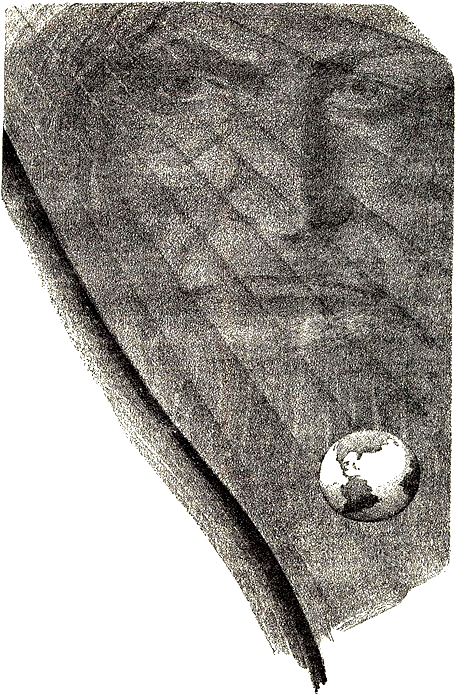

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

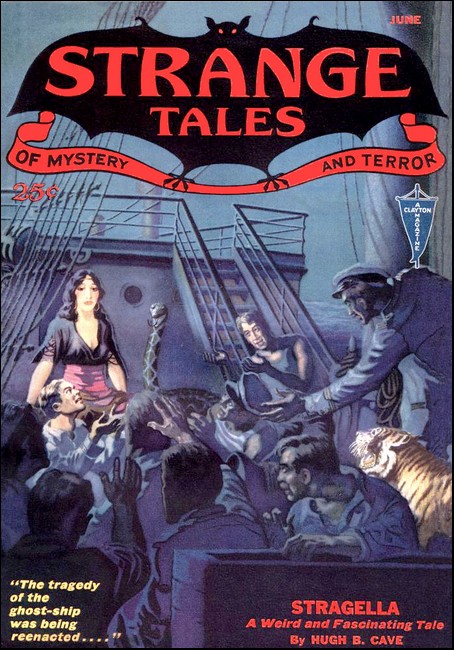

Strange Tales, June 1932, with "The Great Circle"

Canevin crosses the "bridge" that is a

sinister English ash in Quintana Roo.

...A face of colossal majesty emerging there.

THE transition from those hours-on-end of looking down on the dark-green jungle of virgin forest was startling in its abruptness. We had observed this one break in the monotonous terrain, of course, well before we were directly over it. Then Wilkes, the pilot, slowed and began to circle. I think he felt it, the element I have referred to as startling; for, even from the first—before we landed, I mean—there was something—an atmosphere—of strangeness about this vast circular space entirely bare of trees with the exception of the giant which crowned the very slight elevation at its exact center.

I know at any rate that I felt it; and Dr. Pelletier told me afterward that it had seemed to lay hold on him like a quite definite physical sensation. Wilkes did not circle very long. There was no need for it and I think he continued the process, as though looking for a landing place, as long as he did, on account of that eeriness rather than because of any necessity for prolonged observation.

At last, almost, I thought, as though reluctantly, he shut off his engine—'cut his gun' as airmen express it—and brought the plane down to an easy landing on the level greensward within a hundred yards of the great tree standing there in its majestic, lonely grandeur. The great circular space about it was like a billiard table, like an English deer park. The great tree looked, too, for all the world like an ash, itself an anomaly here in the uncharted wilderness of Quintana Roo.

We sat there in the plane and looked about us. On every side, for a radius of more than half a mile from the center where we were, the level grassy plain stretched away in every direction and down an almost imperceptible gradual slope to the horizon of dense forest which encircled it.

There was not a breath of air stirring. No blade of the fine short grass moved. The tree, dominating everything, its foliage equally motionless, drew our gaze. We all looked at it at the same time. It was Wilkes the pilot who spoke first, his outstretched arm indicating the tree.

'Might be a thousand years old!' said Wilkes, in a hushed voice. There was something about this place which made all of us, I think, lower our voices.

'Or even two thousand,' remarked Pelletier.

WE had taken off that morning at ten from Belize. It was now one o'clock in the afternoon. We had flown due north for the first eighty miles or so, first over the blue waters of landlocked Chetumal Bay, leaving Ambergris Cay on our right, and then Xkalok, the south-eastern point of Quintana Roo; then over dry land, leaving the constricted northern point of the bay behind where parallel 19, north latitude, crosses the 88th meridian of longitude. Thence still due north until we had turned west at Santa Cruz de Bravo, and continued in that direction, glimpsing the hard, metallic luster of the noon sun on Lake Chinahaucanab, and then, veering southwest in the direction of Xkanba and skirting a tremendous wooden plateau on our left, we had been attracted, after cursory, down-looking views of innumerable architectural remains among the dense forestation, to our landing place by the abrupt conspicuousness of its treeless circularity.

That summarizes the geography of our flight. Our object, the general interest of the outlook rather than anything definitely scientific, was occasioned by Pelletier's vacation, as per the regulations of the U. S. Navy, of whose Medical Corps he is one of the chief ornaments, from his duties as Chief of the Naval Hospital in St. Thomas, Virgin Islands. Pelletier wanted to get over to Central America for this vacation. He talked it over with me several times on the cool gallery of my house on Denmark Hill. Almost incidentally he asked me to accompany him. I think he knew that I would come along.

We started, through San Juan, Porto Rico, in which great port we found accommodation in the Bull Line's Catherine with our friend Captain Rumberg, who is a Finn, as far as Santo Domingo City. From there we trekked, across the lofty intervening mountains, with a guide and pack burros, into Haiti. At Port au Prince we secured accommodations as the sole passengers on a tramp going to Belize in British Honduras, which made only one stop, at Kingston, Jamaica.

IT was between Kingston and Belize that the idea of this air voyage occurred to Pelletier. The idea of looking down comfortably upon the Maya remains, those cities buried in impenetrable jungles, grew upon him and he waxed eloquent out of what proved an encyclopedic fund of knowledge of Maya history. I learned more about these antiquities than I had acquired in my entire life previously! One aspect of that rather mysterious history, it seemed, had intrigued Pelletier. This was the abrupt and unaccountable disappearance of what he called the earliest of major civilizations. The superior race which had built the innumerable temples, palaces and other elaborate and ornate structures now slowly decaying in the jungles of the Yucatan Peninsula, had been, apparently, wiped out in a very brief period. They had, it seemed, merely disappeared. Science, said Pelletier, had been unable to account for this catastrophe. I had, of course, read of it before, but Pelletier's enthusiasm made it vastly intriguing.

Our two-men-and-hired-pilot expedition into this unexplored region of vast architectural ruins and endless forestation had landed, as though by the merest chance, here in a section presenting topographical features such as no previous explorers had reported upon! We were, perhaps, two hours by air, from Belize and civilization—two months, at least, had we been traveling afoot through the thick jungles, however well equipped with food, guides, and the machetes which all previous adventurers into the Yucatan jungles report as the first essential for such travel.

Pelletier, with those small verbal creakings and gruntings which invariably punctuate the shifting of position in his case, was the first to move. He heaved his ungainly bulk laboriously out of the plane and stood on the grassy level ground looking up at Wilkes and me. The sun beat down pitilessly on the three of us. His first remark was entirely practical.

'Let's get into the shade of that tree, and eat,' said Dr. Pelletier.

TEN minutes later we had the lunch basket unpacked, the lunch spread out, and were starting to eat, there in the heart of Quintana Roo. And, to all appearances, we might have been sitting down picnicking in Kent, or Connecticut!

I remember, with a vivid clarity which is burned indelibly into my mind, Wilkes reaching for a tongue-sandwich, when the wind came.

Abruptly, without any warning, it came, a sudden, violent gust out of nowhere, like an unexpected blow from behind, upsetting our peaceful little session there, sociably, on the grass in the quiet shade of the ancient tree which looked like an English ash. It shredded to filaments the paper napkin I was holding. It caused the squat mustard bottle to land twenty feet away. It sucked dry the brine out of the saucerful of stuffed olives. It sent Pelletier lumbering after a rapidly rolling pith sun-helmet. And it carried the pilot Wilkes's somewhat soiled and grimy Shantung silk jacket—which he had doubled up and was using to sit on, and had released by virtue of half rising to reach for that tongue sandwich—and blew it, fluttering, folding and unfolding, arms now stiffly extended, now rolled up into a close ball, up, off the ground, and then, in a curve upward and flattened out and into the tree's lower branches, and then straight up among these, out of our sight.

Having accomplished all these things, and scattered items of lunch broadcast, the sudden wind died a natural death, and everything was precisely as it had been before, save for the disorganization of our lunch—and save, too, for us!

I WILL not attempt to depart from the strict truth: we were, all of us, quite definitely startled. Wilkes swore picturesquely at the disappearance of his jacket, and continued to reach, with a kind of baffled ineptitude which was quite definitely comic, after the now scattered tongue sandwiches. Pelletier, returning with the rescued sun helmet, wore a vastly puzzled expression on his heavy face, much like an injured child who does not know quite what has happened to him. As for me, I dare say I presented an equally absurd appearance. That gust had caught me as I was pouring limeade from a quart thermos into three of those half-pint paper cups which are so difficult to manage as soon as filled. I found myself now gazing ruefully at the plate of cold sliced ham, inundated with the cup's contents.

Pelletier sat down again in the place he had vacated a moment before, turned to me, and remarked: 'Now where did that come from?'

I shook my head. I had no answer to that. I was wondering myself. It was Wilkes who answered, Wilkes goaded to a high pitch of annoyance over the jacket, Wilkes unaware of the singular appropriateness of his reply.

'Right out of the corner of hell!' said Wilkes, rather sourly, as he rose to walk over to that enormous trunk and to look up into the branches, seeking vainly for some glimpse of Shantung silk with motor grease on it.

'Hm!' remarked Pelletier, as he bit, reflectively, into one of the sandwiches. I said nothing. I was trying at the moment to divide what was left of the cold limeade evenly among three half-pint paper cups.

IT was nearly a full hour later, after we had eaten heartily and cleared up the remains of the lunch, and smoked, that Wilkes prepared to climb the tree. I know because I looked at my watch. It was two fourteen—another fact burned into my brain; I was estimating when, starting then, we should get back to Belize, where I had a dinner engagement at seven. I thought about five or five-fifteen.

'The damned thing is up there somewhere,' said Wilkes, looking up into the branches and leaves. 'It certainly hasn't come down. I suppose I'll have to go up after it!'

I gave him a pair of hands up, his foot on them and a quick heave, a lower limb deftly caught, an overhand pull; and then our Belize pilot was climbing like a cat up into the great tree's heart after his elusive and badly soiled garment.

The repacked lunch basket had to be put in the plane, some hundred yards away from the tree. I attended to that while Pelletier busied himself with his notebook, sitting cross-legged in the shade.

I sauntered back after disposing of the lunch basket. I glanced over at the tree, expecting to see Wilkes descending about then with the rescued jacket. He was still up there, however. There was nothing to take note of except a slight—a very slight—movement of the leaves, which, looking up the tree and seeing, I remarked as unusual because not a single breath of air was stirring anywhere. I recall thinking, whimsically, that it was as though the great tree were laughing at us, very quietly and softly, over the trouble it was making for Wilkes.

I sat down beside Pelletier, and he began to speak, perhaps for the third or fourth time, about that strange clap of wind. That had made a very powerful impression on Pelletier, it seemed. After this comment Pelletier paused, frowned, looked at his watch and then at the tree, and remarked: 'Where is that fellow? He's been up there ten minutes!' We walked over to the tree's foot and looked up among the branches. The great tree stood there inscrutable, a faint movement barely perceptible among its leaves. I remembered that imagined note of derision which this delicate movement had suggested to me, and I smiled to myself.

Pelletier shouted up the tree: 'Wilkes! Wilkes—can't you find the coat?'

Then again: 'Wilkes! Wilkes—we've got to get started back pretty soon!'

But there was no answer from Wilkes, only that almost imperceptible movement of the leaves, as though there were a little breeze up there; as though indeed the tree were quietly laughing at us. And there was something—something remotely sinister, derisive, like a sneer, in that small, dry, rustling chuckle.

PELLETIER and I looked at each other, and there was no smile in the eyes of either one of us.

We sat down on the grass then as though by agreement. Again we looked at each other. I seemed to feel the tree's derision; more openly now, less like a delicate hint, a nuance. It seemed to me quite open now, like a slap in the face! Here indeed was an unprecedented predicament. We were all ready to depart, and we had no pilot. Our pilot had merely performed a commonplace act. He had climbed a tree.

But—he had not come down—that was all.

It seemed simple to state it to oneself that way, as I did, to myself. And yet, the implications of that simple statement involved—well, what did they involve? The thing, barring an accident: Wilkes having fallen into a decay-cavity or something of the sort; or a joke: Wilkes hiding from us like a child among the upper branches—barring those explanations for his continued absence up there and his refusal to answer when called to, the thing was—well, impossible.

Wilkes was a grown man. It was inconceivable that he should be hiding from us up there. If caught, somehow, and so deterred from descending, at least he could have replied to Pelletier's hail, explained his possible predicament. He had, too, gone far up into the tree. I had seen him go up agilely after my initial helping hand. He was, indeed, well up and going higher far above the lower trunk area of possible decay-cavities, when I had left him to put the lunch basket back in the plane. He had been up nearly twenty minutes now, and had not come down. We could not see him. A slightly cold sensation up and down my spine came like a presage, a warning. There seemed—it was borne in abruptly upon me—something sinister here, something menacing, deadly. I looked over at Pelletier to see if anything of this feeling might be reflected in his expression, and as I looked, he spoke.

'Canevin, did you notice that this deforested area is circular?'

I nodded.

'Does that suggest anything to you?'

I paused, took thought. It suggested several things, in the light of my recent, my current, feeling about this place centered about its great tree. It was, for one thing, apparently an unique formation in the topography of this peninsula. The circularity suggested an area set off from the rest, and by design—somebody's design. The 'ring' idea next came uppermost in my mind. The ring plays a large part in the occult, the preternatural: the elves' ring; dancing rings (they were grassy places, too); the Norman cromlechs; Stonehenge; the Druidical rites; protective rings, beyond the perimeter of which the Powers of Evil, beleaguering, might not penetrate... I looked up from these thoughts again at Pelletier.

'Good God, Pelletier! Yes—do you imagine...?'

Pelletier waved one of his big, awkward-looking hands, those hands which so often skirted death, defeated death, at his operating table.

'It's significant,' he muttered, and nodded his head several times. Then: 'That gust of wind, Canevin—remember? It was that which took Wilkes's coat up there, made him climb after it; and now—well, where is he?'

I shook my head slowly. There seemed no answer to Pelletier's question. Then: 'What is it, Pelletier?'

Pelletier replied, as was usual with him, only after some additional reflection and with a certain deliberateness. He was measuring every word, it seemed.

'Every indication, so far, points to—an air-elemental.'

'An air-elemental?' The term, with whatever idea or spiritual entity, or vague, unusual superstition underlay its possible meaning, was familiar to me, but who—except Pelletier, whose range of knowledge I certainly had never plumbed—would think of such a thing in this connection?

'What is an air-elemental?' I asked him, hoping for some higher information.

PELLETIER waved his hand in a gesture common to him.

'It would be a little difficult to make it clear, right off the bat, so to speak, Canevin,' said he, a heavy frown engendered by his own inability to express what might be in that strange, full mind of his, corrugating his broad forehead. 'And even if I had it at my tongue's end,' he continued, 'it would take an unconscionable time.' He paused and looked at me, smiling wryly.

'I'll tell you, Canevin, all about them, if we ever get the chance.' Then, as I nodded, necessarily acquiescing in this unsatisfactory explanation, he added: 'That is, what little, what very little, I, or indeed anybody, knows about them!'

And with that I had, perforce, to be satisfied.

It seemed to my taunted senses, attuned now to this suggested atmosphere of menace which I was beginning to sense all about us, that an intensified rustle came from the tree's leaves. An involuntary shudder ran over my body. From that moment, quite definitely, I felt it: the certain, unmistakable knowledge that we three stood alone, encircled, hemmed in, by something; something vast, powerful beyond all comprehension, like the incalculable power of a god, or a demigod; something elemental and, I felt, old with a hoary antiquity; something established here from beyond the ken of humanity; something utterly inhuman, overwhelmingly hostile, inimical, to us. I felt that we were on Its ground, and that It had, so far, merely shown us, contemptuously, the outer edge of Its malice and of Its power. It had, quietly, unobtrusively, taken Wilkes. Now, biding Its time, It was watching, as though amused; certain of Its malignant, Its overwhelming, power; watching us, waiting for Its own good time to close in on us...

I STOOD up, to break the strain, and walked a few steps toward the edge of the tree's nearly circular shade. From there I looked down that gentle slope across the motionless short grass through the shimmering heat waves of that airless afternoon to the tree-horizon.

What was that? I shaded my hands and strained my vision through those pulsating heat waves which intervened; then, astonished, incredulous, I ran over to the plane and reached in over the side and brought out the high-powered Lomb-Zeiss binoculars which Bishop Dunn at Belize had loaned me the evening before. I put them to my eyes without waiting to go back into the shade near Pelletier. I wanted to test, to verify, what I thought I had seen down there at the edge of the encircling forest; to assure myself at the same time that I was still sane.

There at the jungle's edge, clear and distinct now, as I focused those admirable binoculars, I saw, milling about, crowding upon each other, gesticulating wildly—shouting, too, soundlessly of course, at that distance from my ears—evidencing in short the very apogee of extreme agitation; swarming in their hundreds—their thousands, indeed—a countless horde of those dull-witted brown Indians, still named Mayas, some four hundred thousand of which constitute the native population of the Peninsula of Yucatan—Yucatan province, Campeche, and Quintana Roo.

All of them, apparently, were concentrated, pointing, gesticulating, upon the center of the great circle of grassland, upon the giant tree—upon us.

And, as I looked, shifting my glasses along great arcs and sections of the jungle-edged circle, fascinated by this wholly bizarre configuration, abruptly, with a kind of cold chill of conviction, I suddenly perceived that, despite their manifest agitation, which was positively violent, all those excited Indians were keeping themselves rigidly within the shelter of the woods. Not one stepped so much as his foot over that line which demarcated the forested perimeter of the circle, upon that short grass.

I LOWERED the glasses at last and walked back to Pelletier. He had not moved. He raised to me a very serious face as I approached.

'What did you see down there, Canevin?' He indicated the distant rim of trees.

He listened to my account as thought preoccupied, nodding from time to time. He only became outwardly attentive when I mentioned how the Indians kept back to the line of trees. He allowed a brief, explosive 'Ha!' to escape him when I got to that.

When I had finished: 'Canevin,' said he, gravely, 'we are in a very tight place.' He looked up at me still gravely, as though to ascertain whether or not I realized the situation he had in mind. I nodded, glanced at my watch.

'Yes,' said I, 'I realize that, of course. It is five minutes to three. Wilkes has been gone up there, three-quarters of an hour. That's one thing, explain it as you may. Neither of us can pilot a plane; and, even if we were able to do so, Pelletier, we couldn't, naturally, go back to Belize without Wilkes. We couldn't account for his disappearance: "Yes, Mr. Commissioner, he went up a tree and never came down!" We should be taken for idiots, or murderers! Then there's that—er—horde of Indians, surrounding us. We are hemmed in, Pelletier, and there are, I'd say, thousands of them. The moment they make up their minds to rush us—well, we're finished, Pelletier,' I ended these remarks and found myself glancing apprehensively toward the rim of jungle.

'Right enough, so far!' said Pelletier, grimly. 'We're "hemmed in," as you put it, Canevin, only perhaps a little differently from the way you mean. Those Indians'—his long arm swept our horizon—'will never attack us. Put that quite out of your mind, my dear fellow. Except for the fact that there's probably only food enough left for one scant meal, you've summed up the—er—material difficulties. However—'

I interrupted.

'That mob, Pelletier, I tell you, there are thousands of them. Why should they surround us if—'

'They won't attack us. It isn't us they're surrounding, even though our being here is, in a way, the occasion for their assembly down there. They aren't in any mood to attack anybody, Canevin —they're frightened.'

'Frightened?' I barked out. 'Frightened! About what, for God's sake?' This idea seemed to me so utterly far-fetched, so intrinsically absurd, at first hearing—after all, it was I who had watched them through the binoculars, not Pelletier who sat here so calmly and assured me of what seemed a basic improbability. 'It doesn't seem to make sense to me, Pelletier,' I continued. 'And besides, you spoke just now of the "material" difficulties. What others are there?'

PELLETIER looked at me for quite a long time before answering, a period long enough for me to recapitulate those eerier matters which I had lost sight of in what seemed the imminent danger from those massed Indians. Then: 'Where do you imagine Wilkes is?' inquired Pelletier. 'Can you—er—see him up there?' He pointed over his shoulder with his thumb, as artists and surgeons point.

'Good God, Pelletier, you don't mean...?'

'Take a good look up into the tree,' said Pelletier, calmly. 'Shout up to him; see if he answers now. You heard me do it. Wilkes isn't deaf!'

I stood and looked at my friend sitting there on the grass, his ungainly bulk sprawled awkwardly. I said nothing. I confess to a whole series of prickly small chills up and down my spine. At last I went over close to the enormous bole and looked up. I called: 'Wilkes! Oh Wilkes!' at the top of my voice, several times. I desisted just in time, I think, to keep an hysterical note out of that stentorian shouting.

For no human voice had answered from up there—only, as it seemed to me, a now clearly derisive rustle, a kind of thin cacophony, from those damnable fluttering leaves which moved without wind. Not a breath stirred anywhere. To that I can take oath. Yet those leaves...

THE sweat induced by my slight exertions even in the tree's shade, ran cold off my forehead into my eyes; down my body inside my white drill clothes. I had seen no trace of Wilkes in the tree, and yet the tree's foliage for all its huge bulk was not so dense as to prevent seeing up into every part of it. Wilkes had been up there now for nearly an hour. It was as though he had disappeared from off the face of the earth. I knew now, clearly, what Pelletier had had in mind when he distinguished between our 'material' and other difficulties. I walked slowly back to him.

Pelletier had a somber look on his face.

'Did you see him?' he asked. 'Did he answer you?' But, it seemed, these were only rhetorical questions. Pelletier did not pause for any reply from me. Instead, he proceeded to ask more questions.

'Did you see any ants on the trunk? You were quite close to it.' Then, not pausing: 'Have you been troubled by any insects since we came down here, Canevin? Notice any at lunch, or when you took the lunch basket back to the plane?' Finally, with a sweeping, upward gesture: 'Do you see any birds, Canevin?'

I shook my head in one composite reply to these questions. I had noticed no ants or any other insects. No bird was in flight. I could not recall, now that my attention had been drawn to the fact, seeing any living thing here besides ourselves. Pelletier broke in upon this momentary meditation.

'The place is tabu, Canevin, and not only to those Indians down there in the trees—to everything living, man!—to the very birds, to the ground game, to the insects!' He lowered his voice suddenly to a deep significant resonance which was purely tragic.

'Canevin, this is a theater of very ancient Evil,' said Dr. Pelletier, 'and we have intruded upon it.'

AFTER that blunt statement, coming as it did from a man like Dr. Pelletier, I felt, strange as it seems, better. That may appear the reverse of reason; yet, it is strictly, utterly true. For, after that, I knew where we stood. Those eery sensations which I have mentioned, and which I had well-nigh forgotten in the face of the supposed danger from that massed horde of semi-savages in the forest, crystallized now into the certainty that we stood confronted with some malign menace, not human, not of this world, something not to be gaged or measured by everyday standards of safety. And when I, Gerald Canevin, know where I stand in anything like a pinch, when I know to what I am opposed, when all doubt, in other words, is removed, I act!

But first I wanted to know rather more about what Pelletier had in that experienced head of his; Pelletier, who had looked all kinds of danger in the face in China, in Haiti, in this same Central American territory, in many other sections of the world.

'Tell me what you think it is, Pelletier,' I said, quietly, and stood there waiting for him to begin. He did not keep me waiting.

'Before Harvey discovered the circulation of the blood, Canevin, and so set anatomy on the road to its present modern status, the older anatomists said that the human body contained four humours. Do you remember that? They were called the Melancholic, the Sanguine, the Phlegmatic, and the Choleric Humours—imaginary fluids! These, or the supposed combination of them, in various proportions, were supposed to determine the state and disposition of the medical patient. That was "science"—in the days of Nicholas Culpepper, Canevin! Now, in the days of the Mayo Brothers, that sort of thing is merely archaic, historical, something to smile at! But, never forget, Canevin, it was modern science—once! And, notice how basically true it is! Even though there are no such definite fluids in the human body—speculative science it was, you know, not empirical, not based on observation like ours of today, not experimental—just notice how those four do actually correspond to the various human temperaments. We still say such-and-such a person is "sanguine" or "phlegmatic," or even "choleric"! We attribute a lot of temperament today to the ductless glands with their equally obscure fluids; and, Canevin, one is just about as close to the truth as the other!

'NOW, an analogy! I reminded you of that old anatomy to compare it with something else. Long before modern natural science came into its own, the old-timers, Copernicus, Duns Scotus, Bacon, the scientists of their day, even Ptolemy, had their four elements: air, earth, water and fire. Those four are still elements, Canevin. The main difference between now and then is the so-called "elemental" behind each of them—a thing with intelligence, Canevin, a kind of demigod. It goes back, that idea, to the Gnostics of the second and third centuries; and the Gnostics went back for the origins of such speculations to the once modern science of Alexandria; of Sumer and Accad; to Egypt, to Phrygia, to Pontus and Commagene! That gust of wind, Canevin—do you—'

'You think,' I interrupted, 'that an air-elemental is...?'

'What more probable, Canevin? Or, what the ancients meant by an air-elemental, a directing intelligence, let us say. You wouldn't attribute all this, Wilkes's disappearance, all the rest of it, so far—' Pelletier indicated in one comprehensive gesture the tree, the circle of short grass, even the insectless ground and the birdless air—'to everyday, modern, material causes; to things that Millikan and the rest could classify and measure, and compute about—would you, Canevin?'

I shook my head.

'I'm going up that tree after Wilkes,' I said, and dropped my drill coat on the grass beside Pelletier. I laid my own sun-helmet on the ground beside him. I tightened my belt a hole. Then I started for the tree. I expected some sort of protest or warning from Pelletier. He merely said: 'Wilkes got caught, somehow, up there, because he was taken off his guard, I should surmise. You know, more or less, what to expect!'

I did not know what to expect, but I was quite sure there would be something, up there. I was prepared. This was not the first time Gerald Canevin had been called upon to face the Powers of Darkness, the preternatural. I sent up a brief and fervent prayer to the Author of this universe, to Him Who made all things, 'visible and invisible' as the Nicene Creed expresses it. He, Their Author, was more powerful than They. If He were on my side...

I jumped for the limb up to which I had boosted Wilkes, caught it, got both hands around it, hauled myself up, and then, taking a deep breath, I started up among those still dryly rustling leaves in an atmosphere of deep and heavy shade where no breath of air moved...

I PERCEIVE clearly enough that in case this account of what happened to Wilkes and Pelletier and me ever has a reader other than myself—and, of course, Pelletier if he should care to peruse what I have set down here; Wilkes, poor fellow, crashed over the Andes, less than three months ago as I write this—I perceive that, although the fore-going portion of this narrative does not wholly transcend ordinary strangeness, yet, that the portion which is now to follow will necessarily appear implausible; will, in other words, strain severely that same hypothetical reader's credulity to the utmost.

For, what I found when I went up the tree after Wilkes—spiritually prepared, in a sense, but without any knowledge of what I might encounter—was—well, it is probable that some two millennia, two thousand years or thereabouts had rolled over the jungles since that background Power has been directly exorcised. And yet, the memory of It had persisted without lapse among those semi-savage inhabitants such as howled and leaped in their agitation down there at the jungle's rim at that very moment; had so persisted for perhaps sixty generations.

I went up, I should estimate, about as far as the exact center of the great tree. Nothing whatever had happened so far. My mind, of course, was at least partly occupied by the purely physical affair of climbing. At about that point in my progress upward among the branches and leaves I paused and looked down. There stood Pelletier, looking up at me, a bulky, lonely figure. My heart went out to him. I could see him, oddly foreshortened, as I looked straight down; his contour somewhat obscured by the intervening foliage and branches. I waved, and called out to him, and Pelletier waved back to me reassuringly, saying nothing. I resumed my climb.

I HAD got myself perhaps some fifteen feet or more higher up the tree—I could see the blue vault above as I looked straight up—when, quite as abruptly as that inexplicable wind-clap which had scattered our lunch, the entire top of the tree began suddenly, yet as though with a sentient deliberation, to constrict itself, to close in on me. The best description of the process I can give is to say that those upper branches, from about the tree's midst upward, suddenly squeezed themselves together. This movement coming up toward me from below, and catching up with me, and pressing me upon all sides, in a kind of vertical peristalsis, pushed me straight upward like a fragment of paste through a collapsible tube!

I slid along the cylinder formed by these upper branches as they yielded and turned themselves upward under the impact of some irresistible pressure. My pace upward under this mechanical compulsion was very rapidly accelerated, and, in much less time than is required to set it down, I flew straight up; almost literally burst out from among the slender topmost twigs and leaves as though propelled through the barrel of some monstrous air-gun; and, once clear of the tree's hindering foliage and twigs, a column of upward-rushing air supporting me, I shot straight up into the blue empyrean.

I COULD feel my senses slipping from my control as the mad pace increased! I closed my eyes against the quick nausea which ensued, and fell into a kind of blank apathy which lasted I know not how long, but out of which I was abruptly snatched with a jar which seemed to wrench every bone and muscle and nerve and sinew in my body.

Unaccountably, as my metabolism slowly readjusted itself, I felt firm support beneath me. I opened my eyes.

I found myself in a sitting position, the wrenching sensations of the jar of landing rapidly dissipating themselves, no feeling of nausea, and, indeed, incongruous as such a word must sound under the circumstances being related, actually comfortable! Whatever substance supported me was comparatively soft and yielding, like thick turf, like a pneumatic cushion. Above me stretched a cloudless sky, the tropical sky of late afternoon, in these accustomed latitudes. Almost automatically I put down my hand to feel what I was resting upon. My eyes, as naturally, followed my hand's motion. My hand encountered something that felt like roughly corrugated rubber, my eyes envisaged a buff-colored ground-surface entirely devoid of vegetation, a surface which, as I turned my head about curiously, stretched away in every direction to an irregular horizon at an immense distance. This ground was not precisely level, as a lawn is level. Yet it showed neither sharp elevations nor any marked depressions. Quite nearby, on my right as I sat there taking in my novel surroundings, two shallow ravines of considerable breadth crossed each other. In one direction, about due south I estimated from the sun's position, three distant, vast, and rounded elevations or hummocks raised themselves against the horizon; and beyond them, dim in the far distance, there appeared to extend farther south vague heights upon four gradually rising plateaus, barely perceptible from where I sat. I was in the approximate center of an enormous plain the lowest point of which, the center of a saucer-like terrain, was my immediate environment; the reverse conformation, so to speak, of the great circle about the tree.

'Good God!' said a voice behind me. 'It's Canevin!'

I TURNED sharply to the one direction my few seconds' scrutiny had failed to include. There, not twenty feet away, sat Wilkes the pilot. He had found his jacket! He was wearing it, in fact. That, queerly enough, was my first mental reaction to having a companion in this weird world to which I had been transported. I noted at that moment, simultaneously with seeing Wilkes, that from somewhere far beneath the surface of the ground there came at regular intervals a kind of throbbing resonance as though from some colossal engine or machine. This pulsing, rhythmical beat was not audible. It came to me—and to Wilkes, as I checked the matter over with him later—through the sense of feeling alone. It continued, I may as well record here, through our entire stay in this world of increasing strangeness.

'I see you have recovered your coat,' said I, as Wilkes rose and stepped toward me.

'No doubt about it!' returned Wilkes, and squared his angular shoulders as though to demonstrate how well the jacket fitted his slender figure.

'And what do you make of—this?' he asked, with a comprehensive gesture including the irregular, vegetationless, buff-colored terrain all about us.

'Are we in the so-called "fourth dimension," or what?'

'Later,' said I, 'if you don't mind, after I get a chance to think a bit. I've just been shot into this place, and I'm not quite oriented!' Then: 'And how did you manage to get yourself up here? I suppose, of course, it's up!'

There is no occasion to repeat here Wilkes's account of his experience in the tree and later. It was identical with mine which I have already described. Of that fact I assured Wilkes as soon as he had ended describing it to me.

'This—er—ground is queer enough,' remarked Wilkes. 'Look at this!'

HE opened his clasp-knife, squatted down, jabbed the knife into the ground half an inch or so, and then cut a long gash in what he had referred to as the 'ground'. In all conscience it was utterly different from anything forming a surface or topsoil that I had ever encountered. Certainly it was not earth as we know it. Wilkes cut another parallel gash, close beside his first incision, drew the two together with his knife at the cut's end, and pried loose and then tore up a long narrow sliver. This, held by one thin end, hung from his hand much as a similarly shaped slice of fresh-cut kitchen linoleum might hang. It looked, indeed, much like linoleum, except that it was both more pliable and also translucent.

'I have another sliver in my pocket,' said Wilkes, handing this fresh one to me. I took the thing and looked at it closely.

'May I see yours?' I asked Wilkes.

Wilkes fished his strip out of a pocket in that soiled silk jacket and handed it to me. He had it rolled up, and it did not unroll easily. I stretched it out between my hands, holding it by both ends. I compared the two specimens. His was considerably dryer than mine, much less pliable. I said nothing. I merely rolled up Wilkes's strip and handed it back to him.

'I've stuck right here,' remarked Wilkes, 'ever since I landed in this Godforsaken place, if it is a place, because, well, because there simply didn't seem to be anything else to do. The sun has been terrific. There's no shade of any kind, you see, not a single spot, as far as you can see; not any at all on the entire damned planet—or whatever it is we've struck! Now that you've "joined up," what say to a trek? I'd agree with anyone who insisted that anything at all beats standing here in one spot! How about it?'

'Right,' I agreed. 'Let's make it either north or south—in the direction of those hummocks, or, up to the top of that plateau region to the south'ard.'

'O.K. with me,' agreed Wilkes. 'Did you, by any blessed chance, bring any water along when you came barging through?'

I had no water, and Wilkes had been here more than an hour in that pitiless glare without any before my arrival. He shook his head ruefully.

'Barring a shower we'll have to grin and bear it, I imagine. Well, let's go. Is it north, or south? I don't care.'

'South, then,' said I, and we started.

OUR way took us directly across one of the intersecting depressions in the ground which I have mentioned. The walking was resilient, the ground's surface neither exactly soft nor precisely hard. It was, I remember thinking, very much like a very coarse crèpe-rubber sole such as is used extensively in tennis and similar sports shoes. As we went down the gradual slope of that ravine the footing changed gradually, the color of underfoot being heightened by an increasingly reddish or pinkish tinge, and the surface becoming smoother as this coloration intensified itself. In places where the more general corrugations almost disappeared, it was so smooth as to shine in the sun's declining rays like something polished. In such stretches as we traversed it was entirely firm, however, and not in the least slippery, as it appeared to be to the eye.

A cool breeze began to blow from the south, in our faces as we walked. This, and a refreshing shower which overtook us about six o'clock, served to revive us just at a point in our journey when we had really begun to suffer from the well-nigh intolerable effects of the broiling sun overhead and the lack of drinking water. The sun's decline put the finishing touch upon our comparative comfort. As for the actual walking, both of us were as tough as pine knots, both salted thoroughly to the tropics, both in the very pink of physical condition. Nevertheless, we felt very grateful for these several reliefs.

The sun went down, this being the month of February, just as we were near the top of the gentle slope which led out of the ravine's farther side. Two miles or so farther along as we continued to trek southward, the stars were out and we were able to keep our course by means of that occasional glance into the heavens which night travelers in the open spaces make automatically.

We pressed on and on, the resilient underfooting favoring our stride, the cool breeze, which grew gradually stronger as we walked into it, blowing refreshingly into our faces. This steady breeze was precisely like the evening trade wind as we know it who live in the Lesser Antilles of the Caribbean.

There was some little talk between us as we proceeded, steadily, due south in the direction of a rising, still distant, mounded tableland, from the summit of which—this had been my original idea in choosing this direction—I thought that we might be enabled to secure a general view of this strange, vegetationless land into which we two had been so singularly precipitated. The tableland, too, was considerably less distant from our starting point than those bolder hummocks to the north which I have mentioned.

From time to time, every couple of miles or so, we sat down and rested for a few minutes.

AT about four in the morning, when we had been walking for more than eleven hours by these easy stages, the ground before us began gradually to rise, and, under the now pouring moonlight, we were able to see that a kind of cleft or valley, running almost exactly north and south, was opening out before us. Along the bottom of this, and up a very gradual rise, we mounted for the next two hours. We estimated that we had gone up several thousand feet from what I might call the mean level of our starting point. For this final stage of our journey, the walking conditions had been especially pleasant. Neither of us was particularly tired.

As we mounted the last of the acclivity, my mind was heavily occupied with Pelletier, left there alone under the tree, with the useless plane nearby and those swarming savages all about him in their great numbers. Also I thought, somewhat ruefully, of my abandoned dinner engagement in Belize. I wondered, in passing, if I should ever sit down to a dinner table again! It seemed, I must admit, rather unlikely just then. Quite likely they would send out some sort of rescue expedition after us; probably another plane following the route which we had placed on file at the airport.

Of such matters, I say, I was thinking, rather than what might be the result, if any, of our all night walk. Just then the abrupt, bright dawn of the tropics broke over at our left in the east. We looked ahead from the summit we had just gained in its blazing, clarifying effulgence, over the crown of the great ridge.

We looked out.

No human being save Wilkes and me, Gerald Canevin, has seen, in modern times at least, what we saw. And, so long as the earth's civilization and science endure, so long as there remains the procession of the equinoxes, so long, indeed, as the galaxy roars its invincible way through unsounded space toward imponderable Hercules, no man born of woman shall ever again see what opened there before our stultified senses, our dazzled eyes...

BEFORE us the ground beyond the great ridge began to slope abruptly downward in one vast, regular curve. It pitched down beyond this parabola in an increasingly steep declivity, such as an ocean might form as it poured its incalculable volume over the edge of the imagined geoplanarian earth-edge of the ancients! Down, down, down to well-nigh the extreme range of our vision it cascaded, down through miles and miles of naked space to a sheer verticalness—a toboggan-slide for Titans.

The surface of this downward-pitching slope, beginning some distance below the level upon which we stood there awestruck, was in one respect different from the land as we had so far seen it. For there, well down that awful slope, we could easily perceive the first vegetation, or what corresponded to vegetation, that we had observed. Down there and extending out of our range of vision for things of that size, there arose from the ground's surface, and growing thicker and more closely together as the eye followed them down, many great columnar structures, irregularly placed with relation to each other, yet of practically uniform height, thickness, and color. This last was a glossy, almost metallic, black. These things were branchless and showed no foliage of any kind. They were narrowed to points at their tops, and these tapering upper portions waved in the strong breeze which blew up from below precisely as the tops of trees moved under the impulse of an earthly breeze. I say 'earthly' advisedly. I will proceed to indicate why!

IT was not, primarily, the inherent majesty of the unique topography which I am attempting to describe which rooted Wilkes and me, appalled, to that spot at the ridge's summit. No. It was the clear sight of our planet, earth, as though seen from an airplane many miles high in the earth's atmosphere, which, in its unexpectedness, caused the sophisticated Wilkes to bury his face in his arms like a frightened child at its mother's lap, caused me to turn my head away. It was the first, demonstrative proof that we had been separated from earth; that we stood, indeed, 'up,' and with a vengeance, miles away from its friendly surface.

It was then, and not before, that the sense of our utter separation, our almost cosmic loneliness, came to us in an almost overwhelming surge of uncontrollable emotion. The morning sun shone clear and bright down there upon our earth, as it shone here where we were so strangely marooned. We saw just there, most prominently presented to our rapt gaze, the northeast section of South America, along the lower edge of our familiar Caribbean, the Guianas, Venezuela, the skirting islands, Margherita, Los Roques, Bonaire, and, a trifle less clear, the lower isles of my own Lesser Antilles: Trinidad, Barbados on the horizon's very edge, the little shadow I knew to be Tobago.

I shall not attempt further to tell here how that unexpected, yet confirmatory sight, shook the two of us; how small and unimportant it made us feel, how cut off from everything that formed our joint backgrounds. Yet, however detached we felt, however stultifying was the vision of earth down there, it was, literally, as nothing, even counting in our conviction of being mere animated, unimportant specks among the soulless particles of space—even that devastating certainty was as nothing to the climactic focus of what we were to behold.

I sat down beside Wilkes, and, speaking low to each other, we managed gradually to recover those shreds of our manhood which had partly escaped us, to get back some of that indomitable courage which sustains the sons of men and makes us, when all is said and done, the ultimate masters of our destinies.

WHEN we were somewhat recovered—readjusted perhaps is the better word—we stood up and once more looked down over the edge of this alien world, down that soul-dizzying slope, our unaided eyes gradually accommodating themselves to seeing more and more clearly its distant reaches and the continentlike section which lay, dim and vague from distance, below it. We observed now what we had failed to perceive before, that the enormous area of that land-pitch was, in its form, roughly rounded, that it sloped to right and left, as well as directly away from us; that it was, in short, a tremendous, slanted column, like a vast circular bridge between the level upon which we then stood and that continentlike mass of territory down below there in the vague distance. As the sun rose higher and higher the fresh breeze died to a trickle of air, then ceased. Those cylindrical, black, tree-like growths no longer waved their spikes. They stood now like rigid metallic columns at variant, irregular angles. In the increasing light the real character of what I had mentally named the Continent below became more nearly apparent. It was changing out of its remote vagueness, taking form. I think it dawned upon me before Wilkes had succeeded in placing what was slowly emerging, mentally. For, just before I turned my head away at the impact of the shock which that dawning realization brought to my mind and senses, the last thing I observed clearly was Wilkes, rigid, gazing below there, staring down that frightful declivity, a mounting horror spreading over the set face above the square-cut jaw...

REALIZATION of the rewards of this world as dross had come, two millennia ago, to Him Who stood beside the Tempter, upon the pinnacles of the Temple, viewing the kingdoms of the world. In some such fashion—if I may so describe the process without any intentional irreverence—there came to me the blasting conviction which then overtook me, forced itself into my protesting mentality, turned all my ideas upside-down.

For it was not a continent that we had been gazing down upon. It was no continent. It was not land—ground. It was a face—a face of such colossal majesty, emerging there, taking form in the rays of the revealing sunlight, as utterly to stagger mind and senses attuned to earthly things, adjusted for a lifetime to earthly proportions; a face ageless in its serene, calm, inhumaneness; its conviction of immeasurable power; its abhuman inscrutability.

I reeled away, my face turned from this incredible catastrophe of thought; and, as I sank down upon the ground, my back turned toward the marge of this declivity, I knew that I had dared to look straight into the countenance of a Great Power, such as the ancients had known. And I realized, suddenly sick at heart, that this presence, too, was looking out of eyes like level, elliptical seas, up into my eyes, deep into my very inmost soul.

But this conviction, so monstrous, so devastating, so incredible, was not all! Along with it there went the heart-shaking realization that what we had visualized as that great slope was the columnar, incredible arm of that cosmic Colossus—that our night-long trek had been made across a portion of the palm of his uplifted hand!

OVERHEAD the cloudless sky began to glow a coppery brown. An ominous, wedge-shaped tinge spread fast, gathering clouds together out of nowhere as it sped into the north. And now the sun-drenched air seemed heavy, of a sudden difficult to breathe under that pitiless, oppressive sun which glared out of the bland, cerulean corner of the sky in which it burned. A menacing sultriness filled the atmosphere, pressed down upon us like a relentless hand. A hand! I shuddered involuntarily, and turned to Wilkes and spoke, my hand on his shoulder. It was a matter of seconds before the stark horror died out of his eyes. He interrupted my almost whispered words.

'Did you see It, Canevin?'

I nodded.

'I think we'll have to get back from the edge,' I repeated my warning he had failed to hear, 'down into that—ravine—again. There's the making of a typhoon up topside, I'm afraid.'

Wilkes shot a quick, weatherwise glance aloft.

'Right-o,' said he, and we started together toward that slight shelter of the shallow valley up which we had toiled as dawn was breaking.

But the wind-storm from out of the north broke upon us long before we had gained this questionable refuge. A blasting hurricane smote down upon us out of that coppery, distorted sky. We had not a chance. The first blast picked us up as though we had been specks of flotsam lint, carried us straight to the brink, and over, and down; and then, side by side, so long as we retained our senses under the stress of that terrific friction, we were hurled at a dizzyingly increasing rate down that titanic toboggan slide as its sheer vertical pitch fell away under our spinning bodies, always faster and faster, with the roar of ten Niagaras rending the very welkin above—down, down, down into the quick oblivion which seemed to shut out all life and all understanding and all persisting hope in one final, mercifully quick-ended horror of ultimate destruction.

Somehow, I carried with me into that disintegration of the senses and ultimate coma, the thought of Pelletier.

IN order to achieve in this strange narrative which I am setting down as best I can, some sense of order and a reasonable brevity, I have, from time to time, summarized my account. I have, for example, mentioned once that engine-like beat, that regular pulsation to be felt here. I have said, to avoid reference to it, that it continued throughout our sojourn in the 'place' which I have described. That is what I mean by summarizing. I have, indeed, omitted much, very much, which, now that I am writing at leisure, I feel would burden my account with needless detail, unnecessary recording of my emotional reaction to what was happening. In this category lies all that long conversation between Wilkes and me, as we strode along, side by side, on that long night walk.

But, of all such matters, the most prominent to me was the preoccupation—a natural one, I believe—with that good friend whom I had left looking up into the tree which looked like an English ash, as I climbed away from him into what neither of us could possibly visualize or anticipate, away, as it transpired, from our very planet earth, and into a setting, a set of conditions, quite utterly diverse from anything the mind of modern man could possibly conceive or invent.

This preoccupation of mine with Pelletier had been virtually continuous. I had never had him wholly out of my mind. He had uttered, it will be remembered, no protest at my leaving him down there alone. That, at the time, had surprised me considerably. But on reflection I came to see that such an attitude on his part was entirely natural. It was part of that tremendous fortitude of his, almost fatalism, which was an integral part of his character. I have known few men better balanced than that ungainly, big-hearted naval surgeon friend of mine. Pelletier was the man I should choose, beyond all others, to have beside me in a pinch.

AND here we were, Wilkes and I, in a situation which I have endeavored to make as clear as possible, perhaps as tight a pinch as any human beings have ever been in, and the efficient and reliable Pelletier not only miles away from us, as we would think of the separation in earthly terms, but, actually, as our sight down that slope had devastatingly revealed, as effectively cut off from us as though we two human atoms had been standing on the planet Jupiter! There had been no moment, I testify truly, since I had been drawn into that tree-vortex and hurled regardless into this monstrous environment, when I had not wanted that tried and true friend beside me.

For, in that same desire to keep this narrative free from the extraneous, to avoid labored repetitions, I see that I have said nothing, so far at least, of what I must name the atmosphere of terror, the sense of malign pressure against my mind, and against Wilkes's, which had been literally continuous; which by now, under the successive impacts of shock to which both of us had been subjected, had soared hauntingly to the status of a sustained horror, a sense of helplessness well-nigh intolerable, as it became borne in upon us what we had to face.

We were like a pair of sparrows in a great, incalculable grip.

Against that dread Power there seemed to be no possible defense. We were, and increasingly realizing the fact, completely, hopelessly, Its prey. Whenever It decided to close in upon us, It would strike—at intruders, as the canny Pelletier, sensing our status on Its ground, had phrased the matter. It had us, and we knew it! And there was nothing we could do, men of action though both of us were; nothing, that is, that any man of whatever degree of fortitude could do. Therein lay the oppressive horror of the situation.

WHEN I opened my eyes my first impression was a mental one; to wit, that an enormous period of time had elapsed since last I had looked upon the world and its sky above it. This curious delusion, I have since learned, is due to the degree of unconsciousness which has been sustained. The impression, I will note in passing, shortly wore off. My second, immediately subsequent, impression was a physical one. I ached in every bone, muscle tendon and sinew of a body which all my life I have kept in the highest possible degree of physical fitness. I felt sorely bruised. Every inch of me protested as I attempted to move, holding me back. And, immediately after this realization, that old preoccupation with Pelletier re-established itself in my mind and became abruptly paramount. I could, so to speak, think of nothing, just then, but Pelletier.

Into this cogitation there broke a suppressed groan. With a wrenching effort, I rolled over, and there, behind me, lay Wilkes. We were, it seemed, still together! Whatever the strange Power might be planning and executing upon us, was upon us both. Very slowly and carefully, Wilkes sat up, and, with a rueful glance over at me, began laboriously to feel about over his body.

'I'm merely one enormous bruise,' said Wilkes, 'and I'm a bit surprised that either of us is—'

'Alive at all,' I finished for him, and we nodded, rather dully, at each other.

'Yes, after that last dash they gave us,' added Wilkes. Then, slowly: 'What do you suppose it's all about, Canevin? Who, what is it? Is it—er—Allah—or—what?'

'I'm none too agile myself,' I said, after a pause spent going over various muscles and joints. 'I'm intact, it seems, and I've got to agree with you, old man! I don't in the least understand why we're not in small fragments, "little heaps of huddled pulp," as I once heard it put! However, if It can use a typhoon to move us about, of course It can temper the typhoon, land us gently, keep us off the ground—undoubtedly It did, for some good reason of Its own! However, the main point is that we're still here—but where are we now?'

It was not Wilkes who answered. The answer came—I am recording precisely what happened, exaggerating nothing, omitting nothing salient from this unprecedented adventure—the reply came to me mentally, as though by some unanticipated telepathy, quite clearly enunciated, registering itself unmistakably in my inner-consciousness.

'Sit tight!' it said. 'I'm with you here on this end of things.'

And the 'voice' which recorded itself in my brain, a calm, efficient kind of voice, a voice which reached out its intense helpfulness and sympathy to us, waifs of some inchoate void, a voice replete with reassurance, with steady confidence, a voice which healed the raw wounds of the beleaguered soul—was the voice of Pelletier.

PELLETIER standing by! I cannot hope to reproduce and set down here the immeasurable comfort of it.

I stood up, Wilkes rising groaningly at the same time, a laborious, painful process, and, reeling on my two feet as I struggled for and finally established my normal balance, looked about me.

We stood, to my mounting surprise, on a stone-flagged pavement. About us rose inner walls of smoothed stone. We were in a room about sixteen by twenty feet in size, lighted by an open doorway and by six windows symmetrically placed along the side walls, and unglazed. The light which flooded the room through these vents was plainly that of late afternoon. Simultaneously we stepped over to the wide-open doorway and looked out.

Before us waved the dignified foliage of a mahogany grove, thickly interspersed with ceiba trees, its near edge gracious with the brave show of flowering shrubs in full blossom—small white flowers which smelled like the Cape jessamine. I had only just taken in these features when I felt Wilkes's grip on my arm from where we stood, just behind me and a little to one side. His voice was little more than a whisper.

'We're—Oh, God!—Canevin! Look, Canevin, look! We're back on earth!' His whispered words broke in a succession of hysterical dry sobs, and, as I laid my arm about the poor fellow's heaving shoulders, I felt the unchecked tears running down my own face.

WE stepped out side by side after a minute or two, and stood here, once more on true earth, in the pleasant silence of late afternoon and with the fragrance of those flowering shrubs pouring itself over everything. It was a delicate aroma, grateful and refreshing. We said nothing. We spent this quiet interval in some sort of silent thanksgiving.

And, curiously, Wilkes's oddly phrased question came forcibly into my mind: 'Is it Allah—or what?' I remembered, standing there in that pleasant, remote garden with its white flowers, an evening spent over a pair of pipes in the austere study of an old friend, Professor Harvey Vanderbogart, a brilliant young Orientalist, since dead. Vanderbogart, I remembered very clearly, had been speaking of one of the Moslem theologians, Al Ghazzali. He had quoted me a strange passage from the magnum opus of that medieval Saracen, a treatise well known to scholars as The Precious Pearl. I could even call back into my mind with the smell of the tobacco and the breeze blowing Vanderbogart's dull reddish window curtains, the resonance of his serious, declaiming voice.

'... the soul of man passeth out of his body, and this soul is of the shape and size of a bee... The Lord Allah holdeth this soul of man between His thumb and finger, and Allah bringeth it close before His eyes, and Allah holdeth it at the length of His arm, and Allah saith: "Some are in the Garden—and I care not; and some are in the Fire—and I care not... "'

Poor Vanderbogart had been dead many years, a most worthy and lovable fellow and a fine scholar. May he rest in peace! Doubtless he is reaping his reward of a blameless life, in the Garden.

And here, somewhere on earth, which was, for the time being, quite enough for us to know, stood Wilkes and I, also in a garden, tremulously grateful to be alive, and on our Mother Earth, glad indeed of this respite as it seemed to us; free, for the time being, of the malevolent caprice of that Power from Whose baleful control, we, poor fools, supposed that we might have been, as it were carelessly, released.

Our momentary illusion of security was strangely shattered.

WITHOUT any preliminary warning of any kind, those great trees before us on the other edge of the row of flowering bushes made deep obeisance all together in their deeply rooted rows, in our direction, as a great wind tore rudely through them, hurling us backwards like chips of cork before a hurricane, whipping us savagely with the strong twigs of the uprooted shrubs pelting us, ironically, with a myriad detached blossoms. This fearsome surge of living air smote us back through the wide doorway and landed us in the middle of that compact stone room, and died as abruptly, leaving us, almost literally breathless, and reeling after our dislocated balance.

There was, it occurred to me fragmentarily and with a poignant acuteness, a disastrous certainty brooking no mental denial, none of the benign carelessness of Allah about this Adversary of ours! His was, plainly enough, an active maleficence. He had no intention of allowing us quietly, unobtrusively, to slip away. If we had been landed once more on earth, it was in no sense a release—no more than the cat releases the mouse save to add some infinitesimal mental torture to that pitiful little creature's dash for freedom, ending in the thrust of those ruthless retractile claws.

Brief respites, the subsequent crushing of our very souls by that imponderable Force!

We pulled ourselves together, Wilkes and I, there in that austere little stone room, and, in the breathless calm which had followed that astounding clap of air-force, we found ourselves racked to a very high degree of nervous tension. We stood there, and pumped laboriously the dead, heavy air into our laboring lungs in great gasping breaths. It was as though a vacuum had, for long moments, replaced the warm fresh air of a tropical midafternoon. The stone room's floor was thickly sewn with those delicate white blooms, their odor now no longer refreshing; rather an overpowering additional element now, in the sultry burning air.

Then the center of the rearmost end wall began to move, revealing another doorway the size of that which led outside into the little garden now denuded of its blooms. As the first heavy, grating crunching ushered this new fact into our keyed-up joint consciousness, we turned sharply toward that wall, now parting, moving back as though on itself.

We LOOKED through, into what seemed an endless, dim-lit vaulted arena of some forgotten worship, into the lofty nave of a titanic cathedral, through dim, dust-laden distances along a level floor of stone to where at an immense distance shimmered such an altar as the Titans might have erected to Jupiter, an altar of shining white stone and flanked by a chiseled figure of a young man, kneeling on one knee, and holding poised on that knee a vast cornucopia-like jar, for all the world, as I envisaged it, like a statute of zodiacal Aquarius.

Greatly intrigued, Wilkes and I walked through the doorway out of our stone anteroom, into the colossal structure which towered far, far above into dimness, and straight across the stone-flagged nave toward this unexpected and alluring shrine; glowing up ahead there in all the comeliness of its ancient chaste beauty.

THAT the architecture here, including the elaborate ornamentation, was that of those same early Mayas concerning whom Pelletier had discoursed so learnedly, there could be no possible question. Here, plainly, was a very ancient and thoroughly authentic survival, intact, of the notable building propensity of that early people, The First Mayas of the High Culture, the founders of the predecessors of the present surviving and degenerate inhabitants. Here, about us, remained the work of that cryptic civilization which had so unaccountably disappeared off this planet's face, leaving their enduring stone monuments, their veritable handiwork, developed, sophisticated, with its strange wealth of ornamentation behind them as an insoluble riddle for the archeologists.

THAT this stupendous structure was a survival from a hoary antiquity there was all about us abundant and convincing evidence. I knew enough of the general subject to be acutely aware of that, that this represented the building principles of the earliest period—the high point, as I understood the matter, of the most notable of the successive Maya civilizations. That the building had stood empty and unused for some incalculable period in time was equally evidenced by various facts. One of these, unmistakable, was the thick blanket of fine dust which lay, literally inches thick, over everything; dust through which we were obliged to plod as though over the trackless surface of some roofed and ceiled Sahara; dust which rose in choking clouds behind and about us as we pressed forward toward that distant altar and its glorious statue.

That figure of the youth with his votive jar towered up ahead of us there, white, glistening, beautiful—and the dust of uncounted centuries which lay inches thick upon its many upper, bearing, surfaces such as offered support to its impalpability, caused the heroic figure to stand out in a deeply enhanced and accentuated perspective, lending to it strange highlights in shining contrast to the very dust's thick, quasi-shadows; a veritable perfection of shading such as no sculptor of this world could hope to rival.

We walked, necessarily rather slowly, on and forward toward the altar and statue, their beauty and symmetry becoming more and more clearly apparent as our progress brought them closer and closer within the middle range of our vision.

NATURALLY enough, I had pondered deeply upon the whole affair in which we were involved, in those intervals—such as our long night walk—as had been afforded us between the various actual 'attacks' of the Power that held us in its grip. I had, of course, put two and two together again and again in the unceasing human mental process of effort to make problematical two-and-two yield the satisfying four of a solution.

This process, had, of course, included the consideration of many matters, such as the possible connection between the existence of the Great Power and that same ancient Maya civilization; the basic facts, the original reasons back of the terror of those massed aborigines swarming in their forest cover all about the tree-circle; the placing in their appropriate categories of the phenomena of the Great Body; that mechanical regular pulsation which could only be the throbbing of Its circulatory fluids—Ichor was the classical term, I remembered, for the blood of a god; the 'ravines' which crossed each other like shallow valleys and which were the 'lines' upon that primordial palm; the hirsute growth adorning that titanic forearm which had glistened like metallic tree-boles as the morning sun shone down that slope, and which moved their tapering tops in the breeze from the cosmic nostrils.

All such as these, and various other details, I had, I say, attempted mentally to resolve, to adjust to their right and logical places and settings; to work, that is, mentally, into some coherent unity, literal or cosmic.

The process had included the element of worship. The gods and demigods of deep antiquity had had their worshipers, their devotees diabolic or human, and this as an integral part, an essential, of their now only vaguely comprehended existence; since day and night struggled for primordial precedence in the dim gestation of time.

THAT those prehistoric, highly civilized Maya forebears might have been worshipers of this particular Power (which, as we had had forced upon our attention, had somehow localized Its last stand here in these modern times—that Great Circle; the tree in its center as Its bridge to and from this world of ours) was a possibility which had long since occurred to me. That such a possibility might have some bearing upon that scientific puzzle which centered about their remote and simultaneous disappearance, had, I am sure, also occurred to me at that time. To that problem, which had barely come under my mental scrutiny because it was not central in terms of our predicament, I had, I am equally sure, given no particular thought.

That there could, in the nature of the case, be any evidence—'documentary' or merely archeological—had not entered my mind. I did wonder about it now, however, as we two plodded forward through those choking dust clouds, slowly yet surely onward toward what seemed to have been a major shrine of such forgotten worship, if, indeed, what I suspected had ever had its place upon this planet.

For one thing, the worshipers themselves would by now have been dust these twenty centuries; perhaps, indeed, the once-animated basis of this very powder which swirled and eddied about us two, up from underfoot as we pushed forward laboriously toward the shrine. There, in its forgotten heyday, that worship had sent swirling and eddying upward in active spirals incense compounded of the native tree-gums; the balsams and olibana, the styrax and powdered sweet-leaves of the environing forests; incense bearing upward in its votive clouds the aspirations of an antiquity as remote as that of the Roman Augurs, and to a deity fiercer, more inscrutable, than Olympian Jove.

IT would, indeed, have been a relief to us to see some worshipers now, human beings, even though, devoted as they might be to their deity in Whose hostile power we were held, such personages should prove correspondingly hostile to us. This unrelenting, unrelieved god-and-victim situation was a truly desperate one. Within its terms—as I have elsewhere tried to make clear—we felt ourselves helpless. There was nothing to strike against! A man, however resolute, cannot, in the very nature of things, contend with a Power of this kind! Useless mere courage, fortitude. Even the possession of a body stalwart, inured by exercise and constant usage against conflict and the deadly fatigue of intensive competitive effort, is no match for hurricanes—powerless against a Force which could be mistaken for a major geographical division of land!

Despite the fact that we had gone without rest or sleep, to say nothing of food and water, for a much longer period than was our common custom; apart, too, from the fact that these sound bodies of ours were just then rather severely strained and racked from the cosmic manhandling to which we had been subjected; leaving wholly out of consideration the stresses which had worn thin our nervous resistance—taking into consideration all these factors which told against us, I know that both of us would have welcomed any contact, even though it should involve conflict of the most drastic kind, with human beings, people like ourselves. They might be, for all of us, out of any age, past or present; of any degree of rudeness, of any lack of civilization, in any numbers—just so that they be human.

We did not know then—certainly I did not, and Wilkes was saying nothing—what lay in wait for us, just around the corner of time, so to speak!

WE had by now traversed about half of the distance between the anteroom and the altar. Behind us, a heavy, weaving, tenuous cloud of the fine dust we had disturbed hung like a gray, nebulous curtain between us and the towering rearward end wall of that enormous fane. Ahead now the altar glowed, jewel-like, in the slanting rays of a declining sun, rays which appeared to fall through some high opening as yet invisible to us. The genuflecting figure I have named Aquarius gleamed, too, gloriously, in its refined, heroic contours—a thing of such pure beauty as to cause the beholder to catch his breath.

About us all things were utterly silent, a dead stillness, like the settled, lifeless quiet of some abandoned tomb. Even our own footfalls, muffled in the thick dust of marching centuries, registered no audible sound.

An then, with the rude abruptness which seemed to characterize every manifestation of that anachronistic divinity, that survival out of an unfriendly past, there came without any warning the deep, soul-stirring, contrapuntal beat of a vast gong. This tremendous note poured itself into this dead world, this arid arena of a forgotten worship; the sudden, pulsing atmosphere of renewal, of life itself.

We stopped there in our tracks and the fine dust rose all about us like gray cumulus. We looked, we listened, and all about us the quickening air became alive. Then the vibrating, metallic clangor reverberated afresh and the atmosphere was electrified into pulsing animation; an unmistakable, palpable sense of fervid, hastening activity. We stood there, in that altered environment, tense, strained, every nerve and every faculty aroused as though by an unmistakable abrupt challenge. The altar seemed to coruscate in this new atmosphere. The zodiacal figure of Aquarius gleamed afresh in the sun's slanting rays with a poignant, unearthly beauty.

The slow, shattering sub-bass of the gong reverberated a third time, its mighty, overtonic echoes jarring the revived air with a challenging summons; and, before these had wholly died away and silence above the dust clouds established itself, out from some point beside and beyond the altar there emerged a slow-moving procession of men in long, dignified garments, in hierarchical vesture, walking gravely, two and two.

WE watched breathlessly. Here, at long last, was the fulfilment of that half-formulated wish. Human beings! Here were worshipers: tall, stalwart men; great, bearded men, warriors in seeming; bronzed, great-thewed hierophants, bearing strange instruments, the paraphernalia of some remote ritual—wands and metal cressets; chained thuribles, naviculae, long cornucopiae, like that upon the flexed knee of Aquarius; harsh-sounding systra, tinkling triangles, netted rattles strung with small, sweet-chiming bells; salsalim, castanets, clanging cymbals; great rams' horns banded with plates of shining fresh gold; enormous, fanlike implements of a substance like elephants' hide; a gilt canopy, swaying on ebony poles, ponderous, its fringes powdered with jewels, sheltering a votive bullock, its wide horns buried beneath looped garlands. This procession moved gravely toward the altar, an endless stream of grave, bearded men, until, as we watched, stultified, wondering, the space about it became finally filled, and the slow-moving, endless-seeming throng, women and girls among the men now, turned toward us, pouring deliberately into the forepart of the nave.