patch of sunshine, he looked like something that you'd find wrapped in rags in the British Museum, with a label telling you it was dug up at Karnak or Memphis, and that it was the body of the treasurer of one of the Pharaohs.

The Count waved the guard out of the room, and the Count himself locked the door through which he had left, and two other doors that led out onto a terrace. And lest there might be peeping servants, he placed table napkins over the keyholes so their cunning eyes couldn't see what was happening in the room.

The Count then stood before the bonze and spoke to him—spoke in a language which we didn't know, but which we found out later was an ancient tongue called Pali. And the old man listened with the lids of his eyes drawn down over the bits of glittering black agate that they covered. For his. eyes had no whites to them at all. They'were black as bog-oak, but with, a shine to them like the flash of a diamond when they moved.

Swiftly the Count talked; then he stepped back, leaving the old man standing on a stretch of carpet some five feet from the end of the big table around which we were sitting. And in the fat silence of the closed room, we stared at him. Aye, we stared at him.

HE did nothing—at least nothing that we could see; yet there was in the room a feeling of great mystery, a feeling that something of which we knew nothing was going on, something that was akin to what John Trench, the blind man, who lived near my father's farm, called "the Ancient Wisdom." Always when John Trench uttered those words, I had a cold feeling in my spine, the words bringing thoughts of happenings that were beyond the knowledge of scholars like Father Houlahan and the Reverend Mr. Alkin, both of whom could talk your head off in Greek and Latin.

For five minutes we stared, our eyeballs getting dry because we didn't dare to wink; then Flane grunted as if he had seen something that surprised him greatly. Flane's glance had turned to the feet of the monk, and the rest of us swung our eyes in the same direction. And a gurgle of wonder came from Thurland and myself. And our heads went forward, and our throats became dry, for the feet of the monk had left the carpet! Left the carpet on which they had been resting! A foot above the pile they were, hanging limply downward, the way you see the feet of flying angels in holy pictures.

There is, I believe, great doubt as to whether this thing that is called levitation can be done. Scientists say that it is impossible; but the scientists, as my Uncle Thurland often remarked, are little stay-at-home fellows who sit in their laboratories with funny-shaped bottles and never see much of the world. And the things they don't see they won't believe, they being like Morry O'Brien, who never believed in telegrams, because he had watched the wires for days, and had never seen any go by.

ABRUPTLY Thurland got to his feet and came close to the monk. He stooped and looked at the space between the feet of the old man and the carpet; then he passed his hand through that space to see if there was any invisible support holding him up. But there was nothing at all. The old one was hanging there in the air like a dragon-fly; and although he didn't weigh much,—the poor devil being only skin and bone,—it looked to us like a fine miracle indeed.

Thurland came back to his seat; and the Count spoke again in the queer tongue. It was a question that he put, as we understood later. He was asking the old man to tell to us the story of the escape from the city of plague on the night when the king and his hundred wives, and the nobles and their wives, with all the treasure, fled across Grand-Lac.

In a whisper it came—a thin whisper that came to the ears like the notes of a flute played far off. And when he paused, as he did often, as if he were refreshing his memory, the Count hurriedly translated to us what he had said....

There were story-tellers who came to the Green Tree Farm who had the gift of words—words that sparkled like opals, and with which they made the weft and the woof of their gay tales, so that their play brought a light to the minds of the listeners and a joy to their hearts. But the story of the monk, as we heard it, was not like those. It was a story as dark as the lake over which went the pirogues full of women and nobles and jewels and gold. Dark and frightening. And in it were bits that the girl Joyeuse had no right to hear, but which she listened to without a blush on her face.

ON and on it went, an inky stream of words, out of which the imagination twisted things just as you'd make baskets out of osiers—twisted things that were frightening: Witchcraft and bedevilment, and tricks of paganism that we didn't understand or wish to understand. Of unholy love and strange vices, till we pictured the hundreds of nobles and the thousand women as a vicious mob sailing in the long black pirogues in the direction of hell.

For to those that escaped, there came the belief that the snake-god had turned against them, and that they were lost, whatever they did; and the despair made them reckless and sinful and vicious, as the pirogues with their forty rowers to each carried them farther and farther from the doomed City of Angkor-Thom.

They swung into a great river that the Count told us was the Mekong, which Thurland already knew of, he being out in China when he fled from the town of Irkutsk. And we saw the river as the story of the monk went on. Coming down from the lost country of Tibet, through wild passes in the mountains, its banks filled with great high trees in which are thousands and thousands of monkeys, sitting so close to each other that their tails hang down like a fringe from the branches on which they squat.

And they screamed and gibbered at the nobles and their women. And the women pelted them with food and fruit which the apes caught. And some of the women, made mad with fear of the death that chased them, threw their heavy bangles at the monkeys, laughing and screaming as they did so. And big birds followed the pirogues to get the food that was tossed from them, Great birds like you see in the big Zoological Gardens: flamingoes, and cormorants, and great crested cranes the height of a man. And the noise and the shouting woke the enormous bats that slept in the thick foliage of the trees, the big bats of Asia that have wings made of reddish-looking leather, no feathers on them at all, and who sleep all day with their heads hanging down, their claws clinging to a branch of a tree.

Now, I wish that I had possessed the power to take down every word that the Count translated to us on that spring day—take it down the way the smart reporters take down the questions and answers in the law-courts. But I hadn't the trick, so the words ran into each other and formed just a splendid purple patch in my memory, and out of that patch I pick the bits that didn't dissolve, so to speak, they being too colorful....

Behind the line of pirogues on the dark silent river crept the Plague—mad with the king and the nobles and the lovely women who were trying to escape from it: Whipping along the oily water faster than the long canoes, snatching now and then like the quick paw of a beggar at a fruit-stall. Snatching one of the dainty little ladies in her finery and flashing jewels. "Hah," said the Plague, "you thought you would escape me, did you!" And saying that, it would strike. And the men at the pirogues would thrust the body overboard to the big fishes who were swimming after the pirogues.

After such a happening the king would shout at the rowers, and the nobles would whip them with long bamboos; but no matter how fast they rowed, the Plague kept up with them. At first those that were in the last pirogue thought they were in the worst position, and their rowers flailed the river till they got up near the front; but soon they found that their place in the line had nothing to do with the wicked snatching hand that followed. For men and women in the first pirogues were picked oft while the occupants of the last were not touched,

FOR days they drove northward up the great dark river. They came to the falls and the rapids, and they carried the great pirogues over them and put them again in the water. And hundreds of miles from Angkor, so it seemed to them, the Plague halted. For only one man took sick in the space of three days, and this was a holy man, a venerable bonze, who had been permitted to come because of his sanctity and great age.

When this man took sick, a noble ordered the rowers to toss him overboard; but they refused on account of his great age and holiness. They thrust water and food to him, and he recovered, the only man who had been stricken by the Plague and escaped death.

Then, according to the monk's story, the holy man uttered a warning to the king and the nobles and women in the pirogues. He told them that they had left the Plague behind them, and if they changed their ways and manners, they would all live. If they didn't :here was, in their midst, an unknown who was a sort of carrier of the malady, who would watch them closely, and if they sinned, the unknown would again unloose the terror from which they fled.

His words terrified them. The drunkenness and sinfulness ceased. The pirogues came to a country where the people were simple and industrious, and there they landed. They carried the treasure ashore; then they sank the boats, so that none of the Khmer folk would know that they were there. They climbed up into the uninhabited passes; and there in a valley, the king ordered a halt. The rowers became bullies of the native tribes, forcing them to construct houses and temples, and they were flogged when they didn't go at their work with a will.

For a space of time that the Count thought between twenty and thirty years they lived there, and frightened by the words of the holy man, they were quiet, thanking the gods for their escape. Then the life seemed dull to them, and the old devils of the flesh got to work. The city that they had built became a cesspool. Vice flourished; they drank, and dethroned the stone gods that they had set up after their escape. Then, on a day in summer, the Plague pounced on them again—the Plague that had chased them up the Mekong! The Black Death!

The Count paused in his translation of the monk's tale. We were all staring at the ancient. Thurland was on his feet. The monk was taken with a sort of convulsion. He whined softly, then with a queer jerk of his features he fell upon the carpet, as if some unseen force had struck him and laid him flat.

As he lay there, he repeated again and again one word. Screamed it. It sounded like karsh, but it had no meaning to anyone but the Count and his niece.

"What is he saying?" asked Thurland.

The Count took a glass of water and sprinkled the face of the monk, then he turned and answered the question put by my uncle. "He is accusing himself of being the carrier," he said quietly. "That it was in his body the germs waited, and that he destroyed the City of Klang-Nan."

"But this," cried Thurland fiercely, "this was hundreds of years ago!"

"I know," said the Count. "That's the great puzzle. Wait till we get rid of him, and I'll tell you something."

HE touched the bell; the man who had brought the monk into the room appeared: and the Count instructed him to take the ancient away. The servant lifted the sobbing old thing in his arms and carried him away, but his presence seemed to remain. In a queer way he was there—the feel of him, so to speak; and we stared at the spot where he had hung like a scarecrow in the sunshine, the thin stream of words coming from his shriveled lips.

I shivered as I thought of the accusation he had made against himself. He was the Plague! The carrier! And although as Thurland said, hundreds of years had passed since the destruction of Angkor, I was cold with the fear that came over me.

The Count began to talk, and we listened. "This man was brought to Paris by the French Government, with many others, at the time of the Colonial Exposition. He was one of the exhibits from the Laos State in the north of Indo-China. There was a belief then that he was the oldest man in the world. The medical faculty thought he was a hundred and forty years of age, perhaps more.

"Few took much notice of him at the Exposition. He was just an old, old man. He lived in the huts with his countrymen, and sat in the sunshine like an old lizard when Paris passed by in her thousands, and laughed at him. I saw him then. Youngsters tossed bits of paper at him to wake him up, and he cursed them. Funny, yes? Children annoying him when—when he thinks that he is some one who possessed the power to wipe out a city? Startles you, eh? Man in the Bible, remember? Elijah the Tishbite. Kids taunted him, and the old she-bears came down and mauled them."

FLANE said: "Do you really think that he has the power? I mean, do you think that he is still a carrier?"

"He might be," answered the Count. "I don't know. Wait! I'll tell you everything that I know about him. For some reason or other, he didn't go back with the other human exhibits who were brought from the far-off colonies to show the stay-at-home French what a great empire they possessed. It's always the way with those affairs. Governments are in a hurry to bring the exhibits, but in no hurry to take them back. This old freak broke loose from his mob and wandered about Paris. Didn't want much. He eats a handful of rice a day. Slept in doorways. Now and then, I believe, the agents picked him up, but they let him loose when they could get nothing out of him.

"Five weeks ago I was walking along the Boulevard Malesherbes. I saw a crowd and went over. A truck had hit this poor devil. He was lying in the roadway, the people waiting for a policeman to arrive. I don't blame them for not wanting to touch him. He didn't look nice. And—and there was that feeling of frightful age about him. Gave them the jumps.

"I got him to a pharmacy. Had his head bound up and brought him here. Why? Well, I am interested in things that this silly world, in its hurry to play with bubbles, has forgotten.

"I am interested in folklore. In witchcraft, demonology, magic. Have you read The Golden Bough?... No?" It doesn't matter. But this business—this that we have in hand—it appeals to me. Greatest thing in my life. I've been listening, watching, questioning this old man day after day. He knows about more than half the scientists in Europe. He has secrets that would astound them."

Thurland stretched his long legs and stared at the small man on the other side of the table. "And now," said Thurland, "what do you propose to do?"

There was a long interval of silence, the bright eyes of the Count fixed upon the face of my uncle. The strange fighting face of Thurland Spillane, the face that resembled so much the picture I had once seen of that splendid doge of Venice whose name was Andrea Dandolo.

And we waited as if something great hung upon the answer to that question, something that was a little terrifying. Flane and I, and the girl Joyeuse, waited.

The Count spoke softly. "Some one," he said, "has written these words; and though they are sweeter in the French, still, they are thrilling in the English: 'In the depths of the forests of Siam, I have seen the evening star rise above the ruins of mysterious Angkor.'

"I know the East. I have lived at Hanoi, at Hue, at Haiphong; but I have never visited Angkor. Now, I have a reason. I am, curiously, a person who dislikes death. I hate the tomb. There are no more damnable words than those that are written about the life of man being but three score and ten years. Those words have killed thousands! Millions! When a man lives to be ninety, the foolish papers say that he has attained a great age. Reporters come on his birthdays, and ask him silly questions. Ninety! What is ninety? It is nothing! Do you know— Wait! Look at the spot where that monk stood! Look at it! You can easily think that he is still there! Still there in the sunshine! Why? Because of some strange personality that the years have bestowed on him—that the centuries have bestowed on him! Do you know that I firmly believe that he—that he in his own body and flesh—was the carrier that brought the Plague to the city in the lost valleys of the Lacs country, the City of Klang-Nan!"

MY two uncles sat silent. The girl rose and opened the windows leading to the terrace. The whisper of Paris came to our ears.

"And you want to go out there?" said Thurland, after a long silence.

The Count nodded. His hands were hugging each other, so that the knuckles were as white as his face. And his eyes were brighter than ever.

"To hunt for what?" asked my uncle. "You're rich. It isn't treasure you're after?"

"No," answered the Count. "I wish proof. I wish to take this man, this monk, over the route that the fugitives from Angkor-Thom took in the long ago, I wish to make a check on what he has told me. I want to see if it is possible—" He paused, and my uncle Thurland finished the sentence.

"If it is possible to beat death," said my uncle.

Again the Count nodded. Thurland smiled the strange cynical smile that months later we saw on many a stone face carved in long-dead centuries—the cynical smile that tells of shattered beliefs, of the futility of knowledge, of the brave facing of facts that have rolled in upon the mind to prove the smallness of man and the little effect his passing has in this big throbbing world. The terrible grinding world that reduces all things to gray dust....

The atmosphere was cleared by the statement the Count started and which Thurland finished. It put the Count's cards on the table. He was willing to take a gamble. He wanted neither gold nor treasure; but he wished to find out if it was possible to beat death. Bright boys have tried it through the centuries, men who got mad when they heard that a tree like the big sequoia in California could live for three thousand years or more, that the carp at Versailles were a hundred and fifty, and that tortoises in the Galapagos showed by their shells that they were veterans when Bonaparte was prancing around Europe.

"And the treasure?" asked Thurland; and his voice had a soft purr in it.

"If there is treasure there," said the Count, "it can be taken by anyone who accompanies me. As to the expense, I might say that I am willing to pay everything. I am rich. I have nothing else to occupy my mind—and I too would see the evening star above Angkor."

Thurland smiled, and looked at Flane. They didn't speak, because speech was unnecessary. The story, as translated by the Count, had put its hands upon them.

"You have maps?" said Thurland, turning to the Count.

"Scores of them," he answered. "Let's go into the salon. The maps are there."

In a body we moved into the adjoining room; and upon a huge table were spread maps of Indo-China, of the Great Mekong, of the unexplored regions running up toward Tibet where live the Cambodians, the Tais, the Khams.and the Kraus, about which the busy Occidental world knows nothing at all.

It wasn't that day, or the day before, that the Count had thought about voyaging to the East. The look of the room showed that. And with the maps were pictures of Angkor-Vat—photographs of the enormous terrace, the stairways, the galleries and the towers, hemmed in by the jungle that now surrounds the city, leaving only the great monuments to show the luxury and pomp that was there in the long-dead centuries.

THURLAND and Flane fell upon the maps: the girl Joyeuse led me aside and questioned me about my two uncles.

I told her of the quest in the Sahara, of the Black Mouth, and how we escaped—the story told the world in the novel "Caravan Treasure." And she was much interested. Suddenly she leaned forward, and spoke determinedly.

"My uncle wishes to leave me with friends at Passy while he is away," she said; "but I won't go to his friends. If he goes to the East, I'm going too!"

She explained her name to me. Charlemagne called his great sword Joyeuse; and, blending in the steel, so she said, was the lance-point that pierced the side of Our Lord. Her words thrilled me.

"It's strange to be named after a sword," I said.

"In French the word sword is feminine," she answered. She had a queer way with her.

The afternoon closed in. The lights of Paris showed up like a great field of daisies. My two uncles and the Count crouched over the maps and the photographs. They talked in whispers.

It was quite dark outside when the man who had charge of the old monk knocked at the door and stumbled into the room before the Count had time to tell him to enter.

"II s'est échappé!" he screamed. "Le bonze, monsieur! Le bonze!"

Words choked him as he tried to explain. He had left the old one for a few minutes to get some food for himself, and when he returned, he found the window of the room open and the monk nowhere to be seen.

THE Count led the rush that followed —through the dining-room, along a corridor leading to the rear of the house, across an open court to a sort of annex in which the servants slept. The stuttering guard pointed to the open window through which the old one had escaped.

"He'll be in the garden!" cried the Count. "He couldn't climb the wall. Call the other servants, and search the garden!"

That garden of the Villa Mille Fleurs had been left to itself. It had run wild, the shrubs and trees not knowing the shears or the saw for a long time. Now it seemed dark and mysterious as we plunged into it to search for the ancient.

Flane, who was beating the bushes to the right of Thurland, stopped suddenly.

"What's that?" he demanded hoarsely.

There came from the far end of the dark garden a thin wailing noise that was like the sound of a flute played softly—thrilling and rather frightening music. It came up over the dark shrubbery and sobbed around us, bringing chills to our spines as we listened. And it seemed to be colored, colored a queer scarlet, so that we looked up as if we could see the notes swirling around our heads.

"What kind of devil's music is that?" asked Flane. "Who's playing it?"

The Count, who had stopped like the rest of us, cried out something in French and rushed forward. Thurland and Flane followed him, and I ran in their tracks, afraid to be left alone. Crashing through the bushes, they charged toward the end of the garden, and the scarlet notes whipped them forward.

There was a high wall of stone at the rear of the garden, an old wall upon which green ivy crawled. The Count swung to the right and followed it, my two uncles at his heels. The music was louder now—faster, more troubling to the nerves. It carried a barbaric note. From somewhere in my mind came a line of verse that I had read years before:

"The mad musician whose hot breath

From reed pipes brings the Dance of Death!"

The Dance of Death! That was it! The swirling notes that filled the garden was the music of death! I wanted to cry out the information to Thurland, but the ash of great fear filled my throat.

The Count halted; Thurland pushed past him. Against the ivy-covered wall I saw something—something black that, either by its own force, or by the pull of some one on the other side, was moving up the wall. Not climbing! Moving —rising without movement of its own!

It was the monk! Thurland, with a Gaelic curse on his lips, sprang forward and grabbed him. The music stopped with a shrill piercing note. Flane, running to the side of his brother, beat at something that seemed to come from the other side of the wall; then the servants came up with two lanterns.

Thurland held the old man by the sleeve of his yellow robe. The ancient was weeping. That is, the tears on his withered cheeks showed as the lamp was turned on him, but he made no sound.

"Back to the house," said the Count, and back we went—silently, Thurland still clinging to the sleeve of the monk.

INTO the salon Thurland took the ancient. The Count ordered the servants back to their quarters, and the five of us stood around the strange figure. The girl Joyeuse had not joined in the rush across the garden, but she had been waiting near the annex when we returned. She didn't seem frightened.

"Now," said Thurland, looking hard at the Count, "you haven't told us everything. There were others out there tonight.... The music—the hand that Flane struck at.... Does anyone want him?"

"Yes," answered the Count. "I can't tell you who they are, but I have known for some days that others are trying to coax him away. It was for that reason that I have put a guard over him."

"And you think they know what you know?"

"I suppose they do. It would be the only reason for getting him into their hands."

"This is a strange business," Thurland muttered. "A strange business entirely."

The Count opened his mouth to speak, but a knock at the door halted him. When he said "Entrez," the man who had been guarding the ancient came in.

Head bowed, the fellow commenced to speak in an apologetic tone. His nerves had been upset by the events of the evening; his heart was not as good as it might be. Now, this very night, he would like to make his démission.

"But we cannot get anyone to take your place at this hour," said the Count.

The fellow was stubborn. He had to leave, to leave at once.

SLOWLY the ancient turned and looked at the guard. The glittering eyes were concentrated on the fellow. The right hand, thin, clawlike, was suddenly lifted up, palm turned toward the man; then the fingers closed with a quick snapping motion as if they had seized upon something that was invisible to us. The guard winced, and took a step backward. He seemed terrified.

Thurland spoke. "I'd let him go," he said, addressing the Count. "I've got a thought about him. I think he's double-crossed Methuselah here, and now he's afraid of the old man. Did you notice that movement of the fingers?"

"But who'll guard the monk?" asked the Count.

Thurland looked at Flane. "My brother and I might take turn and turn about," he said quietly.

"There's a room next to the dining-room, a sort of pantry with barred windows," said the Count. "We might shift him into that. It would be easier."

He stepped to a desk, took a wad of hundred-franc bills from it, counted off the sum owing to the guard, and waved him to the door. The fellow stumbled out of the room.

The girl broke the silence following the departure of the guard. "Who made the wonderful music?" she asked. "I have never heard anything so beautiful." Flane looked at her in surprise. The swirling notes had not seemed wonderful to Flane. Not at all.

"It was so—so exotic," continued the girl. "A tune that you might hear on a hillside near Ispahan. Something that—that a shepherd might have played. It thrilled me."

No one spoke. "Who made it?" she asked again, looking from one to another.

"We don't know," said the Count. "We think it was played by some one who was outside the wall. Some one who wished to direct the bonze to the point where he would be helped over the wall. Or—or where he would lift himself over the wall." He turned to Flane. "What did you hit at?" he asked.

"I couldn't say exactly," said Flane. "I thought it a hand, but it wasn't. I'm puzzled."

The Count opened the door leading into the dining-room. We filed through, Thurland still keeping a clutch on the sleeve of the ancient. Joyeuse ran ahead and opened the door to the pantry. It was a long, narrow room with shelves running up to the ceiling. It had two windows opening onto the garden, both closely barred. The thinnest man in the world couldn't escape from it.

Thurland examined the room closely. "It's fine," he said. "If he wants to get away, he'll have to come through the dining-room, and it's easy to sit in a room where there's food and drink. Is there a bed handy for the poor devil?"

The Count rang for a servant who brought a mattress and bed-clothing. The bed was arranged, on the floor, the old man pushed into the room. Thurland locked the door and put the key in his pocket. And Flane got a length of rope from the kitchen, ran it through the brass handle of the door, and tied it to the leg of the big table at which they sat.

"That's that," he said, rubbing his forehead. "If there is any whisky about, I know where it would be useful."

BUT the monk's story, translated by the Count, followed by the strange business in the garden, had left me jumpy. I turned from time to time and stared at the door leading into the pantry. The Count believed that the old man in the narrow room with its barred windows had wiped out the City of Klang-Nan in the secret valleys of the Laos hills. He had definitely said so, and I believed it—believed with all my heart and soul.

The very look of the old man stirred the imagination so that an enormous faith was bred in the mind, and all things were believable....

I fell asleep at last, and I didn't wake till the sun was shining through the lace curtains of the dining-room. Thurland was awake, but Flane and the Count were asleep, their heads pillowed on their folded arms. I glanced quickly at the rope that was tied to the leg of the table; Thurland saw my interest and grinned.

"He's still inside, Jimmy," he said.

"Are you—are you sure?" I asked.

My words brought a doubt to Thurland's mind. He got up and peeped through the keyhole, and a sigh of relief came from him as he made his observations.

"He's at his prayers," he said, as he came back to the table.

"Who is?" asked Flane, roused by his brother's words.

"Monsieur Methuselah," answered Thurland. "You had a fine sleep. I should have called you two hours ago to take your turn in watching the old one, but I let you sleep."

"I wish you had called me," said Flane. "All the damn' talk of the evening gave me mad dreams."

NOW as I looked at Thurland, I knew that he had cut his walking-stick, as they say in Kerry. The smile on his face told me that he had accepted the offer of the Count. A strange joy had descended upon him, for the. Angel of Great Happenings had opened a path for him out of the morass of dull days. He was like a hunting leopard that had found the door of his cage open, and though stricken with amazement, was scampering madly toward the jungle.

The Count awoke, looked at Thurland and Flane, turned his head and glanced at the rope, then grinned good-naturedly.

"What time is it?" he asked.

"Nearly seven," answered Thurland.

"We'll get some coffee," said the Count, and he walked across the room and pushed the bell-button.

As he did so there came, as if his finger had magically produced it, a clanging of the bell at the front entrance of the garden—the insolent clanging that goes on and on, and which, if one is imaginative, one always associates with the Law. For decent people never jangle a bell. They pull the cord softly and wait. But the Law, wishing to send fear in front of its arrival, treats the bell-rope or knocker with fine violence.

The Count looked out through the window; a servant was hurrying down the garden path. Through the quiet air we heard the bar of the big iron gates pulled back, then the sharp voice of a man addressing the servant. Quite clear it came to us, and it rode on the wings of fear.

"Count Zavrel?" said the voice. Then came a word that the Irish hate, the word "Police." And good reason they have for their dislike to that same word.

THURLAND got to his feet and walked to the window. Flane followed. The four of us, looking down on the driveway, saw the little procession. The servant walking ahead, followed by two men, one in the uniform of an inspector and the other the ordinary small agent that you see in scores on the streets of Paris.

"Now what the devil?" said Thurland softly. "On a nice spring morning like this, it's strange that the first callers are two ferret-faced wretches that have nothing to do but stick their noses into other people's business."

In silence we waited, hearing from far off the voice of the servant, which was quite respectful and a trifle servile. For servants, as Thurland once said, love to see their masters in trouble; and to them, a visit from the police always spells trouble, as it often does to people higher up. The fellow was asking them to seat themselves in the hall while he went to see if the Count was up.

Not thinking we were in the dining-room, he opened the door, and there was a grin of pleasure on his weak face because he was still thinking what a joke it would be to tell his master the police were after him. He wiped the grin away with an effort, and bowed to the Count, informing him that an inspector of police wished to speak to him.

Another thing my uncle said once was this: "Police and undertakers enter a room in the same fashion. They have queasy looks on their faces, as much as to say: 'Where's the body?'"

The inspector picked out the Count, bowed, and took a notebook from his pocket.

"Last night, just before eleven o'clock," he said, speaking in a high-pitched voice, "a man was sitting on the terrace of the Café du Printemps in the Rue des Acacias. Suddenly he fell from his chair to the ground. An ambulance was called, and he was taken to the Hospital Beaujon. The doctors examined him, and reported that he was dead." He paused and looked at the Count, then continued: "In his pocket was a letter evidently addressed to himself in the care of 'Count Zavrel, Villa Mille Fleurs, Boulevard d'Argenson, Neuilly.' His name was Pierre Lartigue."

"I have employed a man of that name," said the Count coldly. "He left my service last evening. Why does his death concern me?"

"It is the cause of his death that troubles the hospital," said the inspector slowly.

"Why?"

"Because the medical authorities have an idea that he died from a strange Asiatic disease. They suspect the plague."

The face of the Count gave no hint of the shock that he must have felt. He was quite calm, and in the silence that followed the statement, the inspector looked at my two uncles, who had now taken seats at the table. They appeared as unconcerned as the Count, though they too must have been startled. As for myself, I thought my pounding heart would fracture my ribs.

"Plague?" murmured the Count. "The plague in Paris! What kind of plague?"

"Bubonic," snapped the inspector.

AGAIN the little silence; again the inspector looked from one to the other. The mouths of my two uncles were closed firmly. It was not their business; it was a matter for the master of the house.

"I know nothing about it," said the Cbunt. "I cannot understand how he got it. Where, may I ask, do I come into this matter?"

"There is," said the inspector slowly, "the possibility of quarantine. That is, if the disease can be traced here."

"But he may have visited scores of places," protested the count. "There is no evidence that he contracted it here."

"Not yet," said the inspector. "What were his duties?"

"General," said the Count casuallv. "He did this and that."

The inspector was silent. He seemed puzzled. He consulted his notebook, found no help there, looked at the agent at his side, and then let his gaze wander around the dining-room.

His eyes fell upon the rope that ran from the handle of the pantry door to the leg of the table. It made him curious. He stared at it for a few moments; then with raised eyebrows turned to the Count.

Thurland spoke before the Count could answer the yet-unspoken question. "If you're troubled as to what we have in there," said my uncle, "I'll tell you. We have there two of the wildest and most savage wolf-hounds that were ever bred in Ireland. They hate police like the devil; so when we saw you and your friend coming up the garden path, we slung them in there for safety."

Flane grinned openly as the faces of the inspector and the agent showed the effects of the information. They moved back toward the door through which they had entered, and the look of confidence fled from their faces. For a moment they forgot the plague, and the man Pierre Lartigue whose sudden death had brought them to the villa.

"Have you a license?" stuttered the inspector.

"It's with them," answered Thurland gayly. "Tied around their blessed necks, so to speak. Would you like to see it?" He half rose from his chair and turned toward the pantry door, but the inspector stopped him.

"No, no," he cried. "It is not in discussion at the moment. The matter—the matter on which I came has nothing to do with—with dogs."

He seemed a little rattled, and the Count stepped in to finish the interview. "Is there anything else?" he asked. "If you have quite finished we would like to proceed with our breakfast."

The inspector tried to recover his composure, but failed, then stuttered out a half-threat. "I haven't orders to quarantine the villa," he said. "I must see the hospital authorities, and when—"

"When you do see them, come and speak to me," said the Count irritably. "Good morning."

The two stumbled through the door, the agent pulling it to behind him. We heard them clumping along the passage, listened to the servile domestic who escorted them down the driveway, then when the iron gates clanged behind them, the Count sprang into action.

"Get him out!" he cried. "Quick!"

HASTILY Thurland untied the rope, and opened the door of the pantry. The monk was lying on the mattress, but Thurland stooped, picked him up bodily and carried him into the dining-room.

In that same strange tongue that they had used on the previous evening, the Count fired rapid questions at the ancient and with the same quickness the monk replied. We guessed the reason for most of the queries and answers. The Count wished information. He had accused the old one of inoculating the unfortunate guard, and now he wished to find out if the malady would spread.

The Count turned to Thurland and Flane. "He says that there is no danger," he cried. "No danger of it spreading. He doesn't deny that he—that he gave it to Lartigue."

"Mother o' God!" muttered Flane. "This is a fine mess we're in now!"

"It's no mess if there's no danger of it spreading," snapped Thurland. "If the malady stops with the death of the fool guard, who brought it on himself by double-crossing the old man, how the devil are we concerned?"

I KNEW then that the amazing story of Angkor had entrapped Thurland. There was a fierce fighting light in his eyes as he hurled the question at Flane. Upon him was the same wild desire to seek and find that had gripped him during the mad trek across the desert in the quest of the Caravan Treasure.

The madness flamed up in him, smashing down obstacles, making little of all the barriers that fate might put in the way. For when Thurland sought anything that he wanted greatly, there was only one obstacle that could stop him. That obstacle was death. "But the quarantine?" cried Flane. "To hell with the quarantine!" snarled Thurland. "Why wait here till the fools put a guard on the place?" He turned to the Count who had stood by during the interchange between the two brothers.

"You said that you had everything prepared for this voyage?" he demanded.

"Everything," answered the Count.

"The matter of the money?" asked Thurland.

"Already transferred under another name to the Banque de l'lndo-Chine, and the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation. There's enough in hand to get us to Saigon."

"Passports?"

"Mine and my niece's are in order."

Thurland turned to his brother. "Go to our hotel as quick as you can. Get the passports! Hurry, now. There isn't a moment to lose. That little inspector would have camped here if I hadn't frightened him off with the talk of wolfhounds. But he'll be back. Get to it!"

Joyeuse came into the room as Flane dashed away. She looked from the Count to Thurland, then spoke softly. "What's happening?" she asked.

"We're going away," said Thurland.

"When?" she asked.

Thurland looked at his watch. "It's now ten minutes past eight," he said. "I think we'll be hitting the high road in the direction of Marseilles a few minutes after nine."

My uncle was in charge now. The mantle of authority was upon his shoulders. He pulled a chair to the table and motioned the count to sit down beside him. A valley in the far-off hills of the Laos states called to Thurland Spillane.

The servants were called in, one after another, handed a month's wages and dismissed. The chauffeur was ordered to get the two cars—one American and the other French—ready for a journey. When he reported that they were in order, he received an extra pourboire and was told to pack.

"Everyone must be out of the place within thirty minutes!" cried Thurland. "It's to your own benefit to snap into it. Listen! The police have a nice thought of quarantining the outfit, because the man Lartigue died last evening from drinking French beer, so I'd advise you to hustle."

NO need to repeat the order.... The villa was like an ant's nest on which some one had poured a pot of boiling water. The poor devils of servants, horrified at being locked up for weeks in a place that the authorities viewed with suspicion, rushed to their quarters, tossed their belongings into battered trunks and old valises, and dragged them out through the porte de service; There, in the back street, they piled them on barrows and taxicabs and fled, thankful to escape with a month's wages that they hadn't earned.

The telephone rang, but no one went near it. "It's the little folk at the hospital," said Thurland. "They want to tell us that they've found a bug with a Latin name, and for us to come in and get vaccinated. Pull the yellow nightshirt off that old man, Jimmy. He'll have to get into regular clothes."

The Count brought an old suit and an overcoat, and with much trouble we got the bonze into them.

Joyeuse brought a packed bag into the dining-room. She seemed delighted at the sudden departure. The Count opened a strong-box in the wall of his study and took from it a fine wad of thousand-franc bills. He stripped off a number and passed them to Thurland. A butler, the last servant in the villa, reported that windows and doors were locked, with the exception of the big iron gates of the driveway.

Flane arrived in a taxi; then Thurland gave the orders for departure. It was exactly forty minutes since the inspector had left the villa.

"The Count is driving the French car," said Thurland; "and you, Flane, and the old monk will ride with him. I'm taking Jimmy and the young lady with me in the American machine. We're heading for Marseilles by way of Nevers, Lyon and Avignon. There might be trouble, and there mightn't. If we get separated, we've got a meeting-place arranged. Now let's go!"

Thurland led the way. We swung through the big gates onto the Boulevard d'Argenson, crossed the Pont de Neuilly and turned southward.... The morning was a sister to that of the day before. The green woods of the Bois de Boulogne waved to us. Little winds from the Midi came up and met us as we found Route Nationale Number 7, running in the direction of Moulins.

Joyeuse was delighted. The visit of the inspector had made it unnecessary for her to plead with the Count. She kissed her fingertips to Paris—Paris of the turned heels, who had found reason to send my Uncle Thurland wandering.

THERE are no other roads like the roads of France. For they, above all others, whisper of the days of splendid romance. In the yellow sunshine of the spring you can look at them with half-closed eyes and see in fancy the dashing ladies and handsome men who once rode over them. For a road gets character from the people who pass over it, gathering grace or deviltry from the shoes of their feet or the hoofs of their horses. And this is well known to wise men, for the roads that have been frequented by footpads and robbers inspire fear, although you might not know their history; while the paths leading to shrines and sacred places have acquired a soothing quality that is like balm to the soul of those that walk over them.

By Fontainebleau, that seems a green heart of romance itself—for to Fontainebleau come folk from all over the world, their own lives being so dull that they try to satisfy their longings by staring at the bedroom in which poor Marie Antoinette slept. "And that," said Thurland, "is a poor way of getting a kick. It's like sniffing the empty glass of a man who has been drinking whisky."

By Nevers and Moulins, clinging to Number 7 and taking no notice of the small roads that ran out from it into romantic country. Somewhere behind us were the Count, Flane and the bonze; and wondering a little as to how they were getting along, we thundered into Lyons, which is a big pounding town, and there we found lodgings in the Rue Quatre-Chapeaux, which is a funny name for a street. But the name of the hotel was funnier, it being the Hôtel Milan, Monopole et de la Paix; and Joyeuse and I puzzled a lot as to the relation of the names to each other. The ride had made us friends—the ride and the fact that we were on our way to see the evening star shine upon Angkor.

THE Midi was before us on the morning we left Lyons—the Midi, where thin sunshine makes cabins into castles. The Midi, where the little hills become the Alps that Tartarin climbed, where Saint Marthe slew the monster Tarasque that ravaged the countryside, and where Queen Jeanne of the perfumed hands, the last of the Chatelaines, presented the prizes to the tilting knights at the Courts of Love.

"This country," said Thurland, nodding at the stretches of staked vines, "was once a fine place, where it was as easy to get into a fight as it is in Ireland; but now they do nothing but squeeze grapes whose juice they send to America. The world has gone to the devil. There are big wars; of course, but it's the little fights that you get day by day that keep men healthy and sane."

We kept a bright lookout for the other car, but we saw nothing of it. Thurland was worried lest they had struck trouble, for if we lost the monk, it would be no use going on....

Then, in the late evening, as we swung towards Aix-en-Provence, we saw ahead of us the big car that the Count was driving. Halted by the roadside, a mounted gendarme was studying the carnets of the driver in a manner that showed he didn't like them.

"Agh!" growled Thurland. "The Curse of Cromwell on all police, say I!" And saying that he stepped on the gas and sent a warning for the gendarme to pull his horse out of the way.

The gendarme was annoyed. He made a motion with his hand for Thurland to stop, but my uncle pretended that he didn't see him. He drove straight on without a glance at the Count or Flane, and he took no notice of the blast of the whistle that the gendarme sent after us.

"Did you see the old monk in the car?" asked Thurland, when we were a kilometer away.

"No," I answered. "I only saw the Count and Flane."

"They've stuffed him under the seat," said Thurland. "Flane is better than a jackdaw for hiding things."

My uncle remained silent for a few minutes, then he expressed the fear that had come to him. "If they took that old Methuselah away from us, I'd go back and burn the town they carried him to," he said grimly. "Interfering devils are the police! Always sticking their cocked noses into other people's business. There was once a great scientist in Ireland who invented a disease that would only take on policemen. He died before he could get it in proper working order. I have always regretted his death.

Lest the gendarme would get to a telephone and block us, we circled Aix, then ran southward to Aubagne, coming into Marseilles from the east, as if we were returning from the Riviera. We stopped at a little hotel just off the Cannebičre.

HIGH above Marseilles is the church of Nôtre-Dame-de-la-Garde, and it was on the hill where the church stands that Thurland had arranged a meeting with the Count. A strange place for a rendezvous, but a wise one, for it is only tourists who go up to the church, and the police think that all tourists are harmless folk who poke around old churches and do no harm at all.

The three of us took our coffee and brioche on the Cannebiere, the next morning, and Thurland talked.

"Down this street," he said, "went a lot of fine scoundrels on their way to the Holy Land to beat up the Turk. A fine business, the Crusades. If they got killed, they went straight to heaven; and if they lived they had all the plunder that they could grab and a lot of honor.

Off to Jerusalem to tread ankle-deep in blood at the 'winepress of the Lord.'"

A lean, rat-faced boy came running from the Cours Belsunce. He took a quick look at my uncle, then came forward and spoke in a whisper.

"Comment?" cried Thurland.

"II y a des agents au garage qui vous cherchent, monsieur!" cried the boy.

My uncle reached for his pocketbook, took out a hundred-franc bill and put it into the hands of the boy. "You'll go far," he said. "There are boys like you in Ireland with the hatred of peelers in their blood." He turned to us with a grin. "The police are at the garage waiting to chat with us," he said. "We can't go back. We'll look up the rest of them. I'm afraid the place is not healthy."

Thurland bought a copy of Le Petit Marseillais as we climbed into the cab that was to take us to the ascenseur that runs up the face of the hill to the church. Hurriedly he searched the pages of the paper, and a grunt told Joyeuse and myself that he had found what he hunted for. He placed a big forefinger on the paragraph, and we read it as the cab jolted over the rough paving-stones of the Boulevard Nôtre Dame. It was a Paris telegram from the Havas Agency, an agency that collects news for the out-of-town papers, and it ran:

Un invidu, Pierre Lartigue, admis ŕ L'Hôpital Beaujon, est mort aussitôt arrivé. Les médecins, ayant trouvé sur lui les symptômes de la peste, ont immédiatement averti les autorités. La police est alertée.

"Well," said Thurland, "the day is starting badly, as old Paddy Meehan said when they woke him up to tell him they were going to hang him. P'raps Flane and the Count and the old blackamoor are in a prison in the Midi, and our trip :o the East is a pipe-dream."

The ascenseur took us up the face of the cliff, and there on the top we found Flane waiting for us. He grinned as we arrived for Flane, like Thurland, took troubles with a light heart.

"You passed us in a hurry yesterday!"

"I knew you'd get out of trouble withuut my help," laughed Thurland. "But we've had our share this morning. The police are after us. Where's the Count?"

"He's out at the Jardin Zoologique," answered Flane. "He's got the monk with him." *

"And why?" cried Thurland.

"It seems," explained Flane, "that there's a leopard in the garden that came from the monk's country. He saw it when he passed through on his way to Paris, and he spoke to it. That's what he says this morning. He'd do nothing at all till he was taken to visit the beast."

My Uncle Thurland swore softly. "This is a fool business at a moment when the police are on our heels," he cried. "Here in the paper is a bit about the death of the fellow in Paris; the police are at our hotel waiting for us to come back; and now you tell me that the count and the old monk are making a morning call on a leopard in the zoo!"