RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

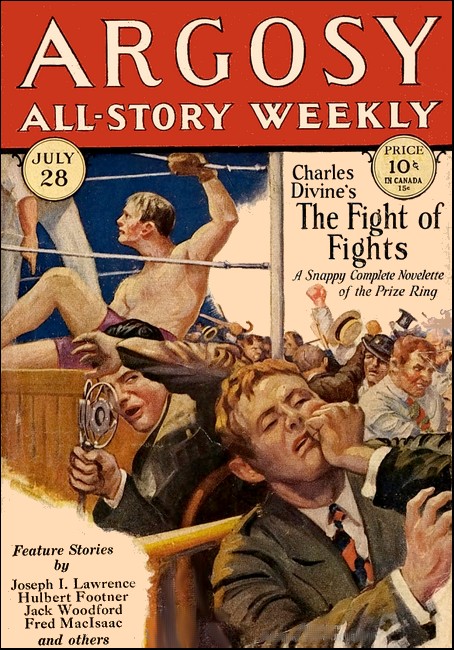

Argosy-All Story Weekly, 28 July 1928,

with "The Perfect Blackguard"

Madame Storey seeks to solve a murder mystery

by working along lines that the police had eglected.

FROM the newspapers Mme. Storey and I had familiarized ourselves with the details of the case before we had any expectation of being drawn into It.

They played it up for all it was worth on account of the quaint and forgotten corner of New York it illustrated, and because of its strong elements of human interest: the wedding so tragically interrupted; the young girl so pretty and gentle who had yielded to an uncontrollable desire to obtain the means to buy pretty clothes to be married in; the honest lad dum-founded by what had happened, yet loyally determined to stand by his girl; it all made a most poignant appeal to the feelings.

This was the story:

SOLOMON HENNIGER kept an old-fashioned pawnshop on Mutual

Avenue, a street tucked into the far northeast corner of

Manhattan Island, that nobody ever heard of until it broke

into the newspapers. The photographs of the tragedy depicted a

faded sign with the well-known three balls and a pair of show

windows crowded with the curious articles that one associates

with pawnshop windows.

Inside, the grubby interior was so packed with bulky pledges of all sorts it was impossible to move around. There were even goods hanging from the ceiling.

There were no little booths for privacy, such as the more modern places affect; nothing but an open counter down one side, having a brass cage at the end for money transactions.

On a morning in April a Mrs. Susie Brick, of 627 East Ninety-Seventh Street, was on her way to Henniger's to pawn a pair of chenille portières. She explained to the police that she was a little short of making up her rent.

As she turned in to the pawnshop she came face to face with a young woman coming out. A pretty girl, and rather better dressed than one might have expected to find in that humble neighborhood.

"Looked like a down town miss," said Mrs. Brick.

The girl was visibly agitated, and when she saw Mrs. Brick, suddenly put her hand inside the door and released the spring that held the night-latch. Consequently when the door shut it could not be opened again.

Mrs. Brick, with natural indignation, demanded to know what she had done that for. The girl said something in a mumbling voice, and sped away.

Mrs. Brick understood her to say that Mr. Henniger was sick. She hung about for a moment, at a loss what to do.

She knocked repeatedly and peered through the glass of the door, but could make out nothing in the dark interior.

Presently another woman who wished to do business with the pawnbroker, Mrs. Gertrude Colfax, of 131 Mutual Avenue, came up, and the two talked it over. They decided that something was wrong, and went in search of a policeman.

They found Officer James Crehan on post at One Hundred and Second Street and Mutual Avenue. Crehan was well acquainted with old Henniger, and knew that he lived in a flat only two doors from his shop.

He went there, and Mrs. Henniger told him her husband had been in his usual health when he left home, and was certainly in his shop. Mrs. Henniger, a spare little woman of German descent, very active notwithstanding her sixty-seven years, had another key, and accompanied the officer to the shop. By this time a small-sized crowd had gathered in front.

At first glance the store appeared to be empty. Then Crehan saw what he took to be another bundle of old clothes flung down on the floor of the cage.

It was the body of the little German pawnbroker. His bald pate faintly reflected the shine of the electric bulb which had been turned on. A dark stain was spreading beneath it. His body was still warm.

He had been shot in the back of the head, and death must have been instantaneous. From the huddled position of the body it was apparent that the fatal shot must have been fired as he knelt to open the safe.

The safe door was open, and whatever money it had contained was gone. Nothing else in the cluttered place appeared to have been disturbed.

Sympathetic neighbors helped the stricken old woman home. The couple was highly respected in that quarter, where they had lived for forty years. They had no children or other near relatives.

Meanwhile Crehan kept everybody out of the shop, and telephoned for assistance. A search of the premises revealed the weapon from which the fatal shot had been fired.

It was found lying among the piled goods, where it had evidently been flung at random. It was a brand new .32 automatic, from which one shot had been discharged.

By means of the manufacturer's number on the gun, its sale was traced within an hour to one Charles Vernay, of 193 East Twenty-Fourth Street. Young Vernay was found at the works of the Amsterdam Stamping Company, where he is employed as a shipping clerk.

He was a stalwart, good-looking chap, with a peculiarly open and honest expression, a general favorite in his shop. His employers gave him an excellent character.

It appeared that he had just been promoted to the job of shipping clerk from that of helper, and that he was shortly to be married. An alibi was instantly established for him, inasmuch as he had been at work upon the shipping platform since eight o'clock in the morning.

Vernay was much troubled by the questions of the police. He claimed that he had bought the pistol as a gift for a friend.

He was reluctant to give his friend's name, but finally stated that it was Miss Jacqueline Pendar, his fiancée. Miss Pendar, he explained, rented an unfurnished room in a building to which there was access at all hours, and he considered that she required the gun for her protection.

He supposed that it had been stolen from her, he said.

Inquiry at the offices of the Sterling Securities Company, where Miss Pendar was employed as a filing clerk, revealed the fact that she had not reported for work that mornjng. She was found at noon in the room she occupied in one of the old dwellings on the north side of Fourteenth Street, that are now rented out in single rooms to small businesses, to artists and the like.

A hall bedroom on the top floor comprised her whole establishment. The detectives were astonished at the neatness and charm with which she had invested it.

Among those somewhat sordid surroundings it was like a little bower of comfort, with a fire burning in the grate, and a brass kettle boiling water for her tea.

The girl was twenty years old, and very pretty and ladylike. She had childlike blue eyes, and a delicate complexion that changed color easily.

She had, so far, refused to give any information concerning her people. It was supposed that she was one among those thousands of girls who come to the city out of good homes to make their living, and find it pretty hard sledding.

Her salary at the Securities Company was only twelve dollars a week. She explained that she lived as she did, because it was the only way she could support herself on such a sum.

She was terrified at the coming of the detectives. She claimed that the gun had been stolen from her.

As she bore a suspicious resemblance to the description furnished by Mrs. Brick, the detectives held her in talk until that woman could be brought down town and confronted with her. Mrs. Brick positively identified her as the young woman she had met leaving Henniger's pawnshop.

Miss Pendar then broke down and confessed that she had been to Henniger's. She went there, she said, to pawn a brooch in order to raise money to make some wedding purchases.

She found Henniger lying dead on the floor, she explained, and ran out, distracted with fear lest she be connected with the scandal.

She could not account for the finding of her pistol there. That had been stolen from her room, she still insisted.

Her story did not hold water at any point. She could not produce the brooch she said she had gone to pawn, nor tell what had become of it. She could give no satisfactory explanation of why she had chosen a pawnshop in such a remote quarter and so far from where she lived.

Still more damaging testimony was furnished by a number of things such as undergarments, shoes, gloves, et cetera, that she had just purchased, and which were lying on the bed when the detectives entered. She claimed to have bought these things out of her savings.

When they asked her why she had needed to pawn the brooch, then, all she could say was that a girl never has enough money for her wedding.

She was arrested and taken to headquarters. Young Vernay, who had accompanied the detectives to her room, was broken-hearted at this outcome.

A very affecting scene took place when the young people were torn apart. Ii soon appeared that the young man meant to stand by her through thick and thin. Stoutly protesting his belief in her innocence, he hurried off to hire a lawyer.

On the following day, after close and long-continued questioning by Inspector Rumsey, Jacqueline Pendar broke down and confessed that she had shot old Henniger. She now said that it was the pistol, the only article of any value she owned, that she had taken to pawn with him.

After an amount had been agreed upon, she said, Henniger came from behind the counter on the pretext that he wanted to give her a little present The gun was then lying on the counter. It was early, and there was nobody else in the shop.

He became offensively amorous, she said, and finally attacked her, whereupon she snatched up the gun and shot him.

This story had as many holes in it as the other. Nobody believed that an experienced old pawnbroker like Henniger would allow a gun to remain loaded a single moment after he had examined it. The girl said she had dragged the body around the counter and into the cage, to prevent its discovery by any one who chanced to look in the door. But there were no marks on the floor, nor blood stains to bear this story out.

Furthermore, the position of the body when found, gave her the lie. Neither could she explain how the safe came to be open and empty, nor where she got the money to buy her wedding things.

Later in the day it was announced that Leonard Bratton, one of the best known criminal lawyers in the city, had undertaken to defend the girl. Bratton gave out a statement that he was glad to take the case without fee, since it seemed to him a serious miscarriage of justice was in danger of taking place.

He averred his belief in Jacqueline's innocence. The newspapers commented on his statement somewhat ironically since Bratton had never been conspicuous for philanthropic impulses.

While extremely successful, his methods in getting his clients off had been open to question. It was suggested that the publicity entailed would more than make up to him for the lack of a fee.

After having consulted with Bratton, Jacqueline repudiated her confession, claiming that it had been obtained by the police under force and duress; in other words, third degree methods. She now reverted to her former story, claiming that Henniger was already dead when she entered the shop.

Such was the newspaper story. It was generally supposed that Jacqueline had gone to the pawnshop honestly intending to pawn the gun, and had yielded to a sudden temptation upon finding the old man alone, and the safe open.

This, however, left a good many of the circumstances unexplained. A wave of hysterical sympathy went out to her; everybody believed she had done the deed, yet it seemed doubtful if a jury could be got to convict her. Bratton was astute enough to take full advantage of this, hence Jacqueline's denial of all complicity.

Matters were at this juncture when Inspector Rumsey came to our offices to consult with Mme. Storey upon the case. They are old friends.

Rumsey, as everybody knows, is one of the best police officers we have, and moreover, absolutely incorruptible. The story of his having illtreated the girl in order to force her to confess, had made my employer very indignant, and she said so. Rumsey himself attached but small importance to it.

"That's only Bratton," he said; "the story won't stick. Everybody knows what Bratton is."

However, the inspector was in trouble over the case. His position was an uncomfortable one, because her guilt was clear, yet she had become a popular heroine.

"She has such a terror of the police I can't get anything coherent out of her," he said. "Bratton feeds this terror, and uses it for his own ends. I want the girl to have every chance, but naturally I don't want Bratton to get away with murder."

"What can I do?" asked Mme. Storey.

"Question her yourself," he begged. "You are so wonderful in such cases, particularly with a woman. Your psychological insight leads you directly to the truth. They cannot deceive you."

"Oh, you flatter me!" she said, smiling. "My only merit is that I'm a realist I'm afraid your suggestion offers difficulties. I should nave to talk to her here, because the atmosphere of jail or police office would be fatal; and I would have to talk to her alone—or with only Bella present."

"It's irregular," he said ruefully; "but I'll chance it. I'll send her up under guard, and my men can wait in your outer office."

"Very well," said Mme. Storey. "I have followed the case in the newspapers. It offers interesting possibilities."

I AWAITED the girl's coming with a curious excitement It is strange what publicity will do. Jacqueline Pendar had become, for the moment, the most eminent person in New York. Publicity had imposed her upon us like a sort of queen.

However, there was nothing queenly in her aspect. She entered my office between two big plainclothes men like a helpless little bird in the hands of the hunters. It caught at the breast.

She was slenderer and more fragile than her photographs had led me to expect, with childish lips, prone to tremble, and big blue eyes prone to fill. My own eyelids prickled at the sight.

I hardened my heart by reminding myself that this physical appeal was merely accidental. Slender little women have committed murders before this, and they are not any the less reprehensible than if they had been Amazons with budding mustaches.

I led her directly into Mme. Storey's room. She paused at the threshold, and her big eyes swept around wonderingly.

Of course that long high chamber resembles anything in the world but an office; with its art treasures it is like a salon in an old Italian castle, and my beautiful, dark-haired mistress, in her clinging Fortuny robe like a princess of the Renaissance.

"Come in," she said, smiling; "I suppose you know who I am."

"Oh. yes," murmured the girl, "everybody has heard of Mme. Storey; but—I expected—"

"What?"

"I expected you to be more severe."

Mme. Storey laughed outright

"Sit down," she said. "Have a cigarette." She pushed over the big silver box, but the girl shook her head. "We'll have tea in directly. Meanwhile, let us be friends."

The girl gave her a strange look, wary and piteous.

"I mean it," said Mme. Storey. "Have you any women friends?" she broke off to ask.

The girl shook her head dismally.

"I thought as much. A woman has got to have women friends in order to get square with things. Because men never tell us the truth. Even the men who love us never tell us the truth.

"I am your friend. In the beginning I sympathize with every young person who is accused of a crime. I suspect they may not have received a square deal. Life is very hard for the young. And often I go on sympathizing with them, though I am forced to hand them over to what is called justice.

"I shall be frank with you. Inspector Rumsey sent you to me, hoping that I could persuade you to tell the truth. He thinks I am very clever at it. But there's no magic about my methods. I wish to be friends with you. I tell you the truth. That's all there is to it."

A painful struggle became visible in the girl's face. Out of it appeared a dreadful, desperate look of obstinacy, suggesting that she would die sooner than tell the truth.

"It is only fair to warn you," Mme. Storey went on, "that I have read a transcript of all your previous examinations." She touched some papers on her desk. "I must also warn you that anything you say to me can be used against you later. Nevertheless, I recommend you to tell the truth."

"No jury will convict me," murmured the girl obstinately.

"I suspect it was your lawyer who told you that. Perhaps he is right. But if he gets you off through a lie, that will mean you will have to live a lie all the rest of your days. I judge from what I have read of him that Charles Vernay is a man of a peculiar honesty of character. Can you live a lie with him?"

This flicked her. "Charley knows I didn't do it," she cried passionately. "Whatever they may say, he will always know I didn't do it!"

"How will he know that?" asked Mme. Storey mildly.

"He knows I am not brave enough to kill a person."

"H-m!" said Mme. Storey. "Well, let us go over the whole ground. How did you happen to pick on such an out-of-the-way shop as Hennigcr's?"

The girl quickly commanded her outburst of feeling. She answered warily and slowly as if weighing every word—it was painful to see her: "I am fond of taking long walks, madame. Once while walking on a holiday I passed Hennigcr's. The old man had a kind look, I always remembered it."

"Well, why didn't you say so when you were first asked that question?"

"I was so confused I didn't know what I was saying."

"What was your purpose in going to Henniger's?"

"To pawn a brooch, madame."

"What became of it?"

"I cannot tell you. I had it in my hand when I went in. But the shock of seeing him—lying there—" She squeezed her eyes tight shut at the recollection. "I cannot remember. I must have dropped it."

"It was not found."

"Whoever found it kept it."

"What sort of brooch was it?"

"An old-fashioned cameo."

"How is it that Mr. Vernay knew nothing about such a brooch?"

"It was given to me by a gentleman before I knew Mr. Vernay well. So I had never told him."

"Who was this gentleman?"

"A gentleman who worked in the same place where I did. He is dead now. That is why I couldn't return the brooch after I became engaged to Mr. Vernay."

"Oh," said Mme. Storey.

Indeed it was only too clear that the unfortunate girl was lying. My mistress passed on to something else.

"Why did you lock the door in Mrs. Brick's face as you came out?"

"Oh, I was so frightened!" whispered the girl with a shudder. This was no doubt genuine enough. "Of being mixed up in a murder case, I mean. I thought if I could only get away they would never find me. I couldn't bear to think that Charley would learn about the brooch and all."

"Then what did you do?"

"The next thing I can remember clearly is riding down town on an elevated train."

"Then you went to buy your wedding things?"

"Yes, madame."

"Where did you get the money?"

"It was fifty dollars. I had been saving it up for years for that purpose, a few cents at a time."

"But isn't it rather strange, after having had such a hideous shock, that you should go out and buy your pretty things then?"

"I had taken the day off for that purpose, madame. Of course it was terrible to see the old man lying like that, but after all he was nothing to me. I soon got over it. New York is so big I never thought they would find me again."

"How did your pistol come to be in Henniger's pawnshop?" asked Mme. Storey softly.

"I don't know, madame. It was stolen from me."

"Now, come. Miss Pendar," said my mistress in friendly fashion, "you cannot expect anybody to believe that somebody just happened to steal your pistol, and that the thief just happened to murder and rob old Henniger in his out-of-the-way shop, and that you just happened to enter the shop a moment later to pawn a brooch!"

"I can't help how unlikely it sounds," murmured the girl. "It's the truth!"

"When did you first miss the pistol?" asked Mme. Storey.

"Not until the detectives came to my room asking about it. I ran to my bureau and—"

"Wait a minute!" interrupted Mme. Storey kindly. "Don't lie unnecessarily." She turned over the papers On her desk. "The detective makes no mention of your having run to your bureau. He says you accepted the fact that the pistol was yours without question."

"Well—maybe I did," drearily murmured the girl, hanging her head. "It is my character to believe what anybody tells me."

There was something unspeakably piteous in the way she said it. One visualized her as a poor little chip whirled on the currents of life without any power to resist them.

"Where did you keep the pistol?" asked Mme. Storey.

"In the top left-hand drawer of my bureau."

"What else was in that drawer?"

"Handkerchiefs, stockings, and other small articles."

"Was the gun wrapped up in anything?"

"No, madame. Charley said it must be so I could snatch it right up if I needed it."

"Then if you had opened the drawer you must have seen that it was gone."

"I suppose so."

"Hadn't you got out a clean handkerchief that morning?"

"I can't remember."

"When did you see the gun last?"

"The afternoon before, when I came home from work. It was in my drawer."

"Oh, you remember that?"

"Yes, madame."

"According to that, it must nave been stolen some time that night?"

"Yes, madame."

"Had you and Vernay ever practiced shooting the gun?"

"No, madame. We had no place where we could. But Charley had showed me how it worked."

"Did the trigger pull easily?" asked Mme. Storey casually.

The girl saw the trap and avoided it. "I don't know, madame. I never tried it." She shivered. "I was afraid of it."

"You were always conscious of the ugly little black thing lying in the drawer there, like an animal alive and vicious?"

Jacqueline gave her a startled glance.

"Y-yes, madame."

"Describe what you did the night the gun was stolen," went on Mme. Storey.

"I came home from the office at the usual time, about half past five."

"The gun was in the drawer then?"

"Yes, madame. I cooked supper. I went to bed about eleven. That's all."

"Didn't Vernay come to see you?"

"No, madame; it was not his night."

"Not his night? What do you mean?"

"Three nights a week, Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, Charley attended night school to improve himself."

Mme. Storey turned over her papers.

"But in a statement made by Wickford, the artist in the adjoining room, he stated that Vernay came to see you every night."

"He was mistaken," said the girl. "I suppose he saw him different times, and just thought that."

"Did you have any other visitor?"

"No, madame," replied the girl, blushing. "I never had any visitor but Charley."

"You went to bed at the usual time," resumed Mme. Storey, "and you got up at the usual time?"

"Yes, madame."

"What sort of lock was there on your door?"

"An ordinary lock with a key. And besides that Charley had put up a chain so that if anybody knocked I could look out before opening the door."

"Was the chain on when you got up that morning?"

"Yes, madame."

"Then how could you have been robbed?" asked my mistress softly.

The girl was brought to a stand. Her wide eyes started out of her white face. "I—I don't know," she faltered.

"Quiet!" said Mme. Storey. "Nobody is threatening you. We are just three women here together." She lit a fresh cigarette to give the girl time to recover herself "Why did you tell Inspector Rumsey that you shot him?" she asked after awhile.

"I—I scarcely knew what I was saying," murmured the girl, breathing fast. "It seemed the easiest way out. I knew they wouldn't punish a girl for defending herself."

"The easiest way out of what?" asked Mme. Storey.

The girl clapped her hands to her head.

"Questions! Questions! Questions!" she gasped. "I was frightened out of my wits!"

Mme. Storey's face was grave with pity. "Well, let us go back to the night before," she said.

Though her voice was soothing, Jacqueline was not reassured.

Through her lashes I saw her dart a look of fresh terror at my mistress.

"What did you have for supper?" asked Mme. Storey.

"I bought a chicken croquette on the way home."

"Only one?"

"I am a small eater, madame. I also baked a potato in a pan on top of the gas plate."

"Where did you buy the croquette?"

"In the delicatessen on University Place, just below Fourteenth."

Mme. Storey made a note of this on a pad, and for some reason her act caused the girl to shake with terror. "Did you get anything else there?"

"Not then," said Jacueline tremblingly. "Later I got a loaf of bread."

"Oh, you forgot the bread?"

"Well, I had some, but not enough."

"Oh, you eat a lot of bread, then?"

"No—yes—no," she faltered. "No, not much."

"Did you get anything else?"

"A quarter of a pound of butter for the bread. And—and some cold meat. That was so I wouldn't have to shop the next night," she hastily added.

"I see. How could you keep it?"

"In a little covered dish on the window sill."

"How much meat?"

"Half a pound of cold ham."

"Half a pound!" said Mme. Storey, raising her eyebrows.

A rule sweat had broken out on the girl's forehead. It was pitiful to see her terror. "I—I was expecting Charley to supper the next night," she stammered.

"I see," said Mme. Storey. "Then the ham and the loaf of bread, or the greater part of it, will still be in your room?"

"How do I know?" cried the girl in a shaking voice. "How do I know who's been in my room?"

"When you were taken away, the police locked it and took the key," said Mme. Storey. "No one can have been in there."

"Well, from what you hear, the police are not above suspicion!" cried Jacqueline hysterically. "If the bread and the meat are gone, it won't prove anything! I'll be lucky if I find anything in my room when I get back."

Mme. Storey interrupted her in a grave voice:

"Jacqueline, who ate the bread and the meat?"

"Nobody! Nobody! Nobody!" she cried, beating her fists against her temples. "It was there when I left!"

"You had an unexpected guest for supper," said Mme. Storey, rising like Nemesis. "That was why you had to go out for more food. While you were out your guest betrayed you. He—I am merely assuming that it was a man—stole the pistol out of the drawer of your bureau.

"You did not discover the theft until you went to the drawer for a clean handkerchief the following morning. Something had been said which led you to suspect that there was a design against the old pawnbroker. You hastened up to his shop to prevent a crime. You found you were just a little too late."

The girl spread her arms on Mme. Storey's desk and dropped her head upon them, weeping piteously.

"You are too clever for me!" she sobbed. "I hope you're satisfied! Oh! I wish I was dead!"

"Nonsense!" said Mme. Storey gently. "You have cleared yourself. Anything is better than being suspected of murder."

"No! No! No!" wailed the girl. "Charley will leave me when he hears this! I cannot live without Charley!"

"You poor child! You poor child!" murmured my mistress, laying a hand on her hair. "Perhaps your fears deceive you. Tell me the whole story."

We had to wait for a little before Jacqueline was able to do this coherently. Mme. Storey had tea in, and we fed the girl.

My dear mistress exhibited a Heavenly kindness toward her, as if to assure her that however "Charley" might take these disclosures, she, Mme. Storey, would stand by her. Finally Jacqueline began to talk. The little thing, with her drawn, white face, looked piteously childish.

"Last summer when I first moved into the Fourteenth Street house," she said, "before Charley had put a chain on the door, one night there was a knock, and when I opened the door a young man pushed into my room before I could keep him out. But he was not rude to me. He was half out of his wits with terror.

"He said the police were after him, and he begged me to hide him. I was so sorry tor him I could not say no. He was so young a mere lad, and so nice-looking. I let him creep under my bed, and when the police came up I told them he had run up the ladder and out on the roof.

"When they went up there the young man slipped downstairs again. He kissed my hands in gratitude. He was so nice, so well spoken, I could not believe he was a thief; I thought there must be some mistake.

"A week or so afterward he came back. He said the police had forgotten him by that time. He brought me some flowers growing in a pot, and a box of candy, and a pretty brooch—many things; but I made him take them all away again, because of Charley. Except the candy. We ate that.

"He stayed awhile and talked. I thought no harm of it, he was so nice. He did not make himself out to be any better than he was. He told me he had robbed a cigar store that first night, and the police had seen him as he was coming out.

"He said he had been a thief ever since he had been a boy on the streets, but that I had made him ashamed of himself. He said he had a regular job then. He promised to lead a decent life if I would be his friend. It made me proud to think I was a good influence in somebody's life.

"After that he came often. He found out the nights that Charley went to school, and always came then. Sometimes he was broke and hungry when he came, and I fed him. Other times he would come with great armfuls of food, lobster, and plum cake, and all kinds of silly things, enough for a dozen.

"Then he would be in great spirits, and I'd have a time keeping him quiet. I never knew when he was coming. It was so exciting. He would always tap in a certain way to let me know who it was.

"I was terribly uneasy on account of Charley; but I could not tell him. He is so very honest he would have had no sympathy. Jealous, too. If any man so much as looks at me it puts him in a fearful rage.

"And of course when I did not tell him in the very beginning, I could never tell him after.

"The other one's name was Dick Preston. He swore to me that he had gone straight ever since he had known me. But of course I don't know, now. Sometimes he would go down on his knees at my feet, and put his face in my hands and cry, and say that I had saved him.

"Dick told me all about his life before he met me. It was fascinating to me, so wild and strange; robbing and running from the police; traveling all over the country. He had been in prison, too; his adventures would fill a book. It made an ordinary life seem tame.

"I always gave him good advice, and he seemed to be grateful for it. It's true, he fascinated me, but not in any wrong way. I couldn't feel toward any other man like I do toward Charley. There was nothing wrong between us!" she cried. "He called me his good angel. But no one will believe that now."

Her head went down on her arms again.

"I believe it," said Mme. Storey. Jacqueline resumed with a weary sigh.

"The last time he came he was very depressed. He had lost his job and was broke. So I went out and got bread and meat to feed him. He told me he had met a former pal, who had put up the job to him of robbing an old pawnbroker on Mutual Avenue, up in Harlem. The old man was always alone in his shop mornings, he said, and it would be a cinch.

"But Dick said he had turned his pal down. He said he would sooner starve than go back to that life. Then it all happened just as you said. In the morning I discovered that he had stolen my pistol."

The girl's voice shook.

"Such treachery! I never knew there were people like that I was stunned! Then I remembered the old pawnbroker. I went up to Mutual Avenue on the L. I was too late.

"It was all lies!" she cried with indescribable bitterness. "I didn't do him any good at all. He was only fooling me!" The childish head went down.

FOR a moment none of us spoke. For me the story registered a new depth of human baseness. It was incomprehensible how anybody could so deceive and injure the gentle child. One's breast burned with indignation.

"The perfect blackguard!" commented Mme. Storey with a grim air. "I know the type; the emotional blackguard. He would hide his face in a woman's hands and confess his sins in tears. Ha! I only hope they catch him!"

"Well—that's all," said Jacqueline with a piteous little shrug. "What are you going to do with me?"

"I must return you to your guards now," said my mistress, "but I promise you you shall soon be free."

"Free!" she exclaimed with a twisted smile. To see such bitterness in a creature so soft and gentle was unspeakably painful.

She finally went away with an apathetic air in the company of her plainclothes-men as if nothing mattered to her any more.

At Mme. Storey's command, I immediately called up Charles Vernay at the works of the Amsterdam Stamping Company. Half an hour later he was in our office.

The newspapers had not misrepresented him. Picture a brown-haired young man, radiant with health, every move of whose strong body revealed the elasticity of his muscles. He had that particular look of openness and honesty that only accompanies physical strength.

One likes to think that young men were originally intended to be like that. In the age of heroes they were like that if one may believe old tales; but in these days of jazz and complicated neuroses they have become so rare as to be remarkable.

He was still in his rough clothes, having had no opportunity of changing, but though he was only a shipping clerk he was every inch a man. I could understand Jacqueline's fear of him, too.

To a woman there was a suggestion of danger in his close shut mouth and steady gaze. It added to his attractiveness. He was deeply troubled, as was natural.

He entered Mme. Storey's room with a wondering air. Though he was quite single-hearted as regards women, he was man enough to be sensible of my mistress's beauty and charm, and when he looked at her his strong face softened in that way which is so flattering to women—to my mistress as well as another.

He sat down. It appeared that he knew all about Mme. Storey, so no elaborate explanations were necessary. She said: "Inspector Rumsey is an old friend of mine. He has been here to consult with me about Jacqueline. That's why I asked you to come. You don't need to tell me that you're having a bad time over this."

"I just can't understand it," he said with a strong gesture. "It's impossible that Jack could have shot the man. If you knew her as I do! Why, she couldn't hurt a fly! But there's something—Henniger was certainly shot with the gun I gave her. If it was stolen from her I can't see how she happened on the same shop almost at the moment he was killed. I could stand it if she had killed him, but this uncertainty! They won't let me see Jack alone. It's driving me out of my mind!"

"Well, you can be at ease now." said Mme. Storey. "Jacqueline has told me the whole story. I want you to hear it in her own words before you get any other version."

He sprang out of his chair with wild eagerness—there was fear in his eyes, too. He was no fool. His instinct had already told him there was something here that would make very unpleasant hearing.

"Bella," said my mistress to me, "read Jacqueline's statement from your notes."

I proceeded to do so. I felt so strongly for the young man that I was hard put to it to keep my voice from trembling. He sank back in his chair, and out of the tail of my eye I could see him crouching there, tense and stiff.

When I had finished he leaped up. "By Heaven!" he cried hoarsely. "Another man!" There was a terrible look in his eyes.

"Sit down," said Mme. Storey quietly.

"No! No!" he said with a violent gesture. "I can't discuss this with anybody." He started for the door. "Lock the door. Bella, and put the key in your pocket," she said swiftly.

I was near the door. I managed to obey, though he came charging down on me like a locomotive.

"You can't get out unless you attack my secretary," said Mme. Storey mildly. "I don't suppose you want to do that."

He turned away from me with a groan that seemed to be forced from the depths of his being. Dropping in another chair, he rested his elbows on his knees, and pressed his head between his palms. My mistress gave him time to recover himself a little.

"What do you want of me anyway?" he groaned out at last.

"To reason with you," said Mme. Storey.

He lifted a tormented face.

"Reason!" he sneered. "She has deceived me! I staked everything on her!"

"Leave Jacqueline out of it for the moment," said Mme. Storey. "Consider me. When you came in you told me you had followed several of my cases in the newspapers. You expressed an admiration for my psychological acumen. Isn't that so?"

He nodded sullenly, very unwilling to consider anything but his own great trouble.

"Well," said Mme. Storey softly, "my powers, such as they are, are at your service in this crisis of your life. Why not use them?"

"What do you mean?" he demanded scowling.

"I have been called 'a practical psychologist, specializing in the feminine,'" she said with a twinkle. "Do you not wish me to analyze this statement?"

He was greatly struck by this. A struggle took place in his sullen face.

"Let me go away by myself and fight it out," he mumbled. "I'll come back."

"No," said Mme. Storey, "you would certainly do something you would be sorry for all your life. Stay here and fight it out with me."

His head went down between his hands again. His strong fingers twisted in his brown hair. He looked appealingly boyish.

Finally he muttered sheepishly: "All right. Give me hell. Expect it's good for me."

Mme. Storey laughed. She rose and walked about while she talked.

"This Dick Preston is an unmitigated scoundrel," she said, giving my notebook a rap with her knuckles, "but that doesn't reflect on Jacqueline at all. You and I would have known it at a glance, but her innocence was deceived. She was sorry for him, she says. Are you going to blame her because she succored this wretch out of her kindness? The very phrases she uses testify to her sweetness of heart.

"She was fascinated by his stories of crime; of course she was being so simple and good. She wanted to help him to be good; she felt proud because she thought she was able to help somebody. Everybody else treated her like such a baby.

"There's a word of warning for you, my lad. Treat her less like a baby, and she will reveal unexpected grown-up qualities. This subtle-minded thief knew how to melt a woman's heart; he confessed his weaknesses to her. A strong man might learn something from that, too.

"In short, what is revealed in this confession? Goodness, gentleness, kindness of heart. God in heaven, my friend, what more do you want in a wife? Every sentence here betrays her love for you; an unselfish, all-embracing love. I assure you that kind of love is rare in these days of enfranchised women. It's too good for you.

"You must excuse my heat, but a man's jealousy and unreasonableness make me mad! The perfect flower of love is offered to you, and you want to trample it underfoot. It takes a selfish and a self-seeking woman to keep you in order!"

There was a good deal more of this. Mme. Storey did not spare his sex. Her eyes sparkled and her voice was crisp. One gathered, from the hang of his head, that the young man was taking it humbly enough.

Then she smiled at her own heat, and went on smiling. "I tell you, you'll be lucky if you get her. You and she would make a good match. I wouldn't say that to a weak man, but you, I take it, are strong; strong in body and strong in character. However, don't play up your strength too hard. Encourage her to stand alone.

"Confide your weaknesses to her gentle hands, and let her be strong for once in a way. A well matched pair! Oh, I know, an engaged couple isn't going to pay any attention to the opinion of a psychologist upon their marriage, but, anyhow, there it is for what it's worth. A well matched pair!"

She took a cigarette. The young man raised his head, but did not care to meet her glance. His face still wore a hangdog look, but it was much softened. Like a young man, he was trying to hide from her bow much softened he was.

"You're right," he muttered. "I'm straightened out now. Certainly it was good of you to take so much trouble with me. I can't properly tell you what I feel—how thankful I am to you."

"Don't try," said Mme. Storey quickly.

"If you'll unlock the door," he muttered, I promise you I won't do anything foolish now.'

"What are you going to do?" she asked, approaching him.

"Going down to see if they will let me see Jack. Going to put myself in her hands," he added softly.

"Good man!" said Mme. Storey, giving him a clap on the shoulder.

He picked up her hand in a sheepish way, and pressed it hard, then hurried out.

Mme, Storey came back to her desk with a beaming smile.

"Not such a bad afternoon's work, my Bella," she said. "Did you hear how I pitched into him? That's the proper tone to take with a jealous man. Mercy! wasn't he good-looking?" She was much more deeply moved than she cared to show.

"When I first went into business," she went on with a slow smile, "that is how I pictured myself acting; straightening out tangled humans. But, alas! I soon found that tangled humans don't want to be straightened out; they refuse to be straightened out. So nothing remained for the exercise of my talents but solving crime. Well, bring on your crime!" she cried gayly. "Those letters in the Rampayne case must be answered before we close up shop to-night."

It only remains to say that some weeks afterward the young man who described himself to Jacqueline Pendar as Dick Preston—he had many other names—was discovered lying on the steps of Gouverneur Hospital in the early morning, mortally wounded. His friends, after smashing a window of the hospital to call attention to him, drove away.

It turned out that he had been shot in an affray between bootleggers and hijackers. Before he died he made a statement which completely bore out Jacqueline's story, and with him in the grave were laid away all the ghosts that might subsequently have troubled the married life of our young friends.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.