RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Adventure, 29 February 1924, with "The Fish-Nets Of Quoipa-Moiru"

THEY were quite wonderful nets really—considering all things; handmade out of hand-spun llama wool and every detail of their construction accomplished by Quoipa himself under difficulties every bit as great as the Israelites labored under when they had to make their bricks without straw.

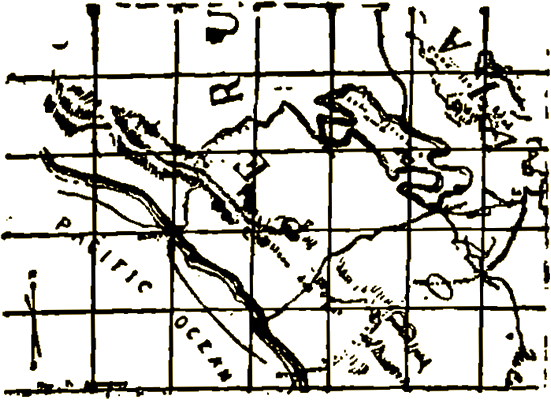

Quoipa was an Aymara Indian, and his condition of life was not very much better than that of those same Israelites. To begin with, the climate was against him. He lived in that ghastly tableland between the Cordillera del Mar and the Cordillera Real, the altiplano of the Andes, stretching from Peru, through Bolivia, to Chile—once the bed of an enormous lake; now a vast barren plateau, two hundred miles wide and thirteen thousand chill feet up in the air, with the lake shrunken to a paltry hundred and twenty miles in length, half in Peru and half in Bolivia.

To go on, the rulers of the land—or at least certain of their representatives—were against him. For it was his ill fate to live in a portion of that altiplano which had fallen into the hands of political land-grabbers who exploited the dwellers upon their soil.

And finally, even his fellow Indians were against him. For of all that sullen, uncommunicative race, he belonged to the most isolated group, the fisherfolk of Lake Titicaca, landless nomads of that great inland sea, who had come least under the influence of the white invaders, and whom the land Indians, serfs of the soil, called charaachallhuappa, web-footed, a queer, scaly people apart.

Quoipa himself was probably more typically Inca than Aymara—though he himself had never heard even a legend of his mighty forebears. All that was lost, ruthlessly rooted out by the fierce zeal of the priests in their efforts to banish everything pagan. Only here and there a witch-doctor, hiding in secret places, retained memories of the lore that used to be.

So Quoipa knew nothing even of the existence of such a race as the Incasyocca. But he had the pronounced cheek-bones and slightly oblique eyes and wide mouth of the great stone god of Ollantantaybo, and his limbs were as short and as burly in proportion. The skin of his muscular torso appeared at a short distance to have the sheen of a rich brown velvet, but a closer inspection showed that it actually was a scaly sort of integument. Exposed to constant wet and then to the cutting winds of that thin air, it chapped in a maze of intricate channels and powdered off in myriad minute flakes.

His shoulders and neck where the poncho chafed were creased and furrowed like the neck of any other creature that toils beneath the yoke. His only other garments, in spite of his clammy occupation, were a pair of short, baggy pants, rotted and frayed out at knee height from permanent soaking, and a narrow-brimmed felt hat. Not a very merry life was Quoipa-Moiru's.

He would have been more comfortable even as a peon, a serf of the soil, like all the land Indians; and a strong lad such as he might easily have indentured himself to one of the grafting politics. But the spirit of his fathers glowed strongly in him, just as it glows in the heart of any one of his white brothers of a whaling family from Gloucester. He was a sailor by heredity, and he had, moreover, inherited the business from his father, Quoipa-Allamm.

Immersion in freezing water and drying in an icy hurricane clear off the snow masses of the Cordillera had one day proved too much for the old man's years and had smitten him with the fierce pneumonia of the high levels. In that rarefied atmosphere there could be but one outcome, and that as swift as the cholera of the low levels of that self-same parallel of latitude. He had just about time enough to gasp.

"My son is my son. Who I was he is. My business is his business. My house is his house."

And having thus settled his worldly affairs according to prescribed custom, he died, and his son changed his name from Quoipa the son of Allamm to Quoipa-Moiru and became a grown man, master of his own destiny.

The "business" had consisted of two bean-poles and a long, narrow double paddle. In a country thirteen thousand feet high, where no wood grows at all, what else could the owner of such assets be but a fisherman? All that was necessary besides were a boat and nets.

The boat was easy, even though there was no wood available. Quoipa cut bundles of the tall tortora reeds which grew in the shallows of the lake and bound them together into two great, fat, torpedo-shaped cigars, ten feet long apiece. These he lashed side by side; and presto! there was a boat as good as ever his father or his father's grandfather had had.

It weighed nearly a ton and it rotted within the year. But it had a great advantage over most boats in that it was quite unsinkable. The two bean-poles, thrust each into one of the cigars a little forward of amidships, and bound together at the top, formed a skeleton mast which supported a sail like a Japanese window-blind of tortora slats. When the wind was fair the craft plowed along as merrily as a water-logged derelict. When the wind failed out in the middle of the lake—which was forty miles wide—well, even a ton of floating debris could be driven by a double paddle and a pair of very muscular arms—somewhere, sometime.

The nets were a more intricate problem. There was no market where wool for their manufacture could be bought, even if Quoipa had any money. For he lived in the little fishing village of Challa, which snuggled behind the ancient Sanctuary-of-the-Rock on the very sacred Island-of-the-Sun in the middle of that icy lake called Titicaca. Nobody would give him wool. For the land Indians, cultivators of the soil and herders of llamas, needed their wool for ponchos and blankets. True, he could trade in wool for fish. But in order to have fish it was first necessary to have nets.

The nets of Quoipa's father had been lost recently when he dragged the deep bottom at the base of the precipitous cliff upon which stood the sacred rock. They had caught in something hard and heavy, and the lines had just given way.

Mamu, the soothsayer of the rock, who was so old that he had forgotten his father's name, said angrily that such was no more than was to be expected; for the waters at the base of the cliff were huaca, tabu; and the angry spirits of the people of the old time who had been cast from the great slab of grooved diorite at the base of the rock lived in the deeps, servants of the huaca: and that these had held on to the nets and rent the lines.

The spirits were angry, he said, because certain of the poverty-stricken fisherfolk of Challa, seduced by money, had helped impious white men to dig up the ground around the ancient labyrinth temple behind the rock; and because some of these profaners had been known actually to touch the Sacred Rock without having been instantly killed by their hired slaves. So the spirits had shown their anger by killing Quoipa-Allamm who dragged the deeps below the rock. Let all the people beware, therefore. There were certain things huaca which must never come to light

All this was very bewildering to Quoipa-Moiru. He knew, of course, from his boyhood that there were mysterious somethings connected with the ancient temple and its surrounding waters which must never be laid bare. All the fisherfolk knew that, though the land Indians said it was all rubbish—the good padres from Sorata had told them so. Yet Mamu the soothsayer spoke angrily of the padres and insisted shrilly that they knew nothing at all. But he never seemed to be able to tell just what these huaca things were. He would just lower his eyes and complain that he was very old and that the chatterings of the young men wearied him and that he had forgotten.

And that was all the satisfaction that Quoipa-Moiru could ever get on the subject of the nets of Quoipa-Allamm.

YET his own need for nets was urgent. It was but an additional hardship in his already hard life that in order to have nets it was first necessary to have wool.

So Quoipa-Moiru went forth by stealth like a poacher of protected game and gathered his wool under difficulties. He made chilly night forays upon the stone corrals of the llama herders and snatched handfulls of their greasy coat from the live beasts, who squealed and spat green slime at him. The herdsmen came out of their mud huts and stood at their doors, peering into the dark, fearful of devils. Then with high-pitched quavering cries of "Ulu-ulu-ulu-ulu" to encourage each other they whirled their slings round their heads and fired jagged stones at the shadowy marauder. Unlike David of old, they reserved the smooth round ones only for the correcting of wilful llamas. For human or superhuman enemies jagged flints were much better.

Quoipa found these raids more exciting than profitable. So he reverted to the more tedious gathering up of the stray tufts that clung to the sparse low wind-blown tiquilla shrubs. Or again he would sit in the thin sunshine and patiently unravel a worn-out blanket—part of his heritage—and would respin the yarn on a queer little bobbin which he twirled between his toes.

With these heterogeneous findings he made his nets, small-meshed and wonderfully strong; and thus equipped at last, he embarked full-fledged upon his profession, comforting himself with the thought that while he might be just a little bit ostracised by the land Indians as a sort of amphibious creature, he was also just a little bit feared, as being in closer touch with witchcraft than were his "civilized" compatriots who came more nearly under the influence of the good padres. And he had distinct cause for rejoicing in the thought that be was at least master of his own miserable toil and no serf, as were the landfolk who labored three days in every week for the owner of the soil upon which they lived. Not so very different from a sturdy Gloucesterman was Quoipa-Moiru in his point of view.

And then into his isolated speck of the world came the white man. He came upon the little steam-boat that runs—every now and then, when the engines happen to be willing—from the Peruvian port of Puno to Guaqui at the other end of the lake to connect with the Bolivian railroad to La Paz city. The little boat ran quite close in to the steep shores of the island, shot out a plank, landed the man with his little baggage and his two companions and snorted off on its way, leaving them to their own devices.

The white man was big and red-headed and bull-voiced. He was a scientist—he said so himself; and he had come up into this inhospitable land through the Peruvian port of Mollendo via Cuzco, where he had been studying the ruins of the ancient Inca capital. His companions were two almost-white men. They were, he said, his assistants, Peruvian scientists, who were anxious to study ancient ruins with him.

A swarthy, shifty-eyed couple. One of them had a scar, white against the sallow skin, which ran from his cheek-bone to the angle of his mouth. He was apparently the better scientist of the two; for he knew exactly what to do with Indians. He seized upon two of the nearest in the group who stood gaping at the strange visitation, cuffed them as a preliminary to understanding and made them carry the baggage to the very center of the sacred labyrinth, where he paid them well with a kick apiece and told them to stand by for further orders. They stood, meek and expressionless, as was expected of all the Aymara of the altiplano.

The baggage was of the scantiest. A tent, the barest of necessities for food and a long, heavy package done up in sacking. No richly-equipped scientific expedition, this. With a great deal of not very scientific swearing and a sufficiency of very scientific blows they made the two Indians understand how to set up the tent, and after that all the work seemed to devolve upon the white man, for the other two shivered in their cloaks and huddled themselves in the sunshine.

"Carramba," they swore in unison; and, "By the Sacred Pipe, what a frozen fiend's country is this, where the cold is always and where there is no wood to light a fire with! Mercy of —— that we came at least in the season when this worthless sun is not lost behind the mists."

And, "Nails of the Saviour, was it not I who said so?" the man with the scar prided himself. "Give me belief, friends. It is I, Sanchez, who knew whereof I spoke when we took the map from that dying old fool."

Quoipa-Moiru, who was one of the favored Indians, spoke a little Spanish, as did a few others of the more intelligent fisherfolk. But not nearly enough to note that the speech of these scientificos was the speech of the Mollendo water-front.

Then the scientist who knew all about Indians found time to recollect that he had no further use for the two who stood so obsequiously to heel. So he paid them off with another kick apiece and sent them off to rejoin their fellows, who watched from a distance with slow, bovine stolidity. After that he seemed to consider that he had contributed enough of scientific endeavor to the enterprise; for he retired within his cloak, swathed to the nose; only his two glittering eyes showing, and cursed the cold.

It was the more robust white man who unpacked the scanty cooking appliances and prepared a nondescript sort of a meal over a kerosine primus stove to the accompaniment of futile imprecations upon the other two who remained shivering within their wrappings. After which he prowled, as hungrily as if he had not fed at all, through the ruined labyrinth.

THE sacred place lay in the shadow of the Rock, a maze of passages and courts and massive walls. Vast blocks of granite, twenty feet by five square, pyramidal in size, but so carefully cut and fitted that they held through the ages without any cement, which was unknown to the ancient builders. Whether a temple, or living quarters for the priests and sacred virgins, or both, has never been determined. The field for research was immense.

The divine fire of scientific investigation spurred the red-headed man to energy. He nosed about the giant blocks of masonry and made measurements and stamped every now and then with a heavy foot upon the ground and listened with the cunning expression of a bear looking for honey in a hollow tree.

That, with small variation, seemed to be the program for the next few days. The two almost-white scientists, wrapped in their black Spanish cloaks, crouched in the sunshine upon a block of carved granite like a brace of ragged condors and watched with the same beady-eyed keenness as the great carrion birds that sailed immensely above them, while the red-white scientist prowled and rooted and grumbled like a huge brown bear. From a distance the fisherfolk watched all three, sullen, aloof and expressionless.

From above, the giant condors, almost as big as the black-cloaked figures, watched every least little movement of everything that moved with their everlasting vigilance and their telescopic eyes.

Their shadows, huge as silent aero-gliders under the sun, circled and crossed and recrossed over the ground like dark premonitions of evil. The Indians looked at them with superstitious divination and told one another—

"Khamachi k'Inti amúthua pfayapila. The birds of the Sun God prophesy food."

And they muttered in guttural agreement—

"Yes, the Sun Birds know all things."

There was truly something of foreboding in the endless circle and swoop of the great silent shadows. They must have got on the white man's nerves; for suddenly, on the second day, he leapt up from his prowling and shook his fists up at them in impotent rage and shrieked curses upon their cold yellow eyes. Quoipa and his friends, watching, muttered to each other—

"They have marked down that one already."

The white man directed his wrath in a less futile direction, and his bull voice broke as be screamed at his companions, who brooded in their black wrappings for all the world like two of the great carrion birds come down to gloat.

"Why, by the most sacred name, can't you two mestizos come and be of some use here? You'd think I was the only prospector in the outfit"

At the bastard appellation the eyes of the man with the scar glittered as yellowly as a condor's. But he crawled down from his perch and came scowlingly to the other's assistance. From under his cloak he produced a paper upon which he kept a suspicious clutch, and together they pored over it and pointed along certain of the ruined walls and measured distances and presently planted a little stake in a certain spot.

"That paper," said the Indians to one another, "must be very sacred; for by virtue of it that little man holds ascendency over the other two."

And so the study progressed for three more days. Quarrelling, arguing and snarling at one another, referring constantly to the paper of mystic power, the "scientists" planted sundry stakes on certain selected spots.

As the condors watched unceasingly, so watched the Indians. One or two, at least, always; distant, aloof and incurious.

Finally the preliminary survey was apparently concluded. Direct and more exciting action was the order. The long heavy package was unwrapped, and disclosed digging-tools. The nature of the study which had drawn this ill-assorted trio together became more apparent.

"I'll dig here," said the white man. "And you fellows take the next stake."

He was almost cordial with pleasurable anticipation, and forthwith he attacked the ground with powerful strokes which indicated more experience with a spade than was altogether proper for any true scientist. But digging was much too menial an occupation for half-breeds of the Mollendo water-front. The man with the scar stepped on to a huge, perfectly squared monolith and called authoritatively to the distant watching Indian.

There happened to be only one just then. It was Quoipa again. The rest had gone fishing. Quoipa should have been out fishing too. But it was not so long ago that he had received his little lecture on the sacred nature of the ancient labyrinth and the mingling of curiosity and resentment that fermented slowly in his mind was a powerful magnet. He came hesitatingly, half-distrustful, half-willing. Yet the lack of co-ordination between emotion and expression which is the heritage of all his people was extraordinarily apparent. His oblique eyes and wide mouth showed no more sign of his thoughts than the idol they resembled

"Here, fellow, dig in this place," said the mestizo. "I will give you money."

Quoipa had seen money before, though be had never had any of his own, and greatly did he desire it. With money, if one could earn a great deal of it—say as much, possibly, as a dollar—one could buy enough wool all in a lump to make a whole dozen of nets without incurring the risk of another deep scar from a jagged sling-stone in one's back, such as Quoipa already had. One could even hire a skilled craftsman to make nets for one and thus increase one's business to a profitable enterprise with a single bound. Or, one might embark on a career of high finance, lending out nets to other less fortunate toilers of the deep on a share and share basis, and thus live a life of ease and comfort—comparatively.

So Quoipa-Moiru curbed his misgivings about the things that were huaca and took the spade that was shoved at him and dug with a will. The two almost-white scientists who were too proud to dig crouched again on their perches and watched his every move with jealous eyes.

From the red-white scientist's side came oaths and angry complaint.

"Por Dios, Sanchez. Have we measured aright, think you? I find nothing but mud and little stones like arrows and worthless pots."

Mere foolish relics of a vanished race which a collector would have bartered his soul for. But the red-white scientist just shoveled them aside and swore.

"Carramba," snarled Sanchez, muffled behind his cloak. "Was it not yourself who measured? As for the map, the old fool swore even as he died that it was correct, and the little figure that he showed was gold of the purest."

The big red-beard dug in vicious silence for another hour. Then he straightened his back and cursed some more. An idea came to him. His head swung bearishly low over his shoulder and his pale blue eyes frowned through a mat of ruddy brow at the rival excavation. He stepped out of his shallow hole and strode over to look into the digging of his partners in scientific endeavor. There was a borning suspicion in his inspection. The muffled birds of prey laughed in sour harmony.

"Well, what d'you think we're finding? Ingots?"

Since they had been suspecting the very same thing against him they knew exactly what was in his mind. They had already suggested covertly to one another that it would be just as well to keep an eye on the gringo's work, but they disliked the thought of intruding on his savage temper just then, and in any case all his movements were so profanely open that there was no real cause for anxiety that he was hiding out anything on them.

He returned sulkily to his own digging and resumed work. Progress was slow. The floor of the court in which they dug had been hard-trodden by many thousands of feet pressing upon it over a period of nobody knows how many hundreds of years. What packed crowds had surged and stamped through those massive quadrangles in prayer or dance or frenzy of sacrifice was only a matter for conjecture to students. That the Sanctuary-of-the-Labyrinth was especially holy to the Incas when the awful blight of Pizarro fell upon them is known. Evidence which might lead to the piecing together of the story remains to be unearthed by students of Inca history—as these "students" were assiduously unearthing just now.

The red one dug with a vigor worthy of such high scientific endeavour, and cursed the arrow heads and painted pots which impeded his progress. It was late when his spade struck something hard. At his exclamation the two hopped off their perch and hurried over to the hole like vultures to a corpse.

"What is? What have you found? Carramba, that one is permitted to see!"

They crowded in on him, eagerly rapacious. He threw them off with savage irritation.

"Sacred body and blood! Get off o' me! How can I dig with you two hanging on my elbows? Give room."

They gave perhaps six inches, muttering that they had a right to see what he found. He growled something inarticulate and drove his spade into the hard earth in a frenzy. Again came a metallic clink. The red one dropped on his knees and scrabbled with his hands in the dirt. A thick finger caught under the edge of something. A rapid fire of high-pitched oaths came from him as he strained at it, for all the world like the whine of a terrier at a rat-hole. The others crowded in on his elbows again. Suddenly he snatched his hand away and cursed in plain English as blood from a deep gash in the ball of his thumb dripped into his digging.

The eyes of Quoipa-Moiru, staring with dull disinterest into his own pit thirty feet away, continued so to stare without a nicker. He might have been a statue of one of Millais' toil-crushed peasants. Yet he muttered to himself just one word—

"Huaca."

The red-headed man's rage turned against the two who hampered him, and they shrank from the fury in his face. Then at length intelligence asserted itself sufficiently to snatch the discarded spade and attack the obstinate thing again. A few strokes loosened it. He thrust his hand into the débris once more and with a final grunt jerked forth to the light a broad, flat blade of a dark glassy material.

That was all.

It was an obsidian sacrificial knife such as the high priests of the sun had used to cut the hearts out of their living human sacrifices. A priceless museum specimen. Only one other authentic example was known to exist.

The red-headed scientist held it in his hands and stared at it in silence for a long half-minute. Then with a hoarse scream of rage he swung his great arm and hurled the thing from him far out over the stone ramparts. In the ensuing silence the faint splash of it in the lake came back to them like a derisive silvery laugh.

At the same moment the sun, which had been peering over the edge of the Cordillera to see the last of the fiasco, dropped silently behind. And immediately with the shadow came the accentuated chill of the evening; and the towering, jagged snow caps, thrown into clear blue silhouette, seemed to advance with a single stride and hang impending over the very edge of the lake.

Still nobody spoke. Till Sanchez shivered, and wrapped his cloak more closely round him.

"Que carramba," he muttered brokenly. "Yet the old fool had proof that not all the gold was thrown into the lake. Valgame Dios."

And, so muttering, he walked slowly to the tent.

His compatriot followed him; and after an interval of hesitation the white man decided to call it a day and went too, pausing to kick with a recurrence of moody suspicion at the other digging. They all stood around doing nothing. The reaction of disappointment was too keen to permit them even to quarrel. Quoipa-Moiru stood in the background, impassive and bovine as ever. Sanchez noticed him at last. He was too dispirited to vent his spleen on him personally; but he called to his compatriot who stood nearer to kick the dog in the stomach and chase him off. Then he countermanded with quick forethought.

"Hold," he said. "Better pay him something, I suppose; or tomorrow, perhaps, we have no laborer."

So Quoipa-Moiru possessed money for the first time in his life. Two silver pieces. About half a dollar. It was munificent, princely. Another lucrative day like that, and he would be able to realise some of his dreams. Nets would be his for the ordering. Leisure and emancipation from the continual wet.

Yet there stirred somewhere deep within his impassive exterior some vague impulse from the dim superstitions of his fathers. He understood nothing at all about it, and he knew but the faintest rumors more than nothing. It was a hereditary instinct of secrecy rather than a conscious reason. There were certain things huaca. That much was sure. And there had been the omen of the bleeding hand.

So Quoipa-Moiru went that same night to the hut of Mamu the soothsayer and told him all that he had done.

MAMU was as inscrutably wise as he was unbelievably old. Nobody knew just how wise or how old. He was the hereditary seer of the Sacred Rock. That was as much as even the Indians knew. His father had been a seer before him, and his grandfather before that; and they must surely have been terribly old in their day. More than one learned padre with a genuine thirst for ethnological research had tried to get into communication with the old wizard, one of the few remaining who could lift a little corner of the veil.

But Mamu would have none of the padres. Particularly was knowledge to be hidden from the white men, he maintained. This was his hereditary instinct. So no white man had ever seen the face of Mamu the Soothsayer. He was a rumor; a legend as fugitive as the legends of the lost race from which he was descended.

Mamu crouched, a blanket-swathed bundle, in the dimness of his little mud hut. Since he was very old and the life pulsed slowly through his shrunken frame, a tiny flame of smoldering lakia raised the inside temperature perhaps five degrees above the normal night. It was sufficient to throw faint highlights on a shrewd old face of a thousand furrows with an extraordinarily high and narrow bald forehead and beady little black eyes as alert and cunning as a raven's.

Quoipa, squatting on the other side of the tiny fire before him, telling the tale, saw presently nothing but the eyes glowing out of a vast darkness, and he settled down from his squirmings and fidgetings before the wizard and told all the truth, even to the matter of the two silver pieces. By the time he had come to the end of his tale he sat as motionless as the seer himself and only his lips moved.

Mamu heard him to the end and waited for more, the eyes compelling the last shred of detail of what this one had said and that one had done. Then the eyes closed and, as if a lamp had gone out, it seemed to Quoipa that only a vast blackness remained. Slowly the glow of the fire reasserted itself in his vision, and Mamu spoke out of his ancient wisdom.

"Great grandson of my friend," he said, and it was an order, "thus shall it be done. There are things huaca which must never come to light. Listen to the wisdom of our fathers. In the old days was darkness over all the earth and much misery. Till the Lord Sun listened to the prayers of Manco Capac his priest and took pity upon the people and burst from the cleft in the Sacred Rock to take up his abode in the sky. Thus became Manco Capac the first of the Incas and established the huaca which has been since that day.

"Always have the spirits of the huaca protected their own. Always will they protect. The omen of the bleeding hand was a true sign. As the spirits took back to themselves the sacred knife from that white man, so will they keep the other greater things that the white men seek. Always from the seekings of these white men has evil come upon our people. Therefore, great grandson of my friend who was, since I am old and the night is chill, I give into your hands a charm, huaca of a hundred-fold and very powerful. The sacred sign of the Inca, no less. This you will place this night upon the mold where you have dug. So shall it work its magic against these profane ones. To-morrow, when they have gone, you will bring it back to me and will forget what you have seen."

A shrewd old psychologist was this heir to the wisdom of the lost race. He crutched himself on his wasted arms to a comer of his hut, where he burrowed a moment in a pile of ancient rags, and then he hobbled back and handed the potent charm to Quopia, who greatly feared to take it. Yet the compelling eyes were upon him, and he stretched his hand across the fire smoke.

"Look upon it that you may know it again,' commanded the voice behind the eyes.

Quoipa's eyes were able to drop reverently upon the sacred thing which just filled his palm. It was a disk of metal, yellow and heavy, and in the dim glow he could discern the sign chiselled deep into the dull surface. A burnished circle with rays projecting from it; within it, a cube. Suddenly he prostrated himself before the thing and hid his face in the dust of the floor.

"Go, servant of the huaca," said the voice above him, "and do its bidding with speed."

Quoipa crept from the hut very much afraid and sweated in the cold night air.

THE next morning, before dawn, he was ensconced in a cranny between two great blocks of squared stone to watch the sacred thing that was in his care, wondering darkly how he was to get it back to the wizard and how the spirits would set about protecting their own. The thin glow that began to outline the distant peaks of the Eastern Cordillera had hardly established itself before the sun leapt from a mountain-top with the same suddenness that it sprang from the Sacred Rock in the days of Manco Capac.

Instantly its emblem, lying on the little heap of yesterday's digging, heliographed back a golden greeting. Quoipa-Moiru shaded his eyes and took a vast comfort from the omen. He wrapped his poncho about him and crouched motionless in the morning chill to wait and watch.

Three shivery hours passed before the white men crawled out of their tent, yawning and disgruntled. They stood about aimlessly and shivered. It was too cold to wash, and they were too dispirited to think so immediately about breakfast. These were not the kind of scientists who could labor tirelessly for weeks on the meager return which Science so often vouchsafes to her devotees. Yesterday's disappointment on top of their high hopes had sapped their ambition and left them ill-tempered and peevish.

The red-white man thought with disgust about food and strolled listlessly over to the scene of yesterday's labor to speculate on the chances of trying others of the staked-out spots. The emblem of the sun winked malignantly at him.

And then it was given to Quoipa, the watcher, to see how shrewdly the old wizard had reasoned. Only to him the swift dénouement of the story was but the manifestation of the spirits of the huaca protecting their own.

The white man stopped as if shot, and instant suspicion blazed into his already ill-tempered face. He snatched the thing up and turned it over in his palm.

"Gold, by—!" he snarled. And the next immediate thought: "Lousy crooks of spiggoties. Holdin' out on me, yeah."

The rage gleamed the whiter on his face for the ruddy background. He swung up his head in that curious bearish action of his and bellowed as he would to peons—

"Veng' aquí, you crooked lice!"

Both men looked up, startled at his tone, indignant and stung out of their apathy to vindictive energy by the insulting name. They came over together, muttering sideways counsel to one another as they came. The big white man's fury had reached that point just this side of explosion at which his face was dead white and his voice almost calm, though with a hysterical tremble in it. He held out the disk in his palm.

"I've made a lucky find," he said with devilish sarcasm. "Lucky for me, that is."

The two gaped at the thing with boggling eyes, and their suspicion in turn was immediate and unanimous. What was be doing poking about their digging? Why was be pretending to find this thing there? How much more was planted away somewhere? His was the place where all the arrow-heads and pots and the knife had been. Sorely gold also.

All these things passed between the two with perfect understanding in the first swift glance. They found expression in the double query—

"Is that all?"

Then the red-white man's rage exploded. And thereafter the spirits of the sacred huaca thing wrought their magic with appaling speed. Suddenly the big hairy hands dropped the disk and shot out to grip a yellow throat in each. The thick fingers almost encircled the lean necks. There was no wriggling out of that grip. The fierce gust of his fury shook them as a hurricane shakes frail saplings. His breath frothed between his clenched teeth as he gritted:

"Hold out on me, ye yellow-bellied mestizos, would ye? Hide up the stuff, ha? Where's the rest of it? Where'd you plant it, ye crooks? 'Fess up before I rip the gullets out o' you."

With head rocking like a ball on a limp string and teeth clicking together, Sanchez managed to gasp:

"You. You yourself—f-f-found—ca-carram—"

"I? You lying dago! Curse you for— By —, I'll get some truth out o' you!"

Crazed by his own violence, the red maniac backed them both against the wall, clawing at his face with futile hands, and fell to banging their heads against the stone, which reddened with each furious smash.

The wicked yellow glare in the eyes of Sanchez gave place to choking, starting terror. The other lolled limp. Slowly, with many slips as his tottering balance failed, the right foot of Sanchez lifted, steadying itself against the wall behind him. His right hand went down to meet it while his left clawed at the strangling grip.

More than once the hand nearly reached; and then the foot was stamped down again in the desperate need to keep upright.

Once down, he could see death at the hands of that maniac. At last groping hand and unstable boot connected. His desperate grip fastened on the thin handle of the mestizo knife in his boot-sheath. For just a flash the terror in the staring eyes gave place to snarling hate; and then Sanchez braced himself against the wall with the last of his strength and heaved desperately forward. The sun flashed thinly on a swift upward arc, and blood spurted from both strangling forearms together.

With a hoarse shriek the big man let go and stood staring for a moment in incomprehending wonder at the spurting blood. Sanchez fell back against the wall, gasping and nursing his throat. The other slumped to the ground and rolled over to his hands and knees, coughing.

Only a moment. Then the big man's voice broke again in a scream such as a dumb man might give in agony, and the madness took him. With the sudden clumsy speed of the bear and with the same demoniac red gutter in his eyes, he snatched the spade from the mound of earth at his heels and in the same motion drove it in a fierce upward thrust at the spent figure plastered against the waH.

The broad blade, like an old-time halberd, struck low on the sagging chin and crashed through jaw and throat beyond. Sanchez subsided slowly, sitting on nothing against the wall, clawing with nerveless hands spread-eagled against the stone, and rolled over, gurgling horribly. The murderer grinned maniac satisfaction and stood panting inarticulate things.

"That'll teach ye! Yellow — Double-cross me, yeah? Lousy half-breed—"

The insane tendency was to go on indefinitely; but his attention was distracted by a moaning cry of awful fear. The other man was staggering to his feet and running drunkenly across the court toward the exit least littered with fallen stone. The cry was his undoing. The lust was upon the killer. He shouted what might have been some atavistic battle-cry of his long ago forefather who lived m a cave and rushed after the wretched runner, brandishing his weapon in the air. He caught up with him just as he reached the low pile of débris at the far doorway and aimed a frightful blind swipe with the spade.

It was no club such as his forefather used when the red rage possessed him; but it was heavy enough to beat the exhausted man to the ground. The maniac shouted his battle-cry again and turned the edge and hacked at the prone figure till it squirmed no more. Then he grinned his primordial triumph over it and frothed foul epithets upon its treachery.

A great aeroplane shadow sailed over his head, banked steeply and circled over again. It perked a red-wattled bald head over to one side and croaked sepulchrally.

Another, and another. So low that the rustle of their pinions in the wind was an audible pr-rr-rr of dry sound.

The maniac's head flung back and the pale eyes glowered at them from under the overhanging fringe of brow like an animal glaring from a cave. His laboring breath came from between his set teeth in a spluttery hiss, and he shivered with some far-off recollection of something that began to impinge upon his brain.

Reason began to reassert itself. And with reason, fear. With an abrupt start he dropped the instrument of death upon which he supported his red hands and swung his head in that animal gesture to look over his shoulder at that other gory heap.

"Jeez!" he muttered. "Jeez!" And mumbled, his fingers at his lips.

Terror swooped down on him like the black shadow of one of the funereal birds. Suddenly he began to run. Blindly, lumberingly, stumbling over fallen blocks and piles of débris. Out and away from that haunted place of sacrifices. Down to the lake's edge.

Long, logy tortora bundle-boats of the fisherfolk lay there. Not hauled ashore like white men's boats, for they were too heavy. They floated some thirty feet out in the shallows at their stone anchors. Never stopping, the white man splashed out to the nearest. Climbed in, snatching his legs up as if some primaeval water monster were after him. Poled out with great lunging thrusts of the long paddle against the reedy bottom. Then plowed up the water with vast clumsy erratic strokes, heading for the pale purple shore of the mainland. Away from that terrible island of evil spirits. Looking back over his shoulder, he saw a great carrion bird, black against the morning sun, dip and swoop behind the gruesome rampart. Another and another. The beating of giant wings, and the hiss and scream of them as they fought, pursued him over the water.

"Jeez!" he muttered again. "Jeez!" And he bent over and strained his great shoulder muscles against the long paddle.

QUOIPA-MOIRU came softly from his hiding-place. On his face was visible expression at last. Not horror; not shrinking; not disgust. Only awe for the potent fetish which he was compelled to approach; to touch; to carry back to the old wizard who was so wise.

Mamu the Soothsayer squatted in his doorway wrapped to the eyes in a flaming crimson and green poncho, letting the sun soak into his old bones. Quoipa placed the ancient relic of the Inca at his feet with a vast relief and pressed his head to the ground.

"Yatina k' chekka. Holder of all knowledge," he mumbled. "All the omens were true." And he recounted with passionless detail all the things that had happened.

The seer stretched a withered hand from under his poncho and took in the sacred fetish thing.

"All the omens are true, great-grandson of my friend," he nodded. "The things that are huaca will never come to light. Go, and forget what you have seen. For the spirits of the huaca will surely take to themselves those who have knowledge which must be secret. As they will surely take that white man when he comes again—for surely he will come, drawn by the power of the sacred sign. When that day comes, bring me word again. Go and be silent."

Quoipa-Moiru went. And it is probable that he did forget; so impressed was he by the magic of the aged soothsayer.

Shrewd old wizard.

So Quoipa returned to his fish nets; and his luck—surely on account of his virtue in the matter of the silver pieces—was phenomenal. His nets, when those of his fellows were tearing all about him, remained miraculously immune. Bad bottom in the shallows just melted away when his gear fouled. The little boga fish swam close to the surface and showed themselves—which surely was a mark of the especial favour of the spirits.

For Quoipa's method of fishing was the most primitive in the world. He would go out in the cold gray morning with his fellows in whatsoever direction the wind happened to be blowing. Gradually diverging, they would cruise the lake, peering into the pale blue chilly depths, looking for fish.

When the wind ripples were too fast; or when the water was misty—as it was whenever the spirits of the lake need an offering— they could see nothing. Sometimes the water would remain misty for days at a time, and the spirits would not be satisfied with offerings of colored wools and corn and frozen potatoes.

In the old days when this happened there would be a great ceremony at the Sacred Rock, and a high priest, all loaded down with gold and feather-work, would sacrifice a maiden upon the great slab of diorite with the blood channels carved in it. But nowadays Quoipa and his fellows were a peaceful folk. All they did was to give more potatoes; and in extreme cases they would make a night foray and steal a young llama from the land Indians to offer to the spirits and would hope earnestly that one of the land Indians might inadvertently get drowned in the lake.

However, in these lucky days there was no occasion to steal young llamas by the dark of the moon. The favor of the water spirits was with Quoipa the virtuous. The lake remained cold and clear. Its characteristic pale blue was paler than had been known in a generation. The winds blew to greet the sun in the morning and to make gentle obeisance in the evening; which meant that there were no long, back-breaking paddle-races home. Cats' paws, where Quoipa searched, melted away and left an unruffled glass surface through which he could discern the schools of boga at phenomenal depths.

Then Quoipa would whistle shrilly like the little barred hawks that hunted so assiduously for lizards over the bare rocks of his home; and all the tortora boats with their window-blind sails would converge upon him with answering whistles—so that the spirits of the water would think that the spirits of the air were calling upon them for food for their birds. And they would ring the foolish boga round with their nets; silly fish, who didn't know enough to disperse and break away, but huddled together in a terrified bunch till most of them were taken.

Quoipa and his people were becoming unprecedently rich in goods and gear gained in trade for their produce.

And then, into his prosperous era of peace, came once again white men.

They arrived as had the others, by the wheezy old steam-boat that ran—every now and then—from the La Paz railway terminal at Quaqui to the Peruvian Port of Puno. As had those others, they brought a tent and cooking-pots—not quite so meagre as the last—and a long heavy box.

One of them was a dry, withered, little old man, scant of straggly gray beard and hair, sharp of feature and of tongue, with a pair of the brightest, most inquisitively bird-like eyes magnified to startling proportions by heavy tortoise-shell-rimmed toric lenses.

The other was in direct antithesis, a large, beefy, much younger man, with a clean-shaven, full-blooded face and a mop of black hair and heavy brows; an uncouth creature in comparison with his alert elder.

The fisherfolk had learnt to regard while men and long heavy packages with suspicion. But the younger man spoke to them sharply. Quoipa was thrust forward as having had experience with the ways of the white lords. There was no retreat. So with sullen indifference he helped them to establish themselves under the growling direction of the young one, who seemed to be some sort of servant and interpreter to the elder, who spoke no Spanish, but fussed around giving endless directions as to the exact disposition of their gear to the younger, who translated some of the instructions with a sulky air of rebellion.

When it was all over at last, and every littlest item had been carefully checked over by the fussy "Water Hen," as the Indians immediately dubbed him; when Quoipa was getting ready to receive his kick and dismissal, a miracle happened.

The Water Hen's worried expression gave place suddenly to the kindliest smile in the world, and he fished from a mess of booklets and papers and pencils in his bulging pocket a piece of real money and handed it to Quoipa.

Quoipa was as properly thunderstruck as he had a good right to be. What manner of white men were these? Or rather, this one? For there remained a vague suspicion against the younger.

The latter was speaking again at the direction of the elder, who hopped nervously about trying to understand what was said and nodded eager confirmation when he thought he had caught a word or two. Quoipa clutched the precious money in his hand and struggled with the evil spirit of avarice. Money in his band again! Gods of his fathers! What lifelong comfort might not be attained with just a little money!

Yet the instincts of his fathers stirred in the back of his consciousness. There were certain things huaca, guarded by powerful spirits who could awfully demonstrate their displeasure. And the tale that these men brought was even more preposterous than that of the three scientificos. These simple ones said that they wanted to catch fish. Nothing less—and no more. Just fish out of the lake. All the kinds there were. Was ever such foolishness heard before? When only the boga were fit to eat.

"Good," said Quoipa. He would sell them all the fish they needed, and very cheaply.

"No," the young man insisted with irritation. They didn't want to buy fish. They wanted to catch them themselves; and they needed the services of a man with a boat.

"How mysterious," said Quoipa. "Were they, then, also scientificos?"

"Yes," said the young man. And then, no, he was just the old man's helper and interpreter; and the old man was entirely mad; and what the — business was it of the Indian dog's anyhow.

Here the old man smiled again and nodded violently and performed another miracle.

"Jalla," he said. "Challhuma munti. Ma-real churramma."

Which was fairly understandable Aymara far, "That's right. I want fish. I'll pay you one real a day."

For the second time in his life the stone idol which was Quoipa's face registered an emotion. A keen physiognomist would have detected a distinct trace of surprise. He stepped back out of the range of black magic and muttered:

"Awai! My father has the tongue?"

The old man nodded again with the delight of a child.

"Little, little," he said. "Good padre, la Paz. Teach. You work. I pay."

And he held up a silver real and moved his hand in an arc across the sky from East to West.

Quoipa wondered what the mysterious signs were for. Magic, probably, he thought. But he understood "Ma-real churramma" very well. So he hired himself out as a boatman for more money than he quite believed existed. And then went straightway to tell these things to Mamu the Soothsayer.

OLD Mamu squatted poncho-wrapped before his hut just as though he had never moved a limb since the last time. He listened with narrow-eyed attention to the telling, prompting Quoipa from time to time with a keen question to elicit fuller details of the manner, and speech of each of the men. Then he fetched his medicine-bag embroidered with figures of llamas and bulls and cast the coca leaves to divine the omens, stirring them with a skinny forefinger to let the wind tumble the leaves, and recasting. Long he pored over them. Then he delivered his verdict.

"Thus shall it be done, Quoipa, great grandson of Quoipa my friend. The old one is without guile. Do all that he says and take the money he gives. Thus also is virtue rewarded. The young one is evil. His desire is only for things huaca that must never come to light. Therefore everything that he desires is huaca. But he is not to be feared. The spirits will take to themselves their own and will take also very shortly that white man. Go then; and what is done by day, come and report each night."

Rather cryptic, as is the way with oracles. Quoipa's intelligence was not very great. He gathered from it all only a reiteration of the inviolability of the things that were tabu; and he went away full of wonder for the wisdom of old Mamu who could divine so many things about strangers from a far country.

How was he to know that the ancient keeper of the mysteries had watched their arrival with the same jealous suspicion as he had watched the arrival of all strangers for heaven knows how many decades? And even had he known, why should he question the wisdom of a wizard who gave him leave to accept a princely salary from a foolish employer?

In three days he would have three reales, a dollar. In six days he would be wealthier than any man on the island. Quoipa knew nothing about praying; but he hoped very earnestly that the spirits would not be too hasty about taking their promised toll; and to add power to his wish he tied many fathoms of brightly dyed woolen yarns— enough to make a very fancy net—into odd lengths and queer knots, as his father had done before him without knowing anything about the meaning of it all, and floated the tangle away on the lake below the Sacred Rock.

Yet the spirits worked with appalling swiftness. Quoipa took his employers out in—or rather on—his boat; for there is no inside space to two bundles of tortora reeds— and caught boga fish for them in miraculous draughts. Each time the old man sorted the catch eagerly over and selected but a few; and each time he demanded, "niaraqua," other kind.

Truly was the old man quite mad, thought Quoipa; when everybody knew that there were but eight kinds in all the lake, and that of these the moccomacu and the luaru, so far from being not good to eat, were actively poisonous. Still, what business was it of his, since old Mamu had told him to do all that the old one ordered?

All day they ranged the lake looking for niaraqua; and at night the foolish old man opened up the suspicious chest and took from it a queer little shiny squirt with a long sharp nozzle and filled up his assorted catch with an acrid smelling liquid which brought tears to his eyes and which he called formalina; and then he wrapped them lovingly in. soft cloths and put them bodily into a big bottle containing another mysterious liquid which smelled most familiarly like the cane alcohol which the fisherfolk smuggled over from the Peruvian side for the land Indians when they made fiesta.

A weird rite, this. Quoipa made up his mind that the old man was a magician and reported the same to Mamu. But the seer was in no way indignant about a rival in his field. All he questioned about was the young man. What did he do? How did he act. What was his speech?

He acted sulkily, said Quoipa. He sat at the other end of the boat from the old one, taking no interest at all in his quest for niaraqua; and he answered him roughly when called upon to help with the nets; not at all with the respect that a servant should show.

"Hm," muttered Mamu. "Watch him carefully, and tell me all that he does."

So for four days more they cruised the lake looking for profitless fish that nobody could eat; and the evil young man's temper soured with each hour. He growled fiercely at the old man, who shrank from his anger. What he was saying was:

"Why the — don't you tell him to fish the deep water under the big rock? That's where you'll get your blasted specimens. I'm telling you what I know, mister. He don't listen to me, curse him; or I'd make him take us over myself."

The meek old gentleman apparently took umbrage at last. He adjusted his spectacles with a thin-veined nervous hand and made his feeble play to put his assistant in his place.

"Mr. Hogan," he said with acid formality, "I hired you in Mollendo on your reputed knowledge of these parts, and on your own professed anxiety to come as my assistant in my work. I am sorry to say you only obstruct. It is my desire to study the shallow water varieties, of which only three are known, before I take up the larger matter of the deep-water fishes. In my own good time I shall—"

"Aa-rrgh! To — with your desires!"

The young man's voice broke as he screamed his rebellion and his incongruously pale eyes glared sudden rage as he made a motion as if to scramble over and strike his employer. But he was still capable of common sense. With many swallowings and clenchings of convulsive fists he restrained his temper and contented himself with snarling:

"Well, if you won't tell him I'll — well make him go over anyhow."

He turned to Quoipa and ordered him in Spanish:

"To the big rock. We fish the deep water below."

Quoipa remained standing inert, sullenly incomprehending. The big man scrambled savagely to his feet and pushed roughly at his shoulder to face him round in the required direction. But Quoipa was astonishingly muscular, and his bare feet had known tortora floats for full twenty years. He braced his body against the thrust; and the beefy white man's only success was nearly to push himself off his balance. The boat careened over; at which the old man uttered a startled cry and assented with nervous acquiescence.

"Yes, yes. To the big rock. Go."

So Quoipa headed impassively for the Sacred Rock. But he managed his Japanese slat-sail very craftily. The deep water below the rock was huaca, the abode of those spirits who had torn the nets of his father. Here was distinctly a case for the wisdom for Mamu to pass judgment upon. It was sunset when they arrived.

OLD Mama had been watching the boat for half the day from the top of the rock, which was huaca to all but himself. But Quoipa found him in his hut crunched over his tiny dried-dung fire, too feeble to brave the cold air.

What does the young one say? What does he do? Was all the wizard's interest.

So Quoipa, under the spell of the glowing eyes, disclosed every last detail of all the little things that had lost themselves in his subconscious.

"And his manner is exactly as the manner of that other great red one who fled," Quoipa enlarged. "Also his rage is as terrible. Further, he performs every night a ceremony, anointing his head with a water which he guards most carefully. A magic, without doubt, to give him strength. His voice, moreover, is—"

Old Mamu grunted in a most unmagician-like manner.

"Quoipa-Moiru," he said. "You are a fool. Four days have you been in the presence of this evil man, and know nothing. What color, tell me, is the hair on his arms?"

Quoipa had to visualize the man for himself.

"The color," he recalled with pained reflection, "is the color of a red llama, though not so red as a poncho."

"Good. And the color of the eyes?"

"The color of the eyes is the color of the lake where it is not too deep."

The magician's grunt was a snort of scorn.

"Doubly are you a fool, Quoipa-Moiru," he told him. "Yet even a fool who catches fish may know that the color of any llama may be dyed any other color, even black; and that a beard may be —"

Quoipa Moiru sat upright on his heels and clapped his hand over his open mouth and so remained, dumfounded at the wisdom of this seer who saw all things. The glowing eyes took hold of him, and all the rest merged into a haze, and the haze into a vast blackness, and out of the blackness came the voice, authoritative, compelling.

"Thus shall it be done, Quoipa, great grandson of Quoipa my friend. Tomorrow the young one will give order that the fishing be in the deep water below the rock, which is huaca; for evil spirits have given him a knowledge which must be kept hidden. It may be that the spirits of the huaca will keep hidden what is theirs, as they hid it from him before, and as they kept it hidden from the nets of your father. It may be that the evil spirits whom the white man serves will prevail. In which case"—the voice became thunderous in its commanding force— "you, Quoipa Moiru, are the servant of the huaca in my place, who am old; old and feeble"—the voice began to dwindle away to a faint point in the darkness— "feeble and very old; having no strength but the strength of the knowledge of our fathers. Alas, very feeble and very old."

Quoipa Moiru remained rigid, sweating in the cold dark, his eyes held fixed by an immeasurably distant point of light from which the voice came. The light glowed and twinkled like a faint star and began to come nearer and to expand as it came. Nearer and faster, till it rushed at him with the speed of a comet. Dully his mind urged him to flee; but his limbs remained frozen. With a final swoop the hurtling thing brought up with an abruptness which was a shock in front of his face and remained there, glowing as if red-hot from its frightful speed. It became borne in upon him that he had seen it before. A disk with a burnished sun and a cube in its center. Suddenly the voice boomed out close to his side.

"Look once upon the sacred sign on the Inca, Quoipa-Moiru, protector of the huaca. Look and be strong."

The glow sank slowly lower, and dwindled, and grew dull, and then enlarged again till it became apparent to Quoipa that it was only the glow of the dung fire after all. The voice of old Mamu was droning as it had droned for the last four days:—

"Go, Quoipa Moiru, great grandson of my friend, and bring me word of all that happens."

He went, greatly fearing, and understanding nothing at all. Only one matter was rooted in his mind.

"Things huaca which must never come to light."

THE morrow's dawn brought swift verification of all the wizard's prophesies. The young man, exactly as had been foretold, was for the first time eager to get to work. He took truculent charge of affairs and gruffly ordered that fishing was to be in the deeps along the cliff under the Sacred Rock. The old man weakly acquiesced rather than brave his violent temper.

Quoipa-Moiru, in his not very astute mind, marveled at the wonderful pre-vision of the wizard, and with immobile stolidity paddled round the little promontory and cast his nets as directed.

Almost immediately there was luck. The lines tautened as the nets dragged against resistance. For the first time since the beginning of the work the big young man was eager to help with the hauling in. Slowly the weight came up. The young man began to become as excited as Quoipa was stolid. The catch began to shimmer up through the pale blue depths. Quoipa's hardened muscle heaved as stoutly as did the bull strength of the beefy young man. His excitement—with his certitude of battle between guardian spirits of the huaca and evil spirits of the white man—was tenfold as frightful as the other's. But all the reaction he showed was to grunt and heave like a small derrick.

Another moment, and the excitement of both of them collapsed like overstrained balloons and transferred itself in all its joint power to the old man. The young man cursed his God. Quoipa Moiru grunted. The old man squealed.

The weight was a miraculous draught of fishes.

The gods of sacred science gave him of the strength which the young man ceased to employ. Up came the net; and the old man, with the avid cries of a raptorial bird, flung himself upon it. Into it, rather, he dived, and embraced the whole slithery mess.

They were boga mostly; but a continuous croon of happiness announced every now and then a deep-water moccomacu or a luira. And then a scream of joy heralded a new species. The old man scrambled out of the slimy shambles and loved the wriggling thing, calling it pet names in Latin with his own appended thereto.

"Quite and unfeignedly mad," said Quoipa Moiru. "And therefore," as that infallible old seer had already told him, "without guile, harmless. But that other. The evil one?"

That one glowered sulky disappointment. As he had once before demonstrated, he was not of the kind that could labor long without reward. It was the old man who directed further operations with enthusiasm. For that one specimen he was disposed to forgive and forget all past unpleasantnesses.

So Quoipa cast again and caught fish with varying success.

"Closer in to the rock," growled the young man.

Quoipa looked to the old one for confirmation. That one was crooning over his dead fish and was inclined to be agreeable to anything. So Quoipa paddled in right under the brow of the Sacred Rock and knotted in an extra length of line and cast

The net dragged stickily over the unseen depths and came up, not exactly heavily, yet with a certain reluctance. The pale water muddied as it rose. Black ooze and clots and gummy clods bulged from the net. Quoipa hoisted the whole load on board to wash out the mess. One of the sticky clods was more uniform in shape than the rest The young man's pale eyes lit with sudden interest as he reached out a hairy paw for it. He sluiced some of the black muck from it, and the cleaned surface showed black again. But the spirit of excitement leapt like a live thing with a volition of its own from age back to youth once more.

"A curiously shaped cooking-pot of some sort," said the old man with mild interest. "I suppose some Indian has dropped it over the cliff." And he told Quoipa Moiru, "The fish seem to be further out. Back off a bit."

But, "Cast again right there, you black swine," snarled the young man with a sudden access of ferocity. "At once, or I'll— Cast in, you!"

The old man quailed before the savagery in the young man's eyes and for the sake of peace gave in. Quoipa cast with a wooden face and averted head and watched the young man apparently through the back of it. The latter crouched over the pot with lips bared in a greedy snarl, like a wild beast over it's kill; impatient to feast and ready to defend. With a clasp-knife be scraped at the blackened surface; and suddenly his breath escaped from between his teeth with a sharp—

"Aa-ah."

The old man was half-heartedly helping Quoipa to haul in the net; so he did not see the yellow glint under the blade. Quoipa was manfully hauling at his line with his back to the stern of the boat where the young man crouched, so he surely could not have seen. The young man wedged the "curiously shaped cooking-pot" between the twin cigars of tortora reed and cone to add his more than willing strength to the labor.

Another load of black, evil-smelling mud came up. No need for Quoipa to wash the stuff out. The young man growled as he dropped on his knees over it and set to squeezing the foul paste through his fingers. Every last morsel of it. His mutterings were the noises of an angry bear rooting for grubs which it did not find. With a final curse he flung the net over once more and growled—

"Let 'er go."

The old man sat meekly acquiescent. Another heavy sticky haul. The young man doing most of the eager work this time. Somehow, in the struggle with the line, Quoipa changed places with him. And somehow, inadvertently, as they strained together, his foot slipped, tripped over the cooking-pot, and it swept into the rake. Nobody beard the little plop of its sinking and nobody saw the little stream of bubbles that it left

Up came the evil load of black stuff. Once more the young man cast himself upon it and growled ferocious warning. Growled louder as be scrambled in the muck. Nothing again,— Yes, something. Long and hard. He sluiced it hungrily.

"Blood of God, and curses upon the sacred shoes!" Only a bone. The savage disappointment turned upon the boatman.

"I'm a — if I don't think you're soldiering on me. You've drifted out, ye sulky dog. Get in closer, where we got that pot, or—"

And then be noticed that the pot was gone.

For a split second his glare was pure wild beast. And in that second it took in every cranny of the boat and every bulge in its occupants' clothing. In a tortora reed raft nothing of that size could be hidden. With that realization his bull voice broke to its characteristic false pitch, and he screamed blasphemies upon his God in English and in Spanish and stamped his feet in the boat and shook his great fists in the air in the savage impotence of his rage.

When the lurid stream began to bubble thickly for sheer lack of force behind it the old man attempted a feeble pacification.

""My dear Mr. Hogan, you really must calm yourself. The thing must have gone overboard, of course. Doubtless someday you may find another. In the meanwhile it is quite evident that the fish prefer to run a bit farther off shore. So——"

The torrent of the other's wrath, all the stronger for its temporary stay, surged up against the interference. With face twitching and heavy brows jerking up and down like a gorilla's, the man screamed his uncontrollable rage again.

"Blast your hide, ye silly old —. D'ye think I hooked up with you and came up here to give a hoot about your stinking fish? Do I look that big a fool? I'm here to— I— Ye poor goat, if you interfere with me, I'll— Curse you, shut yer head and get outa here! Get off o' this boat! That's what! Hanged if I won't put you ashore! That's what I'll do. Come buttin' in on me all the time! Here—" to Quoipa— "paddle ashore an' heave this old fool out!"

And as Quoipa remained inert, he scrambled forward and beat him from his paddle with a rain of blows and drove the boat himself with savage strokes round the bend of the tittle promontory. On the beach beyond, he seized the old man by the arm, jerked him ashore with a brutal heave and threw his precious hoard of fish after him.

Quoipa Moiru stood, dully unpartisan, in the middle of his boat as he had always stood. The dominant white man stepped on board again and ordered:

"Go on, back to the same place! And well get something a damsite better than fish."

Still Quoipa-Moiru stood, immobile as a rock, and as rugged and sullenly unreceptive. The white man's teeth snapped in an animal snarl again as be gripped him by the arm and drew back a heavy fist to strike. Then a thought came.

"Fool!" he hissed at him. "Ill give you fifty reales. A hundred, if you'll see sense and do as I tell you."

Quoipa Moiru's face changed never a line. But he took up his paddle and drove the boat round the curve of the promontory.

THE old man was left alone with his dead fish. He slumped down on the sand among them and felt very old and frail and alone. The sudden rebellion of his hired assistant was as disastrous as it was inexplicable. Alone in an inhospitable land. The old man sat with his poor old head in his thin, helpless hands and thought and puzzled and hoped that the other might return presently in a better frame of mind. He would overlook everything, he told himself. He would make

concessions. He would even let his work suffer, if thereby he might maintain a working standard of peace.

But the chill of sundown drove him to the shelter of his tent before the prodigal rebel returned. The night he spent was very miserable. His single thought was as to how he would be able to continue his work without the help of the assistant upon whom he had relied. If that good Indian lad, who seemed to understand so well, might be willing, perhaps—but the Indian was probably by this time cowed into submission by the brutal savagery of the big young man, even as he himself had been cowed

A very miserable night indeed. Perhaps he slept. He did not know. In the morning he crept from the tent, a broken old man; prepared to give up and go away, perhaps to die.

And there, squatting in the sunshine, was the sort of kindly miracle that he himself, upon occasion, performed.

The good Indian lad. As stolid and as dull and as delightfully sullen as ever. The Indian rose with alacrity.

"My father is ready?" he asked. "Today the omens are good for fishing."

The old man looked at his miracle with scientific disbelief. Yet hope came and tugged at his heart. Much would he brave for the sacred cause of his work if the conditions might be at all possible. He struggled with his halting Aymara.

"I ready," he said with hesitation. "But—other white man? He angry? Beat."

Quoipa Moiru made a large motion with his hand, including vaguely all earth and water and air and shook his head.

"The young white man has gone away," he said noncommitally. "He will not come back today. The omens are good and the boat is ready."

The old man had formulated a vague theory of drunkenness which would account for the outburst of yesterday. The debauch would continue probably for a few days. Much priceless work might be accomplished without interference. He was grateful for the respite. And as he weighed the pros and cons of his theory, he found himself seated presently in the boat. A hope came to him. A thought that perhaps in yesterday's first lucky place a kindly fate might let him catch another specimen of that unknown species so brutally spoilt by his drunken assistant. He made the suggestion to the good Indian lad; and Quoipa-Moiru with taciturn gravity paddled to the spot and made his cast.

Fate was apparently eager to manifest itself. The net dragged phenomenally heavy. In brotherly amity the frail old white man and the muscular young Indian lad heaved upon the line. Unwillingly the load came up, heavy and logy. Higher it rose, blurry under the brisk ripples of the morning breeze. There was black mud aplenty; clinging gummily; loath to let go; and something besides, queerly indistinct.

Some strange monster of the deeps perhaps, thought the old man. Anything weird or horrible might occur in this mysterious lake. Those ripples were so exasperatingly obscuring. He tugged with a will. The thing rose soggily and sloshed through the broken surface.

The old man let go his hold on the line with a choking gasp and fell back into the shallow concavity of the boat. The thing bobbed alongside and grinned its final hate, the face set in its last anthropoid twitch, the lips curled back in their last animal snarl. In the very center of the forehead, dead between the heavy black brows and the mat of hair, was a thin, crudely cut design. A circle with strokes radiating from it, and within it a more or less square.

"Gracious heavens! Good Lord, what a horror! God have mercy on his soul! How did it happen? How did he come to get drowned?"

The old man stammered his questions and shuddered away from the thing.

With a face of the ultimate impassivity Quoipa-Moiru drew a knife from among the reeds of his boat and cut the line free.

"There are things huaca which must never come to light," he muttered, almost as an incantation. "This is evil water, my father. I have other nets; and I know a place where the new fish of yesterday lives in plenty. And my father will pay me one real a day."

The old man meekly acquiesced in everything.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.