RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

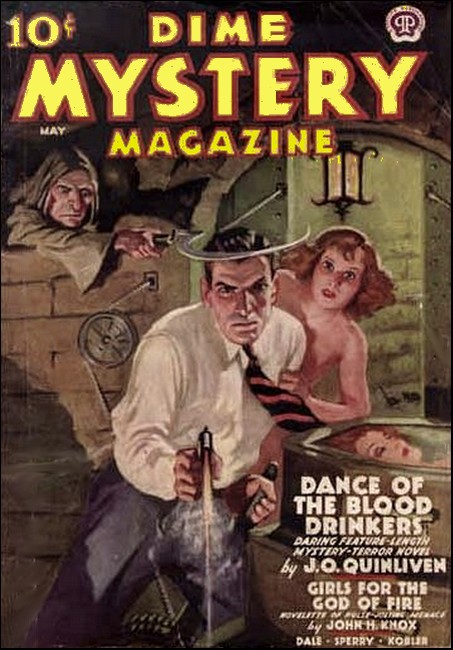

Dime Mystery Magazine, May 1938, with "The Experiment of Dr. Sardi"

Why was pretty little Nurse Townsend in deadly fear of her well-paid job? Why was she never permitted to see those strange patients in Doctor Sardi's mysterious hospital who came and went in the silence of the night?

DOCTOR ANGELO SARDI was very drunk. If Nurse Townsend didn't notice it immediately, it was because the girl was occupied with her thoughts. She had decided to leave this place, give up her well-paid job as the secretary to the famed gynecologist and seek employment somewhere else. There was too much mystery attached to Dr. Sardi's establishment. She had been here almost three months—and she had yet to see a patient enter or leave the place. In fact she had seen no patients at all. They were there, all right—five of them, at the moment. She knew that because of the provision orders which had been given her by Dr. Sardi that very morning. That meant two had been discharged during the night, because for a week she had been ordering for seven.

But had those two patients actually been discharged—or had they just... disappeared? What had happened to the dozen or so others who had come and gone while she had been here? She was supposed to be a nurse and a secretary—but she was never allowed upstairs to minister to the patients, and she had nothing whatever to do with any of the paper work connected with them... Why? All she did was answer the infrequent ringing of the telephone—it was always the grocer, druggist, or some medical supply house salesman seeking an appointment with the doctor. She did nothing, really, and she never saw anyone but Dr. Sardi.

And this time Dr. Sardi was very drunk. He came and took a chair beside her as she sat at her little desk, leaned toward her with a fat grin on his fleshy, flushed face. His thick but sensitive fingers closed over her knee, caressing the silken smoothness under the starched linen of her uniform, in a transparent assumption of fatherliness.

"My dear," he said thickly, blowing alcohol fumes in her face, "I've got some interesting things to tell you, tonight—very interesting. Among other things, I want to tell you you're promoted. Yes, sir—promoted to full assistant. And with a double increase in salary... How d'you like that?"

Dr. Sardi gave her knee a final squeeze and leaned back, grinning at her in inebriate benevolence.

Nurse Townsend didn't like it. She still wanted to quit, to leave this place as quickly as possible. But something made her hesitate—perhaps a fateful curiosity. As Dr. Sardi's assistant she would learn more about his mysterious sanitarium—discover the identity of those shadowy patients up there on the second floor whose faces she had never seen, whose names she had never learned.

Dr. Sardi leaned forward again. "I've watched you, my dear," he said. "I've put you to the test—many times. You are discreet; you ask no questions. That is the quality above all which I need in an assistant. Also you are a nurse with a truly scientific attitude of mind. You will appreciate the value of the work I am doing, and will not be squeamish about certain details which another woman might find—er—unpleasant..."

The last sentence was almost a question, and Nurse Townsend felt the physician's small eyes, suddenly cleared of their alcoholic dullness, probing her own keenly. She felt a threat in that stare; knew that the man, himself, constituted another threat. Her beauty was a menace to her own safety in this place... But still she could find no words to announce her decision to leave...

IT was only natural that Dr. Sardi's patients should

all be women. He was a gynecologist—a specialist

in females' diseases, and as such he had won nationwide

attention. Yet, time and again, as the physician talked on,

explaining in a vague, non-specifying manner the nature of

the work he was at present engaged in, Nurse Townsend felt

a shudder shivering along her taut nerves.

They were in the library, now, and Dr. Sardi had produced a bottle of brandy, was drinking it copiously, pressing it on her. Nurse Townsend drank a couple of ponies—it helped to steady her nerves. And the doctor kept on talking, pulling manuscripts out of drawers and showing them to her briefly—then withdrawing them, as if he were afraid that she would read too much. Obviously he was leading up to something, sounding her out as he went, striving to decide for himself how she was going to accept the final revelation.

Always the talk was about embryology—about the growth and development of the child before birth. And about the parturition of other mammals: cattle, sharks, leopards; the strange animals of Australia: the kangaroo, and the dugong and duckbill.

At last his monologue drifted to his patients—those women, upstairs. "You see," he explained, watching her carefully, "they are not really patients at all, my dear. They are experimental subjects. I got them here—Oh, never mind how I got them. They came of their own free will; you may be sure of that. They all signed affidavits absolving me of any blame in case—well, anything happened, you know..."

The physician leered at her, his fat face sweating with the heat of the alcohol in his veins. He took another drink, then came over and sat beside her on the divan against the wall, staggering a little as he walked. His speech, as he began talking again, was thicker.

"The superman," he said loudly, swaying toward her until his fetid breath fanned her face. "We've been searching for him for centuries—never in the right place... I've found him... Anyhow, I know his combination." He laughed drunkenly.

The girl shrank away from him in an involuntary movement of disgust. Instantly the physician grasped her wrist and held her to her seat. But he went on talking as though he were delivering a lecture.

"What's the most dangerous period of a man's life?" he asked rhetorically, and immediately answered his own question: "Infancy, of course. From the moment of birth to seven or eight years of age. Most deaths then—excepting after senescence sets in. It's the time, moreover, when the structure an' system of the individual most likely to incur damage which'll last throughout life. All right. Why not avoid that period altogether? Gestation period nine month's, eh? Why not extend it? Why not make it—seven or eight years?"

Nurse Townsend jerked her wrist, held irremovably in the physician's sweating grasp. "Let me go!" she cried. "You're drunk, Dr. Sardi. Oh, let me go!"

The doctor grinned fatly and slowly shook his heavy head. "I'm drunk, all right," he muttered, "but not that drunk. I've got you, m' dear, an' 'm gonna keep you. You're my assistant, now, y' know. An' if you do' wanna do it of your own free will—why then I'll have to use a li'l force. But you an' me—we're gonna conduc' an experiment. An' one of these fine days the world'll have its superman—"

The girl was fighting, now, desperately, hysterically. But the man's brutal strength was too much for her. He held her easily with one huge, fat paw, as with the other he began to tear her white uniform from her body. And as though, indeed, he were merely conducting an experiment, he continued talking in the manner of a lecturer.

"I found the right road, an' I've come a long way on it. Done things the whole world believes impossible, already. Produced hybrids by the dozen—hybrids, mind you, that were born already mature. You thought there were five women upstairs, didn't you, my dear? There's only one. Yesterday there were three—but two of the experiments failed." He chuckled and began jerking at the belt of her skirt.

"Yes, two failed. But the one that's left—she's coming along fine. O' course she eats an awful lot—naturally. I had to make out she was five—for your benefit, m' dear—"

Nurse Townsend screamed. Her skirt parted in a long rip down the center seam. The physician jerked it free of her limbs, and the girl writhed in his grasp, clad only in brassiere, step-ins and hose. Dr. Sardi's blood-shot eyes gleamed as they slid over the slender contours of her body, and his thick arms went about her in a crushing embrace. At that moment, from somewhere in the regions above, came a ripping scream.

NURSE TOWNSEND had many times heard the fearful sounds

human beings give vent to when in the extremities of agony,

but she had never heard the equal of that one horrible

shriek. For that was all there was—just one. After

that there was a silence which was almost as terrible as

the sound had been.

Dr. Sardi released her and sprang to his feet, stood there for a moment, swaying. "It's come at last," he muttered finally. "Now we'll see—"

Apparently forgetting the dishevelled girl, he began walking across the room, staggering a little. He reached the door, disappeared into the hall.

Sobbing, Nurse Townsend picked up the remnants of her uniform, drew them about her body. Then, not even delaying long enough to look for some garment to cover her semi-nudity more effectually, she darted toward the door.

But out in the hallway she came to a sudden halt. A woman had screamed up there—a woman in the last extremes of unspeakable agony. Probably that shriek had marked her death—most likely she was beyond anyone's help. And yet, as long as there was some chance that she still lived, the little nurse could not bring herself to flee. She stood there in the hall, clutching the rags of her dress and sobbing hysterically, fighting with her terror.

Suddenly the girl dropped the remnants of her uniform, and lithe and quick in her brief undergarments, sprang toward the stairs—those stairs she was now ascending for the first time in all her months in this house. So long as there was a chance that some suffering fellow human being needed what poor protection she could offer, she was not free to save herself...

The upper hall was a long, lightless corridor, from the dark walls of which white oblong patches marking doors stood out dimly in the gloom. All were closed save one—on the right side, half-way down. Swinging ajar, a dim effulgence as of moon-shine, came through it. There were no sounds, now, of any kind.

The girl crept forward on tip-toe, and the nearer she got to that open door, the stronger grew her panicky longing to turn about and run the other way as fast as her graceful legs could carry her. She strained her ears for some sign of life from that room, but there was none. Only that eerie, ominous silence which seemed to cloak something of unthinkable horror.

As she moved forward, the mad words of Dr. Sardi rang in her mind, hinting at bestial experiments, prefiguring monstrosities of nature which might be lurking behind the doors of this enigmatic hallway. But it was insane—impossible. How could a child—or any animal—remain alive in its mother's body beyond the normal period of gestation? Delayed births had occurred, of course—but these were matters involving days, not years. Not seven or eight years...

And then she was at the door, was peering cautiously and tremblingly around the jamb...

IT was not moon-shine which came from that room—it

was the pale effulgence of a small mercury lamp. The lamp

was hanging from a bracket near a bed, a bed which was

empty, but which gave signs of having been occupied. A bed

having stains upon it which, in the ghastly rays of the

mercury lamp, looked black, but which Nurse Townsend knew

only too well were really deep red.

There were a host of other objects near that bed: three oxygen tanks, a table bearing a vast assortment of retorts, condensing bottles and other laboratory equipment. A large scaffold which, the little nurse guessed, must support an x-ray machine...

The girl's terrified glance took in all that in a fraction of a second. Then her eyes swept across the room—to fix in paralyzed horror on a thing which lay just beneath the east window.

At first she did not recognize it as a human body. Then, as her shuddering gaze took in its details, she knew that, distorted, misshapen and mangled as it was, it could be nothing else. It was the body of a woman, but beneath the flaccid, empty breasts, it was not like the body of any other woman who had ever lived in this world. It was huge beyond belief—but as a great, empty bag is huge. For it had been ripped open as a great balloon is ripped, and the red, ragged edges of the skin and flesh were thin as paper.

Then, from her left, came a sudden, choked cry. The girl whirled about, and shrank back against the jamb of the door, Her sick, widened eyes fixed on a sight which drove every atom of self-control from her body and left her leaning there, helpless and paralyzed, in imminent danger of falling to the floor in a dead faint.

Dr. Sardi stood there, flattened back against the wall, his sweat-beaded face, in the ghastly light, appearing like that of a drowned and bloated corpse. And his staring eyes were fixed on a long, snake-like thing which reached out toward him from around the corner of a chest of drawers standing next to him.

The physician wrenched his fascinated gaze from the thing long enough to throw Nurse Townsend a frightened glance. "Look out," he mumbled. "Get away quick. It's got me cornered. Get help—Oh, God!"

The last was a scream. As though the sound of the doctor's voice had accelerated its movement, the snake-like thing shot forward and flung itself about the physician's ankle, was followed by a huge, bulbous body, from which other snake-like appendages squirmed and writhed across the floor, carrying the gross shape from behind the chest into the open with unbelievable swiftness.

The physician screamed again—and then the thing was upon him. The great tentacles wrapped about his fat body and dragged him shrieking and futilely struggling, to the floor. Then the thing seemed to flow over him with an indescribably smooth motion, and the tentacles, like muscular, boneless arms, tightened.

There was a cracking sound, and Dr. Sardi's head, encircled by one of the tentacles, moved grotesquely sideways, turned until the staring, horror-drowned eyes seemed fixed on the trembling figure of the little nurse in the doorway. The girl saw a beak-like mouth open at the base of the bulb-body of the thing, and the tentacle about the physician's neck slid quickly away. The thing flowed forward across Dr. Sardi's chest, the beak-like mouth dipped at the doctor's throat, and a red stream hissed upward from a severed jugular. Then the triangular mouth closed and a slobbering, sucking sound filled the room. The red fountain subsided.

Nurse Townsend's eyes rolled upward, and her white, cold body slid almost soundlessly to the floor...

THE physician stood up and looked down at the wan-faced

girl on the bed. "I can't believe it, Nurse," he said.

"I simply can't believe Sardi really did it. I'll admit the evidence seems to be on his side. The unbelievable condition of that woman's body. The presence and condition of the octopus, itself. And, of course, Dr. Sardi's notes. But even granting he was able to introduce the egg of the octopus into the woman's body, and was able to hold it in the transverse colon until it hatched, how in the name of all that's holy could he have nourished it and kept it alive—to say nothing of the woman, herself. He says, in his notes, that he by-passed the colon and created an artificial opening in the duodenum, which provided the beast with food. Ridiculous—it couldn't possibly be done!"

But Nurse Townsend was aware of a certain lack of conviction in the physician's voice.

As he turned and went away, grumbling to himself, she relaxed in her white bed and closed her mind on the horror she had witnessed. She had a moment of feeling grateful to her lucky genius which had provided a rescuer for her in the form of the janitor, lured by the strange sounds from above into the forbidden regions of the second floor—the janitor who had dragged her unconscious body out of danger, who had called the police and helped kill the giant octopus—and then she dropped off into untroubled sleep.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.