RGL e-Book Cover

(Based on an image generated by Microsoft Bing)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

(Based on an image generated by Microsoft Bing)

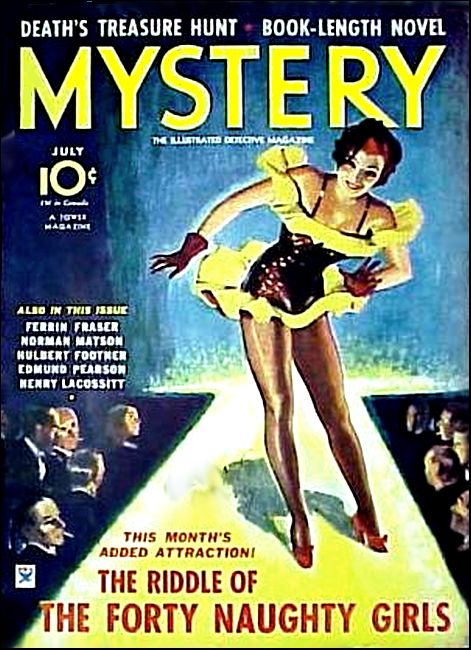

Mystery, July 1934, with "The Man with the Crooked Finger"

FRED was sore. When they pulled up in front of Edda's boarding-house he broke out: "Absolutely heartless! Absolutely heartless. I'd give my life for you, and you ship me with a wisecrack!"

Poor Fred! thought Edda. He's a sincere boy, but there's a deficiency of lime in his composition. She said nothing.

"I'm mad about you!" Fred went on, "and all you want is to borrow ten dollars!"

"I'll pay it back," she said meekly.

"You won't get the chance! It's got to be all or nothing with me! You'll never lay eyes on me again!"

He embraced her with a kind of desperation. Edda submitted since it was for the last time. When he let go of her she patted her hair into place with a sigh. If he was going to take it like this it was impossible to beg him for the money. "Don't get out," she said, "I have my key."

She ran up the steps and waited in the vestibule until Fred's car roared away down the street. Then she came down the steps. The truth was she had no key. It had been taken from her earlier in the evening after a scene in the lower hall on her way out. Also the suitcase she was earning. She had been told that she needn't come back unless she brought something to pay on account. Young Fred's love-making had been so cyclonic she hadn't been able to tell him the situation. Midnight was a little late to start looking for a lodging. And a little model in oyster-white satin with a bunny wrap, not much to face the world in. There was nothing in her beaded evening bag but handkerchief, cigarettes and compact. Not one red penny! "Thank God. I have a friend." she thought. "I'll just have to walk up to Mildred's place. What if Mildred isn't home?" Brhh! She refused to face that possibility. A man came charging around the corner from Lexington Avenue. He pulled up short; raised his hat. "You're too pretty to be out alone," he said. "I'll walk home with you." Meanwhile he was rapidly turning up his hat-brim and throwing open his overcoat, revealing evening dress beneath. Slipping his arm through Edda's, he urged her forward.

Before she could adjust herself to the situation, another man came tearing around the corner; hard blue eyes; outsize feet. He stopped and ran a suspicious eye over him. Edda's escort was saying in an easy voice: "Ya-as, I'm dated up with the Rumseys for the hunting."

"Did a guy just run by youse?" demanded the plainclothes man. "Eh, what? Oh, surely, officer!" said the man. "I turned my head to look at him. He ran in an areaway near the end of the block, this side."

The officer ran on. Edda's companion steered her briskly around the corner. A taxi came trundling up. "Hop in," he said, "I'll take you anywhere you want." Edda lost no time in obeying. Here's a bit of luck! she thought. "Where to, Mister?" asked the driver.

"Just keep on," was the answer, "and step on it, Sir Malcolm."

EDDA took a look at her fellow-traveler. The passing lights gave her flashes of a Times Square grin; hard-boiled. "What was the trouble you had?" she asked politely.

"Well, a fellow owed me some money, and I went to collect it. We had words and he hollered out of the window for a cop. It seemed easier to beat it than to stop and explain."

Likely story! thought Edda. "I like policemen," she remarked, just to be saying something. "They're so physical!"

Her companion, it appeared, did not share her feelings about policemen. Neither had he any opinion of their cleverness. He related several anecdotes to prove his point. "Aah!" he said, "as long as your money holds out, the cops can never catch you! All you got to do is register at a first-class hotel and have your meals sent up."

While they bowled along and made friends talking, he began to inch across the seat. Edda knew the signs.

Finally he said: "What's your name, kid?"

"Edda Manby."

"Cute name! Mine's Jack Scanlan.... Kiss?"

"Nothing doing," said Edda.

"All right. Where do you live?"

"I'm going to a friend's flat on Forty-sixth around the corner from Lexington. You've saved me walking."

"What's the matter? You broke?"

"Abso-stony-lutely." She told her little story. Old stuff. No job. No job. No job. And always the grim necessity of keeping up the facade in order to get a job.

"You should worry," said Jack. "You have personality. You can always cash in on personality. Why don't you go on the stage?"

"I'd rather have a job," said Edda. "I'm strong for regular meals."

"With your looks you wouldn't have to pay for your meals."

"I know, but a girl gets tired of being bright at meal-times. I'd sooner be myself and pay for my own."

"I'm on the stage," he volunteered.

"Oh, yeah?" said Edda politely. She thought: It hasn't done much for you.

"First time I ever heard of a good-looking doll passing up the stage."

"I'm not passing up anything right now."

"I could put you in the way of getting an engagement."

"It would have to be quick."

"Well, maybe we can get hold of the guy I have in mind tonight. If he likes you you could touch him for an advance. Come on up to my place and we'll talk it over...." Warned by the look in Edda's eye he quickly added: "My wife's there."

"Where is it?" asked Edda.

"East Forty-ninth."

Edda thought: Well, if I don't like the set-up, its near Mildred's.

"All right," she said.

Jack gave the address to the driver.

IT was an old-time walk-up house east of Lexington, with a sporting flavor. The original apartments had been subdivided into many small flats rented, furnished, by the week. Late as it was the tenants were still going in and out; Lexington Avenue stars. A landlady sat at a desk in the downstairs corridor looking them over. She was equal to her job. From the temperature of her greeting to Jack, Edda drew her own conclusions. Pretty near zero.

In the lighted corridor Edda got her first good look at him. The semi-darkness had flattered him. Youthfulness was his line, but it was beginning to pull at the seams. Thirty-eight, she decided. There was a yellow look in his eyes that made her cautious. They climbed three flights under their own power, and Jack led the way to one of the little flats in the rear. He knocked in a certain manner; knock, pause, three knocks, pause, knock. The door was opened by a beauty-parlor blonde with smoky eyes who had rather a fallen look without her girdle. She was crabbed.

"Who the hell is this?" she demanded as they walked in.

"Edda Manby," said Jack. "Helped me to stall off a cop down in Thirty-sixth Street."

"So you fumbled the job!" she said bitterly.

"You can't always bring home the bacon."

"Ought to have gone myself," she muttered.

"Edda's broke and wants a job on the stage," said Jack. "I thought it might lead to something if we introduced her to the Colonel."

He was behind Edda, and the latter had a hunch that there was some conjugal signaling going on. However, she was not going to pull out just because there was a tang of danger in the situation. The blonde's name was Maud. Her animosity cooled, and she appraised Edda with the eye of an expert.

"Her figure's all right," she said, "but her map's a little out of drawing."

"A slight irregularity of feature is the essence of charm!" said Jack. "At least that's what they say."

"Oh, yeah?"

"And boy! I'll say she has spizz!"

"How do you know?"

"Didn't I ride up with her in the taxi?"

Maud suddenly became friendly. "Sit down, dear," she said. "Will you have some beer?"

Edda declined.

"It's a good thing," muttered Jack. "Beer's out."

"Well, you needn't exhibit our poverty," said Maud, smiling like a fond wife.

They all sat down. Under the guise of light talk Maud put Edda through a pretty stiff examination. In the bottoms of her smoky eyes she was doping things out. Edda, keen to find out what was coming of all this, gave her the answers she wanted. Finally Maud said she would dress. In passing Jack she gave him a signal, and he followed her into the bedroom, while she waited. Edda's eyes strayed around the sitting room. It was furnished in the golden oak period when pillows had frills. From behind the closed portières Maud flung out an occasional bright remark. In between Edda could hear whisper, whisper, whisper. Jack was getting his instructions.

Maud reappeared looking very svelte in her girdle and white evening gown. Edda wondered idly where she had checked the excess. Maud said:

"I'm going to round up the Colonel. You stay here until I phone."

When she had gone, Jack drifted around the room looking at Edda out of the corners of his eyes. The walls were thin and there were plenty of people around. Edda didn't mind. After a while he said:

"That little crooked smile of yours drives me crazy!"

"Think of Maud," said Edda.

"Maud! Hell! She's a broad-minded woman. She wouldn't care unless it was absolutely forced on her attention."

"Nothing to it!" said Edda. "I have other plans."

"You don't know me," said Jack. He started for her.

She saw it coming, and already had the door open. "I'll wait for you down in the street corridor," she said. "You stick by the phone."

He followed her, pleading: "Aw, have a heart, Edda." He couldn't go down without making a fool of himself before the landlady. Edda left him at the top of the stairs, and descending to the street floor, took a seat in the corridor. The landlady gave her a dirty look, but Edda didn't owe her any money. She could bear it.

WHEN Jack came along a while later his softer mood, if you can call it that, had changed. His close-set eyes were full of business now—bad business. "Come on!" he said out of the corner of his mouth, he added: "That other taxi got my last half- dollar. We'll have to walk. It's not far."

"Just how far?" asked Edda.

"Borneo Bicycle Club, a 'speak' in Forty-fourth. Maud and the Colonel will meet us there. The old man can't climb our stairs on account he's got a bad heart."

The club was east of Lexington in one of a row of old brownstone fronts that had seen better days. Crowded inside. No style to it. One of those alleged gangsters' hangouts that give Park Avenue dames such a thrill. The slick waxy-faced little guys sitting around might or might not have been bona fide killers. Anyhow, Raymondo, the proprietor, was making a good thing out of it. This Raymondo was a fat little Italian in a tuxedo, with a face you could absolutely break rocks on.

Maud and the Colonel arrived almost at the same moment. Edda suspected at a glance that the Colonel was not in the theatrical business and never had been; he was too conservative. More like a big banker who sat in his office all day with slaves pussyfooting in and out on Oriental rugs. At two o'clock in the morning in a shady speakeasy with his top hat on one side of his head he was merely a number one sucker.

"Meet the kid sister, Colonel," cried Maud. "It's her first night in town!"

Gosh! thought Edda, is this intended to be taken straight?

The rosy, white-haired Colonel rolled her hand between his as if it were a lemon he was softening. "She's a duckling!" he said. He drew her hand through his arm, patted it and surveyed the room like a conqueror of the sex. "How about a little drink?" he asked.

"Let's go upstairs," put in Jack.

To Edda, this was like the flash of a warning signal.

"Oh, not upstairs!" she protested. "I like to watch the crowd."

"Nonsense, darling," said the Colonel. "It's a nasty crowd."

Edda found herself neatly separated from the Colonel, and swept up the stairs as if by an irresistible force. Everybody was talking and laughing. Her protests passed unnoticed. Raymondo ushered the party into a room at the back that was filled with dining-room furniture and an immense Chesterfield. A cynical looking waiter appeared carrying a magnum of champagne in a bucket of ice.

"It's chilled." said Raymondo rubbing his hands. "You can open it right away."

Raymondo and the waiter stole out, closing the door behind them as softly as a kiss. Edda noticed two things about the room; firstly there was a key in the door; secondly an iron fire escape outside the window. There was no let-up in the storm of speakeasy talk, which never asks for an answer. The Colonel drained his glass at a gulp, and Jack instantly filled it.

As time passed, his red face kept setting redder and his white hair whiter by comparison. Across from Edda he courted her in the flowery style of his youth. She got more and more uneasy. Not for herself but for him. Something was beginning to click in her mind. If there had only been some way of sending him a telepathic warning without words!

At about the fourth glass the Colonel demanded that Edda come and sit beside him. Maud, smiling, changed places with Edda. The Colonel dragged his chair close and put an arm around her. She did not repulse him. On the contrary, she affectionately rubbed her cheek against his. This brought her lips alongside his ear.

"Do you know these people?" she whispered.

Turning his head slightly he whispered back: "Never saw the woman but once before. Don't they belong to you?"

"No! They're crooks."

"What about you?"

"They just picked me up an hour ago."

FROM the other side of the table Maud and Jack looked on at the whispering with fond smiles. Everything going fine!

The Colonel whispered: "I'd better get out of here!"

"Suggest that we all leave," answered Edda. "Easy to shake them outside."

To her relief he proved less foolish than he appeared. He didn't break out and precipitate trouble. For a while the loud talk went on. Like dogs barking; big dog, middle-size dog, little mutt yelping. In the end Maud herself gave the Colonel an opening. She said:

"Can't drink another drop unless I eat something."

Jack put in: "You can order anything you want here."

"Don't let's eat in this joint," said the Colonel. "Let's go to the Conradi-Windermere. It's only a step."

"You can't get anything at the Conradi-Windermere at two in the morning," said Jack.

"I can," said the Colonel, slapping his shirt front.

"The Conradi's too grand!" objected Maud. "It's more folksy here at Raymondo's."

The Colonel made out to be a little drunker than he was. "I'm paying, ain't I?"

Jack made haste to smooth him down. "Just one more glass, and then we'll go. It's a shame to waste this good wine."

"Take it with us," said the Colonel. "Drink it in the taxi."

He pushed his glass across the table to be refilled. Jack's aim was uncertain, and he knocked the glass to the floor, smashing it. Laughing foolishly, he carried the bottle to the sideboard, and filling another glass, brought it back.

The Colonel started to drink it—and stopped. His drunkenness dropped away. He stood up so quickly that his chair fell over. He blew out the wine in his mouth, and dashed the glass to the floor. "It's drugged!" he said. "You damned blackleg! You doped it when you went to the sideboard!"

Jack was also on his feet. His face turned sharp and rat-like. "You lie!" he snarled. "You can't make a charge like that and get away with it! Apologize!"

The Colonel swelled up. "To you?" he said. "Don't make me laugh!" He started for the door.

Edda, sliding out of her chair, instinctively backed against the wall. Maud remained all hunched up in her chair, staring wildly. Jack, swift as a gliding snake, reached the door first, turned the key, put it in his pocket.

"Apologize!" he snarled.

The Colonel snapped his fingers under the other man's nose.

"Open that door!" he commanded, "or I'll kick it down!"

Jack, with his shoulders drawn up like a hunchback's, whipped a black automatic out of his hip pocket and poked it against the Colonel's shirt-front, left side. Edda noticed that the crooked finger exactly fitted the trigger. "Back up, old man!" he snarled. It was a miscalculation. The Colonel proved to be the one man in a hundred or so who could not be stopped. His big hands closed around Jack's throat. Jack fired. The old man dropped like an ox when the axe descends, sprawling on the floor. His upper false teeth were jarred out. A showy crimson stain spread on the white shirt-front. His blue eyes remained open with a perplexed, questioning expression like a child's.

Edda stood, pressed against the wall, taking it in. She could feel nothing as yet. Maud was fetching her breath in a series of little gasps as if she was trying to save up enough to scream and could not. Jack put up his gun and dropped to his knees. His bony deformed fingers ran through the dead man's pockets.

"Out!... Window!... You know the way!" he snarled at Maud. "...Raymondo can hold the bag this time," he added with a spurt of laughter.

MAUD ran staggering and gasping to the window, threw it up and climbed out on the fire escape. Edda snatched up her wrap and followed. It seemed the only thing to do. As she turned around to descend the ladder she saw Jack frisk a wallet from the dead man's breast pocket. People were pounding on the door now. Jack sprang for the window and came down the ladder so fast he stepped on Edda's fingers.

They dropped off the end of the ladder into a backyard. All quiet here. A door in the back of the fence let them into another yard with the back of a house facing them, windows all dark. At the side of the house was an arched passage ending in an iron gate with a spring lock. Up four steps and they were in Forty-seventh Street with a taxicab waiting at the curb. It seemed providential until it occurred to Edda that it had been planted there. Maud scrambled into the cab, and Jack after her. As Edda was following, he leaned out and thrusting her back with a foul oath, slammed the door. The taxi jerked into high and raced away, leaving her.

Edda automatically started walking as fast as she could away from there. To run would have been fatal. She couldn't think. There was not a soul in sight in the long street with its little pools of light. With a groan of relief she got around the corner into Lexington; a short block and around another corner into Forty-sixth, Mildred's street.

The house was four doors from the corner. It was a more modern walkup apartment. The entrance door was always unlocked and you were supposed to ring inside. Mildred lived on the ground floor just inside the entrance. Edda knocked and rang with a mad longing to get on the other side of a friendly door.

There was no answer. At her feet stood an empty milk bottle with a note for the milkman stuffed in its neck. Edda pulled it out. It read: "Leave no milk until Monday. Gone out of town." Edda leaned against the door feeling sick.

Somehow or other she found herself alongside one of the side doors of the Conradi-Windermere, and turned in blindly. A corridor led her to the great central lobby which was quite empty, and had most of the lights turned off. She sank into an overstuffed chair, closed her eyes, and waited for whatever was going to happen.

A super-bell-hop approached and asked if she was waiting for anybody. Edda, who thought she was all in, discovered that she still had reserves. Her tongue of its own accord started saying quite naturally.

"Please ask at the desk if there is any message for Mrs. Manby of Montclair. There was some trouble in a speakeasy where I was having supper and I became separated from my friends. I came here because we dined here—we always dine here when in town, and I supposed that my friends would look for me here." The bell-boy went away to repeat this to the night clerk at the desk. Out of the corner of her eyes Edda could see the two of them looking her over. She crossed her feet, and carelessly smoothed her skirt. At any rate my appearance is all right, she thought.

The boy came back. He said: There is no message, Mrs. Manby. But the night manager says he will be glad to accommodate you with a room until you get in touch with your friends."

"Oh, very well," said Edda. "Most kind I am sure."

WHEN she awoke next morning the sun was streaming through the windows. She gazed at her surroundings in astonishment; the luxurious bed with its satin coverlet; the elegant furniture, the rare rugs. An ormolu wall clock informed her that it was ten-twenty. Had she been wafted to Hollywood or what? Then recollection rushed back and she shivered. She craved food to restore her courage. She put out her hand to the telephone, wondering if the fairytale would stand her for a breakfast.

It came, and with it a copy of the latest newspaper. The service was as deferential as if Edda had possessed a million-dollar roll. Why be insulted in a cheap boarding house when you can live for nothing at the Conradi-Windermere, she asked herself. She ate sitting up in bed with the newspaper spread beside her. The unlucky Colonel had made the first page all right. Boiled down it ran:

"Shortly after three o'clock this morning the body of an elderly man in evening dress was discovered by a passing motorist in the Forty-second Street tunnel near the East River. He had been shot through the heart. Identification was established by means of a tailor's label sewed inside a pocket of his coat. The victim is Colonel Eversley Marcom, a wealthy and socially prominent resident of Batavia, N.Y., who is registered at the Conradi-Windermere.

"Inspector Scofield has taken personal charge of the case. Unfortunately the police have but little to go on. Hugh J. Marcom, son of the deceased, says that he and his father were supping with some men friends at the Club Splendide last night, when the elder Marcom was called to the telephone. This was about one-thirty. He never returned to his friends. As this had happened before they thought nothing of it until the tragedy was revealed some hours later. Colonel Marcom carried a large sum of money on his person.

"Hugh J. Marcom has offered a reward of five thousand dollars for the apprehension of his father's murderers."

Edda lit a cigarette and went into a study. Foolhardy to try to tell her story to the police without corroboration. Must dig up corroboration. Five thousand dollars! Oh, boy! it was worth fighting for. Five thousand dollars! It seemed to be emblazoned all around the walls; dollar sign, five and three naughts! And she was closer to it than anybody else—except possibly Raymondo. The proprietor would be sore. Would he denounce Jack Scanlan for the sake of the reward? How could he after he had taken a hand in the disposal of the body? No, Raymondo would keep his mouth shut and seek a private revenge. She, Edda, had a clear field.

Her next requirement was clothes. From a bell-boy she learned that there was a dress shop in the hotel, and sent him to ask the manageress to come to her room. Guests of the Conradi-Windermere were expected to take a high hand with tradespeople. In due course the woman appeared; handsome, elegant, Broadway-wise. Edda had a hunch that frankness was the line to take with this one. She said:

"I couldn't come down to your shop because I have nothing to appear in but an evening dress. I have a chance of swinging a five thousand dollar deal today if I can get some clothes." She paused with her nicest smile, but it was deflected by the woman's glassy front. The manageress simply waited.

"You must have had a lot of experience," Edda went on, "or you wouldn't be where you are. I need a smart costume suitable for a business woman calling on men. Look me over. Do you care to take a chance on me?"

The woman was startled into an almost human look. "How did you land here without any clothes?" she asked. "I can't tell you the truth and I won't lie to you," said Edda. "I reckon you know that a lone woman is often up against it, though they have given us the vote."

The manageress rubbed her lip, and studied Edda lying in the bed. "I never had a proposition of this sort put up to me before," she said with a dry smile. She asked a number of questions. Finally she said: "You have the look of a winner to me. I'll take the chance."

Edda felt the color flooding her cheeks. "Here's where I ought to kiss your hand," she said, "but I'll let you off. You won't be sorry for giving me a leg up."

AN hour later Edda was entering the old flat-house on East Forty-ninth Street. In the meantime she had visited a second-hand store where she had exchanged her evening outfit for a gun, a pair of handcuffs and a small sum in cash. Every time she opened her handbag the sight of the gun made her feel a little sickish. She hoped she would be able to use it if it came to such a point. She jollied herself along.

Edda the death-dealing sleuth! Edda eats-'em-alive. Am I afraid of man, woman or crook-fingered Jack? Not on your passe-partout!

This morning there was another woman sitting at the desk in the furnished flat-house. It made things easier. An old woman with a bunch of frizzes and a mouth that drew up like walrus hide. "Have you any vacant flats?" Edda asked her. "Nothing that would suit you," said the old woman morosely. Edda realized that she was too well turned out for east of Lexington. "Well, anyway, show me what you've got," she said cajolingly.

"Who sent you to me?"

"I met some people the other night who mentioned that they lived here. Name of Scanlan."

The landlady's mouth relaxed some. "Oh, the Scanlans. Nice people."

They have paid up, thought Edda. Aloud she said casually: "Do they happen to be in now?"

"Left last night," said the landlady. "I didn't see them, but my sister told me. They got a joint engagement in Chicago. Left in a hurry because they had a chance to motor out with friends." Sounds like one of Maud's artistic touches, thought Edda.

"Then their flat is vacant," she said brightly. "Can I see that?"

"It's in a state," said the landlady. "Not fit to show."

"I'll overlook the state," said Edda. "They said it was a nice flat."

They climbed the stairs, and once more Edda found herself in the little sitting-room with the grimy, frilled pillows. It looked now as if a twister blown through. A big trunk had been brought in, and a sluttish maid was pitching the Scanlan's personal belongings into it.

"They could only take their satchels in the car," said the landlady; "so my sister said she'd pack their trunks and hold until sent for."

Edda would have given something pretty to search the trunk, but it seemed hopeless. The maid could have been bribed but there was no way of getting rid of the landlady. Suspicion runs in landladies' veins.

"Nice bright outlook," said Edda, stalling for time.

"Im-hym," said the landlady. She pointed out all the advantages. The maid swept up a mess of letters and papers on the desk and threw them in the trunk. Edda saw her chance.

"Oh, don't do that!" she said. She gathered the papers out of the trunk and arranged them neatly on the desk. "Pardon me," she said, smiling at the two staring women, "but I'm just naturally a tidy person!"

Meanwhile she was looking at as many papers as she could. The billhead of a hotel caught her eye, and in snapping an elastic band around the bunch, she contrived to let that fall.

"You dropped one," said the landlady acidly.

Edda got a good look at it. "Just a hotel receipt," she said, slipping it under the band. "Hotel McArthur."

The landlady sniffed. "When they had money my house wasn't good enough for them! Maud Scanlan would never let you forget she had stopped at the McArthur. Her idea of heaven!"... She suddenly turned on the maid. "You pack that trunk tidy, girl, or out you go!"

She led Edda into the bedroom and enlarged on its virtues. A clean sweep had been made here. Edda, seeing that nothing more was to be got, said: "Well, I'll let you know." And smiled her way out.

SHE took a taxi to the McArthur. Jack Scanlan had let fall that he considered a big New York hotel the safest of all hiding places, and now she knew the name of the hotel they favored. It was a good deal. But her heart sank when she saw the size of the place. Until the Conradi-Windermere was built the McArthur had advertised itself as the biggest hotel in the world. Like looking for a flea in old Shep, thought Edda.

However she marched up to the desk and turned on the Manby smile for the gentlemanly clerk. "I represent the..." she said, naming the smartest of the society monthlies. "Do you mind if I look over your arrivals today? We like to keep tab."

The clerk didn't mind. He produced the cards for all the arrivals since midnight. There was a column for the hour of arrival filled in with certain hieroglyphic signs which Edda in her innocent way got the clerk to explain. Thus she learned that between the hours of three and five a.m. in addition to singles, three couples had registered at the McArthur. She made a note of the room numbers.

Cutting short the insinuating conversation of the clerk with an imbecile smile, Edda made her way out. Passing around by the street to another entrance, she reached the elevators without passing the desk.

The highest number on her list was 1927 and she commenced with that. On each floor of the McArthur there was a telephone switchboard opposite the elevators, served by a girl who kept an eye on all who came and went. Edda soon satisfied the girl on the nineteenth floor that they belonged to the same lodge.

"There's a couple registered in 27 name of Jackson," she said. "I'm wondering if they're the Jacksons I know."

"He's a dark-complected guy with foxy eyes," was the answer. "Fresh. He give me half-a-dollar tip and I noticed he had a finger bent in a funny way. Like this, see?"

Edda's heart began to beat fast; then faster and faster. She silently cursed it for failing her.

"As for the dame, she ain't showed herself since I come on," the switchboard girl went on.... "Look! Somebody coming out of 27 now," she added, glancing down the hall. "Here she is."

Edda did not look. "Much obliged," she said, and walked away slowly in the other direction. She turned a corner of the corridor, waited, then came back to the elevators. The coast was clear.

"It's them all right," she said to the switchboard girl, "but he's my friend, you understand."

"Sure," said the other girl. "These wives!"

Edda walked on toward the door of 1927. Within a space of about six feet she had to decide what to do. Call the police? Jack might get out before they came. And anyhow if the police took him they would expect to horn in on the reward. Five thousand dollars on the other side of that door! She couldn't take any chances on losing it.

Her heart was beating like a bird in a net. Without giving herself any further time to think, she knocked on the door in a certain way; knock, pause, three knocks, pause, knock. Here's where I do a Sarah Bernhardt! she thought, gasping a little.

A key turned in the lock, and a surly voice said: "Come in."

As she entered, Jack was walking away toward the bathroom. He was in pajamas and dressing-gown, and her heart eased up a little; not armed! She softly closed the door.

"What the hell!" he growled without looking around. "Can't you go out without you forget something?"

"Jack!" she said softly.

He turned, showing a face gone clownish with surprise. Half of it was covered with shaving lather.

"Edda! For God's sake!" he said.

Quick! Don't give him time to think! she thought. She started blubbering realistically. "Oh, Jack, help me! Help me! I've got no money, no place to go! What am I going to do, Jack? You can't turn me off like this!"

"Where did you get those clothes?" he demanded suspiciously.

"Borrowed them from a friend. She can't do any more for me. You got to help me, Jack! I got nobody to go to! I got to have money!"

Gradually the suspicious look gave place to a wicked grin. He picked up a towel and wiped the soap off his face. He came toward her. In the morning sunlight he looked terrible. He put his arms around her. "There, little girl, that's all right," he purred. "Sure I'll take care of you! Leave everything to me."

EDDA let him run on while she planned out what to do. All thoughts of using the gun had fled. Suppose she missed; suppose the gun wouldn't fire; suppose Jack managed to get it away from her? She couldn't even remember ever having held a gun before. Her glance was arrested by a painted steampipe which ran from floor to ceiling in the corner of the room. That was what she needed! She wriggled out of his embrace.

"Oh, don't!" she said, retreating toward the steampipe. "It isn't right, Jack!"

"A-ah! What the hell!" he snarled, turning ugly. "Crying, and begging for money one minute, and push me off the next! What do you think a man is?"

"What would Maud say?" she faltered.

"Maud won't be back for hours."

Edda made believe to relent. "Don't be cross with me, Jack."

Jack followed her up, and put his arms around her again. "Cheese! You're a lovely armful!" he murmured. "There's more to you than a man would think! I'm just crazy about you, Slant-eyes!"

Edda pressed back a little, bringing him immediately alongside the steampipe. Her arms were hanging straight down. She planned out every move in advance. Open the bag... take out handcuffs... let bag drop... kick it away... both sides of the handcuffs are open... bring up your right hand slowly... snap it around his wrist... then quick! shove his arm back and snap the other side around the pipe!

Click! It was done! She tore herself out of his arms. He plunged after her and was brought up with a jerk that almost tore his arm out at the shoulder. Edda backed out of his reach, and sat down on the nearest bed shaking like a top-heavy jelly mold. Am I going to faint? She asked herself. I will not! I will not! The man's face was like a snarling jackal's that she had seen pictured somewhere. He jerked viciously at his fetter, cursing Edda in a manner that made the skin at the back of her neck prickle. However, the color came back into her face, and her back stiffened. She faced him out.

He can't pull the pipe down, she thought; and handcuffs are made to hold a man. He's no Samson anyhow. Let him curse! She slung her feet over to the other side of the bed. The telephone was on a stand between the twin beds. She looked up her number in the book and gave it. "Why... why..." returned a frightened voice over the wire, "that's police headquarters!"

"Make it snappy, girl!" said Edda, "I want Inspector Scofield."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.